1. Disability and human experience

Disability is a fact of human life. One will invariably experience various impaired states over the course of any given life, and one will become significantly impaired as a product of aging, if nothing else, should one live a long life. Testimony by disabled people concerning the relationship between their experiences and overall well-being has long been an object of social scientific and humanistic study. Yet, the ubiquity of disability experience, combined with the widespread assumption that disabilities are characterized simply by lack, has led some to treat testimony concerning the relationship between disability and lived experience to be subject to common sense. Often discussed in terms of “the disability paradox,” a contrast is typically set up between the intuitive horribleness of certain impaired states and the testimonial evidence suggesting that people in such states do not in fact experience their lives as horrible. Explanations for why that testimonial evidence is suspect range from claims about adaptive preferences to issues of qualitative research methodology (cf. Barnes Reference Barnes2009).

In this paper, I argue that the problem lies not with the evidence, but the intuition in question. Using the disability paradox as a case study, I further argue against the use of the concept of intuitive horribleness in social epistemology. I contend that testimonial and hermeneutical injustice are baked into most deployments of the concept, and even if one were to convincingly justify its use in select cases, it should be accompanied with prima facie suspicion. In conclusion, I discuss the implications of this analysis for the literature on transformative experience, an account on which intuitively horrible experiences are taken to present serious problems, and also for the stakes of multi-cultural, historically informed philosophical analyses more generally.

2. The disability paradox

The “disability paradox” was first formulated in 1999 and has since then taken on a life of its own in the humanities, social sciences, and various clinical domains (e.g., see Fellinghauer et al. Reference Fellinghauer, Reinhardt, Stucki and Bickenbach2012; Honeybul et al. Reference Honeybul, Gillett, Ho, Janzen and Kruger2016).

The common understanding of a good quality of life implies being in good health and experiencing subjective well-being and life satisfaction [Goode, 1994]. Conversely, one can argue that if people have disabilities, they cannot be considered to be in good health nor possess a high level of life satisfaction. People with disabilities are assumed to be limited in function and role performance and quite possibly stigmatized and underprivileged [Brown et al., 1994]. Kottke [1982, 80], a distinguished expert in rehabilitation medicine, expresses this view when he states that ‘the disabled patient has a greater problem in achieving a satisfactory quality of life. He has lost, or possibly never had, the physical capacity for the necessary responses to establish and maintain the relationships, interactions, and participation that healthy persons have.’ Research evidence, however, presents a more complex picture. In practice, the anomaly is that patients' perceptions of personal health, well-being, and life satisfaction are often discordant with their objective health status and disability [Albrecht and Higgins, Reference Albrecht and Devlieger1977; Albrecht, 1994]. (Albrecht and Devlieger Reference Albrecht and Devlieger1999)

The disability paradox is fundamentally animated by assumptions concerning that which is intuitively horrible.Footnote 1 Furthermore, the framework of the paradox involves two major assumptions: (i) disability experiences are both knowable and accessible to able-bodied people and (ii) judgments concerning intuitively horrible experiences are not subjective, but objective. Note that Albrecht and Devlieger begin with a reference to “common understanding,” and this concept appears to function in a roughly similar way to that of “intuition.” One might counter that although they refer to and rely upon “common understanding,” the ultimate authority concerning the relationship between well-being and disability is placed in medical expertise – in this case, a “distinguished expert in rehabilitation medicine.” Yet, that would mistake a superficial rhetorical move (put less charitably, an argumentum ad verecundiam) for the underlying argumentative force. Albrecht and Devlieger assume that readers already agree with “the common understanding of a good quality of life” as defined by “being in good health and experiencing subjective well-being and life satisfaction.”Footnote 2 They then immediately imply that disability, whatever else it is, involves lacking good health and a high level of life satisfaction, so the invocation of a medical expert buttresses what they take their readers to already assume to be true. The “research evidence” surprises the reader as well as the experts by suggesting that they are both wrong – or at least they seem to be so relative to the testimony of those who in fact have had the experiences in question.

