Not too long ago we lived in a world of democratic optimism. The dream of a global order where authoritarianism was an increasingly rare form of rule seemed realizable as dictatorships crumbled in region after region—Southern Europe, Latin America, Eastern Europe, East Asia, Africa and, even for a spring moment, the Middle East. And in established democracies the reactionary anti-democratic right had not been a serious contender for power since the end of the Second World War, except perhaps in Austria. The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe had also worked to undermine the viability of an anti-democratic left.

Latin America had moved from a region seen as prone to chronic military coups to one that was almost universally democratic.Footnote 1 In no time at all, or so it seemed, Castro would pass in Cuba, and things could be set right in Haiti. Though Latin American democracy was far from perfect, progress was being made in several countries on such nagging problems as poverty and persistent violent insurgency. The new challenges to democracy were not whether the colonels would stay in the barracks, but rather the weakness of horizontal accountability, the full integration of indigenous populations, and the strengthening of the rule of law.Footnote 2

Clearly we were too optimistic. Today Venezuela, historically one the region’s most durable democracies, has collapsed into dictatorship and a profound humanitarian crisis. President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua has amended the constitution to allow himself a third presidential term. The one-time guerilla leader of the Sandinista Front for the Liberation of Nicaragua has a personal fortune estimated at $50 million, and stood for office with his wife as his vice-presidential running mate in 2016. He has moved from building socialism to crony capitalism. And in Brazil, the region’s biggest economy and dominant power, almost all important political forces seem discredited by allegations of corruption.Footnote 3

In Europe, fun was once poked at the retrograde communist-style dictatorship of Belarusan President Alyaksandr Lukashenka, who was said to rule “the last European dictatorship.”Footnote 4 Triumphalism in Europe was grounded in confidence in the future of the European Union, which by incorporating sets of states further removed from its West European core, would presumably share the blessings of consolidated democracy, universal respect for human rights, and higher living standards. This seemed attainable in our lifetimes—at least, until the rise of Putin, the Euro crisis, Brexit, and the backlash against a massive influx of refugees shattered the dream.

Perhaps Lukashenka was merely the first of a new wave of petty dictators. Since the current European crisis, Poland and Hungary, two of the poster children for EU adoption, have experienced substantial backsliding with the latter perhaps even having fully regressed to authoritarianism. Even more disturbing is the rise of rightwing populist parties and movements in almost all the core countries of the EU. And in some cases they are in government, such as the Freedom Party in Austria, and potentially the Northern League in Italy.Footnote 5 It would appear that the enduring political lesson of World War II—that overt racist and xenophobic leaders are the road to catastrophe—has been, with the passing of the generations, unlearned by larger and larger parts of the populations even in developed countries that experienced the worst of the conflagration.

Authoritarianism persists in two different ways. First, countries that have alternated between periods of unconsolidated democracy and dictatorship continue to oscillate between these two dominant forms of modern rule—e.g., Venezuela, Nicaragua, Hungary, and Turkey. In this sense we seem to be in a reverse wave in the global movement of regime types over time. The problem of these waves and counter-waves of regime change is addressed in one of the articles in this issue of Perspectives, “Democratic Waves in Historical Perspective,” by Seva Gunitsky. He pays careful attention to the international dimensions of waves of regime change, both in terms of sources for the impetus of the changes and their strength. The issue of international regime diffusion is also a component of the current resurgence of authoritarianism, in particular, the weakening of the role of the United States in upholding international norms. This development harkens back to the nightmare of the interwar era where revisionist powers undermined the global liberal order because of the withdrawal of the United States from collective security arrangements.Footnote 6

Second, we are seeing a disturbing rise in authoritarian movements and parties that take anti-system or semi-loyal positions on the political spectrum. In this sense, that part of the literature on populism which sees populist parties as playing by the rules of the democratic game underplays its threat. These movements are truly reactionary, and are stoked by the kind of status anxiety that accompanies authoritarian change. Their scapegoating of foreigners and globalization is a convenient way to displace the real culprit for the loss of positional security—the concentration of wealth in almost every country—onto convenient external enemies.

