In trying to investigate things which are above us and at present beyond our reach, we become so arrogant that we treat God like a book to be opened Footnote 1 and act as if we had already found the unfindable. (Irenaeus, Haer. 2.28.7)

Introduction

The scholarly debate over whether the apocalyptic genre Footnote 2 is a tangibly distinguished phenomenon or merely an artificial scholarly construct—with some even proposing “that the terms ‘apocalyptic’ and ‘apocalypticism’ be abandoned altogether” Footnote 3 —can be addressed in two possible ways.

The first has been widely applied. Writings considered apocalyptic are examined for a common set of features (mainly, but not exclusively, thematic) that are not only shared amongst themselves but also clearly differentiate them from other types of compositions. Footnote 4 For this method, an “apocalypse” is simply that which scholars can agree to call an “apocalypse” and “the classification ‘apocalyptic’ or ‘apocalypse’ is a modern one.” Footnote 5 The results of this approach, when applied impartially, do not always seem to be very favorable for the validity of the concept. It has even been noticed that “the ‘truly apocalyptic’ apocalypses are the exception rather than the rule,” and many patterns regarded as “apocalyptic” are in fact “not exclusive to the apocalypses.” Footnote 6 This critical challenge has been met by subsequent research that refines and clarifies the modern analytical approach to “the genre apocalypse” Footnote 7 and recognizes it as a Gestalt structure of dynamic nature and “blurred edges.” Footnote 8

A second approach would involve not an “objective” textual analysis from today’s perspective but rather an examination of the question of whether ancient authors and readers considered the apocalyptic corpus as something distinct. Footnote 9 On the one hand, the scholarly validity of this second approach would enjoy the fundamental advantage of reflecting an authentic historical viewpoint. This approach, in fact, is not just a means to refine genre classification as a convenience for modern critics but part of a historical inquiry amplifying our understanding of the research object. On the other hand, however, the cost of gaining such an authentic perspective would be a reliance on much scarcer extant data and on more or less convincing reconstructions.

The most instrumental evidence in this respect could be expected to come from usages of the very title “apocalypse.” Footnote 10 Indeed, we find this term used as a heading for many writings. Yet the dating of these titles represents a significant problem. Titles, by their very nature, are a paratextual phenomenon, more easily added or altered than other more integrated textual elements. Moreover, nearly all cases where the word appears as a title belong to either Christian writings or ones of dubious (either Jewish or Christian) provenance. Footnote 11 In any case, all of them are known from Christian transmission and could depend on the New Testament canon with its “Apocalypse” of John as a genre model.

Thus, from the wide usage of the title we can infer that at least late antique Christians did distinguish apocalyptic writings as a distinct corpus. It still remains to check on what basis they did so. One possible mode would be “writings similar to the Apocalypse of John,” Footnote 12 but whatever their basis may have been, they succeeded in passing on their perception to modern scholarship.

Yet what may be even more telling here is not the presence of the term but its absence. When we turn to earlier Jewish tradition, the situation becomes much more obscure. The absence of the title “apocalypse” from many early Jewish writings considered “apocalyptic” may be meaningful. Argumentum ad ignorantiam, inference from absence, however, is methodologically problematic. We know that “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” since some evidence may have been lost. Footnote 13 When such lost evidence can sometimes be more or less convincingly reconstructed, the method becomes even more problematic.

With this understanding in mind, in 2009 I published a short paper assembling arguments in favor of a reconstruction of the Hebrew term for “apocalypse” as gilayon (גליון). Footnote 14 In brief, my reconstruction was based on the following considerations. Most ancient translations interpreted biblical Hebrew gilayon as “book, scroll.” In rabbinic Hebrew this term could refer to different things in different sources; Footnote 15 one such meaning pertained to a specific kind of book, which may be defined as neither canonical (since the Tosefta says that הגליונים וספרי המינין אינן מטמאות את הידים “the gilyonim and the books of the heretics do not defile the hands”), nor heretical (since גליונים here are clearly distinguished from ספרי המינין “the books of heretics”; t. Yad. 2.13). Extra-canonical Footnote 16 apocalyptic writings are the best candidates for this category for at least four reasons: 1) the semantics of the term gilayon, which could be seen as derived not only from the Hebrew root gll “roll, fold, unfold” but also from gly/glh (or the Aramaic gl’) meaning “open, reveal,” and whose verbal form was often translated by the Greek ἀποκαλύπτειν; 2) the Syriac equivalent for Hebrew gilayon, gelyānā’/gelyōnā’ (ܓܠܝܢܐ/ܓܠܝܘܢܐ), often means “revelation, apocalypse”)including in the titles of apocalyptic writings); 3) this highly specialized Syriac term was most probably a Hebraism borrowed from the Jewish definition of some corpus of revealed literature (because its only meaning attested in Christian Syriac is “apocalypse,” and the form could hardly have been created in Syriac just for such a narrow usage); and finally, 4) the combination of the meanings “book” and “revelation” in one term made it a perfect expression for the title “book of revelation” and also for the concept of an otherworldly revealed book, central to many apocalyptic writings. Footnote 17

The claim I put forward in this paper is that the concept of gilayon “revealed book,” with all its meanings and allusions, was closely integrated both into the apocalyptic content and also into the Semitic languages of the early apocalyptic corpus. Even more importantly, it helps us to understand some very central imagery of early Jewish and Christian thought.

The connection between the meaning of the word gilayon and the content regularly found in the corpus of Jewish revealed literature seems so obvious that it is unclear how it could have been overlooked until now. This connection cannot but cause a noticeable shift in the system of our perception of apocalyptic motifs. Below I will dwell on the following implications of this reconstruction. The first and foremost is 1) actualization of the motif of the revealed book. This in turn would demand reevaluation of some other adjacent motifs, such as 2) open versus sealed books, 3) revealed versus secret books, 4) written versus oral teachings, 5) the place of the revealed book among other apocalyptic media, and finally, the connection between gilayon imagery and 6) messianic teachings, 7) terminology applied to and in early Christian writings, and 8) theologies of salvation.

Gilayon and its Attributes

A. Gilayon as “Revealed Book”

It is not only in titles where this notion of the revealed book appears. The combination of the two meanings of “book” and “revelation” in one term makes it the perfect expression not only for a “book of revelation” or a “revealed book” but also for the more complex concept of a revealed book of revelation found in many apocalyptic writings. Footnote 18

The book (scroll) imagery, often central for apocalyptic settings, may be connected to this double meaning. Such wordplay could follow the near universal topos of the celestial book(s) revealed, on the one hand, while also giving it a new impetus, on the other hand. This motif must be a variation of a wider concept of divine knowledge objectively existing in the upper realm and being potentially revealed to humankind. This concept was nearly universal for ancient thought, from Near Eastern myth to Platonic philosophy, but became especially prominent in the early Jewish worldview. Footnote 19

The demonstrating and unrolling or unsealing of the scroll occupy a central place in some prophetic and many apocalyptic narratives. In Isa 29:11–12 “the whole [prophetic] vision” (חזות הכל) is compared to “the words of the sealed book [scroll]” (דברי הספר החתום). In Ezek 2:9–3:3, revelation is accompanied by eating, “filling the belly” with the “sweet” celestial scroll (Heb. מגילה or מגילת ספר; Ezek 3:1–3); we find the same motif in Rev 10:9–10. In the Parables of Enoch, while receiving a revelation, the seer actually “received books of zeal and wrath as well as the books of haste and whirlwind” (1 En. 39:2).

The content of 1 Enoch alludes to Ezek 2:9–10, but its “books” are more than lists of eschatological woes: Enoch observes “books of the living” opened before God (Parables of Enoch 47:3). According to the Astronomical Book, he read “the tablets of heaven, all the writing, and came to understand everything … [he] reads the book of all the deeds of humanity and all the children of the flesh upon the earth for all the generations of the world” (81:1–2; cf. also Apocalypse of Weeks 93:1 and Epistle of Enoch 106:19). The destiny of the “sheep” (Israel) is also written in the book, read to the Lord, and sealed by him (Astronomical Book 81:67–77; Animal Apocalypse 90:20–21). Enoch, in turn, also writes his revelation down and transmits it in this form to his son: “I have revealed to you and given you the book about all these things …” (Astronomical Book 82:1; italics here and henceforth are mine). Enoch copies celestial books and writes down his visions in heaven also in 2 En. 22:11; 23:3; 33:2–10; and more.

