Introduction

Occupational Burnout (OB) is a relatively recent entity that was first mentioned in the literature in the late 1960s (Bradley, Reference Bradley1969). The following 50 years of uncoordinated research resulted in multiple, somehow-contradictory definitions and measures of OB worldwide. The current situation reflects this semantic and methodological heterogeneity: even the World Health Organization (WHO) is uncertain how to deal with OB. The WHO included burnout in the tenth revision of the international classification of diseases, but in the forthcoming eleventh revision (WHO, 2019), specified that it was a phenomenon and not a disease.

Nowadays, the application of the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) in diagnostic and prognostic processes used in healthcare is essential (Newman and Kohn, Reference Newman and Kohn2009). However, the lack of harmonisation regarding acceptable validity standards or criteria for various mental health measures (Haberer et al., Reference Haberer, Trabin and Klinkman2013) directly challenges the EBM application in diagnosis and, subsequently, in treatment of mental health disorders. With respect to OB, this lack of harmonisation in OB definition and measure is particularly salient, precluding a reliable estimation of its prevalence (Rotenstein et al., Reference Rotenstein, Torre, Ramos, Rosales, Guille, Sen and Mata2018) and triggering to exaggeration of this phenomenon as a 21st century epidemic (Bianchi, Reference Bianchi2017; Mirkovic and Bianchi, Reference Mirkovic and Bianchi2019) or sometimes it can result in underestimation (Doulougeri et al., Reference Doulougeri, Georganta and Montgomery2016). Therefore, the Network on the Coordination and Harmonization of European Occupational Cohorts (OMEGA-NET) decided to prioritise this issue (Guseva Canu et al., Reference Guseva Canu, Mesot, Gyorkos, Mediouni, Mehlum and Bugge2019) and to propose a harmonised definition of OB as a health outcome to be used in future longitudinal studies (Guseva Canu et al., Reference Guseva Canu, Marca, Dell'oro, Balázs, Bergamaschi, Besse, Bianchi, Bislimovska, Bjelajac, Buggez, Busneag, Çağlayan, Cernițanu, Pereira, Hafner, Droz, Eglite, Godderis, Gündel, Hakanen, Iordache, Khireddine-Medouni, Kiran, Larese-Filon, Lazor-Blanchet, Légeron, Loney, Majery, Merisalu, Mehlum, Michaud, Mijakoski, Minov, Modenese, Molan, Van Der Molen, Nena, Nolimal, Otelea, Pletea, Pranjic, Rebergen, Reste, Schernhammer and Wahlen2020). The next step is thus to harmonise the measurement of OB.

There is no consensus on the measurement of OB (Poghosyan et al., Reference Poghosyan, Aiken and Sloane2009) and all identified published measures are Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) (Rotenstein et al., Reference Rotenstein, Torre, Ramos, Rosales, Guille, Sen and Mata2018; Guseva Canu et al., Reference Guseva Canu, Marca, Dell'oro, Balázs, Bergamaschi, Besse, Bianchi, Bislimovska, Bjelajac, Buggez, Busneag, Çağlayan, Cernițanu, Pereira, Hafner, Droz, Eglite, Godderis, Gündel, Hakanen, Iordache, Khireddine-Medouni, Kiran, Larese-Filon, Lazor-Blanchet, Légeron, Loney, Majery, Merisalu, Mehlum, Michaud, Mijakoski, Minov, Modenese, Molan, Van Der Molen, Nena, Nolimal, Otelea, Pletea, Pranjic, Rebergen, Reste, Schernhammer and Wahlen2020), i.e., measures completed by the patient (Jokstad, Reference Jokstad2018). There are about a dozen different OB PROMs, eight of which were considered as valid for measuring OB in mental health professionals (O'Connor et al., Reference O'connor, Muller Neff and Pitman2018), including the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (Maslach and Jackson, Reference Maslach and Jackson1981), the Pines' Burnout Measure (BM) (Malakh-Pines et al., Reference Malakh-Pines, Aronson and Kafry1981), the Psychologist Burnout Inventory (PBI) (Ackerley et al., Reference Ackerley, Burnell, Holder and Kurdek1988), the OLdenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001), the Professional Quality of Life Measure (ProQOL) (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010), the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) (Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen2005), the Children Services Survey (CSS) (Glisson and Hemmelgarn, Reference Glisson and Hemmelgarn1998) and the Organizational Social Context (OCS) (Glisson et al., Reference Glisson, Landsverk, Schoenwald, Kelleher, Hoagwood, Mayberg, Green and Health2008). Considering the diversity of these PROMs, a closer look at their validity should inform their use in medical research and practice. The objectives of this systematic review were to assess the validation processes used in each of the selected PROMs and to grade the evidence of psychometric quality to recommend the most valid PROM(s) for use in medical practice and epidemiological research on OB.