In summary, the claims of disabled people concerning their wellbeing appear paradoxical just insofar as intuitions by non-disabled people concerning the (objective) horribleness of their experience hold. This is significant, for charges of intuitive horribleness often play a decisive role in social epistemology debates. I argue below that these intuitions are wrong in a way that not only runs afoul of social scientific research but also concerns of epistemic injustice. First, however, and to better appreciate the power of the claim of “intuitive horribleness,” I turn to consider its function in debates over transformative experience, focusing upon what has recently been termed “the shark problem.” The intuitive horribleness asserted relative to this problem is in fact a species of the disability paradox and one that specifically conflates the value of an epistemically transformative experience with that of a personally transformative experience.

3. Intuition and horribleness

L.A. Paul writes, “in cases like [being eaten by] sharks, we don't need to perform an assessment of the outcome by cognitively modelling what it would be like, because we know what the results would be: we know every outcome is bad, whatever it is like” (Paul Reference Paul2014: 128; cf. 27).

Campbell and Mosquera generalize from this quote to develop what they call:

The Shark Claim: One can evaluate and compare certain intuitively horrible outcomes (e.g., being eaten alive by sharks) as bad, and worse than certain other outcomes even if one cannot grasp what these intuitively horrible outcomes are like [cf. Paul Reference Paul2014: 127; cf. 27]. (Campbell and Mosquera Reference Campbell and Mosquera2020: 3551)

Campbell and Mosquera continue by noting, “Paul discusses other examples such as being hit by a bus and having your legs amputated without anesthesia [Paul Reference Paul2014: 28, 127; 2015: 802–3].”Footnote 3 They contrast the shark problem with what they call the Prior Experience Claim, which is at the core of Paul's theory of transformative experience:

The Prior Experience Claim: One cannot evaluate and compare different experiential outcomes unless one can grasp what these outcomes are like, which one can do only if one has previously experienced outcomes of that kind [cf. Paul Reference Paul2014: 2, 71–94]. (Campbell and Mosquera Reference Campbell and Mosquera2020: 3551)

“Evaluation” and “comparison” are here construed as functions of cognitive modelling. By virtue of having experiences of X kind, it is assumed that one can cognitively model outcomes pertaining to X in such a manner that one can judge – evaluate and compare – their subjective value. “Subjective value” just means, following Paul, the value(s) attached to undergoing X kind(s) of experience(s). As she details at length, the prior experience claim is especially pertinent to experiences the undergoing of which transform one as a knower. The following problem immediately arises: what distinguishes transformative experiences, to which the prior experience claim applies, from sharky experiences, to which the Prior Experience claim does not apply despite one not ever having undergone such experiences?

Campbell and Mosquera attempt to solve this problem in two ways.Footnote 4 They first adopt an approach that assumes a precise boundary between the two sorts of experience. This, expectedly, runs into the sorites paradox, and so they dismiss that solution. They then turn to a vagueness approach. After exploring supervaluationist, epistemicist, and ontic vagueness accounts, they argue that none solve the problem. This is because whether one focuses upon linguistic indecision, ineliminable uncertainty, or vagueness “out there” in the world, the problem of drawing a non-question-begging distinction between ‘normal’ and ‘sharky’ cases of the evaluability of outcomes remains.Footnote 5 On this basis, they conclude that the shark problem is indeed a threat to Paul's account of transformative experience. But this conclusion is wrong for two reasons: (A) the experiential kinds under discussion fail to characterize the core issue of personally transformative experience. (B) the real “shark problem” has been misidentified as a merely epistemological concern without taking into account its larger normative dimensions. I first address (A).

Paul herself distinguishes between experiences that are epistemically transformative, which provide novel phenomenological content and can't be cognitively modelled, and experiences that are personally transformative, which provide novel phenomenological content, can't be cognitively modelled, and also alter one's sense of self, priorities, preferences, and the like (2014: 155–56; cf. Barnes Reference Barnes2015).Footnote 6 Paradigmatic cases of personally transformative experience include: “becoming a vampire,” “being a parent,” “becoming religious,” and “being in love.” By contrast, “eating a durian,” “seeing the aurora borealis,” and “flying in a plane” are cases of epistemically transformative experience. These two types are regularly run together by Campbell and Mosquera (see, e.g., 2020: 3550), but they are distinguished by Paul:

If we had individual-level data that could tell us how likely a particular outcome was for us and how we'd respond to it, then we could argue that big life choices should be made in the same way that we choose not to step in front of a bus or to be eaten by sharks. In cases like the bus or the sharks, we don't need to perform an assessment of the outcome by cognitively modeling what it would be like, because we know what the results would be: we know every outcome is bad, whatever it is like … But for the sorts of big life choices I've been focusing on, we don't have sufficiently detailed data to do this, and it's not clear we ever will. (Paul Reference Paul2014: 127, my italics)

When Paul refers to “big life choices,” this is a shorthand for experiences which are personally transformative, not merely epistemically transformative. Note that the same event or process can be both epistemically and personally transformative, which, tellingly, is the sort of case of chief interest with regard to decision theory and transformative choice.

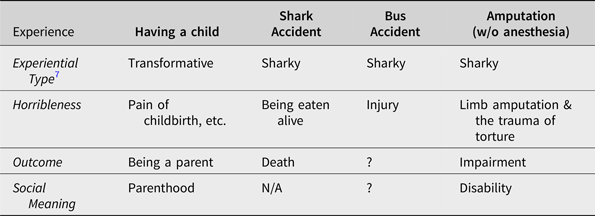

In what follows, I contrast Paul's central case of transformative experience, being a parent, with the three most discussed cases of the shark problem: being eaten alive by sharks, being hit by a bus, and having one's legs amputated without anesthesia.

Note first that horrible experiences pertaining to having a child can be treated as distinct from its overall outcome and its larger personal and social meaning, even if they turn out to be both necessary and genuinely horrible experiences along the way for a given person.Footnote 8 This is very different than the case of “being eaten alive by sharks” since it is formulated in such a manner that death is the outcome. Claims about the intuitive horribleness of death present unique problems, for we cannot experience our own death, only our own dying. I will instead assume that as a result one is injured in some ways but has not died from the attack.Footnote 9 In the case of a bus accident, it is hard to know what to make of the example. Without any information about what happens after the accident, one could imagine outcomes ranging from a mere scratch and scare to living in a coma for years to immediate death. Because it is constructed in such a vague manner, I'll largely ignore this example going forward.

With respect to the third example, an amputation does not necessarily result in death, and I take both Paul and also Campbell and Mosquera to assume it does not. The fact that there is no anesthesia involved is curious and sets up a strange contrast between the three cases. Unless one is in total shock, the experience of being chewed upon by a shark will be exceptionally painful. Being hit by a bus may also result in exceptional pain or instead in one feeling (and perhaps also remembering) nothing at all, especially if the accident involves a traumatic brain injury. Leg amputation without anesthesia, also unless one is in total shock, will be exceptionally painful, but in a manner that is additive. One would presumably be aware of the fact that it would not be painful or would at least be less painful if anesthesia were administrated, and knowledge that pain is being inflicted on purpose or needlessly can itself intensify pain experience (Linton and Shaw Reference Linton and Shaw2011). It seems as though the “no anesthesia” qualification is meant to focus one's attention on the discrete event of the amputation and the intuitive horribleness of that event.

Insofar as a leg amputation results not only in an epistemic transformation (one the mere content of which is likely not itself worth the pain), but in a personal transformation (one the content of which I cannot know without being changed as a person), then focusing on the intuitive horribleness of the amputation goes only partway. Whatever purchase the claims of intuitive horribleness may have for epistemically transformative experiences, they do not necessarily transfer to personally transformative experiences. Since I take Paul's work to ultimately focus upon the latter, not the former, the pertinent question is instead about the intuitive horribleness of post-amputation life. It is about how one is transformed upon becoming, for example, a wheelchair or prosthetic user. I return to this point below.