The sealed scroll (βιβλίον) of Rev 5 has much in common with the Book of Ezekiel, as well as with 1 Enoch. When unsealed, it reveals visions of the eschatological future (Rev 6–8). Following Ezek 3:1–3, revelation and prophetic initiation in the Book of Revelation are accomplished through demonstrating and eating a celestial “little opened scroll” (βιβλαρίδιον ἠνεῳγμένον; Rev 10:2–11). The Shepherd of Hermas develops the same motifs (Herm. Vis. 1.2.2; 2.1.3–2.2.1; 2.4.2–3); see, for example, “I transcribed the whole of it [the book] letter by letter … the knowledge of the writing was revealed to me” (2.1.3–2.2.1). The Cologne Mani Codex of the fifth century CE also refers to (possibly alleged) “Apocalypses” of Adam, Sethel, Shem, Enosh, and Enoch, speaking about these texts as self-evidently written compositions: “[E]ach one of the forefathers showed his own apocalypse to his elect, which he chose and brought together in that generation in which he appeared, and how he wrote (it) and bequeathed (it) to posterity” (CMC 47.1–16; 62.9–63.7). Many more examples are provided in the following sections.This motif of a revealed heavenly book may be connected to the similar idea of heaven as a revealed book, as found in Isa 34:16: דרשו מעל־ספר ה׳ וקראו אחת מהנה לא נעדרה אשה רעותה לא פקדו כי־פי הוא צוה ורוחו הוא קבצן “Search from the book of the Lord and read: None of these will be missing, not one will lack her mate. For it is his mouth that has commanded it, and his spirit that has gathered them together.” Isa 34:4 even uses the verb from the same root as gilayon: ונמקו כל־צבא השמים ונגלו כספר השמים וכל־צבאם יבול כנבל עלה מגפן וכנבלת מתאנה: “All the host of heaven [= stars] will be dissolved and the heavens will be rolled up like a book [= scroll]. All their host will fall like withered leaves from the vine, like shriveled fruit from the fig tree.” In other words, here we find the idea that in the astrological world the very heavens are themselves a book, recording the human state and enabling him who “reads” them to reveal hidden knowledge. Footnote 20 Uranology played the central role in apocalyptic narratives, and the very image of heaven as a book (scroll) appears also in apocalyptic contexts: “the heavens receded like a scroll being rolled up” (Rev 6:14).

The popularity of the revealed book concept may stand behind its extension to the “book of the Torah,” understood not only as a book registering the teaching revealed to Moses (as in Exod 34:27; Deut 31:9 and 24; Josephus, Ant. 1.15–26; Jub. 1:5; 4 Ezra 14:4–6; etc.) but also as the actual, ready-shaped “book of teaching” revealed to him. The book could be given or shown or dictated to him in different forms as a whole (as in b. Giṭ. 60a: “the Torah was given complete” תורה חתומה ניתנה), or at least given in portions as a series of revealed books in different time periods (“the Torah was given scroll by scroll” תורה מגילה מגילה ניתנה). This revelation could even include an entire library:

R. Levi b. Hama said in the name of R. Shimon b. Laqish: “It is said in the Scripture: ‘And I will give you the tablets of stone, the Torah and the commandments, which I have written to teach them’ [Exod 24:12], meaning that the ‘tablets’ refer to the ten commandments, the ‘Torah’ to the Scripture [מקרא, here—Pentateuch], the ‘commandments’ to the Mishnah; ‘which I have written these’ to the books of Prophets and Writings; ‘to teach them’ to the Talmud. All these were given to Moses at Sinai.” (b. Ber. 5a)

However, there are recensions, possibly more authentic, where the “Scripture” is not mentioned at all and “Torah” is associated with tablets. Footnote 21 Similarly, Pseudo-Jonathan (eighth century CE or later) argues that both the written and oral Torahs were not given literally but only as the interpretive potential of the tablets: “I will give you the tablets of stone where the rest of the words of the Torah [שאר פתגמי אורייתא] and the six hundred and thirteen commandments, which I wrote for their instruction, are implied [רמוז]” (Tg. Ps.-J. Exod 24:12). Despite this, the idea of the integral nature of the giving of the Torah could possibly follow from the concept of the Torah’s preexistence (b. Zebaḥ. 116a; Gen. Rab. 1.1, 4; y. Šeqal. 5.15.49a). The revelation of the Torah in book form was never explicitly stated in pre-rabbinic sources, although some early Jewish traditions might bestow this status on other books given to Moses (Jub. 1:1; Temple Scroll 51.6–7). The idea of the Torah’s preexistence in book form might have been known to Sir 24:1 and 23 and Bar 3:37–4:1, which identify the celestial Wisdom not only with “the Law which Moses commanded us” but also with “the book of the covenant of the Most High God” (Sir 24:3) and “the book of the precepts of God” (Bar 4:1; on this, see more in the section “Revealed Book and Incarnated Word”).

B. Gilayon as “Open Book” versus Closed or Sealed Books

The meanings of “reveal, discover” Footnote 22 and “uncover, open” are equally expressed by the Semitic root gly/glh. This fact may be connected to a widely developed motif of opening (and unsealing) the celestial book.

There may also be a general semiotic/infralinguistic basis for the metaphor of the book as revelation. The book—and more especially the scroll, before the widespread introduction of codices—is by definition an object that must be uncovered and unrolled (or opened) in order to reveal its contents. Footnote 23

The opened celestial book (an unsealed and/or unrolled scroll) is a leitmotif of Revelation (see chapters 5–6; 10; 20; etc.) and is widely found applied to celestial books in other apocalyptic writings as well: “The [celestial] court sat in judgment, and books were opened” (וספרין פתיחו; Dan 7:10); “and the Lord of the sheep sat on it, and they took all the sealed books and opened those books before the Lord of the sheep” (Animal Apocalypse 90:20); “And in those days I saw the Head of Days sit down on the throne of his glory, and the books of the living (maṣāḥefta ḥeyāwān) were opened before him” (Parables of Enoch 47:3); “And the judge told one of the angels who served him, ‘Open this book for me and find for me the sins of this soul.’ And when he opened the book he found its sins and righteous deeds to be equally balanced” (T. Ab. A 12:17–18); “And that man opened one of the books which the cherubim had and sought out the sin of the woman’s soul, and he found (it). And the judge said, ‘Exhibit the sin of this soul.’ And, opening one of the books which were with the cherubim, he looked for the sin of the woman and found (it)” (T. Ab. B 10); “When the seal is placed upon the age that is about to pass away, then I will show these signs: the books shall be opened before the face of the firmament, and all shall see my judgment together” (4 Ezra 6:20); “For behold, the days are coming, and the books will be opened in which are written the sins of all those who have sinned” (2 Bar. 24:1); “one of the angels who was standing by, more glorious than that angel who had brought me up from the world, showed me (some) books [or “book” in Slavonic and Latin], but not like the books of this world; and he opened them, and the books had writing in them, but not like the books of this world” (Mart. Ascen. Isa. 9:20–21). Compare also “the books of the living ones were open before him” (Parables of Enoch 47:3, cited above) and “[The angels] read, they choose, they love … their codex is never closed, nor is their book ever folded shut. For you yourself are a book to them and you are ‘for eternity’ ” (legunt, eligunt, et diligent … non clauditur codex eorum nec plicatur liber eorum, quia tu ipse illis hoc es et es in aeternum; Augustine, Confessions 13.151). Footnote 24

These open or opening books are found in a natural dichotomy with closed, and especially sealed, books. In addition to Isa 29:11–12 cited above (דברי הספר החתום “the words of the sealed book”) and Rev 5–6 (βιβλίον … κατεσφραγισμένον σφραγῖσιν ἑπτά “a book … sealed with seven seals” in 5:1, together with the account of their subsequent opening, etc.), we may recall: “O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end” (Dan 12:4 and 9); “the Lord of the sheep sat on it [the throne], and they [or “he,” i.e., the “ram”] took all the sealed books and opened those books before the Lord of the sheep” (Animal Apocalypse 90:20). Footnote 25 Compare the motif of the “sealed” revelation in Dan 9:24 (לחתם חזון ונביא) “to seal up vision and prophecy,” with its diverse interpretations) and 4Q300 1b (חתום מכם [נח]תם החזון “the vision is sealed from you”; compare also its “opening” there: ואם תפתחו החזון “and if you open the vision”). Footnote 26

These passages may be divided into three groups: 1) those referring to celestial books registering human deeds or lists of the righteous (like the books of judgment and the book of life in Rev 20:12, etc., well known already in the Hebrew Bible); 2) books that refer rather to the future and are being revealed to an apocalyptic seer, that is, books of revelation per se (also known already to Isaiah and Ezekiel; see the section “Gilayon as ‘Revealed Book’ ” above); 3) some books that are not only referring to the future but are also active agents initiating apocalyptic events (as in Revelation; cf. Zech 5:1–4; Odes Sol. 23). Footnote 27 In fact, then, these groups often overlap, and all relate to the imagery of closed or sealed celestial books being opened in order to refer to hidden knowledge. Their opening unfolds the divine will and initiates celestial judgment, sometimes through an eschatological train of events. The active character of these books connects them to the imagery of messianic figures (on this see “Revealed Book and Incarnated Word” below).

