INTRODUCTION

Expanding literature has supplied new research in an effort to make women visible in the mining sector in American and European historiography. Feminist historians studied the exclusion of women from the Central European mines as early as the eighteenth century because of organizational and technological changes in mining processes and the transformation of independent miners into wage workers at large mining firms.Footnote 1 The second wave of women's exclusion from work underground emerged from the mid-nineteenth century, related to the introduction of protective labour legislation and restrictions of female participation in the labour market.Footnote 2 The idea of home and motherhood was invoked to exclude women from the labour market in the Western world.Footnote 3 To date, research has focused on women's work and women's collective action in the mines, on daily life and culture in various mining communities,Footnote 4 and on comparisons of characteristics of migrant labour by male miners and female textile workers.Footnote 5 Gender relations in the mines, women's work, and activism in different parts of the world have been explored in connection with cultural arrangements and the emerging colonial and industrial capitalist system from the eighteenth century.Footnote 6 Feminist economic geography has also questioned why men are taken for granted as industrial workers and miners and has revealed women's agency in mining, especially in informal activities in the Global South.Footnote 7

To date, research on work in the mines in Greece has ignored the significance of gender in the workplace, since mining is associated exclusively with male labour. As such, it is considered, indirectly, not subject to gender relations in the Global South.Footnote 8 By the 1990s, however, feminist scholars already demonstrated that gender relations in the workplace are not related exclusively to the participation of women in the labour force; the identity of male workers is structured in relation to gender identities, which affect and are affected by employment.Footnote 9 As an analytical category, gender shapes all approaches aiming to historicize the structure of gender difference and hierarchical relationships of power between men and women.

Using the analytical framework of gender in the history of Greek mines, in this article I will provide an account of the complex social relations inside mining communities and argue that gender relations are comprised in the division of labour in the workplace, as well as in family divisions of labour in mining communities. These gender and family relations were significant in the formation of labour markets, in labour relations, and in the division of labour in the mines and at home. European historians have already identified the family as a unit of production, highlighted the issue of unpaid family work, focused on the participation of spouses and children in the household economy, and explored the diversity of adaptive family economies in times of crisis.Footnote 10 Based on the assumptions that: (a) the family is not a homogeneous working unit but, on the contrary, is marked by the division of labour according to gender and age; and (b) labour by women and children in the family was crucial for production and reproduction, despite being regarded as supplementary, the article examines the intersection between gender and family in labour in the Greek mines from 1860 to 1940.

In the first part, I briefly describe the character and general economic development of the Greek mining industry; in the second, I examine migration trajectories of the miners and labour control regarding family and gender relations; in the third, I focus on gender-based division of labour and family in the mines.

The sources used are diverse: official publications of the Mines Inspectorate and the Mines and Industrial Censuses (1903–1937); the Greek Miners’ Fund Archive; British and French consular reports; various economic and technical reports from experts (from the Archives of the renowned École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, the Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece, and private technical archives); literature and narratives; and local press from mining regions. I have also used the important but incomplete Archive of the Seriphos Mines (1905–1927).

CHARACTER AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREEK MINING INDUSTRY

Mining activity in modern Greece started to be carried out systematically in the 1860s. In the second half of the nineteenth century, important mining developments took place in Greece, especially in the region of Lavreotiki, the islands of Cyclades, and on Euboea Island, where iron ores, lead, zinc, magnesite, and lignite were mined. Iron and manganese ores were mined in the Cyclades (Seriphos, Kythnos, Siphnos, Melos) and in the region of Lokris (Larymna), magnesite was mined in Euboea (Limni, Mantoudi), lignite was mined on Euboea Island (Kymi, Aliveri) and Oropos (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The main mining regions in Greece, 1860–1940 (borders of 1913).

