Be ye not arrogant against me, but come to me in submission.

The story of the Queen of Sheba climaxes with King Solomon’s threat to conquer her paradisaical oasis and usurp her Mighty Throne. King of the world, Solomon was a “warfaring man” and “a very good conqueror who rarely rested from invading. Whenever he heard of a king in any part of the world, he would come to him, weaken him, and subdue him.”Footnote 1 He would load “people, draft animals, weapons of war, everything” on carved wood, and command “the violent wind to enter under the wood and raise it up” and “the light breeze” to carry them – the distance of a month in one night to wherever he wished (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 171; see also Qurʾan 34:12, 38:36–39). When Solomon heard of the sovereign Queen of Sheba, much to his astonishment, he immediately set out to conquer this “last kingdom not yet under his control.”Footnote 2 He did not need to take his extraordinary army of demons, ʿifrits, and shaytans, jinnsFootnote 3 (genies) and humans, birds and beasts flying on the wings of the wind. He sent his spy/messenger bird, the little hoopoe (hudhud), to the queen armed with a letter and instructed the bird to wait for her reply. His message was brief: “Be ye not arrogant against me, but come to me in submission” (Qurʾan 27:31); that is, submit or be destroyed.

Who was the Queen of Sheba, and why did Solomon wish to attack her paradisaical “Garden”?

The story of the encounter between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba appears in the three Abrahamic scriptures but none identifies her by name. Only in the Kebra Nagast, the revered Ethiopian book of kings, is she named, as Makida (Wallis Budge 2007). The Quranic version of the story of the Queen of Sheba is part of Sura 27, known as al-Naml, meaning “the Ant.” It belongs to the middle group of Meccan suras (Pickthal Reference Pickthaln.d., 272) and was revealed to the Prophet nine years after he claimed prophecy (Rahnema Reference Rahnema1974, 189–229). This sura is composed of ninety-four ayahs (verses), in which verses twenty through forty-four include the mesmerizing story of the fateful encounter between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.Footnote 4 The Quranic story is short, condensed, and inconclusive regarding their ultimate fate, leaving much to the imagination of generation after generation of individuals to construct and reconstruct it according to the sensibilities of their time and culture.

While she is the only queen mentioned in the Qurʾan, she is not the only woman left unnamed.Footnote 5 Except for Mary, mother of Jesus, no other woman – some twenty or so – is identified by name. All these women, except for the Queen of Sheba but including Mary, are situated in relation to a man, as mothers, wives, or daughters. Only the Queen of Sheba is identified by her position: that of a sovereign queen – an independent woman with political authority. The issue of why women are not named in the Qurʾan demands greater scholarly attention. But for my purposes here, and contextualizing the issue historically, I would argue that the specificity of women’s names is not the point of the Quranic revelations; the enduring significance of kinship relations is. Similarly, the Queen of Sheba’s name is immaterial to her position as a queen. The rationale behind it, in my view, is one that renders female sovereignty a likely story, a general principle or a rule that may be utilized by other women at other historical junctures. Indeed, this was the logic used by Mrs. Shahid Salis, one of the Iranian women presidential contenders I interviewed in 2001, mentioned in the Preface. Had the queen been given a name, her position would have become specific to that person and for that particular time.

Popularly, however, the Queen of Sheba is known as Bilqis.Footnote 6 But why Bilqis? The origin and meaning of the name is unclear, though Montgomery Watt suggests that it may be rooted in the Greek term pallakis, and its Hebrew equivalent, pilegesh – Arabic bilqis – meaning “concubine”Footnote 7 (Haeri Reference Haeri and Altorki2015, 100–101). Bilqis is thus another identity marker based on a position, that of a concubine! “Demonizing” the Queen of Sheba, Jewish and medieval Muslim sources demoted her from the exalted position of queen to that of a concubine, a sex object – a bilqis. But popularly and across many cultures, she has remained the unforgettable Queen of Sheba.

Over many years and across many different cultures, religions, races, and ethnicities, infinite variations of the story of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to the court of King Solomon have been told and are still being told. Back-and-forth cultural borrowings and diffusions have added layers of meanings, metaphors, and symbolism to this story, making it a truly transnational and transcultural story, infused with universal themes and cultural specificities. Yet across all cultures, one impulse remains dominant: the Herculean patriarchal effort to conquer her “Garden,” appropriate her authority, banish her from the public, restrict her mobility, and control her body.

In the following pages I describe and discuss at some length the Quranic story of the encounter between the Queen of Sheba and the Prophet-King Solomon, interwoven with its imaginary – and often entertaining – reconstructions by medieval Muslim biographers and storytellers. The inconclusive, enigmatic, and abbreviated narratives in the Qurʾan, as well as the silence of the scripture regarding the fate of both king and queen, have left multitudes of people from different cultures and faiths wanting to know what exactly transpired in that dramatic encounter and the exchanges – gifts, wits, and all – between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Sages, scholars, Sufis, creative artists, poets, musicians, and storytellers have been intrigued by this fairy tale of a cosmic gender encounter. For most of them, sex and violence, love and marriage, take the center stage, despite their absence in the Quranic revelations. The patriarchal discourse of might and righteousness thus reproduced through the retelling of the story reaffirms the “natural” differences between the sexes, appropriates the divine word, and legitimates male domination and control, but not without ambivalence. After all, the queen’s sovereignty is the subject of revelations in the Qurʾan. Muslim scholars have thus had to balance the rather positive image of a thoughtful woman political leader in the Qurʾan with its purported condemnation in a prophetic hadith, “Never will succeed such a nation as makes a woman their ruler,” as I discuss in Chapter 2.

Much of the scholarly writing about the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon concerns a debate about which is the “true,” the “earliest,” or the “original” version of the tale.Footnote 8 What interests me is what the story tells us about women and political authority. I am interested in the queen’s leadership and charisma, in her wisdom and genuine concern for her people’s lives, in her sustained diplomatic effort to negotiate peace with a much stronger and uncompromising adversary. I read this story as an example of desirable leadership, regardless of gender; as one that values negotiation over domination, peace over war and destruction.