Further note that in the distinction between epistemic and personal transformation, a temporal dimension is at play. The real-life cases L.A. Paul focuses upon – things like becoming a parent – are complex processes that span months, if not many years.Footnote 10 At what point upon becoming a guardian of a child one is “a parent” is left unspecified by Paul's account and, it seems to me, for good reason. It is not clear that parents with an eight-month-old child in utero are in the exact same epistemic or personal-existential position as parents with a toddler or parents with an angsty adolescent, etc. This is not a problem for Paul's account because her argument doesn't depend on whether the “day of birth” parent or the “three-year-old” parent or the “angst-ridden teen” parent are in the same relevant situation; the point is that each are sufficiently different, not identically different, from the non-parent with respect to being changed as a knower and with respect to how the meaningfulness of being a parent (not merely the innumerable, various discrete acts involved in parenting) changes them as a person (shifts in values, preferences, etc.).Footnote 11

Discrete events and extended affairs, projects, and ways of being are different sorts of things – the contrast is as strong as that which changes a very minor, nearly meaningless aspect of one's experiential landscape (eating a Durian for the first time, learning what it is like to taste Durian, and, thereby, coming to like or dislike Durian) vs. that which changes one as a person (becoming a parent, being a parent, and, thereby, coming to be the sort of person who is a parent). Furthermore, while the latter is likely to have a significant set of social and political ramifications, the former does not. There are distinctly temporal, existential, and socio-political considerations at play when we consider the distinction between epistemic and personal transformation.Footnote 12 And, as I discuss at length in sections 4 and 5 below, there are also normative considerations.

Let us return to the sharky case of leg amputation and its relationship to intuitive horribleness. What does leg (lower, upper, or what have you) amputation necessarily result in? Disability. It means one will no longer be able to walk solely using the means of one's biological body (assuming one was ambulatory before). On a social model of disability, amputation necessarily results in impairment in the sense that one's body shifts from a phenotypical to an aphenotypical form (in this case: in shape, overall function, and mode of movement) (Cross Reference Cross2016; cf. Silvers Reference Silvers and Parens1998). It also necessarily results in disability in the sense that one will now encounter a world not designed for one – one will instead encounter a world by and large designed for ambulatory people. That is to say, one must now live in a world in which wheelchair users (or prosthetics users, etc.) are often stigmatized and in which one must deal with the many, complex effects of ableism, whether with respect to social life, employment, healthcare, political representation, or what have you (Toombs Reference Toombs1995; Kafer Reference Kafer2013).

Social scientific research concerning people with lower leg amputation offers evidence regarding its horribleness. It turns out that the “intuitive horribleness” with respect to becoming paraplegic through a traumatic event gets one aspect of such experience correct: it is a difficult ability transition. It can throw people into depressive and suicidal states, especially during the first one or more years (Kennedy and Rogers Reference Kennedy and Rogers2000). But that research also shows that afterwards many people come to find new normal, new modes of flourishing, and come to enjoy their new paraplegic life (Kennedy and Rogers Reference Kennedy and Rogers2000).Footnote 13

Does being paraplegic in and of itself mean one's life will necessarily go worse? No. There is a significant body of work showing such a claim to be false (e.g., Barnes Reference Barnes2016; Begon Reference Begon2020). This research demonstrates that the relationship between various impaired/disabled states and well-being is instead extremely complicated (Campbell and Stramondo Reference Campbell and Stramondo2017). That relationship is a product of a host of contextual factors, not factors merely pertaining to one's form of embodiment (cf. the exchange between Barnes Reference Barnes2018; Francis Reference Francis2018; Howard and Aas Reference Howard and Aas2018).Footnote 14

In short, and as Elizabeth Barnes has argued in the greatest detail, disability is not bad simpliciter. However one ultimately judges this literature, to focus merely on the moments of becoming-impaired (and especially if that transition involves painful, even tortuous experiences), misses the point about not simply what it is like to be disabled in this or that manner in a narrow sense, but what lived experiences of disability amount to in any given case. To focus on the moments of a shark attack or the moments of amputation, anesthetized or not, fails to appreciate the import of the thesis of personally transformative experience and instead functions as a red herring by focusing upon discrete, highly painful experiences and/or ability transitions that ignore or distort a wide range of evidence concerning the lived experiences of disability.

