1. Introduction

Studies on frequency of input as a relevant factor in L2Footnote 1 acquisition go back to the early phases of systematic L2 research. This line of enquiry faded into the background, however, with the emergence of universalism and its domination of the field (Schachter, Reference Schachter1988; Menn & Bastiaanse, Reference Menn and Bastiaanse2016). It has, however, come into focus as an explanatory factor, motivated by theories of usage-based learning as well as probabilistic approaches in the context of machine learning.

The aim of the present study is to challenge the role of frequency as the major factor in L2 acquisition on the way to acquiring full competence – full competence which includes comprehension and creative language use. “It’s all counting” (Ellis, Reference Ellis2002, p. 148) or “language is a statistical accumulation of experiences” (Siyanova-Chanturia & Spina, Reference Siyanova-Chanturia and Spina2015, p. 553) – these are claims which will come under scrutiny. If ‘experience’ is viewed as the basis for all kinds of learning, what does ‘experience’ entail in order to be transformed into the relevant knowledge structures and put into practice? There has been a long-standing discussion on the different cognitive processes which influence and determine language acquisition: attention, awareness, conscious detection, storage in memory – theoretical constructs which expand on what constitutes experience. Robinson (Reference Robinson1995) provides a still valid, comprehensive overview of theories that attempt to model the interaction between these different components of the relevant cognitive capacities. He concludes that “the nature of the interaction between cognitive resources during information processing and language learning is little understood” (1995, p. 318). Twenty-five years and countless studies later we can draw on a wide range of empirical details concerning L2 acquisitional processes. However, our understanding of L2 acquisition is still far from complete. One of the problems lies in the often reductionist approach in L2 acquisition research. As will be discussed below, recent studies on the role of frequency in language acquisition focus on acquisition as the storage of linguistic material and production in scripted contexts. Little attention is placed on L2 competence in relation to creative language use. A word recognition test or a frequency judgment test might show that learners have acquired lexical items, idiomatic expressions, or knowledge on collocations of certain items. When it comes to the underlying factors which are highly language-specific in actual language use, however, L2 speakers may fail to follow the specific sets of principles that native speakers apply when linking linguistic categories and conceptual representation. There are underlying components of language competence that cannot be transmitted via frequent experience in the perception of forms because they are covert. This holds for form–function relations that encompass larger conceptual units such as event frames or object schemata. Robinson pointed to this domain as follows: “Further, when tasks require predominantly conceptually-driven processing, the availability of knowledge schemas to organise perception and to direct attention to relevant aspects of the stimulus domain should also be important. The extent to which preexisting representations are available will determine the efficiency of attentional allocation” (1995, p. 320). We will elaborate on this claim in the present study by looking into the role of pre-existing representations as internal pull-factors in relation to external push-factors determined by properties of the input. On these grounds, frequency of ‘experience’ will thus be placed in the larger context of theories on language and cognitive processing.

The idea that external and internal factors have to come together in L2 acquisition is certainly not new. However, current models set complex internal factors largely aside by claiming that language learning is exemplar-based at all levels (Ellis, Reference Ellis2002, p. 166). Whilst noting that L2 acquisition is filtered through the lens of the L1, Wulff and Ellis (Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018, p. 50) state in conclusion that “second language learners employ the same statistical learning mechanisms that they employed when they acquired their first language”. On the basis of an empirical study on a central domain of human cognition – spatial categories – it can be shown that there is a crucial difference between the two types of acquisition given the fact that conceptual frames which have become deeply anchored in the course of L1 acquisition may override frequency effects.

2. State of the art

2.1. processes at the base of language acquisition

Usage-based theories hold that language learning, both in first and second language, relies on a range of implicit cognitive mechanisms such as association, sensitivity to frequency of occurrence and to strings of occurrences (chunking), as well as the extraction of statistical regularities and inductive generalisation of collocational dependencies. The assumption is that speakers as ‘intuitive statisticians’ are highly sensitive to frequency in the use of linguistic expressions. In the case of language acquisition, frequency of occurrence is viewed as a major determinant (Ellis, Reference Ellis, Doughty and Long2003; overview in Kartal & Sarigul, Reference Kartal and Sarigul2017). According to this point of view, each repetition will increase the strength of the connections of relevant features, reinforce representation in memory and thus automatic retrieval. The resulting knowledge is stored in a mental lexicon “in which abstract grammatical patterns and lexical instantiations of those patterns are jointly included” (Tummers, Heylen, & Geearts, Reference Tummers, Heylen and Geearts2005, pp. 228–229). This idea is elaborated further in the theoretical framework of Construction Grammar (e.g., Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006; Ellis, Reference Ellis2013). “Research in psycholinguistics demonstrates that generally, the more frequently a construction (or combination of constructions) is experienced, the earlier it is acquired and the more fluently it is processed” (Wulff & Ellis, Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018, p. 40).Footnote 2

In contrast to earlier studies on frequency effects in L2 acquisition in which individual morphemes and lexical items were under focus (Larsen-Freeman, Reference Larsen-Freeman1976; for reviews see Gass & Mackey, Reference Gass and Mackey2002; Larsen-Freeman, Reference Larsen-Freeman2002), the effect of frequency of experience on acquisition has been extended to combinations of linguistic units. Learners are not only sensitive to the frequency with which expressions occur but also to their distribution. Spoken language is constituted by a large number of highly frequent combinations of specific words, up to 50% according to an estimation by Erman and Warren (Reference Erman and Warren2000). These combinations range from collocations over conventional expressions, fixed expressions, and idioms to proverbs. Fixed or prefabricated expressions of this kind have motivated an important area in L1 and L2 research in investigating how they are processed and represented in the brain (cf. Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Simpson-Vlach, Römer, Brook, Donnell, Wulff, Granger, Gilquin and Meunier2015; Siyanova-Chanturia & Pellicer-Sanchez, Reference Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-Sanchez2019, for reviews). Given the diversity of the linguistic structures investigated, the following overview of the studies will be limited to those on the expression of multiword expressions.

2.2. overview of studies on the role of frequency in multiword processing

The general assumption underlying frequency effects in psycholinguistic research is that there is a relationship between the frequency of items and constructions and speed in reaction time, as well as accuracy in relation to the use of these linguistic forms. Investigations focus on the implicit cognitive mechanisms in comprehension as they unfold in real time. Results for readings times show frequency effects (McDonald & Shillcock, Reference McDonald and Shillcock2003; Ellis, Frey & Jalkanen, Reference Ellis, Frey, Jalkanen, Römer and Schulze2009). Studies on memory capacity revealed that performance varied in accordance with the factor frequency (Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Derwing, Libben and Westbury2011). Another line of research focused on grammaticality judgement tasks (Arnon & Snider, Reference Arnon and Snider2010). Subjects processed frequent combinations faster than less frequent ones. In the same vein, eye-movement studies showed that the fixation time on each word in reading is a function of its frequency and of the forward transitional probability (McDonald & Shillcock, Reference McDonald and Shillcock2003). These and similar L1 studies that test a range of processing mechanisms offered multifaceted evidence that speakers are sensitive to the frequency with which constructions/collocations occur: frequent collocations are perceived, recognised, retrieved, and recalled faster, thus reflecting their level of entrenchment and pointing to a holistic representation in the mental lexicon (cf. overview in Ellis, Reference Ellis2002; Gries & Divjak, Reference Gries and Divjak2012; for discussion Bley-Vroman, Reference Bley-Vroman2002). The same standard paradigms are used to systematically study frequency effects in L2 speakers and in comparisons of native and non-native speakers.