Lignite was used for fuel in Greece, while the majority of the rest of the ores was exported raw (or semi-processed, after metallurgical processing) abroad. From the nineteenth century to 1940, mined ores were generally exported as raw materials to international markets and, in limited measure, metallurgy products.Footnote 11

The mines were owned by natural persons or companies, some representing European interests (such as the Compagnie Française des Mines de Laurium, CFML, set up in Paris in 1875). Around 1900, the CFML controlled a significant share of Greek mining activity, wholly owning or leasing mines and purchasing the mining output of many small enterprises. Frequently, mines were not operated by the natural person or company that owned the right to do so but were rented out to third parties or given to contractors to operate. Usually, the party operating the mine (contractor or lessee), having paid for this right, did not engage in investments or in methodical scientific exploration of the mine. Large and small enterprises and even some notable companies, such as the Public Municipal Works Company for the mining and package of the magnesite at Mantoudi, practised leasing and contractual operation.Footnote 12 Mining enterprises of every kind throughout the country were accustomed to this system of operating their mines: “Commissioning mining and transportation of the lignite from a contractor is the safest means for intensive operation”, admitted lignite mine entrepreneurs in 1919,Footnote 13 at a time when they were looking for ways to reduce production costs. Increasing labour productivity was also a basic aim of the entrepreneurs who adopted this specific form of labour organization,Footnote 14 which, moreover, was also adopted by the Greek state, to operate the state-owned mines at a profit.

Most mines were small-scale enterprises, where operations were carried out by primitive mining techniques, without an ore-processing plant and with a small-batch furnace operation with a low daily output. In 1940, only a few mines were equipped with modern mechanical means of extraction and loading or with grinding plants.Footnote 15 Renting mines and sub-contracting, by means of which operations were carried out, were particularly common. The practice, however, seriously curtailed the scope for capital accumulation. The “operator” of a mine, whether a contractor or a lessee, had to pay rent and did not invest in installations or equipment; the operator did not ensure methodical, scientific operation of the mine.Footnote 16

The absence of technical supervision by the state, the dearth of research and specific knowledge about deposits, and the inadequacy of technical education impeded rational operation of the mines.Footnote 17 Consequently, mining enterprises were based mainly on the use of cheap labour. Using this cheap labour accommodated price fluctuations on the ores market, sometimes yielding excessive profit margins and sometimes rendering ongoing productive activity unprofitable. Relying on cheap labour instead of on technological renewal and rational organization of production had the advantage that in periods of declining prices, production was reduced and the enterprise protected from serious losses. The result, however, was cyclical high unemployment and underemployment and a consequent reduction in workers’ incomes, depending on business cycles.Footnote 18

MIGRATION TRAJECTORIES, CONTROL OF LABOUR AND GENDER

As has been observed in many cases worldwide, “an urgent quest for labour characterises the history of mining everywhere and drove varying constellations of labour relations”.Footnote 19 Early migration by skilled groups of miners to use and apply mining skills in the new mining districts was increased by waves of inexperienced migrants, while diverse recruitment systems were used. The importance of oscillating migrant seasonal workers in the mines has been considered in several studies.Footnote 20

During the opening phase of mining activity in the Greek state in the 1860s and 1870s, a skilled workforce had to be imported from abroad to the mining areas of Greece, if extraction was to begin. In the mines of Lavrion, Seriphos, Siphnos, and Kymi, skilled miners from Spain, Italy, Montenegro, and Germany worked in the 1860s–1880s.Footnote 21 Very early on, the labour market in the mines gradually took shape, together with the first operations. As early as the 1880s, work in the mines gave rise to a flow of internal migration: inexperienced workers from the islands and mountain regions moved, usually without their families, to places of mining activity to work in dependent labour relations. In 1890, in the (Greek) Lavrion Metal Works Company at Lavrion, only 1.3 per cent of the 1,500 employees was non-Greek. The rest originated from: Laconia (27 per cent); Phokida (23 per cent); Euboea (12.5 per cent); the Cyclades (11.4 per cent); the islands of the Argosaronic Gulf (3.5 per cent); Epirus (3.3 per cent); the Peloponnese (apart from Laconia, 3.1 per cent); Attica (3 per cent); Athens (2.6 per cent); Phthiotida (1.4 per cent); and Macedonia (1.1 per cent). In the CFML in 1880–1890, the miners were Italians or migrants from the Cyclades, Laconia, Euboea, Crete, Phokida, and the region of Lavreotiki.Footnote 22 In 1896–1900, about 8,500–9,500 workers (adults and children of both sexes) were working in the mines and the metallurgy of Lavrion and Grammatiko.Footnote 23 These numbers of 8,500–9,500 workers in the mines and metallurgy plants represent a substantial share of the labour force, considering that Greece had a total population of 2,443,806 in 1896, and that around 15,000–16,000 were employed in industry in 1900 (Table 1).Footnote 24

Table 1. Workers in mines: metallurgy plants in Lavrion and Grammatiko (Attica region), 1896–1900.

