Introduction

Approximately 30 per cent of older adults (i.e., ≥ 65 years of age) living in the community fall at least once each year (Pearson, St-Arnaud, & Geran, Reference Pearson, St-Arnaud and Geran2014). Falls are associated with morbidity and mortality, are linked to poorer overall health, and can lead to earlier admission to long-term care facilities (Ambrose, Cruz, & Paul, Reference Ambrose, Cruz and Paul2015; Ambrose, Paul, & Hausdorff, Reference Ambrose, Paul and Hausdorff2013; American Geriatrics Society & British Geriatrics Society, 2011; Brown, Reference Brown1999; Rubenstein, Reference Rubenstein2006; Rubenstein & Josephson, Reference Rubenstein and Josephson2002). Older adults living in the community are also nutritionally vulnerable, with 34 per cent at nutrition risk (Ramage-Morin & Garriguet, Reference Ramage-Morin and Garriguet2013). Nutrition risk is associated with: level of disability, poor oral health, medication use, living alone, depression, not driving regularly, low social support and infrequent social participation (Ramage-Morin & Garriguet, Reference Ramage-Morin and Garriguet2013). Nutrition and falls risk are associated and often co-occur; poor diet quality can perpetuate muscle mass and strength loss, which can lead to frailty and potentially a fall (Boulos, Salameh, & Barberger-Gateau, Reference Boulos, Salameh and Barberger-Gateau2016; Chien & Guo, Reference Chien and Guo2014; Lorenzo-López et al., Reference Lorenzo-López, Maseda, Labra, Regueiro-Folgueira, Rodríguez-Villamil and Millán-Calenti2017; Vivanti, McDonald, Palmer, & Sinnott, Reference Vivanti, McDonald, Palmer and Sinnott2009; Westergren, Hagell, & Sjödahl Hammarlund, Reference Westergren, Hagell and Sjödahl Hammarlund2014). Those with a history of falls typically have more nutrition risk than those who have not fallen (Johnson, Reference Johnson2003; Meijers et al., Reference Meijers, Halfens, Neyens, Luiking, Verlaan and Schols2012; Vivanti et al., Reference Vivanti, McDonald, Palmer and Sinnott2009). Based on this overlap, connecting falls and nutrition prevention initiatives is encouraged, and falls prevention programs recommend nutrition screening (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario & Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2013).

Many studies have explored the effectiveness and implementation of falls screening and prevention programs (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Tan, Ning, Li, Gao and Wu2018; Guirguis-Blake, Michael, Perdue, Coppola, & Beil, Reference Guirguis-Blake, Michael, Perdue, Coppola and Beil2018; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Thomas, Veroniki, Hamid, Cogo and Strifler2017), and have used the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework (Shubert, Altpeter, & Busby-Whitehead, Reference Shubert, Altpeter and Busby-Whitehead2011) or the Kotter model of change management (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Parker, Winkler, Liu, Lambert and Eckstrom2016). Despite the importance of nutrition to falls risk and inclusion of determination of nutritional status in a multifactorial evaluation of a variety of risk factors (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario & Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2013), few studies have explored how to add nutrition screening to falls risk screening programs. Examining the perspective of those implementing the program in primary care, and understanding the challenges and strategies they employed to implement nutrition risk screening, could support others to include nutrition screening in their falls risk programs.

At the time of this study in Ontario, 14 Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs) were responsible for planning, integrating, and funding health care services (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2018). The North East (NE) LHIN was one of the largest geographically, including 44 per cent of Ontario’s land mass, yet only 4.1 per cent of Ontario’s population (North East Local Health Integration Network, 2018). The proportion of the population ≥ 65 years of age in this catchment area is projected to increase from 19 per cent to 30 per cent by 2036, and rates of heavy drinking, smoking, obesity, and chronic disease, including diabetes, are higher than the provincial average (North East Local Health Integration Network, 2018).

A family health team (FHT) is a primary health care provider with an interprofessional team approach to providing care (Rosser, Colwill, Kasperski, & Wilson, Reference Rosser, Colwill, Kasperski and Wilson2011). The size and composition of each FHT varies and may include family physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, dietitians, occupational therapists, and other health professionals (Rosser et al., Reference Rosser, Colwill, Kasperski and Wilson2011). There are more than 3,000,000 people enrolled in FHTs in more than 200 communities across Ontario. The NE LHIN had 27 FHTs, each with an executive director (ED) (North East Local Health Integration Network, 2018).

In 2015, the NE LHIN launched the Stay on Your Feet (SOYF) strategy, which supports the aging population in Northern Ontario to stay healthy and live independently for as long as possible. The strategy is a population-based comprehensive approach to preventing falls by reducing the modifiable risk factors that lead to falls (Kempton et al., Reference Kempton, Garner, Van Beurden, Sladden, McPhee and Steiner1997; North East Local Health Integration Network, 2018; Van Beurden, Kempton, Sladden, & Garner, Reference Van Beurden, Kempton, Sladden and Garner1998). SOYF follows the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, with a focus on building awareness and skills among older adults and care providers, shifting health care processes to incorporate prevention, and developing supportive public policies by engaging multiple partners (Bedard, Reference Bedard2017; Van Beurden et al., Reference Van Beurden, Kempton, Sladden and Garner1998). The SOYF strategy promotes the use of the Staying Independent Checklist, a falls risk screening tool (Rubenstein, Vivrette, Harker, Stevens, & Kramer, Reference Rubenstein, Vivrette, Harker, Stevens and Kramer2011; Stay On Your Feet, 2018), and provision of exercise programs designed for older adults (North East Local Health Integration Network, 2018). Funding from Improving & Driving Excellence Across Sectors (IDEAS), a province-wide initiative offered through the University of Toronto, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, and Health Quality Ontario (Bedard, Reference Bedard2017; Government of Ontario, 2018), provided electronic tablets for falls screening pilot sites along with a 1 year subscription to the Ocean platform, which the FHTs could decide to renew. Ocean, by CognisantMD (2018), is a system that facilitates use of secure client forms, screening tools, and surveys that can be completed by the client. Results are integrated directly into the electronic medical record (EMR). In 2017, with the increasing evidence and recognition of the connection between falls and nutrition risk, a nutrition screening tool, Seniors in the Community Risk Evaluation for Eating and Nutrition-II-Abreviated (SCREEN II-AB) was added to the Ocean tablets. The aim of this study was to describe and understand how FHTs added nutrition risk screening to a falls risk screening program that included the integration of screening into routine practice and the facilitation of follow-up for at-risk clients. Results provide direction on how to connect falls and nutrition risk screening in primary care.

