1 Introduction

The eve of our first day of interviews in Maputo, Mozambique, the rain began. It poured down throughout the night and into the morning. At breakfast, others around us mentioned the potential threat of an incoming cyclone. Given that we were in town to talk with government and civil society actors about disaster preparedness, it seemed only appropriate that we press on with our plans for the day. Our hotel was a short ferry ride from downtown, but the road to the port was flooded. Thanks to the availability of a 4×4, we made it to the ferry station and then to the mainland. On arrival, we saw that the streets of Maputo, too, were awash in rainwater and debris, the sewer drains clogged by uncollected trash. On its face, the city was woefully unprepared for the ongoing storm.

But these issues masked what we later learned was happening in the background: active mobilization of government officials and nongovernmental actors to track the storm, prepare for any necessary evacuations, and activate additional precautions along the shoreline. Inland areas were pre-stocked with survival gear, such as boats, to be ready in the event of extreme flooding. While these preparedness programs were difficult for us as outsiders to observe, we nonetheless came to understand the significant ways in which the government in Mozambique had shifted the dynamics of cyclone threats to fundamentally improve the safety of at-risk populations. While these efforts might not ease immediate, less threatening, difficulties in the face of extreme weather (e.g. local, short-term flooding), they targeted high-risk issues that posed the greatest threats. To our good fortune, this tropical storm was not a particularly bad one, and the waters began to dissipate within a few days. Nonetheless, the experience offered a brief glimpse into the complex realities and practical difficulties associated with managing natural hazards.

This anecdote is also indicative of natural hazard experiences in many other parts of the world. As I came to understand during the research described in greater detail in this volume, significant preparedness efforts for natural hazards – such as floods, drought, and tropical stormsFootnote 1 – have been taken on in countries around the world, including across the Global South. Governments, on their own and encouraged by global accords, have often implemented substantial programs that ensure both rapid response at the time of a hazard and work to minimize the risk that hazards evolve into natural disasters. In India, for example, a case I consider in detail throughout this text, government efforts to ramp up preparedness programs began to emerge in the early 2000s and a robust, multilevel system for threat identification, preparedness, and response now exists for multiple types of hazards. This is easiest to observe in cases where hazards in recent years have led to significantly fewer deaths than those resulting from previous similar events, as has been the case with recent cyclones in India.Footnote 2

At the same time, the quality and comprehensiveness of these efforts can vary quite dramatically both across and within countries. In Mozambique’s neighbor, Zimbabwe, we see relatively fewer efforts to prepare for frequent threats such as drought. Similarly, adjacent to India in Pakistan we observe relatively disorganized efforts to prepare for increasingly common flood risks. Even within India, at the state level, we note variations in the degree to which neighboring states such as Odisha and Andhra Pradesh are prepared for the threat of annual cyclones.

That disaster preparedness initiatives of any type appear in these regions is also a surprise from the perspective of existing research on political incentives and natural hazards.Footnote 3 A predominant assumption in current work is that investments in preparedness are fundamentally unlikely. This is because preparedness actions are expected to be more difficult to observe, and thus reward at the ballot box, than investments in response (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009). Analysts argue that citizens reward effective political responses to natural disasters and punish failures to respond (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Bechtel and Hainmueller Reference Bechtel and Hainmueller2011; Cole et al. Reference Cole, Healy and Werker2012). At the same time, voters can fail to reward disaster preparedness, and may even punish incumbents for investing in preparedness over other public benefits, because the benefits of these policies are perceived to be less obvious that those of response (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009). This is despite the generally greater efficiency of spending on preparedness versus response (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009). In addition, the potential for moral hazard related to natural hazards, given the propensity of higher level domestic or international actors to respond in times of disasters, is believed to further disincentivize governments to allocate scarce resources toward preparedness activities (Cohen and Werker Reference Cohen and Werker2008). In short, existing work posits that political elites should have few incentives to prepare for natural hazards. Thus, the existence of, and variation in, disaster preparedness initiatives, even in closely lying countries or states facing similar hazards, is an empirical puzzle.

The primary focus of this Element is to examine this puzzle and provide a novel argument to explain the character of disaster preparedness initiatives in countries of the Global South. Why do governments prepare for natural hazards? And what characteristics of states are associated with the best preparedness outcomes?

I argue that disaster preparedness can, and does, occur in the context of both motivated ruling elites and a capable state. Ruling elites can be mobilized to lead preparedness efforts. The quality and character of these efforts subsequently depend on the government’s capacity to coordinate the design and implementation of preparedness plans. In this way, elite motivation and state capacity are both necessary conditions that, when they occur together, are sufficient to produce comprehensive disaster preparedness. Thus, ruling elites must be willing and the state they oversee able.Footnote 4 My argument elaborates the conditions under which this occurs.

I contend, in contrast with existing work that argues politicians do not have incentives to prepare for disasters,Footnote 5 that there are plausible political situations in which ruling elites will perceive benefits to investing in preparedness. Specifically, elites are motivated when there is a risk that past exposure to hazards will lead to political instability in the face of a future hazard. Elite motivation thus rests on two sub-variables: past exposure to natural hazards and elite perceptions of opposition threat.Footnote 6 Where elites anticipate a threat to their rule in the face of a future hazard, due to substantial past exposure and significant opposition strength, they will be motivated to engage in disaster preparedness.

The ability of elites to act on this motivation depends on a second primary variable: the state’s own competence in coordinating the bureaucracy and/or civil society actors to realize preparedness goals. Where government actors have the capacity to oversee preparedness efforts and are given the power to do so, ruling elites will plausibly succeed in implementing the highest levels of effective disaster preparedness.

In the remainder of this Introduction, I lay out a conceptual framework for analyzing natural hazards and disaster preparedness in the context of low- to middle-income countries of the Global South. I consider the relevance of this problem in the context of past threats in the region and across the globe more generally. I then elaborate the details of my argument for when governments are most likely to make preparedness investments, contrasting this with existing arguments for why governments would not invest in preparedness for natural hazards and the limited hypothetical conditions under which they would do so. I conclude with a discussion of case selection and the qualitative, medium-N case methodology used in this study, before providing background on the country and subnational cases considered here.

1.1 Natural Hazards, Disasters, and Preparedness

Natural hazards are rare or, at the very least, unpredictable events that can threaten lives and infrastructure. The most commonly occurring natural hazards are earthquakes, floods, droughts, tropical storms, and tsunamis. These hazards are typically divided into rapid onset (e.g. earthquake or tropical storm) and slow onset (e.g. drought). A natural hazard becomes a disaster when an area affected by the hazard is unable to respond in a sufficient manner, resulting in economic and, possibly, human and animal losses.

The threat of natural hazards seems clear from news reports of hurricanes, drought, and floods around the world. But how substantial are these threats in reality? As I discuss in greater detail, measuring the magnitude of a natural hazard is difficult due to a lack of valid measurement instruments that can indicate the strength of a hazard apart from its effects. For current purposes, I use share of the population “affected” by a hazard as an indicator of magnitude, which can be held constant across different types of hazards. Using data from EM-DAT – the international disaster database – I show in Table 1 the share of the population in each continent affected by natural hazards over the period 2005–2014.Footnote 7 These data highlight that the threat of hazards exists across the globe, but is particularly significant in Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Table 1 Variation in populations affected by natural hazards, 2005–2014Footnote 8

| Continent | Annual Average Individuals Affected | Percent of Total Population Affected over Entire Period |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 16,355,161 | 15.7% |

| Asia | 147,395,737 | 35.0% |

| Europe | 722,566 | 1.0% |

| Oceania | 182,856 | 5.0% |

| Americas | 11,594,451 | 12.4% |

Evidence also suggests that the threat of hazards has increased in recent years, particularly with changing meteorological dynamics due to climate change. Predicting the character of such threats is becoming more difficult. A recent study, also drawing on EM-DAT data, found that the occurrence of natural disasters globally had increased ten times over the period from 1960 to 2019 (IEP 2020). These figures may also undercount the occurrence of natural hazards, as preparedness efforts over this same period have played at least some role in reducing the likelihood of a hazard converting to a natural disaster.

