Introduction

Palliative care adheres to fundamental principles that include affirming life, acknowledging dying as a natural progression, integrating psychological and spiritual facets of care, and offering support to patients’ families throughout the phases of illness and bereavement (O’Neill Reference O’Neill and Fallon1997). The main objectives of these principles are to enhance the quality of life and preserve the inherent dignity of individuals.

Intricately connected to the notion of dignity in the realm of healthcare, particularly within the context of terminal illnesses, is the term “patienthood,” which denotes a circumstance wherein an individual’s illness assumes a predominant role in defining their identity, eclipsing their authentic self. It is imperative to proactively avoid patienthood precluding an appreciation of personhood, especially in cases of terminal illness where this can undermine an individual’s sense of dignity (Chochinov Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2002).

Some studies have been conducted to address the issue of fractured dignity and emotional suffering experienced by terminally ill patients (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2002; Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Cuevas Reference Cuevas, Davidson and Mejilla2021; Julião Reference Julião, Chochinov and Antunes2023) aiming to restore the patient’s sense of dignity and affirm who they are as whole persons. Treating patients with dignity and respect can also positively impact their families (Mc Clement Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007).

Based on these premises, a new method for addressing emotional distress (both for patients and their families) in palliative care has been developed. Dignity Therapy (DT) is a form of brief psychotherapy designed to ease emotional distress in palliative care patients who are grappling with their impending death (Chochinov Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005). The therapy, developed by Chochinov and his team to offer comfort and support to patients as they approach the end-of-life stage, involves a semi-structured interview that uses a series of questions to explore the patient’s life story and how they hope to be remembered by their loved ones or society. The interview is audio recorded, and the transcript is then edited before being printed as a booklet. Patients then have the opportunity to share this with those they choose.

This therapy had significantly improved patients’ anxiety, depression, will to live, and sense of dignity, affirming their core values and generating their legacy (Chochinov Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Julião Reference Julião2014). Additionally, it had also been found to positively impact the way patients’ families cope with bereavement (McClement Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Scarton Reference Scarton, Boyken and Lucero2018). Ensuring the genuine recognition of patients and the preservation of their dignity can significantly assist families and caregivers in grieving their loved ones. Unfortunately, some patients are unable to participate in DT due to the gravity of their illness, cognitive decline, or absence of available dignity therapists. Given this circumstance, Julião and colleagues developed Posthumous Dignity Therapy (PDT), a comparable concise psychotherapeutic approach meant to be carried out by a family member of the deceased patient. This therapy aims to aid the family during their grieving process (Julião et al. Reference Julião, Chochinov and Antunes2023). PDT uses a questionnaire similar to DT, designed to help family members focus on their memories, perceptions, and feelings toward their deceased relatives. This enables them to feel connected to the deceased and provides a tangible way for them to honor and safeguard the memory of the person who has died.

Patients are not just their medical conditions, but individuals with unique personalities, experiences, and relationships. With PDT, bereaved family members can reminisce about all of these, integrating them within their process of grieving and mitigating their emotional distress (Julião et al. Reference Julião, Chochinov and Antunes2023).

When using a novel therapeutic approach, it’s important to recognize the possible effects of inequalities and systemic biases that may arise when applied in a language other than its original (Beaton Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2007). To use the Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions (PDT-SQ) in Brazil, it is necessary to create an adaptation tailored to the country’s cultural context since the original version was developed in Portuguese for use in an European context.

To date, there is no study on PDT being conducted in Brazil, nor studies regarding its effectiveness.

The objective of this research was to translate the SQ for PDT into Brazilian Portuguese and adapt its content to suit the Brazilian Portuguese population. This will ensure PDT is culturally sensitive and provides maximum benefits to caregivers we intend to apply it. We ultimately aim to use PDT to facilitate normal grieving and mitigate distress for those who have experienced the death of a loved one.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study used descriptive methods to cross-culturally adapt the PDT-SQ, within an inpatient palliative care unit at Londrina Cancer Hospital (Londrina, Paraná, Brazil).

Ethical considerations

The Committee of Ethics in Research of Irmandade da Santa Casa de Londrina approved this study under opinion n. 5.714.592/2022. All participants signed an informed consent form (ICF).

