INTRODUCTION

Questions of racial inequality in policing haunt our current moment. Many efforts to understand this problem focus on racial profiling, homing in on the practices of individual officers (Correll et al. Reference Correll, Park, Judd, Wittenbrink, Sadler and Keesee2007; Alpert et al. Reference Alpert, Dunham and Smith2007; Legewie Reference Legewie2016). These micro-level interactions are indeed important—police-citizen encounters initiate entry into the criminal justice system, expose citizens to the state’s capacity for coercive force, and shape perceptions of police legitimacy (Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014; Epp et al. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014). Yet, officers’ inappropriate use of race in decision making is notoriously difficult to conclusively isolate (Engel et al. Reference Engel, Calnon and Bernard2002; Goff and Kahn Reference Goff and Kahn2012). And racial profiling is but one potential source of racial inequality in policing outcomes. For instance, studies at the meso-level reveal that widely legitimated institutional practices can produce racial disparities, even in the absence of the racial intent of officers (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014; Armenta Reference Armenta2017). This study further investigates dynamics of racial inequality in policing through an analysis of the interaction between meso-level organizational arrangements and the macro-level structural environment.

I focus specifically on the relationship between the police agency, as an organization, and the surrounding socio-spatial urban landscape. Organizations both respond to and further constitute their environments (McQuarrie and Marwell Reference McQuarrie and Marwell2009). In racially segregated cities, this environment includes longstanding inequalities between neighborhoods. The police react to the exigencies of these differences—for instance, in claiming a crime control mandate, they orient activities toward unevenly distributed criminal and social problems—but the police can also further produce differences. The aggregated activities of officers shape the experiences and meanings associated with place: whether an area feels secure or dangerous, cared for or neglected. This productive capacity is an underexplored facet of the role the police play in addressing, maintaining, or amplifying racially unequal social structures.

Police departments are increasingly likely to treat different places in different manners. As strategic innovations emphasize tailored, local approaches to problems across the city, police executives embrace a proliferation of differentiated goals and tactics (Greene Reference Greene, Horney, Peterson, MacKenzie, Martin and Rosenbaum2000; Skogan Reference Skogan, Weisburd and Braga2006; Cordner Reference Cordner, Reisig and Kane2014). Spatially decentralized approaches enable district captains and police officers to respond to neighborhood-level concerns. If such problem-solving is done in a democratic fashion, it may have the potential to redress historic racial inequalities by giving local communities control over the governance decisions that affect them (Stuntz Reference Stuntz2008; Simonson Reference Simonson2017). But the mitigation of inequalities is not the only possible outcome of a local approach. Differentiated treatment can also reinforce symbolic meanings and unequal experiences attendant to segregation, a process I describe as place-consolidation.

This study documents a case of place-consolidation using a police department’s efforts to pursue local approaches through a redistricting reform and subsequent special initiatives. The redistricting aligned police district boundaries with the city’s stark racial segregation boundaries, intentionally opening the door for divergence in policing styles. I trace the logic and consequences—both intended and unintended—of efforts to address discrete district-level problems. This case allows me to ask: how do the police respond to segregated environments in an era characterized by proliferating and differentiated activities? And how do these responses further shape urban space in ways that can produce racial consequences? To answer these questions, I draw upon several sources of data, including public documents, interviews with decision makers and stakeholders, one year of ethnographic observation of police work in two districts, and data on 911 calls for police service. In highlighting the responsive and productive capacities of the police, I show more generally how organizational practices construct and reconstruct place and—in a racially segregated context—how they make and remake group differences. I suggest that these processes can be analytically clarified through scholarship on the ties between organizations and their environments.

THE ORGANIZATION-ENVIRONMENT NEXUS

Police agencies are prototypical organizations: clearly bounded entities characterized by rules, procedures, and hierarchy; oriented toward a set of goals; and engaged in activities that have outcomes for their members, the organization itself, and for society (Hall Reference Hall1999, 30; Bordua and Reiss Reference Bordua and Reiss1966). While the term “the police”Footnote 1 is often used to describe individual officers, it can also refer to the broader organizational entity of the police agency. Focusing on the police as an organization brings attention to the mutually constitutive relationships between the urban environment, organizational goals and structures, and the activities of individual officers. Several insights from the sociology of organizations clarify these relationships and link existing findings from the policing literature.

First, the surrounding environment “constitutes, influences, and penetrates organizations” (Scott Reference Scott2004, 5). Organizations are open systems that respond to competing and varied demands from local communities and broader technical, political, economic, and cultural fields (Selznick Reference Selznick1949; Dimaggio and Powell Reference Dimaggio and Powell1983; McQuarrie and Marwell Reference McQuarrie and Marwell2009). Organizations incorporate formal structures, in part, to gain legitimacy and resources from this institutional environment (Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977; Suchman Reference Suchman1995; Dimaggio and Powell Reference Dimaggio and Powell1991). For police agencies, relevant pressures can flow from sources including the network of criminal justice institutions, the local political field, and the social ecology of the city (Klinger Reference Klinger2004). The evolution of policing strategy is one manifestation of organizational response to these environments (Kelling and Moore Reference Kelling and Moore1988; Reiss Reference Reiss1992; Crank Reference Crank1994). Differences in how policing occurs across geographic space is another. Neighborhood characteristics like crime levels, racial composition, and poverty rates have been shown to influence the degree and kind of police activity in an area (Smith Reference Smith1986; Terrill and Reisig Reference Terrill and Reisig2003; Sobol et al. Reference Sobol, Wu and Sun2013). The geographic distribution of economic and political interests, on the one hand, and social and criminal exigencies, on the other, shapes organizational action.

Second, organizational activities are not mere responsive, they play an “independent role in the production, reproduction, and arrangement of urban social relations, neighborhood conditions, and individual outcomes and identities” (McQuarrie and Marwell Reference McQuarrie and Marwell2009, 247). Organizations distribute resources, and create meanings in ways that further shape the surrounding environment (Perrow Reference Perrow1970; Hall Reference Hall1999; McQuarrie and Marwell Reference McQuarrie and Marwell2009). This insight is often overlooked in urban sociology, where organizations are seen as entities that derive from the city, rather than entities that further generate the city (McQuarrie and Marwell Reference McQuarrie and Marwell2009). Police departments share in this capacity to craft the character of space. As they regulate the kinds of people and activities found in particular areas, the aggregate activities of police officers produce and reproduce understandings of how orderly, secure, dangerous, or criminal discrete geographies can be (Herbert Reference Herbert1997; Beckett and Herbert Reference Beckett and Herbert2009; Rios Reference Rios2011). In addition to responding to the environment, organizational activities actively construct it.

Finally, these responsive and productive activities are not always consistent within an organization or aligned with its stated strategic goals. Discrepancies between goals and activities arise from the multilevel and dual character of organizations. Complex organizations are multilevel in that they are comprised of hierarchical and differentiated departments, work groups, and individuals (Rousseau Reference Rousseau1985; Hall Reference Hall1999). They are dual in that norms and values infuse organizational action, giving organizations both a formal, strategic dimension and an informal, normative dimension (Selznick Reference Selznick1949; Dimaggio and Powell Reference Dimaggio and Powell1991; Scott Reference Scott2004). These features can intersect to produce subunits with distinct normative or cultural characteristics. Subunits may differ from each other and their activities may depart from the organization’s strategic aims. Organizations, thus, incorporate activities that are only “loosely coupled” to their stated goals.

