1 Judging by video link

Since the travelling justices of Henry II's court, judges have generally performed their role in the same spatial arena as all other parties in the case, including the public. The place of justice, ‘the court’, has been synonymous with the location of the judge.Footnote 1 With the introduction of video conferencing into court proceedings from the late 1980s, this relationship has dramatically shifted.Footnote 2 The use of cameras, television screens, microphones and speakers linked by Internet or telephone connections has allowed judges to appear to parties on screen and to preside over matters remotely. It is now possible for a judge to sit in one location and for every other party in the proceeding to be elsewhere. As a result, court proceedings and the image of the presiding judge are no longer confined to a single discrete courtroom, but have become a spatially distributed event, extending the boundary of the court to other buildings, such as libraries, forensic laboratories, university offices, barristers’ chambers, community centres, hospitals and police stations. Traditionally, courts have taken a very conservative position on the dissemination of judicial images on film and it has been argued that image-making and image management are important components of the judicial role (Moran, Reference Moran2013; Baum, Reference Baum2005). Given that, in many jurisdictions, the proceedings of courts are rarely broadcast on television, video conferencing has, for the first time, allowed the presence of the judge ‘sitting live’ in court to be frequently transported and transformed, and viewed in places other than the courtroom.Footnote 3

While the use of video conferencing in court proceedings has interested academics for the past thirty years, many expressing concerns (Mulcahy, Reference Mulcahy2008; Poulin, Reference Poulin2004), scholarship has been largely focused on specific uses of this technology – most notably on its use for taking evidence from children and vulnerable witnesses (e.g. Davies and Noon, Reference Davies and Noon1991; Cashmore and De Haas, Reference Cashmore and De1992; Taylor and Joudo, Reference Taylor and Joudo2005). Attention has also been given to the use of video links for facilitating the appearance of defendants (McKay, Reference McKay2018; Diamond et al., Reference Diamond2010; Poulin, Reference Poulin2004) and for its use in immigration hearings (Haas, Reference Haas2006–07; Federman, Reference Federman2006). Far less consideration has been given to its use for other types of participants, such as experts (but see Wallace, Reference Wallace2011; Reference Wallace2013), even less on the implications of its use for lawyers and judges. This is surprising, given that they are generally key participants in court video links.

Recent research does, however, hint at the potentially transformative impact that the introduction of this courtroom technology might have on the judiciary. Lanzara and Patriotta's (Reference Lanzara and Patriotta2001) study identified that work practices of judges were being challenged with the shift from audio transcription to video-cassette-recording technologies. Licoppe and Dumoulin's (Reference Licoppe and Dumoulin2010) study revealed ways in which traditional court rituals were being disrupted by the introduction of court video links.Footnote 4 Others have shone a light on the unique position of the judge in ‘an information environment that is more intensive, more extensive and less controllable than it was in the past’ (Thompson, Reference Thompson2005, p. 48) and in which cameras have traditionally been kept out of courts.Footnote 5 In light of this, Moran's recent work (Reference Moran2016) on the broadcasting of judgments of the UK Supreme Court identifies how the crafting of the judicial image for consumption outside of that court environment is informed by a number of unwritten rules and principles, the facilitation of the technology, as well as court policies and frameworks. We found, however, far less conscious attention being given to the crafting of the judicial image in video-linked encounters in the courts we studied.

Reporting on a three-year empirical study on the use of video links in Australian courts, we argue that their introduction has had a profound impact on the production, management and consumption of judicial images, and that has implications for the judge's in-court role – both as traditionally conceived and in practising new types of therapeutic jurisprudence that require increased emphasis on engagement with other court participants. We argue that fundamental judicial tasks, such as monitoring participant behaviour, exercising control over proceedings, ensuring a fair trial, facilitating witness testimony and conveying and demonstrating community-held values, are transformed when performed via video link. How the judge appears to other court participants, how judicial rituals operate and how the technological and spatial architecture that underpins the distributed courtroom works are all vitally important in presenting the judge as authoritative and the court as legitimate. We argue that the judge has less direct control over the management of the distributed courtroom and over the production of their image than is the case in the physical courtroom, and that these two shifts have implications for the reception of the judge's image and even, perhaps, how judges view the performance of their role.