To understand the transcultural staying power of this Quranic story, we need to frame it within the context of its many patriarchal reconstructions by medieval Muslim exegetes, chroniclers, and biographers. Inasmuch as the story of the queen’s sovereignty in the sacred texts has captivated creative imaginations, it has confounded the exegetes and confronted them with moral and political dilemmas regarding women and political agency, mobility, and sexuality. They have vacillated between praising the trappings of her authority – the majesty of her Mighty Throne, the unparalleled gifts she sent to Solomon – and simultaneously condemning her for her transgression against the “natural” patriarchal order, for usurping male authority, and for not being a fully human woman. The chroniclers’ ambivalence toward women’s political authority and their wish to differentiate it from, and subordinate it to, male authority seems to have led them to anxious exaggerations of the queen and the source of her power. Demonizing the Queen of Sheba, Jewish sources view her as “a supernatural being with seductive sexual power and an intention to kill infants in their cradle” – a Lilith (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 21; Silberman Reference Silberman and Pritchard1974, 84). Muslim medieval biographers, including Thaʿlabi and Tabari, also question her humanity and argue that the queen was human on her father’s side and a jinn from her mother’s, a jinn princess from whom the queen inherited hairy, donkey-like legs. But Muslim scholars have also had to balance their ambivalence and negative characterization of the queen with the positive Quranic image of her political authority. In this chapter I juxtapose the Quranic story with its patriarchal version in which the queen is defeated, her Mighty Throne appropriated, and her mobility is curtailed through concubinage/marriage.

In the following pages, I first position King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba within their kinship and genealogical parentage, pedigree, and position – historical or fictional – as reconstructed by medieval Muslim scholars and biographers, before moving on to discussing the Quranic revelations. Knowledge of the king’s and the queen’s purported kinship and religious and political backgrounds situates them within the patriarchal scheme of the medieval power structure, cosmology, and gender hierarchy, from which I intend to retrieve the queen’s political authority and peace-building activities.

Kinship and Genealogy: Situating King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

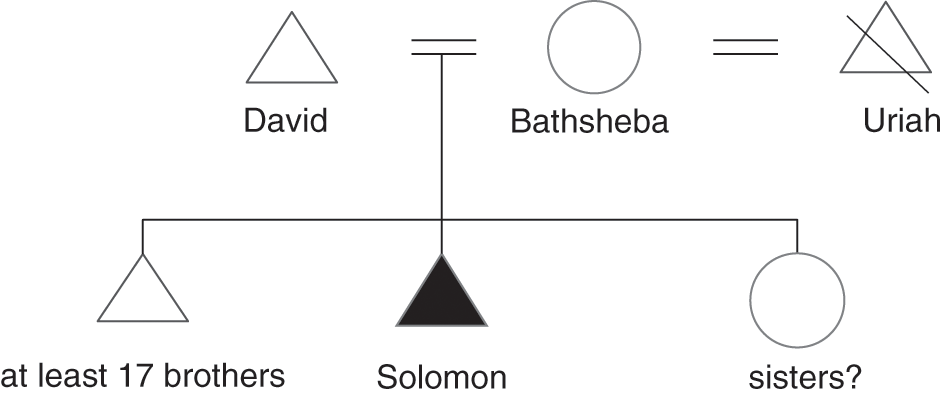

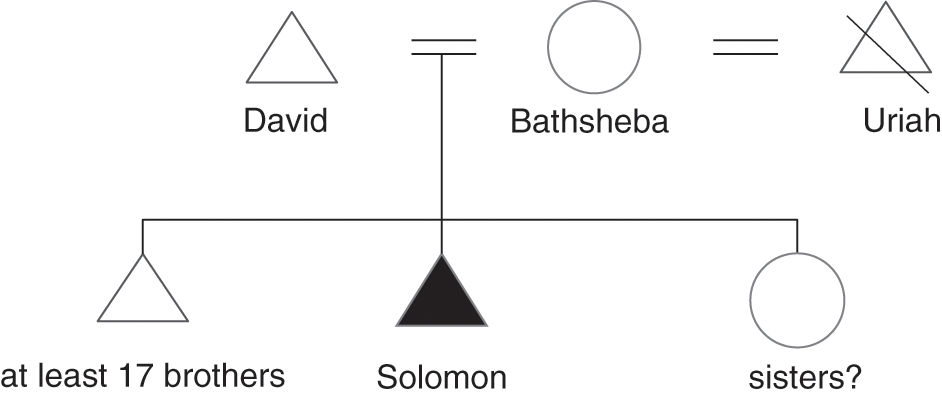

Solomon: Man-God

Muslims and Jews agree that Solomon, son of David, was both a mighty king of Israel and a Prophet of Islam. But they differ on some crucial details surrounding his exalted birth. Jewish and Muslim stories both maintain that King David was on the roof of his palace chasing a “golden dove” when he saw Bathsheba, wife of Uriah, bathing. Smitten by Bathsheba’s flawless beauty, King David arranged for Uriah, a war hero in his army, to be killed in battle, which then freed David to marry Bathsheba (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 252, n. 101). While medieval Muslim biographers tell the same story, they assert that it was Satan disguised as the golden dove who misled David to the edge of the palace roof from where he saw Bathsheba (Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 144–147; 1994, 152–153). In this Islamic version, while David did connive to have Bathsheba’s husband killed in battle (for which he later repented and was forgiven), his action was mitigated by the fact that he did so over the course of two – or three – wars. He then dutifully abstained from consummating the relationship with Bathsheba, allowing her to complete her ʿidda, the four-month period of sexual abstinence obligatory for Muslim widows, before actually marrying her (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 469; Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 148–149). Thus was born Solomon (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 King Solomon’s Genealogy

In the Quranic story, the son is not held accountable for his father’s indiscretion. God showers Solomon with favors, despite some personal imprudence – large and smallFootnote 9 – and lavishes incredible riches and power upon him, granting him unrivaled political authority and supernatural clout.Footnote 10 God grants Solomon the ability to understand the languages of birds and bees, to command humans, demons, and jinn, and authorizes the wind to stay in his service to facilitate rapid transit for him and his extraordinary army anytime he wishes (Qurʾan 27:16–17; 34:12; Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 491; Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 154). The supernatural jinn live among humans, and just as humans, some are good and some are evil (Qurʾan 72, 14). King Solomon’s powerful army stretched out over “one hundred parasangs [about three miles]: twenty-five of them consisted of humans, twenty-five of jinn, twenty-five of wild animals, and twenty-five of birds” (Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 154; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 69). “Solomon ordered the violent wind and it lifted all this, and ordered the gentle breeze and it transported them. God inspired him while he was journeying between heaven and earth” (Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 154), and reminded him further, “Lo, I have increased your rule that no creature can say anything without the wind bringing it and informing you” (Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 154).