Klinger (Reference Klinger1997) applies an organizational perspective in an account of how police behavior can vary across physical space. Klinger focuses on the importance of the police district as a territorial subunit. While officers often cross the boundaries of individual beats within a district, they rarely cross district boundaries. As a consequence, officers in the same district form a stable work group that shares geographically delimited responsibilities and activities. As crime and other social problems vary across districts, work groups develop normative expectations—about workload, “normal” crimes, the deservingness of victims, and levels of cynicism—that shape the vigor of police action. This theory draws attention to how the mid-level subunit of the district mediates the relationship between the environment and the norms and behaviors of individual officers.

This project builds upon work examining the ties between organizations and their environment to investigate the responsive and productive capacities of the police in the city. It centers the above insights: organizations respond to their environments, organizations also further constitute and produce their environments, and organizational activities can have both intended and unintended consequences. This investigation brings further attention to an understudied source of racial inequality in policing: the police organization’s power to shape place. Policing not only responds to the environment, as Klinger describes; it further creates the environment. Often, these processes occur within a set of dynamics common to contemporary urban policing: decentralizing approaches, embedded in differentiated and unequal urban landscapes.

DECENTRALIZATION IN A SEGREGATED CONTEXT

Strategic innovations in policing increasingly emphasize tailored responses to geographically discrete problems. Previously, the incident-based response model sought centralized and routinized policing through preventive patrol and rapid response to emergency calls (Kelling and Moore Reference Kelling and Moore1988). But these tactics had little effect on crime and generated professionally remote police officers in an era of mounting public fear and tense relationships with minority communities (Kelling et al. Reference Kelling, Pate, Deikman and Brown1974; Kelling and Moore Reference Kelling and Moore1988; Spelman and Brown Reference Spelman and Brown1981). To address the limitations of a standardized approach, strategies like community-based and problem-oriented policing encourage localism and differentiation. They embrace a wide vision of the police function—one that extends beyond crime control to address problems of order, quality of life, and fear—and they encourage a proliferation of tactics, all in service of enhancing police responsiveness to distinct neighborhoods and communities (Kelling and Moore Reference Kelling and Moore1988; Greene Reference Greene, Horney, Peterson, MacKenzie, Martin and Rosenbaum2000; Skogan Reference Skogan, Weisburd and Braga2006; Cordner Reference Cordner, Reisig and Kane2014).

This focus on local and differentiated environments encourages territorial decentralization. While a department’s overall strategy and priorities may be determined at the executive level, departments that embrace community-based strategies push additional decision-making power down to mid-level district captains or commanders. As Skogan (Reference Skogan, Weisburd and Braga2006) summarizes, “departments do this in order to encourage local solutions to locally defined problems, and to facilitate decision-making that responds rapidly to local conditions” (37). Decentralization makes the district an even more important organizational subunit: captains have greater autonomy to develop priorities, choose tactics, and allocate district-level resources (Hassell Reference Hassell2006). Officers within a district not only encounter different work environments, they may be expected to prioritize particular problems and respond with fundamentally different tactics.

Proponents see a local approach as one way to address the continuing realities of urban inequality. In many cities, the police agency responds to racially segregated environments characterized by vast differences in social conditions (Massey and Denton Reference Massey and Denton1993; Charles Reference Charles2003). Patterns of poverty, unemployment, and crime disproportionately concentrate in minority neighborhoods (Sampson and Lauritsen Reference Sampson and Lauritsen1997; Krivo et al. Reference Krivo, Peterson and Kuhl2009; Lichter et al. Reference Lichter, Parisi and Taquino2012). Other concerns for the police—like trust and perceptions of legitimacy, and likelihood of cooperation or crime reporting—also vary meaningfully by race (Tyler Reference Tyler2005; Weitzer and Tuch Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005; Desmond et al. Reference Desmond, Papachristos and Kirk2016). A decentralized approach invites closer integration into local communities, enabling officers to develop long-term relationships and collaborate with residents around specific concerns (Skogan Reference Skogan, Weisburd and Braga2006). In an ideal form, localism can make policing a more democratic enterprise; citizen participation and public deliberation become the locus of governance decisions (Stuntz Reference Stuntz2008; Kleinfeld Reference Kleinfeld2017). This model can hypothetically confront legacies of racial discrimination, as historically marginalized communities develop “the most profound reimaginings of how the system might be truly responsive to local demands for justice and equality” (Simonson Reference Simonson2017, 1609). Such a ground-up approach has the potential to redress patterns of institutional neglect and problems of trust, creating a more equitable city.

THE POSSIBILITY OF PLACE-CONSOLIDATION

But the mitigation of inequalities between neighborhoods is not the only possible outcome of a decentralizing and local approach. Though many departments claim to adopt community policing, collaborative efforts are often relegated to a subset of officers or realized through a smattering of tactics (Skogan Reference Skogan, Fridell and Wycoff2004). Bureaucratic structures and practices persist, creating organizational impediments to robust community-based efforts (Skogan Reference Skogan, Fridell and Wycoff2004; Mastrosfki et al. Reference Mastrosfki, Willis and Kochel2007; Mastrofski and Willis Reference Mastrofski and Willis2010; Morabito Reference Morabito2010). Ultimately, a police department considers and responds to the entire jurisdiction, making it likely that powerful groups can influence priorities and resource allocations. As a consequence, police departments can institutionalize local approaches that reflect and reproduce existing socio-spatial inequalities. Indeed, this may seem like a more probable outcome when considering the historic role of the police in maintaining a status quo social order (Hadden Reference Hadden2001; Williams and Murphy Reference Williams and Murphy1990; Bass Reference Bass2001; Wadman and Allison Reference Wadman and Allison2004). Legacies of enforcing the laws of racialized institutions—from slavery to the war on drugs—call into question the democratic potential of localism and invite investigation into how contemporary strategies might instead reproduce racial hierarchies.

I suggest that the police can reinforce citywide social divisions when they act in relation to inflated stereotypes of differentially valued neighborhoods. In addition to its material realities, segregation corresponds to symbolic ideas of place. Dominant stereotypes contrast crime-ridden, disorderly, and violent inner cities to white, more affluent neighborhoods with “‘good’ schools, safe streets, and moral values to match” (Kobayashi and Peake Reference Kobayashi and Peake2000, 394; Delaney Reference Delaney2002; Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2007; Brown Reference Brown2010). These symbolic dichotomies elevate the perceived criminality and disorder of marginalized neighborhoods (Quillian and Pager Reference Quillian and Pager2001; Sampson and Raudenbush Reference Sampson and Raudenbush2004), while glossing over the sociability, collective efficacy, and use value that residents often find within them (Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2007). Symbolic ideas also present better-off neighborhoods as the most promising sites for enhancing exchange value. Further investment in these sites drives uneven development and exacerbates spatial inequalities (Levine Reference Levine1987; Clarke Reference Clarke1992; Mele Reference Mele2013). Dominant ideas of place are those that affirm stereotypes and reinforce hierarchies of worth.

