Population censuses offer data on which the formulation and testing of hypotheses on issues such as labour markets, fertility, religion, service delivery, taxation, and health rely. Population counting is also a landmark of state sovereignty, located at the intersection of ‘the political project of developing the administrative infrastructure and authority of a modern state, the cultural project of constructing the communal bonds . . . of a modern nation, and the scientific project of producing useful knowledge about the population’.Footnote 1 Scholars in African studies have interrogated censuses to assess the reliability of demographic statistics, to shed light on the working of states, and to investigate questions of power and identity.Footnote 2 Yet this literature's emphasis on data quality and on the ways in which census forms and enumeration practices ‘constructed’ ethnic and racial categories has prevented a broader assessment of the place of population counting in the political culture of the postcolonial state. This paper suggests that the circulation, appropriation, and contestation of census figures in the press represent productive avenues for the historicization of the politics of counting people.

Nigeria represents an ideal setting for reflection on this issue. Indeed, in Africa's most populous country the census has been (and continues to be) a politically explosive issue. As the basis of parliamentary representation and the allocation of amenities and social services, the census has been a pivotal element in the social contract linking the federation, the states composing it, and the citizenry. It has also been a powerful catalyst for the articulation of narratives about identity, ethnicity, and the viability of Nigeria as a nation-state. Following a review of how Africanists have looked at census taking, we use the controversies surrounding the 1963 census as a lens to identify and analyse different ways in which the meanings and implications of the census were articulated. Inspired by the rich historiography on African print cultures, this article explores the ways in which newspapers and pamphlets rearticulated the political meanings and implications of the count.Footnote 3 Although grounded in Nigerian specificities, this exercise points to the importance of going beyond a conceptualization of the politics of census taking that focuses on statistical categorization or on the political economy of numbers, in favour of analysing the wider range of media and representations through which demographic figures shape public debates.

Census taking in Nigerian and African history

From data quality to the political economy of numbers

There are several possible ways of historicizing census taking in Africa.Footnote 4 One avenue is to interpret the census as a source for demographic history and thus treat its evolution as the starting point of a reflection on data quality. Between the late nineteenth century and independence around 1960, colonial regimes across the continent produced several attempts to count their subjects for purposes of taxation, military conscription, and the acquisition of knowledge for use in policy making.Footnote 5 However, the quality of the data in colonial censuses was often dubious. Contemporary sources describe the persistent administrative and political challenges associated with counting people, including a lack of staff and funding, low state capacity, and the reluctance and resistance of the enumerated people — often depicted as resulting from a mixture of African ‘cultural taboos’, ‘ignorance and superstition’, and fear of taxation.Footnote 6 As a consequence, demographers have intensely debated the possible uses (as well as limitations) of colonial censuses for reconstructing Africa's demographic past. With reference to the Belgian Congo, Northern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland, Bruce Fetter noted that, in spite of being poor guides for an estimation of the magnitude of a country's population, colonial censuses are useful tools for making inferences about its structure. They thus contribute to the debate on the impact of colonial rule on living standards.Footnote 7 More recently, Ewout Frankema and Morten Jerven turned to the history of census taking in colonial and postcolonial Africa to reassess the continent's demographic evolution. Besides suggesting an upward revision of total population figures, they also reiterated that colonial censuses should not be dismissed altogether as sources for the magnitude of Africa's population.Footnote 8 They further stressed the importance of analysing state capacity and the incentives faced by census takers and enumerated subjects (alongside more consolidated interpretations of demographic evidence and intercensal growth rates) as determinants of the validity and reliability of population figures.Footnote 9

The political economy of numbers has occupied a prominent role in the extensive literature on Nigeria, where counting people has largely taken place within a set of incentives that associated expected benefits with the inflation of population figures.Footnote 10 Given the importance of population returns for federal parliamentary representation and the allocation of federal revenues and social services, it is not surprising that Nigerian census results have been hotly contested. Since the 1950s, this contributed to the institutionalization and reinforcement of a divisive political imagination that posited the (predominantly) Muslim ‘North’ against the (predominantly) Christian ‘South’, while on the other hand problematizing the relationship between ethnic identities and the acquisition of power to rule over ‘others’. The enduring influence of the last colonial census can be observed in the strong reactions to the declaration of Harold Smith, a former colonial civil servant employed by the Department of Labour, that the figures of the last colonial census in 1952 had been inflated to guarantee that the North had more than 50 per cent of the total population.Footnote 11 Arguably, this was the consequence of British perceptions of the North as more collaborative and conservative, compared to other regions that were seen as subversive sites of nationalist agitation. While their veracity is contested, Smith's claims reiterate the centrality of the census as a catalyst of tensions in postcolonial Nigeria and point to the long shadow of the colonial political economy.Footnote 12 Did the existence of strong incentives to inflate the figures (and the fact that instances of inflation have been documented in the case of specific communities) mean that misreporting happened on a systematic basis? On the basis of demographic tests and political economy considerations, most scholars agree that this has indeed been the case.Footnote 13 So, too, does the National Population Commission, which in its report on the 2006 census admitted that ‘varying degrees of overenumeration of population was rampant throughout the country coupled with omission of certain settlements in the earlier census exercises, and this possibly contributed much to the unacceptability of the census.’Footnote 14 However, other commentators, most notably the demographer Paul Olusanya, emphasized in the 1980s that the ‘problems of population enumeration in Nigeria are largely problems of under-development, of ignorance, of mass illiteracy. Even if there was no political rivalry, our data gathering efforts would still be vitiated by more important factors.’Footnote 15 The 2006 census has shown that the removal of questions on ethnicity and religion and the introduction of new technologies, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS) and optical mark and character recognition software for the reading and processing of questionnaires, was not enough to avoid controversy.Footnote 16 Furthermore, that count was allegedly still affected by logistical and organizational challenges.Footnote 17

Focusing, as most scholarly literature on the Nigerian census does, on the relationship between the federal government and the states misses other crucial aspects of the political economy of population figures. Indeed, the benefits resulting from the inflation of figures were conducive to the creation of new patterns of inequality that can only be observed by ‘zooming in’ and looking at the life of specific towns and local communities, as shown by the experience of different towns in southwestern Nigeria during the 1962 and 1991 censuses.Footnote 18 But communities’ attempts to shape the outcomes of the censuses not only targeted population figures but also involved a wider array of social practices, including deliberate modification — and sometimes defacing — of public spaces. Relying on what his father told him, an informant reported in 2019 that shortly before the 1963 census ‘in Lagos Island . . . public taps were vandalised.’Footnote 19 Similarly, even though the government had transformed the Ajele cemetery into a playground where ‘people used to go and play football and have races’, ‘just before the census came they started bringing some tombstones back [from Ikoyi, where the cemetery had been relocated] to the place to say it [the playground] wasn't existing.’ By defacing the playground, the perpetrators of this act wanted to give the enumerators a distorted view of reality that they hoped would translate into additional amenities for their community.Footnote 20 Although at this initial stage of our research it is premature to comment on the representativeness of practices such as this (in Lagos and elsewhere), this anecdote is a powerful reminder of how little we know of the multiple ways in which the Nigerian census was understood, negotiated, and mobilized for political and economic gain.

