Persistent low mood with lack of enjoyment (‘anhedonia’) is common and often hard to treat in psychiatric practice. Recent changes in the two major diagnostic classification systems – ICD-11 released in June 2018 (World Health Organization 2018) and DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) – make the time apposite to review the diagnostic categories relevant to persistent mood disorders.

There is significant diagnostic overlap with emotionally unstable/borderline personality disorder, with several common features, such as impulsivity, mood instability, inappropriate anger, suicidal behaviour and unstable relationships. The recent history of psychiatric classification has oscillated between the placement of dysthymia and cyclothymia as mood disorders (state disorders) or as personality disorders (trait disorders). Similarly, of the bipolar affective disorders, bipolar II disorder has many features suggestive of a chronic trait disorder (such as dysthymic mood) rather than an episodic state disorder (typified by bipolar I disorder). The problems with classification reflect practical difficulties in clinical diagnosis. The reliability of these manualised diagnostic categories is also imperfect. The reliability of the diagnostic categories for DSM-5 from field trials are reported from eleven academic centres involving 264 patients (Regier Reference Regier, Narrow and Clarke2013). The correlation between clinicians varied from 0.28 (questionable reliability) for major depressive disorder to 0.54 (good reliability) for borderline personality disorder. By contrast, field trials for ICD-11 involved 28 centres in 13 countries with over 1800 patients and 339 clinicians (Reed Reference Reed, Sharan and Rebello2018). Intraclass kappa correlation coefficients for selected disorders ranged from 0.45 for dysthymic disorder to 0.64 for a depressive episode (good reliability for both).

The category of ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’ has been dropped from ICD-11 and was never used in the recent DSM manuals – both manuals now use the term ‘borderline personality disorder’.

The treatment of bipolar affective disorder typically relies on medication (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2009), including mood stabilisers such as lithium, whereas treatment of personality disorder is largely based psychotherapy (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014). There tends to be an assumption that type I and type II bipolar disorder are related, although there are actually significant differences in clinical presentation and they may be quite separate diagnostic entities (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

DSM-5 uses the term ‘persistent depressive disorder’ to include chronic depression and dysthymic disorder entities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Symptoms overlap with those of other disorders characterised by persistent low mood and lack of enjoyment, including bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder. These disorders have several common characteristics and the distinction is often difficult. Moreover, persistent mood disorders are widespread. For example, dysthymic disorder has been estimated to have a life-time prevalence of up to 2–4% in the general population, and borderline personality disorder is estimated to affect around 1–2% of the population. The prevalence of bipolar II disorder varies from 0.4 to 0.8%, although the prevalence is also affected by the duration of hypomanic symptoms (Angst Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen2010). All persistent mood disorders are associated with greatly increased risk of suicide (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Dubo1998; Kessler Reference Kessler, Berglund and Demler2005; Merikangas Reference Merikangas, Akiskal and Angst2007; Grant Reference Grant, Chou and Goldstein2008; Korzekwa Reference Korzekwa, Dell and Links2008; Hasin Reference Hasin, Sarvet and Meyers2018).

In this article I examine the distinction between diagnostic categories in the classification of persistent, mild-to-moderate mood disorders in adults. The term ‘persistent’ refers to symptoms occurring most of the time for 2 years or more. Note that, conventionally, a primary diagnosis of mood disorder is not made if the patient has symptoms that are more typical of schizophrenia, substance use disorders or organic syndromes such as dementia, head injury or medical conditions.

Depressed mood means feeling sad, empty and hopeless. Anhedonia means lack of enjoyment. Distractibility means that the person's attention is too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli. Suicidality means thoughts of self-harm.