Methods and analysis

We performed this systematic review following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Protocol and registration

A review protocol is available on the international database PROSPERO with the registration number CRD42019124621 on the following link: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=124621.

Eligibility criteria

We searched for studies assessing the psychometric properties of eight OB PROMs considered as validated for measuring burnout in mental health professionals (O'Connor et al., Reference O'connor, Muller Neff and Pitman2018): MBI, BM, PBI, OLBI, ProQOL, CBI, CSS and OCS. Henceforth we focussed on PROMs dealing with OB exclusively, leading to the final inclusion of five PROMs. We excluded ProQOL, CSS and OCS because ProQOL measures burnout as a dimension, at the same level as the secondary trauma (Stamm, Reference Stamm2010), while CSS and OCS measure the organisational aspects influencing services efficiency (Glisson and Hemmelgarn, Reference Glisson and Hemmelgarn1998; Glisson et al., Reference Glisson, Landsverk, Schoenwald, Kelleher, Hoagwood, Mayberg, Green and Health2008). We included studies (1) with quantitative testing of psychometric properties; (2) published as original research articles; (3) addressing psychometric properties of at least one included OB PROMs in its original (not translated) version; (4) with a sample size of >100 participants. We excluded studies (1) for which no full text could be found; (2) where one of the five burnout PROMs was used as a reference against another one, not included in this review; (3) where participants were not professionally employed (e.g., students, medical residents).

Data sources and search terms

We performed a systematic literature search for the period from 01/01/1980 to 27/09/2018. This time window was defined based on the fact that the first OB PROM, MBI, dates from 1981. We used three databases to search for eligible studies via the online catalogue of databases OVID interface: MEDLINE, PsycINFO and EMBASE. An experienced librarian reviewed the search strategy that consisted of free-text words to specify three search strings: terms focusing on the burnout PROM of interest (e.g., MBI), terms related to the validation of the PROM and a combination of the two first search strings results. Finally, one additional search string consisted of removing duplicates. In addition, we checked the reference lists from articles and reviews retrieved in our electronic search for any additional studies to include. For the PROM for which no article was found, we searched for their primary sources (e.g., books), and included them in this review. The full search strategy is available in online Supplementary Table S1.

Data collection and analysis

Study selection

We imported the collected studies in the bibliography software EndNote X8 and selected the studies in a three-step process done by two independent reviewers (SCM and YS). First, the reviewers eliminated possible remaining duplicates within each database and between databases. Second, they examined the title and the abstract of each article. They retained or rejected articles based on the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, the reviewers read the full-text of the remaining articles and followed the same procedure with the selected articles. For each of the three steps, reviewers discussed all discrepancies in the assessment of the studies and, when needed, consulted a third reviewer (IGC).

Data extraction and management

We extracted the data through a two-step process. First, we developed a standardised data extraction form convenient for all kinds of study designs and methods applied. Each burnout PROM had its own exemplary data extraction form (MS Excel file). Two independent reviewers tested the form using articles on different burnout PROMs. They discussed the discrepancies and if needed, consulted a third reviewer for clarification and decision. This process continued until a complete agreement was reached between reviewers on the finalised data extraction form. Then, the two reviewers independently extracted the data and compared their results. The extracted data concerned studies' identification (i.e., authors, year of publication, journal and title); samples' characteristics (i.e., size, sex ratio, age, occupational activity, participation rate, representativity, OB scores' distribution); burnout PROMs' characteristics (i.e., name, version, number of items, number of dimensions, dimensions' names); and statistical methods used for assessing the psychometric properties outcome. We identified the missing data by a code depending on the reason why they are missing (not assessed v. not reported). Secondly, we developed an additional table, in which we extracted quantitative results for each psychometric property for their further analysis.

Validity assessment and grading

We analysed the collected data in four steps. Each step was conducted independently by two reviewers and cross-checked by two other reviewers.

Validity completeness assessment

First, we counted the number of psychometric properties (i.e., face validity, content validity, predictive validity, concurrent validity, convergent validity, discriminant validity, exploratory factorial validity, confirmatory factorial validity, stability, homogeneity and sensitivity) assessed for each burnout PROM. For example, if a study analysed the psychometric property with an exploratory factorial analysis, a confirmatory factorial analysis and a coefficient of internal consistency, three psychometric properties (i.e., exploratory factorial validity, confirmatory factorial validity and internal consistency) were counted. This enabled assessing the completeness of validation for each burnout PROM considered.