Even accounting for this multiplicity, there is a crucial difference between the political economy of census taking and that of other forms of quantification, such as registration and vital statistics, which have attracted much attention in recent years.Footnote 21 While both can function as claims to entitlement vis-à-vis the government, the latter can also grant benefits — and pose risks — to families and individuals, rather than just to demographic cohorts or larger communities.Footnote 22 Historically, the perception associated with documenting births and deaths has been profoundly asymmetrical, with the former seen as more likely to produce entitlements.Footnote 23 An exception to this can be observed in contemporary Kaduna, where the closures of textile mills led dismissed workers and their families to set up the Coalition of Closed Unpaid Textile Workers Association Nigeria. The assemblage of lists of dead workers (with individual names and dates of death) became a lynchpin of the community's discursive and political response to the hardship caused by the mill closures. Indeed these mortality data, produced by the widows of the dead workers and other actors associated with the coalition, became ‘an important step for clarifying the socioeconomic impact of textile mill closures, deindustrialization, and unemployment’.Footnote 24 Being mobilized as tools ‘to put pressure on the government and textile mill management to live up to their agreement to pay workers’ remittances’, these lists simultaneously allow widows and other coalition members to ‘commemorate the dead and employ their names for the benefit of the living’.Footnote 25 The mutual construction of the practice of listing and documenting individual deaths, mourning, remembering, and claiming monetary compensation suggests that, while crucial, the political economy of numbers is only one of the dimensions of the politics of counting people.

Imagined communities, categories, and agency

Drawing on an intellectual genealogy that sees the work of Michel Foucault, Benedict Anderson, and James Scott as crucial nodal points, recent histories of the phenomenon of the census, no longer confined to the domains of political economy and historical demography, have reflected instead on the conceptual categories employed by colonial states as disciplinary tools of governance or as instruments of nation making.Footnote 26 Yet, as shown by the case of Somali communities in Kenya, histories of colonial statistics illuminate the epistemic and administrative constraints faced by colonial states.Footnote 27 The combination of porous borders, nomadic lifestyle, lack of perceived economic potential, and low political priorities attached to the North Eastern Province of Kenya led the colonial administration to see the Somalis as ‘less legible’ than other communities and to devote few resources to the collection of accurate population figures on them. Although it had the potential to fashion the ‘imagined community’ of the nation state, in practice the colonial census consolidated inequalities in the government's perception of different ethnic groups. This, in turn, justified and exacerbated the unevenness underpinning the construction of statistical knowledge about different categories.Footnote 28 More generally, the significant gap between the colonial state's ambition to make societies ‘legible’ through demographic knowledge and its limited capacity to intervene on the ground calls into question the applicability of James Scott's notion of ‘seeing like a state’.Footnote 29 With reference to colonial Nigeria (but not with reference to the census), the point has been forcefully made by Steven Pierce, who concludes that the process of ‘state formation is not one of a government coming to “see like a state” but rather of a transformation that enabled it to look like one’.Footnote 30

A significant strand in the literature on census taking has emphasized the capacity of the census to remake, rather than simply describe, identities.Footnote 31 In Africanist historiography, the focus has been primarily on the statistical construction of religious and ethnic identities under colonial rule and its legacies. The importance of this enterprise found its most tragic justification in the genocide perpetrated by the Hutu against the Tutsi in Rwanda. In his influential When Victims Become Killers, Mahmood Mamdani stressed the crucial role of the censuses held under the Belgian administration in constructing and institutionalizing these ethnic categories.Footnote 32 If Rwanda and Burundi are among the ‘very few countries where social constructivist expectations regarding identity and category seem to be so well verified’, discussions about ethnicity in Nigeria have not attributed a prominent role to colonial census taking.Footnote 33 On the other hand, one of the fundamental aims of the 1921 census of Nigeria was precisely the creation of an ethnic map.Footnote 34 Recent literature has focused on rescuing African voices and agencies rather than documenting the interiorisation of statistical categories. As shown in the case of the forest zone in 1920s northern Gabon, a possible approach consists in stressing the profound ontological and epistemic alterity of the colonisers’ understanding of famine and depopulation by contrasting it with the narratives through which the local populations made sense of the same phenomena.Footnote 35 Similarly, as discussed with reference to the Western Ijo, Nigeria provides a rich setting for the observation of the disjunction between the concept of household adopted by the statistical apparatus and that used by the counted subjects.Footnote 36 Taking a middle ground between the two extremes of ‘interiorization’ and ‘epistemic alterity’, the census can be treated as a site of encounter and mediation between representatives of the state and its subjects. In this process, identities and statistical categories are not unequivocally imposed, but rather strategically negotiated. This was the case, for example, in southern Mali in the 1940s and 1950s, when communities that largely sustained indigenous religious practices self-identified as Muslims.Footnote 37 While this self-identification echoed an ancient way of dealing with stronger Muslim powers, through the census it became a strategy to navigate the new uncertainties associated with colonial rule.Footnote 38

However, it would be inaccurate to limit the realm of census-led agency to identity appropriation and self-identification. Resistance and contestation are deeply embedded in the history (and historiography) of demographic knowledge.Footnote 39 While Africanists have repeatedly emphasized the contested status of population figures, an analysis of the concrete modalities by which demographic statistics were received and challenged is virtually absent from the extensive literature on resistance and African civil society.Footnote 40 The focus has been on resistance to being counted (especially in colonial times) or on the consequences of census figures for economic development and political representation, rather than on the specific forms of their contestation.Footnote 41 In contrast, histories of statistics in other parts of the world provide a rich departure point from which to think about how resistance to the census, or the critical reception of demographic numbers, become intertwined with the production and circulation of textual and visual artefacts in the public sphere.Footnote 42 Indeed, social and cultural histories of census taking make extensive use of the press.Footnote 43 Their exploration of statistics in the public sphere raises interesting questions about numbers’ capacity to inspire people's trust, ‘transform public conceptions of authority and accountability’, and ‘permeate political debate’.Footnote 44 Inspired by this literature, the remaining part of this paper analyses how the press ‘made’ the 1963 Nigerian census. Through a close reading of daily newspapers and pamphlets published in different parts of Nigeria, the article treats the census as an entry point into the ‘multiplication of modes of constituting textual meanings and imagining communities’ associated with print cultures.Footnote 45 The journey across different genres, formats, and reading publics reveals the plasticity of the census in Nigerian political imagination and documents its capacity to both consolidate and subvert the ‘imagined community’ of the nation.