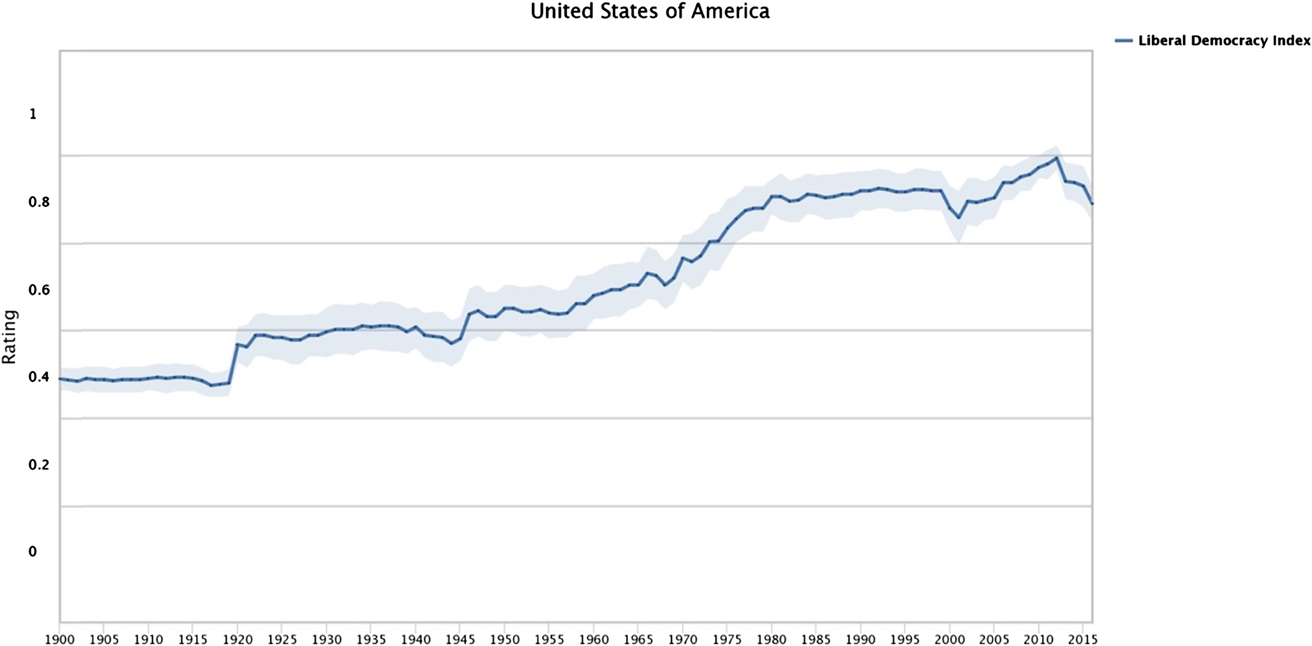

And in the United States, following the election of our first African-American president, we are certainly witnessing a new round of the rise of authoritarian political forces and attitudes. In this sense, the current crisis in the United States is very typical of other OECD countries. Our president finds allies and kindred souls in the likes of Nigel Farage, Marine Le Pen, Vladimir Putin, and Rodrigo Duterte. Historians and scholars of American Political Development have long noted the cyclical nature of American politics, that we alternate between periods of greater tolerance and incorporation and backlash against it. We are again in a period of heightened conflict between what the Pulitzer-Prize-winning American historian Jon Meacham describes as the “the battle for our better angels.”Footnote 7 With record levels of immigration and gilded-age levels of inequality, the backlash against the legacies of Barack Obama has put our democracy at its greatest level of risk since the Civil War. The warning signs that American democracy is under threat are apparent to anyone who has read the literature on democratic breakdown or deterioration.Footnote 8 Figure 1 shows the decline in V-Dem’s measure of liberal democracy in the United States in recent years. Since peaking in 2012 U.S. liberal democracy has regressed in 2016 to the level it was at in the mid-1970s.

Figure 1 Liberal democratic advance and decline in the United States, 1900–2016

Notes: Latent variable point estimates with 90% confidence intervals.

Generated with the V-Dem country graph on-line analysis tool. Available at https://www.v-dem.net/en/analysis/CountryGraph/; accessed May 10, 2018.

Source: Coppedge et al., 2016

In this issue we have several pieces that address new directions in the study of authoritarianism, both as a form of rule and as a tendency within publics. The first of these, “Legitimacy in Autocracies: Oxymoron or Essential Feature?” by Johannes Gerschewski, discusses the bases of authoritarian stability. Much of the literature on new forms of authoritarianism drew inspiration from rational choice understandings of regime dynamics that were indebted to economic logics. Thus much of the most influential literature omits a discussion of the normative basis for support of authoritarian rule by citizens. Gerschewski raises the issue of the fundamental nature of the attempt to secure normative legitimacy by all regimes and discusses how the ability to do so is an advantage with respect to long-term stability and survival. He thus shows that moral commitments have as big a role to play in understanding authoritarian stability as credible commitments based on material interests.

In “Domination and Disobedience: Protest, Coercion, and the Limits of an Appeal to Justice,” Guy Aitchison challenges the notion that coercive forms of disobedience from below are only legitimate when protest is directed against authoritarian regimes. Arguing that such a view ignores the role of social power and material interest in shaping political outcomes, Aitchison offers instead a principled defense of coercive forms of disobedience in both democratic and semi-democratic societies. He defends this position on the basis of democratic republican principles—as a means of resisting certain forms of unacceptable domination—but is also careful to delineate a range of constraints on the use of coercive resistance tactics in democratic societies.

The third way in which authoritarian regimes secure compliance, beyond economic incentives and moral suasion, is through the use of coercive sanctions. Whereas coercion from above is often quite effective in the short-term, it can have long-term deleterious effects in terms of the ability to cultivate moral rationales for support. In “‘Thugs for Hire’: Subcontracting of State Coercion and State Capacity in China,” Lynette Ong documents and explains the logic behind the increasing use of criminals by local state authorities in China to do their repressive dirty work. By not employing state resources, local elites can avoid direct culpability for repression, yet Ong shows how this is emblematic of a weak state that is increasingly subject to capture by the criminal elements it employs. It remains an open question whether such tactics will contribute to authoritarian stability or are a further step in the erosion of state capacity.