Source: Ανδρέας Κορδέλλας, Ο μεταλλευτικός πλούτος και αι αλυκαί της Ελλάδος (Athens, 1902), p. 59.

Similar inflows of workers are observable in mining regions in phases of intensive – and more or less systematic – mining activity, whereas demographic outflows are noted in periods of recession,Footnote 25 when miners move elsewhere in search of work. In the early twentieth century, Lavrion, the largest mining and metallurgy centre, was in a state of crisis, characterized by a reduction in jobs and in the number of personnel.Footnote 26 The emigration trend from Lavrion and from the islands in recession, is clear from the first decade of the twentieth century until the interwar period. Miners from Melos Island migrated to Seriphos, Lavrion, Larymna, or the Aliveri lignite mines,Footnote 27 while miners from Melos and Lavrion headed for the mining regions of France in the 1910s–1930s, often with their families.Footnote 28

Literature on migration has explained how migration does not refer to the stereotypical practice of men migrating first, while wives and children join them later on; individuals, men and women alike, migrate from one place to another “via a set of social arrangements”, as part of chain migration (or migration networks or systems).Footnote 29 Migration as an interaction of individual conditions, family dynamics, life courses, gender differences in work and earnings, and larger economic cycles involves paid and unpaid gender labour at both ends of the migratory trajectories.

Migration by workers to the Greek mines could be perceived as a diversified response to economic crisis. As historical research has shown, agricultural and labouring families in Greece devised strategies for using the time of their members to do jobs essential for reproduction of the family and to perform minor agricultural production or tasks in workshops and shops in town and to incorporate their members in the labour markets. These family strategies derived from the hierarchical organization of the family and the gender-based and family division of labour.Footnote 30

Family relationships figured prominently in the migration movements from one mining region to the other in times of crisis. In mines in different islands and regions, members of the same family often worked together. The family of Nicolas Rokakis from Crete illustrates these movements. Nicolas Rokakis was born in Crete in 1884 and at the age of seventeen moved to Seriphos, where he worked as a miner from 1901 to 1916. His first son, Manolis, was born in 1903 in Crete, where the family still lives. Two other sons, Lefteris and Petros, were born on Seriphos, in 1912 and 1916, respectively, where Rokakis lived with his wife, after she left Crete. Their fourth son, Aristeidis, was born in 1920 in the coalmining area of Oropos, where the whole family moved after a short stay in Lavrion (in 1916–1917). Nicolas worked in the coalmines of Oropos as a contractor from 1918 to 1936 and as foreman and contractor during the Occupation (1941–1944) and until 1946. His four sons all worked as miners in the coalmining area of Oropos from the ages of thirteen to fourteen. They worked there during the interwar period and during World War II. The wife of Nicolas, Maria (born in Crete in 1888), was pivotal, giving birth and caring for this family of miners.Footnote 31 The case of the Rokakis family from Crete reflects an exceptional gender outline of family migration for economic reasons, in which the adult man, as head of the family and breadwinner, goes ahead in search of work and opportunities and is followed by the other members, if circumstances permit. In the Lavrion and Seriphos mines we observe similar mining family itineraries: families who worked together came from the mainland or the islands. In all cases, family relationships strongly influenced participation in the mining labour market and organization of work in the mines.Footnote 32

Worker migration is influenced by gender in two other ways. On the one hand, migrating workers who had agricultural smallholdings often supplemented their meagre income from farming by working in the mines. This held true for the workers from Lidoriki (in the Phokida region), who, around 1880, worked in the Lavrion mines only in winter, while in summer “they return to their farming tasks”.Footnote 33

Male miners, regardless of whether they migrated on an annual basis, had families (parents, brothers and sisters, wives, children) settled in their places of origin. The members of these families, particularly the women (of any age) and children, were engaged in farming / animal husbandry back home, while the menfolk were away. According to the autobiographical narrative of a communist miner at Lavrion, who later became a writer and who seeks to describe the wretched conditions and the starvation wages the miners were paid:

Most of those who come here aim to work for three or four years – no more – to save some money and return in due course to where they come from. They too have some neat little cottage home and a little woman waiting for them. And some little one that they left behind this tall is now a full-grown man […]. But somehow for months the grocery bills have left you unable to save anything. And it hasn't been possible to send home even what is needed for bread. So, then they go in for another one or two-year stint, no one is young anymore, that was a long time ago. But they will go back. They will go back without a doubt. Otherwise, life would have no meaning here. Yes.Footnote 34

The passage quoted indicates that there was at least one company store at Lavrion, where the miners were required to purchase food and basic supplies, probably following the truck system practice known in many mining areas and intended to bind the workers to the mine.Footnote 35 The miner-writer undoubtedly embellishes family life in the distant, small, neatly-kept household and mentions nothing about the work done by women and children within the framework of Greek farming families. The miner is described as wanting to send money back home but unable to do so because of his debts to the grocer at the mine. Even if, in this imaginary account, the miner-writer wished to contribute exclusively to the family income as the breadwinner, conditions did not allow it. The farm family subsists without systematic support from the miner's wages, cultivating the land, raising livestock, manufacturing market-oriented textile products. The complementarity of wages from work in the mines, farming for home consumption, and the proceeds from any production for commerce was characteristic of farm families in Europe, Greece, and the Mediterranean.Footnote 36

Worker migration to the mines has an additional gender dimension relating to control of labour and the paternalistic policy of the companies, which had an interest in stabilizing the workforce in mining areas.Footnote 37 At Lavrion, the three mining enterprises established in stages from the 1860s a company town, with the first settlements for workers; they set up schools, hospitals, and churches, while a market was organized in the central piazza. In 1866–1870, the first industrial settlement, “Spaniolika” (settlement of the Spaniards), was set up to house the specialized furnace workers seconded from Spain.Footnote 38 The French company built the settlement at Kyprianos in 1876–1880 to house clerical staff and workers with their families.Footnote 39 As the town developed, new working-class neighbourhoods were shaped by the internal migrants, often by unauthorized construction (Santorineika, Maniatika, etc.), while many poor internal migrants were accommodated in improvised huts and hovels at Kamariza, Plaka, Souriza, and in other areas of Lavreotiki, near the entrances to the mining pits, in very squalid conditions.Footnote 40 The ekistic squalor of the areas of unauthorized building and of the miners’ hovels contrasted sharply with the well-ventilated, healthy housing constructed for the families by companies at Kyprianos and Spaniolika. At Spaniolika, workers “find in their homes, after their toil, the care and joys of the family, so necessary to the moral development of the working classes”.Footnote 41

In the late nineteenth and first decade of the twentieth century, housing and medical-pharmaceutical care were supplied to workers and a school, a girls’ school, churches, and a hospital opened by the French Seriphos-Spiliazeza company on Seriphos with the intention of reducing turnover among miners and strengthening their family ties.Footnote 42 In the first decade of the twentieth century, Seriphos-Spiliazeza company directors Emil and Georg Grohmann are described as kind and caring businessmen who took an interest in the miners’ families. “Every kind of philanthropy is shown to the workers and their families by the manager of the mines, and a pension is awarded to disabled workers and to their families after the death of a father who was employed there.”Footnote 43 The widows of the workers or their daughters received occasional cash benefits to deal with difficulties,Footnote 44 while scholarships for high school education were awarded to some good students who were sons of miners. One young man, the son of a miner or contractor, Ioannis Synodinos, studied mineralogy at Freiburg at the expense of the management.Footnote 45

As noted above, the paternalism of the mining enterprises was aimed not only at stabilizing the workforce, but also at bringing about an attractive family environment to help miners come to terms with the harsh working conditions and encourage them to stay and spend their leisure time at their home with their families.Footnote 46

