“The war has ruined us for everything.”

— Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western FrontIntroduction

Support for the far-right is closely linked to nativist attitudes derived from in-group favouritism among the electorate (Mudde Reference Mudde2019). However, how this in-group favouritism evolves over time, and more precisely whether it is endogenous to some historically entrenched processes, remains a largely unexplored topic in political science. To fill this gap, I examine how the shared experience of war, one of the most powerful shocks a human society can experience, has lasting effects on the level of exclusionary nationalism exhibited by a community, and how such variation in the demand for nationalism translates electorally into support for far-right political parties.

Empirically, I exploit a recently published dataset on the casualties of the French army during World War I (WWI). Between 1914 and 1919, 8.3 million citizens joined the military to fight against the Central Powers led by Imperial Germany, of whom a staggering 1.3 million were killed in action, 16% of the total conscript population and about 4% of the total pre-war population. By exploiting variation in department-level death rates, I show that departments with higher death rates exhibit, in the long run, higher levels of support for the Front National (FN)+Footnote 1 , the main contemporary French far-right party. Drawing on robust evidence from psychology and sociology, I show that this association persists because the communities exposed to higher WWI death rates develop a strong in-group preference that manifests itself in the form of a higher demand for nationalism and a lower demand for multiculturalism and internationalism, precisely the ideological positions supplied by the FN.

These findings contribute to several strands of literature. First, I add to the growing body of work showing how the experience of war fosters nationalism. Up to this point, most of this work has focused on the short-term effects of war and wartime violence (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, De Feo, De Luca and Russo2022; Cagé et al. Reference Cagé, Dagorret, Grosjean and Jha2023; De Cesari and Kaya Reference De Cesari and Kaya2019; De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2021; Koenig Reference Koenig2023). This paper suggests that if the right mnemonic infrastructure is in place to maintain and reproduce the memory of war, and if political actors are motivated to exploit this infrastructure, then the effects can persist over a very long period of time. In particular, this paper tests a very similar argument to that proposed by Cagé et al. (Reference Cagé, Dagorret, Grosjean and Jha2023) and De Juan et al. (Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2021) on the short-term effects of WWI on electoral politics in France and Germany, but also adds a robust theoretical mechanism explaining why and under what conditions such effects may persist.

Second, I build on the literature characterising the long-term effects of war and, more broadly, of large-scale political violence (Costalli and Ruggeri Reference Costalli and Ruggeri2019; Rodon and Tormos Reference Rodon and Tormos2023; Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017; Villamil Reference Villamil2021). A gap in this literature is the very strong focus, often due to data availability, on modern and contemporary civil wars. However, this form of violence tends to be confined to specific geographical areas, making the findings of these papers less generalisable. In contrast, this paper explores WWI as its setting, one of the most important interstate conflagrations in history, to demonstrate similar patterns of behavioural change as theorised by some scholars (Cunningham and Lemke Reference Cunningham and Lemke2013), thus complementing existing studies discussing the role of intrastate violence. One paper that looks at the effect of historical state actions

![]() ${20^{th}}$

on long-term attitudes and behaviour in contemporary France is Gehring (Reference Gehring2021); however, the author focuses less on extreme political violence, such as the one experienced by communities during wartime, and more on the comparative institutions that can either contain or produce negative actions.

${20^{th}}$

on long-term attitudes and behaviour in contemporary France is Gehring (Reference Gehring2021); however, the author focuses less on extreme political violence, such as the one experienced by communities during wartime, and more on the comparative institutions that can either contain or produce negative actions.

Finally, I contribute to the emerging strand of empirical work discussing the impact of WWI on future developments across Europe, and in particular in France. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first contribution in political science that attempts to understand the central role of WWI in the politico-economic trajectory of the French population, similar to work that exists in other European contexts (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, De Feo, De Luca and Russo2022; De Cesari and Kaya Reference De Cesari and Kaya2019; De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2021; Koenig Reference Koenig2023). In doing so, I complement work in economics, such as Gay (Reference Gay2023), which demonstrates the long-term impact of the Great War on the French labour market, in particular its gender dimension.

Theoretical framework

Shared war experiences and the formation of in-group/out-group preferences

The impact of political violence on societal beliefs, attitudes and behaviour is a well-established area of research in social sciences (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017; Zhukov and Talibova Reference Zhukov and Talibova2018). An extreme form of political violence, war, is known to deeply scar communities by inflicting costly physical destruction, altering the demographic composition of the population and, above all, producing a grim legacy of wasted human life (Besley and Reynal-Querol Reference Besley and Reynal-Querol2014; Gay Reference Gay2023; Hadzic Reference Hadzic2018).

One robust pattern established in the literature is that a shared experience of war can heighten social capital within a community, increasing cooperative and altruistic behaviour (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016). However, such pro-social behaviour is confined to one’s own in-group, often defined in ethnic, racial or national terms. War renders individuals more attuned to the fragility of their own experience as a community, making them willing to protect the survival of that particular experience at the expense of others (De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2021). This is corroborated by experimental research in psychology, which shows that experiencing the death of a loved one increases one’s sense of belonging to a broader identification structure, such as kin or nation (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Cassar, Chytilová and Henrich2014). In societies where such a structure of identification extends beyond consanguinity, personal loss is not even a necessary condition for triggering heightened identification, as the indirect victimisation produced by learning the stories of others in the same community is sufficient.

Most often, an increase in in-group identification comes at the expense of a decrease in out-group affinity (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Cassar, Chytilová and Henrich2014; Canetti et al. Reference Canetti, Hall, Rapaport and Wayne2013). There are several reasons why this might happen. First, out-group members may be perceived as having a wholly different experience of war, shaped by alternative sources of communal trauma which, in an environment characterised by limited collective memory resources, would compete directly for salience with the experience of in-group members. Second, the experience of the out-group may be antithetical to that of the in-group and, although both are subjective in nature, could lead to members of the out-group being perceived as a threat to the validity of the in-group experience. Third, in more extreme cases, the out-group could be blamed for the trauma that produced the in-group experience if the two groups were on opposite sides of the conflict.

How does this in-group preference manifest itself in terms of political behaviour? In democracies, the most obvious form of potential manifestation is through voting, by supporting political parties whose message is similarly favourable to the in-group at the expense of the out-group. An obvious candidate for tracing the political effects of in-group preferences would be the far-right, which throughout modern European history has consistently displayed (ultra)nationalist tendencies, nativism, chauvinism and xenophobia, all elements of extreme support for the national in-group.

Empirical evidence supports this hypothesis, showing that communities most affected by war tend to disproportionately support far-right political parties or otherwise exhibit behavioural patterns congruent with far-right ideology. Acemoglu et al. (Reference Acemoglu, De Feo, De Luca and Russo2022) show that variation in the number of casualties inflicted on the Italian army during WWI was a major factor in the rise of fascism in some regions of the country. Similarly, Koenig (Reference Koenig2023) shows that German regions with more WWI veterans gradually moved to the right of the political spectrum, supporting conservative parties that enabled the erosion of democracy and the rise of the Nazi Party. Providing even more direct evidence of the link between WWI and Nazism, De Juan et al. (Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2021) s show that in the interwar period, support for nationalist parties was significantly higher in places with above-average wartime human losses. Finally, Cagé et al. (Reference Cagé, Dagorret, Grosjean and Jha2023) find that French communes that were more strongly represented during the Battle of Verdun, led by WWI hero and future leader of Vichy France, General Pétain, also had higher levels of Nazi collaboration during the German occupation of World War II.

But how do far-right parties manage to frame the experience of war in terms of national identity at the expense of a more localised imagined collective (e.g. the commune), given that local communities within the same country experience war very differently, but the national experience is homogeneous? Kocher, Lawrence, and Monteiro (Reference Kocher, Lawrence and Monteiro2018), building on the historical work of Keith (Reference Keith2013), suggest that the answer lies in the way modern states preserve the memory of war. When societies rely on a compulsory system of public education, children are exposed to a common national curriculum that includes the creation of a single image of collective trauma, thus producing the national in-group. This is not to say that the far-right manipulates the education system in order to weaponise the memory of the war, but that it indirectly benefits from the fact that the curriculum construes a shared experience at the national level, which reinforces the French people as the in-group towards which preferences are generated.