Methods

To further explore the process for setting up falls and nutrition screening within North East Ontario, six FHTs were selected to participate in this qualitative study. Perspectives of FHT staff, management, clients, and regional representatives were provided through in-depth interviews.

Falls and Nutrition Risk Screening

In the falls risk screening program, the 12-question Staying Independent Checklist was used, as it is recommended by SOYF and has been validated against clinical evaluation (Bedard, Reference Bedard2017; Rubenstein et al., Reference Rubenstein, Vivrette, Harker, Stevens and Kramer2011). Some sites used two-part screening, initially asking about a history of falls, feeling unsteady, and being worried about falling, with an answer of “yes” to any of these three questions leading to use of the full checklist or referral to a falls risk assessment. Other sites began with the checklist and referred based on the scoring (Bedard, Reference Bedard2017). The follow-up included a multifactorial falls assessment, which varied by site and profession completing the assessment (typically a nurse or occupational therapist). Following some success with building the falls risk screening into the routine of pilot FHTs (Bedard, Reference Bedard2017), the next step was to incorporate nutrition risk screening. SCREEN II-AB was selected because it is brief (8 items), self-administered, and the preferred tool for determining nutrition risk in community-living older adults (Keller, Goy, & Kane, Reference Keller, Goy and Kane2005; Keller & Østbye, Reference Keller and Østbye2003; Keller, Østbye, & Goy, Reference Keller, Østbye and Goy2004; Power et al., Reference Power, Mullally, Gibney, Clarke, Visser and Volkert2018). Both screening tools were embedded in the Ocean system with SCREEN II-AB use starting in 2018. As a follow-up to nutrition risk screening, a customized handout with suggestions for improvement based on individual responses was developed by a SOYF working group. The handout was provided automatically to the clients after completing the nutrition screening on the Ocean tablet. In addition to this handout, FHTs had to plan how those at risk would be treated. To follow ethical screening, treatment or services such as access to a trained professional (e.g. dietitian, occupational therapist), must be available for those at risk (Keller, Brockest, & Haresign, Reference Keller, Brockest and Haresign2006; Kondrup, Allison, Elia, Vellas, & Plauth, Reference Kondrup, Allison, Elia, Vellas and Plauth2013; Wilson & Junglier, Reference Wilson and Junglier1968). Screening with provision of subsequent services or referrals is described here as a screening program (Keller et al., Reference Keller, Brockest and Haresign2006).

Development of Interview Guides

Interviews were conducted with FHT staff, management, regional representatives, and clients. The semistructured interview guides explored how sites developed and implemented the falls risk screening program, how they added nutrition risk screening, and if/how they were informed by implementation frameworks or theories. The guide followed frameworks focused on the implementation process (Laur, Valaitis, Bell, & Keller, Reference Laur, Valaitis, Bell and Keller2017) and behaviour change (Michie, van Stralen, & West, Reference Michie, Stralen and West2011) with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research used as an overall guide (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009). Questions specific to teamwork were informed by the work of Salas and colleagues (Salas, Shuffler, Thayer, Bedwell, & Lazzara, Reference Salas, Shuffler, Thayer, Bedwell and Lazzara2015; Salas, Sims, & Burke, Reference Salas, Sims and Burke2005).

The interview guide was reviewed by two FHT staff, one researcher and one regional representative. The first interview was used as a pilot, and minor modifications were made to the guide before finalization (Table 1), including the addition of questions on the specific auditing practices used by the FHTs. Five of the six FHTs were involved in the initial falls screening pilot, with the sixth starting a short time later. Several sites had not maintained the initial falls screening and were restarting, or an original team was piloting falls and nutrition screening in a new site.

Table 1: Interview guides for the FHT staff/management, regional representatives and FHT client participants

Note. Questions were designed for FHTs that had started falls risk screening in the initial pilot, and were now adding nutrition risk screening. Questions were adapted for FHTs that were implementing falls and nutrition risk screening together. FHT = family health team; LHIN = local health integration network.

Sampling and Recruitment

In early 2018, six FHT sites were selected by the primary care workgroup of the SOYF strategy to be participant sites. Eligibility included: previous participation in the falls risk screening pilot, interest in including nutrition risk screening in the falls screening process, using a tablet for screening, having at least one subscription to Ocean, and having access to a dietitian.

Two to five staff or management involved with the screening program were interviewed per site; clients were recruited from three sites. Regional representatives were recruited based on their familiarity with the SOYF initiative. A site representative (ED, dietitian, or receptionist) facilitated recruitment with staff and clients. Purposive sampling was used to elicit valuable insights, both positive and negative. Snowball sampling was used when key contacts were identified during a site visit or interview. Some individuals declined participation because of lack of time or permission to participate; because of the recruitment strategy, the number of people who declined is unknown.

Data Collection

All interviews (15–70 minutes each; 1 by phone) were conducted by C.L. during 2 day site visits at the six FHTs in June, 2018. For two small group discussions, two people were interviewed together using the interview guide. Site visits increased depth of understanding, and these insights were recorded through context memoranda about the FHT and broader community, such as proximity of other health care services, availability of food, access to public transportation, and any visible ways a community aimed to support their older adults who were at nutrition or falls risk. At the time of the interviews, C.L. was a Ph.D. candidate in health studies with a background in public health nutrition and implementation science/practice. C.L. has experience conducting interviews with health professionals but had no previous relationship with the participants. All digitally recorded interviews occurred during work hours and participants could leave at any time.

