Introduction

Since the financial crisis hit the world economy and the sovereign debt crisis hit several European countries, the long-term decline of the Italian economy became overshadowed. However, it is not possible to understand the current state of economic fatigue of Italy, and its being a constant source of worry for Europe, unless we can make sense of the economic decline that occurred before the financial and economic crisis. This paper challenges mainstream interpretations and argues that the economic decline of Italy from the mid-1990s to the eve of the financial crisis was largely the result of institutional change leading to the hybridization of its model of capitalism. This conclusion has empirical and theoretical implications that reach beyond a single southern European country and are of broad interest to scholars concerned with the causes of the economic decline of nations. Indeed, a number of factors make Italy's decline a critical case in the study of European capitalism.

Italy was a successful economy in the post-war decades; until the late 1980s, it outperformed the average growth of Western Europe. Instead, it has underperformed since the mid-1990s, and increasingly so over time. In 2010, that is, in the aftermath of the financial and economic crisis, Italy was the only EU country with a GDP per capita lower than in 2000.

This performance is even more puzzling if one observes the numerous market-friendly economic reforms approved in Italy in the 1990s. Deep changes affected virtually all the institutional spheres of Italian capitalism, including the labor market, industrial relations, corporate governance, finance, education and competition, among others (see Barca, Reference Barca2006 for a full list). Reforms were carried out by governments of different partisan orientations, yet there is no record of major policy reversal. In sum, Italy is a case of economic decline that followed a series of market-friendly institutional changes with no clear partisan bias.

This paper tests the following hypothesis: that the economic decline is the result of an increased hybridization of the Italian model of capitalism.

Hybridization is understood as a process whereby neither market-based coordination (LME-type), nor strategic coordination (CME-type) prevails across the economy and across institutional spheres, as a consequence of incoherent institutional change. By addressing this hypothesis, this paper provides a new test to the core contention of the Varieties of Capitalism (VoC) theory: that institutional coherence systematically underpinning market coordination or strategic coordination among economic actors is conducive to stronger economic performance than other, more hybrid, institutional settings (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001). This paper does so by examining the counterfactual, that is, whether economic decline can be thought to derive from increased institutional incoherence. Italy is the ideal choice for such a test because economic decline followed large-scale institutional restructuring, and because in the decades before such change, it performed better than any other European country. In other words: the performance swing was the largest observable in Europe.

Previous literature has questioned the suitability of the VoC dichotomy between Liberal Market Economy (LME) and Coordinated Market Economy (CME) to correctly encompass different capitalisms. Amable (Reference Amable2003) suggests that five, rather than two, typologies are necessary to understand the dynamics of economic performance and the interplay between institutional configurations and their socio-political underpinnings. In turn, Colin Crouch (Reference Crouch2005) suggested that a more nuanced and detailed mapping of capitalism is necessary in order to ‘accommodate and account for change taking place within empirical cases’ (pp. 440) while avoiding functionalism and determinism. Additionally, some literature has argued that at times incoherent institutions might be conducive to good economic performance (see Höpner, Reference Höpner2005).

These critiques to the VoC approach could only be partially countervailed by the main empirical assessments of the VoC contention (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy2006; Hall and Gingerich, Reference Hall and Gingerich2009). In fact, because institutions typically move slow, all these works predominantly focus on the cross-country dimension and comparative statics, with limited scope for within-country variation.

Instead, by focusing on developments over time within a single country, while taking seriously the VoC core claim, this paper aims at bridging these two literatures. In short: the aim of this paper is not to explain change [as it is done, e.g., by Jackson and Deeg (Reference Jackson and Deeg2012) and literature cited therein], but to assess its consequences.

It starts, in the next section, by discussing the most common explanations of Italy's decline.

Interpretations of the Italian economic decline

The ‘algebra’ of Italian economic decline can be derived from GDP decomposition and related quantitative analysis based on standard economic models that understand long-term growth as determined by technical advancement (Daveri and Jona-Lasinio, Reference Daveri and Jona-Lasinio2005). Such analysis shows that economic decline in Italy depended on a decrease in labor productivity in the manufacturing sector since 1995, as a consequence of declining total factor productivity, while capital deepening remained roughly constant over time. Between the 1970s and the 2000s, Italy lost comparative advantage in sectors characterized by high expenditure in R&D (and by incremental, rather than radical, innovation patterns) such as the automotive industry, office equipment and electrical machines, and retained comparative advantage in low R&D sectors such as textiles, furniture, and clothing. However, because the latter are also characterized by declining global demand (Faini and Sapir, Reference Faini, Sapir, Boeri, Faini, Ichino, Pisauro and Scarpa2005) as a consequence of declining TFP, Italian exports failed to keep pace with global trends.

In short, empirical studies argue that the Italian economic decline is a direct consequence of a declining capacity to innovate, which is accounted for as declining total factor productivity in the manufacturing sector (also: Ciocca, Reference Ciocca2003; Castellani and Zanfei, Reference Castellani and Zanfei2004; Boeri et al., Reference Boeri, Faini, Ichino, Pisauro and Scarpa2005; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lotti and Mairesse2007).

Tables 1 and 2 provide a simple summary of such declining trend which, it should be noted, was a relatively quick reversal compared to the previous decades. Between the postwar years until the late 1980s, Italy's economic performance was consistently stronger than the EU15 average. Then, since the early 1990s, TFP slowed down and then started decreasing, dragging down output per head. In the 7 years that preceded the 2007 financial crisis, the average yearly growth was negligible. In 2010, after the economic downturn following the financial crisis, Italians were poorer than they were in 2000.