Procedures

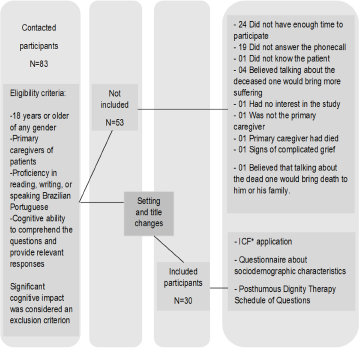

A standard method for conducting cultural adaptation is known as “cross-cultural adaptation.” This method aims to maintain the face and content validity of the therapeutic approach across various cultural settings (Beaton et al. Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2007). The translation process from Portuguese (Portugal) to Portuguese (Brazil) followed the internationally standardized process proposed by Beaton et al. (Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2000). It consisted of 4 stages: (1) translation and synthesis of the original Portuguese (Portugal) version of the schedule of questions into Portuguese (Brazil), (2) back-translation, (3) review by an expert committee, and (4) pretest, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Translation process and cultural adaptation flowchart of the Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions (PDT-SQ).

Stages of the study

Stage 1. Translation and Synthesis of PDT-SQ to Portuguese – Brazil

During the initial adaptation phase (from European Portuguese to Brazilian Portuguese), the original author Miguel Julião was contacted to authorize the adaptation of the PDT-SQ. Then 2 experienced Brazilian Portuguese translators collaborated to create 2 separate translations, known as T1 and T2. These translations were then combined into a cohesive version called T12, under the guidance of the lead researchers. The synthesis process drew upon the original questionnaire and insights from both translators. A comprehensive written report was created to document the entire process, addressing each issue encountered and articulating the strategic approaches used for resolution.

Stage 2. Back Translation

In this phase, 2 other independent translators, without prior knowledge of the original questionnaire, utilized version T12 to perform the back-translation of the set of questions from Portuguese–Brazil to Portuguese–Portugal. Thus, 2 distinct versions denoted BT1 and BT2 were generated and were consolidated into a unified version, designated BT12, by the lead researchers, mirroring the process undertaken in Stage 1.

Stage 3. Expert Committee

For content validation, it’s suggested to engage at least 5 experts to evaluate each part of the instrument (Alexandre and Colucci Reference Alexandre and Colucci2011). In this study, the expert committee consisted of 5 members from a multidisciplinary team with extensive experience in palliative care research and the evaluation of health assessment instruments and the evaluation of health assessment instruments. The team included an oncologist, a nutritionist, a palliative care physician, a psychologist, and an oncology nurse. The committee conducted a meticulous assessment of each component of the PDT-SQ, considering all document versions (original, T1, T2, T12, BT1, BT2, BT12). They assigned a score to each item using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (1 = not representative, 2 = significant modification required for representation, 3 = minor adjustment needed for representation, 4 = fully representative), considering semantic equivalence (equivalence in the meaning of words and the use of equivalent expressions in Brazilian Portuguese); cultural equivalence (adaptation of questions to the cultural reality of the Brazilian population); and conceptual equivalence (different conceptual meanings of words in different cultures). The committee experts had the permission to retain, modify, or eliminate ambiguous or unclear items to achieve enhanced with appropriate justification (Beaton Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2000).

After analyzing the committee’s responses, the Content Validity Index (CVI) was calculated, quantifying the proportion of experts in agreement for each equivalence, derived by dividing the total number of responses receiving a rating of 3 or 4 (indicating minimal change needed for representation or full representation, respectively) by the total number of responses. The CVI was calculated for each item as well as for the entire questionnaire in general (Yusoff Reference Yusoff2019). The outcome of all processes in this stage resulted in the prefinal version of the PDT questionnaire, to be utilized in the pretest version.

Stage 4. Pretest

The purpose of this stage is to detect any possible problems, uncertainties, or insufficiencies in the PDT-SQ. It involves making essential modifications to ensure that the tool is easily comprehensible and consistently understood.

Pretest data collection

Sociodemographic characteristics

For this study, the following data from patients were collected: names, date of death, and hospital register numbers. For bereaved family members, we gathered the name, date, and location of the interview, gender, race, educational level, birth date, hometown, income, religion, marital status, and nature of kinship with the deceased patient.

Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule of Questions

The PDT Question Framework is a set of questions created by rephrasing the DT question framework for application in bereaved family members. The questions were carefully crafted to resonate with this vulnerable population, focusing on reflections regarding their deceased loved one. This meticulous process ensured that the questions were aligned with the foundational tenets of the Dignity Model and DT, making them suitable for use by bereaved family members or friends (Julião et al. Reference Julião, Chochinov and Antunes2023). The questionnaire used for the pretest was the version translated into Brazilian Portuguese following the previous stages.

