Introduction

Employee improvisation refers to a behavioural process in which individuals consciously use the resources at hand to deal with complex and unexpected situations on the spot in creative, situational ways that integrate planning and execution at the same time (Xiong, Reference Xiong2022). Since the world entered the era of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, the market environment has become increasingly turbulent. To cope with never-ending changes in demand, companies have increasingly valued the improvisation of frontline employees. Unlike general planned innovation, improvisation is more about an individual’s conscious choices in the moment. Specifically, improvisation refers to fabricating and inventing novel responses without a pre-determined plan and without any assurance of the outcome in the near future (Cunha, Cunha, & Kamoche, Reference Cunha, Cunha and Kamoche1999). To encourage its occurrence, a relatively relaxed atmosphere in the organization or team is critical. Additionally, improvisation is also not only about trying new ideas but also about seizing fleeting opportunities or responding to threats quickly, so having the power to make on-the-spot decisions is essential, especially with the authorization of direct team supervisors (Cunha, Cunha, & Kamoche, Reference Cunha, Cunha and Kamoche1999). Nevertheless, under the influence of Confucianism and cultural values of familism, even in the context of great uncertainty, many company leaders in eastern countries, particularly in China, have resisted changing their paternalistic leadership styles, or ‘patriarchal styles,’ among which authoritarian leadership places the greatest emphasis on obedience (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Boer, Chou, Huang, Yoneyama, Shim and Tsai2014; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). For example, there are many authoritarian leaders in some family companies in China whose behaviours inhibit the generation of professional suggestions and, in turn, the sustainable growth of their businesses (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Studies have also shown that authoritarian leadership’s emphasis on personal authority exerts many negative effects on employees. For instance, Gu, Wang, Liu, Song, and He (Reference Gu, Wang, Liu, Song and He2018) have pointed out that the ‘arbitrary centralization’ of authoritarian leadership may limit employees’ creativity. By extension, this paper argues that the behavioural style of authoritarian leadership may also have restraining effects on employees’ improvisation.

As shown in the literature, most past studies on leadership’s relationship with improvisation have focused on positive leadership, including in terms of flexibility (Lombardi, Cunha, & Giustiniano, Reference Lombardi, Cunha and Giustiniano2021), service-orientation (Cunha, Cunha, & Kamoche, Reference Cunha, Cunha and Kamoche1999), and empowerment (Magni & Maruping, Reference Magni and Maruping2013). By contrast, little is known about what kind of leadership might curb improvisation and its working principles. According to social information processing theory, subordinates consciously process the behaviour-related information conveyed by their leaders in their daily work and communication and, in response, generate cognitive evaluations and behavioural feedback (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978). Thus, it is not difficult to infer that, as a leadership style with distinct characteristics when it comes to information processing, authoritarian leadership is marked by strictness with subordinates and emphasizes obedience (Cheng, Chou, Chou, & Cheng, Reference Cheng, Chou, Chou and Cheng2019). Coupled with the experience that subordinates who have made mistakes in the past have been criticized and censured, authoritarian leadership is likely to make subordinates feel that their leaders are highly intolerant, which discourages their enthusiasm to improvise. As a result, the mechanism by which authoritarian leadership inhibits subordinates’ improvisation, as proposed in this paper, may be subordinates’ perceptions of their managers’ high intolerance of errors.

Even so, are subordinates under authoritarian leaders necessarily afraid to improvise? That possibility raises two questions that need to be answered. The first is whether the negative effects of authoritarian leadership are the same for all subordinates, or what this paper calls ‘relationship’ (Reflecting environmental factors at the interpersonal level). The second is whether its negative effects are consistent across all tasks, or what this paper calls ‘task environment’ (Reflecting environmental factors at the task level). For the sake of answering those questions, the paper introduces the concepts of the leader–member exchange (LMX) relationship and task complexity for further discussion.

LMX reflects subordinates’ perceived understanding and trust of leaders and their relationships with each other (Zhou, Rasool, Yang, & Asghar, Reference Zhou, Rasool, Yang and Asghar2021). In traditional Eastern societies, the relationship between superiors and subordinates was characterized by an unequal distribution of rights, with superiors expecting their subordinates to obey them, show respect, and trust in their authority, which are essential components of a high LMX (Graen & Uhl Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl Bien1995). Thus, authoritarian leadership and high LMX can coexist in the Eastern workplaces. Depending on the quality of the relationships between subordinates and leaders, their interpretation of information may be different. For instance, because subordinates with high LMX quality receive more supportive information and trust from authoritarian leaders, they may perceive that management has less intolerance for errors (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978) and thus dare to improvise more. Previous research has also indirectly confirmed this viewpoint. Research on attributions has demonstrated that managers’ assessment of a subordinate’s performance, including any mistakes made, is affected by the exchange relationship between them (Duarte, Goodson, & Klich, Reference Duarte, Goodson and Klich1994; Heneman, Greenberger, & Anonyuo, Reference Heneman, Greenberger and Anonyuo1989), thus leading to a more lenient evaluation of mistakes made by subordinates with a high LMX. Consequently, those subordinates with high LMX may be more leniently treated for the same level of errors, leading them to perceive a lower level of managerial intolerance of errors under authoritarian leadership.

Task complexity, characterized in terms of uncertainty and difficulty, is one of the most important factors in the task environment (Jia, Shaw, Tsui, & Park, Reference Jia, Shaw, Tsui and Park2014). According to social information processing theory, the task environment can influence individuals’ behaviour and perception (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978); thus, when faced with tasks of varying complexity, subordinates may perceive different extents to which their managers tolerate errors. However, in task environments marked by high task complexity, the non-occurrence of errors all the way from executive leadership down to low-level employees is rare. For that reason, high task complexity may make it impossible to strictly follow planned operations and, in turn, convince employees that mistakes are inevitable and that leaders should be considerate. With that mindset, they may dare to improvise.

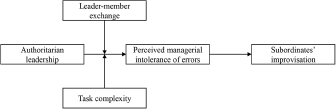

Considering all the above, the study presented in this paper involved constructing a conditional indirect effect model integrating relationship and task environment, as shown in Fig. 1, to systematically investigate the influence and mechanism of authoritarian leadership on subordinates’ improvisation. SPSS and Mplus were employed to conduct a moderated mediating effect analysis to test several hypotheses using data from an empirical survey of 319 first-line teams of Chinese cultural background. Presenting the results, this paper not only for the first-time reports on the negative leadership antecedent of individual improvisation but also reveals the how that leadership style differently affects the improvisation of different subordinates in different task environments. It thus offers guidance for how Chinese companies can operate effectively regulate the level of improvisation among frontline subordinates at different levels within their organizations.

Figure 1. Research model.

