In many places in the world, politics has arguably become “media politics”—with political discourse and decision making increasingly refracted through networks of mass communications and media representations and with the lines between celebrities and politicians increasingly blurred. In this context, understanding how politically relevant information is produced and consumed is arguably central to understanding how politics functions (both at a systemic level and at the level of many specific political outcomes and events).

One important conceptual tool that researchers have developed to investigate the nature and impact of the processes of information production and consumption that characterize our contemporary mediascape is the notion of infotainment. While different scholars and observers define and investigate it in various ways, at its core infotainment describes a style of communication that mixes (in our case, politically relevant) informative materials with formats and representational/narrative techniques originally developed and employed in entertainment-focused genres. In both popular and academic usage, it is almost always conceptualized in contrast to something one might loosely term the “Golden Age of journalism” model of hard news coverage (whose key stylistic characteristics are usually portrayed as including objectivity, accurate information, serious analysis, and so on) (see Krause, Reference Krause2011; Schiller, Reference Schiller1979; Schudson, Reference Schudson2015).

While the concept of infotainment was originally coined as a buzzword for criticism of contemporary television in the 1980s in response to a variety of trends in commercial broadcasting in the United States (see Thussu, Reference Thussu2007), a burgeoning literature has uncovered not only the global reach of infotainment phenomena but also its presence in, and impact on, the political realm (see, for example, Azari, Reference Azari2016; Hadfield, Reference Hadfield2017; Lalancette and Cormack, Reference Lalancette and Cormack2018; Lawrence and Boydstun, Reference Lawrence and Boydstun2017; Marland, Reference Marland2018; and Serazio, Reference Serazio2018, for the ways that infotainment formats have been key in the framing and sensationalization of winning candidates for political office). Unsurprisingly, these findings have also sparked debates over the empirical and normative implications of political infotainment for citizens and democratic systems (see Marinov, Reference Marinov2020).

While infotainment has been heavily researched in the United States (and to a lesser degree in other regions), there has been virtually no examination of the existence and nature of infotainment in Canada (particularly around hard news coverage). Thus, there is no consensus at all regarding the degree to which an infotainment style characterizes media coverage of politics in Canada. This article therefore seeks to address this important gap in our understanding by analyzing the presence, intensity and nature of infotainment in Canadian English-language (CEL) newspapers’ hard news political coverage, using the 2019 Canadian federal election campaign as our orienting case study.

We begin our article in section 1 with a brief overview of the ways that infotainment has been previously studied, as well as a discussion of the degree to which it has been examined in the Canadian context. Sections 2 through 4 then outline the specific research questions, methodology and research design choices that oriented our study. We then share our findings regarding CEL newspaper coverage of the 2019 federal election: section 5 begins this discussion by offering an overview of our high-level findings about the prevalence of both infotainment and the Golden Age style; section 6 continues our discussion by offering a more granular and detailed discussion of the specific nature of the Canadian version of infotainment by examining what we found about the presence and prevalence of each of the main characteristics (and the key sub-characteristics). Section 7 concludes the article with a brief discussion of some of the implications of our findings, as well as some of the potentially fruitful avenues for future research.

1. Existing Studies of Infotainment

While early examples (and the early origins) of the modern infotainment style have been traced back to the yellow journalismFootnote 1 and street literature of nineteenth-century England, and certain elements of it have been identified in different media throughout the twentieth century (Borchard, Reference Borchard2018; Brants, Reference Brants, Kaid and Holtz-Bacha2008; Thussu, Reference Thussu2007), in the existing scholarly literature, infotainment is most commonly conceptualized as a relatively recent set of stylistic trends and media formats that have emerged since the 1980s. Since then, the concept has been used in various ways to analyze and describe diverse media phenomena (from news media to talk shows, and from genres to entire media landscapes), as well as to normatively evaluate/critique these phenomena.

Elsewhere (Marinov, Reference Marinov2020) we have offered a detailed overview and evaluation of the existing literature on infotainment (including the diverse definitions and research trajectories) and have argued that the existing literature can be grouped into three main categories: (1) research that examines infotainment as a comprehensive transformation within national and international media systems on a more macro level, (2) research on soft news programming (talk shows, late night comedy and satire, and so forth) as a specific infotainment genre of its own, and (3) research on the degree to which infotainment stylistic and format characteristics characterize traditional hard news coverage in newspapers, televised newscasts, and radio. Given that our focus in this article is on hard news coverage, our study is located primarily in the third category.

In general, the conceptualizations of infotainment used to analyze hard news coverage have drawn heavily from journalism studies (often defined by associated concepts, such as tabloidization, sensationalization, and soft versus hard news distinctions), with most scholarship in the area falling into two main strands of research.

The first strand focuses on the proliferation of soft news stories into news coverage and on the degree that this has displaced more serious and informative hard news stories and styles of covering political material. For example, Patterson's (Reference Patterson2000) seminal study of over 5,300 news stories in America between 1980 and 1999 found that regardless of how soft news stories were defined or measured, they had increased considerably over hard news stories during this period. Since then, a variety of studies using diverse definitions and methods have further confirmed these conclusions by finding that, to varying degrees in both the United States and Europe, stories that present their content using more entertainment-oriented techniques (for instance, designed to heighten the entertaining, emotional, dramatic, or general human-interest nature) have come to dominate televised and print news, displacing much of the more serious and politically relevant information that is viewed as necessary for the health of the democratic system and the civic role of citizens (Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, van Aelst and Curran2010; Curran et al., Reference Curran, Iyengar, Lund and Salovaara-Moring2009; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2004; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar2007; Thussu, Reference Thussu2007).

The second strand of infotainment research on news media examines hard news coverage more directly by exploring the degree to which the format/style and content of hard news coverage has adopted more entertainment-oriented elements. These types of studies have, for example, explored whether traditional news outlets have provided less in-depth, less contextualized or less well-researched coverage of hard news topics and whether presentational style has become softer, less serious, more sensationalized and/or more framed around aspects such as personality, celebrity, human interest, and opinion and speculation (see Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Jensen, Gomery, Fabos and Frechette2014; Compton and Dyer-Witheford, Reference Compton and Dyer-Witheford2014; Graber and Holyk, Reference Graber, Holyk, Edwards, Jacobs and Shapiro2011; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar2007; Thussu, Reference Thussu2007). Scholars have also sought to explore the causes of these trends, such as the impact of media fragmentation, 24-hour newscasts, and internet news (which require constant and newly developing material, even when facts haven't been fully established, researched or documented) (see Iyengar, Reference Iyengar2007; Thussu, Reference Thussu2007) or of structural economic imperatives in the face of news audience decline (see Graber and Holyk, Reference Graber, Holyk, Edwards, Jacobs and Shapiro2011; Harrington, Reference Harrington2008; Iyengar, Reference Iyengar2007; Langman, Reference Langman, Ritzer, Ryan and Thorn2017; McManus, Reference McManus1995).

