Sugarcane agriculture has dominated the coastal area of the north-eastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco for almost half a millennium. The workers in those fields descend from many generations of cane workers, reaching back to those who toiled under a three-and-a-half-centuries’-long slave regime. Twentieth-century workers inherited not just the work, but also the culture created by and around the agro-industry, including patterns in the distribution and exercise of power based on land ownership. We have seen traces of this inheritance in the form of violent and highly racialized labour relations, persistent exploitation, and disdainful attitudes toward rural labour. These features prevailed even after 1963, when the Rural Worker Statute (Estatuto do Trabalhador Rural – ETR) was passed under the left-nationalist President João Goulart in a context of heightened social mobilizations and progressive reforms. The bill extended to rural workers many rights already enjoyed by urban or industrial workers. The ETR rapidly extended labour courts (Juntas de Conciliação e Julgamento, JCJs) to rural areas to hear the complaints of rural workers and employers. Though it did not bring liberation, the law triggered the production of an invaluable cache of sources with which it is possible to explore the history of rural Pernambuco.

This paper answers a key question: To which degree did Pernambuco’s rural labour courts reflect patterns of class-based exploitation, even though they were institutions created through an apparently progressive extension of labour rights? Cases heard in the courts between 1965 and 1982 comprise the empirical foundation of our analysis.Footnote 1 Non-rural workers had had access to the labour judiciary since the 1930s, when Getúlio Vargas came to power and initiated a long period of state interventionist politics that involved both a series of worker-friendly reforms and a high degree of state control over unions and the labour movement. The labour judiciary was institutionalized more reliably during the corporatist and dictatorial Estado Novo (1937–1945) with the Consolidation of Labour Laws (Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho – CLT) in 1943.Footnote 2 The mere fact of the twenty-year lag between the major legal interventions of the CLT and the ETR, a period when rural workers awaited their rights, indicates the consistency of state authorities’ collective posture toward rural, as opposed to urban work: They not only recognized a difference between these arenas of labour, but also relegated rural labour to a position of inferiority relative to its urban-industrial counterpart.

We argue that these attitudes flowed from social structures with long histories, including slavery. And we suggest that this perspective had concrete effects. As this article will show, there clearly was a differential treatment accorded to rural and non-rural workers in the outcomes of the cases.Footnote 3 Even after gaining admission to labour courts, Pernambuco’s cane workers suffered discrimination in their belatedly granted rights.Footnote 4 We found considerable differences between rural and non-rural workers in the mode of calculating compensations and the amounts awarded for revoked contracts or complaints of unpaid benefits.Footnote 5 To explain these differences, we will further analyse the social and educational background of the judges rendering the court decisions. As will become clear, they were so closely linked to both the landed class and the state elites that it seems plausible to speak of a coherent class perspective, informed by the cultural imaginary of Brazil, which was especially pronounced during the military regime (1964–1985).

After addressing this material from Pernambuco’s rural labour courts, we put three core themes from our interpretations into dialogue with rural labour scholarship from various places around the globe: First, we point to the blurred lines between free and unfree labour, a phenomenon registered prominently in more recent Brazilian historiography and which is, furthermore, at the heart of current debates in labour history worldwide.Footnote 6 Second, we see the labour courts as crucial sites for observing the actions of the state and the structural inequalities it reinforced. Third, we draw on scholarship that engages cases like Brazil, where notions of modernity and archaism conflicted and overlapped. These themes are in conversation with work about India, Africa, the greater Caribbean Basin, and the United States.

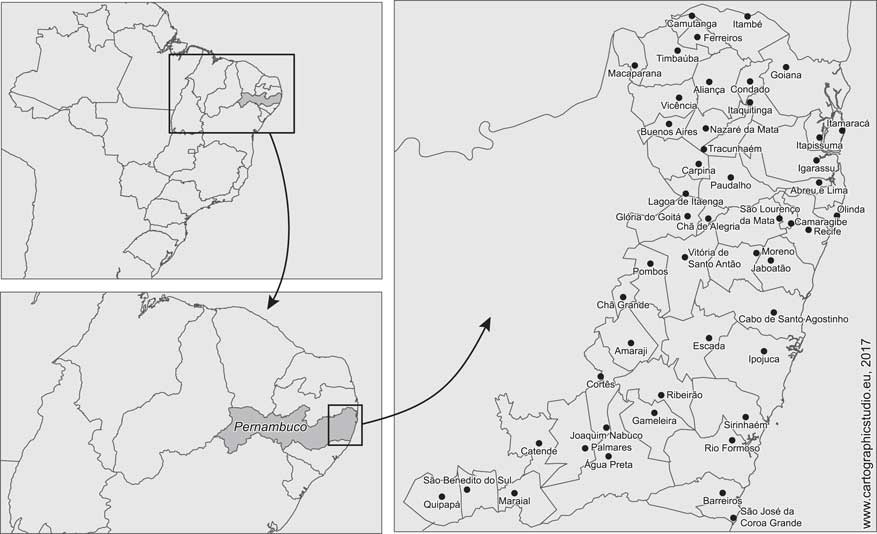

Figure 1 Pernambuco’s sugar cane zone, 1960s-1980s.

RURAL WORKERS’ STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE: THE EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Background of the Labour Courts

It is possible to draw a detailed picture of rural workers’ interactions with employers and judges by analysing a sampling of cases from two courts (JCJ’s) situated in Pernambuco’s cane zone: Catende and Nazaré da Mata, which lie, respectively, in the southern and northern sub-regions and which shared similarities and had significant differences (see Figure 1).Footnote 7 We examined four sample years, distributed in roughly six-year intervals across a generation after passage of the ETR: 1965, 1971, 1977, and 1982.Footnote 8 By gathering a large number of rural cases for each year and comparing them with around twenty non-rural cases, we were able to reveal the difference in treatment experienced by rural and non-rural workers, as well as changes over time (see Table 1).

