The valosin-containing protein (VCP) is a ubiquitously expressed protein involved in cellular proteostasis through regulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, endolysosomal sorting, and autophagy.Reference Meyer and Weihl1 Dominant missense mutations in the VCP gene disrupt these processes and lead to a multisystem proteinopathy characterized by inclusion body myopathy (IBM), Paget’s disease of bone (PDB), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (IBMPFD).Reference Watts, Wymer and Kovach2 The condition is phenotypically heterogeneous, even within families, and manifests with myopathy in 90% of patients, PDB in half of patients, and FTD in one third of cases.Reference Weihl, Pestronk and Kimonis3 More than half of all reported VCP mutations cluster within the protein’s N-terminal domain responsible for binding interacting partners.Reference Evangelista, Weihl, Kimonis and Lochmuller4 Cases of IBMPFD have been reported among several populations,Reference Evangelista, Weihl, Kimonis and Lochmuller4 but none have yet been described in French Canadians. Herein, we report a French Canadian family with IBMPFD associated with a c.466G>A (p.Gly156Ser) mutation in VCP.

The proband (Figure 1A, Table 1) was a high-school graduate welder who presented at age 32 for a 5-year history of slowly progressive proximal leg weakness. He started requiring ambulatory aid at age 35 and became wheelchair-bound 2 years later. Intrinsic hand and finger weakness developed 12 years from disease onset and was followed by proximal arm and neck extension weakness. Voice hoarseness and dysphagia were first noted at age 47. His language deteriorated shortly after, with word-finding difficulty, loss of word meaning, and comprehension deficits. He did not manifest overt behavioral change. At age 50, he required bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation at night due to orthopnea. Neurological examination revealed fluent and grammatical speech, occasional paraphasic errors, surface dyslexia, and deficits in phonemic and semantic verbal fluency (3 and 8 words/1 min, respectively). He had slight cognitive rigidity, but was engaged, collaborative, and insightful. He had flaccid dysarthria, mild bifacial weakness, tongue weakness, bilateral scapular winging as well as severe diffuse symmetrical amyotrophy and weakness (Medical Research Council [MRC] scale 0–2/5). There were no upper motor neuron signs. His Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score was 25/27 (figure drawing could not be performed but he could draw clock’s hands) due to deficits in repetition and word fluency. Electromyography (EMG) revealed end-stage electrically silent lower extremity muscles and very chronic myopathic features with fibrillation potentials and myotonic discharges in the upper limb and facial muscles. Pulmonary function tests were consistent with severe restrictive lung disease. Serum creatine kinase (CK) and alkaline phosphatase levels were normal. Skeletal series did not show signs of PDB. Brain MRI showed atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes, slightly more significant over the left temporal lobe (Figure 1B and C). Biopsy of the right deltoid (Figure 1D–F) revealed myopathic changes, scattered rimmed vacuoles, transactive response DNA binding protein 43 (TDP-43) immunoreactive cytoplasmic deposits, and numerous cytochrome oxidase (COX)-reduced fibers.

Figure 1: Pedigree, imaging, and pathological findings of the French Canadian family with VCP c.466G>A (p.Gly156Ser) mutation. (A) The pedigree was randomized to preserve the privacy of the family. Age at time of latest evaluation or at time of death is indicated. The arrow indicates the proband. Slashed symbols designate deceased individuals. An autopsy of the brain was obtained in subject II.3. Subjects II.1, II.2, and II.3 had the VCP c.466G>A mutation while subjects I.1 and II.4 did not. Axial (B) and coronal (C) T1-weighted brain MRI images in subject II.2 show bilateral frontal and temporal atrophy, which is slightly more significant over the left temporal lobe. Photomicrographs from right deltoid muscle biopsy of subject II.2 (D–F) and from brain autopsy of subject II.3 (G–I). (D) Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing moderate variation in fiber size and muscle fibers with rimmed vacuoles or filamentous bodies. (E) Modified Gomori trichrome stain revealing frequent rimmed vacuoles. (F) Immunostain highlighting amorphous cytoplasmic TDP-43 reactive deposits. (G, H) Hematoxylin–eosin–saffron staining showing moderate neuronal loss in (G) frontal lobe and severe loss in (H) layer 2 of parahippocampal gyrus. (I) Immunostain revealing crystalloid TDP-43 reactive intranuclear neuronal inclusions in layer 2 of frontal cortex. Anti-phospho TDP-43 antibody, clone 1D3, dilution 1:500. Scale bars in D–F, 50 µm; G, 500 µm; H, 100 µm; I, 20 µm.

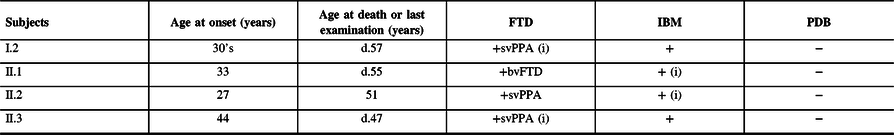

Table 1: Summary of clinical findings

FTD = frontotemporal dementia; bvFTD = behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; IBM = inclusion body myopathy; PDB = Paget’s disease of the bone; svPPA = semantic variant primary progressive aphasia.

