Introduction

The meanings and perceptions of age and ageing are changing in late-modern societies. Later life is no longer perceived as a lifestage of social disengagement, but increasingly commodified and constructed around productivity and consumption, changing the individual experience of later life from a risk-based to an entrepreneurial one (Shimoni, Reference Shimoni2018). Simultaneously, late-life creativity has been revived as a research topic (Amigoni and McMullan, Reference Amigoni, McMullan, Twigg and Martin2015): in a review of studies covering the last 40 years, Fraser et al. (Reference Fraser, O'Rourke, Wiens, Lai, Howell and Brett-MacLean2015) found that most studies on the subject were published after 2000.

Sociologists such as Andreas Reckwitz argue that this newfound interest in late-life creativity does not come as a coincidence. He repeatedly asserts (Reckwitz, Reference Reckwitz2012, Reference Reckwitz2016, Reference Reckwitz2017) that in late-modern societies, being creative emerges as one of the central normative expectations towards individuals in all stages of life: the ‘creative dispositif’ (Reckwitz, Reference Reckwitz, Rammer, Windeler, Knoblauch and Hutter2018), being creative as a ubiquitous norm and expectation (Reckwitz, Reference Reckwitz2017), has spread to many systems of society and has gained relevance in all lifestages. Late-life creativity, from this perspective, is not just an act of older adults’ engagement in society, but a ubiquitous norm and expectation towards older adults in an entrepreneurial culture of later life.

This change in perspective on late-life creativity consequently sheds new light on the value older adults’ experience through their creative engagement. While gerontology long understood creativity as a process of individual expression, an individual trait or personal characteristic (Flood and Phillips, Reference Flood and Phillips2007), contemporary theories in sociology have conceptualised creativity as a productive process that creates value through innovation (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Corte and MacHado2015). From this standpoint, creativity usually entails two features: ‘1) To have novel ideas (originality), 2) which are valuable; or produce objects which are valuable’ (Hills and Bird, Reference Hills, Bird, Gaut and Matthew2018: 96). Value production through innovation, hence, lies at the heart of the creative process, which becomes a valuable resource in the creative industries (Florida, Reference Florida2004).

These processes of value production as part of creativity are, however, hardly explored in the context of later life. While gerontological literature has widely explored the positive effect creative engagement has on older adults’ lives (for reviews, see e.g. Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, O'Rourke, Wiens, Lai, Howell and Brett-MacLean2015; Rawtaer et al., Reference Rawtaer, Mahendran, Yu, Fam, Feng and Kua2015; Dunphy et al., Reference Dunphy, Baker, Dumaresq, Carroll-Haskins, Eickholt, Ercole and Wosch2018), research examining how older adults create value through their creative engagement remains scarce. This gap is significantly addressed in this article by suggesting that, first, late-life creativity may be conceptualised as an age-coded process of artistic value production that is, second, based on normative expectations towards older adults in entrepreneurial cultures of later life. To do so, this article critically explores how creativity gains, stabilises and loses its value in in later life.

Drawing on the sociology of valuation (Helgesson and Muniesa, Reference Helgesson and Muniesa2013; Doganova et al., Reference Doganova, Giraudeau, Helgesson, Kjellberg, Lee, Mallard and Zuiderent-Jerak2014), the value of a product (or an activity) is understood not as a stable entity, but as something that is constantly (re)negotiated, evaluated and stabilised in daily lives. From this perspective, this article does not aim to explore the value of late-life creativity per se, but rather processes of valuation, as it asks through which processes value is established (Heuts and Mol, Reference Heuts and Mol2013) and how this value ‘is produced, diffused, assessed, and institutionalised across a range of settings’ (Lamont, Reference Lamont2012: 201). Valuation, hence, can be defined as the connection between processes of valorising (in which things are produced so that they can be of value) and evaluating (in which things undergo judgements of value). This entails more than the worth of a piece of work on its own, and rather describes ‘everyday inquiries about what is desired, cared about or held precious’ (Vatin, Reference Vatin2013: 32).

