Epigraph

[National education] means the so framing the mind of the individual, that he may become a useful and virtuous member of society in the various relations of life. It means making him a good child, a good parent, a good neighbor, a good citizen, in short, a good man… Of all the knowledge that can be conferred on a people, this is the most essential; let them once understand thoroughly their social condition, and we shall have no more unmeaning discontents – no wild and futile schemes of Reform; we shall not have a stack-burning peasantry – a sturdy pauper population – a monopoly-seeking manufacturing class; we shall not have a middle class directing all their efforts to the repeal of a single tax, or to the wild plan of universal robbery; neither will there be immoral landlords wishing to maintain a dangerous corn monopoly; or foolish consumers, who will suffer it to remain. We shall have right efforts directed to right ends. We shall have a people industrious, honest, tolerant and happy.

(Mr Roebuck, House of Commons Debates, July 30, 1833: vol 20 cc139-74).

Introduction

A year after the historic Parliamentary Reform Act of 1832 and on the eve of a period of immense state building never seen before or after in the UK, liberal members in parliament (MPs) were championing the cause of free, compulsory, secular state schooling. Inflected with the utopian ideals of Robert Owen as well as the principles of utilitarian and rational governance of Jeremy Bentham, arguments like Mr. Roebuck’s (see Epigraph) vested vast political potential in national education (Itzkin Reference Itzkin1978). For Roebuck, state schooling would prevent discord and revolution, solve poverty, check political radicalism, as well as disrupt dramatic class and wealth inequality. An education in state schools would create the “good man” with positive effects in all stages of life and for all social roles. Indeed, with a system of state schooling, Britain would “have right efforts directed to right ends… a people industrious, honest, tolerant and happy.”

Of course, such an ecstatic vision of collective deliverance never came to be – in Britain or elsewhere. And no such schooling system as Roebuck proposed had ever existed in Britain, nor would in earnest until the Fisher Act of 1918, when primary and secondary schooling were centrally integrated with tight linkages to the emerging higher education system. Yet, Roebuck’s vision of the heightened centrality of a public education in promoting greater opportunity for individual empowerment and self-actualization as well as greater social justice and prosperity nonetheless stuck and resonate even today (Boli et al. Reference Boli, Ramirez and Meyer1985). Why? How did state schooling come to take on such expansive and persistent political meaning and salience during the nineteenth century?

Existing explanations of the state’s intervention in education are centrally organized around the purpose-built character of state schools. For example, these accounts underscore the sea changes in Western society that unfolded during the course of the nineteenth century and the need for states to respond with mass schooling (Craig Reference Craig1981). For example, according to these perspectives, schools were needed to inculcate pro-social values among the pluralizing, densifying populations in urban centers (Pooley and D’Cruze Reference Pooley and D’Cruze1994); to teach basic literacy and numeracy so as to meet the heightened demand of semi-skilled labor during the course of industrialization (Sanderson Reference Sanderson1995); and to promote citizenship and civic education of an increasingly enfranchised and self-governing nation (Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Keating Reference Keating2009). In other words, states erected schooling systems because they met the needs of a capitalist, industrial, democratic society.

Such explanations or their critical variantsFootnote 1 rest on a strong assumption that a system of state schooling presented itself to British statesmen as the natural and self-evident technical solution to the problems facing them in the nineteenth century. In contrast, the current article proceeds with the assumption that sending children en masse to “dark, humid, crowded, unventilated, unfurnished, unlit, unheated… unwelcoming, and ugly” schools with untrained, child-teachers was an unnatural act (E. Weber Reference Weber1976: 304). And the belief that doing so was within the nineteenth-century state’s prerogative and would create a society of consummate progress and justice was stranger still. Indeed, this paper takes as its chief task exploring how such narratives of schooling’s functional role in society became so naturalized and how they came to have powerful influence in framing how the political elite such as Mr. Roebuck articulated, debated, and even came to manage the “social question” (Rueschemeyer and Skocpol Reference Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1996).

I build on an ongoing tradition of macro-sociological work that contextualizes these functionalist theories of schooling’s role in society against the emergent cultural models that reshaped the contents and programs of the nineteenth-century national state, particularly with regard to education (Smith Reference Smith2022, Reference Smith2023; Meyer Reference Meyer and Steinmetz1999; Ramirez and Boli Reference Ramirez and Boli1987). In this paper, I treat nineteenth-century “functionalist” theory and “functionalism” as a cultural narrative about society. These nineteenth-century cultural narratives emphasized the rational, bureaucratically elaborated state; the coherence of national society as an aggregation of individuals; the interiority, rationality, and agency of the individual; and how these naturally and orderly functioned together (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas, George Thomas, Ramirez and Boli1987).Footnote 2 Specifically, I argue that the emergence and institutionalization of the “social sciences” – the antecedents of the contemporary social sciences, then still integrated, explicitly normative, quasi-empirical and fixated on social order and reform – was an expression and mechanism of intensified cultural rationalization across the Western system in the nineteenth century. As part of this emergence and institutionalization, the functionalist social theories of the nascent “social sciences” became increasingly reified with new forms of societal data and statistical models, lodged within universities (Wittrock Reference Wittrock, Rothblatt and Wittrock1993), journals, and associations, as well as further integrated into the state itself – an international epistemic movement I call social scientization. Social scientization heightened these theories’ status as authoritative cultural accounts about the social world and in the process became increasingly influential on and embedded in the politics of education and schooling (Hall Reference Hall1993; Somers Reference Somers1995).

To test this argument, I use natural language processing techniques as well as network, discourse, and generalized least squares (GLS) regression analyses to analyze the 1.1 million parliamentary speeches in the digitized archive of the UK Hansard. I discover patterns not only in the terms and language MPs used to debate core policies but also in how they interrelate political issues. I find that as social scientization intensified, MPs increasingly positioned schooling and education in relation to an ever-wider gamut of political concerns, independent of the actualities of economic, political, and social development. The development and elaboration, institutionalization, and diffusion of functionalist social theories as part of nineteenth-century social scientization radically redefined the political meaning and salience of schooling and education in Westminster and helps us to understand the historic expansion of the state idea.

The purpose-built state school

Histories and sociologies explaining the origins of state schooling predominantly focus on the factors related to capitalist industrial development that fomented new demands on the state to school. For example, one set of these historical explanations emphasizes the material determinants of state schooling systems (Anderson and Bowman Reference Arnold, Jean Bowman and Stone1976). According to these, intensification of capitalist industrialization in England heightened demand for semi-skilled labor (Sanderson Reference Sanderson1995). Parvenus, industrialists, and the growing middle class, in their turn, laid claim to education that had been traditionally closed off to all except the gentleman of the shire, including both primary and public school education (Allsobrook Reference Allsobrook1986; Colley Reference Colley1992). These explanations also emphasize that greater economic prosperity increased the state’s technical capacity to organize and systematize social welfare institutions, like public schooling (Dincecco Reference Dincecco2015). From this perspective, mass schooling was an indicator of a state’s effectiveness at addressing the new problems stemming from ongoing capitalist industrial development. While industrialization was a necessary and enabling condition for the state to build a system of national education, it does not directly answer the question as to why legislators themselves would formulate, debate, and come to pass education bills or conceptualize mass schooling as an effective policy tool. In contrast to this established literature, this present piece is designed to address precisely this question.

Another set of explanations focuses on interrelated social transformations. Populations in urban cores exploded due to higher birth rates as well as ongoing rural-urban and international migration (Pooley and D’Cruze Reference Pooley and D’Cruze1994; Williamson Reference Williamson1988). This created more anonymity and diversity in cultural and social-class backgrounds among those peopling cities (Vernon Reference Vernon2014). Industrial centers also became sites of increased crime, alcoholism, and homelessness (A. F. Weber Reference Weber1967). Particularly in Victorian England, these were real political problems confronting the state. Together, rates of poverty, drunkenness, and prostitution (among other nineteenth-century social ills) reached crisis levels in industrializing and urbanizing society, and these formed a constellation of social questions that mass schooling could address. According to this prior literature, mass schooling emerged as a solution that would generalize industriousness, cleanliness, national character, and morality, in addition to literacy and numeracy, among the lowly and working classes from Spitalfields to Leeds (McCann Reference McCann1977). Still, the presence of these problems does not fully account for why legislators themselves saw state schooling as a tenable, scaled-up policy that could effectively address crime and destitution in the industrial city.