Table 1 Comparing Rural and Urban Workers’ Experiences in the Labour Courts (Catende and Nazaré da Mata). 1,221 cases total.

* Money amounts given in this table are to be taken with caution because of several currency changes during the period as well as the impact of inflation: In 1967 the cruzeiro (Cr$) was replaced with the cruzeiro novo, only to revert back the cruzeiro (Cr$) in 1970, starting, however, with a higher valuation against other world currencies. By 1977 and 1982 inflation had returned the currency to similar levels as in 1965. The money amounts thus serve mainly as a measure for the differences between rural and non-rural workers.

† Regional minimum salary (salário mínimo regional).

The basic administrative level in Brazil is the district (município).Footnote 9 The jurisdiction of a single court may encompass several districts, as with Nazaré da Mata court, hearing cases from a large proportion of the northern sugarcane region. Catende’s court, on the other hand, covered only a few districts.Footnote 10 Government records allow for a precise assessment of Catende and Nazaré’s land ownership patterns in 1985.Footnote 11 The Catende Mill alone held 78.60 per cent of the land in that district. Counting its subsidiary properties, the mill owned ninety-six per cent of the land! Meanwhile, farmers with up to ten hectares represented forty-one percent of the total number of parcels, but held only 0.46 per cent of the total area. Middle-sized properties (ten to 100 hectares) held 3.67 per cent. The same pattern prevailed in many of the other districts of the southern cane zone; for instance, neighbouring Palmares had twenty-six small farmers, accounting for 0.3 per cent of land ownership, while medium farms held 3.97 per cent and the thirty-seven large estates enjoyed a near-monopoly of 95.73 per cent of the land. The ownership patterns of the northern cane zone are similar, but slightly less acute. In Nazaré da Mata, 4.23 per cent of the land was in the hands of small farmers, who owned 66.31 per cent of the properties. Forty-one large estates (14.38 per cent of all properties) owned 87.02 per cent of the land. Neighbouring Timbaúba and Vicência, two large districts in the northern area, have similar patterns, with slightly less property concentrated in large estates, although they still control around seventy-five per cent of the land.

Therefore, Catende and Nazaré da Mata differ slightly from one another, but match the prevailing norms for their respective sub-regions. Data for the whole cane zone reveals that in more than twenty of forty-six districts, properties larger than 100 hectares occupied eighty per cent or more of the land. As a result, for a majority of the population, there were very few local alternatives to wage labour on big estates.

We chose our two sample courts and four sample years with the intention of gauging relatively distinct conditions. In a southern cane area like Catende, the establishment and growth of the large productive mills (usinas) since the 1940s had been replacing the traditional plantations (engenhos). In the northern area, however, even in the 1960s a district like Nazaré da Mata had comparatively more small farms and a large proportion of workers still had access to personal garden plots. The domination and expansion of the mills was strengthened in the 1970s by several federal financing programmes, the most famous of which was the National Alcohol Programme adopted in 1975, which incentivized and subsidized the production of fuel ethanol. Finally, the redemocratization process from the beginning of the 1980s introduced another variable; the rural workers’ unions of the cane zone organized major wage campaigns and region-wide strikes beginning in 1979 and these started to bear fruits.

In spite of all of these differences and the geographic and temporal variation, we found a stable pattern: lower wages and levels of compensation for rural workers than non-rural and less value accorded to rural workers’ time of service. Furthermore, rural cases seem to have been treated with a cavalier attitude, with judges making less effort to carefully measure the plaintiffs’ rights. Most plaintiffs were illiterate, of Afro-Brazilian descent, and they frequently went to court unassisted by their trade union.

Figure 2 Cane worker, Pernambuco, 1940s. Acervo Fundação Joaquim Nabuco – Ministério da Educação. Used by permission.

The court case files comprise the only consistent and comparatively abundant source material that offers direct insight into these rural workers’ lives during the period in question, especially the 1960s and 1970s. As we have noted in previous publications, rural workers have left behind very few written sources that attest to their ideas, feelings, and experiences. They have existed in a predominantly oral culture, and the elite sources that we do have generally treat them as a bloc, or a mass; this includes such traditional historical sources as newspapers.Footnote 12 These labour court files, by contrast, track individual workers’ paths as the court treated complaints, sometimes with transcribed individual testimony and personal details. For the particular sample years chosen for the two courts, we have considered all cases for which the files met certain requirements (such as adequate physical status of file, basic information on the workers and their reasons for being involved in a case, etc.).

The gross number of cases heard in a given court varied from year to year.Footnote 13 But from case to case, we also found significant inconsistencies in the amount of information gathered. For instance, not every plaintiff or plaintiff’s lawyer (the latter, when present, usually hired by the rural workers’ union) stated the wages that the plaintiff earned. And plaintiffs often failed to mention how many years they had worked for an employer. Others, though, reported time of service with startling precision, as when a worker in Catende reported in 1965 that he had worked for three years, seven months, and fifteen days.Footnote 14 Finally, many of the paper files themselves have deteriorated over time, leaving us with incomplete or illegible records. Many of the cases did reach an end point, with a document outlining the terms of the conciliation. Many other cases were only archived (a phenomenon that we will further discuss below), and a smaller proportion were arbitrated directly by the judges. Despite its initial introduction through the efforts of a vigorous workers’ movement, labour legislation made its most important advances in Brazil under the regime of Getúlio Vargas, particularly during the corporatist dictatorship of the Estado Novo (1937–1945) and thus retained a strong paternalistic streak at least until the adoption of a new federal Constitution in 1988.

