Introduction

Nonfaculty Clinical Research Professionals (CRPs) often manage multiple clinical research projects simultaneously while ensuring protocol integrity. Though the PI is ultimately accountable, project management is the CRP’s responsibility [Reference Sather and Woodin1]. Compromised understanding of interpersonal communications skills can confound study management and threaten participant safety.

The Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency (JTF) Harmonized Core Competencies framework for the Clinical Research Professional defines professional competency for managing clinical research. The JTF deliberations described eight domains and identified cognitive competencies within each domain [Reference Sonstein, Seltzer, Li, Silva, Jones and Daemen2]. As major research universities reorient training around the JTF competency framework [Reference Brouwer, Hannah, Deeter, Hames and Snyder3], training programs are expected to direct attention toward professionalism and competency in clinical research activities.

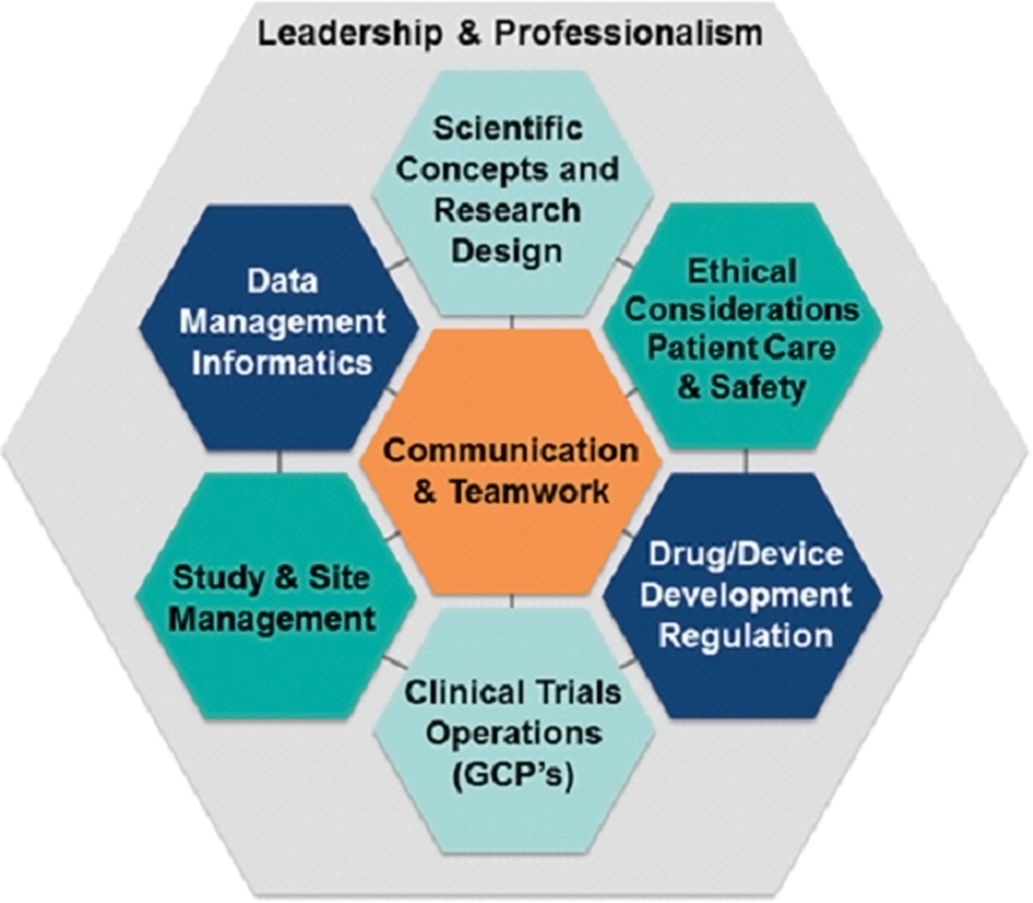

The Wheel of Competencies illustration (Fig. 1), representing the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency framework, represents CRP competencies sequentially clockwise around a circle containing eight competency domains. The domains consist of multiple items, each representing behavioral categories further divided into increasing competency skill levels. Relevant to our study are behaviors associated with Domain 8: Communication and Teamwork. This study probes Domain 8 through an exploratory investigation into CRP perceptions of competent vs. contentious communication in a singular CTSI workplace.

Fig. 1. Wheel of Competencies illustration, from the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency, showing eight domains of professional competency.