GENDER-BASED DIVISION OF LABOUR AND FAMILY

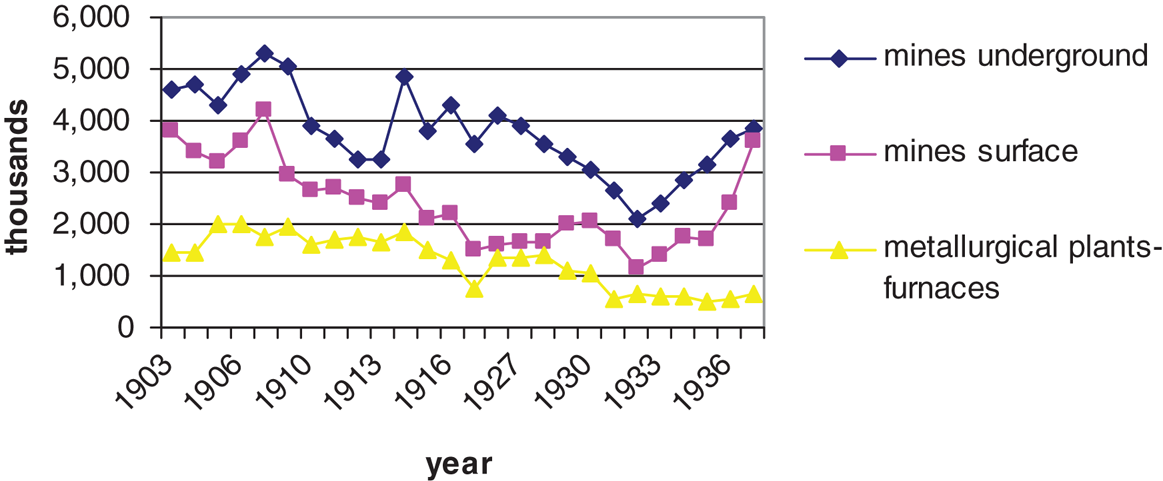

According to official statistical data, at the beginning of the twentieth century, about 10,000–11,000 workers were employed in the mining companies, among them 300–500 women, who worked on the surface (Figure 2). While the number of female workers was rather low, the censuses presumably underestimate some of women's work.

Figure 2. Total male–female workforce in mines, lignite mines, metallurgy plants, 1903–1937.