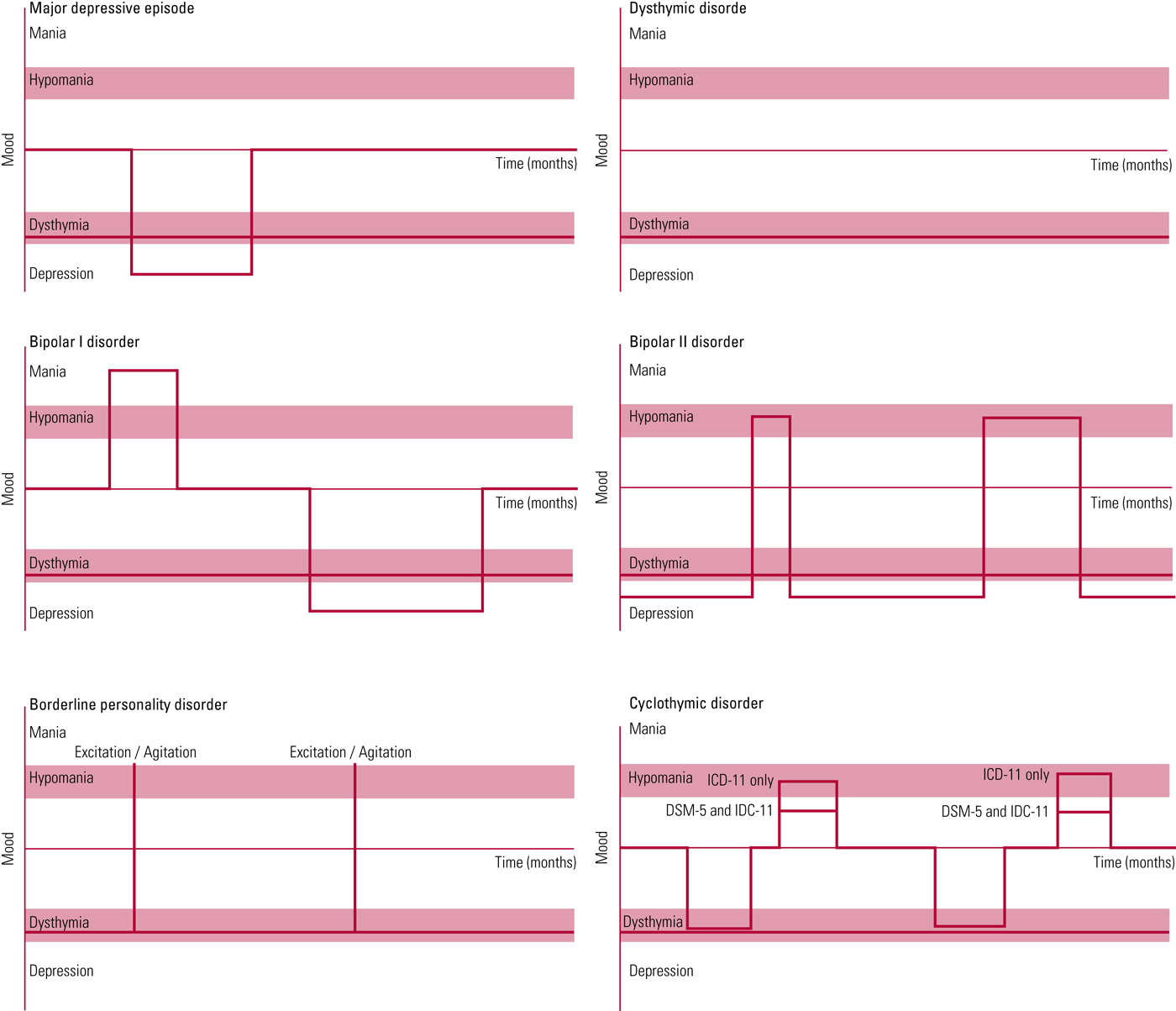

An algorithm summarising the current ICD-11 and DSM-5 criteria for differential diagnosis in persistent depression is given in Box 1; Fig. 1 shows typical patterns for each of the candidate disorders (major depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder (I and II), borderline personality disorder and cyclothymic disorder).

BOX 1 A simplified algorithm for differential diagnosis in persistent depression

Any manic episode (with ‘marked’ impairment of functioning for 7 days or psychosis)?