Theoretical analysis and hypotheses

Authoritarian leadership and perceived managerial intolerance of errors

Authoritarian leadership can be defined as the behavioural style in which a leader maintains their authority and control over subordinates by imposing strict discipline on them and forcing them to obey (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Chou and Cheng2019). Early studies have shown that leaders with a strong authoritarian style usually exhibit various means of establishing eminence in their daily interactions with subordinates, including image grooming and arbitrary use of their power (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Working with such leaders, subordinates may develop the belief that they are likely to be blamed if they deviate from plans or make mistakes on assignments, because such acts imply an offense to the leader’s authority and a blow to their image. Per social information processing theory, a person’s social environment provides a variety of social information that affects their psychological state (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978). In daily work, subordinates’ perception often begins in a task environment where social information is available, and leaders, given their special status, determine what kinds of behaviour are encouraged or banned, for example, in the workplace (Yang & Wen, Reference Yang and Wen2021). Consequently, it is not difficult to speculate that authoritarian leaders’ behaviours of establishing eminence are likely to greatly affect subordinates’ perception.

Following that logic, authoritarian leadership may influence subordinates perceived managerial intolerance of errors, defined as subordinates’ perceptions of leaders’ attitudes and/or tendencies towards common mistakes (Zhao, Reference Zhao2011). Zhao’s (Reference Zhao2011) research has illustrated that when a team operates in an environment in which mistakes and censure go hand in hand, subordinates usually perceive a higher level of managerial intolerance of errors. From the perspective of social information processing theory, when authoritarian leaders frequently display behaviours of establishing eminence (e.g., image grooming and arbitrarily exercising power) in task environments, they may send a strong message to subordinates that mistakes will end in punishment. Added to that, leaders who exhibit a strong authoritarian style usually prioritize performance and engage in ‘educational’ behaviour (e.g., criticizing low performance) as a means to urge subordinates to achieve high performance and surpass competitors (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Chou and Cheng2019). Subordinates tend to interpret those social messages as their authoritarian leaders’ refusal to permit mistakes of any kind and thus their greater intolerance of errors. Due to the pre-set negative cognition of mistakes, subordinates may believe that their mistakes will make it difficult to achieve the high performance expected by authoritarian leaders and that, with them as the chief culprit, they will be blamed. Thus, we inferred that leaders who exhibit an authoritarian style are likely to be perceived by their subordinates as being intolerant of leadership. More formally, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1: Authoritarian leadership positively affects perceived managerial intolerance of errors.

Perceived managerial intolerance of errors and subordinates’ improvisation

As can be inferred from the above, improvisation is a stress-induced strategy deliberately adopted by subordinates in combination with resources at hand when they encounter unexpected events, and, as such, it is neither inherently good nor inherently bad (Vera & Crossan, Reference Vera and Crossan2005). That is, improvisation can have different outcomes depending on the suitability of the improvisation for the situation and the characteristics of the resources at hand. Improvisation is thus clearly a trial-and-error behaviour involving risks (Miner, Bassof, & Moorman, Reference Miner, Bassof and Moorman2001), including the risk that mistakes are made, meaning that improvisation among subordinates inevitably relates to superiors’ attitude towards mistakes. In turn, leaders’ intolerance of mistakes affects subordinates’ emotional, cognitive, and behavioural responses to trial-and-error behaviour (Zhao, Reference Zhao2011). Consequently, the perceived managerial intolerance of errors can be expected to negatively impact subordinates’ improvisational behaviour.

Specifically, subordinates may predict the short-term outcomes and risks of improvisation – that is, from the generation of improvisational ideas to their implementation – by combining their perceived managerial intolerance of errors with aspects of social information processing theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978). When subordinates perceive that their leaders, particularly ones with long-standing eminence, are highly intolerant of mistakes, they may develop the belief that improvisation is so risky that they dare not improvise even upon encountering unexpected problems. On the contrary, when leaders are perceived as having a relatively high tolerance for errors, then subordinates may feel that if they solve problems efficiently and in flexible ways that, even if they make some mistakes, their leaders will not blame them too harshly. As a result, such subordinates come to perceive less risk in improvising on the job and may dare to rise to the occasion when needed. Under relatively intolerant leaders, however, subordinates may feel that they are merely executing a plan mechanically without any room for trial and error and thus lose the motivation to solve emergent problems independently instead of reporting them or negotiating them in compliance with protocol. In those environments, subordinates’ negative experiences with making mistakes may eventually become so profound amidst the continued reinforcement of a perceived managerial intolerance of errors that they become highly sensitive to making mistakes and thus reject trial-and-error behaviours altogether. The result is a vicious cycle that weakens their willingness to improvise and their effectiveness in doing so. In sum, perceived managerial intolerance of errors can be expected to cause subordinates to form a habit of being apprehensive when dealing with urgent matters, which may inhibit their improvisation. Thus, we also hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived managerial intolerance of errors negatively affects subordinates’ improvisational behaviour.

The mediating role of perceived managerial intolerance of errors

Social information processing theory maintains that individual behaviour follows the response paradigm of information → perception → behaviour → output. Following that logic, we propose that authoritarian leadership, as an important source of information in the workplace, is likely to influence subordinates’ improvisation by affecting their perceived managerial intolerance of errors.

Authoritarian leadership’s emphasis on the authority of the leader and the obedience of subordinates discourages subordinates from daring to deviate from plans. Even in the face of sudden problems, such subordinates, out of reverence for their authoritarian leaders, will most likely only act in conformance with the plan and dare not stray without authorization. At the same time, such leadership also emphasizes high performance, as well as the condemnation of low performance and individuals who make mistakes (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Chou and Cheng2019). Consequently, subordinates do not dare to take responsibility or to make too many attempts at solving problems out of fear of making mistakes. Beyond that, authoritarian leaders are typically reluctant to share key information with subordinates (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Chou and Cheng2019), which makes it difficult for them to have a clear understanding of problems and, in turn, further discourages them from making any rash moves. In time, for authoritarian leaders, who are accustomed to instilling their experience into subordinates as one might stuff a duck (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Chou and Cheng2019), due to restricting their subordinates’ frames of thinking, stifle any message that improvisation is desirable. For those reasons, authoritarian leaders likely curb the development of their subordinates’ improvisational behaviours to a certain extent.

From the above, authoritarian leadership, of all types of leadership behaviour, essentially conveys to subordinates the message that all mistakes will be investigated and that all parties at fault will be punished. Subordinates, by extension, naturally interpret that message as information supporting a perception of their managers’ intolerance of errors (Yang & Wen, Reference Yang and Wen2021). In other words, the effects of authoritarian leadership on subordinates’ improvisation are mediated by a perceived managerial intolerance of errors. Accordingly, we inferred that authoritarian leadership may be an indirect restraint upon subordinates’ improvisational behaviour by way of such perceived intolerance. Thus, our third hypothesis was as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Perceived managerial intolerance of errors mediates the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation.

