I. Introduction

While significant progress has been seen around the world in terms of poverty reduction, which is the first of seventeen United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the objective to “eliminate poverty in all its forms” is unlikely to be achieved at the current rate of progress. This is particularly true in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated global poverty for the first time in two decades. This massive global shock has raised concern about the complexity of poverty and directed attention to socially determined microlevel foundations of poverty dynamics to discern what is involved in sustainable poverty reduction.

Poverty traps are an old notion in economics that seeks to explain persistent poverty through its self-perpetuating nature.Footnote 1 According to Aart Kraay and David McKenzie, a poverty trap is “a set of mechanisms whereby countries start poor and remain poor: poverty begets poverty, so that current poverty is itself a direct cause of poverty in the future.”Footnote 2

Much thought has been devoted to designing macroeconomic models to explain how, in poor countries, long-run economic performance is heavily constrained by a country’s initial conditions.Footnote 3 These models have inspired a variety of interventions aimed at giving a “big push” needed to escape the poverty trap. Such interventions include financial access, protectionism for firms or market liberalization, technology adoption, foreign aid, and even birth control policies.

Comparatively less attention has been devoted to explaining community-level and microlevel foundations of poverty traps. At the household level, multiple mechanisms are potentially at work simultaneously. One of the most comprehensive approaches to understanding these mechanisms is the asset-accumulation framework.

It is commonly accepted that asset accumulation—broadly defined as building up physical, human, social, financial, and natural capital—can improve household well-being, allowing households to escape poverty and be less vulnerable to it by smoothing consumption in times of shocks.Footnote 4 Households that fail to accumulate assets or use them to sustainably generate income, due to multidimensional causes, are in a “poverty trap.” The asset-accumulation approach distinguishes between transitory and chronic poverty.Footnote 5 Both accumulation and utilization of assets are key determinants of the dynamics of poverty. For example, households that are highly vulnerable to shocks, such as those that live in areas exposed to extreme climate events, might be inclined to invest in buffer assets that can easily be made liquid rather than investing in less liquid productive assets or human capital. Similarly, households in places where labor markets are thin might forgo investments in education in favor of unskilled work and accumulation of, say, physical capital such as land.

The social dimension of poverty traps is the least understood. Decisions to accumulate and use assets and to determine what kind of assets to accumulate are based on expectations about what others will do, turning these decisions into socially influenced (if not determined) economic decisions. In this sense, poverty traps are not only shaped by whether a household can afford to invest in assets, but also by which assets they choose to invest in, given their circumstances, aspirations, and the expectations of return to these assets in the future.

A model of the poverty trap is designed to highlight one particular feedback mechanism underlying it, with other potential sources of the poverty trap being deliberately assumed away.Footnote 6 In reality, many sources of poverty traps are likely to coexist in a complex and dynamic way. The challenge for policy is to disentangle and integrate different mechanisms into a framework that can be useful for policy design.Footnote 7

The literature on this topic explains some of the relationships between socially influenced decisions and poverty, but no one has integrated those relationships into a framework that explains them and their feedback loops. One reasonably complete review of the literature on poverty traps, with a focus on their “social” aspects, highlights the role of belonging or being excluded from social networks as a channel that may induce poverty traps.Footnote 8 However, we need a better understanding of the dynamic interplay of the relationships underlying poverty traps that will lead to a better understanding of the political economy of poverty traps.

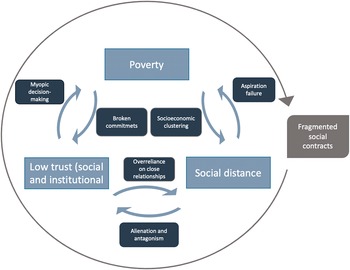

Our first aim in this essay is to take the concept of poverty from the asset-accumulation approach to further examine its social dimension. We bring the social determinants of poverty together to develop an integrated framework to examine how different determinants interact with each other to reinforce poverty traps (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Poverty, Trust, and Social Distance: A Self-Reinforcing Loop.