However, inter-community local differences are not erased by the school system, but become sources of variation in the perceived salience of the national trauma, rather than sources of variation in the form of the trauma. In short, French departments exposed to more wartime losses are more likely to have a strong attachment to the nationally defined in-group. All departments are affected by the memory of war, as the entire country was at war, but the intensity of this attachment is determined by local factors, such as the number of deaths or the extent of infrastructure destruction. This variation in the intensity of remembrance is also likely to persist because the practice of memory is endogenous to local institutions: political elites from departments more affected by the war are more likely to push for more stringent memorialisation and commemoration, thereby reinforcing the strength of the local narrative and thus the local preference for the in-group.

The lingering effects of shared war experiences

The remaining question is whether the in-group favouritism triggered by the shared experience of war within a community, which seem to translate into support for the far-right, persists over time, or whether the shock is transitory. At a more general level, the idea that significant historical conditions have long-term effects has gained traction in recent decades (Cirone and Pepinsky Reference Cirone and Pepinsky2022), but there is limited empirical evidence that wars constitute such a condition, most of it based on episodes of civil war rather than interstate violence. There is no a priori reason to believe that interstate violence would necessarily deviate from the patterns established in civil wars, but in the absence of explicit evidence we are faced with a gap, and need to rely on the literature on the persistent effects of civil wars.

In this sense, Costalli and Ruggeri (Reference Costalli and Ruggeri2019) argue that civil unrest changed the electoral geography of Italy by 1960, increasing the organisational capacity of the Italian Communist Party in the very same regions where Communists had fought against Nazi and Fascist forces during WW2. Drawing on the Spanish Civil War, Villamil (Reference Villamil2021) shows that regions where clandestine leftist networks operated during the war and were exposed to state-sponsored atrocities show higher levels of support for leftist parties in the long term. Finally, Rozenas, Schutte, and Zhukov (Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017), s who examine the long-term effects of Stalinist deportations in 1930s Ukraine, show that communities exposed to such atrocities are systematically less likely to support pro-Russian parties.

Theoretically, for war to be a critical juncture in the evolution of a society’s political equilibria, two necessary conditions must be met. First, there must be a causal mechanism, embedded in the socio-political context, through which the lasting effect of the war propagates. Second, there must be a political actor who becomes a mnemonic entrepreneur, willing to exploit the memory of war to activate the latent in-group preferences for electoral purposes. More specifically, we would need to identify an entity that directly benefits from the association between in-group preferences and nationalism, most likely by emphasising the latter as part of its political strategy. When both elements are present, the mechanism of persistence becomes clear: an interested political actor, who is a supplier of nationalism within the political system, leverages the infrastructure of collective memory to activate the community’s latent preference for in-group members, which translates into an increased demand for nationalism.

The first consideration, then, is what is the infrastructure through which the memory of war is propagated. A large body of work in sociology, anthropology and international relations explores precisely the politics of memory – how societies maintain, reproduce and instrumentalise shared experiences, such as wars (Malinova Reference Malinova2021; Maurantonio Reference Maurantonio2014; Müller Reference Müller2002; Uhl and Golsan Reference Uhl and Golsan2006). The politics of memory are the central link between war as a lived experience and war as a source of enduring nationalistic sentiments.

The starting point for making this connection is to recognise that nationalism, both as an ideology and as a form of political praxis, is rooted in the development of historical representations of shared narratives (Bell Reference Bell2003). But not all historical narratives are created equal. Central to the formation of the most enduring narratives of nationalism are episodes of collective trauma that trigger a social response of sufficient magnitude to construct and reinforce a common sense of belonging (Bell Reference Bell2006; Edkins Reference Edkins2003). Wars, especially the World Wars, are the epitome of such trauma, and there is empirical evidence of a link between wars, including WWI, and displays of nationalism (Cagé et al. Reference Cagé, Dagorret, Grosjean and Jha2023; De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2021).

This sense of nationalism, built on the foundations of shared historical experiences such as war, is reinforced and reproduced through the practice of memory. This practice is especially pronounced in Western democracies in relation to large-scale events such as the World Wars. To avoid repeating the mass violence that marked their history in the first half of the

![]() ${20^{th}}$

century, countries across Europe created multiple channels through which citizens could learn, mourn and remember what did not need to be repeated. Remembrance has become an integral part of the social fabric of politics, an essential cog in the nation-building machine (Turner Reference Turner2006). This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in France, where it has been at work since the interwar period (Sherman Reference Sherman1999). Visual reminders, including monuments, statues and cemeteries, are found throughout these countries and there are very few communities without any of them (Borghi Reference Borghi2021), ensuring access to political memory and, from the perspective of memory entrepreneurs, access to sources of identity (re)formation. Complementing these visual queues, school curricula try to explain the meaning of the World Wars and the connection between them in order to give children a sense of French historical completeness, a foundation of nationalism (Shapiro Reference Shapiro1997).

${20^{th}}$

century, countries across Europe created multiple channels through which citizens could learn, mourn and remember what did not need to be repeated. Remembrance has become an integral part of the social fabric of politics, an essential cog in the nation-building machine (Turner Reference Turner2006). This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in France, where it has been at work since the interwar period (Sherman Reference Sherman1999). Visual reminders, including monuments, statues and cemeteries, are found throughout these countries and there are very few communities without any of them (Borghi Reference Borghi2021), ensuring access to political memory and, from the perspective of memory entrepreneurs, access to sources of identity (re)formation. Complementing these visual queues, school curricula try to explain the meaning of the World Wars and the connection between them in order to give children a sense of French historical completeness, a foundation of nationalism (Shapiro Reference Shapiro1997).

The politics of memory provide a plausible infrastructure for how the memory of war could have proliferated in direct relation to nationalist attitudes. The next consideration is which actors would be interested in exploiting this infrastructure. Theoretically, we would need to identify an agent who would win from this action, and who has the organisational power to perform it. The latter condition is more important because it limits the class of actors to be analysed to those most relevant in the political system, which for the time being remain the political parties. In fact, many studies show that political parties and their leaders are among the most important mnemonic actors, as they tend to take on the role of memory entrepreneurs whenever political remembrance suits them (Korycki Reference Korycki2023). Among them, far-right political parties, such as the FN in France, mobilise precisely that part of war trauma that resonates with their target electorate, constructing an out-group by othering another country, a domestic political elite, an ethnic group or immigrants from a distant nation (Couperus, Tortola, and Rensmann Reference Couperus, Tortola and Rensmann2022; Couperus, Rensmann, and Tortola Reference Couperus, Rensmann and Tortola2023; Soffer Reference Soffer2022; Zavatti Reference Zavatti2021). In particular, French patriotism and the homogeneity of national identity, to which the far-right has appealed over the years, are closely linked to the wartime mobilisation of WWI (Purseigle Reference Purseigle2023; Smith, Audoin-Rouzeau, and Becker Reference Smith, Audoin-Rouzeau and Becker2003). Nationalism as an all-encompassing category, sometimes in exclusionary forms, was consolidated in France during this period (Fuller Reference Fuller2014; Tombs Reference Tombs2003).

Simply put, the memory of war losses can trigger nationalist tendencies that increase the electoral standing of the far-right, the main proponent of exclusionary nationalism in contemporary politics.

In addition, the losses of WWI could be perceived as the French state sending its citizens to a certain death, creating an environment of mistrust. Mistrust is one of the most persistent narratives in societies, passed on from generation to generation (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Boeckh, Hainz and Woessmann2016; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017). In the long run, accumulated mistrust benefits the far-right (Berning and Ziller Reference Berning and Ziller2017), which is able to portray itself as creating a rupture with the status quo and the remaining institutions against which people are hostile, weaponising not only the memory of war but the cynicism towards formal institutions that this memory engendersFootnote 2 .