Conditional indirect effects between LMX-based authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation

LMX refers to the quality of the relationship between leaders and subordinates, as well as the degree of leader–subordinate exchange and interaction in terms of useful resources and emotional support (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Rasool, Yang and Asghar2021). Unlike abusive leadership, which achieves informal control over subordinates through social interaction (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000), authoritarian leadership is rooted in the legitimate rights of the leader and restricts the self-determination and autonomy of followers primarily through impersonal procedures and rules (Li, Chen, Zhang, & Luo, Reference Li, Chen, Zhang and Luo2019), not interpersonal interaction. For that reason, authoritarian leaders may be better able to establish high-quality LMX with subordinates than other negative leaders. Additionally, Chinese people are known to have profound respect for authority associated with hierarchical positions (Arun, Gedik, Okun, & Sen, Reference Arun, Gedik, Okun and Sen2021) and tend to maintain interpersonal harmony (Arun & Kahraman Gedik, Reference Arun and Kahraman Gedik2022). Even though they may experience negative emotions under authoritarian leadership, they may still retain their trust in the leader and attempt to foster positive relationships with the leader (Nie & Lamsa, Reference Nie and Lamsa2015). Thus, the coexistence of authoritarian leadership and high LMX is possible in the Chinese workplace. This inference is also supported by the existing literature. Gu et al. (Reference Gu, Wang, Liu, Song and He2018), have posited that subordinates with high power distance will recognize the behaviour style of authoritarian leaders and tend to establish high-quality LMX with them.

Although authoritarian leadership may affect subordinates perceived managerial intolerance of errors in light of various means by which their leaders establish eminence and thus indirectly affect improvisation within their organizations, the quality of LMX may also alter that dynamic’s influence on subordinates (Sparrowe, Soetjipto, & Kraimer, Reference Sparrowe, Soetjipto and Kraimer2006). In some Chinese companies, the traditional cultural wisdom that prioritizes interpersonal relationship over the law is still prevalent in practice, which means that the negative influence of laws heavily relied on by authoritarian leaders could be weakened by interpersonal relationship in those organizations. Added to that, Xing, Sun and Jepsen (Reference Xing, Sun and Jepsen2021) have observed that LMX exerts a long-term influence on the overall tone of information exchange between leaders and subordinates. Previous studies have additionally demonstrated that the quality of LMX affects subordinates’ expectations of their leaders’ behaviours (Furst & Cable, Reference Furst and Cable2008). Along those lines, it is not difficult to infer that a long-term, stable, caring LMX within the leader’s circle may make subordinates feel safe and comfortable in their daily work and, over time, generate the expectation that their leaders will take special care of them even if they repeat mistakes, in combination with all kinds of preferential treatment given by leaders to subordinates with high-quality LMX in their daily work (He, Morrison, & Zhang, Reference He, Morrison and Zhang2021). That is, subordinates with higher-quality LMX, given their leaders’ preferential treatment, may perceive that their leaders have a higher tolerance for errors such that they are willing and dare to improvise. Conversely, subordinates with lower-quality LMX are less likely to have such expectations of authoritarian leaders. As past research has shown, the exchange between leaders and subordinates ‘outside the circle’ is limited to the scope stipulated by their employment contracts (Graen & Uhl Bien, Reference Graen and Uhl Bien1995). As a result, because there is no social exchange between subordinates and authoritarian leaders characterized by a high degree of trust or care, subordinates dare not take matters into their own hands when the unexpected occurs.

From all of that, it follows that the level of LMX may regulate authoritarian leadership’s influence on subordinates perceived managerial intolerance of errors and thus alter that perception’s influence on subordinates’ improvisation. Our fourth hypothesis was as follows:

Hypothesis 4: LMX moderates authoritarian leadership’s indirect negative impact on subordinates’ improvisation by way of perceived managerial intolerance of errors, such that when the level of LMX is high, the indirect negative effect decreases, and vice versa.

Conditional indirect effects between task complexity-based authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation

Task complexity, the most basic factor of the task environment (Charness & Campbell, Reference Charness and Campbell1988), indicates the complexity of a task at work and the difficulty of completing it (Akgun, Keskin, Golgeci, & Ozerden, Reference Akgun, Keskin, Golgeci and Ozerden2021). Because Pundt and Venz (Reference Pundt and Venz2017) have found that the effectiveness of leadership may be affected by the task environment, we theorized that task complexity may moderate authoritarian leadership’s effect on subordinates’ perceived managerial intolerance of errors and improvisation.

Tasks of higher complexity, usually entailing a heavier load of information, greater uncertainty, and less familiarity, tend to be processed by individuals with rich, expansive knowledge about the tasks and stronger comprehensive processing abilities (Kamphuis, Gaillard, & Vogelaar, Reference Kamphuis, Gaillard and Vogelaar2011). However, in such cases, it is difficult for any individual, even leaders, to be sure that they have all the knowledge and ability to effectively meet the demands of the tasks and, for that reason, cannot plan their completion. In response, in the process of executing complex tasks, team members often need to exchange information with each other (Chen, Liu, Yuan, & Cui, Reference Chen, Liu, Yuan and Cui2019), which may generate on-the-spot ideas and behaviours. In that way, work environments involving high task complexity, in highlighting certain aspects of information that attract individuals’ attention (Salancik & Pfeffer, Reference Salancik and Pfeffer1978), can make subordinates perceive that mistakes sometimes happen and that improvisation is inevitable. Amidst such social information, the leader’s disapproval of mistakes and challenges to authority can be expected to be relatively weak, and rules against improvising can be expected to be loosened when necessary. By contrast, when task complexity is low, subordinates may develop the belief that mistakes may not be made during routine tasks due to the consistent style of authoritarian leader. Perceiving such a low tolerance for errors, they dare not improvise in the face of unplanned events. On top of that, compared with general, routine tasks, high-complexity tasks are inherently more intrinsically guided (Jung, Kang, & Choi, Reference Jung, Kang and Choi2020). Subordinates, for example, may come to believe that if they are outside a leader’s scope of management, then their leader’s orders may not need to be followed in special situations that permit subordinates’ discretion. Assuming that their authoritarian leaders will only reprimand them for significant errors at this moment, the subordinates naturally perceive less managerial intolerance of errors. At the same time, as previous studies have shown, the prosocial motivation of authoritarian leadership may intensify in situations of high task complexity and make them willing to relax the execution of standards among their subordinates in order to ensure the completion of tasks (Dreu & Carsten, Reference Dreu and Carsten2007).

Considering all of the above, we expected that level of task complexity to regulate the influence of authoritarian leadership on subordinates perceived managerial intolerance of errors and, in turn, alter the impact of such perceptions on subordinates’ improvisation. Thus, our final hypothesis was as follows:

Hypothesis 5: Task complexity moderates authoritarian leadership’s negative impact on subordinates’ improvisational behaviour by way of perceived managerial intolerance of errors, such that when task complexity is high, the indirect negative effect decreases, and vice versa.

Methods

Sample and procedures

Frontline employees at manufacturing, innovation, logistics, healthcare, and sales companies, as well as their superiors, were surveyed by questionnaire from September to December 2021. Given the actual operations within the companies, entry-level supervisors were ranked among the frontline staff, because they always face the market. The respondents were recruited in two ways. First, on-the-job masters of business administration students (i.e., entry-level positions) and their supervisors at a university in Jiangxi Province were invited to participate in the survey as paired samples, and the snowball method was used to ask them to recommend relevant persons from cooperative companies, in the form of online. Second, with the cooperation and coordination of their Human Resources Departments, two companies located in Anhui Province were invited to engage in offline research. In both ways, paired questionnaires were collected from employees below entry level and their direct supervisors. To ensure honest responses from respondents, we ensured all respondents of the confidentiality of their data and that their data would be used for scientific research purposes only, and all participants indicated their informed consent.