We explore how the interconnected factors of trust (or lack thereof) and social distance can reinforce poverty traps through myopic decision-making and aspiration failure. First, a lack of trust influences household decisions on economic matters in ways that could perpetuate poverty. We argue that a context of weak trust leads households to make myopic decisions that prevent them from escaping poverty. Second, low social and institutional trust leads to social distance, as when an overreliance on close relationships facilitates the formation of trust clusters within homogeneous groups and alienation or antagonism across groups. Third, social distance reinforces poverty traps, as when socioeconomic trust clusters are so distant from each other that it undermines the capacity to aspire. In other words, households make asset-accumulation decisions based on their aspirations, which are influenced by the groups they are part of and their relative distance to other groups that are their “aspirational milestones.”Footnote 9

Our second aim in this essay is to motivate how the socially influenced bases of poverty and its self-reinforcing dynamics are a sound way of understanding governance failures or “fragmented social contracts.” Entrenched persistence of poverty is a constant reminder of the broken commitments of political elites. Feelings of antagonism and a lack of an attainable aspiration ladder diminish the incentive to abide by an existing institutional arrangement. This is one way of understanding why some societies turn to violent confrontation as a way of processing conflict, even when institutions for political reform are in place.

The scrutiny of human behavior as influenced by social forces like those in Figure 1 will remain opaque if we do not integrate a cognitive-processing level of analysis that includes various types of automatic thinking identified by behavioralism, such as biases, frames, and mental models. Our perspective provides some key microlevel foundations of the relationships between poverty, trust, and social distance. This better understanding of how different socially influenced sources of poverty interact in a dynamic way can generate new ideas to complement the traditional policy recommendations about poverty traps. We expect this to be useful for development practitioners and development agencies.

The remainder of the essay is organized as follows. Section II conceptualizes trust, how it is formed, and its connection with development outcomes. Section III discusses the effects of weak trust on household decision-making. In Section IV, we discuss the role of trust in group interaction within a community. Section V addresses the roles of trust and social distance in the stability of a social contract. We offer some conclusions in Section VI.

II. Trust and Development

A. Trust

Humans are social creatures. Trust is the underlying foundation of human interaction between individuals, among groups, and with the state. Margaret Levi considers trust as “a holding word for the variety of phenomena that enable individuals to take risks in dealing with others, solve collective action problems, or act in ways that seem contrary to standard definitions of self-interest.”Footnote 10

We are concerned with three types of trust: interpersonal, social, and institutional. Interpersonal trust, or trust among individuals, is a keystone of human interaction and is associated with the broader concept of “social trust,” particularly in the context of social capital. Interpersonal trust, which initially takes the form of community trust or trust among those with close ties, encourages social trust, for instance, through networks of civic engagement by promoting reciprocity.Footnote 11 These networks enable coordination and intensify reputation effects, facilitating the solution of collective action problems. Francis Fukuyama describes trust as “the expectation that arises within a community of regular, honest, and cooperative behavior, based on commonly shared norms, on the part of other members of the community.”Footnote 12 Social trust implies a generalized form of trust extended to any member of the community that transcends close ties. It is thus a richer and more difficult form of trust to achieve. Information about others is key when it comes to building trust and repeated interactions are fundamental to understanding the foundations of interpersonal and social trust.Footnote 13

Institutional trust refers to society’s trust in organizations, rules, and the mechanisms to enforce those rules. It reduces transaction costs, bringing about efficiency gains and enabling contacts and agreements. It is a central aspect of strengthening governance and delivering on development. Trust in institutions, which leads to voluntary compliance with rules, is fueled by “legitimacy.”Footnote 14 Repeated interactions of commitment over time build trust; honoring commitments time and again—such as by enforcing contracts, providing public services, or not defaulting on pledges and obligations—enhances credibility and builds trust. Institutional trust can also arise from relational-based elements, based on the bonds of community membership or other shared values and beliefs.

B. Formation of trust

How is trust formed? Methodological individualism advocates that trust is based on the weighing of probabilities, a calculation of rewards and costs. According to James Coleman, a rational agent trusts “if the ratio of the chance of gain to the chance of loss is greater than the ratio of the amount of the potential loss to the amount of the potential gain.”Footnote 15 Risk-centered views are consistent with rational choice theory, which is based on the importance of self-interest.Footnote 16 Probabilities, in principle, are built as a “hazard rate,” where agents value the chance of an event happening—for example, the breakdown of cooperation—conditional on the fact that it has not happened for a given period of time or repeated number of interactions. Trust, in that sense, can also unravel rapidly through updating of such conditional probabilities.