As an organization responds to and shapes its environment, it can amplify or subvert dominant symbolic ideas. For instance, as associations in marginalized neighborhoods advocate for public goods—fair housing, equitable educational opportunities, better city service provision, and the like (Logan and Molotch Reference Logan and Molotch1987; Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2007) —they seek investments that counter long-standing patterns of material neglect and symbolic devaluation. In contrast, organizations reinforce dominant meanings when they act in relation to stereotypical representations, further generating associated experiences and meanings. In the case of policing, saturating segregated, “high-crime” neighborhoods with police “virtually ensures that Blacks (or other non-Whites) will be observed, questioned, and arrested at rates that substantially overstate objective racial differences in offending” (Ousey and Lee Reference Ousey and Lee2008, 331) This pattern has played out in analyses of the intersecting spatial and racial dynamics of investigatory traffic stops and stop-and-frisk practices (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014; Fagan et al. Reference Fagan, Braga, Brunson and Pattavina2016; Huq Reference Huq2017). Treating an area as criminal overgeneralizes the presumption of criminality based merely on where people are and what they look like.

I extend these insights by tracing the pathways from symbolic ideas of place to organizational actions to amplified place-based inequalities. I describe this process as place-consolidation. Place-consolidation reinforces or intensifies an existing status quo social order, rooted in historic racial discrimination and persisting structural inequalities. The police agency—like other organizations—is a powerful entity that is constrained by place, on the one hand, and working to constitute place, on the other. I explore how the police respond to an unequal landscape and how their responses further shape the trajectories of neighborhoods. Examining the interplay between the structural features of the city and the organizational activities of the police generates an important insight: urban inequality is not a static phenomenon. It is actively renegotiated and reconstituted as the experiences and meanings associated with segregated neighborhoods are challenged, maintained, or amplified.

METHODS AND DATA

This study examines local policing approaches undertaken by the River CityFootnote 2 Police Department. The River City police operate in a segregated urban environment. The city has a close ratio of black to white residents, who constitute a majority of the population. It also includes a growing Hispanic population and a small Asian population. Racial segregation overlaps with patterns in neighborhood rates of poverty, employment, educational attainment, and incarceration in ways that demonstrate marked racial disparities. The police must respond to the exigencies of this landscape. Like many agencies, the River City police sought to do so by institutionalizing local approaches. The department redrew the boundaries of several police districts to follow neighborhood lines and crime patterns as part of this effort. This redistricting aligned police district boundaries with the city’s racial segregation boundaries. The police subsequently developed several district-level special initiatives focused on discrete place-based problems. These reforms both identified district-specific strategic priorities and changed the work environments of patrol officers. As initiatives and practices developed on this basis, they revealed underlying ideas of place and further shaped the character of diverse neighborhoods.

In approaching this case study, I gathered and analyzed data in a manner informed by the process tracing method. Process tracing can identify theoretically generalizable mechanisms by linking the intervening processes that lead to particular outcomes within a historical case (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005). Process tracing examines how events unfold by identifying key political actors and providing rich description at various points in time (Tansey Reference Tansey2007; Collier Reference Collier2011). Developing this account requires analysis of both the explanations that decision makers give for their actions and the relationship between these beliefs and actual behaviors (Jervis Reference Jervis2006; Vennesson Reference Vennesson, Donatella and Keating2008). This style of comparison is facilitated by triangulating amongst several sources of data (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2005; Vennesson Reference Vennesson, Donatella and Keating2008). In this case, I identified and interviewed key architects of policing strategy in River City, and I used interviews and public documents to describe the official logics of change. I compared these official logics to on-the-ground practices through ethnography and analysis of 911 calls for police service. Overall, this project draws upon four distinct data sources.

First, I use public records,Footnote 3 including: media accounts; video footage, minutes, and agendas from public meetings; and other reports and evaluations of the police department. This body of data highlights several important facets of the reform and its aftermath. It reflects the official organizational logic driving the redistricting and subsequent strategies, as communicated to other powerful stakeholders. For instance, the Chief of Police presented the redistricting before two governing bodies: the Safety Committee of the City Council and the Civilian Review Board, a public entity that oversees the police department’s administration. Video footage and minutes from these meetings capture the stated motivations for the reform and the process by which it was approved. In addition, documents like news articles and evaluations represent widely circulating public endorsements and critiques that flesh out the implications of the police department’s strategic choices.

I delve further into motives and interests through in-depth interviews with thirty-seven decision makers and stakeholders who either participated in or were affected by the redistricting and strategies in its aftermath. I first sought to access those who had most directly driven the reform. I shortly found that it was perceived as a top-down, technocratic initiative—attributed to the Chief of Police, though reviewed by the City Council and approved by the Civilian Review Board. I interviewed fourteen representatives from these agencies, including two police executives directly responsible for the decision. I asked respondents to provide a narrative of the redistricting: to describe the goals of the reform and the process of implementing it, and to evaluate its impacts. These interviews further captured the interests, stakes, and pressures driving the police department’s initiatives. I embed these organizational goals within a broader landscape of interests through additional interviews with twenty-three representatives of agencies serving varied neighborhoods across the city. I recruited stakeholders who had a relationship of some kind with the police department, identifying them through materials in which the police listed collaborators (Doc. 02). These interviews focused on evaluations of the redistricting, local policing initiatives, and police service more generally. Including community representatives with a stake in policing allows me to compare the symbolic ideas centered by the police agency to other possibilities.

Next, I examine the development of local policing strategies through thirteen months of ethnographic observation in two of the most transformed police districts: District A and District B. I selected these districts because they emerged as central in the accounts of decision makers and because they were substantively interesting. These districts were relatively comparable in geographic size and population. They had similar proportions of residential land use: approximately 80 percent of properties in both, with 50 percent owner-occupied in compared to 40 percent in District B (Doc. 09). Despite these similarities, the districts diverged considerably along demographic lines. District A had the highest proportion of white residents of any of the city’s districts—over 80 percent—while District B had the highest proportion of black residents, at over 75 percent (Doc. 09). The average assessed property value in District A was more than three times that in District B. While District A included middle-class residential neighborhoods, the downtown, and several commercial and entertainment corridors, District B contained some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. These two districts thus represented poles of the city’s segregation; they also typified the dynamics underlying the logic of the department’s reforms.

Comparing these districts ethnographically allows me to trace, first, how the goals of the local policing manifested in district-level priorities and resource allocations and, second, how these priorities and resources structured the daily work of officers. These districts operated in ways consistent with Klinger’s (Reference Klinger1997) description. Rates of interdistrict dispatch were extremely low;Footnote 4 officers rarely crossed over district boundaries for assignments, but often traversed wide swaths of their own district’s geography over the course of a shift. Police personnel saw districts as semi-autonomous subunits characterized by distinct imperatives and constraints. To describe each district as thoroughly as possible, I sought breadth in the activities and individuals I observed. In total, I conducted 75 ride-alongs, approximating five hundred hours of observation, between August of 2014 and August of 2015. I interviewed district leadership and observed across the chain of command; I conducted several ride-alongs across all shifts and geographic sectors in both districts; and I observed all facets of line officers’ work—patrol officers responding to calls for service, community-based initiatives, and special deployments or units that only operated within each district.

During ride-alongs, I aimed to capture both the nature of work and officers’ perspectives on it. Riding with an officer for an eight-hour shift permitted a great deal of talk, which ranged from casual conversation to semi-structured interviewing. Through this, I learned about officers’ career histories, experiences within the district, perceptions of social and criminal problems, and comparisons between their district and other parts of the city. In addition, officers often explained their decision making to me. This talk revealed how the police describe and make sense of their work and provided an opportunity to compare perceptions to situated actions. As I observed, I took jottings that I expanded into typed fieldnotes when I returned home. These fieldnotes captured all the activities that the officer engaged in and paraphrased much of the conversation that we had. Ethnographic fieldwork provided an in-depth picture of how officers’ routines and attitudes were shaped by district-level priorities and the unique conditions of their work environments.