Time-lagged data collection was adopted to collect 1:1 leader–employee paired data in two periods separated by approximately 3 months – mid-September 2021 (T1) and mid-December 2021 (T2) – to reduce common method bias and enhance causality testing. At T1, we collected information about respondents’ perceptions of authoritarian leadership, perceived managerial intolerance of errors, LMX, task complexity, and control variables. At T2, we collected information about the subordinates’ improvisation. Data concerning improvisational behaviour were indicated by the leader in each pair according to the daily work of their subordinate, while all other variables were responded to by the subordinates.

To avoid homogeneous variance, data were collected at two points. Our sample was drawn from 21 companies in China, with team sizes limited to 5–10 members to avoid any potential biases caused by team size in examining the relationships between leaders and their subordinates among sample companies, and the total number of participants per company ranged from 12 to 25 dyads. Of 417 dyadic samples, we received 352 supervisor and 389 subordinate questionnaires, with response rates of 81.29% and 89.84%, respectively. After excluding invalid questionnaires, we finally obtained 319 supervisor–subordinate dyads. By gender, the sample had approximately the same proportion of men and women employees, with men accounting for 50.2% of respondents. The most populous age group among the employees was 26–35 years (41.6%); most employees had ≤2 years of work experience at the organization (45.0%); most had a bachelor’s degree (53.2%); and the most populous group by occupation was sales (32.5%). The tests of variance showed that the samples from different sources did not differ significantly in terms of demographic variables.

Measurements

All variables in the study were measured using established instruments with good content validity on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = ‘in very high non-conformance’ to 7 = ‘in very high conformance’.

Authoritarian leadership

We adapted the 5-item scale originally developed by Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Boer, Chou, Huang, Yoneyama, Shim and Tsai2014) to measure authoritarian leadership, a typical item being ‘He/she scolds me when I fail expected target.’ Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.899.

Perceived managerial intolerance of errors

We adapted the 3-item scale originally developed by Zhao (Reference Zhao2011) to measure perceived managerial intolerance of errors; representative items include ‘I did not feel comfortable with making errors because I knew that errors are not acceptable for my supervisor.’ The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.864.

Subordinates’ improvisation

We adapted the 7-item scale originally developed by Vera and Crossan (Reference Vera and Crossan2005) to measure subordinates’ improvisation; representative items include ‘He deal with unanticipated events on the spot.’ The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.938.

LMX

We adapted the 7-item scale applied by Hwang, Kim, Rouibah and Shin (Reference Hwang, Kim, Rouibah and Shin2021) to measure LMX; representative items include ‘My leader will use his/her power to help me solve problems in my work.’ The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.930.

Task complexity

We adapted the 5-item scale originally developed by Stock (Reference Stock2006) to measure task complexity; representative items include ‘The tasks of me mainly consist of solving complex problems.’ The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.890.

Control variables

Following past studies, the demographic variables including gender, age, occupation, tenure, and level of education of the employees, along with the type of company, were used as control variables.

Result

Confirmatory factor analysis

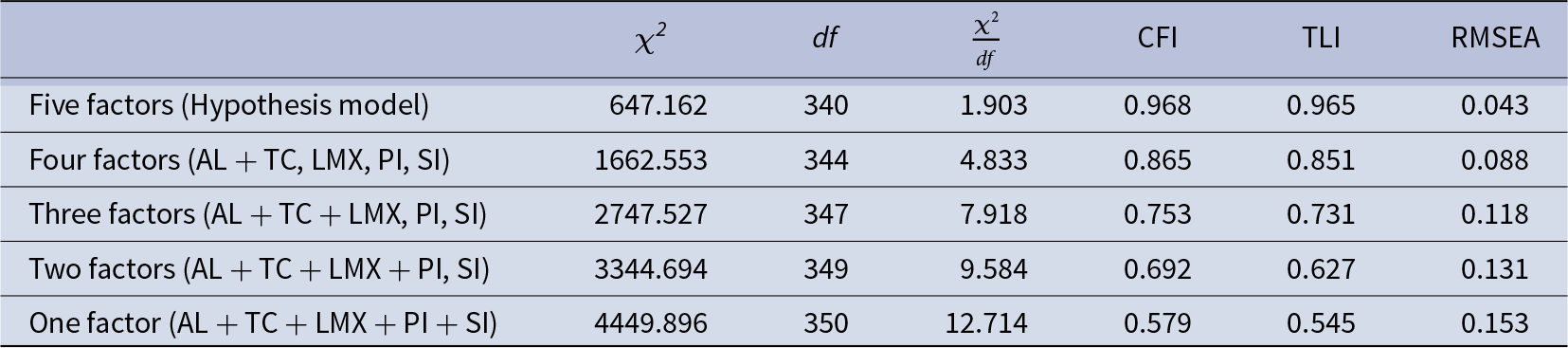

Mplus version 8.0 was used to investigate the discriminant validity of authoritarian leadership, perceived managerial intolerance of errors, LMX, task complexity, and subordinates’ improvisation. To further ensure that the model fit is robust to the specific item groupings, we ran 26 additional confirmatory factor analyses, each time randomly assigning the items for each construct to parcels. The goodness of fit was determined using the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tuck–Lewis Index (TLI) (Bentler, Reference Bentler1990; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, Reference MacCallum, Browne and Sugawara1996). The hypothesized five-factor model fit the data better than any other models with different factors (χ 2 = 647.162, df = 340, χ 2/df = 1.903, CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.043; Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Due to space limitations, only a portion of the models is presented in Table 1 in this study.

Table 1. Result of confirmatory factor analysis

AL = authoritarian leadership, TC = task complexity, LMX = leader–member exchange, PI = perceived managerial intolerance of errors, SI = subordinates’ improvisation.

Because authoritarian leadership, perceived managerial intolerance of errors, LMX, and task complexity were all subjectively rated by the employees, common method bias was a risk that we assessed using the Harman’s single-factor test. Exploratory factor analysis of the four variables showed that the first factor explained only 41.254% of the difference in variance, which was less than 51% of the baseline value (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Thus, common method bias was not a significant problem in the study.

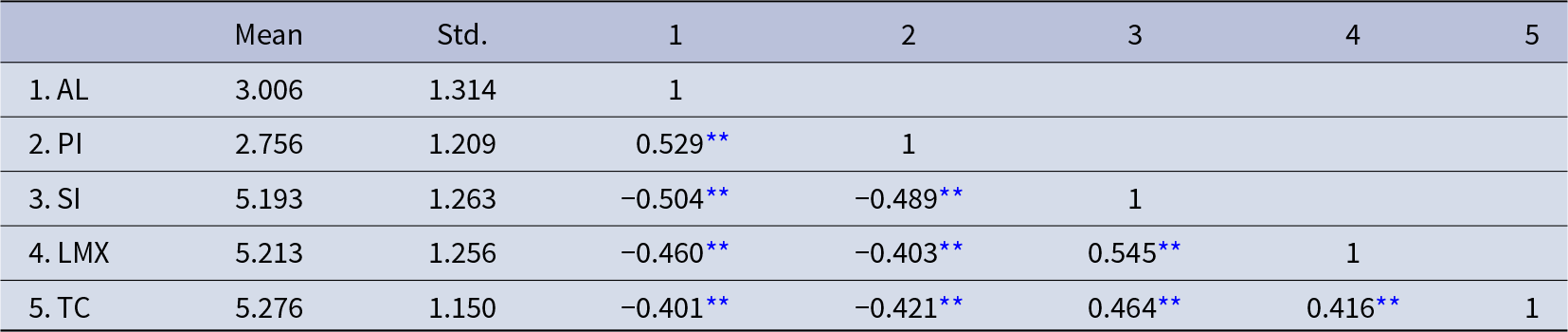

Analysis of descriptive statistics

The means and standard deviations of the five variables and their correlation coefficients appear in Table 2. As shown, the correlation coefficient between authoritarian leadership and perceived managerial intolerance of errors was .604 (p < .010), between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation was −.585 (p < .010) and between perceived managerial intolerance of errors and subordinates’ improvisation was −.680 (p < .010). Those correlations were consistent with our theoretical expectations and interpreted as preliminary support of our hypotheses.