To explore these valuations, this paper first lays out a practice-based theory of late-life creativity. This framework is based on the premise that creativity is not just one, but a bundle (Schatzki, Reference Schatzki and Zembylas2014) of practices. Practices of valuation and devaluation – of gaining and losing value – are an inherent part of these creativity bundles. Second, qualitative data from 13 case studies with creatively engaged older adults is used to analyse the various ways that creative engagement in later life gains and loses its value and how these processes are affected by artists’ age. By applying the documentary method (Nohl, Reference Nohl2017) to interview transcripts, the data analysis reveals that older adults frequently evaluate their creative engagement and that growing older affects these manifold valuations of creative engagement. Creativity can therefore be understood as age-coded (Krekula, Reference Krekula2009), as its value was established and negotiated depending on the interview partner's age.

Theories: late-life creativity and the practices of valuation

To date, research has mostly focused on the positive impacts creative engagement holds for older adults’ health and quality of life (see e.g. Cutler, Reference Cutler2009; Castora-Binkley et al., Reference Castora-Binkley, Noelker, Prohaska and Satariano2010; Noice and Noice, Reference Noice and Noice2013; Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, O'Rourke, Wiens, Lai, Howell and Brett-MacLean2015; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2015; Bernard and Rickett, Reference Bernard and Rickett2016). Research has repeatedly shown that creative and artistic activities hold potentials for older adults’ physical and mental health (Cutler, Reference Cutler2009; Castora-Binkley et al., Reference Castora-Binkley, Noelker, Prohaska and Satariano2010), social integration (Goulding, Reference Goulding2012; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2015) and the development of positive images of ageing (Sabeti, Reference Sabeti2014; Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2015; Swinnen, Reference Swinnen2018). Literature, however, also shows significant gaps in studies concerning late-life creativity: it is seldom explored outside its relationship with health and wellbeing tw and is likewise rarely studied in its manifold contexts and patterns outside interventions within research projects (Goulding, Reference Goulding2018). Consequently, late-life creativity has experienced scarce theorisation beyond these interventions, and the artistic experiences of older adults have yet to be considered in depth when studying late-life creativity (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, O'Rourke, Wiens, Lai, Howell and Brett-MacLean2015).

This lack of focus is partially due to the concepts and theories used when studying late-life creativity. In a literature review, Flood and Phillips (Reference Flood and Phillips2007) show that a majority of gerontological studies on creativity view artistic production as a problem-solving ability, a process which requires the individual to become open to new ideas and seek original solutions to challenges. These studies often approach creativity as an individual process that includes spontaneity, intentionality and choice (Runco, Reference Runco2014), often failing to consider the collective and social aspects of creativity. Scholars from the sociology of arts, however, have repeatedly argued that these collective and social processes of presenting, evaluating and selling pieces of work are an important part of creative practice. As Howard Becker (Reference Becker1974) or Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu2015, Reference Bourdieu2016) have argued, creativity entails a collective effort of producing, consuming and evaluating. The artist is only one of many creators behind the artistic product and creativity cannot be understood without taking the means and manners into account through which artistic products are consumed.

In line with Becker (Reference Becker1974), practices of creativity and valuation arguably cannot be understood as separate from each other: selling pictures, presenting a play to a group of ticket holders or giving away knitted socks to family and friends are as much part of the creative process as the creative imagination itself. Through the creative process, creative products, their values and normative expectations of ‘good/valuable’ and ‘bad/invaluable’ are constantly produced. Practices of valuation are therefore not casual bystanders of creative activity, but an integral part of it. The worth of the creative outcome is not a separate part of creative expression, but shapes and directs the creative process.

To conceptualise these processes of gaining and losing value in late-life creativity, this article draws upon a practice-theoretical framework of late-life creativity. This framework is based on the premise that, first, creativity can be understood as a shared ‘spatio-temporal nexus of doings and sayings’ (Schatzki, Reference Schatzki and Zembylas2014: 18) instead of a human capacity. In that sense, creativity is not an individual attribute or part of a person's character, but something that is continuously done in practice. From this perspective, research on creativity focuses more on the processes of how artefacts, humans or practices become creative instead of conceptualising something as creative (Reckwitz, Reference Reckwitz2017). Practice-theoretical frameworks have been applied to both creativity (Fox, Reference Fox2015) and art (Schatzki, Reference Schatzki and Zembylas2014; Zembylas, Reference Zembylas2014). In both cases, a practice-theoretical framework shifts away from psychological understandings of creativity as a personal competence, and instead asks how creativity is set into practice in everyday lives.