A trained member of the judiciary acted as the presiding judge of each court. Called a president, he generally came from the educated, white upper middle class, often directly linked by patronage or family ties to the landed class, and he almost invariably had attended the Recife Law School many of whose graduates assumed high state functions (both in Pernambuco and the federal state) as well as positions in the labour courts.Footnote 15 Indeed, particular families maintained traditions of staffing the judiciary. Judges and the rural employers who were taken to the labour courts thus generally came from the same class background. Two additional lay judges assisting the presidentFootnote 16 were chosen by the respective professional organizations of workers and employers, thus reinforcing the central purpose of the courts: to conciliate between workers and employers as proclaimed since the CLT. The position of lay judge was often a sinecure for trustworthy union officials who had been fully integrated in the corporatist structures built under state auspices since the 1930s. Meanwhile, those chosen by employers shared the same class background with the academically trained presiding judges.

Judges and their class peers (even people who ostensibly supported workers) operated according to an epistemological framework that constructed the rural world as ontologically linked to backwardness and inferiority. In this stage-based historical imaginary, the predominant mode of production in rural areas – especially in the supposedly “feudal” cane plantation system – represented an era to be superseded. According to such views, the workers during the anachronistic slave-based labour regime until the end of the nineteenth century, as well as their descendants until the 1950s and again after the coup in 1964, lacked basic freedoms, especially the freedom of information, movement, and association, and even simply the freedom to assemble as a workforce on a plantation to develop and manifest a socially constructive class consciousness. These ideas informed and shaped the mentality of authorities in general and particularly the state apparatus, including the judges.

The roots of this framework run deep, into a centuries-old power structure that encompassed all dimensions of life. The consolidation of power by certain families had a social and class logic, and was deeply racialized. The more “progressive” elites of most of Brazil’s federal states in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries turned to an adapted variant of positivism, which not only pledged allegiance to “progress”, “science”, and “law”, but also supported a form of eugenic politics by “whitening” the country through European immigration, hoping that the past of a slave-based economy and, indeed, the whole Afro-Brazilian component of Brazilian society would vanish.Footnote 17 Offspring from the dominant class manned state posts throughout the post-independence eras of the Brazilian Empire (1822–1889) and the First Republic (1889–1930). But the main basis for the concentration of power in the cane region was, and remains, land ownership. As borne out in the statistics cited above, the overall pattern was of monopolistic domination. Military and police strength had enforced these concentrated landholdings since the period of colonization. Neither the land’s original inhabitants hundreds of years ago, nor rural workers who hoped to become real farmers, had a chance of breaking the hold of the major landowners – not even in those historical moments since the 1930s when urban, industrial workers in other parts of Brazil were able to gain considerable concessions.

Findings from the Court Records

In August 1963, negotiations between employers and workers of Pernambuco’s cane region produced a landmark document meant to standardize compensation, but effective wages could vary quite widely. The Ministry of Labour had jurisdiction over the document’s enforcement but conducted little oversight. The parties renewed the agreement until 1965, when, in the wake of the right-wing military coup of 1964, it was effectively discarded until 1979; then, a strike by cane workers forced employers to participate in negotiating new guidelines for fieldwork. With or without such agreements, the overall picture revealed by the sample cases from Nazaré da Mata and Catende in 1965, 1971, 1977, and 1982 shows that rural workers generally earned lower wages, and worked longer periods for their employers than non-rural workers, as well as receiving lower settlements when going to court (see Table 1).Footnote 18 The near-invariability of the rural workers’ inferior compensation and treatment supports our overarching argument that this group of workers faced pervasive discrimination.

The cases from Catende in 1965 document employers – and especially the district’s dominant employer, the Catende Mill – reacting to the passage of the ETR.Footnote 19 The mill was involved in the vast majority of the cases from this year as it dismissed hundreds of workers in order to avoid compliance with the ETR’s prescriptions. Without a formal employment relationship, the mill would not have to provide workers with the stipulated benefits such as distributing the end-of-year bonus, pay for holidays, etc. The mill also likely carried out a political cleansing following the coup, dispensing with workers who had joined Peasant Leagues or were seen as militant trade unionists. The uniformity of Catende Mill-related cases from this year differs from other years and other courts, in which the cases were of greater variety. In many of the 1965 Catende Mill firings, the workers received no compensation at all from the court.

Figure 3 Group of workers cultivating cane field, Pernambuco, 1940s. Acervo Fundação Joaquim Nabuco – Ministério da Educação. Used by permission.

We selected ninety-nine cases of the Catende JCJ from 1965, involving 107 individuals; all were dismissals and we have no data for wage levels. The rural workers received an average compensation of Cr$40,778.03. If we divide the awards rural workers received by the total years they worked, we find that they were given an average of Cr$5,880.30 per year of work, although amounts per year of service varied widely among rural workers. In fact, judges appear not to have weighted length of service, with awards bearing little relation to experience. A series of cases from November bears this out, as fourteen workers fired around the same time received the same award – Cr$40,000 – despite having experience ranging from three years to twenty years.Footnote 20 The apparent randomness of some of these compensation levels leads us to believe that many of the dynamics at play in the courtroom did not leave any traces in the case records (such as varying degrees of commitment by the lay judge for the workers’ side, the intervention of a local priest, etc.). It is possible, too, that the lawyer of the mill, particularly in Catende, successfully argued that the certain cases’ claims should be reduced or dismissed entirely.