2.3. frequency effects: l2 speakers

L2 studies relevant in the given context investigated the extent to which second language speakers show the same sensitivity to frequency of constructions/collocations as native speakers of their target language (TL). Jiang and Nekrasova (Reference Jiang and Nekrasova2007) studied frequency effects in a timed judgement task. L2 English and English L1 speakers both responded faster to frequent in contrast to non-frequent collocations which were matched for length (to tell the truth vs. to tell the price). A study conducted by Ellis, Simpson-Vlach, and Maynard (Reference Ellis, Simpson-Vlach and Maynard2008) tested how frequency, as well as degree of cohesiveness, affect accuracy and fluency when processing sequences of formulaic academic speech and writing. Evidence from the different experiments, which tested recognition and production, converged in showing that native as well as non-native speakers process frequent formulas faster. However, non-native speakers were predominantly influenced by frequency effects at the item level, whereas native speakers were predominantly affected by association-strength effects. In a follow-up study, Simpson-Vlach and Ellis (Reference Simpson-Vlach and Ellis2010) further investigated the role of frequency of collocations on a large range of processing mechanisms including reading time, voice onset time, articulation time, priming procedures, and plausibility of occurrence in the real world. Results confirmed previous findings showing that frequent formulas are processed faster in all tests. Arnon and Snider (Reference Arnon and Snider2010) analysed the impact of frequency on combinations which differed along a continuous frequency scale. Using a phrasal decision task on four-word combinations, don’t have to worry vs. don’t have to wait, regression analysis showed that response times were inter-related with the frequency of the strings, thus supporting the assumption of learners’ sensitivity to the frequency of collocations. Vilkaitė and Schmitt (Reference Vilkaitė and Schmitt2017) compared reading times of adjacent vs. non-adjacent collocations vs. controls obtained from L2 speakers of English with those obtained from L1 speakers (such as provide (some of the) information vs. compare (some of the) information) using eye-tracking. Adjacent collocations were read faster in both the L1 and L2 groups, but a higher speed in non-adjacent collocation processing was manifest in the L1 group only.

Studies testing sensitivity to frequency of collocations in relation to levels of competence in L2 are scarce. Siyanova-Chanturia, Conklin, and van Heuven (Reference Siyanova-Chanturia, Conklin and van Heuven2011) used an eye-tracking paradigm to examine the comprehension of fixed phrasal combinations, e.g., time and money vs. their reversed forms money and time. They found frequency effects both in L1 and in highly competent L2 speakers, but not in speakers with a lower proficiency. Hernández, Costa, and Arnon (Reference Hernández, Costa and Arnon2016) tested the impact of competence in the L2 (upper intermediate vs. lower advanced) and type of exposure (immersion vs. classroom) on frequency effects. Based on the methodology and material used in Arnon and Snider (Reference Arnon and Snider2010), they found that both native and non-native speakers, irrespective of level and exposure, manifested equal sensitivity to the frequency of multiword units. L1 influence on processing idioms and collocations in the L2 was recently investigated by Conklin and Carroll (Reference Conklin, Carroll, Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-Sanchez2018). According to the authors, idioms and collocations of the L1s are activated and influence processing of their L2 counterparts on the basis of relations involving form and meaning. When meaning and form are shared, processing is facilitated. However, if form but not meaning, or the reverse, do not overlap, then processing is more difficult.

2.4. discussion of previous studies

In a review paper, Ellis (Reference Ellis2002) summarises findings on L2 acquisition at different levels of linguistic complexity with the claim “it is all counting” (Reference Ellis2002, p. 148). However, we hold that there are a number of major limitations on the validity of such a generalised statement which are rooted in our understanding of what it means to acquire a language and what language competence actually encompasses. As the overview shows, the studies on frequency effects are limited with regard to both the type of linguistic material and levels of language processing, in that focus is placed on idiomatic expressions and highly frequent collocationsFootnote 3 in scripted contexts. These components of linguistic knowledge were tested in comprehension, accessibility, and adequacy/grammaticality judgements. In most of these formats, however, L2 speakers do not have to activate conceptual representations in response to a novel stimulus and link these with their available L2 lexical and grammatical repertoire. It thus remains untested in how far speakers are actually able to activate their L2 knowledge in a way that meets patterns of cognitive construal in the target language. There is more to language competence than an inventory of lexical items, their collocations, and constructions. This can be readily illustrated by looking at two of the most frequent words in the English language: the articles the and a. These forms are certainly acquired from very early on in L2 acquisition. However, the principles which govern their use in context and which form part of the linguistic knowledge of a native speaker are extremely difficult to uncover and acquire (e.g., Jarvis, Reference Jarvis2002). Components of language competence of this kind can only be investigated with studies on creative language use. Although this is one of the central tenets of usage-based approaches (cf. the discussion in Tyler, Reference Tyler2010), empirical research on contextually adequate use of (complex) linguistic forms is still rare.

3. The present approach

3.1. overview

In L2 acquisition new TL forms meet consolidated conceptual structures which in terms of abstract categorical knowledge will include object categories as well as event or situation frames, or schemata (cf. Fillmore, Reference Fillmore and Zambolli1977; Langacker, Reference Langacker1987; overview in Croft & Cruse, Reference Croft and Cruse2004). The conceptual framing acquired in the course of L1 acquisition which manifests in language-specific patterns of event construal may impede acquisition and use of frequent and easily processed strings of words in the L2 (cf. the discussion on conceptual transfer Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2011). This can be attributed to the fact that the processes are subject to a push-and-pull mechanism based on both external and internal factors: in order to achieve L2 competence, which includes cognitive framing, the two forces have to work jointly in opening the gateway for intake. The key concept in this process is selective attention (cf. ‘windowing of attention’, Talmy, Reference Talmy, Shibatani and Thompson1994). In order to process information and to store it in long-term memory it has to be attended to consciously or unconsciously.

There are two types of factors that function as a filter on processes involving selective attention and its allocation in acquisition, as well as in creative language use: internal factors, based on existing conceptual representations, function as conceptual preconditions which lead to the search for specific expressive devices for use in language production. Communicative requirements, framed in specific conceptual structures, guide attention and thereby block or promote the reception and storage of new forms. Given the fact that event frames and object schemata take shape in the course of L1 acquisition, this leads to language-specific moulding of conceptual content. This will thus accord salience to specific features while defocusing others. Conceptual framing and pre-existing representations constitute a driving force in the selection and use of linguistic material.

External factors, as manifested in the input, can be attributed to different features, such as the frequency with which an element occurs, phonological markedness, and syntactic markedness, but also communicative relevance as well as contingency in form–function relations (cf. Wulff & Ellis, Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018). Salience in the input will trigger attention (cf. the concept of ‘noticing’ in Robinson Reference Robinson1995, p. 318) as a precondition for perception, followed by intake and finally storage in memory. However, as we will show in the present study on the expression of motion events even very advanced L2 speakers may not use forms which are highly frequent, and which are often the only option in the TL to describe a given situation. This phenomenon calls the determining role of external factors in a strict sense into question. The present study will investigate the impact of conceptual framing in its role as a hurdle for native-like L2 use. Our approach focuses on the domain of motion events which provides a window on the range of relevant conceptual interdependencies.

3.2. Theoretical and empirical background

The conceptualization and description of motion events has been studied extensively over decades with a clear consensus across different theoretical camps that languages differ in the way in which motion events are represented. Motion events are conceptual units which result from processes of input segmentation and information selection that operate on the continuous stream of perception (Zacks & Tversky, Reference Zacks and Tversky2001; Gerwien & Stutterheim, Reference Gerwien and Stutterheim2018).

Talmy (Reference Talmy2000) laid the groundwork in capturing relevant features in a typology of spatial semantics. Numerous empirical studies based on this typology show how speakers of different languages follow specific principles in framing motion events (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004). If a speaker follows a verb-framed pattern, as in French for example, information will be selected on the figure in motion with respect to its orientation and a potential goal, as in the utterance une femme se dirige vers une église ‘a woman directs herself towards a church’. Speakers of a satellite-framed language, such as German, select information on the figure which relates to manner of motion, with information on contours of the ground traversed and a potential goal, leading to utterances such as eine Frau läuft eine Straße entlang zu einer Kirche ‘a woman walks along a street to a church’. The cross-linguistic comparisons are clear: speakers of different languages select different components of the situation for verbalization.