Second, in asking how creativity is produced through practice, a practice-theoretical framework on late-life creativity asks about which actors are involved in this process. Fox (Reference Fox2015) suggests understanding creativity not as an action that is done by one single human actor, but as emergent from ‘creative assemblages’. In these assemblages, humans, non-humans and other actors might act together to produce creativity. The practice of singing, for example, is not done through a singer alone: it involves a room in which the singing takes places, sheet music and the motivations behind singing. These aspects can all be understood as parts of the creative practice. Creativity should therefore ‘be considered not as a human capacity, but as emergent from assemblages of relations between the human and the non-human (things, ideas, social formations)’ (Fox, Reference Fox2015: 523).

Third, understanding creativity as a shared practice between a variety of actors enables conceptually accounting for more than just the creative expression when studying creativity. Practice-theoretical accounts of the arts – such as Pierre Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu1974, Reference Bourdieu1998) work – have argued that art and creativity do not only consist of producing an artistic artefact, and that other practices are equally involved in this process. Singing properly does not just mean that a singer uses their voice: it might also entail, e.g. studying songs, vocal training, reading books about different styles of singing or performing in front of an audience. For the purposes of studying creativity, this might mean that it is not just one practice (e.g. the act of singing), but rather a bundle (Schatzki, Reference Schatzki and Zembylas2014), an art world (Becker, Reference Becker1982) or a field (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu2016) of practices linked together.

Fourth, this understanding of creativity as a shared practice also means that the practices of evaluating a creative product are not discrete creative components. Instead, they are inherently part of the creative practice and always done together in fields or bundles (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1998). In addition to the practice of creative expression (e.g. singing), being creative may also involve hearing the singer, acknowledging their talent (or denying it) or performance quality, or identifying and addressing a singer as a creative person. The practices of evaluating a creative outcome, or the ‘means of artistic production’ (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1998), are therefore always involved in creative practice: shared understandings of what creativity and art are, who is allowed to be creative (and who is not) and which normativities must be followed in order to be creative are consequently always part of how creativity is being done. Processes of valuation are thus not only ubiquitous; they are also central to the hierarchical ordering of practices (Helgesson and Muniesa, Reference Helgesson and Muniesa2013) and creative outcomes.

Finally, if these valuations are based on meanings and notions of age and ageing, they can be understood as ‘age-coded’ (Krekula, Reference Krekula2009). Through this framework, creative practices can be theorised to include certain normativities of old age: singing might be commonly perceived as done better by a young voice, just as a poet might draw on the experience of old age to be considered a legitimate writer. Creativity might therefore include ‘age-based practices of distinction’ (Krekula, Reference Krekula2009: 15) or age-based practices of valuation. In terms of understanding the (de)valuations of creative practice, this raises the question of how the value of creative activities or creative products changes if creativity occurs in later life.

Methods

This paper draws upon data from 13 qualitative semi-structured interviews, which were conducted in 2017, with creatively engaged older adults (60 years and older) in Austria (see Table 1). The final sample consisted of seven older men and six older women who were engaged in different fields, which ranged from more traditional forms of ‘highbrow’ culture (e.g. classical music, orchestra) to ‘lowbrow’ cultural activities (e.g. textile work). The sample also included cases from ‘subcultural’ fields (e.g. body-building, drag).

Table 1. Sample description sorted by date of interview

To reach a heterogeneous sample, researchers distributed an open call to participate in the study through individual contacts and social media that invited regularly creatively engaged older adults to contact the research team. Hence, older adults were sampled based on their self-description as either an artist or regularly creative. After the open call, the interview partners were chosen based on their age (60 years and older) and their field of creative practice to include the highest possible heterogeneity in age as well as field of creative engagement.

The study sample was intentionally kept broad and included both professional and non-professional artists to account for the variation in the boundaries between both artist types in each field of artistic practice and that setting these boundaries reflects manifestations of power structures in artistic fields (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu2016).

