1.1 Parenting Science

Parenting is a vital status in the life course with consequences for parents themselves, but parenting is also a job whose primary object of attention and action is the child. Human children do not and cannot grow up as solitary individuals. Parenting exerts direct effects on offspring through genetic endowment as well as the experiences parents afford their offspring. Those experiences are instantiated in parents’ cognitions and practices. Parenting also exerts indirect influences on offspring through parents’ relationships with each other and their connections to community and culture. Parenting is fundamental to the survival and success of the human species. Everyone who has ever lived has had parents, and the vast majority of adults in the world become parents. Indeed, each day approximately three quarters of a million adults around the world experience the joys and rewards as well as the challenges and heartaches of becoming a new parent. Emotions constitute an essential constituent of parenting (Dix, Reference Dix1991; Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Wallace, Laurent and Mayes2015). A flourishing science of parenting is enjoying special popularity today in the academy and in popular culture. In consequence, a surprising amount of solid science (contra untethered opinion) is accumulating about parenting and associated emotions and emotion regulation.

Emotions and emotion regulation are vital to parenting, and this chapter assesses central features of parenting through the lens of emotions and emotion regulation. In doing so, the chapter pursues the following course. Substantive topics include principles of parenting and emotion regulation, parenting effects in emotion regulation, determinants of emotion regulation in parents (and children), and supports for parent and child emotion regulation. First, however, the chapter deconstructs relations between emotions and emotion regulation in parenting. Reasons of space constrain a full accounting of parenting, and emotions and emotion regulation in parenting, and so the following exposition is illustrative rather than exhaustive (see Bornstein, Reference Bornstein, Bornstein, Leventhal and Lerner2015, Reference Bornstein and Cicchetti2016, Reference Bornstein2019a, for more detailed and comprehensive treatments).

1.2 Emotions and Emotion Regulation in Parenting

The intersection of parenting science and emotions encompasses parents’ emotionality, emotional expressiveness, emotion regulation, and emotion socialization that mold affective family patterns vital to children’s wholesome development. Emotions and emotion regulation in family life manifest in three ways: first in parents’ own emotions and emotion regulation as adults, second in parents’ emotions and emotion regulation in their parenting, and third in parents’ parenting children’s emotions and emotion regulation. These three topics guide the informational structure of this chapter. As to the first, for example, positive emotions buoy well-being and are associated with adjustment, serenity, meaningfulness, and satisfaction, whereas negative emotions undermine well-being and are associated with anxiety, stress, frustration, and anger (Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Supple, O’Brien, Calkins, Haltigan, Wong and Fortuna2015; Schiffrin et al., Reference Schiffrin, Rezendes and Nelson2010). As to the second, for example, people may become parents because of the expectation that parenting will be emotionally rewarding (Langdridge et al., Reference Langdridge, Sheeran and Connolly2005), and parental global emotion regulation is associated with adaptive parenting (Crandall et al., Reference Crandall, Deater-Deckard and Riley2015; Shaffer & Obradović, Reference Shaffer and Obradović2017). As to the third, children reared by parents with good emotion regulation skills are better able to cope with their own emotions, develop more secure attachments, and fare better in many domains of development (Buckholdt et al., Reference Buckholdt, Parra and Jobe-Shields2014; Han et al., Reference Han, Qian, Gao and Dong2015; Sarıtaş et al., Reference Saritaş, Grusec and Gençöz2013).

These three main issues – parenting, emotion regulation, and emotion regulation in children – are related to one another. The barebones version of a “standard model” of mediation in parenting science asserts that parenting cognitions generate, prompt, or direct parenting practices that ultimately affect child development (Figure 1.1; Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Putnick and Esposito2017). A modified standard model as applied to emotion regulation in parenting would contend that parenting emotion regulation generates parenting cognitions/practices which in turn influence child emotional regulation (Figure 1.2; Bariola et al., Reference Bariola, Gullone and Hughes2011; Crandall et al., Reference Crandall, Deater-Deckard and Riley2015; Peris & Miklowitz, Reference Peris and Miklowitz2015; Rueger et al., Reference Rueger, Katz, Risser and Lovejoy2011).

Figure 1.1 Generic mediation model of parenting

Figure 1.2 Parenting and emotions mediation

Pairwise components of this mediational model involving parenting, parenting emotion regulation, and emotion regulation in children have been submitted to cumulative meta-analyses. Zimmer-Gembeck et al. (Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022) reviewed 53 studies published between 2000 and 2020 to quantify associations of parents’ emotion regulation skills (e.g. ability to regulate negative mood or rely on cognitive reappraisal to regulate emotions) with positive and negative parenting practices (e.g. warmth versus hostility) and children’s emotion regulation skills (e.g. difficulties with emotion regulation, internalizing symptoms, and externalizing behaviors). Several pertinent results emerged between parents’ emotion regulation skills and their parenting practices. First, parents with more emotion regulation skills express more positive parenting practices. Second, parents with more emotion regulation skills express fewer negative parenting practices. Third, parents with more emotion regulation difficulties express fewer positive parenting practices. Fourth, parents with more emotion regulation difficulties express more negative parenting practices. In brief, parents with better emotion regulation skills or fewer difficulties express more positive parenting practices. Likewise, several pertinent results emerged between parents’ emotion regulation skills and their children’s adjustment. First, parents with more emotion regulation skills have children with fewer internalizing symptoms. Second, parents with more emotion regulation skills have children with more emotion regulation skills. Third, parents with more emotion regulation difficulties have children with more internalizing symptoms. Fourth, parents with more emotion regulation difficulties have children with more externalizing behaviors. Fifth, parents with more emotion regulation difficulties have children with poorer emotion regulation skills. In brief, parents who report more emotion regulation skills have children with more emotion regulation skills, fewer conduct problems, more prosocial behaviors with peers, and fewer internalizing symptoms.

Notably, this meta-analysis supports several significant associations among constituents of the mediation model, but many were small in effect size and not all possible associations were found (e.g. no significant associations emerged between parents’ emotion regulation skills with children’s externalizing behaviors). Furthermore, only cross-sectional correlations were meta-analyzed (i.e. parents’ influence on and socialization of their children is assumed when children could promote parents’ emotions and emotion regulation).

In practice, a more realistic picture of mediation in parenting and emotions would be complexified by several factors:

1. Likely valid mediation is a multi-step process so that child emotions/behavior → parent physiology/cognition → parent emotion → parent emotion regulation → parent cognition and/or practice → child emotion regulation or adjustment.

2. Associations between parental beliefs and behaviors have generated a mixed literature (Cote & Bornstein, Reference Cote and Bornstein2000; Okagaki & Bingham, Reference Okagaki, Bingham, Luster and Okagaki2005): less evidence exists for relations between very general beliefs and behaviors, and stronger associations have been documented between conceptually corresponding specific beliefs and specific behaviors (Huang et al., Reference Huang, O’Brien Caughy, Genevro and Miller2005).

3. Individual differences in parenting are pervasive. Variation in mothers’ subjective emotions across occasions (sampled throughout several days) predict motivation to engage or disengage with their infants as well as actual engagement or disengagement (Hajal et al., Reference Hajal, Teti, Cole and Ram2019).

4. Moderators may change the relation between elements in the mediation chain in so-called moderated mediation (Figure 1.3). Of a raft of potential moderators in Zimmer-Gembeck et al. (Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022), measurement, child age, and participant risk status moderated effect sizes of associations of parents’ emotions with their positive or negative parenting and children’s emotions.