Population figures and the balance of power

At the time of independence in October 1960, Nigeria's parliamentary democracy appeared fragmented along ethnic and religious lines. The political landscape was dominated by three parties, each finding its main source of support in the ethnic groups that dominated the different regions of Nigeria: Nnamdi Azikiwe's (and, later, Michael Okpara's) National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC, which later stood for National Convention of Nigerian Citizens) in the Igbo-dominated southeast, Chief Ọbafẹ́mi Awólọ́wọ̀'s (and later Chief Samuel Akíntọ́lá's) Action Group (AG) in the Yoruba-dominated southwest, and Sir Ahmadu Bello's Northern People Congress (NPC) in the Hausa-Fulani dominated North.Footnote 46 At independence, the NCNC was allied with the NPC, while the AG was the main opposition party. As it will be shown, the 1962 and 1963 counts played an important role in altering the relationships between key political stakeholders. Besides serving as the basis for social and economic planning, the 1962 census was also supposed to provide the basis on which a new electoral roll would be compiled for the 1964 federal election: after being counted, each eligible person would receive a voter's card.Footnote 47

What made the results of the 1962 census politically explosive was the fact that, for the first time in Nigeria's statistical history, the North had less than 50 per cent of the total population of the country, which could have implied the loss of an absolute majority in the House of Representatives. The situation was intensified by the fact that the Daily Express, a Lagos-based daily, published some ‘unofficial’ figures which gave to the North a population of 11 million, thus bringing it close to the results of the 1931 census.Footnote 48 But this, as commented by David Muffett in the 1960s (who, given his involvement in the 1952 census in the Northern Region, had a vested interest in defending the results of the last colonial census), amounted to an argument ‘that the 1952 figures must have been 65% inaccurate, or that a holocaust of epidemic proportions had occurred in the intervening years, which could have hardly gone unnoticed’.Footnote 49 It is as part of this anxiety over the Northern figure that we should understand the accusation voiced by the Eastern press that, even after the 1962 figures became common knowledge, counting was still going on in the North. Whether or not this was true, Federal Minister of Economic Development Waziri Ibrahim, a businessman from Borno State, claimed that the Northern population could have been around 22 or 30 million people.Footnote 50 A member of the Eastern House of Assembly interpreted this as an admission that, by recounting (or continuing to count), the North was actually ‘looking’ for the ‘missing’ people.Footnote 51 Whether or not this was the case, the final report on the 1962 count submitted by the federal census officer to the cabinet allegedly provided a reestimated figure of 30 million people for northern Nigeria.Footnote 52 Nonetheless, the federal census officer's claim that the 1962 returns were false rested primarily on the East's returns being too high (and the population growth since the 1952–3 count being too fast compared with that of other regions) and the fact that the Western Region had submitted returns for only 5 out of 62 divisions.Footnote 53 Indeed, the census took place at a time when two competing visions for the Western Region and its place within the federal order confronted each other. The rivalry between Awólọ́wọ̀ and Akíntọ́lá resulted in a parliamentary crisis.Footnote 54

The 1962 count began in May, at the time when the federal government declared the state of emergency. The Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa announced the need for a second count. Balewa reiterated that the census would provide the basis for an updated electoral register for the 1964 federal election and remarked that the count was ‘a call to national duty’.Footnote 55 Unlike its predecessor, which stretched over two weeks, the 1963 census took place over only four days (5–8 November) in order to limit internal migration and double counting. The responsibility for the census was removed from the Ministry of Economic Development and the regional governments and allocated to a newly created institution, the Census Board. Its membership was comprised of United Nations statistical experts and representatives of all the different regions of the federation.Footnote 56 With the employment of almost 150,000 enumerators and costing around £2.5 million, the new count was the largest and most expensive statistical inquiry in the history of the country.

The 1963 census gave the North a much larger figure of 29.8 million, thus marking its return to being recognized as having an absolute majority of Nigeria's population. With a figure of 12.39 million, the East now accounted for only 22 per cent of the total population (in contrast with the 27 per cent resulting from the 1962 census). Michael Okpara, the Eastern Region's new premier, declared the figures ‘worse than useless’.Footnote 57 The census marked a dramatic point in the deteriorating relationship between the NPC and the NCNC. The latter had already grown disillusioned, feeling that ‘it was not receiving benefits at the federal level commensurate with its position as a coalition partner.’Footnote 58 The newly created Mid-Western Region, a NCNC stronghold which had been carved out of the Western Region a few months before the enumeration began, was given a population of 2.5 million (or 5 per cent of the total). Chief Dennis Osadebay, the premier of the Mid-Western Region, initially sided with Okpara in rejecting the count, but eventually accepted the census figures.Footnote 59 In practice, Osadebay's acceptance of the figures isolated the East and provided a significant boost to the figures’ legitimacy.Footnote 60 Demographer I. Ekanem speculated that, due to Akíntọ́lá's alliance with the NPC, the North had given the Western Region higher figures.Footnote 61 Regardless of the veracity of this allegation, Akíntọ́lá mobilized the satisfactory census results to consolidate his power in the Western Region and gain the support of many who had remained loyal to Awólọ́wọ̀ and the AG.Footnote 62 Key NCNC politicians in the West turned their backs on Okpara, and joined Akíntọ́lá's latest creation, the Nigerian National Democratic Party.Footnote 63 It is clear that the 1963 figures were not at the centre of a single, circumscribed ‘census controversy’, but rather were mobilized in different political scenarios by a wide range of historical actors with competing agendas. The remaining part of this paper follows a specific strand of the controversies over the 1963 results, limited to one site of narrative production and contestation. In what follows, we explore how the English-language press amplified the struggle over the construction of the ‘North’ and the ‘East’, in which the census played such a central role.

The census in the press: From enumeration and testing to ethnic stereotypes

It is difficult to underestimate the importance of the press in Nigeria's political and cultural history.Footnote 64 Under colonial rule, the country's future political leaders capitalized on the power of the printed word to consolidate reading publics, create diasporic spaces, and forge alliances and identities.Footnote 65 In the 1960s, newspapers contributed to the drawing of the contours of the ideological arena within which the battles for the country's postcolonial future would be fought and exacerbated preexisting conflicts. This was mirrored in an increasingly inflammatory rhetoric and an editorial landscape that closely reflected (and in large part contributed to the construction of) the ethnic constituencies of different political parties.Footnote 66 The press inscribed the population figures within the wider canvas of the making and unmaking of the Nigerian nation in a variety of ways.

A first important narrative thread in the contestation of the 1963 figures centred around enumeration practices and tests. The testing was based on comparing three sets of figures: the actual census enumeration returns, an independent estimate based on a sample of enumeration areas for each census district, and the returns of the precensus house count exercise.Footnote 67 For each of the more than 300 census districts into which the country had been divided, thirty enumeration areas were selected to be part of the sample. In all these enumeration areas, a local enumerator and an inspector from a different region (the latter being a novelty of the 1963 count) recorded the population.Footnote 68 The house numbering exercise took place two weeks before the main enumeration. Enumerators were sent to identify all dwelling units and to obtain from the residents the number of people usually living there, divided by sex.Footnote 69 In a press statement, Okpara listed the numerous reasons that forced him, as the Eastern Region's premier, to reject the count's results.Footnote 70 A first significant problem was represented by the fact that the enumeration areas included in the sample, which should have remained secret until after the main enumeration was complete, were already made known in the North even before the count. What followed in Okpara's list of grievances was a series of specific accusations of malpractice and irregularities in counting that were allegedly observed firsthand by Eastern inspectors in the Northern Region. These included counting in market places (after the Census Board had decided to limit enumeration to people's houses and other specifically identified ‘special areas’ like hospitals, prisons, and universities), counting of travellers and passersby without staining their thumbs (thus allowing for the possibility that they would be counted again), and counting of persons not seen (in spite of the fact that the enumerators were supposed to count by sight). Okpara also maintained that Eastern inspectors were counted as part of the Northern population, thus contravening to the Census Board's decision that inspectors should have been included as part of their constituencies’ population.Footnote 71