Interpersonal trust could also arise from relational-based elements, such as familial ties, shared ethnicity, and close-knit communities. As information is revealed among these shared ties, trusting behavior is the rational outcome of a cost-benefit analysis. Coleman highlights that shared ethnicity and norms in a community enable the trust needed for market transactions.Footnote 17

Trust can also be explained by individuals being programmed by social norms to trust. In principle, social norms are “socially accepted ways of behavior in a certain group.” Understanding trust as a social norm implies that the act of trusting may or may not be rational because norms may have been internalized by nonrational means.Footnote 18 Trust can be viewed, then, as based on various elements, including culturally induced values, emotions, and sentiments.Footnote 19 In the moral philosophy sphere, trust can be motivated by goodwill.Footnote 20 According to Russell Hardin, confidence in political institutions is the product of governmental performance, in much the same way that estimations of the trustworthiness of others and willingness to trust them are based on the experience of how others behave.Footnote 21

Institutional trust is built by repeated behavior over time, that is, through manifesting commitment. When an institution is consistent and predictable in its delivery of commitments, it legitimizes itself and fulfills the expectations about its behavior that builds trust between citizens and that institution.Footnote 22 Legitimacy can also stem from a fair process through which policies and rules are designed and implemented. In the absence of commitment and fairness of processes, individuals might compensate through relational legitimacy, where sharing a set of values and norms encourages individuals to recognize authority within that group. Trust at some level is thus a key facilitator of social cooperation and coordination.

C. The connection between trust and development

Trust is related to economic growth. Using World Value Surveys (WVS) data, Paul Zak and Stephen Knack document that trust, especially its social and institutional factors, have significant effects on economic growth.Footnote 23 Paul Whitely also uses the WVS data and finds that trust has a positive effect on economic growth.Footnote 24 Fukuyama argues that cooperation, motivated by trust, is central in explaining the differences in economic performance across countries.Footnote 25

Trust also matters for government performance. In his pioneering work, Robert Putnam examines the performance of regional governments in Italy vis-à-vis the degree of citizens’ participation in civic groups and associations, such as sports clubs, choral groups, and literary societies.Footnote 26 He finds that in northern Italy, where there is more dynamic public engagement, governments are more efficient, creative, and effective than in the south, where civic participation is weaker. Other scholars have also studied the effect of trust on democratic institutions. Using WVS data for forty-one countries, Ronald Inglehart highlights that interpersonal trust and well-being are key for the stability of democratic institutions.Footnote 27 Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, in their classic five-country study, report that a stable democracy is supported by a sound “civic culture” with strong interpersonal trust and active civic engagement.Footnote 28

Trust and social networks are such important factors in economic transactions that they are conceptualized as a form of capital, namely, social capital. Social capital can be measured (to some extent), accumulated, and utilized to create wealth. It is understood as a resource or asset—such as trust, norms, and social networks—used to improve the efficiency of coordinated actions.Footnote 29 This framework has played an important role in bringing “the social experience” or “human sociability” into economic analysis.

Although the literature on trust is rich and constantly evolving, it is not well unified and it remains grounded in the technical apparatus of economics, mainly through the perspective of methodological individualism and rational choice epistemology. While we appreciate this perspective, we go beyond understanding trust as strictly an asset or resource for efficient economic transactions. We recognize different forms it could take, with potential negative outcomes for development. Moreover, we go beyond rationality as the default for understanding behavior and welcome an approach to trust that sees it as not only an individual characteristic, but also a social one.

III. Trust, Decision-Making, and Poverty Traps

Weak trust shortens one’s planning horizon and induces myopic decisions that, in turn, reinforces poverty traps. The notion that poverty can lead to a discounting of future rewards in lieu of present gains is well established in economic and cognitive sciences.Footnote 30 While all individuals tend to discount the future to some degree, poor households are associated with higher levels of discounting, even hyperbolic discounting in which the discount factor is not constant consumption over time. In the presence of uncertainty and cash or credit constraints, people make decisions with short time-horizons and become “impatient.” This behavior has empirical support and can also be explained through evolutionary fitness.Footnote 31

A myopic orientation toward the future has important implications for economic decision-making. Steep future discounting lowers household well-being in the long run by systematically steering decision-making away from asset accumulation, thus discouraging investment and saving. For example, it might steer households away from saving in favor of immediate consumption. This discounting has a reciprocal effect on poverty, creating a trap: poverty leads to short-sighted choices that, in turn, perpetuate poverty.