Yes – Bipolar I disorder

No: Any hypomanic episode (at least 4 days)?

Yes – Bipolar II disorder

No: Any intense emotional dysregulation persisting for a few hours (such as anger, panic or despair; irritability; anxiety)

Yes – Consider borderline personality disorder

No: Low mood with ‘significant’ impairment of functioning, suicidality and objective symptoms such as psychomotor agitation or retardation for 2 weeks?

Yes – Major depressive episode

No: Dysthymic disorder or cyclothymic disorder (there is no ‘significant’ or ‘marked’ impairment of functioning in DSM-5 cyclothymic disorder, although the symptoms can produce ‘significant’ impairment of functioning in ICD-11)

Notes

Figure 1 shows typical patterns for each of the disorders.

Borderline personality disorder in DSM-5 also requires symptoms such as: frantic efforts to avoid abandonment; unstable intense relationships; identity disturbance; impulsivity; suicidality; unstable mood; chronic emptiness; anger-management problems; transient stress-induced paranoid or dissociative symptoms. DSM-5 requires that symptoms begin in early adult life.

In ICD-11 personality disorder, there must be ‘substantial’ distress or ‘significant’ impairment of functioning for 2 years, with a negative view of the self or impaired interpersonal functioning (dissatisfaction with relationships or interpersonal conflict). In ICD-11, personality disorder is classified as mild, moderate or severe. Any suicidality automatically leads to a diagnosis of severe personality disorder.

A depressive episode can be distinguished from dysthymia or cyclothymia by the presence of suicidality, objective psychomotor agitation or retardation, or ‘significant’ impairment of functioning.

A manic episode can be distinguished from hypomania by ‘marked’ impairment of functioning or psychotic features (duration of symptoms is 7 days for a manic episode and 4 days for hypomania).

FIG 1 Simplified graphs of characteristic patterns in persistent mood disorders (major depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder (I and II), borderline personality disorder and cyclothymic disorder).

Clinical descriptions: ICD-11

ICD-11 was released on 18 June 2018, although it is not yet available as a full manual but only as an interactive website with coding tools (World Health Organization 2018). ICD-11 will formally replace ICD-10 in 2022.

Major depressive disorder

See the section on major depressive disorder ‘Clinical descriptions: DSM-5’ below.

Dysthymic disorder

In ICD-11 ‘dysthymia’ or ‘dysthymic disorder’ includes patients with low mood for most of the time for 2 years or longer, although the severity must not meet criteria for a depressive episode. In other words, dysthymia is a description for subsyndromal depression associated with anhedonia, impaired concentration, low self-esteem or inappropriate guilt, pessimism, disturbed sleep and appetite, and fatigue. In contrast to dysthymic disorder, depressive episodes require that there is ‘significant’ impairment of functioning, suicidality and objective symptoms such as psychomotor agitation or retardation that are observed by others and persist for at least 2 weeks. The presence of a 2-week depressive episode within a 2-year period excludes a diagnosis of dysthymic disorder. There should be no manic or hypomanic episodes (which would indicate a bipolar disorder).

In summary, ‘severe’, ‘marked’ or ‘significant’ impairment of functioning will exclude a diagnosis of dysthymic disorder but not cyclothymic disorder in ICD-11.

Cyclothymic disorder

ICD-11 describes cyclothymic disorder as a 2-year period during which an individual experiences multiple hypomanic (see the next section) and dysthymic symptoms but these episodes do not reach the threshold for mania (bipolar I disorder) or a formal depressive episode. However, the symptoms can produce ‘significant’ impairment of function. In other words, cyclothymic disorder involves a prolonged period of unstable mood with hypomanic episodes but, unlike bipolar II disorder, the periods of low mood do not reach the threshold for a formal depressive episode (for example they may not have any suicidality or objective symptoms such as psychomotor agitation or retardation). Clearly, a single manic episode would lead to a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

Bipolar II disorder

ICD-11 describes bipolar II disorder as an intermittent mood disorder with at least one hypomanic and one depressive episode (lasting at least 2 weeks, with features including ‘significant’ impairment of functioning, suicidality, and psychomotor agitation or retardation). A hypomanic episode involves several days of elated mood or irritability, overactivity or increased energy associated with other symptoms, such as grandiose ideas, decreased sleep, pressured speech, flight of ideas, distractibility, impulsivity, reckless behaviour and excitement. (The DSM-5 definition of mania or hypomania requires three or more of the listed features, although the number of symptoms is not specified in ICD-11.) Unlike mania, a hypomanic episode does not involve ‘marked’ impairment of functioning or psychosis.

