Introduction

Decolonizing efforts became common across many academic disciplines, to the point where one could say that ‘decolonizing’ became a metaphor lacking practical meaning: i.e. Indigenous reparations (Tuck & Yang Reference Tuck and Yang2012). However, from a perspective drawing from decolonial theory, ‘decolonization’ means much more than undoing colonialism. It presupposes ‘epistemic reconstitution’, for which there is no formula. Decolonization—from the point of view of decolonial theory—is currently taking place in the emergence of various political and social collectives in the global south and minorities in the global north. This includes activists, scholars, museum professionals, artists, etc. in a context of decentralization of power once held exclusively by the north Atlantic part of the world. In this way, it is probably a positive thing that decolonizing efforts are everywhere and in many forms, as there is no single recipe for decolonization (see Mignolo Reference Mignolo2017). However, if decentralization brings diversity, it can also produce blurred understandings from a theoretical point of view.

‘Decolonizing’ archaeologies today consist mostly of a critique of colonial ideologies and collaboration with Indigenous and local communities, focusing on the management of heritage in opposition to employing those communities as ‘informants’ only (Bruchac Reference Bruchac and Smith2014; Smith & Wobst Reference Smith, Wobst, Smith and Wobst2005). In archaeology, ‘decolonizing’ usually implies ‘decolonization’, understood as undoing of colonialism, a process that decentres dominant ideologies and results in independence (Betts Reference Betts, Bogaerts and Raben2012). Such a characterization is probably related to the discipline's strong connection with postcolonial theory (Gosden Reference Gosden and Hodder2001, 241; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen and Tilley2006) and, so far, limited direct engagement with decolonial theory/decoloniality (cf. Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2018).

Despite archaeology's emphasis on ‘decolonization’, both postcolonial and decolonial theory have criticised decolonization, based on the fact that the process of dismantling former colonies has not resulted in emancipation. Instead, decolonization resulted in nationalism, which substituted old colonial ruling classes with local elites re-enacting oppression (Keller Reference Keller, Martin and O'Meara1995; Mignolo Reference Mignolo2017). On the one hand, postcolonial theory offers ways to criticize colonial oppression and strategies of reproduction of colonial ideologies: on the other, decolonial theory/decoloniality proposes a way out of such oppressions, through the epistemic reconstitution of us all, towards decolonial futures.

In archaeology, postcolonial theory mostly presupposes a critical assessment of past colonial situations (Dietler Reference Dietler2010; Dietler & López-Ruiz Reference Dietler and López-Ruiz2009; Given Reference Given2004; Gosden Reference Gosden2004), while ‘decolonizing’ efforts have focused on the practice and management of heritage today in collaboration with local stakeholders (Pikirayi & Schmidt Reference Pikirayi, Schmidt, Schmidt and Pikirayi2016). Such a past (theory)/present (practice) division finds echoes in the archaeology of the Nile valley, especially in Sudan.

Decolonizing—both from a decolonial perspective and in its current usage by archaeologists—implies change in the present. Action is needed to overcome present-day inequalities towards decolonial futures, both through reparations and the epistemic reconstitution of our society, our culture and ourselves. But can we decolonize the ancient past? This paper suggests that we can, through a better understanding of the commonalities and discrepancies between postcolonial and decolonial theory, and the consciousness that antiquity as a whole has been entangled with present-day structural inequalities as one of the many intellectual supporting pillars of what decolonial theorists refer to as modernity/coloniality; e.g. colonial/racist interpretations of ancient Egypt, which greatly impact modern the experiences of communities along the Nile both in historical narratives and in practice (Agha Reference Agha2019; Carruthers Reference Carruthers2020a; Doyon Reference Doyon and Carruthers2014; Hassan Reference Hassan2007; Quirke Reference Quirke2010; Tully & Hanna Reference Tully and Hanna2013; see also Mickel Reference Mickel2021).

In this paper, I will discuss the trajectories and results of postcolonial and decolonial theory in archaeology, focusing on Sudan and Nubia. I will argue for a move from ‘decolonizing’ archaeologies towards proper ‘decolonial’ archaeologies through the bridging of postcolonial and decolonial theory. Most decolonizing efforts in archaeology and, more specifically, in Sudanese and Nubian archaeology could benefit from a more comprehensive theoretical discussion that guides archaeological interpretation and practice and allows us to overcome conceptual problems, such as ‘decolonization’ as opposed to ‘decoloniality’. Addressing the differences and common aspects of postcolonial and decolonial theory also allows us to overcome the implicit division between theory and practice through what I will refer to as ‘narratives of reparation’.

Postcolonial theory and archaeology

Postcolonial theory provides a critical framework that allows archaeologists working around the world to identify inequalities created by colonialism in the societies we study. According to Lydon & Rizvi (Reference Lydon, Rizvi, Lydon and Rizvi2010, 17), it also allows us to confront ‘the legacies of colonization in the form of persistent structural inequalities’, what decolonial theorists would refer to as coloniality. In archaeology, such inequalities are expressed in scholarship and heritage management, which usually excluded local communities, descending or not from past groups (Lemos et al. Reference Lemos, von Seehausen, di Giovanni, Giobbe, Menozzi and Brancaglion2017; Meskell Reference Meskell2006; Tully & Hanna Reference Tully and Hanna2013). Postcolonial theory helps us criticize the history of inequalities that produce and define heritage today towards new concepts and practices.

Postcolonial archaeologies also include critical assessments of the history of the discipline within colonial frameworks of thought and action (Lydon & Rizvi Reference Lydon, Rizvi, Lydon and Rizvi2010, 18). Although crucial to identify and address colonial historical inequalities in our field, the process of reassessing archaeology's colonial past in northeast Africa has been put forward as ‘decolonizing’, when it would be probably better described as postcolonial (cf. Matić Reference Matić2018; Minor Reference Minor and Honegger2018).

Postcolonial theory is a body of ideas and methods that originate in anti-colonial movements (e.g. Césaire [1955] Reference Césaire2000; Fanon [1952] Reference Fanon2005; cf. Liebmann Reference Liebmann, Liebmann and Rizvi2008). Post-colonial (with a hyphen) can also denote the historical period following the last independence movements—although a more precise meaning of ‘postcolonial’ denotes a body of theory, rather than a specific period in time. Moreover, postcolonial scholars would find it problematical to characterize our time as post-colonial (with a hyphen) given the enduring effects of colonialism, experienced especially by minority groups across the globe today (Lydon & Rizvi Reference Lydon, Rizvi, Lydon and Rizvi2010; Pagán-Jiménez Reference Pagán-Jiménez2004).

Postcolonial scholarship in general, and postcolonial archaeologies more specifically, are essentially political—just like any scholarship. It has been described as ‘a kind of “activist writing”, committed to understanding the relations of power that frame colonial interactions and identities, and to resisting imperialism and its legacies’ (Lyndon & Rizvi Reference Lydon, Rizvi, Lydon and Rizvi2010, 19). This is mostly exemplified by the work of the ‘holy trinity’ of postcolonial theory: Said, Spivak and Bhabha (van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen and Tilley2006; Reference van Dommelen2011).

