The National Service Framework (NSF; Department of Health, 2004) promotes a multi-agency approach as good practice in child and adolescent mental healthcare: ‘the needs of children and young people with complex, severe and persistent behavioural and mental health needs are met through a multi-agency approach’. Effective consultation and liaison requires targeted sharing of knowledge and information in the best interests of the child patient (Reference LamingLaming, 2003). Specialised child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) provide a mix of direct and indirect (consultation and liaison) services. This requires communication between agencies with different backgrounds, roles and working practices.

Child and adolescent mental health services in Dudley offer a consultation service to referrers; we audited the use of time allocated for this purpose. Data collection was complicated by a lack of clarity in the allocation and booking systems, making the process difficult to follow and outcomes difficult to assess. The first part of the audit concerned the process of consultation; results were fed back to CAMHS and after multidisciplinary discussion changes were implemented. The second part of the audit, completing the cycle, reviewed the consultation process for a 6-month period thereafter.

Method

The gold standard was derived from principles laid down in the NSF (Department of Health, 2004), Every Child Matters (Chief Secretary to the Treasury, 2003) and Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council, 2006).

-

• Referral pathways, the organisational process and the aims of the consultation should be clear.

-

• Communication, discussion and decisions should be documented and accessible post-consultation.

-

• Attendance should be documented and named workers should be made responsible for recommended actions.

-

• Professional time should be used as effectively as possible.

At the beginning of the audit all users referred from education and social services were offered an initial consultation. This decision was made at the weekly multidisciplinary ‘allocation meetings’. A date was booked on the ‘consultations sheet’ by a named staff member who was responsible for organising the meeting. When the consultation meeting occurred, it was documented in the relevant case notes.

During the first part of the audit we attempted to trace the information back from consultation forms and allocation minutes, and searched for the notes from these records. At re-audit, a new spreadsheet was used to identify all consultations that had occurred and was cross-referenced with the allocation meeting minutes.

Results

Audit

The initial audit identified 128 available slots for consultation over a 3-year period. Of these, 74 were booked and 47 were not; the remaining 7 were illegible. Of the 74 names documented on the booking forms, 15 had been booked on more than one occasion, giving a total of 59 individuals referred.

Only 20 sets of these notes were found through the card-based filing system, which failed to locate the notes in 32 cases. Of the notes found, a record of an arranged consultation existed in 16. There were 14 letters of invitation and only 1 letter confirming attendance.

Twelve consultations occurred, with written notes found for ten; the standard of note-keeping varied. In eight sets of notes all attending professionals were noted and in three their functions were indicated. Discussions were documented in all ten sets of notes; nine included decisions and an action plan, although only three had a designated professional responsible for implementation. Two summarising letters to participants were filed.

Often allocation meeting decisions were inaccessible and the consultation booking sheet was unclear. There was no consistent way of discovering whether or not a consultation had actually occurred. The consultation process lacked clarity and consistency of objectives; documentation of meetings held was poor, documentation of attendees inconsistent and specified actions were not clearly delegated. There was potential for confusion between agencies due to lack of clarity regarding roles and responsibilities. There was no standardised form of communication between the referrer and CAMHS. It was often impossible to discover from case notes whether or not communication had taken place.

As we could locate the relevant case notes for so few of the consultations, referrer satisfaction was impossible to assess. This made fitting the service to need difficult. We were also unable to assess outcomes and effectiveness reliably in this part of audit.

The audit results were presented to the whole team (including administration staff) and recommendations for change were proposed and discussed. The team recommended that:

-

• the name of the service be clarified

-

• the allocation meeting record form be revised

-

• the use of a standard consultation documentation form be instituted.

Dedicated administrative support for the consultation meetings was also arranged; the person responsible for administration used Microsoft Excel to prepare a spreadsheet to manage use of consultation time.