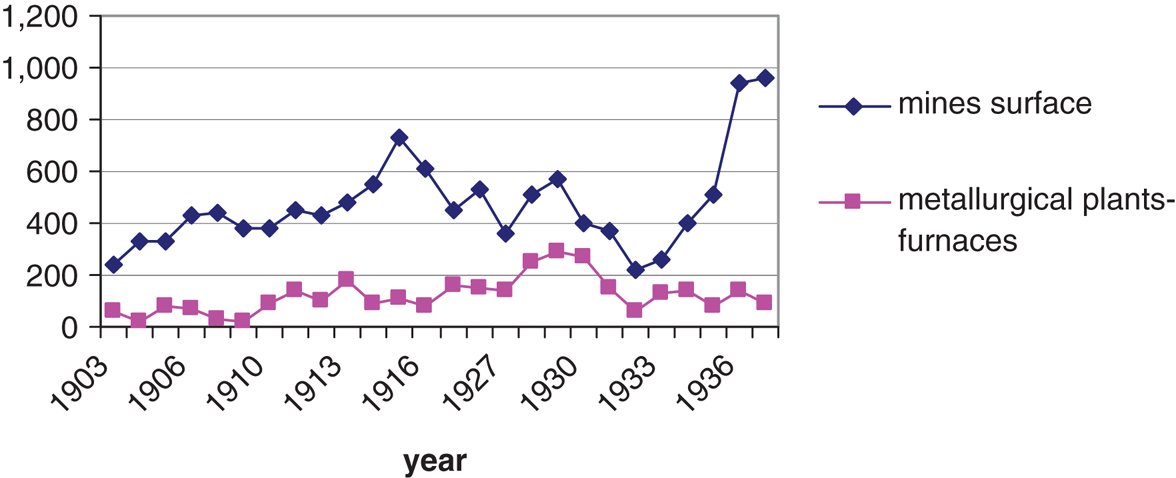

In the years that followed until World War II, the total workforce (male-female) declined to about 5,000–8,000 workers, depending on the business cycles.Footnote 47 The male workforce (underground, on the surface, and in metallurgy plants) was reduced in 1909–1913 and in times of interwar crisis (1928–1935) (Figure 3). Notwithstanding the reduction in the total and male workforce, women's involvement in the mines increased from 1910 onwards for two main reasons: (a) the extended absence of men at the military fronts in wartime (the Balkan Wars 1912–1914, World War I 1914–1918, the military campaign in Asia Minor 1918–1922) and (b) the more general crisis in the mining and metallurgy sector in the interwar years. Women's work was only on the surface (extracting, selecting, and washing ores). Because of the crisis in the mining sector, enterprises invested more in female manual work in selecting and washing ores to add more value in the export-oriented ores (Figures 4 and 5). According to the available sources on earlier periods, from the nineteenth century until 1918, women worked in the mines for lower wages than men.Footnote 48 Cheaper female labour could be an obvious explanation for the entrepreneurial decision to employ women in many mining tasks during the interwar years.

Figure 5. Male and female workforce in the lignite mines, 1925–1937.

The age composition of the workforce in the mines in 1930 reflects a relatively balanced age distribution among male workers from 15 to 70, with the greatest concentrations in the age bracket of 15 to 59. The largest percentage of male workers are those over 30 (57 per cent). On the other hand, women are concentrated mainly in the 15–24 age group, while the share of women in the 10–14 and 25–59 brackets is lower than that of men. The women working in the mines were therefore younger than the men there. The position of women in the division of labour in the mines in relation to their age clearly reflected their life cycle: the young, supposedly mostly unmarried category of 15–19 years was by far the highest percentage (51.8 per cent), while among those reaching marriageable age, from around the age of 20, the number drops spectacularly (Table 2). The position of women in the division of labour in the mines was presumably linked to their position in the division of labour in the family, first as daughters and later, primarily, as mothers and wives. On the other hand, the physical strength required in labour-intensive mining enterprises explains the presence of men over thirty and the low share of boys (ages 10–19), who lacked the physical maturity for work in the mines. The large share of men over thirty in the mines gave the sector features of a more permanent “male” job. Overall, family strategies may be assumed to have influenced men and women entering and remaining at jobs in the mines, while they were linked with life cycles as well.

Table 2. Composition of the workforce by gender and age in mines and quarries, 1930 (%).

Source: Ministère de l’Économie Nationale, Statistique Générale de la Grèce, Recensement des employés et ouvriers des entreprises industrielles et commerciales et relevé des salaires effectués en Septembre 1930. Comparaison avec des salariés plus anciens et plus récents (Athens, 1940), pp. 102–105.

In the 1910s, women were employed in the mines and metallurgical factories of the CFML and in (the Greek) Lavrion Metal Works Company, in the Anglo-Greek Magnesite Company (Limni, Chalkida), and in the Société Hellénique des Mines (Mantoudi, Kymi), as well as in the mines of the Société des Mines de Skyros and the Société Hellénique des Mines Lokris (Larymna). In the 1920s, women were also employed in the mines of the Société Française Seriphos-Spiliazeza (Seriphos), the Société Financière de Grèce (Mantoudi), in the lignite mines of the Hellenic Chemical Products and Fertilisers Company (Milessi, near Oropos, Coroni), and in the lignite mines of Euboea (Aliveri, Kymi). In the 1930s, women were also employed in the Bauxites du Parnasse and in those of the Hellenic Chemical Products and Fertilisers Company (Stratoniki, Aghioi Theodoroi, Hermioni).Footnote 49

In the mines, men and women did not do the same jobs; on the contrary, the division of labour by gender was clear. Men were miners, labourers, smelters, smelter's helpers, and foremen. Extraction jobs in the pits were done by the men. Ores were transported by both men and women, although such work was assessed differently, depending on the gender of the worker. Smelters, supervisors, and foremen were all men. In the mines where women worked, women did the jobs on the surface that involved breaking and sorting the ores. Women and children of both sexes were employed in extraction and selection of ores and in the water separation plant at Lavrion.Footnote 50 In the case of magnesite fire-bricks manufacture in Euboea (Figure 6), young children of both sexes were used in the 1890s “for carrying bricks and stone and in chipping the visibly defective portions off the lumps of ore”.Footnote 51Table 3 shows the number of workers and the division of labour in the (Greek) Lavrion Metal Works Company in 1877–1878: men, women, and children of both sexes extracted, collected, and sorted the ores, while only men worked in transporting, processing, smelting, and operating and maintaining the machinery.