Quantitative assessment of psychometric validity

Second, we examined the reported quantitative results and interpreted them using a previously established methodological framework (Marca et al., Reference Marca, Paatz, Gyorkos, Cuneo, Bugge, Godderis, Bianchi and Guseva Canu2020). This framework specifies for each psychometric property, its definition, the method recommended for its analysis, resulting statistics and objective criteria for their interpretation. To assess the correctness of conclusion on validity for each psychometric property of a PROM, we compared the result interpretation by the authors with results interpretation according to the framework. We made this comparison for each burnout dimension separately and rated the degree of discrepancy. The comparison between the interpretations of the authors and the reviewers resulted in a complete agreement when there was no discrepancy between them. A partial agreement corresponded to differences in cutoff values, e.g. a correlation of 0.50 considered as moderate in framework and the authors considered it as strong. A disagreement corresponded to an overall interpretation discrepancy, e.g. the authors interpreted a model as acceptable and the reviewers as not acceptable based on fit indices norms. No comparison was possible when the interpretation of the authors was missing.

Risk of bias assessment

We assessed the risk of bias of each PROM validation study according to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) checklist (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Terwee, Patrick, Alonso, Stratford, Knol, Bouter and De Vet2010). COSMIN triggers rating of PROM development study and content validity studies as very good, adequate, doubtful and not assessed. It assesses the content validity of a PROM through measuring the relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility. Moreover, it considers eight other psychometric properties: structural validity, internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, criterion validity, cross-cultural validity\measurement invariance, hypotheses testing and responsiveness.

Quality assessment

Finally, we graded the quality of evidence on psychometric validity of each burnout PROM following the modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Prinsen, Chiarotto, Westerman, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, De Vet and Mokkink2018). According to the GRADE (Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter, Alonso-Coello, Schunemann and Group2008), there are four levels for the quality of evidence: very low, low, moderate and high. When assessing the quality of evidence for a PROM's validity using the GRADE, the risk of bias, consistency, directness and precision of studies available for each PROM, should be considered together. We started by assuming that the quality of evidence from the studies is high, then we downgraded it depending on the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision.