A third set of explanations emphasizes the transformations to the polity itself. After the three Parliamentary Reform Acts of 1832, 1867, and 1884, suffrage rates increased from 2.5% to 35% of the adult population (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, John Gerring, Lindberg, Jan Teorell and Altman2022). Political elites were concerned that the newly enfranchised would not know how to participate in established political institutions and traditions (Adamson Reference Adamson1930). All the while, representation in Westminster became more representative of popular interests and less clientelistic and particularistic in its distribution programs (Stokes Reference Stokes and Goodin2007). The rise of working-class political movements such as Chartism meant greater claim-making on the state for great public provisions, such as education (Laqueur Reference Laqueur and Stone1976; Simon Reference Simon1974). As a solution to the problems of democratization, these explanations emphasize, state schooling provided political socialization as well as met the popular demand for collective self-determination. As this prior work shows, social and political movements engaged in articulate claim-making, and the rise of popular sovereignty had an unambiguous role in pressuring British political elites to expand access to education. Yet, the prior literature does not account for why elites themselves came to link state-organized national education with notions of political stability.

Social scientization & the expansive political purposes of schooling

My main argument is that the hereto described expanded political purposiveness of schooling to the nineteenth-century state is a cultural artifact of specific historical period. This period – spanning the latter half the nineteenth century – was when theories of rationalized societal progress were intensively elaborated, reified, institutionalized, and diffused throughout the Western system as part of the historic ascendance the burgeoning “social sciences” and “social-scientific” thinking. State schooling was the cornerstone of these newly elaborated and increasingly circulated functionalist theories of development, and the widening gamut of political purposes that historical actors began putting to education expressed state schooling’s growing centrality in broader cultural imaginaries. I foreground here that the elaboration and political enactment of such functionalist theories, which emphasized state schooling as an existentially requisite institution for the health and further development of society, were themselves an indicator and intensification of ongoing cultural rationalization, or what Carruthers and Espeland (Reference Carruthers and Espeland1991) describe as the application of rationalistic accounting principles in cultural, political, or normative domains. The emergence and institutionalization of the “social sciences” as well as their heightened salience in the politics of development in the nineteenth century – inclusively what I term social scientization – were expressions and mechanisms of cultural rationalization (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas, George Thomas, Ramirez and Boli1987). It is this context of ongoing and intensified rationalization, spurred on by social scientization, that was necessary for political elites to see state schooling as an “effective” and “efficient” means to optimize a growing number of political outcomes.

Social scientization was a sweeping transnational epistemic movement that had several defining characteristics. The first was the elaboration of functionalist social theory (Heilbron Reference Heilbron1995). This occurred across a litany of new and long-standing social categories, such as the individual, society, nation, and state. For example, nineteenth-century social scientists theorized the state as exogenous to society, responsible for melioristically steering its progressive development (Carroll Reference Carroll2006; Rueschemeyer and Skocpol Reference Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1996). Society itself was elaborated in naturalistic terms: an organic entity, a “population,” abiding by universalistic laws of advancement (Ellwood Reference Ellwood1909; Malthus Reference Malthus1890 [1798]). And, in this nineteenth-century theory, the individual took on a whole host of expanded and increasingly essentialist identities: self, gender, race, class, and agency (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2009; Meyer and Jepperson Reference Meyer and Jepperson2000; Wahrman Reference Wahrman2006).

Perhaps the most important aspect of this theoretical elaboration was the functionally integrative role that education played in social theories of progress (Boli et al. Reference Boli, Ramirez and Meyer1985; Meyer Reference Meyer, Cuban and Shipps2000). State schooling was the means by which individuals could be tamed and cultivated; by which society could economically, socially, and politically develop; by which the state itself could survive in perpetuity by planning and obviating revolution and competition (Comte Reference Comte1974 [1822]). Whereas in the ancien regime education was a religious, moral, and above all else, a private endeavor (Cressy Reference Cressy1976), in nineteenth-century social theories, it centrally functioned as the rationalized means of societal progress, touching on nearly every aspect of personal, social, political, and economic life. So much was quite explicit in the works of Condorcet (Reference Condorcet and Michael Baker1976 [1791]) and Comte (Reference Comte1968 [1855]) but also in the works of prominent British social-scientific thinkers such as Robert Owen (Reference Owen and Silver1969: 69–148), Jeremy Bentham (Bentham Reference Bentham, Schofield and Harris1988), Herbert Spencer (Reference Spencer1859), Francis Galton (Reference Galton1873), and Karl Pearson (Reference Pearson1905: 94). For example, in contrast to earlier arguments about state-sponsored education made by Adam Smith (Reference Smith and Heilbroner1986: 307) and Thomas Malthus (Reference Malthus1890: 497) emphasizing sparing state intervention for the poor to maintain moral and social order, nineteenth-century British theorists saw secular state schooling as the chief means of greater happiness and progress (Owen Reference Owen and Silver1969: 99); especially important in understanding self and society (Spencer Reference Spencer1859); and particularly critical in struggles of national survival on the world stage (Pearson Reference Pearson1905: 21; 94). Social scientization generated much theoretical discourse, most of which directly elaborated the role of schooling in the development of both the state and society.

These theories of rationalized progress were backed by new kinds of social data and statistical techniques (Hacking Reference Hacking2006). States all across the Western system began conducting censuses, establishing official statistical agencies, and annually producing statistical portraits of their populations (Emigh et al. Reference Emigh, Riley and Ahmed2016). Numerous statistical societies were founded throughout the system, including in Manchester and London, and each were dedicated to social and education reform (Butterfield Reference Butterfield1974). Moreover, statistical (and social-scientific) journals exploded during the period (Cantor and Shuttleworth Reference Cantor and Shuttleworth2004). Collectively, these concerted efforts at social quantification made abstract theoretical constructs and normative political concepts observable, measurable, and manipulable empirical realities. The promise of objectivity, accuracy, and precision of statistics also elevated their epistemic authority, making quantification and its embedded theoretical content both more credible and normatively hegemonic. Finally, statistics facilitated the diffusion of this cultural content, making theorized relationships, say, between crime and literacy, into highly portable stylized social facts that could be compared across disparate settings.

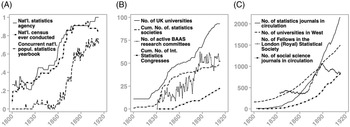

As evident in Figure 1, which visualizes trends in each of these indicators of social scientization, this process of theoretical elaboration and social quantification was not just the result of independent, piecemeal national efforts but was, instead, a demonstrably transnational epistemic movement. This “social-scientific” thinking became institutionalized in civil society associations and organizations (Goldman Reference Goldman1998; Willcox Reference Willcox1934), in the modern research university (Wittrock Reference Wittrock, Rothblatt and Wittrock1993), as well as in scholarly publishing. What is critical here is that the movement was self-consciously internationalist, with explicit aims at creating a totalized, integrated understanding of human society that spanned nations and states. The internationalism inhered not only in the movements’ contemporaneity but also in its interdependence, as people and ideas were highly mobile (Heilbron et al. Reference Heilbron, Guilhot and Jeanpierre2008). The international congresses and meetings, too, were expressly transnational, framing the social-scientific study and reform of nineteenth-century society part of a worldwide effort (Leonards and Randeraad Reference Leonards and Randeraad2010).

Figure 1. Trends in indicators of social scientization showing the rise of an international epistemic movement, across the Western system, 1800–1914.

Source: Multiple; see Table 2.

Nineteenth-century social scientization was a historic cultural process that elaborated functionalist social theory and, in the process, fundamentally redefined education into a state instrument of expansive political potential. Its statistical reification, its institutionalization and professionalization, as well as its integration into the state apparatus amplified the political influence of functionalist social theory, expertise, and professional “scientists” of society, particularly among elite state actors (MacLeod Reference MacLeod1988). As a result, the political meaning and resonance of education and schooling transformed. Once a parochial matter siloed in a narrow discourse of social order, by the century’s end, schooling became a veritable trope in functionalist social theory, in the political discourse, as well as a preeminently central social welfare institution of the polity, luxuriantly salient to an ever-wider gamut of statesmen’s political concerns and visions of unbound civilizational progress and collective deliverance.