Table 2. Descriptive statistic and correlation analysis results

n = 319;

** p < .010; AL = authoritarian leadership, TC = task complexity, LMX = leader–member exchange, PI = perceived managerial intolerance of errors, SI = subordinates’ improvisation.

Hypotheses testing

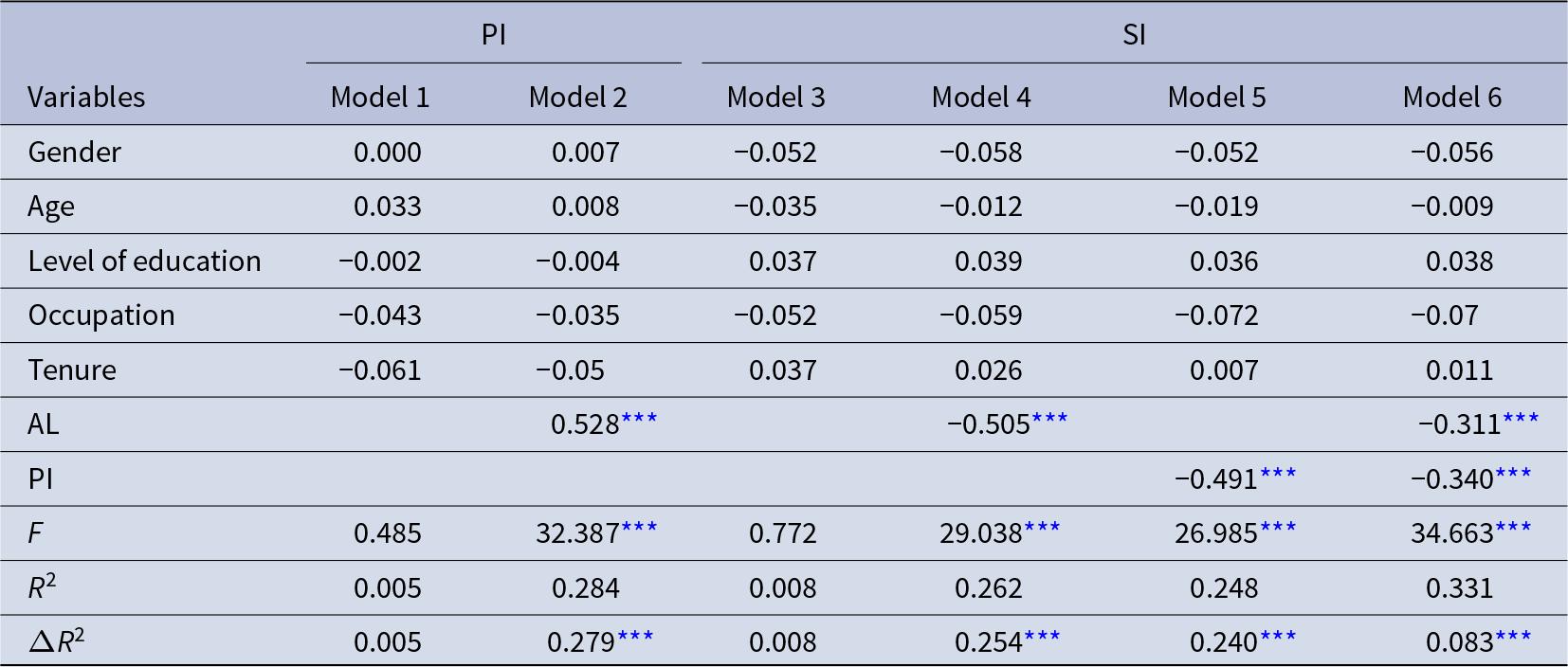

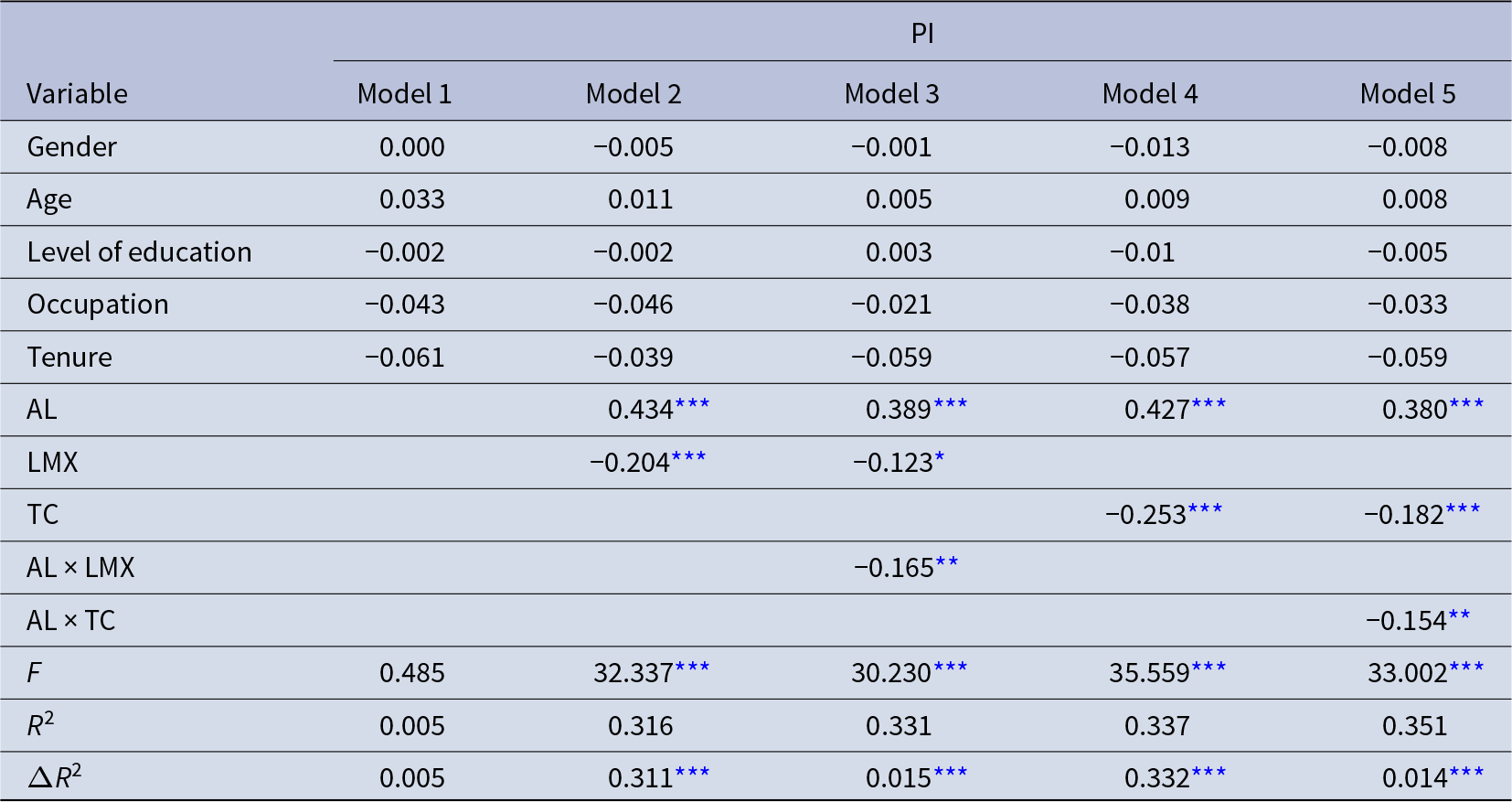

An initial linear regression analysis performed to test the direct effects of the variables revealed that, as shown in Table 3, authoritarian leadership had a significant positive correlation with perceived managerial intolerance of errors after controlling related variables (Model 2: β = .486, p < .010). There was also a significant negative correlation between perceived managerial intolerance of errors and subordinates’ improvisation (Model 5: β = − 0.513, p < .010). Thus, both Hypotheses1 and 2 were supported.

Table 3. Main effect and mediating effect test

*** p < .001; AL = authoritarian leadership, PI = perceived managerial intolerance of errors, SI = subordinates’ improvisation.

Next, Baron and Kenny’s procedure for testing mediating effects was followed to examine the mediating role of the perceived managerial intolerance of errors (Baron & Kenny, Reference Baron and Kenny1986). As presented in Table 3, when the perceived managerial intolerance of errors was added to authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation, it had a negative predictive effect on subordinates’ improvisation (β = −.513, p < .010) and weakened authoritarian leadership’s negative influence on subordinates’ improvisational behaviour (β = −.485 to −.327). Those results verify the mediating role of perceived managerial intolerance of errors between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation, which supported Hypothesis 3.

To further verify the mediating effect of perceived managerial intolerance of errors, we used the PROCESS plug-in to investigate the mediating effect’s significance by repeated sampling (i.e., 5,000 times). The results indicated authoritarian leadership’s indirect effect on subordinates’ improvisation through perceived managerial intolerance of errors (−0.158) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of −0.226 to −0.095 that excluded 0. Hypothesis 3 thus found additional support.