Finally, I further contextualize officers’ workload and practices using data on calls for police service provided by the police department. This data set captures every call to which a squad was dispatched. It includes the location of the call, its priority, the assignment type, the primary unit that responded, the time, and the ultimate disposition of the assignment. Though I do not extensively use the calls for service data in this Article, I include select descriptors that characterize the workload in District A and District B.

These many data sources provide several in-depth snapshots of policing over time, allowing me to draw linkages between them. To trace intervening processes, I used “diagnostic evidence” to investigate the consistencies and gaps between official rationales, actual organizational practices, and their consequences (Collier Reference Collier2011, 823). For instance, after identifying the police department’s stated strategic priorities within each district, I explored the extent to which these goals were realized in the work of patrol officers, the metrics of police response, and the perspectives of other stakeholders. I further examined the connections between organizational logics and on-the-ground activities through iterative data collection and analysis, for instance, I coded interviews and public documents for mentions of various symbolic ideas of place. I developed additional codes from this initial analysis to apply to fieldnotes; parent codes marking symbolic ideas corresponded to subcodes labeling when these constructs emerged in officers’ descriptions of their priorities, concerns, and routine activities. Based on this analysis, the following sections present an overview of the logic of the redistricting and emergent policing strategies in River City. I then examine how policing practices subsequently shaped features of space—in both intended and unintended ways—as the police pursued local approaches.

RESPONDING TO PLACE: A LOCAL APPROACH

The redistricting was the brainchild of the River City Police Department’s Chief of Police, who was brought in from outside of the department for his reputation as a strategic innovator in the broader field of policing (News 05). Prior to the Chief’s arrival, the incident-based response model had reigned in River City. The police department focused on “calls for service staffing,” which centered response time as the key indicator of police performance (Doc. 12). A policing scholar described the department at the time as “estranged from its community, underperforming, and out of touch with latest developments in policing nationally” (Doc. 12). The Mayor saw the appointment of the new Chief as a “bold action” (News 05). And the Chief immediately pursued reforms to move the department away from the incident-based response model. Instead, he promoted “proactive” strategies that incorporated elements of community-based and problem-oriented paradigms (Doc. 12). The department’s strategic innovations were united in their goal of facilitating tailored responses to local, neighborhood-level issues.

The Chief proposed the redistricting as a means of bringing a key administrative unit into alignment with this new approach. During the meeting before the City Council’s Safety Committee, he contrasted existing district boundaries to the proposed boundaries, first describing the initial design of the districts: “A lot of people worked very hard to draw the current district boundaries using classical formulas. And the classic formula for dividing up districts was, historically, let’s equalize the workload so every district has roughly the same number of calls for service.” Yet, this method had produced unintended consequences. The Chief went on:

Sometimes that resulted in district lines being drawn right through the middle of neighborhoods and separating them from each other. It didn’t take into consideration geography or topography … and it didn’t always take into consideration crime trends and patterns. We have some district lines right now that, quite literally, run right in the middle of a [crime] hot spot, so that half of that hot spot is one district commander’s responsibility and half is the other’s. (Vid. 01)

By splitting neighborhoods and crime problems, the initial district boundaries undermined the efficiency of police response. District commanders had to coordinate activities or risk divergent approaches to the same issues.

By contrast, the new district boundaries would streamline police-community relationships and problem-solving efforts at the local level. The Chief described: “Our new proposed boundaries are entirely built on the notion of keeping coherent neighborhoods—with similar problems—together for a stable policing presence” (Vid. 01). In an interview, another police executive further explained this logic: “A single district commander and a team from that district would be familiar with those types of problems and could work cohesively with multiple partners from across that district to try to come up with solutions for the problems that were identified.” With greater decentralization, district leadership could focus on local concerns, be they gang activity in high-crime districts or garage burglaries in low-crime districts (Vid. 01). The redistricting was, thus, an important facet of the department’s embrace of a differentiated approach to policing, consistent with popular strategic innovations in the field.

The redistricting proposal found widespread buy-in. The Chief assured the Public Safety Committee that staffing would reflect the volume of work endogenous to each district. Many officers would retain their same squad area, even if the squad area was now in a different district. This would facilitate ongoing relationships between officers and local residents. As the meeting concluded, a Councilman from a district with a large African American population noted, “I support this one hundred percent … this is a much better way to tailor policing in these respective neighborhoods than how we were doing it in the past” (Vid. 01). Another member of the City Council noted in an interview, “you want different models [of policing] —but not different levels of service—in different neighborhoods.” The motion to approve the new district boundaries carried unanimously during the Civilian Review Board meeting (Doc. 04). The idea of adapting policing styles to respond to heterogeneous problems appealed to diverse stakeholders. District captains would have more decision-making responsibility and could develop tailored initiatives.

SYMBOLIC IDEAS: ECONOMIC VALUE AND VIOLENCE

Yet, the power to define both problems and responses ultimately remained within the police agency. And the symbolic ideas of place the agency drew upon corresponded to dominant political and economic interests in the city. Police administrators explained that the new district lines largely followed crime patterns, concentrating crime hot spots in some districts, including District B, while others, like District A, included generally low-crime areas. The key aims of this separation were captured in a statement by the Chief during the Safety Committee hearing. He explained:

We know that—just as we have a moral obligation to reduce crime in those neighborhoods afflicted by violence—we also have a responsibility in this city to be stable and visible and present in low-crime areas where we have middle-class and working-class people in stable neighborhoods. We recognize that we have to make them feel safe and make them feel service. (Vid. 01)

With this, the Chief made it clear that the department was preeminently concerned with service in the new low-crime districts, on the one hand, and addressing violence, on the other.

The importance of low-crime neighborhoods lay in the widely-circulating symbolic idea of their economic value to the city. Two important kinds of places—middle-class residential neighborhoods and commercial corridors—were now predominately in District A. Stakeholders saw middle-class residential neighborhoods as an important source of tax revenue for the city. They felt compelled to be responsive to the needs of these residents, lest they consider leaving. The redistricting sought to redress an issue, characterized by the Chief during the Safety Committee meeting, in which “some districts have very quiet neighborhoods and high crime neighborhoods, and the people in the quiet neighborhoods feel like they’re not policed enough because everybody’s on the other side of the district” (Vid. 01). A City Councilman representing such a quiet area reemphasized the significance of these neighborhoods: “If we lose taxpayers here, then we don’t have the finances to support crime efforts—it just goes down in total” (Vid. 01). The new district boundaries intended to facilitate more responsive service and enhanced visible patrol in these quieter neighborhoods.

In addition to protecting existing economic resources, the police also embraced an active role in cultivating further investment. As in many post-industrial cities, the Mayor of River City promoted downtown revitalization as a primary strategy for growth (Doc. 10). The police sought to enhance perceptions of safety in downtown commercial corridors to attract tourism and development. In an interview, a police official explained:

One of the things you really want to maintain in a big city is a police presence downtown, even though downtown is safe—it’s got one of the lowest crime rates of any neighborhood in the city. But the bulk of all tourism occurs in the downtown area. And the perception that people have when they travel to a big city is that downtown isn’t safe.