The presence of a formal depressive episode (lasting at least 2 weeks, with features including ‘significant’ impairment of functioning, suicidality, psychomotor agitation or retardation) excludes a diagnosis of dysthymia, although bipolar II disorder is still a possibility. Similarly, a formal manic episode with ‘marked’ impairment of function or psychosis would lead to a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder.

As discussed later, bipolar I disorder may be a completely separate diagnostic entity to bipolar II disorder. For example, bipolar II disorder is often associated with chronic low mood over years, rather than intermittent discrete depressive episodes. The majority of treatments have been devised and tested in bipolar I disorder, rather than bipolar II disorder, although the two conditions are often treated in the same way (Benazzi Reference Benazzi2007; Wong Reference Wong2011; Hall-Flavin Reference Hall-Flavin2019).

The differentiating role of functional impairment

Clearly, the distinction between dysthymic disorder and a depressive episode can rely entirely on the definition of ‘significant’ impairment of functioning (although suicidality or observable psychomotor agitation or retardation also indicate a depressive episode). The presence of a 2-week depressive episode within any 2-year period excludes a diagnosis of dysthymic disorder. Similarly, the distinction between mania and hypomania can rely entirely on the definition of ‘marked’ impairment of functioning (although psychotic features also indicate a manic episode).

Personality disorder

ICD-11 has abandoned the categorical classification of personality disorder into clinical groups (such as dissocial, schizotypal, emotionally unstable and borderline) and replaced these with dimensional classes: mild, moderate and severe. Furthermore, the clinical criteria for personality disorder no longer require that the symptoms begin in early adulthood, provided that they have been present for 2 years.

ICD-11 describes personality disorder as 2-year period with a negative view of the self or impaired interpersonal functioning (dissatisfaction with relationships or interpersonal conflict). This may present as maladaptive or distressing ways of thinking, emotional experience (such as emotional lability and dysregulation) and dysfunctional behaviours affecting a range of situations (e.g. family life, education and work). There must be ‘substantial’ distress or ‘significant’ impairment of functioning. Distressing emotional experiences and dysregulation in personality disorder clearly have some overlap with clinical features of mood disorders. Unlike dysthymic disorder, personality disorder does require ‘significant’ impairment of functioning.

Behaviours involving significant self-harm would automatically lead to a diagnosis of severe personality disorder. There is also pervasive impairment of interpersonal functioning and relationships in people with severe personality disorder.

Personality disorder versus bipolar II disorder in ICD-11

Symptoms of personality disorder must persist for at least 2 years. Other than this, the distinction between severe personality disorder (previously, emotionally unstable personality disorder) and bipolar II disorder in ICD-11 depends on the interpretation of ‘patterns of […] emotional experience, emotional expression, and behaviour that are maladaptive (e.g., inflexible or poorly regulated)’ (World Health Organization 2018: 6D10 Personality disorder). Hypomanic episodes commonly involve symptoms such as irritability, impulsivity, disinhibition, reckless behaviour and excitement. These features can also be included in the description of ‘poorly regulated emotional expression and behaviour’ consistent with personality disorder. Hence, using ICD-11 criteria, it is entirely at the clinician's judgement whether an individual is given a diagnosis of severe personality disorder or bipolar II disorder or both.