Data collection

The interviews were organised using a semi-structured interview guide that covered questions about the creative activity (Please tell me everything that comes to mind when you think about your creative activity); the creative production process (How do you deal with the products of your creative activity?); everyday routines (Please tell me in detail what you do on an ordinary day); and respondents’ personal meanings and attitudes towards ageing (Generally speaking, what does it mean to grow older for you?). During the interviews, these four topics were open for discussion. Additional questions were posed to deepen further the interviewees’ answers and prolong the interviews. Interviews lasted between 80 and 120 minutes and were transcribed verbatim in German. For the purpose of this paper, quotes were translated into English by three researchers (blind back-translation).

Data analysis: documentary method

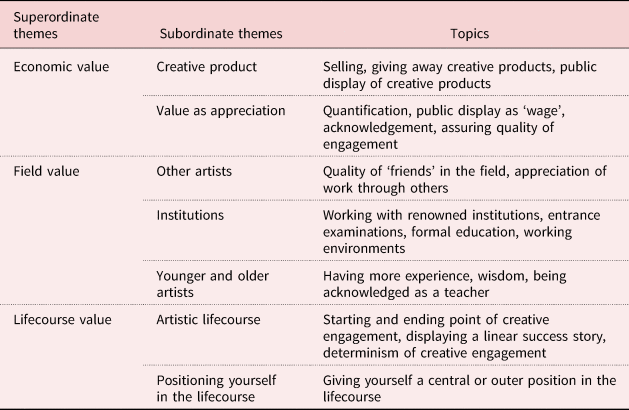

The interview transcripts were analysed using the documentary method (Nohl, Reference Nohl2017), which has been frequently applied to analyse mechanisms and structures of social practices. The method aims to analyse the routine and everyday knowledges that are part of everyday practices (Bohnsack, Reference Bohnsack, Bohnsack, Pfaff and Weller2014) using two steps. First (formulating analysis), interviews transcripts were coded to establish the central topics of each case. This analytical step identified 13 superordinate themes in the data material (see Table 2). The second step focused on the latent meaning (documentary meaning) of each case. Here, the documentary method aims to interpret the more nuanced and hidden forms of how knowledge is expressed in interviews, which frames of reference are used in a field, and which words are used and how. Based on the formulating analysis, parts of text that dealt with similar topics and each case were identified and followed by a comparative, fine-structured analysis in which these parts of the text were discussed with other researchers in four group sessions.

Table 2. Codes used in the formulating interpretation

Results

Which practices of valuation, understood as processes of evaluating and valorising, can be found in late-life creativity? How did these correspond to meanings of age and ageing? The analysis revealed three central bundles of valuation practices that were identified in the interviews through coding (see Table 2).

The bundles identified in the interviews can be recognised as different registers of valuation. Valuation studies understand registers as different axes that map ‘goods and bads’ (Heuts and Mol, Reference Heuts and Mol2013) – things that are high or low in value. This helps the researcher to refrain from analysing worth (as an item's quality) to analysing valuing as many practices that are oriented towards different registers of worth.

Three registers of valuation were identified in the interviews: economic value, which was based on economic revenue, typified through the selling, giving away or presenting of creative products; field value, which was based on appreciation of artistic work by other actors in the field; and lifecourse value, which was based on the lifecourse narratives that artists built around their creative production.

Economic value

The first register, ‘economic value’, included all themes where interview partners discussed the economic revenue from their creative work and how this revenue was expressed or negotiated. While only some respondents pursued their creative activity professionally, topics surrounding the economic value of their creative products and engagement always played a major role in the interviews. This was the case for retired professional artists (e.g. painting), creative older adults who were still employed (e.g. drag) or adults who started their creative pursuit in retirement (e.g. acting, crafting). The two central subordinate themes in that code were ‘the creative product’ and ‘economic value as appreciation’.

Within the ‘creative product’ code, interview partners described how their manifold ways of selling, giving away or presenting their creative products in front of an audience were an integral part of their creative activity. This was relevant for all participants, regardless of whether they were professionally or non-professionally engaged in their artistic field. Some described how they sold their creative products (e.g. through an annual vernissage (painting) or through more informal, small markets in churches or public spaces (crafting)); gave them away as gifts to their children or grandchildren (e.g. giving books away as Christmas presents (graphic design)); or presented their work publicly (e.g. in shows and performances (drag, acting, dancing)). Hence, the value of creativity was often connected to the creation of a material or immaterial creative product that could be sold, given away or presented to an audience to produce revenue.