Being non-ambulatory will result in one experiencing a world designed for ambulatory and otherwise able-bodied people. That world is often frustrating to navigate and frustrating in many other respects due to the exclusions of the built world, a world which does not, on the whole, practice universal design, but instead able-bodied design (Hamraie Reference Hamraie2017). Still if one listens to the testimony of people who in fact use wheelchairs for mobility, that doesn't thereby make such a life horrible (Mairs Reference Mairs1996; Kafer Reference Kafer2013).

Let us assume that, at minimum, you must use a wheelchair of some sort to get around after either of these events. What does research say about the well-being of wheelchair users with respect to their use of wheelchairs? It suggests that most experience the use of a wheelchair as freedom, as a tool that affords them self-determination to do a host of activities (Wolbring Reference Wolbring, Lightman, Sarewitz and Desser2003). Depending upon context, certain electronic wheelchairs allow greater, faster, and – for some – even more enjoyable freedom of movement than using one's own two legs would (just consider the amount of people who purposely and joyfully use scooters, electric bikes, or any number of other powered devices to get from point A to B as opposed to simply walking).Footnote 15 In sum, the mere fact that one uses a wheelchair does not entail that one's life will be horrible, and intuitions that it will be horrible fly in the face of evidence concerning the lived experience of those who actually use wheelchairs (Galli et al. Reference Galli G., Canzoneri E, Blanke and Serino2015).Footnote 16

Consider the following argument: while L.A. Paul is right to claim that while we cannot judge what it means to be a parent because becoming a parent transforms us a knower, we can nevertheless judge the pain of childbirthFootnote 17 to be horrible or the raising of a child who is consistently violent towards and abhors one as horrible or the early death of one's child as horrible. While the intuitive horribleness of each of these may be related to any given case of parenthood, none – even in combination – exhaust the meaning or overall lived experience of parenthood as a whole. Those events do not capture the meaning of being a parent. They are claims about intuitive horribleness that treat the experientially discrete as a synecdoche for the experientially continuous. They mistake gaining novel phenomenological content through a bad experience for being transformed as a person as a result of those gains in combination with a range of other factors in the context of the meaning-making forms of life.

But this is not all – they also overgeneralize the character of the discrete, supposedly intuitively horrible, events in question. For example, a not insignificant number of women go out of their way to have an unmedicated birth, and, in effect, actively seek out experiencing its pain more fully (Ossola et al. Reference Ossola, Ampollini, Gerra, Tonna, Viviani and Marchesi2019). Complicating the matter further, a large number of births are, on the contrary, medicated and hence not especially painful (Butwick et al. Reference Butwick, Bentley, Wong, Snowden, Sun and Guo2018). Even if for a given individual, or group, the pain of childbirth were traumatizing, even if, to consider a possibility that is very distinct, one's child were to turn out consistently violent and hateful or dies at an early age, none of these hypotheticals will definitively decide the debate over the way in which becoming a parent shifts the parameters of one's judgment, evaluations, preferences – i.e., one's standing as a knower – concerning parenthood. Note that whatever happens over the course of hours, days, weeks, months, or even years is not necessarily definitive of a form of life, a determinate way of being in the world. In this experiential and reflective span lies the theoretical rub. The thesis of personally transformative experience is ultimately about existential ventures and undertakings, not isolated events and activities.

To take another of Paul's central examples, consider how strange it would be to claim that Paul's opening discussion of becoming a vampire fails to demonstrate the problem of transformative experience merely because being violently bitten in the neck is intuitively horrible (I am happy to admit that I judge being so bitten, i.e., non-consensually, as intuitively horrible). In the same way, to infer from the presumed intuitive horribleness of childbirth – or fill-in-the-blank with respect to what can happen over the course of parenting – to the intuitive horribleness of being a parent is patently misguided. And yet the shark problem, assuming it doesn't end in death as I qualify the problem above, makes precisely that argumentative move. This is a mistake.Footnote 18

3.1. The real sharky problem

I claimed above that the implications of the “shark problem” are wrong for two reasons: (A) the experiential kinds under discussion are indefensibly diverse and fail to characterize the core issue of personally transformative experience, and (B) the real “shark problem” has been misidentified as a merely epistemological concern without taking into account its normative dimensions. Having addressed (A), I now turn to (B).