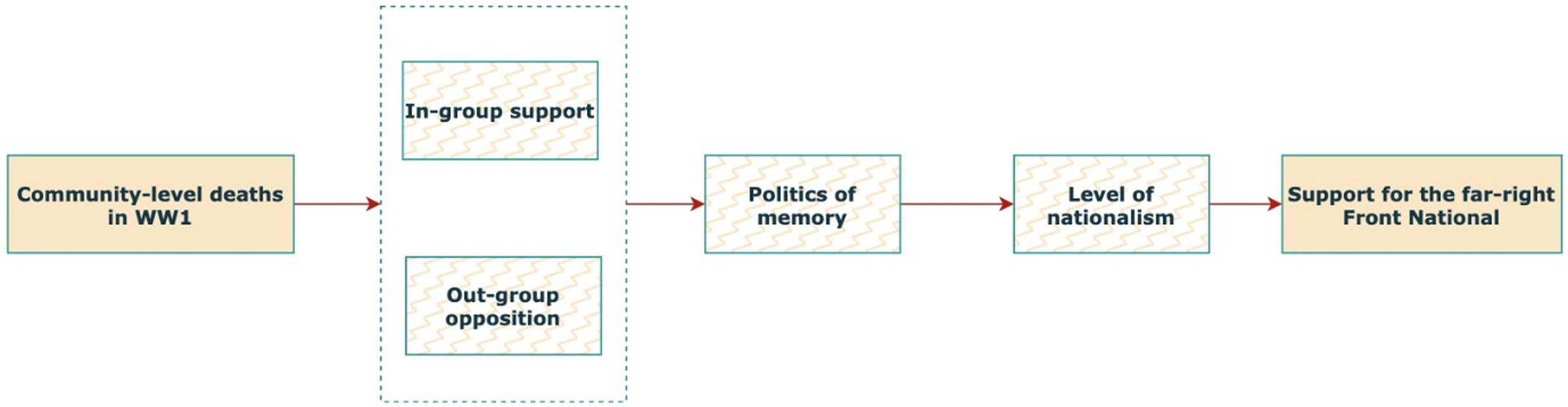

We therefore have both the infrastructure and the political actors who could use it. On the basis of these theoretical considerations, as applied to the case of France post-WWI, I propose the following argument. The deaths experienced by local communities during WWI increased in-group preferences which, in the case of France, manifest themselves as preferences for the French nation, i.e. nationalism. Moreover, because different death rates act as triggers of different intensity, they produce shifts in in-group preferences of different magnitude and hence differential demand for nationalism. Since far-right parties are the main suppliers of political nationalism, both in terms of discourse and policy, I expect that the demand for nationalism will in turn increase the electoral appeal of such political forces. Given that since the interwar period, far-right movements and parties have instrumentalised the memory of the war to consolidate their position and justify their (ultra)nationalist positions (Cagé et al. Reference Cagé, Dagorret, Grosjean and Jha2023), I hypothesise that support for the far-right is persistently higher in French departments where the death rate during WWI was higher. As the main far-right party in France, I expect the main beneficiary of this effect to be the FNFootnote 3 . A visual summary of the argument can be seen below, in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visual summary of the theoretical argument.

The argument is not to say that economic factors do not shape patterns of support for the far-right in France, or even to deny that they may be a central cause. Recent literature has shown that economic and cultural factors work in concert to favour the far-right when the circumstances are right for this type of actor (Margalit Reference Margalit2019; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2021; Scheiring et al. Reference Scheiring, Serrano-Alarcón, Moise, McNamara and Stuckler2024) Moreover, it could also be the case that the deaths of WWI shaped the deindustrialisation trajectory of the French departments, further reinforcing the effect of weaponising the memory of loss. This is especially likely given the strong correlation between death rates and the industrial profile of each French departments (Gay and Grosjean Reference Gay and Grosjean2023), as well as the long-term effect of WWI on the French labour market (Gay Reference Gay2023). My argument does not contradict claims of such additional reinforcing mechanisms; the more modest claim is that deaths during WWI are a contributing, persistent factor in inducing support for the FN. Future work should consider whether far-right political parties, which weaponise deeply rooted community norms about culture, are more successful in their efforts where there are appropriate economic circumstances. In other words, while cultural practices may be a sufficient condition for the success of the far-right, specific economic circumstances may be a necessary condition.

Research design

Data

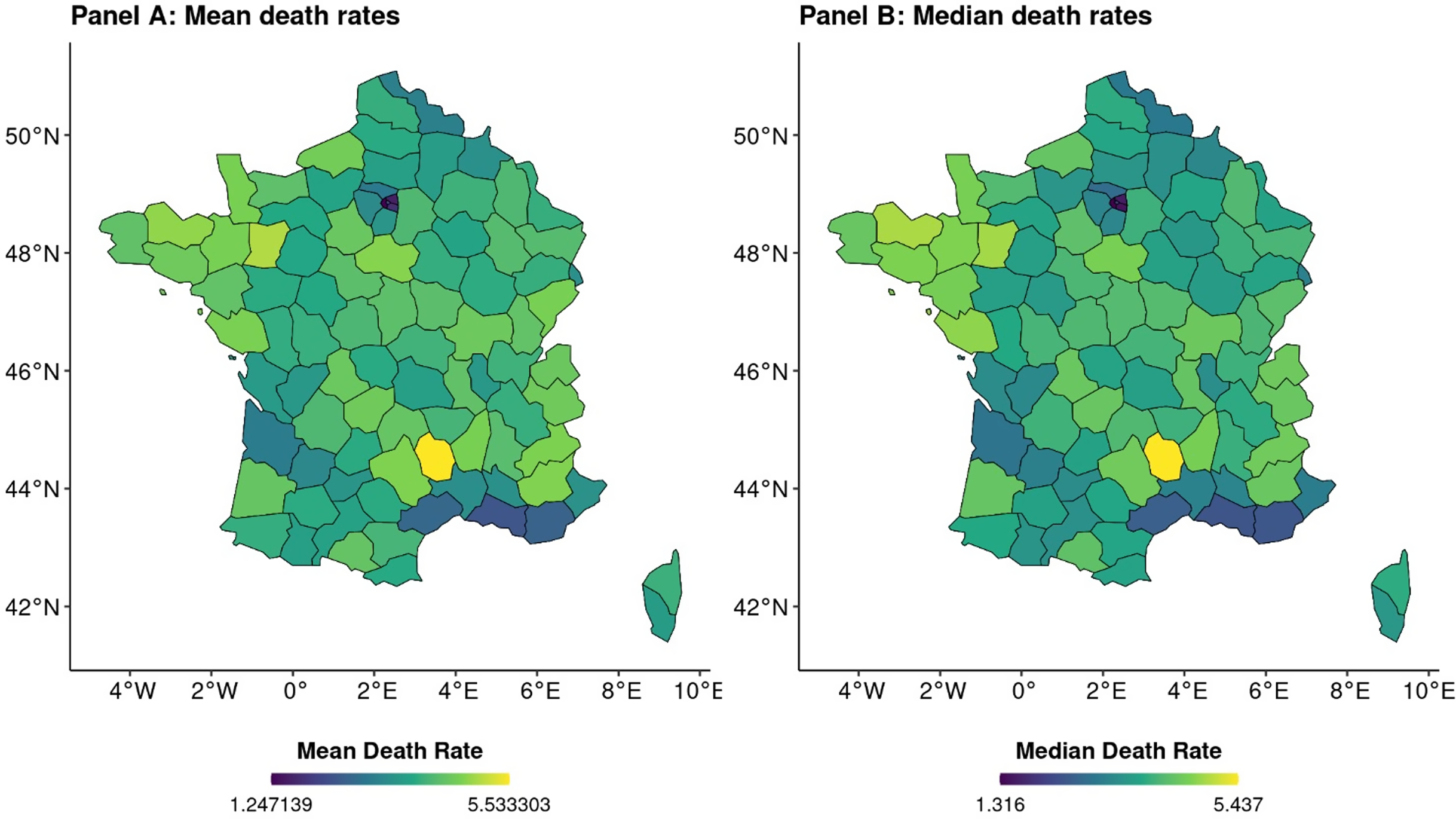

My main independent variable is the department-level death rate in WWI, calculated as the ratio between the number of deceased French soldiers born in a department and that department’s total population according to the 1911 census, the last before the start of war. I get these from the Morts Pour la France database, compiled by Gay and Grosjean (Reference Gay and Grosjean2023), s which is based on over 1.5 million individual files from the archives of the Bureau of Archives of Victims of Contemporary Conflicts. The average department-level death rate in France during WWI was 3.89% of the population, with a standard deviation of 0.7. The department with the highest death rate was in Lozère, with 5.53%, while the department with the lowest death rate was Hauts-de-Seine with 1.25%. Alternatively, I also calculate the median death rate in each department as a function of the number of deaths in French communes, in order to deal with the risk of outliers. Figure 2 visually displays the distribution of deaths across the French territory. In the online Appendix, Figure B1 shows histograms of the distribution of death rates across the French departments, demonstrating that (a) there is significant spatial variation that is not visibly clustered, and (b) the two operationalisations of the independent variable exploit different variations and are thus complementary.

Figure 2. Map of WWI death rates across French municipalities.