Given these threats, what can be done to protect communities and individuals from natural hazards? Government and private sector efforts to deal with natural hazards take many forms, but are typically categorized as response, preparedness, or risk reduction. Response efforts happen at the time or after a hazard occurs, to minimize the damages and attempt to prevent a hazard from becoming a disaster. Preparedness efforts are focused on ensuring that there are programs in place to minimize the risks in advance of an impending hazard (such as evacuations) and improve the ability to respond when the hazard occurs (such as building shelters and conducting mock drills). Risk reduction instead emphasizes changing ongoing practices to reduce the fundamental likelihood of disasters occurring, such as implementing drought resistant agricultural practices. I consider the range of possible government policies in greater detail in Section 2.

Public debates and discussions about the appropriate policy response to natural hazards have shifted over the last few decades from a focus on response to preparedness to risk reduction. In the period leading up to this study, while risk reduction was seen as the ultimate goal, policy recommendations focused largely on preparation, reflecting perceived limitations on preparedness in most countries, especially in the Global South. In this volume, I primarily consider efforts to promote preparedness for natural hazards.

1.2 A Political Institutional Theory of Preparedness

The key theoretical question of this study is: what conditions will make governments most likely to implement comprehensive disaster preparedness policies? I argue that the most thorough efforts to prepare for natural hazards occur in those places where ruling elites are politically motivated to reduce the risks of future hazards and they also have the capacity to design and implement reforms. This is because effective policy initiatives – ones that are both initiated and implemented – require both political support and a capable set of institutions to implement the policy. But when is this the case?

I posit that disaster preparedness depends on two primary variables: elite motivation and capacity. Elite motivation rests on two sub-variables: past exposure and opposition threat. Past exposure implies a record of natural hazards that have affected a substantial portion of the population in the past. Opposition threat can come in the form of electoral competition, in established democracies, or the presence of plausible opposition parties, in the context of autocracies. Where ruling elites associate the potential for future hazards with the possibility of threats to their continued control, they will be motivated to engage in preparedness to reduce this threat.

Capacity depends on the government, and most significantly the bureaucracy, having the ability to develop and coordinate plans for disaster preparedness. The implementation of disaster preparedness initiatives may involve government actors and/or civil society, but how these programs are governed depends on the relative strength of different actors. The most successful outcomes will be observed where the state effectively leads the coordination of these efforts. Figure 1 summarizes this logic and I now examine each of these variables in greater detail.

Figure 1 A political institutional theory of preparedness

1.2.1 Elite Motivation

I begin from the expectation that countries which have faced greater hazards in the past will prepare more in the future. This idea is not new (Fox and Weelden Reference Fox and Van Weelden2015), but I offer a more nuanced and comprehensive explanation for why this is the case. Existing work highlights an empirical correlation between past hazards and preparation but does not sufficiently identify the causal mechanism linking exposure to greater preparedness (Keefer et al. Reference Keefer, Neumayer and Plumper2011; Hsiang and Narita Reference Hsiang and Narita2012). Do incumbent governments view natural hazards as a threat to their economic performance (World Bank 2009; Hsiang and Jina Reference Hsiang and Jina2014)? Do they perceive natural hazards as a potential cause of conflict (Hsiang et al. Reference Hsiang, Burke and Miguel2013)?

I suggest instead that ruling elites anticipate a potential threat to their incumbency when citizens can observe the preparedness counterfactual. If an individual has not faced a hazard in the past, as in places that experience these events rarely, they will have little ability to separate the quality of preparedness efforts from the intensity of the hazard itself. In other words, because the effects of a hazard are endogenous to preparedness efforts, someone without past experience of a similar event will be unable to gauge the value of existing investments to their or the broader welfare. These individuals cannot conceive of the preparedness counterfactual at the time of a natural shock: “what would have been the impact of a disaster in the absence of preparedness spending?” (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009: 389).

In contrast, those individuals who have previously been affected by a natural hazard are able to evaluate the quality of preparedness efforts at the time of a future hazard – the counterfactual to what would have happened without preparedness – and can use this information to evaluate the quality of incumbent politician performance. This expectation contrasts with the idea that individuals cannot observe and evaluate preparedness programs, relative to disaster response (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Gailmard and Patty Reference Gailmard and Patty2019): where individuals have previously experienced a failure to prepare, I posit that they will be able to evaluate the quality of preparedness efforts at the time of a future hazard.

Even if we assume that individuals have no ability to observe the actual policy changes that have occurred, in the form of disaster preparedness, otherwise similar individuals may still differ in the interpretation of their current welfare based on a comparison between the effects of past and current natural hazards. An individual who has been exposed to a natural disaster in the past, particularly one in which the government was ill-prepared, will have different expectations for the likely outcomes of a subsequent hazard. If the results of that hazard are better than in the past, then they are likely to have a higher estimate of their current welfare than someone who had not been exposed to a disaster in the past and so has much different expectations about the effect that a hazard would have on their wellbeing.

This supposition is in line with qualitative evidence regarding the behavior of individuals who were and were not exposed to a significant previous hazard at the time of a new hazard. In India’s Odisha state, which has a history of tropical storms, a severe cyclone in 2013 affected areas that had and had not been exposed to a similarly intense cyclone in 1999. Officials involved in evacuation efforts at the time noted that those individuals living in areas that had previously been affected were easily evacuated multiple days in advance, while those who had not been hit by earlier cyclones were considerably more reluctant to evacuate and, in the end, some forced evacuations were necessary in these regions (Odisha State Government Official #2 2014). If behavior at the time of the cyclone is associated with differing past exposures to natural hazards, then we might believe that other kinds of behaviors, such as voting, may also exhibit these differences.

Politicians who are knowledgeable about past hazard exposure can then anticipate this future evaluation and incorporate it into their policymaking decision calculus (Bussell Reference Bussell2017). The opportunity to observe multiple shocks over time implies that once a natural hazard has occurred, politicians may assume that at least some proportion of voters will be able to estimate the preparedness counterfactual based on their experience with this shock. In this sense, past experience of disasters changes the information available to a segment of voters, making them more competent at evaluating the performance of the incumbent than their non-disaster-exposed peers. As a result, the perceived electoral value of preparedness may increase, making preparedness activities more compelling as an electoral strategy than was previously the case. Investment in disaster preparedness, then, becomes a strategic electoral move on the part of incumbent elites, to increase the chances of retaining power in the face of a future hazard.

The relevance of this calculation to preparedness policies, however, depends on whether ruling elites perceive a general threat to their incumbency. This is a relatively straightforward expectation that politicians in electorally competitive democratic regimes or authoritarian regimes with a viable opposition will be willing to implement new policies that they expect to be received well by the public. Even if ruling elites anticipate that citizens can evaluate their preparedness efforts, these evaluations will only matter in contexts where those citizens can pose some sort of political threat, through voting, support for an opposition party, riots, or otherwise.