Table 1. Average year-on-year TFP growth and GDP per capita growth

Source: AMECO Database. Growth for Germany in 1990 set to zero.

Table 2. Average year-on-year TFP growth

Source: AMECO Database. Growth for Germany in 1990 set to zero.

Conventional interpretations of Italian economic decline follow the flexibility–productivity nexus that formed the basis of the international political economy consensus during the ‘Great Moderation’ period (OECD, 1994; IMF, 2001). This view contends that productivity decline was driven by insufficiently competitive domestic markets (capital, labor, and services) in the presence of increasingly internationalized markets (Ciocca, Reference Ciocca2003). In turn, the culprit of decline was to be found in special interest politics, which successfully blocked attempts to structural reforms, also known as liberalizations and privatizations.

There are two main problems with this approach. First, it never considers the quick transition mentioned above, whereby Italy shifted from the top to the bottom of the European league of economic performance in less than a decade. Second, during the years when the decline began and then worsened, many reforms did indeed have the effect of liberalizing the Italian economy to a great extent. Daveri and Jona-Lasinio (Reference Daveri and Jona-Lasinio2005), in their analytical work on the algebra of Italian decline, recognize that the productivity-enhancing effect of liberalizing reforms was puzzlingly modest (p. 407). I will now briefly review such liberalizations and make reference to their main international indicators, that is, their measurable results in terms of increased market efficiency.

The OECD (2011) ‘Integrated Product Market Indicator’ (PMR) encompasses 18 lower-level indicators on the manufacturing sector and the service sector related to (a) state control, (b) barriers to entrepreneurship, and (c) barriers to trade and investment. Italy has decreased the level of regulation in all the 18 sub-indicators so that the integrated PMR indicator decreased from 2.53 in 1998 (OECD average 2.12) to 1.32 in 2008 (OECD average 1.35). The PMR index referring to the Energy, Transport, and Communications sectors decreased from 5.7 in 1992 (OECD average 4.3), to 2 in 2007 (OECD average 1.9). The ‘Regulation Impact’ (RI) indicator measures the cost that anti-competitive regulation in non-manufacturing sectors impose on other sectors that use inputs from them. These costs were uniformly decreasing in Italy between 1990 and 2007, while being constant between 1975 and 1990. Between 1996 and 2008, even the professional services – which in Italy are known to be characterized by a strict closed-shop regime – show a clear liberalization trend (OECD, 2011).

In other words, market regulation in Italy went from strongly above, to in-line with, the OECD average, and this reduced market regulation had a direct effect on competition as well as a measurable effect on production costs (OECD, 2011).

Matching this metrics, in the same period, labor market flexibility also significantly increased, mainly thanks to the liberalization of temporary work. The employment protection legislation score collected by the OECD (a 0–6 metric scale) was down to 1.89 in 2007: only Denmark, Ireland, and the UK had a lower score among EU countries.

Matching an established global trend, union density levels (Visser, Reference Visser2013) have steadily declined since 1976, when they peaked at 50.5%, reaching 40% in 1987 and 33.4% in 2008 (29.2 if only the private sector is considered). Survey (not self-reported) data suggest a lower overall figure of 29%, and a mere 19% in the private sector (Baccaro and Pulignano, Reference Baccaro, Pulignano, Bamber, Lansbury, Wailes and Wright2009).

Furthermore: (a) between 1993 and 2003, Italy carried out the largest privatization plan in the OECD, selling assets equivalent to roughly 12% of GDP (Goldstein, Reference Goldstein2003); (b) the 1995 pension reform was assessed by international scholars as one of the most far-reaching in Europe in terms of expected savings (Baccaro, Reference Baccaro2002b); (c) new independent authorities were established over competition and telecommunication, among other sectors (Barca, Reference Barca2006).

In summary: during the period of economic decline, one cannot detect any increase in the monopolistic power of business or labor that could help explain such decline, or any increased market rigidity. On the contrary, many of the reforms approved since the 1990s had a clear and measurable liberalizing effect. Therefore, the hypothesis that causally links the decline of labor and total factor productivity growth to insufficient liberalization begs the question of identifying a benchmark that, according to this view, was not reached; in fact, it is unclear whether this benchmark can be identified. Indeed, the question is rather why, despite so many market-conforming reforms, comparative productivity decline became so strong that it was able to drag down total output.

Another, more recent, stream of literature, offers a different analysis based on post-Keynesian economics (Baccaro, Reference Baccaro2016; Baccaro and Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016, henceforth B/P). It identifies the decline of aggregate demand as the main driver of Italian economic decline. This explanation treats productivity as determined by investments which are in turn a function of aggregate demand (B/P, p. 183–184). While in post-war Europe (including Italy), aggregate demand was driven by real wage growth, since the 1990s in Italy, real wage decline was not compensated by household debt increase (as it happened in the UK through increased importance of the liberalized financial sector), nor by booming exports (as in Germany, through labor market dualization that kept industrial wages below productivity, reinforcing cost competitiveness). Italian membership of the Eurozone, which narrowed fiscal space and overvalued its currency, put the final nails in the coffin of decline.

