The terms “native farm” and “Roman villa,” often contrasted by historians, stem from a long-standing but still-unsettled historiographical debate. During an important symposium held by the Association d’étude du monde rural gallo-romain (Association for the study of the Gallo-Roman world, or AGER) in 1993, the organizers Didier Bayard and Jean-Luc Collart evoked its premises in words that are still worth citing:

The title “De la ferme indigène à la villa romaine” evokes the work of Roger Agache, the essential reference for northern France.Footnote 1 The concept of “native farms” was developed relatively late in France, in particular by Agache,Footnote 2 to designate settlements known only through aerial photography, characterized by more or less irregular ditched enclosures and attributed to the late protohistoric period. The Gallo-Roman villa corresponds to a concept borrowed from ancient authors, illustrated in Gaul by numerous excavations, that covers a form of agricultural exploitation displaying all the signs of Romanitas: stone-built architecture with a certain monumental flourish, paired with a rigorous spatial organization marked by symmetry, straight lines, and right angles.Footnote 3

The authors went on to point out that although the filiation between La TèneFootnote 4 and Roman settlements had long been postulated, it was at that time based on a very small number of examples: the essential contribution of their symposium was to present new and more plentiful archaeological evidence. There nevertheless remained, and still remains today, a commonly shared impression that the distinction between farm and villa reflects a hierarchy of agricultural land use and different degrees of “Romanization.”Footnote 5 In the first analysis, these two terms refer to the dwellings and working buildings that can be observed through archaeological investigation, which has more trouble apprehending the extension and composition of the land that depended on these structures. As a result, and for want of material evidence, the terms often lead to an implicit semantic shift that manifests itself in two equations which underlie all historical reflection on the Roman countryside: villa equals large estate; farmstead equals smallholding.

Characterizing and naming provincial agricultural settlements using a term as economically, socially, and culturally loaded as villa frequently entails a value judgment. Because it is taken from Latin, the word is often synonymous, in opinio communis, with a civilizational change, a qualitative leap in the agrarian system, a dramatic shift in productive capacity compared to the protohistoric period, and an evolution in the very size of the exploitations. Indeed, the historiographical debate between 1970 and 1990 over the great slaveholding properties was in general waged with little consideration for the actual settlement patterns of the Roman countryside. This was often due to gaps in the archaeological evidence, notably with respect to small rural settlements, which at the time were considered marginal and commonly neglected.Footnote 6 But in northern Gaul—which emperor Claudius (41–54 CE) still referred to by its old name, Comata or “Long-haired” Gaul, in his famous speech before the SenateFootnote 7—these farms, heirs to the protohistoric tradition, were still very much in the majority even a century after the conquest. For more than a quarter of a century they have been regularly uncovered by development-led archaeology projects, profoundly transforming our vision of the countryside with the help of new but splintered, lacunary, and dispersed sources relatively inaccessible to historians. A synthesis of their economic and social importance remains to be written.

Fundamentally linked to the question of elites and the production of wealth, for many scholars the villa, considered as the center of a large estate, nevertheless remains the principal structural element of economic organization in the provincial rural world. The work of Pierre Gros on Roman architecture thus deliberately ignores small settlements, for it is primarily concerned with the main dwelling rather than the ensemble of agricultural buildings per se.Footnote 8 In this traditional perspective, everything unfolded as if the Gaulish countryside were strewn with large agricultural exploitations, the only establishments capable of producing the necessary surplus for provisioning an expanding urban world and a frontier army that counted around 80,000 men in Roman Germany alone at the beginning of the reign of Tiberius (14–37 CE). Despite scholarly attempts over the years to characterize the “non-villa landscapes” of northern Europe, they are still predominately viewed as marginal zones in ecological, economic, and political terms.Footnote 9 However, as early as 1989 Richard Hingley had emphasized the structural diversity of the occupation of the ancient British countryside and the extremely differentiated development, over both space and time, of the villa phenomenon, showing that in some areas it did not appear before the end of the second century, or even the beginning of the third, and that it was especially present in the southeastern half of the island.Footnote 10 In his fundamental investigation into the rural world of this same province, Jeremy Taylor again insisted on this important point.Footnote 11 The same analysis now needs to be carried out for Gaul and the German provinces.

The notion of the economic and social predominance of large estates within the ancient countryside, and of a rural landscape marked by their luxurious villae, can be observed in the approach recently adopted in the Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World.Footnote 12 In his chapter on the production of the early Roman Empire, Dennis Kehoe thus draws the examples that support his argument from an essentially Italian Mediterranean world, focusing exclusively on large aristocratic estates. Put simply, he seeks to show a commercial, surplus-driven agriculture, primarily based on the production of wine and olive oil, for which the excavations at the villa of Settefinestre in Tuscany still serve as a reference. When the provinces are mentioned in this supposedly synthetic analysis, it essentially turns toward Baetica, North Africa, and Egypt, due to their exceptional productivity or the lucrative character of their products.Footnote 13 While Kehoe’s analysis is not questionable overall, it is nonetheless incomplete, for it considers neither the provinces of temperate Europe, which were also prosperous, nor their production, which cannot be reduced to the essentials of self-subsistence. A single sentence of Tacitus, for example, tells us that the provisions for the army of Germania Inferior at the time of the Batavian revolt (69–70 CE) came from inner Gaul, and that by intercepting them the rebels were able to starve the troops loyal to Rome. This offers sufficient evidence for the economic, political, and military importance of the hinterland of the limes, which at that time was not yet a world of villae: apart from a few exceptions, architectural forms of this type were scarcely present in northern Gaul before the Flavian period (70–98 CE), more than a century after Caesar’s conquest.Footnote 14