Summary

ICD-11 fails to distinguish between chronic bipolar II disorder and personality disorder, and therefore a clinician can make either diagnosis in someone with persistent low mood for 2 years associated with any episode of emotional dysregulation, hypomania, irritability, impulsiveness, disinhibition, reckless behaviour and/or excitement provided that these persist for several days (and therefore meet the criteria for a hypomanic episode). Bipolar II disorder is depression with intermittent hypomania. Cyclothymia, in ICD-11, is intermittent hypomania and dysthymic episodes with no formal depressive episode.

Clinical descriptions: DSM-5

Major depressive disorder

Clinical features of a major depressive disorder are almost identical in DSM-5 and ICD-11. Both require a significant impairment of functioning. Similarly, a hypomanic episode does not involve ‘marked’ impairment of functioning or psychosis in both manuals. A major depressive disorder requires that symptoms produce ‘significant’ distress or impairment (for at least 2 weeks) or, alternatively, there must be a ‘markedly increased effort’ to achieve relatively normal functioning in cases of mild depression. In hypomania, the symptoms are not severe enough to cause ‘marked’ impairment of functioning and there are no psychotic features, unlike a manic episode. Symptoms should persist for at least 4 days in a hypomanic episode in DSM-5 and ICD-11.

Persistent depressive disorder

Persistent depressive disorder is the term used in DSM-5 for ICD-11 dysthymic disorder, although it also includes features consistent with a chronic depressive episode (often termed ‘depressive personality’). Persistent depressive disorder requires more than 2 years’ experience of depressed mood, with disturbed sleep or appetite, fatigue or low energy, low self-esteem, poor concentration/indecisiveness and hopelessness. A continuous 2-month period without symptoms excludes a diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder (in other words ‘the clock restarts’ after a 2-month remission).

The appellation ‘with pure dysthymic syndrome’ can be used if an individual does not meet criteria for any major depressive episode during the 2-year period. Unlike dysthymic disorder in ICD-11, a DSM-5 diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder can be reached if the full criteria for major depressive disorder have been present continuously for more than 2 years. Similarly, persistent depressive disorder in DSM-5 includes people who have suffered serious impairment of functioning.

DSM-5 recognises that persistent depressive disorder can have an early onset (in adolescence) and there is also significant overlap with borderline personality disorder. Indeed, both diagnoses can be made concurrently.

Cyclothymic disorder

The DSM-5 criteria for cyclothymic disorder are very similar to those of ICD-11 but do not require ‘significant’ or ‘marked’ impairment of functioning.

Bipolar II disorder

The diagnostic criteria for bipolar II disorder in DSM-5 are almost identical to the ICD-11 criteria, with at least one major depressive (lasting at least 2 weeks) and hypomanic episode (lasting at least 4 days). Patients tend to complain of the depressive symptoms and it may only be friends and relatives who recognise the hypomanic episodes. However, a hypomanic episode should be carefully distinguished from euthymia during a period of recovery from a depressive episode.

Bipolar I versus bipolar II disorder

DSM-5 also introduces the concept that bipolar II disorder is not a ‘milder’ form of bipolar I disorder despite that fact that, according to clinical descriptions, the primary difference is the presence of hypomania rather mania. (Mania involves ‘marked’ impairment of functioning or psychotic features.) DSM-5 reports that people with bipolar II disorder also tend to have chronic dysthymia or depression, rather than discrete episodes of depressed mood and intermittent euthymic periods, as is the case with classic bipolar I disorder.

The clinical description of bipolar II disorder in DSM-5 indicates that onset is typically in the mid-20s (although there is a significant age spread). This is comparable to the classic view that personality disorders first emerge in early adult life. Furthermore, patients may perceive hypomanic episodes as episodes of increased productivity, rather than periods of illness. However, hypomanic episodes are identified by relatives and friends, particularly when the individual become overactive, disinhibited, impulsive and reckless.

Personality disorder

Personality disorder in DSM-5 involves a pattern of experience (including both the intensity and lability of emotional experience), unusual ways of thinking about things and patterns of behaviour that persistently deviate from expected norms. These patterns are engrained and occur in multiple situations (such as family life, work and education). The symptoms have developed by early adult life and cause ‘significant’ subjective distress or functional impairment.