What emerges from these accusations is a narrative about the micropolitics of falsification that describes it as a process that involved primarily the enumerators and the counted subjects in the field, rather than policy makers at the top levels of political decision-making. A particularly controversial aspect of Okpara's accusations, because it presented the process of enumeration as conflicting with established Northern cultural practices, was the alleged ‘refusal of entry into purdah’. Because of this, enumerators were allegedly asked to accept at face value the number of wives and females declared by the head of the household. This claim constituted simultaneously a violation of counting by sight, one of the main principles of the census, and an invitation to consider how accounts of data collection procedures became intertwined with the derogatory crystallization of ethnic and cultural identities. Okpara's press statement also included some data on the distribution of districts that failed statistical tests relating to the population count in the four main regions (Lagos was excluded; see Table 2). He claimed that the Northern returns appeared suspicious because the districts that in theory had been randomly selected for testing displayed a suspiciously high level of homogeneity. Secondly, while it was assumed that it would have been difficult to enumerate more than 600 people per day, in several Northern districts more than 900 people had been enumerated in one day. Okpara was also surprised that the figures were published before applying sex and age ratio tests, which were designed to ‘spot out any area that has been inflated’.Footnote 72

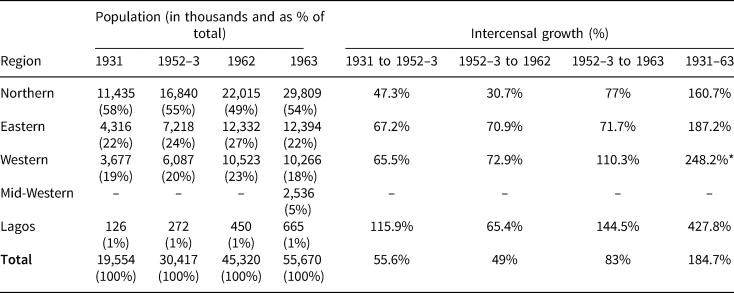

Table 1. Magnitude, regional composition, and growth of the Nigerian population, 1931–63.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on S. Jacob, Census of Nigeria, 1931, Volume I: Nigeria (London, 1933), 95, table 1; Nigeria Department of Statistics, Population Census of Nigeria 1952–53 (Lagos, 1953), 2, table 1; Federal Republic of Nigeria, Population Census of Nigeria 1963, Volume III: Combined National Figures (Lagos, n.d.), 52, 54–6. The figures attributed to the 1962 census, which were never officially published, are taken from M. Iro, ‘The demography of Nigeria, 1950–1966: with special reference to the methods and accuracy of the population censuses during this period’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Cornell University, 1973), 39.

Note: The 1931 figures exclude the Cameroons. The 1952–3 figures exclude the population of Southern Cameroons and the trust territories in the Adamawa, Benue, and Bornu Provinces. It should also be noted that the census was held in the Northern Region in June 1952, in the West and in Lagos in December 1952, and in the East in June 1953. The final figures reported refer to a midyear estimate of 1953; see Nigeria Department of Statistics, Population Census of Nigeria, 1, table A.

* All intercensal growth rate calculations for the Western Region, including the 1931–63 one, include the Mid-Western Region.

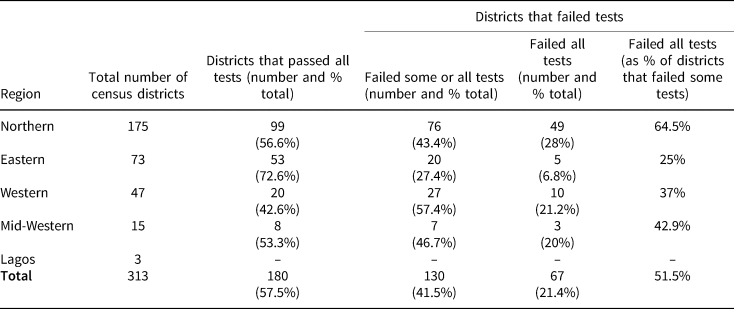

Table 2. Performance of census districts in statistical tests.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Okpara, ‘Press statement’, 4.

A high proportion of districts failed some or all tests in the Western (57.4 per cent), Mid-Western (46.7 per cent), and Northern (43.4 per cent) Regions. At the national level, only 57.5 per cent of census districts passed all tests and, among those that did not, more than half failed all tests. However, in the Northern Region the severity of the problems identified was much greater. There, of those districts that did not pass all tests, 64.5 per cent failed all of them, compared to 37 per cent in the Western and 42.9 per cent in the Mid-Western Regions. According to Okpara, the significant extent of (and thus deliberate) miscounting in the Northern Region set it apart from the rest of Nigeria and led him to conclude that ‘those guilty of inflation have condemned us all as a country incapable of conducting a Census’.Footnote 73

Ahmadu Bello, the sardauna of Sokoto and premier of the Northern Region, promptly responded to Okpara's criticism. His strategy was simple: to take all the accusations made against the North and redirect them against the East. One was that the East, unlike the North, had refused to reestimate (and downsize) the population figures of the districts that had failed all other tests by using the housing counts (Table 3).Footnote 74

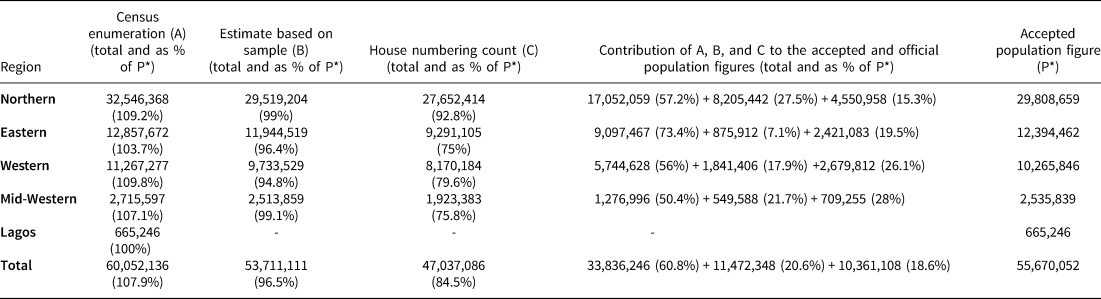

Table 3. Returns of alternative population counts and estimates, and their contribution to the 1963 official figure.

Source: Iro, Population Censuses of Nigeria, 76.