Methods

Participants

A call for participation was emailed to 70 CRPs employed at a large university in the southeastern United States. A total of seven CRPs (7 = female, 0 = male) participated in a focus group interview representing the areas of Emergency Medicine, Cancer Research, Health Outcomes, Dental Practice, Anesthesia, and Endocrinology. The fields of practice included community settings, as well as inpatient and outpatient clinics. Participants titles included Research Navigator, Research Project Specialist, Assistant Director of Study Coordination, Research Coordinator, RN Research Nurse, and Clinical Research Manager. At least two participants held national certifications in Clinical Research Coordination, and three were licensed registered nurses. Educational status ranged from BS through PhD with three MPHs and one RDH represented. There was a wide range of experience in the group, from 2 to 20 years practicing as CRPs. All participants previously attended a luncheon discussion on communication in clinical research with both researchers. Participants were previously known to one author.

Data Collection

Informed consent was obtained and a 90-min focus group was then conducted. The semistructured interview was held on a weekday with lunch provided as incentive. Open-ended questions (Appendix) were designed to elicit participants’ experiences during times of perceived competent vs. contentious communication.

Data Analysis

The interview was transcribed, verified, cleaned, and deidentified. Data were coded and analyzed using emic open and axial coding and constant comparison. Specifically, the data were independently coded and the researchers convened regularly to compare, discuss, and modify emerging codes and themes to reach consensus agreement. To verify results, participants were sent a copy of the findings and invited to respond anonymously to a brief survey containing open- and closed-ended questions aimed at obtaining participants’ degree of agreement with the findings; all responses (n = 4) confirmed full agreement with these results.

Results

Findings suggest participants intimately connected contentious communication with interpersonal and intrapersonal conflict, emotion, uncertainty, and stress. Specifically, participants described three general communication-related stressors.

Communication-Related Stressors

The discussions revealed several communication-related sources of workplace stress and frustration, namely, task/role confusion, email communication, and emotion.

Task/role confusion

Participants reported feeling frustrated by changing and/or lack of clear roles and described themselves as “wearing multiple hats.” They described a work environment often containing some degree of confusion as to the expectations for their own tasks/roles, as well as those of others. Participants find themselves questioning, “Who’s in charge? Whom do we contact for X?” (CR5) and report “telephone/email run-around” (TL7) as a common workplace frustration. Task/role confusion is attributed, in part, to frequently changing procedures, policies, and internal structure.

Email communication

Participants reported email, phone, and face-to-face (FtF) as their primary channels of work-related communication and recognized differences in communication between channels. Most notably, email was mentioned in conjunction with problematic decoding of messages and blurring of the workday.

Decoding

Participants reported less confidence in their ability to decode messages, especially message tone, when the message is sent through email vs. other channels (i.e., phone or FtF). One participant stated:

Email is just so different and it’s kind of hard. I mean, are they throwing in an explanation point there because they are making their point? Was that intentional or not, you know? It’s hard to read through the lines. (CR7)

Participants also perceived significant differences in tone of email messages vs. the tone of FtF messages of specific individuals. That is, they recalled interactions with people whose email communication they perceived as “mean” and “rude” (CR9), whereas the FtF communication with those same people was perceived positively.

Blurred workday

The second frustration of email relates to the perception of a blurred workday. Some participants reported an internal pressure to engage work-related communication tasks, specifically email, during off-hours. They described behaviors, such as waking up late at night to check email, often accompanied by a mental dialog to weigh the urgency of the message and immediate course of action (e.g., respond or wait until the next morning). In retrospect, participants recognized the “absurdity” of such behavior and described it as acting “like a crazy person” (ER3), despite being subject to its lure.

Emotion

The theme of emotion is evident among responses involving interactions with others, particularly when having difficult conversations with (1) patients and their families and (2) coworkers and research teams.

Patients and their families

Interactions with patients and/or their families are often wrought with emotion. Many of the patients with whom our participants interact face terminal diagnoses, and participants identified fear as a common emotional state of many of the patients and their families. Patients and family members may also be “very tense, anxious. Sometimes even angry, frustrated” (TL9). Additionally, participants reported feeling uncomfortable when tensions arise between patients and physicians, stating feeling “awkward” (UR4) and “trapped” (TR10) within a contentious encounter.