Results

Selected studies

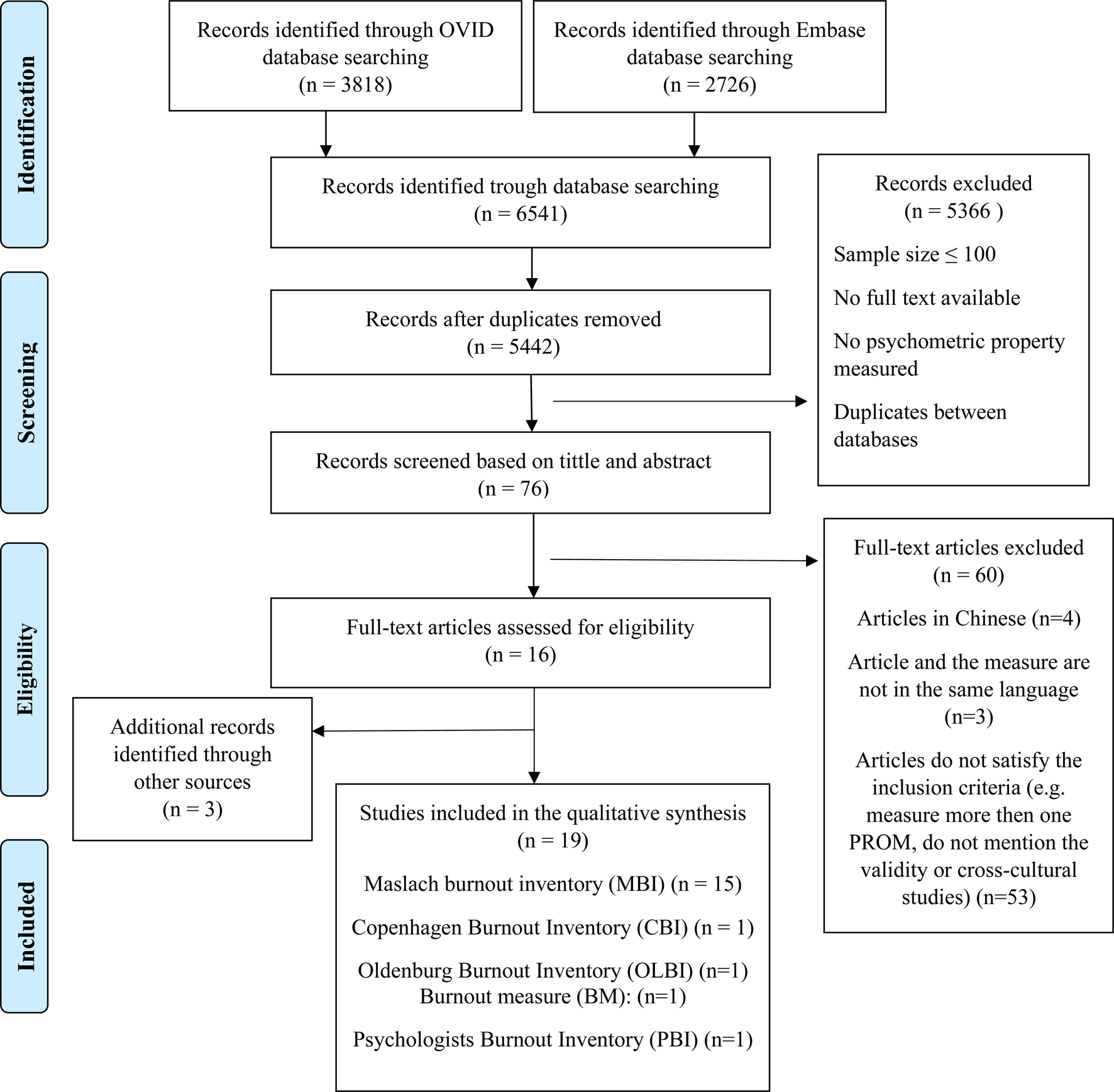

The literature search resulted in 6541 references and 5442 remained after removing the duplicates (Fig. 1). Seventy-six studies were selected for the full-text screening, of which 16 were eligible; three additional studies were identified from reference lists. Overall, 19 studies were thus included in the review, 15 of which dealt with MBI (Iwanicki and Schwab, Reference Iwanicki and Schwab1981; Maslach and Jackson, Reference Maslach and Jackson1981; Gold, Reference Gold1984; Meier, Reference Meier1984; Brookings et al., Reference Brookings, Bolton, Brown and Mcevoy1985; Lahoz and Mason, Reference Lahoz and Mason1989; Gold et al., Reference Gold, Roth, Wright, Michael and Chen1992; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Michael and Kim1994; Yadama and Drake, Reference Yadama and Drake1995; Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000; Kalliath and O'Driscoll, Reference Kalliath and O'Driscoll2000; Beckstead, Reference Beckstead2002; Kim and Ji, Reference Kim and Ji2009; Poghosyan et al., Reference Poghosyan, Aiken and Sloane2009; Chao et al., Reference Chao, Mccallion and Nickle2011) whereas BM, PBI, OLBI and CBI were each examined in one study only (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Flow-chart of the included studies.