In emphasizing the capacities of the police to cultivate perceptions of safety, the department participated in efforts to further economic growth. These efforts aligned with understandings in the broader political field. The downtown was seen as the “heart” of the city, according to the Mayor, and as its “single most important economic resource,” per the downtown business improvement district (News 06; Doc. 13). In further elevating the economic value and potential of District A areas, the police responded to and institutionalized dominant understandings of place.

In District B, the emphasis on crime also represented a dominant understanding of place. In creating high-crime districts, the redistricting specifically centered the symbolic idea of violent crime. That the violence in parts of District B constituted a problem for residents and the police was not a divisive proposition. A community organizer described the consequences of crime for neighborhood residents: “The people that live around the park don’t like to go on their porch or let their kids play in the park because, often, there’s young men in the park gambling or smoking weed or doing drugs, or there’s shootings and all that kind of stuff.” The police department took up these concerns. A police executive noted that District B contained “the most violent crime areas in the city” and explained that the department transitioned to a hot spot focused policing in the process of “evolving from a rapid response to a proactive, problem-solving type strategy.” He elaborated: “We know that there are very small, locally very clustered areas of crime, and those became our focal point.”

Yet, the emphasis on violence glossed over other attributes of District B neighborhoods. Countervailing symbolic ideas emerged during interviews with community organizers, business improvement district managers, and neighborhood association representatives who worked and lived in District B. They marked as important both the assets of these areas and the fractured trust between the police and minority communities. For instance, respondents saw great development potential in their neighborhoods, but indicated that there was little political will to realize it. A representative from a community development agency described, “the same kind of thing you see downtown, we’d like to see that kind of energy develop here. We have the footprint. What we need to do is garner the desire from government officials, folks who control the money and want to invest back over here on a larger scale.” Stakeholders also described problems of trust and legitimacy. One community organizer explained, “people just don’t trust the police. There are a lot of people that have been abused by police or have been told a narrative that police are wrong.” Later, she continued, “[the work] is building the trust, but also giving people the capacity to be able to voice things and be heard.” These narratives suggested policing priorities that would move beyond the focus on violent crime to incorporate activities to focused on building stronger police-community relationships, enhancing feelings of security, and cultivating the development potential of District B neighborhoods.

In sum, the police department ultimately identified problems consistent with dominant understandings of place. Police executives prioritized efforts to sustain economic stability and growth in already better-off neighborhoods. In other parts of the city, the focus on violence prevailed, despite residents’ more varied concerns. This organizational response to the broader field of political and economic power shaped subsequent place-based activities. In redefining discrete work environments and identifying overarching priorities, the department set goals and crafted constraints that laid the foundations for divergent policing styles. These differences in policing ultimately consolidated aspects of River City’s neighborhood inequality.

DISTRICT A: CONSOLIDATING THE CITY’S ECONOMIC ENGINES

Local policing approaches in District A revolved around preserving and enhancing the district’s commercial corridors and middle-class neighborhoods. Police officials indicated that the redistricting aimed to change patrol practices and strategic priorities. One described: “Having the downtown and [other District A neighborhoods] together in a district … it made sure that police were equally patrolling.” This executive also noted, “now we’ve got almost all of our major entertainment zones contained within one police district.” He cited a specific model for policing entertainment corridors and explained, “we’ve been able to apply that type of strategy across the entire District A.” Because District A experienced comparatively little crime, officers could devote attention to order maintenance and service provision functions. As the police committed resources to these efforts, they amplified the material and symbolic distinctions that positioned District A’s neighborhoods as exceptionally valuable and worthy.

Service Provision in Middle-Class Neighborhoods

The redistricting intentionally separated the quiet neighborhoods of District A from the criminal problems in District B. This was reflected in the disparities in volume and type of calls for service that the districts experienced. During the fieldwork period, fewer than half as many calls came into District A compared to District B. And these calls were of different natures. Only 10 percent of District A calls were designated “priority one,” Footnote 5 indicating that they involved life threatening conditions. Common criminal issues in District A included property crimes like locked vehicle entry, damage to property, and theft (Doc. 09). By contrast, over five times as many calls involving life threatening situations came into District B, and these calls constituted about one-third of the call volume. The Chief had indicated that disparities in district-level workload would be addressed through personnel allocations. And District B did have more officers than District A: approximately 138 during the fieldwork period compared to seventy-four. Yet, these allocations did not fully address the vast differences in volume of work. Indeed—as revealed by analysis of the calls for service data—disparities in workload across neighborhoods had existed prior to the redistricting and widened in its aftermath.

These differences were reflected in several measures. For instance, District A officers responded to fewer assignments per shift, on average. While officers in District B neighborhoods had taken more assignments to begin with, the gap between districts widened as the mean number of assignments further decreased in District A after the redistricting (Figure 1).Footnote 6 Subsequently, officers in District A spent a smaller proportion of each shift on scene handing assignments—averaging approximately 160 minutes on scene compared to 250 minutes in District B, during the approximate fieldwork period. Ethnographic observation of patrol work in District A revealed the distinctive practices and understandings that corresponded to this work environment. Generally, District A officers had ample opportunity to attend to citizens’ concerns, even if they were of a more minor nature.

FIGURE 1. Average number of assignments per day, per squad

Two sets of practices characterized service provision in District A. First, officers provided prompt and thorough responses to citizens’ calls for service. During ride-alongs, patrol officers suggested that there was not less work in District A, the work was just different than in other districts—citizens demanded prompt response, investigation, and follow-up. As well-connected residents of the city, they had the power to pass information along to local officials or police executives. Several officers made comments along the lines of: “People here are one phone call away from the Chief [of Police].” One officer showed me an email complaint about loitering that a woman had sent to him, with the District Captain and a City Council representative copied on the exchange. Officers obliged in response to these pressures. Many officers felt that working in the district necessitated a discrete set of skills that they likened to “public relations” or “people skills.” They described attending to the concerns of residents with care, due to the leverage that citizens could wield.

Second, because they spent less time handling assignments, District A officers had opportunities to patrol through neighborhoods and provide the visible police presence that residents desired. They engaged in other preventive tactics as well—checking in with businesses to discuss their concerns, enforcing traffic safety through stops, and patrolling commercial corridors on foot. During one ride-along, the officer was dispatched to a single assignment, which was cancelled before he arrived on scene. He spent his shift conducting traffic safety stops and a foot patrol along a popular corridor of restaurants. Officers explicitly tied this preventive work to the goal of creating the visible presence that residents wanted. Collectively, preventive tactics sought to maintain order, enhance informal social control, and develop closer ties between the police and residents in the district.

These activities—enabled by the comparatively low volume of calls in District A—reinforced the perception that the district’s neighborhoods were worthy and valuable. In accounting for their service practices, many officers invoked the idea of the deserving taxpayer: the citizen who directly contributed to the city’s economic health and its ability to fund the services provided by the police. During one ride-along, the officer patrolled along an avenue lined by some of the city’s most expensive homes. He indicated that residents liked to see the police patrolling, even though there were few crime problems in the area. He cited the huge property taxes these homeowners paid and mused, “people say they shouldn’t get better police service, but that’s how my salary is paid.” These factors—abundant time and resources for patrol, politically empowered and demanding citizens, and the sense that police service was both deserved and appreciated by residents—reinforced officers’ emphasis on responsive and thorough service practices within District A.