Of course, the extreme rarity of textual or epigraphic sources for the northwestern provinces of the Empire does not facilitate traditional historical analysis; nor does the continual accumulation of fragmentary and dispersed field data, often difficult to interpret, lend itself to synthesis. Furthermore, most of the data are presented in a gray literature composed of individual reports that often go unpublished. It is for this reason that large-scale research programs are currently being developed across Europe with the aim of bringing these data together, making them available to researchers, and attempting to extract vital information. In Great Britain, the Developer-Funded Roman Archaeology in Britain project, led by Michael Fulford and Neil Holbrook and financed by Historic England and the Leverhulme Trust, compiles excavation reports, puts them online, and is publishing a synthesis.Footnote 15 In France, the Institut national de recherches archéologiques préventives (the National institute for development-led archaeological research, or INRAP) has taken on the task of publishing primary documents from excavations.Footnote 16 The objective of the European-funded Rurland project is to offer a synthesis centered on northeastern Gaul—from the Seine Basin to the German limes—by conducting an investigation based on well-documented “workshop zones” rather than attempting to be exhaustive.Footnote 17 Other European countries, on the other hand, are lagging behind in this regard.

The first question, then, is the complex relationship between essentially heterogeneous sources. On the one hand, literary, epigraphic, and juridical texts furnish crucial information that is nevertheless principally centered on the large Italian, African, or Asian estates. On the other hand, archaeological data, though technical in nature, are fundamental for understanding the reality of the countryside of temperate Europe, where small settlements occupied a position that seems to have been much more important than previously thought. This necessary debate between historians and archaeologists is also an indispensable dialogue between specialists on different periods, namely the Late Iron Age and the Roman era. It is important to establish what role the Gaulish legacy played in the structuring of the Roman countryside and according to what rhythm, by what process, or at which moment (if there was one) one agrarian system replaced another. This debate shows the importance of paying attention to the continuities between the world of the Late La Tène and that of the Empire, passing from one to the other and combining different information and disparate approaches. Indeed, this exercise involves nothing less than a reappraisal of the periodization, in terms of material culture, of the passage from late protohistory to the early Roman era—a shift largely disconnected from a political history that continues to be taught using only textual sources. To this end, an analysis of what the Classical sources reveal will be followed by a consideration of what can be learned from the large-scale excavations of modern development-led archaeology. These have laid bare the grid of ancient rural occupation on surfaces never previously excavated.

Words and Things

It is difficult to identify a specific Latin word for small agricultural settlements. There are certainly a few terms that are often used pejoratively, such as tugurium, for rural huts with various functions: “tugurium is used to signify any structure that is more suited to rural stewardship than urban constructions,” reads the Digest.Footnote 18 In no case does it describe a farmstead and its holdings. As for the word casa, it could describe a rural shack as well as an indigenous urban dwelling,Footnote 19 or even, if we accept Paul Veyne’s tentative hypothesis, tenures located outside the fundi (estates).Footnote 20 But Latin does not differentiate between a farmstead and a grand country residence: ancient authors consistently used the word villa. The polysemy of this term has been repeatedly emphasized,Footnote 21 though all too often in an attempt to establish a typology of settlements organized into contrasting categories (villa rustica versus villa suburbana or villa maritima, for example).Footnote 22 A well-known extract from one of Varro’s Socratic dialogues generally serves as a reference,Footnote 23 and demonstrates in a subtle and ironic way that during the late Republic Romans themselves debated the very notion of a villa, which already encompassed decidedly different realities. These corresponded only vaguely to the functional classifications that historians and archaeologists have attempted to establish, and which they often teach in an overly prescriptive fashion. It is worth citing several key passages in full:

(5) “Do you really mean,” replied Axius, “that this villa of yours on the edge of the Campus Martius is merely serviceable, and isn’t more lavish in luxuries than all the villae owned by everybody in the whole of Reate? Why, your villa is plastered with paintings, not to speak of statues; while mine, though there is no trace of Lysippus or Antiphilus, has many a trace of the hoer and the shepherd. Further, while that villa is not without its large farm, and one which has been kept clean by tillage, this one of yours has never a field or ox or mare. (6) In short, what has your villa that is like that villa which your grandfather and great-grandfather had? For it has never, as that one did, seen a cured hay harvest in the loft, or a vintage in the cellar, or a grain-harvest in the bins. For the fact that a building is outside the city no more makes it a villa than the same fact makes villae of the houses of those who live outside the Porta Flumentana or in the Aemiliana.” (7) To which Appius replied, with a smile: “… For if buildings are not villae unless they contain the ass which you showed me at your place, for which you paid 40,000 sesterces, I’m afraid I shall be buying a ‘Seian’ house instead of a seaside villa. (8) My friend here, Lucius Merula, made me eager to own this house when he told me, after spending several days with Seius, that he had never been entertained in a villa which he liked more; and this in spite of the fact that he saw there no picture or statue of bronze or marble, nor, on the other hand, apparatus for pressing wine, jars for olive oil, or mills.” (9) Axius turned to Merula and asked: “How can that be a villa, if it has neither the furnishings of the city nor the appurtenances of the country?” “Why,” he replied, “you don’t think that place of yours on the bend of the Velinus, which never a painter or fresco-worker has seen, is less a villa than the one in the Rosea which is adorned with all the art of the stucco-worker, and of which you and your ass are joint owners?” (10) [Whereupon] Axius indicated by a nod that a building which was for farm use only was as much a villa as one that served both purposes, that of farm-house and city residence, and asked what inference he drew from that admission.Footnote 24

The dialogue continues with a discussion of the yields produced by this or that type of agricultural activity, showing that the amount of land cultivated was not necessarily what mattered the most:

“Doubtless you know my maternal aunt’s place in the Sabine country, at the twenty-fourth milestone from Rome on the Via Salaria? … (15) Well, from the aviary alone which is in that villa, I happen to know that there were sold 5,000 fieldfares, for three denarii apiece, so that that department of the villa in that year brought in sixty thousand sesterces—twice as much as your estate [fundus] of 2000 jugera at Reate brings in.” … (17) “Was it not Lucius Abuccius … who used to remark likewise that his estate near Alba was always beaten in breeding by his villa? For his land [ager] brought in less than 10,000, and his villa more than 20,000 sesterces.”Footnote 25

This rich and complex text teaches us a number of things: the polysemy of the term; the diversity of ostentation practices, which did not necessarily correspond to the traditional opposition between villa urbana and villa rustica; the variety of surface areas cultivated; substantial differences in revenue and output that depended more on the activity undertaken than the size of the estate, let alone that of the rural dwelling stricto sensu. Above all, it encourages us not to move too quickly when it comes to interpreting archaeological traces.

In a letter he wrote to his friend Calvisius Rufus seeking advice, Pliny the Younger highlighted the complex land tenure system and intermeshed nature of rural estates:

An estate [praedia] is for sale which lies contiguous to mine, and indeed is intermixed with it. … The first thing to recommend it is that throwing both estates into one will make a really fine property; the next, the advantage as well as the pleasure of being able to visit the two estates under one trouble and expense; to have it looked after by the same agent, and almost by the same under-bailiffs [actores]; and to have only one villa to maintain handsomely, as it will be sufficient to keep up the other just in common repair. I take into account the cost of furniture, house-keepers, gardeners, workmen, and all the apparatus that relates to hunting, as it saves a very considerable expense when you are not obliged to keep them at more houses than one.Footnote 26

Further on, Pliny refers to the “moderate but regular profit” that could be drawn from this acquisition, before listing its drawbacks. This text warns us against simply accepting the equation “a villa equals an estate,” or its corollary “a less luxurious villa equals a less productive estate” or a mediocre property—with all the overly hasty implications that follow from this judgment, whether they concern the value of a property, its economic development, or the social position of its owners and/or farmers.

Thus, in most cases it is impossible to establish a correlation between the size and the luxury of a rural residence and the surface area under exploitation. The bronze tabula alimentaria of Veleia, essential for understanding the tenure system of an ancient rural landscape (in this instance, the region south of Piacenza in Italy), never mentions villae; only the value of fundi is recorded.Footnote 27 In this document, the three largest properties—which, incidentally, were not contiguous—are each worth more than one million sesterces (equivalent to the minimal wealth of a senator),Footnote 28 the smallest between 53,000 and 58,000 sesterces. But these figures in no way reflect the size or the value of the different exploitations that were managed by these estates, and still less how they were rendered profitable: a single fundus might well contain one or more villae of different sizes, with lands that could be rented out and/or exploited directly. Likewise, in his study of the tabula alimentaria of the Ligures Baebiani,Footnote 29 a document concerning the region of Benevento during Trajan’s rule and based on the local cadastre, Veyne rightly observed that villae were never mentioned; only land was considered.Footnote 30

The structure of the fundi and the practical organization of rural exploitations within the same property thus remain virtually inaccessible through the rare texts that have come down to us, even if indirect evidence can be gleaned here or there, particularly in Pliny’s correspondence.Footnote 31 In the letter to Calvisius cited above, Pliny details the risks involved in his potential purchase due to the poor yields obtained by the farmers (cultores). Their pignora—the material (tools, animals, slaves, etc.) held as security by the previous owner to guarantee their ground rent—had been sold off, meaning that situation of the tenants had worsened even further. The new owner would have to resupply the farmers with equipment and incur important additional costs to boost productivity. In the meantime, however, the price of the land had dropped, partly for this very reason.Footnote 32 In another letter to Paulinus—we do not know if it was about the same property—Pliny considered replacing rents with dues in kind to prevent the increase of these missed payments.Footnote 33 The locatio nevertheless continued to be profitable in some cases, as demonstrated by another letter in which Pliny asked Trajan for a leave of absence to re-let his lands, located over 150 miles from Rome, because they brought in more than 400,000 sesterces (the census equivalent of equestrian rank).Footnote 34 In an inscription from Rome, a colonus is recorded as paying a significantly lower, though nonetheless substantial, annual rent of 26,000 sesterces.Footnote 35 Not all “farmers,” then, were poor; some even enjoyed a high degree of wealth.Footnote 36 Like jurisprudence, these texts offer glimpses of a complex world made up of contrasts, of landowners and tenants, small or large, and of very different modes of exploitation, sometimes within the same landholding. The nature of a property, therefore, cannot be inferred from the richness of the rural dwelling itself. Moreover, Latin agronomists’ descriptions of productive villae almost never mention the pars urbana Footnote 37 or its eventual decorum, even though they discuss, sometimes with an enormous amount of technical detail, the functional and specifically agricultural parts of the settlement. To state, as scholars have all too often done, that the comfort of the rural residence was a prominent characteristic of the Romanization of the countryside is surely a paradox with respect to what the Latin texts themselves teach us. “A permanent structure with stone components, the villa appeared in Gaul as the most visible and characteristic mark of the Roman colonization of the countryside. … Moreover, the villa was the lasting witness to a way of life whose modalities are illustrated by its layout, its décor, and the objects that have survived underground to the present day,” wrote Marcel Le Glay in his Histoire de la France rurale in 1982.Footnote 38 Today, however, accounts of this sort are largely obsolete. The luxury of a villa—its mosaics, paintings, marbles, reception rooms, and performance spaces—can tell us about the social position and wealth of its owner or tenant, and their tendency toward ostentation, but nothing about the size of the area under exploitation around the residence, and still less about agricultural production. Even in the middle of the countryside, a luxurious villa that was not surrounded by large tracts of land could be only a pleasure house. And the reverse was also true: a humble villa could be located in the middle of vast and productive holdings.