The research question that followed from these studies addressed the relationship between linguistically coded categories and cognitive processes. The theory formulated as thinking for speaking (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Gumperz and Levinson1996) holds that spatial conceptualisation, based on the means used to encode spatial relations between entities, is tuned to the linguistic system used in encoding. However, it is left open as to whether there is an a-modal, or possibly universal underlying cognitive structure in the representation of motion events. Experimental research then set out to tackle this question based on studies of non-verbal cognitive processing of motion events (memory performance, non-verbal segmentation tasks, visual attention, EEG categorization; cf. Flecken, Stutterheim, & Carroll, Reference Flecken, Stutterheim and Carroll2014; Flecken et al., Reference Flecken, Athanasopoulos, Kuipers and Thierry2015a; Gerwien & Stutterheim, Reference Gerwien and Stutterheim2018; Stutterheim et al., Reference Stutterheim, Andermann, Carroll, Flecken and Schmiedtová2012). The findings present evidence of processes that are language-specific. They allow for the conclusion that event framing, as shaped by a specific language, leads to deeply entrenched patterns which function at a high level of abstraction and allow highly automatized and rapid cognitive functioning in order to meet the requirements of communication and interaction within a complex reality.

The line of argumentation in the current study is based on a wide range of cross-linguistic studies on the verbalisation of motion events (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Weimar, Flecken, Lambert and Stutterheim2012; Stutterheim et al., Reference Stutterheim, Andermann, Carroll, Flecken and Schmiedtová2012, Flecken et al., Reference Flecken, Carroll, Weimar and Stutterheim2015b; Stutterheim et al., Reference Stutterheim, Gerwien, Bouhaous, Carroll and Lambert2020). For example, in a study contrasting German and French (Gerwien & Stutterheim, Reference Gerwien and Stutterheim2018), participants were asked to describe situations presented in video clips. The results show significant differences between the two groups, reflecting language-specific contrasts in spatial cognition as the critical factor: French speakers, when expressing direction, proceed on the basis of spatial concepts based on the figure (direction, orientation) in motion event construal. Significantly, these concepts are expressed in verbs, e.g., avancer ‘to advance’, se diriger ‘to direct oneself’ (Carroll, Reference Carroll, Habel and Stutterheim2000). If there is no evidence on the orientation of the figure or the direction taken, French speakers resort to a different pattern in conceptualization and view a situation of this type as ‘frozen motion’. This encompasses manner of motion in the verb combined with forms which encode the location of the figure only (to walk on a road). In the following the term stationary motion will be used, borrowed from Talmy (Reference Talmy2000). In contrast to French, speakers of German generally draw on ground-based properties in the formation of an event unitFootnote 4 (cf. Pourcel & Kopecka, Reference Pourcel and Kopecka2005; Berthele, Reference Berthele, Goschler and Stefanowitsch2013; Durst-Anderson, Smith, & Nedergaard Thomsen, Reference Durst-Anderson, Smith, Nedergaard Thomsen, Paradis, Hudson and Magnusson2013).

Due to extensive linguistic input in the course of L1 acquisition, language-specific conceptualisation patterns emerge and are stored in long-term memory, represented as event frames in the case of motion events. The frames form clusters of abstract concepts, whereby the basis for selection is anchored in the relevant language-specific constraints. Activation of the frames entails selective attention to different aspects in the flow of information as well as implicational relations between the relevant components. Automatic cognitive functioning draws on these frames. An L2 learner meets the new language equipped with deeply entrenched knowledge structures.

4. Empirical study

In order to address our guiding question concerning the role of frequency for L2 acquisition, we designed an empirical study in which native speakers and advanced L2 speakers verbalised motion events spontaneously. We argue that the responses provided by the subjects form a small-scale, but highly reliable, corpus which indicates specifically and unambiguously the frequency of use of specific lexical items and grammatical structures, as well as activated event frames in the domain of motion event encoding. By creating a corpus in this way, we ensure that the items being counted for comparing frequencies between groups relate to identical situations and tasks (unscripted verbalisations). We consider this to be a valid alternative approach to retrieving frequencies of occurrence from large, but ‘messy’ corpora, i.e., where context and actual reading cannot be controlled for. The analysis of the frequency of occurrence of lexical items, structures, and frames targets two more specific questions: (a) How much do very advanced speakers of an L2 use the most frequent forms used by native speakers when expressing information on motion events? (b) If L2 speakers use forms which are frequent in the TL do they use the forms in correspondence with patterns of event construal in the target language? We are interested in the factors that determine creative language use in L2s, adding to earlier studies on frequency effects by looking into unscripted language production. The analyses are therefore based on data from speakers of different languages who were asked to carry out the same verbal task.Footnote 5 Given our findings in previous studies (cf. Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Weimar, Flecken, Lambert and Stutterheim2012; Flecken et al., Reference Flecken, Carroll, Weimar and Stutterheim2015b; Gerwien & Stutterheim, Reference Gerwien and Stutterheim2018; Stutterheim et al., Reference Stutterheim, Gerwien, Bouhaous, Carroll and Lambert2020) the following three languages were selected: French, German, and English, with two groups of learner-language speakers with French as L1 and German and English as L2s.

4.1. selection of languages

The languages selected in this study represent different patterns in event construal in spatial-typological terms: in French, spatially relevant features of the figure in motion form the core of the concepts used to describe directed motion; in English and German, speakers follow a different pattern in that concepts based on features of the ground traversed by the figure in motion are critical in motion event construal. Thus, one and the same situation will be described as un homme marche dans la rue ‘a man walks in the street’ or a man is walking down a street or ein Mann geht eine Straße entlang ‘a man goes a street along’. There is a further contrast, in this case between German and English, with respect to the verbal inventory. While the German lexicon offers a rich repertoire of manner verbs expressing locomotion with only a few path verbs, the English lexicon has a number of path verbs of Romance origin (e.g., to approach, to enter, to advance) in addition to the Germanic manner verbs. Given the option for use of the verbs to walk in versus to enter for example, English native speakers may, however, show preference for the Germanic manner verb (cf. Stefanowitsch, Reference Stefanowitsch, Goschler and Stefanowitsch2013).

Differences and similarities at this level formed the basis in selecting the L1 and L2 groups. L1 French learners of English and German have to acquire new forms and – with these forms – different criteria for event construal in the context of language use. Instead of varying the factor L2 with respect to typological features in the domain of spatial relations, as in numerous previous studies (Cadierno & Ruiz, Reference Cadierno and Ruiz2006), variation in the present case is within one type – satellite-framed languages – with the control factor given by the L1. Both groups of learners share the same criteria for event construal given the task. They acquire languages, which, in addition to new forms, require the construction of novel patterns of conceptualisation. The relevant contrast between German and English, as the L2, lies in the repertoire of verbs, given the distribution between manner and path verbs. L1 speakers of French can select verbs in L2 English that fit their L1 frame, which is not the case for German. This specific combination of languages allows us to address questions on the stability of L1-based conceptual framing as well as factors related to the selection and use of lexical items that correspond to these frames, despite infrequent use in the TL.

4.2. study design

4.2.1. Participants

The L1 speakers were all students (aged between 19 and 30) without advanced knowledge of any other language. The L1 English speakers were participants in a summer school at the University of Heidelberg, all with very little knowledge of German. Recordings in English were carried out during the first days of their stay, and the experiment was conducted in English by a native speaker. The L1 German and L1 French speakers were students at the University of Heidelberg and the University of Paris VIII, respectively, and the recordings were conducted in each case by a native speaker at the participants’ home institution. Participants with advanced knowledge of a second language were excluded from the experiments.