Methodologically, studies of infotainment in hard news coverage have used diverse criteria for analysis. For example, some analyses have sought to evaluate the journalistic “style” or “role performance” (Graber, Reference Graber1994; Hallin and Mellado, Reference Hallin and Mellado2018), including the journalistic use of “candidate challenges” to construct a form of entertaining and dramatic “reality news” akin to the sensationalism of reality TV shows (Bennett, Reference Bennett2005). Others have focused on evaluations of the content of news by looking at a number of elements including topic, valence, criticism, fear discourses, the use of ambiguity, surprise elements, polls, personalization, privatization, and more (Baum, Reference Baum2005; Brants, Reference Brants1998; Brants and Neijens, Reference Brants and Neijens1998; Carrillo and Ferre-Pavia, Reference Carrillo and Ferré-Pavia2013; Jebril et al., Reference Jebril, Albaek and de Vreese2013).

Overall, then, as highlighted by Reinemann et al. (Reference Reinemann, Stanyer, Scherr and Legnate2012) and Otto et al. (Reference Otto, Glogger and Boukes2017), while there is a fairly strong consensus among scholars that infotainment is an important and growing phenomenon even in hard news coverage, the diversity of approaches has meant that there is no consensus about how to define infotainment or how to methodologically study it. As such, any study of infotainment must, at a minimum, very clearly outline not only its definition but also its method of operationalizing and investigating infotainment.

2. The Study of Infotainment in Canada

There are certainly reasons to suspect that infotainment might be present in Canadian hard news. Many scholars argue that infotainment is now a global phenomenon, driven by transnational supply-and-demand dynamics (between news organizations and their audiences) that have changed the “working assumptions” of both journalists and audiences so as to render the infotainment format, with its profound fusion of news and entertainment, a normalized and expected form across news media (Altheide, Reference Altheide2004: 293; see also Baym, Reference Baym2005). Statistics Canada data (Statistics Canada, 2019), moreover, show that the Canadian media sphere has been experiencing many of the same structural changes that have been identified as global drivers of increased infotainment—including significant reductions in subscription and advertising revenue, industry consolidation and a growth in mergers and acquisitions, deep cuts to newsroom staff and resources, an increasing percentage (roughly 15 per cent at last count) of newsroom operating costs going toward subcontracting news production, and regular industry layoffs (for example, Postmedia's recent announcement of layoffs and the closure of some 15 local newspapers; see Canadian Press, 2020).

Despite these trends, there have been no explicit and comprehensive studies of the prevalence of infotainment in Canada's hard news coverage. There are one or two studies that use the concept of infotainment to explore soft news coverage in Canada (for instance, Bastien, Reference Bastien and Roth2018, which explored infotainment in French-language soft news television programming, and Onusko, Reference Onusko2011, which analyzed the Rick Mercer Report as an example of infotainment). Moreover, there are other studies that have examined news coverage in Canada which, while not examining infotainment explicitly, have touched on certain elements of sensationalism, the production of soft news, and other characteristics that are also central to infotainment (for instance, Edge, Reference Edge2016; Hackett and Zhao, Reference Hackett and Zhao1998; Prato, Reference Prato1993; Rose and Nesbitt-Larking, Reference Rose, Nesbitt-Larking, Courtney and Smith2010; Taras, Reference Taras1990, Reference Taras2008). Other examples of this include several key longitudinal studies, such as Bastien (Reference Bastien2020), which found evidence of an increase in strategic framing and a decrease in factual reporting styles within televised leaders’ debates, and Sampert et al. (Reference Sampert, Trimble, Wagner and Gerrits2014), which found a growth in a number of reporting characteristics typical of the infotainment format, including increased use of opinion, photos (appearance over content), combative or game-like language, and a personalized focus on candidates over parties, all of which they argue point toward a growth in the use of “media logic” to structure political communications. In addition, both episodic and competitive or game-like framing of politics have been identified in Canada's political news coverage. Trimble and Sampert (Reference Trimble and Sampert2004), for example, found evidence of game framing of elections within headlines from the Globe and Mail and the National Post, while Marcotte and Bastien (Reference Marcotte and Bastien2012) found evidence of game framing and event-based (rather than issue-based) coverage increasing among French-language media producers as they face less sheltering from market pressures. Similarly, Andrew (Reference Andrew2013) has identified a strong presence of opinionated coverage of election campaigns, notably among Canada's commercial newspapers.

While these studies therefore suggest that certain characteristics typical of infotainment are likely present in various types of media coverage of Canadian politics, none of them offer a clear and robust conception and definition of infotainment. Nor do they employ the type of systematic and robust methodology that would be required to ground for broad and systematic findings about the presence and nature of an infotainment quotient in political hard news coverage. As such, there remains a significant gap in our knowledge regarding the prevalence of infotainment in Canadian political news coverage (both in general and in Canadian hard news political coverage in particular). This gap is precisely what our study was designed to address. To that end, we will now turn to the specific research questions of our study and its methodological design.

3. Research Questions

Given the almost complete dearth of studies on the subject, there are far more research questions about infotainment in Canada than we could explore. In this context, we decided to pose two sets of questions that would both offer a portrait of the current state of infotainment and provide some empirical basis for evaluating the normative/ethical/political implications of these findings in the future:

• Research Question 1 (RQ1): To what degree does the hard news political coverage in Canadian English-language (CEL) newspapers embody the characteristics of an infotainment style? And if present, what is the nature, intensity and mix of those characteristics?

• Research Question 2 (RQ2): If infotainment characteristics are present in the hard news political coverage in Canadian English-language (CEL) newspapers, to what degree do these characteristics coexist with the characteristics that are traditionally understood to characterize the “Golden Age standard” style of informative and analytic hard news coverage?

The purpose of RQ1 is to address the basic gap in our knowledge about the existence and nature of infotainment in Canadian hard news coverage. The purpose of RQ2 is to offer additional insight into whether an infotainment style precludes other styles or whether it can coexist with other styles within the same article—a question that is important not only for our empirical understanding of infotainment (which is our interest in this article) but also for contemporary ethical debates about the value and impact of infotainment in civic life (for some examples of scholars who argue that infotainment might have some positive impacts—especially as a way of encouraging less interested citizens to engage with political issues—see Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, van Aelst and Curran2010, Bennett, Reference Bennett2003; Graber and Holyk, Reference Graber, Holyk, Edwards, Jacobs and Shapiro2011; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton2004; Harrington, Reference Harrington2008; Jones, Reference Jones2009; Just, Reference Just, Edwards, Jacobs and Shapiro2011; Patterson, Reference Patterson2000; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992, Reference Zaller2003).

