Introduction

There is an extensive historiography on socialist internationalism. The works of Georges Haupt, as well as of authors such as Michael Löwy, Madeleine Rebérioux, and Claudie Weill, constitute an indispensable point of reference in this regard. As Patrizia Dogliani has observed, many of the lines of research opened up by these pioneer scholars had still not been fully explored by the end of the 1980s.Footnote 1 Since then, and until the second decade of the present century, reflections on the nature of socialist internationalism have lost momentum, and much of the renewed historiography resulting from the shift towards cultural, linguistic, or gender considerations has not been followed up by an analysis of these topics. Hence, Dogliani has proposed, inter alia, to articulate the study of this field around major questions such as gender, class, race, sexuality, and varying identities, and, ultimately, has asked whether the socialist internationals were truly international in nature and spirit, or whether they were characterized by an attitude of national self-defence among each separate national working class.

In the past ten years, the profusion of new analyses of socialist internationalism has indicated a renewed level of interest in the subject and the continued existence of many unanswered questions. Nevertheless, the traditional dichotomy between international and national dimensions persists.Footnote 2 The prevailing concern about why, in 1914, the majority of workers followed the national flag instead of trying to stop the warFootnote 3 helped nourish those approaches. Both types of study have focused on institutional aspects, i.e. congresses and institutions; more conceptual analyses of socialist internationalism have tended to assume that this was largely a formal or rhetorical façade, always weak in the face of national realities, within the consolidated nation states in which socialism first made its way; some authors have even directly marginalized the nation, considering it exogenous to socialism. Furthermore, close attention to the traumatic events of World War I overshadows the importance of socialist internationalism beyond the war.

This article will analyse the role of internationalism in Spanish socialism during the Second Republic. Specifically, we will focus on the years 1931–1932, when socialism contributed to launching and consolidating the Republic's reformist and democratic project. In the first section, we study the meeting of the General Council of the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) in Madrid in April 1931 (Figure 1), and the May Day celebrations that followed shortly afterwards. The Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party – the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) – used these events to legitimize its political position in and highlight its integration within the new regime. Throughout, Spain's socialists ensured that the symbolism and narrative of class were combined and coexisted with the national imagery of Spain. In the second part of the article, we go further into this dynamic by examining the use the socialists made of internationalism in the debates on the new territorial structure of the republican state. Socialist internationalism was deployed to limit demands for decentralization, and the political and cultural recognition of non-state nationalisms. Thus, the positions of the PSOE contributed to reinforcing the status of the existing Spanish national structure as the natural state of affairs, the only legitimate sphere for international interactions, and to perpetuating a Castilian-centric definition of Spain in cultural and linguistic terms. In this way, our study demonstrates not only the deep identification of socialism with Spanish nationalism, and the nation's involvement with internationalism, but also the ethnic and cultural dimension of socialist Spanish nationalism.

Figure 1. Members of the PSOE and the IFTU at the Senate. El Socialista, 29 April 1931.

The ultimate goal is to enhance our understanding of the internationalism of socialism during the interwar period and of the nation's role. As explained below, we draw on the concept of “inter-nationalism” proposed by Kevin Callahan. Together with the cultural turn, it provides a fruitful tool to illuminate the operation of international socialist organizations, while also allowing us to examine the integration of socialists within the structures of the nation state,Footnote 4 and their relation to the nation as a political and cultural construct. Hence, this article maintains that internationalism was the socialists’ entry to the nation and nationalism by stretching, without breaking, the fundamental parameters of their political culture. However, the socialists did not avoid the cultural and ethnic dimensions of nationalism – a point often neglected by historians.Footnote 5

Inter-Nationalism: The Nation in the Socialist Internationalism during the Interwar Period

This article understands internationalism as a component of socialist political culture and identity.Footnote 6 As Talbot Imlay has indicated, it was an integral part of cultural repertoires and a practical dimension that fostered the socialist community.Footnote 7 Socialist internationalism was based on the principle of class solidarity, of sharing the anti-capitalist worker's struggle across national borders. That idea permeated socialist aspirations, narrative, and symbolism. At the same time, it was transferred to practices and became an element under constant construction, which could be adapted according to specific contexts. In many ways, socialist internationalism could approach other political tendencies, such as liberalism.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, it did not lose its aspiration to overcome the existing socio-political and economic framework, at least not before World War II.

In this regard, Callahan's concept of inter-nationalism indicates the extent to which the idea of proletarian internationalism supported by most socialists was rooted in the framework of the nation state, the coexistence – conflictive, but possible – of both elements in the mental schemas and practices of socialists, and the manner in which the nation acted as “the constitutive building block of any internationalism”.Footnote 9

Callahan coined this concept with the Marxist socialism of the Second International in mind. However, we consider its use for the interwar period entirely legitimate. The context had undoubtedly changed. Events such as the peace accords, the Soviet Revolution, and post-war socialist involvement in governments impacted socialist internationalism.Footnote 10 Nevertheless, it would be good to rethink the historical periodization and not exaggerate the ruptures: the continuities in imaginaries, protagonists, and problems were notable.Footnote 11 In any case, the war did not destroy socialist proletarian internationalism, which continued to be part of socialist political culture and identity, while the nation remained its building block.Footnote 12 During the interwar period, the socialist parties were involved in defining the true national interests. They took on the role of representing these interests in domestic policy and of harmonizing them in foreign policy. Everything points to the usefulness of the concept of inter-nationalism to understand socialist internationalism in the chronology after – and before – World War I.

When we employ this concept of inter-nationalism, the study of socialist internationalism better incorporates national variables. Throughout the nineteenth century and in the years of the First International, the internationalism of Marx was already one – one more – of the internationalist projects, which had at its base the activism of the working class at a national level and an ambiguous relationship with the nation.Footnote 13 The International took shape against the background of German and Italian unification, and political, social, and also national struggles that became part of the cultural references of its organizations.Footnote 14 Even the anarchist movement and its internationalism were not alien to the ideas of the nation.Footnote 15 Subsequently, after World War I, the socialist movement again advocated worker cooperation beyond the nation state, and inter-nationalist concepts were revived and maintained.Footnote 16 For these reasons, we defend the usefulness of the concept of inter-nationalism for the period after 1914.