Solomon’s riches extended to his harem. He amassed some “one thousand houses of glass on the wooden [carpet],Footnote 11 in which there lived 300 wives and 700 concubines” (Tabari 1994, 161). While some Jewish and Muslim sources have expressed skepticism regarding the exact number of women in the king’s enormous harem, others have disputed the exact ratio of wives to concubines: was it 300 wives to 700 concubines or 700 wives to 300 concubines?Footnote 12 (Tabari, Reference Tabari and Brinner1991; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 239, n. 79). Well, said Victorian author Rudyard Kipling, “in those days everybody married ever so many wives, and of course the King had to marry ever so many more just to show that he was the King” (Reference Kipling1907, 231). Some sources tell us that Solomon had “the sexual potency of forty men, and clearly he needed it” (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 86) – though apparently most of his wives were “horrid,” as Kipling humorously concluded in his story “The Butterfly that Stamped.” No wonder, then, muses Lassner, that “for all this prodigious lovemaking, he could produce only a single progeny.” Still, powerful, perfect, and potent, Solomon was said to be “the greatest of all lovers” (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 86). But so much power needed to be balanced by wisdom and tempered with justice. That, too, God granted him. Accordingly, Solomon would grow up to be exceedingly intelligent and wise, and his justice and judgments universally recognized. Above all, God gifted Solomon a miraculous ring carved with “His”Footnote 13 ineffable name that “opened all doors,” in Qaʾani’sFootnote 14 poetic rendition (Sattari Reference Sattari2002, 105). The eleventh-century chronicler Muhammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisaʾi elaborates further:

To ensure Solomon’s domain over forces natural and supernatural, Gabriel dusted off the signet ring of God’s Vice Regent, which had been lying about paradise almost since time immemorial. That is, when Adam had been expelled, it flew from his finger and returned to its place of origin.

Nothing moved without Solomon’s knowledge. The patriarch’s power was absolute – almost divine. He was at the peak of his power and global dominance when his spy bird, the little hoopoe, informed him of the sovereign Queen of Sheba and her Mighty Throne.

The Queen of Sheba: Jinn-Woman?

Who was the Queen of Sheba? Was she a sovereign head of her state and the commander-in-chief of her peaceful and prosperous oasis? Was she the commander of the faithful, even if she worshiped the Sun God? Or was she an apparition, a jinn of sorts, of a powerful and autonomous woman – deadly and dreadful to patriarchs and patriarchy? Some say the Queen of Sheba was a virgin beauty from Ethiopia, others say from Yemen and Southern Arabia, but no one really knows. By all accounts, the queen’s leadership, grace, intelligence, and wisdom held universal appeal. Little wonder, then, that the story of her sovereignty and the mystery of her relationship with Solomon – political and sexual – continues to captivate the popular imagination. Her story has inspired many renowned artists, sculptors, architects,Footnote 15 musicians,Footnote 16 filmmakers,Footnote 17 painters, and miniaturists throughout the ages in eastern and western societies – and in some African countries, most notably in Ethiopia. Popular cultures and folk imaginations have also transformed this remarkable transnational story of an intelligent and thoughtful queen to suit their own cultural sensibilities and fantasies.

As with Solomon, God bestowed on the Queen of Sheba “something of everything,” including sovereignty of an idyllic oasis – a paradisaical “Garden” somewhere in Yemen or Southern Arabia, or in Axum in Ethiopia (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 525; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 77). In the Qurʾan the queen is portrayed as a wise, just, and caring ruler from whom God has denied no bounty or riches. Above all, God has given the queen a magnificent Mighty Throne (ʿarsh‐i ʿazim; Qurʾan 27:23). “Of all the implements that became symbols of Solomon’s authority,” writes Lassner, “none, including perhaps his signet ring, received such prominence in so wide a variety of cultures as did this legendary throne” (Reference Lassner1993, 77). Thaʿlabi describes Queen of Sheba’s throne:

The front of her throne was of gold set with red rubies and green emeralds, and its back was of silver crowned with jewels of various colors. It had four legs: one leg of red ruby, one of green sapphire, a leg of green emerald, and a leg of yellow pearl. The plates of the throne were of gold. Over it were seventy rooms, each with a locked door. The throne was eighty cubits long and rose eighty cubits in the air.

With no hint of irony, however, Thaʿlabi then goes on to claim that it was the queen herself who ordered the throne to be made for her (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 525). Was it not God Almighty who had given her that magnificent and Mighty Throne, just as “He” had given the signet ring to Solomon (Qurʾan 27:23)?

The queen’s military arsenal and army, however, paled before that of the awesome firepower of King Solomon. Hers was entirely made up of human beings with no supernatural creatures or celestial forces to perform mighty deeds or magical tricks. But then, lest we forget, the queen’s mother was a jinn princess with supernatural power, and the queen herself was “brought up among the jinn” (Jeenah 2004, 56; see also Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 171).