Answering these questions is pertinent to political scientists for several reasons, related primarily to concerns over citizens’ political learning and engagement as components of a healthy democratic system and culture. First, and primarily theoretically, they led us to develop a robust and operationalizable conception of infotainment relevant to the study of political news coverage. We believe that this expands the toolkit of political science discourse analysis by helping scholars understand how political news coverage functions in ways that are quite different than analyses which focus solely on ideology, policy positions, partisan commitments, group/actor political-economic interests, and a host of other traditional categories often used within political science. Secondly, and more empirically, answering these questions offers a nuanced and robust portrait of how and what is presented in Canadian news coverage—an understanding of which is generally deemed to be at least somewhat important in understanding the formation of voter perceptions and preferences in our contemporary media-saturated mode of electoral politics. Finally, answering these questions is also potentially relevant for normative reasons insofar as it gives us important information about the type, format and style of information that citizens now face when engaging with political news and analysis. Namely, by empirically measuring how prevalent infotainment versus Golden Age content/style are, how they each function, and the degree to which such differing stylistic characteristics coexist or not, we are better equipped to identify, evaluate and address the challenges (and opportunities) that citizens currently face in one important arena of political discourse and engagement.

4. Methodology

How did we investigate these questions? While we offer a very detailed discussion of our methodology in the online appendix accompanying this article, for reasons of space we will offer only a brief overview of the mechanics of our study here.

4.1 Defining infotainment and the Golden Age style

Our first task was to decide how to conceptualize and define infotainment. To do so, we conducted an exhaustive and detailed review of the existing scholarly literature on infotainment. As part of this, we reviewed, analyzed, evaluated and synthesized how various scholars conceptualized infotainment, how they defined it, what methods they used to study it, and their key findings (Marinov, Reference Marinov2020). Our review determined that while infotainment is defined and operationalized in many different ways, the vast majority of conceptualizations can be synthesized under three main characteristics.Footnote 2 Accordingly, for this study, we defined infotainment as an overarching archetypal style of communication in which the content, framing and/or presentational techniques render the news

• personalized—that is, focusing more on politicians, their style and personal traits than on policies, social/political/economic issues, parties, programs/platforms or other more substantive political content;

• sensational, rather than serious, analytical, investigative, or otherwise educative and substantive; or

• decontextualized and speculative, rather than factually informed, socially and politically contextualized, or consisting of genuine events/information (as opposed to constructed/scripted/staged events/information).

We refer to these three elements as the three main characteristics of infotainment. We suggest, moreover, that each of these three macro-characteristics can be performed/embodied by a variety of sub-characteristics (which we define and discuss in significant detail in the online appendix).

These characteristics (and sub-characteristics), moreover, are not mutually exclusive (that is, a news item might embody many sub/characteristics or just one). Nor must any specific characteristic/sub-characteristic be present for coverage to qualify (at least partially) as infotainment (we will discuss this in more detail later). Rather, depending on the context, it is possible that an article would qualify as exhibiting at least some degree of infotainment if it were to embody even just one sub/characteristic (for example, if it embodied that sub/characteristic quite heavily).

Relatedly, the same article might embody characteristics of an infotainment style of communication as well as characteristics of other unrelated, or even opposing, forms and strategies of communication. For example, infotainment is often presented as the opposite of what we will refer to as the Golden Age style (often presented as the ideal, gold-standard style of modern journalism—and particularly hard news coverage—to which all news coverage should aspire; see Krause, Reference Krause2011; Schiller, Reference Schiller1979; Schudson, Reference Schudson2015). However, previous studies have suggested that rather than being mutually exclusive, both infotainment and Golden Age style attributes are often intermixed in news coverage—thus leading many infotainment scholars to argue that we should see the two more as a continuum than a dichotomous categorization (see Delli Carpini and Williams, Reference Delli Carpini, Williams, Bennett, Bennett and Entman2001) and to suggest that researchers of infotainment should not simply study the binary presence/absence of infotainment (or Golden Age) characteristics but should instead seek to gauge the relative prevalence/intensity of each style (and their characteristics) before making judgments about where the relative balance lies between the two.

Accordingly, in our study we also analyzed the existing literature in order to create an overarching definition of the Golden Age style and its key characteristics. We discuss this definition in more detail in the online appendix alongside our definition of infotainment. But in general, we define the Golden Age style of news coverage as characterized by a number of key features, including (1) a “strong orientation toward an ethic of public service” in journalism (Krause, Reference Krause2011: 96); (2) an understanding of journalism as playing a key “watchdog role” in the broader democratic system (Hallin and Mellado, Reference Hallin and Mellado2018); (3) a belief that a “professional distrust of sources” (Schiller, Reference Schiller1979: 56) is necessary, especially regarding governmental, corporate and public relations sources; and (4) a commitment to offering information in an “objective,” dispassionate, serious, investigative or analytical style (Brants and Neijens, Reference Brants and Neijens1998; Krause Reference Krause2011; Schiller Reference Schiller1979) while discussing/presenting substantive factual information and broader contextual analysis with the aim of aiding citizens’ own critical reflection and decision making (Brants and Neijens, Reference Brants and Neijens1998: 152; Hallin and Mellado, Reference Hallin and Mellado2018).

4.2 Mixed-methods discourse analysis

While there are many different methods that could be (and have been) employed to theoretically and empirically investigate infotainment, we believe that the ideal way to investigate the presence/absence/relative intensity of an infotainment style (as we define it) would be to employ a mixed-methods mode of discourse analysis. This is an approach that combines careful, rigorously structured, qualitative micro-level analysis of each news item (of a highly representative dataset of news articles) with a systematic process of coding those qualitative analyses in such a way as to allow for additional quantitative macro-analyses of the overarching trends in the dataset as a whole.

To achieve this, mixed-methods approaches must create a systematic process that guides the qualitative reading of each news item and allows the researcher to systematically record their findings for each news item. To do so, mixed-methods scholars must (1) create what is often called a codebook, which is simply a list of the questions that the researcher will pose to each news item, as well as the way they will be answered (for example, answers can be a predetermined list or left open); (2) choose the process they will use to capture and record (and later analyze) the results of their codebook-guided analysis of each news item; and (3) identify and construct a robust and representative dataset to be analyzed.

In terms of the details of our custom codebook itself, interested readers can consult a full copy of it—including an explanation and justification of each question, potential answers, and citations to other scholars whose work explains the relevance of the questions/answers—in the online appendix to this article. Several general features about the codebook are worth highlighting here, however. First, it was designed to produce results that would directly answer RQ1 and RQ2 by investigating all of the detailed characteristics/sub-characteristics included in our definitions of infotainment and the Golden Age styles. Second, to ensure that we measured not only the presence/absence of these elements but also the more nuanced question of their relative prevalence/intensity, the codebook included both yes/no presence/absence questions, as well as more holistic scale rating questions (designed to gauge the relative prevalence/intensity of the sub/characteristics and the infotainment and Golden Age styles overall). Third, it is relevant to note that the questions in the codebook were ordered in such a way that the researcher was asked to first examine and code for all of the specific sub-characteristics before being asked to render a holistic scale rating for the overall prevalence/intensity of a given characteristic and overarching infotainment / Golden Age style (the reason this ordering is important is because it ensures that the final overarching scale ratings are only done after, and thus with full knowledge of, the detailed analysis of the sub-characteristics—a practice that significantly increases the accuracy and reliability of the overall scale rating).