Based on this analytical approach, we want to avoid methodological nationalism. Although important, one has to go beyond the sources for this purpose. The present article is based mainly on the socialist press from a single country.Footnote 17 El Socialista, the official newspaper of the PSOE, and Boletín de la Unión General de Trabajadores de España, the newsletter of its closely affiliated trade union Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) – and media affiliated with the IFTU through which news of socialist internationalism and trade unionism constantly reached Spain – are the main sources. In the second part of the article, we also use sources from the socialist PSOE press in Catalonia and the socialist Catalanist Party Unió Socialista de Catalunya (USC). Documentation from international socialist institutions and other countries – specific editions of the French socialist press have been consulted – contribute to overcoming historiographical nationalism. Nevertheless, following Stefan Berger, to combat the national(ist) paradigm it is paramount to develop a reflective history capable of examining the historicity of national identity to overcome essentialist views.Footnote 18

Hence, the desire to decentre the nation as the focus of our study has to be understood as a further contribution to the interrogation of the national phenomenon, to acknowledging its problematic nature and to questioning its natural status, and as an attempt to analyse the ways in which different actors participated in the social construction of the nation.Footnote 19 This effort goes hand in hand with historiographical trends such as comparative and transnational history,Footnote 20 increasingly called on to play a prominent role in the study of the nation, internationalism, and socialism.Footnote 21 In addition, we explore the socialist discourses contained in the press, because we start from the idea of discourse as a social practice, which was a key element in the historical construction of national and class identities.Footnote 22 Apart from focusing on the discourses contained in the press, we adopt a broader view on discourse, exploring also rituals and practices such as musical performances. Such an approach enables us to analyse identity beyond its explicit expression in political statements; it can also include other aspects of socialist organization, such as sociability, leisure, and everyday life. These remain fields to be fully exploited to analyse what these aspects can tell us about the construction of social, political, regional, and gender identities.

Internationalism in Spain: The IFTU and May Day

To demonstrate the potential of the proposed approach, we will first examine the meeting of the IFTU held in Spain in April 1931, and the subsequent celebrations on May Day.Footnote 23 Both these events and traditions were characteristic of socialist internationalism.

At that time, the Second Republic had just been founded. The revolutionary path failed in December 1930, but a coalition of republicans and socialists won the municipal elections of April 1931. As a result, Alfonso XIII fled the country, and the coalition's parties formed a provisional government. The goal was to build a republic similar to the modern democracies established immediately after World War I. Throughout the republican period, the difficulties encountered by the project were multiple, fundamentally internal, but linked to a no less complicated context of the economic crisis and the rise of fascism in Europe.Footnote 24

The PSOE arrived at those moments after breaking with the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923–1930) and with a renewed tactical orientation: it not only broke with class isolation but accepted coalition government with republicanism. Thus, the Socialist Party opted for a strategy of gradual progress towards socialism. The legislative elections of mid-1931 confirmed Spanish socialism as a mass party and a pillar of the democratic republic; the party also played a role in government, taking three ministerial posts. Eventually, this position was maintained in the party congresses of July 1931 and October 1932. Nonetheless, as early as 1931 the strategy of alliances and participation in republican government had provoked the resignation of some party executive members even before the fall of the monarchy. Between 1932 and 1933, with complications in the approval and application of social and labour measures favourable to workers, more groups supported abandoning the coalition.Footnote 25 The Republican-socialist government coalition was eventually dissolved in 1933, and the elections of that year gave way to the formation of right-wing governments. The PSOE did not return to coalition government with republicanism until the anti-fascist pact of the Popular Front of 1936, in a context different from that at the start of the decade. Not unconventionally, during those years the PSOE had to confront the tensions and debates typical of socialist movements in the interwar period.Footnote 26

Regarding the PSOE's position in 1931, the concept and practice of internationalism were significant, as the following analysis shows. During the election campaign of April 1931, Francisco Largo Caballero, one of the party's principal leaders, had already declared that socialist opposition to the monarchy had a dual aspect, international and national. Spain would contribute to the cause of pacifism and to holding back the global march of fascism by overthrowing its authoritarian monarchy, and, he claimed, the international socialist movement was also waiting for the success of Spanish republicanism in order to proclaim the end of fascism and reaction. Largo thus found in the international struggle against fascism and workers’ internationalism points of reference that justified the PSOE's alliance with republicans. It is worth noting that in Spain Léon Jouhaux had suggested a similar argument at the beginning of the year.Footnote 27

According to Largo Caballero, Spain's allegiance to the international fraternity would principally affect its relations with Hispanic America. However, this hispanoamericanismo was not related to working-class internationalism as much as to Spanish-nationalist projects and discourses.Footnote 28 Equally, Largo also stressed that in that moment the only things that truly mattered were the interests of the country, and that socialism should show itself to be patriotic. This was in no way contradictory, because “we love the homeland”, and the progress of the working class demanded that of the nation itself.Footnote 29

These words indicate a resort to the international arena as domestic self-justification, and demonstrate the influence of the inter-nationalist formula prior to the arrival of the republican-socialist coalition in power. Patriotism and the nation were assumed to be indispensable requirements for the defence of the workers’ cause within one's own country and beyond. Proletarian internationalism was intermixed with the socialists’ identification with patriotism, and linked to the political and cultural aspirations of Spanish nationalism.