C. Uncovered Gilayon versus Secret or Hidden Books

Just as the image of opened books is found in a dichotomy with closed or sealed books, in similar fashion the very idea of revealed books naturally presupposes the concept of hidden or secret books (or tablets) which may become discovered in a natural way (as “the book of teaching/law” in 2 Kgs 22–23) or, more often, miraculously revealed. Thus, in the very term gilayon we have a linguistic representation of the observation that it is the disclosure of divine secrets which is “the true theme of later Jewish apocalyptic,” Footnote 28 rather than eschatology, etc. Footnote 29

Apocalyptic secret books, even when uncovered, may still preserve their esoteric character, since they are often revealed only to a chosen few, at a prescribed time, or only in part: for example, Dan 12:4 and 9; 1 En. 32:21–22; 107:3; 2 En. 35:2; Jub. 1:27; 32:21–22; 45:15; 4 Ezra 12:37–38; 14:6, 26 and 46; T. Mos. 1:16–18; 10:11–12; Ap. John 31 (NHL 116); Ap. Jas. 1.8–32 (NHL I. 2); CMC 43 (54.1). Footnote 30 In this connection, it is also worth mentioning the secret books of Essenes and other Jewish sectarians Footnote 31 and other attested forms of concealed divine knowledge. Footnote 32

In general, there is always a tension (immanent for most mystical traditions) between the axiomatically esoteric character of revealed knowledge and the very fact of its revelation. The nature of a secret is therefore dynamic, since “there is a God in heaven who reveals secrets” (Dan 2:28). Paul Tillich has also identified a concept of so-called “reveal/conceal dialectics”: “Only what essentially is concealed, and accessible by no mode of knowledge whatsoever, is imparted by revelation. But in thus being revealed it does not cease to remain concealed, since its secrecy pertains to its very essence, and when therefore it is revealed it is so precisely as that which is hidden.” Footnote 33 Explicitly paradoxical Gnostic expressions can be illustrative in this respect: τὸ μέγα καὶ κρύφιον τῶν ὅλων ἄγνωστον μυστήριον … κεκαλυμμένον καὶ ἀνακεκαλυμμένον “great, secret, entirely unknown mystery of the universe … veiled and unveiled”; κρυβομένην ὁμοῦ καὶ φανερουμένην “both hidden and revealed”; ἀλάλως λαλοῦν μυστήριον ἄρρητον “without uttering, it utters an ineffable mystery” (Hippolytus, Ref. 5.7.20 and 27; 5.8.2). This very equivocality, characteristic for revelatory language, may be rooted in the intrinsic ambivalence of revelation, which often finds expression in a parabolic mode. Footnote 34

This unity of concealment and revelation is often found in an antithetic form in the New Testament: “the revelation of the mystery [ἀποκάλυψιν μυστηρίου] hidden [σεσιγημένου] for long ages past, but now revealed [φανερωθέντος]” (Rom 16:25–26; see also Mark 4:22; cf. Luke 8:17; Col 1:26–27; 3:3–4; Eph 3:4, 9–10; etc.). Thus, terms like ἀπόκρυφος or ἀπόρρητος may refer to the same “hidden” or “secret” knowledge to which ἀποκάλυψις/גליון and its synonym φανερόν apply. Footnote 35 See, for example, “For there is nothing hid [κρυπτὸν], which shall not be revealed [φανερωθῇ]; neither was anything kept secret [ἀπόκρυφον], but that it should become revealed [φανερόν]” (Mark 4:22; cf. Luke 8:17; Col 2:3).

With regard to later ἀπόκρυφος and ἀπόρρητος applied specifically to a certain class of books, we find them in various meanings and sometimes attributed to Jewish usage. Thus, a reference to ἀπόκρυφα as a Jewish term is found in Origen. Footnote 36 This attested Jewish usage may indicate that these Greek terms possibly go back to Hebrew or Aramaic forms, similarly to ἀποκάλυψις/גליון. Footnote 37 In LXX and Aquila ἀπόκρυφος regularly renders forms derived from the root סתר. Footnote 38 Compare, for example, נסתרות in CD 3:14 (and 4Q267 F1:6, 9; 4Q268 F1:7) and מגילות סתרים “secret [or rather just “private”] scrolls” in y. Šeqal. 5.1.49a; b. Šabb. 6b; b. B. Meṣ. 92a. Greek ἀπόρρητος regularly refers to Hebrew סוד in Aquila. Footnote 39

The revelation of heavenly secrets through writing a book, even if in a more academic than visionary setting, is a theme found also in rabbinic literature:

When the [Aramaic] translation of the Prophets was composed by Jonathan ben Uzziel based on [a tradition going back to the last prophets] Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, the Land of Israel quaked over an area of four hundred parasangs by four hundred parasangs, and a Divine Voice said: “Who is the one who has revealed my mysteries [גילה סתריי] to the children of men?” Rose Jonathan ben Uzziel and said: “I am the one who revealed your mysteries to the children of men. It is revealed and known to you that … I did it for your honor in order that discord may not abound in Israel.” (b. Meg. 3a)

That these secrets could be of a specifically “apocalyptic” nature we see from the immediate continuation: “And he [Jonathan ben Uziel] also wanted to reveal a translation of the Writings [לגלות תרגום של כתובים], but a Divine Voice said to him: ‘It is enough for you!’ Why? Because it [i.e., the collection of Writings, namely Daniel] speaks about the messianic end [קץ משיח].”

D. Written Gilayon versus Oral “Vision”

The disclosure of secrets may go as far as the occurrence or even prescription of wide dissemination (sometimes even among Gentiles and the wicked), as in 1 En. 82:1–2; 104:11–13; 2 En. 33:9–10; 35:2–3; 48:5–8; 54:1 (“the books which I have given to you, do not hide them”); Rev 1:11. Footnote 40 Given this task of dissemination, the role of writing becomes central as the most efficient tool for the preservation and dissemination of knowledge (even if still relatively young and controversial at the time; see on this below). The development therefore entails an image of the revealed written text—that is to say, gilayon.

This new term might serve, inter alia, to distinguish later, and more logocentric, apocalyptic experiences or literary genres from biblical prophetic encounters entitled “visions” (חזון,חזיון,מחזה), Footnote 41 “oracles,” or “utterances” (משא). Footnote 42 Thus, Paul distinguishes between ὀπτασίαι (“visions”) and ἀποκαλύψεις (“revelations”) in 2 Cor 12:1.

This emphasis on scribal rather than oral prophetic practices must reflect a change in intellectual practices and in the Zeitgeist in general. It finds parallels in many apocalyptic contexts, which refer to celestial scribal activity (1 En. 74:2; Jub. 4:17; 2 En. 22; 23:4–6; 4Q203 8; b. Ḥag. 15a) Footnote 43 as well as to the scribal activity of apocalyptic seers (1 En. 12:4; 15:1; 82:1: 92:1; 4 Ezra 12:36–38; T. Mos. 1:16; Rev 1:11; etc.). Footnote 44 More generally, we can observe a dichotomy of biblical prophets replaced by apocalyptic sages or scribes, such as Enoch, Baruch, and Ezra or the visionary sages of later Hekhalot literature. Footnote 45

Thus, the semantic ambiguity of the word gilayon, which contains the meanings of both “book” and “revelation,” may reflect a certain development of apocalyptic concepts and practices in comparison to the earlier prophetic tradition. In particular, this implies: 1) less figurative conceptions of revelation, including the revealing of written materials—that is, revelatory reading rather than seeing; and 2) a functional form of the genre, written rather than oral.

It is noteworthy that chronologically this process closely precedes the fixation of the “Oral Teaching,” the Mishnah, which was “sealed” at the end of the second century CE. Might these two phenomena belong to the same conceptual development—a gradual change of approach toward the written fixation of esoteric/oral knowledge, together with a concomitant change in its function and status? The ancient controversy surrounding written fixation applied to various genres and is attested widely, from Plato, who refers to the written word as “not the truth but a semblance of wisdom” (σοφίας … δόξαν, οὐκ ἀλήθειαν; Phaedr. 275a) and Qohelet, with his skepticism regarding “making many books” (Eccl 12:12), to the Talmud’s harsh warning: “Those who record halakhot are like him who burns the Torah. And whoever studies these [written collections] has no reward” (כותבי הלכות כשורף התורה והלומד מהן אינו נוטל שכר; b. Giṭ. 60b and par.). Footnote 46

Orality and esoteric secrecy are connected in the rabbinic discussion of putting the oral teaching in writing: “God said to the nations of the world: ‘You say that you are My children. I do not recognize as My children any but those who have My secrets [אלא שמסטורין שלי אצלו]’ And which are these? The Mishnah, which was given orally [שניתנה על פה] and from which everything can be learned” (ascribed to R. Yehudah bar Shalom, Palestinian amora of the end of the third century CE; Tanḥ, Ki Tisa 34 [Buber 59a, n. 120]; Pesiq. Rab. 5, 14b and par.). Footnote 47 Also Paul, when arguing against putting the new message in writing, presents a dichotomy between written things and those revealed directly to the heart, as in Jeremiah’s new covenant passage (31:31–34): “Do we need, like some people, letters of recommendation to you or from you? You yourselves are our letter, written on our hearts, known and read by everyone. You show that you are a letter from Christ, the result of our ministry, written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts” (2 Cor 3:1–3). A similar dichotomy may be found in Clement’s opposition of Christ as the “living Law” (nomos empsychos) to the written Law (Strom. 2.18.3–19.3; on this, see more in the section “Revealed Book and Incarnated Word”). Footnote 48

Opposition of different degrees and on diverse bases to the written word was in a fact a wider phenomenon and something not unheard of in Hellenic and Christian circles as well. Some of the arguments of these groups were also connected to considerations of esotericity. Footnote 49 On the other hand, writing practices could be justified as divine invention, not merely a tool for registering revelatory knowledge but an integral part of it. Footnote 50

With these polemics in mind, the fuller context of the concept of gilayon becomes clearer. Revelation given physically in the written form of gilayon (as opposed to a mere record of oral or visual experience) gained, in addition to enhanced authenticity, the further advantage of legitimacy in accordance with the principle that “what has been said orally you may not say in writing, and vice versa” (דברים שעל פה אי אתה רשאי לאומרן בכתב ושבכתב אי אתה רשאי לאומרן על פה; b. Tem. 14b; ascribed to the third-century Palestinian amora, R. Judah ben Nahmani). Given as a written document, gilayon could legitimately function as such.