The problem of distinguishing between sharky and non-sharky problems turns on how we typologize experiences and how we judge others’ experiences in relation to a given typology. Call the results of typologizing experience experiential kinds. While assessing experiential kinds will perforce involve definitions and various criteria, such assessments will also invariably involve norms. These will include norms about how we judge experiences far from our own but in connection with the same experiential kind. To get a sense of this way of framing things, consider those who have a dog and thereby assert that they are in a solid epistemic position to make claims about human parenting or those who are secular, yet intrigued by and in principle open to the idea of the divine, and thereby assert that they are in a solid epistemic position to make claims about living a religious life. One might respond (as I would): “being a dog person” is one sort of experiential kind; “being a parent” is another. “Being open to the divine” is one sort of experiential kind; “being actively religious” is another. Whether or not we take ourselves to have purchase on a given experiential kind is important. The more pressing issue – at least relative to the concerns at hand – is how we take up and integrate testimony from others concerning experiential kinds that we intuitively consider to be close or even identical to our own.

There is a large anthropological literature focused upon analyzing practices that one society/culture judges as intuitively horrible and that another society/culture judges as not merely reasonable, but even required (rituals of maturity, acts to create and solidify in-group bonding, practices to accomplish certain gender norms, etc.). An obvious and hotly contested example is female circumcision, also referred to as female genital cutting (Abusharaf Reference Abusharaf2013). I will not here take a stand on that debate, and my argument does not require doing so. I bring it up simply to note the large body of work that suggests a defining part of what is at stake in claims of intuitive horribleness to be not simply a question of extrapolation from one's experience to different degrees of that experience, but instead a question of how various values inform one's judgment about what counts as horrible or not horrible in the first place and the way in which one takes up or denies the testimony of others, including groups of others and including the traditions, histories, cultures, etc., in and by which they anchor their testimony.

I take this to be part of the insight of Paul's work on personally transformative experience: it is the unique and social quality of certain transformative experiences that result (or fail to result) in personal transformation (cf. Barnes Reference Barnes2015). The convert to Jainism does not, without further analysis, undergo the exact same experience as the convert to Buddhism or Christianity or Islam – nor do all parents undergo the same experience of parenthood.Footnote 19 All of these might, on Paul's account, qualify as personally transformative experiences, but the extent to which they are similar requires one to take up the testimony of others and to look to other forms of evidence as well – most notably qualitative social scientific evidence concerning the particularity of those religious traditions and the ways in which a given person does or does not take up aspects of a specific tradition relative to their sociocultural, historical, and political context. The qualitative differences between transformative experiences that we treat of an experiential kind are a crucial part of how we analyze and argue about the meaning of not only the transformative experiences in question, but transformative experience more generally.

Even if there were a person who, across some period of time, converts to Jainism, then Buddhism, then Islam, and then Shinto, it would be strange to find them an expert on the conversion between each to each or even of “conversion” itself. On the contrary, we would rightly wonder whether or not the many shifts instead indicate something about the relative depth of the transformative nature of these conversions if the shifts in religious affiliation change in such a way. This is not to say that this person would necessarily be inauthentic; it is instead to say that whatever they experienced would be prima facie different from one who converts and then holds to that conversion dearly for the rest of their life.Footnote 20 Therein lies the rub: philosophical investigation into lived experience involves dimensions that go far beyond both testimony and intuition.

Consider how common it is for able-bodied people to think they know something about disability insofar as they can “imagine” what it is to be without an ability they have, often assuming that “disability” simply means the lack of some given ability.Footnote 21 An able-bodied academic person might think, for example, “Surely I know what it is like to use a wheelchair. I sit in a chair most of the day with wheels. It takes little to extrapolate from that to using a chair to get around for all my tasks.” The sighted person might think that by closing their eyes and/or walking around with a “blindfold” for a bit they have a sense of what it means to be blind. A wide range of humanistic, social scientific, and scientific evidence spanning decades points in the opposite direction (Magee and Milligan Reference Magee and Milligan1996; Hull Reference Hull1997; Glenney Reference Glenney2013).