What importance did the value of a creative product have in older adults’ creative engagement? The subordinate theme ‘economic value as appreciation’ clarified that a creative product's value was often connected to feeling appreciation for one's creative engagement. One strategy through which appreciation was made apparent was quantifying the creative production: the interview partners often described how many paintings they had at home, how many pages they had written that day or for how many years they had been doing the specific creative activity; these quantifications of creative production were often used to showcase artistic productivity. When asked about his creative process, the graphic designer states: ‘I have about 20 folders and in every folder there are – I don't know – approximately 15 or 20 drawings’ (graphic designer). A first step to demonstrate the creative process’ value, therefore, was to show that the interviewee could produce – and the quantity seemed to be an important part in showcasing this productivity.

These quantified creative products were also objects that could be evaluated – they could be sold and given away, through which their value was assessed. This evaluation process was often referred to by respondents as a kind of ‘wage’ (acting) or ‘appreciation’ (crafting) for the creative activity. One interview partner, who is active in a crafting group, explains: ‘We craft things, things we want to craft. And when they are ready, during Advent or Easter, we sell them, and the money is then used for some project for the church or when we need something … and that is a kind of appreciation for doing all of this’ (crafting). Although the creative activity was not pursued professionally, being able to sell creative products was a vital part of feeling appreciated for the creative work in which the interview partners were engaging.

Economic value, however, was only one part of feeling appreciated. Other interview partners described the value of creative products that were more social, e.g. audiences that reacted positively to performances (music, acting). While these presentations were often not valued materially – they were not paid for with money – the interview partners often referred to them as a ‘wage’ (acting) for their creative work and hence expressed a form of appreciation they felt through public performances and the audience's attention. The (non-professional) actress, for example, explains how publicly performing a play served as a kind of wage after working hard to prepare for it: ‘Not that it's such a fantastic feeling, but it's just the wage you get for having worked all year, to have your moment on stage’ (acting). The data show – independent of whether the creative activity happened as a professional or non-professional practice – that creative practices were always centred upon the purposeful creation of value, which was central in feeling appreciated in one's creative practice.

Field value

The selling, giving away or presenting of a creative product was not the only way through which the value of a creative product was determined in the interviews. In the second code, ‘field value’, the field in which the activity occurred played a major role in negotiating the value of the interview partners’ creative engagement. In this regard, other actors in the field – whether institutions such as opera houses (drag), professional competitions (body-building) or colleagues that evaluated the interview partners’ creative work (singing, photography) – strongly determined the value of creative engagement. Drawing on Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1984), these processes can be understood as practices of creating symbolic value through consecration, as they refer to struggles between artists, experts and audiences with the authority to produce symbolic value (see also Cattani et al., Reference Cattani, Ferriani and Allison2014). The findings reveal that the three main actors producing this symbolic value were ‘other artists’, ‘institutions’ and ‘younger and older artists’.

Analysing the first subordinate theme, ‘other artists’, showed how the value of a creative product (or a creative activity) was not just estimated based on the financial value of a sold product, but also on the appreciation the interview partners received from other artists in the field. Colleagues and friends were critical in determining the value and quality of the interview partners’ creative work: a friend or teacher who acknowledged the interview partners’ talents was often the first step towards their involvement in their creative practice. For the photographer, one friend identified that she had ‘the eye’ (photography) for capturing special moments and objects: ‘A friend of mine is very good a taking pictures, and when I showed her a photo that I made – more by accident than intentionally – she said ‘Wow! That's beautiful!’ … and then she said “Wow, you have the eye”’ (photography, emphasis added). For her, the valuation of her photographs through a friend was the start of her creative practice, i.e. being acknowledged as having a special talent gave her the confidence to pursue her hobby further.