Analysis

After all interviews were completed, a preliminary summary of key points was sent to all sites. As a first-level form of member checking, each FHT was requested to respond to the summary if it did not accurately represent their screening process and program. The table of key characteristics and screening program for each site was checked with FHT contacts.

Verbatim transcription was completed by a professional service for interviews with FHT staff and management. Summaries and verbatim quotes were used for the client interviews; these were not transcribed. One researcher (C.L.) conducted initial thematic analysis of interview transcripts and context memoranda using NVivo 12. The Saldana et al. inductive approach of first and second cycle coding was used, with one idea per first level “code” (Miles, Huberman, & Saldana, Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana2014). Second level codes were formed by grouping first level codes that had the same ideas. After line-by-line coding, thematic analysis was conducted and a diagram was created to summarize findings (Figure 1). To increase trustworthiness and triangulate findings, a table of suggested themes supported by key quotes and the diagram were shared with H.K. to check against transcripts (n = 3). The table and diagram were also shared with W.C. to compare with her experience with the NE SOYF strategy. Modifications to the diagram and themes resulted from this analytical step. Results were presented by webinar to representatives from participating FHTs to confirm themes and inform next steps.

Figure 1: Summary of themes from the Family Health Team staff, management, and client interviews

This manuscript uses the term “client” to refer to an individual who receives care from the FHT. Several interview participants used “patient” and “client” interchangeably, and therefore quotes may include either term.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Waterloo Research Ethics Board (ORE #22965). The NE LHIN agreed that all FHTs were covered by the University of Waterloo ethics. All participants signed written consent forms before the interview and were orally reminded that it would be audiorecorded.

Results

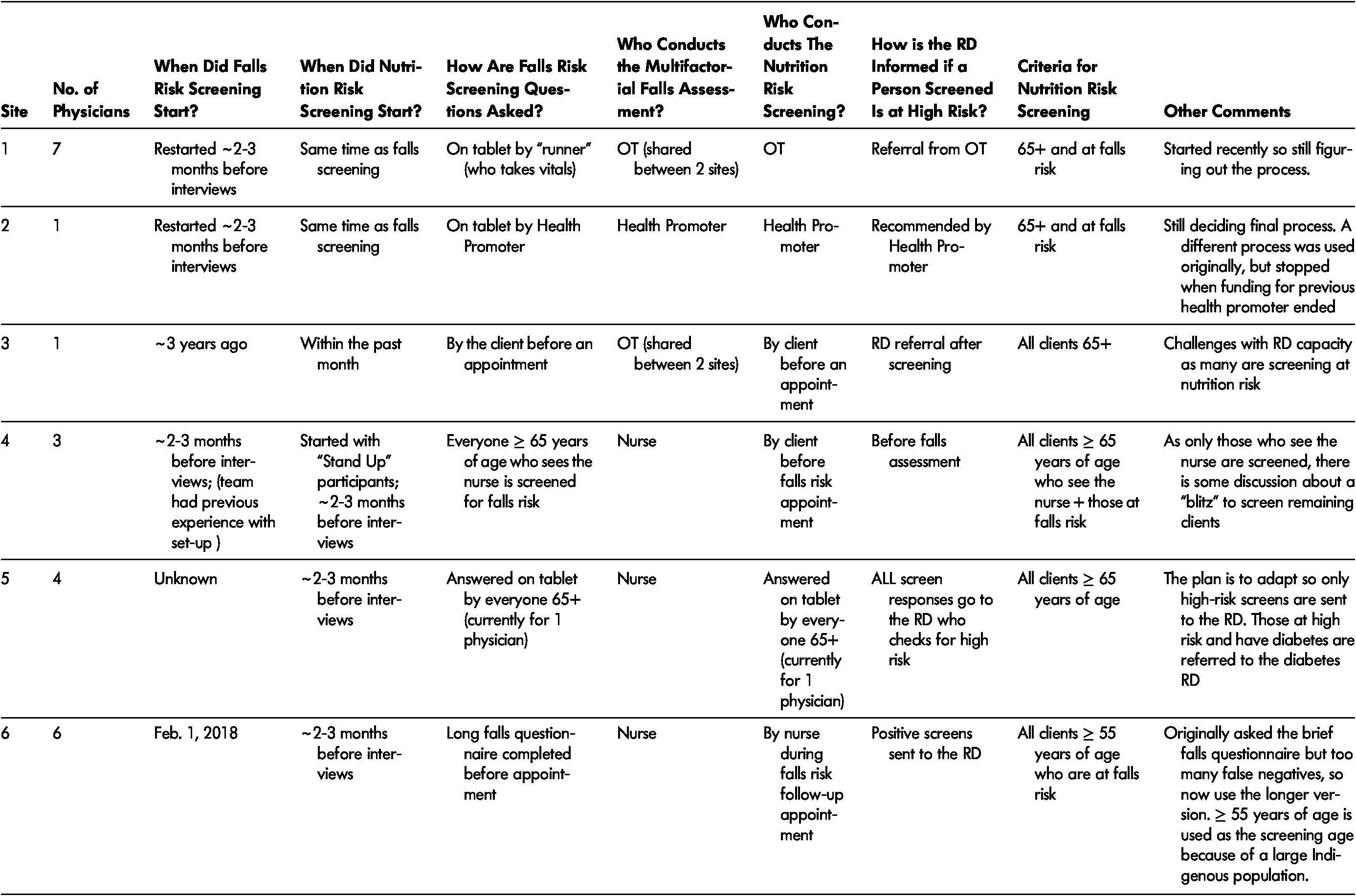

A total of 29 interviews with 31 participants (two small group discussions) were conducted with FHT staff and management (20 interviews; n = 21), regional representatives (n = 3) and clients (6 interviews; n = 7). Demographics of FHT staff, management, clients, and regional representatives are provided in Table 2. Details regarding the screening process for each FHT are in Table 3. Participants described three steps in building the falls risk screening program and adding nutrition risk screening: needing to set up for successful screening, making it work by building a system customized for their team, and facilitating at-risk clients to attend follow-up. An overarching theme was the need for strong relationships and to work as a team, recognizing that FHTs are uniquely positioned to support their clients in prevention of injury and need to connect to organizations with shared values. Additional quotes for each theme are provided in Table 4 and summarized in Figure 1. Superscripts accompanying each quote refer to their role and site. The letters “A-F” represent the label for each FHT. “Regional” represents an individual with an overall perspective, rather than from one FHT. “Client” refers to an individual who receives care from the FHT. “ED” is the Executive Director of an FHT. Other roles include dietitian, office administration and nurses.