Data & methodsFootnote 3

Data: UK legislative proceedings

To investigate the expansive political purposes and purposiveness of schooling for the British state during the long nineteenth century, I collected the population of legislative proceedings from 1804 to 1913 (n ≈ 1.1 million speeches). The proceedings contain first and second readings of bills. They include debate – from extended opening statements to ripostes quickly exchanged – about both successful and failed legislation. And they include proceedings from committees. The longitudinal character of these text data is ideal to study change in political reasoning over time, especially the subtler shifts best observable in the aggregate over the long run. And their uniquely comprehensive character, expressing generations of politicians’ views on all matter of political issues of their day, is also ideal. Instead of narrowly representing a given PM and his government’s policy priorities, exhaustive representation of all statesmen enables me to characterize the legislature as a whole.

Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA)

I take a computational grounded theory approach to discover latent and emergent patterns in the official political discourse (Nelson Reference Nelson2017). Specifically, I apply the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm, which is a generative probabilistic model that discovers underlying structures in data, such as texts (DiMaggio et al. Reference DiMaggio, Nag and Blei2013). The data inputs for the LDA algorithm are the texts of the parliamentary speeches, transformed into “bags of words,” which means each speech is represented as a list of stemmed words absent of their order, punctuation, conjugation, and capitalization. The algorithm computes how frequently each stem co-occurs with every other stem in each speech. It then finds clusters of words – “topics” – that tend to frequently occur together in speeches.Footnote 4 Finally, each speech in the corpus is transformed into the weighted mixture of these topics that best predict the speech. There are two outputs of the LDA algorithm. The first output is the most indicative terms of each topic. In a process akin to qualitative coding of emergent themes, I interpreted these terms to label the topics. The second output is the array of topic weights (“thetas” or “loadings”) that characterize the content of each speech. This array of topic weights sums up to 1 for each observed speech in the population.

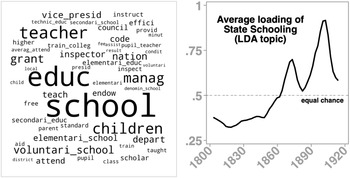

As the focal topic of this piece, in Figure 2, I show the word cloud of the LDA topic I identified as “state schooling” as well as a trendline of its prevalence in the corpus. It includes terms describing all manner of aspects of the schooling system: both primary and secondary schooling; school type; school management and finances; teachers and teacher training; parents and students; as well as standards, efficiency, and inspection. The trends in the average prevalence of this topic suggest its gradual institutionalization as political topic and object in the discourse.Footnote 5

Figure 2. Most indicative terms of the state schooling (LDA) Topic and trends in its prevalence in the corpus, 1803–1913.

Semantic networks

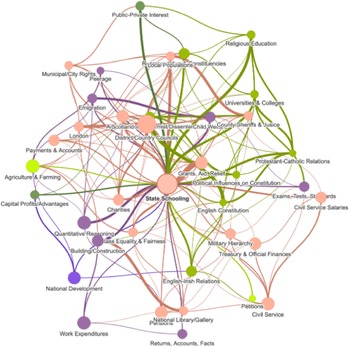

I use semantic network analysis of these topics to investigate the latent structure and changing meaning in the political discourse (Sowa Reference Sowa, Shapiro, Eckroth and Vallasi1987). Semantic networks are relational representations of words or topics within whole corpora of texts. The characteristics of the web (network) of interrelations (links) among words or topics (nodes) reveal contingent and situated meaning in the discourse (“semantics”). For example, the meaning of a given topic, such as education, may be interpreted through its relationship to other topics, such as social order and religious morality. To represent parliamentary speeches as semantic networks, I define each node in the network as a political topic. I define their interrelations (edges) by how frequently MPs tended to jointly debate these topics in their speeches. I draw an edge between one and another political topic only when MPs substantially debated both topics (i.e., the loading of each is ≥ 10% of the speech)Footnote 6 in a statistically significant (i.e., ≥ 2 SDs above the mean) number of speeches in a year. For the graphical visualizations of the networks below, I weight the nodes’ sizes by the normalized topic loadings (bigger nodes mean speeches were on average more directly about the topic); I weight the links between nodes by the normalized number of shared speeches (thicker links mean more speeches discussed both topics); and I group nodes and links (indicated by color) by how similarly MPs tended to treat the topics in their speeches (topics of the same shade form a constellation or “neighborhood” of interrelated issues).Footnote 7

Analyses

In my analyses, the unit of observation is always the parliamentary speech; when aggregated, these speeches represent the official political discourse. The unit of analysis is the semantic network representation of these aggregated speeches. In the network and regression analyses, I vary the level of aggregation of speeches.

First, I represent the political discourse in three periods of distinctive parliamentary debate.Footnote 8 For each period, I construct a semantic network that describes all speeches in that period (n = 3 semantic networks). For clarity, I visualize only the state schooling topic and its relations, though each network is much more complex. These period-specific, topic-centric semantic networks enable me to visually analyze changes in how MPs integrated schooling into their debates about governance. Individually, they are cross-sectional snapshots. Together, the three periods summarily describe the whole political discourse. Based on the emergent patterns of meaning in these period-specific, topic-centric semantic networks, I select and interpret exemplary speeches (determined by their topic loadings). This combination of network and discourse analysis uniquely affords the opportunity to observe and interpret cultural change in political discourse using big archival data.

Second, for each year, I construct a semantic network representing its parliamentary discourse (n = 106 annual networks characterizing speeches in each year). Individually, the yearly semantic networks are also cross-sectional snapshots of the discourse, but they sum up across time to represent the whole discourse. Instead of visually analyzing each network graph, I compute network metrics summarizing the discourse with respect to the schooling topic, each year. I use statistical models to explain variation in the discourse about schooling (see below).

Outcome: The changing purposiveness of schooling

I seek to understand whether, to what degree, and why schooling became central in the official discourse of the state. I measure this as the degree centrality of the state schooling topic in each yearly semantic network. The degree centrality of the state schooling topic describes the number of other political issues MPs debated in conjunction with state schooling in a given year. A higher degree centrality means that MPs directly interrelated schooling to a larger number of other political concerns in their speeches. The measure is relative; it is the proportion of topics related to schooling out of all topics discussed. In this way, degree centrality is a different measure than the average emphasis MPs placed on state schooling in their speeches. It also differs from the number of speeches about schooling that MPs delivered. Whereas these latter metrics capture the amount of bench time MPs attended to the topic, degree centrality gauges how central state schooling figured in the political discourse, relative to other topics. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Data sources & descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables, 1804–1913 a

a The archive is missing data for 3 years, hence 106 and not 109 years.

Independent variables

Social scientization

Based on the arguments in Section 3 above and drawing on past work (D. S. Smith Reference Smith2022), I construct a measure to describe social scientization across the nineeenth-century Western system based on the indicators visualized in Figure 1 above and Table 2 below. I selected indicators that proxy the elaboration of social theory and quantified empirical studies of the social. Such indicators include the number of social science and statistics journals, where methods and theories about quantified society were developed and circulated broadly. I also selected indicators that proxied the movement’s successful scientization of state structures; these include state statistics agencies, state censuses, and state population statistics yearbooks. Such state structures, measured throughout the Western system, proxy an emerging rationalized social state model. Finally, I selected indicators that proxied the movement’s successful institutionalization as “social science” in British and international civil society; these include the emergence of societies, activist congresses, and socially oriented universities in the UK and across the West. Importantly, social scientization was not only a top-down process, nor was it a bloodless intellectual hobby; instead, as these civil society indicators proxy, it was activistic and melioristic (Leonards and Randeraad Reference Leonards and Randeraad2010). Together, social scientization thusly measured indicates a bottom-up and top-down process; it was a translocal, polyvalent characteristic of the nineteenth-century institutional order that showed sweeping intensification as the century progressed.

Table 2. Data sources & descriptive statistics for indicators of social scientization, 1804–1913 a

Notes:

a See Smith (Reference Smith2022) for associated variable definitions and arguments. The measure of social scientization in the current study includes additional (4, 5, 8, 9) and improved (7) data.

b To collect 8 and 9, I used OCLC WorldCat, “the world’s largest network of library content” containing collections of more than 10,000 libraries worldwide. I identified and summed up all periodicals/journals classified under the Library of Congress subject headlines “social sciences” or “statistics” in circulation in any year during the nineteenth century. OLCL WorldCat returned a total of 8,928 catalogue records. I downloaded each in collections of 100 (i.e., 89 RIS files) and then programmatically parsed the files to create a data frame containing relevant identifying information (e.g., journal title, language, years in print, publication place). After removing duplicates and catalogue records with unknown start or end years (e.g., “1840–1900s” or “1800s–1907”), the final universe of nineteenth-century social science and statistics periodicals/journals in circulation at any time between 1800 and 1914 was 5,196.