2 The role and image of the judge in court

The work undertaken by a judge in a courtroom is the most publicly visible aspect of their role and helps to create and sustain their cultural image. The judge embodies the authority of the court, as an adjudicator and as the authority responsible for managing the court and the other courtroom participants. Any dissonance between the image of the judge and the nature of their role potentially detracts from their effectiveness because courts, unlike other branches of government, essentially rely on public acceptance of their legitimacy.

The nature of the judge's role will vary, depending on the jurisdiction and the nature of the work allocated to them, but may consist of conducting various types of preliminary hearings, taking pleas of guilty to criminal charges, presiding over trials, sentencing offenders, delivering rulings or judgments and hearing appeals. In an adversarial trial, the judge must control and monitor proceedings to ensure that the rules of evidence and procedure are followed (Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2013, p. 6) and that parties, witnesses, lawyers, jurors, media and members of the public behave appropriately in the courtroom. The judge decides what evidence is admissible and how it is given, such as whether in the form of in-court testimony or by video link. The judge may ask direct questions of a witness, although they must be careful not to interfere with the conduct of the case in doing so (Finkelstein, Reference Finkelstein2011, p. 138).Footnote 6 A judge who has a fact-finding role will listen to the evidence and draw conclusions from it in order to make their findings and ultimate decision. That may involve forming impressions of a witness (as to their credibility or reliability) and determining the value that should be attached to their evidence, although it has been acknowledged that demeanour is not always a reliable guide to determine whether or not a witness is telling the truth (Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2013, p. 6). In a jury trial, the judge's role is to sum up the facts for the jury and direct them as to the law that they must apply in reaching their verdict (Kiefel, Reference Kiefel2013, p. 5). The judicial role in the courtroom also involves communication with the parties or their legal representatives – hearing submissions on procedural issues, points of law and final submissions, directing questions to those making those submissions, as well as delivering rulings and judgments.

In Weberian terms, judges’ performance or enactment of their authority in their courtroom role reinforces the law's claim to legitimacy. Traditionally, this has been hypothesised as requiring that the judge's primary function, when presiding over a trial, is to perform an impartial adjudication, embodying ‘impersonal, unemotional detachment’ (Roach Anleu and Mack, Reference Roach and Mack2015, pp. 1052–1053; see also Shaman, Reference Shaman1996). However, more recently, it has been argued that legitimacy also requires an assurance of procedural fairness, which, in turn, requires a degree of engagement between the judge and other courtroom participants (Tyler, Reference Tyler2003; Mack and Roach Anleu, Reference Mack and Roach Anleu2010). This may be particularly important in sentencing, where judges can employ a range of communication strategies to accomplish legitimacy, such as directing their gaze and speech directly to the defendant to create ‘a more engaged, personal encounter’ (Roach Anleu and Mack, Reference Roach and Mack2015, p. 1064). Effective judicial engagement is also a hallmark of the therapeutic and problem-solving approaches to justice implemented in some criminal courts over recent decades, largely in the sentencing phase, to address offender behaviour related to issues such as illicit drug use, mental health problems and homelessness (King et al., Reference King2014). They require a more relational approach to judicial work, where judges make greater use of their personal and interactional skills (Roach Anleu and Mack, Reference Roach and Mack2017; Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Mack and Roach2012) to secure more effective sentencing outcomes. As has been noted (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Roach and Mack2017), this development has occurred at a time when courts are also under increasing pressure to use technologies, such as video links, to improve the efficiency with which they conduct their proceedings.

Judicial appointment criteria in Australia reinforce the cultural image of the judge as embodying both neutrality and engagement. This requires the capacity to inspire and demonstrate respect, maintain authority, deal impartially, treat all persons fairly, communicate clearly and listen with patience and courtesy (AIJA, 2015). Aesthetically, clothing, court rituals and the architectural framing of the judge on the dais have historically supported this construct in a variety of ways. Official judicial dress – such as robes, but also the wigs and jabots more common in the higher courts – does more than just signal that the legal event is out-of-the-everyday. It signifies the authority of the judge to make what are, for some, life-changing pronouncements on behalf of the community and, on a more practical note, decreases the likelihood of identification of the judge outside of the court. Their elevated seating on the judicial dais also fosters a certain distance between the bench and participants. In combination, these features help to distinguish the office of the judge from the actions of a citizen randomly imposing their will on others and reinforce the legitimacy of the courts. These distinctions also help to create boundaries, as Dovey (Reference Dovey2010) contends: ‘[a]uthority relies on clear boundaries, identities and practices … the architecture of the courtroom stakes out the territorial boundaries of judicial power’ (p. 128). In the following section, we provide a background to the study in which we found that the use of video links in courts has begun to blur some of these boundaries.