Combining these two sub-variables of elite motivation results in four general expectations for the character of incentives regarding disaster preparedness, summarized in Table 2. We should observe the strongest political incentives for preparedness where both past exposure and opposition threat are high. Where past exposure is high, but opposition threat is low, we should still expect to see medium to high incentives, given the risk of instability and negative public response in the face of a future hazard. Where there is a clear opposition threat but low past exposure, politicians will have only low to medium incentives to prepare, as the costs of preparation will compete with other policy areas that may have more obvious benefits to voters. Finally, where both past exposure and opposition threat are low, we should see the weakest political incentives for reform.

Table 2 Empirical expectations for elite motivation to engage in disaster preparedness efforts

| Opposition Threat | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Past Hazard Exposure | Minimal | Low Incentives | Low-Medium Incentives |

| Substantial | Medium-High Incentives | High Incentives | |

The discussion to this point thus suggests that where ruling elites have an expectation that disaster preparedness efforts are likely to result in electoral support at the time of a future hazard, and where they face a competitive environment in which they would benefit from additional popular support, we should expect to see political interest in disaster preparedness initiatives. To be successful in these initiatives, however, also requires the capacity to coordinate relevant actors who are capable of designing and implementing such reforms. I now explore this aspect of the argument in greater detail.

1.2.2 Capacity

The second key variable in my argument is the capacity of the state to coordinate disaster preparedness efforts. Following existing research, I conceptualize “capacity,” applied to state or non-state actors, as the ability of an organization to achieve the goals they set for themselves (Centeno et al. Reference Centeno, Kohli and Yashar2017; O’Reilly and Murphy Reference O‘Reilly and Murphy2022: 1). For a government organization, this typically involves “the ability to raise revenue efficiently, the ability to enforce a monopoly on violence within its territory, and the provision of public goods in such a way that supports the functioning of markets, especially the legal capacity to attain the rule of law” (O’Reilly and Murphy Reference O‘Reilly and Murphy2022: 1). For non-state actors, this implies parallel abilities to raise and manage financial resources, run a functional organization, and deliver relevant goods to target clients. Such a conceptualization implicitly assumes consistent underlying institutional structures that support and enable this capacity. This is, then, an argument about institutional capacity to support preparedness initiatives.

Substantial work in the social sciences has highlighted the importance of bureaucratic capacity for the effective functioning of government institutions. In their agenda-setting work, Evans and Rauch evaluate the degree to which state institutions exhibit “Weberianness” as a measure of state capacity, considering the presence of competitive salaries, internal promotion and career stability, and meritocratic recruitment (Evans and Rauch Reference Evans and Rauch1999). This capacity, they argue, is then linked to the ability of states to achieve economic growth (Evans and Rauch Reference Evans and Rauch1999). More generally, the quality of institutions came to be seen as a key factor affecting outcomes of both economic and social welfare (Rothstein and Teorell Reference Rothstein and Teorell2008, see also Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Victoria Murillo2009).

Related work focuses on the frequent gaps in, or limitations of, government capacity and looks outside the state to identify alternative providers of public goods. In the case of Kenya, Brass (Reference Brass2012, Reference Brass2016) shows how nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) increasingly play both direct and indirect roles in government service provision, through their participation in governance and in the direct delivery of services. More generally, Cammett and MacLean argue that “In many parts of Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, states are unable to provide extensive social welfare services, but a diversity of non-state actors such as multinational corporations, ethnic and sectarian organizations, NGOs, community-based organizations, and families provide and facilitate access to much of the welfare that exists on the ground” (Cammett and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2011: 1–2). In addition, the role of non-state actors in service provision is seen only to be increasing (Cammett and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2011: 1–2). These arguments imply that we may observe cases of non-state actors filling in where the state is unable to implement programming directly.

At the same time, it is insufficient to assume that non-state actors have consistent capacity to provide these services across countries. Non-state actors differ dramatically in their size, resources, modes of work, and connections to international affiliates or sponsors.Footnote 9 Relatedly, the relationship between non-state providers and state actors themselves is likely to have an important effect on outcomes (Cammett and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2011), particularly in those countries with significant restrictions on civic freedoms. Thus, variation in the capacity of non-state actors is also likely to affect their ability to play a role in disaster preparedness.

My first expectation related to capacity, summarized in Table 3, is that the governance of disaster preparedness efforts, and specifically the character of roles for the state and civil society actors, will depend on the relative capacities of these groups. Where both the state and civil society are of high capacity, the state should lead disaster preparedness efforts while effectively drawing on civil society actors to support its mission, which I characterize as “State-Led.” In contrast, where only the state has high levels of capacity, disaster preparedness efforts are likely to rely predominantly on the bureaucracy in a “State-Dominant” model. Here, when the government draws on non-state actors, it is likely to be only for additional support during times of hazard response, rather than in planning and preparedness exercises. In those cases where civil society has more dominant capacity, a “Society-Reliant” model may arise, with government delegating as many preparedness activities as possible to non-state actors. Finally, in areas with low capacity in both the state and civil society, what disaster preparedness activities we observe are likely to be haphazard and uncoordinated, given the minimal ability of local actors to successfully implement reforms.

Table 3 Expected character of disaster preparedness governance given state and civil society capacity

| State Capacity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | ||

| Civil Society Capacity | Lower | “Uncoordinated” | “State-Dominant” |

| Higher | “Society-Reliant” | “State-Led” | |

Overall, I argue that we should see the quality of disaster preparedness initiatives increase in line with levels of state capacity, where the government is able to direct the activities of state and/or non-state actors in developing and implementing preparedness initiatives. Because the government itself is the primary focus for most disaster preparedness programming, I expect outcomes to be better where the state has high capacity versus cases where civil society has high capacity. High state capacity is also important to ensure that diverse actors engaged in preparedness efforts do not, at best, duplicate work and, at worst, engage in activities that conflict with each other.

1.2.3 Theoretical Implications

The two primary variables in my argument combine to produce a set of expectations about the overall character and quality of disaster preparedness that I expect in each country or subnational region, as summarized in Table 4. A key implication of the argument is that disaster preparedness efforts will be insubstantial where ruling elites do not have incentives to support them, even in the context of high state capacity. Given this, we should observe the strongest performance in those places where there are considerable political incentives to prepare and there is overall high capacity to do so. We should also observe considerable efforts to prepare in those places with high political incentives but where there is more limited capacity. In these contexts, I expect to see evidence of governments making creative efforts to engage in preparedness within the kinds of diverse governance structures outlined in Table 3. In contrast, where there is higher capacity but only limited political incentives, we may see efforts that look like preparedness, but these will be more “window dressing” than deep and substantial interventions. This is because the government has the resources available to put forward basic policies and/or structures of preparedness, but ruling elites do not have the incentives to implement these initiatives in a comprehensive way. Finally, where there are lower electoral incentives and lower capacity, we should see the weakest efforts to invest in preparedness. In these cases, we may observe individual and disconnected programs, but no widespread and thorough disaster preparedness effort.

Table 4 Overall theoretical predictions for quality of disaster preparedness given elite motivation and capacity

| Elite Motivation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | ||

| Capacity | Lower | “Minimal Performance” | “Substantial Effort” |

| Higher | “Window Dressing” | “Strong Performance” | |

1.3 Methodology and Case Selection

This study uses a medium-N, country case study approach, supplemented by subnational case comparisons, to evaluate the character of disaster preparedness initiatives. The focus of the study is the two continents with the highest levels of threats from natural hazards, as measured by the percentage of the population affected by hazards in recent years: Africa and Asia (see Table 1). The first stage of the study considered Africa, with cases chosen based on a pairing of neighboring countries across the sub-Saharan region. This enabled us to select cases sharing somewhat similar natural hazard profiles while also including the range of natural hazards faced by countries in Africa.Footnote 10 The African country cases are Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal, Togo, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. The second phase of the research extended analysis to the three largest countries of South Asia: Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan.Footnote 11

It is worth considering whether findings from these cases may be relevant in the broader study regions and globally. In both Africa and South Asia, the cases include substantial variation on the independent variables of concern to the argument. As a result, these findings are likely to generalize to other country cases in the region, apart from failed states. In addition, I expect the argument and findings to be relevant in other regions facing considerable threats from natural hazards, such as much of the Americas. Whether the argument would hold in low threat regions such as Europe remains an open question. As these regions experience more extreme weather hazards due to climate change, I anticipate that this could lead to substantially greater preparedness, given high levels of both electoral competition and institutional capacity in the region, but with potential constraints I consider more in Section 5.