The term ‘borderline personality disorder’ is used instead of ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’ in DSM-5. Borderline personality disorder in DSM-5 involves a pattern of unstable interpersonal relationships, self-image and mood, with marked impulsivity. Clearly, both ‘mood lability’ and ‘impulsivity’ are typical of both bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder.

Unlike ICD-11, DSM-5 continues the tradition that personality disorder should be diagnosed only when the features have developed before early adulthood. Symptoms (outlined in Box 1) are persistent and typical of the individual's long-term functioning, and they are not confined exclusively to an episode of another mental disorder.

Borderline personality disorder versus bipolar II disorder in DSM-5

Unlike ICD-11, DSM-5 makes it clear that periods of unstable mood (‘intense episodic dysphoria [such as anger, panic or despair], irritability, or anxiety’) borderline personality disorder should last a few hours and ‘rarely more than a few days’. This is a significant distinction from ICD-11 and also helps to distinguish borderline personality disorder from bipolar II disorder (where the periods of mood disturbance must persist for at least 4 days to fulfil criteria of hypomania).

Summary

DSM-5 clearly distinguish between borderline personality disorder and bipolar II disorder, indicating that intense emotional experiences (such as anger, panic or despair; irritability; anxiety) should persist for only a few hours for the patient to meet criteria for borderline personality disorder. In the event that the symptoms of emotional dysregulation persist for more than a few hours then a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder or major depression is probably more appropriate, depending on the presence or absence of hypomanic features. The criteria for borderline personality disorder in DSM-5 are distinct from those in ICD-11 (and emotionally unstable personality disorder in ICD-10) in specifying that the emotional dysregulation typically persists for a few hours, whereas there is no specified time frame in the ICD criteria.

Discussion

Bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder have considerable overlap in symptoms and are difficult to distinguish. Around 20% of individuals with either bipolar II disorder or borderline personality disorder meet criteria for both disorders (Brieger Reference Brieger, Ehrt and Marneros2003). Conventionally, bipolar I disorder involves discrete episodes over several weeks of elevated or depressed mood with periods of euthymic mood between. By contrast, bipolar II disorder is now thought to involve protracted periods of depressed mood/dysthymia with occasional periods of hypomania. This greatly increases the diagnostic overlap between bipolar II disorder and borderline personality disorder. It is notable that both ‘dysthymia’ and ‘cyclothymia’ have been variously considered forms of personality disorder in the past. (Previously, bipolar disorders were classified as ‘Axis I’ disorders, whereas the personality disorders were ‘Axis II’ disorders (Fiedorowicz Reference Fiedorowicz and Black2010). The distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders has now been abandoned.)

Is fashion determining diagnosis?

Although research will continue to determine the prevalence and aetiology of these disorders, there are some other relevant factors that may have led to the increasing popularity of the diagnosis of ‘bipolar II disorder’ rather than ‘borderline personality disorder’. The idea that prevailing fashion may determine a psychiatric diagnosis is rather disconcerting, especially as the treatment of these disorders is radically different: personality disorders are treated with psychotherapy, whereas bipolar I disorder is treated with medication (Benazzi Reference Benazzi2007; Wong Reference Wong2011). However, there is increasing evidence that bipolar II disorder may be a separate entity from bipolar I disorder (the majority of published research has focused on bipolar I disorder) (American Psychiatric Association 2013; Hall-Flavin Reference Hall-Flavin2019).

Various reasons have been suggested for the changes in diagnostic classification and the increased tendency to diagnose bipolar II disorder in preference to borderline personality disorder, in particular stigma and labelling, medical insurance claims and the influence of the pharmaceutical industry.