The indicators have a very high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.99) and present evidence of a unidimensional view (eigenvalues of factors 1 and 2 are 11.4 and 0.9, respectively; 90% of combined standardized variance explained by factor 1). Based on this evidence, I computed and standardized a time-varying factor score describing the degree of social scientization of the Western institutional order each year of the nineteenth century.

Development

As the prior literature above suggests, the state’s focus on schooling plausibly increased as a result of processes related to development. Due to issues of multicollinearity, direct measures of industrialization, urbanization, and democratization could not be leveraged, as they led to unstable estimates. Therefore, I proxy economic development as industrialization, continuously measured as the ratio (%) of agricultural output to industrial output. I proxy political development as the decline in clientelism, continuously measured as the standardized score on the public versus particularistic goods index (higher values correspond to greater programmatic versus clientelistic goods distributions). And I proxy social development as life expectancy, continuously measured as the average lifespan of the population. Additionally, since I examine the political discourse each year over the century, changes in these features of the UK state and society are likely to have been politicized in debate about the polity’s order of business (e.g., alarmist characterizations of “decline” associated with decreases in industrial output). Therefore, I include the growth (% change) over the last year of each of these variables.Footnote 9

Conflict

Prior work also emphasizes the role of interstate conflict in driving state expansion (Tilly Reference Tilly1975). I measure this directly using binary variables indicating whether the UK was engaged in international armed conflict and whether armed conflict occurred domestically. I also measure the degree of military conflict in the Western system continuously as the ratio (%) of states engaged in international armed conflict.

GLS regression

I relate variation in the centrality of state schooling in the political discourse over the course of the nineteenth century to the historical processes defined above, each lagged by one or two years,Footnote 10 by fitting a taxonomy of generalized least square (GLS) regression models with prime minister fixed effects. Fixed effects account for year-invariant characteristics of the ruling party, such as its manifesto, which condition the proceedings of a given legislature.

Findings

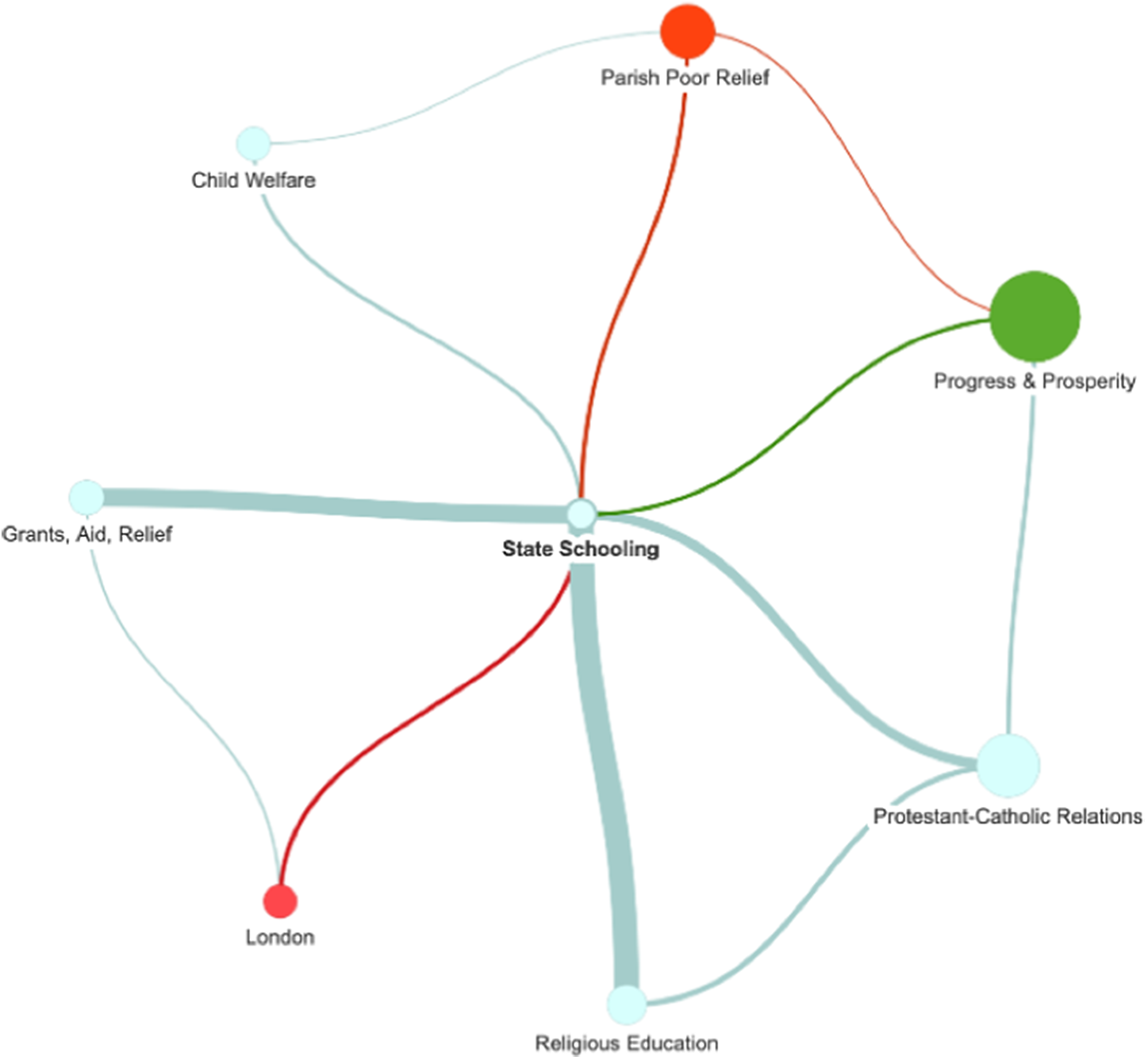

Schooling for religious morality (1804–1850)

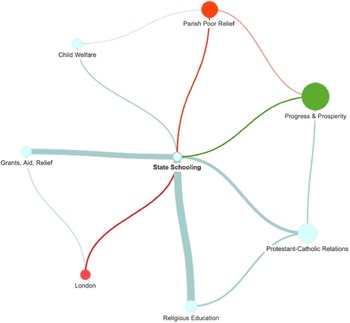

I visualize in Figure 3 state schooling’s weighted topic-centric network for the earliest period of distinctive debate. The network is sparse, despite spanning the longest period. There are just seven other political topics that MPs tended to debate in conjunction with schooling: grants, aid, and relief; child welfare; religious education; Protestant-Catholic relations; parish poor relief; London; and progress and prosperity. Among those seven, the first four listed constitute the core problematic within which MPs tended to situate schooling in their debates during this period, indicated by their shared shade. This constellation can be understood, in relation to schooling, as a Smithian concern for public support for schooling among the poor, on the one hand, and, on the other, political concern about religion. Indeed, schooling was most often debated in the context of religious education (i.e., this edge is thickest). Schooling also serves as a redundant bridge between two other constellations of political concerns: seen here, MPs debated schooling in terms of poor relief and London as well as prosperity and progress; these other issues are themselves interconnected to other constituent issues of the schooling problematic.

Figure 3. Topic-centric semantic network of state schooling, 1804–1850.

What does this semantic network, a cross-section of the parliamentary discourse of the first half of the nineteenth century, tell us about the political meaning and salience of schooling at that time? I interpret the comparatively small vertex size of state schooling (the smallest) to corroborate the trend visualized in Figure 2: MPs tended not to address schooling in their speeches during this period. The network’s sparsity (few vertices) and redundancy (schooling’s direct connections are interconnected themselves) indicate that state schooling was a relatively peripheral, siloed concern for MPs as they debated the business of government. A minor topic rhetorically situated among just a few others, when MPs did discuss schooling, it was most often isolated and in relation with funding schemes (i.e., government grants and aid) and, most importantly, religious education.