We should note that the primary importance of comparing wage and compensation quantities lies in what they reveal relationally, between different groups of workers for instance. The currency suffered from high inflation during the period and the government reacted with devaluations and by introducing new currencies. Brazil replaced the cruzeiro with the cruzeiro novo in 1967, but when the new currency fell prey to inflation, it shifted the name back to the cruzeiro in 1970. This cruzeiro began with a higher valuation against other world currencies, meaning that wage levels and prices were calculated in much smaller amounts. This explains why judgement and wage amounts appear markedly different between 1965 and 1971; one can also see that, by 1977 and 1982, inflation had returned the currency to similar levels as in 1965. To further contextualize the values from this paper, the average compensation cited above for rural workers in Catende 1965 came to $2,303.96 in US dollars from the time, or US$332.24 per year of work.Footnote 21 In terms of buying power, a kilogramme of dried meat (charque) cost between Cr$1,500 and 1,800 in March 1965. So the indemnification of a year’s rural labour would buy a bit more than three kilos of meat.Footnote 22

Non-rural workers going to the Catende JCJ were awarded an average compensation of Cr$291,391.05 (US$16,463.59). Because they tended to work fewer years for an employer than rural workers, their per-year award was much higher, averaging Cr$48,666.14 (US$2,749.64). Rural workers, then, earned about an eighth of the per-year rate of compensation of their non-rural peers. Even low-level non-rural workers, like unskilled casual workers (serventes) received larger settlements than rural workers. An unskilled worker with four and a half years of experience, for instance, received Cr$372,804, while a rural worker who had served the mill for ten years got only Cr$30,000.Footnote 23 Administrators, not surprisingly, received much larger compensations. Their higher prestige roles, placing them closer in the class strata to their employers, meant that the packages from the two cases we found in this year were much larger: Cr$180,000 and Cr$177,428 per year, respectively.Footnote 24

For Nazaré da Mata in 1965 we gathered 453 rural cases with enough data to use and sixty non-rural cases. Among the rural cases, 265 ended in conciliations, eighty-five cases were archived because the plaintiff failed to appear, and for eighteen cases the plaintiff withdrew his or her complaint. On the non-rural side, we only have documented resolutions for twenty-nine of the cases. Of those, nineteen ended in conciliations, eight were archived, and the plaintiff withdrew from two cases. The average judgement on non-rural workers for 1965 was Cr$67,687 (US$3,824.32), while the average rural judgement was Cr$57,408 (US$3,243.55). The average non-rural wage for 1965 was Cr$1,290.97 per month (US$72.94), with an average of 2.8 years of service. The average rural wage was Cr$992.58 (US$56.08) and rural workers had worked an average of 5.2 years for their employers.

We have 110 cases from the Catende court for 1971, and for a plurality of these the Catende Mill was listed as the defendant (thirty-six of the ninety-nine rural cases and seven of the ten non-rural cases). The other defendants in the non-rural cases were the Roçadinho Mill, twice, and a tile factory. The non-rural workers were three unskilled casual workers, a carpenter, a mason, a brakeman (presumably for the mill’s railroad), a locksmith’s assistant, a forest guard, a tile maker, and a foreman. All ninety-nine rural plaintiffs were given the generic “rural worker” label. Among these, fifty-six were archived and thirty-three were conciliated. Twelve were either judged in favour or against the plaintiff. These numbers exceed ninety-nine because some of the cases included more than one plaintiff, while the different workers experienced different resolutions, a typical pattern in these courts. In all, seventeen of the rural cases were collective complaints. Only eleven of the rural plaintiffs could sign their names; the others marked the court documents with a thumbprint. For only two of the non-rural cases a determination of the signature mode could be made: one signed, the other did not. For the region as a whole, these were fairly typical ratios for literacy (or at least the capacity to write one’s name).

For only twenty-five of the ninety-nine Catende 1971 rural cases do we have a clear monetary award recorded for the plaintiffs. For five of those, we also have the claim made by the plaintiff and in each of these cases the award was far lower than the claim. On average, rural plaintiffs were only awarded about eight per cent of their initial claims. In one example, the worker demanded Cr$3,641 (US$191.52) and ended up receiving only Cr$97 (US$5.10).Footnote 25 Interestingly, Catende in 1971 represents an exception to the general structural gap in wages between the different groups of workers, with both rural and non-rural workers earning around Cr$4.50 per day (US$0.24). In the same vein, the average time of service for the rural and non-rural workers was quite similar: eighteen years for the former group and 16.5 for the latter.

In Nazaré da Mata in 1971, however, differences between rural and non-rural workers were marked in all matters: We have twenty-one non-rural cases, of which nineteen ended in conciliations (and one withdrawal and a judgement). Among the 100 rural cases for 1971, seventy-five reached conciliations and sixteen were archived when the plaintiff failed to appear (and two withdrawals and five judgements). As for the average compensation awards, the rural workers, were granted only fifty-eight percent of the money their non-rural peers received. The average time of service for the rural awardees in 1971 was 7.8 years, while the average time of service for non-rural workers was five years. The average daily rural wage was Cr$3.93, while the average non-rural wage was Cr$6.87.

While rural employers fired workers en masse following the passage of the ETR, they later devised other ways to avoid legal obligations to their employees. Some of these 1971 cases offer insight into the range of strategies employers used to manipulate work conditions and push workers off their contracted rolls: For instance, workers often complained about field foremen demanding tasks too large to complete, which would cause the worker to lose Sunday’s paid rest.Footnote 26 The inverse of this strategy consisted of refusing to assign workers any task at all, forcing them to seek work elsewhere.Footnote 27 Similarly, the mill might assign only five days of work instead of six, or demand six when the worker wished to work five.Footnote 28 More commonly, mills would deliberately pay less than the minimum wage, forcing workers to appeal to the courts for assistance. In one instance in 1971, thirty-one plaintiffs filed one case together in relation to this complaint.Footnote 29 Finally, some cases from 1977 also mention a list of casual off-the-books workers (a “folha extra”) deprived of the benefits won through collective bargaining results (and allegedly not entitled to make any claims before the labour courts).

Figure 4 Group of workers harvesting cane, Pernambuco, 1940s. Acervo Fundação Joaquim Nabuco – Ministério da Educação. Used by permission.