The problem with this explanation is that the expected effect of the many reforms carried out in the 1990s was precisely aimed at an increased efficiency of the financial sector and increased competitiveness of the private sector. Therefore, while the ‘Growth Model’ approach clarifies that the macroeconomic conditions of Italy did not allow for sustained aggregate demand, it cannot, by design, discuss the reasons behind the failure of such large number of reforms to avert economic decline, though one of the mechanisms that instead allowed other European countries to do so.

The Italian political economy before the decline

Before discussing the effect of economic reforms in the 1990s, one must address a tension that characterizes previous VoC-based analysis of Italy. Hall and Soskice (Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001) grouped Italy along with other countries (France, Portugal, Spain, Greece, and Turkey) that deserve neither the label of LME, nor that of CME. Later studies labelled Italy as a Mixed Market Economy, that is, not endowed with institutions that can systematically support non-market forms of strategic coordination, but provided with tight labor regulations, and a coordinating role of the State in the provision of credit, both of which did not allow the unfettered deployment of market mechanisms either (Hancké et al., Reference Hancké, Rhodes, Thatcher, Hancké, Rhodes and Thatcher2007; Molina and Rhodes, Reference Molina, Rhodes, Hancké, Rhodes and Thatcher2007).

Later on, the coordination indices introduced by Hall and Gingerich (Reference Hall and Gingerich2009, henceforth H/G) contradicted earlier interpretations by placing Italy on the CME side of the spectrum, alongside countries such as Austria, Japan, Germany, and Norway. The H/G indicators depend on institutions (e.g., the level of wage coordination) and output (e.g., labor turnover) therefore capturing the ‘underlying’ prevalence of market vs. strategic coordination in each political economy. Such indicators detect a high level of strategic coordination in Italy despite its formally hybrid national institutional setting, which matches the good average economic performance of the Italian economy.

Other papers (e.g., Kenworthy, Reference Kenworthy2006) have contested the validity of H/G conclusions (which, they claim, are robust to the exclusion of Italy from the sample, H/G: p. 474). My interest here is, however, purely to discuss the correct interpretation of the Italian economy prior to the economic decline, not to assume that H/G conclusions are empirically solid. In other words: who is right? Was Italy a hybrid model or a coordinated model of capitalism?

This tension can be solved by observing that, until the early 1990s, strategic coordination was prevalent in the Italian economy but not supported by a coherent national institutional framework. Rather, the State and local institutions provided supplementary underpinnings to an imperfect institutional design.

According to most interpretations, the driver of economic growth in post-war Italy was to be found in large manufacturing industries until the early 1970s, and in small firms organized in industrial districts between then and the early 1990s (Salvati, Reference Salvati2000b; De Cecco, Reference De Cecco2007). Shortly after WWII, an incoherent institutional design was mitigated by the intervention of public powers.

Just like in the US, banks and non-financial firms were clearly separated by law. This was done so to prevent that the stability of the financial sector could be jeopardized by excessive exposure and control on non-financial activities. However, just like in Germany, banks were the main channel through which firms would access funding, while a marginal role was left to the stock market. […] Compared to the US, both the market and investment banks were absent. Minority shareholders could not have their interests defended through hostile takeovers. Compared to Germany, banks could not monitor investments from the inside. The public economic agent, IRI, was therefore supplying to the lacking of these institutions. It was given shares in companies formally private, both among industrial firms and among financial firms (Barca, Reference Barca1999: 10–11, my translation).

This institutional setting was created in the 1930s and remained unchanged until the 1990s. It included both LME-type and CME-type of institutions; however, strategic coordination was underpinned by the State's financial holding IRI, and by the publicly owned banking system.Footnote 1

On the side of labor, high unemployment – rather than social pacts – ensured moderate wage dynamics until the late 1960s (Barca, Reference Barca and Barca2010; Magnani, Reference Magnani and Barca2010). Later on, the labor code approved in 1970 was similar to those found in CME countries with a notable difference: the absence of co-decision practices (Barca, Reference Barca and Barca2010; Salvati, Reference Salvati2000a).

This imperfect design was unable to tame social unrest that erupted in the 1970s, when the fading coordinating capacity of IRI and other factors pushed, as early as the late 1970s, to decline of Italian large firms in sectors such as chemical, energy, and steel. Such decline of large firms accelerated then in the 1980s (Salvati, Reference Salvati2000a, Reference Salvati2000b; Rinaldi and Vasta, Reference Rinaldi and Vasta2012). An established literature documented the crisis of large firms in Italy. The origin of such decline was blamed on the inability of industrial and financial post-war elites to maintain their long-term coordination capacity over time, so that eventually special interests prevailed over collective interests (Barca, Reference Barca and Barca2010).

However, as thoroughly documented by Locke (Reference Locke1995), at the local and regional level, institutions were able to provide the sufficient supply of strategic coordination to support highly competitive and highly successful companies, even in advanced technological sectors. In short, as time progressed, Italy's economic fragmentation endured and increased: organizations and institutions in the so-called industrial districts co-existed with – declining – large firms (as well as less developed territories in the South). However, across the political economy and by means of different arrangements rather than nation-wide homogeneous institutions, strategic coordination rather than market coordination remained the norm.

Industrial districts are clusters of small firms operating in a given territory and producing a single class of goods. In the early 1970s, firms with <50 employees made up 42% of the total manufacturing workforce. In the early 1990s, this number increased to 57.8%, in stark contrast to economies such as in Germany (21.7%), the UK (22.8%) or the US (36.5%). In the same period, employment in large firms (with more than 499 workers) dropped from 24 to 13% (Brusco and Paba, Reference Brusco, Paba and Barca2010).

