It was a routine winter night. Men sat gathered at the Café Fuentes, one of the fabled coffee houses in the medina of Tangier. A chilly gust blew up from the port, dispersing the aroma of tea and cannabis in the air. During the colonial days Hotel Fuentes, owned by the famed Spanish painter Antonio Fuentes, was a favored brasserie for high society. As European and American expats departed, Café Fuentes became a gathering spot for local elders, fishermen working in the port, random hawkers, and jobless youth. By the early 2000s, it was drawing West African migrants who had settled in the medina, hoping to try their luck and cross the Straits of Gibraltar to Spain.

The number of West African migrants arriving in Morocco steadily increased through the 1990s and early 2000s, such that in November 2003, under pressure from the European Union, the Moroccan government passed Law 02-03, granting Moroccan security forces the right to return an illegal immigrant to the border, provided they were not minors, refugees, or asylum seekers. Despite the distinction drawn between expulsion and “returned to the border,” migrants would tell human rights groups of heavy-handed tactics, of being rounded up, coerced to leave, and pushed toward the Algerian frontier.

That wintry night in January 2004 as patrons sat in Café Fuentes watching “the fires and wars” of Iraq on Al Jazeera, three uniformed policemen suddenly appeared at the doorway. They were sent to enforce the new migration law, and were patrolling the medina's alleyways looking for undocumented West African migrants (haraga, as they're called). Several migrants had settled in a motel just down the alley, where a small Senegalese restaurant had opened. A policeman scanned the clientele at the café and made a beeline for a table where an older black man sat holding court, surrounded by younger men. The policeman asked the elder, “Papiers s'il vous plait? Papers please.” The elder responded, “Ana Maghribi. I'm Moroccan. My name is Abdullah.” The policeman repeated the order. Abdallah handed over his carte nationale. By now the café had gone quiet, but for the news broadcast. Someone shouted, “That's our muʿallim, leave him alone.” The policeman looked at the identity card, “You're Moroccan?” Abdallah replied, “I'm speaking to you in Arabic.” The cops responded, “You all speak Arabic these days.” The café erupted into jeers and laughter at the absurdity of the situation, “Leave our muʿallim alone!”

The three young policemen, sent from elsewhere in Morocco to enforce the new migration law, had singled out a beloved community elder, Abdallah El Gourd, one of Morocco's most respected musicians and a global ambassador for Gnawa music, for profiling and humiliation simply because of his skin color. “They left quietly without apologizing,” recalls Hakim, Abdallah's right-hand man for many years, who was sitting at the table that night. This woeful episode illustrates how migration from other parts of Africa is affecting the situation of black Moroccans who may be exposed to the same treatment directed at West African migrants. It also highlights the rather incongruous status of Gnawa music in Morocco. The seventy-five-year-old El Gourd is a Grammy-nominated musician, founder of Dar Gnawa, the first Gnawa cultural association in Morocco, located just down the hill from Café Fuentes. El Gourd has recorded with top American jazz musicians, yet his global reputation did not spare him harassment from Moroccan policemen who had no idea who he was. The discrepant standing of Gnawa music in Morocco offers a useful entry point into both the issue of ethno-racial difference and colonial legacies in Morocco, on the one hand, and the impact of American racial discourses, on the other.

This essay looks at the meaning that the West has projected onto the Gnawa brotherhood over the past century, and how Western scholars have sought to persuade Moroccans of the “value” of Gnawa music. I have long been struck by the contrast between the noisy, politicized, often caustic discourse about North African slavery and Gnawa music in America, and the tepid, ambivalent, if nonchalant attitude toward the music in Morocco, including among leading practitioners. In Morocco, Gnawa music is seen as a fun, but unrefined form, which appeals to hashish-smoking youth and untutored tourists, whereas in America it has come to be viewed by scholars in urgent political terms as the only vestige of the trans-Saharan slave trade in Morocco, the sound of a suppressed history that—like Brazilian candomblé or the American blues—conveys resistance and nostalgia for a lost homeland, and that needs to be saved.

This essay will begin by revisiting foundational works on Gnawa practice by Edward Westermarck and Viviana Pâques, before discussing more recent books on race, music, and colonial policy in Morocco, including Cynthia Becker's Blackness in Morocco, Alessandra Ciucci's Voice of the Rural, Chouki El Hamel's Black Morocco, and Christopher Witulski's Gnawa Lions. I examine how the conversation about Gnawa and African “survivals” in Morocco takes place mostly in the United States. Using the late political theorist Susanne Rudolph's notion of the “imperialism of categories,”Footnote 1 I contend that the categorizing impulse driving much of the American writing today on race and slavery in “Islamic Africa” is, in its classificatory zeal, reminiscent of European and American scholarship from a century ago. Moroccan intellectuals have tried to decolonize the discourse surrounding various musical genres (ʿala, ʿayta, shikhat), but are only recently (albeit reluctantly) turning to Gnawa music.

Jinnealogy

In 1899, the Finnish anthropologist Edward Westermarck published an essay in The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, a primer of sorts on the “Arab Ǧinn,” showing how “the belief in ǧnûn form[ed] a very important part of the actual creed of the Muhammedan population of Morocco, Arab and Berber alike” (Fig. 1). Westermarck offered one of the earliest descriptions of “The so-called Gnawa who stand in an especially intimate relation to ǧnûn, and who are frequently called on to expel them from people who are ill … They are usually, but not always black from the Sudan and they form a regularly-constituted secret society.”Footnote 2 Foreshadowing a debate which would take off several decades later, Westermarck pondered which jinn beliefs were indigenous to Morocco. He notes the parallels between the belief systems of Morocco and the East, “this belief in all its essentials, and in a great many of its details, is identical with that of the Eastern Arabs, and may be said, in the main, to represent part of the old Arab religion, in spite of the great mixture of race which has taken place on African soil.” The Moroccan beliefs in marriages between a man and a female jinn, and the jinn living in people's homes and near water areas, are also found in Egypt and Arabia: “The Oriental ǧinn indicate their presence in very much the same way as their Moorish brethren.”

Figure 1. Westermarck with Moroccans. Source: www.abo.fi/nyheter/edvard-westermarcks-arkiv-vid-abo-akademis-bibliotek-med-i-nationella-varldsminnesregistret/.

In his later work, Ritual and Belief in Morocco, Westermarck reiterates this last point: “The Moorish jnūn resemble in all essentials, and in many details, the jinn of the East.” For example, “The Eastern ǧinn are also afraid of salt and iron.”Footnote 3 But he highlights some specifically local features of jinn belief in Northwest Africa. In both Morocco and Algeria, the jinn are enchained during Ramadan. He suggests that Aisha Qandisha—today thought of as a quintessentially Moroccan jinniyya, central to the Gnawa pantheon—derives from the Arabian desert jinn Sa-lewwah Gule. Yet Westermarck states that the resemblance is not “due to Islamic influence alone” since it runs in multiple directions. Many features of the jinn in Morocco and Arabia are common in the world of spirits writ large: such as the belief among the Berbers of Morocco, Tuareg of Mali, and Kabyle of Algeria in spirits (alchinen) that inhabit rocks and mountains, and which would be absorbed into the “Muhammadan doctrine of saints.” He ultimately concludes: “Owing to our very defective knowledge of the early Berbers, it is to a large extent impossible to decide what elements in the demonology of Morocco are indigenous and what not.”

Westermarck observes that some jnūn (sing. jinn) in Morocco are said to have Sudanese names (but he never states all named jinn come from West Africa, something others would later ascribe to him). He says that the chief magicians in Morocco come from Sus, the southernmost part of Morocco, “where the Negro influence is considerable.” He adds that there “can be no doubt that various practices connected with the belief in jnūn have a Sudanese origin. We have seen that there are intimate relations between jnūn and the negroes, and that the Gnawa, chiefly consisting of negroes, are experts in expelling jnūn from persons who are troubled by them.” He notes the similarity of the Gnawa to the zār in Egypt “though zar's name is Abyssinian, [and] seems to have been introduced by black slaves from the negro tribes of Tropical Africa; and they [Gnawa] also resemble to some extent the rites of the Masubori in Hausa land.” But Westermarck does not say the term “Gnawa” was introduced by slaves from West Africa—he suggests the Sus region as a possible origin. He believes that slaves from West Africa would have found the Moroccan spiritual context “more or less similar” to their own, including ostensibly un-Islamic practices like drinking the blood of sacrificed animals. He writes, “It is easy to understand that the black slaves who came to Morocco found the Moorish belief in jnūn particularly congenial to their own native superstitions and entered into close relations with these spirits by means of practice, which were more or less similar to those in vogue among their own people.” He claims that it is “probable” that the custom of dyafa (animal sacrifice to heal a patient) came from the Sudan, because there is no counterpart to it among Eastern Arabs, but then adds that the practice is very similar to the Moorish dyafa-saafie which exists in Timbuktu. Rather than tracing geographic origins of specific rites, Westermarck concludes with the broad observation that the jinn which prevail in “Muhammedan” countries may be divided into three strata: “Many of them have been preserved from old Arabic paganism, others came introduced by the new religion, and others were added by earlier beliefs and practices prevalent in the countries to which it spread … Jewish and Christian elements were also infused into the demonology of Islam.”