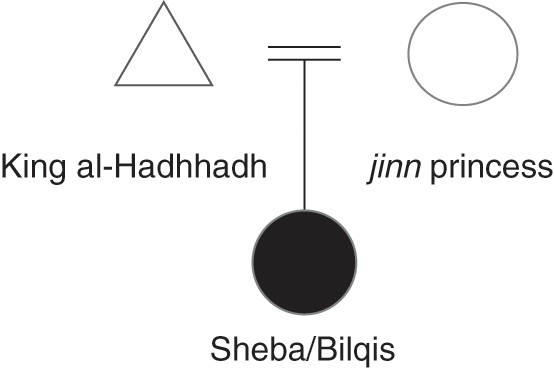

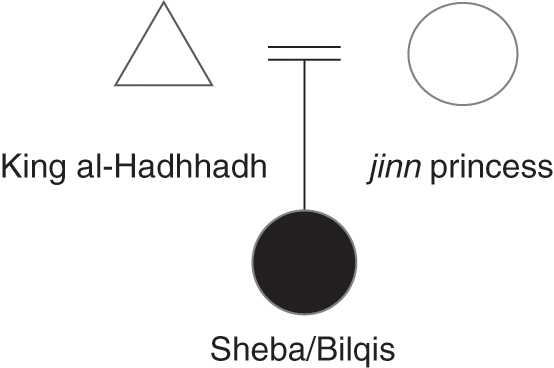

Significantly, while we hear nothing about the queen’s parentage in the Qurʾan (unlike Solomon son of David), medieval Muslim biographers and storytellers have written extensively on and repeatedly recounted her mixed parentage and genealogy. Popularly known as al-Hadhhadh, we are told that the queen’s father was a “mighty king and the ruler of all the land of Yemen” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 523). One day, the story goes, the king was out hunting when he saw two serpents locked in combat; one was black, the other white. As the black serpent was about to overpower the white, the Yemenite king intervened and killed it. With that he broke the curse on the white snake, who happened to be none other than the king of the jinnFootnote 18 (Stowasser Reference Stowasser1994, 153, n. 8; Tabari 1994, 166; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 169). In gratitude the king of the jinn offered his daughter’s hand to the king of Yemen, who was only too happy to marry the princess jinn, for he “disdained” to marry any of the daughters of local dignitaries, whom he found beneath his status. This “haughty” attitude of the father, Thaʿlabi tells us, was inherited by his daughter Bilqis (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 523; Sattari Reference Sattari2002, 127–128). Thaʿlabi also relates a hadith from a close companion of the Prophet of Islam that “One of the parents of Bilqis was a jinni” (Reference Sattari2002, 523). Ibn ʿArabi, the thirteenth-century mystic philosopher, however, identifies Bilqis with “divine wisdom” because she “was both spirit and woman since her father was one of the jinns and her mother a mortal being” (Schimmel Reference Schimmel1997, 59). In those days it was not unusual for jinn and humans to fall in love and that’s how the King of Yemen married a jinn princess (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 523; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 50).

Thus was born the beautiful Bilqis (aka the Queen of Sheba) from the union of a jinn mother (or father) and a human father (or mother) (Figure 1.2). Whether from her mother, her father, or both, Bilqis inherited supernatural power and carried it in her veins. As an only child,Footnote 19 Bilqis grew up to learn, conceivably, magical power and transfigurationFootnote 20 from her mother, and authority and leadership from her father. Some say she was thirty years old, long past the customary age of marriage, when her father died. She then succeeded him as the Queen of Yemen.Footnote 21 In some accounts a male rival emerged to contest her authority and for a time ruled over parts of Yemen (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 50–51), but he turned out to be a ruthless leader, particularly violent toward women, whom he would deflower before their husbands (van Gelder Reference Van Gelder2013, 117). Outraged at his behavior and responding to the plea of the Yemenites under this tyrant’s rule, Bilqis planned a daring strategy. She proposed to marry him and he accepted happily, despite his advisers’ opposition. In his palace as his bride, she arranged to get him drunk, and “in a move symbolic of removing his improperly overactive genitalia, she severed his head and hung it from the palace before slipping away under cover of night” (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 75–76). Applauding her liberating action, the Yemenites hailed her as their savior and leader: “You are worthier than anyone of this realm” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 524; see also Van Gelder Reference Van Gelder2013, 118). And so Bilqis became the Queen of Sheba, establishing her rule firmly and became the unrivaled sovereign of Yemen.

Figure 1.2 Queen of Sheba’s Genealogy

Acknowledging the Queen of Sheba’s strategic planning to free her people from the tyranny of a decadent and morally corrupt ruler (an ironic twist on the alleged Prophetic hadith), Thaʿlabi then goes on to relate a hadith from Ibn Maymunah, tracing the chain of his transmissions all the way back to caliphs ʿAli and Abu Bakr, stating that when Bilqis was mentioned in the Prophet’s presence, he said, “Never will succeed such a nation as makes a woman their ruler” (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 524; see also Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 52).

Did Thaʿlabi – and Ibn Maymunah – have momentary lapses of memory? Did Thaʿlabi via Ibn Maymunah not just tell us about a heroic Queen of Sheba who saved her people from the tyranny of a violent and corrupt ruler? Did they overlook that the Prophet of Islam received revelations about the Queen of Sheba and her diplomatic attempts to save her people from certain war and destruction?

The Queen of Sheba in the Qurʾan

Lo! I found a woman ruling over them, and she has been given (abundance) of all things, and she possesses a Mighty Throne.

According to the Qurʾan, neither King Solomon nor the Queen of Sheba had any knowledge of the other. It is the little hoopoe, Solomon’s spy/guide that makes them aware of one another.Footnote 22The story begins with Solomon reviewing his extraordinary army. Not finding the hoopoe among the flock, he flies into rage, vowing to punish the bird by having itsFootnote 23 feathers plucked or slaughtering it unless it has a good excuse (Qurʾan 27:20–21).

Why the temper tantrum and the promise of such unusual and cruel punishment? Medieval sources have provided several reasons for the king’s anger and justification for his threat of harsh punishment. The hoopoe, according to the Perso-Islamic traditions, has the ability to see water underground (Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 157; Rumi, Masnavi 1, 89–91; Paydarfard Reference Paydarfard2011). The reason for the King’s rage, we are told, was that it was time for him to perform his prayer ablution and he needed water to do so (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 521; Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 157–158).Footnote 24 Soon the hoopoe returns to Solomon’s camp and, thank goodness, he does have a good excuse. The little bird tells its master that it has come to know of something as yet unknown to the King. The hoopoe then tells Solomon all about the Queen of Sheba and her prosperous oasis and how God has given her something of everything, including a Mighty Throne (ʿarsh-i ʿazim) – “the tools and equipment in her dominion” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 525). The only problem, the hoopoe explains to an incredulous Solomon and his attending army, is that the queen and her followers worship the sun because Satan (shaytan) has deceived them by hiding knowledge of Allah from them (Qurʾan 27:24–25). The commentators explain that the reason for the queen’s wrong-headed faith was that once when she asked her advisers what her forefathers worshiped, she was told, “They worshiped the Lord of Heaven.” Not being able to see the deity, she decided to bow to the sun, for in her eyes nothing was more powerful than its light.Footnote 25 As her people’s sovereign, she then “obligated her people to do likewise” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 525).