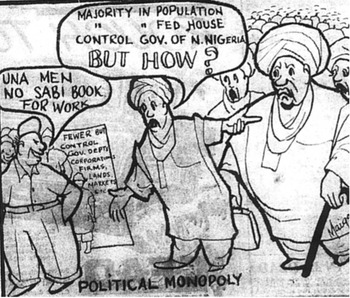

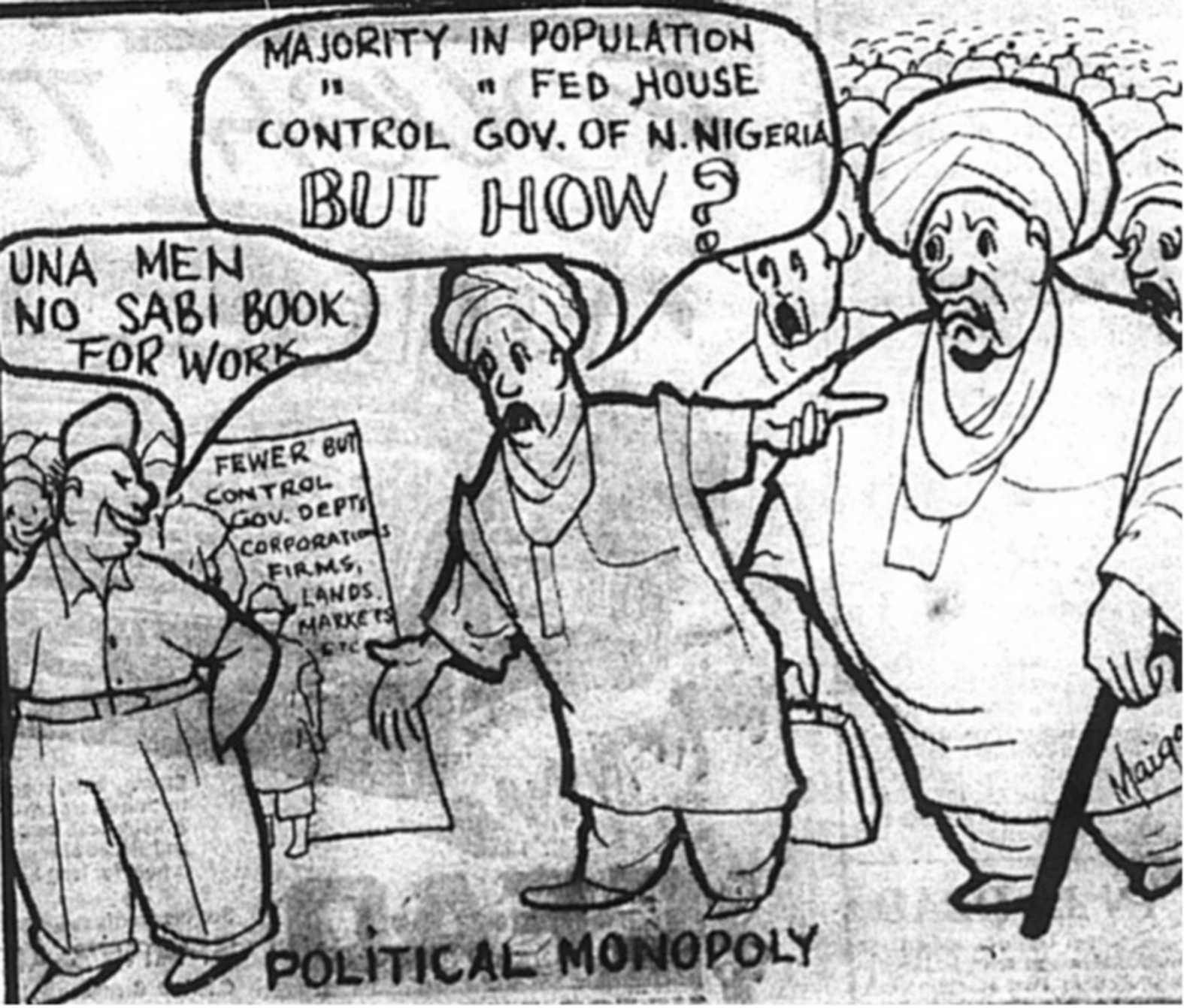

In his response to Okpara, Bello added two elements that enriched seemingly factual statements about how the numbers were collected with further meanings and associations. The first was that, if anything, the impossibility of counting women by sight would have resulted in undercounting rather than overcounting.Footnote 75 Second, Bello claimed that Eastern enumerators in the North did not have any incentive to contribute to the inflation of another region's figures. In theory, the use of inspectors from other regions should have ensured that the 1963 census represented a truly national enterprise that overcame ‘tribalist’ interests.Footnote 76 However, the use of Eastern inspectors in the North resonated with a deep-seated cause of tension in the balance of political power. If Southern politicians felt threatened by the numbers of the North, which had been the legal basis on which their majority in the parliament was determined, the North had its own fears of having already become an object of Igbo economic domination. These fears were grounded in the dynamics of colonial rule, in which the disparity in English-language education led the British colonial administration to rely increasingly on southern Nigerians to administer the North. The sheer size of the North's population was presented in turn as the basis on which the Northern Region could expose what it perceived as an unjust oppression. This can be observed in the cartoon below from the Northern daily Nigerian Citizen (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. 'Political monopoly'.

Source: Nigerian Citizen, 18 Apr. 1964, 1.

The Igbo man tells the northerners, ‘You guys do not have enough education to work’, but the cartoonist's choice to make him speak in pidgin was possibly meant to undermine the credibility of this self-representation. The North's resentment at what was seen as the Igbo control of trade and administration had been since the 1950s one of the main drivers behind the ‘Northernization policy’.Footnote 77