This example also shows that for such acknowledgement through other actors in the field, it was important who those other actors were, and which position they each held in their respective field. In line with Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1984), the valuation of artistic activity arguably stems not only from the appreciation from other actors in the field, but also from the (high or low) social positions these other actors have. Their position in the field was ‘determined from the encounter between particular agents’ dispositions … and their position in a field of positions which is defined by the distribution of a specific form of capital’ (Bourdieu, Reference Bourdieu1984: 311). The photographer provides a vivid example of these different field positions: before she describes her special talent (‘the eye’), she emphasises that her friend was not just any friend: it was a friend who was very good a taking pictures and hence had a higher position and higher capital in the respective field. Similarly, the dancer describes how the performer she worked with was not just any kind of dancer – he was ‘the’ dancer in a performance house: ‘Yes, I danced at Bernard Amibél's, if you know him. (No.) Bernard Amibél is French. One should know him; he is the dancer at the Museumsquartier’ (dance).

This appreciation through other actors in the field served as a sign of the creative engagement's value. However, it was not always friends or colleagues who expressed appreciation of the interviewees’ creative engagement. The process of establishing the value of one's creative engagement coincides with processes of institutionally framing artistic activity (Pardo-Guerra, Reference Pardo-Guerra2011). Often, institutions were used to describe the value one's creative engagement had (subcode: ‘institutions’). In such cases, the interview partners frequently referred to universities of the arts (painting), opera houses (drag) or museums (painting) they had worked with to show the high value of their creative production.

During the valuation through other actors in the field, the interview partners’ age was relevant to their evaluation of their own work (subcode: ‘Younger and older artists’). Often, it was younger colleagues who pursued similar creative practices that made the accumulated field knowledges that the interview partners had visible. Due to the long engagement in their field, some interviewees described how their expertise was valued by younger colleagues. The body-builder, for example, describes how his 20-year long engagement gave him relevant field knowledge that had value for younger body-builders: ‘Young people ask me “How do you do that? … You have done so much, you're the one who knows how it's done”’ (body-building). Having a certain amount of experience in this context served as a surrogate for a high-in-value creative production. The experience older adults had gave a special kind of value to their creative activity. However, the material also showed that the value of late-life creativity was age-coded in manifold ways – in some cases, older adults’ experiences gave a distinct value to creativity activity, while in others, old age was seen as a disadvantage, a surrogate for creating a product that was lower in value.

Lifecourse value

The story of the body-builder shows that age played a part in how interviewees’ creative practice was valued. Age was insinuated when describing how the interview partners had more knowledge than younger participants in the field (body-building, drag). In other interviews, young age was seen as a competence, while old age was conceptualised as a disadvantage (acting). Regardless of the field of creative engagement, however, all interviews showed that it was a particular creative lifecourse that gave a specific value to creativity that occurred in later life. Here, the ‘lifecourse value’ code focused mainly on how older adults constructed their creative lifecourse and which values they extracted from their lifecourse narratives. The analysis revealed that building a linear artistic lifecourse gave a specific value to late-life creativity. In short, being creatively engaged for a very long time often also meant producing a creative product that was high in value. This was, however, not achievable for all interviewed artists.

Although not asked specifically about how their engagement with creative practice started, each interview partner opened the interview by explaining – in a lengthy manner – how they ‘ended up’ (acting) doing what they were doing creatively. The drag artist, for example, answered while being asked about what he was doing creatively: ‘I'll need to start all the way back, in the beginning. How I ended up doing this is the reality of my entire life’ (drag). Often, the interview partners described that at one point in their life – whether during their childhood or later – becoming creative and producing artistic objects was inevitable. While the interview partners’ stories varied greatly in the timing of their creative practice – some had always painted or sung ever since they were children or teens (singing, painting), while others took up their creative practice in retirement (orchestra music, acting) or were engaged professionally in their working lives and continued in retirement (painting) – all participants described how their circumstances inevitably led to their creative engagement. The singer, for example, explains: ‘I've always shown other children how to play creatively … I wasn't just a wild child, I have also always been creative’ (singing).