I discuss Westermarck at some length because his multivolume study of ritual in Morocco is a common thread running through the writings of myriad actors preoccupied with race and Gnawa practices—from French colonial administrators to Paul Bowles and the Beats, to American anthropologists, and most recently Moroccan state officials. Westermarck's position was much more nuanced than many of his devotees. He was writing at the peak of colonial expansion, when French colonial officials and scholars were attributing genealogies to different groups in Morocco—and to their cultural practices. The Finnish scholar was deeply involved in the colonial academic enterprise and delivered a lecture at the London School of Economics on “the benefits to be expected from the study of sociology” and “its value to officials in the Colonies.”Footnote 4 He conducted extensive ethnographic research in colonial Morocco, and was aware of French colonialist efforts to impose an ethno-racial taxonomy on the land.

In the 1920s, French colonial ethnologists were realizing that the dichotomy imposed in Algeria of “nomadic Arabs” versus “sedentary Berbers” did not apply so easily to the sharifian kingdom. French military ethnologists and Indigenous affairs specialists argued about the origins of the Haratin of the southeastern oasis, seeing this dark-skinned population as either autochthonous or of East African Kushite origin, as sharecroppers or descendants of slaves. Westermarck did not support these particular propositions. He viewed the Sahel and Morocco as more linked than separate, with common spiritual practices (that were either the product of diffusion or invention) and with Gnawa practitioners most likely coming from Sous. Nor did he give blacks in Morocco a foreign ancestry (as French colonials would for the Gnawa), or maintain that the named spirits in the Moroccan jinn pantheon necessarily came from West Africa. The Finnish scholar may not have agreed with French colonial narratives, but, as historian Edmund Burke has suggested, Westermarck's writings on Moroccan religious practice probably influenced French policy toward sufi brotherhoods and the emplacement of baraka at the center of Moroccan politics.

Another mapping of Gnawa music and black Moroccans was offered by Westermarck's contemporary in 1920s Tangier, the Harlem Renaissance poet Claude McKay. The Jamaican-born writer first visited Morocco in 1928 and ended up living in Tangier from 1930 to 1934, where he completed his classic novel Banjo, as well as Gingertown and Banana Bottom. McKay, who had alighted in Morocco from France, became the first American chronicler of Gnawa music. It was in 1928 at the home of a Martinican friend in Casablanca that McKay first witnessed a Gnawa ceremony that he would call a “primitive rumba.” He later wrote, “The members of the Gueanoea are all pure black. They are the only group of pure Negroes in Morocco,” adding, “They have a special place in the social life of Morocco … Often they are protected by powerful Sherifian families and sultans have consulted them.”Footnote 5 This nonexpert American observer was the first to speculate about the Gnawa's connection to the Moroccan monarchy, their supposed West African origin, and to claim a similarity between their tradition and Afro-Atlantic practice. McKay's pan-Africanist vision of a borderless “Afro-Oriental world” and the Gnawa as being of West African descent became more popular in the 1960s with the arrival of jazz musicians, as did the parallel drawn between the transatlantic and the trans-Sahara, an old abolitionist trope that entered the world of jazz, starting with Randy Weston's album Blue Moses (1972). Gnawa's association with jazz, and later with the protest music of Nass El Ghiwane, granted Gnawa practice a commercial viability and a degree of respectability, distancing it from colonial minstrelsy, when Gnawa street performers were expected to amuse French travelers.

Another American reading of the Gnawa came in the 1930s from anthropologist Carleton Coon, who went on to become president of the American Association of Physical Anthropology, teaching at Harvard and Penn. Coon, an avowed Berberophile, described Gnawa street performers as “racially full Negroes,” who come from Rio de Oro in the Spanish Sahara and who do a “fast jazzy dance” for coins.Footnote 6 He saw Gnawa performance as minstrelsy, and not particularly influential in Moroccan culture. Coon was a well-known proponent of racial science and racial hierarchy, as expressed in his Origin of Races. He was fascinated by the divide between “Berbers” and “Negroes,” and saw Berbers as “Europods,” claiming that even the ancient Egyptians were Berber. He collected hundreds of blood samples and body measurements of the Amazigh population of northern Morocco, and concluded in The Tribes of the Rif that the Riffian Berbers were “white men” of Nordic descent, deliberately ignoring the mixed ancestry and heterogeneity of the Berbers. Coon's belief that Berbers were more capable than other degraded Mediterraneans or Negroes further associated Amazigh identity with white supremacy.

Looking for Qandisha

What Westermarck, Coon, and a range of prewar writers (including Paul Bowles) shared was a sympathy for Berber culture, viewing “Negro” musical influence in Morocco as not particularly significant. These authors were in fact writing at a time when the “Hamitic thesis” was influential, the idea that anything worthwhile in “interior Africa,” any sign of civilization, must have come from Semitic (Middle Eastern), Berber (North African), or European influence: West African slaves brought to North Africa cannot have brought anything worthy. Westermarck was also at the center of this debate about the “invention” versus “diffusion” of culture, whether similar or identical cultural practices can grow up independently in different parts of the world. In his Huxley lecture, delivered at the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1936, he declared that similarities in culture can sometime be due to the “like working of men's minds under like conditions and sometimes it is a proof of a blood relationship, or of intercourse, direct or indirect, between the races among whom it is found.”Footnote 7 He called for more humility in making such claims, referring to belief in the evil eye in Morocco (and the wider Mediterranean world) as an example, of how difficult it is to discern whether a cultural trait is the result of independent invention or transmission from another people. In so writing, Westermarck was again trying to counter some of the more aggressive speculating by French ethnographers about Moroccan eid processions, and claims that these “North West African carnivals” were ancient fertility rites; he stressed, “there is not a shadow of truth in any of these statements.”

Westermarck was critical of the more outlandish French speculating about the origins of Moroccans and Moroccan culture, but he was still a Berbériste, who saw Berbers as the main source of Moroccan culture and a (trans-)Mediterranean race. With the end of colonial rule, however, opinion began to turn against his “Mediterranean race” hypothesis, and Berberphilia in general. When Coon's Origin of Races was published in 1962, the tide was already turning, rapidly, against the idea that any element of civilization in “Black Africa” must have come from outside. Decolonization and civil rights mobilization in the US prompted a paradigm shift in anthropology and ethnomusicology. New interpretations of Gnawa music arose. With the decline of the Hamitic thesis, and with the rise of an Arab nationalism hostile to Berber language, more Black-centric explanations of Gnawa found leeway. In America, anthropologists like Melville Herskovits, Zora Neale Hurston, and Robert Farris Thompson were speaking of “survivals” and “cultural unities” in African-descent cultures in the New World, and by the early 1960s, left-leaning scholars in Europe began offering similar takes on North African history, reversing the direction of civilizational impact.

In 1964, the French ethnologist Viviana Pâques published a tome titled L'Arbre cosmique dans la pensée populaire et dans la vie quotidienne du nord-ouest africain (hereafter L'Arbre cosmique, or The Cosmic Tree), the first landmark academic treatment of slavery and religious practice in Northwest Africa. Pâques, who died in 2007, was enormously influential in the study of religion and slavery in the region, having undertaken decades of fieldwork in the Marrakesh area. She was a pillar of the Essaouira Gnawa festival (launched in 1998), and her shadow still looms large over the Francophone and Anglophone conversation on music and slavery in the Maghrib. By some accounts, Pâques became a practitioner and muqaddama herself. By the 1970s, Pâques was writing specifically on the Gnawa, arguing, as if in response to McKay, that the Gnawa community includes not only blacks or former slaves, but also adepts of the “white race”—Arabs, Berbers, and Jews, who call themselves “sons of Bilal.” Every Gnawi identifies as a “slave” and “black” because they are children of Sidna Bilal “no matter what his ethnic or social origins may be.”Footnote 8 If others speculated that the term Gnawa came from Guinea, Ghana, Kano, or Agnaw (meaning “mute” in Berber), she held that the term most likely originates in the Tamazight phrase igri ignawen (“in the field of the cloudy sky” or turbulent wind), since the Gnawa describe themselves as the “people of turbulence.”Footnote 9 Pâques's imagined geography of northern Africa was similar to Bowles's—a North African cultural system extending seamlessly from the Sahara to the Mediterranean, and connected by a pre-Islamic African essence. Unlike Bowles, however, she evinced little animus toward Arabs and saw “Negro” culture as incredibly enriching. Pâques also saw more phallic symbolism in Gnawa cosmogony than earlier or subsequent observers.