The hoopoe ends its report by praising Allah, “Lord of the Mighty Throne,” using the same term, ʿarsh-i ʿazim, used to describe God’s celestial throne in the Qurʾan (27:26). The news discombobulates the King. Had God not placed the wind at his service to inform him of all that happened in his kingdom and beyond? Not exactly! God in “His” infinite wisdom wished to humble Solomon occasionally and to let him know that there were limits to his power (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 228, n. 12; Sattari Reference Sattari2002, 84). The news of a ruling queen was of a different order. There were plenty of queen consorts in Solomon’s extraordinary harem, including the Pharaoh’s daughter. But a sun-worshiping sovereign queen was well outside of the patriarchal order and beyond the limits of his imagination. Incredulous, Solomon decided to determine the truth of the bird’s eyewitness account for himself. He gave the hoopoe a letter, instructing it to take it to the queen and wait to see what answer she gave.Footnote 26 The message to the queen was ominous: “Be ye not arrogant against me, but come to me in submission” (Qurʾan 27:27–31).

The queen became alarmed. Was this yet another imposter king? Had she not established her legitimate authority by beheading one already? But then she reckoned that “Any ruler who uses birds as his emissaries is indeed a great leader” and must be “a mightier sovereign than herself” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 526; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 192). The queen knew better than to mock or ignore a powerful adversary’s threat. Once again, she planned her strategy carefully.

Sitting on her royal throne, Thaʿlabi imagines, the queen “typically” assembled her advisers and spoke to them “from behind a veil.” But then, Thaʿlabi stresses, “when an affair distressed her, she unveiled her face” (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 526). Unveiled and in control, she told her advisers about the threatening letter she had received from Solomon and asked for their advice (Qurʾan 27:29–30). Acknowledging their leader’s authority, they declared their willingness to fight on her behalf: “We possess force and we possess great might. The affair rests with you; we follow your command” (Qurʾan 27:32–33). Mindful of the King’s serious challenge to her sovereignty and her community, however, the politically savvy queen cautioned her counselors, “Kings, when they enter a city, disorder it and make the mighty ones of its inhabitants abased” – and the All-Knowing Almighty confirms, “That they will do” (Qurʾan 27:34). The Queen of Sheba’s act of consultation, however, gives Thaʿlabi pause. He dismisses the queen’s advisors as submissive men, and the queen as a cunning woman. Granted, he observes, the queen was an intelligent and clever woman, but she “dominated the chief men of her people” and “exercised control and managed them at will” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 527). Thaʿlabi’s sexism notwithstanding, the Queen of Sheba decided astutely to send Solomon splendid gifts (Qurʾan 27:35), in hopes that the exchanging of gifts would serve as a prelude to ceasing or avoiding hostilities.

Gift Exchange and Peace-Making

What kind of gifts did the Queen of Sheba send Solomon? The Qurʾan is silent on that. But medieval storytellers tell us that in addition to camel-loads of silver, gold, spices, and frankincense, the queen’s gifts included riddles. The commentators tell us that sending gifts, engaging the king in witty exchanges, and solving riddles were not only a means by which the queen sought to avoid conflict. Having heard of Solomon’s boundless intelligence,Footnote 27 the Queen of Sheba – no less intelligent herself – decided to test him and in the process determine whether he was a king or a prophet. The queen reasoned that if he accepted her gifts and looked at her emissaries with a “look of wrath” it would mean that he was only a king and no mightier than she – that his intention was political and that he desired to depose her and confiscate her mighty throne. But if he refused her gifts and appeared to be an “affable, kindly man,” that would be a sign that he was a prophet of God and would not be satisfied until she submitted to him and followed his religion (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 528–529; Stowasser Reference Stowasser1994, 64–65).

She arranged for some five hundred adolescent boys to be dressed as girls and an equal number of adolescent girls to be dressed as boys, and asked Solomon to “distinguish the maidservants from the menservants” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 528). The King was able to identify the sex of the cross-dressed crowd only when Angel Gabriel and his hoopoe spy came to his aid – the hoopoe had watched the queen’s preparations from the sky and informed the king accordingly (Tabari 1994, 173; Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 529). The difference between the sexes, we are told, could be seen in the “natural” (i.e. habitual) ways young boys and girls wash their faces: “A girl would take water from the vessels with one of her hands, put it in the other, and then splash her face with it, while a boy would take it from the vessel with both his hands and splash his face with it” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 530; Tabari 1994, 174).Footnote 28

Solomon rejected the queen’s gifts, professing that what God had given him far surpassed what God had given her (Qurʾan 27: 36). He then accused the queen and her emissaries of being “a vainglorious people, trying to outdo each other in things of this world” because they did “not know anything else” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 530) – presumably meaning that they knew nothing but power and greed. Solomon sent her emissaries back with another threatening message, warning of his imminent attack and the expulsion of the queen and her people from their land, “abased and utterly humbled” (Qurʾan 27:37).

Once again the commentators moved to soften the harsh language of the quick-tempered patriarch. Thaʿlabi has him dabbing his letter with musk and sealing it with the impression of his famous signet ring (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 526), “the ring from which he derived so much of his power” (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 52). In the Jewish Targum Sheni, Solomon starts his letter with: “From me, Solomon the King, who sends greetings. Peace unto you and your nobles, Queen of Sheba! No doubt you are aware that the Lord of the Universe has made me king of the beasts of the field, the birds of the sky, and the demons, spirits, and Liliths. All the kings of the East and West, and the North and South, come to me and pay homage.” He then goes on to politely but firmly demand that she come to him, pay homage, and submit (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 166). Certain that Solomon is a prophet of God, the Queen of Sheba decided to embark on a journey to Jerusalem to meet with Solomon personally in hopes of averting the certain destruction of her community. But before leaving her homeland, Thaʿlabi tells us, the queen

[O]rders her throne to be placed in the innermost of seven rooms, arranged one within another, in the most remote of her castle. She closed the doors behind it, and set guards over it to keep it safe. She said … “Keep my royal throne secure, and do not trust it to anyone or let anyone see it until I return.”