The tightly demarcated character of schooling’s relevance to the polity that surfaces in this semantic network – in contrast to the sweeping vision articulated by Mr. Roebuck in 1833 at the start of this piece – reflects the state’s earlier laissez-faire approach to social welfare and the social question. While Owenite and Benthamite functionalist social theories were long since published and had already developed an animated following inside and outside of Westminster by this period, as a whole, the discourse still reflected a rather “traditional” and narrow conception of the state’s role in education that emphasized order among the lowly classes. In this period, seen here in the aggregated expressions of nearly 6,000 MPs, it was conceivable for the state to get into the business of schooling, but mostly on the side through grants-in-aid for religious instruction.

To get a better sense of how MPs enacted these conceptions of the state’s role in education, I identified the speechesFootnote 11 with the highest loadings on the schooling and religious education topics. I excerpt one of these speeches, which Lord John Russell gave on National Education in the House of Commons in 1850.Footnote 12 In this speech, he makes a case against an Education Bill that would erect a state system of national primary education.

It remains a very great question whether we should declare that there should be schools established upon the principles laid down in an Act of Parliament, in which schools secular education only should be given.… I cannot but think that nothing but the most absolute necessity should oblige Parliament to… establish… a system of education for the children of the poor of this country from which religion should be entirely excluded. To establish such a principle without an absolute necessity would be a grievous falling off in our own duty, both to our religion and to our fellow countrymen.… [W]e must consider that we are dealing with a country in which many schools have been already established – schools which, however they may differ generally, all agree in one great principle, and that is, the imparting of religious instruction to the children… Through them all, many as are their differences, runs this one great principle, that, according to the opinions and consciences of those who superintend those schools, and whose money, labor, and time are devoted to them, religion is the grand and uniform object (Lord John Russel, HC Deb 17 April 1850 vol 110 cc472–74).

The question on the table before the Commons was whether, by an Act of Parliament, national education should be further promoted through state-sponsored schools. The issue at hand was the conscience clause. Were the state to begin providing national education, instruction would need either to be nonsectarian or wholly secular, and neither option was amenable to the diverse religious interests Russell itemizes above. This was an exceedingly contentious issue of the period, leading to many failed national education bills, since voluntary schooling initiatives of the Church of England, the Catholic Church, and Dissenting sects exclusively provided access to education for the poor up until 1870 (Adamson Reference Adamson1930).

From Russell’s view, it was more unethical for the state to provide secular education than to provide none at all. His characterization that a government-provided, nonreligious education was a dereliction of duty to “our religion” and “our fellow countrymen” especially expresses this prevailing and narrow framing of education of the period. Russell’s use of the inclusive first-person plural possessive here (“our”) at once rallies a sense of collective identity and endeavor among the men in the house as well as a sense of ecumenical solidarity with and duty to the Christian nation outside Westminster who they represented. Indeed, by providing a sweeping account of the diverse and disparate religious causes across the country and then unifying them under that “grand and uniform object,” Russell makes the case that religion, above all else, was the Rousseauistic general will of the nationFootnote 13 , so extraordinarily united here in ceaseless and selfless devotion to this greater cause through “money, labor, and time.” (Never mind the centuries-long history of bloody religious conflict.) Russell, in other words, valorizes a primordial, pre-political nation’s collective desire for Christian truths and ethics, which the state could not in good conscience obstruct. Secular schooling was incommensurable with the presiding views of what education was for and with what was appropriate for the state to do. And, against these views, an Act of Parliament legislating state schools that were free of religion would be all but malfeasant.

To be sure, there were alternative views of the political salience of schooling in this period; Roebuck’s expresses one of them. Yet, it is Russell’s that particularly represents the narrow meaning of education that I show as the organizing logic of the parliamentary discourse about state schooling in the aggregate semantic network of Figure 3. And it is the view that exemplifies the UK government’s hands-off approach to education policy during the first half of the nineteenth century: subsidizing education through grants-in-aid to the religious schools of voluntary associations.

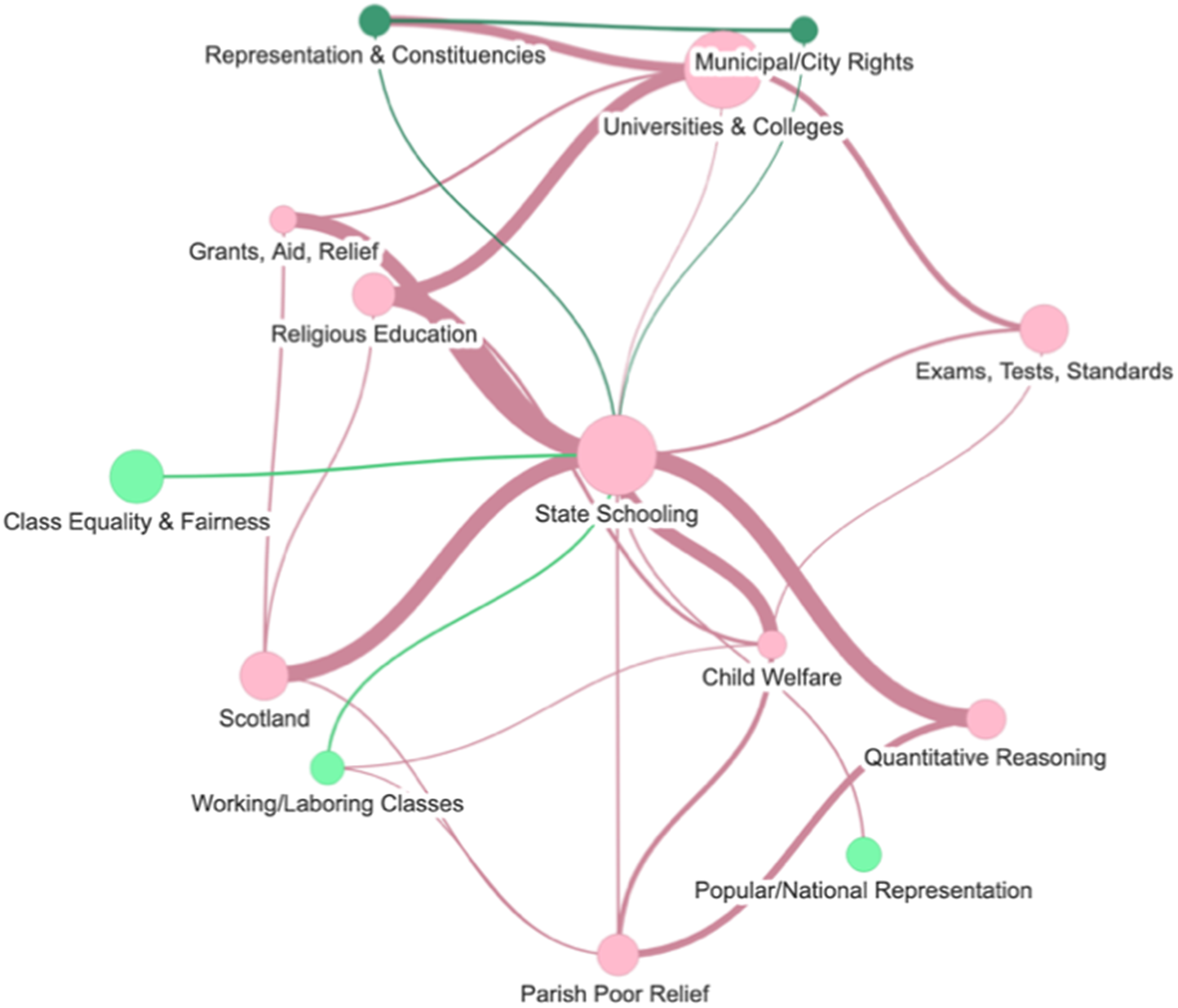

Schooling for social mobility (1851–1885)

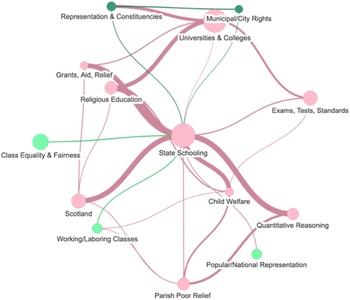

I visualize in Figure 4 the topic-centric semantic network of state schooling. In this period, state schooling remains strongly tied to issues related to religious education, grants, aid, and relief, as well as child welfare, reflecting MPs’ enduring political preoccupation with state-aided provision of religious instruction. Yet, the state schooling node is considerably larger and the network considerably denser compared to the period corresponding to the first half the nineteenth century, with MPs having discussed schooling more prominently and interrelated it with nearly double the number of political issues.