E. Revealed Book and Apocalyptic Mediality

Thus, we are dealing here with one more corroboration of McLuhan’s thesis that “the medium is the message.” That is, media are not just means for communication but rather contain within themselves the conditions of a certain perception of reality. In the early stages of book culture, when the book had only recently been promoted to one of the most efficient and authoritative media, the books could not but become essential for communication between God and humankind as well.

In the previous section we observed some obvious connections between, on the one hand, archaic orality and visuality (although verbalized through ekphrasis) and between innovative writing and verbality (although quite iconic in its language), on the other. As verbality is communicatively more efficient than visual language, so too the written text proved to be more efficient in several respects than oral communication. Inter alia, the written text, being an “autonomous discourse” detached from the one who transmits it, cannot be as easily contested as oral speech. Footnote 51 We may compare this ancient shift in media to the contemporary comeback of the visual and a concomitant new “iconic turn,” Footnote 52 and especially to the intrusion of the digital into all spheres of life, including religion. Footnote 53 Even as modern technological media undergo processes of gradual acceptance into religious discourse, mythologization, and “spiritualization,” Footnote 54 so too the “logocentric turn” of antiquity, together with the relatively new medium of the book associated with it, may have engendered similar phenomena. Footnote 55

Our discussion of the medial aspects of the introduction of gilayon would not be complete without raising another question: What other media could compete at the time with the book for expression of God’s communication with humankind? Among written media, the book had clearly begun to replace other, more archaic forms, such as tablets of stone or other materials. We can most demonstratively observe this shift in connection with the Book of Jubilees, which still refers to the precedence of tablets but simultaneously builds up its own authority as “Scripture.” Footnote 56 But did the book have competitors among non-written media? For us who live toward the end of book culture, the shift in imagery caused by an ancient medial revolution may be compared to the recent actualization of previously less ubiquitous “networks,” “webs,” or “screens.” Footnote 57 Although images of “web” and especially “net” were popular in prophetic and apocalyptic discourse, they were not yet tied to communication media. It was the screen, at that time an imaginary visual medium, which competed with the more realistic book as early as the early centuries CE. The “screen” (a frame showing moving images) was the main medium of revelatory experience in the Apocalypse of Abraham, which even introduced a special term for it—Church Slavic hapax legomenon образьство—derived from a root with the meaning “image, picture” (possibly from Gk μορφή, Hebמראה or תמונה, as in MT and LXX of Job 4:16). This screen was created by an opening in the spread of the heavens on which the visionary stood (Apoc. Ab. 19:4), thus enabling him to see everything beneath his feet through this aperture (22:1, 3, 5, 7; 23:1, 4; 24:1, 3; 26:7; 27:1, 7; 29:3, 11, 17). The seer even orients/describes a mise-en-scène of his vision in relation to the left and right borders of this moving “picture” (22:3–5; 27:1; 29:11). Functionally this is very similar to the image of another version of the screening medium, known as pargod, a celestial curtain spread before God that also shows moving images (3 En. 45:1–6; cf. 1 En. 91:2; 4Q180; and many hekhalot texts). The similarity between the “picture” presented through a hole in the heavens in the Apocalypse of Abraham and the celestial curtain of 3 Enoch intensifies once one considers that the lowest heaven was widely known as a “curtain” in the rabbinic tradition, including 3 Enoch (Heb. vilon, from Lat. velum; 3 En. 17:3; b. Ḥag. 12b; etc.).

In later Christian practices, not imaginary but real-life visual media of religious art not only facilitated visions but were even revealed by themselves, either as an image for copying, like the Man of Sorrows, a “true likeness” of Christ, seen by Gregory the Great in the sixth century, or even physically, as the Veil of Veronica in the thirteenth century or the Virgin of Guadalupe in the sixteenth. However, despite the importance both of visuality in revelatory experience and of visual media in religious practice, the latter has never become as important for the former as the book did: “And all the vision has been to you like the words of a sealed book” (Isa 29:11).

Gilayon and its Contexts

A. Revealed Book and Incarnated Word

We have seen that gilayon could be not only a “book about revelation” or a “book about a revealed book” but sometimes also a “revealed book” itself (for the latter see, especially, in 1 and 2 Enoch and Revelation quoted above). The motif of an otherworldly text being revealed, that is, materialized, has another important variant in addition to the motif of the revealed book. I mean the idea of the incarnated Word (“and the Word became flesh” καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο; John 1:14), whose function is, inter alia, a revelation of the Divine Glory (the verse continues: “… and we have seen His Glory” καὶ ἐθεασάμεθα τὴν δόξαν αὐτοῦ) and who is “the Word of God in its fullness, the mystery that has been kept hidden for ages and generations, but is now disclosed to the Lord’s people” (Col 1:25–26). Footnote 58

Moreover, we have an even closer variant—Christ himself might be depicted not only as the incarnated Word but even as an incarnated book. Jesus is described as an embodiment of “the living Book of the Living” Footnote 59 in the late-second-century Gospel of Truth 19.34–36, where he “puts on that [Father’s] book” and, being “nailed to a tree,” thus publishes “the edict of the Father on the cross” (20:24–27). Footnote 60 Baynes suggests that the “Christ-as-a-book” image may be rooted in a Christian reading of the enigmatic Ps 40:7(8): Footnote 61 MT: הנה־באתי במגלת־ספר כתוב עלי “Here, I have come, in the scroll of the book [or: “open/unsealed book”] it [or: “which”] is written upon [or: “about”] me”; LXX: Ἰδοὺ ἥκω ἐν κεφαλίδι βιβλίου γέγραπται περὶ ἐμοῦ “Behold, I am coming in the knob of a scroll [or “in a (little) scroll of a book” or “in the beginning of the scroll”] written upon [or: “about”] me.” The verse could be understood as speaking about a book written “upon” a person, and it was quoted as applied by Jesus to himself in Heb 10:7. Footnote 62

Wisdom, often identified with Christ (1 Cor 1:24, 30; etc.), Footnote 63 can also be represented as a book, specifically the eternal and preexistent Law-Torah: “Afterwards she [Wisdom, ἐπιστήμη] made herself seen [ὤφθη] on earth and sojourned [συνανεστράφη] among men. She is the book of the commandments [βίβλος τῶν προσταγμάτων] of God, the Law that endures forever” (Bar 3:37–4:1); “Wisdom [σοφία in 24:1] sings her own praises … All this is the book of the covenant [βίβλος διαθήκης] of the Most High God, the Law which Moses commanded us” (Sir 24:1 and 23). Footnote 64

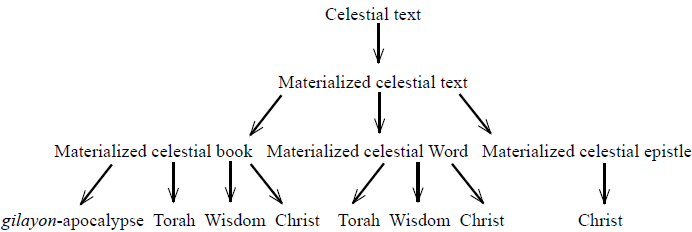

The table below presents semantic variants of the broader motif of the celestial text, in which the motifs of gilayon and Christ intersect:

This table shows, of course, only a simplified segment of a richer and more complex cluster of motifs. Thus, the materialized text may be represented not only by book and word, but also by tablets Footnote 65 and epistle. Footnote 66 The materialized divine Logos-Word has more representations in addition to Christ, and includes also Sophia-Episteme-Wisdom and divine Nomos-Torah-Law.

In fact, all these concepts could be identified with each other. Philo applied the term logos both to an intermediary divine being and to divine Law, which has corporeal representation as a book (see Philo’s use of the term logos for the Mosaic Law in Spec. 1.39.215 and elsewhere, and his explicit identification of them in Migr. 130 and QG 4.140). Thus, Torah could be not only an incarnation of a preexistent celestial book (on this, see section “Gilayon as ‘Revealed Book’ ”) but also, in a more philosophically developed model, of the celestial Logos-Word. This knot of meanings is further complicated both by identifications of Wisdom with Torah and of Christ with Wisdom (see above), Footnote 67 as well as especially by the notion of a new messianic Torah and of the messiah not only as its bearer or interpreter but also its embodiment. Footnote 68 Similarly, Clement synthesizes the gospels’ Logos-Christ with Philo’s Logos-Torah in order to apply Philo’s modification of a Hellenistic conception of “living Law” (nomos empsychos) to Christ (Strom. 2.18.3–19.4 et pass.). Footnote 69 It is noteworthy that, in contrast to most apocalyptic figures, Jesus does not accept any book from heaven to reveal to his followers (save in Ap. Jas. 1.8–32; see below). This may possibly be understood in the more general context of a shift of focus from the revealed book-Torah to the revealed messiah. As a kind of compensation for this development, the messiah himself could be perceived as the embodiment of a revealed celestial text, be it the Divine Word, celestial Torah-“Living Law,” or the celestial “Book of the Living.”