Table 2: Demographics of family health team staff, management, regional representatives and clients

Note. Some participants selected more than one response, so values may not add up to 100%. *Includes one small group discussion with two participants.

Table 3: Family health team characteristics by case

Note. RD = registered dietitian; OT = occupational therapist.

Table 4: Summary of themes and applicable quotes based on interviews

Note. FHT = family health team; SCREEN II = Seniors in the Community: Risk Evaluation for Eating and Nutrition, Version II. Notation accompanying each quote refer to the FHT, interview number and role within the FHT. The letters “A-F” each represent one FHT.

Setting Up for Successful Screening

Participants described the need to set up for successful screening by demonstrating the importance of falls risk identification and prevention, and later for nutrition risk, to FHT staff, management, and clients. First, screening needed to be seen by the team and the client as a benefit to the client’s care. “I would say it’s about patients first, and it’s about helping people understand that they don’t have to fall, that they can do things to make sure they can live independently and stay active and vibrant in their community.” I1 (Regional) Using evidence-based screening tools for both falls and nutrition screening was thought to help clients by “identifying needs within the seniors that they wouldn’t have otherwise identified” I3 (Regional); as well as making clinical appointments more efficient, “if we can move that [answering checkbox questions] into the hands of the patient [before the appointment], then they [the physician or allied health] have more time to focus on the actual patient encounter instead of the computer.” I3 (Regional) Given the practical nature of the tools, clients also recognized the importance and benefits of screening. As one client noted: “I got half way through it [nutrition questions on tablet] and I realized, umm, it was an awakening call because I realized how poorly I was beginning to eat. So, it was a positive experience for me. …. But I also knew by the end of it that I was in trouble. That I would be getting a call from somebody.” C-I3 (Client)

Demonstrating the importance of falls and nutrition screening, to prevent falls and other adverse events, also laid a strong foundation on which to build the reason for screening. FHTs have a unique and valuable role in disease and injury prevention and health promotion, including through screening. “We shouldn’t be in the business of chronic disease management, we should be in the business of health and wellness as a society.” F-I5 (ED) However, if the steps in screening through to referral did not happen, this was discouraging for staff, as it did not lead to a proactive change for the client. For example, as described by a team member, “I asked the one girl before I came in [to the interview] ‘Any input?’ She said…you asked. She finds it a waste of time, she feels like no one looks at it, no one follows up on it, and the tablets don’t always work.” A-I2 (Office Administration) Setting up for success means that the full process from screening through to referral is planned, negotiated, and acted out to benefit the clients.

Setting up screening for success was also about seeking opportunities and being innovative, such as participating in pilot projects or connecting with existing practices. “We also talked about doing, like, flu shot clinics when they’re here sitting and waiting, that ten minutes after they got the shot, that we can optimize that time to do screening.” I3 (Regional) Opportunities also came through using and sharing existing resources such as tablets, customized handouts, or funding. “We’ve developed the tools and they’re available for anyone to use.” I1 (Regional) There were several examples of sharing funding, including sharing allied health time across sites. “Although one person gets funding for it, all three FHTs get access to it.” I3 (Regional) Such sharing of resources provided the capacity for FHTs to develop a screening program that promoted follow-through for at-risk clients.

In recognizing the need to monitor progress, the 27 FHT EDs agreed to submit standardized outcomes in their mandatory reports to the ministry, including for falls risk. “We work[ed] together to create a standardized list of indicators and one of the common things was falls. So yes, we are measuring that and we’re tracking our data on falls.” C-I5 (ED) The setting up of this standardized system aimed to facilitate monitoring of change over time for prevalence of risk and provision of support. As this system was set up for falls risk, it was thought that a similar model could be followed to allow for monitoring and evaluation of nutrition risk.

Getting started with screening sometimes required the endorsement and support from others outside of the particular FHT. Promotion of falls and then nutrition risk prevention from reputable organisations helped to build a foundation for screening: “If the Association of Family Health Teams is recommending that you do it, then it’s probably more likely to move in that direction.” I2 (Regional) Looking to exemplars and other FHTs also provided an incentive: “I think there may start to be a bit of peer pressure once they realize the things that other teams are able to achieve. I mean, eventually you’re going to become a late adopter and sort of get pressured into the system.” B-I1 (Dietitian) Sometimes garnering support and resources from a regional agency was a way to get screening started, and once initiated, it was considered an important part of care. This dietitian involved in the initial fall risk screening also indicated “I always suggest that they approach their LHIN or their health unit, someone else who might have that mandate of falls prevention and might be able to contribute to paying for the services. Even if it’s just a pilot to get it started. We found here that once our staff and physicians saw how it [the tablet system] worked, they wanted to keep using it.” B-I1 (Dietitian). Although the tablet cost was upfront and could be supported by any of the previously suggested methods, annual renewal of the Ocean subscription was also required. Many sites found that if the tablet had improved efficiency in delivery of care, they could justify the renewal cost. Sites that did not have an efficient system could stop the subscription and restart; for example, after they had set up a process for those at risk.