In addition to the country-level comparisons, I draw on a subnational comparison of disaster performance in India’s states, as part of a detailed Indian case study. This analysis focuses primarily on four states – Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Odisha – selected based on variations in the core independent variables of my argument.

This medium-N approach allows for a detailed, country-specific analysis of both the dependent variable of interest – the character of disaster preparedness – and the multiple potential explanations for variation in preparedness outcomes. The case studies developed and drawn on in the analysis are based on detailed in-country fieldwork and substantial examination of primary and secondary materials for each country.

The decision to use a case study model, rather than a large-N quantitative analysis, was driven both by the character of data on natural hazards and related policies. At a fundamental level, there are limits on the availability of appropriate data cross nationally. As noted by a joint World Bank and United Nations report on natural hazards, “While some countries attempt to collect and archive their hazard data, efforts are generally inconsistent or insufficient. Specifically, there are no universal standards for archiving environmental parameters for defining hazards and related data. Data exchange, hazard analysis, and hazard mapping thus become difficult” (World Bank and United Nations 2010: 3).

Measurement of hazard exposure is further complicated by “the inability to standardize sufficiently scales for the magnitude of a shock that is being used to measure hazard input” (Bussell and Colligan Reference Bussell and Colligan2014: 10). While significant progress has been made in standardized measurement of earthquakes, and recent efforts to measure cyclone intensity (Hsiang and Narita Reference Hsiang and Narita2012; Hsiang and Jina Reference Hsiang and Jina2014) also offer promise for standardized measurement, these are the exceptions, rather than the rule (Bussell and Colligan Reference Bussell and Colligan2014: 10). More commonly, measurement of factors such as rainfall offer only very indirect indicators of the potential for flood or drought and measurement of combined hazards, such as cyclones and rainfall, are even more limited (Bussell and Colligan Reference Bussell and Colligan2014: 10).

In the following sections, I develop measures of elite motivation and capacity at the country level and subnationally for India. I then use these measures to make predictions about the likely outcomes for overall levels of disaster preparedness. A summary of all measures for the included countries and subnational states is provided for reference in Tables 5A and 5B, with additional details in the relevant sections.

Table 5A Summary of all measures – country cases

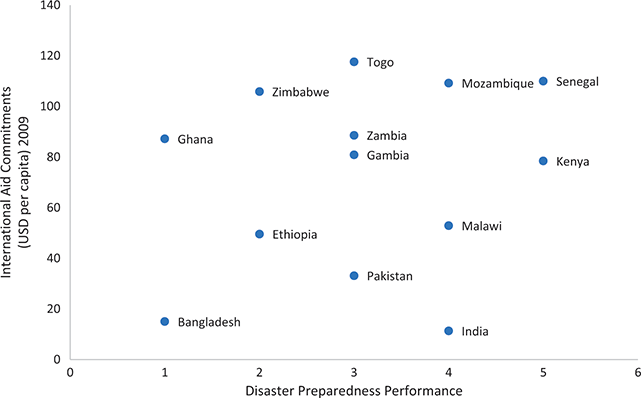

| Country | Natural Hazard Threat | Political Incentives | Capacity | Disaster Preparedness Performance | GSDP per Capita (USD) 1999−2000 | International Aid Commitment per Capita (USD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flood | Cyclone | Drought | Hazard Affected Share of Population | Opposition Threat | Expected Electoral Incentives | State Capacity | Civil Society Capacity | Expected Capacity Profile | ||||

| Bangladesh | Severe | Severe | Severe | High | High | High | Lower | Lower | Uncoordinated | Medium-High | 1,564 | 15 |

| Ethiopia | Low/ Moderate | Minimal | Severe | High | Medium | Medium-High | Lower | Lower | Uncoordinated | Medium-High | 757 | 50 |

| Gambia, The | High | Minimal | Low | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Higher | Society-Reliant | Low | 673 | 81 |

| Ghana | High | Minimal | Moderate | Low | High | Low-Medium | Higher | Higher | State-Led | Medium | 2,026 | 87 |

| India | Severe | Severe | Moderate | High | High | High | Higher | Lower | State-Dominant | High | 1,980 | 11 |

| Kenya | Low/ Moderate | Minimal | Severe | High | High | High | Lower | Higher | Society-Reliant | Low-Medium | 1,578 | 78 |

| Malawi | Severe | Moderate | Moderate/High | High | High | High | Higher | Lower | State-Dominant | Medium-High | 357 | 53 |

| Mozambique | Severe | Severe | Moderate | High | Medium | Medium-High | Lower | Higher | Society-Reliant | High | 441 | 109 |

| Pakistan | Severe | Minimal | High | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Lower | Uncoordinated | Medium | 1,467 | 33 |

| Senegal | High | Minimal | High | Low | Medium | Low | Higher | Higher | State-Led | Medium | 1,366 | 110 |

| Togo | High | Minimal | Low | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Higher | Society-Reliant | Low | 618 | 118 |

| Zambia | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | Medium | Medium-High | Higher | Lower | State-Dominant | Medium | 1,535 | 89 |

| Zimbabwe | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | Medium | Medium-High | Lower | Higher | Society-Reliant | Low-Medium | 1,548 | 106 |

Notes: The natural hazard threat profile for each state includes the three major hazard types faced by states in the study: flood, cyclone, and drought, and is based on country case reports, supplemented by data from the Global Risk Data Platform, UNEP/GRID-Europe, and Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019. The threat scoring range used here is: Minimal – Low – Moderate – High – Severe.

Table 5B Summary of all measures – Indian states

| State | Natural Hazard Threat | Political Incentives | Capacity | Disaster Preparedness Performance | GSDP per Capita (USD) 1999−2000 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flood | Cyclone | Drought | Hazard Affected Share of Population | Opposition Threat | Expected Electoral Incentives | State Capacity Coding | Civil Society Capacity | Overall Capacity | |||

| Andhra Pradesh | Low | High | Severe | Low | High | Low-Medium | Higher | Higher | High | Medium | 16980 |

| Assam | High | Minimal | Low | High | Medium | Medium-High | Lower | Higher | Medium (CS) | Medium-High | 13068 |

| Bihar | Severe | Minimal | Moderate | High | High | High | Lower | Lower | Low | Medium-High | 6048 |

| Chhattisgarh | Minimal | Minimal | Moderate | Low | Medium | Low | Higher | Lower | Medium (state) | Low | 13348 |

| Gujarat | Minimal | Moderate | Moderate | High | Medium | Medium-High | Higher | Lower | Medium (state) | High | 21681 |

| Haryana | Low | Minimal | Minimal | High | High | High | Lower | Lower | Low | Low-Medium | 24251 |

| Jharkhand | Minimal | Minimal | High | Low | Medium | Low | Lower | Lower | Low | Low | 12672 |

| Karnataka | Minimal | Low | Severe | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Lower | Low | Low-Medium | 18208 |

| Kerala | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High | Higher | Lower | Medium (state) | Medium-High | 21550 |

| Madhya Pradesh | Minimal | Minimal | High | Low | Medium | Low | Lower | Lower | Low | Low | 13278 |

| Maharashtra | Minimal | Low | Severe | Low | High | Low-Medium | Higher | Lower | Medium (state) | Medium-High | 25543 |

| Odisha | Low | High | Moderate | High | High | High | Lower | Higher | Medium (CS) | Medium-High | 11659 |

| Punjab | Moderate | Minimal | Minimal | High | High | High | Higher | Higher | High | Low | 27577 |

| Rajasthan | Minimal | Minimal | Severe | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Lower | Low | Medium | 14639 |

| Tamil Nadu | Minimal | High | High | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Lower | Low | High | 21502 |

| Uttar Pradesh | Moderate | Minimal | Low | Low | High | Low-Medium | Lower | Lower | Low | Low | 10539 |

| Uttarakhand | Minimal | Minimal | High | High | Medium | Low | Lower | Higher | Medium (CS) | Medium | 15061 |

| West Bengal | High | Severe | Low | Low | Medium | Low | Higher | Lower | Medium (state) | Low-Medium | 16861 |