In terms of the process used to code and analyze the dataset, our method involved performing a close, qualitative reading of each individual news article from our dataset (each article was read at least two times), after which the researcher asked and answered each of the questions contained in the codebook.Footnote 3 Our coding answers (whether they took the form of choosing from a predetermined list or writing a detailed answer in response to an open question) were captured using the mixed-methods specific software QDA Miner 6.0—a coding platform that is widely used in mixed-methods discourse analysis research. Once we completed coding of all the articles in the dataset, we then performed a variety of further quantitative and qualitative analyses at the macro level to determine the overall key trends in the dataset.Footnote 4

Because we provide a substantial explanation and justification of our chosen case study and dataset in the online appendix, we won't discuss it in detail here. Some of the key characteristics, however, are as follows. First, we choose English-language, print (that is, newspaper) hard news coverage of the 2019 Canadian federal election as our case study. This case study was chosen not only because this type of news coverage remains highly relevant in contemporary Canadian political discourse but also because it represents a difficult case insofar as hard news coverage is the genre in which one would expect to find the least amount of infotainment (the implication being that, should we find a significant presence and intensity of infotainment in this case study, our findings cannot be discounted as of limited relevance and/or the result of a journalistic genre that is already predisposed to infotainment). Second, on the basis of this, we constructed a robust and highly representative dataset of English-language hard news print coverage by collecting all political news articles during the 41 days of the 2019 official election period from six newspapers (Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star, Montreal Gazette, Calgary Herald and Vancouver Sun). As a group, these include the three largest and agenda-setting newspapers in Canada while also representing significant ideological and regional/geographic diversity.Footnote 5 Our original search identified a total of 4,370 hard news articles. After eliminating redundant duplicate news items (that is, articles that were reprinted in more than one publication) and filtering according to three criteria—articles had to be hard news, rather than another genre (for example, op eds), they had to discuss the election more than tangentially, and the length had to be substantial enough to ensure equality across the dataset and allow for meaningful analysis—our final dataset comprised 969 separate and distinct news items. Given the centrality of the publications chosen and the breadth of articles retained, this represents an extremely rigorous and representative dataset—and one that is far larger and more detailed than most prior empirical analyses of infotainment.Footnote 6

5. High-Level Findings: Presence and Intensity of Infotainment in Canadian Political News Coverage

What did our analysis find? In section 6, we will offer a detailed breakdown of some of our key findings regarding the prevalence and nature of the main characteristics and sub-characteristics of the infotainment style. Before doing so, however, in this section we outline some of the high-level findings about the presence and prevalence of the infotainment and Golden Age styles more generally (especially as they relate to RQ1 and RQ2).

5.1 RQ1: Overall prevalence of infotainment

As we noted in the discussion of our methodology, because infotainment is a multicharacteristic phenomenon whose presence/absence and intensity are best judged holistically, we accorded each news item an overall holistic infotainment rating after having coded that news item for each of the main characteristics (and the associated sub-characteristics) that define our conception of infotainment and the Golden Age style. A scale of 1–5 was used, with a rating of 1 indicating that the article had “little to no infotainment characteristics present” and a rating of 5 indicating “very strong infotainment characteristics present.” Ratings of 2, 3 or 4 represented intermediate points between these poles, with the midpoint (3) being defined as showing evidence of “moderate infotainment characteristics present.” The results of our analysis can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Infotainment Scale results

There are a number of interesting conclusions to draw from this data. First, it is clear that a very large portion of Canadian political hard news coverage in newspapers embodies significant infotainment traits; 42.4 per cent of all articles, for example, were rated as a 4 or 5 on the Infotainment Scale—meaning that they demonstrated a significant degree of infotainment characteristics. Furthermore, 61.7 per cent of articles were rated as having at least some evidence of notable infotainment characteristics (meaning they were rated as either 2, 3, 4 or 5).

At the same time, our findings show that infotainment is not the only style used in political hard news in Canadian newspapers. While 28.9 per cent of articles in our dataset were rated as a 5 (highest) on the Infotainment Scale, 38 per cent of articles were rated as having virtually no infotainment characteristics (rating 1). Moreover, if 42.4 per cent of articles were rated in the two highest ratings of infotainment (ratings 4 and 5), another 48.7 per cent of articles were rated in the two lowest categories (ratings 1 and 2). As such, it is important to underline that our findings do not suggest that infotainment is the sole, or even the only dominant, style of political hard news coverage. Clearly, there is a substantial proportion of political hard news coverage in newspapers that do not follow the infotainment style.

While we will not discuss this in detail here (but will return to it in the conclusion), it is also worthwhile noting that a comparison of trends across the three publications also suggests some interesting findings. In general, there were not many significant divergences between the three publications. However, despite all being Canada-wide agenda-setting broadsheets, there were a few differences. Most notably at this macro level was the fact that hard news articles in the Postmedia network of newspapers were significantly more likely to embody infotainment characteristics than the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star. For example, a majority (51.9 per cent) of Postmedia news items were rated as high on the Infotainment Scale (a rating of 4 or 5), whereas a much lower proportion of articles from the Toronto Star (38.8 per cent) and the Globe and Mail (35.4 per cent) fell into these categories. This clearly raises a series of questions for further research.

Overall, however, what our findings unequivocally show is that (1) infotainment is very widespread and (2) political hard news coverage in Canadian national newspapers, taken as a whole, is roughly equally as likely to be characterized by a strong infotainment style as it is to be characterized by a non-infotainment style. Given the widespread perception and normative ideal of political hard news coverage in Canada as primarily analytic and informative (and the fact that most observers would suggest that these journalistic norms should, in theory, be a significant barrier to the adoption of infotainment style characteristics), the fact that our analysis clearly establishes that infotainment has become a significant and widespread style used in political hard news coverage in Canadian newspapers is a highly notable finding in itself.

5.2 RQ2: Attaining the infotainment “ideal”

If section 5.1 gives us a high-level answer to RQ1, additional analysis is required to answer RQ2. Recall that RQ2 essentially asks whether, when infotainment style characteristics are present in an article, other stylistic characteristics (in our case, Golden Age characteristics) can also be present. Or to state it slightly more precisely (since we measured the presence of infotainment on a 5-point scale rather than a simple present/absent binary), to what degree are other, non-infotainment stylistic characteristics (particularly those of the Golden Age style) present in articles that fall under each of the five ratings of the Infotainment Scale?

