The Palaikastro Kouros is a Cretan Bronze Age chryselephantine or composite statue of a young man, which takes its name from the site where it was found in eastern Crete. The face, torso, and legs of the Kouros were made of ivory, the cranium and hair of serpentine, and the eyes of rock crystal. The separate ivory pieces had been held together with wooden dowels and parts of the body had been covered with gold leaf. Traces of blue pigment were found on some of the gold fragments (Moak Reference Moak, MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000). The ivory, which was hippopotamus ivory, must have been imported from Egypt, which is also the most likely source for the gold (MacGillivray and Sackett Reference MacGillivray, Sackett, MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000: 165). It has been suggested that the young man wore a gold loincloth and sandals. An ivory pommel suggests that he had a dagger at his waist. White frit beads that were found in the area might be the remains of a necklace. The Kouros is estimated to have been c. 50 cm high. Fragments were recovered from an area of 11 square meters. The excavators therefore concluded that the most reasonable explanation for their wide dispersal was that the statue had been deliberately and violently smashed (MacGillivray et al. Reference MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000). That the Kouros had been the victim of iconoclasm is an interpretation that has been generally accepted.

The materials of which it was made and the find context indicate that the Kouros can be identified as a statue of a god. It must have been an extremely valuable and prestigious object, reflecting its cultic significance to the inhabitants of Palaikastro. Although it is much smaller, the statue has been seen as a prehistoric precursor to the monumental chryselephantine cult statues of the Classical Greek period. Before it was destroyed, it had stood within a three-room structure, known as Building 5 (see Figure 1). The entrance into the building was through a wide axial doorway with a stone threshold from an open court. Fragments of rhyta (libation vessels) and of large stylized cattle horns made of stone (so-called ‘Horns of Consecration’, a religious symbol in Bronze Age Crete) were found in the area. Building 5 has been identified as a public or town shrine. Pegs under the feet indicate that the Kouros had been set into a base of some kind, presumably a wooden platform in Room 2, from where the statue would have been visible to people in the square when the doors were open (Driessen Reference Driessen, MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000: 87–88, 94–95). Palaikastro was attacked and burnt down c.1450 bc, at which time the Kouros was destroyed and the sanctuary ceased to exist.

Figure 1. Building 5, with Room 2 indicated (after MacGillivray et al. Reference MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000, Fig. 2.1). Drawing by Sven von Hofsten.

The Palaikastro Kouros is an exceptional find from Bronze Age Crete. Although it is archaeologically unique, it may not have been so in its time. The quality of manufacture indicates that it was the product of a longstanding workshop tradition. The use of ivory for the representation of human figures goes back to the third millennium on Crete. From the seventeenth century bc, Cretan ivory carving was of high quality and gold was sometimes used for hair and clothing (Hemingway Reference Hemingway, MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000). The stylistic resemblance between the Palaikastro Kouros and smaller figurines in other materials, such as clay, indicates that it has its place in the Cretan Bronze Age tradition of representing the male figure (MacGillivray Reference MacGillivray, MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000: 123–130).

The area of Building 5 was excavated in the period from 1987 to 1990 by the British School at Athens. Fragments of the Palaikastro Kouros were found in different rooms of Building 5 and in the square outside the building. The numerous fragments of the figure that were recovered from inside the building had suffered varying degrees of fire damage. The torso, which was found in the square had not been burnt. By carefully mapping the location of each fragment, the excavators have been able to reconstruct the process of destruction. The statue was removed from its place within Building 5, taken out into the square, held by the legs, and smashed face forward against the ground. The legs were thrown back into the building, which was then set on fire (Driessen Reference Driessen, MacGillivray, Driessen and Sackett2000: 94–95).

Public space in the ancient world was full of statues and other types of representation of deities, which communicated political and religious authority. The iconoclastic destruction or mutilation of images is probably as ancient as the use of images to express power. Examples are known from as early as the third millennium bc in the Near East and Egypt (Suter Reference Suter and May2012; Varner Reference Varner2004; Bryan Reference Bryan and May2012: 365–373). Although the fate of the Palaikastro Kouros may seem to be an unparalleled happening in the cultural context of Late Bronze Age Crete, it can be understood as an episode in a wider context of iconoclasm.