Police executives elevated the symbolic idea of the economic value of District A’s middle-class and more affluent neighborhoods during the redistricting. This idea subsequently defined both the geographic reach and strategic priorities of officers’ work. As the police responded to the exigencies of their environment and embraced the dominant meanings associated with them, they reinforced disparate service provision practices. Compared to other parts of the city, District A residents experienced and perceived increasing investments of public safety resources, intended to make their neighborhoods more livable, orderly, and safe. A neighborhood association representative described police response in her area prior to the redistricting: “You could call them—and somebody might eventually show up after a couple of hours—about a loud party or something. And I swear, I believe one officer actually said, ‘look, lady, you don’t have anything going on over here; we’ve got problems and you don’t.” She continued, “[The redistricting] was just something that the police department did, and I’m so glad they did … it’s been better ever since.”

Order Maintenance in the Downtown

The police department also pursued strategic goals related to River City’s downtown revitalization. The agency participated in efforts to enhance perceptions of safety through the Entertainment Corridor Deployment. The Entertainment Corridor Deployment sought to prevent crime, not only for the sake of the current establishments and their local patrons, but to further attract tourists and developers to the city (News 01). During a public hearing, the Captain who had initially created the deployment described the economic logic behind it: “We needed to develop a policing model that would effectively police the night time economy, knowing its connection to the daytime economy” (Vid. 02). He went on to explain that his greatest concern was a shooting during the weekend that could deter tourism activities like conventions. He elaborated: “Knowing what the media does with that, knowing that they tend to proliferate this, ‘it’s not safe downtown,’ that’s my fear …. And that perception proliferates through and we don’t get the conventions” (Vid. 02).

The downtown area attracted weekend revelers from across the metro area. During the Entertainment Corridor Deployment, the police department allocated overtime pay for additional officers, who patrolled the district’s most bar-dense streets and intersections. As observed during ride-alongs, officers regulated large crowds, checked on taverns, intervened in disputes, and generally acted as a visible deterrent presence. The deployment could entail formal law enforcement, in which officers cited or arrested disorderly individuals or fined bars that served minors or operated over capacity. However, punishing taverns and their patrons was not the main objective of the initiative. The deployment’s strategy encouraged officers to cultivate collaborative working relationships with bar and restaurant owners (News 02). If establishment owners were less concerned that the police would take a punitive approach, they would be more likely to communicate about chronic and emergent problems.

Stakeholders in the area recognized and appreciated this problem-solving focus. A Councilman representing an area with a prominent entertainment corridor described in an interview:

You could just come in and crack down and just come in force in [the entertainment corridor] and ruin everybody’s good time. And you’d solve a problem, but you’d create a new one, which is now we’ve lost an entertainment district. So, you need a kind of precision there, or a different kind of focus. We’ve got that now.

Beyond appreciating the police department’s intention, stakeholders attributed improvements in the downtown to the deployment. A local article cited the example of loitering and indicated that the police had worked with the bars to move loiterers off the sidewalks until the issue had diminished. It also described the Chief’s assertion of marked crime reduction in the downtown area: aggravated assault, thefts of vehicles, and thefts from vehicles each dropped between 40 percent and 50 percent (News 02). The deployment both shaped the character of the corridors and improved perceptions of the police by positioning law enforcement as responsive and collaborative resources, rather than punitive enforcers.

And the city saw economic investments consistent with the goals of the Entertainment Corridor Deployment. The downtown business improvement district reported over three billion dollars of completed public and private projects, with another two billion dollars of investment in ongoing projects, over a ten-year period (Doc. 13). It also described over three billion dollars in tourism sales and an estimated $240 million generated by the nightlife economy in a single year (Doc. 13). Though the contributions of the police could not be parsed from other aspects of this broad push for investment, stakeholders saw their relationship with the police as important to realizing their goal of growth. The Executive Director of a business improvement district in the downtown explained:

Downtown is extremely visible, and in terms of our police leadership and city leadership, we have the ear of those leaders, because we represent so much of the city’s tax base. We represent very powerful corporate entities…. It’s really important to the city’s tax base that downtown is a great place to do business and live.

These connections between politics, policing, and the city’s economy highlighted the role of the police in the larger project of downtown redevelopment in which many other powerful stakeholders participated.

In many regards, policing activities in District A represented a successful institutionalization of local, problem-oriented strategies. The police recognized the distinct interests and needs in middle-class neighborhoods and the downtown. And they addressed concerns of residents, business owners, and political stakeholders by tailoring resources and initiatives to focus on service provision and order maintenance. In seeking to protect and develop the area’s economic resources, policing in District A consolidated the character of the city’s better-off neighborhoods. While this was not a problem in and of itself—indeed, many in the district expressed satisfaction with the police—the department’s organizational priorities ultimately reinforced relational and hierarchical understandings of place. This was revealed in the contrasting activities and meanings that took hold in District B.

DISTRICT B: CONSOLIDATING CRIME CONTROL IN THE INNER CITY

Though some of the neighborhoods in District B were adjacent to the downtown and middle-class residential areas of District A, many saw them as a world away. The symbolic idea of violence defined the character of the district. During an interview, the Captain of District B explained, “District B is pretty unique compared to other districts … everything that we do has to be geared towards: how can we have a positive effect on violent crime?” Though other stakeholders had referenced different ideas of how the neighborhoods of the district could be treated, special initiatives primarily focused on intervening in violence. They did so in alignment with the Chief’s proactive strategy, specifically through use of investigatory stops. As the police dedicated resources to proactive patrol, service provision flagged. These dynamics reinforced existing inequalities as they criminalized District B neighborhoods and residents, on the one hand, and fostered the perception that these neighborhoods were not valued and served, on the other.

Crime Control in Violent Hot Spots

Broadly, proactive policing aims to prevent crime before it happens, though tactics to accomplish this goal can vary. In River City, the Chief’s proactive strategy folded data-driven hot spots policing into the department’s goal of community policing. After identifying small geographic areas where crime concentrated, captains deployed police officers to initiate encounters with citizens in the form of investigatory traffic stops and pedestrian stops (also known as subject stops, Terry stops,Footnote 7 or stop-and-frisk). The Chief positioned these stops as part and parcel of community-based policing efforts, describing: “The cops get familiar with the comings and goings the neighborhood and get to know who’s who in the neighborhood, and even though we stay active, the key is to retain neighborhood support for those efforts” (Vid. 03). Officers were trained to engage professionally and respectfully during stops, and they were encouraged to often give verbal warnings rather than citations. Theoretically, this method of proactive patrol could also provide opportunities for positive police-citizen interactions.

Investigatory stop practices ballooned in River City, primarily in the districts that had been drawn around crime hot spots. Four years after the initiation of the proactive strategy, a police department report indicated that traffic stops had increased from approximately fifty thousand per year to almost one hundred ninety thousand and subject stops increased from fourteen thousand per year to over sixty thousand citywide (Doc. 05).Footnote 8 In subsequent years, District B had the highest rate of traffic stops and pedestrian stops of any of the city’s districts—seventy-one traffic stops per one hundred drivers and 3.4 pedestrian stops per one hundred residents. By comparison, the rates in District A were thirty-one traffic stops per one hundred drivers and 2.8 pedestrian stops per one hundred residents (Doc. 06). These differences were driven, in part, by within-district resource allocations. During the fieldwork period, District B leadership assigned sixteen officers of the 138 to special units tasked with intervening in violence and other crime related to gang and drug activity. These officers relied on proactive tactics and spent most of their shifts conducting stops. District A had no similar units, and traffic stops there were primarily oriented around traffic safety enforcement.