* Natural hazard exposure scores based on Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019. The natural hazard threat profile for each state includes the three major hazard types faced by states in the study: flood, cyclone, and drought. The threat scoring range used here is: Minimal – Low – Moderate – High – Severe.

The application of my argument to the country and state cases, using the measures shown in Tables 5A and 5B, produces the set of empirical expectations shown in Tables 6A and 6B. I examine these expectations in detail in the following sections.

Table 6A Empirical expectations for disaster preparedness – country cases

| Political Incentives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | ||

| Capacity | Lower |

|

|

| Higher |

|

| |

Note: Countries in the bottom right quadrant should be the most likely to engage in disaster preparedness, while countries in the top left should be the least likely.

Table 6B Theoretical expectations for disaster preparedness – Indian states (cases in bold)

| Political Incentives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LowerFootnote 12 | Higher | ||

| Capacity | Lower |

|

|

| Higher |

|

| |

Note: Case states shown in bold. States in the bottom right quadrant should be the most likely to engage in disaster preparedness, while countries in the top left should be the least likely.

1.4 Section Overview

The remainder of this Element proceeds in the following manner. In the next section, I provide a detailed discussion of the analytic framework used to measure disaster preparedness and present the findings for preparedness in the country and subnational cases. I also present evidence showing that the primary existing arguments for the presence of, and variation in, disaster preparedness are insufficient for explaining observed variation in this detailed measure of preparedness.

Section 3 moves to analysis of elite motivation, considering both the character of past exposure to natural hazards in a country – as an indicator of the potential for observing the preparedness counterfactual – and the character of opposition threat. I present measures of these concepts and evaluate the argument based on qualitative discussion of India and examples from additional country cases.

In Section 4, I discuss in greater detail my argument for the importance of capacity in shaping disaster preparedness outcomes. I then present my measurement strategy for capacity and evaluate my theoretical expectations for the relevance of capacity to the character of disaster preparedness governance in the cases.

The final section offers a combined analysis to assess the overall findings and provides concluding thoughts. Here, I evaluate the ability of my argument to predict not only the character of disaster preparedness initiatives in terms of political support and institutional structures, but also the overall success of achieving disaster preparedness goals. I end with a consideration of what these findings entail for the future of disaster preparedness globally, particularly in the wake of climate change.

2 Assessing Preparedness

The motivating puzzle of this Element is the presence of, and variation in, disaster preparedness initiatives across a range of countries in the Global South. This section discusses the empirical approach taken in the study and documents the empirical variation that occurs in the country and state case studies. In the final section, I also provide evidence suggesting that existing explanations for disaster preparedness are insufficient for explaining the outcomes discussed here.

2.1 Empirical Approach – a Measurement Framework for Disaster Preparedness

The concept of disaster preparedness refers to the range of efforts that prepare for, and can reduce the effects of, natural hazards, with the potential to prevent a hazard from evolving into a natural disaster. This includes, generally, activities that reduce risks in wake of an anticipated hazard as well as programs that increase the efficiency of response to hazards when they occur. This can comprise a wide range of actions, which makes effective measurement of disaster preparedness an important task of this project.

As discussed in Section 1, it is difficult to develop standardized measures of disaster preparedness at the country level based on available hazard or past exposure data. Given this obstacle, I take a different approach in this study, which is to develop an index measure based on highly detailed analysis guided by a single evaluation framework. In other words, I compare the performance of each country and state case on the set of international standards for disaster preparedness that was in place at the time of the study. These standards are known as the Hyogo Framework and were adopted in 2005 at the World Conference on Disaster Reduction. The Framework was used to structure disaster-related policy efforts in the period 2005–2015.Footnote 13

These standards for disaster preparedness are focused on “priority” areas, which I refer to here as components of preparedness. For each component, examples of possible preparedness activities and outcomes serve as measures for evaluating performance in the cases. These components of preparedness, and measures of their presence, shown in Table 7, emphasize establishing a strong institutional foundation for disaster risk reduction, understanding local risk, minimizing risks, building a culture of safety and resilience, and strengthening disaster preparedness at all levels.

Table 7 Measuring disaster preparedness

| Components of Preparedness | Measures/Examples of Activities and Proposed Outcomes |

|---|---|

| 1. Ensuring that disaster risk reduction (DRR) is a national and a local priority with a strong institutional basis for implementation |

|

| 2. Identifying, assessing, and monitoring risks and enhancing early warning |

|

| 3. Using knowledge, innovation, and education to build a culture of safety and resilience at all levels |

|

| 4. Reducing the underlying risk factors |

|

| 5. Strengthening disaster preparedness for effective response at all levels |

|

2.2 Case Performance on Disaster Preparedness

Each country and subnational state in this study was evaluated against the measures of disaster preparedness components laid out in Table 7. In this section, I review the performance of the country and subnational cases. Table 8A summarizes each country’s performance relative to the other countries in the study, grouped into low, medium, and high performance on achieving the goals of each component. For India, Table 8B offers a breakdown of subnational performance in India’s eighteen largest states.

Table 8A Disaster preparedness performance by countryFootnote 14

| Country | Disaster Preparedness Components Scores | Summary Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Political Priority | 2: Assessment & Monitoring | 3: Culture of Safety | 4: Risk Reduction | 5: Response Preparedness | ||

| India | High | High | High | High | High | High |

| Mozambique | High | Medium | High | High | High | High |

| Bangladesh | High | High | High | Low | Medium | Medium-High |

| Ethiopia | High | High | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium-High |

| Malawi | Medium | Medium | Medium | High | High | Medium-High |

| Pakistan | Medium | High | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Zambia | High | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Ghana | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Senegal | Medium | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Kenya | Low | High | Medium | Medium | Low | Low-Medium |

| Zimbabwe | Low | Medium | High | Low | Low | Low-Medium |

| Gambia, The | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Togo | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Note: Scores represent country performance on achieving the goals established for each component, relative to other countries in the study.