In terms of dependent variables, I leverage various measures of contemporary support for the far-right in France. For the main analysis, I measure the share of votes received by FN in national legislative elections since 1990Footnote 4 . I use data from the European NUTS-level dataset (EU-NED), which allows for a smooth matching based on the spatial characteristics of French departments (Schraff, Vergioglou, and Demirci Reference Schraff, Vergioglou and Demirci2023)Footnote 5 . In terms of scope conditions, I only look at post-1990 elections for three reasonsFootnote 6 .

First, while the FN’s consolidation began with the 1986 legislative elections (DeClair Reference DeClair1999; Shields Reference Shields2007), their remarkable results were due to an atypical electoral system for France, proportional representation, which had been implemented by François Mitterrand to cushion the expected defeat of his party (Knapp Reference Knapp1987). To understand the long-term electoral fortunes of the contemporary French far-right, it is necessary to exclude this particular outlier from the analysis. Second, French politics, traditionally more dominated by far-left parties than other West European party systems, changed markedly with the fall of the USSR (Bull Reference Bull1995). Looking for patterns of far-right support after 1990 thus allows to disentangle the complex effects of the Cold War as an external driver of political behaviour and to focus on domestic factors. Third, this period corresponds to a more modern version of the French party system, which is of primary interest in deciphering contemporary political events (Bornschier and Lachat Reference Bornschier and Lachat2009). In the online Appendix, I show that using all electoral results from 1986 onwards does not affect the results.

To avoid any ecological fallacy, I also examine support for the FN at the individual level. For this, I use the Sub-national Context and Radical Right Support in Europe (SCORE) survey (Evans and Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2021), which provides a nationally representative sample of 19,454 French respondents and a series of relevant questions, such as (1) whether they voted for Marine Le Pen in the first round of the 2017 presidential election, or (2) how they rate the FN on a Likert scaleFootnote 7 .

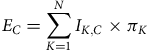

Finally, to verify my main argument on the mechanisms of support for the far-right, I construct additional dependent variables that capture not only the shift in revealed electoral preferences (i.e. explicit support for the FN), but also the electoral distribution around certain salient conflicts of the multidimensional French political space. Formally,

![]() $X = \left\{ {{X_1},{X_2},{X_3}, \ldots, {X_N}} \right\}$

is the set of political parties participating in each given election in France. Each party

$X = \left\{ {{X_1},{X_2},{X_3}, \ldots, {X_N}} \right\}$

is the set of political parties participating in each given election in France. Each party

![]() ${X_K} \in X$

has an ideological position

${X_K} \in X$

has an ideological position

![]() ${I_{K,C}}$

for every political conflict

${I_{K,C}}$

for every political conflict

![]() $C$

(e.g. taxation, nationalism, agriculture, etc.). The positions are measured before the election, and subsequently we measure the electoral performance of all parties through the vote share

$C$

(e.g. taxation, nationalism, agriculture, etc.). The positions are measured before the election, and subsequently we measure the electoral performance of all parties through the vote share

![]() ${{\rm{\pi }}_K}$

that they have obtained in the first election after revealing their ideological position

${{\rm{\pi }}_K}$

that they have obtained in the first election after revealing their ideological position

![]() ${I_{K,C}}$

. With this information, I compute

${I_{K,C}}$

. With this information, I compute

![]() ${E_C}$

, the political conflict equilibrium over each conflict

${E_C}$

, the political conflict equilibrium over each conflict

![]() $C$

:

$C$

:

$${E_C} = \mathop \sum \limits_{K = 1}^N {I_{K,C}} \times {{\rm{\pi }}_K}$$

$${E_C} = \mathop \sum \limits_{K = 1}^N {I_{K,C}} \times {{\rm{\pi }}_K}$$

The political conflict equilibriumFootnote

8

, as a measure, satisfies a number of intuitive conditions that one would expect from any metric of the central tendency of electoral preferences. First, it aggregates individual party positions based on their electoral performance. This means that it takes into account the preferences of the majority of the electorate. If a party with a particular position

![]() ${I_{K,C}}$

wins a significant share of the vote, that position will have a greater impact on

${I_{K,C}}$

wins a significant share of the vote, that position will have a greater impact on

![]() ${E_C}$

. However, smaller parties with extreme positions won’t disproportionately affect the equilibrium unless they win a significant share of the vote

${E_C}$

. However, smaller parties with extreme positions won’t disproportionately affect the equilibrium unless they win a significant share of the vote

![]() ${\pi _K}$

. In other words, it summarises the average preference of the voters for different ideological propositions supplied by the parties.

${\pi _K}$

. In other words, it summarises the average preference of the voters for different ideological propositions supplied by the parties.

Second, the political conflict equilibrium varies as parties’ ideological positions or electoral performance change from election to election. This is important because it allows the measure to adapt and reflect changing political landscapes or evolving voter preferences over time. Furthermore,

![]() ${E_C}$

varies not only across elections but also across space, as different electoral constituencies produce different weights for the ideological positions of political parties due to the different vote shares obtained by the parties across electoral constituencies, making this measure also suitable for sub-national analysis, like in the case of this paper.

${E_C}$

varies not only across elections but also across space, as different electoral constituencies produce different weights for the ideological positions of political parties due to the different vote shares obtained by the parties across electoral constituencies, making this measure also suitable for sub-national analysis, like in the case of this paper.

Third,

![]() ${E_C}$

does not inherently favour party systems with more or fewer parties, important in the case of the ever-changing French system. While the number of terms in the sum depends on the number of parties

${E_C}$

does not inherently favour party systems with more or fewer parties, important in the case of the ever-changing French system. While the number of terms in the sum depends on the number of parties

![]() $N$

, the weight of each term is determined by the party’s vote share

$N$

, the weight of each term is determined by the party’s vote share

![]() ${\pi _{{X_i}}}$

. This further ensures that

${\pi _{{X_i}}}$

. This further ensures that

![]() ${E_C}$

can be used to compare political equilibria over time, regardless of the exact number of parties positioning themselves on different political conflicts.

${E_C}$

can be used to compare political equilibria over time, regardless of the exact number of parties positioning themselves on different political conflicts.

Simply put, I construct such political conflict equilibria as the weighted average of the policy positions endorsed by political parties before an election, where the weights are given by the share of votes each party received in the immediate election after the formal policy endorsements were made public. While the main dependent variable used in this paper captures explicit support for the far-right, the political conflict equilibria provide corroborating evidence for my theory, as they measure whether the entire political space has gravitated towards the positions endorsed by the far-right, and whether these changes are (partly) driven by WWI.

I calculate political conflict equilibria for conflicts relevant to far-right parties: multiculturalism, nationalism, traditionalism, internationalism, Europeanism, and the unidimensional right-left index. In terms of data, I rely on EU-NED for department-level vote shares obtained by French political parties, and on the Manifesto Project dataset (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Burst, Matthieß, Regel, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2022) for measures of party positions on the issues of interest. Following established trends in the text-as-data literature, I use the log transformation proposed by Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) to scale political preferences from coded political texts.

Model specification

I estimate the following regression:

![]() ${Y_{t,d}}$

is the vote share obtained by the FN in department

${Y_{t,d}}$

is the vote share obtained by the FN in department

![]() $d$

during election

$d$

during election

![]() $t$

;

$t$

;

![]() ${\rm{yea}}{{\rm{r}}_t}$

and

${\rm{yea}}{{\rm{r}}_t}$

and

![]() ${\rm{grid}} - {\rm{cel}}{{\rm{l}}_s}$

are year-fixed and grid-cell-fixed effects, respectively, which absorb the impact of time-invariant and region-invariant features of departments;

${\rm{grid}} - {\rm{cel}}{{\rm{l}}_s}$

are year-fixed and grid-cell-fixed effects, respectively, which absorb the impact of time-invariant and region-invariant features of departments;

![]() $\phi '{G_d}$

describes a set of spatial covariates, including the degree of urbanisation of a department, as well as whether the department is predominantly coastal or mountainous;

$\phi '{G_d}$

describes a set of spatial covariates, including the degree of urbanisation of a department, as well as whether the department is predominantly coastal or mountainous;

![]() $X$

are the respective Moran eigenvectors of the grid; the main coefficient of interest is

$X$

are the respective Moran eigenvectors of the grid; the main coefficient of interest is

![]() $\gamma $

, which measures the difference in vote share between departments induced by differential WWI death rates;

$\gamma $

, which measures the difference in vote share between departments induced by differential WWI death rates;

![]() ${\varepsilon _{t,d}}$

is the error term.

${\varepsilon _{t,d}}$

is the error term.