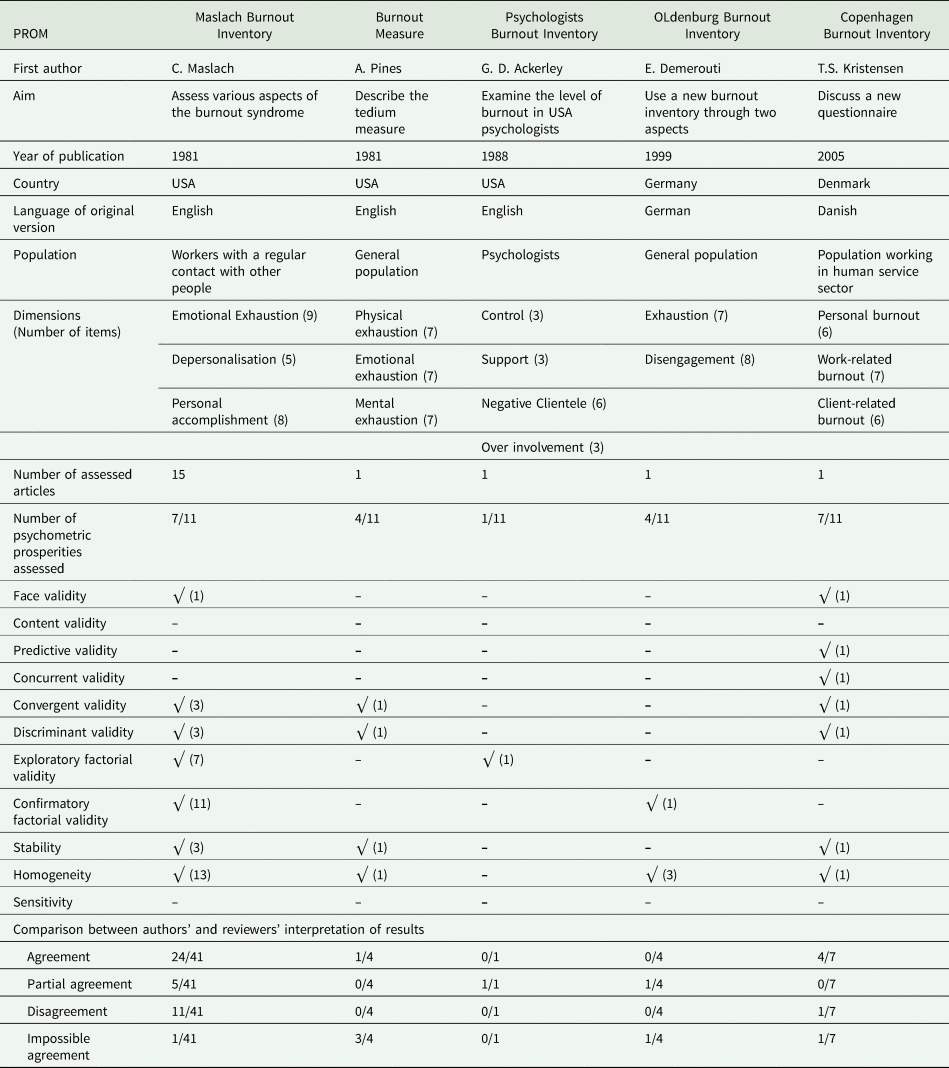

Table 1. Burnout PROMs' description, initial validation performed and validity of statistical analysis interpretation

Results of completeness and quantitative assessment of psychometric validity

MBI and CBI had the most complete validation, with seven psychometric properties assessed out of 11 (Table 1). PBI had the lowest validation completeness with one psychometric property assessed, namely the factorial validity. The results of the agreement between the authors' and the reviewers' interpretations of quantitative results are reported in online Supplementary Table S2. For MBI, we found partial agreement on five analyses of psychometric properties: the discriminant validity (Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000), factorial validity based on exploratory factor analysis (Poghosyan et al., Reference Poghosyan, Aiken and Sloane2009) and confirmatory factor analysis (Yadama and Drake, Reference Yadama and Drake1995), and reliability based on Cronbach's alpha (Brookings et al., Reference Brookings, Bolton, Brown and Mcevoy1985; Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000). We found 11 disagreements related to the convergent validity of MBI (Maslach and Jackson, Reference Maslach and Jackson1981), factorial validity based on exploratory (Lahoz and Mason, Reference Lahoz and Mason1989; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Michael and Kim1994) and confirmatory (Gold, Reference Gold1984; Gold et al., Reference Gold, Roth, Wright, Michael and Chen1992; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Michael and Kim1994; Boles et al., Reference Boles, Dean, Ricks, Short and Wang2000; Kim and Ji, Reference Kim and Ji2009; Poghosyan et al., Reference Poghosyan, Aiken and Sloane2009) factor analyses and reliability measured via Cronbach's alpha (Meier, Reference Meier1984; Kalliath and O'Driscoll, Reference Kalliath and O'Driscoll2000). As we analysed each dimension separately, the exploratory factor analysis is shown in online Supplementary Table S2 with eigenvalues for each dimension and for intensity and frequency (online Supplementary Table S2). However, we disagreed with these results as the value of communality has to be ⩾0.90 to indicate acceptable model fit and the reported value for frequency was 51% and intensity 50.6%. For PBI, we had one partial agreement related to the factorial validity specifically exploratory factor analysis. We had one partial agreement with OLBI concerning factorial validity specifically confirmatory factor analysis. For CBI, we had a disagreement related to discriminant validity. While internal consistency and factorial validity were widely assessed for most PROMs, we found no formal content validity study for any of the selected PROMs.