“The Gnawa order,” Pâques claims, “is found, with identical beliefs and rituals, throughout northern Africa, from the Mediterranean to Timbuktu, from Libya to Chad and the Sudan.” Like Ibn al-ʿArabi who saw the universe as an upside-down tree, with roots in the sky, and branches in the ground, she argued, the Gnawa have a similarly “reversed” view of the world, such that the goat is the highest animal, with the ram at the bottom. In chapter after chapter, Pâques “decodes” the rituals, colors, types of incense, and candles. “Everything is code,” she says, the big drum and small drum represent man and his genitals. “Man has a female organ which is his phallus … and the woman has a male organ which is the uterus.” She mentions symbols that the Gnawa share with other North African orders: the blacksmith, who is in perpetual motion, representing the cycle of death and resurrection (also called the monkey because of the rising and falling, a term that is also a euphemism for the male sex organ). She maintains that for the Gnawa the mountains of Sidi Fars and Moulay Brahim overlooking Marrakech are phallic symbols, representing the “foreskin” and “the head of the organ.” The stringed guembri instrument represents the sultan or Allah, and the player is Bilal, his slave. A drum represents space and is curved just as God curved the universe. In the Gnawa worldview, a mythical marriage took place, whereby the night cut off the head of the earth, which caught fire and became the sun, and in turn fell back from the cosmic world to the terrestrial heaven. “This operation,” she says, “was the first circumcision.”Footnote 10

Pâques's argument has a peculiar anti-Eurocentric, pan-African tilt. She was highlighting what Africans—including black Africans—brought to the Mediterranean world instead of what Europe brought to Africa. She says, for instance, that Greece was more influenced by Cyrenaica than vice versa. She was contesting the notion that nothing good comes from “interior Africa.” In surveying the Gnawa order's widespread influence, she concludes that the slaves were not bringing anything drastically new to North Africa, because there is a an extraordinary “continuity of civilizational thought between Black Africa and White Africa.” In this worldview, the Prophet Muhammad is a light-refracting prism that spreads the seven colors represented by the Gnawa colors. The Prophet transcends the seven heavens to reach the void, with the slaughter at the end of the lila before daybreak, representing the blood of a deflowering. Pâques also underscored the continuity between various Maghribian orders (like Gnawa and Aissawa) and those in the Sahara. What is true for Gnawa is true for Aissawa, who are speaking the same “meta-language” illegible to Westerners. “Traditional civilization is suspicious of conceptualization.” She concludes that there is a “vieux fond Africain” (an old African fount), a mystical African consciousness, underpinning the fundamentally homogenous civilization that is Saharan-Sudanese in origin, and that underlies most of West African or Northwest African culture. She even raises the possibility of a Saharan Moses. This civilization, she says, “may antedate any Mediterranean one”—and exists wherever else peoples of black African origin in North Africa, most frequently former slaves, have organized themselves in substantial numbers. Pâques thus sees black Africans as carriers of a belief system, but they are not the only ones—and, like Westermarck, this is not to say that such practices didn't already exist in North Africa.

The Cosmic Tree may have been progressive and “pro-African” in a 1960s Francophone context in showing how Africa fertilized Europe, but the book was not well received in the Anglophone world. Her argument of a Saharan/North African civilization fecundating Europe still smacked of the “nothing good comes from (interior) Africa” argument of recent decades. She wrote her book at a time when not only was the idea of West African cultural continuities and “Africanisms” gaining popularity in the American and British academy and Black Arts communities, but a boundary was beginning to be drawn—this time along vindicationist, anti-racist grounds—between a dominant, exploitative “Arab North Africa” versus an exploited “Black Africa.” Pâques's work received a harsh rebuke from a young anthropologist named Ernest Gellner, then based at the London School of Economics. “The book [Cosmic Tree] begins with the problem of the transformation of religious beliefs and practices by Negro slaves from Sub Saharan Africa to the Maghrib. The question might have led to the anticipation of findings analogous to those concerning the survivals of West African religious elements in Latin America,” wrote Gellner. “In fact, the authoress claims to have been led by the material to quite a different conclusion: not the survival of sub-Saharan elements in a Muslim spiritual world, but the existence of one homogenous religion underlying both Maghrebian and Sudanese popular religion.” He called the thesis “breathtakingly audacious,” “implausible,” “less than fully lucid,” and “also in no way demonstrated.”Footnote 11 Subsequent commentators speculated that Pâques was inspired by her teacher the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule, who, through conversations with the Dogon elder Ogotemmeli, wrote about the cosmogony and symbolism of the Dogon people of central Mali. Pâques was perhaps trying to find her own Ogotemmeli, or hoping to find a Dogon cosmogony north of the Sahara. Others have noted The Cosmic Tree's uncanny resemblance to Hurston's Tell My Horse, the American author's account of Jamaican “nine-night” and Haitian vodun rituals.Footnote 12 Regrettably, for all her outlandish, unsubstantiated claims, Pâques continues to influence discourse on slavery and religion in the Maghrib, with younger scholars, record labels, Moroccan media outlets, and even Ministry of Culture officials repeating her assertions (if unwittingly).

In his review of Pâques, Gellner was gesturing to the argument that Herskovits and Hurston had introduced in the 1930s regarding African retentions and “American Negroisms” in African-descent communities in the New World, one that was entering the mainstream by the 1960s. Following the 1967 war, with the decline of Nasserist Egypt then a major pivot for the African American left, and rising black-Jewish tensions in the US, the notion of a cultural synthesis between West and North Africa became polemical and passé. The notion of black cultural survivals in North Africa began to be raised. The jazz musicians (often Muslim) dabbling in Gnawa music spoke of West African retentions in the Maghrib, a borderless North and West Africa. By the early 1970s, a more nationalist Afrocentrist trend had risen that saw a clear divide between “white” North Africa oppressing an “indigenous” Black Africa. Gellner's harsh critique of Pâques proved prescient: as Black studies and civil rights movements gained momentum in the US, American scholars of Gnawa assigned a larger role to the West African transmission thesis, claiming strong parallels with the Black Atlantic, deploying concepts of “diaspora” and “indigeneity,” and edging out the colonial-era writers who saw such cultural practices as either Berber or Middle Eastern in origin.

An influential American book that made this continuities and retentions argument—using Westermarck and Pâques's work—was Vincent Crapanzano's The Hamadsha.Footnote 13 The author argued that while belief in the jinn was part of Islamic practice, the Moroccan belief in a “named jinn” like Lala Mira or Aisha Qandisha, who have formal names and specific characteristics, are West African retentions. Crapanzano saw these beliefs as sub-Saharan retentions that Gnawa musicians passed on to other quasi-sufi groups like the Hamadsha and Issawa. It is worth reiterating that Westermarck did not say that Qandisha's name or spirit came from West Africa, but rather that her name is distinctly of Eastern origin; he speculated that it could be the cult of Astart worshipped by Canaanites, Hebrews, and Phoenicians, and that her husband Hammu Qayn was perhaps the Carthaginian god Haman. Yet as different social movements arose in the US, remapping North Africa, Qandisha was given a West African origin.

“Colonial Acoustic Regime”

In her recently published books, the Arabic-language Aswat al-ʿAyta (The Voices of Aita) and The Voice of the Rural: Music, Poetry, and Masculinity among Migrant Moroccan Men in Umbria, ethnomusicologist Alessandra Ciucci looks at Moroccan efforts to decolonize what she calls the “colonial acoustic regime.” Focusing on the rural music of ʿayta and ʿabidat arrma, Ciucci examines the local labels (like shaʿbi/folk) that are pinned on various sounds in Morocco, and how different voices evoke different labels and visual images. She looks particularly at how the full-throated voice is considered coarse (hresh) and conjures a particular understanding of the rural. Her latter work traces how such understandings of ʿayta change with migration from Morocco to Italy.

Ciucci discusses the efforts of (mostly male) Moroccan intellectuals to counter the colonial narratives and classifications of certain music; for instance, efforts to rehabilitate the reputation of ʿayta and shikhat and the women who sing ʿayta (seen as disreputable). Starting in the 1960s, postcolonial scholars began making the argument that ʿayta drew on written texts of epic Beni Hillel poetry, and that the much-maligned shikhat were actually unsung heroes and carriers of a tradition, and if ʿayta had any immoral associations it was because French colonialists categorized it as a “folklore,” thus linking it to tourism. These attempts at “revalorization,” Ciucci shows, paid off when ʿayta was incorporated into the patrimoine culturelle marocain, and celebrated at a festival in Safi in 2001. Ciucci proves a discerning guide as she works through the French Protectorate's musical archive in Morocco, parsing the foundational texts of (in)famous scholar-administrators like Prosper Ricard and Alexis Chottin.