The emergence and growth of such districts were considered a consequence of coordinated work by different types of local institutions including public authorities, chambers of commerce, trade unions, cooperative and rural banks, and so on (Pyke et al., Reference Pyke, Becattini and Sengenberger1990; Sengenberger and Pyke, Reference Sengenberger and Pyke1992). Quantitative studies have shown that labor costs in small firms operating within industrial districts were consistently higher than in comparable small firms operating outside a ‘district’ framework (Signorini, Reference Signorini1994). However, labor productivity and return on investment were higher as well, allowing for a dramatic increase in exports (Paniccia, Reference Paniccia1998; Becattini and Ottati, Reference Becattini and Ottati2006).

The financing of firms was based on informational logic: local banks would possess privileged knowledge on both the investment plans and the firms, and allocated credit accordingly. Labor relations were also extremely cooperative. Previous literature argued that, at the firm level, in the districts or more generally at the territorial level, unions were often able to develop micro-type of concertation because they were far detached from political cleavages that made concertation impossible at the national level (Regalia, Reference Regalia and Andreoni2010: pp. 4–5). In other words, lacking a coherent set of national institutions, local-level arrangements were put in place to support systematic strategic coordination.

To sum up this short review, previous literature identified two phases of Italian economic development in the period characterized by sustained growth. The first was driven by large firms, the second by small firms organized in districts. However, strategic coordination similar to that characterizing fully-fledged CMEs was prevalent across the Italian economy in both large and small firms. Coordination was not underpinned by a coherent set of national institutions but stemmed from the post-war settlement based on State agency at the national level, and, later on, from local-level arrangements in the districts.

This interpretation reconciles previous interpretations of the Italian political economy, apparently diverging between those who emphasized the imperfect institutional design of Italy (e.g., Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001), and works that treat Italy almost unambiguously as a CME (H/G 2009; also, Thelen, Reference Thelen, Hall and Soskice2001 in the original VoC volume, groups Italian industrial relations with other coordinated economies).

An objection to the interpretation that I am advancing here could come from those who distinguish between institutional coherence and institutional complementarity (Crouch, Reference Crouch2005; Höpner, Reference Höpner2005). Such authors suggest that multiple configurations can deliver good economic performance, so that one should focus on complementarities as such, and discard the categorization of LME vs. CME coherence. My interpretation of the Italian case only partially caters to this argument. Indeed, I have underlined that institutional complementarities of post-war Italy departed from the standard CME institutional set, but at the same time, they crucially underpinned CME-type of coordination. Without reference to the dichotomy that differentiates between market-based and strategic coordination as crucially different logics in economic problem-solving, any discussion on the interplay between different type of institutions would risk of ending in tautology, with economic growth associated by definition to positive complementarities.

Instead, the analysis of the Italian case shows that more than one set of institutions can be supportive of strategic coordination among economic agents. This of course deviates from the standard VoC interpretation. It implies that, possibly, different sets of institutions can, in different countries, also support market coordination. Indeed, without an understanding of what type of coordination logic is supported by institutional complementarities, the existence (or lack of) of such complementarities would not be a testable statement for empirical analysis. I will introduce the latter in the following paragraph.

Institutional change in Italy

The list of economic reforms approved in Italy since the early 1990s is extensive. For the purpose of identifying the effect that these reforms had on the model of capitalism, that is, on the prevalent mode of coordination among economic actors, I will focus separately on the spheres of corporate governance (including finance) and labor, and then discuss their effects.

Capital and corporations, running to stand still

The financial system and corporate governance laws are strictly intertwined in the VoC framework. A bank-based system of finance finds its optimal complement in laws that do not favor hostile takeovers and therefore underpin stable, concentrated ownership. In CMEs, banks have the task of monitoring investment, often by sitting in companies’ boards. The resulting ‘patient’ capital is provided on the basis of direct knowledge of industrial strategies. As a consequence, the stock market is typically underdeveloped in CMEs because even listed firms seek funds from loans, not from equities. The reverse logic applies to LMEs. Banks are prevented by law to own shares of non-financial firms, and minority shareholders rights are strongly protected. As a consequence, ownership is diffused through highly developed stock markets. In this setting, managers have to maximize share values, or otherwise brace themselves for a hostile takeover (Goyer, Reference Goyer2011).

I have reviewed earlier the features of Italian regulations in this domain: a bank-based State-owned system impaired by the inability of banks to own shares in non-financial firms. Large-scale allocation of credit was authoritative and driven by political logic. At the local level, credit for small and medium enterprises was based on information and reputation. Corporate laws were somehow consistent with a closed and highly coordinated system of finance. Minority shareholders were nearly non-existent, ownership was therefore extremely concentrated and the stock market underdeveloped (Deeg, Reference Deeg, Streeck and Thelen2005).

Reforms in this sector started in 1990 and 1993 when two banking laws were passed that liberalized the banking sector and paved the way for a large wave of privatization, mergers, and acquisitions. In roughly 10 years, public ownership of banks was reduced from 70 to 10%; if only listed banks are considered, the share of public ownership was down to zero and the number of institutions nearly halved, from 44 to 27 (Szego et al., Reference Szego, De Vincenzo and Marano2008). The overall consolidation process – including non-listed banks – was staggering: over 620 M&As, involving over half of the total banking assets, occurred between 1990 and 2004, and consequently the number of banks decreased by over one-fourth. This consolidation matched a broader pattern of liberalization whereby mandatory specialization disappeared and, under the universal banking model, financial institutions could raise funds freely and undertake any business activity, including different types of lending and merchant bank activity (Fiorentino et al., Reference Fiorentino, De Vincenzo, Heid, Karmann and Koetter2009).