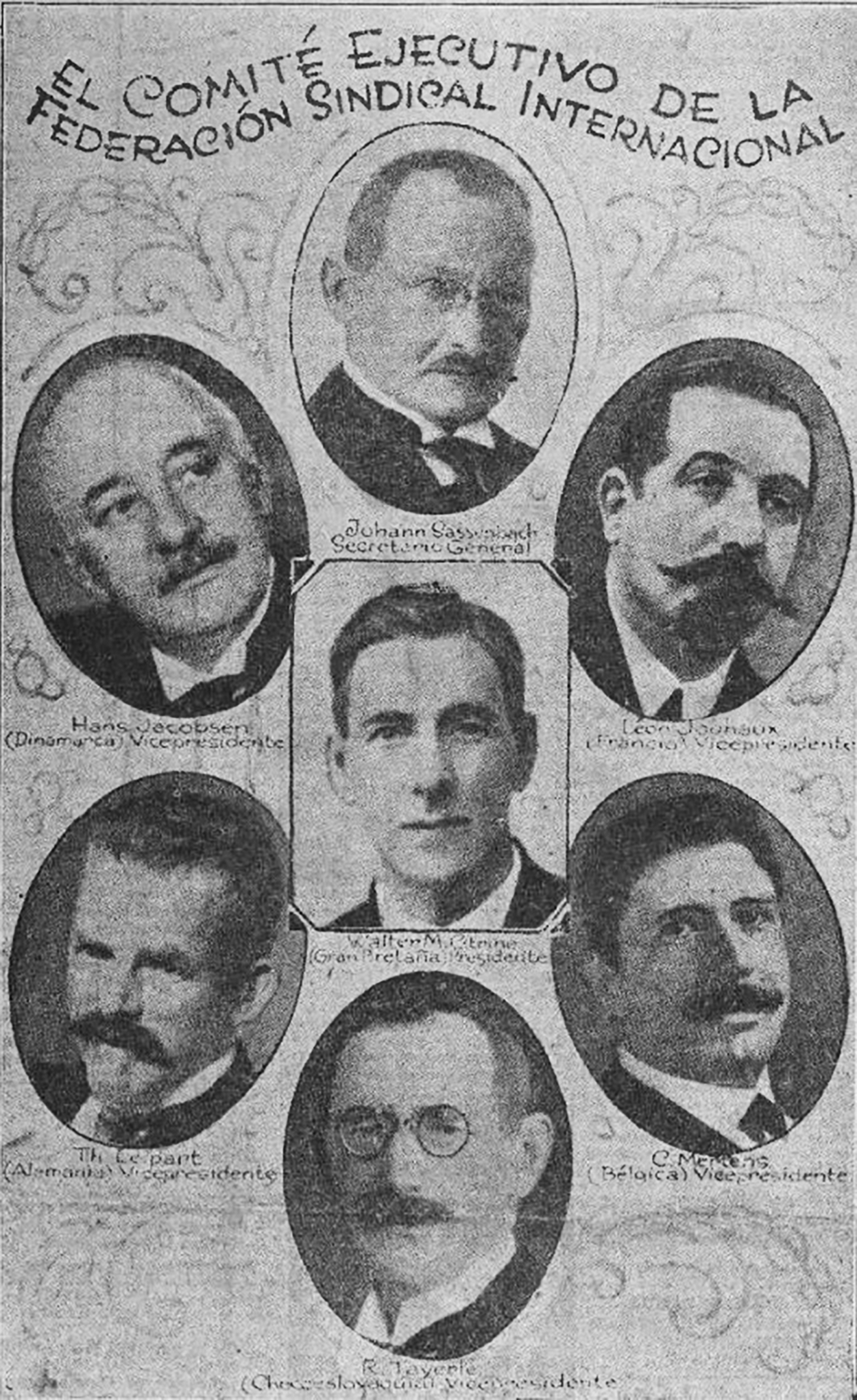

Once the Republic had been proclaimed, on 14 April 1931, these ideas and images proliferated still further, as could be seen during the meeting of the IFTU Council held in Madrid barely two weeks later. The Council's visit was a major event for Spanish socialism, and over several days the party's and trade union's newspapers published the agenda and accounts of the meetings and special events, descriptions of the structure of the Federation, and photographs of the delegates. On 26 April, El Socialista reported on the arrival of leading IFTU figures (Figure 2), and Enrique Santiago, a member of the UGT executive and a prominent socialist, welcomed them. He acknowledged the movement's pride in having overthrown the monarchist regime. Nevertheless, he observed, it would retain a spirit of modesty, and with this the need for, and the need to merit, international solidarity to achieve its ultimate objectives. Santiago explained that the cry of “Viva España!” joined in by the UGT and the PSOE during the proclamation of the Republic would not degenerate into a “morbid nationalism, incompatible with peace and civilization”, since they were sons of the International and would remain faithful to it.Footnote 30 The UGT newspaper deployed the same idea but more intensively. The shouts of “Viva España!” had made it possible to end Alfonso XIII's “foreign race”, but they were not to be replaced by “unfriendly nationalism”. The trade unionists considered themselves internationalists and, therefore, wished the members of the IFTU a pleasant stay in Spain, a country “more international than ever”.Footnote 31

Figure 2. Faces of IFTU leaders published on the front page of El Socialista, 26 April 1931.

This mixture of ideological censure of nationalism and an affirmation of solidarity and fidelity to internationalism with a certain nationalist bragging over the political change that had taken place in Spain permeated many of the pronouncements of the Spanish socialists. The PSOE's leaders sought to harmonize the national and international arenas in accordance with inter-nationalism, and thus generate support within and outside the party.

During these days, Largo and Indalecio Prieto – then both socialist leaders supporting the government coalition as ministers of labour and finance, respectively – underlined that the socialist presence in government guaranteed its alignment with international labour legislation and with pacifism. This connected with the words of the President of the IFTU, Walter Citrine. According to El Socialista, Citrine warned that the Spanish Republic had taken only its first steps, so that the immediate priority was to consolidate it, and only later decide which path each of the parties in the republican-socialist coalition should take. These statements pointed in the same direction as the arguments used by Largo and Prieto in the debate on participation in government. It thus seemed clear that the forces of socialist internationalism approved the PSOE's commitment to the new regime. It was believed that this would contribute to the national regeneration of Spain, without risking international workers’ solidarity and the campaign for pacifism.