Pretest protocol

We selected 30 individuals through a convenience sampling method (Beaton et al. Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2000). The participants needed to meet the following criteria: (1) 18 years or older of any gender; (2) must have been primary caregivers of the deceased patients; (3) must have proficiency in reading, writing, or speaking Brazilian Portuguese; and (4) should possess the cognitive ability to comprehend the questions and provide relevant responses. Those with significant cognitive impairment were not considered eligible.

Each one of the questions was evaluated by the participants with YES or NO responses regarding doubts or embarrassment. They were also free to indicate how they would rewrite the rated item so that it did not cause doubt or discomfort. After analyzing all the proposed changes and items that might cause discomfort among participants, the principal researchers (ACKB and BSRP) agreed on the final version of each item, considering the justifications provided at this stage by the participants and the suggestions made by the expert committee (Sousa e Rojjanasrirat Reference Sousa and Rojjanasrirat2011). This version was then submitted for review by the original author Dr. Julião.

Statistical analysis

The analysis describes the data using measures of central tendency (mean and median) for quantitative variables. IBM-SPSS software version 27.0 was used to conduct the analysis.

Results

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

The entire set of 13 questions from the original protocol, along with the title and instructions, underwent a process of translation, back-translation, and subsequent evaluation by the expert committee. Except for item 2, all items received ratings of 3 or 4 from committee members, resulting in a final content validity index of 0.97. Recommendations proposed by the specialists were carefully analyzed and incorporated into the original text, leading to the formulation of the version employed in the pretest protocol. Most of the modifications pertained to grammatical forms and pronouns, aiming to align the content with the linguistic nuances of Brazilian Portuguese. Table 1 displays the recommendations given by the item-specific expert committee, the later modifications made by the researchers to achieve the final version, and the content validity index of each item.

Table 1. Description of the items with modifications requested by the expert committee and respective Content Validity Index