Said's Orientalism (Reference Said1978) focused on Western representations of the so-called ‘Orient’ and how such representations were connected to discursive conceptions of an allegedly superior ‘culture’ (i.e. Western), which used such representations to build on an exotic, weird, inferior ‘Other’. Spivak's essay Can the Subaltern Speak? (Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988) makes explicit the implicit references to silenced groups who were denied an official voice in colonial discourses and social structures of power. This allows us to unveil the structural and symbolic violence of colonizers against the colonized, and retrieve alternative histories from the point of view of the silenced. The latter can only be accessed indirectly via textual sources dominated by Western intellectuals who did not attempt to hear such voices. Bhabha is probably the most influential postcolonial voice in archaeology. His essays in The Location of Culture (Reference Bhabha1994) develop a theory of cultural hybridity resulting from various forms of colonization, which leads to cultural desires and exclusions. As a ‘committed body of theory’, Bhabha's work laid the foundations for us to confront colonial claims of ‘purity’ of certain cultures over others. Rather, hybridity bridges the ‘colonial divide’ by emphasizing the creative potential of ‘third spaces’ in colonial situations (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1994, 55).

Postcolonial theory has become largely centred on the closely related notions of representation and discourse. This has been criticized by, among others, decolonial thinkers (see Bhambra Reference Bhambra2014; cf. Preucel Reference Preucel2020). Archaeology, in this sense, has the potential to bring material experiences of colonization into postcolonial discussions via material culture (cf. Swenson & Cipolla Reference Swenson and Cipolla2020), towards an understanding of past silenced groups independent of how they do or do not appear in colonial narratives (Given Reference Given2004; Liebmann Reference Liebmann, Liebmann and Rizvi2008, 4; van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen and Tilley2006; Reference van Dommelen2011). Recent archaeological research emphasizes the role of artefacts beyond representation; e.g. the roles performed by foreign objects in local contexts towards the creation of alternative social realities based on the same, though transformed, imposed material forms (Lemos Reference Lemos2021; Pitts Reference Pitts2019; Pitts & Versluys Reference Pitts and Versluys2021).

Postcolonial archaeologies aim to reconsider colonialism from the perspective of the colonized, subaltern, silenced actors not well reflected—or deliberately misrepresented—in colonial narratives and material culture. Overall, postcolonial archaeologies contest and confront colonialism and its legacies (Loomba Reference Loomba1998, 12), which result in:

1) Alternative, bottom-up narratives about past societies, especially ancient Indigenous/subaltern groups (van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen and Tilley2006, 108). These past groups, which have not participated in the construction of colonial narratives, are mostly accessible via material culture, which allows us to reconstruct subaltern experiences of colonization and inputs towards the constitution of alternative social realities beyond those described by ideological textual sources, for example, illiterate non-elite groups in Egypt and colonized groups in Nubia, whose agency and creative potential still remains largely under the shadow of literate elites and their abundant textual and material record (Bussmann Reference Bussmann, Bussmann and Helms2020; Lemos Reference Lemos, Maynart, Velloza and Lemos2018; Reference Lemos and Smith2020; Reference Lemos2021; see also Kemp Reference Kemp1984; Smith Reference Smith2010);

2) ‘The awareness that colonial situations cannot be reduced to neat dualist representations of colonizers versus colonized’ (van Dommelen Reference van Dommelen and Tilley2006, 108). This perspective, which derives mostly from Homi Bhabha's work, has played a major role in archaeological interpretations of colonial situations across the world (Liebmann Reference Liebmann, Liebmann and Rizvi2008, 5; e.g. Cornell Reference Cornell, Cipolla and Hayes2015; van Pelt Reference van Pelt2013);

3) ‘The critique of colonial traditions of thought’ and ‘strategies for restitution and decolonization’ (Lydon & Rizvi Reference Lydon, Rizvi, Lydon and Rizvi2010, 23). Here lies a potential common ground between postcolonial and decolonial thinking (Bhambra Reference Bhambra2014; Liebmann Reference Liebmann, Liebmann and Rizvi2008, 5), which suggests that postcolonial criticism of disciplinary histories, such as archaeology, anthropology and Egyptology (Carruthers Reference Carruthers and Carruthers2014), works as a first step towards reparations. These reparations can take shape, for instance, as restitution of looted artefacts (Hicks Reference Hicks2020) and collaborations with local communities (Hayes & Cipolla Reference Hayes, Cipolla, Cipolla and Hayes2015), but also as decolonial historical narratives that would delink the ancient past from its traditional role as supporting pillar of coloniality.

Decolonial theory and archaeology

Decolonizing efforts are now widespread in society. In archaeology (including Sudan and Nubia), such efforts overlap to some extent with postcolonial theory, which has produced blurred notions of what both postcolonial theory and decolonial thinking/decoloniality actually seek and their different trajectories. Postcolonial theory and decoloniality intersect at least in three points.

The first is the recognition of the lived effects of previous colonialism materialized as inequalities and necropolitics that dictate the experiences of minority groups today; e.g. slavery resulting in structural racism in the Americas (see Bhabha & Comaroff Reference Bhabha, Comaroff, Goldberg and Quayson2002; Lydon & Rizvi Reference Lydon, Rizvi, Lydon and Rizvi2010; Mbembe Reference Mbembe2019; Pagán-Jiménez Reference Pagán-Jiménez2004; Said Reference Said1998). Another point of contact between postcolonial and decolonial theory is the recognition of the failure of decolonization, which moved previous colonized societies towards nationalism (Bhabha & Comaroff Reference Bhabha, Comaroff, Goldberg and Quayson2002; Mignolo Reference Mignolo2011; Reference Mignolo2017). Nationalism impacts the writing of postcolonial narratives and attempts to decolonize the practice of archaeology from the perspective of decoloniality (Langer Reference Langer, Woons and Weier2017a). The third contact point is the use of postcolonial criticism as a methodology to overcome coloniality and establish ethics (Dunford Reference Dunford2017; Hutchings Reference Hutchings2019; see also Winnerman Reference Winnerman2021).

Besides common aspects, the trajectory of decolonial theory/decoloniality differs from that of postcolonial thinking. Decoloniality derives from the recognition of coloniality, which is different to colonialism (addressed and criticised by postcolonial studies), and about starting ‘decolonial healing’ (Mignolo & Vasquez Reference Mignolo and Vasquez2013). This can be achieved, for instance, through art and engagement with local communities and their artistic, analytical and managerial inputs to heritage and history. Escaping coloniality—i.e., delinking oneself from the colonial matrix of power (Mignolo Reference Mignolo2007)—is not simple. First, we need to understand what is coloniality. Retracing its genealogy allows us to identify the fundamental differences between postcolonial theory and decoloniality (which is not decolonization).

Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano developed the concept of coloniality. While postcolonial theory focuses on colonialism and its effects upon subaltern groups in colonial situations, silenced by colonizers in discourse and practice, Quijano (Reference Quijano1991) identified coloniality as a major power structure born alongside European colonialism in the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, but which outlived colonialism in the sense that our world is shaped not by the effects of past colonization (which lies in the realm of postcolonial interpretation); rather, coloniality's power structures are the very same inequalities that started with colonialism and survive, to this day, through the Eurocentric notion of modernity. Modernity is anchored on philosophy—European philosophy: ‘I think, therefore I am’—the Cartesian dualism that separates ‘Us’ from the ‘Other’, humans from nature, subjects from objects, and established science—European science—as the only way of thinking and doing and inhabiting the world (cf. Latour Reference Latour1991).

I am not contesting modern science here, especially during a global pandemic. I am simply discussing the dualism that characterizes modern European rationality as universal, which automatically places this way of being-in-the-world—the European way—as the only possible, valid way. In archaeology, this materializes as the ‘ritual’ and ‘rationality’ divide, which affected both how we understand past populations (re)enacted in modern scholarship and how we, as representatives of modern, allegedly universal rationalism, separate ourselves from Indigenous communities and their ‘exotic’ worldviews, usually downplayed as ‘religion’ (Brück Reference Brück1999; Jopela et al. Reference Jopela, Nhamo, Katsamudanga, Halvorsen and Vale2012; Pyburn Reference Pyburn1999). The current ontological turn is ‘taking other ontologies seriously’ and opening space for alternative ways of understanding and inhabiting this world in equal terms. Fruitful ways of establishing what decolonial scholars refer to as ‘pluriverse’—as opposed to ‘universe’—lie, for instance, in traditional African and Diasporic worldviews (Simas & Rufino Reference Simas and Rufino2018) or Indigenous forms of creating relationships with nature (Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro2009; see also Cipolla Reference Cipolla, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020; Escobar Reference Escobar, Brightman and Lewis2017; Harding Reference Harding and Reiter2018; Mignolo Reference Mignolo2007)—as opposed to rationality leading to climate disaster (Danowski & Viveiros de Castro Reference Danowski and Viveiros de Castro2017).

Once again, decoloniality is not decolonization. Decolonization refers to the process of independence of former colonies—a process that resulted in various forms of nationalism, which reproduce coloniality instead of promoting the emancipation of former subaltern groups. Decoloniality as a concept was later developed from the writings of Quijano and implies a process of delinking ourselves from coloniality. In Mingolo's words (Reference Mignolo2007, 457),

Decoloniality turns the plate around and shifts the ethics and politics of knowledge. Critical theories emerge from the ruins of languages, categories of thought and subjectivities (Arab, Aymara, Hindi, French and English Creole in the Caribbean, Afrikaan, etc.) that had been consistently negated by the rhetoric of modernity and in the imperial implementation of the logic of coloniality.

On the one hand, border thinking is one important way for us to situate ourselves in scales of categorization of coloniality (Mignolo Reference Mignolo2000). On the other hand, exploring the potential of ‘decolonial cracks’ is crucial for us to build a truly emancipatory pedagogy (Freire [1970] Reference Freire2017) that will allow us, in Walsh's words, to ‘unlearn the rational modernity that (de)formed me, to learn to think out in the fissures and cracks’ (Walsh Reference Walsh2014; see also Mignolo & Walsh Reference Mignolo and Walsh2018). In archaeology, decoloniality allows us to situate the role of scholars, communities and heritage in scales of coloniality. It also allows us to act towards removing these actors from the colonial matrix of power that reinforces the subaltern position of local communities living in the vicinity of sites and scholars in former colonized countries. The subaltern character of both local communities and scholars outside of the North Atlantic mainstream is based on colonial ways of thinking and doing still enacted today and considered as universal rules over local forms of being-in-the-world.

Decolonizing efforts in archaeology have mostly sought emancipation through collaboration with Indigenous and local communities. However, this has had limited impacts in the overcoming of the colonial divide between ‘Us’ and the ‘Other’ (González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado2018; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2018). Moreover, the structural limitations that reinforce the subaltern character of often idealized Indigenous and local communities in socioeconomic systems have rarely been addressed by ‘decolonizing’ archaeologies (Bradshaw Reference Bradshaw2018).

Decolonizing archaeology from a decolonial perspective implies overcoming coloniality, instead of colonialism, the latter being understood as a concrete social formation specific to time and space, subject to critical assessments of archaeological evidence and disciplinary histories. Coloniality is a major supporting pillar of our world system through the ingrained, alleged universal notion of modernity, which stems as ‘rationality’, ‘science’, ‘civilization’, ‘progress’, etc. Coloniality reinforces the subaltern character of certain groups in the present because it epistemologically reproduces the inequalities created by colonialism since its inception as the main structuring pillar of our societies.

Results of postcolonial archaeologies: alternative histories of ancient Nubia's colonial past