Figure 1.3 Moderated mediation in parenting and emotions

1.3 Principles of Parenting and Emotion Regulation

Parenting is instantiated in a plethora of cognitions and practices. Despite this diversity, classical authorities, including psychoanalysts, personality theorists, ethologists, and attachment theorists, historically conceptualized caregiving as trait-like and unidimensional, often denoted as “good,” “sensitive,” or the like (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978; Brody & Axelrad, Reference Brody and Axelrad1978; Mahler et al., Reference Mahler, Pine and Bergman1975; Winnicott, 1948/Reference Winnicott1975). Alternatively, child-rearing (including emotions and emotion regulation) reflects multiple constituents and interactions of parent, child, and context, and parents naturally hold a range of diverse emotion regulation cognitions and engage in a range of diverse emotion regulation practices and so do not only or necessarily believe or behave in uniform trait-like ways. Rather than employing a uniform style, parents flexibly change in parenting cognitions and practices as children age and with children of different temperaments, vary their approaches to emotion regulation depending on children’s happy or sad or angry demeanor, and differ in their emotion regulation responses to varying situational constraints such as whether they are in public or in private. On this view, the contents of parent–child emotion regulation cognitions and practices are dynamic and varied (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein and Bornstein2002, Reference Bornstein, Renninger, Sigel, Damon and Lerner2006). In essence, parenting generally, and emotions and emotion regulation in parenting particularly, are multidimensional, modular, and specific. This perspective has two significant implications: first, it supports identification and empirical focus on independent emotions and emotion regulation cognitions and practices, and second, it implies that specific emotion and emotion regulation parenting cognitions and practices link to the expression of specific domains of children’s emotion regulation (see Section 1.4).

1.3.1 Parenting Cognitions and Emotion Regulation

Multidimensional, modular, and specific parenting cognitions may be classified by functions, types, and substantive topics. First, parenting cognitions serve many functions: They affect parents’ sense of self, help to organize parenting, and mediate the effectiveness of parenting. With respect to emotion regulation, cognitions contribute to how and how much time, effort, and energy parents expend in emotion regulation for themselves and their children and help to form the framework in which parents perceive, interpret, and guide their children’s emotion regulation. Next, parenting cognitions come in a wide variety of types, prominently goals, attitudes, expectations, perceptions, attributions, and actual knowledge of child-rearing and child development, all of which have instantiations in emotion regulation. For example, some parents’ goals for their own parenting and for their children may be universal; after all parents everywhere presumably want physical health, academic achievement, social adjustment, economic security, as well as mature and stable emotion regulation for their children (however those goals are instantiated in different cultures, discussed later). African American, Dominican immigrant, and Mexican immigrant mothers in the United States all deem a common set of emotion regulation qualities (e.g. proper demeanor) desirable in young children (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Tamis-LeMonda, Godfrey, Hunter and Yoshikawa2012). Other goals may be unique to specific groups. For example, some societies stress the development of emotion regulation through independence, self-reliance, and individual achievement in children, whereas other societies emphasize deriving emotion regulation through interdependence, cooperation, and collaboration in the group or society (Chen, Reference Chen2023). Last, substantive topics in parenting cognitions include cognitions about parenthood generally, about parents’ own parenting, about childhood generally, and about parents’ own child(ren). All can refer to emotions and emotion regulation.

1.3.2 Parenting Practices and Emotion Regulation

Parents’ practices constitute the largest measure of children’s worldly experience. Like cognitions, parenting practices are multidimensional, modular, and specific, and parenting practices themselves may be classified into types, characteristics, and functions. First, a common core of types of parenting practices includes nurturant, physical, social, didactic, language, and material (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein, Bornstein, Leventhal and Lerner2015, Reference Bornstein2019a; for other componential systems, see Bradley & Caldwell, Reference Bradley and Caldwell1995; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Johnson and Snyder2005). For example, language use in parenting is fundamental to child development and to the parent–child bond, and language is a principal mechanism used by parents to help regulate their children’s emotions (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Criss, Silk and Houltberg2017); language also helps children regulate their own emotions (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Armstrong, Pemberton, Calkins and Bell2010; Day & Smith, Reference Day and Smith2013). Second, prominent characteristics of parenting practices include differentiating obligatory versus discretionary, active versus passive forms of interaction, and the prominence of different parenting practices. Last, there is initial asymmetry in parent and child contributions to emotion regulation practices in that responsibility for emotion regulation early in development appears to lie unambiguously with parents, but children play more anticipatory roles as they develop. Functions of parenting practices are elaborated in Section 1.4.

1.3.3 Emotion Regulation Cognitions and Practices: Common Features

Meaningful parenting cognitions and practices meet several psychometric criteria. One has to do with variation. Parents vary in terms of how they express cognitions, how often and long they engage in practices, and how they interpret and invest meaning in both (Calkins, Reference Calkins1994; Diaz & Eisenberg, Reference Diaz and Eisenberg2015). For example, considerable individual variability characterizes developmental trajectories of emotion regulation in children across the ages of 4–7 years (Blandon et al., Reference Blandon, Calkins, Keane and O’Brien2008). A second psychometric criterion has to do with developmental stability (consistency in individual parents over time) and a third with continuity (consistency in group mean level over time; Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Putnick and Esposito2017). For example, the development of emotion regulation is dynamic on three levels: rapid changes in spatial and temporal dynamics across multimodal systems underlying emotion regulation, slowly emerging changes in emotion regulation over periods of time and development, and changes in emotion regulation across contexts (Dennis-Tiwary, Reference Dennis-Tiwary2019). A fourth psychometric characteristic of parenting concerns covariation among parenting cognitions and among parenting practices. Particular cognitions and particular practices are free to vary with different children, at different times, in different situations, and so forth (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein, Bornstein, Leventhal and Lerner2015).

1.4 Parenting Effects in Emotion Regulation

Parenting has twofold significance: parenting is a salient phase of adult life, and parenting is an instrumental activity with respect to offspring. In brief, parenting is for parents, and parenting is for children. In consequence, effects of parenting on children and child development constitute critical desiderata. Here the distinction between direct and indirect effects of parenting is meaningful as are several operational principles in parenting effects, notably specificity, timing, thematicity, moderation, meaning, transaction, and attunement. Each is addressed briefly with examples from emotions and emotion regulation.

1.4.1 Direct and Indirect Effects of Parenting and Emotion Regulation

Direct influences of parent cognitions and practices reflect, for example, scaffolding, conditioning, reinforcement, and modeling; indirect effects include, for example, opportunity structures parents provide (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein, Wilcox and Kline2013a) and relationships parents or family members have with one another that spill over to children (McHale & Sirotkin, Reference McHale, Sirotkin and Bornstein2019). The validity of parenting effects is supported with correlational and experimental evidence. Children reared by parents with good emotion regulation skills regulate their own emotions better (Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Su, Calkins, O’Brien and Supple2017), and parents’ positive emotional expressions toward their children relate to children’s later more positive peer relationships (Paley et al., Reference Paley, Conger and Harold2000). Several pathways by which parenting-related emotions and their regulation likely shape child development have been hypothesized (Leerkes & Augustine, Reference Leerkes, Augustine and Bornstein2019). First, parenting-related emotions and regulation could relate to children’s emotions or emotion regulation through synchronization of mutual biological rhythms (Feldman, Reference Feldman2007; Moore, Reference Moore2009). Second, as spelled out in the mediation model, parenting-related emotions and regulation could link to child outcomes through parenting cognitions or practices. Well-regulated or child-oriented parent emotions could engender more positive parenting, which in turn shapes adaptive emotions and emotion regulation in children. Third, as spelled out in the moderated-mediation model, different parenting-related emotion or regulation skills could alter how parenting practices relate to child emotions and emotion regulation (Darling & Steinberg, Reference Darling and Steinberg1993; Grusec & Goodnow, Reference Grusec and Goodnow1994). Parenting practices embedded in positive, contra negative, parental emotions render children more open to parental socialization.