Staff and research teams

Perceived conflict is a communicative source of work-related stress in interactions with staff and research teams. Participants reported defensiveness as an obstacle to competent communication. They further recognized the importance of their own communication skills to help manage emotion but do not always know how to go about accomplishing that:

When I'm having to keep after staff that maybe they're not meeting expectations, that can be emotional because they get defensive immediately and do not accept the feedback you're giving, or they cry or they yell or they just walk out of the office. And it’s trying to manage that conversation on how to actually help them improve, not just that “you're doing all these things wrong.” (ER12)

Interactions with researchers were described as “a landmine of emotions” (TR16). Participants recognized that researchers are highly invested in and protective of their studies. The CRPs in our study felt that their role is to help the researchers but believe that the researchers see them as gatekeepers, or decision-makers with the power to set and control policies and rules. They reported feeling a recurring need to convince researchers that “We’re on your side” (UR13).

Discussion

Participants indicated a clear understanding of the function and scope of communication in conducting clinical translational research. Stories elicited about competent vs. contentious workplace interactions revealed strong association between conflict and stress. Our CRPs expressed a desire to improve communication skills, particularly with respect to competent email communication and managing conflict and emotion. Findings are discussed below as they relate specifically to uncertainty and emotional labor (EL).

Uncertainty

Uncertainty underlies many of the workplace stressors revealed in this study. First, our finding that email is perceived as a particularly confounding medium is consistent with extant knowledge on email’s low media richness. Media richness refers to the amount of communication cues a medium can transmit, such that higher media richness (e.g., FtF communication) occurs in channels transmitting more communication cues than those with lower media richness [Reference Daft, Lengel and Trevino4]. Generally, the lower the media richness, the greater the potential for message uncertainty.

Containing minimal communication cues, messages sent via email can increase uncertainty, and therefore stress, during encoding and decoding. Research suggests receivers of email communication tend to misjudge the emotions of the sender and inaccurately assess negative emotions as hostile [Reference Kato, Akahori, Cantoni and McLoughlin5]. Further, unfamiliarity can exacerbate uncertainty. When encoding messages to unfamiliar receivers, for example, senders can feel uncertain about identity management and competent message production.

Perceived expectation to communicate professionally can further increase uncertainty and stress related to message production. Specifically, email’s asynchronicity and editability provide time and ability to mull over messages to a greater degree than in FtF interactions [Reference Erhardt, Gibbs, Martin-Rios and Sherblom6]. Although, having more time to construct and revise messages can be beneficial, some people devote an exorbitant amount of time and anxiety on the task. Additionally, email’s persistence and replicability may lead to communication apprehension and can heighten perceived stress.

Consistent with findings on mediated communication in work contexts [Reference Chesley7-Reference Stich, Tarafdar, Cooper and Stacey9], email’s asynchronous nature can also create the experience of a “blurred workday.” The ability to access email via smartphones further exacerbates urges to work during off-hours, even without direct instruction from employers to do so [Reference Madden and Jones10]. Evidence suggests employees feel pressure to respond, believing the sender will know the message was received and ignored [Reference Middleton and Cukier11]. Thus, uncertainty surrounding expectations to attend to work-related communication during off-hours can create stress and may be directly related to fears associated with identity management and job preservation.

Additionally, in moments of perceived conflict, participants described feeling uncertain as to the proper course of action. When tensions arise, CRPs need skills to navigate their immersion in the unique culture of clinical research and to enact competent communication in this context. Neglecting the importance of discerning how to differentiate competent from noncompetent communication is a serious limitation and can create uncomfortable tensions, as well as serious risks for participant safety and data integrity.

Uncertainty management behaviors

Theories of uncertainty management and reduction suggest people may seek information to alleviate cognitive dissonance [Reference Berger and Calabrese12–Reference Brashers14]. Participants’ primary information seeking behaviors were direct and indirect perception checking. Indirect perception checking took the form of observation, specifically watching what others do to seek information about cultural/situational norms and expectations. Although direct perception checking occurred, it is done so through indirect questioning; specifically, participants seek information by asking for input about (1) message encoding/decoding, (2) task-role confusion, and (3) off-hours work expectations from people other than the message source. Concerning uncertainties stemming from email communication, participants recognize the benefit of email’s asynchronous nature to provide time for perception checking. However, when synchronous interactions are perceived as lacking the benefit of time or appropriateness for direct perception checking, observation becomes a primary information seeking behavior. The overall use of indirect behaviors suggests participants are motivated to seek information to reduce uncertainty but are hesitant to engage in overt information seeking behaviors, such as directly asking for clarification from a superior (e.g., in the case of task-role confusion) or from the message sender. This may, again, be related to concerns associated with professional identity management [Reference Miller and Jablin15].