The necessary condition for

![]() $\gamma $

to represent a causal effect is that WWI death rates are not determined by factors that also determine contemporary support for the FNFootnote

9

. In the language of natural experiments, the “assignment mechanism” of the WWI death rates needs to be as-if-random, which would ensure that the departments are, in expectation, homogeneous in terms of pre-WWI characteristics (Kocher and Monteiro Reference Kocher and Monteiro2016, p. 954). However, validating the as-if-random assumption is beyond the scope of statistical testing, as it requires knowledge not only of the distribution of observable characteristics of French departments at the onset of WWI, but also of unobservable characteristics. Instead, we need to reconstruct the process through which departments were ’assigned’ a particular death rate during WWI, and if certain factors are found to systematically influence the assignment, which might also shape political preferences, we need to control for them.

$\gamma $

to represent a causal effect is that WWI death rates are not determined by factors that also determine contemporary support for the FNFootnote

9

. In the language of natural experiments, the “assignment mechanism” of the WWI death rates needs to be as-if-random, which would ensure that the departments are, in expectation, homogeneous in terms of pre-WWI characteristics (Kocher and Monteiro Reference Kocher and Monteiro2016, p. 954). However, validating the as-if-random assumption is beyond the scope of statistical testing, as it requires knowledge not only of the distribution of observable characteristics of French departments at the onset of WWI, but also of unobservable characteristics. Instead, we need to reconstruct the process through which departments were ’assigned’ a particular death rate during WWI, and if certain factors are found to systematically influence the assignment, which might also shape political preferences, we need to control for them.

Fortunately, the question of what factors best explain the differences in rates between departments is not a new one for historians. There is a large body of literature on how the French army conducted its military operations between 1914 and 1919 and on the factors that determined battlefield mortality (Greenhalgh Reference Greenhalgh2014; Porch Reference Porch1988; Prete Reference Prete1985). In a nutshell, death rates are a function of the shifting territorial priorities of the war effort, which can be broken down into three elements: recruitment patterns, troop deployment and battle strategy. The latter is plausibly unrelated to the political preferences of the citizens of the French departments, so only the first two must be examined.

In the beginning, citizens recruited from the same department were usually sent to the same front, ensuring a fairly homogeneous distribution of deaths as combat situations became more dispersed. As the war of attrition progressed, people from all corners of France were sent precisely when and where they were most needed, regardless of their cohort, socio-demographic characteristics or department of origin. From that point on, death rate heterogeneity was determined by how the French authorities decided to respond to the industrial needs of their war machine, to the disruptions caused by the German occupation of the north-east, and to the shortages of artillery weapons in the early stages of the conflict (Bostrom Reference Bostrom2016). Naturally, the more urban departments, where citizens were equipped with skills more suited to industrial work, became the primary sources for compensating for production shortfalls. Accordingly, as demonstrated by Gay and Grosjean (Reference Gay and Grosjean2023), the strongest predictor of death rates among the population of a department is the degree of urbanisation of that department: the more urbanised, the lower the death rate. In fact, the degree of urbanisation explains over 75% of the variation in death rates between French departments, and once urbanisation is taken into account, other socio-demographic or geographical characteristics do not significantly improve the predictive power. This is crucial because it implies that pre-WW1 political and demographic differences between departments cannot explain the main independent variable; even if they are related to the dependent variable, they are not confounders by construction and their inclusion in the regression is not necessary, but should be avoided (Cinelli, Forney, and Pearl Reference Cinelli, Forney and Pearl2022).

Thus, while mortality is not distributed as-if-randomly, once the effect of urbanisation is taken into account, we could treat the distribution of World War I mortality rates as a quasi-natural experiment (DiNardo Reference DiNardo2010). However, as the relationship I am investigating occurs in the long run, with several other events taking place, including another World War, we need to be wary of spatial noise that might capture alternative causal channels (Kelly Reference Kelly2020). I carry out the adjustment protocol that alleviates concerns over alternative explanations in two steps.

First, I control for the degree of urbanisation

![]() ${G_d}$

of each French department using spatial data collected by the European Commission’s Geographic Information System (GISCO). In addition, to improve robustness and decrease uncertainty in the estimates, I include Moran eigenvectors in the regression model; including these eigenvectors is a statistical technique that explicitly incorporates any spatial patterns predictive of the outcome into the regression model, thus avoiding the estimation being sensitive to spatial noise (Dray, Legendre, and Peres-Neto Reference Dray, Legendre and Peres-Neto2006; Griffith and Peres-Neto Reference Griffith and Peres-Neto2006). Thus, even if the effect of post-WWI events that took place in France is correlated with the effect of WWI on electoral options, the Moran eigenvectors remove these associations, leaving only the direct effect of interest. Then, I include polynomials in the latitude and longitude of the centroid of each department, which deal with potential spatial gradients. As suggested by Kelly (Reference Kelly2020), I control at least for

${G_d}$

of each French department using spatial data collected by the European Commission’s Geographic Information System (GISCO). In addition, to improve robustness and decrease uncertainty in the estimates, I include Moran eigenvectors in the regression model; including these eigenvectors is a statistical technique that explicitly incorporates any spatial patterns predictive of the outcome into the regression model, thus avoiding the estimation being sensitive to spatial noise (Dray, Legendre, and Peres-Neto Reference Dray, Legendre and Peres-Neto2006; Griffith and Peres-Neto Reference Griffith and Peres-Neto2006). Thus, even if the effect of post-WWI events that took place in France is correlated with the effect of WWI on electoral options, the Moran eigenvectors remove these associations, leaving only the direct effect of interest. Then, I include polynomials in the latitude and longitude of the centroid of each department, which deal with potential spatial gradients. As suggested by Kelly (Reference Kelly2020), I control at least for

![]() ${2^{nd}}$

degree polynomials, with and without interaction terms between coordinates, but not any higher degree to avoid over-fitting (Gelman and Imbens Reference Gelman and Imbens2019). I do not control for economic characteristics of the departments after WWI that might explain support for the FN, as these are post-treatment variables that potentially capture mechanisms through which WWI death rates induce patterns of support for the far-right. In this regard, I follow the advice of methodologists to avoid over-controlling just for the sake of it (Achen Reference Achen2005; Clarke Reference Clarke2005, Reference Clarke2009) and instead follow a theorised data-generating process (Hünermund, Louw, and Caspi Reference Hünermund, Louw and Caspi2023). In this paper, over-control would at best remove some of the effect, and at worst introduce collider bias (Elwert and Winship Reference Elwert and Winship2014).

${2^{nd}}$

degree polynomials, with and without interaction terms between coordinates, but not any higher degree to avoid over-fitting (Gelman and Imbens Reference Gelman and Imbens2019). I do not control for economic characteristics of the departments after WWI that might explain support for the FN, as these are post-treatment variables that potentially capture mechanisms through which WWI death rates induce patterns of support for the far-right. In this regard, I follow the advice of methodologists to avoid over-controlling just for the sake of it (Achen Reference Achen2005; Clarke Reference Clarke2005, Reference Clarke2009) and instead follow a theorised data-generating process (Hünermund, Louw, and Caspi Reference Hünermund, Louw and Caspi2023). In this paper, over-control would at best remove some of the effect, and at worst introduce collider bias (Elwert and Winship Reference Elwert and Winship2014).

Second, I reweight the observations in my dataset based on the degree of urbanisation and the Moran eigenvectors using entropy balancing (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012). Entropy balancing is a matching algorithm that calibrates the unit weights for the control group so that the specified sample moments of the covariate distribution (e.g. mean, variance, skewness) of the reweighted control group approximate those of the treatment group (Watson and Elliot Reference Watson and Elliot2016). This algorithm is doubly robust to linear regression, meaning that the causal effect of WWI death rates on contemporary support for the far-right is well identified if either one of the matching or regression models I use is correctly specified, even if the other is not (Zhao and Percival Reference Zhao and Percival2016).