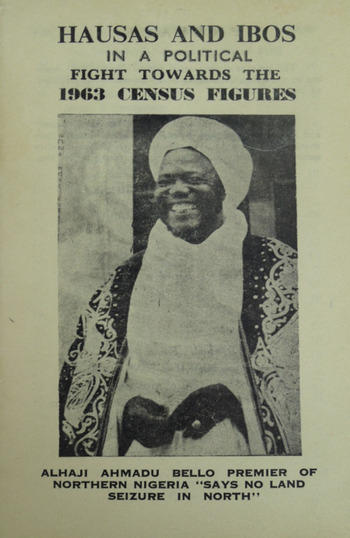

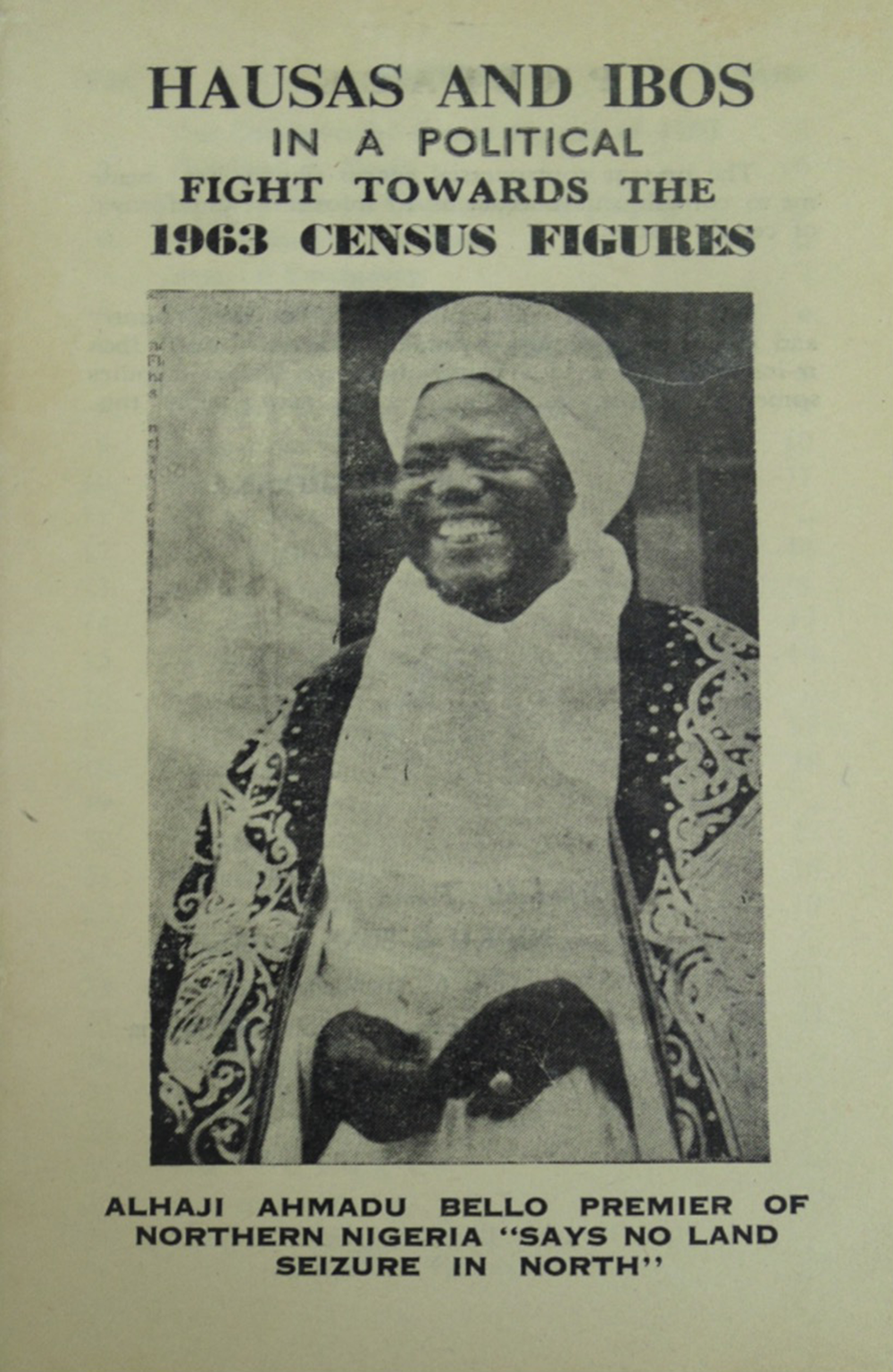

In the southeast, discussions of the North's stance informed a wide range of publications, cutting across different genres and formats. This could be observed in Onitsha, the city which hosts Nigeria's largest popular literature market.Footnote 78 An anonymous pamphlet on the census controversy published there (Fig. 2) reported the Northern premier's (and Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa's) denials of the accusations that some Igbos living in the North had had their lands and properties expropriated, but also called for a commission of inquiry to shed light on the matter.Footnote 79 If the commission of inquiry found evidence of expropriation, the anonymous author of the pamphlet maintained that it would be necessary to declare a state of emergency.Footnote 80

Figure 2. Back cover of the pamphlet Hausas and Ibos in a Fight towards the 1963 Census Figures (Onitsha, n.d.).

The Ibo State Union published excerpts of the parliamentary debates in the Northern House of Assembly.Footnote 81 These quotations reveal the full extent to which the census controversy became intertwined with the poisonous rhetoric of interethnic conflict. In the face of the Igbo people's supposed ‘cheating with the census’, the solutions envisaged by some members of the Northern parliament included the revocation of Igbo individuals’ occupancy licences, the confiscation of their land and properties, and their deportation.Footnote 82 A delegate called for the revocation of immigrants’ medical licences because he thought that Igbo doctors would use them ‘to administer medicine to kill most of our people’.Footnote 83 The Ibo State Union concluded that this ‘war of attrition’ represented ‘an organised attempt to annihilate a group of people for whom the Republic's Constitution guarantees common citizenship and fundamental rights’.Footnote 84 This claim could be read as a commentary on ethnic violence targeting the Igbo communities in the North, and as a premonition of the tragedy that would unfold during the Nigeria-Biafra war.Footnote 85