I have adduced here only clearly documented connections, but they can also be regarded as part of a more general context. All these associations are far from being accidental. They express conceptual, functional, and often etiological similarity among different variants of the more general motif of embodiment and/or personification of divine knowledge. Footnote 70 It seems that this variability may be explained, at least partially and reductively, by this motif’s somewhat spiral development from archaic forms of personification of divine knowledge (the Wisdom of the biblical myth) to its written representation in the age of letters (tablets, Torah, gilayon, and other revealed texts of the late prophets and the apocalyptic writings), as well as to a revived but philosophically charged myth of personification (the Logos-messiah of messianic apocalypticism). The result is a richness of imagery and concepts constituting a synchronic paradigm of synonymic, hyponymic, and overlapping elements.

We are interested here particularly in textual imagery and will therefore concentrate in this section on the relations between the revealed text and the divine Logos-messiah. We see here that gilayon, the revealed book of revelation, is found among other—often synonymic—representations of the divine Text, such as Logos, Wisdom, Torah and Christ. This contiguity of the motifs of the revealed celestial text and an incarnated celestial being enables us to perceive a certain association between the concepts of revelation and incarnation as one of its manifestations. Such a connection, in turn, reveals the additional link between apocalypticism and messianism (especially in its Christian form) as a special case of the type.

There are further and more specific similarities between the two conceptions. Thus, for example, the idea of preexistence with subsequent incarnation is common to the concepts of revelation and salvation, revealed book and messiah. Both messiah and gilayon-revealed book may be preexistent and concealed in heaven in order to be revealed. Similarly to the concealed and revealed books (see the section “Uncovered Gilayon versus Secret or Hidden Books” above), the Son of Man “was concealed in the presence of the Lord of the Spirits prior to the creation of the world, and for eternity” (Parables of Enoch 48:6) and then revealed: “For the Son of Man was concealed from the beginning, and the Most High One preserved him in the presence of his power; then he revealed him to the holy and the elect one” (Parables of Enoch 62:7); “the Anointed One will begin to be revealed” (2 Bar. 29:3); “For my son the Messiah will be revealed with those who are with him” (4 Ezra 7:28); “the reason I came baptizing with water was that he might be revealed [φανερωθῇ] to Israel” (John 1:31); “He was foreknown [προεγνωσμένου] before the foundation of the world but was revealed [φανερωθέντος] at the end of the times for your sake” (1 Pet 1:20); etc. Footnote 71

Nor does the similarity end here. If the celestial Son of Man is “revealed in flesh, justified in spirit, seen by angels, proclaimed among nations” (ἐφανερώθη ἐν σαρκί, ἐδικαιώθη ἐν πνεύματι, ὤφθη ἀγγέλοις, ἐκηρύχθη ἐν ἔθνεσιν; 1 Tim 3:16), the revealed celestial books are also handled by angels (Dan 7:10; 1 En. 103:2 [ms B]; 108:7; Jub. 1:29; T. Ab. A 12; Mart. Ascen. Isa. 9:20–21; possibly 1QM xii.1–3; Augustine, Confessions 13.151; etc.) and should be handed over to “all nations who are discerning, so that they may fear God, and so that they may accept them” (2 En. [J] 48:6). Another trait common to the revealed books and messianic figures may be their sometimes active (even violent) role in starting apocalyptic events (as in Rev 5–6ff.; cf. Zech 5:1–4; Odes Sol. 23).

B. ’Aven-gilayon as a Kind of Gilayon?

The Tosefta’s הגליונים וספרי המינין may be read not only as “apocalypses and books of heretics” (see section “Gilayon as ‘Revealed Book’ ” above) but inclusively (with וי”ו הפירוש) as “gilyonim and [other] books of heretics [often more specifically “Christians”].” Footnote 72 In this case gilyonim would mean rather “gospels” than “apocalypses.” Footnote 73 I will try to show that, in fact, these two interpretations are not necessarily contradictory.

Both terms, known to us mainly from Paul’s usage, had very vague boundaries. Not only the puzzling ἀποκάλυψις but even the better attested εὐαγγέλιον is known in a variety of meanings, even inside the New Testament, ranging from oral preaching or its content, the act of proclamation, or a kind of revelation to a specific written book, corpus, or genre definition. The association of gilayon with gospels appears also in b. Šabb. 116a–b in the derogatory puns ’aven-gilayon (Heb. און גליון “wicked book”; ascribed to the Tannaic scholar R. Meir) and ‘avon-gilayon (עון גליון “sinful book”; ascribed to the early amora R. Yohanan) for εὐαγγέλιον. That is, gospels might be defined here as a specific kind of gilayon. In addition, Ishodad of Merv’s commentary to Luke 1:1, which Pines cites as an example of the use of the term gelyānā’/gelyōnā’ (ܓܠܝܢܐ/ܓܠܝܘܢܐ), meaning “gospel,” may mean rather “revelation” in a more general sense, that is to say, including both apocalypses and gospels under the same genre definition. Footnote 74

The proximity of the meanings “apocalypse” and “gospel” may find expression not only in their unification under the same Semitic term (gilayon or gelyana’) but also in the use of their Greek counterparts (ἀποκάλυψις and εὐαγγέλιον) in combination with each other. This combination is found in both rabbinic and Christian texts. Thus, we saw that the Tosefta’s phrase הגליונים וספרי המינין can be understood also as “apocalypses and Christian books.” This reading has close parallels in the conjunction of “revelation” and “gospel” in the Pauline epistles: “I went in response to a revelation and, meeting privately with those esteemed as leaders, I presented to them the gospel that I preach among the Gentiles” (Gal 2:2); “I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that the gospel I preached is not of human origin. I did not receive it from any man, nor was I taught it; rather, I received it by revelation from Jesus Christ” (Gal 1:11–12); “Now to him who is able to establish you in accordance with my gospel, the message I proclaim about Jesus Christ, in keeping with the revelation of the mystery hidden for long ages past” (Rom 16:25). Compare also, “It has now been revealed through the appearing of our Savior, Christ Jesus, who has destroyed death and has brought life and immortality to light through the gospel” (2 Tim 1:10). Footnote 75

In general, in the New Testament evangelion regularly refers to Jesus’s disclosure as a revelation of the messianic secret. The term has obvious revelatory aspects in Rev 14:6–7; more importantly, the “gospel” there is held by an angel (ἔχοντα εὐαγγέλιον), similarly to the revealed “book” in 5:1–5, 8–9 and 10:2–10 of the same work. “Gospel” interchanges with “book” in Mark 1:1/Matt 1:1, where it appears as a book title (similarly to gilayon/gelyana’ and ἀποκάλυψις, which also often serve as book titles).

Thus, the semantic relations between gilayon-ἀποκάλυψις and εὐαγγέλιον in different instances could be at least hyponymic (the latter as a kind of the former) or intersecting (both might have the meanings of “revelation” and “revealed book”).

The data above may witness an authentic understanding that early Christian documents belonged to the apocalyptic corpus as defined more broadly. Gospels (or the texts standing behind them) could be understood by the ancients as a kind of apocalyptic writing. Footnote 76 Gilayon might thus be applied to a wider spectrum of genres and be rendered not only by ἀποκάλυψις but also by εὐαγγέλιον and possibly even λόγιον (which is a perfect metathesis of gilayon). Greek λόγιον, often used for God’s oracles and the Scripture in general, was central for early Christian usage as a specialized term for Christ’s sayings (and sometimes also deeds), often in fact synonymous to εὐαγγέλιον. However, in distinction from other paronomasic associations we discuss below (see especially in the section “Paronomasia of gl and the Role of Wordplay in Hebrew Religious Rhetoric”), this one has no syntagmatic representation and is thus just a guess based only on phonetic and functional similarity.

Traces of the chronological development of this association between gilayon and εὐαγγέλιον in the context of the Jewish-Christian “parting of the ways” might be traced in the rabbinic tradition. As we have seen above, there might be a progression from a genre definition common for apocalypses and gospels and the neutral rendering of gilayon in the Tosefta to a later polemic distancing as documented by the Babylonian Talmud.

Thus, we can now raise the question: could Heb גליון or Aram * גליינא(and not בשורה) be behind Jesus’s invitation to “believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:15)? Footnote 77 Could it have originally sounded like “believe in the gilayon,” with all the rich complex of meanings this would have entailed, including “salvific revelation,” “incarnate celestial text,” and even a personal application to Jesus himself, understood as the preexistent Word or an incarnated celestial book (as discussed in the previous section)? Footnote 78

The more general association of gilayon with “salvation” will be treated in the next section.