Are considerations based on texts relating to Roman Italy, and perhaps some North African inscriptions, still pertinent when applied to the Empire’s northern provinces? I criticized above the implicit generalization—often due to foreshortening and a lack of editorial space—apparent in the Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World, and I am certainly not claiming that the tenure structure or agrarian system of Gaul were identical to those of Italy. Indeed, Pieter De Neeve emphasized quite clearly that his analysis of the Italian colonate is not applicable to areas outside the Peninsula.Footnote 39 My objective in citing the above texts was simply to remind us of the polysemy of the word villa, which cannot be understood merely as a luxurious country “château,” and of the complexity of a tenure structure and forms of exploitation that, due to the lack of administrative and juridical information specific to each province, have largely escaped our attention.Footnote 40

This initial reflection based on epigraphic and historic sources shows the extent to which the notions of villa and farmstead must be employed with caution. In these texts, not every rich villa is necessarily located at the center of a large estate, and a mid-sized rural dwelling, indeed any dwelling bereft of comfort, does not imply ipso facto a small peasant landholding. They thus invite us to question the economic and social analysis of land use developed by archaeologists and the interpretations that can be drawn from it. Field data almost never reveal the physical size of a tract of exploited land, and in most cases they exclusively concern the built settlement itself—though even these structures are too rarely known in their entirety, since research has traditionally focused on dwellings (especially luxurious ones) rather than on productive facilities. It is nevertheless on this concrete observation of a site that archaeologists depend in order to offer the most detailed and complete analysis possible of the complex they are excavating. The relevance of these material criteria for the economic and social analysis of the countryside must therefore be examined from the perspective of archaeological sources.Footnote 41

The Hierarchy of Agricultural Settlements and Archaeological Sources

In broadly schematic terms, archaeological investigation can proceed in three ways, each of which has particular biases that make it difficult to use the evidence produced without caution, or to simply compile it without adequate commentary: aerial surveys, field surveys and excavations.Footnote 42 Aerial surveying has had an unquestionably great heuristic value, making visible hundreds of large villae that were unknown before the 1960s. Following pioneers such as John Kenneth St. Joseph in Great Britain, scholars such as Agache in Picardy, René Goguey in Burgundy, or Otto Braasch in southern Germany (to cite only the most well-known) revealed a form of rural occupation that had been generally obscure up until that point. But these investigations produced a partial and thus biased image, from which historians have had difficulty escaping. The widespread influence of Agache’s work in particular has long fixed the idea of a predominance of vast, luxurious villae situated in the center of large estates principally devoted, then as now, to cereal production.