Figure 6. Men and women workers involved in transportation and loading of the magnesite. Limni, Euboea, early twentieth century.

Table 3. Division of labour in the (Greek) Lavrion Metal Works Company, 1878.

Source: Ανδρέας Κορδέλλας, Η Ελλάς εξεταζομένη γεωλογικώς και ορυκτολογικώς (Athens, 1878), p. 134.

The absence of reliable statistical data precludes measuring real wages over time. Nevertheless, I have concentrated all the scattered data on wages and the division of labour at Lavrion in 1877 (Table 4) and Melos in 1893 (Table 5). Everywhere, women appear to have been paid much less than men. The statement of the French Consul in Greece in 1918 that “les moins payés sont les mineurs: 6 drachmes au maximum [in the lignite mines] à Kymi,” and that “la femme est payée beaucoup moins cher. Dans les mines, elle gagne de 2 à 2.5 drachmes”Footnote 52 shows the main trend in wages.

Table 4. Wages and division of labour in Lavrion, 1877.

Source: Κορδέλλας, Η Ελλάς εξεταζομένη, p. 86.

Table 5. Wages and division of labour in manganese and sulphur mines in Melos, 1893.

Source: FO, Miscellaneous Series, No 303. Reports on Subjects of General and Commercial Interest, Report on the Mineral Resources of the Island of Milo (with Plan) (London, 1893), p. 4.

According to the available sources, miners, timber men, scalers, smelters, and their assistants, labourers, women, and children worked in the mines. In classifications from contemporary sources, the combination of categorizations based on the nature of the job and specialization with categorizations of biological type (“women”, “children”) is striking.Footnote 53 It is from the same logic of the classification in the sources that the “self-evident” conclusion emerges that women and children were defined as members of a biological category and included in the labour market as such. By contrast, the biological category of “men” is not recorded, since they – equally “self-evidently” – constituted the necessary occupational categories in the mines. As selection and washing of the ores are deemed women's and children's work, describing these tasks seems useless.Footnote 54 The division of labour in the mines was therefore based on what could be described as “skilled” work, which was carried out by men; “unskilled” work was carried out by women and children. By the end of the nineteenth century, in the mines on Melos, women and children constituted an “unskilled” labour force, employed “in cleaning the smaller particles of the mineral, […] in transporting the material for shipment”.Footnote 55 Within a dynamic historical framework of social relations, work was ranked as unskilled or skilled according to gender and age. The concept of occupational specialization undoubtedly relates to both the existent levels of ability and skill required for specific jobs in the workplace and the productive process, while at the same time gender and age were crucial factors in the social construction of skill.Footnote 56

Women's labour in the mines was marginal and undervalued according to the gender hierarchies and the technical organization of labour. Women were present in the mines as workers, but also as wives and mothers and housekeepers. In the reproductive sphere, unpaid women's work (involving childcare, cooking, housekeeping, preparing baths, cleaning, washing clothes, sewing, etc.) was essential for the subsistence economy and the well-being of the mining families. Waged work in informal activities (sewing, lodging, etc.) was also an option for women in mining regions.Footnote 57

In 1910, the law “On Mines” was the first law in Greece regulating work by women and children in mines. The law prohibited employment of women and children in jobs underground and night work in the mines. Children under twelve could work only in sorting the ores.Footnote 58

At Lavrion in the 1890s and on Seriphos in the early twentieth century, a great many accidents in mines seem to have been inextricably linked to defective organization of labour from a technical point of view, as evidenced both by the reports of engineers and claims by workers’ associations.Footnote 59 The high percentage of accidents and, more generally, the acknowledgement in 1921, of the “laborious and unhealthy” conditions prevailing in the extraction workplace led work in the mines to be seen as dangerous and risky.Footnote 60 This qualification as risky matched the social model of masculinity in Greece. Male identity and masculinity were structured in relation to social features attributed to the “daring” and “risk-taking” nature of male miners. Although relating the construct of masculine identity in the workplace to risky and harsh conditions is not particular to the mining sector, the special content of miners’ work and the concept of “skilled labour” in the mine are not irrelevant to such a construct. The institutionalized exclusion of women from underground jobs in 1910 was conducive to forming this male identity.