Building this linear narrative of how their creative practice came into being was one of the most important structures in discussing the value of a creative practice: doing it for a long time and building the whole lifecourse up to pursuing this creative practice assigned value to the interview partners’ creative activity. The construction of a linear creative lifecourse, however, was easier for some (e.g. those who had always earned a living through their creative practice (painting)) than others (e.g. those who had tried several ways of making a living with their creative practice (singing)). ‘Well, I (pause) paint pictures, and I have been doing that for a very long time. I have always painted and the way into the arts was more or less determined for me’ (painting), the painter said as he opened his interview. Here, the interview partner describes his creative lifecourse succinctly: he has painted his entire life, which is why he is doing it now. Additionally, he expresses the legitimacy of his position – he feels secure in his self-description as a painter: he is not just painting; he has been doing this for a long, long time.

In contrast, other lifecourses were not so easily translated into the display of a linear creative lifecourse. The singer, who has tried to make a living from her music for her entire life, had successful years with her husband and now – after her husband's passing – plays small concerts (with a low entrance fee) in retirement homes and has more trouble finding and displaying this linear creative lifecourse. In the beginning of her interview, she says:

Where can you start when you are that old? Well, as a child, I was the daughter of a folk violinist and my mother stayed home … we were free children in a very rural area … and I have always been interested in everything green and small and I always made little gardens out of the flowers and so I motivated the other children to play creatively. (Singing)

Her response demonstrates how building up her creative lifecourse is completely different than for the painter. The most obvious difference is that compared to the painter, who was quick to portray a linear success story of his determination to paint, the singer first struggles to find this linear temporal structure. Here, the interviews made clear that certain ways of moving through an artistic lifecourse were perceived to be higher in value than others. Showing a linear success story that inevitably led to creative engagement in the here-and-now also meant that the creative product produced was higher in value.

Discussion

This article contributes to the growing literature on older adults’ creative engagement by shedding light on the valuation practices that are part of late-life creativity. By empirically showing how selling, giving away and publicly presenting creative objects is a vital part of older adults’ creative engagement, it emphasises late-life creativity as a process of value production that is structured by the making and evaluating of creative products. The analysis revealed three registers of valuation in late-life creativity – economic value, field value and lifecourse value – all of which exemplify different expectations towards ‘good’ or valuable creativity in later life.

For economic value, ‘good’ creativity was sold or given away for a high revenue. Even though some participants did not earn money from their creative products, the importance of a ‘wage’ or ‘appreciation instead of wage’ exemplified how all of the study participants accepted an economic logic of creativity. This corresponds to the commodification of late-life creativity (Gallistl, Reference Gallistl2018) and illustrates how notions of creativity that have been transformed to fit agendas of productivity and economic value (Reckwitz, Reference Reckwitz2017) have reached later life. Late-life creativity, despite the evidence of the positive effect that creative engagement has on older adults’ health, wellbeing and quality of life, therefore, needs to be understood in the context of an entrepreneurial spirit in later life. For the register of field value, ‘good’ creativity was appreciated by either institutions or other artists in the field. Here, the value of late-life creativity was based on institutional framing (Pardo-Guerra, Reference Pardo-Guerra2011) by, for example, opera houses, theatres or dance studios. The empirical material therefore strengthens the argument that creativity is not an expression of individual agency, but a relational and collective process (Sabeti, Reference Sabeti2014; Fox, Reference Fox2015) that includes older individuals, audiences, institutions and other artists in the field. Studies on late-life creativity, hence, further need to problematise the contexts in which creative production in later life happens: cultural institutions, such as theatres, museums and opera houses, have yet to embrace older adults as active producers of art, rather than (passive) consumers (Gallistl et al., Reference Gallistl, Parisot and Birke2019), which might be one reason why participation in cultural activities over the age of 65 is declining in most European countries (Falk and Katz-Gerro, Reference Falk and Katz-Gerro2016). From this perspective, we need to ask in which institutional frameworks late-life creativity can happen and how symbolic value is produced through these institutional framings of age and ageing. Most importantly, late-life creativity was structured by lifecourse value. Here, doing a creative activity for a long time meant being able to produce a creative product that was high in value. This draws attention to diverse notions of time in the construction of value (Heuts and Mol, Reference Heuts and Mol2013) and shows how embeddedness in (historical, generational or lifecourse) time attaches a special value to an object.