To investigate this question, we ensured that we rated every article not only through the lens of an infotainment style but also independently through the lens of the Golden Age style. These codes—as outlined in section E of our codebook—both identified the presence/absence of a number of specific characteristics of the Golden Age style and provided a rating (1–5) of the prevalence/intensity of the Golden Age style overall. This means that if an article had substantial Golden Age characteristics, these would be identified as present and the article would be rated highly on the Golden Age Scale even if it also had significant infotainment characteristics.

The value of doing this additional coding independent of our coding of infotainment characteristics (and the Infotainment Scale) is that it allowed us to test the degree to which Golden Age stylistic characteristics were distributed across each gradation of the Infotainment Scale. For example, if our results demonstrated that Golden Age stylistic characteristics were distributed relatively equally (or randomly) across the Infotainment Scale, it would show that it is entirely possible for an infotainment style to coexist with a Golden Age style, even within the same article. Conversely, if our results demonstrated that the highest intensity of Golden Age characteristics were found in articles with the lowest scores on the Infotainment Scale, this would suggest that, in practice, the more that an article is characterized by an infotainment style, the less likely it is to also embody characteristics of the Golden Age style.

Figure 2 shows the results of this analysis. Essentially the figure takes all the articles that we rated as falling in each of the five Infotainment Scale ratings and then breaks them down according to their rating on the 5-point Golden Age Scale. The horizontal axis (with the numbers 1–5) is the Infotainment Scale ratings, while each column above the numbers 1–5 represents the number of articles in each Infotainment Scale rating that fall into the five Golden Age Scale ratings. Thus, if every article that was rated 5 on the Infotainment Scale was equally distributed across the five ratings of the Golden Age Scale, what you would see is five equal columns above the number 5 on the horizontal axis. Conversely, if every article rated a 5 on the Infotainment Scale was rated a 1 on the Golden Age Scale, you would only see one column above the number 5 on the horizontal axis, with a colour indicating its nature as a 1 on the Golden Age Scale (as indicated in the Golden Age Scale legend at the bottom of the figure).

Figure 2 Distribution of Golden Age style across Infotainment Scale

So, what does this figure reveal? It clearly shows that the Golden Age Scale ratings are distributed very unevenly across the five Infotainment Scale ratings, with the bulk of the Golden Age Scale ratings falling into the poles of the Infotainment Scale (ratings 1 and 5).

If we examine the distribution of ratings more closely, the situation becomes even clearer. For example, the articles that are rated highest on the Golden Age Scale (rating of 5) were found almost exclusively in articles rated the lowest on the Infotainment Scale (rating of 1). Similarly, essentially all of those articles rated lowest on the Golden Age Scale (rating of 1) were found exclusively in articles that were rated the highest on the Infotainment Scale (rating of 5). These results also largely held true for the next level of ratings, with the vast bulk of articles rated second highest in Golden Age Scale (that is, 4) falling within the two lowest Infotainment Scale categories (that is, 1 and 2, with a few in 3). Similarly, virtually all articles rated second lowest in Golden Age Scale (that is, 2) were also rated in the highest two categories on the Infotainment Scale (that is, 4 and 5). Finally, articles that were rated in the middle of the Golden Age Scale (that is, a 3) were found in articles with an Infotainment Scale rating of 2 to 4.

Given our methodology, these findings do not prove causality (which is to say, that the presence of a strong infotainment style causes the absence of Golden Age stylistic characteristics). Nor do they prove a universal or theoretical law (for instance, that it is impossible to combine a strong infotainment style with a strong Golden Age style). What they do show, however, is that, empirically speaking, in our extensive hard news dataset (1) there were virtually no examples of articles that embodied both a strong infotainment and a strong Golden Age style; (2) the stronger the infotainment style was, the less present/weaker the Golden Age style was; (3) the weaker the infotainment style was, the more present/stronger the Golden Age style was; and (4) the only articles in which characteristics of both styles coexisted were articles where the intensity of both the infotainment and Golden Age styles were relatively moderate. As such, while our findings show no evidence of strong infotainment and strong Golden Age styles coexisting, they do suggest that it is possible for hard news articles to combine moderate degrees of Golden Age characteristics with moderate degrees of infotainment characteristics.

6. Detailed Findings: The Nature of Infotainment in Canadian Political News Coverage

If section 5 outlined our high-level findings regarding the existence of infotainment and Golden Age styles in political hard news coverage in Canadian newspapers, it did not provide much insight into the specific nature of the infotainment style itself within our dataset. Given that infotainment has a number of different aspects—not all of which are always equally dominant in different spheres/countries—our study also sought to understand the specific nature of infotainment in our dataset at a more granular level: Were all of the three main characteristics of our definition of infotainment equally present? Or were some of them more/less dominant? And within each characteristic, which sub-characteristics were the most important? Answering these questions in order to offer a more nuanced picture of the nature of infotainment in Canadian political news coverage is thus the goal of this section.