The first clinical manifestation is indicated by an (i) and age at onset is provided. The age at death (d.) or at latest examination is indicated.

Subject II.1 presented at age 43 for a 10-year history of slowly progressive leg weakness and 2 years of proximal arm weakness. She started requiring ambulatory aid a year prior to evaluation. Neurological examination revealed weakness of the neck flexors, deltoid, triceps, biceps, iliopsoas, quadriceps, and tibialis anterior muscles (MRC 4-4−/5) as well as significant atrophy of the vastus medialis. Serum CK was normal. EMG showed abundant fibrillation potentials in all muscles, frequent myotonic discharges, and small polyphasic motor unit action potentials (MUAP). She became wheelchair-bound by age 50 and subsequently developed rapidly progressive cognitive dysfunction and behavioral disinhibition. She died of aspiration pneumonia at age 55.

Subject II.3 was evaluated at age 45 for rapidly progressive dementia. Neurological examination revealed fluent aphasia, logorrhea, echolalia, mild weakness of the deltoids and quadriceps (MRC 4+/5), and mild atrophy of the vastus medialis. CK levels were normal. EMG revealed widespread increased insertional activity, occasional complex repetitive discharges, rare myotonic discharges, and few small polyphasic MUAPs in the quadriceps. The patient was placed in a hospice 2 years later where she died of aspiration pneumonia shortly after. Pathological examination of the brain (Figure 1G–I) showed variable neuronal loss in the frontal and temporal cortex with marked atrophy of the parahippocampal cortex and relative sparing of the hippocampus, consistent with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). Numerous elongated or crystalloid TDP-43 immunoreactive intranuclear inclusions were seen, most frequent in the parahippocampal gyrus and frontal cortex, and absent in the hippocampus.

Although we did not assess subject I.2, historical data indicate onset of semantic language dysfunction in her 30s with frequent paraphasic errors and impaired single-word comprehension and object naming. She then experienced progressive behavioral deterioration and lower extremity weakness as a consequence of which she became wheelchair-bound in her late 40s. She died of aspiration pneumonia at age 57.

Next-generation sequencing using a commercial neuromuscular gene panel identified a heterozygous missense variant (c.466G>A; p.Gly156Ser) in exon 5 of VCP in the proband. The panel also included the genes ALS2, ANG, ATXN2, C9orf72, CHMP2B, DCTN1, FIG4, FUS, MAPT, NEFH, OPTN, PARK7, PFN1, PRPH, PSEN1, SETX, SIGMAR1, SOD1, SQSTM1, TARDBP, UBQLN2, and VAPB. No variant was identified in any of these genes. Sanger sequencing of the exon 5 of VCP identified the same variant (c.466G>A) in subjects II.1 and II.3 but not in subjects I.1 and II.4. Although subject I.2 could not be tested, her phenotype suggests that she carried the same variant. This mutation was previously reported in a sporadic Japanese case of VCP-related multisystem proteinopathy with IBM, PDB, and FTD.Reference Komatsu, Iwasa, Yanase and Yamada5 The glycine residue at position 156 in the N-terminal domain of VCP is evolutionarily conserved and located in the center of a ligand-binding cavity.Reference Hubbers, Clemen and Kesper6 This mutation is predicted to force the local structure into an incorrect conformation thereby disrupting ligand binding.Reference Venselaar, Te Beek, Kuipers, Hekkelman and Vriend7

Clinical evaluation was consistent with a semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (PPA) in subjects II.2 and II.3 while subject I.2’s history was compatible with such diagnosis. PPA is less often reported with IBMPFD compared to behavioral variant FTD.Reference Evangelista, Weihl, Kimonis and Lochmuller4,Reference Krause, Gohringer and Walter8 Pathological brain examination of subject II.3 at autopsy confirmed FTLD with abundant TDP-43 immunoreactive intranuclear neuronal inclusions. IBM was clinically suspected in all subjects based on the findings of muscle weakness and myogenic EMG patterns but could be pathologically confirmed in one case only. Characteristic sarcoplasmic TDP-43 immunoreactive aggregates and rimmed vacuoles were found in subject II.2’s muscle. Although none of our patients had symptoms suggestive of PDB, it was only excluded in the proband. The absence of radiological survey and alkaline phosphatase screening in the other subjects prevents us from ruling out asymptomatic PDB. This cohort broadens the phenotype of VCP p.Gly156Ser genotype and highlights the intrafamilial clinical variability that is characteristic of IBMPFD.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the family for allowing us to publish this report. The acquisition of the brain MRI was supported by grant RR172248 from the Weston Brain Institute.

Disclosure

DP, BE, PK, MR, M-JD, LP, JPL, JK, SD, and BB report no conflicts of interest. RM reports grants from Pfizer, personal fees from CSL Behring, personal fees from Genzyme, nonfinancial support from Grifols, outside the submitted work.

Statement of authorship

DP prepared the manuscript and contributed the majority of background research. BE, PK, and JK contributed to pathological interpretation and figure preparation. M-JD and LP contributed to genomic studies interpretation. MR, JPL, SD, RM, and BB contributed to manuscript preparation and reviewing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.