Most studies of parent–child relationships have employed correlational designs: put simply, in such study designs parents who do more (or less) of something (emotion regulation) have children who do more (or less) of a related something (emotion regulation). For example, mother–child interactions involving positive emotions correlate with greater effortful control and compliance to parental requests (Kochanska & Aksan, Reference Kochanska and Aksan1995), greater social competence (Denham et al., Reference Denham, Mitchell-Copeland, Strandberg, Auerbach and Blair1997), and fewer behavior problems (McCoy & Raver, Reference McCoy and Raver2011) in children. However, the sizes and directions of zero-order correlations between parent cognitions or practices and child characteristics vary depending on which parent and child variables are measured (echoing the cognition-practice issue), the way the two are measured, the length of time between parent predictive and child outcome measurements, what kind of analyses are conducted, which types of children or families living in which circumstances are studied, and whether potential confounders are controlled (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein2013b). It may be true that parents influence children, but correlation does not prove causation, the arrows of influence in a simple association may run in either or both directions (viz., that parents influence children and children influence parents), and associations between parents’ child-rearing practices and child characteristics could arise from shared third familial (parents and their children share genes) or extrafamilial factors (parents and their children share ethnic group or socioeconomic status membership). To obviate these critiques of parenting effects as mere epiphenomena, some more determinative correlational designs have included biological-adoptive comparisons (which separate the effects of environment and genetics, discussed later).

Experimental designs attempt to confirm causal relations between parenting and child development. Experiments in which parents are assigned randomly to treatment versus control groups with resulting changes in the beliefs or behaviors (e.g. emotion regulation) of the parents (and their otherwise untreated children) in the treatment relative to the control group make stronger statements about parenting effects. This literature in emotion regulation boasts natural, designed, and intervention experiments. Studies of children whose genetics differ from those of their parents provide naturally occurring means of evaluating the impacts of parenting experiences vis-à-vis hereditary endowment on child development. In adoption experiments, one group of children might share genes and environment with biological parents, another genes but not environment with biological parents, and still another environment but not genes with adoptive parents (Asbury et al., Reference Asbury, Cross and Waggenspack2003; Muller et al., Reference Muller, Vascotto, Konanur and Rosenkranz2013). Designed experiments that randomly assign human families to treatment versus control groups and intervene with the parents but do not simultaneously treat the children have shown that, when the treatment alters parental practices toward children in specified ways, children change correspondingly (Weisman et al., Reference Weisman, Zagoory-Sharon and Feldman2012). Finally, interventions with parents have two interpretations. Interventions are practical guides to improve parenting clinically and to inform more effective policy (see Section 1.6). However, intervention trials are also readily interpreted as experimental manipulations that test parenting effects (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Dia, Kotler, Lansford, Raghavan and Mitter2022a; Lunkenheimer et al., Reference Lunkenheimer, Dishion, Shaw, Connell, Gardner, Wilson and Skuban2008).

1.4.2 Specificity, Timing, Thematicity, Moderation, Meaning, Transaction, and Attunement

A common assumption in parenting study is that the overall level of parenting (involvement, stimulation, what have you) affects the child’s overall level of development. By contrast, increasing evidence suggests that more sophisticated and differentiated processes govern parenting effects. The specificity principle states that specific cognitions and practices on the part of specific parents at specific times exert specific effects in specific children in specific ways (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein and Bornstein2002, Reference Bornstein, Bornstein, Leventhal and Lerner2015, Reference Bornstein2019b). For example, mothers’ emotional happiness during interactions with their children predicts fewer behavior problems in children over time but only in children already low in behavior problems (Denham et al., Reference Denham, Workman, Cole, Weissbrod, Kendziora and Zahn-Waxler2000). Parents’ self-reported expressions of negative emotions are associated with their preschoolers’ use of more maladaptive emotion regulation behaviors, higher negative emotionality, and higher externalizing symptoms, but are unrelated to a physiological measure of children’s adaptive emotion regulation or observed measures of children’s emotion knowledge (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Wang and Liu2017; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, O’Brien, Calkins, Leerkes, Marcovitch and Blankson2012; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Wang and Liu2017), and meta-analysis of studies focused on parents’ negative emotional expressions found that sadness and crying, but not anger and hostility, are associated with deficits in emotion understanding particularly among adolescents and young adults (Halberstadt & Eaton, Reference Halberstadt and Eaton2002). Of course, specificity also obtains in the first phases of mediation: parent-oriented anger may promote parent–child conflict, whereas parent-oriented sadness may promote parental withdrawal from the child (Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004). In brief, to detect regular relations between antecedents in parenting on the one hand and outcomes in child characteristics on the other calls for specificity in the combinations of independent and dependent variables.

Related to specificity and a key consideration in parenting effects is timing. A contemporary effects model spotlights the part played by experiences that occur only at a specific time in the life cycle. For example, some early experiences are thought to persist despite later experiences, and some later experiences are thought to replace effects of earlier experiences. Still other developmental effects reflect consistency in experiences that recur. A cumulative effects model asserts that meaningful enduring effects are structured by experiences that repeat or aggregate. Related to such cumulative effects, the same parenting effect may be conveyed consistently in different contexts via different channels. Through such thematicity, seemingly diverse parenting messages work in concert. For example, mothers and fathers may model a given emotion, teach children about that emotion, and place children in contexts that elicit that same emotion (Coltrane, Reference Coltrane2000; Schuette & Killen, Reference Schuette and Killen2009). In brief, a given experience (say an emotion) may exert an effect on development early or late in life or it may need to persist to be meaningful and lasting.

Further related to specificity and as demonstrated in moderated mediation, parenting effects may be moderated by multiple factors. For example, mothers exhibit more supportive parenting behaviors in interactions with their children when they experience relatively higher levels of positive emotions and lower levels of negative emotions (Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004). Maternal emotional stability is strongly associated with overprotective parenting with shier children (Coplan et al., Reference Coplan, Reichel and Rowan2009). Higher levels of paternal emotional stability are associated with more positive parenting when adolescents are high in emotional stability (Prinzie et al., Reference Prinzie, Deković, van den Akker, de Haan, Stoltz and Jolijn Hendriks2012).

The same parenting cognition or practice can have the same or different meaning, just as different parenting cognitions or practices can have the same or different meanings (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein1995, Reference Bornstein2013b; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Huang, Garland, McCabe, Yeh and Hough2006). For example, the same discrete emotion can mean different things depending on the nature of the underlying concern (Dix et al., Reference Dix, Gershoff, Meunier and Miller2004). In turn, meaning can moderate linkages between emotions and behaviors. In an example in Leerkes and Augustine (Reference Leerkes, Augustine and Bornstein2019), a parent might be angry with a child for acting out and so provoke discipline, or a parent might be angry in the interests of a child and so evoke comforting. Likewise, a parent’s intensifying positive emotions to continue engaging positively with a child may be adaptive, whereas a parent’s intensifying positive emotions to eschew a developing problem with a child may be maladaptive (Martini & Busseri, Reference Martini and Busseri2012).

It is easy to assume that parents are responsible for child development, and in many ways they are (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978); however, it is also the case that children elicit as well as interpret parenting (Bell, Reference Bell1968). Children influence which experiences they are exposed to, and they appraise those experiences and so (in some degree) determine how their experiences affect them (Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Criss, Laird, Shaw, Pettit, Bates and Dodge2011). On elicitation, a parent’s displaying sensitivity in response to a child’s emotional signals provides external regulation and supports development of the child’s emotion regulation skills (Bernier et al., Reference Bernier, Carlson and Whipple2010; Ispa et al., Reference Ispa, Su-Russel, Palermo and Carlo2017). On interpretation, a given child may feel frightened by a parent’s emotional outburst, which over time undermines the child’s confidence in that parent’s capacity to keep the child safe (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Reference Lyons-Ruth, Jacobvitz, Cassidy and Shaver2016). Together, parent and child effects lead to transactions which acknowledge that characteristics of the individual shape their experiences, whereas, reciprocally, experiences shape characteristics of the individual through time (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein and Sameroff2009; Lerner, Reference Lerner2018). Child effects on parent are in play and coexist with parent effects on child.