The problem is: while these reforms can be understood as pushing the banking system toward a more liberal model, other reforms were going in the opposite direction. In fact, the 1993 law also allowed banks to acquire shares of non-financial firms, which is a core feature of coordinated models. Indeed, in liberal systems, banks are mediators between capital holders and borrowers, and keep at arms-length with the latter. In LMEs, banking risk is hedged not by relying on privileged information, but through diversification and publicly available information on performance (Deeg, Reference Deeg, Streeck and Thelen2005; Goyer, Reference Goyer2011).

In sum, while before the 1990s, the system was strategically coordinated, after the reforms, ‘the Italian banks seem to be trying to follow both the logic of voice [prevalent in CMEs] and logic of exit [prevalent in LMEs] simultaneously. But these logics are opposed’ (Deeg, Reference Deeg, Streeck and Thelen2005: 191, text in parentheses added).

Hybridization is even more apparent if reforms of the banking sector are observed together with the two reforms of corporate governance approved in 1998 and 2003: the first applied to listed firms, the second to all companies. While the (1) ‘German’ model of banking was adopted, allowing banks to own non-financial firms, the (2) code for listed firms followed the Anglo-Saxon model and the (3) reform of governance structures, instead, explicitly refused to follow a model.

The broad aim of the 1998 reform of corporate governance was to increase competition in Italian capitalism through the reduction of ownership concentration (Bortolotti and Siniscalco, Reference Bortolotti and Siniscalco2001). In fact, Italian firms are often organized in pyramidal structures, whereby owning 50.1% of a single firm can grant controlling rights to a constellation of companies. Therefore, increasing minority shareholder rights seemed a good idea to countervail such concentration, except it was being combined with banking regulations pushing in the opposite direction (Bianchi et al., Reference Bianchi, Bianco, Enriques, Barca and Becht2003). LaPorta et al. have measured an index of minority shareholder power based on six dimensions (La Porta et al., Reference La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer1999). After the 1998 reform, Italy's score passed from 1 to 4 (6 being the maximum); that is from the same score as Germany, to the score of the US and the UK (Bortolotti and Siniscalco, Reference Bortolotti and Siniscalco2001).

In 2003, the icing on the cake of incoherent reforms was indeed another one which gave each company the possibility to choose its preferred organizational statute, which could either follow the traditional Italian model, the Anglo-Saxon model, or the German model (Ghezzi and Malberti, Reference Ghezzi and Malberti2008). This reform epitomizes how Italian policymakers have ‘chosen not to choose’ among different corporate governance setups, without awareness of the interactive consequence that the latter have with the financial system on the one hand, and on the rest of the political economic institutions on the other hand.

The fragmentation of Italian labor market

Labor market institutions are the second main pillar of production systems. Symmetrically to what I have discussed above, institutions that support incomplete contracting, implicit exchanges, and other long-term arrangements underpin strategic coordination. Liberal institutions instead underpin an arms-length, hierarchical, market logic based on demand, supply, and relative prices. Hence, CMEs are characterized by long job tenure, favored by high(er) employment protection legislation. The latter insures employers against the risks of losing their investments in training, and insures employees against the risk of losing their jobs while endowed with hardly transferrable specific skills. Wages are strongly coordinated, with a prevalence of the higher bargaining levels (national or sectoral) to the local level. This prevents the emergence of high wage differentials, and reinforces incentives to long job tenures and to acquire productivity-enhancing specific skills.

The logic of complementarities is the opposite in LMEs, where workers have a low level of employment protection (and a higher level of unemployment protection) hence invest in transferrable general skills. Labor can be reallocated swiftly depending on companies’ short-term profitability. Wages are bargained either individually by the single worker, or locally at the firm level. Wage differentials depend on the marginal productivity of each worker, or reflect cyclical performances of firms. As a consequence, in LMEs, average job tenure is shorter (Estevez-Abe et al., Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001).

Large-scale institutional change in the labor market in Italy started in the early 1990s through a number of social pacts between governments, unions, and employers (Salvati, Reference Salvati2000a). Social pacts were a complete novelty in Italian polity. They aimed at imposing a new discipline on wage negotiation in order to turn the just-approved currency devaluation into a real devaluation (Baccaro, Reference Baccaro2002a).

To this purpose, in 1992–93 coordinated wage setting was established. Wage increases negotiated at the sectoral level would be based on a nationally-negotiated planned inflation rate, while still allowing for firm-level additional bargaining. As a result of this reform, the index for the level of wage bargaining increased from 2 to 3 (on a scale from 1 to 4), mirroring the increased importance of the national and sectoral-level bargaining (Visser, Reference Visser2013). Data already quoted from a survey run by the Bank of Italy on 2901 firms in the manufacturing sector report that during the 2000s, 30.6% of firms with more than 20 employees reached a company agreement, down from 43.4% in the 1990s (Banca d'Italia, 2009). Also, the wage coordination index collected by Visser (Reference Visser2013), which measures the extent to which wages move similarly across sectors and firms, increased from 2 to 4 (on a scale from 1 to 5) indicating that central organizations of labor and business negotiate national guidelines that are then observed across sectors through the institutionalization of sector and firm bargaining, respectively. In summary, with regards to wage determination, these reforms moved Italy much closer to the CME side of the spectrum, establishing institutions that should promote long-term strategies for firms, and the acquisition of specific rather than general skills.