To further reduce the threat of selection bias by restricting identifying variation to a more plausible subset of within-period and within-region variation, I add two sets of fixed effects (Mummolo and Peterson Reference Mummolo and Peterson2018). First, year-fixed effects, which I include because of election-specific political dynamics that should not be pooled during estimation. Second, grid-cell fixed effects, which, following the approach of Doucette (Reference Doucette2024), divide observations into spatial units along latitude and longitude and capture unobserved confounding related to the natural distribution of French departments in physical space. Grid-cell fixed effects divide the French map into dozens of rectangles of equal size, capturing all the structural elements specific to each region that have remained stable over time, including geography and baseline population characteristics. I avoid including administrative unit fixed effects, such as those based on NUTS2 units, because these were created after WWI based on decisions that are credibly related to the post-war economic situation, and could lead to over-control for post-treatment variables, a major threat in historical political economy (Homola, Pereira, and Tavits Reference Homola, Pereira and Tavits2024; Pepinsky, Goodman, and Ziller Reference Pepinsky, Goodman and Ziller2024a, Reference Pepinsky, Wallace Goodman and Ziller2024b). In the online Appendix, I show nevertheless that replacing grid-cell fixed effects with NUTS2 regional effects does not alter the results.

I report Conley standard errors, which are heteroskedastic and two-dimensional autocorrelation consistent (Conley and Molinari Reference Conley and Molinari2007)Footnote 10 .

Results and discussion

Main analysis

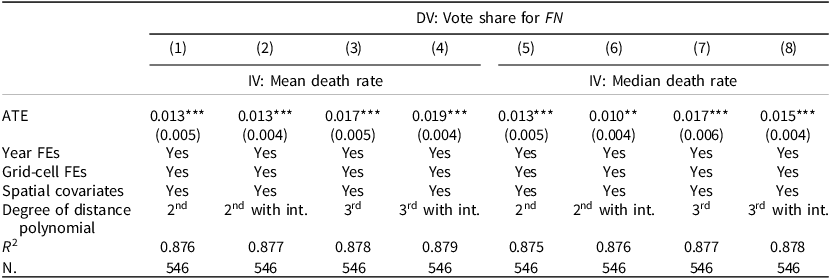

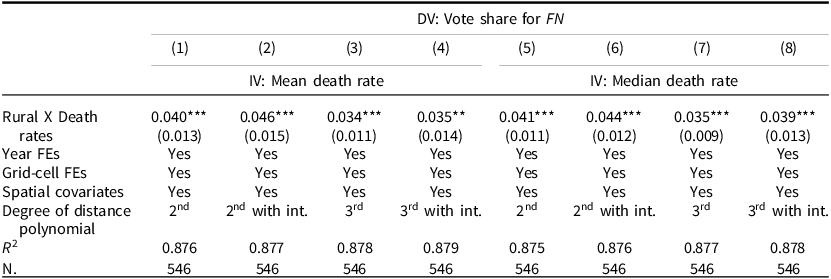

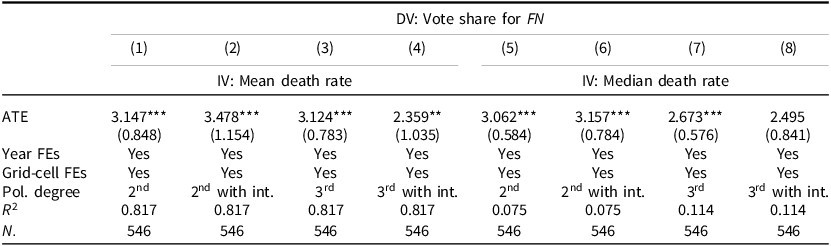

Table 1 reports the results of estimating Equation (2). Columns (1)–(4) use average WWI death rates at the department-level as the independent variable, while (5)–(8) use median death rates as a robustness check, as they are less susceptible to outlier communes within a department. The estimated effects are statistically significant at conventional levels, with the two-sided p < 0.05 (and, with one exception, p < 0.01), providing strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis that there is no effect of WWI death rates on support for the FN. Drawing on Columns (1)–(8), I find that an increase of 1 percentage point in WWI death rate in a French department predicts, on average, an increase of between 0.013 and 0.017 in the vote share of the FNFootnote 11 . Since FN’s average share in the period after 1990 was 11%, the difference caused by WWI represents 11.8–15.4% of this figure, making the estimates not only statistically significant, but also substantial in terms of magnitude Footnote 12,Footnote 13 .

Table 1. Effect of WWI death rate on support for FN (1993-2017)

*Conley standard errors in parentheses. The ***/**/* represent significance at the 0.01/0.05/0.10 levels, respectively.

To check the likelihood that spatial noise is driving the effect, I compute Moran’s I statistic, which measures the degree of spatial autocorrelation in the regression residuals (Kelly Reference Kelly2019). All eight values are close to zero, indicating that significant threats to validity from spatial autocorrelation have been addressed and that the results can be meaningfully interpreted. I also compute Geary’s C statistic, which is more sensitive to local spatial autocorrelation. For all model specifications, its value is close to 1, indicating randomness in the distribution of observations.

To test whether these results are driven by unobservable characteristics of the French departments before WWI, such as differential political preferences, I conduct several sensitivity analyses that explicitly ask how much unobservable characteristics should matter relative to observables in order to cancel out the effect (Cinelli and Hazlett Reference Cinelli and Hazlett2020; Oster Reference Oster2019). If results are not sensitive, then even if such differences exist, they would not affect my estimated model. Following Oster (Reference Oster2019), I show that the influence of unobservables would have to be 84–238% of that of observables to explain away the ATE, which is unlikely given the very high levels of

![]() ${R^2}$

in Columns (1)–(8) of Table 1. Similarly, following the approach developed by Cinelli and Hazlett (Reference Cinelli and Hazlett2020), I show that unobservables would have to explain 23.1–25.4% of the residual variance of both the independent and dependent variables, which is again logically possible but highly unlikely.

${R^2}$

in Columns (1)–(8) of Table 1. Similarly, following the approach developed by Cinelli and Hazlett (Reference Cinelli and Hazlett2020), I show that unobservables would have to explain 23.1–25.4% of the residual variance of both the independent and dependent variables, which is again logically possible but highly unlikely.

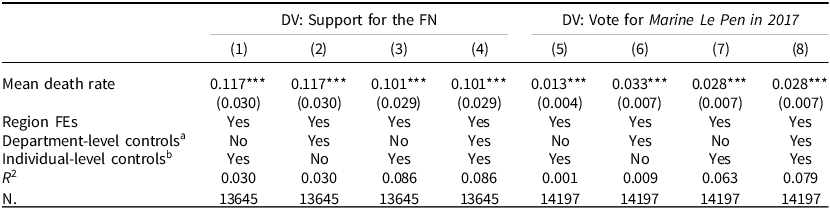

As a next step, I provide evidence of effect heterogeneity, i.e. the impact of WWI death rates on support for the far-right is not uniformly distributed across French departments. Based on my theoretical argument, one would expect that communities where the politics of memory are a more active part of social life would also be more affected by the FN’s politicisation of the practice of remembrance. While there are many potential sources of variation in how the politics of memory are enacted, one obvious candidate is the degree of urbanisation of a department. First, less urbanised departments tend to have a better grasp of local developments, as well as a better range of community organisations, including churches, that curate and cultivate the memory of loss. Second, people in less urbanised departments are more likely to have a strong attachment to family and kinship, and thus to react more strongly to losses that have occurred in their vicinity. Both points are aligned with my theoretical argument, and, hence, if my argument if correct, we should observe a stronger effect of WWI death rates in less urbanised, and therefore rural, communities. Formally, therefore, I test whether (lack of) urbanisation is a moderating variable by interacting the main independent variable with a categorical variable that precisely measures the degree of urbanisation in a region. Higher values of the rural variable indicate a lower degree of urbanisation in that department.

Table 2 reports the results of this estimation. For both mean and median death rates, the interaction term is positive and statistically different from zero at conventional confidence levels. This means that not only do higher death rates in WWI increase support for the far-right in France, but that the degree of support increases monotonically with the lack of urbanisation. Returning to theory, this finding could indicate that departments where memory is more thoroughly preserved are more affected by the lingering effects of such memories.

Table 2. Heterogeneous effects of WWI death rate on support for FN (1993-2017)

*Conley standard errors in parentheses. The ***/**/* represent significance at the 0.01/0.05/0.10 levels, respectively.

Next, I conduct the individual-level analysis using panel data from the SCORE survey. I regress two dependent variables measuring support for the far-right on the WWI death rate in a respondent’s department, as well as a set of socio-demographic and regional context control variables. Table 3 reports the estimates. Columns (1)–(4) report results on whether the death rate increases self-reported support for the FN, while Columns (5)–(8) report results on whether the same independent variable predicts and increases the likelihood that citizens will vote for Marine Le Pen, the leader of the FN, in the 2017 presidential election. For both dependent variables, the estimates are positive and statistically significant at p <0.01. The effect magnitude is robust to the inclusion of different sets of covariatesFootnote 14 .