Two groups of L2 speakers were recruited, both with French as L1 and English (n = 19 age 21 to 32) and German (n = 20, age 19 to 28) as their L2, respectively. All L2 speakers were given a questionnaire on their linguistic as well as social background. The homogeneity of the groups in terms of L2 competence was ensured based on formal language tests (a re-narration test in the case of the English L2 group, a C1 language certificate (C1 of the European Frame of Reference) in the case of the German L2 group). Knowledge of a third language was stated as limited by this group. All French learners of English started learning English at school after the age of ten. English was also studied at university level and used later on a daily basis as professionals, either as teachers (second and third level), translators (English to French), or in their professions (export, marketing). All had spent several periods of time in an English-speaking country. In their re-narrations, the learners showed no formal errors, and lexical proficiency was high, but aspects of information structure (e.g., topic management; temporal frames) did not fully match the patterns found for this task in L1 English. All L1 French–L2 German learners also started learning German after the age of ten and were university students studying German when recorded. Recordings were carried out while participating in a German language course for advanced learners at the Heidelberg University. For admission to the Faculty of Modern Languages in the German department, students have to have a C1-certificate. All subjects indicated some knowledge of English. All L2 subjects had spent longer periods of time abroad where they used the L2 on a regular basis. The English L2 group was recorded at the University of Paris VIII and Paris X. The German L2 group was recorded at Heidelberg University.

4.2.2. Stimuli

The stimuli were short live-recorded video clips (6 sec) showing situations in which persons or vehicles move along a path with a more or less evident goal (Figure 1). The 13 critical clips were embedded in 44 filler items which covered events of different types: causatives, activities, states. The inter-stimulus interval was 8 sec and showed a blank screen (see ‘Appendix B’ online for full set of stimuli <https://doi.org/10.11588/data/ZMWDP5>).

Fig. 1. Example stimuli.

4.2.3. Procedure

Participants were recorded in university labs. They were seated in front of a monitor on which the stimuli were shown. The instruction given is as follows: “You will see a set of video clips, 57 in all, showing everyday events which are not connected with one another. Each scene is preceded by a blank screen with a focus point. Your task is to tell what is happening and you may begin as soon as you recognize what is going on. It is not necessary to describe the scene in detail – just focus on what is happening. The task takes approximately 20 minutes” (see ‘Appendix A’ online for instructions in French and German <https://doi.org/10.11588/data/ZMWDP5>). The instruction was given in the language to be used in the experiment. Participants’ spontaneous responses were audio-recorded.

4.3. hypotheses

Previous research on the languages in the present study (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Weimar, Flecken, Lambert and Stutterheim2012; Flecken et al., Reference Flecken, Carroll, Weimar and Stutterheim2015b; Gerwien & Stutterheim, Reference Gerwien and Stutterheim2018) form the basis for the following hypotheses:

-

1. The groups of L1 speakers will differ with respect to the event frames selected in relation to event type: French L1 speakers draw on a dynamic frame with path verbs and directional adjuncts, or a stationary motion frame with manner verbs and locational adjuncts or zero adjuncts, depending on the features of the situation. German and English speakers will predominantly select dynamic event frames with manner verbs in combination with directional satellites.

-

2. The groups of L2 speakers will differ with respect to the event frames selected from the groups of native speakers of the TL. At the level of linguistic means, differences will concern use of satellites and combinations of verbs and satellites. Patterns will align more with those observed in the L2 speakers’ L1.

4.4. analyses

4.4.1. Coding categories

The oral responses for the 13 critical clips were transcribed and inserted in a spreadsheet with the sentence as the unit of analysis. Transcriptions and coding were carried out by native speakers of the respective language and were checked by a second researcher. Coding was rather unproblematic given the categories applied for the analyses. The few cases where coders did not agree initially (mainly questions of segmentation) were submitted to a group of four researchers, who could resolve issues by discussion. The forms coded are verb type (manner/path/other), prepositional phrases as spatial adjuncts (location/direction: a man is walking on/down the street), and verb particles (ein Mann geht die Straße entlang ‘a man walks the street along’). All forms which provide spatial information outside the verb are termed satellites and include noun phrases (a man is passing a building ), prepositional phrases, and particles.Footnote 6 Statistical analyses were carried out for both formal and spatial semantic categories as well as their combinations (constructions of the type verb + satellite). The coding of verb types and satellite types in each language also allowed us to evaluate an additional factor: the diversity of lexical items used. We consider lexical diversity as an approximation of the consistency of the L1 speakers’ output (adding to sheer frequency of occurrence), as well as an indicator for the ability of L2 speakers to mirror the diversity found in their TL.

4.4.2. Statistical analyses

In order to assess the statistical reliability of the contrasts between the language groups, as observed on the basis of counting specific occurrences, a number of statistical models was set up using the statistical software R, version 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019) as well as the packages ‘lme4’, version 1.1-21 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015), ‘car’, version 3.0-7 (Fox & Weisberg, Reference Fox and Weisberg2019), and ‘multcomp’, version 1.4-10 (Hothorn, Bretz, & Westfall, Reference Hothorn, Bretz and Westfall2008). The majority of the analyses were carried out with random-effects binomial logistic regression models. In these models the response variable of interest was binary coded (e.g., use of a manner of motion verb or use of a satellite encoding location: yes = 1, no = 0). The only fixed factor in all models was language group with five levels. In addition, random intercepts were included for both the random variable “participant” as well as “item”. A main effect of the predictor language group was consistently calculated using sums of squares (Type II) with the ‘Anova’ function from the ‘car’ package. Relevant pairwise comparisons were retrieved from the original model using the ‘glht’ function from the ‘multcomp’-package. Since there are specific theory-based predictions for all relevant comparisons, alpha level adjustments were not required (O’Keefe, Reference O’Keefe2003). To improve readability, indications of statistical significance were included in all figures below. Details on model specifications, full model outputs, and relevant comparisons can be found in ‘Appendix C’ (online <https://doi.org/10.11588/data/ZMWDP5>).