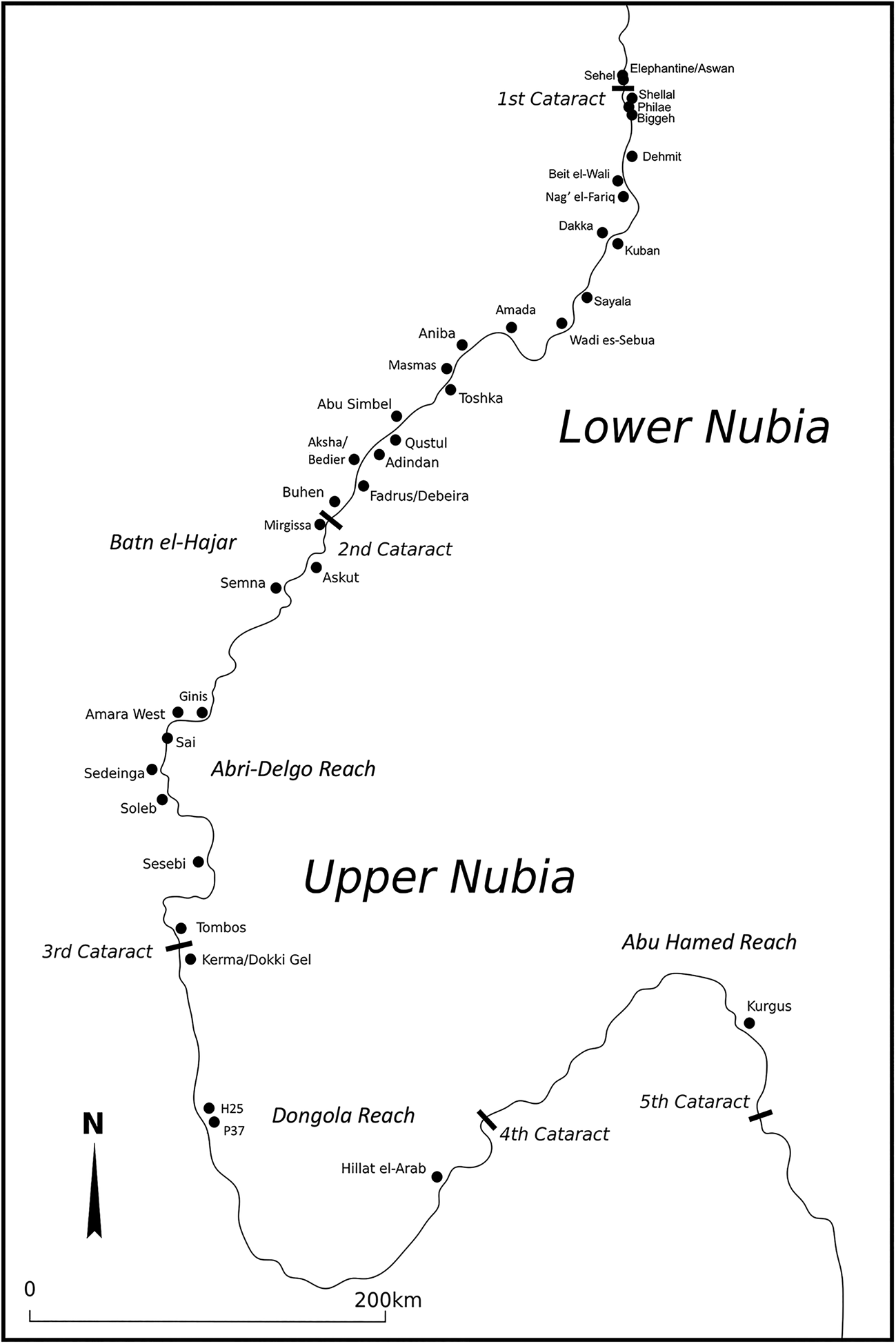

Postcolonial theory offers us ways to revise and interpret past colonial situations critically; e.g. the Egyptian colonization of Nubia, first in the Middle Kingdom (2200–1600 bce, only in Lower Nubia), then in the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 bce) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Map of ancient Nubia showing the location of various colonial sites. In the New Kingdom, the Batn el-Hajar, north Abri-Delgo Reach, parts of the Dongola Reach and the Abu Hamed Reach remained peripheral zones in relation to major colonial centres (e.g. Aniba, Sai or Soleb).

Around the world, postcolonial archaeologies have helped scholars to rewrite historical narratives of colonial situations from the perspective of the colonized. In Egyptology, such narratives are rare, because of the discipline's emphasis on the Egyptianization or acculturation of local Nubian populations in the New Kingdom colonial period. These narratives were deeply entangled with the modern colonization of northeast Africa (Lemos & Tipper Reference Lemos, Tipper, Lemos and Tipper2021). An exception to the rule is Stuart Smith's book Wretched Kush (Reference Smith2003). Even though the book is not explicitly treated as an example of postcolonial scholarship, it has set the foundations for later bottom-up explanations of the New Kingdom colonial period in Nubia from the perspective of local populations interacting with foreign cultural patterns (Lemos Reference Lemos and Smith2020; Reference Lemos2021; Lemos & Budka Reference Lemos and Budka2021; van Pelt Reference van Pelt2013; Weglarz Reference Weglarz2017). This interaction resulted in various experiences of colonization and included phenomena like adoption and adaptation of Egyptian-style material culture, as well as resistance to foreign patterns (Smith Reference Smith, Emberling and Williams2020).

Wretched Kush is an analysis of the ideological nature of ancient Egyptian colonial discourses about the ‘Other’. These discourses allow little to no room for the colonized to appear other than as inferior in relation to colonizers (sensu Spivak Reference Spivak, Nelson and Grossberg1988). This becomes clear, for example, in the text found on Senwosret III's boundary stela at the Egyptian fortress of Semna:

Moving beyond analyses grounded on Egyptian textual sources, Smith brings into the equation pictorial and archaeological sources that allow us to approach the experiences of silenced subaltern groups in colonized Nubia. This allows us to unveil their inputs to cultural interactions, which are always two-way avenues, rather than a process of ‘civilizing the barbarians’. Smith's interpretation of Nubian cooking wares in colonial contexts in Nubia is especially significant for its emphasis on Nubian cultural resistance and identity in daily life—something usually absent from (ancient and modern) colonial discourses about, and interpretations of, Nubian history (Smith Reference Smith2003, 113–24).

In the New Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians colonized Nubia from the first to the fifth Nile cataracts (Davies Reference Davies, Spencer, Stevens and Binder2017). Following an initial period of reconquest of earlier fortifications in Lower Nubia, the Egyptians later defeated Kerma, then establishing their power in the Middle Nile in the early 18th Dynasty (Davies Reference Davies, Weslby and Anderson2004; Gabolde Reference Gabolde2012). From the mid 18th Dynasty, Egyptian colonizers erected a series of planned settlements (or temple-towns) along the river (Spencer Reference Spencer and Raue2019). These settlements not only materialized the cult of Egyptian deities on local ground (Budka Reference Budka, Bács, Bollók and Vida2018; Gabolde Reference Gabolde, Emberling and Williams2020; Rocheleau Reference Rocheleau2008; Thill Reference Thill, Spencer, Stevens and Binder2017), but also worked as major administrative centres housing colonial officials and Indigenous communities, as recently suggested by stable isotope analyses at various sites (Buzon et al. Reference Buzon, Simonetti and Creaser2007; Retzmann et al. Reference Retzmann, Budka, Sattmann, Irrgeher and Prohaska2019).

Colonial towns were surrounded by a thick wall, inside of which were located a main stone temple, a second cultic area, magazines and other administrative buildings and houses (Kemp Reference Kemp and Ucko1972; Spence Reference Spence2004; Vieth Reference Vieth, Budka and Auenmüller2018). From an architectural point of view, these settlements follow Egyptian standards, although local agency materialized, for instance, in the adaptation of house plans and later urban development outside the surrounding walls (Spencer Reference Spencer2014).

Large cemeteries developed in association with colonial settlements, where Egyptian-style shaft-tombs were excavated in the bedrock (Lemos Reference Lemos and Smith2020; Spence Reference Spence and Raue2019). A rectangular vertical shaft usually led to multiple subterranean chambers, housing several interments deposited in an extended position accompanied by Egyptian-style objects (Fig. 2). Large non-elite cemeteries are also known in New Kingdom Nubia, of which the main example is Fadrus. At the cemetery of Fadrus, multiple pit graves were excavated, housing mostly extended bodies with only a few associated Egyptian-style objects (Säve-Söderbergh & Troy Reference Säve-Söderbergh and Troy1991).

Figure 2. Tomb 26 on Sai island and part of one burial assemblage from inside the tomb. Top left: reconstructed superstructure; bottom left: section of shaft and underground chambers. The finger ring, heart scarab and shabti date from the 18th Dynasty and were found in association with the burial of master of goldsmiths Khnummose (Budka Reference Budka2021). (Courtesy of the AcrossBorders Project.)