3 Video-link use in Australia: a study

This paper draws upon the findings of an empirical research project that examined the trend towards using audio-visual links in Australian court proceedings, with the aim of improving communication between court participants.Footnote 7 It employed a mixed-methods approach, combining field research, surveys, interviews and experimental work. Some methods were directed to more specific issues within the general field of inquiry. The surveys focused principally on the extent to which video links were used to take forensic evidence, while the experimental work sought to examine the impact of the use of video links on the experience of witnesses and the reception of their evidence. This paper draws on data collected from the field research conducted in the form of site visits to locations from which video-link evidence was taken and in which it was received, and on data from a series of interviews conducted with key stakeholders.Footnote 8 These methods yielded a wealth of qualitative data from which the authors were able to assess the impact of the use of video links on the way that the judicial role is performed and judicial authority is enacted.

Site visits were conducted principally in two Australian jurisdictions that were industry partners in this project – Victoria and Western Australia – which both make extensive use of video links. A total of twenty-seven courthouses and twenty-two ‘remote sites’ were visited.Footnote 9 These were selected as representative of the wide range of spaces that might be connected using court video links. These visits, which took approximately one hour, were documented by means of notes, using criteria developed by the research team, which recorded the room's scale, size, materials and ambience, together with photographs and sketches. Where possible, photographs also included on-screen views. Inspections included the ‘remote space’ from which evidence was taken (whether a purpose-built audio-visual suite or another courtroom) and, in the case of a purpose-built facility, its entrance, waiting areas and the entrance of the building in which it was located. Further valuable insights were obtained at some sites where the research team was permitted to use the video link to interact with each other between a courtroom and a remote space. These experiences, together with the other findings from the site visits, provided important contextual information to assist in conducting the interviews and in enabling the research team to appreciate the perspectives and information offered by the interviewees.

Interviews were conducted with sixty-one stakeholders about the use of video links in courts, with participants selected via a snowballing process amongst the industry partnersFootnote 10 to the project. They included judicial officers (judges and magistrates), lawyers, court staff, architects, expert witnesses, technical support staff and remote court officers.Footnote 11 We used a semi-structured interview format to ensure consistency between the content of each interview. Meanings were co-constructed in an ‘interactive negotiation’ (Lather, Reference Lather1991, p. 60) where both the researchers’ and interviewee's positions were adjusted throughout; the researchers used self-disclosure of their forming viewpoints on the subject matter to encourage this dynamic. Interviews were anonymised in accordance with the research ethics permission.Footnote 12 Analysis of the interview and site visit data for this paper focused on three principal areas: the extent of the use of video links to undertake judicial work, the way in which judges used video links and the effects of their use on the performance of the judicial role.