Figure 4. Topic-centric semantic network of state schooling, 1851–1885.

I interpret two discernible patterns in this expanded salience of schooling. The first is its heightened relationship to social welfare domains adjacent to child welfare, seen here as the frequent and substantive connections that MPs made in their debates between schooling and class equality and fairness as well as issues related to the working classes. Tellingly, state schooling bridges these latter issues in the semantic network (i.e., they are not themselves connected). On one hand, this is suggestive of reverberations in the official political discourse of the working-class social movements that agitated for universal political representation and universal access to education during the period (Simon Reference Simon1974). On the other hand, this semantic linkage is indicative of an evolving cultural framing of state schooling, jointly expressed by these social movements and instantiated here in MPs’ official debates about state policy: schooling is an integrative insitution politically linking (bridging) a growing array of political and societal aims. To be sure, schooling remains inextricable from more narrow, religious concerns. Yet, secular, Owenist notions of harmony and happiness (e.g., equality and fairness) as well concurrent social-scientific constructs (e.g., socioeconomic class) now impinge on schooling as statesmen debated it.

The second, complementing pattern I interpret in the expanded political salience of schooling is its new integration into system thinking and administration building (Roberts Reference Roberts1959; Sayer Reference Sayer1992). If MPs elaborated education, linking schooling to an enlarged constellation of political ends involving social welfare, then they also expanded it, linking schooling in a multilevel system that spanned, at the one end, child care, and at the other, university and college education. They also applied quantitative reasoning to debate schooling and related it to a machinery of standardization and quality assurance through tests and exams in order to routinely evaluate and monitor the returns on state investments in education (Midgley Reference Midgley2016; Rapple Reference Rapple1992). These findings suggest that state schooling in this period emerged as both a means to and object of the state’s efforts at rationalization: an increasingly central system for state-guided societal progress and development (i.e., greater equality, fairness, and welfare) and an object of the state’s intensified efforts to make the selfsame system ever more efficient, quantifiable, and manageable (Author, 2022c).

To concretize these high-level observations of the aggregate discourse, I reproduce an excerpt from an exemplary speech given in 1869 by Horatio Nelson, 3rd Earl Nelson:Footnote 14

Earl Nelson said, he thought the measure one likely to give an improved education to the children of the middle classes, and, at the same time, to admit a portion of the children of the working class to its benefits.… What was wanted was the lowest step in the ladder, by which boys in the working classes might be able to rise… a boy of the working class might be enabled to rise from one step to another, passing from school to school, till he might get to the University…. He considered, therefore, that if the grammar schools were made, as it were, a step in the ladder, so as to give the lower classes the means of raising themselves in the social scale, the country would only be paying back to those classes what was due to them…. Primary education alone gave boys of the working classes no opportunity of rising to a higher position; and his own opinion was that, by giving even small scholarships to the sons of the working classes, a great stimulus would be given to education. He was convinced that if such a plan were carefully carried out a good and sound system of education would be established… (Earl Nelson, HL Deb 28 June 1869 vol 197 cc613–15).

The speech from which this quotation was excerpted ranked highest on the state schooling and class, equality, and fairness topics. In it, Lord Nelson weighs in during the second reading of a bill that later became the Endowed Schools Act of 1869, which established a centralized commission to organize and manage a countrywide system of secondary education for the middle classes that deemphasized classics and added geography, history, and science to the curriculum. It also established merit-based scholarships for the students of the lowly classes who excelled in elementary schools.

Lord Nelson speaks to this latter policy design feature in the excerpt. He describes secondary-school scholarships for working-class boys as an incentive for further education (“stimulus to education”) and thrice likens them to a “step” in “the ladder,” a means for social mobility whereby the working class can “rais[e] themselves in the social scale.” Still, for Lord Nelson, access to secondary schooling was more than a matter of individual inducement and advancement. Expanded access to secondary schooling through state-managed school endowments was also a matter of redistributive justice, a means for the state to “[pay] back to those classes what was due to them.” Lord Nelson’s vision was of a holistic and virtuous (“sound”) education system of disrupted social-class reproduction, so that the uneducated butcher’s son could become a university graduate “passing from school to school, till he might get to the University.” In this excerpt, reflective of the larger aggregate patterns I visualize in Figure 4, we hear the intonations of an altogether different conception of society and the state than the one given by Russell in the previous period. In contrast to a closed social system wherein inherited privilege patronized and relieved the poor through state-aided religious instruction, in Lord Nelson’s utilitarian vision is a relatively open, concatenating system of social mobility and collective empowerment. Conceptually underwriting it is an expanded functionalist theory of education and educability. Education figured into the social system as the means of social stratification and, when made into a systematized intervention as state schooling, it was to be the means for greater social justice.

The emergence in this period’s official political discourse of a state system of schooling is again reflective of historic change in the UK government’s actual approach to education policy (see Figure A1 in Appendix, Supplementary material). As noted, with the Act of 1869, a nascent secondary-school system was instituted, serving as the middle rung in a larger interlinked educational ladder that started with primary school and ended at the university. With Forster’s Education Act of 1870, the state instituted local school boards and established secular primary schools to promote universal access to education, keeping the “missions” of voluntary religious schools intact. And, with the Mundella’s 1880 Elementary Education Act, the state made schooling compulsory for all children aged 5–10 (Birchenough Reference Birchenough1914). Yet, at the same time, the official political discourse also reflects the constitutive meta-discourses undergoing continual change during this period and redefining all the while the theorized character and effects of education and so its political meaning in Westminster. The dynamism of this cultural change and persistence is especially evident in the narrow religious legacy of schooling (the organizing the political discourse in Figure 3) alongside the emergence of an elaborated state schooling system with expansive potentiality as a great equalizer, captured by Lord Nelson’s words.

Schooling for national development (1886–1913)

I turn to the last period of distinctive parliamentary debate. In Figure 5, I visualize its semantic network. By far the densest of the three periods, MPs substantively and frequently interrelated state schooling with 35 other political issues, a striking indication of its heightened salience to the business of government. The note of state schooling remains the largest in this semantic network as in the previous period’s, indicating that MPs tended to discuss schooling most frequently and to interlink it in their speeches as the primary focus among the other ancillary political concerns. The new constellation of issues in which MPs embedded schooling (the same shaded nodes and links) sprawls: military structure, building and public works (the National Gallery and Library), civil service, government finances, district and county governance, class equality and fairness, and justice. Notably, MPs no longer debated religious education as part of the state schooling problematic, though it remained significantly tied (Figure 5, the node is northeast on the perimeter). MPs also discussed child welfare as part of its own constellation of concerns, linking it to issues related to emigration and standards, among others (purple node, northeast of the center).

Figure 5. Topic-centric semantic network of state schooling, 1886–1913.

I draw two inferences from this semantic network. First, whereas in the previous period, MPs debated schooling in terms of an emergent system thinking (Figure 4), in this period, schooling became thoroughly enmeshed in an expansive state bureaucratic apparatus, reflecting its institutionalization as an instrument and system of and within the state itself. Second, to the contemporary reader contemplating the political salience of schooling and its various purposes in social and economic life – schooling for greater justice, for economic development, for both private gain and public good – the visual near-incomprehensibility of schooling’s semantic network in the political discourse might make sense and seem natural. A core feature of contemporary culture is how central schooling is in society and how much of a defining characteristic it is of life in the modern nation-state (D. Baker Reference Baker2014). But it is the very naturalness of state schooling’s sprawling salience and potentiality at the dusk of the long nineteenth century that denaturalizes schooling’s angularly religious function in the political discourse at its dawn. It is when we compare Figure 3 with Figure 5 that we can apprehend the immense cultural change that transpired during the course of the nineteenth century and fully understand the foreignness and strangeness of that time, indeed, when a prime minister could successfully make the case that a schooling state was a villainous state.

I reproduce below an excerpt of speech Mr. Channing gave in committee in the House of Commons in 1902 demonstrating an example of how schooling centrally figured into the business of the state in this period (i.e., national development).Footnote 15 Mr. Channing was speaking about the bill that would become the 1902 Education (Belfour) Act, a Conservative initiative that eliminated the local school boards of state primary schools, consolidated the governance of voluntary religious and state primary and secondary schools into local education authorities, and afforded greater financial support to religious voluntary schools (which had been teaching a third of British pupils) and greater influence to Anglican and Catholic interests over instruction.