Similar ideas were expressed in the IFTU Council meeting by Manuel Cordero and the eminent socialist intellectual Julián Besteiro. Speaking as a representative of the UGT, Cordero described the feelings of fraternity the Spanish proletariat felt for those beyond their borders, and proposed that the Spanish socialists could act as intermediaries for the Labour and Socialist International (LSI) in the Americas. Even if some IFTU leaders could grant Spain that intermediary role,Footnote 32 in this case, again, internationalism slid into forms of solidarity derived from a particular interpretation of Spanish national identity. Besteiro was betting on socialists leaving the government and consolidating the Republic from the outside. But he insisted on the idea that:

[…] the Spanish revolution is not just a page in the history of Spain, but in the history of Europe, because it advances the future of the working classes and of Socialism […] In the work of defending this Republic we will elevate spiritually the working masses of Spain, for we will thereby achieve a task that is not just national, but international.Footnote 33

In accordance with an inter-nationalist conception, therefore, the workers’ struggle would be developed within, and from, the national arena. The defence of the Spanish Republic and the improved situation of the working masses in Spain represented an undertaking both national and international. Hence, the PSOE's commitment to the nation was different from simple nationalism, and compatible with internationalism.

In addition, the Spanish socialists insisted on the pacifism of the Republic and the absence of any imperialist pretensions. That insistence makes sense given the concern of socialist internationalism with peace and disarmament policies since the 1920s.Footnote 34 Besteiro rejected imperialism and reaffirmed the Socialist International's endorsement of pacifism, while Prieto announced a reduction in the size of the Spanish army. At the same time, however, he also asserted the right of Spain to demand respect for the new political project being pursued within its borders. This defence of the Republic was accepted and, according to El Socialista, acknowledged by Émile Vandervelde, President of the LSI, who committed the LSI and the IFTU to its support.Footnote 35 Ultimately, these arguments were associated with the idea of national defence, which had been accepted in the Marxist tradition and which, even given all the problems it gave rise to, had coexisted alongside anti-militarism and pacifism before World War I.Footnote 36

Beyond the speeches and statements, the events organized around the Council meeting were also significant (Figure 3). Among other attractions, the Spanish socialists presented a musical gala in honour of international socialism in Madrid's Teatro Español.Footnote 37 The programme consisted essentially of pieces that had been popular in Spain and were associated with Spanish national identity. The city's Banda Municipal or municipal orchestra performed selections from zarzuelas, the traditional Spanish light operas, by celebrated composers of the previous century such as Tomás Bretón and Ruperto Chapí. Both had contributed to popularizing the zarzuela as a Spanish national alternative to opera and lieder, and had thereby won a special place in Spain's musical pantheon. Often featuring historical events, and evoking traditional regional customs, the zarzuelas “were ways in which countries could be unified conceptually to form a new national imagined community”.Footnote 38 As in Italy and France, this deployment of the region in musical form represented an evocation of folklore that was understood to be entirely national, without any intention of asserting any particularist identity for the region itself.Footnote 39

Figure 3. The executive committee of the IFTU at the Pablo Iglesias Memorial in the cemetery of Madrid. Boletín de la Unión General de Trabajadores de España, June 1931.

This last point can also explain the presence of the regions in the subsequent performances of the Socialist Choirs, and of other regional groups from around Spain. All performed regional music and dances, with pieces very well-known in Spain, that for the international audience acted as portraits of different parts of the Spanish nation.

The concert returned to more orchestral music with a fragment from Bizet's Carmen, a zarzuela inspired by Aragonese traditional music, and two songs by Ricardo Villa and Manuel de Falla, the latter with a distinctly Andaluz tone.Footnote 40 Again, the use of musical pieces and composers well-known in Spain and abroad as fitting representatives of Spanish national identity is particularly noticeable. The evening concluded with the Socialist Choirs performing the Internationale.

The concert thus consisted of a continual evocation of the Spanish nation, in line with the dominant currents of musical nationalism and Spanish national mass culture. Various socialist musical ensembles were also directly involved in the performance. This was probably a deliberate decision, for El Socialista rated the concert very highly, assuring its readers that the event would definitely “leave a fond memory […] among the foreign comrades, who had the opportunity to appreciate some expressions of our regional arts without the mystifications with which they are commonly presented abroad”.Footnote 41 The symbolism of workerism – red flags, anthems – was present, but the Spanish socialists wished to fraternize with their European comrades through a display of national imagery.

Although it had not formed part of the programme, the Himno de Riego was sung, a song that had originated in the revolutionary Spanish liberalism of the early nineteenth century, which became established as Spain's national anthem under the Second Republic. Previously, the singing of the anthem had also formed a central part of other events such as the reception given for the IFTU delegates in Madrid's City Hall. On these occasions the singing of the Marseillaise and the Internationale had accompanied the Spanish anthem.Footnote 42 This combination of national and revolutionary symbols well illustrates the internationalist style of the events. Spanish and other European socialists could perceive each piece of music in a different way, and also respond with special emotion to particular melodies such as the Internationale. According to press reports, German, Belgian, British, French, and Spanish socialists all sang together, with “an emotion of sincere fraternity”.Footnote 43 That said, the words of the Internationale varied from country to country – and sometimes even within each country – so that even this experience of cross-frontier working-class unity could be filtered through the nation.Footnote 44