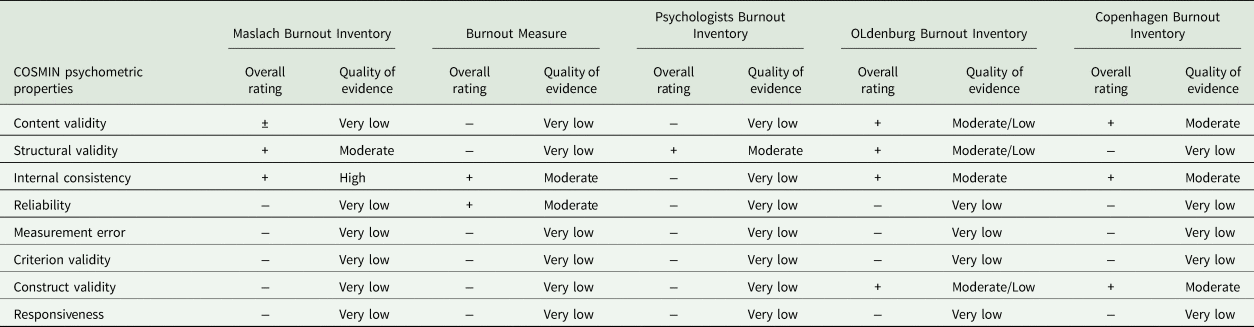

Results of risk of bias and quality assessment

When assessing the content validity of MBI according to COSMIN, we found no data on its relevance, whereas the results on its comprehensiveness and comprehensibility were inconsistent across studies (Table 2 and online Supplementary Table S3). For instance, some authors recommended the original MBI structure with three dimensions (Gold, Reference Gold1984; Gold et al., Reference Gold, Roth, Wright, Michael and Chen1992; Kim and Ji, Reference Kim and Ji2009) while others recommended a modified structure, limited to two dimensions (Kalliath and O'Driscoll, Reference Kalliath and O'Driscoll2000), or a four-item reduced original structure (Yadama and Drake, Reference Yadama and Drake1995). We also revealed the inconsistency in rating each item of MBI for frequency, for intensity, or for both. Based on these results, we downgraded the quality of evidence for content validity of MBI from doubtful to very low (online Supplementary Table S3). For BM and PBI, the quality of evidence on content validity was also very low, because their relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility were not validated using adequate analysis. For OLBI, we downgraded the quality of content validity to moderate/low due to the indirectness of its assessment, based on comparisons between extremely different groups. The CBI achieved the highest level of evidence for content validity, although the authors did not assess its comprehensiveness. According to the COSMIN, insufficient content validity could have been a stopping point for assessing the PROM validity. Nevertheless, we considered the seven other properties from the COSMIN checklist to enable meaningful and complete comparison of PROMs. For these properties, OLBI achieved the highest grade, with three validated psychometric properties (structural validity, internal consistency and construct validity), whereas CBI, BMI and BM completed two of them and PBI only assessed its structural validity (Table 2). It appears that the structural validity and the internal consistency are the most assessed psychometric properties, while the measurement error, the known-groups validity and the responsiveness were never assessed. It is noteworthy that the absence of an accepted diagnostic standard precluded measuring sensitivity and specificity of all OB PROMs (Table 1).

Table 2. Systematic review results for five burnout PROMs according to COSMIN

Note: ±, the psychometric property assessment was inconsistent; +, the psychometric property assessment was sufficient; −, the psychometric property assessment was insufficient.

Discussion

Main findings

For CBI, we found moderate quality of evidence on its content validity, internal consistency and construct validity, but very low quality of evidence of structural validity, reliability, measurement error, criterion validity and responsiveness. OLBI had a moderate to low quality of evidence for content validity, construct validity and structural validity and moderate quality of evidence for internal consistency. With this performance, OLBI had the highest number of psychometric properties assessed among the five reviewed PROMs. MBI, BM and PBI had a very low quality of evidence for content validity. Nevertheless, the psychometric properties of MBI were the most studied among the five PROMs and most of them were interpreted correctly.

Results' interpretation

Based on the evidence assessed by an objective multi-step approach, CBI appeared the most valid of the five reviewed PROMs, but essentially because of its content validity. Nevertheless, it is important to mention that CBI validation was completed by its authors in only one study, though a very comprehensive one. Most of their results were interpreted correctly; we found a slight over-interpretation regarding only one psychometric property (discriminant validity). CBI is the most recent PROM (2005), which can justify measuring more psychometric properties than the other, older PROMs. However, as it was originally developed in Danish, the overall evidence on its validity beyond the content validity is still insufficient to recommend CBI as the best OB PROM based on this review. As CBI was translated into different languages (e.g., English, German, French, Spanish, Chinese and Korean) and utilised in several countries, where it was judged as a robust PROM for OB (Milfont et al., Reference Milfont, Denny, Ameratunga, Robinson and Merry2008; Molinero Ruiz et al., Reference Molinero Ruiz, Basart Gomez-Quintero and Moncada Lluis2013; Fong et al., Reference Fong, Ho and Ng2014; Fiorilli et al., Reference Fiorilli, De Stasio, Benevene, Iezzi, Pepe and Albanese2015; Phuekphan et al., Reference Phuekphan, Aungsuroch, Yunibhand and Chan2016; Javanshir et al., Reference Javanshir, Dianat and Asghari-Jafarabadi2019; Jeon et al., Reference Jeon, You, Kim, Kim and Cho2019), the cross-cultural validity of the translated versions should be assessed.