Among employers’ strategies in their repertoire for evading labour law, especially in the southern cane region, mills would find renters who had contracts to manage some mill land. These arrangements aimed to obfuscate the question of who bore responsibility for the long-term rights of the wage earners. The mill would argue that it had no responsibility since the renter was the actual employer. After only a few years, though, the renter would end the rental arrangement and abandon all obligations vis-à-vis the workers. In addition, mills often expected renters to eliminate traditional claims such as access to a plot for planting food crops and “clear” the land of workers. The period we are analysing is considered the height of this process of expulsion from gardens.Footnote 30 Technological changes, such as increasing mechanization and the use of agricultural chemicals, also arrived during this period, progressively diminishing the demand for rural workers. At the same time, the area under cultivation expanded since state subsidies for land planted with sugarcane were available and planters filled all available space with cane. Improved road conditions allowed workers to shift more rapidly from countryside to city according to seasonal labour demands, and both processes together meant an increasing casualization and urbanization of rural workers.Footnote 31

Our files for Catende in 1977 include seventy-seven rural workers’ cases and twenty-seven non-rural workers. Very few of the latter have complete data, unfortunately. Compensation judgments range widely, the lowest being merely eight per cent of the highest, as do wage levels, from Cr$250 (US$16.95) to Cr$500 (US$33.90) per week to only Cr$16 per day (US$1.08).Footnote 32 Variations among non-rural workers were even more marked.Footnote 33

A large number of women among the rural workers in this year’s cases (forty-one out of ninety-one) may have been the result of a Usina Catende policy of firing female employees. The mill would target women as a means of pressuring families to leave the property and give up their garden plots.Footnote 34 Some were dismissed for pregnancy and child birth. Severina Alexandre da Silva explains that she “gave birth and was fired”, even though she had been working for the mill for five years.Footnote 35 Other workers claimed that they were threatened, probably by employers seeking to expel them from plantation property. José Alves da Silva, for instance, who had worked more than twenty years for his employer, stated that the Esporão-Canhotinho Plantation’s owner had threatened and tried to push Silva to accompany him to the police station (his case was archived as he did not show up at court).Footnote 36

Many cases deal with a specific request: workers sought categorization as industrial rather than rural workers. Lawyers brought the demand so often for workers that they phrased it in consistent language in the case files and brought mimeographed copies of the section of the CLT that pertains to the sugar industry. They also cited a decision by the Supreme Labour Court (Tribunal Superior de Trabalho, TST), holding that all those employed by a firm with an industrial activity should be considered as industrial workers, whether they worked in a mill or not.Footnote 37 A change of category could win a worker a higher minimum wage. The argument shows the ingenuity of workers and their union lawyers in defending their interests and countering employer abuse and intransigence.

Such attempts to change legal status are hardly surprising, considering the court decisions on compensation: In Nazaré da Mata in 1977, the average compensation for rural plaintiffs was Cr$4,386.15 with the average time of service being 9.5 years. The non-rural workers, on the other hand, received awards averaging nearly twice as much while generally working fewer years for their employers (6.4 on average). However, non-rural cases reached conciliation much more regularly (eleven of the twenty), while eight were judged and one ended in the plaintiff’s withdrawal.

In 1982, of Nazaré da Mata’s twenty non-rural cases, fourteen ended in conciliations. Two others ended in judgements by the court judges, two were archived, one plaintiff withdrew, and we do not know the outcome of the final case. We have forty-one rural cases, twenty-five of which reached conciliations. Nine others reached judgements and we lack data for the other seven. There was a difference of thirty-two per cent in the average compensation levels between rural and non-rural workers (roughly Cr$63,000 against Cr$92,000, or US$346.50 and US$506).Footnote 38 On average, non-rural workers made Cr$620.56 per day, while rural workers earned Cr$453.09 per day (US$3.42 and US$2.49, respectively). This represents a similar gap between non-rural and rural workers to that seen with the compensations, with the latter earning only seventy-three per cent of their non-rural counterparts’ wages. The rural plaintiffs had given an average of 7.24 years of service and the non-rural workers 4.16 years.

A Nazaré da Mata case from early 1982 offers some additional insights into the conditions and culture workers faced in the courts: Antonio José da Silva brought a complaint against the plantation Gameleirinha in January, claiming he was fired without prior warning and asking for support because he had been absent from work for a month through illness. In testimony before the court, Silva said that his pay records did not accurately reflect all of the work he had done, but he refrained from pursuing that complaint because he feared physical reprisal from the plantation renter, Marcelo Ibernon de Albuquerque Cavalcanti.Footnote 39 In fact, Silva testified, Cavalcanti had explicitly threatened to do so. In this case and others, we glimpse the pervasive climate of violence surrounding rural workers every day. That violence buttressed and policed very pronounced class divisions that separated workers from their social superiors. And the latter group did not just include the plantation and mill owners, but the judges and lawyers in the court as well.

The perpetually lurking violence workers faced, we contend, was one of the main reasons for the high rate of attrition observed for all years. A large proportion of cases were listed as archived, or cancelled, because of the plaintiffs’ failure to appear for hearings after lodging an initial complaint. This could make up more than half of the cases, as in Catende in 1971, when fifty-six out of ninety-nine cases were archived. In addition to the climate of violence, the onerous distances workers had to travel to the court and attend hearings also impeded cases from reaching a conclusion. Workers would lose a day of work and their paid weekly rest.