If this seems strange, and without getting lost in the minutiae of neuroscientific debates, there is a profound difference between simply using a device and incorporating it into one's body schema (Titchkosky et al. Reference Titchkosky, Healey and Michalko2019). For an ambulatory person to assess the testimony of a paraplegic or for a sighted person to assess the testimony of someone who is blind is not primarily an exercise in cognitive modeling. You can't model yourself into a different body schema. The neurological differences between one who is ambulatory vs. one who is non-ambulatory or one who is sighted vs. one who is blind are not made experientially available via projections or modeling, for it is both neurobiological and phenomenological differences at play.Footnote 22 Accordingly, assessing such testimony is always, in part, an exercise in trust. But that trust is not limited to taking another's testimony seriously, i.e., to how one judges testimonial evidence alone. There is also evidence in the sciences, social sciences, and humanities that can provide insights into not simply how those claims about lived experience ought to be judged, but also about the conditions under which and context through which those experiences bear out. The latter are considerations which help one not merely assess truth or falsity, but also come to understand the meaningfulness of the lived experience in question and the extent to which it pertains to a distinct experiential kind.

In short, the reasons we give for how and why we experience a given phenomenon as we do turn not merely on our ability to cognitively model things but also on how other people offer testimony concerning their own related experiences as well as the vast array of information available to understand the meaning of such claims.Footnote 23 To vary an example given above, experiencing the pain of a broken arm or the pain of a botched tonsillectomy does not entail knowing or understanding the meaning of living in chronic pain; nor does the reverse. Living in chronic pain does not entail knowing or understanding the pain of torture; nor does the reverse (cf. Klein Reference Klein2007). The fact that we use the word ‘pain’ for all the latter experiences is certainly part of the problem in this specific example, for the linguistic elasticity of certain concepts can easily mislead careful analysis, as Socrates (not just Wittgenstein) long ago lamented. But the limitations of various languages or particular concepts is not the primary problem at hand – the problem is how we treat the testimony of others concerning experiential kinds.

In sum, the reasons I might give for judging a shark attack as intuitively horrible are less valuable than the testimony of what it is like by someone who has been attacked by sharks and whose account of that attack further involves its relationship to their life afterwards. And just as I should not take one's claims concerning the intuitive horribleness of a shark attack due to mere extrapolation from non-shark-related pain, I should not take the testimony of a shark attack survivor as the final or total word on its experiential character, import, and impact. Evidence from other sources, including any number of humanistic, social scientific, and scientific approaches, is also requisite.

4. The disability paradox and epistemic injustice

All of this being said, the problem of skepticism remains. A paraplegic, as a result of a tragic accident, who reports it being the best thing that ever happened to them – or a good thing or even just something “not so bad” – might be/likely will be met with skepticism.Footnote 24 But to prima facie judge such an account as irrational or suspect begs the question yet again. Recall that the whole point of the thesis of personally transformative experience is that intuitions about such things are vacuous insofar as they track an experience that one has not only not undergone, but also through which one has not been transformed as a knower and, moreover, as a person. Intuitions are products not simply of epistemology, but also lived experience and one's life as a whole as shaped by social, cultural, historical, and political factors, and to take such vacuous intuitions seriously has not just epistemological, but also socio-political ramifications. How we treat the rules/norms by which we judge intuitions to have or not have purchase matters.

There are many reasons to fight against these tendencies, not least of which includes their contribution to various forms of epistemic injustice. There is a mountain of research on various experiences of paraplegia. If you are ambulatory and upon walking to the grocery store tomorrow, you are hit by a car and become paraplegic, you do not in that moment or the next day (or even in the next few months) become an expert on living with paraplegia.Footnote 25 To claim – for example, two weeks or even six months into one's experience – that being hit by that car is the worst thing everFootnote 26 and that that life is not worth living is a claim that should be assessed in light of the resources from people who have been paraplegic for years, including those with congenital forms of paraplegia. To downgrade the credibility of those who are paraplegic in light of one's fleeting intuition or all-too-narrow experience is a form of testimonial injustice and to further not engage the large body of existing knowledge concerning paraplegia is a form of hermeneutical injustice.