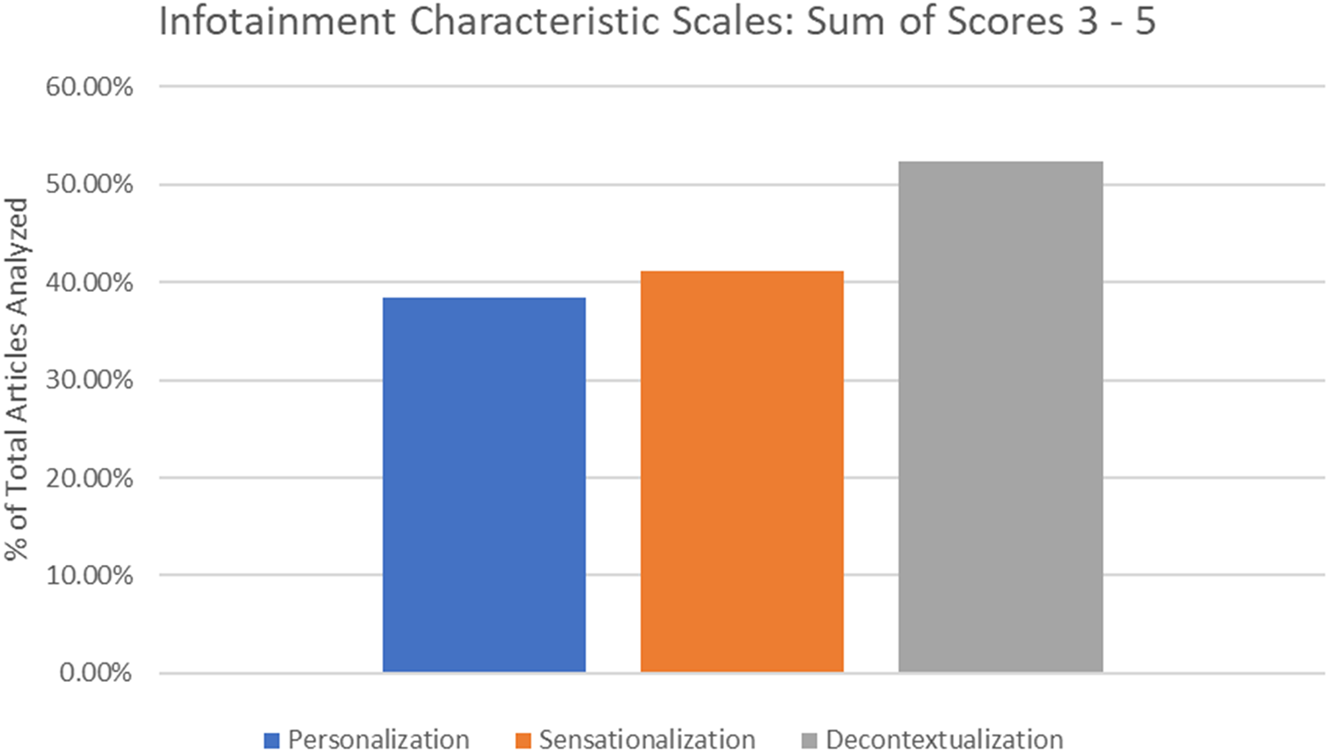

Let us begin with the question of the relative prevalence of each of the three macro-characteristics. As discussed in the methods section, our core definition of the infotainment style identifies practices of personalization, sensationalization and decontextualization as the three key macro-characteristics of infotainment. As these characteristics can be embodied to varying degrees in different articles, we not only asked a yes/no question about whether each characteristic was present but also rated the intensity of the presence of each of these three characteristics individually on a 5-point scale (with 1 being “little to none” and 5 being “highly prevalent”). Figure 3 outlines the relative prevalence of each characteristic by showing the percentage of all of the articles in our dataset (regardless of where they rated on the Infotainment Scale) which were rated as a 3, 4 or 5 (ratings that are indicative of a relatively strong prevalence of that characteristic).Footnote 7

Figure 3 Infotainment—main characteristics

As is clear from the figure, we found that the prevalent characteristics of personalization and sensationalization were roughly equally present in our dataset (in approximately 40 per cent of all articles, with approximately 26 per cent falling into the 4 and 5 ratings). In comparison, the characteristic of decontextualization was strongly prevalent in more than 52 per cent of all articles (with almost 40 per cent of all articles falling into the 4 and 5 ratings).

Interestingly, there are relatively few notable outliers between publications in terms of the overall ratings for these three characteristics. In general, when broken down by publication, the “characteristic” results mirror what we found when we tested the overall prevalence of infotainment generally (as discussed in section 5.1)—with Postmedia publications demonstrating higher levels of infotainment overall, as well as higher levels of each of the specific three characteristics that define infotainment. The one notable difference was that Postmedia employed decontextualization at even higher rates than what its overall higher prevalence of an infotainment style would suggest. However, none of these results fundamentally distinguished the Postmedia results from the others, meaning that there are no significant outliers in publications.

But which sub-characteristics drive each of these three main characteristics? This is the question to which we turn next.

6.1 Personalization

As discussed in section 4.1, personalization is one of the main characteristics of our definition of infotainment and, as noted just above, was moderately to strongly present (a rating of 3–5 on the Personalization Scale) in just under 40 per cent of the dataset. To better understand the detailed nature of this characteristic, we also coded for the presence/absence of the four sub-characteristics discussed in section 4.1. As seen in Figure 4, one sub-characteristic was far more prevalent than the other three.

Figure 4 Personalization sub-characteristics

In fact, the sub-characteristic of personalizing the political context by contextualizing political coverage with personalized information, frames and materials was by far the most dominant sub-characteristic, present in almost half of all articles. In comparison, the second most prevalent sub-characteristic (the anchoring of interpretations of political events, issues and developments to individual persons—for instance, politicians—rather than through reference to broader frames of reference, perspective, or social relevance) was present in just over 19 per cent of cases, while the third most prevalent sub-characteristic (the celebrification of politics and politicians) was present in approximately 13 per cent of cases. As such, our findings suggest that the two first framing techniques served together to shift substantive discussions of policy debates and the context of political issues and events toward personalized frames of reference focused on individual politicians, their strategies, looks and feelings, and their place and role within the broader electoral landscape and competition.

6.2 Sensationalization

The second component of our tripartite definition of infotainment—sensationalization—also played an important, but not dominant, role in Canadian newspapers’ infotainment style, being moderately to strongly present (a rating of 3–5 on the Sensationalization Scale) in just over 40 per cent of all news items. To better understand how this characteristic functioned, we also coded for the presence/absence of the five sub-characteristics discussed in section 4.1. Figure 5 summarizes our findings—revealing that the bulk of sensationalization is driven by two main sub-characteristics: the presentation of sensational political conflict (present in 36.6 per cent of all cases) and sensational narratives and emotional primers (present in 30.1 per cent of all cases). That said, the sensational presentation of scandal is also a relatively frequent sub-characteristic, with evidence of such characteristics found in roughly one-fifth of coverage (present in 19.8 per cent of cases).

Figure 5 Sensationalization sub-characteristics

Two further findings are perhaps also worth noting. First, in terms of any differences between the three publications studied, we were surprised to find that, in contrast to the results for all of the other characteristics where Postmedia newspapers rated consistently higher than both the Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star, we found that the Toronto Star used sensational narrative structures/emotional appeals significantly more than the Postmedia newspapers (39.4 per cent to 29.8 per cent) and presented conflict in a sensationalized manner roughly equally frequently to the Postmedia newspapers (38.4 per cent to 40.1 per cent). This raises interesting questions for further investigation.

Second, although we don't have space to discuss it at length here, it is perhaps worth noting that based on our qualitative reading of the data, the sensational coverage of scandal might be viewed to play a more important role than a purely quantitative analysis of frequency might suggest. Namely, scandals were invoked (and often reiterated) not only throughout the election campaign but also more generally within the infotainment style in ways that arguably formed a key meta-narrative within the overall political coverage. In particular, sensational coverage of scandals usually occurred in articles that also tended to lack informative and substantive details on broader policy, social, political and economic issues and perspectives. This, in turn, meant that the focus on, and repetition of, coverage of scandals (and those involved in them) became the primary contextualizing frames for these articles’ coverage of the election campaign and rendered any discussion of the more substantive contents of the campaign virtually invisible. As such, even though the prevalence of the characteristic of sensationalism is roughly the same as personalization, we believe it might play a more important role than its mere frequency would suggest.

6.3 Decontextualization

Finally, there is the characteristic of decontextualization. Before we discuss the sub-characteristics of decontextualization, it is important to note that although we treat decontextualization as its own characteristic, it is also inextricably woven into the other dimensions of infotainment. This is because our findings revealed that decontextualization is not only an overarching and complex component of the infotainment format in CEL newspapers’ election coverage but also, ultimately, the most fundamental component of it.