Attunement expresses the dynamic mutual adaptation of partners in a dyad. Attunement is a multilevel phenomenon with correspondences in hormones, the autonomic and central nervous systems, as well as in affective, cognitive, and behavioral domains (Bornstein, Reference Bornstein, Legerstee, Haley and Bornstein2013c). For example, positive emotional expressiveness in parents correlates robustly with positive emotional expressiveness in children (Halberstadt & Eaton, Reference Halberstadt and Eaton2002), and correspondingly maternal negative affect co-occurs with child negative affect (attunement in which attachment insecurity is associated with toddlers’ elevated externalizing symptoms; Lindsey & Caldera, Reference Lindsey and Caldera2015; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Clements and Crnic2011). Notably, emotional attunement has consequences of its own. For example, shared emotions are linked with mothers’ and adolescents’ perceptions of better relationship quality (Lougheed & Hollenstein, Reference Lougheed and Hollenstein2016).

1.5 Determinants of Emotion Regulation in Parents (and Children)

With parenting effects so demonstratively significant for child development generally, and emotion regulation in parents and children specifically, it is important to ask what factors contribute to emotions and emotion regulation in parenting. To fully understand and appreciate parenting and its effects it is desirable to evaluate the many determinants that shape it. Consistent with a relational developmental systems bioecological orientation (Lerner, Reference Lerner2018), the vast potential array of causes can be grouped in three domains: the parent, the child, and the context. Not all constituents of each domain can be discussed, of course, but a representative sampling will suffice to convey that the origins of individual variation in caregiving emotion cognitions or practices are complex and multiply determined.

1.5.1 Parent

Parenting blends intuition and tuition, the biological and the psychological. Certain characteristics of parenting may be wired into our biological makeup (Broderick & Neiderhiser, Reference Broderick, Neiderhiser and Bornstein2019; Feldman, Reference Feldman and Bornstein2019; Stark et al., Reference Stark, Stein, Young, Parsons, Kringelbach and Bornstein2019). For example, positive emotionality is influenced by genetics (Avinun & Knafo, Reference Avinun and Knafo2014; Broderick & Neiderhiser, Reference Broderick, Neiderhiser and Bornstein2019; Klahr & Burt, Reference Klahr and Burt2014), and more responsive/sensitive parents demonstrate distinct patterns of emotion-related hormonal and neural activation (Feldman, Reference Feldman and Bornstein2019; Rutherford et al., Reference Rutherford, Wallace, Laurent and Mayes2015; Stark et al., Reference Stark, Stein, Young, Parsons, Kringelbach and Bornstein2019). Additionally, human beings appear to possess some intuitive knowledge about parenting (Papoušek & Papoušek, Reference Papoušek, Papoušek and Bornstein2002). Other sociodemographic characteristics of parents likewise shape emotion regulation. For example, the age of the parent is a factor: on the one hand, delayed parenthood is associated with emotional benefits, as parents who are relatively older report relatively greater well-being (Luhmann et al., Reference Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid and Lucas2012); feeling more competent and less stressed, depressed, and lonely (Cowan & Cowan, Reference Cowan and Cowan1992; Frankel & Wise, Reference Frankel and Wise1982; Garrison et al., Reference Garrison, Blsalock, Zarski and Merritt1997; Mirowsky & Ross, Reference Mirowsky and Ross2002); and experience fewer negatives in parenting (particularly negative emotions, financial strain, and tense partner relationships). On the other hand, adolescent mothers are more likely to parent in poverty, parent solo, have lower educational attainment, and lack resources compared to adult mothers (Easterbrooks et al., Reference Easterbrooks, Katze, Menon and Bornstein2019). These risk factors increase the likelihood of parenting difficulties that can lead to compromised developmental outcomes in children, including difficulties in emotional regulation (Hans & Thullen, Reference Hans, Thullen and Zeanah2009; Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Honorado and Bush2007; Schatz et al., Reference Schatz, Smith, Borkowski, Whitman and Keogh2008). Gender is another instrumental sociodemographic factor. Stereotypically, femininity is characterized by emotionality and nurturance, whereas masculinity is characterized by independence and aggressiveness (Eagly et al., Reference Eagly, Wood, Diekman, Eckes and Trautner2000). Maternal emotional stability is linked to more positive, responsive, and sensitive parenting of infants relative to paternal emotional stability (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange and Martel2004). Yet, emotionally stable mothers and fathers alike are more affectively positive and sensitive with their infants (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Crnic and Woodworth1995). Parity is a third sociodemographic factor. Primiparous mothers demonstrate elevated general worry and cortisol response, reflecting stress reactivity, during interactions with their toddlers relative to multiparous mothers (Kalomiris & Kiel, Reference Kalomiris and Kiel2016).

Perceptual and cognitive processes also play central roles in the activation of parenting-related emotions. Mothers’ accurate cue detection and feelings of efficacy are associated with greater sensitivity in response to infant distress especially among mothers who also report high empathy (Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Crockenberg and Burrous2004). Parents who lack awareness of their emotions or struggle to regulate their emotions likely find it difficult to prioritize child-oriented goals in the moment and to engage in effortful behaviors that are well matched to their parenting goals. Poorly regulated emotions also may bias how parents appraise their child’s behaviors or their own parent–child interactions. In this connection, parents’ own developmental history, particularly the nature of parenting they experienced in childhood and so formulated their internal working model of relationships, relates to many forms of parenting-related emotions. For example, mothers’ secure attachment representations predict greater parenting-related joy and pleasure with toddlers (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Belsky, Aber and Phelps1999) as well as empathy with infants and school-age children (Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Supple, O’Brien, Calkins, Haltigan, Wong and Fortuna2015; Stern et al., Reference Stern, Borelli and Smiley2015); insecure representations predict observed angry/intrusive parenting with toddlers (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Gunnar and Tanaka2004), presumably reflecting parent-oriented negative affect; and parents high in attachment avoidance report lower levels of positive emotions during caregiving compared to their other daily activities (Nelson-Coffey et al., Reference Nelson-Coffey, Borelli and River2017). Generally, negative experiences in parents’ family of origin consistently predict parents’ negative parent-oriented affect and poorer emotion regulation during emotionally evocative parent–child interactions. Mothers with a history of family abuse or violence display greater hostility during interactions with their 4- to 6-year-olds (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, DeOliveira, Wolfe, Evans and Hartwick2012).

Among all personological factors potentially associated with emotional regulation in parents and children, personality may enjoy the longest history and most robust relations. Theorizing in this domain derives from psychoanalytic scholars who originally focused on pathological aspects of parental character and the ways in which they might contribute to child psychopathology (Freud, 1955/Reference Freud, Anthony and Benedek1970; Spitz, 1965/Reference Spitz, Anthony and Benedek1970; Winnicott, 1948/Reference Winnicott1975) on the hypothesis that, if parents’ emotional needs had not been met during their own childhoods, their unmet needs would be reflected in parents’ own problematic parenting (Cohler & Paul, Reference Cohler, Paul and Bornstein2019).