In light of my arguments here, the disability paradox raises the claim of “intuitive horribleness” from a run-of-the-mill philosophical charge to a question of testimonial and hermeneutical injustice. It is not just that different sets of epistemic resources are at play; it is also that available resources are willfully being ignored. By willfully ignoring them, one actively contributes to epistemic injustices against those for whom those epistemic resources are important. Imagine a convert to a new religion who judged that shift without spending any time talking with those of the same religion, without digging into relevant texts, including its core sacred text(s) and its tenets, and without participating in its core rituals.Footnote 27 If such a person espoused a view about that religion a number of months into their conversion – whether negative, positive, or somewhere in between – one would rightly question their epistemic standing because they not only failed to do the epistemic work necessary for their claims to meaningfully track the lived experiences and form of life, the experiential kinds, about which they are making a claim, but they ignored the hermeneutic resources at their disposal. Among its many issues, the shark problem relies upon the same moves as that misguided person.

One might object that a result of my account is that none of us can engage in any meaningful risk reasoning or decision-making about the future. The uptake of my argument, such a critic might argue, is that it is irrational to even try to avoid or pursue any event that will change your life. If becoming paraplegic doesn't qualify as a sharky problem, then what norms are at play to avoid accidents? Why do we even need things like crosswalks? This objection draws conclusions that I do not defend and which do not follow from the arguments presented here. I argued that Paul's claims concerning transformative experience turn upon the impact and quality of forms of life, not the what-it-is-like of various discrete events, whether unanesthetized amputation or what have you. I do think that one should in general avoid amputation, being hit by a bus, or being attacked by sharks. That is not the point. To think it is the point is to fall into the very cognitive trap against which I am arguing: a failure to appreciate the differences and nuances between the experientially discrete and the continuous, between the epistemically and personally transformative, and between the constituent and the constitutive.Footnote 28

To summarize, if one accepts the thesis of transformative experience, this implies a normative commitment; namely, that (a) one refrain from making categorical judgments about experiences that, for one, would be personally transformative – even if one takes various aspects of one's own experience to judge their onset, transition to, or various discrete, involved experiences to be horrible, and (b) one defers to, and learns from, those who have actually had such experiences and research that critically and seriously analyzes such experiences in order to assess judgments about them. Given the literature on epistemic injustice, this is especially important when the judgments concerning lived experience track that of a marginalized group (Sherman and Goguen Reference Sherman and Goguen2019).

5. Conclusion

I have argued that testimonial and hermeneutical injustice are baked into most deployments of the concept of intuitive horribleness, and that, even if one were to justify its use in select cases, it should be accompanied with prima facie suspicion. To go beyond the trappings of intuition requires work. Philosophically, socially, politically, legally, and so forth, there are high stakes with respect to whether or not we consider the events of “being attacked by sharks” and “undergoing an amputation” as instances of a unified experiential kind or, what's more, as cases that inform us about personally transformative experiences like becoming disabled. As I have argued, whatever said events have in common is beside the point of debates over transformative experience. Neither refers to forms of life; neither refers to that which would constitute a personally transformative experience. On the contrary, both fail to address the most relevant aspects of experience in which each result: becoming impaired and thereby experiencing disability. Becoming impaired and disabled in these ways relates to the experiences of actually existing people and communities – as well as a massive body of research spanning the social sciences and humanities in the interdisciplinary field of disability studies.

Testimony concerning experiences like amputation are not merely a question of the relationship between general experiences (like pain) or extrapolations thereof, but of how real, existing people undergo these specific experiences and how they take up them up as shaping their life and life projects.Footnote 29 The challenge of what Campbell and Mosquera (Reference Campbell and Mosquera2020) call the shark problem for transformative experience fails to appreciate the distinction between epistemically and personally transformative experiences, fails to take the role of temporality seriously, and fails to appreciate normative considerations involved in claims of intuitive horribleness.Footnote 30 Insofar as disability experiences are what L.A. Paul calls personally transformative experiences, experiences which one cannot evaluate and compare without having undergone oneself, then the shark problem and the disability paradox are less a problem and a paradox and, instead, simply more reasons to question doxastic attitudes and credences that relate to experiences one has never undergone.Footnote 31