C. Gilayon and Ge’ulah

We find not only essential and functional similarities between messianic figures and celestial books, but also their association in the same scenarios. Thus, messianic figures receive their authority through approaching celestial books (as in Daniel) or receiving them (as in Revelation): “The court was seated, and the books were opened … and there before me was one like a son of man, coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power” (Dan 7:10–14); “He [the Lamb] went and took the scroll from the right hand of him who sat on the throne. And when he had taken it, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb” (Rev 5:7–8). Footnote 79 Sometimes the messiah’s very disclosure of secrets takes a book form: “I send you a secret book which was revealed to me and Peter by the Lord … a secret book which the Savior had revealed to me” (Ap. Jas. 1.8–32 [NHL I. 2]).

More generally, the affinity between revelation of hidden knowledge and salvation (especially at the end of days) are two motifs closely connected not only by the conceptual similarity of their agents, but also syntagmatically. That is, they are often found in conjunction with each other. The messianic age of salvation is among the main themes of biblical prophecy. The centrality of this topic in the Apocalypse of John stands behind the vulgar usage of “apocalypse” in modern languages in the meaning that refers to the most striking details of the apocalyptic scenario.

It has already been noticed that there is “an intrinsic relation between the revelation which is expressed in an apocalypse as a whole and the eschatological salvation promised in that revelation.” Footnote 80 Among the most obvious reasons for this union of concepts is that salvation could be understood as an expression of God’s or of his messiah’s epiphany. The very term apocalypse could be applied not only to a “revelation” of God’s secret (ἀποκάλυψιν μυστηρίου; Rom 16:26) but also to an “unveiling” of God’s Glory (ἀποκαλύψει τῆς δόξης; 1 Pet 4:13) as the main content of such a divine secret.

In the early Jewish context the time and details of salvation were among the most desired “secrets” to be revealed, and thus salvific eschatology figured among the most common elements in the content of revelatory writings.

Conversely, it is in the eschatological setting, and sometimes through a messianic figure, that revealed knowledge of various kinds (not only concerning salvation) is given. The messiah is not only revealed but also reveals: “And he has revealed the wisdom of the Lord of the Spirits to the righteous” (Parables of Enoch 48:7). The secret books are hidden or sealed only until the proper eschatological time comes for them to be opened (1 En. 82; 4 Ezra 12:36–38; 14:24ff.); only then will knowledge be given (Astronomical Book 91:10 and Apocalypse of Weeks 93:10 [esp. in Aramaic version]; cf. 1 Cor 2:7, Eph 1:9–10; etc.). That is, when prophecy has ended (as in 1 Macc 4:46; 9:27; 14:41), revelation is expected to be renewed only at the end of days: “The Torah which a man learns in this world is as nothing compared with the Torah of the messiah” (Eccl. Rab. 11, 8). The messianic kingdom itself will be “revealed” (איתגליאת מלכותא; Targ. Jon. to Is 52:7; Ezek 7:7).

Salvation, be it cosmic, national, or personal, is often conditioned by a revelation of otherworldly, hidden, or esoteric knowledge. This linkage of the revelation of secrets with soteriology seems immanent for the early Jewish system of concepts; however, it is attested mainly with esoteric (and sometime possibly even secret) groups that cultivated an actualization of salvific eschatology along with esoteric practices. Footnote 81 Thus, the “mystery to be [revealed?]” (רז נהיה) seems to be connected to eschatology in the Book of Mysteries (1Q27; 4Q299–301) and 4QInstruction. Footnote 82 Disclosure of μυστήριον in the New Testament denotes salvific secrets. Footnote 83 The very concept of gnosis involves revealed esoteric knowledge being the only means of personal salvation for “the Knowing ones.” Footnote 84 Similarly, Shi‘ur Qomah promises the reward of afterlife to everyone who knows the mystical dimensions of the divinity. Footnote 85 One may compare also salvific interpretations of Greco-Roman mystery rites as granting salvation (σωτηρία) in the form of immortality and the dispensing of cosmic life. Footnote 86

To sum up: salvation is the ultimate revelation of God; salvation and revelation are produced through the same or related agents; salvation and the savior are revealed; revelation is given by the savior and/or through the salvific process; revelation is a condition of salvation. This multifaceted conjunction of revelation with salvation and salvific eschatology, inherent already to the earliest apocalyptic texts, finds its pronounced theoretical conceptualization only in later Jewish thought, when it becomes a commonplace of Zoharic and Lurianic kabbalah. Similarly to Philo, these modes customarily applied philosophic patterns to ancient mythological thought. Footnote 87

I would like to suggest that the connection between revelatory genre and soteriology (as its frequent content) could be rooted not only in myth and speculative thought but also in the spirit of the language itself (as often found in the Hebrew tradition; see “Paronomasia of gl and the Role of Wordplay in Hebrew Religious Rhetoric” below). It may be traced inter alia to the homeonymity of the roots g’l and gly (Aram gl’), whose similarity may be based on a metathesis of alef and yod. Puns based on metathesis are quite common in the Bible: see חדל and חלד in Ps 39:5–6(4–5); פאר and אפר in Isa 61:3; compare also metathetic plays with the roots bkr and brk in Gen 27:19 and 36 or ‘qb/’bq/ybq in Gen 32:23–25(22–24).

According to a similar pattern, a wordplay with the roots g’l and gly, expressing affinity between the actions of (self-)revealing and salvation, is widely found in midrashic texts and also in many early piyyutim (I adduce only some): אתה גואל את בניך ומגלה מלכותך בעולם “You redeem your sons and reveal your kingdom in the world” (3 En. 44:7); ר’ ברכיה בשם ר’ לוי אומר כגואל הראשון כך גואל האחרון (נגלה להם וחוזר ונכסה) מה ראשון נגלה להם וחוזר ונכסה מהם כך גואל האחרון נגלה להם וחוזר ונכסה מהם “R. Berechiah says in the name of R. Levi: like the first savior [גואל], so the last savior [גואל]. As the first one was revealed [נגלה] to them and then hidden from them again, so also the last savior [גואל] was revealed [נגלה] to them and then hidden from them again” (Pesiq. Rab. Kah. 5; Song Rab. 2, 3; Pesiq. Rab. 15, 1; Ruth Rab. 5, 10; Num. Rab. 11, 2); שנו רבותינו בשעה שמלך המשיח נגלה בא ועומד על הגג של בית המקדש (והיה) [והוא] משמיע להם לישראל ואומר להם ענוים הגיע זמן גאולתכם “Our teachers have taught: when the King Messiah is revealed [נגלה] he stands on the roof of the Temple and declares to Israel: ‘The humble ones! The time of your salvation [גאולתכם] has arrived!’ ” (Pesiq. Rab. 36, 1); שנגלה הקב’ה במקום ע’ז ובמקום טומאה ובמקום הטנופת כדי לגאול אותן “ … that God has revealed himself in the place of idol worshipping, impurity and filth in order to redeem them (Exod. Rab. 15, 5); כך ישראל נגלה עליהם הקב’ה לגאלם “Thus Israel, God has revealed himself to them in order to redeem them” (Exod. Rab. 15, 52 [19, 7]); א’ר שמעון בן יוחאי … ולמה גלה אותו למשה. על שהלך לגאול את ישראל “R. Shimon bar Yochai has said: … Why did he [God] reveal it [his name] to Moses? Because he was going to redeem Israel” (Tanḥ., Vaera 1); אמת במצרים נגליתה/כל בכוריהם בדבר הרגת/ובכורך גאלת “You have revealed yourself in Egypt, killed all their firstborn by your word, and redeemed your firstborn (Birkot keriat shma be-shaharit, Emet ve-Yatsiv; New York, Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), ENA, 2174, 22–24, l. 31–33 [second century CE]); Footnote 88 ?צ?מח יגלה לשבטי יע׳/ויזמרו גאולי אלהי יעקב/לגואל במהרה זרע יע׳ “A sprout will be revealed to the tribes of Jacob. And those redeemed by the God of Jacob will sing to the one who will speedily redeem the seed of Jacob” (Ma’ariv, Vetomar; Oxford, Bodleian Library, e.39 (2712), 102, ll. 21–23 [6th cent.]); ותגאול זרע תמימים/ותגלה משמי מרומים “And you will redeem the seed of the innocent ones and will reveal yourself from heaven on high” (Yannai, Kedushtot le-shabbatot ha-pur‘anut ve-ha-nehama; Cambridge, University Library, T-S Collection, H 13, 4, 16, 188, ll. 1–2 [sixth century]); ובא לציון גואל/ויגלה תשבי במעמוד הדריאל “And the redeemer will come to Zion and will reveal [Elijah] the Tishbite in [?] Hadriel” (Eleazar Kalir, Shiv‘atot le-arba parshiyot; Oxford, Bodleian Library, e.34 (2716), 6–7, ll. 68–69 [before 640]); וכסא מלוכה ייגל אריאל/(ותג?ו?לי) ותג[י]לי בבוא לציון [אל]/גואל ישראל “Ariel will reveal the Throne of the Kingdom. And you will be redeemed [or: “will rejoice”] when [God?], the Redeemer of Israel, will come to Zion” (Eleazar Kalir, Krovot ve-hashlamot krova le-Tish‘a be-Av; Cambridge, University Library, T-S Collection, NS, 71, 46, ll. 68–70 [before 640]).