The word ‘iconoclasm’ is derived from the Greek for image or semblance (ϵἰκών) and to break or smash into pieces (κλάω). It is not documented in Classical Greek and was apparently not used before the Byzantine period. In research literature it has had a fairly wide usage and exactly what iconoclasm refers to has been the subject of debate. In his contribution to an edited volume on iconoclasm in different cultural contexts from Antiquity to the present, Norwegian religious historian Jens Braarvik has argued that although the deliberate destruction of images could be politically as well as religiously motivated, the term iconoclasm should only be used in connection with the destruction of specifically religious objects and images and not be extended to include the attacks on political images (Braarvik Reference Braarvik, Kolrud and Prusac2014). In my view, this is not a particularly useful limitation since it is rarely possible to separate the political and the religious into distinct spheres, regarding either the meaning of the images themselves or the motivation for their destruction. In the ancient eastern Mediterranean and the Near East, the religious and political spheres were closely interconnected. Political power could be and was often expressed through religious ritual and symbols.

I would, on the other hand, argue in accordance with the original Greek meaning of the word ϵἰκών that the term should be restricted to likenesses of people or deities to be meaningful and not used in a wider sense to include other forms of material culture, such as buildings, books, or inscriptions, even if they can be attacked and damaged or destroyed for similar reasons. Images are, however, unique in that they can be said to embody a close, almost inseparable, connection between image and the person or the god it represents – as recent examples of iconoclasm, for instance, the attack on a statue of Saddam Hussein in Bagdad in 2003 or the toppling of the city benefactor and slave-owner Edward Colston by supporters of Black Lives Matter in Bristol on 7 June 2020, demonstrate. In a sense, iconoclasm is damaging a hated individual by proxy. Targeted attacks on the facial features are a noteworthy feature of ancient iconoclasm. In certain cultural contexts, deliberately inflicting damage on an image was intended to mimic the mutilation inflicted on prisoners of war and criminals or on the dead bodies of enemies after battle. This was a common and sometimes ritualized practice in the ancient world (Nylander Reference Nylander1980; Liston Reference Liston and Brice2020).

The ‘Mutilation of the Herms’ is the perhaps the most notorious episode of iconoclasm in Greek antiquity (Furley Reference Furley1996; Hardy Reference Hardy2020: 115–120). It is documented by literary and archaeological evidence. Herms, which take their name from the god Hermes, were semi-anthropomorphic rectangular stone pillars, with bearded heads and male genitals. They had a protective and apotropaic function. In the summer of 415 bc all the herms that stood outside doorways and in the Agora in Athens were attacked during a single night. Herms had a religious significance, but they were also political symbols, and the mutilations were regarded both as horrifying blasphemy and as an attack on the Athenian state in a time when Athens was at war with Sparta. The main literary sources, the historian Thucydides (The Peloponnesian War, Book 6: 27–29) and the orator Andocides (On the Mysteries: 37–40), use the verb πϵρικόπτω, which literally means to ‘cut all around’ or ‘cut bits off here and there’ to describe the damage to the herms. According to Thucydides, it was the faces (τὰ πρόσωπα) that were attacked, and the archaeological evidence of mutilated herms indicates that the noses seem to have been particularly targeted. Modern commentators have often assumed that the genitals would also have been damaged but this is not mentioned in the ancient sources.

A mutilated copper head of an Akkadian ruler found at Niniveh is an interesting example of the iconoclastic blurring of the divide between image and a living human (Nylander Reference Nylander1980; Suter Reference Suter and May2012: 58; May Reference May and May2012: 18–19; Westenholz Reference Westenholz and May2012: 100). One of the eyes, the bridge of the nose, and the beard had been attacked with a chisel and both ears had been cut off. The head dates to the twenty-fourth or twenty-third century bc, but it was found in a seventh century bc archaeological context. It has been identified as a representation of Sargon the Great, but this is uncertain. It is also not possible to determine when in its long history the damage to the facial features had been inflicted. However, Nylander argues that the seventh century is the most likely date because the specifics of the damage to the face mimic the treatment meted out to political enemies at that time.

The close connection between the destruction of images and the manner of death of the person represented is vividly displayed in Pliny the Younger’s account of the fate of the statues of the emperor Domitian in Rome after his death in the year ad 96:

…whereas those innumerable golden images, as a sacrifice to public rejoicing, lie broken and destroyed. It was our delight to dash those proud faces to the ground, to smite them with the sword and savage them with [axes, as] if blood and agony could follow from every blow. Our transports of joy—so long deferred—were unrestrained; all sought a form of vengeance in beholding those bodies mutilated, limbs hacked in pieces, and finally that baleful, fearsome visage cast into fire, to be melted down, so that from such menacing terror something for man’s use and enjoyment should rise out of the flames. (Panegyric 52,4, Loeb translation)