4 The expanding use of video links

It became evident through the course of the research that use of video links in Australian courts was far more extensive than had previously been documented and that judges were presiding via video link in a variety of different contexts and environments. Beyond its well-known use for taking evidence or allowing a defendant to appear from a prison or remand centre, interview data revealed that judges, supported by a range of legislation that presumes or permits its use (for a summary, see Rowden et al., Reference Rowden2013, pp. 95–96), are using video links for a wide variety of purposes and in many different situations. Video links are routinely used to conduct various types of pre-trial or other ‘administrative’ hearings. In criminal cases, this might include the use of video links (to prisons or other courtrooms) for the purposes of remand hearings, bail applications or hearings to discuss how a trial will be managed or run.Footnote 13 In civil cases, video links might be used to conduct various types of directions hearings with lawyers, advocates or partiesFootnote 14 and can involve linking to other courts, to law firms, barristers’ chambers or private locations. In hearings or trials, video links are being used to take evidence from witnesses generallyFootnote 15 and from expert witnessesFootnote 16 for various reasons including convenience and cost-saving. It has been particularly useful for facilitating the testimony of witnesses located interstate or overseas, and for taking evidence from children and other vulnerable witnesses.Footnote 17 Video links also may be used at the conclusion of a case to deliver a sentenceFootnote 18 or to hand down a judgment.Footnote 19 They are also being used to more efficiently manage court workloads by bringing a judge ‘remotely’ to another court location, such as to deal with urgent applications for restraining orders in domestic-violence cases,Footnote 20 to fill in for another judge who is on leave or unwell,Footnote 21 to enable judges to finish matters that they had begun while on circuitFootnote 22 and to receive a pre-sentence report or deliver a sentence.Footnote 23 In any of these situations, any number of trial participants, including the judge, could be attending remotely.Footnote 24 Many of the uses described above are discretionary and another analysis of these data has found that there are a range of factors that influence judicial decisions to allow or disallow the use of video links (Wallace, Reference Wallace2011). In this paper, however, we focus rather on the impact on the image and the role of the judge in those cases where video links are used.