Material culture was a major supporting pillar of Egyptian colonization in Nubia. Objects travelled from Egypt towards the south and ended up in towns and cemeteries. Egyptian-style objects from New Kingdom Nubia include various pottery types, burial containers, funerary masks, shabtis, heart scarabs, various jewellery types, weapons, tools, cosmetic utensils etc. (Lemos Reference Lemos and Smith2020). These circulating global objects triggered change on local ground. Together with architecture and the transition from flexed burials deposited on funerary beds inside tumuli—typical of previous Nubian traditions—to Egyptian-style tombs containing extended burials, various categories of Egyptian-style objects excavated throughout Nubia worked as basis for interpretations of Nubian colonial society centred on the concept of acculturation or Egyptianization (e.g. Säve-Söderbergh & Troy Reference Säve-Söderbergh and Troy1991).

On the contrary, postcolonial theory allows us to propose counter, bottom-up narratives emphasizing not only local agency in contexts of cultural interaction (cf. van Pelt Reference van Pelt2013). On local ground, the patterns of the colonizer can also be used as evidence for Nubia's internal diversity and alternative, complex social relations.

Shifting centres and peripheries: towards Nubian diversity in the New Kingdom colonial period

The opposition between centres and peripheries originated with Dependence Theory and World Systems Theory in the 1970s and states that capitalism developed into a global market system that produced wealthy centres and poor peripheries in the global south (Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein2004). From a postcolonial perspective, perceptions of centres and peripheries can reproduce static representations of colonizers at the centre and colonized in the peripheries (Stein Reference Stein1999, 16–17). Postcolonial theory helps us deconstruct such views by emphasizing local agency and the creative potential of cultural interactions (Kaps & Komlosy Reference Kaps and Komlosy2013; Sulas & Pikirayi Reference Sulas and Pikirayi2020).

Centre-periphery perspectives have usually guided Egyptological interpretations of Nubia, especially during the New Kingdom, in which Nubia was considered marginal to the Egyptian ‘centre’ in a variety of ways. Such views also result from the fact that most of the discussed evidence for the New Kingdom comes from elite cemeteries at colonial administrative centres, despite fieldwork carried out in ‘peripheral’ areas in between those ‘centres’, e.g. the Batn el-Hajar (Edwards Reference Edwards2020), the Abri-Delgo Reach (Vila Reference Vila1975–1979) and, more recently, the Abu Hamed Reach (various chapters in Anderson & Welsby Reference Anderson and Welsby2014).

Evidence from the hinterland of colonial towns or ‘peripheral’ areas such as the Batn el-Hajar are usually discontinuous across the landscape and pose various challenges to interpretation. Edwards recently raised discussion on the role of isolated tombs in such areas. According to him, mortuary evidence from such locations, in contrast with evidence from formal cemeteries, ‘should not narrow our perspectives, to the exclusion from our narratives of the vast majority of the population who were buried otherwise’ (Edwards Reference Edwards2020, 396). Populations inhabiting areas in the outskirts of colonial towns have remained mostly silenced in historical narratives produced by a discipline traditionally focused on the Egyptianization of Nubia (e.g. Bietak Reference Bietak and Hägg1987, 122; Säve-Söderbergh Reference Säve-Söderbergh1989, 10).

The area between Amara West and Lower Nubia—the north Abri-Delgo Reach and the Batn el-Hajar—represents a gap in our knowledge of New Kingdom Nubia. Revisiting the evidence produced by various surveys in these today inhospitable areas is crucial for us to develop new comparative research (Donner Reference Donner1998; Edwards Reference Edwards2020; Nordström Reference Nordström2014; Vila Reference Vila1975–1979).

An example from Ginis West works as a starting point from which to test the potential of postcolonial approaches towards alternative interpretations of evidence from Nubian peripheries, considered as centres of other experiences. At Ginis West, archaeologists excavated tomb 3-P-50 (Fig. 3). The tomb was cut between the alluvial plain and bedrock. A few supporting slabs were used to reinforce the four subterranean chambers, accessible through a descending passage. The material culture retrieved inside the tomb suggests that it was used especially in the later New Kingdom.

Figure 3. Plan and part of the burial assemblage of tomb 3-P-50 at Ginis West: carnelian, jasper and shell penannular earrings, one of two faience shabtis of the ‘lady of the house’ Isis, and the fragments of a rare wooden headrest. (Plan redrawn by S. Neumann after Vila Reference Vila1975–1979 (vol. 5, 1977, 146, 151). Photographs: R. Lemos, courtesy of the Sudan National Museum and the DiverseNile Project.)

Archaeologists found scattered bones probably belonging to various individuals buried at tomb 3-P-50. The tomb was probably used collectively, as well as reused in later times. Traces of a Nubian-style tumulus superstructure have been recently detected on the surface (Lemos & Budka Reference Lemos and Budka2021). The combination of Egyptian-style underground shafts and chambers with tumuli superstructures has been previously detected in the region (Binder Reference Binder2014, 45; Smith Reference Smith2003, 200).

The material culture from tomb 3-P-50 suggests cultural affinities with both Egypt (colonizer) and Nubia (colonized). On the Egyptian side, there are various amulets, funerary implements and restricted objects such as two shabtis inscribed with a female name and title. On the contrary, penannular earrings made of stone and ivory/shell/bone would suggest cultural affinities with local Nubian patterns (Lemos Reference Lemos and Smith2020, 12).

Tomb 3-P-50 was located in the ‘periphery’ of major Egyptian colonial settlements (Sai and Amara West). Why did people decide to excavate an elaborate tomb and bury restricted Egyptian-style objects in a peripheral area? I have suggested elsewhere that collective engagement played an important role in the constitution of social relations in non-elite contexts characterized by overall scarcity in New Kingdom colonial Nubia (Lemos Reference Lemos2021, 265; Lemos & Budka Reference Lemos and Budka2021; see also DeMarrais & Earle Reference DeMarrais and Earle2017). A postcolonial perspective to this material would help us unveil alternative logics (i.e. collective engagement) behind those imposed by colonization and the adoption of foreign objects in local contexts (i.e. material standardization). Current fieldwork and research revisiting the material culture of peripheral areas in ancient colonial Nubia are still to centre the experiences of people inhabiting various peripheries in historical narratives about ancient colonial Nubia (e.g. Budka Reference Budka2019; Edwards Reference Edwards2020). However, evidence from well-known sites can also reveal the point of view of the colonized, which were mostly ignored in Egyptocentric narratives about Nubia.

Material colonization and object metamorphosis

When Reisner led the first part of the Archaeological Survey of Nubia (1907–8), he was unable to identify complexity and diversity based on the material culture he excavated in a cemetery at Shellal. According to him, ‘the scarabs, amulets and shabtis are identical in form, material and technique with similar objects being found in Egypt in the New Empire’ (Reisner Reference Reisner1910, 61). Others followed this perspective, including Steindorff, who believed that all shabtis from Aniba were mass-produced in Egypt and exported to Nubia with blank spaces within their inscriptions reserved for the names/titles of local owners (Steindorff Reference Steindorff1937, 75).