Making it Work

When starting to build the screening program, the FHT had to figure out how to “make it work” I3 (Regional) for their particular service; a “cookie-cutter” approach was recognized as not being sufficient. Every FHT was unique, and the screening process needed to adapt to their own work flow. “They [FHTs] don’t have the same work flows because of different people and different patient loads. So, it’s really dependent on the team and how they’re built and what the capacity is for this.” I1 (Regional) The emphasis for both falls and nutrition screening was on starting small and following quality improvement methodology, testing out the work flow, and adapting as needed. “Implement slowly and learn from that and evaluate it as you go.” F-I5 (ED)

Each FHT had to determine their own screening process, and this required decision making and negotiation on how the screening would look. When planning the work flow, key decisions needed to be made about who would be screened (e.g., over age 65, only those at falls risk), when the screening would occur (e.g., in the waiting room, during a falls risk appointment) and who would facilitate the process (e.g., clients themselves, allied health at a different appointment). One FHT “decided we wanted to screen all patients 65 and older [for nutrition risk], not just our high-risk falls people, … we know that a lot of our seniors have issues with nutrition. They don’t necessarily score high for falls risk. So, I didn’t want to lose anybody in that process.” E-I1 (ED) In another site, “the nutrition screening was more of a follow-up screen from the falls screen.” D-I6 (Dietitian) Other examples are provided in Table 4.

Once these process decisions were made, the tablet needed to be “customized to the workflow of the team.” I3 (Regional) A common phrase when discussing the technology was: “I’m told it can be done, but I just don’t know how”A-I2 (Office Administration), suggesting that it took some time for communication and planning with regard to the tablet to make screening work. Those implementing screening (the “change team”) needed to figure out what was technically possible and what would work best for their work flow. “We have to figure out ways to have the process work. So, we have to do it and then evaluate it to make sure it’s as efficient as we can make it.” F-I5 (ED) Sites that had gone beyond the initial set-up found that their screening process was easy to use, and what was learned along the way encouraged other FHTs to get started. “Once all the kinks have sort of been worked out of this process and it’s easy and simple to do, I’m hopeful that the others will come on board.”I2 (Regional) Sites that had a functioning falls risk screening program typically found it easier to add nutrition risk screening, because they were adapting an existing system.

As clients are a key part of the team, a component of making it work was ensuring that clients were informed about why they were being asked these questions, and to understand that their FHT was using screening to support them to stay independent in their own homes. “I think people just need to be… Have their attention drawn to it [falls and nutrition risk].”D-I1 (Client) Clients also needed to feel comfortable with using the tablet technology, as it was integral to the screening process for FHTs. However, there were mixed opinions about how easy it was for clients to use the tablets. Clients discussed the importance of technology in their lives: “A lot of seniors, that’s how they keep in touch with their families. They’ll have an iPad or computer – oh yeah!”C-I3 (Client), indicating “I bet ya 90% of people would be able to use it [the tablet in the FHT].” C-I3 (Client) One client indicated, “The tablet is a bit of a hard thing to use, only because of the contrast issues for those with low vision.”D-I2 (Client) With a little support, clients became more comfortable using the tablet: “[I went] over the first couple of questions with them [the client] and showed them how to input the information. And they realize how easy it is, and then they sit down and complete the rest.”B-I4 (Office Administration)

Part of developing a screening program for both falls and nutrition risk was determining the work flow and how those identified as being at risk would be treated. “If we start to do these risk assessments and they’re at risk, if we don’t have somewhere for them to go for care and management, then that’s unethical.” F-I5 (ED) The support available for those at risk varied based on staffing, capacity, and availability of FHT and community resources. One site had originally started screening for falls risk but then stopped until they were able to provide enough support for at-risk clients. Some sites modified the process based on their capacity. For example, switching the falls risk questions so that the longer version was used on all clients, leading to more appropriate referrals, indicating that it “will be a more accurate reflection of who we do need to see. … I think we’re going to get to the people that we actually can do something about.” D-I5 (ED) Another strategy for ensuring time for those at risk was “to put predetermined spots in my schedule [for clients at falls risk]” B-I3 (Nurse), and have trainees conduct follow-up assessments.

Following Up with Risk

Once clients had been identified as being at falls or nutrition risk, they needed to be supported to attend the organized follow-up, such as an appointment at the FHT with a nurse, occupational therapist or dietitian), and/or to attend a community-based program, such as “Stand Up”. ‘Stand Up’ is “an exercise program for older adults with concerns about balance or mobility” B-I1 (Dietitian) that also includes a section about nutrition delivered by a dietitian. Participants mentioned that their clients were not always interested in nor did they understand why they were being asked to a follow-up appointment for either falls or nutrition risk screening. “I think the biggest challenge with some of our elderly people … is a matter of getting them in for another appointment. It’s like pulling teeth to get them to come in. … They want to know what is going to help them and what is the benefit for them to come in and do this.” D-I3 (Nurse) One site indicated, “I think the main thing that was discouraging is that all these people are testing positive for falls but, I would say, 90% decline an appointment… We have very, very low numbers on people that actually want the falls prevention appointment.” A-I2 (Office Administration) Many reasons for lack of follow-up were suggested. "I think it comes back to the greatest barriers and the reason why it doesn’t happen is the social determinants of health, honestly. Education is not that high here. We have a huge unemployment rate. All of those factors come into play to the point where how can it be important to them? … And there’s also the fear. There’s a great deal of fear, and how do you combat that? Right? If you can’t get to them, how do you combat it? You can’t. So, you do what you can.” D-I5 (ED).

To encourage more clients to attend follow-up, one participant indicated that, “I’m not sure they [the clients] understand that there’s a lot of things that we can do to minimize their [falls or nutrition] risk and actually keep them there [at home]. … I think if they did have a bit of information before they came in, that might help.” D-I3 (Nurse) FHT staff who book the appointments were an important source of information for the clients when making their decision to attend the follow-up. “If we [staff booking the appointment] can’t sell it, why are they are going to want to go to it.” A-I2 (Office Administration) Suggestions to improve this process included ensuring that the staff booking the appointments had “information on what’s going to happen in the falls prevention appointment, because I know we’ve been asked that. We kind of say “No, she’s going to go over things with you.” But, really, we don’t know. We don’t know what she’s talk[ing] about and what she does.” A-I2 (Office Administration) Some sites have developed a script for office administration that could also be used by any member of the FHT staff as a guide when speaking with at-risk falls or nutrition risk clients as a way to incorporate key messages into the conversation and help mitigate some of the fear. “Our dietitian had created a script for what the front office could use to communicate.” F-I5 (ED) Having allied health staff ask the questions during clients’ falls risk follow-up appointments was also suggested to encourage follow-up.