The moderating effects of LMX and task complexity were further investigated using SPSS and the PROCESS plug-in. In the analysis, the interaction items Authoritarian Leadership × LMX and Authoritarian Leadership × Task Complexity were standardized in advance to avoid multicollinearity. Table 4 shows that Authoritarian Leadership × LMX and Authoritarian Leadership × Task Complexity had significant effects on perceived managerial intolerance of errors (β = −.073, p < .010 and β = −.077, p < .010, respectively), which indicates that LMX and task complexity negatively moderated the relationship between authoritarian leadership and perceived managerial intolerance of errors.

Table 4. Moderating effect test

***p<.001, **p < .010,

* p < .050; AL = authoritarian leadership, TC = task complexity, LMX = leader–member exchange, PI = perceived managerial intolerance of errors, SI = subordinates’ improvisation.

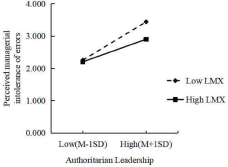

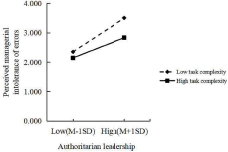

To specify the direction and magnitude of the moderating effect, we divided the levels of LMX and task complexity based on M ± 1 SD and further conducted simple slope analysis. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, the results indicated that when LMX or task complexity was low, the positive correlation between authoritarian leadership and perceived managerial intolerance of errors was strong (β = .450, p < .010 and β = .438, p < .010, respectively). However, when LMX or task complexity was high, the relationship between them was significantly weakened (β = .265, p < .010 and β = .261, p < .010, respectively).

Figure 2. Moderating effect of LMX.

Figure 3. Moderating effect of task complexity.

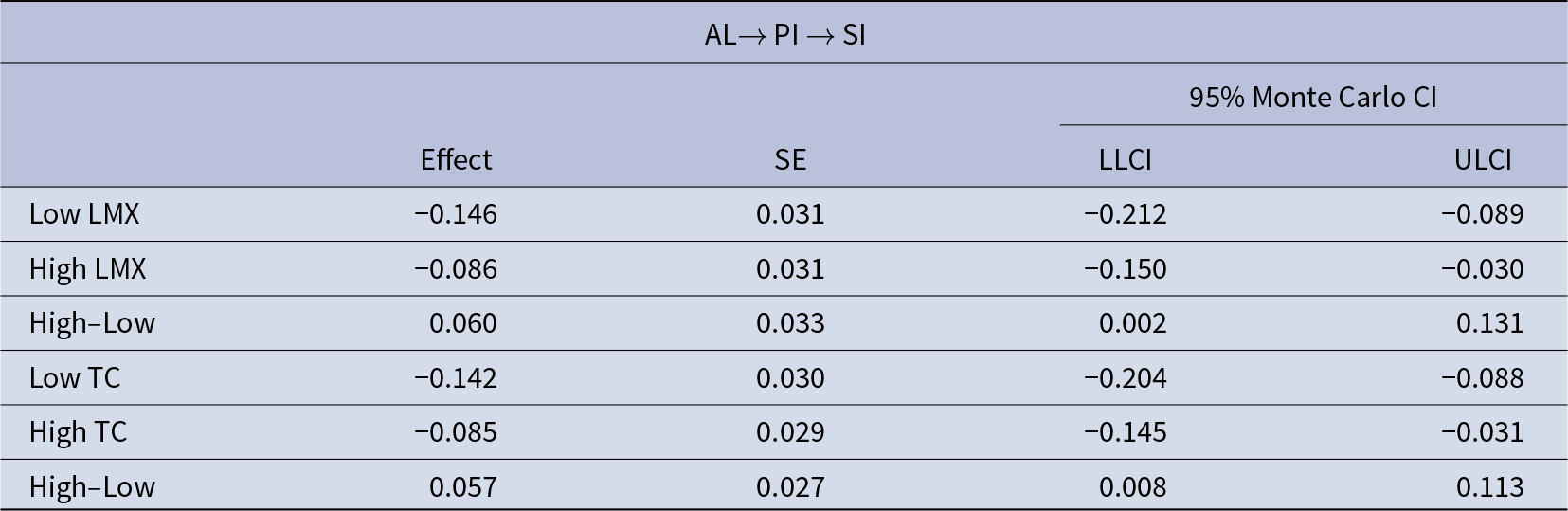

Hypothesis 4 proposed that LMX negatively moderates the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on subordinates’ improvisational behaviour via perceived managerial intolerance of errors. To estimate the CI of the indirect effect between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation in the case of high and low LMX and to determine whether the difference between the two was significant, the PROCESS plug-in was again used. As indicated in Table 5, when LMX was low, the indirect effect between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation was −0.146, 95% CI [−0.212, −0.089]. When LMX was high, it was −0.086, 95% CI [−0.150, 0.030]. The difference between the effects in high and low conditions was 0.057, 95% CI was [0.002, 0.131], those results lent support to Hypothesis 4.