Mr. Channing thought… that technical and secondary education were the most urgent necessities of the times.… [I]nstead of going to the root of the question, which was our inability to compete with other nations of the world owing to our want of secondary education… this Bill was merely a Bill which would do little for secondary education, and … and would sacrifice the future of education and the equipment of the nation to the interests of the least efficient schools. We had to face commercial competition and educational competition. We talked of trade, and of tying down the colonies to buy their goods of us, but Australia and Canada bought goods from America and Germany, because America and Germany had had the common sense to make their leaders of industry more ingenious and skilful, and by so doing they were enabled to supply the market at a cheaper rate (Mr Channing, HC Deb 02 June 1902 vol 108 cc1154–56)

Channing argued that the bill then under consideration was organized around the wrong principles altogether. Instead of expanding financial support to inefficient, religious primary schools – one of the bill’s chief elements – he instead argued the state should expand instruction in technical and secondary education, evoking Thomas Huxley’s (Reference Malthus1893), Herbert Spencer’s (Reference Spencer1859), and Karl Pearson’s (1905: 34–35) own emphasis on science and technical education. While Channing’s was not the majority position in this committee, it nonetheless reveals the new ways statesmen instrumentalized schooling in order for the British state “to compete with other nations of the world.” The crisis he sees here is Britain’s comparative “commercial” and “educational” disadvantage due to its persistent underinvestment in technical and secondary education. With urgency, he argues that the statesmen in committee should “concentrat[e] all our thought and energy and our present limited resources” to redress the national deficit that had sweeping consequences for the empire’s prosperity.

The expansive purposiveness of state schooling

I now turn to consider the political discourse holistically and longitudinally with 106 yearly semantic networks. I depict the trends in the summary measure of state schooling’s political purposiveness in the political discourse across the nineteenth century in Figure 6. In this figure, each hollow circle corresponds to the observed degree centrality of state schooling of the semantic network in a given year, standardized to enable comparison across the years’ waxing and waning semantic network sizes (i.e., the universe of other debated topics expands and retracts over time). I overlaid linear and local polynomial fits and their respective 95%-confidence intervals to throw the direction and magnitude of the historical process into relief.

Figure 6. Trend in standardized degree centrality of state schooling showing its expanding purposiveness in 106 annual semantic networks of the parliamentary discourse, 1804–1913.

Figure 6 shows the degree centrality of state schooling significantly increased over the century (r = .94, p < .0001): at the start, state schooling was below the century average by more than a standard deviation; at its end, state schooling was nearly two standard deviations above average, a three-fold increase. As a measure of the number of political topics that MPs related schooling and education to, the progressive growth in state schooling’s degree centrality visualized here indicates how it became ensconced in the UK’s legislative proceedings, deeply interconnected among all the other political issues constituting the parliamentary discourse as a whole. Over time, MPs conceived and articulated schooling as relevant and salient to an ever-widening gamut of political issues. What is on view in Figure 6, then, is a process of dramatic political change, whereby, early on, schooling and education were only peripheral topics tangentially related but became later on integral to the management of the polity.

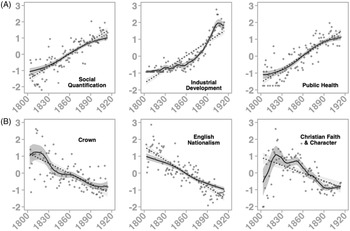

To further characterize the contingency of this political change, I visualize trends in the degree centralities of six contrastive political topics in Figure 7.Footnote 16 In Panel A, I include rationalized domains of intensified state organization of a family semblance with the state’s newly heightened role in and via schooling. In Panel B, I include “traditional” sources of political authority.

Figure 7. Trends in standardized degree centrality showing the political ascendance of topics related to rationalized progress (Panel A) and decline of topics related to traditional authority (Panel B) in 106 annual semantic networks of the parliamentary discourse, 1804–1913.

The health and wellbeing of the population become key organizing principles of the political discourse and the state’s suite of social welfare interventions (Abbott and DeViney Reference Abbott and DeViney1992), just as social quantification became a frame of political debate and tool of governance (Espeland and Vannebo Reference Espeland and Irene Vannebo2007). Indeed, the heighted centrality of topics related to theories of rationalized societal progress (economic prosperity and public health) as well as the increased reliance on the promise of objectivity and empiricism in social numbers and quantitative reasoning (Porter Reference Porter1995) suggest that functionalist thinking entered into and reconstituted political debate about the state’s role in addressing the social question and the good society (Figure 7, Panel A). This change is especially evident when compared against that visualized in the bottom panel. Earlier, more “traditional” bases of political authority had increasingly less purchase in political debate as the century progressed. Charismatic Burkean constitutionalism – the exceptional, uncontracted, inherited, time immemorial coherence and integrity of English national society – declined as a political logic organizing the parliamentary discourse. This suggests, as negative evidence, of a newer frame wherein Old England (the crown, a hereditary constitution, and Christian character) gave way to the incommensurate paradigm of the new nineteenth-century rationalist state. This, in turn, suggests a change in the larger cultural context framing political discourse and the lawmaking process: a shift whereby rationalized models of state-directed societal progress and welfare became politically ascendant and enacted, supplanting the authority of old-regime style politics.

To what extent did social scientization, as a transnational epistemic movement and a force of cultural construction during the nineteenth century, play a role in redefining the meaning and salience of education and schooling to the state? To address this final question, I turn to systematically explaining the change in schooling’s centrality. I report in Table 3 the results of fitting a taxonomy of fixed effects regression models that iteratively test the relationship between social scientization and the increased political salience of schooling, independent of factors related to historical conflict and development. These models are descriptive, offered here as aids to interpret the arguments hereto advanced.

Table 3. GLS results explaining the discursive centrality (Degree centrality) of state schooling in 106 annual semantic networks representing the UK parliamentary discourse, 1804–1913

Notes: Prime Minister (PM) adjusted robust standard errors are in parentheses. Variable definitions can be found in the Data & methods section.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.

I find plausible evidence that the changing shape and content of the political discourse was partially an outcome of broad processes of social scientization occurring throughout the Western interstate system. Social scientization drove the expanded salience of schooling as MPs increasingly rhetorically linked it to a growing number of other topics in the political discourse, independent of factors related to domestic and international conflict (Model 2), industrialization (Model 3), urbanization (Model 4), democratization (Model 5) as well as the time-invariant idiosyncrasies of the incumbent prime minister and his legislative agenda. All models provide evidence of the direct, independent, and large effect that social scientization, as a transnational epistemic movement, had in fundamentally reconstituting the political discourse. I do not find strong evidence supporting functionalist explanations emphasizing the direct role that problems associated with development had in promoting the broad-based political salience of schooling as an instrument of state intervention and governance.

It is worth dwelling on the unexpected null results in Table 3. Standard accounts of the rise of state schooling place great emphasis on the real dilemmas of order posed to the state by the dramatic economic, social, and political development of the nineteenth century. In these accounts, the salience and utility of schooling as a new political instrument and solution was the natural outcome of an industrializing economy and pluralizing society in need of both skills and a common basis of social and cultural intelligibility within the modern polity. Other accounts place more emphasis on the rise of organized initiatives to produce trustable social knowledge and marshal it to inform a whole range of state policies and actions aimed at addressing these new threats of social disorder. Capitalist industrial development caused the problems that state schooling solved and social science discovered.

The null results in Table 3 may complicate these narratives. Based on a strong reading of both accounts, the direct relationship between social scientization and the expanded political salience of state schooling as a tool to solve the whole host of political problems that arose in industrial urban society should cease when the presumptive determinants of the rise of state schooling and social scientization are accounted for. However, the independent influence of social scientization on the political salience of schooling in the parliamentary discourse was prodigious. The significant, large coefficients on the social scientization term, therefore, suggest the powerfully constitutive, cultural role of social scientization in generating functionalist narratives of the modern state that expounded on the centrality of schooling for a whole matter of political goals. Indeed, in the absence of direct relationships between indicators of actual development and the expanded political salience of schooling, the results in Table 3 suggest that, over and beyond responding to real problems posed to the state, MPs increasingly activated elaborated cultural frameworks of societal functionalism from the “social sciences” (see section 4 of Appendix, Supplementary material for robustness checks). Still, these models are by no means causal or realistic depictions of history. They artificially disentangle both social scientization from broader processes of cultural rationalization and development. Historically, these processes were mutually constitutive. Therefore, these models should be cautiously interpreted as descriptive, hermeneutic aids to the arguments above.