Psychologically, emotion regulation is affected by several characteristics, personality and mental functions prominent among them. Emotion is central to personality, and specifically the Big Five personality factors (Caspi & Shiner, Reference Caspi, Shiner, Damon and Eisenberg2006), which traditionally include extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience, relate to emotion regulation in parents and have multiple implications for child development. On the positive emotional side, extraversion qua positive affectivity is associated with emotionally engaged, responsive, sensitive, and stimulating parenting. Israeli men scoring high on extraversion manifest more positive affect and are more involved in father-child play and teaching when interacting with their 9-month-olds than men scoring low on extraversion (Levy-Shiff & Israelashvilli, Reference Levy-Shiff and Israelashvili1988). Agreeableness reflects an individual’s motives to maintain positive social relationships and is related to the regulation of emotions during social interactions (Tobin et al., Reference Tobin, Graziano, Vanman and Tassinary2000). More agreeable parents are less likely to attribute negative intentions to their young children when they misbehave (Bugental & Corpuz, Reference Bugental, Corpuz and Bornstein2019). On the negative emotional side, neuroticism, which is characterized by heightened negative affect and mood disorders, such as depression, predicts low parental sensitivity and warmth and high discipline and (even) child maltreatment (Dix & Moed, Reference Dix, Moed and Bornstein2019; Prinzie et al., Reference Prinzie, de Haan, Belsky and Bornstein2019). Parents high in neuroticism tend to be reactive to emotional stress and easily emotionally distressed, prone to experience irritability and hostility (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Roberts and Shiner2005; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1993), provide lower levels of support to their children, and lack organization, consistency, and predictability. For example, parents’ high neuroticism is associated with more negative emotional interactions and lower sensitivity to toddlers (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Crnic and Woodworth1995). Depression consistently relates to less-positive emotional quality in parent–child interactions (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare and Neuman2000).

Emotional stability is a pervasive personality characteristic with a double-barreled meaning. Emotional stability is linked to positive maternal affect with children (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Aksan and Nichols2003). More emotionally stable parents are less prone to frustration, distress, irritation, and anger, which often result in harsh discipline, and approach children in ways that are less likely to initiate or escalate conflictual interactions. More emotionally stable parents are more sensitive, provide more structure, and are more inclined to support their children’s striving toward autonomy than less emotionally stable parents (Ellenbogen & Hodgins, Reference Ellenbogen and Hodgins2004; Mangelsdorf et al., Reference Mangelsdorf, McHale, Diener, Goldstein and Lehn2000; McCabe, Reference McCabe2014). More emotionally stable mothers follow their baby’s signals in ways that facilitate the baby’s self-regulation (Fish & Stifter, Reference Fish and Stifter1993).

Emotional instability, by contrast, is associated with unpredictable, inconsistent parenting. Emotionally unstable parents attribute negative intentions to their children when they misbehave, which can engender harsh parenting (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Hahn and Haynes2011), and they distance themselves from their children, thereby failing to provide structure and guidance (Belsky & Jaffee, Reference Belsky, Jaffee, Cicchetti and Cohen2006; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Kochanska and Ready2000). Negative emotionality tends to undermine parents’ ability to initiate and maintain positive affective, sensitive, and supportive interactions with their children and limits parents’ ability and willingness to respond adequately to their children’s signals. In a Dutch sample with 17-month-old boys paternal and maternal emotional instability was associated with lack of structure in parenting (Verhoeven et al., Reference Verhoeven, Junger, Van Aken, Deković and Van Aken2007).

The barebones mediation analysis of parenting cognitions → practices → child outcomes was introduced previously and complicating conditions hinted at. One such complication is that emotions mediate the effect of personality on parenting. A longitudinal study revealed that mothers’ personality characteristics were associated with their positive emotional expressions, which in turn related to more maternal positive emotionality observed during interactions with toddlers (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Spinrad, Eisenberg, Gaertner, Popp and Maxon2007). With respect to practices, warm parenting gives children the sense that they are respected and loved and strengthens their motivation to obey and cooperate with their parents (Grusec et al., Reference Grusec, Goodnow and Kuczynski2000). Meta-analysis reveals a significant association between emotional stability and warmth (McCabe, Reference McCabe2014; Prinzie et al., Reference Prinzie, Stams, Deković, Reijntjes and Belsky2009). Parents who manifest higher levels of emotional stability engage in more warm parenting; however, moderator analyses reveal that the personality-warmth relation varies by parent and child age. The younger the parent and child, the stronger the relation between emotional stability and warmth.

1.5.2 Child

Actual or perceived characteristics of children also contribute to emotions in parents and parenting emotion regulation. Children’s characteristics as well as their behaviors regularly elicit positive emotions of pride, joy, and love but also negative emotions of embarrassment, anger, and sadness. For example, parents report positive child-oriented emotions if their children are well regulated and high in positive emotionality (Cole et al., Reference Cole, LeDonne and Tan2013; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange and Martel2004). However, children’s misbehavior or crying generates authoritarian parenting, anger, and in some cases mistreatment (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Eisenberg, Valiente and Wang2011; Lorber et al., Reference Lorber, O’Leary and Smith Slep2011). Children’s own emotion regulation varies with their development, and parents’ emotions and emotion regulation can vary with their child’s because certain stages of development, such as the “terrible twos” and parent–child conflicts that sometimes accompany adolescence, are emotionally challenging for parents. In infancy, children rely on caregivers for emotion regulation (Bernier et al., Reference Bernier, Carlson and Whipple2010; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004), but toddlers seek increased autonomy and start to develop internal emotion-regulation skills to appropriately modulate the intensity and duration of emotion expressions to function effectively in an environment (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad, Valiente, Shigemasu, Kuwano, Sato and Matsuzawa2018; Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Crnic and Baker2006). Other child characteristics likewise moderate parent and child emotion regulation and the parent–child relationship as, for example, temperament (especially difficulty), disability, and developmental disorders (Kiff et al., Reference Kiff, Lengua and Zalewski2011). So-called difficult child behaviors (including crying and misbehavior) are linked with parents’ reports of negative, parent-oriented emotions and physiological arousal (Del Vecchio et al., Reference Del Vecchio, Lorber, Slep, Malik, Heyman and Foran2016; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Gedaly, Su, Balter and Tamis-LeMonda2016; Lorber & O’Leary, Reference Lorber and O’Leary2005).

1.5.3 Context

Finally, both acute event-specific and chronic trait-like contextual characteristics moderate emotion regulation in parenting. Regarding the first, situational parenting-related emotions, such as those experienced while interacting with one’s child (e.g. irritation during a discipline encounter), when exposed to parenting-relevant stimuli (e.g. empathy when listening to audio recordings of infant crying), or in response to prior child behavior or parent–child interaction (e.g. embarrassment when reflecting on an earlier encounter) shape emotional arousal and regulation (e.g. Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Kushlev, English, Dunn and Lyubomirsky2013; Nelson-Coffey et al., Reference Nelson-Coffey, Borelli and River2017). More generally, parents report more positive emotions throughout the day compared to nonparents (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Kushlev, English, Dunn and Lyubomirsky2013) and specifically when they spend time with their children compared to their other daily activities (Musick et al., Reference Musick, Meier and Flood2016; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Kushlev, English, Dunn and Lyubomirsky2013; Nelson-Coffey et al., Reference Nelson-Coffey, Borelli and River2017). Relational assets like positive marital relationship experiences and social and material supports can boost parents’ positive emotions (putatively by reducing stress and strain; Leerkes & Crockenberg, Reference Leerkes and Crockenberg2006), in contrast to ecological and life stresses associated with economic, marital, social, and mental health domains, which tend to undermine parental emotional well-being (Newland, Reference Newland2014). For example, low-socioeconomic status parents likely experience reduced emotional well-being in part due to financial hardship and associated elevated stress. Human beings acquire important knowledge of what it means to parent children through generational, social, and cultural images of parenting, children, and family life, knowledge that plays a significant role in helping people formulate their parenting cognitions and guide their parenting practices. On a larger contextual scale, ethnicities and cultures differ in their acceptability and expression of positive and negative emotions related to emotion socialization goals, and so vary in how and when parents display or encourage emotion regulation (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Leerkes, Coard, Supple and Calkins2017).