5 The video-linked image of the judge

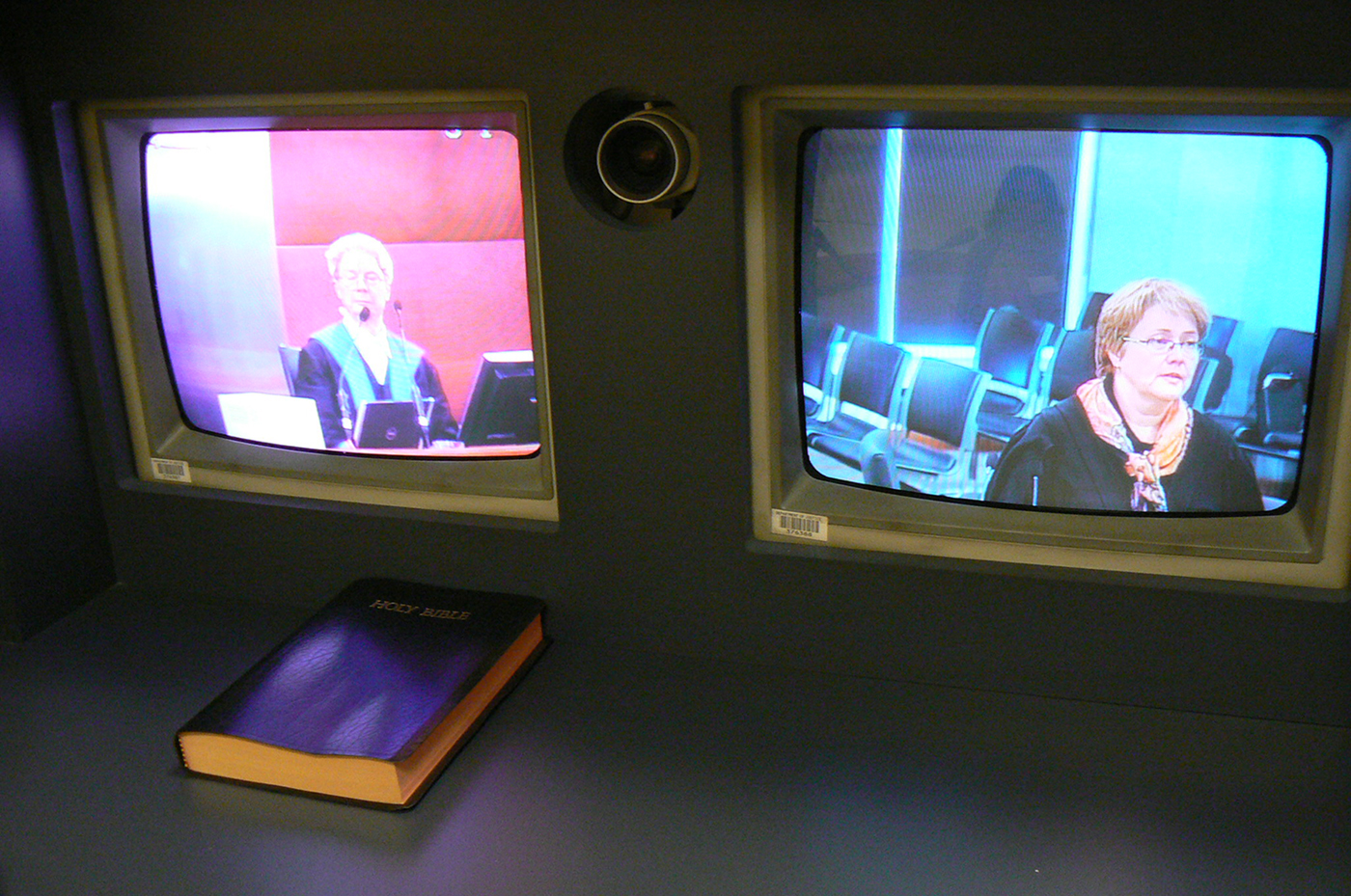

Our study revealed that judges appeared on screen during video-linked hearings in several different ways, each with implications not only for the way the judge might perform their role, but also for how they presented to other court participants. Perhaps most commonly, judges appeared from within a full courtroom, seated at the judicial bench upon the dais. The judge was then visible to the remote participant in one of three ways. In the first example, a head-and-shoulders shot of the judge would take up the full screen on one of two monitors (Figure 1) or appear as one half of a split screen with the other showing a view of the bar table.Footnote 25

Figure 1 The judge's image appears on a separate monitor to the lawyers at the bar table.

The level of zoom can vary greatly, with the judge sometimes appearing larger than life but in other instances much smaller. A second way in which the judge appears on screen is for the head-and-shoulders shot of the judge to take the form of a small picture-in-picture that accompanies a wide-angled view of the courtroom or a more narrow shot of the bar table (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Picture-in-picture close-up of head-and-shoulders shot of the judge within a shot of the bar table.

A third set-up that is used provides an overview of the whole courtroom, including the judge seated at the dais, with the option for a picture-in-picture image of the remote participant (which can be kept or turned off) (Figure 3). The availability of each of these set-ups would be dependent on a range of factors, including the age of the technology employed (the quality and technical range of the cameras and monitors), as well as the extent to which technicians at either end are trained or willing to adjust the settings on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 26

Figure 3 Overview of the courtroom with the image of the judge at the dais.

Judges presiding over a matter using video links may sit in a full courtroom and appear on screen to mostly one, but sometimes two or more, remote participants. The remote participant may be a vulnerable or expert witness, a defendant or a legal representative. There may be two or more remote participants in a link. As well as appearing on video link from a seated position behind the judicial bench in a courtroom, judges reported using video-conferencing facilities from their chambers to link to a variety of locations, including barristers’ chambers, prisons or other courtrooms. They also may preside over matters from empty courtrooms via video link to a courtroom at another location where all other participants are present.

In other publications arising from this research, we have reported that the use of video links is impacting on other aspects of the judicial role, including those that require the judge to make assessments about witness testimony and demeanour (Wallace, Reference Wallace2011; Rowden et al., Reference Rowden, Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty2010). For this paper, however, we have focused primarily on those examples in our data that shed light on the way that the image and role of the judge are being renegotiated in video-linked court proceedings. What our study makes evident is that the use of video links in court proceedings disrupts many of the ways in which judges usually appear to court participants and how they are imagined culturally. This effect on the image of the judge has important implications for two particular aspects of the judicial role: their management of the courtroom and their capacity to embody and project the authority of the court.

6 The judge: managing the court

One of the most fundamental judicial tasks is to control the conduct of court proceedings in order to achieve a fair trial. For example, judges must ensure that only admissible evidence is put before a jury, that witnesses understand the significance of giving evidence, are not coached or intimidated and the questions put to them are within the bounds of what is legally permissible. At a more general level, the judge must monitor proceedings to ensure that all participants in the courtroom, including the public gallery, conduct themselves with an appropriate level of respect for each other and for the court.