Pretest

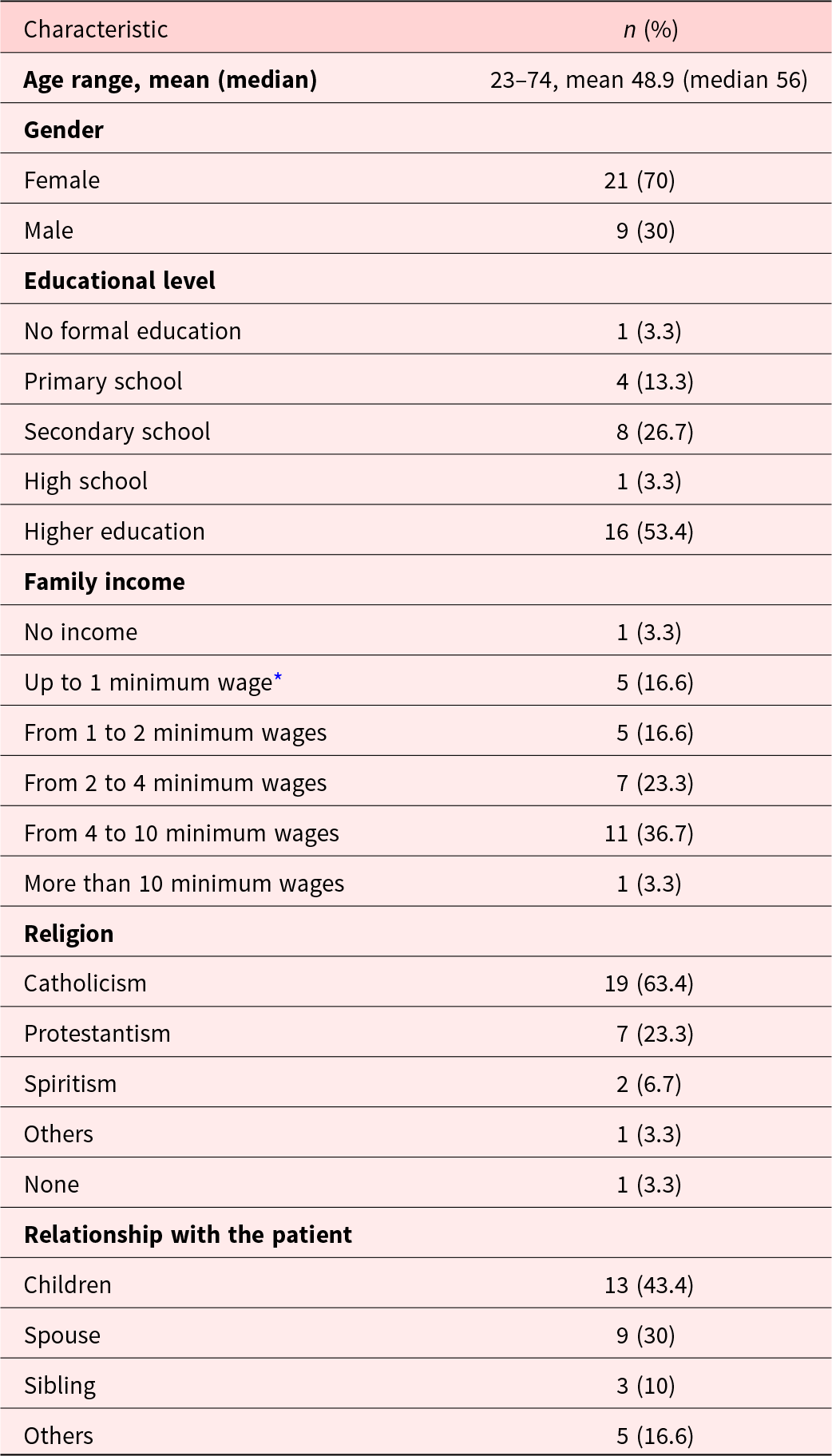

Once the PDT Protocol was finalized, eligible participants were contacted to provide feedback on each item of the protocol, regarding its clarity, understandability, and potential to cause discomfort or embarrassment (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flowchart of the pretest data collection.

During the data collection, it was noted that this therapeutic modality had the potential to be applied also to family members experiencing anticipatory grief, with loved ones in imminently dying processes, or cognitively unable to speak for themselves, leading to the inclusion of those caregivers on the eligible criteria for pre-test participants. Another relevant observation was the word “posthumous” was emotionally jarring, eliciting fear or anguish in some participants (n = 9). Hence, the pretest protocol was adjusted, conducting interviews primarily in person (to provide adequate emotional support, which is more challenging to offer over the phone). We also reengaged our committee of experts to adapt the title of the question protocol, aiming to replace the word “posthumous.” Based on that consultation, the title was revised to Dignity Therapy Question Protocol – in the voice of the caregiver. Changing the name of the protocol, by removing the term “posthumous,” was effective for addressing participants in both anticipatory grief and established grief contexts.