Table 5. Results of moderated mediation effect analysis

AL = authoritarian leadership, TC = task complexity, LMX = leader–member exchange, PI = perceived managerial intolerance of errors, SI = subordinates’ improvisation.

Similarly, as indicated in Table 5, when LMX was low, the indirect effect between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation was −0.142, 95% CI [−0.204, −0.088]. When task complexity was high, by contrast, the indirect effect was −0.085, 95% CI [−0.145, −0.031]. The difference between the effects in high and low conditions was 0.057, 95% CI was [0.008, 0.113], and thus significant, which lent support to Hypothesis 5.

Discussion

Today’s highly competitive, rapidly changing business environment requires frontline employees to improvise, sometimes a great deal. Against that trend, authoritarian leaders, under the influence of certain traditional cultural beliefs, may stand in the way of such improvisation. Our primary objective of this study was to unveil under what conditions the negative impact of authoritarian leadership on the improvisation of subordinates would be reduced, based on the social information processing theory. Recognizing leaders as a critical source of information that influences subordinates’ perceptions, we propose authoritarian leadership as a type of workplace information source that hinders subordinates’ improvisation via increasing their negative psychological perceptions such as perceived managerial intolerance of errors. Moreover, this study investigated the boundary-condition roles of LMX and task complexity in the relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation via perceived managerial intolerance of errors. Drawing on the social information processing theory, our results revealed that the negative impacts of authoritarian leadership on subordinates’ improvisation via perceived managerial intolerance of errors are less prominent when the frontline subordinates have a high level of LMX/task complexity.

Theoretical implications

Our findings generate several theoretical contributions. First, we incorporated authoritarian leadership, a form of negative leadership, for the first time into a research framework dedicated to studying improvisation. Past studies on leadership and individual improvisation have chiefly focused on the influence of positive leadership without exploring how negative leadership reduces subordinates’ improvisation, let alone thinking about situational factors in that dynamic (Lombardi, Cunha, & Giustiniano, Reference Lombardi, Cunha and Giustiniano2021). This present study was conducted to address the lack of research on the relationship between negative leadership (authoritarian leadership) and subordinates’ improvisation, together with the impact of two inevitable conditional factors in the work environment. Our results suggest that even in authoritarian situations, subordinates are not necessarily afraid to improvise and that the perceived managerial intolerance of errors can change depending on the interpersonal relationship and task environment and, in turn, prompt different degrees of improvisation. Those findings answer prior calls for future studies to identify the psychological state linking authoritarian leadership to follower outcomes (Schaubroeck, Shen, & Chong, Reference Schaubroeck, Shen and Chong2017). Beyond that, they also indicate that leaders’ behaviour is not a constant factor influencing what subordinates perceive but how they process and interpret their behaviours in combination with interpersonal relationship and task characteristics. Therefore, our research deepens our understanding of the complex relationship between authoritarian leadership and improvisation.

Second, we pinpoint how an authoritarian leadership curtails subordinates’ improvisation by examining perceived managerial intolerance of errors as an underlying mechanism. Although this mediating effect is only partial, this research offers a novel pathway. Theoretical studies have claimed that perceived managerial intolerance of errors adversely impacts subordinates’ emotions and cognition about trial-and-error behaviours (Zhao, Reference Zhao2011), and that subordinates improvisation requires moderate degree of tolerance for error (Cunha, Cunha, & Kamoche, Reference Cunha, Cunha and Kamoche1999); however, few studies have explored perceived managerial intolerance of errors as the proximal antecedent of subordinates’ improvisation. This research, in line with social information processing theory, discussed the mechanism underlying the relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisation by introducing perceived managerial intolerance of errors to this context. The results showed that the means of establishing eminence used by authoritarian leaders in daily work tend to make subordinates perceive that their leaders have a high intolerance for mistakes, increase the perceived risk of engaging in trial-and-error behaviours and undermine their propensity and willingness to improvise.

In addition, most existing studies have focused on the influence of team characteristics and organizational characteristics on subordinates’ improvisation (Ren, Zhang, Chen, & Liu, Reference Ren, Zhang, Chen and Liu2022); however, such studies have ignored the fact that individuals may form varying opinions and perceptions of the same factor due to their individual differences in information processing. Therefore, Ciuchta, O’Toole, and Miner (Reference Ciuchta, O’Toole and Miner2021) suggested that future research should pursue a deeper exploration of the antecedents of improvisation at the individual level. In this study, perceived managerial intolerance of errors was selected as the proximal antecedent to reflect the disparities in individual information processing under the same leadership. This would help to shed light on why people exhibit varying levels of improvisations under the same leadership, thus enhancing the practical application of psychological perception and the information processing process highlighted by social information processing theory.

Third, our research, furnishes an in-depth answer to the question of why subordinates still dare to improvise under authoritarian leadership by introducing the moderating roles of LMX and task complexity. In studies on the relationship between leaders’ and subordinates’ behaviour, some scholars have positioned LMX (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Rasool, Yang and Asghar2021) and task complexity (Afsar & Umrani, Reference Afsar and Umrani2020) as conditional factors. However, in practice, LMX and task complexity often exist in the same work environment at the same time. Accordingly, we regarded them as an interpersonal relationship and aspect of task environment and achieved a breakthrough of the limitations of previous studies based on a single perspective and empirical analyses of their dual moderating effects. The results indicate that subordinates with high-quality LMX are more likely to have positive behavioural expectations of authoritarian leadership and, in turn, be more willing to improvise as appropriate. Additionally, when task complexity is high, subordinates’ sensory awareness is preoccupied with the idea that mistakes are inevitable, which overrides the social message that authoritarian leaders are not allowed to make mistakes, which reduces their perceptions of leadership’s fault-intolerance and their fear of improvising when necessary. Generally, it finds out that authoritarian leadership in establishing eminence differs from person to person owing to the different things, their influence on employee behaviour by its style characteristics, the comprehensive influence of LMX and task environment, instead of simple and cured.

Lastly, by analysing the interaction between authoritarian leadership and LMX, this study indirectly confirms the proposition in paternalistic leadership that authoritarian and benevolent leadership can coexist (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000), as authoritarian leadership that exhibits benevolent characteristics to high LMX subordinates can effectively mitigate the negative effects of authoritarian leadership and promote subordinates’ improvisation. This finding further extends the research that found the buffering effect of leader kindness on authoritarianism (Chan, Huang, Snape, & Lam, Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). Moreover, by integrating the Eastern cultural background with the theory of paternalistic leadership, this study discovers and expounds on the possibility and rationality of the coexistence of authoritarian leadership and high LMX. This indirectly expands paternalistic leadership theory by appealing that the exercise of paternalistic leadership is highly personalistic in nature, meaning that bosses do not treat all subordinates identically (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000).