Stigma and labelling

Mental disorders have been clearly shown to be extremely stigmatising (Corrigan Reference Corrigan2004; Sartorius Reference Sartorius and Schulze2005; Wessely 2016). However, a diagnosis of personality disorder is thought to be particularly stigmatising and patients often reject it (Hancock Reference Hancock2017). This would explain the reluctance to code a person as having a personality disorder and instead opt for bipolar II disorder. The perception of treatability has particular pertinence here, as many published pharmaceutical trials indicate the effectiveness of mood stabilisers in treatment of bipolar disorder, whereas the outcome of treatment for personality disorder, particularly psychotherapy, is less impressive (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2009, 2014).

Medical insurance claims

It is widely believed that US medical insurers will reimburse clients following treatment of bipolar II disorder but not personality disorders (which are held to be pre-existing conditions) (Anonymous 2012; Oberg Reference Oberg2012; Borderline Personality Treatment 2018).

Pharmaceutical industry influence

It is also noted that the treatment of bipolar disorder relies on medication, especially mood stabilisers, whereas treatment of personality disorder is largely based psychotherapy (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2009, 2014). This raises the possibility that commercial companies are promoting the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder to justify use of pharmaceutical products. The potential for financial conflicts of interest has been raised by various commentators. For example, there has been some criticism of the authors of DSM-5 as being ‘secretive’ and for failing to disclose potential conflicts of interest. Similarly, over half of DSM-5 task force members had some financial ties with the pharmaceutical industry (Carey Reference Carey2008; Cosgrove Reference Cosgrove and Lisa2012; Welch Reference Welch, Klassen and Borisova2013). This would give a financial incentive to encourage use of the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder rather than personality disorder and this may have influenced the manual's authors.

A note on rapid cycling and comorbidity

ICD-11 and DSM-5 define rapid cycling as the occurrence of at least four major depressive, manic, hypomanic or mixed episodes during the previous year in a person with a diagnosis of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder (Coryell Reference Coryell, Endicott and Keller1992; Maj Reference Maj2006). Rapid cycling is known to be more common in bipolar II than in bipolar I disorder (Bipolar UK 2019). There remains controversy as to whether people with borderline personality disorder should also be diagnosed with bipolar II disorder, particularly rapid cycling or ultra-rapid cycling disorder (Kramlinger Reference Kramlinger and Post1996; Post Reference Post, Altshuler and Leverich2006; Mohring Reference Mohring2019). Many patients fulfil criteria for both disorders. However, the distinction is typically based on the presence of enduring features of borderline personality disorder, especially repeated self-harm, identity disturbance and unstable relationships, usually established in early adult life (Mohring Reference Mohring2019).

Conclusions

DSM-5 states that any intense experiences of emotional dysregulation in borderline personality disorder should persist for no longer than a few hours, whereas ICD-11 is less proscriptive. Persistent emotional dysregulation (irritability, impulsiveness, disinhibition, reckless behaviour and excitement) for a few days would lead to a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder. A depressive episode can be distinguished from dysthymia by the presence of suicidality, objective psychomotor agitation or retardation, or ‘significant’ impairment of functioning. A manic episode can be distinguished from a hypomanic one by ‘marked’ impairment of functioning or psychotic features. The term ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’ has been replaced by ‘borderline personality disorder.’

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 In ICD-11, the ICD-10 diagnosis ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’ has been largely replaced by:

a histrionic personality disorder

b cyclothymia

c borderline personality disorder

d narcissistic personality disorder

e exhibitionism.

2 ‘Persistent depressive disorder’ in DSM-5 includes several related disorders, but not:

a dysthymic disorder

b cyclothymic disorder

c bipolar II disorder

d borderline personality disorder

e schizoaffective disorder.

3 Suicidality in DSM-5 is most associated with:

a major depression

b dysthymic disorder

c cyclothymic disorder

d Othello syndrome

e hypomania.

4 Symptoms required for ‘borderline personality disorder’ in DSM-5 do not include:

a frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

b unstable intense relationships

c suicidality

d pathological jealousy

e unstable mood.

5 Common symptoms of hypomanic episodes in ICD-11 do not include:

a irritability

b impulsivity

c catonia

d reckless behaviour

e excitement.

1 c 2 e 3 a 4 d 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.