Another reason for lack of follow-up for nutrition risk may be concern regarding whether clients understood the role of a dietitian. When asked if she thought that people know what a dietitian does, one client responded: “No! Absolutely not! I think most people figure that the dietitian is just there to tell you what to eat and how you’re eating wrong.” D-I1 (Client) Further explaining the role of dietitians and increasing their visibility in the community was thought to support follow-up attendance with a dietitian for those at nutrition risk.

The customized handout available with SCREEN-II-AB was seen as valuable for all clients, whether at nutrition risk or not. By using the handout, those who were not at risk were provided helpful suggestions for prevention, and those at risk received specific feedback for why they should see a dietitian. “I think it [the handout] might even be more worthwhile for the patient, because that way they’re not just filling it out and being done with it, they actually get the reason for doing it.” A-I2 (Office Administration) For those at risk, seeing their answers was thought to help them understand why it would be beneficial to see a dietitian. There were mixed opinions regarding the benefit of creating a customized handout for those at falls risk. Some staff indicated that they already used an individualized approach, only providing relevant resources to the client. Another participant indicated: “I think it [falls risk handout] will be immensely helpful for the team,” I3 (Regional) with potential for the same benefits to improve follow-up as the nutrition handout. When asked about the value in receiving the individualized handout, one client indicated: “Absolutely, because I’m trying to change things … I think that would be really, really helpful.” A-I6 (Client)

Strong relationships among all staff and clients were described as impacting screening and follow-up compliance. One participant compared the relationship between two sites, indicating that at a site with stronger relationships with their clients, older adults were less likely to decline to answer screening questions or attend follow-up: “Our admin staff in [FHT name] have a really good relationship with all our patients. … I would see it being more of a possibility for someone to decline to do the screening here just because of who’s asking them, because they don’t have that same connection.” F-I2 (Dietitian)

Several FHTs ran their own falls risk support programs and/or connected clients with other local opportunities. “If they have questions they can ask me right at the visit or any time I see them and then I tell them about all our programs that we’re doing. … If there’s anything that’s applicable outside of what we offer that might be good for our patients then we just tell them about that program.” C-I4 (Allied Health) “Stand Up” was mentioned frequently with one client indicating “the Stand Up program is excellent. I would advise anyone over 70 to take it” D-I1 (Client), and that, “it [Stand Up] gave you strength in the exercises. Showed you the proper way to get up when you fall. … I do some of those exercises still.” D-I2 (Client) A nurse involved indicated, “It’s unreal how the social aspect [of Stand Up] is getting people out of their… they’re feeling down in the dumps and just coming twice a week with people that are now their new friends, is making a huge difference.” B-I3 (Nurse) Unfortunately, “Stand Up” was “a bit resource-intensive” I2 (Regional) as it is a 12-week program, 2.5 hours per week, and run by health professionals, therefore needing time, space, and money to operate, and transportation was an issue for many participants.

Another program mentioned frequently was “From Soup to Tomatoes,” in which an instructor broadcast and recorded an exercise program for older adults to be viewed from anywhere, including their own homes. “Now they have all the exercise classes on a USB. It’s sustainable because it’s peer-led older adults coming together in a donated location, and they just invite all their friends. They do exercise when they want, for how long they want, and how often they want.” I1 (Regional) Another benefit “is we really are promoting it as a peer-led initiative, so you physically come together with your peers so that there’s that reduced… the social isolation. What we’re hearing is that if Mrs. Smith doesn’t show up for exercise class in [location], everybody notices she’s not there, and someone takes on the responsibility of following up and seeing if she’s okay. So, it’s community care.” I1 (Regional) At the point of interviews, nutrition has been included in “Stand Up”, but few community nutrition programs were available. Based on the benefits to clients beyond physical activity, similar community-based activities focused on nutrition were encouraged.

When an FHT was running a falls prevention program and recruiting participants, it was noted that “around here it’s a lot of word of mouth.” C-I4 (Allied Health) Other strategies were also used to promote attendance. “We’ve done actual personal invitations. … [with a letter saying] ‘Your doctor is recommending that you attend this program,’ and that is the key.” E-I1 (ED) There are many identified barriers to attending a follow-up appointment or programs, including transportation, cost, and the weather, which were particularly strong barriers in Northern Ontario. “You can have all these nice classes, but when it’s like minus 30 outside and there’s a storm and stuff like that, then people who are more at risk of falls, well, they don’t really want to adventure out.” F-I3 (Allied Health) Another participant indicated that when setting up a new program, “trying to make most of my programs either low cost or free of cost is my number one goal.” C-I4 (Allied Health) FHTs also connected with other community organisations and programs, such as other FHTs, public health units (PHUs), or local gyms to work together to meet the needs of their population. Some of these models should be considered in developing nutrition-focused community activities for those at risk.

“It’s About Building Relationships”

Throughout all of these themes is the need for FHTs to build strong relationships and work as a team to meet the needs of their clients. “The thing is, and it’s not a secret, it’s about building those relationships, it’s about non-competition, it’s about looking [at] what’s best for all. We’re all going to benefit from this. There’s not a downside to these things. In fact, what happens to one place is going to be better for the next place and the next place. So that is the key to the success. It’s the relationships and the mutual respect and the trust that, when we come together, we want the best for our patients.” D-I5 (ED) These relationships were essential within the FHTs, working together as a team and with others in the community, all learning from each other and sharing resources, ideas, and staff in a non-competitive environment. There was emphasis on having FHTs, the LHIN, and PHUs work together because they share a common goal. “We’re both [FHTs and PHU] in the same business seeing the same patients, so there’s no reason that we shouldn’t be trying to work on things together to come up with creative solutions in a rural environment where we’re under-resourced. We need to maximize everything that we have.” A-I3 (ED) There were mixed views on the strength of these connections. “I know there’s often a disconnect across say primary care, public health and the other sort of healthcare sectors, that generally we just kind of work in our silos. We might have the same goals and the same objectives, but we’re not necessarily working on them together.” B-I1 (Dietitian) The dietitian further indicated: “I think the challenge is that often we don’t know who to call. … we’re kind of working on the same things, but we don’t really know what each other is doing or who is in each office.” B-I1 (Dietitian) Another participant indicated: “People already know who everybody is and who’s working on what and how to contact people” I2 (Regional), so perception on the strength of relationships depended on the community and those involved in making these linkages.