The Queen of Sheba then embarked on her journey to Solomon’s court, accompanied by 12,000 chiefs of Yemen, under each of whom were 100,000 warriors (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 531).

In the meantime, King Solomon, who had earlier rejected the queen’s gifts and accused her of vaingloriousness, now wanted to possess her Mighty Throne – the seat of her power. The King was not wanting in mighty thrones – God had given him plenty of those.Footnote 29 It is recorded that

Solomon b. David had six hundred thrones set out. The noblest humans would come and sit near him, then the noblest jinn would come and sit near the humans. Then he would call the birds, who would shade them, then he would call the wind, which would carry them.

Still, Solomon coveted the queen’s Mighty Throne, given to her by none other than the Almighty. But why would he want to seize her throne? Thaʿlabi argues that when Solomon saw from afar the cloud of dust stirred up by the queen’s mighty army marching toward his kingdom, he moved swiftly to appropriate the queen’s throne (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 531). Did the King feel fearful, envious, or threatened by the Queen’s formidable army? Relying on his vast army of supernatural beings, the warrior king asked his companions and minions, “Which one of you can bring me her throne before they come to me in submission?” (Qurʾan 27:38). A mighty creature from among the jinn offered to bring it to him before he could rise from his seat. “I want it faster than that,” Solomon said. (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 58). One who had the knowledge of the Book,Footnote 30 a certain Assaf Barkhia, the king’s wazir, offered to bring the queen’s throne to Solomon’s court in the blink of an eye – and so he did (Qurʾan 27:40).Footnote 31 Knowledge is indeed power,Footnote 32 but prayers also help. Assaf’s prayer was, “Our God and God of all things! One God, there is no god but You. Bring me the Throne” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 532; Tabari 1994, 174–175). The world-renowned Persian philosopher and mystic poet Maulana Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273) makes clear, however, that this feat was made possible only because of “Assaf’s breath” (dam), the power of his faith, rather than a magician’s trick (Masnavi 4, 57).

Be that as it may, Solomon thanked God for having made it possible for him to confiscate his rival’s Mighty Throne (Qurʾan 27: 40). He then instructed his minions to disguise the throne in order to “see whether she is guided,” that is, if she recognizes the “truth” (Qurʾan 27:41). Muslim scholars and sages have argued extensively over the legality of taking the queen’s throne. Clearly, they realize Solomon’s action requires explanation. Some say “It was because its description amazed him … so he wanted to see it before he saw her.” Others say it was because “he wanted to show her the omnipotence of God.” Still others say it was because he wanted to show “the greatness of his own power” and prove his prophethood (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 531; Rahnema Reference Rahnema1974, 211). But most agree “it was because Solomon knew that if she surrendered, her property [as a Muslim] would be unlawful for him [to take], and he wished to seize her throne before it was thus forbidden to him” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 531). When the queen finally came before the king, he confronted her with her confiscated throne and asked her whether she recognized it.

Had she not locked up her throne securely in the innermost secret part of her palace before leaving?

Seeing her Mighty Throne in Solomon’s possession, the queen was convinced that he was a prophet and that she was no match for him – at least not militarily. The wise queen then gave a measured response: “[It is] as though it were the very one,” adding, “We were given the knowledge beforehand and we had submitted” (Qurʾan 27: 42). With the queen at the threshold of his palace and her throne in his possession, Solomon invites the Queen of Sheba to enter, but not before subjecting her to another test.

Rites of Passage

It is related that the devils and the jinn that God had assigned to serve at Solomon’s court (Qurʾan 34:12) feared that once he saw the beautiful Queen of Sheba he would instantly fall in love with her, that they would marry and have a son, and the jinn would never be freed of their bondage to Solomon and his progeny (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 533). So, they tried to “incite him against” the queen by telling him that “there is something [wrong] with her intelligence and her feet are like the hooves of a muleFootnote 33 … and she has hairy ankles, all because her mother was a jinn” (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 534; Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 162).

Be that as it may, a highly curious Solomon set out to find out the truth of the queen’s donkey-like hairy legs for himself. Mindful of the queen’s approaching army, whose dust cloud had darkened the sky of his empire, Thaʿlabi tells us, Solomon ordered his devils and jinn to build “a palatial pavilion of glass, clear as water, and make water flow beneath it, and have fish in the water. Then he placed his throne above it, and sat upon it, and the birds, the jinn, and the human beings crowded around him” (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 534). With the stage impeccably set, Solomon invited the queen to enter his palace.

As the Queen of Sheba was about to cross the palace threshold, she perceived the entrance to the pavilion as “a spreading water” and so “uncover[ed] her legs” – lifting up her skirt – to enter, only to recognize the “water” as slabs of smooth glass. Realizing the illusion, the queen said, “God, I have wronged myself [zalamtu nafsi] and surrender [aslamtu] with Solomon to God, the Lord of all Being” (Qurʾan 27:44). Awakened to a new reality, the queen surrendered to God by accepting the new faith, and with that her story ends in the Qurʾan. But not in the imagination of biographers and storytellers.