Finally, numerous cases made clear that workers sensed that the courts were biased or constituted a space that actually made them more vulnerable. Sometimes, this becomes visible when workers asked to be heard by another court, as José Manuel de Lima did in 1977, requesting that his complaint be forwarded to the Regional Labour Representative, because “it is very hard to win a labour complaint” in the Catende court.Footnote 40 In more general terms, the mere numbers indicate the degree to which courts were a space of risky exposure for workers. We analysed 104 cases of rural workers in Catende in 1982, and half of the workers seeking compensation failed to receive it. We see familiar reasons for the failures, such as one worker testifying that he had received a death threat,Footnote 41 while Josefa Maria da Conceição testified that she had been fired after her husband filed a complaint against their employer.Footnote 42

At the same time, Catende in 1982 stands out from other years as some of the usual patterns between the two major groups of workers are reversed: Rural workers spent an average of 11.6 years with their employers, while the non-rural average was 13.2. Also, the average annual compensation for rural workers was even slightly higher than for non-rural workers. Important changes had taken place which explain this turn: The amnesty of 1979 and the progressive return to a democratic system coincided with workers’ organizations (both rural and non-rural) pursuing more explicit avenues for claiming their rights. Pernambuco’s sugarcane area was a pioneer in this respect, as cane workers mobilized extensively and mounted a large strike in 1979. The 1980s brought a successful effort to democratize unions.Footnote 43

INTERPRETATIVE AND COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES: HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE PAST FIFTEEN YEARS

This section places our empirical findings in dialogue with historiography from Brazil and other parts of the world, primarily Africa, India, the Caribbean Basin, and the US. Three central themes emerge from our work: free and unfree labour, the role of the state in labour relations, and the tension between backwardness and modernity in the treatment of rural workers.

Rural labour occupies a curious place in Brazilian historiography. One of its peculiarities is that the volume of work on rural slaves in colonial and post-independence times far outstrips the more modest literature on free rural workers after abolition. This, however, not only constitutes an imbalance, but also speaks to an analytical opportunity, since continuities between slavery and free labour mark Brazilian history. As scholars have long observed, bonded and free labourers can be placed within the same analytical frame. The first main interpretation of our evidence drawn from the labour court documents is that the line between free and unfree labour is, across time, both fundamental and often blurred, and rural workers’ experiences after the ETR bear out that fact. João José Reis’s careful research about a major strike by mostly black workers in Bahia in 1857 offers a nineteenth-century example, as he describes a labour market where slaves and freedmen routinely worked side by side and found themselves confronting shared challenges. While this strike shows us the porosity of the slave/free boundary, it also points to how the status of labourer was inextricably mingled with other identifications: Ethnicity, and specifically anti-African prejudice, proved a more salient variable for these workers than the question of freedom. They were not blind to the difference, obviously, and slaves had to abandon the strike soon in response to their masters’ orders. But slave or free status was one among many axes of difference, with ethnicity and occupation playing roles too.Footnote 44

Just as blurry as the line between slave and free for people of African descent until abolition in 1888 is the divide between the era of slavery and the age of freedom. When did slavery end, and for whom? Beatriz Mamigonian and others have shown that the path to freedom in the years preceding the definite end of slavery could be circuitous, even for groups legally entitled to their emancipation.Footnote 45 Even after official abolition, in 1888, patterns of unfreedom – marked by coercion and exploitation – persisted in Brazil and beyond.Footnote 46 Yet, it is not only the real continuities of unfreedom in different forms and degrees that compel the use of the labour history of slavery to address the field of rural labour history – indeed to merge these fields. In addition, the fluid categories used to describe these realities under slavery remained fluid after its end, as Sidney Mintz has shown.Footnote 47 In the case of the rural workers analysed in this article, the category “wage-earner” has a dubious specificity as a label. Instead of (or in addition to) an identity defined by race, this one was (and is) defined by what these people were doing to earn money, namely agricultural labour.

In his study of rural labour in a Puerto Rican sugarcane district during the period of emancipation (slavery there was only abolished in 1873), Luis Figueroa describes how libertos’ actions and their interpretation by others depended on the larger system in which they made their decisions. “Slavery, of course, constituted not simply a labour system”, Figueroa points out, “but also a system of power relations, of behavioural codes that provided a powerful justification for domination, for sorting people out in particular ways, even if those codes were not always followed”. The apparent exercise of freedom by libertos concerned Puerto Rican elites, who reacted by labelling their mobility as vagrancy or worse. They moved swiftly to erect new barriers to restrict the freedpeople’s options.Footnote 48

Sidney Chalhoub, another of the eminent scholars on this question, analyses an oppressive reality beyond the freedom–slavery dichotomy. Although freed Afro-Brazilians constituted a sizeable group in Brazilian society in the last decades before abolition, “[b]lack people saw their life marked by the threat of enslavement”, Chalhoub writes, and his work shows that free persons of African descent or freed ex-slaves consistently faced this danger.Footnote 49 Many of the post-independence authorities’ administrative measures, such as the census, were interpreted (even if mistakenly) as hidden manoeuvres to achieve such ends. This was reinforced by the persistence and naturalization of racialized thought, which filtered into public policy and found a forceful expression in the preference for “white” immigrant workers.

We see the treatment of rural workers by the state – from the beginning of the First Republic in 1889 through the state-interventionist period since 1930 to the years of military dictatorship from 1964 on – as an extension of this principle, following Igor Kopytoff’s proposal that “slavery should not be defined as a status, but as a process of transformation of a status that can last a whole life or even spread down to further generations”.Footnote 50 Proof of it lies in rural workers’ exclusion from legal protections until 1963 with passage of the ETR, as well as the differentiation in minimum wage and pensions, which for rural workers was just half of the non-rural level.