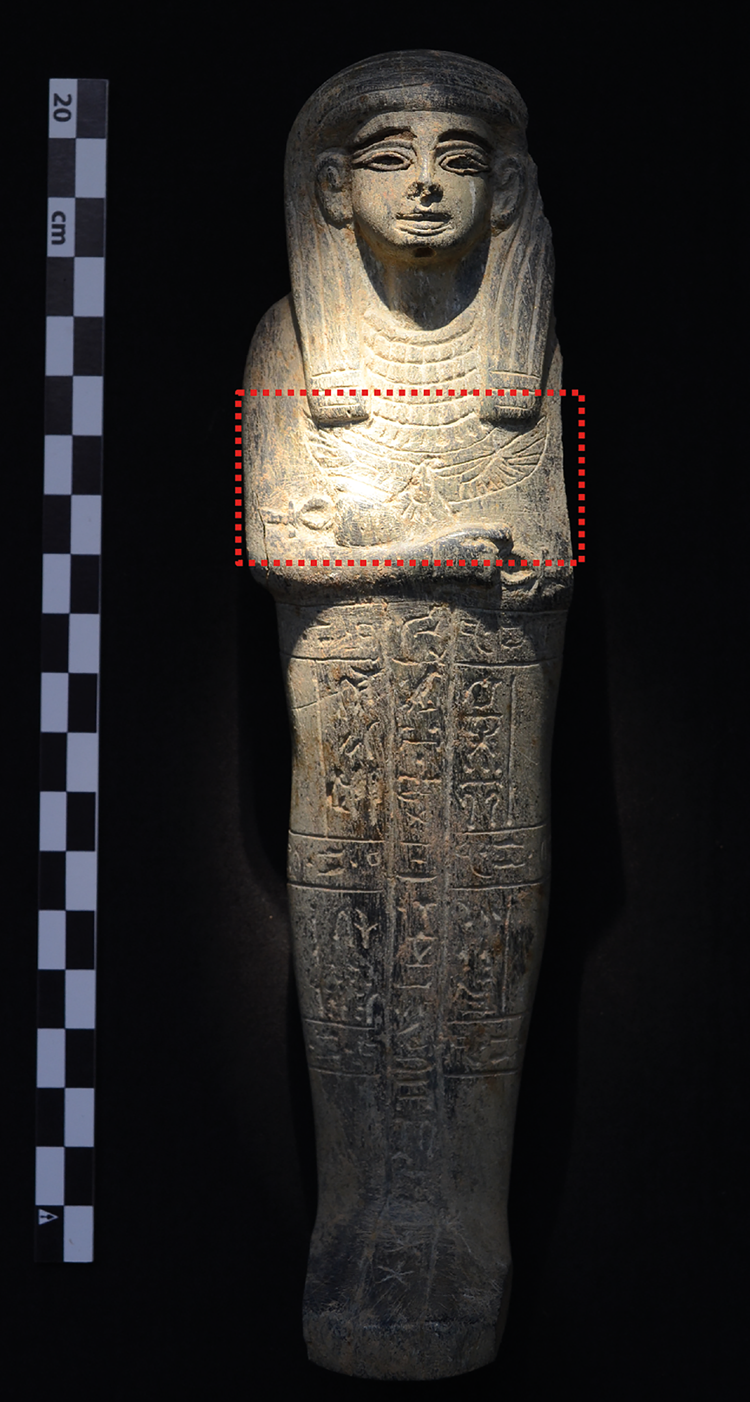

Various shabtis from Aniba do not bear names, but this mostly true for early imported 18th Dynasty stone shabtis (Auenmüller & Lemos Reference Auenmüller, Lemos and Leiden2021; Minault-Gout Reference Minault-Gout2011) (Fig. 4). However, this does not mean that imported Egyptian objects actually materialized standardization in New Kingdom colonial Nubia (Lemos Reference Lemos and Smith2020). On the contrary, imported shabtis (as well as other object categories) could be adapted to fit local expectations, a process which could result in completely transformed objects. This process of adapting and (re)creating patterns included later decorative elements added to imported shabtis to make them follow local demands for foreign objects (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Imported slate shabti with blank space for name/title from tomb S63 at Aniba. (Photograph: R. Lemos, courtesy of the Egyptian Museum Georg Steindorff, University of Leipzig.)

Figure 5. Imported soapstone shabti of wab priest Ti at Tombos Unit 30 (Smith & Buzon Reference Smith, Buzon, Spencer, Stevens and Binder2017, 624, courtesy of S.T. Smith & M. Buzon). Later elements were added on the earlier shabti, namely a vulture shaped feature on the figurine's chest. The same phenomenon is attested at other cemeteries, e.g. Sai (Minault-Gout & Thill Reference Minault-Gout and Thill2012, pl. 99).

Local alterations on stone shabtis were not limited to adding names and patterns onto preconceived imported shapes. Individuals living in the colony could also change the decorative scheme of such objects according to the material availability of, or access to, resources and skilled personnel, to make foreign objects fit local expectations. Moreover, foreign objects may have had their materiality completely altered, usually—but not only—by means of local (re)production. This resulted in different versions of foreign objects that basically performed local tasks, therefore creating different social relations, which would probably have had limited appeal to individuals in New Kingdom Egypt, but remained effective in Nubia. For instance, faience shabtis could be decorated following Egyptian-style patterns (Minault-Gout & Thill Reference Minault-Gout and Thill2012, plate 97a), but could also bear local decorative innovations, such as ‘unusual’ basket shapes on the back of some faience shabtis from Aniba and Sai (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Faience shabtis bearing unique basket styles from Aniba. Characteristic basket styles also come from Sai (Minault-Gout & Thill Reference Minault-Gout and Thill2012, pls 98, 99). (Photographs: R. Lemos, courtesy of Egyptian Museum Georg Steindorff, University of Leipzig.)

A postcolonial perspective on the ancient Nubian colonial past allows us to use imposed Egyptian patterns materializing foreign colonization in local contexts as evidence for local complexity and diversity in a context of imposed homogenization (Lemos Reference Lemos and Smith2020). Such a perspective draws mostly from Bhabha's contributions, even when not directly applying his concepts (e.g. van Pelt Reference van Pelt2013). This allows us to deconstruct the divide between colonizer and colonized towards unveiling highly complex and diverse socio-cultural relationships previously silenced in ancient colonial discourses and modern colonial interpretations.

Results of decolonial/’decolonizing’ archaeologies of Nubia: overcoming coloniality in the present

If postcolonial theory offers us a critical apparatus to understand and interpret past colonial situations from previously silenced perspectives and therefore overcome oversimplifying colonial narratives, decolonial theory allows us to situate ourselves in, and delink ourselves from the colonial matrix of power that defines our world system and produces geographical and social hierarchies. Decoloniality happens essentially in the present, while postcolonial criticism allows us to (re)interpret the past, which can also have present-day implications. Beyond alternative historical narratives about the ancient Nubian past ‘from below’,Footnote 1 examples of which I tried to outline in the previous section, decolonial theory has still to make its way into studies of the ancient Nile valley, especially considering Egyptology as a result of coloniality itself (contra Gertzen Reference Gertzen2020). Decolonial thinking has been slowly occupying space in the Nile valley. Most decolonizing efforts take the shape of collaborative archaeology, which should not limit the emancipatory potential of decolonial theory (cf. Fushiya Reference Fushiya and Smith2020). In addition, there have been attempts to revisit archival material and disciplinary histories with the aim of impacting not only the way we write about the ancient past, but—most of all—the way we position ourselves as scholars and practise our discipline within colonial disciplinary boundaries.