As the Queen of Sheba lifted up her skirt to cross the watery threshold, the story continues, Solomon stared at her bare legs.Footnote 34 After all, the purpose of that architectural marvel of the water palace was, from the medieval storytellers’ point of view, to trick the Queen of Sheba into exposing her legs so that the king could see for himself whether she had donkey-like hairy legs! Lo and behold, the queen did not have the hooves of a mule, but her legs were ever so scruffy, with hair “twisted around” them. “Disgusted” by the sight, Solomon modestly averted his gaze (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 535; Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 162). King Solomon asked his supernatural minions what might be the best way to remove the unsightly hair. He called on them, saying, “How ugly this is! What can remove it?” (Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 163). They suggested as mundane a solution as using a razor. But the king would not hear of it – castration anxiety? (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 201; Hallpike Reference Hallpike1969, 257). The king then turned to the jinn, but they feigned ignorance. At last Solomon sought help from his demons and devils, the ʿafarit – his ever-ready enablers. The demons finally found a solution, making a depilatory paste to remove the hair and leave the queen’s skin smooth and silky (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 536; Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 201).Footnote 35

Muslim biographers have described the elaborate process of depilating the queen’s hairy legs as a prelude to sexuality and cohabitation.Footnote 36 As a hairy queen, her gender is ambiguous. She is liminal in the sense that she is neither fully human nor fully jinn, neither truly feminine nor wholly masculine. She is an ambiguous creature with no recognizable place in the “natural” gender hierarchy of the patriarchal social order. Depilation aimed to “feminize” the queen by getting rid of her unsightly masculine leg hair, disabling her supernatural power (inherited from her jinn mother), and to “humanize” her by retrofitting her to the patriarchal gender hierarchy. The Queen of Sheba is silenced, her body is appropriated, and her throne is confiscated. She is no longer a sovereign queen, but a queen consort, a concubine – a bilqis; no longer a political agent but a subject.

With the queen’s surrender to Solomon’s faith, and her hairy legs depilated, did the king cease hostilities, marry her, and send her to his humungous harem? We read none of that in the Qurʾan. God’s concern is not with the queen’s marital status. Nor does God arrange for the fabulous pair to get married and live happily ever after. Indeed, the queen’s gender is immaterial to her leadership and governance. It is, rather, her faith that is at the center of the Quranic revelations. But in its medieval reconstructions, it is gender politics that takes the center stage. The struggle for war and peace and the recognition of the true faith was turned into the battle of the sexes, leading to the silencing of the queen and the objectification of her persona. Mystified by an inconclusive ending to the encounter between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba – be it romantic, legal, or both, in the Qurʾan – storytellers and biographers have speculated at length as to what may have – could or should have – happened in the aftermath of this high-level gender encounter. Some have contended that Solomon did fall in love with Bilqis, married the queen, and gifted Baʿalbak in greater Syria as her dowry (Mottahedeh Reference Mottahedeh, Cook, Haider, Rabb and Sayeed2013, 249). Subsequently, he established her as a ruler over her dominion and had the jinn build her three more palaces to expand her realm (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 201). Others have maintained that Solomon married the Queen of Sheba, but sent her back to Yemen – where she continued to rule over her people – and visited her every few months (Lassner Reference Lassner1993, 62). The intermittent nature of his nuptial visitations has given some biographers the impression that Solomon might have taken the queen as his concubine, as her name Bilqis (from the Hebrew pilegesh, meaning “concubine,” as noted above) may suggest. A different view holds that Solomon, still disgusted by – or fearful of – the sight of the queen’s “masculine” hairy legs, had this “haughty” woman humbled by having her marry a man from among his companions, despite her objection to marrying when she already had dominion over her own people (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 535–536; Tabari Reference Tabari and Brinner1991, 164). Lassner muses that the queen’s biggest disappointment must have been her ultimate rejection by Solomon: “This haughty woman who had never been touched by a ‘blade’ and trained great men as if they were wild stallions to be broken, will be rejected outright by the great stallion of them all” (Reference Lassner1993, 85–86).

From then on, Thaʿlabi tells us, love and marriage were no longer possible between humans and the jinn, and humans could no longer see the jinn, though the jinn could see them (Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 523). The renowned scholar of mystical Islam, Annemarie Schimmel, wonders why “love” is missing in this story, and why the meeting between the “miracle working Solomon” and the “Yemenite queen has not been transformed into a romantic epic as have so many other traditions in Persia. This Quranic story,” she reflects, “would have been the fitting basis of a wonderful allegory about the spiritual power of the divinely inspired ruler and the love of the unbelieving woman who finds her way to the true faith through the guidance of his words” (Reference Schimmel1997, 59–60). But could love flourish in a relationship based on inequality, trickery, domination, and control?

Solomon and Sheba both show intense curiosity, and a desire to know the other. But the paths they take to unite with the other lead them to different results. Having heard of the wisdom and justice of the prophet-king Solomon, the queen embarks on a journey of discovery, hoping to unite “with one who has wisdom” through negotiating and building bridges, making peace, and possibly finding love. King Solomon too seeks unity with the other, but he does so through appropriation and coercion. In the Sufi literature one’s soul is the abode of both ʿaql (wisdom) and nafs (desire, the base instincts). Where ʿaql is equated with masculinity, nafs is associated with the feminine and thus subordinate to ʿaql, the male intellect and reason (Schimmel 2003, 70). The wise Queen of Sheba’s leadership provides a counter-narrative to this dominant patriarchal discourse that is firmly enshrined in the thought structure of medieval sages and biographers. Love of her people motivates the queen to act rationally, wisely, and prudently, as a good leader should.

Whether he treated the Queen of Sheba as a concubine or a wife, King Solomon did not usher her into his own giant harem, and Muslim and Jewish biographers have written copiously about this. Or, might it have been that the queen did not wish to part company with her people, marry Solomon, and join his multiracial, multifaith harem? Biographers have paid little or no attention to the queen’s wishes and agency. It is not her brilliant diplomacy and successful peace-making initiatives to avert a certain war that is utmost in the minds of patriarchal exegetes, but rather the control of this “haughty” – read autonomous – woman’s body, and restriction of her mobility and sexuality through marriage. The water rite of passage is not seen as a transition to a new vision of reality – a new faith – but as the ruse of a lustful king who tricks the queen into lifting up her skirt so that he can see her blemished hairy legs.