Initially, the proactive approach corresponded to crime control gains. In a meeting with community representatives, the Chief presented data correlating the rise in stops to a 25 percent reduction in violent crime and a 20 percent decrease in property crime in the four years following the initiation of the proactive strategy (Vid. 03). The Chief framed the experience of being stopped as a trade-off for the safe neighborhoods such tactics promoted; he was quoted in a local article, explaining that communities—and innocent people—would accept the inconvenience of respectfully conducted stops for a safer environment (News 03). Many stakeholders initially understood this logic. The city’s NAACP Chapter President issued a statement indicating that the agency trusted the police department’s intent to promote livable neighborhoods and accepted policing strategies in high-crime communities at face value (Doc. 07). Police executives cited a dramatic reduction in external complaints about the police since the Chief took office to assuage concerns that stop practices were controversial or divisive (Doc. 05).Footnote 9 At its heart, the proactive strategy sought more equitable places: the goal of reducing crime would make District B neighborhoods safer and more livable, bringing them closer to the neighborhoods in District A.

But this goal was not achieved and, eventually, the proactive strategy ended up amplifying inequalities in River City. It did so, first, by failing to have long-term effects on violent crime. Compared to a low in 2011, 2015 saw a 41 percent increase in violent crime; the absolute number of incidents was just above the number from when the Chief had started his term (Doc. 11). The proactive strategy continued apace, justified on the basis of these persistent criminal problems. But accounts of rising crime in River City—which ranged from shifts in the drug market and gun laws to structural explanations implicating poverty to environmental design factors like street lighting—suggested complex causes that the proactive strategy could not adequately address.Footnote 10 Crime continued to concentrate in neighborhoods historically afflicted by violence; the police department’s proactive approach could not redress longstanding inequalities in neighborhood conditions.

Second, targeted stop practices in high crime districts subjected residents of predominately black and Latino neighborhoods to the surveillance and social control characteristic of the broader phenomenon of over-policing. Indeed, based on ethnographic observation of specialty units in District B, investigatory stop practices transcended the geography of hot spots and instead stretched to the boundaries of the district. Proactive officers would often begin their shifts in designated hot spot areas, but eventually—out of boredom or the desire for a change of scenery—they would move out of these small areas and patrol in other parts of the district. Consequently, drivers throughout the district were likely to be stopped. In an interview, a community organizer who worked in District B described the aggressive use of proactive tactics: “[The police are] pulling right up with the mind frame of, ‘violence, drugs, guns—I’m coming ready.’ And half the time, these people are just really hustling, trying to survive … it looks like it could be something violent, but it really ain’t.” He captured the common sentiment that this manner of policing overgeneralized the presumption of criminality, extending it well-beyond the individuals actually engaged in violence.

Ultimately, the proactive strategy heightened long-standing racial tensions in policing. Assertions of racial profiling and bias in stop practices began circulating in the public sphere. A few years after the stop strategy began, a local newspaper reported that black drivers were seven times more likely to be stopped in River City than white drivers. Hispanic drivers were five times more likely to be stopped (News 03). Later surveys of citizens revealed a racial gap in satisfaction with the police, in addition to a relationship between experiencing a stop and having negative views of the police (Doc. 14, Doc. 15). Several years after the proactive strategy began, concerns over racial discrimination culminated in a class-action lawsuit alleging that stops in River City were unconstitutional—that the police subjected black and Latino residents to stops with no legal basis (Doc. 08). This lawsuit reflected a mounting critique of the proactive strategy. For instance, the initial goodwill of the NAACP was replaced by calls for the police department to put a new strategy in place to address stop-and-frisk (News 07). Coalitions of faith and advocacy groups developed and began pressing for police reform (News 08).

The Chief continued to defend the proactive strategy through the language of place and crime, explaining that the police targeted areas where residents were most victimized (News 09). He maintained that stops had been proven to reduce crime in several categories and linked the proactive strategy to the department’s “moral duty” to address violence (News 09). The Chief emphasized that the police were responding to the realities of an unequal city, characterized by historic overlaps between neighborhood disadvantage, crime, and segregation. While few might deny these realities, the growing resistance to the proactive approach revealed fissures in understandings of how to address them. Indeed, in observed meetings between the police and community groups, District B residents often requested tactics like those used in District A, for instance, increased visible preventive patrol and more beat officers. Yet, the police ultimately retained the power to define strategic responses. And the department chose a controversial strategy by relying primarily on investigatory stops. Though some studies find that proactive tactics can reduce crime (see Koper and Mayo-Wilson Reference Koper and Mayo-Wilson2006 and Braga et al. Reference Braga, Papachristos and Hureau2014 for reviews), others question the utility of aggressive stops, drawing attention to their role in driving racial disproportionality and undermining trust in the police (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014; Tyler et al. Reference Tyler, Fagan and Geller2014; Huq Reference Huq2017). In this case, many saw the proactive strategy as exacerbating the over-policing of black neighborhoods.

Service Provision in District B

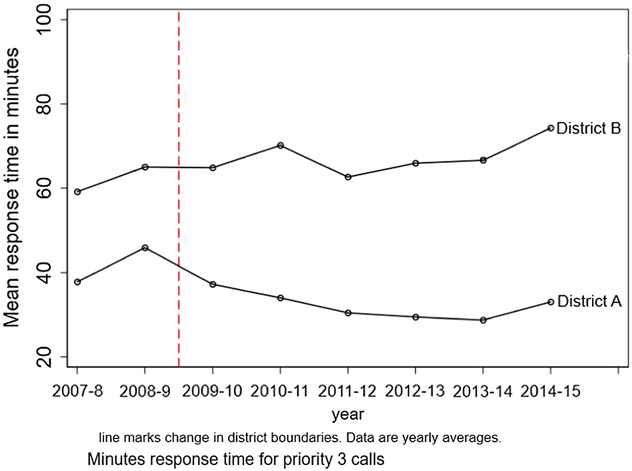

The attention to violent crime had other rippling impacts in District B. Namely, residents perceived flagging police response to calls for service. As described earlier, District B patrol officers took more assignments and spent more total time on assignments per shift, on average, than District A officers. Response times in District B were also slower to lower priority calls. In the aftermath of the redistricting, response times to priority three calls had increased slightly in District B, while decreasing in District A (Figure 2). These patterns were related to the strategic emphasis on proactive patrol. A news article published a few years into the Chief’s term described lagging response times across major call categories. In the article, the Chief defended devoting district-based resources to the proactive strategy versus response to calls for service. He asserted that he would accept a small increase in response times for the decreasing crime associated with the proactive approach (News 04). These patterns of resource allocation affected the high-crime districts where proactive patrol was a dominant strategy.

FIGURE 2. Average response time for ‘priority three’ calls

And, while attention to violent crime was a central priority for the police, most residents in District B had concerns similar to those of residents in District A. They wanted the police to provide thorough service, address quality of life issues, and maintain order in their neighborhoods. As a former district Captain explained in an interview:

Your average citizen living in a challenged district is never going to be the victim of a homicide, never going to be a victim of a non-fatal shooting, never going to be a victim of a street robbery. So, the most frequent complaints that you get are on issues of disorder, like loud music, disrespectful neighbors that aren’t taking care of their property, that have teenagers that run amok and create disorder.