Scholarship on the Caribbean offers additional insight into government-enforced systems of exclusion that persist even when they clash with the state’s declared principles. Miranda Spieler has shown this for the French in Guiana, with a broader range of categories of people subjected to exploitation and discrimination, including in and by court systems.Footnote 51 She documents the travails of Amerindians, African slaves, African immigrants, their descendants, political and common law European prisoners, and former prisoners. Among the common dimensions of this downtrodden population, the lack of access to the ownership of land is the most salient.Footnote 52

The range of victims of this French system, coming from so many origins, suffering in spite of the nation’s long tradition of revolutions and reiterated declarations of human rights, reveals one of the essential features of the phenomenon we study in Brazil: The French Third Republic’s ideology enshrined the idea of a nation in which small farmers and soldiers occupied a central place. In Guyana, however, it was particularly these groups who were subject to open discrimination and could only serve as field hands, not independent farmers. Authorities of a theoretically progressive state, then, created a “new sort of historical subject”, nominally free but without citizenship “who lived with considerable legal incapacities and was struck by policing mechanisms that narrowed the difference between slavery and freedom”.Footnote 53

One can make compelling comparisons along these lines with the United States.Footnote 54 Historian Greta de Jong’s descriptions of African-American experiences in twentieth-century Louisiana could have come from Pernambuco. “The plantation elite’s control over people and resources in rural Louisiana was never absolute”, she writes, “but it often seemed close to being so. Some parishes resembled personal fiefdoms, governed by a few individuals or families whose influence extended over everyone in the community, white or black.”Footnote 55 De Jong writes, “[p]overty, inadequate education, disfranchisement, and the threat of violence discouraged organizing efforts, while plantation owners’ control over economic resources, political offices, and the law enabled them to stifle most challenges to the system”.Footnote 56 Pernambuco’s rural workers suffered a similar lack of access to education and almost complete exclusion from political processes, since literacy was required to vote until 1988. And of course De Jong’s reference to control of the courts resonates with our study. Furthermore, there are parallels in the historical shifts of labour relations in sugar cane: By the 1930s, eighty per cent of Louisiana sugar plantations workers earned wages, as opposed to working through traditional arrangements. Earlier norms had kept workers tied to their employers through access to land for gardens, firewood, and houses, just like similar tenancy agreements in Pernambuco. There, the transition began around the same time, but arguably culminated only during the period we study in this paper.Footnote 57

Our second interpretative theme revolves around essentially the same question from a different perspective. In this case, we focus on how patterns of rural labour exploitation persist through and because of state action and complicity. We see helpful guidance in Ranajit Guha’s approach from his famous work on peasant insurgencies in India. He interprets colonial bureaucratic documents as constituting a particular genre. District officials writing about episodes of peasant revolt and insurgency actually composed narratives, or history, Guha writes. These descriptions and explanations obeyed a coherent logic that negated the possibility that the peasants had a larger project than violence and reaction and thereby negated their actions’ political content. Famously, to tease out these contents, Guha employs a method to read the documents “against the grain”, as evidence of the ideas and motivations of the peasants.Footnote 58

Like these colonial documents and their discursive logic, our court cases employ the language of power and the state. The cases’ results and the figures involved in the compensation sometimes offered to workers at their conclusion can be understood as effects of the visions of power and culture held by their authors – the judges. Rural workers’ visits to courts had predictable outcomes, in part because of the class perspective of the judges. Following Guha, we argue that there were patterns, that the “prose” of those in power was coherent and followed a logic. Our documents mirror Guha’s “primary discourse”, which he says came almost entirely from the realm of officials, revealing the structures of power that their authors served. However, different from the specific instances of Guha’s study (which focuses on moments of rebellion and counterinsurgency in a context of colonial domination) the rural workers in Pernambuco dealt with an institution that was imbued with a language of rights leaving, despite all limitations, a larger margin to the workers to bring in their own logic and employ the official discourse to their benefit.

The crucial role of the state is borne out in the sugar cane plantations of Louisiana mentioned earlier. Whereas workers in Pernambuco had to wait for the ETR (1963) to unionize and collectively negotiate with planters, the Louisiana Farmers’ Union (LFU) was formed in 1937. Its influence over the conditions workers faced was limited, but it began the process of challenging planters’ power. The LFU’s complaints were very similar to those rural workers’ unions lodged in Pernambuco in the 1960s and 1970s: inadequate wages, receiving pay in coupons for the plantation store, excessive prices at those stores, and a lack of access to land to grow their own food.Footnote 59 Mechanization began to spread in Louisiana in the 1940s, whereas it would only come to Brazil in the 1980s and later.

Douglas A. Blackmon’s work on Alabama echoes De Jong’s on Louisiana and provides another powerful comparison to Pernambuco. He describes how post-abolition Lowndes County, Alabama, became a region where “the war seemed to have had little effect on the question of whether slavery would continue there […] [T]he landholders who remained reforged an almost impenetrable jurisdiction into which no outside authority could extend its reach.”Footnote 60 This characterization also captures Pernambuco’s sugar cane during the military dictatorship until the late 1970s when the rural workers managed to organize and launch successful mobilizations. As Blackmon puts it, the county’s African American residents were “no longer called slaves but liv[ed] under an absolute power of the whites nearly indistinguishable from the forced labour of a half century earlier”. As in Brazil and Guiana, land concentration helped perpetuate the problem. “Black land ownership in the county was inconsequential”, Blackmon writes. “Where it existed on paper, the appearance of independence was a chimera behind which local whites continued to violently control when and where blacks lived and worked, and how their harvests were sold.”Footnote 61

He also touches on the difficult subject of sexual exploitation of women, and emphasizes the “environment of overt physical danger that existed in Lowndes County”.Footnote 62 As we have mentioned, violence rarely breaches the surface of our court files, yet its pervasiveness was well known. The same can be said for the obstacles that landlords both in Alabama and Pernambuco erected against any educational effort.Footnote 63 Although a national law had, since 1973, obliged employers of fifty or more wage-earning workers to open a school,Footnote 64 few employers complied, even after redemocratization in the mid-1980s.