The 1996 reform of the labor code (approved by the center-left with the agreement of trade unions) went in the opposite direction, while leaving the bargaining logic of the above reforms in place. Flexibility was increased by deregulating short-term appointments, agency work, and other types of the so-called ‘atypical’ working arrangements. Compared to the traditional open-ended jobs, such ‘atypical’ working arrangement included more lax regulation on hiring and firing, and also entailed severely reduced welfare entitlements and unemployment protection. A subsequent reform in 2001, approved by a center-right coalition, deepened the cleavage between insider workers and ‘atypical’ workers, further deregulating flexi-contracts. As a consequence of this reform, which increased flexibility at the margins while keeping intact the core regulations for insider workers, the EPL indicator collected by the OECD declined from 3.57 in 1992 to 1.89 in 2007. Italy moved from having a stricter EPL than Germany, France, Austria, or Belgium, to having a weaker EPL than any of these countries and (among EU15 countries), and a score higher than only Denmark, Ireland, and the UK. As a consequence, labor turnover increased: between 1992 and 2007, the share of employees that had been in the same job for <1 year nearly doubled, from 6.3 to 12.3% of the Italian total employment.

In sum, similarly to what I have observed in the corporate governance/finance realm, reforms of the labor market have also had deeply contradictory elements. New wage setting institutions increased coordination of the Italian labor market, while changes in labor laws pushed toward a more flexible system.

The effect of incoherent reforms

Effect on capital markets and corporate governance

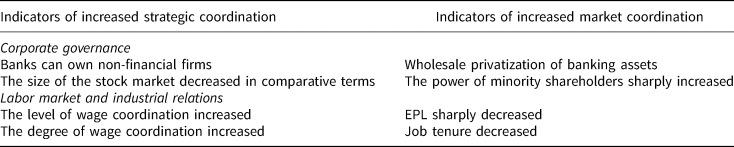

Table 3 summarizes the main changes reviewed in the previous sections. In corporate governance, liberalizing reforms such as privatizations and increasing rights for shareholders were matched with a move toward more coordinated capital by allowing banks to own non-financial assets.

Table 3. Mapping institutional change in Italy ca. 1990–2007

The reforms of the financial system add an impact on two dimensions of the Italian strategic coordination capacity. First, the coordinating role of the State dissolved as a consequence of the nearly complete privatization of the banking system and increased international competition. This reduced the availability of patient capital to large enterprises based on informational logic and strategic coordination.

Second, mergers and acquisitions reduced the availability of capital for small- and medium-sized enterprises. Data from the Bank of Italy show that between 1990 and the financial crisis, three periods of credit scarcity for Italian firms took place, each of them with significant impact on their investment: 1992–93, 1995–96, and 2000–03 (Gaiotti, Reference Gaiotti2011). During these periods, up to 17% of the sampled companies could not access the credit they needed, with measurable impact on their investment capacity (Gaiotti, Reference Gaiotti2011). While these data do not link institutional change explicitly to credit availability, it clearly shows that credit availability to firms did not improve as a consequence of the convergence to and membership of the Eurozone (Gaiotti, Reference Gaiotti2011: Table 1, page 29).

In addition, several quantitative studies exploring different dimensions of the relation between M&A and credit availability to SMEs point to the conclusion that SMEs – the main protagonists of Italian economic growth between 1970s and 1980s – suffered the most. Sapienza (Reference Sapienza2002) bases her analysis on loan contracts of 50,000 Italian companies and 80% of total bank lending between 1989 and 1995. She evaluates the impact of M&A on the cost and availability of credit. Two of her results are of interest to this paper: first, credit availability deteriorates sharply for companies that were borrowing from local banks with large local market share (i.e., higher than 6.5%) that were targeted and acquired by a larger ‘outsider’ bank. This effect clearly had a negative impact on credit in districts where local banks played an important role. Second, following M&A activity, banks reduced lending to small borrowers irrespectively of ‘observable characteristics of the borrowers. This evidence supports the view that large and small banks have different loan strategies’ (Sapienza, Reference Sapienza2002: 365). This effect also negatively affected SMEs credit availability.

Similar results are reached by Bonaccorsi and Gobbi (Reference Bonaccorsi di Patti and Gobbi2007). Here the authors analyze a sample of corporate borrowers between 1990 and 1999 and observe that, following a merger or acquisition, corporate borrowers of the acquired bank experience a severe credit shock for 3 years after the merger. Their credit availability is reduced between 8 and 10%, reaching 100% in case of relationship termination.

Perhaps even more interestingly to our purposes, Alessandrini et al. (Reference Alessandrini, Presbitero and Zazzaro2010) focus on a side effect of M&A, that is, the end of local banking. Based on micro-data between 1995 and 2003, their result suggests that the increased physical distance of banks headquarters from the territory in which SMEs operated has reduced the supply of loans for innovation purposes: in other words, the closer the decision-making to the firm, the higher the credit availability for innovation.