What is it about poverty, though, that causes short-sighted decision-making? Part of it has to do with uncertainty about the future. While the future is uncertain for all, the poor systematically face a greater risk of negative outcomes, such as premature death (with lower levels of overall health and access to health care), losing labor income (due to informal contractual relationships with employers), eviction, and experiencing violence, among other manifestations of the multidimensionality of poverty. Some explain this present-oriented bias through a behavioralist lens, which understands poverty as a cognitive burden on individuals who have to focus a large part of their cognitive capacity on worrying about where the next meal will come from or where to collect water from, leaving less capacity to focus on future-facing decisions.Footnote 32 A metaphor often employed to describe this phenomenon is the “cognitive tax on poverty,” which means that financial distress reduces people’s “cognitive bandwidth” or mental resources.

The formation of trust, as a belief, depends on observations and experiences accumulated over time. Individuals with higher income are more likely to have favorable standard-of-living experiences, while low-income individuals are more prone to experience violations of trust that reinforce a grim vision of others. Consider crime as an example. While crime affects all, higher-income households are likely to live in neighborhoods with better law enforcement (financed by taxes), while poorer households are likely to have a less favorable experience with the police. In that way, as Jon Jachimowicz and his coauthors point out, trust is unequally distributed throughout society, determined partly by the way in which people “experience the state” through their interactions with state institutions.Footnote 33 In some poor, marginalized communities, poor people see the face of the state only in the police.

Investing in scenarios characterized by long-term payoffs implicitly involves trusting that the promised long-term benefits will materialize. However, when the belief that delayed benefits will materialize is weak, the rational decision is to engage in short-term transactions.Footnote 34 Thus, trust can be seen as a mechanism to soften the impacts of unpredictability by helping individuals deal with uncertainty and complexity.Footnote 35

A recent study surveys factors that could explain short-term decision-making and sheds light on the relationship between trust and myopic decision-making.Footnote 36 More specifically, the study finds that lower income leads to high discounting of the future mainly in circumstances of low community trust, with community defined as family, neighbors, and friends. In other words, low-income individuals with high community trust do not display the usual high rate of future discounting that other low-income individuals display as compared to high-income individuals; only those with low income and low community trust display a high rate of future discounting. Trust in one’s community (or close group) thus offers a buffer against crises and to some extent lessens future discounting. The example of people borrowing at high interest rates usually happens in contexts where people do not have close ties on whom to rely and—to a lesser extent—in contexts where they lack the cognitive bandwidth to process thoroughly information regarding the cumulative cost of the credit.

These studies suggest that myopic decisions are not entirely limited to the experience of poverty; they are also mediated by trust. Low-income communities with strong social cohesion have incentives to avoid short-sighted behaviors and to invest in endeavors that entail delayed gratification. Whether community trust can act as a substitute for institutional trust and, if so, to what extent, is an interesting issue.

IV. Social Distance and Poverty Traps

A. Effect of exclusive reliance on close relationships on alienation between social groups

Beyond its effects on individual decision-making, trust also mediates how people within a society interact. Jachimowicz and his coauthors contend that close ties may be of paramount importance in the context of poverty, but such ties could have complex repercussions if strong community trust increases a group’s distance from other groups.Footnote 37 Social distance between groups that are internally cohesive has important implications for poverty.

Polarization in a society describes intergroup conflict dynamics, which is an idea that can be traced back at least to Karl Marx.Footnote 38 However, its modern conceptualization and measurement comes from Joan-Maria Esteban and Debraj Ray, who hold that every society can be thought of as an amalgamation of groups, where two individuals drawn from the same group are “similar,” while those from different groups are “different” relative to some given set of attributes or characteristics.Footnote 39 Polarization of a distribution of individual attributes then exhibits the following features: (1) a high degree of homogeneity within each group or cluster, (2) a high degree of heterogeneity across groups, and (3) a small number of significantly sized groups. Groups of insignificant size (such as isolated individuals) carry insufficient weight to affect the general polarization.

Social clustering is heavily informed by socioeconomic status or class. However, this is not the only relevant factor. Race, religion, ethnic, or tribal belonging or nationalistic sense also cause socially polar structures. Polarization is relevant because it is often linked to the creation of social tensions, the possibility of rebellion and revolt, and the existence of general social unrest. This is especially true if income or wealth are variables.