Overall, the sizes of reported parenting effects reflect the fact that parenting is a complex multivariate system. Parenting effects are also conditional and not absolute (i.e. true for all parents and for all children under all conditions). In probabilistic relational developmental systems (like that between parent and child), it is unlikely that any single factor accounts for substantial amounts of variation in parenting effects. More complex conceptualizations that incorporate larger numbers of influential variables tend to explain parenting effects better than simpler ones with fewer variables. These considerations also play into the design, implementation, and scaling of parenting supports (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Rothenberg, Bizzego, Bradley, Deater-Deckard, Esposito, Lansford, Putnick and Zietz2022b).

1.6 Supports for Parent and Child Emotion Regulation

Society at large is witnessing the emergence of striking permutations in parenthood and in constellations of family structures that have plunged the family generally, and parenthood specifically, into a flux of novel emotions (Ganong et al., Reference Ganong, Coleman, Russell, Bornstein, Leventhal and Lerner2015). Because many society-wide developments exert debilitative influences on parenthood, on parenting, and, consequently, on children and their development, many parents need assistance to identify and implement effective strategies to optimize emotion regulation in child-rearing. Parenting conjures many positive emotions, such as intimacy, nurturance, and rewards, to be embraced and enriched, but parenting is also encumbered with negative emotions, such as frustration, anger, and harshness, to be eschewed and overcome. Upregulation of positive emotions can be promoted through openness to new knowledge, skills, and relationships, and downregulation of negative emotions can be achieved through physiological processes, behavioral strategies, and cognitive reframing (Fredrickson, Reference Fredrickson2013). Parents are usually the most invested, consistent, and caring people in the lives of their children, so providing parents with knowledge, skills, and supports will help them parent in the emotion realm more positively generally and promote their own and their children’s emotion regulation specifically.

It is a sad fact of everyday life that parenting children does not always go well or right. Many parents are overcome with negative emotions and resort to neglect or abuse (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Rothenberg, Bizzego, Bradley, Deater-Deckard, Esposito, Lansford, Putnick and Zietz2022b). Every year, child-protection agencies in the United States receive 3 million referrals for neglect and abuse involving about 6 million children younger than age 5. About 80% of perpetrators are parents. Meta-analyses confirm that parents’ poor emotion regulation contributes to their children’s internalizing and externalizing problems, physical injuries, and even death (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Rudolph, Kerin and Bohadana-Brown2022). However, only a fraction of parents who need support services receive them. Thus, organizations at all levels of society are motivated to intercede in child-rearing and right social ills through preventions, supports, and interventions, known collectively as parenting programs (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Dia, Kotler, Lansford, Raghavan and Mitter2022a). Happily, advances in parenting science have revealed that the determinants and expressions of many parenting cognitions and practices are plastic and educable. Competencies are defined to include knowledge, skills, abilities, personal characteristics, and attitudes; moreover, competencies to adequately perform a task, duty, or role are (usually) learned (Roe, Reference Roe2002). So, competent emotionally regulated parenting can be learned (even if, alas!, children do not come with an operating manual). Some core ingredients to the syllabus of emotionally regulated parenting include knowledge of how children develop; how to effectively observe children and how to interpret and use what is observed; how to manage children’s behaviors; understanding the impact parents have on children; how to take advantage of everyday settings, routines, and activities to create learning and problem-solving opportunities that enhance emotion regulation in parenting and children; and how to be patient, flexible, and goal oriented as well as extract pleasure from encounters with children.

Programs designed for parents come in a variety of venues (psychotherapy, classes, media), settings (homes, schools, clinics, houses of worship), and formats (individual, family, group), and with a variety of goals (some universal, some specific). Some programs succeed, such as the mindfulness-enhanced Strengthening Families Program (Coatsworth et al., Reference Coatsworth, Duncan, Greenberg and Nix2010), Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up (Bick & Dozier, Reference Bick and Dozier2013), the Circle of Security (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Ziv, Stupica, Sherman, Butler, Karfgin, Cooper, Hoffman and Powell2010), the Video-Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting (Juffer et al., Reference Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van IJzendoorn2008), Minding the Baby (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Sadler, De Dios-kenn, Webb, Currier-Ezepchick and Mayes2005), and Enhanced Triple P (Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Tully and Bor2000) as well as many emotion coaching interventions (Havighurst et al., Reference Havighurst, Wilson, Harley, Kehoe, Efron and Prior2013). Unhappily, however, most programs fail and do so for a wide variety of reasons, often as failures of fidelity on the part of staff to adhere to program specifics and failures of adherence on the part of parents (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Dia, Kotler, Lansford, Raghavan and Mitter2022a; Pinquart & Teubert, Reference Pinquart and Teubert2010). By critically deconstructing reasons for failures, it is possible to learn ways that future programs might succeed. Furthermore, no single program fits all parents or problems (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Castro and Steiker2011). However, solid and timely guidance on central aspects of designing, implementing, and scaling parenting programs is now available (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Dia, Kotler, Lansford, Raghavan and Mitter2022a).

Responsibilities for determining children’s best interests, including their all-important emotion regulation, rest first and foremost with parents. Parents are children’s primary advocates and the corps available in the greatest numbers to lobby and labor for children. Few ethical or sentient parents want to abrogate their child-rearing responsibilities (Thompson & Baumrind, Reference Thompson, Baumrind and Bornstein2019). Insofar as parents can be enlisted and empowered to provide children with experiences and environments that promote positive emotions and emotional regulation, society can be spared the effort and expense of after-the-fact remediation.

1.7 Conclusions

Successful parenthood ultimately means, among other things, having facilitated a child’s mature emotional regulation. To date, however, parenting theory and research in general and in emotion regulation specifically have focused too narrowly on mother and child rather than multiple family system relationships; on selected topics such as attachment to the near exclusion of others such as spirituality; on normative nuclear families when the modern world is populated with a dizzying diversity of family compositions; and on parenting in the minority Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic developed world to the proportionate exclusion of the majority developing world. Parenting is a multilevel phenomenon and will be better understood eventually by integrating evolutionary, genetic, biological, comparative, behavioral, and cultural perspectives.

As judged by psychoanalysis, ethology, psychology, and neuroscience, parents engage in a peculiar kind of life’s work: parenting is a nuanced blend of empathy, altruism, and prosociality as well as blind devotion and selflessness, and it is marked by constantly challenging demands, changing and ambiguous criteria, and all-too-frequent evaluations. Direct and indirect effects of parenting, combined with defining its principles, such specificity, timing, thematicity, moderation, meaning, transaction, and attunement render parenting less than straightforward. Parenting also entails both affective constituents (i.e. emotional commitment, empathy, and positive regard for children), and cognitive constituents (i.e. the how, what, and why of caring for children emotionally). Moreover, different child-rearing tasks are more or less salient at different points over the life course. Thus, the path to achieving satisfaction and successes in parenting is not linear, but meandering, and is not immediate and digital, but incremental and analog.

Parenthood is a signal phase of mature adulthood engaged in (if not embraced) by perhaps 80% of people around the globe. Adults in the United States (Aguiar & Hurst, Reference Aguiar and Hurst2007) and elsewhere in the world (Gauthier et al., Reference Gauthier, Smeeding and Furstenberg2004) spend more time with their children today than parents did in the past. Still, nearly one half of a US national sample of parents regrets that they spend too little time with their children. Parenthood is central to childhood and child development as well as to society’s long-term investment in successive generations and society itself. So, we are motivated to know more about the structure and sources as well as the sense and significance of parenthood and parenting as much for all of these reasons as out of the desire to improve the lives of children and the welfare of society.

Tens of thousands of new publications now appear each year on “emotion regulation.” However, despite the very high level of enthusiasm for this topic across psychology and related fields, there remains considerable confusion about what emotion regulation actually is (and is not). In this chapter, we provide an overview of this rapidly growing field, with particular attention to concepts and findings that may be of special relevance to scholars interested in the links between emotion regulation and parenting. Because any discussion of emotion regulation depends upon one’s assumptions about emotion, we begin by asking: What is an emotion?