4.5. results

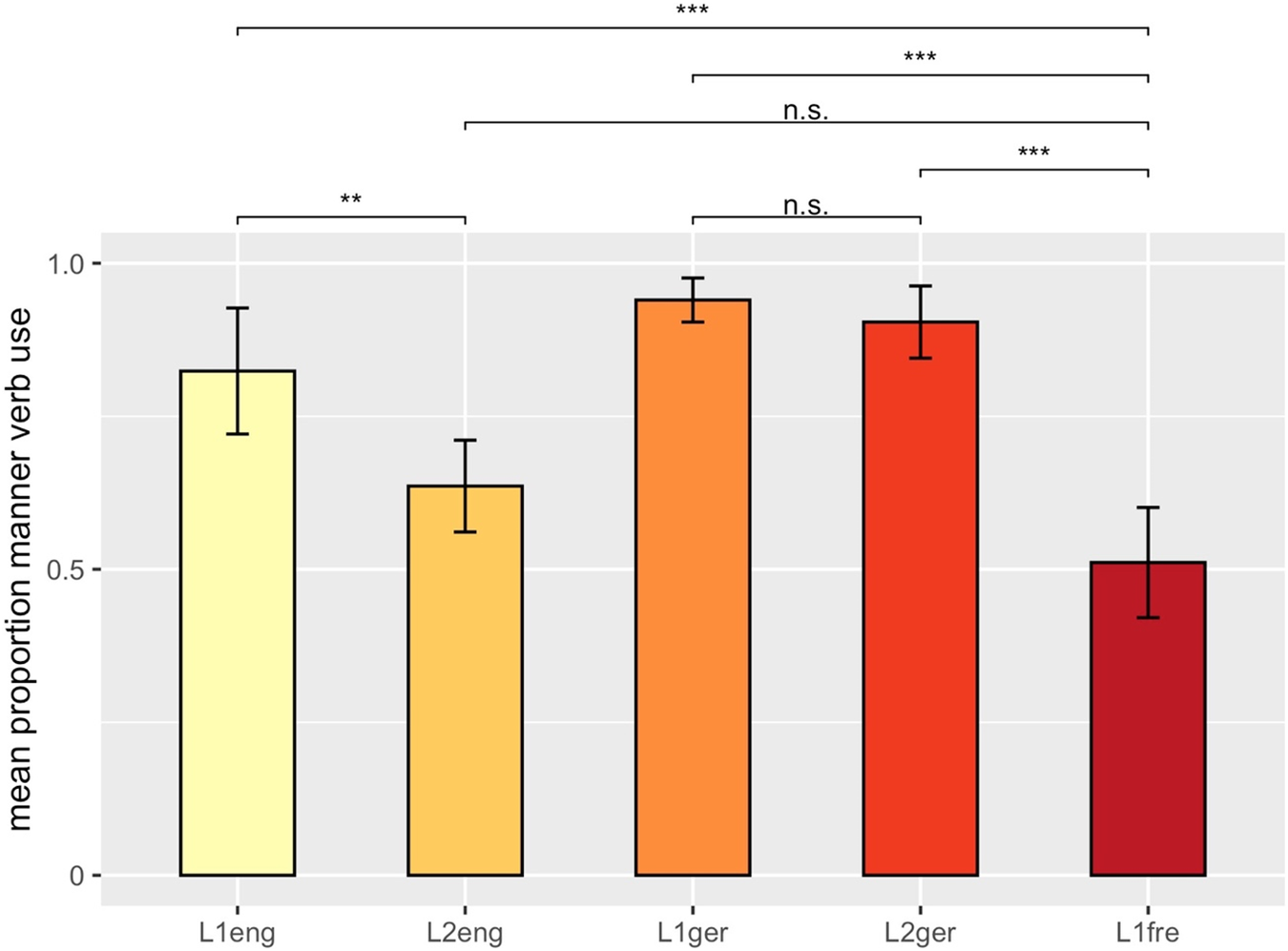

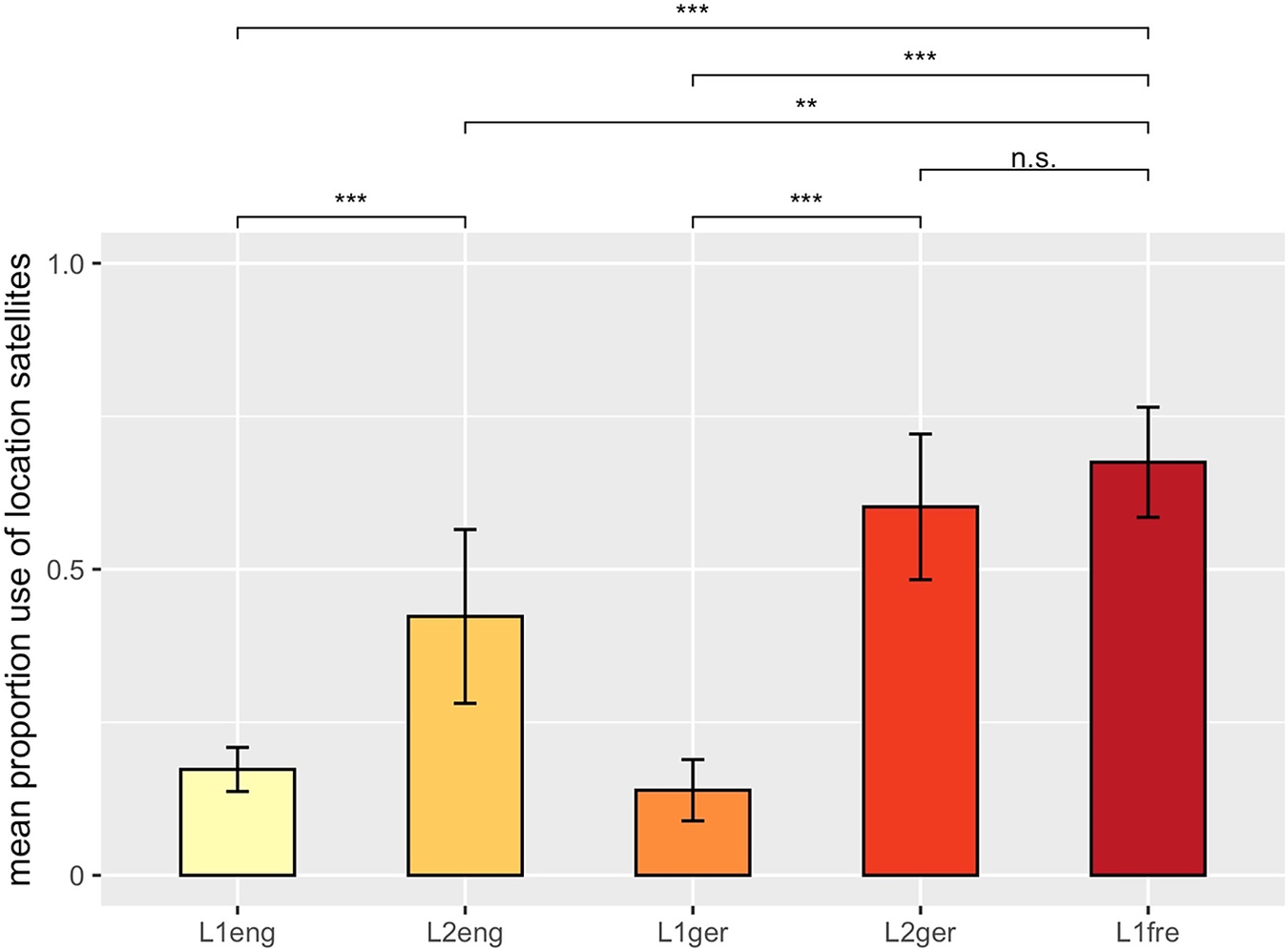

The initial analyses compared the frequency of semantic verb types (model 1 and 2 in ‘Appendix C’) and semantic satellite types (prepositional phrases and particles, model 3 and 4 in ‘Appendix C’) across the five groups (L1 French, L1 English, L1 German, and the L2s German, English). Figure 2 and Figure 3 show results for the use of manner and path verbs in describing the stimuli across language groups, as well as the results of the relevant pairwise comparisons. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the results for the two different types of spatial satellites (location/direction). All four models showed a main effect of language group.

Fig. 2 Frequency of manner verbs (the graph shows by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

Fig. 3 Frequency of path verbs (by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

Fig. 4 Frequency of satellites referring to location (the graph shows by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

Fig. 5 Frequency of satellites referring to direction (the graph shows by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