Carruthers (Reference Carruthers2020a) recently revisited archival material produced during the UNESCO Nubian campaign. He demonstrated that archives produced during that time represent the (post-)colonial context in which modern Nubian communities and their sites were usually ignored in the constitution of archaeological archives and historical narratives resulting from those archives, which only focused on the ancient past. The immense data sets produced during the UNESCO Nubian campaign only offer ‘fleeting glimpses of Nubian communities just prior to their removal’ (Edwards Reference Edwards2020, 6; see also Fernández-Toribio Reference Fernández-Toribio2021, 437–40).

Post-colonial (with a hyphen) archaeologies in Egypt and Sudan have traditionally ignored local communities within a nationalistic setting. State/elite interests usually differ from those of local communities, which results in their removal from their traditional homelands and later negotiations of memory (Agha Reference Agha2019,; Hassan Reference Hassan2007, 85; Janmyr Reference Janmyr2016). In Sudan, clashes between local communities and archaeologists carrying out salvage excavations prior to the construction of the Merawi Dam express the current state of affairs in the Nile valley, which can be understood within the framework of coloniality (Kleinitz & Näser Reference Kleinitz and Näser2012).

Decoloniality has not fully made its way to Sudan and Nubia yet, although a few projects can be classified as examples of ‘decolonizing’, instead of ‘decolonial’ archaeologies. Current excavations in Sudan are increasingly involving local communities in decision-making processes regarding the writing of local histories and the management of local heritage sites, which materializes, for instance, in children's books, community centres, academic books and other resources in local languages (Fushiya Reference Fushiya2017a; Reference Fushiya2017b; see also Fushiya et al. Reference Fushiya, Ahmed, Sorta and Taha2017; Fushiya & Radziwiłko Reference Fushiya and Radziwiłko2019; Näser & Tully Reference Näser and Tully2019; Tully & Näser Reference Tully and Näser2015). Bradshaw (Reference Bradshaw2018) demonstrated that the most common question local communities in Sudan/Nubia ask about archaeology is ‘What is the benefit?’. Beyond collaboration, delinking Nubian archaeology from the colonial matrix of power within which it was born would also include development. From a decolonial perspective, the socio-economic development of impoverished local contexts today should be informed by other ways of thinking about and doing things, which would result in a pluriversal ethics (Hutchings Reference Hutchings2019). Politically engaged, decolonial archaeologies, in the end, will allow us to question colonial inequalities, which today define what we understand as heritage, but also to disconnect archaeologists and local communities—both understood as products of coloniality—from the colonial matrix of power (González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado2018; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2018; Londoño Reference Londoño and Wassilowsky2013).

Decolonizing Nubian archaeology from a decolonial perspective can also benefit from current debates in global history. Today, there is little space for non-European epistemologies to arise from the work of scholars outside the colonial mainstream (Langer Reference Langer2017b; cf. Carruthers Reference Carruthers2020b; Meskell Reference Meskell2018). If postcolonial theory allows us to bridge centres and peripheries in the past, scholars should place coloniality at the centre of discussions in Sudanese/Nubian archaeology in order to overcome such static binary divisions in practice today. Local Sudanese and Nubian epistemologies and forms of inhabiting the world are crucial for us to overcome modern/colonial definitions and practices of archaeology and heritage in Sudan and Nubia, although inputs from worldviews of the African Diaspora in the Americas are equally important, especially in the light of the impact of the Atlantic slave trade in all parts of Africa (Klein Reference Klein1990; Leopold Reference Leopold2003).

More than rewriting histories of colonized Nubia in antiquity or reassessing the discipline's colonial history—which lie within the scope of postcolonial theory—decolonizing ancient Nubia is about how the ancient past is (re)enacted today. Similarly to cases in South America (Londoño Reference Londoño2021), the Nubian past has been removed from the local contexts where it was produced: in archives, archaeological practice and in history books. Postcolonial theory allows us to rewrite history books. Engaging with decoloniality brings reparation through enabling alternative ways of being-in-the-world to shape decolonial futures from the cracks.

There has been limited clear theoretical engagement between Sudanese and Nubian archaeology and the field of Indigenous archaeology (especially in the Americas). However, various common aspects indicate ways forward from ‘decolonizing’ efforts to proper decolonial archaeologies of Sudan and Nubia that could help us bridge the gap between past (discourse) and present (practice). Indigenous archaeologies in the Americas have made important progress decentring narratives from nation-state ideologies that disconnect Indigenous groups from their heritage. Such nationalistic narratives have resulted, as in the case of South America, in dispossession (Londoño Reference Londoño2021; see also Cipolla Reference Cipolla, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2020; Schneider & Hayes Reference Schneider and Hayes2020). Nationalistic discourses have also marked, in different ways, the African continent (Lane Reference Lane2011), where modern archaeology helped legitimate dispossession (Hassan Reference Hassan2007).

Decolonial archaeologies of Sudan and Nubia should transcend the past/present divide and move away from approaches either exclusively emphasizing alternative, bottom-up histories of past realities or present-day collaborations with Indigenous and local populations. On the contrary, Indigenous archaeologies have shown the devastating potential of universalizing, nationalistic historical narratives upon Indigenous groups and how action drawing from Indigenous ontologies can impact not only politics and heritage management, but also how we write history. Similarly, moving current debates in Sudan and Nubia forward would imply exploring the connections between postcolonial theory and decolonial theory, which would result in alternative histories with more clear practical implications in the present, drawing from Indigenous inputs to theory (Atalay Reference Atalay2006).

Bridging postcolonial and decolonial theory would allow us to overcome the theory/practice divide and produce a type of ‘practical theory’, similar to ethnographic theory as defined by da Col and Graeber (Reference da Col and Graeber2011, vii–viii):

a conversion of stranger-concepts that does not entail merely trying to establish a correspondence of meaning between two entities or the construction of heteronymous harmony between different worlds, but rather, the generation of a disjunctive homonimity, that destruction of any firm sense of place that can only be resolved by the imaginative formulation of novel worldviews.

Bridging postcolonial and decolonial theory would expose both scholars and agents (ancient and modern) to each other, which would result in alternative histories that do not only unveil silenced concepts and practices, but also narratives that produce change based on these silenced concepts and practices. Because such narratives would draw from ancient and modern concepts and practices (which are entangled in Nubia today through material culture and heritage), they become useful tools of emancipation from present-day inequalities which characterize both ‘Us’ and the ‘Other’—both scholars and agents (see Graeber Reference Graeber2015, 6–7).

Bridging postcolonial and decolonial theory in ancient Nubia: narratives of reparation

No explicit attempt to address postcolonial theory and decolonial theory has been published so far within Sudanese and Nubian archaeology. On the one hand, archaeologies of Nubia influenced by postcolonial theory have produced more complex historical narratives of colonial periods, especially the New Kingdom. On the other, decolonizing and (potentially) decolonial archaeologies of Nubia have mainly focused on living communities in Sudan and the heritage aspect of ancient remains.