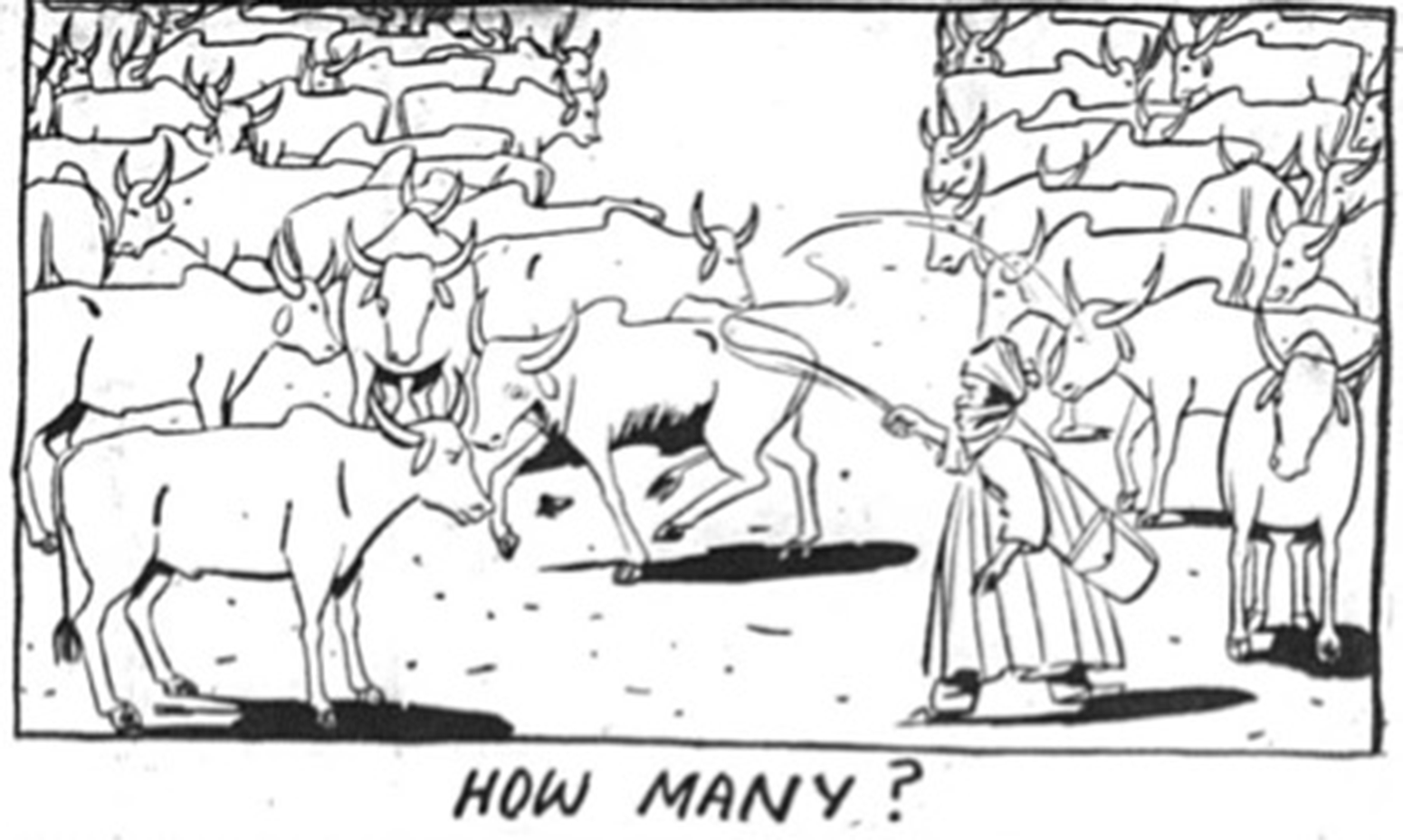

Although occasionally the press tried to placate the census crisis, several newspapers deployed the census results to promote stereotypical and provocative representations of cultural and ethnic traits.Footnote 86 For example, the West African Pilot, the mouthpiece of Okpara's NCNC, published a cartoon showing a lonely herder, swinging a whip, directing cattle (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. ‘How many?’.

Source: West African Pilot, 31 Mar. 1964, 1.

The image provides a visual representation of the widely held rumour that the North's population figure was so high because cattle, as well as people, were enumerated.Footnote 87 More generally, the cartoon reiterated the vision of the North as a vast but empty space and of northerners as ‘backwards’ pastoralists. Population density — which, with the exception of Lagos, was on average highest in the East (420 persons per square mile) and lowest in the North (106 persons per square mile) — became a recurring trope in the contestation of the figures, with the East claiming that the northern population returns were too high given the low population density of the region.Footnote 88 It should also be noted that in some parts of the North (like in the Sokoto Caliphate, for example) the most important form of counting for social and political purposes involved the enumeration of cattle, which was central to estimating people's wealth and taxation, disputes over succession, and alms giving.Footnote 89 If read in connection with the accusations raised about the impossibility of counting women by sight, this cartoon seems also to suggest that the cultural traits associated with the North were an obstacle to a ‘modern’ state that found in counting people, rather than cattle, its main enumerative practice.Footnote 90 Meanwhile, in the northern city of Kano, the Nigerian Citizen had also been producing derogatory narratives (Fig. 4).

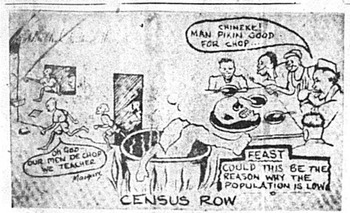

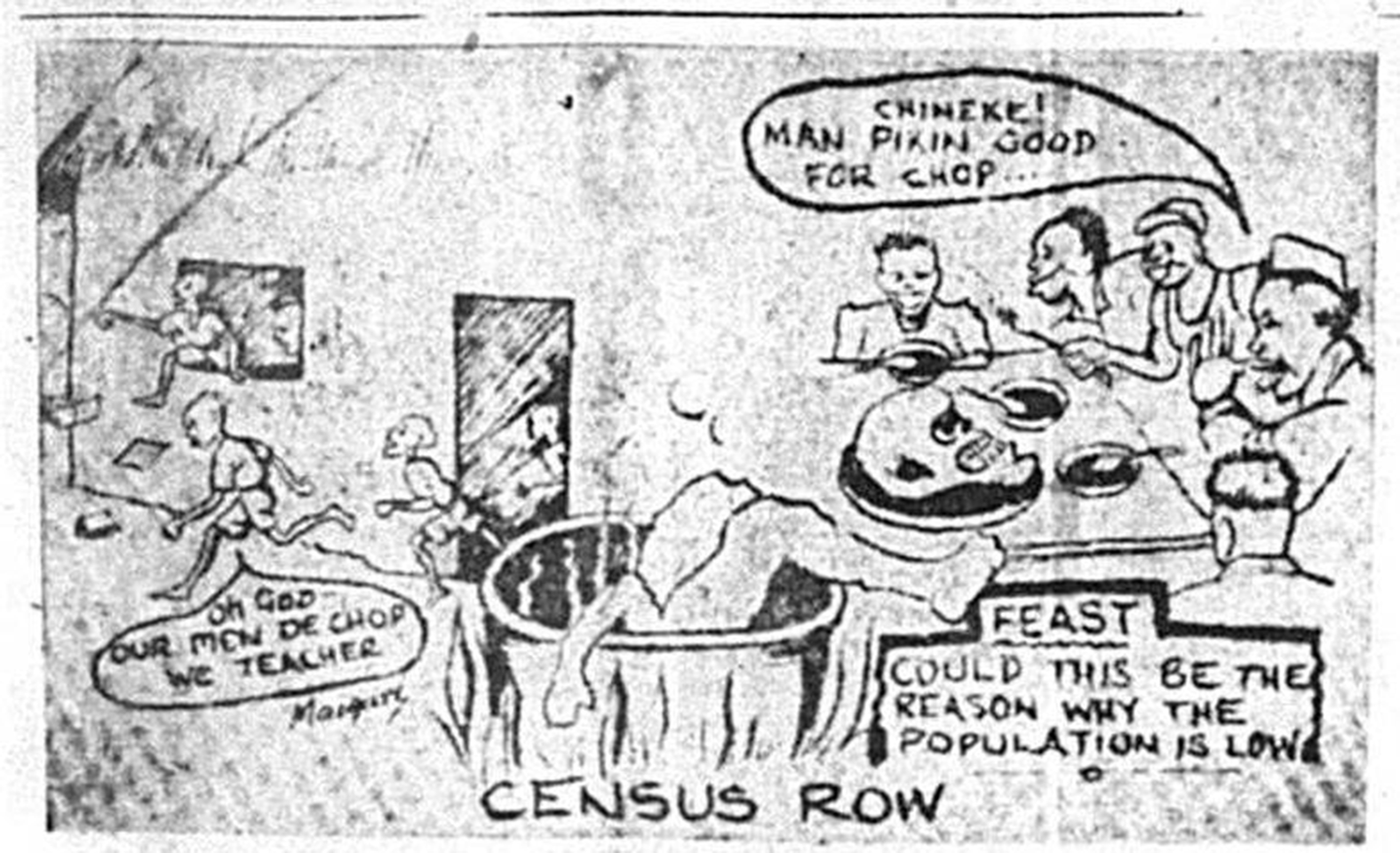

Figure 4. ‘Census row’.

Source: Nigerian Citizen, 7 Mar. 1964, 1.