Re-audit

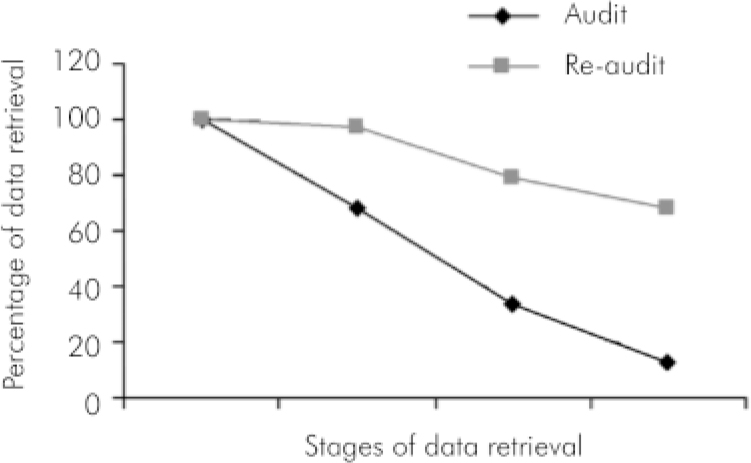

Re-audit covered a 6-month period subsequent to the adoption of team-derived service changes. Overall, 34 available dates were identified, with 29 slots available for use; 28 slots were booked, and 23 meetings were held. Of the five that did not occur, this was recorded in the records of four and reasons were given for three. For the 14 consultations that occurred and for which the notes were found, a record was available of all people present, with initial and surname (legible) with function (Table 1). Between 2 and 11 people attended. In eight cases, no review was planned, in two a further consultation was planned, and in five this information was not recorded. The improvement of information retrieval is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 1. Comparison of results

| Audit, n (%) | Re-audit, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Time span, months | 36 | 6 |

| Slots available for use | 128 | 29 |

| Slots booked, % of slots available | 74 (58) | 28 (97) |

| Named children | 59 | 29 |

| Slots used, notes found: % of named children with slots booked Information quality (found notes only) | 12 (20) | 14 (50) |

| Attendees recorded, % of slots used, notes found | 8 (67) | 14 (100) |

| Discussion documented, % | 10 (83) | 14 (100) |

| Decisions documented, % | 9 (75) | 14 (100) |

| Action plans made, % of slots used, notes found | 9 (75) | 14 (100) |

After re-auditing, the results were presented to the team, positive changes were emphasised and further modifications were proposed and discussed. It was suggested that staff and referrer satisfaction with the service and resource effectiveness should be assessed: do consultations actually make a difference to outcomes? The audit process continues.

Discussion

This audit cycle raised three main challenges. First, how to examine and institute change in a service perceived by staff to be functioning suboptimally? Second, how to audit a complicated process? Finally, how to improve that process without alienating the staff who had called attention to difficulties in the first place?

Fig. 1. Progressive loss of information during the two phases.

Auditing the process of interdisciplinary consultations is challenging. Although both mandated and necessary, there is little literature on auditing multi-agency work. It was necessary to define an ideal process and audit to theoretical standards. The service had arisen in response to national guidelines and perceived need, but process and objectives were not clearly defined. What we found in the first audit revealed deficiencies in two areas: there was a progressive loss of information at each step of the process and the quality of recorded information varied greatly.

Several factors contributed to incomplete documentation including: lack of designated administrative support; poor note-keeping; use of a card-based filing system; inconsistent documentation of telephone calls; poor documentation of information sharing; and lack of a standardised recording format. There was also no written protocol for how the service should function. The card-based filing system was the biggest problem in locating notes.

However, CAMHS staff were involved at all stages and actively sought service improvement. Their continued engagement meant that they ‘owned’ the changes from the outset. The first audit results provided impetus for change and remained a baseline against which practice could be later assessed.

Limitations of the audit

First, only the CAHMS service was assessed and although it is the host agency for the consultation process, there were other agencies involved and these were not audited.

Second, we focused on documented information, gathered in a standard way with a standard data collection form; a more flexible, but more time-consuming, interview-based approach would probably have led to more information being found, but would have been less repeatable.

Third, the review period (6 months) was shorter than the original audit period (36 months) and perceived improvement could be caused by a ‘honeymoon effect’ rather than long-term changes to the service.

Finally, we focused on the process of the consultation procedure and can therefore not comment on the outcomes of this service.

Conclusions

The consultations spreadsheet made it considerably easier to identify the young people referred for consultation. Changes made were proposed and owned by staff from the outset and the improved results on re-audit show that improvement is possible even within complicated systems, and need not necessarily be painful. The changes made were simple and whole-team discussion helped clarify the process of, and rationale for, consultations. This could argue for the involvement of the whole team at the beginning of a new service activity, in terms of setting and instituting documentation criteria from the outset. As the audited staff were actively involved in the identification of potential improvements, we are hopeful that positive changes will be maintained over time.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the staff of the CAMHS service in Dudley for their support, patience and enthusiasm for positive change.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.