Table 8B Disaster preparedness performance by Indian states

| State | Disaster Preparedness Components Scores | Summary Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: Political Priority | 2: Assessment & Monitoring | 4: Risk Reduction | 5: Response Preparedness | ||

| Gujarat | High | High | High | High | High |

| Tamil Nadu | Medium | Medium-High | High | High | High |

| Assam | High | High | Low | High | Medium-High |

| Maharashtra | High | Low-Medium | Low-Medium | High | Medium-High |

| Odisha | High | Medium | Low | Medium-High | Medium-High |

| Kerala | Medium-High | Low-Medium | Medium | High | Medium-High |

| Bihar | High | Medium | Medium-High | Medium | Medium-High |

| Andhra Pradesh | Medium | Medium-High | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Rajasthan | High | Low-Medium | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Uttarakhand | Medium-High | Low-Medium | Low | Medium | Medium |

| West Bengal | Medium-High | Low | Low-Medium | Medium | Low-Medium |

| Karnataka | Low-Medium | Medium-High | Low | Medium | Low-Medium |

| Haryana | Medium-High | Low | Low | Medium | Low-Medium |

| Madhya Pradesh | Medium-High | Low | Low | Low-Medium | Low |

| Punjab | Low-Medium | Low | Low | Medium | Low |

| Uttar Pradesh | Low-Medium | Low | Low | Low-Medium | Low |

| Chhattisgarh | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Jharkhand | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

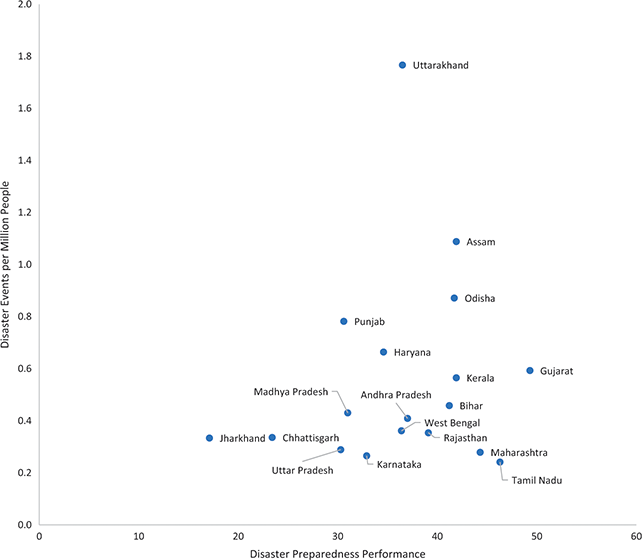

Notes: Scores represent state performance on achieving the goals established for each component. Scores based on data from Chakrabarti (Reference Chakrabarti2019), which incorporates measures that broadly cover the range of international standards, apart from component #3, which I exclude here for that reason. This study was conducted in 2017, more recently than the country-level evaluations developed more generally in this study, but focuses primarily on achievements during the Hyogo period. Bold indicates states cases considered in detailed in subsequent sections. The coding rule for categorization is: Low<30, Low-Medium 30–34, Medium 35–39, Medium-High 40–44, High >44.

In the remainder of this section, I present evidence on the dependent variable – disaster preparedness – with a summary of country case, and subnational Indian case, performance on each component of disaster preparedness. I begin each subsection with presentation of the Indian case, to characterize high performance, relative to the other countries in this study. While India has not necessarily implemented every international standard in full, it has made concerted efforts that highlight a considerable dedication to achieving disaster preparedness. At the same time, I provide details on the performance of four subnational cases, the states of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Odisha (shown in bold in Table 8B), to demonstrate variations in performance within this country. I then consider the additional country cases, beginning with higher performers and then moving to those demonstrating lower preparedness.

2.2.1 Component 1 – Making Disaster Risk Reduction a (Political) Priority

In the best cases, political attention to disaster risk reduction is reflected in the presence of a central government body that is established through formal policies, active in disaster-related planning and implementation, and that incorporates both public and private agencies into its processes. This body should be linked to, and actively engaged with, lower-level bodies that are also officially responsible for disaster-related planning. Government bodies are also actively engaged with community actors.

2.2.1.1 India

In India, central government attention to the issues of natural disasters emerged in the late 1990s. The High Powered Committee (HPC) on Disaster Management was initiated in 1999 to provide recommendations on disaster management plans. As the committee’s report notes, their work over two years “followed a highly process-oriented and participatory approach at the national, state and district levels involving all concerned governments, ministries, departments, scientific, technical, research & development organizations, social science institutions and covering more than a hundred nongovernmental organizations. Care was also taken to consult a representative cross-section of urban local bodies as well as Panchayati Raj institutions”Footnote 15 (National Centre for Disaster Management 2002: xv). This substantial effort resulted in a detailed set of recommendations covering the full range of actions subsequently put forward as international standards.

Further central government action in response to the HPC report emerged with the passing of a Disaster Management Act (DMA) in 2005. This policy instituted a central government agency for dealing with natural hazards – the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) – in addition to two complementary central organizations, the National Defense Response Force (NRDF), as a part of the military apparatus, and the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM), for research and training. Subnationally, the DMA also mandates creation of state- and district-level Disaster Management Authorities, like those previously established in some states (discussed next), which are responsible for implementing national programs and developing their own disaster management plans. The NDMA is intended to interact both with other relevant national bodies, including the NDRF and line ministries, and state-level disaster management authorities, who themselves interact with the relevant district-level officials (Sarma Reference Sarma2015). The DMA was followed by a Disaster Management Policy (DMP) in 2009 to elaborate disaster preparedness strategies.

These initiatives, while highly comprehensive and indicative of government support for disaster preparedness, have not been received without critique. Three primary concerns are worth noting here. First, while new organizations were created, the responsibility of these organizations relative to pre-existing departments, ministries, and committees has not always been clear. This has resulted in stalled progress in some areas, particularly where there is shared responsibility across departments (Ministry of Home Affairs, GoI 2013, xviii). Second, proposed Disaster Mitigation Funds were only rarely implemented seven years after the passing of the Act (Ministry of Home Affairs, GoI 2013, xxii; Bahadur et al. Reference Bahadur, Lovell and Pichon2016). It was also unclear the extent to which individual ministries had implemented the recommendation to make clear provisions in their budgets for preparedness and response efforts. Third, some analysts critiqued the highly state-oriented approach of these policies. While non-state actors – both nonprofits and businesses – are discussed in the DMA and DMP as important contributors to disaster management, the specific provisions for, and evidence of, including these actors is minimal (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 8–14; Martin Reference Martin2007).

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, a small number of state governments, led by Odisha and Gujarat, launched their own disaster management authorities. Most other states did not implement an authority until after the central government mandate in 2005, including Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. The content of these state efforts was generally similar, especially after the guidance provided by the central government act.

2.2.1.2 African and other South Asian Country Cases

In other high-performing country cases, there is similar evidence of governments building institutions to organize preparedness efforts and reduce disaster risks. In Mozambique, for example, this body is the National Institute of Disaster Management (Instituto Nacional de Gestao de Calamindades, or INGC), created in 1999, which is additionally enabled by the Master Plan for Disaster Prevention and Mitigation (MPPMND), approved in 2006. “In terms of the national platform for DRR, the INGC is the clear nodal body for managing disaster preparedness and response” (Bussell & Malcomb Reference Bussell and Malcomb2014: 147), coordinating all activities related to natural hazards and organizing regular meetings with representatives from all active public and private organizations for both planning and response.

The middle-range scoring countries on this component also tend to have established national platforms for allocating responsibilities related to disaster preparedness and response, but these platforms are both less likely to incorporate risk reduction and less likely to be fully implemented at all levels of government. For example, “While an institutional framework for disaster risk management does theoretically exist in Senegal, the complicated organization and undefined relationships between actors within the system render it weak” (Agnihotri et al. Reference Agnihotri, Child, Koob and Wald2014: 32). In the Senegalese case, “The Directorate for Civil Protection (DPC) is the institutional hub of DRM,” but “[d]espite the existence of the DPC … responsibility and liability for DRM is diffuse across several organizations and depends on the type of disaster” (Agnihotri et al. Reference Agnihotri, Child, Koob and Wald2014: 33–34).