Table 3. Individual-level effects of WWI death rates

*Robust standard errors in parentheses. The ***/**/* represent significance at the 0.01/0.05/0.10 levels, respectively.

a. I include the share of unemployment in the region, and the share of immigrants in the regional population. b. I include age, gender, education level.

Table 4 then provides individual-level evidence to support my theoretical argument and the proposed mechanism. Using data from the same representative SCOPE survey, I show that French citizens from departments with higher WWI death rates are less likely to interact with non-French immigrants, a finding already established in the literature (Evans and Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2021). The estimates in Columns (1)–(4) are statistically significant at conventional levels, including p < 0.01, have a sizeable magnitude, and the size of the effect is stable to the introduction of different sets of covariates. The relationship holds even after introducing regional FEs, suggesting that the reason for this positive association is not that some regions are by default more exposed to higher levels of immigration, as the variation used to recover the estimate comes from within each region. Consequently, it is more likely that individuals who are more likely to support in-group preferences because they come from regions that were historically exposed to a more brutal memory of violence during WWI will behave in a manner consistent with theoretical expectations: as in-group preferences translate into nationalistic attitudes, the latter reduce citizens’ willingness to interact with people from other nations/cultures/countries, such as immigrants.

Table 4. Effects of WWI death rates on contact with immigrants

*Robust standard errors in parentheses. The ***/**/* represent significance at the 0.01/0.05/0.10 levels, respectively.

Interestingly, in the online Appendix I show that WWI death rates are not a good predictor of whether interactions with immigrants, when they occur, are positive or negative (Table B1). This demonstrates that the weaponised memory of war losses reduces the willingness of individuals carrying this memory to engage with an out-group, but once they have done so, possibly due to actions beyond their control such as demographic shifts, their exclusionary preference dissipates.

Evidence from shifting political conflict equilibria

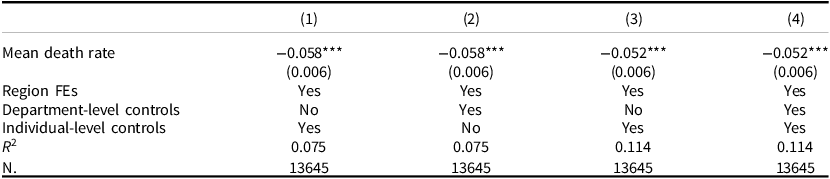

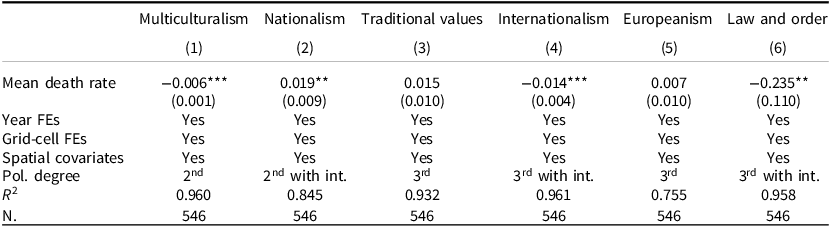

Since the main consideration derived from the theoretical argument is thoroughly supported by empirical evidence, I now proceed to provide evidence that WWI not only altered the final expression of electoral preferences, i.e. the vote for the FN, but also shaped the underlying political equilibria in French society. First, I re-estimate Equation (2) but change the dependent variable to the battery of political equilibria on nationalism, multiculturalism, traditional values, internationalism, and Europeanism. Table 5 reports the results of this estimation.

Table 5. Effect of WWI death rate on socio-political equilibria

*Conley standard errors in parentheses. The ***/**/* represent significance at the 0.01/0.05/0.10 levels, respectively.

The most direct test of my argument comes from Column (2), that is whether WWI death rates are positively associated with a higher nationalism equilibrium, i.e. whether the point at which social demand for nationalism meets the party system’s supply of nationalism is higher in departments that suffered more battlefield losses during WWI. The estimated effect for this channel is positive, substantial and statistically significant at the 5% confidence level. Columns (1), (3), and (5) complete the story of how the memory of the war was propagated in a manner favourable to the French far-right. The deaths in WWI triggered a psychological response in French citizens that led them to have a strong preference for the in-group (the French people). As Column (1) shows, over time this reduced the equilibrium level for multiculturalism, as department where the memory of the war was more activated (i.e. departments with more losses) became more suspicious of “outsiders.” This is corroborated by Column (4), as the equilibrium point for internationalism has decreased, suggesting that citizens are less likely to demand a French presence in multilateral international affairs from the political parties they support, a sign of self-imposed isolation.

Of course, a potential endogeneity threat arises from the fact that an electorally strong FN could have shaped these political conflicts. The question then becomes to what extent the political conflict equilibria are the result of such endogenous party dynamics, and to what extent they are caused by path-dependent historical causes. This question is beyond the scope of this paper and would require a model that predicts how well the FN’s standing influences other parties, similar to the work of Abou-Chadi and Krause (Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). What the current results show, however, is that the memory of the war has triggered a change in the level of these equilibria. It is very likely that the FN itself, by weaponising this historical loss for the French people, has changed its electoral programme precisely in terms of political conflicts such as nationalism or multiculturalism. In a sense, therefore, these results provide a mechanistic confirmation of the theoretical argument, without claiming that this is the only manifestation of the FN’s success.

The other two Columns act as placebo outcomes, confirming not only my empirical findings, but also the theory I put forward for their existence. In the historical political economy literature, it is often difficult to come up with meaningful placebos for causal inference because they must share a similar data-generating process with the main dependent variable, apart from the role of the independent variable under study (Eggers, Tuñón, and Dafoe Reference Eggers, Tuñón and Dafoe2023). In this case, the placebo outcomes are dependent variables traditionally associated with the far-right, but for which there is no reason to believe that there should be a positive effect of higher WWI death rates: Europeanism and Law & OrderFootnote 15 . The results in Column (5) are not statistically significant and change sign with the inclusion of different covariates, I can confirm that my model does not consistently yield a positive effect regardless of what the dependent variable is. This confirms that the reason for the association between deaths in the First World War and contemporary support for the far-right is theoretically grounded and not a random result of data noise. Column (6) brings an interesting challenge, as there seems to be a significant effect; one potential explanation, which should be further studied, is that a history of loss during war reduces support for political equilibria associated with militaristic regimes, including ’law and order’.

The final piece of empirical evidence comes from Table 6. If my theory is correct, then departments with higher death rates would have shifted towards more nationalist tendencies over time, which on the traditional unidimensional right-left (RILE) scale would imply a shift to the right. Columns (1)–(4) provide such empirical evidence by estimating Equation (2) with the RILE equilibrium level as the dependent variable. Irrespective of how I flexibly control for the geographical coordinates of a department, higher WWI death rates significantly lower the RILE equilibrium point, i.e. they make communities more right-wing. This result adds another link in the causal chain: higher WWI death rates increase in-group preferences, making people more right-wing, which in turn is reflected in lower community-level equilibria for political conflicts such as multiculturalism and internationalism, and higher for nationalism.

Table 6. Effects of WWI death rate on RILE equilibrium

*Conley standard errors in parentheses. The ***/**/* represent significance at the 0.01/0.05/0.10 levels, respectively.

Robustness checks

To verify the structural validity of my theorised causal model, I perform a series of robustness checks on the main results.

First, I show that the main specification of Equation (2) produces similar coefficients when removing the spatial covariates and relying only on entropy balancing for adjustment (Table A1). Removing the Moran eigenvectors from the specification preserves the sign of the results, but also significantly increases the degree of uncertainty in the estimates, which is to be expected given the large time lag between the initial historical conditions and the current results (Tables A2 and A3). However, the stability of the direction of the results suggests that the effect of WWI death rates is positively associated with support for the far-right, even if one were to dismiss the relationship as non-causal. The results remain positive and significant also when removing the weights produced through entropy balancing.

Second, I use an alternative independent variable, calculated as the residuals of the regression of death rates at the department level on the average death rates of all other departments within the same grid-cell, except for the one in cause. This approach ensure that if systematic unobservables connect the causes of combat losses and contemporary patterns of electoral support, then they are removed insofar as they are stable within the same area. Crucially, as grid-cells are defined in terms of geographical rather than administrative space, this method should remove threats that have had ’spillover’ across the same region of the country, regardless of whether that region coincides with the territorial unit to which a department belongs. The estimated effects, reported in Table A4 are positive, significant at p < 0.01 and support the results already established in Table 1.