These three registers of valuation in late-life creativity exemplify the many activities required by the interview partners to produce art that was considered as valuable: successful late-life creativity produced economic revenue, was highly appreciated by other artists and institutions, and occurred continually over the lifecourse. In that sense, the results highlight the social and individual requirements for successful late-life creativity and question how accessible creative engagement is depending on social positions held in later life. Therefore, this paper typifies the exclusionary character of late-life creativity (or notions of the entrepreneurial self in later life in general), as it supports authors who have highlighted the difficulties older adults might face towards (valued) self-expression through creativity (Baars, Reference Baars2012).

This article also adds to the current critique that the narrow view of late-life creativity in its associations with wellbeing presents a reductionist picture of the potentials that the arts, culture and creativity have in older adults’ lives (Fraser et al., Reference Fraser, O'Rourke, Wiens, Lai, Howell and Brett-MacLean2015; Bernard and Rickett, Reference Bernard and Rickett2016). Applying a critical lens to late-life creativity allows research to see a more exciting and fully rounded picture of older adults’ artistic experiences. Critically taking a thorough look at late-life creativity, therefore, enables us to grasp meanings of age and ageing late-modern cultures in which productivity (Gallistl, Reference Gallistl2018), value production and innovation lie at the heart of normative expectations towards older adults.

The results also demonstrate the added value of concepts from valuation studies (see e.g. Lamont, Reference Lamont2012; Helgesson and Muniesa, Reference Helgesson and Muniesa2013; Heuts and Mol, Reference Heuts and Mol2013; Doganova et al., Reference Doganova, Giraudeau, Helgesson, Kjellberg, Lee, Mallard and Zuiderent-Jerak2014) in gerontology. Concepts from valuation studies facilitate asking under which circumstances and through which processes and practices the products, activities or subjectivities of older adults are valued and when and how they are de-valued. Future research should look more closely into the diverse forms in which older adults’ activities are valuated and ask how values surrounding older adults’ activities are assessed. Dominant approaches in gerontology, which are organised around productivity and active later life, tend to also produce images of unsuccessful, failed, ‘frailed’ or devalued old age (Grenier et al., Reference Grenier, Lloyd and Phillipson2017), and valuation studies might enable critical gerontological research to ask which processes and practices of valuation are attached to later life, and also allow for a deeper analysis of how (and which) aspects of later life become devalued.

Finally, exploring valuations in late-life creativity is not only fruitful for research; it can also inform the planning and conceptualisation of arts-based interventions for older adults. There are two primary reasons for this. First, it enables imagining arts-based interventions for older adults beyond the realm of quality of life and health, and instead encourages thinking about how a valuable artistic experience can be supported in older adults. The empirical material presented here would suggest moving away from the idea of arts-based interventions and towards artistic co-production with older adults. Second, by taking valuation processes into account, this paper contends that artistic and creative production in later life needs public display and performances in order to be considered high in value. Arts-based interventions for older adults, hence, should more closely consider how older adults’ creative productions in these processes can be valued and publicly appreciated.

This study had several limitations, including the small and non-representative sample used and a bias in recruitment. Study participants were recruited through an open call that was, first, not accessible to certain groups of older adults, given that the call was predominantly published online. Readers should therefore keep in mind that the results of this study were based on interview materials with predominantly white and healthy, older artists. Second, sampling for this study was based on older adults’ self-perceptions as creative, which included a variety of lifestyles from professional artists to adults who pursued creativity as a leisure activity. Further, the results displayed in this article do not permit display of the full heterogeneity of the sample. This especially calls for a critical reflection on the difference between fields (e.g. differences in valuation practices in drag and orchestra music), but also the gender of interview partners. Likewise, this study was situated in Austria's specific cultural context, which influences perceptions of what art and artists are and how the value of artistic work is established. While this means that results can be applied with care to most western European countries, which have a similarly structured cultural sector (Mandel, Reference Mandel, Freericks and Brinkmann2015), the case might be different in American or non-Western contexts in which the cultural field is traditionally structured differently.

Acknowledgements

I thank my colleague, Eva Wimmer, who supported me during the data collection and data analysis, and the Department of Social Sciences (University of Vienna) for supporting this paper.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Department of Sociology, University of Vienna.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The appropriate steps have been taken. All research participants declared informed consent to participate in this study.