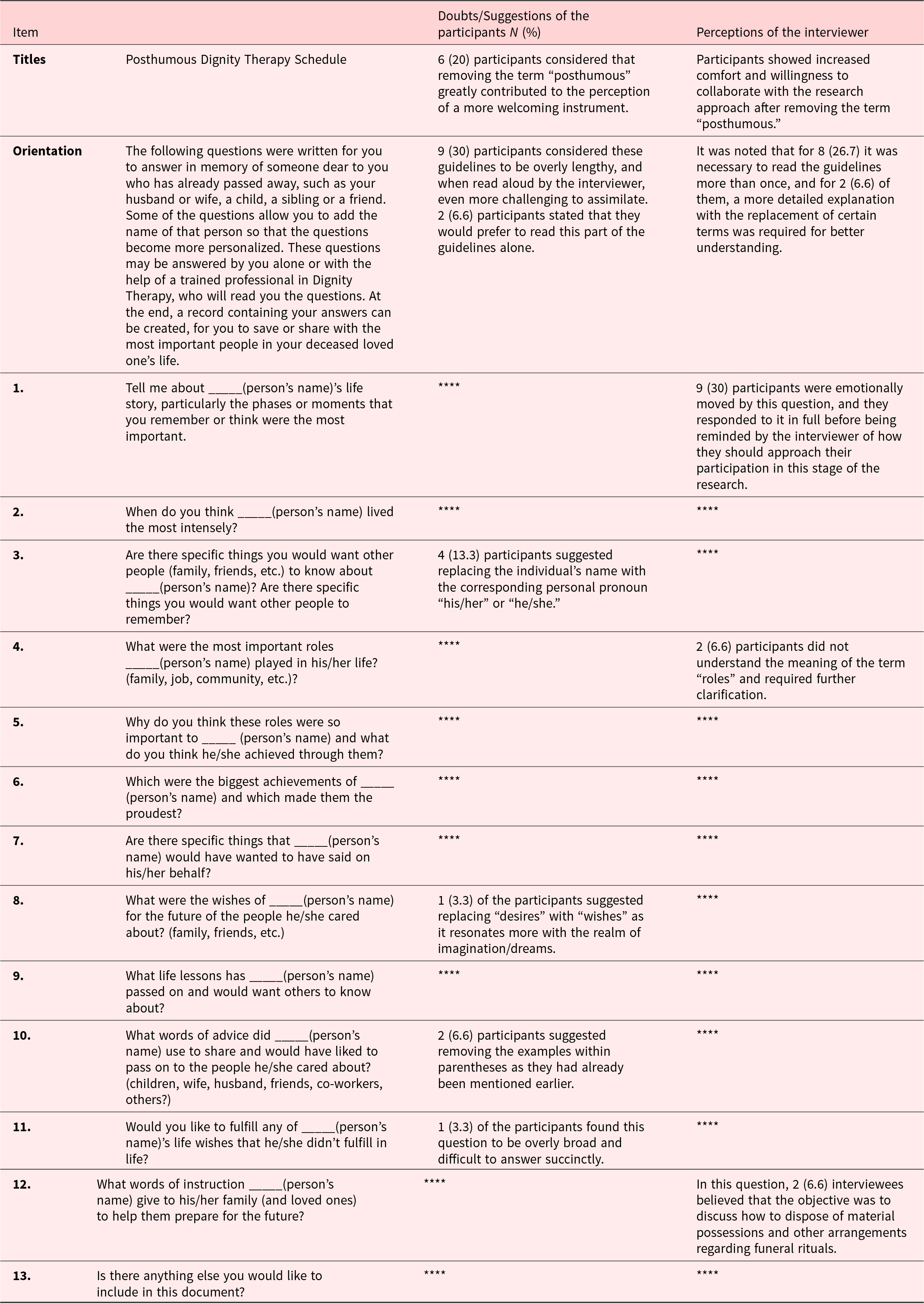

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the pretest family participants (N = 30)

* The minimum wage in Brazil during the data collection period was R$1.302,00 Brazilian Reais (approximately U$ 263,00 US dollars).

During the pretest, the participants raised questions about some items; the researcher’s impressions of what the participants might or might not be understanding were documented (Table 3).

Table 3. Questions and researchers’ impressions of the participants during the stage of the pretest

After analyzing all the procedures, a consensus was reached on the final version of the PDT Schedule (Table 4).

Table 4. The final version of the Posthumous Dignity Therapy Schedule

Discussion

To ensure the reliable application of a therapeutic approach in a population different from the one for which it was originally designed, it is necessary to have it adequately translated into the target language and to culturally adapt it for that new population (Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Lourenço and Prata2023a). This process of cultural adaptation aims to establish equivalence between the original and translated schedule of questions, following the staged approach as outlined by Beaton (Beaton et al. Reference Beaton, Bombardier and Guillemin2007). One way to determine the outcome of this process is to measure its CVI. The higher the CVI, the more confidence we have in the schedule of questions accuracy. While a CVI of 0.80 is considered acceptable (Jokiniemi et al. Reference Jokiniemi, Meretoja and Pietilä2018), we reported a CVI of 0.97, attesting to the reliability of our translation and cultural adaptation.

Studies in palliative care tend to focus on the quality of life for patients nearing death (Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care Reference Watson, Stephen and Nandini2019; Scally et al. Reference Scally, Robinson and Blumenthaler2020). There remains a paucity of death education within the Brazilian populace (Melo et al. Reference Melo, Maia and Alkmim2022; Nascimento et al. Reference Nascimento, Arilo and Silva2022; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Paiva and de Oliveira2023), with death and dying being seen as taboo. We also observed this in the present study, aligning with existing literature, which underscores death as a subject of considerable interest, curiosity, and scholarly inquiry, although notable lack of comprehensive studies and a heightened focus on death education (Boucher et al. Reference Boucher, Dries and Franzione2022; Phan et al. Reference Phan, Chen and Ngu2023). One of the study participants stated that he would not participate in the study because he believed that “talking about someone who had passed away could attract death closer to him or his family members.” This illustrates the deep-rooted prejudice and antipathy still present in Brazilian culture toward topics related to death and dying (Tardelli et al. Reference Tardelli, Forte and Vidal2023; Trevizan et al. Reference Trevizan, Paiva and de Almeida2023).