Arguably, this negative credit shock for SMEs which was an unintended side effect of the transformation of the banking system documented above occurred in the wrong moment, that is, exactly when the processes of market internationalization were increasing the need of innovation for SMEs. Additionally, the reduced availability of credit from banks was not offset by an increased recourse to the stock exchange. In 2007, capitalization of the Italian stock market was the lowest in Western Europe, equivalent to circa 50% of GDP, markedly inferior to bank-based countries such as Germany (64%) or Austria (60%).Footnote 2 In short: rather than transitioning from a bank-based model to a new market-oriented financial model, Italy was stuck in the middle.

Indeed: while banks were privatized and liberalized, the 1993 reform allowed them to acquire shares of non-financial firms. Unsurprisingly, they increasingly did so, playing an important role as owners of newly privatized, formerly State-owned, enterprises (e.g., telecoms, highways, and airlines). This contradicted the efforts to push toward a liberal system pursued by reforms of the corporate governance code because, as recalled earlier, in LMEs banks do not hold equities of borrowers (Goyer, Reference Goyer2011). In fact, in Italy, banks did not limit themselves to enter in privatized firms: while I could not find time-series data, data from 2013 show that banks own shares from at least 10% of non-financial companies listed in the stock exchange.Footnote 3 However, the incoherent institutional setting did not allow the emergence of a coordinated-type of corporate governance. This is shown by Barucci and Mattesini (Reference Barucci and Mattesini2008) that use a dataset including 190 large companies (listed and not listed) between 1994 and 2000. They investigate the reasons why banks have acquired shares of non-financial companies through multivariate regression analysis. Their conclusions are revealing of the consequences of a system with mixed incentives: ‘Italian banks tend to invest in firms that have a credit relationship with them (…). There is little support, in the data, for the existence of a virtuous bank-non-financial company shareholding relation associated with governance/monitoring arguments. (…) We have not observed a significant move of the Italian banking system toward a more active involvement in the management of firms, to improve their governance or to overcome informational asymmetries, i.e., the factors that were considered, especially in the literature of the early 1990s, as the major advantage of the main bank systems of Germany’ (2008: p. 2247).

The resulting output of this incoherent set of reforms is an increasingly closed capitalism. Culpepper (Reference Culpepper2007) summarizes aptly: ‘Italy was in 1995, and remains in 2007, a system in which a small number of shareholders continues to exercise control over most of the companies listed on the stock exchange’ (see also: Giacomelli and Trento, Reference Giacomelli and Trento2005).

In other words, lacking a coherent framework, the Anglo-Saxon-like reform of corporate governance had no consequences on the distribution of ownership. In fact, pyramidal structures and cross-shareholding are also more pronounced than before. As argued by Giacomelli and Trento (Reference Giacomelli and Trento2005), the layering of different reforms, as opposed to a coherent comprehensive strategy, has pushed owners to defend control against takeovers through all available means, while not increasing incentives to develop a market for firm ownership.

Effect on labor markets

In the labor market, reform schizophrenia had similar dysfunctional effects. On the one hand, industrial relations became more coordinated: comparative datasets detect that wage bargaining in Italy at the end of the first decade of the 2000s was both more coordinated and negotiated at a higher (national) level than it was in the late 1980s. However, these coordination practices relate to a decreasing portion of the labor force because, due to reforms of the labor codes, the majority of new hires since the late 1990s are employed in flexible regimes with reduced income and job protection, that is, without the features that combine well with other institutions of a CME.

According to the Italian statistical office, since the late 1990s, the majority of newly employed persons were hired through an ‘atypical’ contractual arrangement. In 2011, 78% of new hires were ‘atypical’. In 2008, these workers made up 27% of total employees (ISTAT, 2002:178, 2009). In other words, the timing of entering the labor market became the main predictor of the occupational status with younger cohorts being overwhelmingly employed through ‘atypical’ jobs. As a consequence, in Italy, the cleavage between insiders and flexible workers overlapped with a generational cleavage. Hence, the Italian type of labor market dualization cuts across occupations, sectors, and firms: labor laws therefore do not support a clear set of incentives, and the expected premium from either general or specific skill became uncertain.Footnote 4 The distortion of incentives is reinforced by trends in wages and income. In fact, the occupational status (standard vs. ‘atypical’) is also a strong predictor of economic gains.

‘Atypical’ workers, between 1998 and 2004, enjoyed salaries 20% lower than regular employees, even controlling for a host of socio-economic variables including education and job type (Leombruni and Taddei, Reference Leombruni and Taddei2009). The generational dimension of this rift appears from income studies: between 1991 and 2007 (i.e., before the financial crisis – though the difference grew stronger after it), real income of those aged between 19 and 34 (35 and 44) remained constant (increased by <5%) while it increased by over 25% for those aged between 55 and 64 (Banca d'Italia, 2010).

Given the presence of a negative wage premium based on the occupational status (and age) rather than performance, or education, the Italian type of labor flexibility both undermined incentives toward the acquisition (and within-firm development) of specific skills for the newly hired workers, while also failed to incentivize toward the acquisition of general skills. Data on university enrolment support this interpretation. Starting with 2003 (is 6 years after the main labor reform was approved and 10 years after the first reform of the wage bargaining institution), university enrolment started to decrease. Between 2003 and 2010, the number of first-year university students was down by 24%. In the same period, the number of high-school graduates (i.e., those who are entitled by Italian law to enroll in the university) constantly increased.Footnote 5

Failure of generating incentives which are typical of LMEs pair with the fact that incentives derived from strategic coordination are also undercut by flexibilization at the margins. Saltari and Travaglini (Reference Saltari and Travaglini2006, S/T) show that if firms employ a flexible workforce in order to pursue a cost-cutting strategy, this could theoretically explain productivity slowdown in Italy. Indeed, S/T's argument is even more plausible if flexibilizaiton is considered in a context of dualization, that is, when other strategies become unfeasible given the contradictory set of incentives that operate simultaneously.