Esteban and Ray distinguish between identification and the alienation that takes place as societies break up into clusters.Footnote 40 Identification refers to intragroup homogeneity. Taking any characteristic x, such as income or education, they propose that an individual feels a sense of identification with other individuals who have the same x as him. Hence, the identification felt by an individual is an increasing function of the number of individuals in, say, the same income class. The sense of identification may depend not only on the number of similar individuals, but also on the common specific characteristic(s) that these individuals possess. Alienation is the opposite of identification. An individual feels alienated from others who are “far away” from him, with distance identified in a well-defined “space” (d(x, x’)).

How do identification and alienation relate to trust? We argue that social clusters form based on specific common characteristics, such as social class, and they reinforce both relational trust within groups and alienation between groups. In other words, social clusters become trust clusters, where individuals believe that those within their group will protect their own interests, while those in other groups will not. In this way, alienation is effectively a form of antagonism between individuals rather than just a passive way of contemplating social distance among groups. Individual feelings of identification may even influence the “effective voicing” of alienation. If polarization depends on a “vector” of effective antagonisms in society, then an axiom that can be derived from this model is that, in the case of income, the disappearance of a “middle class” into “rich” and “poor” categories will increase polarization and erode social trust.Footnote 41

An individual’s sense of identification may depend not only on the number of other individuals with similar attributes, but also on the attributes themselves. This implies that an equal number of people in two different income categories may possess an unequal degree of “effective identification.” This matters because the resources available to those in richer groups may contribute to them manifesting as a more unified entity, for example, by creating lobbies, organizing protests, and pushing particular policies,Footnote 42 with mechanisms to voice and protect their own interests. These mechanisms might not be available to groups with fewer resources, so their capacity to participate in decision-making processes is diminished. If antagonistic feelings in polarized societies are reciprocal—flowing from the poor to the rich as much as from the rich to the poor—then a poverty trap is likely to be reinforced. As can be inferred from Esteban and Ray’s model, one way to bring together economically polarized groups is by creating a strong and ever-growing middle class to serve as a “bridge” to ease social tensions.Footnote 43

Our framework depicted in Figure 1 above specifies that social distance increases not only because of alienation between groups, but also in the absence of institutional trust. Therefore, institutional trust is another source of mediation between different social groups. If a set of norms as well as arbiters who are seen as fair and equitable exist to promote cooperation and solve disputes, it might be possible to embrace plurality and differences in a society. Institutional efficiency is always perfectible, in this sense. The minimum requirement for legitimacy is that the process of reforming formal institutions is fair and accessible for all. (In Section V below, we provide a closer examination of the relationship between institutions, poverty, and trust.)

The mechanics of social distance (effective antagonism) described by Esteban and Ray have found strong support from social cognition scholars. Elizabeth Segal and her coauthors review studies on the origins of empathy and describe survival and genetic reproduction as best accomplished through group living that relies on empathic behaviors among group members.Footnote 44 Empathic feelings are stronger for those who will help to ensure successful survival and reproduction. Those most likely to ensure our survival have been others who look, think, and act similarly, particularly in terms of race, gender, age, ability, political identification, and social class. Unfortunately, this tribal instinct, coupled with our relative difficulty in enacting empathy for people who are different from us, often results in a tendency toward “us versus them” attitudes and behaviors, which are usually counterproductive in our modern context.

This perspective emphasizes the endogenous nature of social proximity and social distance as opposed to the structuralist approach described above. More importantly, while some barriers to empathy may be inherited and have to do with species survival, most of them seem to be cognitively developed, albeit unconsciously at a young age. Experiential learning that taps into one’s empathic neural system by seeing others as similar rather than different thus seems to be the most effective way to influence empathic resonance or insight.Footnote 45

B. Social distance as the origin of aspiration failure

Trust clustering and social distance have another important implication for poverty, as they affect the formation of aspirations. Esteban and Ray may describe the mechanics of polarization, but we are also interested in understanding how the cultural process through which aspirations are formed interreact with the experience of social distance. Once one recognizes that culture has an important role to play in development, the challenge becomes understanding how exactly it does so. As Amartya Sen explains, in one form or another, culture engulfs our lives, our desires, our frustrations, our ambitions, and the freedoms that we seek.Footnote 46