Residents in District B worried that they suffered neglect in service provision. In an interview, a neighborhood association representative described his sense of the district’s priorities: “If it’s not a shooting, you probably won’t get anybody to come out. If they do come out, it’s an hour to sometimes the next day. They’re overwhelmed with what they’ve got right now.”

Based on ethnographic observation, the disparities in response times reflected the workload pressures stemming from the volume and seriousness of calls that came into the district. District B patrol officers felt that they operated in a distinctly resource-constrained setting—that they had to “do more with less,” as multiple officers put it. Officers encountered frequent reminders of the workload: when all patrol squads were on an assignment, the list of pending calls would begin to grow; sometimes, officers would be pulled from an assignment they were currently on and sent to a higher-priority call. The police indicated that this work environment was exhausting. As one officer described: “Sometimes you just want five minutes after an assignment to breathe.” Another officer characterized the feeling of patrol work by explaining: “You’re just running around like a chicken with its head cut off, taking assignments all day long.”

Officers suggested that the volume and nature of work made it necessary to minimize the time spent on less serious calls. As one put it, the police could not “take time on the stupid stuff because there are usually ten or so calls pending and something serious might come up at any point.” Minimizing was seen, in part, as an imperative given the constraints that officers experienced. Yet, such attitudes also reflected officers’ sense of the deservingness of the district’s residents. Many officers framed the criminal and social problems in District B in ways consistent with more broadly circulating ideologies of worthiness. One officer described, “the police service goes to all the people who don’t pay for it. The city bends over backward for the scrubbier side of town. If we don’t do it, nobody else will.” Officers scornfully invoked the idea that the state had to compensate for the shortcomings of lazy, manipulative, and irresponsible people. Patrol officers’ daily experiences reinforced a sense of social distance from the citizens in District B. Though proponents of local policing see continuity in officers’ deployments as a potential advantage, in this case, it was also a source of potential burnout and cynicism. Officers’ routine work—the violent reputation of the district, pressures to handle assignments efficiently, and exposure to conflict of all kinds—reinforced the mentality that thorough service in District B was difficult to provide and was not necessarily deserved.

Interview respondents from District B saw disparities in police service as a symptom of how their neighborhoods were devalued and deprioritized. As a director of a business improvement district mused: “The people here get shitty response times and yet you look at somebody out in [District A]. If their garage gets broken into, [the police] are probably there in twenty minutes. Why is that?” Another respondent described her perception of the city’s investments: “Of course they love the downtown. But our central city neighborhoods, we’re like stepchildren.” Some respondents described changes in service provision as directly related to the redistricting. One respondent described her neighborhood, which had formerly been in District A, but was now in District B: “After the redistricting, residents said it became the neighborhood that was the better ones of District B … so less resources were coming to our neighborhood. I’d say a common complaint was slow response times, a lack of police presence.” With the police agency focused on District A, and District B leadership focused on violent crime, neighborhood residents described their everyday problems as overlooked. Thus, they felt that another longstanding feature of urban inequality—the under-policing of black neighborhoods—had become more pronounced.

In sum, local approaches to the problems of District B unexpectedly exacerbated longstanding racial tensions in policing. The police agency responded to a real problem in its focus on violent crime; that this was a priority for both residents and the police is not surprising. But the combination of tactical decisions and resource constraints ultimately thwarted the goal of making District B neighborhoods more livable, orderly, and safe. Reliance on investigatory stops overgeneralized symbolic ideas of criminality and disproportionately subjected residents to intrusive policing. At the same time, patrol officers handled a large and stressful workload, and they described the necessity of working efficiently to cope. These activities and understandings positioned District B neighborhoods as dangerous and less deserving, amplifying dominant ideas of place and consolidating corresponding inequalities.

CONCLUSION

River City is but one case. And some of the dynamics described here are likely exceptional. For instance, the dissonance between the department’s purported goal of community policing and its continued reliance on aggressive proactive stops seems to reflect the rigid tactical commitments of this particular Chief, rather than a probable outcome of local policing. Strategies in River City developed through complex and contingent pathways, and in response to a particularly segregated and unequal landscape. Yet, in spite of these limitations, this case highlights an important set of mechanisms that can emerge as the broader field of policing continues to embrace decentralized and differentiated approaches to varied problems across the city. While the democratic potentials of local strategies and their benefits for historically marginalized communities may exist, they are not predetermined outcomes in the community policing era.

As this case shows, in responding to the surrounding environment, the police organization risks reinscribing symbolic ideas that affirm stereotypes of hierarchically valued neighborhoods. Policing is embedded in many fields and the decisions of police executives reflect pressures from other city agencies, local politicians, economic and civic groups, and the media, amongst other sources. Dominant interests and ideas within these fields are like to penetrate the police organization. If the police agency ends up setting priorities and structuring activities in relation to stereotypical ideas of place, then policing can consolidate the character of unequal neighborhoods; officers’ collective actions can produce experiences and shape meanings consistent with the status quo social order of segregation. This process of place-consolidation unfolded in River City, as the police department identified the economic value of predominately white, middle-class neighborhoods and the violence of predominately black neighborhoods as central distinctions. These ideas motivated the redistricting reform and outlined the contours of subsequent policing styles. Police administrators have an increasing array of goals and tactics to choose from. And their decisions can vary in the extent to which they are truly community-based or problem-oriented. In this case, differentiated strategies—defined by district initiatives and mediated by district-level resources—amplified racialized disparities in service provision and social control. Avoiding such outcomes in the future will not merely require targeting processes internal to the police organization. This case suggests the necessity of deeper transformations to the surrounding institutional fields that motivate and constrain organizational action.

I have suggested that place-consolidation is an outcome of an underexplored source of racial inequality in policing: the relationship between the police organization and the surrounding urban environment. And an organizational perspective usefully clarifies several dynamics observed in this case. It reveals how the police agency can respond to and impact the urban landscape in both anticipated and unanticipated ways. As the department strived to enhance service and cultivate perceptions of safety in District A, the police further crafted the trajectories of neighborhoods. The multilevel and dual character of organizations contributed to outcomes in this case. The redistricting redefined a central subunit of police work and, within these work environments, distinct priorities and normative expectations developed. Some of these were aligned with the organization’s overarching goals—for instance, in the thorough service that District A officers could provide and felt citizens deserved. Others, like the workload pressures and minimizing practices described by District B officers, reflected a growing inequality rooted in a tension between district-level priorities and resources. Efforts to understand the varied sources of racial inequality in policing can benefit from further attention to the organization-environment nexus.

Most broadly, this case suggests several insights into how organizations might mitigate, maintain, or amplify urban inequality. It shows that the production of spatial, and racial, difference requires acts of constitution and reconstitution. Segregation is not a static phenomenon; it is dynamically produced through the organizational and day-to-day construction of the symbolic and material qualities of unequal neighborhoods. These processes are fundamentally relational. Organizational priorities and resource allocations are determined by acts that partition and define the entire city, often overlaying race and class geographies with hierarchical ideas of worthiness. Finally, urban inequality is driven by processes that occur across multiple levels of social organization. The macro-level context of the urban environment informs meso-level organizational arrangements, which themselves structure individuals’ micro-level experiences, practices, and subjective interpretations. In turn, everyday activities define the experiences and meanings associated with place, further crafting the environment itself. Together, these findings shed light on the constitutive capacities of organizations and their important role in shaping the racial inequalities attendant to urban life.