In the lowest scoring countries, while there may be official bodies tasked with disaster-related activities, there are often not comprehensive national platforms and de facto responsibility often falls to civil society. In Kenya, while the National Disaster Operations Center (NDOC) is responsible for coordinating disaster management, the lack of a national disaster policy limited both the NDOC’s ability to expand beyond disaster management activities and to coordinate across diverse actors (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Tripson, Ven Johnson and Ven Johnson2014: 112). Thus, while civil society is active in disaster response in Kenya, these activities are often not well coordinated or expanded to include disaster preparedness and risk reduction.

2.2.2 Component 2 – Assessing Risks and Enhancing Early Warning

The second component of disaster preparedness concerns the ability of national governments to anticipate future hazards through active risk assessment, monitoring of potential hazards, and programs for early warning. While there remain limitations on risk assessment, monitoring, and early warning practices in all the countries considered here, those performing well on this measure exhibit a range of tools and techniques for collecting and managing information on natural hazards. In general, these countries have established national systems in place and, often, are partnering with international actors to manage comprehensive programs that account for a range of different hazards in their area.

2.2.2.1 India

Risk assessment and early warning procedures are directly addressed in India’s disaster management legislation (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 16). Subsequent to the Disaster Management Act, the government implemented a multi-hazard assessment framework, which takes inputs from government agencies, including, among others, the Central Water Commission (flooding), Geological Survey of India (landslides), the India Meteorological Department (multiple hazards), and the National Drought Assessment and Monitoring System. A Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project and overall Disaster Management Support System within the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) are also contributing to hazard assessment. An overall hazard risk assessment report was also released in 2019 (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019).

An area of recent improvement in India is early warning. A combined effort of multiple government organizations, including the Indian Meteorological Department and ISRO, has advanced threat information and warning protocols related to floods, tsunamis, and cyclones, which, combined with other preparedness initiatives, have resulted in substantially reduced loss of life at the time of hazards.

Yet, these efforts are constrained by limited human resources with expertise in loss modeling. Stronger mechanisms for sharing information across agencies and levels of government are also needed, alongside further improvements in last mile connectivity (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 18–20). In addition, the success of early warning efforts depends on the willingness of individuals to respond to an imminent threat. In India, there is evidence that individuals who have not previously faced a natural hazard can be more reticent about following evacuation protocols (Odisha State Government Official #2, 2014). These challenges must be addressed with improved education programs, as discussed in greater detail next.

Activities at the state level suggest that there is variation in the status of risk assessment and early warning within the overall Indian context. Gujarat was the first state to embark on a comprehensive vulnerability assessment, which examined major natural and industrial hazard risks geolocated to the sub-district level. The state has also conducted detailed hazard-specific assessments in particularly vulnerable regions (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 133).

With early warning, “[d]issemination of early warnings has been institutionalized in states like Odisha and Gujarat through SOPs [standard operating procedures] and standing orders, as well as the provision of financial, administrative and logistic arrangements at all levels” (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 184). These systems have been credited with improved early cyclone warning in Gujarat and Odisha, where early evacuations are seen to have saved thousands of lives (Singh Reference Singh2023).

For risk assessment, Odisha has made substantial progress on assessing overall vulnerabilities. It is also making substantial information on the mapping of vulnerabilities available to the public both digitally and through other information dissemination practices. One area for improvement is in establishing local strategies for real time data collection on risks and active hazards (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 143).

Andhra Pradesh performs better here than on other areas of disaster preparedness, primarily due to clear investments in multiple forms of risk monitoring. The state set up a cyclone early warning system through the central government’s Cyclone Hazard Mitigation Project and developed a forecasting system for droughts (Tejaswi and Kumar Reference Tejaswi and Kumar2011: 445–447). More generally, the Andhra Pradesh State Development and Planning Society (APSDMPS) has its own Early Warning Center, which includes automated weather stations, river gauges, coastal stations, and reservoir level recorders to collect hazard-relevant weather data in the state (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 135).

Karnataka implemented the Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Centre (KSNDMC), which initially focused on drought monitoring inputs. The center has subsequently been expanding to collect data on other hazards, including rain gauges and weather stations (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 136). This reflects good initiative on monitoring, but less overall progress in this area than the other three state cases.

2.2.2.2 African and Other South Asian Country Cases

Ethiopia is an example of a relatively high-performing case in which “All assessment activities are government-led and results from assessments must have the government’s approval and sign off before they can be released” (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Tripson, Ven Johnson and Ven Johnson2014: 104). Assessments are conducted regularly through a government–NGO partnership. Hazard monitoring is also coordinated and cooperative, with a range of data collected by both national organizations and international organizations, including the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS-NET) (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Tripson, Ven Johnson and Ven Johnson2014: 105).

Countries in the medium category on Component 2 typically had some form of monitoring system in place, but this system generally drew on information from a smaller number of resources and was not fully implemented. Coordination between organizations that could feasibly contribute to risk assessment and monitoring activities was also less evident. Ghana offers an example of a country with an established Hydro Meteorological Agency to monitor weather trends and technical advisory committees within the national disaster management body tasked with identifying and assessing hazards. However, due to limited training of the committee members, these activities have minimal relevance for predicting future hazards. In addition, a lack of coordination between ministries places limitations on the ability of the government to effectively issue early warnings in the face of an active hazard (DeCuir et al. Reference DeCuir, Fuerst, Iannuzzi and Leaver2014: 71).

Finally, those countries falling in the low category of performance exhibit only token monitoring, assessment, and warning capacities. In Togo, no multi-risk assessments had been conducted at the time of research, with the maps of disaster risk that were available focusing exclusively on floods. A Red Cross–developed early warning system exists, but it is focused on local water-level indicators and not linked to any national-level communication systems.

2.2.3 Component 3 – Building a Culture of Safety and Resilience

Developing a culture of safety is at the heart of the third disaster preparedness component. In this evaluation, I focus primarily on information sharing within government at the central level, as well as educational and awareness programs.

2.2.3.1 India

In India, the National Institute for Disaster Management (NIDM) serves as the central body for disaster-related training and information dissemination, primarily, but not exclusively, targeted toward government actors. This involves multiple initiatives. First, representatives of local urban and village bodies, as well as officials at higher levels of government, are trained in disaster management through the NIDM. The National Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, established in 2013 under the NIDM, serves as a multi-stakeholder body to offer regular forums for information and experience sharing across government, NGOs, the academy, and the private sector. NIDM also hosts the India Disaster Resource Network, which is an online, searchable repository for information on hazard-related equipment and human resources available in each district.

Within the public education system, the Central Board of Secondary Education (SBSE) has developed a Disaster Management curriculum that is being implemented, while primary schools have initiated activity-based programming, alongside a general National School Safety Programme. University-level programs have also been introduced as disaster management courses and professional programs (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 24).

For the public at large, educational programs have been led by the NDMA. This includes awareness initiatives such as promoting International Disaster Risk Reduction Day and holding mock hazard drills. The NDRF also engages in local capacity building initiatives, which help to encourage awareness (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 27).

The success of these efforts could be increased by improved regular communication between various relevant actors and additional efforts to maximize access to, and use of, available databases. There is also a general need to develop a wider base of disaster management professionals and researchers to support overall efforts (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 26).

2.2.3.2 African and other South Asian Cases

Additional countries doing well on Component 3 tend to have developed programs to incorporate hazard- and disaster-related training into school curricula and community training programs. Bangladesh “has included disaster preparedness and information on early warning systems in the national curriculum of the country” for more than two decades, and primary schools often serve a dual role as cyclone shelters (Shabhanaz & Bussell Reference Shabhanaz and Bussell2017: 23).