OLBI was developed to tackle some drawbacks of MBI, especially the wording of the dimensions (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001; Halbesleben and Demerouti, Reference Halbesleben and Demerouti2005). According to our findings, OLBI is the second most valid available PROM of OB. This rating is due to the indirectness that downgraded the quality of evidence of its content validity but a larger number of psychometric properties assessed according to COSMIN checklist compared to CBI. Compared to CBI, OLBI's validation completeness was lower according to the methodological framework. However, we found no disagreement with the interpretation of its validation. OLBI overcame the limitations of MBI by balanced wording and broader conceptualisation of burnout, which is not restricted to human service's workers (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001; Halbesleben and Demerouti, Reference Halbesleben and Demerouti2005). MBI has negative wording for emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation and positive wording for personal accomplishment dimension, leading to a potential wording bias. Conversely, OLBI has both positive and negative worded items (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Vardakou and Kantas2003), is shorter than MBI and publically available in different languages. These features likely explain why OLBI is the second most used OB PROM after MBI (Guseva Canu et al., Reference Guseva Canu, Marca, Dell'oro, Balázs, Bergamaschi, Besse, Bianchi, Bislimovska, Bjelajac, Buggez, Busneag, Çağlayan, Cernițanu, Pereira, Hafner, Droz, Eglite, Godderis, Gündel, Hakanen, Iordache, Khireddine-Medouni, Kiran, Larese-Filon, Lazor-Blanchet, Légeron, Loney, Majery, Merisalu, Mehlum, Michaud, Mijakoski, Minov, Modenese, Molan, Van Der Molen, Nena, Nolimal, Otelea, Pletea, Pranjic, Rebergen, Reste, Schernhammer and Wahlen2020). BM is the oldest among the five PROMs reviewed in our study. Some studies reported that BM is reliable and valid (Pines and Aronson, Reference Pines and Aronson1988; Pines, Reference Pines1993; Schaufeli and Van Dierendonck, Reference Schaufeli and Van Dierendonck1993; Schaufeli and Enzmann, Reference Schaufeli and Enzmann1998). We found inadequate content validity with a very low quality of evidence of psychometric validity for BM as well as for PBI. The latter dates back to 1988 and the study that dealt with it was not focused on the psychometric analysis of the PROM but rather on its comparison with MBI (Ackerley et al., Reference Ackerley, Burnell, Holder and Kurdek1988).

As expected, MBI validity was studied more than for other PROMs, probably because MBI remains the most used OB PROM (Guseva Canu et al., Reference Guseva Canu, Marca, Dell'oro, Balázs, Bergamaschi, Besse, Bianchi, Bislimovska, Bjelajac, Buggez, Busneag, Çağlayan, Cernițanu, Pereira, Hafner, Droz, Eglite, Godderis, Gündel, Hakanen, Iordache, Khireddine-Medouni, Kiran, Larese-Filon, Lazor-Blanchet, Légeron, Loney, Majery, Merisalu, Mehlum, Michaud, Mijakoski, Minov, Modenese, Molan, Van Der Molen, Nena, Nolimal, Otelea, Pletea, Pranjic, Rebergen, Reste, Schernhammer and Wahlen2020). Some authors considered MBI as the gold standard for OB PROMs (Maslach et al., Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter1981; West et al., Reference West, Dyrbye, Satele, Sloan and Shanafelt2012; Williamson et al., Reference Williamson, Lank, Cheema, Hartman and Lovell2018), which can be debated provided the results of this review. The subsequent development of OLBI and CBI confirms the unsatisfactory features of MBI and the need of a diagnostic standard for OB (Arvidsson et al., Reference Arvidsson, Hakansson, Karlson, Bjork and Persson2016; Rotenstein et al., Reference Rotenstein, Torre, Ramos, Rosales, Guille, Sen and Mata2018). In MBI, emotional exhaustion is often considered separately, representing the core of burnout syndrome (Maslach and Jackson, Reference Maslach and Jackson1981; Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen2005) but also of depression or along with depersonalisation dimension to represent the core of burnout (Bussing and Glaser, Reference Bussing and Glaser2000). Some authors argue that depersonalisation and personal accomplishment are not even a part of OB (Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Borritz, Villadsen and Christensen2005). Concerning the overall psychometric validity, MBI has very low quality of evidence on validity for six psychometric properties out of eight although it had the highest number of validation studies.