What do we mean by this? Partially we mean it in the straightforward sense of acknowledging that, as noted above, the specific characteristic and sub-characteristics of decontextualization are the most frequently present of all the main and sub-characteristics: it was moderately to strongly present (a rating of 3–5 on the Decontextualization Scale) in 52.3 per cent of all news items, while being totally absent (a rating of 1 on the Decontextualization Scale) in only 35 per cent of all news items—a much lower proportion than the other two.

However, by calling it the most “fundamental” component of infotainment, we also want to underscore the fact that many of the sub-characteristics of the other two characteristics (for example, personalized information and context, as well as sensational frames, narratives, language and primers) almost inevitably function to displace and replace substantive and contextualizing information on concrete political issues, debates, and so forth. In this sense, even when there are no other specific sub-characteristics of decontextualization at play, the infotainment characteristics of personalization and sensationalization work to decontextualize news coverage. Understanding this, then, is crucial to understanding how infotainment works.

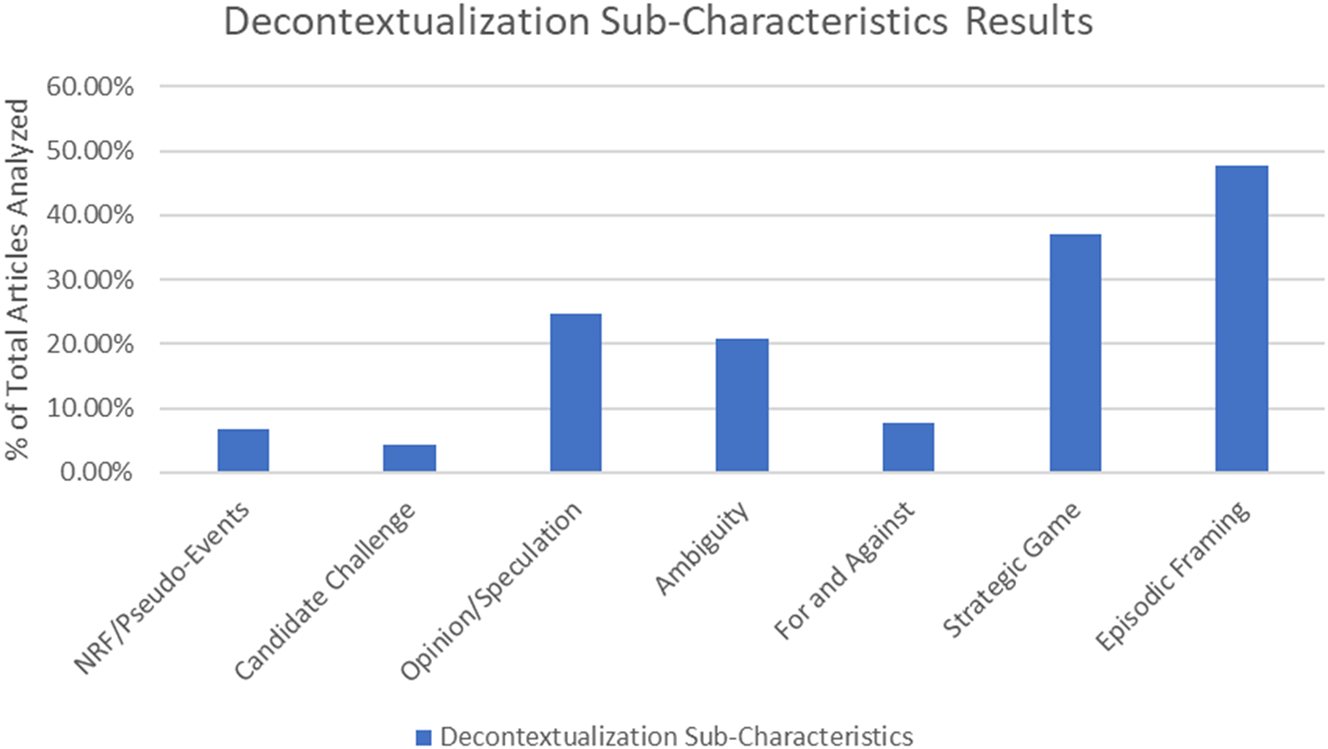

Returning to the question of the driving sub-characteristics of decontextualization (Figure 6), we find both some interesting overall findings and some significant nuance between the different newspapers.

Figure 6 Decontextualization sub-characteristics

In this figure, we can clearly see the prevalence of the techniques of representing politics through the use of unanchored episodic framing (47.8 per cent) and the lens of politics as a strategic game (37 per cent). However, the fact that more than 25 per cent of specific decontextualization instances result from the inclusion of unsupported opinion and speculation (a proportion that was relatively consistent across all publications)—and that over 20 per cent of news items even in hard news political reporting include ambiguous information without any identifiable effort to clarify it—is quite remarkable and reminds us that questions of misleading perspectives or “disinformation” are not simply limited to social media, nor the media spheres in other countries, and thus merit broader explorations within legacy media.

Furthermore, it is also notable that Postmedia newspapers rated significantly higher than their competitors on the Decontextualization Scale overall (with Postmedia having a significantly higher proportion of articles rated a 4 or 5 than the two other papersFootnote 8) and had a higher level of a number of the sub-characteristics (particularly strategic game framing, at 43.7 per cent; episodic framing, at 64 per cent; and ambiguity, at 27.4 per cent).

Finally, it is worth highlighting that these findings are also relevant in relation to RQ2 (regarding whether an infotainment style can coexist with other styles, namely the Golden Age style). For while it is not difficult to imagine how the two other characteristics of infotainment might, in theory, be capable of coexisting with some types of Golden Age style analysis, by its very nature, decontextualization implies the absence of the type of substantive and contextual information and analysis that is both central to the Golden Age style and, arguably, must be present to allow readers to make their own informed analysis of political developments, debates, issues, policies, and so on. The very strong presence of decontextualization, then, might also help explain the stylistic distribution we found in section 5.2. For if decontextualization is at the heart of the infotainment style in Canadian political hard news, and it is fundamentally incompatible with the Golden Age style, this might partially explain why there is virtually no overlap of strong infotainment style characteristics with strong Golden Age style characteristics (although it would, of course, require more research to fully validate this hypothesis).

7. Conclusions

Although media, journalism and communication scholars have conceptualized and empirically researched the phenomenon of infotainment for decades—and despite significant evidence suggesting the impact that the nature of media coverage can have on influencing elections, propagating mis/disinformation and shaping other politically relevant issues and events—political scientists have largely failed to examine the presence of infotainment in, and its relevance to, contemporary politics. In this context, the goal of this study was threefold: (1) to offer a robust definition of infotainment that incorporated the main features that have been employed in the existing literature; (2) to develop a systematic and rigorous method that operationalized this definition; and (3) to use this definition and methodology to measure the presence, intensity and nature of infotainment in Canadian political hard news coverage.