Current research projects in Nubian archaeology point towards an existing divide between theory and practice regarding postcolonial and decolonial thinking. While postcolonial theory produces counter-narratives of the New Kingdom colonization, archaeologists trying to ‘decolonize’ Nubian archaeology are engaged in collaborative archaeology projects, which impact everyday lives in the present, but little affect established scholarly interpretations of the past. Those not working in collaborative archaeology projects, which can more easily assess the impact of coloniality/archaeology upon living communities, are left with the discursive realm as their political arena. Nevertheless, the practical impact of scientific and historical narratives upon living communities cannot be denied. For example, historical interpretations of Egypt as an African country are extremely contested (cf. M'Bokolo Reference M'Bokolo1995; Smith Reference Smith, Bács, Bollók and Vida2018; Wengrow et al. Reference Wengrow, Dee, Foster, Stevenson and Ramsey2014). One could argue, for this and other cases, that postcolonial theory is a necessary methodological step to deconstruct narratives that legitimate oppression prior to practical attempts to decolonize from the perspective of decoloniality.

The current divide between theory and practice, past and present, postcolonial narratives and decolonizing practice finds its roots in modern archaeological practice in northeast Africa. For example, despite producing immense data sets that are today crucial for us to understand socio-cultural complexity in the Nubian past, the UNESCO Nubian campaign also contributed to settling the current state of affairs between archaeology and other stakeholders.

Much has been discussed regarding the legacies of the UNESCO Nubian campaign (e.g. Adams Reference Adams2007). However, among the less emphasized aspects of the campaign are its epistemological implications, which ended up reinforcing the much less documented displacement of modern Nubian communities from their traditional spaces (in comparison with the large amounts of archaeological information; cf. Hopkins & Mehanna Reference Hopkins and Mehanna2011). For example, broadcaster Rex Keating provides a popular account of the practical implications of the epistemological nature of the UNESCO Nubian campaign:

An amusing indication of how Nubians feel about their forebears was provided by the Spanish Expedition from Madrid who were digging an early C-Group cemetery, among the scattered houses of a modern village. Each morning with unfailing regularity an old woman appeared on the dig to lay claim to the property of her ‘ancestors’ as she described these people who died at least 4,000 years ago. She demanded half of all the pots and human remains found, ‘but you can keep the cattle horns.’ She could be silenced only by the leader of the expedition, Dr. Blanco y Caro, demanding that she, in return, pay half the costs of running the expedition. (Keating Reference Keating1962, 90–1; my emphasis)Footnote 2

Such an attitude that disconnects past and present is further reinforced by certain historical narratives that little take into consideration the present-day nature of historical/archaeological narratives, despite cultural practices that connect past and present today; e.g. the production and use of traditional funerary beds in Nubia (Lehmann Reference Lehmann2021; see also Kendall Reference Kendall, Donadoni and Wenig1989).

Narratives focusing on the ‘origins’ of Nubians have further impacted the way modern communities are considered as having no relationships with the ancient past. For example, previous approaches based on Classical authors and obscure linguistic evidence proposed that an outside Nubian ethnic group—the Noubades—invaded the region following the decline of the Meroitic empire (Kirwan Reference Kirwan1937; cf. Lenoble & Sherif Reference Lenoble and Sherif1992). These narratives, which greatly impacted our understanding of cultural change in Late Antique Nubia, have been challenged more recently by archaeological evidence for cultural change from the post-Meroitic period to the early Christian Nubian kingdoms, which included complex contextual borrowings from both ‘pagan’ and Christian traditions (Edwards Reference Edwards, Dijkstra and Fisher2014, 411–12; Lebedev & Reshetova Reference Lebedev and Reshetova2017; Näser et al. Reference Näser, Tsakos and Weschenfelder2021). However, more than impacting our understanding of complex cultural transitions from ancient to medieval Nubia, narratives emphasizing a later Nubian invasion also contribute to separating modern Nubian communities from their ancient past, which plays a major role in reinforcing colonial inequalities today and delegitimize local claims to history.

To conclude, I would like to develop the idea of narratives of reparation, which I believe can help us to be more explicitly theoretical and assess the impact and decolonial potential of our histories of ancient colonial Nubia, which can be politically useful in today's struggles for equity and reparation beyond the critique of disciplinary histories and collaborative projects alone. Narratives of reparation work as a bridge between a theoretically informed, critical first step and political action promoting our delinking from coloniality.

Coloniality—the colonial matrix of power that shaped modernity and its inherent inequalities—did not exist in the ancient past. However, it is undeniable that the ancient past worked as a crucial supporting pillar of modernity/coloniality, for instance, through race and narratives on the ‘origins of Western civilization’ (see Carruthers et al. Reference Carruthers, Niala and Davis2021; McCoskey Reference McCoskey2012) or previously discussed narratives on an alleged Nubian invasion. Therefore, modernity/coloniality and the ancient past are essentially entangled in historical narratives that create and legitimate practices that reinforce colonial inequalities.

Revisiting the ancient past with a critical, postcolonial mind-set allows us not only to rewrite history, but also to contribute to dismantling coloniality and its social and academic inequalities through narratives that promote reparation (i.e. to give back stolen pasts to Indigenous communities through narratives that connect people and their heritage). Alternative histories of New Kingdom or Late Antique Nubia therefore become narratives of reparation in the sense that they open space for silenced past epistemologies to merge with ways of being-in-the-world silenced by coloniality/archaeology today.

Narratives have the potential either to connect or disconnect agents, historical situations and us. Bridging postcolonial and decolonial theory through narratives of reparation can help us reassemble what has been undone and offer compensation—similarly to what can be done through archives of displacement. Archives, historical narratives and archaeological practice cannot be dissociated if we aim to make archaeology a tool to achieve social justice. In this way, narratives of reparation are essentially decolonial in the sense that readdressing history can promote decolonial healing—in the case of Nubia, by reconnecting modern communities to their past in a way that can be as effective as inclusive ways of managing heritage through collaborative archaeology. Allying counter-narratives about the past with decolonial practice today exposes us to one another, and therefore promotes decolonial healing diversity.

Alternative histories of the past from a postcolonial perspective then become decolonial tools. As such, they become narratives of reparation that revert modern scholarly epistemicide of Indigenous/colonized groups such as Nubians past and present. Narratives of reparation bridge postcolonial and decolonial theory because past agency becomes a tool for dismantling the intellectual foundations of coloniality that place Indigenous communities in the Middle Nile today at the bottom of hierarchical scales of power.

Narratives of reparation inspired by postcolonial theory and modern Indigenous inputs to history writing also give back dignity to past actors, something which was stolen twice from them—first by ancient colonizers and later by modern scholars within a colonial epistemological milieu. But also, from a decolonial perspective, they inspire action and other, more conscious appropriations of the ancient past, which turns archaeology into a powerful tool towards social change.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the members of the Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies Research Group at the State University of Santa Catarina, Brazil for organizing a very productive group discussion of an earlier draft of this paper. I am also grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.