It is worth noting that most PROMs were developed and assessed well before the methodological guidelines and frameworks for PROMs validation became available. This might partly explain the insufficient psychometric quality and validation completeness of the PROMs reviewed in this study.

Strength and limitation

This review assesses the evidence on psychometric validity of five commonly used PROMs. Besides its originality and topicality, this work has several methodological strengths, including the robustness of the research protocol, the exhaustiveness of the literature search, performed with assistance of an experienced documentarist using three important databases over a 40-year period. Every step of screening, data extraction, analysis and quality assessment was performed by two reviewers independently and double-checked by a third reviewer. For validity assessment, we used two complementary methods: our own methodological framework developed for validation of PROMs (Marca et al., Reference Marca, Paatz, Gyorkos, Cuneo, Bugge, Godderis, Bianchi and Guseva Canu2020) and the international standardised method (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Terwee, Patrick, Alonso, Stratford, Knol, Bouter and De Vet2010). The latter was completed with a modified-GRADE assessment after we started this study (Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Prinsen, Chiarotto, Westerman, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, De Vet and Mokkink2018). While the methodological framework allows assessing the completeness of validation and facilitates the objective results interpretation, the COSMIN is helpful in assessing content validity studies, the most important psychometric property of a PROM. Therefore, using these methods together enabled us analysing all aspects of qualitative and quantitative approaches used in PROMs validation thoroughly and providing methods triangulation.

The content validity is assessed based on the PROM's development study, which implies the use of original and not translated PROM version. Therefore, we did not consider studies using translated versions of selected PROMs. After the validation of the original version, the translated version should follow the process of cross-cultural validity assessment (Beaton et al., Reference Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin and Ferraz2000; Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Prinsen, Chiarotto, Westerman, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, De Vet and Mokkink2018). Correlations may differ according to countries and this emphasises the significance of cross-cultural validity (Pines et al., Reference Pines, Ben-Ari, Utasi and Larson2002). As our results suggest moderate quality of evidence of the content validity of CBI and OLBI, their cross-cultural validity assessment is highly recommended. It is noteworthy that four different French versions of OLBI currently co-exist (Belgian, French, Canadian and Swiss).

The small number of studies included in this review is a limitation, precluding firm conclusion on the quality of evidence of the reviewed PROMs. Considering a large timespan for the systematic literature search, allowed us observing that often PROM's validity results were published either as part of the PROM development study or shortly after. Therefore, the limitation of the systematic search 27/09/2018 should not be considered problematic, given that the last PROM was published in 2005. However, more methodologically robust validation studies are necessary for verifying results consistency and for the development of a diagnostic standard for OB.

Finally, as we only considered five OB PROMs cited as valid for assessing burnout in mental health professionals by O'Connor et al., some OB PROMs, such as Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (SMBM), remained beyond of our assessment. A recent study by Schilling et al. (Reference Schilling, Colledge, Brand, Ludyga and Gerber2019) concluded that SMBM validity and reliability were rarely examined in the literature. However, given the widespread use of SMBM, an assessment of its validity in future research is suitable.

Suggestions for future research in the field

Future research should further examine the psychometric properties that were insufficiently assessed or valid in CBI and OLBI, and assess all other available OB PROMs' validity. The development of a diagnostic standard for OB is a priority. It will facilitate OB PROMs comparison through the assessment of their sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy.

Conclusions

To be validly and reliably used in medical research and practice, PROMs should exhibit robust psychometric properties. Among the five PROMs that we reviewed (CBI, MBI, OLBI, BM and PBI), only CBI and, to a lesser extent, OLBI were able to meet this prerequisite. The cross-cultural validity of these PROMs was beyond the scope of our work and should be addressed in the future. Moreover, the development of a diagnostic standard for OB would be helpful to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the PROMs and further establish their validity.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020001134.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available online as supplemental material of the present article.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aline Sager, Christina Gyorkos and Paola Paatz for their precious help in establishing the search queries and screening.

Financial support

University of Lausanne and University of Bern BNF – National Qualification Program funded the salary of young researcher (SCM). European Cooperation in Science & Technology (COST Action CA16216), OMEGA-NET: Network on the Coordination and Harmonization of European Occupational Cohorts covered the meetings and travel expenses as well as the open access publication costs. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 801076, through the SSPH + Global PhD Fellowship Programme in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School of Public Health.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research is a systematic review of available studies and does not involve human and/or animal experimentation. The Ethics committee's approval was not required.