After his death, Domitian was condemned by the Roman Senate to what is conventionally termed Damnatio Memoriae by historians, the obliteration or blackening of a person’s memory. Consequently, his statues were removed from public space. However, as American archaeologist Eric Varner has pointed out, Damnatio Memoriae did not necessarily involve iconoclasm (Varner Reference Varner2004). Statues and other images could be mutilated, re-carved into likenesses of other people, or recycled as building material, but often they were simply taken down and placed in storerooms. Their disappearance from the urban landscape would have contributed to them being removed from memory. Roman historians, on the other hand, delighted in preserving the memory of bad emperors and their evil deeds, which can be seen as a literary and metaphorical form of iconoclasm.

Pliny’s description of the damage inflicted on the statues of Domitian in Rome reads more like a description of spontaneous crowd violence than the orderly process of statue removal that resulted from the official condemnation of the memory of an unpopular emperor. Pliny stresses the violence of the destruction that was visited on the statues of Domitian, the anger and joy of the people attacking them, and the close connection between image and person. It is as if the living person of the emperor is being attacked. Domitian was hacked to death and the attacks on his statues as described by Pliny replicate the manner of his death. The statues that were attacked were of gold, reflecting Domitian’s claims to divine status while still alive. There is also a striking contrast between the gold of the statues and the iron of the weapons that were used to destroy them.

That the smashing of things for its own sake can be deeply satisfying is known to most people from an early age. In an archaeological context, in the absence of contextual and/or textual evidence, it can be difficult or impossible to distinguish between iconoclasm, vandalism, accidental breakage, and the ravages of time. However, there is no doubt that the Palaikastro Kouros was deliberately destroyed. Whether its fate can be classified as an example of iconoclasm rather than of vandalism can be debated. However, the excavators’ conclusion that the Palaikastro Kouros was the victim of iconoclasm remains the most reasonable explanation for its destruction. When the Palaikastro Kouros was destroyed, the head was crashed face down with some force against the stone doorpost of the entrance to his sanctuary. The focus on the facial features situates the fate of the statue in a wider geographical, cultural, and temporal context of iconoclasm of the ancient world. Moreover, dragging the statue out from its sanctuary and into the square before breaking it into pieces in public view was presumably for maximum shock effect. Throwing a part of the body back into the building suggests that those who were responsible wished to convey a clear message that a previously powerful deity was now a broken god in a destroyed sanctuary.