In 1921, the French founded the Institute of Advanced Moroccan Studies and the Service des arts indigènes to promote research in history, antiquities, local medical practices, language dialects, poetry, and song. The institute went on to publish Bulletin and the well-known journal Hespéris. As director of the Service of Indigenous Arts in Rabat, scholar-administrator Ricard called for an effort to catalog and resurrect Morocco's musical past. He appointed Chottin, the Algerian-born musician and ethnographer, as director of the Conservatory of Moroccan Music in Rabat, and together published Corpus de musique marocaine. Chottin went on to famously divide Moroccan music into two categories, genres with a “melodic phase,” the “prerogative of the civilized and sophisticated beings,” and genres with a “rhythmic phase” associated with the “primitive and uncultivated being.”Footnote 14 Chottin's binary of Moroccan music accorded with Resident-General Louis Hubert Lyautey's vision of Morocco as bifurcated between Arabs and Berbers, the latter deemed a “sister population” culturally closer to France. Chottin also had a keen interest in Arab Andalusian (melodic) music and Amazigh (rhythmic) music, because, as Hasan Najmi has argued, he believed both genres could teach France about its classical roots: Andalusian music had preserved medieval Iberian history, and Amazigh music was linked to Greek civilization.Footnote 15

In his subsequent Tableau de la musique marocaine, Chottin distinguishes further between Arab music as “classical music” of Andalusian origin, an art form of the bourgeoisie and the royal court, and “folk music” influenced by Andalusian and Berber music, but also exhibiting influences of “foreign origin” like Turkish music, or “Negro music” associated with certain confraternities.Footnote 16 In discussing the music of sufi brotherhoods, Chottin mentions the Issawa, Hamadsha, Tijaniyya, Derqaoua, and Heddaoua, but he singles out the Gnawa for praise, noting their “remarkable” sounds and the “dramatic intensity” of their spectacle. He also observes that their repertoire and “rectangular” guembri instrument and metallic castanets are clearly of “Sudanese origin.” Chottin is also the first to contend that Gnawa music influenced other Moroccan groups: he observes, for instance, that the Berbers of Sous (Chleuh de Souss) borrowed their “defective scales” (leurs games defectives) from the Gnawa. Like other writers in the 1930s and 1940s (Bowles, for instance), Chottin saw Gnawa music as unsophisticated and a corrupting “foreign” influence. The French may not have been particularly interested in Gnawa music, but they were deeply invested in the question of Gnawa origins. After independence, state officials would celebrate and elevate Andalusian style as the kingdom's national music, sidelining Amazigh music and the sounds of low-status sufi confraternities. In the 1970s, with the rise of Nass El Ghiwane, the Amazigh cultural movement, and Gnawa-jazz fusion on the world music scene, Gnawa and Amazigh music would slowly enter the Moroccan musical mainstream, unsettling the national cultural hierarchy.

“This Fascinating People”

Chouki El Hamel's Black Morocco makes a bold intervention in the Gnawa debate. The author begins by saying that Gnawa music is the only vestige we have today of the Moroccan slave's voice, the musical equivalent of a slave narrative: “the most revealing testimony of slavery and its legacy in Morocco is the very existence of the Gnawa: a spiritual order of traditionally black Muslim people who are descendants of enslaved sub-Saharan West Africans.”Footnote 17 El Hamel contends that the Gnawa are a “distinct social group” that have a connection to their Manding heritage, asserting as evidence that “Gnawa” and “Griot” have a common etymological root.

El Hamel may be right that Gnawa chants are the only trace of the slave's voice, but the book does not define the term “Gnawa,” speaking interchangeably of “the Gnawa,” “blacks,” and “Haratin,” which makes for a muddled argument. El Hamel first describes the Gnawa rather awkwardly as “traditionally black and Muslim,” when the group historically drew censure for its heterodox practices; then he describes practitioners of Gnawa music as a “diaspora,” an ethnic group, “a racialized minority,” even though, by his own account, members of the Gnawa order do not define themselves as such. He refers to this sufi order today as a “distinct ethnic group,” with “ethnic solidarity” at a time when few of the leading practitioners are black, and when the ritual is changing. El Hamel defines “diaspora” as a shared identity that transcends geographic boundaries, and articulates a desire for return to their original homeland, before adding: “The Gnawa do not appear to have any desire to return to their ancestral homeland.”Footnote 18

Black Morocco's main limitation is that the author adopts a transatlantic framework to understand Gnawa practice and slavery in Morocco; thus he divides the Moroccan population into settlers (Arabs), natives (Berbers), and diaspora (blacks), adding that as in the US, in Morocco there is a “one-drop rule,” which allows part-“Black” children to be co-opted upward. Quoting the late theologian James Cone, El Hamel also claims that Gnawa is very similar to black spirituals which enabled slaves in America to “retain a measure of their African identity,” in an alien land. El Hamel's account of Gnawa music echoes the story of Negro spirituals and the blues in the Antebellum South, replete with maroon communities and “lodges.” During the reign of Moulay Ismail (r. 1672–1727), he says, there was a “great dispersion of the blacks across Morocco”; as they “scattered” across the kingdom, “they founded communal centers where their culture is celebrated.” El Hamel offers absolutely no description or evidence for said communal centers; unlike other sufi groups, the Gnawa are known to have no organized physical zawāyā (lodges, sing. zāwiya).Footnote 19 After building the case that black Moroccans are excluded and segregated, El Hamel also says they are integrated and have found “legitimacy” and “acceptance.” He also alleges that Gnawa ceremonies happen on a regular basis because, “Slavery itself was the initial wound and because it was never officially recognized or healed it was therefore destined to repeat itself.” This functionalist argument raises the question: If the Moroccan authorities were to recognize slavery, would that end the need for the lila healing ceremony?

El Hamel places himself solidly within the “cultural diffusion” camp, claiming that Gnawa music not only came from West Africa, but echoing anthropologist Crapanzano's argument that Gnawa went on to influence other Berber and Arab “mystic [sic] orders” in Morocco as well, bringing Sahelian practices like trance, “contacts with spirits,” and named jnūn to brotherhoods like the Issawa and Hamadsha. As evidence, El Hamel cites Westermarck's Ritual and Belief in Morocco as saying that “this influence [on other mystic orders] is very conspicuous [from] the rites of the Gnawa, and will probably prove to have had a considerably larger scope than is known at present.” Except that Westermarck doesn't quite say this. By interpolating “from” and “on other mystic orders” to Westermarck's original sentence, El Hamel changes the meaning of Westermarck's argument—which pointed to cultural flows from southern Morocco to Gnawa culture—to having Westermarck say influence flowed from Gnawa culture to other “mystic orders.” Westermarck also never says that trance or named jnūn came from West Africa.

There is no doubt that Gnawa music has preserved the memory of slavery in Morocco, with lyrics speaking of abduction, suffering, and privation, but El Hamel does not show how Gnawa is an ethnicity or even a distinct social group (as opposed to a sufi organization, musical culture, or lineage). The Haratin have been described as an “ethnic” group, but how are the Gnawa an ethnicity? If excluded because of skin color, then why not call them a race? The history of Gnawa music that he outlines is more a description of what happened in the US post-Reconstruction, a process of historical recovery and identity formation that allowed descendants of slaves to mobilize for rights as Black Americans in a partial democracy. No such mobilization by descendants of slaves has occurred in Morocco. More than offering an accurate description of slavery in Morocco, Black Morocco provides a useful glimpse into the current culture wars in the US, and how local American history of slavery is still projected onto “Islamic Africa,” a practice that historians say began with the Barbary Wars.

Colonial Effects

The claim that the Gnawa order influenced other sufi groups seems to have a European origin, and is connected to the broader colonial argument that the ʿAbid al-Bukhari, the so-called Black Guard troops, came from the Sahel. In the early 1700s, European observers began claiming that members of the Moroccan army were “Bambareens” from the “Coasts of Guinea.” In the early 1900s, one particularly influential exponent of this hypothesis was René Brunel, the French colonial commissioner of Oujda. Brunel wrote extensively on Moroccan sufi orders, arguing not only that the ʿAbid al-Bukhari came from West Africa, but that in the 1900s the slave-soldiers tended to affiliate en masse with the same sufi brotherhood, and that the Issawa master healers had adopted Gnawa rituals, particularly the use of blood.Footnote 20 (Brunel's study on the Issawa is cited by Pâques and Crapanzano, and is as influential as the work of his contemporary and challenger Westermarck.) One prominent critic of this colonial narrative that claimed Moroccan sultans brought back an army of thousands from the conquered Songhai Empire is American historian Allan Meyers. In the 1970s, Meyers, in a series of articles, argued that when Moulay Ismail, faced with European and Ottoman competition, began to recruit the ʿAbid al-Bukhari, he drew largely on local Haratin, rather than Songhai migrants. Foreign (non-Moroccan) sources may have argued, for three centuries, that the ʿAbid al-Bukhari were Sudanese captives or refugees, most likely Bambara from Timbuktu. However, Meyers insisted that the Moroccan sources showed that they were locally recruited and composed “entirely of black slaves and a people of ambiguous social and racial status called Haratin.”Footnote 21

Meyers was responding to colonial writers like Brunel, but also contemporary American anthropologists who were using Brunel and Westermarck to make extravagant claims about Gnawa culture. As Meyers put it, the question of whether the ʿAbid al-Bukhari came from West Africa or southern Morocco has implications for “the matter of black Sudanese so-called survivals in popular Moroccan Islam,” because “it is widely contended that many of the animist aspects of Moroccan religion are the result of cultural diffusion from the Sudan, that these heterodox features were introduced into Morocco by Sudanese migrants, slaves presumably, from whom they diffused to the larger population.”Footnote 22 He says the “diffusionist” scholars (from colonial ethnographers to Crapanzano) were very vague about how “a Sudanese complex of traits” was established in Moroccan religious practice, “with good reason; the evidence for Sudanese origins was virtually nil. In Algiers, Tripoli and Tunis—on the other hand—not only has religious behaviour been shown to have originated in the Sudan, it has also been shown to have been associated with slaves and freed migrants from particular parts of the Sudan … There is no such evidence from Morocco.” Meyers also reminds readers that that the ʿAbid al-Bukhari was reconstituted by the French after the establishment of the French Protectorate in 1912, and just because black troops may have congregated at a particular zāwiya in the 1900s, “great care must be taken before projecting these data into the past. There is no evidence that the ʿAbid had been affiliated with any particular religious order before that time.”