Within the FHTs, there was a need to work as a team, treating each other as equals. When implementing screening, the whole team needed to be aware and know their role. “I think the definition of the relationship needs to be clear in that it’s not just the champion or the management… It’s everyone involved. … If we are looking at that patient, they are key driver in the success and the spreadability of anything that we do.” D-I5 (ED) It was also thought to be easier to implement and sustain something new, such as falls or nutrition risk screening, when the full team could see the benefit. “Trying to get the whole team involved as much as possible and have everyone understand.” F-I2 (Dietitian) The culture of the team played a role, and each FHT was different. “We have one small team in a rural community, and the culture is different because of the leadership and the lack of buy-in by the physicians, whereas other teams have much more positive culture, might have buy-in by one physician, or two, but they’re all making it happen.” I1 (Regional)

Screening was mentioned to have an impact on teamwork in two ways. For one, screening using an evidence-based tool helped connect the team and have more appropriate referrals. “I think it’s [screening] a good excuse to refer within our own team, because sometimes you get in your little chute and just do your thing.” D-I3 (Nurse) It was also explained that use of the tool helped build trust. “It’s about trust; and having standardized tools would help because then you’d know that these things are being done, and they would help build the trust.” I1 (Regional) The process of implementing screening also improved teamwork. “I think working together on whatever project it might be just automatically sort of brings the team a little bit closer together and helps to build some communication.” F-I2 (Dietitian) When asked if screening changed the way the team worked, a participant indicated “I think it, sometimes, brings awareness to our inner professional practice in that it helps us understand better what our colleagues are looking at, and what are they assessing. … That then broadens our knowledge and our awareness of those factors, if we’re screening.” D-I6 (Dietitian)

Key components within teamwork were effective communication, trust, and having shared values. “It starts with trust. It starts with the ability to agree that you’re going to look at something and know that you don’t have all the answers, but together you’ll figure it out, even if you fail a little bit, as long as you pick up and keep on trying some more. And when you have a team of people that actually care about the same thing and just care about trying to make something work, you can go far. It may take time, but you can make a difference. So yeah, you can’t do this work in isolation. There’s no way.” F-I5 (ED)

When asked for advice for other FHTs thinking about starting nutrition screening, one participant answered: “Please do. Add the nutrition screening in some way, shape or form to your practice. Whatever that looks like will be different based on your organization’s needs, your population’s needs and your location, but I think it’s a great thing to be pursuing, and I think it should be pursued, which is why I’m now making the effort to try and find opportunities to incorporate it in the other places where I work.” D-I6 (Dietitian)

Discussion

FHTs in this study started building a falls and then a nutrition risk screening program by setting up for success with a strong foundation, figuring out how to make the process work for their specific team and work flow, and encouraging at-risk clients to attend a follow-up appointment or program. Throughout, there was the need to work effectively as an interdisciplinary team and to build strong relationships with other individuals and organisations with shared values and goals. The screening program aimed to support older adults so that falls and nutrition risk could be identified, and preventative interventions provided and utilized. FHTs have a valuable role in prevention, and this study provides guidance for others working towards developing their own screening program or adding nutrition risk screening to an existing program.

In setting up an ethical screening program for falls and nutrition risk prevention, resources within the FHTs were needed, including having a trained or relevant allied health professional as part of the team with the capacity to provide follow-up for clients screened who were at risk (Kondrup et al., Reference Kondrup, Allison, Elia, Vellas and Plauth2013). Having these trained professionals was part of setting up for successful screening and making it work. Beyond these appointments with allied health, connections to community programs provided additional support (i.e., attendance at “Stand Up” or a Tai Chi class that had the facilities and instructors to run the course). Setting up these connections was part of making it work, facilitating follow-up with those at risk, which were strengthened through building relationships. Although teams did not have the opportunity to fully develop these connections for those at nutrition risk as they were only at the beginning stages of developing a screening program, learning from successful exercise and falls prevention activities (e.g., including a socialization component, bringing the program to the older adults where they live) will promote successful uptake.

Community activities are essential for screening programs in primary care. Even when follow-up appointments were available for a falls assessment or to see a dietitian with the FHT, many at-risk older adults declined this medical visit follow-up. In acute care, when risk is identified, treatment is provided or initiated when the patient is hospitalized. Providing services to meet the needs of at-risk clients in the community is more difficult, as this at minimum requires a new appointment with a member of the team, and clients often have challenges attending such appointments. As demonstrated in this study, activities provided to the older adults where they live or in other accessible locations where they are already visiting (e.g., a recreation centre) is one strategy to promote follow-up. For those at nutrition risk in this study, a customized handout not only met the need for follow-up but also demonstrated to clients the types of strategies that they could undertake, potentially with further guidance and counselling by a dietitian.

FHTs suggested strategies to facilitate follow-up including having a phone conversation to discuss next steps, or connecting follow-up appointments with pre-existing appointments. Declining follow-up has been reported in other studies, with one indicating that 66 per cent of dietitians reported clients at nutrition risk “sometimes/often” declining an appointment with a nutrition professional (Craven, Pelly, Lovell, Ferguson, & Isenring, Reference Craven, Pelly, Lovell, Ferguson and Isenring2016). Also, when learning that they were at nutrition risk post-screening, some older adults have reported they were surprised or upset by the results, others were unconcerned, and some did not understand what it meant to be at risk (Reimer, Keller, & Tindale, Reference Reimer, Keller and Tindale2012). For some clients, education, such as through the customized nutrition handout, may be the start of behaviour change (Southgate, Keller, & Reimer, Reference Southgate, Keller and Reimer2010) and may be the preferred post-screening activity (Keller, Haresign, & Brockest, Reference Keller, Haresign and Brockest2007). Screening practices should also include monitoring of those at risk (Kondrup et al., Reference Kondrup, Allison, Elia, Vellas and Plauth2013); however, this is more difficult in the community than it is in acute care, as follow-up and monitoring are more challenging when clients live at home. Regular re-screening is also encouraged (Kondrup et al., Reference Kondrup, Allison, Elia, Vellas and Plauth2013), and several of the FHTs in this study had or were planning to re-screen annually.