Emotional Labor

Whether interacting with clients or working with team members and coworkers, participants described work-related communication centering on emotion management and EL. Broadly defined, EL is the management of one’s own emotions in order to influence others’ emotions in the course of one’s job and is directly related to emotional intelligence, or the ability to recognize and manage emotion in oneself and others. EL occurs when employees are expected by their employers to manage emotion in the workplace, and it is situated within jobs requiring synchronous interaction with others, production of an emotional state in others, and some degree of employee adherence to emotional expectations [Reference Hochschild16].

Our participants are mindful of the high-emotion environments in which they work and of both explicit and implicit expectations to manage their own and others’ emotions within those environments. The idea of employer/job expectations adds to the stress associated with EL. This management may be a process of individuals making sense of personal and group behavior via socially constructed understandings Erikson would describe as a convergence of group values and ideals into one’s own self [Reference Erikson17]. The perception checking and observational strategies mentioned by our participants lend support to this claim.

Emotion and stress management

Data analysis revealed our participants employ strategies to manage emotion and stress in themselves and in others. Participants identified environmental manipulation as a strategy for regulating emotion both in themselves and in others during difficult conversations, recognizing its benefit of increasing one’s sense of personal balance. In light of EL, environmental manipulation in this way is related to Hochschild’s [Reference Hochschild18] cognitive emotion work.

As a nonverbal communication cue, one’s personal space not only communicates things about that person to others but also has the potential to impact self and others. Scholars have investigated the impact of environmental manipulation in the workplace [Reference Wells19,Reference Carrere and Evans20], specifically with respect to emotion and stress management. Our participants acknowledged manipulating their environments not solely to manage their own emotions but also as a strategy to influence their communication partners’ emotions, specifically to make them feel more comfortable and relaxed. Consistent with territory research suggesting neutral spaces can buffer power imbalance, some participants discussed deliberate choices to schedule meetings in neutral, safe, or relaxing spaces.

During off-work hours, participants engage in behaviors that increase positive affect as a method of offsetting the negative affect experienced at work. Listening to enjoyable music on the drive home, spending off-hours with friends and loved ones, and engaging in pleasurable activities, for example, are all strategies for building positive affect reserves and maintaining work–life balance. Furthermore, these types of behaviors are integral to individual resilience processes.

The Resilience Solutions Group at Arizona State University outlines seven core principles of resilience (Table 1); while all the strategies described by our participants relate to the Balance principle, their accounts involving other people – from information seeking with coworkers to spending time with friends – also help to illustrate applications of the Social Connectedness principle. In short, all the strategies serve to increase positive affect and decrease stress. Fredrickson’s [Reference Fredrickson21] broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions suggests not only the experience of positive affect can increase the likelihood of experiencing future positive affect but also the affective experience can act as a resource reserve – something that can be drawn upon in times of negative affect. Our participants’ inclusion of positive affect-producing elements into their day during both on- and off-work hours is an effective strategy for resilience and stress management.

Table 1. Core principles of resilience

A model for learning about resilience: Arizona State University Resilience Solutions Group.

Participants also use mental preparation as a strategy to manage emotion. Preparedness allows for a sense of emotional balance perceived as necessary to facilitate management of self’s and others’ emotional states. To prepare mentally for difficult conversations, for example, participants seek information to reduce uncertainty and anticipate multiple options – such as the other party’s reactions and emotional states, potential for conversational difficulties, where best to hold the meeting as a result of those likelihoods, and so forth – based on experience and information-seeking results. These cognitive behaviors relate to the Diversity and Flexibility principles of resilience; diversity refers to having multiple options and flexibility refers to adaptability. By imagining possible conversational trajectories, participants are able to identify and test communicative options against anticipated outcomes. Thus, preparedness permits the anticipation of and emotional preparation for negative affect-producing interactions, resulting in the perception of greater emotional balance upon entering threatening situations. Further, mental preparation can increase the likelihood of competent communication during difficult conversations by allowing the participant to rehearse constructive statements or responses prior to the interaction while in a more emotionally controlled state and space.