Overall, the PSOE made use of the meeting of the IFTU Council to legitimize the Second Republic and validate its own participation in government. The consolidation of the new regime appeared as a necessary and worthwhile task that would represent progress towards a socialist future and slow the advance of reactionism and fascism in Spain and internationally. Consequently, for the PSOE the meeting served to reinforce and give greater legitimacy both to its collaboration in government and to the socialists’ identification with Spanish patriotism, which gives us one indication of the socio-political importance accorded to the nation in socialist internationalism. Furthermore, this was not at all contradictory, for the development of organizations and tendencies that apparently offered alternatives to or were even opposed to the nation state could also reinforce the political and cultural frameworks of the latter.Footnote 45

In this respect, this internationalist gathering served to display a whole range of elements of Spanish national identity. Reflecting, once again, an inter-nationalist approach, the symbolism and discourse of the events frequently referred to the Spanish national imaginary, both in music and in more or less banal aspects.Footnote 46 This dynamic had already been appreciable in earlier socialist meetings, such as the London Congress of 1896.Footnote 47 It reinforces the argument of the continuity of internationalist practice and conception before and after World War I. If the leaders of the PSOE repeatedly insisted on their desire to disassociate themselves from nationalist ideology, and distance the Republic from any aggressive pretensions, they also clearly intended to demonstrate to their European colleagues the particular national qualities of Spain, its political ambitions, and its culture. A shared notion of inter-nationalism left room precisely for the national dimension.

For the May Day celebrations, which came immediately after the Council meeting, the main Spanish socialist press published the manifestos issued by the IFTU and the LSI to mark the date. Both urged all sides to combat the effects of the economic crisis upon workers, to further the cause of pacifism, and to defend democracy against fascist tendencies.Footnote 48 The leaderships of the PSOE and UGT called upon socialist organizations throughout Spain to hold demonstrations, meetings, artistic performances, and so on. They also explicitly endorsed the demands set out by international organizations, presenting petitions to the government calling for measures to confront unemployment, and improve wages and working conditions. At the same time, the Spanish socialists also stressed their support for the new republican government, with the eventual aim of endowing it with revolutionary content.Footnote 49 The struggle of the working class proclaimed by the international institutions, it was suggested, was given concrete form within the Spanish republican nation state, the defence and leadership of which should be headed by the socialist movement.

Similarly, the Socialist Youth, the Juventudes Socialistas de España (JJSS), also placed national and patriotic considerations centre stage. Their newspaper, Renovación, carried the manifesto issued by the International Union of Socialist Youth, which, in accordance with the IFTU and the LSI, but with a greater accent on anti-fascism as a motivation for struggle, proposed peace between peoples, democracy, and socialism as May Day slogans.Footnote 50 However, the JJSS also specified the demands they made upon the new republican regime, and called for a complete programme for the social and political transformation of Spain, including better provision for training and social welfare, especially for young workers. In sustaining these claims the JJSS noticeably presented themselves in national, and not just social or international, terms, since they argued that working-class youth had to form the future “Spanish race”, and said they demanded these measures because of “our patriotic sentiment”.Footnote 51

Aside from the internationalist content of the different manifestos, the events in Madrid took place amid a festive atmosphere sparked by the recent proclamation of the Republic.Footnote 52 The new government had declared May Day a national holiday, which helped strengthen the feeling that the workers had succeeded, reinforcing the republican and socialist coalition and further fostering a sense of identity between governors and governed.Footnote 53 At the same time, following a socialist initiative, the government was preparing to ratify measures such as the eight-hour working day contemplated in the Washington Conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO).Footnote 54 The permanent contacts between Largo Caballero, his collaborators, and Albert Thomas were important in the decision to quickly adopt international legislation, which, in addition, could help further the international consolidation of the new regime, as well as that of the UGT at the national level.Footnote 55

In accordance with the socialists’ idea of proletarian education – in contrast to the tumultuousness of communists and anarchists – the PSOE press highlighted the order and tranquillity with which the day's events had taken place. Moreover, according to El Socialista, this demonstrated that “Spain […] has come of age, and can now aspire to be included among the truly European nations”. The socialists proudly claimed a leading role for themselves in the country's legitimate entry into the orbit of modern civilization, a route to national regeneration that Spanish nationalism had been calling for for decades.Footnote 56 Spanish socialism thus paraded its patriotism and love of the fatherland in the midst of internationalist celebration.

Leading figures in international social democracy such as Edo Fimmen, Jouhaux, and Vandervelde prolonged their stay in Spain after the Council meeting to take part in the celebrations. At the microphones of Unión Radio they were joined by Largo Caballero and Besteiro, who explained the universal significance of May Day, as a demonstration of solidarity and proletarian unity, and its special meaning in a Republican Spain that had been conquered by the working class. The radio station also broadcast several hours of music performed by socialist choirs and orchestras and the municipal orchestra. Once again, the greater part of the programme consisted of música española, compositions by the musicians who had created the Spanish national canon through which a folkloric and regionalized evocation of Spain was recreated and repeated.Footnote 57

The Internationale, the speeches, and the presence of European socialist leaders strengthened the idea of international working-class identity and fraternity. Nevertheless, the popular repertoire of Spanish musical nationalism took pride of place in this celebration of the international socialist workers’ movement. The repetition of this dynamic throughout Spanish territory reminds us of the links between the socialist movement and the nationalized mass cultures of the time.Footnote 58 The rituals of socialist political culture, though shared beyond national frontiers, were performed in contact with modern national mass culture, and made their own contribution to the dissemination and homogenization of the latter throughout the national community.Footnote 59

Five years before France, Spanish socialism enjoyed its own tricolour May Day, imbued with national narratives and symbols, without abandoning internationalism and workerism.Footnote 60 Calls were made to honour “the fatherland that saw our birth, Mother Spain”, through the workers’ festival.Footnote 61 The PSOE demonstrated its identification with the Republican state, since it considered that this represented the liberation, and the embodiment, of the true Spain, and, moreover, a step forward for international socialism. Socialist patriotism was nourished by the conceptions of inter-nationalism, which permitted the acceptance of the nation, understood as one – the foremost, and one's own – part of humanity.