As various scholars have shown, French colonial rule established an elaborate system of ethno-racial classification in Morocco. French officials defined “Arab,” “Berber,” “Jewish,” and “Black,” creating different genealogies and legal systems for each category. They also drew a distinction between “Islam noir” and “Islam maure” that would underpin French colonial thought into the 20th century. Colonialists constructed black Moroccans first as “indigenous” and then as a “diaspora” that originated in West Africa. As Paul Silverstein has shown, colonial military and scientific logic divided “autochthonous” Berbers and “allochthonous” Haratin along racialized lines as “White” and “Black” groups—or “castes”—and this divide continues to shape intercommunal relations in southeast Morocco today. Most studies of Gnawa music have paid little attention to the role of colonial policy. Black Morocco, for instance, offers a rather rosy-eyed view of French colonial rule in Morocco, stating that French imperialism spurred capitalist modernization and abolition in Morocco; European abolitionism grew out of the European enlightenment, “which brought with it many humanitarian reforms, and in part because of the growth of industrial capitalism which brought with it new labor relationships based on wages rather than servitude.” But there is little in Black Morocco on France's ethno-racial policies and genealogy-building, and how that shaped Gnawa culture. This is where Cynthia Becker's Blackness in Morocco makes an invaluable contribution.

“Colonial Minstrelsy”

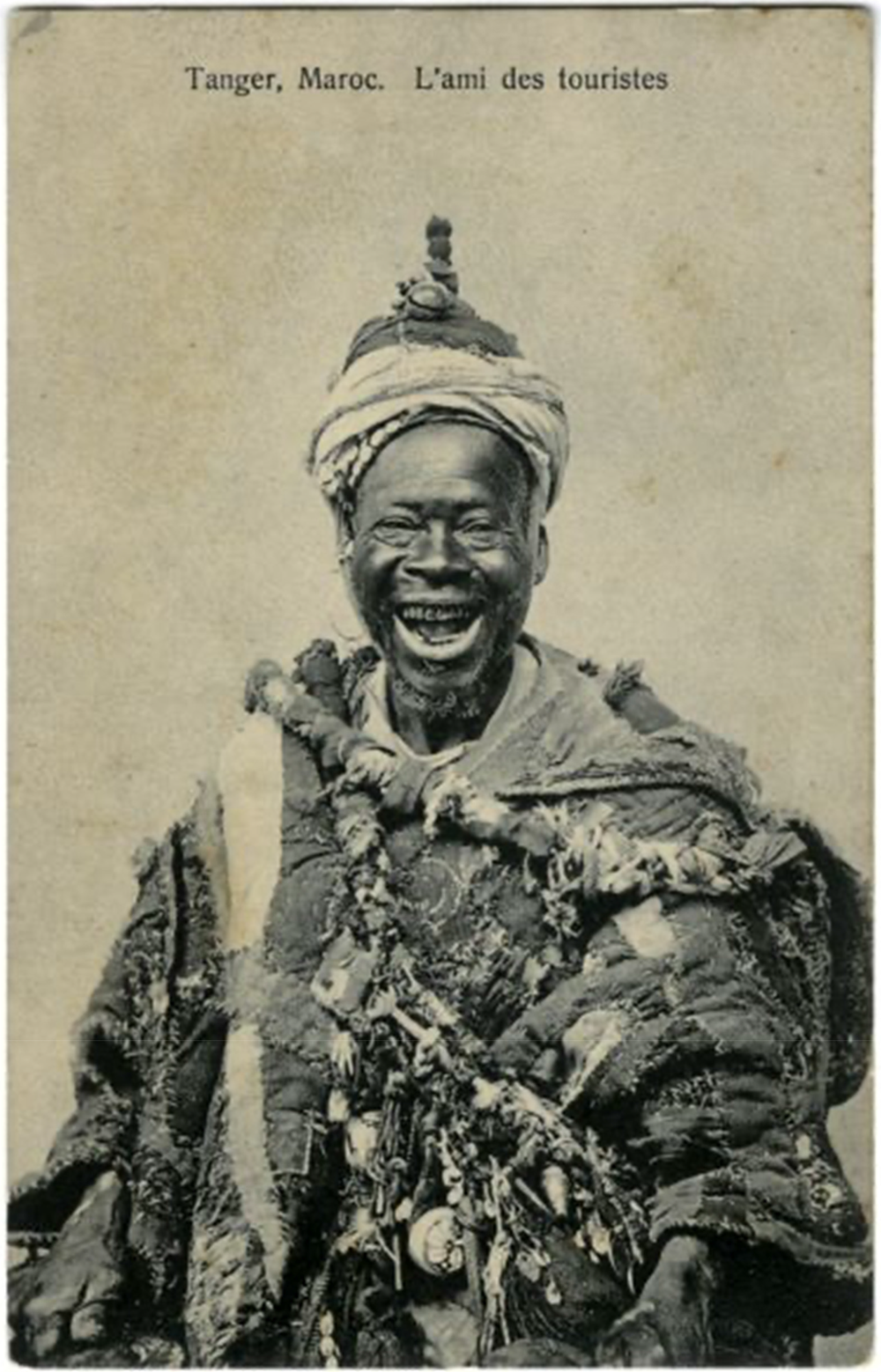

Becker, an art historian, scrutinizes French colonial photography's keen interest in black Moroccans. She makes a compelling case that Gnawa identity was a colonial construct of sorts, emerging with the onset of French colonial rule in 1912, specifically when the sultan lifted a ban on photography. It was thereafter that dark-skinned men in shell-adorned headdresses began posing and playing instruments for the tourist industry (Fig. 2). Former slaves became “Gnawa” by performing for the foreign camera, in a degrading manner comparable to the black-face minstrelsy in the US. Becker showcases a remarkable set of photographs of Gnawa musicians posing for the foreign camera, noting how the Western fascination with dark-skinned musicians “as embodiments of foreign exoticism” led to the “codification” of a Gnawa identity: “a body of images was built up into a European imaginary that ultimately redounded upon black musicians as a set of expectations to meet, paradigms to fulfill, and models to replicate. Black men were shown as exotic and rhythmically gifted bearers of tradition who became part of a homogenous community known as ‘Gnawa.’” She maintains that, in response to a foreign and local gaze, even Haratin from southern Morocco became “Gnawa” when they migrated to urban centers.

Figure 2. The Gnawa as “the tourists’ friend,” Tanger, Maroc. Postcard published by S. J. Nahon, Magasin de Nouveautés. Tangier, Morocco, ca. 1910.

Yet questions remain—Was French interest in the Gnawa linked to their rebuilding of the Black Guard? Why did French colonials, in the name of abolition, attribute a foreign origin to black Moroccans? Brunel's insistence that the Gnawa not only came from West Africa but that they spread practices like trancing and blood sacrifice to other sufi groups was, as mentioned, a reflection of contemporary French racial thinking about Islam noir and Islam maure. With the conquest of Mauritania, the French had developed the category of Islam maure to understand the Moors (bidan), who were reminiscent of the Arabs in Algeria, seen as practicing orthodox Islam and superior to other communities in Senegal-Mauritania. Islam noir, on the other hand, was used in the “Soudan,” to designate “black” societies, who practiced a heterodox Islam that often blended into a paganism as one moved south. As one colonial administrator, Robert Arnaud, explained in 1912: “it is very much in our interest to nurture and develop in West Africa a purely ‘African Islam,’ calling for a kind of Muslim Ethiopianism in West Africa.”Footnote 23 Colonial policy thus enforced the (Hegelian) split between sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghrib, such that dark-skinned Moroccans were seen as originally West Africa, bringing the heterodox practices of Islam noir into the Maghrib.