According to the capability approach, social distance can have an impact on the “functionings” of individuals.Footnote 47 People’s functionings—their real and effective options to be or do—are shaped by their aspirations and agency. Aspirations are drivers to make decisions that enable individuals or households to transition from their current situation to another one they desire, for themselves or for their children. Agency refers to people’s effective capability to act to reach those goals. These, however, are shaped by the societies in which individuals live, their relative position within that society, and the distance between the groups they belong to and other groups.Footnote 48

This relationship between aspirations and agency can also be approached from the behavioralist perspective, which holds that poverty may generate an internal frame or a mental model that interprets the world and poor people’s role in it. Shared frames create self-reinforcing collective patterns of behavior. These patterns of behavior might be highly desirable, such as trust and shared values. However, when group behaviors influence individual preferences and individual preferences feed into group behaviors, societies can also develop patterns that are ill-advised or even destructive for the community.Footnote 49

In this sense, mental models come from the cognitive side of social interactions, which is often construed as culture. Poverty and the perspectives of escaping from it depend, to some extent, on the way the poor interact on a symbolic level with the nonpoor. Arjun Appadurai argues that the capacity to aspire must be recognized as a cultural capacity, especially for the poor.Footnote 50 The future-oriented logic of development could find a natural ally in this cultural capacity and the poor could find the resources required to contest and alter the conditions of their own poverty.

Appadurai’s idea that the most important dimension of culture as it relates to poverty and development is its orientation toward the future is counterintuitive, given that when we think about culture we usually think in terms of tradition, habits, and customs rather than goals, dreams, and expectations. The complex relationship that the marginalized have to the cultural regimes within which they function is clearer still when we consider the specific cultural capacity to aspire. Aspirations about a good life, health, and happiness exist in all societies. However, the capacity to aspire is not evenly distributed within a society.Footnote 51 The relatively rich and powerful invariably have a more fully developed capacity to aspire because the better off people are, in terms of power, dignity, and material resources, they are more likely to be conscious of the causal links between more and less immediate objects of aspiration. The better off, by definition, thus have a more complex experience than do the poor of ends and means, but this difference should not be misunderstood. Appadurai is not saying that the poor cannot wish, want, need, plan, or aspire, but that their capacity to do so remains less developed.Footnote 52 According to Ray, this is not a condition inherent to individuals who are poor, but about the condition of poverty itself. The capacity to aspire, like any complex cultural capacity, thrives and survives on practice, repetition, exploration, conjecture, and refutation.Footnote 53

For the capacity to aspire to become a concrete capability that can be exercised for development purposes, it needs to function as an ethical and psychological horizon made up of credible hopes. The idea that hopes could be fulfilled is essential to transition from “wishful thinking” to “thoughtful wishing.” It is important to recognize that aspirations are constructed socially, in relation to the experiences of other individuals “in the cognitive neighborhood of that person” or “from the lives, achievements, or ideals of those who exist in her aspirations window.”Footnote 54

When faced with an “aspiration gap,” which is the difference between our perceived current situation and the position we would like to fill, reducing the gap requires individuals to invest their current resources to achieve future returns. However, when aspirations are too distant from someone’s current circumstances, her incentives to invest also decrease.Footnote 55

George Akerlof brings into this discussion another way in which “social decisions” are influenced by social distance.Footnote 56 According to him, individuals might be either status seekers or conformists. A status seeker’s behavior depends positively on the difference between the individual’s own status and the status of others, building their aspirations in relation to those who are better off than they are. In contrast, a conformist wants to mimic the status quo as much as possible. If social distance within groups is high and the trust in close ties is strong, there are powerful incentives to mimic as much as possible those in your nearest social circle. In other words, there is a motivation to conform to the current status quo, even if this status quo is one of deprivation. This tendency might be the result of fear of negative “sanctions” coming from friends, family, or neighbors, due, for example, to jealousy and envy. These possible sanctions and the risk of failing to achieve a successful social jump can be a powerful motive for conformity that is as strong as the desire to preserve the positive benefits of love and friendship. Therefore, one’s close community can exert not only “distance” but also “increased inertia” on potentially ambitious individuals.