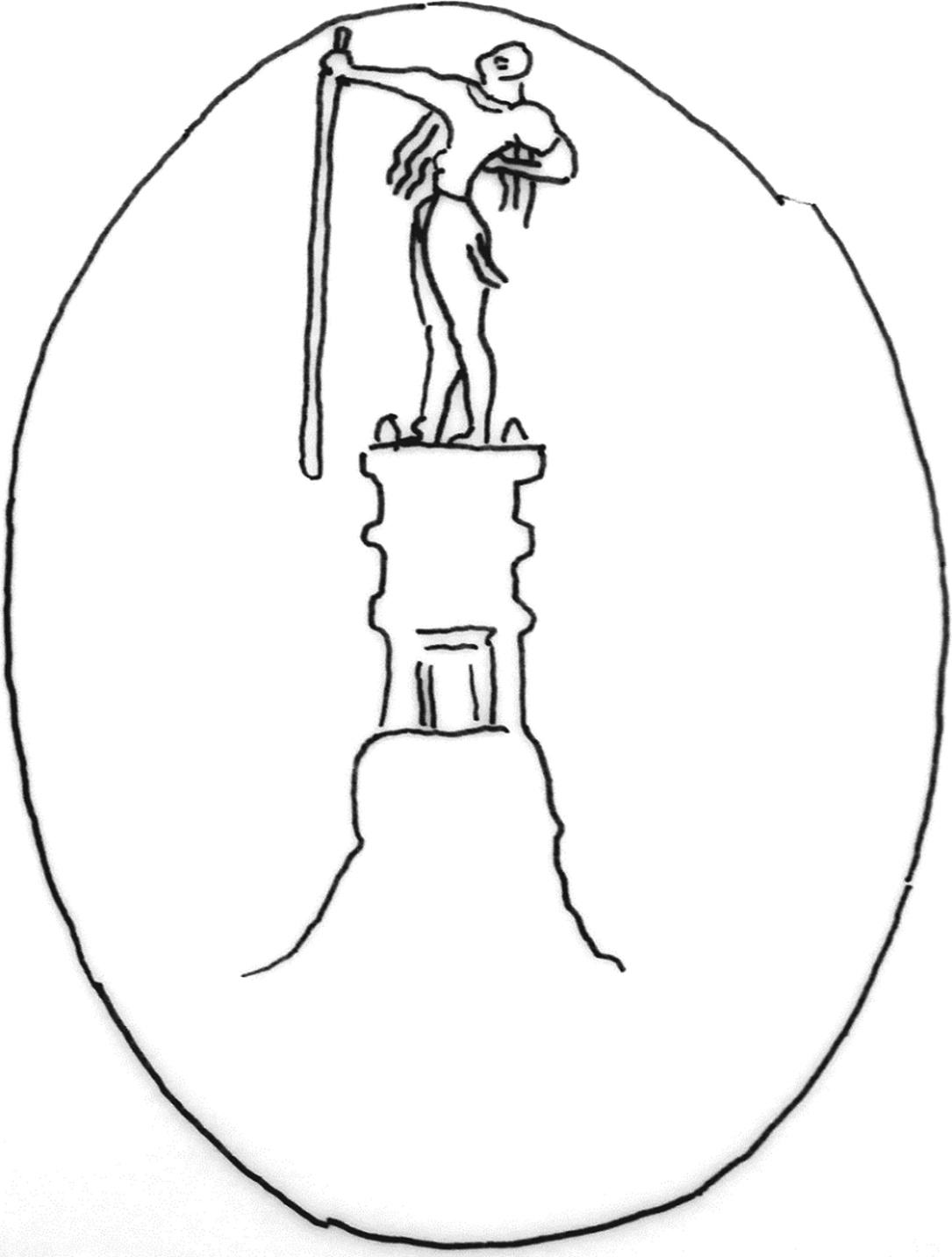

The second half of the fifteenth century bc was a period of island-wide political unrest in Crete. It may also have been a time of religious controversy. From the Neolithic period onwards, most representations of figures that can be or have been recognized as images of deities are female. Belgian archaeologist Jan Driessen, one of the excavators at Palaikastro, has therefore argued that the Kouros represents the introduction of a new god to Crete in the Late Bronze Age (Driessen Reference Driessen2015). The destruction of the Kouros can then be seen in terms of a religious conflict between a traditional cult of a female goddess that had roots going far back in time and a new, possibly foreign, cult of a male god. The intention would have been to erase the identity of and destroy the power of an intruder god by attacking his image and sanctuary. The idea that the cult of a foreign male god was introduced into Crete by the political elites, and not just to Palaikastro, in the Late Bronze Age is possibly supported by the image on a contemporary sealing from Khania in western Crete, which depicts a male figure with a staff standing in a position of authority on top of a monumental building (Hallager Reference Hallager1985, see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Khania Sealing (after Hallager, Reference Hallager1985). Drawing by Sven von Hofsten.

In the following period, there is an increased interest in the representation of a female deity in settlements across Crete (Gesell Reference Gesell1985; Marinatos Reference Marinatos1993: 222–225). Terracotta statues of a female deity, known as the Goddess with Upraised Arms, have been found within small sanctuary buildings, where they stood on platforms against the back wall. They were associated with various traditional attributes, such as snakes, birds, and poppies. The popularity and standardization of the Goddess with Upraised Arms and her sanctuaries can be interpreted in terms of a female deity reasserting and re-establishing her dominance after a period of political and religious turbulence. The use of ‘native’ clay for the statues and cult equipment could be seen as a reaction against the extravagant use of imported gold and ivory for religious display.

At present, the Palaikastro Kouros represents an apparently unique case of iconoclasm in Bronze Age Crete. It is hard to say whether its destruction was the result of extraordinary circumstances or reflects a more widespread practice on Crete in the Bronze Age. It does, however, fit into a pattern of the mutilation and destruction of images that had a long history in the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. As Carl Nylander has pointed out, the individual examples of the iconoclastic destruction of images that have been preserved indicate that the practice was probably much more prevalent than the actual evidence indicates (May Reference May and May2012).

About the Author

Helene Whittaker is Professor of Classical Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Gothenburg. Her research is mainly concerned with the Greek Bronze Age, in particular Mycenaean religion. Much of her research has concentrated on the social function of religion in Greek prehistory. She has also published on a variety of topics within different areas of Greek and Roman literature and culture. Her publications on the Imperial cult and Greece in the Roman period reflect her interest in combining archaeological and textual evidence. She also has strong research interests in Neoplatonism and in pagan and early Christian asceticism.