The Internationalism in Inward Action

The PSOE had no doubt that its nation was Spain, and that this identification was consistent with its doctrine. As El Socialista explained, when Marx said that working men have no country he was referring to situations in which there was neither freedom nor basic rights; therefore, he had not denied the idea of the nation as such. In Spain, the proclamation of the Republic had brought the “reconquest of the fatherland” for the Spanish people and proletariat, which gave a new validity to love of country.Footnote 62

This identification with Spanish patriotism, formulated from within the parameters of inter-nationalism and based upon an assumption that the interests of the nation and those of workers coincided, was a constant in the PSOE.Footnote 63 Locating the proletariat at the core of the definition of the nation characterized this kind of social patriotism, which was shared by most European socialists, irrespective of the greater or lesser radicalism of its branches.Footnote 64

On this point, the cultural implications of socialist identification with the nation tend to remain unexplored, and socialism has often been associated with purely civic, democratic, and voluntarist notions of the nation.Footnote 65 However, socialist inter-nationalist patriotism did not exclude the ethnic and cultural dimensions of nationalism – nor even its most exclusionary outcomes.Footnote 66 These dimensions of nationalism were present during the reorganization of the nation state attempted by the Second Republic, a central issue in its functioning. The next section will analyse the use of proletarian internationalism in that process. Then, the PSOE conversion of internationalism into a mechanism for denouncing the nationalism “of the others” and normalizing its positions leads us to the political and also cultural implications of the socialist inter-nationalism construction.

The republican-socialist coalition, which took power in April 1931, rejected the traditional centralist structure of the Spanish monarchist state. However, it had not reached any agreement on an alternative arrangement, nor did the different elements in the coalition share any specific model.Footnote 67 Faced with this situation, the nationalists of Catalonia, the Basque Country, and Galicia took the lead in demanding decentralization and political and cultural recognition. During the first biennium (1931–1933), with the support of the PSOE, the Constitution of December 1931 rejected federalism but approved a way of decentralization through regional autonomy statutes. In September 1932, the Constituent Parliament approved the Catalan Statute of Autonomy – the only one before the Civil War. From November 1933, the conservative turn in the Spanish government cooled the processes of autonomous decentralization. Among other things, the processing of a statute for the Basque Country was slowed down. Above all, the repression of October 1934 triggered the suspension of the autonomous government and the statute in Catalonia. Later, the Popular Front's victory in February 1936 contributed to reopening the debates and a resumption of the path to autonomism.Footnote 68 We will focus here on the period 1931–1932, when the different positions were taking shape and autonomism was debated, in the streets and in parliament, in relation to issues such as the official language of Spain, the decentralization of the state, and the education system. We consider in particular the case of Catalonia, since this brought together both general positions, i.e. the socialists’ opposition to Catalanism, and more particular considerations, i.e. their confrontation with another socialist party.

The PSOE blocked federalist proposals, but remained open to regional decentralization. However, all consideration of such issues was made conditional on the expected leftist political orientation of the hypothetical autonomous territories. Significantly, from the ILO, Thomas advised the PSOE not to risk the ratification of international labour treaties with the concession of a decentralized regime.Footnote 69 Nevertheless, the socialist position depended on issues beyond political orientation and international social and labour policies. The socialists’ avowed objective was the maintenance of the “Spanish soul”,Footnote 70 that is to say, for the socialists the primary concepts of political orientation and overriding national unity, together with the characteristics associated with the notion of Spanish-ness, could not be questioned. This position was officially defined in the party's Extraordinary Congress of July 1931.

As an internationalist movement, the PSOE declared itself in favour of recognizing regional autonomy, subject to its popular endorsement.Footnote 71 However, although internationalism was used here to justify this flexible posture, it was primarily employed in the contrary direction. The PSOE brandished its “purely internationalist ideals” to condemn one nationalism – Catalan – as a “medieval, anti-modern chimera”, but did not question the existing national fabric of Spain, nor the need to defend it.Footnote 72 According to the Basque future editor of El Socialista Julián Zugazagoitia, the question of the minority nationalities was “a burden of things from the past”, and Catalanism a profoundly conservative, bourgeois movement, which consequently had nothing to do with a proletarian internationalism that “rejects the possibility of new frontiers”.Footnote 73

For its part, at the beginning of August 1931, the Catalan Socialist Federation (FSC) of the PSOE had called for a yes vote in the imminent plebiscite on a draft proposal for a Catalan Statute of Autonomy. However, its aim in doing so was to settle a “non-existent” problem, do away with “dangerous sentimentalisms”, and assist the growth of the Socialist Party.Footnote 74 Once the referendum had concluded with massive support for autonomy, the subsequent FSC congress predicted the decline of Catalanism and an upsurge in support for the socialists, who would lead workers and the region towards internationalism.Footnote 75

Internationalism was thus used to express an ideological opposition between (non-Spanish) nationalism and socialism. This was repeatedly demonstrated by Antoni Fabra Ribas, a Catalan socialist with a long career in the international movement.Footnote 76 During the seventh Congress of the Catalan Section of the UGT in 1931, he argued that Catalan nationalism had invented, and exploited, the idea of a differentiated Catalan personality. The socialists had to promote European solidarity and European federation, Fabra Ribas went on, but never permit any threat to the unity of Spain.Footnote 77 While they might not adopt a set position of opposition to or collaboration with the Catalan autonomous government and its institutions, they could not remain indifferent to any attempt to establish “ideas of difference between our working class and that in the rest of Spain”.Footnote 78 Hence, in 1932, he reiterated his adherence to Spanish working-class solidarity and a desire to federate Spain with the world, while also rejecting any autonomy statute that could fracture the unity of Spain.Footnote 79

Working-class identity and solidarity were to be deployed within (and from within) the existing national fabric of Spain, as the only legitimate sphere for socialist internationalism, while alternative identities complicated matters. Hence, when the Catalan Statute was definitively endorsed, the PSOE celebrated bluntly that, in its view, there was no cession of sovereignty and no surrender of “even a fragment of the nation” to Catalanism.Footnote 80 Again, the PSOE flaunted a deep and natural identification with the Spanish national framework, a banal nationalism that made its nationalist position invisible.