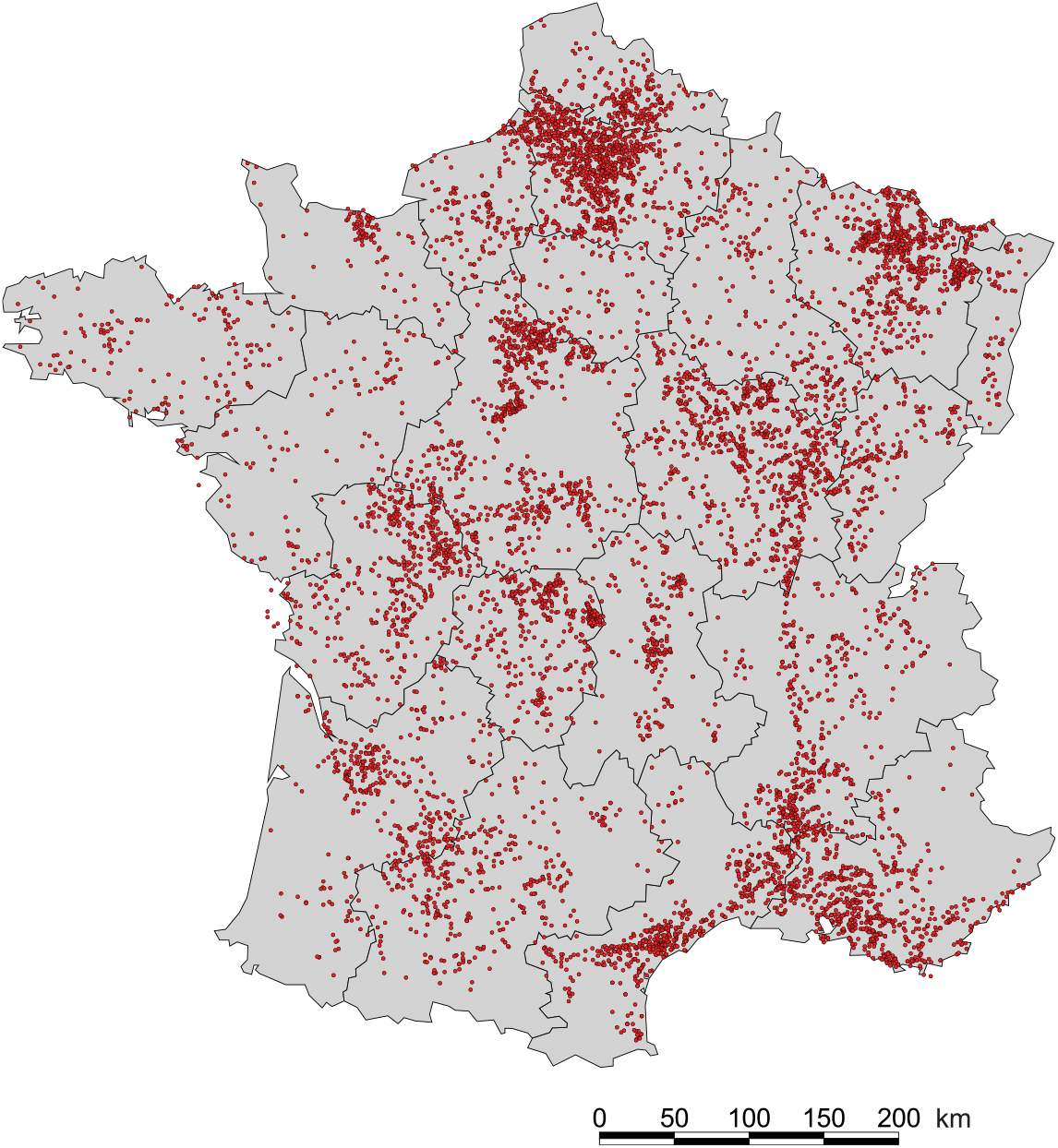

Figure 1. Map of the archaeological sites in “long-haired Gaul” mentioned in the text

For its part, the map based on the data provided by the French Ministry of Culture gives a very erroneous impression of the spatial distribution of villae from the Roman period (fig. 2). Thus, just to the west of Picardy, in Upper Normandy, they seem to disappear. This is not a result of the surveying—Agache had flown over these areas—but of the soil itself, whose clayey nature conceals buried structures that do not produce enough contrast to be observed from an airplane. Furthermore, aerial photography often identifies only certain buildings and privileges permanent structures: even though Agache observed numerous “native farms” in the Somme Valley—which he had trouble dating (were they protohistoric or from the Roman period?)—in reality he had only spotted a small portion of them.Footnote 43 Presented together on the same topographic map, the data from aerial surveys and those from more recent large-scale excavations do not always overlap. Despite its remarkable character, the investigation thus had significant deficiencies, and this was especially true when it came to the crop of small settlements that did not consist of permanent structures—even now we are familiar with only some of them, in locations where the demands of modern economic development have prompted excavations. For instance, in the immediate surroundings of Amiens, aerial surveys detected several villae (represented in fig. 3 by clear triangles) and small agricultural exploitations characterized by enclosures but not dated, which could be either Roman or protohistoric. Since then, a number of protohistoric settlements (gray squares) that had not been spotted by Agache have been excavated, some of which remained active under the Empire (black squares). This map also reveals the density of rural occupation and the proximity of all types of settlements on the same territory. Similar observations can be made for other regions, for instance the area around Dijon, where aerial surveying was intense but only very partially overlaps with the information produced by development-led archaeology, demonstrating that our vision of land occupation cannot be limited to one type of source, however exceptional and spectacular. In both cases, aerial detection seems to have placed a significant premium on spotting large villae, overrepresented in archaeological inventories.

Figure 2. Map of Gallo-Roman villae recorded in France

Figure 3. Simplified map of the agricultural settlements around Amiens

Field surveys have the merit, when methodically carried out over a number of years, of revealing ephemeral evidence that is often invisible from an airplane; they furnish useful additional information, especially in terms of gathering material evidence and thus providing dates. In addition, they provide valuable maps showing spatial and temporal distribution, and have prompted important research programs, of which the most well-known and emblematic is probably Archaeomedes, which focuses on the Midi.Footnote 44 They are nonetheless not without their own intrinsic limits, often denounced by specialists themselves. The interpretative element is indeed sizeable, for it is necessary to move from collecting material scattered over a vast surface to identifying a building or cluster of buildings (large villae, medium or small farmsteads, isolated buildings, sanctuaries, necropoles, agglomerations, etc.) without delving into the soil. One must rely on the “surface trace,” whose size, analysis, and chronology all present potential sources of error. Every archaeologist has his or her own categories, with the result that the maps produced are rarely homogeneous, and can lead to doubts and difficulties as soon as one tries to collate them.Footnote 45

Excavations, on the other hand, provide much more thorough investigative methods, but rarely have the means of exploring a rural settlement in its totality: even when limited to built structures, the surfaces involved are considerable, while the so-called “off-site” zones (the ager proper, the cultivated zone) often fall outside the prescriptions of heritage services. Most of the time, field archaeology thus remains an aspiration rather than a reality. Moreover, when it comes to development-led archaeology, the work site is almost always limited to the area under construction, and not to the archaeological site as a whole. This means that numerous agricultural settlements are only partially explored, especially in France.

Whatever method is used, archaeologists thus detect essentially built structures rather than the extension of the ager,Footnote 46 and this is true not only for stone buildings but also for structures made from perishable materials, whether protohistoric or Roman. In this context, it is evident that the size of the occupied surface itself should be considered an essential hierarchal criterion.Footnote 47 But how to calculate it? When specialists of the Roman period were interested principally, if not exclusively, in the luxury of the rural residence, they tended mainly to take into account the dimensions of the pars urbana and the elements of “comfort” it contained: paintings, mosaics, marble, statuary, and so on. The hierarchy was essentially based on criteria of an architectural order, and in general field surveys today continue to place a premium on building elements (tiles, blocks of stone, mortar, suspensura, tessellae, painted plaster, etc.), though now with a significantly more astute analysis of ceramics and imported materials. Such an approach ipso facto relegates structures lacking characteristic “Roman” building techniques to the bottom of the scale, where they were long qualified as “native farms”—a term with pejorative connotations.Footnote 48

During the excavation of the villa at Champion (Hamois, Belgium), Paul Van Ossel and Anne Defgnée produced an overview taking into account the surface area not just of the pars urbana, but of all the buildings, including those of the pars rustica, whether or not they were enclosed within a clear physical boundary.Footnote 49 Their hierarchy ranges from 0.36 to 0.76 hectares for the smallest villae (Cernay, Hambach 403) to 16.48 hectares for the most important (Orbe-Boscéaz), or, in Roman measurements, from between 1.5 and 3 jugera to more than 65 jugera. The overall footprint of the edifices and the courtyards is thus taken into account, a practice that has the merit of closely resembling that of protohistorians, who also evaluate all structures within an enclosure.Footnote 50 Although incomplete, this picture indicates the broad range of exploitations—all dating from the Roman period—that were to be found in northern Gaul; the largest surface considered is forty-six times the size of the smallest. But while this method is globally relevant and generally adopted by archaeologists today, it can nevertheless lead to some paradoxes.