This entrenched aversion toward death and dying in Brazilian society underscores the importance of cultural validation for an approach meant to elicit conversations about patients who are imminently dying or are deceased. (Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Lourenço and Prata2023a). Given the sensitivity of this topic, it is not surprising we discovered the limitations of conducting research through telephone or video engagement. These platforms raise concerns about confidentiality and privacy (Kang et al. Reference Kang, DeBritz and Hoadley2022). They also create challenges in conveying and interpreting emotions given facial expressions play a vital role in interpersonal communication (Irvine et al. Reference Irvine, Drew and Bower2020; Kołakowska et al. Reference Kołakowska, Wioleta and Mariusz2020); lack of nonverbal communication (Abarca et al. Reference Abarca, Tapia and Pari2023; Lhaksampa et al. Reference Lhaksampa, Nanavati and Chisolm2021); and challenges establishing rapport (Ahmad et al. Reference Ahmad, Mat Ludin and Shahar2022; Carter et al. Reference Carter, Shih and Williams2021; Irvine et al. Reference Irvine, Drew and Bower2020). Therefore, we felt it was preferred for interviews to be conducted in person rather than through either telephone or video calls. This enabled the interviewer to provide appropriate support to the interviewee, such as a gentle touch or reassurance during the expression of emotions (Irvine et al. Reference Irvine, Drew and Bower2020; Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Lourenço and Prata2023a), ever mindful to not add to the burden of those who are grieving and trying to process their loss.

We also discovered the need to revise the intervention title, removing the term “posthumous,” As previously noted, the mere mention of this word evoked a negative emotional response from some participants. Along with in-person interviews, revising the title led to heightened participant engagement and willingness to take part. Just like DT for patients (Uchida et al Reference Uchida Miwa, Paiva and Ferreira2023), we anticipate this version for caregivers holds the potential to positively impact how participants honor and remember their loved ones, and facilitate the grieving process (Julião et al. Reference Julião, Chochinov and Antunes2023).

DT has been empirically proven to effectively reduce suffering, enhance dignity and purpose, and decrease anxiety and depression (Chochinov et al. Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2002, Reference Chochinov, Hack and Hassard2005, Reference Chochinov, Kristjanson and Breitbart2011; Julião Reference Julião2014; Seiler Reference Seiler, Amann and Hertler2024; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Chen and Wang2021) among participants, while also providing comfort for the bereft (McClement et al. Reference McClement, Chochinov and Hack2007; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Chen and Wang2021). This argues for broader dissemination and uptake of DT, considering palliative care sees the patient and Family as the unit of care (Franco Reference Franco, Salvetti and Donato2019). The results of this validation study will extend applications of DT, focusing on the needs of caregivers during the patient’s final stage of life, or initiated during the bereavement period.

A highlight of the study states the fact that the data collection was conducted among caregivers of both deceased patients and those in the dying process. This allowed for a broader context to be assessed, testing the tool across various stages of the patient’s life.

The principal limitation of this study was that it was restricted to one center in Brazil in a city within the interior of Paraná state (Brazil). However, due to the heterogeneous sample collected, we believe our findings are generalizable. Another limitation is that while we have established the validity of the adapted schedule of questions, we have yet to implement and evaluate its impact within a sample of care providers. This will be part of our future program of palliative care research.

The findings from this study will have a significant impact on future research in DT, particularly for caregivers. The study has successfully adapted a therapeutic tool for family members who are dealing with grief, whether it is anticipatory or not. The DT Question Protocol – in the voice of the caregiver has been carefully adjusted and tested within the Brazilian population. It may be used as a practical tool in palliative care settings, and possibly in other family grief situations, to help alleviate the suffering associated with the loss of a loved one.

Through this tool, family members will have a documented legacy of their loved one, providing something tangible to preserve their most cherished memories and teachings. This, in turn, may help to lessen their suffering and support them through the grieving process.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Research Group on Palliative Care and Health-Related Quality of Life (GPQual) – Barretos Cancer Hospital; and the Palliative Care Team at Londrina’s Cancer Hospital.

Author contributions

A.C.K.B. and B.S.R.P. contributed to the design of the study, data collection, and analysis, and draft of the manuscript.

C.M.P. and R.C. contributed to the translation of the schedule of questions; C.E.P., L.C.O., M.U.M., F.B.T., M. J., C.M.P., R.C., and T.C.O.V. contributed as the Expert Committee. M.J. and H.M.C. contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

All authors edited and approved the final version of the article.

Funding

B.S.R.P. was supported by the CNPq Research Productivity Fellow Level 2 – CNPq grant number 313601/2021-6.

Competing interests

None declared.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Committee of Ethics in Research of Irmandade da Santa Casa de Londrina, under opinion n. 5.714.592/2022.