Throughout these debates, until the approval of the Catalan Statute in September 1932, as well as confronting the forces of Catalan nationalism the PSOE also confronted a separate socialist party in Catalonia, the USC.Footnote 81 Formed by a combination of a split from the PSOE and various groups of left-wing Catalanists in 1923, the USC denied being part of Catalan nationalism as such and described itself as the Catalan branch of universal socialism, with the formula, “We are not nationalists. We are Catalans, and therefore Catalan socialists”.Footnote 82 To establish their legitimacy, and challenge the PSOE in terms of its own points of reference, the leaders of the USC based their principles on interpretations put forward by Jaurès, Karl Renner, Arturo Labriola, Engels, and even Marx, all of whom had professed the compatibility between the idea of a homeland and socialism.Footnote 83 As Manuel Serra i Moret, one of the USC's leading figures, explained in an introduction to a Catalan edition of the Communist Manifesto published in 1930, Marx had stated that the proletariat had no country in conditions of oppression, but that it would be legitimate for them to aspire to possess one. Hence, with an argument identical to that used by the PSOE with reference to Spain, the USC maintained it still adhered to Marxism in its patriotic attachment to “our mother Catalonia”.Footnote 84

The USC embraced Catalonia as a nation through which to attain socialism and contribute to universal brotherhood, but, on the basis of internationalism, it also rejected nationalism in doctrinal terms. As Rafael Campalans, one of its principal intellectuals, put it, Catalonia was their homeland, within which they would build socialist emancipation, and so the place from which they could become universal.Footnote 85

The PSOE and USC thus shared inter-nationalist ideas, but this led them further into confrontation. For the USC the PSOE was blinded by Spanish centralism. Marxist orthodoxy, they maintained, required that the ethnic and economic differences between Spain and Catalonia should lead to distinct expressions of socialism. With theoretical support from Jaurès, they called for a Catalan socialism that would work towards human reconciliation from Catalonia, as a distinct nation that would maintain its “profound historical originality”.Footnote 86

The PSOE saw its monopoly as representative of the working class threatened, in Spain and in the socialist international organizations, whose functioning was based on the existence of one party per nation. With the constitutional debates in the background, the PSOE and the UGT strove to show the militants that only they could defend the proletariat in line with the principles of the socialist and union internationals. Socialism and Catalanism were mutually exclusive, it was argued, because “nationalism and socialism are antithetical, incompatible”, and to suggest anything else would lead to German national socialism.Footnote 87 Class internationalism made it difficult “to defend the reconstitution [as a state] of the nationalities that had lost their political form in the course of history”. Therefore, the Catalanist socialism of the USC did not align within the correct approach taken by proletarian internationalism, evoked Hitlerian formulas, and threatened the unity of the Spanish nation state, which would be “manifestly detrimental to the working class”.Footnote 88

Both parties followed identical inter-nationalist lines of argument. Catalan socialists may have been more aware than the PSOE of Austromarxism, and the debates that had unfolded before 1914. This would be the case with Campalans. However, he never mentioned Otto Bauer or Renner as he did Jaurès, for instance.Footnote 89 In the PSOE, the writings of Austromarxists were barely referenced and, without a doubt, they did not represent any benchmark during the Second Republic.Footnote 90 The confrontation between the PSOE and USC was far from being considered in terms of Bauer and Renner. It stemmed from identical inter-nationalist proposals, but with allegiance to different national identities, not from different ways of understanding internationalism or the national phenomenon. Despite everything, many of the dynamics of these confrontations between inter-nationalist socialist patriotisms had already occurred within the Austrian Social Democratic Party, between Austrian and Czech socialists.Footnote 91

These disputes energized the cultural aspects of the identification between nation and socialism, in a manner that connects with the trends referred to above. By evoking internationalism, the PSOE combatted not only the demands of alternative nationalisms for a potential recasting of Spain's political unity, but also any questioning of the centrality of the cultural symbols of Castile in the Spanish national imaginary, whether linguistically or historically.

Fabra Ribas argued that the Catalan language was “not the most appropriate medium for fostering [class] solidarity”. Catalan workers, he argued, had always freely chosen Castilian Spanish in their organizations, and this was the language that helped them work and fraternize in Hispanic America.Footnote 92 In this respect, the Spanish socialists pressed for Spanish to be accepted as an official language in international institutions such as the ILO, and Fabra Ribas served as a correspondent for Spain, Portugal, and Ibero-America in the ILO Office in Madrid, from where he communicated about the organization's activities in Spanish.Footnote 93 However, beyond these utilitarian considerations, the PSOE also upheld the status of Castilian for nationalistic motives, because, the party's representatives argued, to each nation there corresponded a single language, and Castilian constituted the Spanish national language. In the Constituent Parliament of the Republic, socialist deputies justified this view out of “love for Spain”, and a need to sustain the country's “spiritual unity”.Footnote 94 Following those cultural conceptions of the nation, the Spanish language was also defended in the international arena as a defining feature of the spiritual community between Spain and its American ex-colonies, as it was for example by Largo Caballero at the fifteenth Conference of the ILO in Geneva in September 1931.Footnote 95

In contrast, it was common among the organizations associated with the PSOE to consider the Catalan, Basque, and Galician languages as leftovers from the past, destined to disappear in the face of Castilian Spanish, associated with the essence of Spain. Hence, in response to requests for the incorporation of Catalan into the educational system, several socialist unions declared their opposition, as a defence of civilization and the aspiration to a universal language.Footnote 96 Similarly, in Barcelona the Socialist Youth undertook a campaign for teaching to be in “the national language (Spanish), in the name of the socialist doctrines of universal fraternity”.Footnote 97 One can infer from this that Castilian Spanish, as the Spanish national language, did not pose any threat to the values and goals of internationalism. In effect, the Menorcan socialist Santiago Petrus emphasized that teaching in Catalan would be damaging for working-class internationalism, whereas teaching in Spanish would foster working-class unity, as well as “national unity” and the “bonds between regions”.Footnote 98