Finally, communication strategies for managing emotion in others during difficult conversations consist of integrative conflict management communication tactics, including use of inclusive and confirmatory language, collaborative reframing, and de-escalating vocalic manipulation. Broadly stated, integrative tactics can be defined as “verbally cooperative behaviors or statements that pursue mutually favorable resolution of conflicts” [22, pp. 83–84]. Substantive research has investigated positive outcomes associated with integrative tactics, such as trust [Reference Canary and Cupach23], relationship growth [Reference Roloff and Miller24], perceptions of communication appropriateness [Reference Canary and Spitzberg25], collective communication competence [Reference Thompson26], team member satisfaction [Reference Pinto, Pinto and Prescott27], and conflict outcome satisfaction and teamwork satisfaction [Reference Liu, Magjuka and Lee28,Reference Liu, Magjuka and Lee29].

Despite a heightened awareness of emotion in self and other, as well as incorporation of effective integrative communication strategies, our participants reported a lack of confidence in their ability to manage emotion effectively. Consistent with previous reports of inadequate training opportunities for CRPs [Reference Calvin-Naylor, Jones, Wartak, Blackwell, Davis and Divecha30], our participants both recognized a need and expressed a desire for competency-based communication training. It is our recommendation that more training for CRPs focus on competent communication skills, including conflict management and emotional intelligence. We further suggest that training on how to have difficult conversations would benefit from activities that not only allow for the practice of competent communication skills but also include effective mental preparation strategies as part of that practice.

Limitations and Future Research

Given that all participants and one coresearcher were employed at the same organization, it is possible that some participants may have felt hesitant to share information that could be perceived as negative by other participants. Although the moderator employed strategies to create a nonthreatening environment for participants, the study findings should be considered with this potential limitation in mind. Our single focus group design consisting of a small number of participants who all identify as female is the second limitation; we acknowledge that the findings highlight the perceptions of our participants and may not be reflective of other CRP’s experiences. Consistent with an exploratory qualitative investigation, the purpose of this study was focused insight into CRP perceptions of current workplace communication within a specific organization; despite limitations, the data obtained provided rich insights into the experiences of our participants and the need for future research and training.

Future research designed to recruit a greater number and diversity of participants from multiple organizations could reduce potential risks associated with participant familiarity and, depending on the research design, could achieve results generalizable to a wider population of CRPs. Additionally, the current study’s findings suggest that CRPs are aware of the need for additional training in skills associated with emotional intelligence and conflict management; future research in these areas is warranted. Finally, since conducting this focus group interview, the world has experienced the presence of COVID-19 and widespread shifts in communication policies and procedures; future research aimed at investigating communication-related effects of pandemic safety measures in clinical research is essential.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Focused exploration of the most salient aspects of the communication competencies articulated in the JTF Domain 8 exposed important aspects to actualizing all the prescribed competencies. Study findings underscore the core relevance of managing conflict, as well as managing communication-related uncertainty and the EL that accompanies it, as essential skills to master for developing a fully competent translational research workforce. Additional training in these areas would promote knowledge and efficacy surrounding competent communication behaviors among CRPs.

This report highlights the capability to communicate successfully in challenging interfaces as a core skill required to sustain trust and efficiency in an academic clinical research environment. Interdisciplinary team-based research across the enterprise requires facile interpersonal skills. Communication, teamwork, leadership, and professionalism form a foundation for the development of true competence. In particular, communication is integral throughout all the other competency domains. Thus, we consider reframing the JTF framework’s schematic to make Communication and Teamwork the hub of the wheel with Leadership and Professionalism as the ground of all activity, providing an interconnected matrix of domains (Fig. 2). It is vital that competency domains for CRPs are comprehensive and also reflective of the field experience. In assessing these findings, building on the JTF framework can be enhanced by orientating pragmatically towards work environments by mirroring actual workforce practice.

Fig. 2. Illustration showing proposed revisions to the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency’s Wheel of Competencies.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under University of Florida and Florida State University Clinical and Translational Science Awards TL1TR001428, KL2TR001429, and UL1TR001427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix

Interview Guide Questions (Semistructured)

-

1. With whom do you communicate in a typical workday? For what purposes? Can you describe what that might look like?

-

2. How would you describe your communicative interactions with others at work?

-

3. Probe for examples of competent communication interactions, such as: Can you think of any examples of good or effective communication?

-

4. Probe for examples of contentious communication interactions, such as: Can you think of a time when you or one of your coworkers was involved in communication that was contentious?

-

5. How is conflict addressed in your workplace? Can you tell me about a time when you think conflict was handled well? How about a time when it was not handled well?

-

6. What creates the most conflict in your job?