In sum, the examination of institutional change in Italy confirms that economic decline since the mid-1990s has followed the hybridization of its capitalism. The latter moved from a model in which the State and local-level institutions provided support to strategic coordination, to a hybrid model in which opposite logics operate at the same time, and therefore economic agents are provided with contradictory incentives.

Discussion: hybridizing reforms and economic decline

Changes in the corporate governance/finance domain discussed above have reduced both the supply of strategic, patient, capital to large corporations and the availability of capital to small and medium companies. At the same time, labor market changes have reduced incentives to skill formation and negatively influenced labor productivity through cost-cutting strategies. Each of these factors, and a fortiori, their combination, would generate an expectation of reduced innovation capacity of the Italian economy. Indeed, this is what existing literature does report, as discussed earlier in this paper (Ciocca, Reference Ciocca2003; Castellani and Zanfei, Reference Castellani and Zanfei2004; Boeri et al., Reference Boeri, Faini, Ichino, Pisauro and Scarpa2005; Daveri and Jona-Lasinio, Reference Daveri and Jona-Lasinio2005; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Lotti and Mairesse2007). Compared to standard explanations lamenting the lack of market-conforming reforms, I argue that the innovation/productivity decline in Italy was driven by an incoherent mix of policies that wiped out previous institutional complementarities, while being unable to create new ones.

This explanation, empirically robust and theoretically informed, has two advantages compared to conventional approaches that lament decline as a consequence of insufficient liberalizing ‘structural reforms’: first, it is able to explain why Italy rapidly passed from being amongst the best European economic performers, to being the worst: the negative credit shock to SMEs was followed by longer-term adverse incentives in both the financial market and the labor market. This sequence matches the rapid fortune reversal of Italian productivity trend and its worsening over time. Second, it explains why the large amount of reforms carried out in the 1990s and 2000s, and the increase in market-conformity traced by international indicators reported early on in this paper, did not have the effect of improving the state of Italian economy as conventional economic theory would predict.

My explanation, instead, dovetails interpretations focusing on the decline of aggregate demand recalled earlier (Baccaro, Reference Baccaro2016; Baccaro and Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016). Indeed, innovation/productivity decline motivated by incoherent reforms added to negative (for Italy) demand-side shock driven by the continental macroeconomic setting explored in these works. Additionally, the effects of incoherent reforms on productivity that I described in the previous section help explain why the institutional change that happened elsewhere with strong macroeconomic effect – liberalized financialization in the UK; cost-competitive industrial production in Germany; high-innovation high-wage industry in Sweden – could not materialize in Italy.

Conclusions

This paper offered a new interpretation of Italian economic decline which combines empirical and theoretical insights. It performed a novel test to one of the key expectations of the VoC literature: the purer the model of capitalism, that is, the more coherent the institutional setup toward supporting a strategic or market-based mode of coordination among economic actors, the stronger the economic performance. It did so with reference to within-country variation over time, and with reference to the critical case of an advanced industrialized country that underwent a clear trend of economic decline since the early 1990s: Italy. In this period, Italy was the worst economic performer among developed countries. Beside the empirical interest for the enquiry, Italy is a critical case to test the VoC hypothesis because its model of capitalism was deeply reformed at the time when its economic decline commenced. Additionally, through the test of the VoC hypothesis, this paper also addressed the following empirical puzzle: why many economic reforms, which were positively regarded by international observers, delivered such a dismal economic effect?

The paper found that the institutional reforms have hybridized the Italian model of capitalism. On the one hand, reforms have destroyed previous patterns of strategic coordination supported by State actors and local institutions. On the other hand, reforms have pushed toward increased strategic and market coordination at the same time, within each of the key institutional spheres of labor and corporate governance (including finance). This hybridization resulted in a decreased innovation capacity and overall economic performance.

While supporting one of the key tenets of the VoC approach, this paper also departs from VoC significantly, in a direction that suggests the need for further research. Indeed, the VoC approach treats LMEs and CMEs as institutional self-reinforcing equilibria toward which countries tend to converge, as epitomized by the interpretation of reforms in the UK during the Thatcher years (King and Wood, Reference King, Wood, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999, see also Thelen, Reference Thelen2014 on a similar line). However, the analysis of Italy shows that even though strategic coordination prevailed in the economy, leading to good economic results until the 1990s, actors such as the employers’ organization, the financial elites and even the trade unions, all as mediated by the political elites, did not push to reinforce complementarities supporting strategic coordination. Instead, as reported above, an incoherent set of reformed emerged.

The ‘growth model’ approach discussed earlier focuses on distributive issues as a key to understand macroeconomic choices of countries. Perhaps another line of enquiry should bring power struggle back in to understand the determinants of institutional changes of the supply side.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank for comments Lucio Baccaro, Pepper Culpepper, Bob Hancké, Anke Hassel, Jonathan Hopkin, Ugo Pagano, Waltraud Schelkle, and two anonymous referees. Outstanding research assistantship by Alessandro Giovannini is gratefully acknowledged. All errors are mine.

Financial support

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.