Did the queen return to Yemen, having averted war and saved her paradisaical oasis? Would her people hail her as their savior once again, and receive her as their undisputed leader? Would they follow their queen and convert to the new faith? Would God lavish even more favors on her now that she was a believer? We do not know the answer to these questions, but ignorance has not prevented many storytellers and chroniclers over the centuries and across many cultural traditions from portraying politically active women as “Lilith,” “haughty,” “hairy legged,” “wicked,” “jinn,” and “crooked” (President Donald Trump continues to refer to his defeated opponent as “crooked” Hillary). At best, such women are humbled through marriage. At the center of the social drama of the king and queen’s encounter, as reconstructed by medieval biographers, lies the sexual politics of domination and submission, mediated through the authoritarian – lustful? – gaze and facilitated by removing problematic hair (i.e. a sign of ambiguous gender). Having submitted under Solomon’s threat, the queen’s high‐level encounter with him ended in an uneasy truce that left the status of the queen and the nature of her relationship to the king unknowable, and thus subject to patriarchal wishful thinking and fanciful interpretations.

In historicizing the Queen of Sheba, she is systematically stripped of her individuality, autonomy, and authority; she is transformed into an imaginary consort of the king – but with some qualifications and ambivalence. While the patriarchal imagination celebrates the queen’s political defeat and sexual submission, it is woefully deficient in judging her spiritual awakening or her independent acceptance of “the true faith (Islam)” (Wadud Reference Wadud1999: 40–42; see also Booth Reference Booth2015, 140–141).

The Qurʾan and the Hadith: Women, Authority, Sovereignty

In the preceding pages I have given my interpretation of the Quranic story of the Queen of Sheba interwoven with multiple – and often colorful – reconstructions by medieval Muslim exegetes and biographers. As a divinely chosen sovereign, the Queen of Sheba was the temporal and spiritual leader of her people. She commanded authority and respect among her advisers and military leaders, who were willing to go to war for her. Although alarmed, the Queen of Sheba was not cowed by the threat of war, but nor was she willing to drag her people into a destructive conflict. In taking this stand, she can be viewed as the quintessential model of a caring and wise leader. Indeed, she was mindful that “Kings, when they enter a city, disorder it and make the mighty ones of its inhabitants abased” (Qurʾan 27:34). The queen pursued peace with the king, who was a much stronger adversary. She thus saved the lives of her people and prevented the destruction of her paradisaical community. As she was “historicized” in the patriarchal imagination of medieval biographers and exegetes, however, she was demonized as half-jinn, her sovereignty was delegitimized, her authority was usurped, and her autonomy was brought under the control of a husband.

In the Quranic revelations, neither is she the daughter of a jinn princess – and hence, not an imposter or a usurper ruler – nor is her sovereignty rejected by the rank and file. Besides, God gave the sun-worshiping queen a Mighty Throne that so powerfully confounded medieval Muslim sensibilities. The biographers conveniently overlooked the fact that the Qurʾan draws parallels between the queen’s Mighty Throne and God’s Celestial Throne, identifying them in both instances as ʿarsh-i ʿazim. As God the “All-merciful sits upon the Throne, and His Throne embraces the heavens and the earth,” in the mystic philosopher Ibn ʿArabi’s contemplation, he has “mercy upon all things (Chittick 1995)”Footnote 37 Graced with the “divine love,” Ibn ʿArabi stated, the Queen of Sheba exhibited her love and compassion for her followers; negotiated peace and saved her people from certain destruction. But the sages’ patriarchal predispositions precluded them from appreciating the queen’s sagacious agency – be it in the political or the spiritual domain.

In the storytellers’ interpretations, the story ends with King Solomon confiscating the Queen of Sheba’s Mighty Throne, sending her back to Yemen with a new husband, and installing the queen’s husband as the new ruler and king of Yemen. Solomon then appoints a jinn to serve her husband and to keep a watchful eye on the Queen of Sheba (Thaʿlabi Reference Thaʿlabi and Brinner2002, 536). Clearly, the new king of Yemen, the queen’s husband, needed supernatural help – as did King Solomon himself – to conduct affairs of state and to keep the queen away from the public and from politics, all but forgetting that – or maybe because – the queen’s mother was a powerful princess jinn. Even if we were to grant the medieval biographers’ wish to banish the Queen of Sheba to the private domain, deny her power in the public domain, and keep her under the watchful eye of her husband – and the jinn? – the queen would not disappear, nor her power instantly evaporate. Even pushed behind the walls of her palace and forced into silence, the Queen of Sheba refused to be forgotten and stayed alive in popular oral culture, reemerging as Sayyida Hurra Queen Arwa, better known as “the little queen of Sheba” in eleventh-century Yemen (Chapter 3) and as Razia Sultan, also known as Bilqis-i Jihan, “Queen of the World,” in thirteenth-century India (Chapter 4).

At the center of the Quranic story is a drama of faith and paganism, a story in which neither the queen’s autonomy nor her authority is at issue. But in its medieval reconstructions and interpretations, the central issue of faith becomes secondary to political rivalry and the need for patriarchal conquest and domination. The encounter between the king and queen is interpreted as a drama of sexual politics, of domination and submission, of a zero-sum leadership competition. While the queen’s political authority threatened the king, her hairy legs (implying masculine authority) disgusted him, and her supernatural power (her presumed maternal jinn ancestry) frightened him even more. He had to get rid of them all: the queen had to be dethroned, her sovereignty usurped, and her authority transferred to a husband of sorts – patriarchal domination consolidated.

Although by the Middle Ages the story of the Queen of Sheba had been incorporated into a rigid patriarchal sensibility and biases, and theoretically women were banished from the public domain, throughout Islamic history, many women wielded power behind the throne and several others have actually come to power and ruled as sultans, queens, prime ministers, and presidents, as I will discuss in the following chapters. The question is when and how the alleged Prophetic hadith “Never will succeed such a nation as makes a woman their ruler” emerged, and for whom and under what circumstances it was invoked. How did this hadith become so prominent that in 1988 it formed the basis for a legal suit brought against Benazir Bhutto, the democratically elected Prime Minister of Pakistan; and in 1999 derailed the presidency of Megawati Sukarnoputri of Indonesia? How to explain the difference between these two supreme sources of authority, the Quranic revelations regarding the sovereignty of the Queen of Sheba and the alleged Prophetic hadith warning against women’s political leadership? I suggest we journey back in historical time to explore the sociopolitical dynamics of the rapidly growing Muslim community and revisit the role Aisha, Mother of the Faithful and beloved wife of Prophet Muhammad, played as a military leader in the battle of succession, popularly known as the Battle of the Camel.