Discussion & conclusion

In this study, I found that MPs increasingly debated schooling and education (Figure 2), and, as they did, fundamentally redefined schooling and education as they increasingly related them to an ever-wider gamut of political concerns. In the earliest period of distinctive parliamentary debate I identified (1804–1850), schooling was narrowly framed as a minor, though deeply religious issue. If the state had an interest in schooling, it was predominantly expressed in terms of state grants-in-aid for popular religious initiatives and in a broader context of poor relief. As Lord Russel’s speech exemplified, secular state schooling was incommensurable with the prevailing political and cultural logics of the period. While not inconsistent with the British government’s patronizing role in promoting access to education among the poor during this period, this finding is no less important because it shows a considerable lag in the kinds of arguments that MPs were making about schooling – how they associated and embedded schooling in core political problematics – compared to the kinds of theoretical arguments of education’s expanded role in society already then established and circulating (e.g., Owen’s and Bentham’s). This narrow framing of the relevance of schooling to the state persisted well over a decade after the Great Parliamentary Reform Act of 1832 and during the thoroughgoing expansion of the Victorian administrative state.

Between 1851 and 1885, I show how MPs’ views on education had since dramatically evolved. In this period, MPs still debated schooling in the context of religious education and poor relief. Yet, they also started situating state schooling within a larger problematic of social welfare and, importantly, social-class mobility and notions of equality and fairness. Indeed, from my close reading of Lord Nelson’s political speech, British national education was to be a system of equitable redistribution, not only returning to the poor folk what the state “owed” them but elevating them up the social ladder and society. It was also during this period that MPs began debating schooling within a rationalized discourse of empirical social quantification and situating it within a larger, more “rational” system of standards and examinations that interlocked primary education on the one end to university education on the other. In other words, schooling’s broadened political salience to MPs as a state institution that functioned to promote greater societal progress and justice began to resonate broadly with Owenite and Benthamite thinking. Schooling was both an object and means of greater rationality and, thereby, a rationalized means to greater collective happiness.

In contrast to its much narrower salience in the earliest period, by the century’s end (1886–1913), MPs debated schooling in conjunction with an expansive set of diverse political issues and topics. Neither siloed nor narrowly framed, schooling was a central topic densely situated in the political discourse, with MPs having linked it to child welfare, national development, equality and fairness, emigration, the constitution, as well as policing. And they debated it most similarly to how they debated the military, civil service, local governance, as well as other public institutions (e.g., the National Gallery and British Museum). Schooling figured centrally as a state system, in other words, among other state systems. Homing in on Mr. Channing’s comments in committee revealed how MPs linked an advanced education in science and technology to concerns of international competition and Britain’s own survival therein. Whereas Lord Russell argued in 1850 that a secular education was unconscionable and anathema to national interest, by 1902, state investment in a science education – not a religious one – was existentially imperative, increasingly seen as the sole means to invest in human capital writ large and to maintain British global hegemony against foreign economic and military competitors.

When schooling’s discrete political functions are contextualized against the positive trend in schooling’s prevalence in the political discourse in Figure 2, its increased network densities of Figures 3–5, and its positive trend in degree centrality in Figure 6, a hitherto empirically undemonstrated story emerges. It is not simply that statesmen increasingly attended to issues and concerns related to schooling and education over time. That much is well established in the secondary literature as well as by any cursory appraisal of the many Acts of parliament related to schooling and education (Adamson Reference Adamson1930; Smith Reference Smith2022; Simon Reference Simon1974). Nay: instead, as the state got into the business of schooling, schooling assumed an expanded role in the state’s order of business as an instrument for other political goals and policy objectives, indeed, becoming a fundamental component of the repertoire of modern statecraft. The trends in these figures suggest this gradual yet steady transformation in the political discourse about schooling. I show, on the one hand, schooling qua state intervention, whereby the state intervened in education with increasingly systematized (and science-based) schooling. On the other hand, I show state intervention via schooling, whereby statesmen pursued politics by utilizing schooling as a general-purpose tool. This latter process becomes especially pronounced when sequentially comparing the network graphs in Figures 3–5 with Figure 6. While distinctive discourses of schooling and education certainly emerged, there is no constant degree of salience across the periods. A constant degree of salience (a flat trend in degree centrality) would suggest a more or less constant number of (historically specific) economic, political, and social problems over time, which MPs addressed with schooling in their debates. Yet, over and beyond assuming historically distinctive, finite purposes (e.g., Figures 3–5), schooling took on an additional – enduring and compounding – sense of expansive purposiveness, as legislators across the century debated and related schooling in the context of a growing litany of political issues and concerns that they identified as fixable with schooling (Figure 6).

This dramatic redefinition of schooling in the political discourse is consistent with the role that social scientization played in theoretically elaborating the political scope of schooling and, reciprocally, the state itself. State schooling’s expanded functional utility was the preeminent centerpiece of larger theoretical frameworks that constructed and diffused an extended repertoire of increasingly rationalized population policies, such as public health and social welfare (Figure 7), as key solutions to the state’s need to address the problems of capitalist industrial development and societal progress (Burchell et al. Reference Burchell, Gordon and Miller1991). The vast and growing political purposiveness of schooling in the parliamentary discourse that I show enacted in Figures 3–5 was circumscribed by, and thereby only coherent and comprehensible within, a broader ideational context of functionalist social theorization that progressively and more tightly linked state schooling to the advancement of human civilization; to the development of solidarity; to contentedness and welfare of workers and society writ large; to the maintenance of a prosperous and globally competitive economy peopled by skilled workers; to the prevention of crime and dissipation; and to the construction of a coherent, “homogeneous” national culture.

During the course of the nineteenth century, the “social sciences” were progressively reified with new forms of social quantification, professionalized and institutionalized in associations, journals, and universities, as well as integrated into the state apparatus itself. As a result, MPs increasingly saw them as sources of legitimate narratives about how the social world worked, including what they as statesmen could and should do about it. The findings I report in Table 3 provide evidence consistent with this argument: as social scientization underwent intensification, MPs tended to expand the political scope of schooling, discussing it in relation to a growing host of political concerns, independent of the actual problems related to development.

There are therefore three implications for the historical sociological study of state making and state educational expansion. First, the present study provides additional evidence that the nineteenth-century social sciences and social knowledge institutions were far from passive (epi)phenomena but were instead quite active agents of great political and cultural change across the Western system. In contrast, realist (e.g., Tilly Reference Tilly1975) and institutionalist (e.g., Soysal and Strang Reference Soysal and Strang1989) accounts tend to omit the direct role that these social science institutions played in state expansion. Second, the present study suggests that cultural narratives are more than epiphenomena, the purported secondary effects of human and societal development. Instead, the present study shows that the state-centric societal functionalism (Ryan Reference Ryan and Ritzer2005) of the nascent nineteenth-century social sciences was a causally constitutive force in its own right, apart from actual determinants of development, as seen in the educational expansion of the UK state. Third, and together, these first two implications suggest that any explanation of the Western state making project would be remiss if it did not systematically account for the relative (concrete) autonomy of culture, in general, and the specific functionalism propagated and diffused as the social sciences professionalized and institutionalized (Kane Reference Kane1991). In this regard, a main contribution of this current study is the systematic measurement and analysis of how this culture shaped the state making project and in turn how this culture endures in secondary accounts of the expanding state the emergence of state schooling.

In sum, these findings therefore readily suggest a cultural explanation of state making in the nineteenth century. In contrast to prior work that emphasizes growing urban populations, increased political representation, and industrial development as determinants of expanded state structures, the current findings show the transformative power of cultural narratives. In particular, the large, positive, independent coefficients on social scientization coupled with the null coefficients on indicators of economic, social, and political development (Table 3) suggest that, over and beyond real historical conditions, collective visions of deliverance played a causally constitutive role in the expanded nineteenth-century state.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2023.13

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank the extremely helpful and insightful reviewers as well as John W. Meyer, Patricia Bromley, David Labaree, Daniel A. McFarland, Rebecca Jean Emigh, and Jeffrey Beemer for their invaluable feedback on previous drafts. I’d also like to thank the participants of the Stanford Comparative Sociology Workshop for their curiosity and willingness to engage with this historical work.