Third, I show that the results are not sensitive to alternative preprocessing algorithms. While entropy balancing is doubly robust to linear regression, the more popular choice for reweighting in political science is propensity score matching. Accordingly, I show in Table A5 that the sign and size of the recovered effects are virtually unaffected when I correct for differences in the level of urbanisation across departments before 1914 using covariate balancing propensity score matching (Imai and Ratkovic Reference Imai and Ratkovic2014). The same applies to alternative methods of obtaining propensity scores, such as non-parametric covariate balancing propensity scores (Fong, Hazlett, and Imai Reference Fong, Hazlett and Imai2018) and propensity scores derived from generalised linear models (McCaffrey et al. Reference McCaffrey, Griffin, Almirall, Slaughter, Ramchand and Burgette2013) (Tables A6 and A7).

Discussion and conclusions

Does the experience of war have a lasting effect on the political behaviour of citizens? In this paper I show that the answer is yes, but not unconditionally. While French departments with higher death rates during WWI do indeed show greater support for the FN and its leader Marine Le Pen, this relationship is not automatic. In order for war to trigger in-group preferences that translate into support for the far-right, two conditions must be met. First, there needs to exist a strong physical and social infrastructure enabling the political remembrance of war memories. Second, there needs to exist a politically-motivated agent that is willing, able, and capable to exploit this infrastructure to achieve some sort of electoral goal. While both conditions are met in the case of post-WWI France, there is no guarantee that these results will generalise to different contexts where the politics of memory are less embedded in social life, or where far-right political parties have less access to sufficient organisational and logistical resources.

Nevertheless, this paper has multiple implications for future research. Existing studies have largely focused on the transitory shocks to political beliefs, attitudes and behaviour induced by war. While the historical persistence literature has been criticised for making broad generalisations based on underdeveloped theory, this paper suggests that, given a sound theoretical framework and sufficient attention to the mechanisms that constitute the causal chain between historical conditions and contemporary outcomes, such studies can prove insightful. Future studies should therefore benefit from discussing, even if only briefly, whether the causal effects they claim to identify are of a short-term nature or whether they propagate over longer periods of time. This distinction is not only interesting, but could also provide stakeholders with the necessary knowledge to understand which events truly represent critical junctures in the development pathways of the society, equipping them with better tools to address the consequences of such events.

I have also shown that, in terms of political equilibria, the experience of war changes only those associated with in-group/out-group preferences. Crucially, although these lead to higher levels of support for the FN, they do not translate into acquiescence to all the political narratives promoted by this party. For example, there is no effect of WW1 death rates on the equilibrium point for Europeanism. This suggests that while far-right parties may manipulate the memory of the war to their own electoral advantage, the targeted segment of the population offers only conditional support to political conflicts that reflect their latent preferences, rather than dogmatically embracing all positions endorsed by the far-right. Future research should benefit from such a finding, allowing for a more nuanced discussion of why some people vote for the far-right; as this paper suggests, it may be due to a limited supply of parties that match latent preferences, rather than a primarily demand-driven phenomenon.

Crucially, this paper does not argue that nothing else happened in France after WWI, or that the WWI experience has a unique causal power that does not interlock with the consequences of political action after 1919. Massive political events, such as World War II or the end of the colonial empire, could potentially dilute or amplify the behavioural consequences of WWI, thus altering the magnitude of their joint effect. Instead, my main argument is that understanding contemporary political behaviour requires a careful study of the historical factors that have shaped people’s attitudes to politics. There may be several such critical junctures, and they may interact in complex ways. The more modest point I make in this paper, therefore, is that the memory of extreme political violence, such as the experience of war, is persistent, and investigating its persistence might lead us to discover new ways of studying electoral politics.

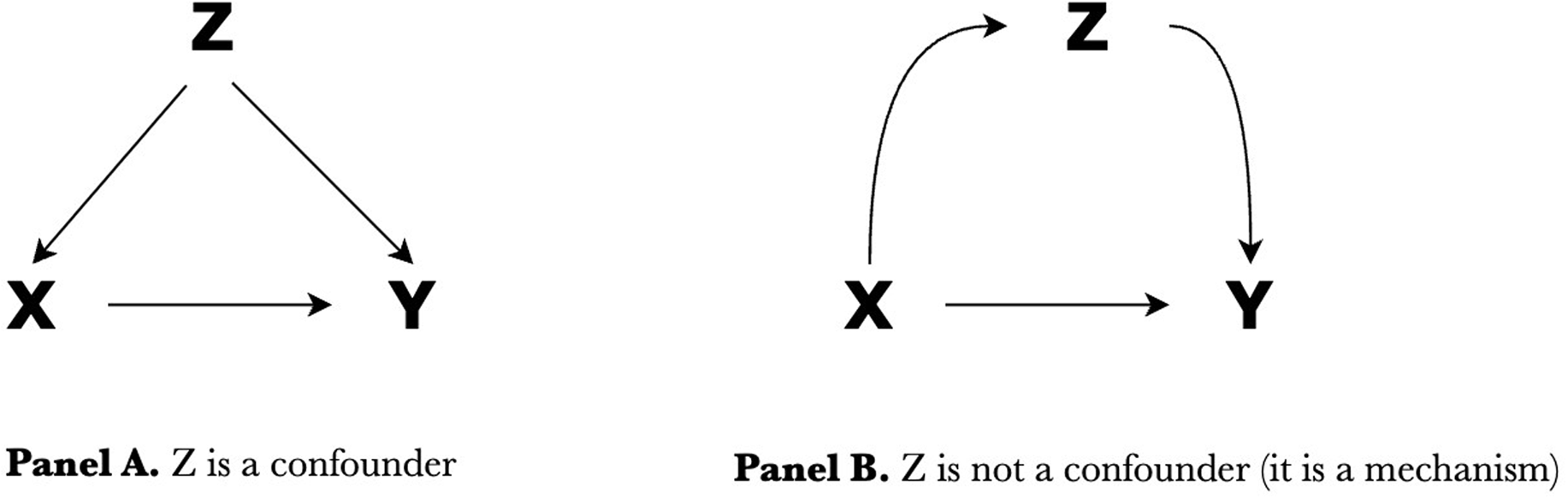

Notably, however, all events that occurred after the end of WWI, that influence support for the far-right in France, and that were (potentially) caused by WWI, are not confounders of the relationship examined in this paper. Such events, in order to confound, must be causes of both the independent and the dependent variable in order to invalidate the recovered effects due to omitted variable bias (Cinelli and Hazlett Reference Cinelli and Hazlett2020; Cinelli, Forney, and Pearl Reference Cinelli, Forney and Pearl2022; Steiner and Kim Reference Steiner and Kim2016); as long as they are on the path between the independent and the dependent variable, controlling for them would imply controlling for post-treatment effects, or in other words, removing part of the effect we are interested in estimating (Montgomery, Nyhan, and Torres Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018; Pearl Reference Pearl2015). Formally, adjusting in this scenario would be a form of over-control that would violate the back-door criterion (Pearl Reference Pearl2009; Pearl and Paz Reference Pearl and Paz2014). Figure 3 visually summarises this distinction, following Cinelli, Forney, and Pearl (Reference Cinelli, Forney and Pearl2022, pp. 8–9).

Figure 3. When to control for third variables, based on Cinelli, Forney, and Pearl (Reference Cinelli, Forney and Pearl2022).

In terms of interpreting the results, the role of WWII is much more important; by not controlling for WWII, the interpretation of the effects estimated in this paper is that of death rates in WWI on support for the far-right, potentially through the way in which WWI has shaped WWII, which in turn has shaped far-right electoral dynamics. Staying from the statistical language, another way of explaining this is that if we identify an effect of WWI death rates, and hypothesis that WWII also induced a causal effect on support for the far-right, the latter would be an indirect mechanism of the former, and not a parallel explanation. Such an ex-post mechanism (i.e. WWII) is crucial to understanding the unfolding of the causal trigger (i.e. WWI) and should not be removed unless the goal of the analysis is to identify some form of controlled direct effect, which is not the case in this paper as it would not be very well defined (Pearl Reference Pearl2022). Finally, even if we assume that WWI and WWII induced separate effects, controlling for the latter has no bearing on the magnitude of the former, being a neutral and not a good control in this unlikely scenario where the two wars are not related (Cinelli, Forney, and Pearl Reference Cinelli, Forney and Pearl2022, pp. 7–8).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773924000195.