Caterina Froio, in “Race, Religion or Culture? Framing Islam between Racism and Neo-racism in the Online Network of the French Far Right,” dives deep into the public sphere activity of xenophobic movements in a long-established, highly developed democracy. Making use of the far right’s attempts to reach supporters via the Internet, she explores how the presentation of Islam is used to frame national identity in an exclusive fashion. While she does continue to see elements of old-style pseudo-biological racism (asserting racial superiority), she also finds a neo-racist tendency that asserts that Islam is incompatible with French secularism, and thus attempts to move racism from the fringe to the mainstream of French national culture. This is emblematic of the emergence of neo-racist ideologies globally that reject immigrants as suitable citizens due to a supposed incompatibility of cultures.

Finally in this section, Aila Matanock and Paul Staniland discuss how organizations contesting state power can and often do pursue parallel democratic and authoritarian strategies in their quest for power. In “How and Why Armed Groups Participate in Elections,” the authors confront this common but not fully explored political phenomenon and develop a set of concepts that allow them to map variation across cases and to hypothesize about the factors that lead to different strategies by different groups. This innovative article promises to set a research agenda to make sense of how and why some political groups contest power by both democratic and violent means simultaneously.

Other Content

In addition to the piece by Seva Gunitsky discussed earlier, we have two other articles and two reflections in this issue. Our cover article, “Keeping Vigil: The Emergence of Vigilance Committees in Pre-Civil War America,” by Jonathan Obert and Eleonora Mattiacci, is part of the broader effort of political scientists to make sense of the American past using the theories and methods of the discipline. They show how in the flux of the social frontiers during American expansion across the continent, citizens often took authority into their own hands, especially where there was ethnic heterogeneity and recent institutional reform. They argue that vigilantism became a means to create and enforce civic political identities and not just a functional substitute for weak state power.

In making sense of the plight of Syrian refugees in “When Do the Dispossessed Protest? Informal Leadership and Mobilization in Syrian Refugee Camps” Killian Clarke returns to one of the perpetual big questions we face in the discipline. He shows that despite meager material resources and lack of sympathetic allies in host countries some refugees nevertheless organize to fight for a better life. By conducting comparative fieldwork in camps located in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, Clarke uncovers informal leadership networks in Jordan that allow the refugees to effectively mobilize, and pinpoints the structural conditions that promote this outcome by leveraging variation among the three cases.

Finally we continue to publish on a topic we wish were less critical to cover: the ethics of research. In this issue we have two reflections from two prominent scholars considering how to avoid making poor choices that can morally compromise the research enterprise. Aili Mari Tripp discusses how the push for greater research transparency poses very substantial moral dilemmas for researchers who do fieldwork in authoritarian contexts. She points out that while transparency is a desirable outcome, it needs to be carefully balanced against other essential and more important values such as the well-being of our research subjects. Scott Desposato presents the results of his survey of subjects and scholars on the ethics of field experiments. His findings show that subjects of experiments, as well as a majority of the members of the discipline, strongly disapprove of treating subjects without their consent. He argues that this is an important moral qualm concerning field experiments that needs to be addressed.

Innovations and Thanks

Our publisher, Cambridge University Press, has teamed up with the Qualitative Data Repository at Syracuse University to integrate the “Annotation for Transparent Inquiry” system into the online version of the journal. This software allows researchers to link article text with expansive annotation and available online source material.Footnote 9 Our first article employing this new capability will appear in our next issue. Authors wishing to make use of the system will be encouraged to do so, though of course its use is not compulsory.

The call for papers “Trump: Causes and Consequences” was very successful, attracting over ninety submissions. Their processing was a time consuming and exhausting endeavor, especially given the scholarly proclivity to submit things as close to the deadline as possible. It took a full month to process all of the manuscripts, and the best of them are now out for peer review.

June 1 marked our first anniversary editing the journal and this issue, 16(3), is the fourth we have produced on our own. We wish to thank our publisher, Cambridge University Press, and our sponsor, the American Political Science Association, for their support, suggestions, and trust in us. This gargantuan task would not be possible without the support of the administration and our staff at the University of Florida. Thanks are due to David Richardson, the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and Daniel Smith, Chair of the Department of Political Science. Our editorial assistants—Alec Dinnin, Karla Mundim, Nicholas Rudnik, Marah Schlingensiepen, Dragana Švraka, and Saskia van Wees—have worked tirelessly and effectively for the journal with nary a complaint. We also express our thanks to vast numbers of colleagues both nationally and internationally who have submitted their work, and reviewed the manuscripts and books of others. We owe the quality of the journal to the hive mind of the discipline. Finally, none of this would be possible without our indefatigable managing editor, Jennifer Boylan, who has masterfully learned and helped build the multiple systems for the production of the journal, and seems to intuitively ascertain what we need to do to avoid problems, even before we are conscious of the need to address them in the first place.