An example of how aspirations can become a space for interventions comes from Ethiopia, where disadvantaged individuals commonly report feelings of low psychological agency, often making comments like “we have neither a dream nor an imagination” or “we live only for today.”Footnote 57 In 2010, randomly selected households were invited to watch one hour of inspirational videos comprising four documentaries of individuals from the region telling their personal stories about how they had improved their socioeconomic position by setting goals and working hard. Six months later, the households that had watched the inspirational videos had higher total savings and had invested more in their children’s education, on average, than those that had not. Surveys revealed that the videos had increased people’s aspirations and hopes, especially for their children’s educational future.Footnote 58 The study illustrates the ability of an intervention to change a mental model of one’s belief in what is possible in the future.

The more continuous a society is, the more attainable the aspiration to move upward becomes and the more reasonable is the amount of effort required to achieve that aspiration. If one follows Debraj’s argument, then if an economically unequal society is thickly populated at all points of the economic spectrum, local and attainable incentives to aspire exist at the lower end of the wealth distribution. On the other hand, in societies where groups are concentrated in nodes with significant distance between them, changing one’s situation requires greater effort, which disincentivizes action. This results in a failure of aspirations for those farthest behind, which in turn perpetuates poverty. Aspirations are thus an important part of the symbolic realm of decision-making.

Returning to the issue of the extent to which community trust can substitute for institutional trust as a route out of poverty, it is possible for this to occur. However, if one follows Appadurai’s and Esteban and Ray’s arguments, this substitution could also be part of what perpetuates poverty traps.

V. Social Contracts as Equilibria Built on Trust

Another way in which low trust and social distance are related to poverty is by restricting the ability of a society to reach an optimal social contract in which all members of society choose to participate. Aspiration failure is an analytically rich way of understanding fractures in the social contract.Footnote 59 If no attainable aspiration ladder exists within an institutional framework and someone is skeptical about institutional reform possibly going in his favor, then why would he remain within its boundaries? Ken Binmore offers a set of characteristics that social contracts should have in order to be successful devices for ordering public life. He holds that they must be perceived as fair by all actors; be economically, socially, and environmentally stable by means of voluntary compliance; and efficient in competing successfully with other societies.Footnote 60

Binmore models human social life as a series of strategic interactions and a collection of repeated games, which he labels the “game of life.”Footnote 61 To achieve a fair solution to the game and a fair social contract, participants should not know in advance what their position will be under the rules they are adopting. In terms of governments, institutions, and other contenders, this “veil of ignorance” or “original position”Footnote 62 exists when political actors do not know beforehand whether they would be elected and play the position of enforcing the contract or be subject to its enforcement. It is a form of insurance to secure fairness and justice understood as “mutual advantage.”

Trust can be seen as the glue that binds together Binmore’s characteristics of a successful social contract. Only when individuals trust that the social contract will be stable and agree that it is fair and beneficial to them, will they voluntarily comply with it. For example, if citizens do not trust that the government will use public funds efficiently, given their experience with the quality of the services, then they will be less willing to pay taxes. In many countries, the middle class, once their income allows for it, abandon public services that they perceive as subpar, such as education and health, in favor of privately funded services. Naturally, this deepens their reluctance to pay taxes that would fund the public services they no longer use, which results in a deterioration in the quality of the services that the poor who cannot opt out receive.

The main factor at play for low-quality service provision is the relative inability of the population at the lowest end of the income distribution to effectively voice their demands for high-quality services. Also, people who are somewhat were better off and have a different aspiration abandoned the coalition that pushes for better public services, therefore increasing the social distance between groups. Indeed, social contracts can be hierarchically asymmetrical. In most societies, certain citizens and groups are more influential than others, giving them more say in the nature and content of social contracts. In some countries, the government is so powerful that all societal groups together have hardly any say at all in the social contract and must de facto accept it.Footnote 63

A contract is a formal manifestation of an agreement between peers or, in a political society, between free and equal citizens. However, socially disadvantaged groups tend to lack the influence or power to shape the social contract. When this happens, social contracts take the form of political settlements, understood as elite bargaining equilibria.Footnote 64 If, at one end of the social distribution, the power to shape the social contract is overrepresented, it is unlikely that those not in the elite will trust that it will serve their interest. Regardless of what the agreement entails or whether elites act in a public-spirited way, the fact that a group is excluded from having a say in it compromises the procedural legitimacy of the social contract. When a polarized social contract neglects providing opportunities for a broad social sector, incentives to abide by its institutions also break down. The entrenched persistence of poverty is a constant reminder of broken commitments by the political elite, thereby eroding social contracts.