In the countries categorized as medium on this component, field research suggested that most governments were beginning to incorporate disaster-related training at the university level or that NGOs were developing training programs. But these initiatives did not extend to local levels where they would be likely to affect day-to-day concerns of the population. In Malawi, there was a discussion of efforts to introduce disaster-related training into the primary and secondary school curriculum; however, there was little evidence of this in practice (Bussell & Malcomb Reference Bussell and Malcomb2014: 140). That said, universities were already “integrating programs and courses on DRM material in hopes that these higher-level students will become the next generation of policy makers and practitioners” (Bussell & Malcomb Reference Bussell and Malcomb2014: 140).

The lack of communications and training programs in low-scoring countries is quite striking. In the Gambia, there was little evidence of the government using “knowledge, innovation, and education to build a culture of safety and resilience” (Agnihotri et al. Reference Agnihotri, Child, Koob and Wald2014: 41). In addition, training of local-level community organizations on disaster preparedness appeared to be absent (Agnihotri et al. Reference Agnihotri, Child, Koob and Wald2014: 41).

2.2.4 Component 4 – Reducing Underlying Risk Factors

The fourth component focuses on mitigation and risk reduction, particularly in the context of climate change. The emphasis here is on policies and practices to reduce the overall risk that a natural hazard will evolve into a disaster. Thus, these are efforts that go beyond preparing for what to do when a hazard occurs and instead emphasize ways to change and improve practices to limit the threats associated with hazards. In practice, these are the types of activities that were rarely observed in fieldwork, as most countries are still focused on immediate response activities and, at best, efforts to prepare for hazards. Nonetheless, there are some concerted efforts, especially in those countries scoring relatively high in this area.

2.2.4.1 India

The Indian approach combines agriculture-focused programs, general social welfare initiatives, and post-disaster recovery (Sarma Reference Sarma2015). The agriculture-specific programs – the National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (AMSA) and National Initiative on Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA) – are developing programs that help to make the agricultural sector resilient to climate change and associated natural hazards. For social welfare, a wide range of programs provide resources that may contribute to general disaster resilience. These include the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), a combined employment and rural development program that implements risk reduction programs; Indira Awas Yojana, a rural housing program that incorporates disaster resilient design; and multiple agricultural insurance programs to reduce the risks of hazards to farmers (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 31). After a hazard occurs, the government now emphasizes rebuilding in ways that reduce the risk of disaster at the time of future hazards. All these activities suggest clear attention to the ways communities can develop specialized risk reduction practices specific to their own context.

Three primary areas of concern remain regarding risk reduction. First, it is not clear how the climate-oriented programs are, if at all, directly integrated into programs led by disaster management-oriented agencies. Second, many of the social and economic welfare programs expected to provide the foundation for resilience have themselves faced substantial critiques.Footnote 16 Finally, enforcement of hazard-related regulations is seen to be lacking. As one analyst notes regarding disaster-oriented building codes, there remain actors who perceive “that adding disaster resilient features into the structural design may be costly and not much effective” (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 35). This demonstrates the need for continued public education programs and increases the “need to establish adequate compliance mechanism at local level to implement these tools” (Sarma Reference Sarma2015: 35).

In the subnational cases, all four states considered in depth here participated in the first phase of a substantial Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project (NCRMP), in partnership with the central government and World Bank. This effort included “improved access to cyclone shelters, evacuation and protection against storms and flooding, strengthened early warning dissemination systems and enhanced capacity of local communities” (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 148). The program builds on previous efforts in Odisha specifically to construct cyclone shelters in the state “through the construction of link roads, facilitating evacuation of people to the shelters at short notice” (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 152).

In addition to these measures, Gujarat has been recognized for providing regular grants to the state disaster management authority to implement risk mitigation projects (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 151). Yet, at the time of this study, none of the four case states had set up the standalone State Disaster Mitigation Funds as outlined in the central government policy.

Overall, Gujarat’s relatively strong performance on this component comes from substantial cyclone and earthquake risk mitigation projects, which include introduction of new safety standards for construction and auditing/retrofitting of lifeline structures, such as hospitals (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 153). In Odisha, relocation programs for individuals living in high-risk cyclone areas have complemented other mitigation activities. Andhra Pradesh performs somewhat better than Karnataka, mainly based on having implemented more comprehensive cyclone and flood shelter initiatives (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 154).

2.2.4.2 African and other South Asian Country Cases

The primary model of DRR in higher-performing countries is a focus on sustainable livelihoods initiatives. In Malawi, “Environmental and natural resource management is a new and emerging concept at the community level where village participation and protection of nearby resources is the goal of many rural livelihood projects” (Bussell & Malcomb Reference Bussell and Malcomb2014: 141).

In countries that fall in the medium category regarding disaster risk reduction, there tends to be an awareness of DRR as a goal, and potentially some initial moves to incorporate this into policy, but little evidence of specific program implementation on the ground. The Pakistan National Disaster Management Plan includes attention to DRR and how different organizations should work together toward this goal, but the funding to support implementation has been limited. In these cases, the shorter-term demand for resources to support disaster response was generally overwhelming efforts to mainstream DRR into day-to-day policies.

In the remainder of the country cases, while disaster risk reduction may be on the radar of policymakers, no clear efforts have been made to pursue DRR efforts. For example, improved building practices, which can substantially reduce risks in many urban areas, were markedly absent in these cases. In Ghana, for example, where urban flooding is a primary hazard, building codes had not been updated since the 1920s, despite efforts by international organizations to promote better, more resilient, building practices” (DeCuir et al. Reference DeCuir, Fuerst, Iannuzzi and Leaver2014: 71).

2.2.5 Component 5 – Preparedness for Response to Natural Hazards

The final disaster preparedness component concerns a country’s overall approach to preparedness. In those countries exhibiting relatively high performance, the authority(ies) for organizing and implementing disaster management protocols is(are) clear, there are funds allocated to these activities, and there are subnational programs in place related to disaster response.

2.2.5.1 India

As discussed for the first component, India has developed a robust institutional infrastructure, with the NDMA responsible for national-level planning, state governments responsible for state-specific planning and immediate response activities, the NIDM in charge of training and research initiatives, and the NDRF available on an as-needed basis at the time of a natural hazard. Overall, many state governments have also followed through on the mandate to develop their own specific disaster management plans and are allocating resources directly to preparedness activities (Odisha State Government Official #1, 2014; Sarma Reference Sarma2015).

Perhaps the key area of concern for preparedness that has not been mentioned is the need to foster continued mainstreaming of preparedness across all aspects of government. This includes building preparedness into the ongoing activities of all departments, as well as into future planning initiatives.

In the states, key considerations for preparedness include the presence and functioning of emergency Operations Centers (EOCs), both in the state capital and in the districts; implementing a disaster communication system; ensuring that medical facilities are equipped for natural hazard casualties; engaging in scenarios and mock drills; and the preparation of contingency plans. Gujarat displayed reasonable progress in each of these areas, including the use of state-of-the-art communications equipment in the EOCs. The state has also developed hazard-related manuals with standard operating procedures for use in advance of and during hazard events (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 187).

Odisha has been widely recognized for its improved preparedness levels over the last fifteen years (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2019: 182). This can be attributed not only to the early warning and mitigation efforts discussed earlier, but also to establishment of clear procedures in the face of an impending hazard, alongside community-based awareness efforts, which have made evacuation and related procedures more effective at the time of tropical storms and cyclones. There remains room for improvement in Odisha in the areas of medical facility preparation and scenario planning/mock drills.

Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have similar preparedness profiles, with Andhra performing slightly better in areas such as the disaster communication system and implementation of mock drills. In both cases, the states have made some progress in preparedness activities, but have not excelled in any area.