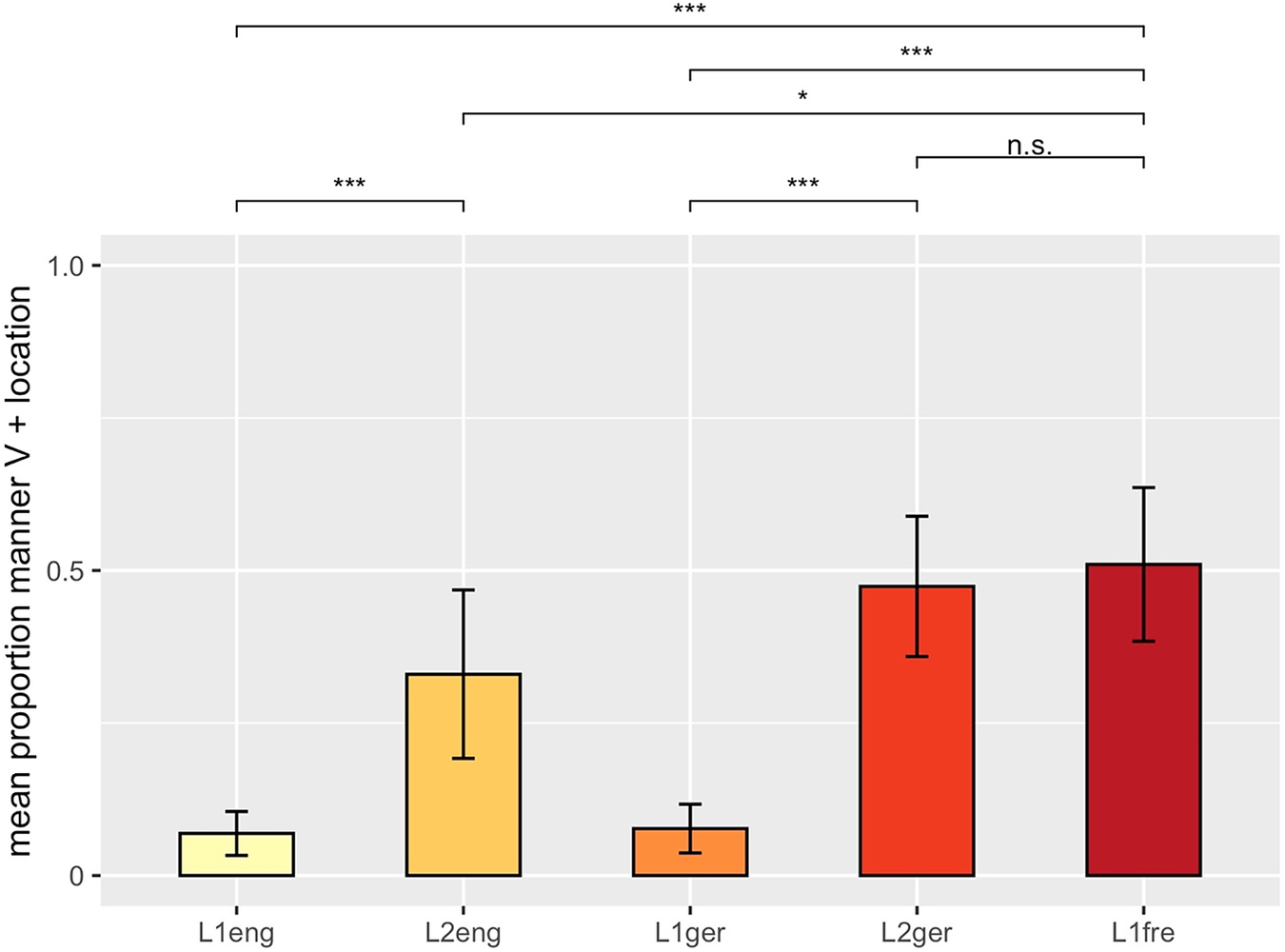

Next, we compared frequency of use of constructions. We distinguish two types of constructions: manner verbs with a directional satellite (Figure 6, model 5 in ‘Appendix C’) and manner verbs with a locational satellite (Figure 7, model 6 in ‘Appendix C’). If a manner verb was combined with more than one locational or directional element it was taken as one datapoint.Footnote 7 Both models showed a main effect of language group. Constructions with both locational and directional satellites also occurred. However, despite numerical differences, there was no statistically significant main effect of language group. This analysis is not reported here (but see model 7 in ‘Appendix C’).

Fig. 6 Frequency of constructions with a manner verb and a directional satellite (the graph shows by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

Fig. 7 Frequency of constructions with a manner verb and locational satellite (the graph shows by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

Participants also produced utterances with a verb, but no adjunct (such as une femme marche ‘a woman walks’). These zero-adjunct constructions occurred with the following frequency in the 5 language groups: 15% in French, 2% in German, and 0% in English; 11% in L2 German, and 5% in L2 English (cf. discussion in Stutterheim et al., Reference Stutterheim, Gerwien, Bouhaous, Carroll and Lambert2020).

A further set of analyses targeted lexical diversity across language groups (Figure 8), indicating the level of consistency in the selection of specific lexical items: verbs in representing the event type and satellites in expressing the type of spatial concept. Verb diversity was calculated by dividing the total number of unique verb types by the total number of verbs per language (analyses used over-participants and over-item aggregated data; e.g., 6 unique / 13 total = 0.46). Satellite diversity was calculated by dividing the total number of unique satellites by the total number of satellites (analyses used over-participants and over-items aggregated data). Note that statistical significance is only indicated in Figure 8 if both types of aggregation yielded consistent results (models 8A, 8B, and 9A, 9B in ‘Appendix C’). There was a main effect of language group in the verb diversity analyses, but not in the satellite diversity analyses.

Fig. 8 Diversity of lexical items used; left: verb diversity; right: satellite diversity (the graph shows by-subjects aggregated data; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

5. Discussion of results

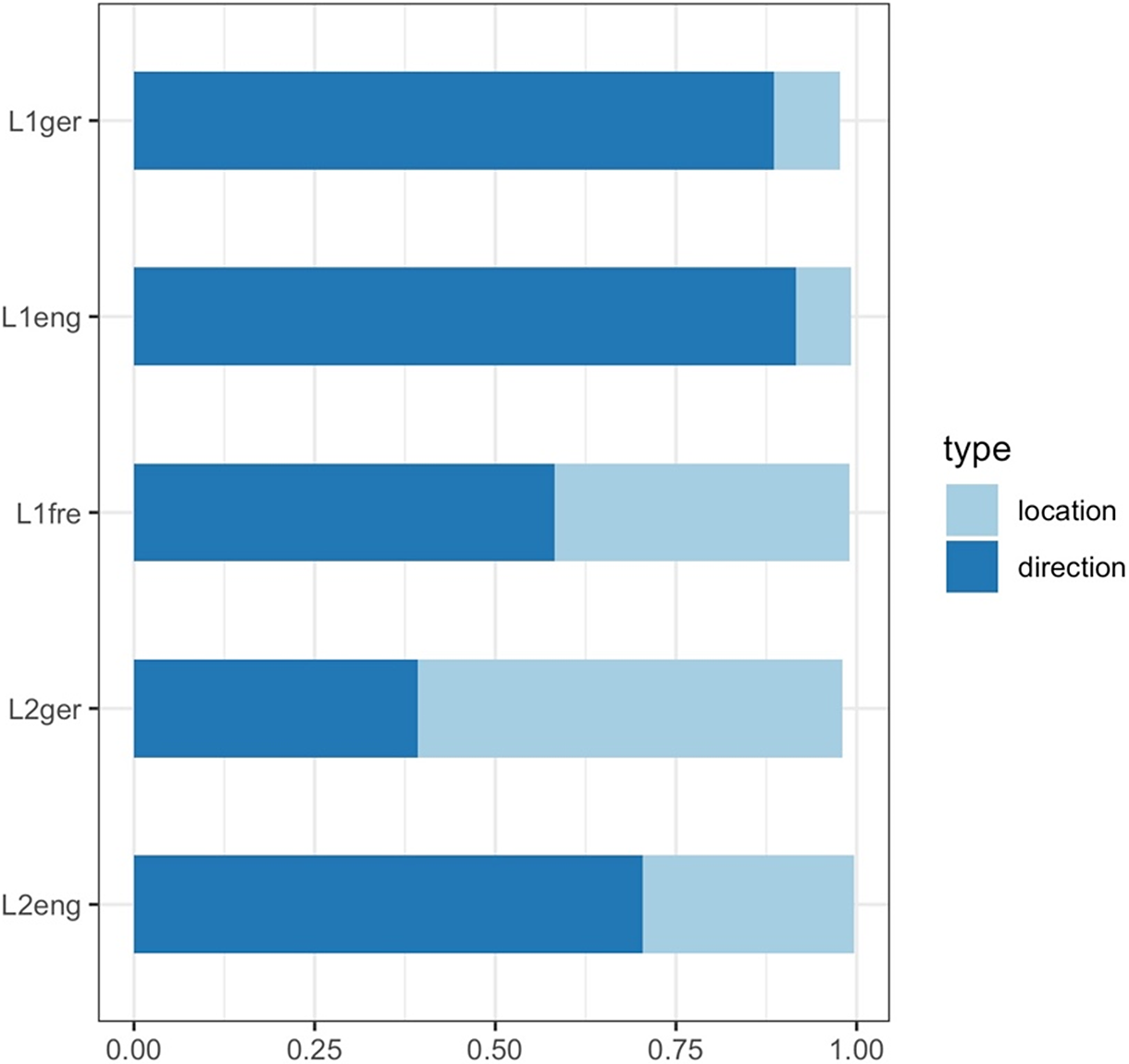

5.1. L1 groups

The statistical analyses confirm results of previous studies on the typological features of the three languages (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Strömqvist and Verhoeven2004; Pourcel & Kopecka, Reference Pourcel and Kopecka2005; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Weimar, Flecken, Lambert and Stutterheim2012; Muñoz & Cadierno, Reference Muñoz and Cadierno2019). There is a significant difference between speakers of English and German, on the one hand, and French speakers on the other hand, with respect to the relative number of manner and path verbs used. French speakers use a higher number of path verbs. Although French is a verb-framed language, French speakers use manner verbs at a rate of approximately 50% across all utterances. German speakers use manner verbs in almost 100% of all cases, while occurrences are lower for the English group. Analyses of the use of constructions confirm established contrasts in language-specific patterns of event construal for these languages: in French, directed motion events are expressed using path verbs with adjuncts providing further information on direction, quasi-exclusively in relation to a landmark or goal (vers (x) ‘towards (x)’). If events are construed on the basis of manner of motion, the event is typically expressed in terms of its location (une femme marche and une femme marche dans la rue ‘a woman walks (in the street)’). Information on the direction of the figure is only rarely provided (Figures 6 and 7).