Practical implications

Our findings have several practical implications for managers and organizations. First, at the level of leadership, leaders should be fully aware of the dangers of authoritarian leadership styles, which can severely discourage their subordinates’ willingness to improvise. By extension, in today’s dynamic, competitive business environment that urgently needs improvisation at time, authoritarian leaders should actively adjust their leadership behaviours, especially ones not conducive to subordinates’ improvisation (e.g., concealing key information and forcing subordinates to obey them unconditionally). Simultaneously, authoritarian leaders need to pay attention to their own attitudes and signals about their subordinates’ mistakes. Our study has demonstrated that perceived managerial intolerance of errors is an important prerequisite for subordinates to engage in improvisational behaviour. Therefore, authoritarian leaders can show an appropriate degree of tolerance when dealing with subordinates’ mistakes, or else clearly define principled and unprincipled mistakes to reduce their unnecessary fear, so that they dare to improvise when the situation requires.

Second, at the organizational level, when organizational performance largely depends on the improvisation of subordinates, corporate executives should try to avoid the introduction of authoritarian leadership in recruitment. Even if it is difficult for some authoritarian leaders to be replaced in time due to the system and pre-existing relationships, the company’s senior management can appropriately introduce them to highly complex task environments to stimulate their pro-social motivation and thereby weaken their negative impact on the improvisational behaviours of subordinates (Dreu & Carsten, Reference Dreu and Carsten2007). Apart from that, senior managers can improve the LMX quality of teams at all levels through certain human resource management measures. A case in point is that senior leaders can provide team building and culture-oriented incentives to the authoritarian leader’s team or incorporate team relationships into performance assessments.

Third, employees should take the initiative to improve their skills in getting along with authoritarian leaders and devote themselves to enhancing their relationships with superiors for the sake of improving leaders’ tolerance for errors. Especially when the situation requires improvisation, a good LMX can help employees to improve their sense of improvisation efficacy and make them bear the consequences of improvisation. In general, employees can establish high-quality LMX with authoritarian leaders by studying the interactions of subordinates inside the leader’s circle, supporting leaders’ decisions, taking the initiative to help leaders to solve problems and reasonably appreciating and praising leaders, among other actions, for the purpose of fostering support and trust as well as improving the flexibility and creativity required for improvisation.

Last, because improvisation may not yield good results and its utility is situational and categorical (Xiong, Reference Xiong2022), authoritarian leaders should be on guard against their unwarranted tolerance of the improvisation of subordinates with high LMX. After all, interpersonal relationship, as a form of favouritism, may encourage mistakes to happen as a result of improvisation, and it is easy to induce an unfair perception of outsiders that leads to unexpected consequences. At the same time, for a team in a stable task environment with a highly efficient orientation, the leader should also engage in appropriate authoritarian behaviour in order to limit the inappropriate improvisation of employees and guide them to follow the rules.

Limitations and prospects for future research

Our study involved a few limitations. First, it examined only the influence of the authoritarian style of immediate supervisors on subordinates’ improvisational behaviour. Even so, it would also be worth exploring whether the behaviour style of higher leaders exerts cross-layer interference on that relationship. Second, regarding interpersonal relationships and task environment, it investigated only the impact of LMX and task complexity, whereas relational capital (Bian, Reference Bian, Lin,K. Cook and Burt2001) and task interdependence (Langfred, Reference Langfred2007) could be subjects in similar research that investigates, for example, whether close relationships with higher-level leaders (i.e., relational capital) diminish the negative effects of authoritarian leadership.

Second, another question is when tasks require close cooperation between team members (i.e., task interdependence), does authoritarian leadership have a ripple effect on subordinates’ improvisation? Future research could also depart from the framework of relationship and task environment and focus on the weakening effect of mental factors such as mindfulness on subordinates’ negative perceptions and whether they buffer the mediating effect of perceived managerial intolerance of errors on authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ improvisational behaviour.

Fourth, although this paper has highlighted the difference between improvisation and creativity, they do have some overlap in their connotations. Future research could analyse this in depth in order to more clearly examine the different influences of authoritarian leadership on both. Fifth, although the possibility of homologous bias was greatly reduced by using multi-source data and time-lagged data collection, it remains difficult to completely avoid such bias. In the future, multiple validation can be carried out with larger samples and tests for common method bias.

Sixth, this paper focused exclusively on first-line employees in companies in China, where Confucianism and cultural values of familism prevails. In fact, Confucianism and cultural values of familism also have strong traces in other East Asian cultures, such as Japan and South Korea (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Boer, Chou, Huang, Yoneyama, Shim and Tsai2014). So, the shared Confucian philosophical roots make it possible to apply the findings of this study to many East Asian societies. However, it should be acknowledged that there are significant differences between Eastern and Western cultures. Therefore, future research could explore whether the conclusions drawn from this study can be applied to senior management or first-line employees in Western countries, such as the United States.

Last, our empirical results show that the mediating role of perceived managerial intolerance of errors is partial, there may be other mediating mechanisms between authoritarian and subordinates’ improvisation. Future research could also depart from the social information processing theory and focus on other mechanisms, such as whether the power and control of authoritarian leaders reduces the access to resources (reflecting the extent to which individuals are free to access and filter the resources they need to perform their tasks) of subordinates (Spreitzer, Reference Spreitzer1996), and thus deters improvisational behaviour.

Conclusion

Using social information processing theory and multi-period, multi-source data from a questionnaire survey, we found that authoritarian leaders curb improvisation behaviours by way of subordinates’ perception that errors are not tolerated. However, the indirect effects of authoritarian leadership are contingent on the regulation of LMX and task complexity, such that when LMX or task complexity is higher, the inhibition to improvise under authoritarian leadership diminishes accordingly. In other words, the same authoritarian leadership may have different influences on the improvisation of different subordinates in different task environments. These findings can provide companies (especially those with Eastern culture) with a better roadmap to manage their frontline employees’ improvisation in an efficient and scientific manner.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ri-Guang GAO for his assistance in data acquisition. They also thank Jian-Feng Yang, Cai-Yun Sun, Hao-Tian Jiang, and Yuan-Da Luo for their feedback and advice during the preparation of this essay. Whether they agreed or disagreed with the authors’ opinions, their comments helped to articulate those opinions more clearly.

Financial Support

This study was supported by ‘National Natural Science Foundation of China’ (72172054) and ‘Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of education of China’ (21YJC630143).

Xiong Li is an associate professor in School of Economics and Management, Nanchang Institute of Science and Technology. He received his PhD in Management from Jiangxi University of Finance & Economics. His current research interest is entrepreneurship, organizational ambidexterity, and HRM.

Nian Peng-Xiang is a PhD student in School of Business Administration at South China University of Technology.

Liu Bo is a lecturer at Jiangxi Agricultural University and she obtained her PhD in Management from Jiangxi University of Finance & Economics. She is passionate about research on leadership.