Sites recognized the benefits of collaboration with individuals and organisations with shared values and goals for health care post-screening. For example, community services and programs provided or supported by other organisations could benefit at-risk clients screened in FHTs. Opinions were mixed regarding the strength of that collaboration, particularly with PHUs. These varied opinions may be because of differences in the awareness of collaborations, as within an FHT, some participants indicated strong collaborations of which others were unaware. The relationship between primary care and public health has been explored, indicating ways that it can be mutually beneficial and strategies for collaboration (Martin-Misener et al., Reference Martin-Misener, Valaitis, Wong, MacDonald, Meagher-Stewart and Kaczorowski2012; Stevenson Rowan, Hogg, & Huston, Reference Stevenson Rowan, Hogg and Huston2007; Valaitis et al., Reference Valaitis, Meagher-Stewart, Martin-Misener, Wong, MacDonald and O’Mara2018). The current study reinforces the importance of such collaborations, as not all clients at risk can be met with or want individualized primary care treatment. Relatively few participants in this study were from PHUs, and further interviews with health professionals in this sector would increase understanding of how collaboration can be fostered with primary health care clinics.

Several reviews have explored falls prevention interventions (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Tan, Ning, Li, Gao and Wu2018; Guirguis-Blake et al., Reference Guirguis-Blake, Michael, Perdue, Coppola and Beil2018; Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Thomas, Veroniki, Hamid, Cogo and Strifler2017). One example of a comprehensive project exploring the implementation and sustainability of a falls prevention program with general practitioners is underway in Australia in the Integrated Solutions for Sustainable Fall Prevention (iSOLVE) project (Clemson, Reference Clemson2018; Clemson et al., Reference Clemson, Mackenzie, Roberts, Poulos, Tan and Lovarini2017). iSOLVE is similar to this work in that it includes screening of clients over 65 years of age, using tablets with the Staying Independent Patient Checklist, among other components (Clemson et al., Reference Clemson, Mackenzie, Roberts, Poulos, Tan and Lovarini2017). The evaluation of iSOLVE is a large study (28 general practices) exploring practitioner practices to reduce client falls, cost effectiveness, and change in use of medications known to increase falls risk. iSOLVE also included allied health interviews that indicated that falls prevention was complex, with challenges of: working with clients with varied needs, working with allied health with varied understanding of roles, competition, and communication (Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Lovarini, Clemson, Mackenzie, Tan and Pit2018). Forthcoming results from iSOLVE, including outcomes, barriers to, and facilitators of falls prevention program implementation and sustainability, will likely be applicable to the FHT falls prevention and screening programs. Other programs can also be considered to address needs of individuals in more rural locations, such as through telephone-assisted peer coaching or other types of virtual care.

Although a key component of this study was use of the tablet system, many of the same strategies are thought to apply to building or adding any screening program. Not all FHTs have access to tablets; however, they are becoming more common in health care, with literature suggesting that older adults have overall high ratings for satisfaction with using tablets, including helpfulness and usability (Ramprasad, Tamariz, Garcia-Barcena, Nemeth, & Palacio, Reference Ramprasad, Tamariz, Garcia-Barcena, Nemeth and Palacio2017).

Strengths and Limitations

The FHTs in this study were at different stages of setting up their screening program. A few FHTs had been conducting falls risk screening for several years and were able to discuss how they sustained the program. Others had started during the initial falls pilot but recently restarted when support for those at risk became available, and, therefore, falls and nutrition risk screening were begun simultaneously. This variation in stages provided the opportunity to explore perspectives from the first steps of adding nutrition screening to an established program as well as starting falls and nutrition screening together. This variation may have limited depth of understanding of each stage, particularly understanding how screening was sustained; however, saturation of themes was still achieved around initially building a screening program in FHTs. Further work is encouraged for understanding if and how this screening program was sustained and spread to other settings.

Client opinions were included and provided a unique perspective; however, they were not from all FHTs, as client recruitment was a challenge for some sites, particularly those at the early stages of building their program. Some client participants had been screened, however not always as part of an established FHT process. Several clients who were participants were not at risk, and therefore had not experienced the full ethical screening program to attend a follow-up appointment, nor had they attended community programs. However, client participants were still aware and had opinions about the reasons why some clients may decline follow-up, and had experience with various programs, particularly for falls prevention. Further interviews with falls and/or nutrition risk clients who accept and decline follow-up, including declining to attend a community follow-up program, would add further insight.

FHTs in the NE LHIN may have different experiences than those in more urban areas. For example, one FHT in a small community benefited from strong relationships with their clients; however, food access was a challenge, as the small grocery store was only open in the summer, and the next closest was a 45 minute drive away. Comparison between urban and rural FHTs was not made, because these FHTs typically had large catchment areas that included clients from rural and urban areas, making comparison difficult. Differences in collaboration with services in more urban centres may have resulted in further findings with respect to building a screening program that is linked to these services in the community.

Mapping qualitative findings to quantitative data was not within the remit of this study. Further analysis should explore how many older adults were: screened for falls and/or nutrition risk, were at risk, attended a follow-up appointment, and attended a community program. Further exploration is also needed for if/how sites without a dietitian would ethically screen for nutrition risk.

Conclusion

With the high prevalence of falls and nutrition risk among older adults living in the community, building and sustaining a screening program with both of these aspects is an important aspect of FHT care. Primary care providers have a unique opportunity to identify those at risk and link the client to prevention resources and programs. FHTs indicated the need to set up for success, to make the process work for them, and to follow up with those at risk, recognizing the beneficial impact of strong relationships, collaboration, and teamwork. Understanding how FHTs add nutrition risk screening to a falls risk screening program can help support other FHTs interested in supporting the needs of their older adult clients in this way.