D. Paronomasia of gl and the Role of Wordplay in Hebrew Religious Rhetoric

A brief methodological digression is needed here, although some aspects may possibly be obvious already. Methodologically we have approached the problem of gilayon from three intersecting perspectives, which in conjunction may verify each other: 1) We began with semantic considerations, involving constructing a paradigm of similarities in content with the potential to be realized historically. Thus, for example, from a purely semantic viewpoint logos as incarnated Word and gilayon as incarnated book are co-hyponyms of incarnated text. But the question then arises: were they really connected in the minds of contemporaries? 2) To answer this question, it is important to introduce the syntagmatic aspect, verifying if the two were associated together in the same texts; that is, whether this affinity has any documented historical corroboration. 3) A less trivial perspective we want to test here is linguistic. Could the association of ideas have additional material basis in linguistic similarities?

In previous remarks we placed some weight on what we called a “spirit of the language,” which at times could be either a cause or an accomplice of both mythological imagination and speculative thought. The homonymy or polysemy of gilayon or a bilingual word-play between gilayon and evangelion is quite evident, and paronomasia of gilayon and ge’ula, which would connect the roots glh (gl’) and g’l (see above), seems at least plausible. However, further puns might have seemed too far-fetched, were it not for the abundant precedents of paronomasia in ancient Hebrew rhetoric that grew into a widespread propensity for puns in rabbinic discussions. It is well known how significant was “allusive paronomasia specifically for the purpose of constructing theological discourse.” Moreover, its “important role in the growth of the biblical text as a whole and in the development of ancient Israelite and early Jewish theological traditions” is well documented and may be relevant also for texts preserved or even composed in Greek in the multilingual setting of Hellenistic Judaism. Footnote 89

gll and glh 1: One such Hebrew pun uses the same roots—glh “open, reveal” and gll “roll, revolve, fold, unfold”—as are involved in the polysemy (of the originally homonymic) gilayon. It is explicitly pronounced by Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite in his etymology of Ezekiel’s term for the wheels of the divine Chariot: “For, as the theologian [i.e., Ezekiel] has pointed out, they [the winged wheels] are called gelgel [γελγὲλ in LXX 10:13; in MT galgal, גלגל, from the root gll], which in Hebrew signifies both ‘revolving’ and ‘revealing’ ” (Celestial Hierarchy 15.9; 337D). Footnote 90 Here it is noteworthy that we are dealing not only with the same roots but also with the same model of suggested polysemy of an apocalyptic term, which may take on the meaning “revelation” in addition to its main meaning (much as gilayon takes the meaning of “revelation” in addition to its basic meaning of “book-roll”).

This association of the wheel with revelation is especially interesting in the light identification of wheel with christological imagery: with the star of Bethlehem and the cross in a Sahidic fragment of an apocryphal gospel (British Museum Oriental 3581) Footnote 91 and with the celestial epistle (possibly identified with Jesus) in Syriac Odes Sol. 23:1–18. Footnote 92

The very possibility of such word plays invites more, and probably more convincing, arrays into vulgar etymology than the one ventured by Pseudo-Dionysus. The semantic complex of paronomasia of roots containing gl may in fact unite the concepts of revelation, salvation, exile, and book.

gll and glh 2: Another pun with the same roots is found in Amos 5:5: הגלגל גלה יגלה “Gilgal shall surely be exiled.” Footnote 93 Here gll is juxtaposed with the the same root, glh, but used with a different meaning, “exile, banish” (we call this meaning hereafter glh 2). The same wordplay may possibly be found in the Qumranic Book of Mysteries—וגלה הרשע מפני הצדק כגלות [ח]ושך מפני אור “and wickedness is banished before righteousness, as darkness is rolled away before light” (1Q27 1, col. 1 and 4Q300 3)—if the secondגלה is understood as גלל, as in גולל אור מפני חושך in b. Ber. 11b. Footnote 94

glh 1 and glh 2: Both meanings of glh, “revelation” and “exile,” exist and are played upon in the Palestinian Talmud in a saying ascribed to the most celebrated mystic of the Tannaic era: תני ר’ שמעון בן יוחי בכל מקום שגלו ישראל גלת השכינה עמהן גלו למצרים וגלת השכינה עמהן מה טעמא הנגלה נגליתי אל בית אביך בהיותם במצרים לבית פרעה “R. Shimon ben Yochai taught that anywhere the people of Israel were exiled, the Divine Presence was exiled with them. When they were exiled to Egypt, the Divine Presence was exiled with them. Because it is said: “I surely revealed [also: “exiled”] Myself to your father’s house when they were in Egypt [subject] to Pharaoh’s house” [1 Sam 2:27] (y. Ta‘an. 3.1a). Later Jewish mystical teachings have also developed this conjecture: כמו זה שאמר רבי יוחנן, כל הגליות שגלו ישראל מארצם, כלם היה גלוי לכל, והגלות הרביעית לא נגלה לעולם “As said by R. Yohanan: All exiles in which Israel were exiled were revealed to all, but the fourth exile was never revealed” (Zohar Hadash, Gen. 346). Beyond the wordplay, the motif of revelation of hidden knowledge through exile may be seen in the exile from heaven of the Watchers (as agents of communication of celestial knowledge) in Book of Watchers 8, Footnote 95 as well as in Christ’s exile to earth as possibly implied in Phil 2:6–8.

glh 2 and g’l : This second meaning of glh “exile” is also found in a no less meaningful connection with “salvation.” The motif of “exile and redemption,” golah/galut and ge’ulah, is an apocalyptic variant of the viable Jewish “exile and return” trope based on the model of redemption from the Egyptian and Babylonian exiles. Footnote 96 We can say that the two concepts of exile and redemption construct a dialectic unity (similar to the “reveal/conceal dialectics” discussed in the section “Uncovered Gilayon versus Secret or Hidden Books”). This finds its spiritualized expression in the concept of the Divine Presence’s concealment or exile and expected restoration. Footnote 97 In certain forms these words are almost identical (see, e.g., golah and ge’ulah or galutkem and ge’ulatkem below), but the attested play on the proximity of the two roots is found not earlier than in the sixth-century piyyut, for example, in ויחיש גאולה לגולה/ליושב תהילה “ … to the One who sits in glory/and He will hasten redemption to the exile” (Krovat Shmona-Esreh le-hol ha-Moed Sukkot; Cambridge, University Library, T-S Collection, H 16, 5, l. 10–11 [sixth century]); גאולה בגולה מצא/ בעת תם יצא “when the innocent went out/he found salvation in exile” (Shimon bar Megas, Kravot le-Shabbtot ha-Shanah, Genesis; Oxford, Bodleian Library, c. 20 (2736), 5–6, l. 2–3); etc. Footnote 98 Compare the thirteenth-century Zohar: דרשו מעל ספר ה׳ וקראו, ושם תמצאו במה תלויה גלותכם וגאלתכם “Seek from the book of the Lord and read it, and you will find there on what depends your exile and your salvation” (Zohar, Exod. 129b).

Conclusions and New Questions

The reconstruction of gilayon as both “revealed book” and “book of revelation” pertains to a central image and genre definition of an important corpus of early Jewish literature. Although based on admittedly scant direct evidence, it has explanatory power for many phenomena of early Jewish mysticism. The semantic ambivalence of the term gilayon, which is absent in its Greek counterpart apocalypse (ἀποκάλυψις), exposes meanings and associations that shed additional light on apocalyptic texts. It enables us: 1) to properly evaluate the centrality of the concept of the revealed book in apocalyptic narratives; 2) to understand how this concept is related to the oppositions of open and sealed, discovered and hidden otherworldly books; 3) to connect apocalyptic imagery to the “logocentric turn,” that is, the growing actuality of written culture for religious experience and the shift in media in late antiquity; 4) to reevaluate relations between different kinds of otherworldly, preexisting, and incarnated texts in early Jewish thought and to refine the paradigm of motifs dealing with embodiment of divine knowledge; 5) to question boundaries between apocalypse and gospel as genres and to discern an authentic understanding that early Christian documents belonged to the widely understood “apocalyptic” corpus; 6) to suggest additional connections between the revelatory genre and soteriology based on the similarity of the motifs of revealed book and incarnated Word, on the motif of Christ as book, on the association of apocalypse and gospel, and also on the metathetic paronomasia of g’l and gl’ which connects the concepts of gilayon and ge’ulah, the disclosure and dissemination of secrets with salvific eschatology; and 7) finally, to perceive the latter phenomena within the broader context of the widely attested paronomasia of gl in Hebrew religious rhetoric, which connects not only gilayon and ge’ulah but also gl’ and gilgal, gilgal and golah, gilayon and golah, golah and ge’ulah, thus forming a phonosemantic complex uniting the concepts of revelation, exile and salvation. Footnote 99

These preliminary conclusions cannot help but raise new questions, pertaining not only to reconstruction of ancient genre perception (emic perspective) but possibly also to the modern set of categories (etic perspective).