Several recent excavations, notably at Conchil-le-Temple in the Pas-de-CalaisFootnote 51 and Batilly-en-Gâtinais in the Loiret,Footnote 52 have highlighted the protohistoric origin of large villae with “multiple aligned pavilions.”Footnote 53 These constitute, as it were, the paradigmatic villae of northern Gaul, with their separate courtyards, one set aside for the master and his household, the other for agricultural exploitation per se (fig. 4c). Agache’s aerial surveys had uncovered numerous examples from the Roman period, suggesting a protohistoric origin that at that time was indemonstrable. Though structurally comparable, the range of surface areas nevertheless reveals some surprises: the internal enclosure at Batilly, which includes the living area, covers a surface of 1.95 hectares, while the external enclosure, with its pavilions, has a footprint of more than 19 hectares, which is considerable. In the hierarchy presented by Van Ossel and Defgnée, this Late La Tène aristocratic dwelling, decorated with painted plaster, would figure at the very top, easily ahead of the largest Roman villae—a strange and ironic paradox that contravenes all preconceived notions. Meanwhile, the layout of the complex at Bliesbruck-Reinheim, straddling the border between Lorraine and the Sarre, reveals an enormous ensemble within which the urban agglomeration at Bliesbruck seems ridiculously small compared to the vast neighboring estate at Reinheim. Nevertheless, this villa’s pars urbana has a footprint of around 0.5 hectares, which, with a 40,000 square meter courtyard, makes a total of less than 5 hectares, almost four times smaller than that of Batilly.Footnote 54 The Italian villa of Settefinestre, widely regarded as the prototypical large, late-Republican slave estate, pales in comparison: less than a hectare for the residence, courtyards included, plus the dependences situated to the west and southwest, and a hortus of slightly more than 1.5 hectares. But this does not mean that it was economically less profitable. In other words, it seems that the dimensions of the built area, augmented by those of the courtyard or the overall footprint of the installations, represent only one criterion in the hierarchy of agricultural settlements. It follows that others, more directly functional and unconnected to the wealth of the dwelling itself, must be taken into consideration.

Figure 4. Diagram showing the layout of different kinds of agricultural settlement

The spatial distribution of the buildings within agricultural complexes has recently been investigated by Diederick Habermehl, who offers a useful overview based on a few concrete examples.Footnote 55 But his tendency toward typological classification—a constant of archaeology as a discipline—is not accompanied by a reflection on the size of the models, much less the functionality of their components. A few examples make this clear. The numerous small settlements uncovered in the lignite mining zones (the BraunkohlenrevierFootnote 56) west of Cologne are no less villae, in the Roman sense of the term, than much larger establishments. The same goes for the large rural palace at Blankenheim, excavated in the early twentieth century by Franz Oelmann fifty kilometers to the south in Eifel, a region noticeably less rich from an agricultural point of view than the loess of the northern piedmont, but possessed of important mineral deposits. Only a minority of the small villae of the Braunkohlenrevier have baths, generally considered a social marker characteristic of, and indispensable to, Romanitas.Footnote 57 But does this mean that they were less productive? Can we deduce their agropastoral activities from their layout and size alone?

The function of the peripheral buildings in the principal courtyards of axial villae remains difficult to interpret (fig. 4). According to the most widespread view, the pavilions aligned along the length of the enclosure were reserved for dependent workers in an architectural hierarchy reflecting that of rural society. This is the argument made by John Smith, who considers that it could also apply to the whole of the pars urbana, including the main residential buildings. However, this is by no means certain.Footnote 58 Recent excavations, such as those at the villa at Champion in Hamois, have shown that these pavilions had an essentially economic function, devoted to the classic activities of agricultural work (storage, a forge, etc.).Footnote 59 It is certainly not impossible that some of these structures could have had a second story that housed dependents and their families, but the purely “social” interpretation of this type of layout has certainly not yet been borne out by archaeological evidence. Other examples, such as the excavation of the large villa at Dietikon in Switzerland, indicate the multifunctional, variable character of these buildings.Footnote 60 At Bieberist in the Aar valley, Caty Schucany has likewise excavated a series of buildings, some of which were intended for habitation, but others for economic activities.Footnote 61 The recent excavation of the villa at Damblain in the Vosges has testified to the rapid evolution of the various functions assigned to the structures lining the courtyard of the pars rustica, and to the difficulty that arises from interpreting them only according to their layout.Footnote 62