CONCLUSION

Gradually, from the nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century, a specialized labour market for mining was formed based on occupational specialization in specific areas (Lavrion, Euboea, Cyclades, Chalkidiki). The demographic surplus in these areas aligned with mining cycles, leading from time to time to miners’ mobility and internal migration for new work. Men and women workers in the mines constitute a proletariat in the making, which often retained strong ties to agriculture, chiefly because of the flexibility and irregularity of the work and the low wages in mining enterprises. However, the workforce of the mines was not constantly transitory and temporary; nor was it permanently connected to the agricultural economy. Evidence is available that a stable and permanent mining proletariat in the country's systematic mining operations quickly emerged from the end of nineteenth century and endured into the interwar period.

Migration by miners was supported by family and extended family relationships and ethno-topical networks. Family and gender relationships contributed to migration, formation of the mining labour market, and organization of work in the mines. Women's paid and especially unpaid labour was important for the well-being of the families of workers in the Greek mines at both ends of the migratory trajectories, in the places of origin (such as Phokida, Laconia, etc.) and in the mining areas (such as Lavrion, Seriphos).

Various paternalistic practices in mining areas (especially the provision of housing, education, and healthcare) served to bring about harmonious labour relations, binding workers to the enterprise and securing stability and continuity at work. These practices of enterprises in mining areas and company towns inspired a series of gender-related practices for management of personnel, which, on the one hand, ensured gender-based organization of workplaces and, on the other, produced “cultural meanings” as to gender relations and relations between male and female workers and employers. Paternalist entrepreneurs regarded reproductive care for the mining families through unpaid work by women as crucial for mining production.

The division of labour in the mines depended not only on the technical requirements of production in the work process. Gender-based division of labour meant that men and women of all ages performed different tasks and were paid differently. Remuneration for women's labour was far lower than for men's labour. The reasons for implementing this gender-based division of labour were not only economic and were not concerned exclusively with reducing cost. Rather, the content of the work and the concept of “skilled labour” took on multiple meanings. “Skilled work” was assigned meanings determined by the gendered social relations of power (e.g. the “risk-taking” character of male miners and the risks they undertook in work underground, the “ancillary” jobs performed by women and children in extraction at the surface and sorting). Selection and washing of minerals were indispensable jobs that added value to the export-oriented mining products, although these jobs were perceived as “ancillary” or “unskilled”, as they were performed by women and children.

Women worked in the mines, as wage workers, piece-work labour, or contractors, primarily performing tasks on the surface. The share of women in the total workforce in the mines augmented in periods of crisis, when employers needed to invest in female manual work for selection and washing of ores to add value to them. No evidence indicates that the gender-based division of labour in the mines was abandoned at some points, such as in times of crisis.

The large share of young women workers in the mines aged fifteen to nineteen is explained by the life cycles of women and their mobility after age twenty because of marriage and maternity. These data might lead to the conclusion that women's work in the mines was clearly connected to their life cycle. Further research could explore closer connections between female work in the mines, migration patterns, family strategies, and women's life cycles.

Women were also active in the mining/agricultural communities as mothers, wives, and caregivers for the whole family. They worked at home in the informal sector and in agricultural jobs.

Decisions about migration and the different options for participating in labour markets were taken by the members of the families. Overall, mining families devised a multitude of strategies in response to economic crises, unemployment, underemployment, and reduction of family income. The unequal participation of men and women from mining families in the diverse labour markets highlights gender relations within working families.

This article reports the female presence in the Greek mines, while trying to underline the importance of gender in the workplace and in the mining families. Further research could explore more concretely case studies or specific topics, such as family migration to the mines, daily lives of women in the mining communities or in the places of origin, women's activism, or the construct of masculinity for men working in the mines. Other research might also examine more comparative or transnational approaches (e.g. in the Mediterranean) or raise questions on levels of analysis. In any case, the gender perspective in the history of labour in the mines offers social historians a broad field for methodological and theoretical reflection.