The whole body of non-Castilian languages was considered to be bound up with traditionalism, “devoid of ideological value, of mediocre cultural value, and [with an] insignificant literary tradition”.Footnote 99 They could be useful at the most for lesser, regional, cultural forms, and were associated with “small-minded nationalisms” inconsistent with modernity or, still worse, positions close to fascism.Footnote 100

These positions in favour of the language of the nation state were already habitual in European socialism, and could have reached the PSOE from various sources. In the first place, however, a primary role was played by the influence of Spanish nationalism itself, and its long-standing effort to raise the prestige of the Spanish language and literature associated with the nation state.Footnote 101 Secondly, readings and the transmission of doctrines from other socialist movements also contributed. In this regard Jaurès, who was repeatedly cited as an authority, had conditioned the teaching of languages such as Basque and Occitan in France to measures to ensure a proper knowledge of French, seen as superior and a language of access to civilization.Footnote 102 The bulk of French socialists, a model and source of ideas for the PSOE, adopted the same stance, so that, in their shifts of focus from the universal to the particular, France as a whole represented the only legitimate political and cultural platform.Footnote 103 In addition, Marx and Engels had asserted the general tendency of minor nations and languages to disappear and frequently dismissed the claims of non-state nationalisms, and their ideas filtered into other Marxists.Footnote 104 Kautsky took them up, and his writings were widely translated into English, Italian, Russian, and Spanish. In Britain and in continental Europe this resulted in a range of ethnic and linguistic tensions.Footnote 105

Among Spanish socialists, proletarian internationalism was used to maintain the Castilian Spanish language. However, the national status that the PSOE attributed to Castilian stemmed from the party's acceptance and repetition of the dominant Spanish nationalist imaginary, and specifically the idea of the predominant role of Castile within its conception of Spain, and not from any internationalist Marxist precept. According to those essentialist notions, for the PSOE, as a nation, “The language of Spain is Castilian. Castile was the axis of the state, and continues to be so”.Footnote 106 As the party general secretary, the Aragonese Manuel Albar, put it, Castile “has always been the core of Spain”.Footnote 107 This historical role became near-mystical in the words of the socialist Justice Minister Fernando de los Ríos, who declared in the Constituent Parliament that Castile symbolized “the Spanish political genius, and I do not believe that there is in all Spain anything more than the political genius of Castile”.Footnote 108 Only in the lands of Castile could one find the essential and lasting elements of the Spanish being.Footnote 109

Spanish-nationalist Castilian-centrism was thus intermixed with the central conceptions of the PSOE. In 1932, the party's congress was attended by the Italian socialist Giuseppe Modigliani, representing the LSI. In his speech to the congress, he stressed that Spain's example demonstrated to the workers of the world the importance of gradualism and democracy, and so urged the PSOE to maintain its policy of strengthening the Republic. In reply, De los Ríos said that, in contrast to Italy, Spain had not allowed itself to be dragged along by subversive maximalism, because “Spain, Comrade Modigliani, has the good fortune to have Castile […] and it is Castile that has made socialists of all of us, and in turn Madrid that has made socialists of all Spain”.Footnote 110

Conclusion

The question this article has tried to address is whether internationalism, as a practice and principle embedded in socialist political culture, alienated socialists from the nation. According to this study, it does not seem so. On the contrary, our study emphasizes the significance of understanding the nation and socialist internationalism as constructed in mutual connection. Internationalism was not an obstacle but a mechanism for socialist integration into the nation as a political and cultural construct. In the development of the IFTU Council and the subsequent May Day celebrations of 1931, in the recently proclaimed Second Spanish Republic, Spanish socialism took advantage of those events in domestic policy to demonstrate its strength and reaffirm the correctness of joining the government. The PSOE then showed Spain's national identity and the new regime's legitimacy to its European comrades.

The PSOE deployed the symbology and discourses of the working-class identity alongside those of the Spanish national identity. For this purpose, the internationalist formula provided a socialist version of nationally based discourse, while at the same time condemning nationalism in generic terms; it also facilitated socialist identification with the nation without undermining working-class identity. Socialism assumed the Spanish national identity and participated in its reconstruction and social diffusion through the rituals, practices, and discourses of the socialist political culture in which Spain functioned as a legitimate – and naturally unquestioned – political framework.

However, the question remains whether the internationalist patriotism of the socialists aligned with a civic model of the nation. Undoubtedly, such patriotism aimed at peaceful coexistence between countries and national cultures. Nonetheless, socialist adherence to the nation was by no means neutral or purely political. The second part of the article on the local development of socialist internationalism indicates its remarkable cultural and ethnic charge. Particularly during the reorganization of the Spanish republican state, the PSOE raised the banner of internationalism as a political weapon against non-state nationalisms and other socialist tendencies. Thus, in Spain and international organizations, the Socialist Party defended Castilian both as an instrument of the international brotherhood of workers and as a sacred symbol of the Spanish nation.

Finally, future research and comparative history could show whether the PSOE was a representative case study. We believe so. Evidence suggests that, in interwar Europe, the strong presence of the national dimension in socialist internationalism did not represent anything new, nor did it automatically mean its retreat, but rather the continuity of a way of understanding it. The application of the concept of inter-nationalism points us towards a mechanism that promoted the integration of socialism in the nation as a political and cultural construct, a feature probably repeated throughout the European socialist movements – in spite of generating unpleasant dynamics such as the armed defence of the homeland and the adherence to markedly cultural definitions.