Thus, these large villae with “multiple aligned pavilions” do not follow an unambiguous organizational blueprint, peculiar to northern Gaul, that could be “overlaid” onto a shifting archaeological reality without in-depth reflection. There is no clear physical evidence for a habitation organized according to social hierarchies around the home of the dominus. The development of this type of large villa, moreover, is complex. Although Iron Age prototypes do exist, most appear significantly later, sometimes after a long process of architectural evolution. Two emblematic examples in Picardy, Béhen-Huchenneville and Martainneville, have recently been studied as part of a synthesis on the large-scale linear excavations undertaken in the region.Footnote 63 At Béhen, as the evolution of the layout shows (fig. 4d), the settlement did not take the form of a villa until the second half of the second century CE, and even then its buildings remained relatively dispersed; they were not gathered around a courtyard until the third century, at the end—not the beginning—of a process that conferred the specific appearance long thought to be peculiar to the large rural estates of northern Gaul, such as Anthée in Belgium or Warfusée in the Somme. The traditional settlement thus persisted at least until the early second century without adopting the Batilly model (though this layout had been known since La Tène D2), and it was only transformed into a “Roman” villa half a century at most before its disappearance toward the second third of the third century. A similar evolution can be found at Martainneville or other examples in Great Britain.Footnote 64 If the size and the layout of the built elements can present hierarchical criteria among rural settlements, it is also important to consider their chronological and spatial evolution—their “trajectory,” to use a word in vogue among archaeologists. The layout visible in aerial photography or detectable as a “soil mark” during ground surveying is often that of a structure’s final version, and this surely represents one of the most important biases inherent in our vision of the occupation of the countryside. Ultimately, we are once again dealing with observations of an architectural nature that provide relatively little information on agropastoral activities, except when we can highlight specific installations.

When it comes to cereal production, which, perhaps under the influence of modern agricultural production, is postulated almost automatically, even unthinkingly (as with the large villae of PicardyFootnote 65), the best criteria are incontestably furnished by the size and the nature of storage buildings on the one hand, and by the analysis of archaeobotanical remains, when they are preserved, on the other. In the first case, the archaeological approach is often difficult insofar as many granaries have been comprehensively leveled and elude definitive identification, although progress has recently been made in recognizing and inventorying them.Footnote 66 Estimating the storage capacity of ancient agricultural settlements obviously constitutes a key element in understanding their economic role. Habermehl has created a small comparative typology that shows the sometimes considerable difference in size between the installations observed.Footnote 67 Yet the principal difficulty lies in accurately evaluating the volume they could hold, which poses more technical problems than might be expected.Footnote 68 Archaeobotanical identification, meanwhile, has significantly advanced in recent years and testifies to a significant differentiation, over time and space, between zones producing varieties of cereal that were far more diverse than simply naked wheats.Footnote 69 Although the methodological tools of archaeology are increasingly refined, there is still no magic solution for classifying and ranking rural settlements. The generally established criteria (surface area, typology, construction method, materials, luxury features, types of installations, etc.) obviously have intrinsic value, but also involve biases that can lead to serious miscalculations if used incautiously.

This also applies to calculating the area of the fundi. Once again, Van Ossel and Defgnée’s study of the villa at Champion in Hamois provides a good example to ponder. Its authors propose a model of spatial analysis starting from a central point—the agricultural settlement itself—surrounded by circles of varying radii superimposed over an area analyzed according to its pedological properties, which in this case are quite varied.Footnote 70 The result is significant: soils suitable for agriculture are barely present in the villa’s immediate environs (within a radius of 250 meters), but are much more prevalent within a radius of 500 meters and beyond; by contrast, those suitable for raising livestock are closer to the agricultural exploitation. In other words, the evaluation of a property’s productive capacity and the nature of that production depends not only on the reconstituted dimensions of its ager, but also on the quality of its soils, their diversification, and their spatial distribution, three elements that are difficult to quantify, especially on the scale of a fundus, and as a result are rarely taken into account by historians.

The reconstitution of the surface area of a small exploitation in the hinterland of Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (Cologne) has been attempted based on different criteria. The land dependent on the villa Hambach 59,Footnote 71 delimited by ditches that can be at least partly tracked, is estimated to have measured between 40 and 50 hectares (or 160 to 200 jugera), with a villa of between 1.5 and 1.78 hectares, including its courtyards.Footnote 72 Similar results have been obtained in the same sector by Wolfgang Gaitzsch, who, working on totally stripped surfaces, discovered an average distance of 1,000 meters between different settlements of the same type. By tracing tangential circles with a 500-meter radius using each main building as a centroid, he likewise defined surface areas of around 50 hectares.Footnote 73 In this almost wholly excavated landscape, where the forms of land use were relatively homogeneous despite a few variations from one sector to another, the model seems pretty convincing, perhaps the result of an initial allotment of land in a region whose dense occupation effectively began around the middle of the first century CE, when the Oppidum Ubiorum was promoted to a Roman colony. The rural dwellings were, however, hardly luxurious, and often lacked bathing facilities.

The density of the villae observed by Agache on the Santerre plateau east of Amiens is such that the distance between the settlements is close to 1,000 meters, just like in the hinterland of Cologne. But here the installations were physically much larger—notably because of their axial morphology and the presence of a vast courtyard—and are often judged a priori to be more luxurious than those of the Braunkohlenrevier, even though most of them have not been excavated. Our sociohistorical interpretations of rural life thus depend on our archaeological perceptions, since there existed very different types of settlements that were virtually identical in size. We must also consider that the small farms observed by development-led archaeology around Amiens are largely undocumented on the map of the neighboring region of Santerre, and that their virtually certain yet invisible presence also distorts how we view the density of the exploitations and the extent of their ager, their interconnections, and their possible relations of dependence (fig. 3).