French ethnographers in Morocco developed a similar dichotomy between the heterodox, indigenous saint-venerating Berbers and the strict, Arab conquerors. As Edmund Burke describes in The Ethnographic State, French officials created the category of “Moroccan Islam” as a “timeless system of beliefs and practices, as well as a political system, with the king, the Commander of the Faithful, at its core.” At the heart of Moroccan Islam was sharifism (descent from the family of the Prophet), belief in baraka, and saint veneration. As Burke observes, Westermarck was the first to write about the role of baraka in Moroccan society, but “baraka was assigned a central role in the discourse on Moroccan Islam only following the establishment of the protectorate.”Footnote 24 French policy encouraged all kinds of local practices as a way to restore the past, but also to counter the reformist Islam coming from the Arab East. As Moroccan historian Abdallah Laroui put it, “One attempted to encourage even the most abstruse particularisms in order to give popular religion a local, naturalistic and primitive character.”Footnote 25 In re-constituting the Black Guard, French administrators were thus trying to reproduce the monarchy as it looked in the days of Moulay Ismail. That said, there's little evidence that the French encouraged Gnawa practices in the palace, or nudged black troops into specific zawāyā; the earliest descriptions of slavery and palace life on the eve of colonialism do not mention Gnawa practices.

“A Provable Connection”?

At the heart of the American discourse on Gnawa—and music fans’ love of it worldwide—is the belief that not only did the ʿAbid al-Bukhari come from the Sahel, but they—and subsequent slaves—brought musical practices, instruments, and animist beliefs with them, and that these “retentions” can still be heard in Gnawa music today making it politically and morally momentous, and needing to be “salvaged.” The Sahelian/sub-Saharan “retentions” are said to come in four places: rituals, language, pentatonic modes, and instrumentation. The American discourse on Gnawa “retentions” was sparked by a landmark essay published in 1981 by pioneering ethnomusicologist Philip Schuyler. “The beliefs and practices of the Gnawa religious brotherhood represent a fusion of Islamic and West African ideas,” wrote Schuyler; the songs speak of slavery and exile, the instruments, the ritual garb with cowrie shells all signal a “sub-Saharan origin.” The lila ceremony with its rituals and dancing shows “rites more reminiscent of Haitian vodun, or of West African hunting societies, than of the rites of more orthodox Islamic brotherhoods in North Africa.”Footnote 26

Forty years later the consensus is shifting, in part because Gnawa rituals are changing, but also with the decolonial turn, more scholars are noting how American writers were often grafting what they were hearing, their specifically American audio impressions, onto Gnawa history. In other words, just because Gnawa sounds like the blues to an American listener does not mean Gnawa has the same structure or even origins. As Samuel A. Floyd writes in The Power of Black Music, “the similarity of the jazz improvisation event to the African dance possession event [is] too striking and provocative to dismiss, but in the absence of a provable connection, it can only be viewed as the realization of an aspect of ritual and of cultural memory.”Footnote 27 There is no doubt that Gnawa songs speak of slavery and ”Sudani” origins, but the argument that the non-Arabic words therein are “sub-Saharan” in origin, or that Gnawa rhythms derived from Sahelian pentatonicism traveled northward to North Africa, is not so airtight anymore.

To be sure, the retentions argument is made not only by Westerners, but also by Moroccan scholars and artists (including festival promoters). Moroccan sociologist Abdelhai Diouri published a fascinating study thirty years ago suggesting that lahlou, the saltless dish prepared for Sidi Hammou and the red spirits, was a symbolic reminder of a pre-slave past (since salt was traded for slaves, and slaves were used to excavate salt in the Sahara). Diouiri also pointed to the use of the incense jawi (benzoin) in lilas as a link to the Sahel, given its use in funerary meals in sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 28 Such speculative writing—which invariably cites Westermarck—remains just that: well-intentioned conjecture. Westermarck did write of salt-free food being offered to jnūn, “masters of the home,” in dyafa ceremonies in Tangier, and noted the use of benzoin across the kingdom, but he did not claim a link to West Africa. In Blackness in Morocco, Becker moves away from some of the stronger claims of linguistic continuities that she made in earlier work (that, for instance, Moroccan children use the “Sudani” term fofo to refer to fire, and that that derives from the Mandinke phrase “fofo demba” (light the lamp)).Footnote 29 But in her recent book she still advances etymologies for various terms in Gnawa practice; for instance, claiming that bangar derives from wangara, “a term initially used in West Africa that took different meanings at different locales during different time periods.” She contends that the term Gnawa “migrated” from the Kanuri region of Nigeria and means “little ones” or more likely “inferior ones”; and the phrase “bu gangi” comes from the Zarma word genji (spirit). Becker also maintains that the qraqeb, the iron castanets used by the Gnawa to evoke the mystical power of the West African blacksmith, deliberately mimic the sound made by “the chains used to shackle the enslaved.” This too is a dubious claim. (In her book, Ciucci mentions that ʿabidat arrma also use metal percussive instruments.) Overall, it's not clear what the point of all this avid speculating around Gnawa is.

For a century, linguists have debated Sahelian influence on North African languages, and emphasized that such influence is rare, and exists, if at all, in the music of the descendants of slaves. In a recent literature review, linguist Lameen Souag notes how the Sahelian term ganga (drum) is one such term that entered Arabic and Berber dialects in Algeria and Morocco (in Tunisia it is banga).Footnote 30 Likewise, guimbri (also spelled guinbri) is another term said to be a loanword. In 1920, the British musicologist Henry George Farmer had argued that Ibn Battuta had used the term qanabir in his description of the royal court of Timbuktu, suggesting a strong possibility that the term migrated northward from Mali. In 1955, Maurice Delafosse claimed in his dictionary that the term derives from the Manding word for a four-stringed guitar (konibara). More recently, Eric Charry has argued that this was an error by a copyist, a misrendering of the term that Ibn Battuta used, ṭanābīr (sing. ṭanbūr), a word for lutes used in medieval sciences, and positing that guimbri comes from Soninke (ganbare).Footnote 31 Yet other scholars, like linguist Ousmane Diagana, argue the opposite, that the term is an Arabic loanword—coming possibly from qunbur (lark)—that entered Soninke, but the “the question remains open.”Footnote 32 As Souag writes, “While sub-Saharan lexical influence in North Africa is real, it should not be exaggerated. Only few non-music-related loans (pumpkin, sorghum, maize, cayenne pepper and acacia) are observed on the coast, and even there, they remain largely restricted to Bedouin or Zenati varieties. Many northern dialects use none of these.”Footnote 33 Yet even Souag relies on Pâques's conjectural writing in highlighting some of these “sub-Saharan” loanwords.

As Westermarck observed, linguistic and musical influences and material culture can travel in any multiple directions, though not necessarily in tandem. If the term guinbri is contested, so is the origin of the instrument itself. From liner notes to music blogs, the Gnawa guembri is depicted as an instrument that traveled from the Sahel to Morocco, a tangible vestige of the trans-Saharan slave trade and whose “ancestor” instruments are in West Africa.Footnote 34 Yet scholars have countered that the instrument could have come from Pharaonic Egypt. The Austrian musicologist Gerhard Kubik contends that with the arrival of the Arabs in North Africa, “transculturation processes” in music unfolded rapidly making it difficult to identify the origin of vocal styles or instruments. “Although it is clear that plucked lutes in North Africa and ancient Egypt are distinct from those of West Africa, the evidence for diffusion is difficult to deny,” writes Kubik. “Since ancient Egypt functioned as a cultural sponge, often absorbing foreign innovations, it is logical to keep the discussion about the directions of diffusion open.”Footnote 35 Bassist and ethnomusicologist Tim Fuson has made a similar argument, noting that the Gnawa guembri is the only Moroccan kind with a rectangular shape, and as such is more akin to the ancient Egyptian rectangular lutes than the more slender, rounded Sahelian lutes. Also, “Saharan and Sahelian lutes are tuned to a much higher pitch than the deep resonant tones of the Gnawa guinbri.”Footnote 36 The guimbri, adds Fuson, with its low register, sounds more like the Moroccan ziyani lotar, which is pear-shaped.

Another alleged West African retention in Gnawa music is the minor pentatonic scale, with its flatted seventh note which allegedly resembles the so-called blues scale and notes used in the blues. Fuson questions this claim as well: “Gnawa music has two basic pentatonic scales—a lighter scale that sounds Asian and is also found in Soussi (southern Berber) music—I call that the G-mode, and a second heavier pentatonic scale, which I call the D-mode. The D-scale is specific to the Gnawa, and has also sounded West African to me, but I have been unable to find an exact duplication of it in Sahelian or West African musics. I can't say the heavier scale comes from West Africa, anymore than I can say the Asian-sounding scale comes from Asia.”Footnote 37 In a much-cited paragraph from his dissertation, “Musicking Moves and Ritual Grooves across the Moroccan Gnawa Night,” Fuson writes, “there does not appear to be a single ‘parent’ tradition anywhere south of Morocco that duplicates the sound or usage of the Gnawa guembri”; Sahelian lutes are high-pitched, whereas the Gnawa guimbri is low-pitched and bassy.Footnote 38 Depictions of the guembri as the first African bass—which traveled northward from its West African birthplace—are thus complicated by the absence of a “parent” instrument, but also, adds Fuson, by the fact that while the guembri is a prominent instrument in the Gnawa lila ceremony, Sahelian lutes are not used in possession ceremonies.