Treating the poor instrumentally can take many forms, but they all have the potential to erode the foundations of the social contract that elites control. Fragmented social contracts might lead to effective voicing of antagonism through protests, riots, or violent confrontation. Confrontation itself reinforces polarization, which in turn makes it increasingly difficult for political and social entrepreneurs to form a coalition for policy reform.

VI. Conclusions

The social determinants of poverty are not well understood. In this essay, we have argued how overall trust with its associated dimension and social distance are central to understanding the mechanisms through which poverty traps are sustained. In our integrated framework, the socially influenced foundations of poverty dynamics also better explain fragmented social contracts. Our approach to understanding poverty has practical implications for antipoverty and broader development policies.

Trust and poverty reinforce each other. However, in the relevant literature, insufficient attention has been devoted to understanding the microlevel foundations or specific mechanics of this cyclical relationship. We have discussed the role that trust plays in decision-making, especially in the way individuals invest in their future. If especially low-income people do not trust social networks or institutions, they lack the motivation to invest in their future, reinforcing poverty traps. Evidence shows, though, that when community trust is present—as with kin, friends, and neighbors—that can act as a buffer to myopic decision-making.

Aside from influencing individual household decision-making, trust also determines how groups interact with each other, which is fundamental for societal-level outcomes, including the incidence of poverty. High homogeneity within a group will create a trust cluster arising from relational-based elements, such as familial ties, class, shared ethnicity, and close-knit communities. However, when their characteristics make groups significantly different from each other, a polarization effect occurs. Polarization is characterized by identification and alienation: the further away the groups, the more alienation a group feels toward other groups and the more identification members of that group feel with each other. Alienation, as described by Esteban and Ray, is a way of capturing effective antagonism between individuals. Antagonistic feelings, or a lack of trust, in polarized societies also reinforce poverty traps.

Trust recreates itself in each social interaction, informed not only by the material reality, such as income distribution, but also by other contending ideas, such as religion, race, and nationalism. This is why a cultural approach sheds light on the microlevel foundations of trust in relation to poverty. Aspiration operationalizes the symbolic realm in the relationship between poverty and trust. Aspiration is understood as the capacity for individuals to move toward a future they desire. Aspirations are not entirely endogenous, though; they are influenced by context. When aspirations are deemed as being too far away from current circumstances, incentives to invest in that future collapse; they are just not worth the effort. This is one of the main arguments for seeking a society broadly populated at all levels of income distribution.

Furthermore, the socially influenced bases of poverty and its self-reinforcing dynamics are an analytically rich way of explaining how social contracts can fracture. In order to survive, social contracts need to be stable, efficient, and fair. They need to induce voluntary compliance, which requires a certain level of trust. Nevertheless, the entrenched persistence of poverty is a constant reminder of (especially) the political elites’ broken commitments. Feelings of antagonism between social groups and a lack of an attainable aspiration ladder diminish the incentive to abide by an existing institutional arrangement, which helps us understand why some societies are turning to violent confrontation as a way of processing conflict, even when institutions for political and electoral alternation are in place.

Trust has an impact on individual decision-making processes, how groups within a society interact, and on the stability of social contracts. In these spheres, the absence of trust has important repercussions for how poverty is perpetuated. Looking toward more effective and sustainable poverty reduction, we need to understand these linkages and address them systematically.

What is essential about poverty traps is that they tend to persist. This might sound like a grim message, but it is not impossible for an economy and households to escape from it. Three main policy categories offer ways out of poverty traps: (a) provide the poor with greater access to markets through savings, credit, insurance, information, and property rights; (b) improve the access of the poor to public services and infrastructure by expanding coverage and reducing corruption; and (c) redistribute resources to the poor through cash or in-kind goods and services.Footnote 65

However, these three categories of policy options do not address social structures and their behavioral consequences.Footnote 66 Some policies do deal directly with myopic decisions and with influencing aspirations, but many other policy options need to be considered, given the socially influenced nature of decision-making about asset accumulation. Dealing with poverty traps is a difficult endeavor. Small adjustments often fail to move people out of low-level dynamic equilibria, unless they are carefully targeted at precisely the context-specific mechanism that traps people in poverty. Systems must change, major positive shocks must occur, or both.Footnote 67 The systemic nature of this problem is benefited by frameworks that acknowledge dynamic relations between different determinants of decision-making and see policymakers as part of the system of power asymmetries that reinforce poverty traps.