Despite the sweeping and largely progressive nature of the Brazilian labour law introduced during the corporatist Vargas years and after (CLT 1943; ETR 1963), workers’ and unions’ attempts to secure its fruits have met with only limited success, especially in those regions of the country that were based on a near-monopoly of land and cheap agrarian labour. To explain this gap, John D. French argues that Brazilian legal culture generally is marked by fluidity and regional differences. Other aspects of social organization – the ongoing power of patronage networks, the social weight of prestige, etc. – militate against full compliance with labour law.Footnote 65 Along these lines, Antônio Montenegro pointed out in a study about a Pernambucan plantation that the class origin and educational background at the Recife Law School of the rural judges formed a convergence of values and criteria.Footnote 66

James Scott’s work offers a useful reminder of the relationship of bureaucrats to the populations they supposedly serve. Speaking of “the growing armory of the utilitarian state”,Footnote 67 he stresses that “officials of the modern state are, of necessity, at least one step – and often several steps – removed from the society they are charged with governing. They assess the life of their society by a series of typifications that are always some distance from the full reality these abstractions are meant to capture”.Footnote 68 We can understand the rural judges taking a detached, bureaucratic perspective along these lines as they discriminated between rural and non-rural cases.Footnote 69

Alejandro Gomez and Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s studies of the impact of the Haitian Revolution and other rebellions on nineteenth-century slave societies also demonstrate the degree to which fear informs the state in such unequal societies. In their case, a dominant class – planters – played a significant role within the ideology of the state apparatus regarding rural workers, contributing to “structure an imaginary based on [a] lesson from the past”, about the looming danger of popular revolution.Footnote 70

Gomez’s observation points us toward our final interpretative theme. In describing how planters collude with the state in drawing forward this “lesson from the past”, he gestures toward the ways that modernity and archaism can blur into one another. This phenomenon, in turn, helps reinforce our previous exploration of the indistinct boundary between free and unfree labour and the importance of the state. Pernambuco’s labour courts exercised their function according to a specific kind of what Scott calls “high modernist ideology”.Footnote 71 At the same time, they were vulnerable to the influences of personal class origins and a predominant cultural heritage that systematically took the extremely unequal distribution of assets, income, and power for granted while underrating whatever is rural, even in a region that derives its wealth from this sector, as in India, the southern US and colonial France, evoked above. Although governed by modern states by any measure, these places subjected rural workers of various origins to subaltern legal status, preventing them from enjoying the exact same treatment as urban-industrial proletarians. Rural court cases reveal a trend also visible with surprising consistency across various chronologies in other capitalist countries with comparable state ideologies and the realities they produce. Sidney W. Mintz discusses the condition of Chinese, Javanese, and Indian contract workers transported to the Caribbean. Their situations and conditions are similar to those Miranda Spieler describes, as well as what Paulo Terra has shown about distinctions between workers as blind spots for questions of ethnicity or juridical status.Footnote 72 It could be understood in parallel with Ravi Raman’s study of tea plantations in India (another Eurocentric production process, like cane in Brazil), where a system, sometimes called “patriarchal”, disciplined dalits in a social hierarchy rooted in a racialized division of labour.Footnote 73

Mintz affirms that such situations present a challenge to moral logic. He argues that the extreme exploitation and mixture of peoples represent, as in Pernambuco’s cane fields, “precocious modernity”, even if it went unnoticed at the time and later. Observers could ignore it, because it was

happening to people most of whom were forcibly stolen from the worlds outside the West. No one imagined that such people would become ‘modern’ – since there was no such thing; no one recognized that the raw, outpost societies into which such people were thrust might become the first of their kind.Footnote 74

In a sense, following Mintz, Achille Mbembe provocatively suggests the “Becoming Black of the world [le devenir-nègre du monde]”.Footnote 75 African slaves and others who endured similar conditions were just the first ranks of a world proletariat. From such a perspective, legal protections and workers’ rights, though long seen as signs of social evolutionary progress, ineluctable and universal in range, as societies reach development and democracy are, arguably, little short of a parenthesis. Mbembe suggests that “the system[ic] risks experienced specifically by Black slaves during early capitalism have now become the norm for, or at least the lot of, all of subaltern humanity”.Footnote 76 As Mintz suggested, modernity first appeared on the sugar plantations of the Americas and is now global. Mbembe bears out the argument that the globalization of capitalist modernity has placed “subaltern humanity” at the mercy of the same risks African slaves faced.

Our files show a continuity of this logic of radical exploitation and the attempt by the modern Brazilian state, on its way to “development” and “democracy”, to create a legal façade for such a logic. But, for rural workers, this veneer always remained quite thin. Employers often responded with immediate non-compliance vis-à-vis requirements, such as the registration of wage earners and resorted to even further marginalizing the rural workers through casualization and eviction from garden plots, reducing them to the status evoked by Mbembe.

Thus, while the Brazilian state displayed a strong thrust towards modernizing society – which, among other things, allowed for the installation of an “inclusive” institution such as the rural labour courts – the mindset of local public officials, conforming to a specific class perspective and complicated by various prejudices, remained faithful to the social realities of their regions. In that, they reproduced deeply rooted ideas about the distinction between rural and urban, agricultural and industrial, archaic and modern. This resulted in a state ideology in which the city and industry seem privileged sites of civilization, and in which urban activities are presented as inherently superior to rural. The JCJs of Pernambuco demonstrate the ambivalent simultaneity of the “archaic” and the “modern” and in their findings their judges served more to conceal than to attest to the fundamental facts of the lives of rural cane workers in Pernambuco and so many other workers in most world regions: a permanent exposure to, as Mbembe calls it, “systemic risks” and the pervasive experience of physical violence.