Scholars have contested the Gnawa-blues pentatonic connection as well. Ciucci argues that the blues-Gnawa framing reduces the blues tradition to scales, pitches, and frequency, neglecting critical issues like timbre, tonality, melodic motives, and the quality and materiality of the sound, thus severing Sahelian music's thousand-year-old links to the Arab-Islamic world.Footnote 39 Regarding the genealogy of the blues, Kubik observes, “[I]t has been generally accepted that the cultural genealogy of African-American music in North America—in contrast to that of the Caribbean—points predominantly to the savanna and Sahel zone of West Africa, rather than the coast … a majority of the blues’ traits can be firmly traced to areas in West Africa that represent a contact zone between an ancient sub-Saharan culture world of agriculturalists and an Arabic-Islamic culture world that became effective from 700 CE on. Many traits in the tonal world of blues can be better understood as a thoroughly processed and transformed Arabic-Islamic stylistic component.”Footnote 40 If Arab modality and Islamic musical culture have been part of the blues and Sahelian-derived music since the advent of Islam, then, Ciucci argues, it would be erroneous to describe Sahelian-influenced music in North Africa (e.g. stanbali in Tunisia) as a (non-Arab) African import into an alien Arab-Islamic world. This latter point is worth recalling as one is increasingly hearing the argument that blues singing derives from West African Qurʾanic recitation (tajwīd).Footnote 41

Scholars who speak so confidently of “retentions” in language, dress, and instrumentation also do not consider the possibility that these cultural elements—like the very discourse surrounding Gnawa—may be “invented traditions” created or re-created by colonial or postcolonial state officials, just as the royal parasol and the sultan's garde noire were reproduced in 1912, or simply introduced by performers responding to market demands. The “Sudani” and “Bambara” terms used in rituals today could have been created for French travelers and ethnographers in the 1900s, just as now Gnawa performers invoke new spirits, and call out “Aisha Obama,” “Aisha Zaʾara” (Aisha the Blonde), and “Waka-waka Africa” to amuse Western tourists. In Christopher Witulski's Gnawa Lions, an engaging ethnography of an American Gnawa aficionado's time living in the medina of Fez, the author observes how the Gnawa lila has shifted from a sufi ritual to an “Africanized spectacle,” as spirits from other local traditions are inducted into the ceremony, alongside “outrageous acts of possession, with musicians cutting their arms with knives, drinking boiling water while possessed by Sidi Mumen,” and they are doing this “as self-identified Africans, claiming an exotic power and control over these mysterious and magical spirits from their ancient homeland, sub-Saharan Africa.”Footnote 42 Who is to say the improvising, “inventing,” and commercialization underway now was not taking place a century ago when colonial state officials had much greater interest in Gnawa street performance?

Becker does not consider these critiques. She is persuaded that the practices that gave rise to Gnawa originated in the Sahel before traveling to North Africa and the Americas, so there are numerous references to Mali, Niger, and Nigeria (and Haiti, Brazil, and Cuba) but little to other Moroccan or North African or Middle Eastern brotherhoods, thus dismissing the possibility a priori (despite her reference to Westermarck) that Gnawa practices, named jinn or spirit possession, may have come from the Arab East or the Mediterranean, or may just be native to the Maghrib. A more compelling approach would have been to compare Gnawa practices with those of other Moroccan brotherhoods in more detail. Had Becker gone beyond the “Islamic Africa” versus “New World” split screen that she (like El Hamel) adopts, she would also have seen that spirit possession is not a uniquely Sahelian phenomenon, but exists in far-flung Muslim countries like Malaysia and Indonesia.

Building on El Hamel's Black Morocco, Becker divides Moroccans into three bounded groups: Arabs, Berbers, and Blacks, as if one cannot be Arab and Black, or Black and Berber, or all three at once. (Nor is it clear why both authors ignore Moroccan Jewry). Becker even separates Moroccans into “Gnawa” versus “non-Gnawa.” She views Gnawa music as how a “largely suppressed history of enslavement” has been remembered. Who is suppressing this history? She states that the Gnawa are a quasi-sufi order at the bottom of the racial hierarchy, but no evidence is provided to show Gnawa history is suppressed more than that of the Issawa, Hamduchiyya, or Heddaoua. It is worth recalling that when Mohammed V came to power, Issawa and Hamduchiyya processions were banned, but not Gnawa.Footnote 43 Becker does not address how the Gnawa order has benefited from its links to the palace, and how state support has allowed them to endure in a way that other low-status sufi groups have not.

Becker does go beyond El Hamel in her political reading of Gnawa. For Becker, Gnawa is about black consciousness and resistance, from the black Moroccan women who refused to be photographed by French tourists a century ago to the Gnawa lila, which “not only narrates the suffering of the historically enslaved but also addresses contemporary power dynamics.” She laments the “whitening” and “Arabization” of Gnawa practices. Yet she is hard pressed to find a Gnawa musician or practitioner who shares this lament. Instead, she quotes hearsay that happens to support her thinking: “In recent years, I experienced an increasing concern among women that Gnawa authenticity should be linked explicitly to phenotypic blackness.”Footnote 44 She claims there is a debate about the spread of Gnawa practices among the general Moroccan population, “some of whose families owned slaves rather than were enslaved, [which] has served to increase debate about the meaning of “Gnawa authenticity.” Yet no Moroccan voices are quoted to support this claim. There is no doubt that the zawāyā and Gnawa-practicing families may not be benefiting from the commercialization of Gnawa music, but to say that non-black Moroccans practicing Gnawa music is “appropriation” requires much more explication. Becker would first have to show that there are music, styles, and ideas unique only to Gnawa culture in Morocco and not present in other zawāyā. (One could very well argue that the guembri, the references to slavery, the four-take qraqeb rhythm are unique to Gnawa, but that still begs the question: Did these characteristics come from southeast Morocco or the Sahel? Did they spread from the Gnawa to other sufi orders, or vice versa?) To extend her appropriation argument, would Moroccan Arabs playing music from the Rif region, an embattled part of the population, also be appropriation? Can Moroccan Jews, a more affluent community, play rai or recite muwashshaḥ about the Prophet? Interestingly, Becker accuses young Moroccans of appropriation—“much as white musicians appropriated black music in the United States”—but says little on the Western musicians who draw on the music, and she actually praises a Danish art promoter who sells Gnawa art that he claims brings Africa to life “in all its timeless and mysterious depths.”Footnote 45 As the police's monitoring of Nass El Ghiwane showed, Gnawa music with its references to oppression can have powerful resonances among the Moroccan population. The regime's greatest worry about Gnawa music may be that—given the monarchy's slaving past—the music could become an allegory for the general population's subjugation. Yet authoritarianism and state power rarely figure into studies of Gnawa.

Becker insists on depicting Gnawa practitioners as a separate people with a distinct memory and identity, resisting Arab-Islamic hegemony. At one point, she observes oddly that “Gnawa self-identify as Muslim today,” implying that they were not Muslim or did not see themselves as such until recently. (Incidentally, this depiction of Gnawa as thinly Muslim or not really Muslim is a recurring motif in scholarly writing and liner notes, and part of their appeal to world music aficionados.) Becker does not provide the data showing a “color line” on the ground in Morocco, but she finds one in the Gnawa spiritual realm, where black spirits are separate from white ones, and where the Gnawa suffer from a Du Boisian “double consciousness.”Footnote 46 She writes that the late Mahmoud Ghania's songs are an example of Fanonian resistance against (white) hegemonic power and appropriation of his culture. The Ghanians are a celebrity Gnawa family, often interviewed in Moroccan and European media, and it is hard to find anywhere where they describe themselves as resisting power, or expressing a separate (black) consciousness. They insist that they are Moroccan and Muslim, and that Gnawa culture is for everyone. Interviewed in a recent Al Jazeera documentary titled “Gnawa—The Music of Slaves,” several members of the Ghania family talk openly about their roots in Mali, their ṭuqus (traditions) and turāth (heritage), which they would like to protect from fusion and commercialization. “Our forefathers (jdūdnā) weren't doing hip-hop and rap,” quips one of the granddaughters. And they are singularly proud of Gnawa music's rapid spread. “People are hooked today, the blacks got the whites hooked, and Gnawa spread.” The son insists the culture is not about magic, it is nothing outside religion, air, water, nature, and respect for elders. “The muʿallim must have a good heart, doesn't discriminate between people—black and white are equal. We're Muslims after all and say the shahāda.” As if responding to the American scholars who write about her, the granddaugter adds, “Some people say authentic (ḥaqīqī) Gnawa are those whose origin is in Gnawa, whose mother and father were Gnawa. We don't have this idea. They'll tell you Gnawa are black—no, there are white Gnawa. The best muʿallim here in Essaouira—Muʿallim Ahmad—was white.”Footnote 47