We conclude that, in German and English, manner of motion is anchored in a different event frame in that satellites (prepositions / verb particles) encode directed motion related either to a landmark (zu ‘to’, to, towards) or to features of the ground (along, down) (see Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12). Figure 9 shows the frequency of occurrence of the event types with directional vs. locational spatial reference. In sum, the picture obtained in the data analysis confirms hypothesis 1 on the typological differences between the three languages.

Fig. 9 Ratio of directional versus locational event framings (total number of each type / total number of utterances).

Contrasts with respect to event construal appear at the level of the lexical items used to express the events depicted in the scenes (Figure 8). French speakers use a significantly wider range of verb types compared to the other groups, a finding that is grounded in the results for the frequency with which manner and path verb are used (Figure 2, Figure 3). This means that the forms used by German and English speakers are more consistent. Significantly, this homogeneity can be viewed as an indicator of the input which learners of the respective language encounter. The picture differs, however, for the satellites. While diversity in general does not differ significantly between groups (Figure 8), diversity of specific types (direction/location) does (Figure 4 and Figure 5, and Figure 10 and Figure 11). L1 French speakers use a wide repertoire of prepositions which refer to the overall location, in contrast to the German and English speakers who use a wide range of prepositions to express differences in direction.

Fig. 10 Distribution of prepositions in L1/L2 German and L1 French (type frequency / total number of prepositions).

Fig. 11 Distribution of prepositions in L1/L2 English and L1 French (type frequency / total number of prepositions).

5.2. L2 groups

The task for the French learners of both Germanic languages involves two components: acquisition of the respective lexical items with their syntactic properties, and acquisition of the associated principles in event construal which form the basis for the use of the constructions (verb + satellite) in the relevant contexts. Significantly for the learning process, the learners have to uncover the conceptual frame that underlies the use of these forms in the input: in English and German reference to manner of motion constitutes a core factor in event construal. This functions in combination with a range of specific forms and associated concepts that express differences in direction. This stands in sharp contrast with the pattern in French where the selection of manner of motion typically activates an event frame based on non-directed motion in that it focuses location only, given the fact that means to express direction are encoded via the verb.

The two groups of advanced learners of English and German mainly use manner verbs. However, in contrast to the TL speakers, they combine manner verbs with locational adjuncts to an extent not evidenced in the TL.

There are also differences between the two L2 groups. A significant difference lies in the number of path verbs used (Figure 3). L2 English speakers employ more path verbs than L2 German speakers, and even more than TL English speakers. At this level in the analysis, it seems as if the L2 English speakers were more successful in uncovering the pattern underlying event construal in the TL compared to the L2 German speakers. The number of verbalisations encoding directed motion is higher when compared to the L2 German speakers. However, a closer look at the data shows that the L2 speakers of English use path verbs in combination with adjuncts of the type ‘direction of figure towards goal’. Encodings of direction, based on specific features of the ground (down, along, entlang ‘along’), however, are practically absent in L2 English as well as L2 German. Therefore, the findings for the L2 speakers correspond largely to the patterns in L1 French at the level of event construal. This confirms hypothesis 2.

5.3. the factor frequency

In interpreting the role of frequency in the input, and its role in acquisition in the present context, a number of factors have to be put in place. Starting with the verbs expressing manner of motion, the learners have acquired the verbs that are frequent in the TL, and they use them. In German, manner verbs are more or less the only option, and the L2 speakers acquire and use them accordingly.Footnote 8 However, L2 speakers of English differ from the TL speakers in that the L2 speakers use a significantly higher number of path verbs in the given corpus. Significantly, the frequency of these verbs in the input does not correspond to the frequency in the L2.

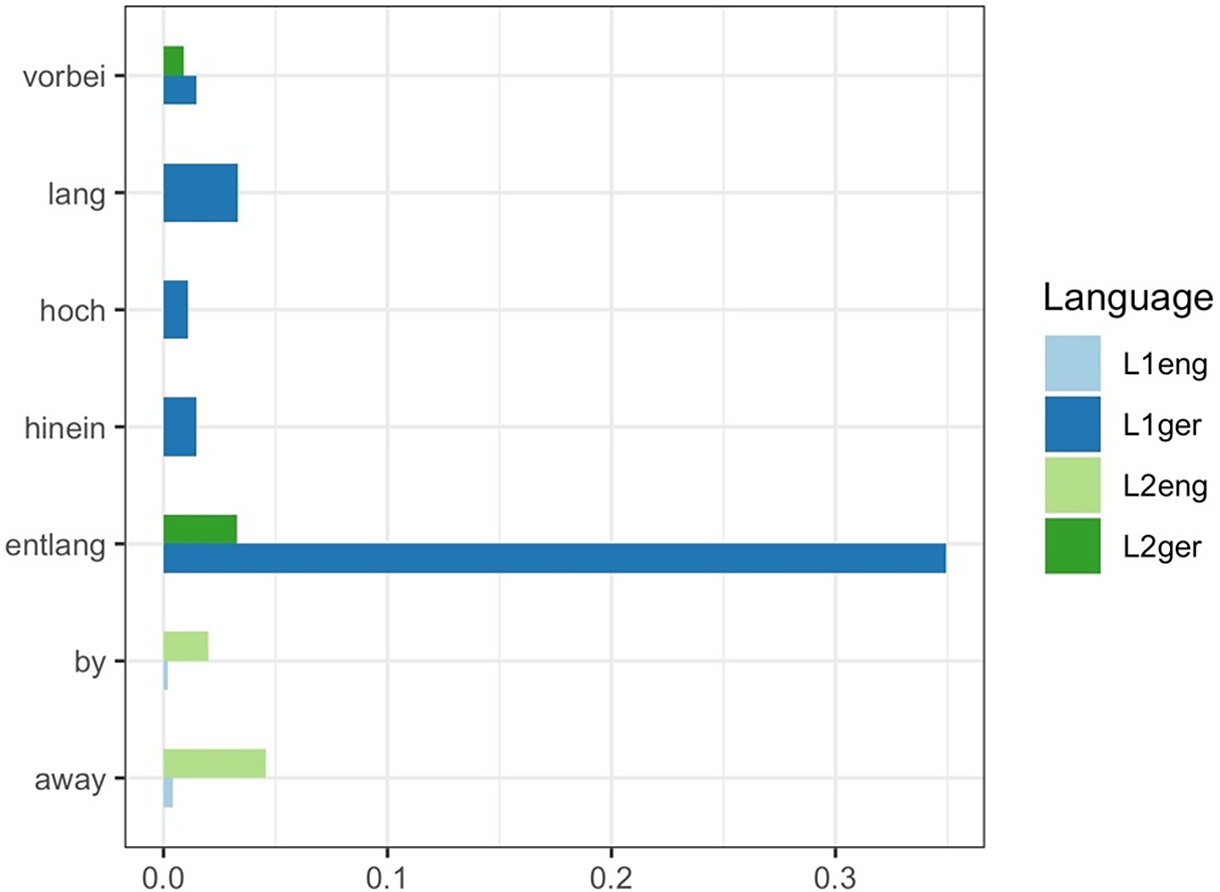

Furthermore, in the case of forms encoding spatial relations, the most frequent lexical item in the L1 German descriptions when encoding directional information is the verb particle entlang ‘along’ (Figure 12). This form, however, is rarely used by the L2 speakers. The same holds for down in L2 English, although this form is highly frequent in the L1. A closer look at all satellite forms used by the five groups clearly shows that the frequency of forms with respect to tokens, as well as semantic types, differs substantially for the TL native speakers and L2 speakers (see Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Fig. 12 Particles across language groups (type frequency / total number of particles).