As a Romanist, it is interesting to observe that today’s protohistorians reason according to a process and with criteria that, while distinct, are nonetheless parallel. François Malrain, Véronique Matterne, and Patrice Méniel have tentatively estimated the surface area necessary for an Iron Age II farm to be viable.Footnote 74 Their calculation is based on several excavated farms and the size of the storage areas identified. The assumption that these were for cereals can certainly be challenged, but it furnishes a base estimate for grain piled to a height of 0.40 meters, quite low but more realistic than the higher estimates that are sometimes made.Footnote 75 The figures are then multiplied by the density per cubic meter of the cereals, namely wheat and barley. Even if the calculation contains numerous biases, particularly when it comes to how the cereals were stored (as grains or as ears?), the estimate of the cultivated surfaces at the site of Chevrières “La plaine du Marais” (Oise) comes to around 19 hectares of wheat or 16 hectares of barley under extensive cultivation, with broadcast sowing yielding 5 quintals per hectare, or 6 hectares of wheat and 5 hectares of barley under intensive cultivation, with row planting yielding 15 quintals per hectare. The authors evaluated other examples in the same way, adding estimates for meadows and woods. Their reasoning, for which I have provided the barest outline here, suggests an exploited surface of around 60 hectares, an average that could be adjusted up or down depending on the crops cultivated, the quality of the land, the wealth of the proprietor, and so forth. It is nevertheless interesting to compare this average figure with those calculated by much simpler methods for the Roman period in northern Gaul, in particular the settlements of the colonial ager in the Braunkohlenrevier. From one era to another, the economic viability of an agricultural settlement, whether farm or villa, thus rested on roughly comparable surface areas.

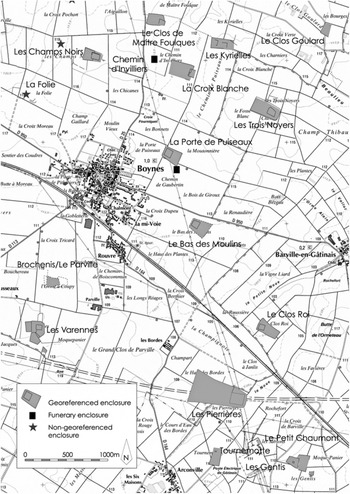

The current approach of Late Iron Age specialists contains new elements that break from the traditional argument of Romanists. Nearly twenty years ago, the discovery of aristocratic residences in independent Gaul and the concern with defining hierarchic criteria prompted several attempts to classify Iron Age rural settlements—the very establishments that specialists of the Roman era still readily characterize as farms.Footnote 76 Returning to the question in a recent article that draws on the dissertation of Yves Menez, Stephan Fichtl has listed criteria that closely resemble those taken into consideration by Romanists: the surface area of a site; the presence of an elaborate architectural layout with hierarchic functions; monumentality; the richness of building materials and furnishings (evaluated through ceramic vessels and metal objects); and food quality (the study of bones revealing which animals were consumed).Footnote 77 Analyzing the map of the area near Batilly-en-Gâtinais, Fichtl highlights the density of protohistoric rural settlements around Boynes (Loiret) that according to the criteria just listed can be classified as aristocratic residences (fig. 5). However, these seem to have been outstripped by that at Les Pierrières, which at almost 20 hectares dominates this dense and close-knit crop of settlements situated an average of 200 to 500 meters from one another. If the hierarchy of habitations is clear, describing the estates remains difficult, if not impossible, since we have no knowledge of the potential relationships of dependence between all these sites occupying an area of around nine square kilometers. Was the proprietor of Batilly also the owner of neighboring exploitations? Or was he just a particularly rich aristocrat, whose ostentatious dwelling was not necessarily reflected in the exploitation of a larger ager? Or were his lands dispersed, with a portion located far from his residence? Theoretically, each of these different solutions might be possible, but we have no way of knowing which one is correct.

Figure 5. Density of Late Iron Age rural settlements near the aristocratic residence at Batilly-en-Gâtinais, Loiret

This analysis of the functional hierarchies of rural settlements uncovered within the same area by large-scale excavations leads to questions that are not so different from those inspired by Latin texts. If it is possible to grasp the physical structure of these settlements through archaeology, the tenure structure continues to escape analysis, as does the material organization of production within a particular exploitation. Only archaeobotanical and archaeozoological studies, when they exist, can provide an idea, but as the quantification of production and the reality of the yields remain out of reach, this is still approximative. Deprived, perhaps forever, of these essential elements, we have trouble evaluating economic and social relationships in the countryside. On this point, Classical sources provide only limited help, but they do offer an indispensable global framework for reflection. Nevertheless, they cannot serve as the single basis for historical thinking on the ancient countryside, since they largely overlook the material context that only archaeology can provide, especially in the provinces of temperate Europe.

Specialists of the Roman rural world have noted the obsolescence of the traditional classifications opposing native farms and Roman villae for quite some time.Footnote 78 It is doubtful, however, whether these new approaches to the countryside of northern Gaul have spread beyond a small circle of scholars; in any case, they have not yet appeared in history textbooks. It is also important to highlight another fundamental point: the slow pace and gradual nature of the evolutions that marked the rural habitat between the Late Iron Age and the Roman period must be taken fully into consideration, alongside an in-depth study of agricultural production and the agropastoral system.Footnote 79 Indeed, almost nowhere did rapid change take place after the conquest, and it was not until at least the reign of Claudius, or even the Flavian period, that villae replaced—and very partially at that—the farms whose principal Iron Age characteristics remained significant a century after Caesar. It is possible to analyze them in terms resembling those used by protohistorians, and to take this observation into account when interpreting the province’s evolution and formulating historical explanations. In any case, the still widespread notion of a complete restructuration of the countryside of northern Gaul from the very beginning of the Empire, of the rapid and brutal replacement of one agrarian system with another in the decades that followed the conquest, and of a sudden economic take-off linked to colonization from Italy must be completely rejected. It is thus essential for reflection on the Roman period to pay more attention to the protohistoric heritage and to the persistence of this dense scattering of small settlements, long concealed by the omnipresence of the villa as the sole operative concept.