A. Emic Perspective

If we accept the reconstruction of gilayon, we should ask to what extent this concept could be integrated into the early Jewish corpus and what could be its scope: 1) Was gilayon synonymous with “revealed literature,” of which “apocalyptic” was only a subset? 2) Or, vice versa, did it narrow down the wider corpus of early Jewish revealed literature and refer to a specific variety of “apocalyptic literature” characterized by gilayonic imagery and/or semantic implications of the term gilayon? 3) Or, rather, did “gilayonic literature” overlap with what we now recognize as the “genre apocalypse” (especially if we include the genres of evangelion and/or logion under the category of gilayon)? Footnote 100

The extant data is more sufficient for raising these questions than answering them, but I will try to play with all three possibilities below.

To this end, we should check the entire apocalyptic corpus for three aspects of the concept’s functionality: 1) gilayonic imagery (revealed books); 2) use of the term (as reflected in its assumed Greek and Syriac calques); and 3) authentic corpus/genre definition (the use of relevant Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek terms as book titles or corpus/genre labels).

A comparison of the three groups of texts containing one or more of these phenomena produces interesting results. 1) The image of a revealed book or tablets, known already to the prophets, is almost universal for Jewish apocalyptic writings since the early Enochic texts, central to the Book of Revelation and known also outside the apocalyptic corpus, found for instance in Jubilees, Testament of Moses, and rabbinic literature (see references in sections 1–4 above). 2) At the same time, the very term ἀποκάλυψις (the assumed Greek calque of gilayon)—not as a title and in the sense of “revelation of divine knowledge”—may be found, out of all the apocalyptic writings, only in the Testament of Abraham (6:8); it is used once in the gospels (Luke 2:32) and found in abundance only in Pauline and deutero-Pauline epistles. Footnote 101 3) As a title, the Greek term (and its equivalents in other languages) appears widely, but only in books dated not earlier than the late first century CE: The Apocalypse of Abraham; Testament of Abraham (called Apocalypse of Abraham in rec. B, ms E); Apocalypse of Ezra; Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch (2 Baruch); Greek-Slavonic Apocalypse of Baruch; Apocalypse of Moses, atypical for the genre; the canonic Apocalypse of Jesus Christ (Revelation); Gnostic writings, such as the Nag Hammadi Apocalypse of Paul; (First) Apocalypse of James; (Second) Apocalypse of James; Apocalypse of Adam; Apocalypse of Peter; Footnote 102 and many later Christian apocalypses. The Syriac equivalent is used in the titles of 2 Baruch, Revelation, the Syriac Apocalypse of Daniel, and several pseudepigraphic books used by the Audian Gnostics. Its Hebrew equivalent as applied to some corpus of books appears in the Tosefta and refers to gospels in the Babylonian Talmud.

Groups 1 and 3 above largely overlap: early Jewish apocalypses titled as such often also have revealed book imagery (see especially 2 Baruch; 4 Ezra; Testament/Apocalypse of Abraham and Revelation). Group 2 is represented mostly by Paul, so all three groups overlap only in the Testament of Abraham. This is not very helpful for our purposes, since that text is not even a “classic” apocalypse: it bears the title “Testament” in most versions, and its images of celestial books registering human deeds have no connection to the usage of the term at 6:8. Thus, the term is not found in classic “apocalypses” at all.

Even as little as we can expect a balanced picture to emerge out of partially preserved evidence, the situation as described above may seem unbalanced. However, if we take into account that a polysemic Semitic term had in different contexts to be translated by different Greek words, we will see that it could not have been otherwise. Translators could not but render the term gilayon with terms for “book” in some cases and with terms for “revelation” (and possibly “gospel”) in other instances.

If we were to attempt a highly speculative reconstruction of the destiny of gilayon in translation, it might appear as follows: 1) The Hebrew gilayon (and/or Aramaic gelyana’) was used to designate revealed books in the Semitic Vorlagen of apocalyptic writings and was rendered in Greek as βίβλος, βιβλίον, βιβλαρίδιον, etc. Or alternatively, a less bold suggestion: if the word gilayon was not behind these terms, perhaps it was only the image of revealed books that inspired the wordplay of gilayon used in the titles of apocalyptic writings (since these were books about revealed books that often claimed to be revealed as well). 2) The Judeo-Greek term ἀποκάλυψις was reinvented as a calque of gilayon, and the bilingual Paul (or his sources) adopted it. If so, can we discern in these later works any traces of the term’s Semitic ambivalence, including with regard to the meaning of “book”? For example, if ἀποκάλυψις τῶν υἱῶν τοῦ Θεοῦ in Rom 8:19 implies “Gilayon of the Sons of God,” might it refer to something like the “Book of Watchers”? Christoffersson has already suggested that the “Sons of God” here might refer to the Enochic bene ha-’elohim (Sons of God) rather than to the sonship of believers as in Rom 8:15 and 23.Footnote 103 This, in fact, could even be an intentional wordplay, placing believers in the role of the redemptive angels of 1 Enoch.Footnote 104 In this case, the reconstruction of gilayon would have helped us to discover a new meaning in Romans and the fourth reference to the Enochic corpus in the New Testament. 3) As a following step, we would want to ask: Is it possible to find any traces of an association between revelation-gilayon and gospel-evangelion in Pauline and other Greek usage (beyond their sometimes vague distinction in the New Testament as well as combined usage and possible rabbinic echoes of this association, as presented in section “’Aven-gilayon as a Kind of Gilayon?”)? 4) Furthermore, even if all book titles using ἀποκάλυψις are late Christian interpolations imitating the title of the Book of Revelation, the usage of the latter would still require an explanation. As Morton Smith wondered, “If its [the canonical Apocalypse’s] title did not come from Paul [since “little else in the work seems to be Pauline”], what was the source from which both it and Paul derived this somewhat unlikely term for such material?”Footnote 105 I hope that in this article we have made some progress toward answering this important question.

This entire discussion brings us to more general but unavoidable questions about ancient genre taxonomies and their possible connections to implicit language philosophies. How did ancient Jewish authors understand textual categories? We know that biblical authors already distinguished explicitly among “teaching,” “law,” “song,” “vision,” “oracle,” etc. It is reasonable to assume that this genre-consciousness, inherent to any developed written culture, would have only increased during the Hellenistic period. Thus, the assumed absence of a Hebrew or Jewish-Aramaic term for a group of popular texts with such distinct commonalities contrasts sharply, at the very least, with hypothetical but grounded expectations. Yet if they did recognize revelatory literature as a genre, was their taxonomic thinking binary (Aristotelian/Porphyrian) or rather based on a more complex conceptual system, perhaps less “orderly” from the point of view of modern perception? Such a system could have reflected either dynamic relations between texts and historically situated practices and social structures, Footnote 106 or else the mode of textual “participation in” rather than “belonging to” genres (to use Derrida’s language). Footnote 107 They might even represent prototype structures (in cognitivist jargon), where some elements of a single class are “more equal” than others. Footnote 108 Thus, for example, association of texts by similarity could be based not only on their content, literary form, function, structural devices, setting, medium, etc., but also on such factors as linguistic features, particularly specialized language. In our case genre connections based on common imagery (revealed book and associated matters) could be strengthened by the phonetic similarities within a set of key concepts connected to this imagery (book–discovery–revelation–salvation–gospel). Behind this association must lie a conception of language in which linguistic similarity is inseparable from essence (a mode of thinking compatible with metaphysical realism, as formulated in Plato’s Cratylus and quite common for premodern thought in general). Footnote 109

B. Etic Perspective

Although this study was declaratively emic, it may provide an alternative to our conventional thinking about early Jewish mystical literature and afford an opportunity to reconsider the categories we create, addressing, in particular, the following questions: the extent to which our etic taxonomy is or should be dependent on emic reconstruction, how the latter is influenced by the former, and why delineation between the two may be difficult or artificial.

Thus, for example, the etic category apocalypse as defined in Semeia 14 became so influential that it has effectively become naturalized as an inherent part of the textual landscape of early Judaism; that is, in many cases it has become implicitly emic. As a result, it became hard to look for alternative and less expected ways that ancient authors could understand and categorize their key texts and motifs.

In this respect, the term gilayon may prove useful in certain discourses instead of apocalypse—in much the same way as we sometimes resort to other original Semitic forms instead of their Greek and other equivalents, like memra instead of logos, the Tetragrammaton instead of Lord, messiah instead of Christ, etc.

As we know, every new or modified element changes the entire paradigm. We can see all the effects of the introduction of a new term only if we regard it as part of the system of early Jewish concepts. Thus, the Aramaic term memra Footnote 110 enables one to narrow down the semantic field of the Greek logos, which denotes not only “word” but also “reason,” etc. The original form of the Tetragrammaton exposes archaic verbal associations of the Divine Name; messiah (משיח) “the anointed one” makes evident its paronomasic association with “savior” (מושיע), etc. So too the concept of gilayon, with all its implications, alters and refines the paradigm of our understanding of early Jewish mysticism.