2.1 Emotion and Related Constructs

Emotions come in many different shapes and sizes (Suri & Gross, Reference Suri and Gross2022). Sometimes emotions are pleasant; other times they are unpleasant. Sometimes they are very mild, so that we can scarcely tell we’re having an emotion. At other times, emotions are so intense that we’re scarcely aware of anything else. Sometimes it’s clear what label to apply to our emotions (e.g. anger, sadness, amusement). Other times, our emotions are hard to define. Given this remarkable diversity, affective scientists have struggled to define the core features of emotion.

2.1.1 Core Features of Emotion

According to the “modal model” of emotion (Figure 2.1), emotions may be seen as arising through a cycle that consists of four elements: (1) a situation (either experienced or imagined); (2) attention that determines which aspects of the situation are perceived; (3) evaluation or appraisal of the situation in light of one’s currently active goals; and (4) a response to the situation, which may include changes in subjective experience, physiology, and facial or other behaviors (Gross, Reference Gross2015).

Figure 2.1 Modal model of emotions

Note. Emotions commonly arise in the context of (1) a situation that is either experienced or imagined, (2) attention that influences which aspects of the situation are perceived, (3) an evaluation or appraisal of the situation, and (4) a response to the situation that alters the situation that gave rise to the emotion in the first place.

Consider an exhausted parent wheeling a shopping cart through a grocery store with a toddler in tow. The toddler can’t make up their mind as to whether they want to walk or sit in the shopping cart. So no sooner are they safely installed in the cart do they begin to ask to get down. This is the immediate situation that might lead some parents to pay particular attention to the toddler’s demands, which they evaluate as unreasonable, giving rise to feelings of anger, sweaty palms, and a stream of increasingly irritable comments to the toddler.

But the story of the parent’s emotion does not end here, because one of the sometimes-wonderful and sometimes-awful things about being human is that we are capable of metacognition. This means that our overwhelmed parent is not only becoming angry with the toddler but may also notice the fact that they are getting angry and evaluate this growing anger negatively, leading to further feelings (perhaps of guilt) along with new facial and behavioral responses, such as trying to make amends by offering the child a treat from the candy aisle.

2.1.2 Related Constructs

One point of confusion when considering emotions is how they relate to other emotion-like concepts. We find it helpful to view emotions as one cluster of instances of the broader category marked by the term affect, which refers to states that involve relatively quick good-for-me/bad-for-me discriminations. Affective states include (1) emotions such as happiness or anger, (2) stress responses in situations that exceed an individual’s ability to cope, (3) moods such as euphoria or depression, and (4) impulses to approach or withdraw.

Although there is little consensus as to how these various flavors of affect differ from one another, several broad distinctions may be usefully drawn. Thus, although both stress and emotions typically involve whole-body responses to situations that the individual sees as being relevant to their goals, stress generally refers to stereotyped responses to negative situations, whereas emotion refers to more specific responses to negative as well as positive situations. With respect to the distinction between emotions and moods, moods can often be described as being more diffuse compared to emotions. They last longer than emotions and are less likely to have well-defined and easily identifiable triggers (Frijda, Reference Frijda, Lewis and Haviland1993; Schiller et al., Reference Schiller, Yu, Alia-Klein, Becker, Cromwell, Dolcos, Eslinger, Frewen, Kemp, Pace-Schott, Raber, Silton, Stefanova, Williams, Abe, Aghajani, Albrecht, Alexander, Anders and Lowe2022). Thus, it makes sense to talk about being in a horrible mood last week, when throughout the week you were gripped by a mood that seemed to permeate your mind and body and led you to take a particularly dim view of your life and everything in it. Finally, affective impulses are perhaps the least well defined of these terms, but they are generally thought to include impulses to eat (or expel) food or drink, to exercise (or to continue to sit on the couch), or to spend time with one’s child (or to hide in the bathroom).

All four of these types of affective states can be experienced in solitary or in social contexts. In fact, it has been argued that the vast majority of our affective experiences occur in the presence of others (Boiger & Mesquita, Reference Boiger and Mesquita2012; Scherer et al., Reference Scherer, Summerfield and Wallbott1983). In this chapter, we largely focus on emotions that take place in interpersonal contexts. But many of the distinctions that are useful when thinking about emotions also apply to other types of affect (Uusberg et al., Reference Uusberg, Suri, Dweck, Gross, Neta and Haas2019).

2.2 Emotion Regulation and Related Constructs

Often, our emotions (and other manifestations of affect) seem to come and go quite haphazardly. We may feel sad at one moment, and then, inexplicably, we are cheerful at another. However, affective scientists have generally come to the conclusion that, despite the impression that emotions operate outside our control, we do often have at least some degree of control over how our emotions (and other types of affect) play out over time.

2.2.1 Core Features of Emotion Regulation

Different scholars have expressed quite different views as to how (and whether) emotion reactivity and emotion regulation should be distinguished (Gross & Feldman Barrett, Reference Gross and Feldman Barrett2011). We propose that emotion regulation requires that (1) an emotion is evaluated as either good or bad and (2) this evaluation activates a goal to change the intensity, duration, type, or consequences of the emotion in question (Gross et al., Reference Gross and Feldman Barrett2011). With regard to the evaluation of an emotion as good or bad, emotion regulation can be conceptualized as a functional coupling of two valuation systems. In this formulation, a first-level valuation system takes the situation (e.g. a fussy toddler) as its object and gives rise to the emotion (e.g. irritation). This first-level system then becomes the object of a second-level valuation system, which leads to the metacognitive evaluation of the emotion itself as either good or bad (e.g. as when we feel bad about feeling irritated with our toddler) (Figure 2.2; Gross, Reference Gross2015). In our view, it is this second-level valuation of a first-level emotion that creates the context in which emotion regulation may arise via the activation of an emotion regulation goal.

Figure 2.2 First-level and second-level valuation systems

Note. Emotion regulation involves the functional coupling of two valuation systems, in which a first-level valuation system that is instantiating emotion (Figure 2.1) becomes the object of a second-level valuation system that takes the emotion as its object (Gross, Reference Gross2015). S = situation, A = attention, E = evaluation, R = response.

The goals that drive emotion regulation can be broadly subdivided into self-focused and other-focused regulatory goals. One note on this distinction: one of us has previously referred to this distinction as between intrinsic and extrinsic emotion regulation (Gross, Reference Gross2015). However, we now prefer the self-focused and other-focused terminology as it avoids any potential confusion with motivational meanings of the terms intrinsic and extrinsic.

When a person’s second-level valuation system takes as its object a first-level valuation system that is active within that same person – in other words, when a person engages in regulation with the intention of changing their own emotions – such regulation is considered self-focused (Gross, Reference Gross2015). Engaging in deep breathing when feeling irritated at one’s toddler, looking away from a scary movie scene, confiding in a friend after a disappointing career setback, and eating a bowl (or a tub) of ice cream to lift one’s spirits after a romantic breakup are all examples of self-focused regulation. In contrast, when the second-level valuation system takes as its object the first-level valuation system of another person – in other words, when a person engages in regulation with the intention of changing someone else’s emotions – such regulation is considered other-focused (see Figure 2.3; Nozaki & Mikolajczak, Reference Nozaki and Mikolajczak2020). For example, a parent who intentionally diverts a child’s attention away from being stuck in an over-lit and crowded grocery store during nap time and a person who helps their friend reappraise a disappointing career setback are both engaging in other-focused regulation.

Figure 2.3 Other-focused emotion regulation

Note. One of the two valuation systems that define emotion regulation is active in one person (person X on the left, in whom the second-level valuation system is active) and the other valuation system is active in another person (person Y on the right, in whom the first-level valuation system is active). In this dyad, person X activates the goal to modify person Y’s emotion.