The first notable contribution of this article, then, is related to our first two goals. For by outlining a clear, strongly justified and fully operationalizable conceptualization and definition of infotainment, as well as developing a rigorous method of measuring the presence and nature of infotainment, we have created a theoretical framework and methodological approach that both we and other scholars can use to investigate infotainment within and beyond Canada.

The second notable contribution of this article is its empirical findings regarding the presence, intensity and nature of infotainment in political hard news in Canadian newspapers. Some of the most important empirical findings are as follows:

• In contrast to the (still common) belief that hard news remains largely structured by the Golden Age standard (which, by its very definition, excludes infotainment characteristics), we found that more than half of all hard news articles we examined showed clear evidence of substantial infotainment traits—with more than 51 per cent of all articles demonstrating moderate to very strong presence of infotainment characteristics (a rating of 3–5 on the Infotainment Scale) and with 42 per cent of all articles demonstrating strong to very strong presence of infotainment characteristics (a rating of 4 or 5). These results clearly establish that the infotainment style was a significant and widespread feature of the political hard news coverage in our dataset—and far exceeded what we (and most other observers) would have expected to find.

• At the same time, we also found that despite some observers’ contention that all news coverage has become nothing but infotainment, a very significant percentage (48.7 per cent) of the news articles in our dataset embodied few to no infotainment characteristics—with approximately 38 per cent showing no evidence of infotainment (rating 1) and another 10 per cent only showing evidence of few infotainment characteristics (rating 2). These results mean that while infotainment was a significant and widespread style used in contemporary hard news coverage, it is certainly not the only style employed in hard news coverage in Canada.

• At a more detailed level, we found that while two main characteristics of infotainment were roughly equally present (with personalization being moderately to strongly present in approximately 38 per cent, and with sensationalization being moderately to strongly present in approximately 40 per cent of all news items), the characteristic of decontextualization was the most prevalent (being moderately to strongly present in more than 52 per cent of all news items). We also noted that for a variety of qualitative reasons, the characteristic of decontextualization (and possibly sensationalization) might be even more impactful and important than the quantitative prevalence alone would suggest.

• Our analysis of the sub-characteristics also resulted in a number of interesting findings, including (most notably) the surprisingly strong prevalence of the use of unsupported opinion/speculation and ambiguous information, as well as the use of episodic and strategic game framing.

• Finally, our analysis showed very clearly that while it is theoretically possible for infotainment and Golden Age stylistic characteristics to coexist in the same news article, the vast majority of articles in our dataset were dominated by one style, with the other being almost entirely excluded. The only cases, moreover, in which both significant infotainment and Golden Age style characteristics coexisted were articles where the presence of both styles was rated as “moderate.” Both of these findings reinforce the same relationship; however, in our dataset, the stronger the intensity of infotainment, the weaker the intensity of the Golden Age style (and vice versa).

We believe that these conclusive findings are important in their own right, as they address an important gap in the existing literature by offering a snapshot of the prevalence and nature of infotainment (and the Golden Age style) in a media format (hard news in CEL newspapers) covering an important political event (the 2019 federal election) in Canada. However, we also believe that our findings suggest other important and broader implications, hypotheses and questions. For example:

• On a methodological level, we believe that our approach offers a strong overall methodological foundation for exploring the phenomenon of infotainment in many other media/contexts (even if the specific methodological tools and dataset choices would need to be adapted to those specific media/format/linguistic contexts).

• Given that our dataset included the most widely read and agenda-setting newspaper publications in Canada and embodied significant regional and ideological diversity/mainstream representativity, we believe that it is quite plausible to hypothesize that our major findings are not unique to the 2019 election, the newspapers examined, the newspaper sphere by and large, or even to hard news coverage itself.

• In contrast, we believe that our major findings regarding the prevalence and nature of infotainment would likely be replicated (or strengthened) in future studies of hard news political coverage in other major (English-language) broadsheet newspapers in Canada.

• Similarly, given what the existing literature suggests about the higher levels of infotainment in other genres and formats, we would hypothesize that future studies would likely find an even stronger presence of infotainment characteristics in other newspaper genres (for instance, op eds, columnists, soft news, non-news genres that touch on politics) and other media formats (such as tabloid newspapers, TV, radio, social media).

While these hypotheses suggest a variety of avenues for future infotainment research, our findings also raise a host of other empirical questions about which our study does not provide hypotheses. For example, would our findings be replicated in the hard news coverage in French (as well as other non-English) language newspapers? Would the level of the political issue (municipal, provincial, national, international) have any impact on the prevalence of infotainment? Would we find different dynamics outside of an electoral campaign?

Our findings also raise some significant normative questions. The idea that free and well-functioning political debate is a critical component of democracy has been at the heart of almost all conceptions of democracy since ancient Greece. During the twentieth century in particular, political journalism became one of the key mechanisms ensuring that citizens have access to the type of information and analysis that are viewed as necessary for citizens to develop the informed opinions that democracies require to remain healthy and functional. While the onus for ensuring that citizens are, in fact, well informed cannot fall entirely on the news media, this responsibility is nonetheless still generally regarded as intrinsic to the medium itself. In this context, if even the most traditional of political hard news coverage today not only frequently employs infotainment stylistic characteristics but also employs them largely to the exclusion of those of the Golden Age style, this raises a variety of questions about the potential impact of this style not only on the concrete outcomes of specific contemporary electoral contests but also on the broader nature of contemporary democratic deliberation, its civic role and, perhaps, the privileged role of journalism within our democratic institutions.

Finally, one significant question for political scientists concerns the degree to which contemporary political actors may be altering their core substantive content (for example, policy preferences; legislative tactics and strategies; philosophical and ideological principles; ethical commitments and standards; outreach, recruiting and mobilization techniques; and so on) to better accommodate the infotainment style that increasingly bears the hallmark of a dominant media culture or logic. Scholars have suggested that the ways that different media structure their communications (for example, the repeated and predictable use of certain formats, styles and logics in communicating their stories, information, and so on) accumulate to produce a broad set of stylistic rules (or media culture) to which other institutions (including political parties and political journalists) increasingly adapt (Altheide Reference Altheide2004: 294). In fact, Sampert et al. (Reference Sampert, Trimble, Wagner and Gerrits2014) have argued that there is strong evidence that Canadian political actors are increasingly adapting/tailoring the development and communication of their political perspectives and policies to better accommodate the dictates of the media formats, genres, and so on, of the prevalent media logic/culture. If these perspectives are accurate, then our findings suggest that we may be facing a situation in which not only the strategic electoral campaign choices of political actors (for example, what issues to prioritize during the campaign, how to communicate their policies) but also their core commitments (for example, policies, values, goals) are being increasingly influenced (whether consciously or semiconsciously) by judgments about the degree to which they can be easily communicated and performed within an infotainment style.

All of these are important and pressing questions. As such, we hope that by revealing the degree to which infotainment characterizes even the hard news coverage of Canadian politics, our work will encourage additional study and evaluation of this phenomenon in Canada and beyond.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423923000586

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge that this article draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.