One regrettable through-line in the Western writing about Gnawa is an aversion to “Arabs” and Arab culture, seen as foreign, contaminating, an unwelcome layer. From the writings of Brunel to Bowles, to El Hamel's denunciations of Arabian Islam for introducing racism to North Africa, to Becker's claims that Gnawa lilas have been “Arabized” and Amazigh culture “corrupted” by Arabization, to her claim that Nass El Ghiwane adopted the guembri to protest Arab nationalism, there is this notion, a curious inversion of the “Hamitic thesis,” where anything coming from outside Africa (read: Arab East) is noxious and akin to European settlerism. Blackness in Morocco is another attempt to shoehorn Moroccan history into a transatlantic framework: thus Gnawa is a diaspora, a mode of resistance, and an ethnicity (where half-black, half-Arab children are only “socially Arab”). These are not labels that Gnawa practitioners in Morocco would use to describe themselves. M'barek Boutchichi, Morocco's most well-known Black artist, has explicitly rejected the claim that black Moroccans are a “diaspora,” one made by French colonials who envisioned the Maghrib as part of the (white) southern Mediterranean, and nowadays made by American scholars of race in North Africa. “The issue that we encounter is that any black found in Morocco is told to have come from Sub-Saharan Africa. And this is where they are wrong. I am from here. I am here.”Footnote 48

“Revalorization”

In Jean Genet in Tangier, the writer Mohamed Choukri recounts conversations he and novelist Jean Genet had in the autumn of 1969, in different cafés, when the Frenchman visited the city. Much of the talk revolved around French and Russian letters, with Choukri trying to get Genet interested in Arabic literature, asking him to read Taha Husayn and Tawfiq al-Hakim, presenting him with copies of Arabic literary magazines al-Adab and al-Maʿarif. The only “Arab” writer Genet claims to be familiar with was his friend, the Algerian writer Kateb Yacine. On the eve of Genet's departure, a Gnawa party was organized for the Frenchman, and Choukri goes with Genet and his friend the philosopher Georges Lapassade. As the musicians perform, a photographer appears, and Choukri notes a change in Genet's demeanor. “I noticed that Genet seemed delighted to be snapped with the Gnawa musicians, and annoyed whenever he was caught while talking with a European. For the first time his behavior rather put me off.”Footnote 49 In the meantime Lapassade was smoking kif (marijuana) nonstop, “moving his head in tune with the Sudanese rhythms.” Genet kept changing his seat, annoyed by his European guests.

On the way out, Genet describes the Gnawa as “wonderful.” Choukri disagrees. When Genet asks him to elaborate, the Moroccan novelist responds, “They're primitive. I hate everything primitive,” adding that he prefers the music of Mozart, Beethoven, and Tchaikovsky. Genet replies, “Well, I prefer these Gnawa we just heard. I used to be like them, myself.” Lapassade then turns to Choukri, “You simply don't realize their value.” The two Frenchmen then invited Choukri for a drink. “No, I said curtly,” writes Choukri. “I said goodbye to Genet and went my way.”

This contretemps at the end Choukri's short book on Genet, with the final straw being Genet's behavior around Gnawa, is both surprising and foreseeable. It is surprising because Choukri was no stranger to performing primitivism for foreigners, whether in his written stories about his encounters with the jinn or grotesque violence he claimed to have witnessed. But his annoyance at celebrity writers who have little interest in Moroccan literature, but are obsessed with what educated Moroccans saw as a lowbrow musical form linked to colonial minstrelsy, and backward behaviors that a modern nation needed to shed, and that Choukri himself was struggling to shed, is understandable.

This essay has tried to review a century of efforts by Western and Western-trained observers to persuade Moroccans of the “value” of Gnawa culture. The meaning of Gnawa has shifted and, with it, Morocco's cultural priorities, driven mostly by global markets, American racial politics, and Western understandings of “Islamic slavery.” The American writers’ pleas to protect Gnawa from dilution and appropriation are, as seen in Genet's exchange with Choukri, or M'barek Boutchichi's response to Western interlocuters, reminiscent of the debate between anthropologist Melville Herskovits and sociologist Franklin Frazier in Bahia about “Afro-Brazilian customs.” In the 1930s, Herskovits was championing the “survivals” of African culture (“American Negroisms”), and trying to reclaim the dignity of African practices deemed backward by the majority culture. He and other “survival” scholars would underscore the long history and explanatory value of these “Africanisms.” The Black sociologist Frazier disagreed with Herskovits on the origin and value of these practices. Their debate would play out in Bahia, Brazil. Was the matrifocal family structure in 1930s Bahia the result of slavery, or a later adjustment to poverty? In his work on the Black family in America and Brazil, Frazier downplayed the influence of African culture, arguing that social and cultural patterns were of American origin. Herskovits thought the Brazilian matrifocal family structure was a “survival” of African polygamy, whereas Frazier thought it had to more to do with contemporary Brazilian urban poverty.Footnote 50 Their perspectives depict two sides of the anti-racist struggle. Herskovits accented cultural difference and the endurance of African cultural forms, whereas Frazier emphasized universalism, and the changing nature of all cultural forms. For Herskowitz, the black person deserved respect because his culture and personality were intrinsically different, whereas Frazier thought the opposite, that the black person deserves respect because he is a human like any other. Herskowitz—who dabbled in Candomblé—preferred “authenticity” in Africanisms, seeing Africa's past as a kind of cultural grandeur necessary for liberation. Frazer was against the “stereotypical generalizations of the construction of black grandeur based on the past.”Footnote 51

There are strong echoes of the Frazier-Herskovits debate in the current American discussion around Gnawa authenticity, between those who think Gnawa culture is a Sahelian “survival” that urgently needs to be salvaged, and those who think it was born in Morocco and is not any more valuable than any other quasi-sufi order. It is ironic (or perhaps unsurprising) that a time when a campaign to dismantle Herskovits's legacy is underway at the African Studies Association (“Herskovits Must Fall”), with heightened attention to (white) American domination of “knowledge production” on Africa, American scholars are projecting Herskovits's ideas of black authenticity and retentions onto North Africa.Footnote 52

Unlike other genres, Moroccan intellectuals have yet to subject Gnawa music to a process of “re-valorization,” in part because the music is simply not valorized like other genres. But things are changing. Allan Meyers's almost fifty-year-old critique of the colonial narrative around Gnawa recently got an endorsement from Moroccan officialdom (though they did not cite him). In 2014, as part of the campaign to have UNESCO list Gnawa music as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, a Moroccan-based civic organization called Yerma Gnaoua published a collection titled Anthologie musicale des Gnaoua that includes eight compact discs (recordings of representative songs from around the kingdom), and a 200-page book, Les Gnaoua: un triple éclairage historique, anthropologique et musicologique, with contributions by leading musicologists and historians. The introduction begins with a frank question—given the “double indeterminacy, historic and geographic,” regarding the origin of the genre—“Can we write a history of the Gnawa?”Footnote 53 The subsequent chapters are (sadly) peppered with references to Westermarck and Pâques: the introduction, in fact, frames the book around Pâques's claim that across North and West Africa lies one “fundamentally homogenous civilization”—a statement that accords with the makhzen's (Moroccan state) ideology. The authors address Gnawa practices from several angles. Anthropologist Abdelhay Diouri describes how Gnawa rituals have changed since the 1970s, and how nowadays black Gnawa are a rarity, with adepts more likely to be lighter-skinned or mixed. Ahmed Aydoun, a musicologist with the Ministry of Culture, reminds readers that Gnawa music was influencing the Moroccan chanson populaire starting in the 1940s, in the songs of Houcine Slaoui, Mohamed Fouiteh, and Abdelkader Rachdi, decades before American jazz artists and Nass El Ghiwane brought Gnawa rhythms to international audiences.

The most poignant intervention, however, comes from Khalid Chegraoui, a high-ranking policy analyst and historian of the Sahel. He submits that it is high time for Moroccans to challenge Western narratives and local “mythology” that claim ʿAbid al-Bukhari came from West Africa, as well as the colonial historiography that assumes black Moroccans are from the Sahel and views Saharan slavery as akin to Atlantic slavery.Footnote 54 The evidence, he says, shows incontrovertibly that dark-skinned people have lived in the southeast oases of Morocco since time immemorial. Moreover, the primary documents, specifically the palace registers of the ʿAbid al-Bukhari, demonstrate that the Black Guard's origins were “exclusively Moroccan, generally Saharan” (leur origine exclusivement marocaine, généralement saharienne), whether they were haratin, slaves, or freed slaves. With this evidence in mind, he suggests (echoing Westermarck) that the roots of the Gnawa, “the formation of tagnaouit,” may lie in Morocco's southeast, rather than in West Africa. What has made it hard for Morocco to confront its racial “demons,” its history of slavery, writes Chegraoui, is not only the hegemony of colonial and Western perspectives on trans-Saharan slavery, but racist popular attitudes in Moroccan society and the fact that slavery was never officially abolished by the Moroccan state. Such a racial reckoning, he concludes, is urgently needed to reconcile Morocco with Africa, and to fulfill the late King Hassan II's vision of the sharifian kingdom as a tree whose roots lie deep in Africa, and whose branches reach Europe.