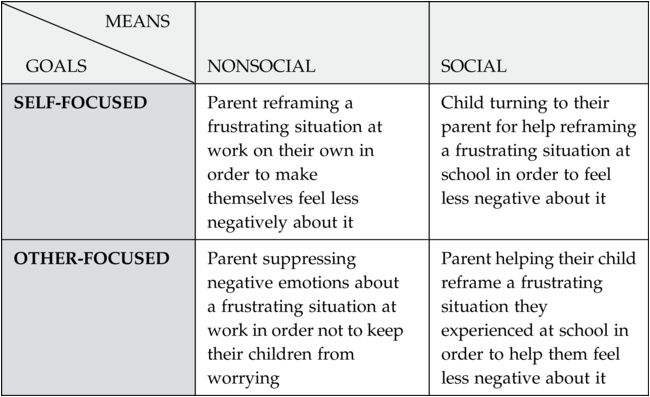

It is estimated that most emotion regulation episodes take place in social contexts (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Richards, John, Snyder, Simpson and Hughes2006). As a result, both self-focused and other-focused regulatory goals can be attained through nonsocial as well as social means. Regulation through nonsocial means refers to processes whereby an individual takes steps to change their own (self-focused nonsocial) or someone else’s (other-focused nonsocial) emotions without assistance from other people. In contrast, regulation through social means refers to processes whereby an individual takes steps to change their own (self-focused social) or someone else’s (other-focused social) emotions in a way that directly engages the cognitive, attentional, or behavioral resources of at least one other individual (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Examples of two categories of regulatory goals (self-focused and other-focused) accomplished via two categories of regulatory means (non-social and social)

| MEANS | NONSOCIAL | SOCIAL |

|---|---|---|

| GOALS | ||

| SELF-FOCUSED | Parent reframing a frustrating situation at work on their own in order to make themselves feel less negatively about it | Child turning to their parent for help reframing a frustrating situation at school in order to feel less negative about it |

| OTHER-FOCUSED | Parent suppressing negative emotions about a frustrating situation at work in order not to keep their children from worrying | Parent helping their child reframe a frustrating situation they experienced at school in order to help them feel less negative about it |

2.2.2 Related Constructs

Paralleling the distinctions between emotions and other types of affective responses, emotion regulation can be seen as a special case of the broader category of affect regulation. This category includes (1) emotion regulation, (2) coping, (3) mood regulation, and (4) impulse regulation (Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross, Thompson and Gross2007). Much of our goal-directed behavior can be construed as maximizing pleasure or minimizing pain, and thus falling under the umbrella of affect regulation in the broad sense. It can be useful to sharpen the focus by examining a few of these regulatory processes in greater detail.

Coping can be distinguished from emotion regulation both by its principal focus on decreasing negative affect and by its emphasis on longer time periods (e.g. coping with the challenge of having a child who has special needs). As noted previously, moods are typically of longer duration than emotions and are less likely to involve responses to specific “objects.” In part due to their less well-defined behavioral response tendencies, compared to emotion regulation, mood regulation is typically more concerned with altering one’s feelings rather than behavior. Impulse regulation broadly refers to the regulation of appetitive and defensive impulses (e.g. to opt for a slice of cake instead of fruit salad or to back out of giving a presentation in front of a large audience). One form of impulse regulation that has attracted particular attention is self-control (Duckworth et al., Reference Duckworth, Gendler and Gross2016). Although the distinctions we have drawn here can be helpful in orienting to relevant literature, there is growing evidence that affect regulation processes may share a number of features despite the differences in their regulatory targets (for an integrative affective regulation perspective, see Gross et al., Reference Gross, Uusberg and Uusberg2019).

Another important distinction can be drawn between emotion regulation and other processes that may lead to incidental changes in one’s emotional experience. Consider, for example, a high-schooler who received the sad news that he did not get into his dream college just moments before going to a friend’s birthday party. The mere presence of other people at the party might help ameliorate his sadness even if neither he nor his friends had a goal (explicit or implicit) to do so. This phenomenon has been referred to as social affect modulation (Coan et al., Reference Coan, Schaefer and Davidson2006; Zaki & Williams, Reference Zaki and Williams2013). What sets emotion regulation apart from these more incidental forms of modulation is that emotion regulation is necessarily goal directed.

2.3 The Process Model of Emotion Regulation

One widely used framework for studying emotion regulation is the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, Reference Gross1998, Reference Gross2015). This framework delineates four stages of emotion regulation: identification, selection, implementation, and monitoring (Figure 2.4). Each stage culminates in a decision (conscious or otherwise) that the regulator makes and that propels them toward their emotional goals (Braunstein et al., Reference Braunstein, Gross and Ochsner2017; Gross et al., Reference Gross, Uusberg and Uusberg2019; Koole et al., Reference Koole, Webb and Sheeran2015). The four decisions that correspond to the four stages of regulation are (1) whether to regulate, (2) what strategies to use in order to regulate, (3) how to implement said strategies under the circumstances, and (4) whether to modify one’s ongoing emotion regulation efforts in any way (e.g. by selecting a different strategy or discontinuing regulation altogether).

Figure 2.4 Process model of emotion regulation

Note. According to the process model of emotion regulation, four stages define emotion regulation. The first three of these correspond to the second-level valuation steps of attention, evaluation, and response. The fourth is the monitoring stage. Five families of emotion regulation strategies may be distinguished based on where they have their primary impact on emotion generation: situation selection, situation modification, attentional strategies, cognitive change, and response modulation.

One advantage of the process model is that it can be used to describe both self-focused and other-focused emotion regulation attained via both nonsocial as well as social means (i.e. all cells in Table 2.1). In a two-person interaction, both partners can perceive their own emotional states. These perceptions provide input into the four stages of self-focused emotion regulation. In addition to perceiving their own emotions, both parties can also form dynamic mental representations of each other’s emotional states. These representations feed into the four stages of other-focused emotion regulation that mirror those of self-focused regulation. Whatever the partners’ emotional goals may be, their decisions at each stage can also lead them to pursue such goals via nonsocial or social means (Figure 2.5). In the following sections, we consider the four stages of emotion regulation and illustrate how the process model can be usefully applied to instances of social and nonsocial emotion regulation.

Figure 2.5 Other-focused regulation accomplished via social means

Note. Panel A: person X directly regulating person Y’s emotion. Panel B: person X encouraging person Y to regulate Y’s emotion.

2.3.1 The Identification Stage

At the identification stage, the regulator identifies a gap between the actual (or projected) and desired emotional state (i.e. the emotion goal) and decides whether to take action to shrink that gap. If the gap in question is between the regulator’s own experienced and desired emotional states, the decision to take action would set in motion self-focused regulation. If, on the other hand, the gap in question is between the regulator’s representation of another person’s emotional state and the emotional state that the regulator wants to see enacted in the other person instead, the result will be other-focused regulation. In the case of other-focused regulation, the regulator may come to the decision to regulate independently (e.g. by noticing another person’s angry demeanor) or as a result of a direct request for regulatory assistance.

Often, desired emotional states are the ones that maximize pleasure and minimize displeasure (e.g. happiness, contentment). But people can also value other aspects of emotional states (e.g. motivational), leading them to desire emotional states that are useful but not particularly pleasant (or even patently unpleasant; Ford & Gross, Reference Ford and Gross2019; Tamir, Reference Tamir2016). For example, a parent might scold their child for hitting their sibling in order to upregulate the child’s feelings of guilt and deter them from committing similar transgressions in the future. In this case, the parent views guilt as a desired emotional state (because of its high motivational value) despite the fact that it can also be an extremely unpleasant emotion to experience. This is an example of what is called counterhedonic emotion regulation (Zaki, Reference Zaki2020). Note that, in the case of other-focused regulation, the desired state may be determined by the regulator’s beliefs about the target’s goals, the regulator’s goals that are independent from (and that might even go against) those of the target, or some combination of the two.

2.3.2 The Selection Stage