The results clearly show that L2 speakers do not construe and express motion events according to the patterns which are highly frequent in the TL data. The findings do not confirm a position which takes frequency of occurrence and repetition as the major driving force for L2 comprehension and production (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Simpson-Vlach and Maynard2008). If this assumption were correct, the learners of German and English, who are at a very advanced stage, should have acquired the TL pattern where manner verbs combine with forms expressing direction in highly specific terms (particles/prepositions).

The findings bring into focus a basic problem which has been pointed out in Section 2.4. Studies in the framework of usage-based theories on L2 acquisition view acquisition as successful once the forms or constructions have been stored in memory. Although in Wulff and Ellis (Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018) the authors formulate a statement which at first sight would seem to be in accordance with the present conclusions – “Since everything is filtered through the lens of the L1, not all of the relevant input is in fact taken advantage of” (Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018, p. 50) – there is an important difference to the position advocated in the present paper. Their analyses do not target the question of adequate use, i.e., the acquisition of the range of factors in event construal which underlie language use in context. The factors viewed as relevant for L2 intake are saliency, contingency, and learned attention allocation (Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018, p. 43). The impact of these factors, however, is identified at the form level only.

The present results point to the fact that the acquisition of L2 forms is no more than an initial step. The acquisition of the underlying principles when conceptualising content for expression, which provides the basis for the use of these forms, constitutes the crucial second step. Significantly, the initial step does not necessarily lead to the second level of acquisition. The generalisation that L2 learning “follows statistical learning mechanisms” (Wulff & Ellis, Reference Wullf, Ellis, Miller, Bayram, Rothman and Serratrice2018, p. 39) as the central explanatory factor in L2 acquisition does not give due recognition to the complexity of the task that the L2 learner faces.

6. Conclusion

In the present study verbalisations by L1 speakers were compared with those of L2 speakers when conveying information on the same set of motion events. Despite the fact that the L2 speakers are at very advanced proficiency levels with adequate exposure to the L2s in terms of the frequency with which they would have encountered references to motion events, the contrasts regarding the roles which the basic concepts serve in motion event construal across the two languages reveal the deep-seated ramifications at issue in language acquisition. The L2 speakers’ responses to the stimuli differ markedly from those of TL speakers, both at the level of event construal and with respect to the types of constructions used, while correspondences are confined to the level of specific lexical verbs. The L2 speakers proceed in terms of fundamental features of their L1 which determine event construal, as well as in terms of the constructions and lexical means at the level of spatial function words (prepositions/particles), despite the many years of exposure to the TL. The findings are not in accordance with the assumption that “it is the number of times the string appears in the input that determines fluency” (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Simpson-Vlach and Maynard2008, p. 384), or as Littlemore (Reference Littlemore2009, p. 36) states: “Probabilistic processing can be seen as a kind of ‘intuitive statistics’. In terms of construal, the argument here would be that learners gradually attune themselves to the construals preferred by the target language and match them to the situations in which they encounter them. They are thus able to use them appropriately without being fully aware of the fact that they are doing so.” While it is indisputable that frequency plays an important role for language acquisition, it is precisely this level of language competence which is not automatically and unconsciously supported by frequency of input. The criteria which determine event construal are deeply rooted in any given linguistic system in the form of grammaticalised categories, as well as categories which are systematically represented in the lexicon. Research in the field of language and cognition (Slobin et al., Reference Slobin, Bowerman, Brown, Eisenbeiß, Narasimhan, Bohnemeyer and Pederson2010; Lupyan, Reference Lupyan2016; for a review see Thierry, Reference Thierry2016) has shown how these factors shape the structure of the relevant knowledge base as well as the associated processes of conceptualisation. The problem for the language learner lies in the fact that these criteria are not represented in overt terms. Neither the verbs, nor the constructions as such, reveal this basic difference between German/English and French at the level of event construal for the learners.

In contrast to processes in L1 acquisition where cognitive structures are built up, and in line with linguistic experience, the L2 learner’s knowledge at a conceptual level has to be recognised as a decisive precondition in the acquisitional process. This means that the role of frequency which has been found for L1 acquisition and which has been interpreted convincingly in the framework of a usage-based approach (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello, Kuhn, Siegler, Damon and Lerner2006; for a discussion see Lieven, Reference Lieven2010) does not find a parallel in L2 acquisition and use. As the present results show, learners do not seem to “attune themselves to the construals preferred by the target language, and match them to the situations in which they encounter them” (see above, Littlemore, Reference Littlemore2009, p. 36). In language production, the planning process starts with the conceptualisation of content for speaking. At this level, speakers draw on deeply entrenched conceptual structures which are triggered automatically in response to external stimuli or internal factors. When preparing to describe a motion event, L2 speakers activate the abstract schemata formed on the basis of their L1 – as our data show. These schemata function as ‘pull factors’ in the sense that they determine the requirements which have to be served by the L2 linguistic material. This results in formally adequate but functionally infelicitous language use.

Note that our findings have implications with regard to the current debate on language and cognition. If it were the case that every adult had basically the same conceptual representation of a situation, as claimed by universalists, then ‘the mapping’ (Jackendoff, Reference Jackendoff1990) onto the new language should not be affected by specific features in the L1. The present results show how the relevant cognitive processes are structured by the L1, and more specifically by the event frames which transcend the L1 (cf. the notion of conceptual transfer overview in Jarvis & Pavlenko, Reference Jarvis and Pavlenko2008; Pavlenko, Reference Pavlenko2011; Sharpen, Reference Sharpen2016; Munoz & Cadierno, Reference Muñoz and Cadierno2019 Footnote 9 ).

When confronted with a verbal task, speakers can draw on all resources which are useful in solving the task. L2 speakers follow the pathway from conceptualisation to formulation just as L1 speakers. The first step involves the activation of an event frame in response to the visual input. For a speaker of French this means that two frames may be potentially activated: the directed motion event frame, with a figure-related spatial concept of motion towards a goal, or the ‘stationary’ motion event frame focusing on the overall location, depending on specific features of the situation at the level of goal-oriented directionality (Gerwien & Stutterheim, Reference Gerwien and Stutterheim2018). This differs significantly from L1 German and English, where two frames involving direction are activated depending on a potential goal: directed motion based on contours of the ground and goal-directed motion. Despite their advanced proficiency, the L2 speakers in the present study have not acquired the TL patterns in event framing. Moreover, the two groups show language-specific patterns. In German, manner verbs are more or less the only option available for expressing motion events. L2 learners pick up these verbs, but for the L2 speakers with French L1 these verbs activate the ‘stationary’ motion event frame in the majority of cases. The English L2 speakers, by contrast, use more path verbs, probably supported by the corresponding forms in their L1, since the L2 forms show a Romance origin. But note that, although the L2 speakers of English use manner verbs with directional spatial concepts, they still proceed on the basis of the L1 patterns in that they follow a figure-based framing and not a ground-based framing as required in the TL. This leads us to the conclusion that, in acquiring the lexical means for the expression of motion events, the learners have not ‘cut’ the link to the highly abstract event frames established in the course of L1 acquisition.

Our results point to the extent to which conceptual framing may outweigh frequency as a factor in L2 acquisition. Since there are no formal indicators for this abstract level of knowledge in the input, even the high frequency of a specific pattern in the input does not help the learner. It would be important to include this crucial component of linguistic knowledge in formal language teaching.

Appendices

Appendices A, B, and C can be found online at <https://doi.org/10.11588/data/ZMWDP5>.