This incendiary cartoon suggested that the population gap between the North and the East was not the consequence of the North's deliberate attempt at manipulating the figures, but rather the result of cannibalism in the East. The West African Pilot republished it as evidence of the hateful campaign conducted in the North: ‘We do not think the way to foster unity and a sense of belonging to “one family” is to show one section of the Nigerian community as cannibals.’Footnote 91 Two Igbo men sent indignant letters to the Nigerian Citizen, accusing Malam Maigari, the author of the cartoon, of an ‘ignorant and low mentality’ and asking him for evidence to support his claim.Footnote 92 Maigari responded that ‘it happened during the Colonial rule’.Footnote 93 This exchange points at the importance of representations of the colonial period in Northern discourse about the census. First, this acceptance of the veracity of colonial knowledge was true for the census figures: the North's claim that their figures were more accurate than those produced by the South was based on the firm acceptance of the supposed fact that colonial censuses were fundamentally accurate. For example, in his response to Okpara's statement, the premier of the Northern Region, Ahmadu Bello, quoted the 1931 figures (which were highly unreliable) as the basis of his claim that, since the 1930s, the North's population had grown much less than that of the West, the East, or the national average (see Table 1).Footnote 94 Similarly, the North rejected the results of the 1962 census on the basis that a 71 per cent growth in the East's population between 1953 and 1962 must have been the consequence of an overcount in the postcolonial census, rather than an undercount in the colonial one.Footnote 95 Finally, the reference to colonial rule as a time in which cannibalism was widespread among the Igbos echoed accounts written by missionaries.Footnote 96 The Nigerian press contributed to the drawing of new spatial and temporal coordinates along which the nation could elaborate the relationship between its present and its future.Footnote 97 This could lead to novel and imaginative representations of political belonging, but also, as in the case of census-inspired cartoons, to the recycling of tropes of the colonial imagination and a diminished possibility of envisaging a postcolonial future of unity and harmonious coexistence. Nor did such strains only occur through the consolidation of ethnic identities. By inscribing the census within narratives of ineptitude, the press amplified ordinary Nigerians’ negative perceptions of the political and administrative establishment as a whole:

The nation is ashamed of counting and recounting itself. I know politicians are used to asking for a recount. It was said of one of them that when he was told his wife had given birth to triplets, he demanded a recount! I agree with those who cried out that the figures are astronomical. . . . But I cannot say how, or who juggled with the figures. I cannot say on oath who in the North, or the East or the West committed forgery. . . . May God give us strength and wisdom to battle against the gathering storm.Footnote 98

If the joke about the politician asking for a recount of his own children is a reminder of the importance of humour in criticizing ruling elites, the article's overall tone was one of uncertainty and anxiety.Footnote 99 Sixty years later, the conflicting rumours and questions about whose actions and agendas shaped the figures remain pressing.

Conclusions

The final act of the First Republic's battle over the 1963 census figures shifted the terrain of contestation from the realm of the printed word to that of the rule of law. On 18 May 1964, the Eastern Region filed a suit against the federal government to prove that the 1963 census was ‘illegal and unconstitutional’ and thus had to be declared ‘null and void’.Footnote 100 It was the first time that a regional government sued the federal government in the Supreme Federal Court, thus marking a potentially destabilizing precedent for the country's politics. The Supreme Federal Court, however, dismissed the Eastern motion.Footnote 101 The figures were ‘accepted’ and projections based on them used as the basis of social and economic planning.Footnote 102 The 1964 federal elections, conducted in an atmosphere of violence and intimidation, created a parliamentary allocation that mirrored the close link between political parties, regions, and their ethnic constituencies, thus highlighting the political significance of the census.Footnote 103 Although they played a significant role in undermining the fragile foundations of the First Republic, the 1963 figures had a longer lifespan due to the repression of the census held by Yakubu Gowon's military government in 1973. Indeed, the next census that would be accepted took place only in 1991.

In spite of the many discontinuities that marked the political landscape of postcolonial Nigeria, the census has continued to play a crucial role as an allocative framework, as a template through which ordinary Nigerians make claims vis-à-vis (or about) the state, and as a platform for contestation.Footnote 104 Over the years, Nigerian scholars and policy makers have repeatedly pleaded for the necessity of ‘depoliticising’ the census, thus reinforcing a dichotomous distinction between the ‘political’ and ‘technical’ aspects of population counting.Footnote 105 But what is political about census taking to begin with? Our exploration has blurred the boundaries between the two and has pointed to the malleability of the census in the political imagination. This paper has focused on print cultures as one possible avenue for simultaneously broadening our understanding of the politics of counting people and showing how it works in the public sphere. In spite of their diversity, the ethnically charged cartoons in daily newspapers and the claims about enumeration practices and tests made by Ahmadu Bello and Michael Okpara should be understood as part of the same discursive framework, which used the census as a foil to reflect fears of domination and produce representations of ‘alterity’. Seemingly ‘factual’ statements about data collection procedures or population density fed a divisive political imagination. The census exacerbated the conflict between different groups and, in the process, led to their redefinition as either regions, ethnic groups, or cultural formations. It has been shown that the history and historiography of population counting in Africa are rife with such examples. However, in contrast with the literature's emphasis on identification, categorization, and enumeration, we suggest that the Nigerian census acquired crucial meanings and implications by inspiring a plethora of visual and textual representations.

A close look at these representations indicates that the politics of counting people cannot be reduced to the political economy of population figures. Nor should it be confined to the census forms’ reification of ethnic and racial categories or to the encounter between the enumerated subjects and the statistical apparatus. Instead, it should interrogate the many other ways in which numbers shape the discourse about public trust, identity, and the state.Footnote 106 Studying the census as a trope in print cultures is one of many ways in which demographic historians of Africa can broaden their gaze and reflect on how, through their appropriation and circulation in the public sphere, population figures tell stories and create meaning.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the Institut d’Études Avancées de Nantes; the Institut d'Études Politiques de Rennes; the Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique, Ibadan; the Department of History, University of Ibadan; and the Third European Society of Historical Demography Conference (Pécs, 2019). We are grateful to these events’ organisers and participants, as well as to Olutayo Adesina, Steven Pierce, and the reviewers for their insightful comments. Gerardo Serra would like to thank Elodie Apard, Clémentine Chazal, the entire IFRA staff, and Olutayo Adesina for their kind hospitality in Ibadan; as well as the University of Sussex's History Department and the University of Manchester's School of Arts, Languages and Cultures for funding archival trips in Britain, USA, and Nigeria. Morten Jerven's research was supported by Noragric (Norwegian University of Life Sciences) and funding from Lund University and the Swedish Research Council for ‘African States and Economic Development in the 20th Century: Capacity to Count and Collect’ (2017-05564). COVID prevented returning to Nigeria to gather further archival material and oral testimonies. Thanks are due to the librarians and archivists of the institutions preserving the sources on which this paper is based: Oxford's Bodleian Library, the British Library, the British Library of Development Studies (Sussex), Northwestern University's Melville J. Herskovits Library, Duke University's David M. Rubenstein Library, the National Archives of the United Kingdom (London), and the Ibadan branch of the National Archives of Nigeria. All errors remain our responsibility. Authors’ emails: [email protected], [email protected].