In reality, while ultimately judges are responsible for achieving a fair trial, they rely on other court personnel to assist them to fulfil this task. To achieve a smoothly run hearing, judges depend upon the information provided in a file prepared and kept by court staff and upon the activities of the tipstaff, court clerks and bench clerks who variously act as the ‘stage managers’ (Liberman, Reference Liberman2015) of the courtroom.

Our data suggest that the use of video links adds several additional elements to the judicial task of managing the courtroom, which require some adaptation by judges to the way they usually conduct proceedings. At its most basic, judges viewing a courtroom participant over video link now need to take additional steps to confirm that participant's identity.Footnote 27 Judges also now need to satisfy themselves that the communication link has been properly established, so that the witness can see and hear those in the courtroom and vice versa,Footnote 28 as well as ensure that, in the planning stages of a case, documents or exhibits that will need to be shown to a witness giving evidence by video link will be available at the remote end.Footnote 29

Remote participants, particularly those less familiar with court proceedings, also require more orientation to the courtroom when appearing by video link. The remote participant may need to be introduced to those with whom they will be speakingFootnote 30 and this may require additional preparation to tailor the introduction to their particular needsFootnote 31 or to the situation. For instance, in sexual-assault trials involving children, it might be necessary to reassure the remote child witness about who is present in the courtroom watching them give evidence.Footnote 32 It may also involve providing some orientation as to the court processFootnote 33 to a remote participant who is not familiar with it.Footnote 34

6.1 Asserting or sharing control?

Many judges spoke of needing to be, and being perceived to be, actively ‘taking control’ of proceedings where a participant was appearing via video link. This appeared to reflect an underlying concern that control was more difficult to assert in this situation.

One area of concern related to the administration and enforceability of the oath or affirmation required of a witness giving evidence by video link. There were concerns that the oath might not be taken as seriously if not administered face to faceFootnote 35 and may even not be enforceable.Footnote 36 For these reasons, one judge preferred to administer the oath to a remote witness themselves, rather than relying on court staff to do this, as is usual where a witness is physically located in the courtroom.Footnote 37 Other judges felt that the oath had more impact, and was more likely to be enforceable, when it was administered by a court officer present with the witness at the remote endFootnote 38 otherwise they too might opt to swear the remote witness in themselves over the link.Footnote 39

Judges were also concerned about being assured, and assuring others, of their ability to exert sufficient control over the remote court environment to ensure that a witness is not intimidated or otherwise influenced in a way that may affect the truth of their evidence. Our data revealed several interrelated challenges that the logistics of taking testimony by video link posed for judges in exercising this responsibility.

Many interviewees, especially judges, expressed concerns over the extent to which the current configuration of most video links enabled judges to discern whether or not a witness was being influenced by others present at the remote site, given that, unlike the situation in the courtroom, the judge may not have a clear view of the entire remote witness facility. One judge described the court's vulnerability:

‘Well that's the other thing, you don't know who else is in the room …. For example there might be an order for witnesses out of Court. You might have three lay witnesses giving remote evidence. Now how do you know that the other lay witnesses are not present … listening to the cross-examination? … you're relying on the other end complying … ensuring that people are out of ear shot of the other evidence being given, so that can be a problem as well.’Footnote 40

During the course of the research, we witnessed and heard of several different strategies that courts had employed to address this situation. For example, in the criminal courts in Dublin, Ireland, the remote court officer is required to swear an oath to the court that they are present in their capacity as an officer of the court and that they will not in any way coerce the witness.Footnote 41

The extent to which Australian judges perceived a risk of coercion or influence with video-linked evidence often depended on the ability to provide them with a more complete picture of the remote room and its occupants. The technology is usually configured to provide the judge with a separate camera view of the remote space (Figure 4). Judges usually accepted this overview, coupled with the view of the witness transmitted to the courtroom, as providing sufficient visual information to assess the risk of improper influence.

Figure 4 Example of an overview shot of a remote space, captured by a CCTV camera and visible on a separate display at the judge's bench.

However, if the video-link set-up did not provide good visibility of the whole room or when there were no court officers or support persons at the remote site, some judges reported enlisting the remote witness themselves to provide information about any potentially corrupting persons or material in the remote space.Footnote 42 One judge described the way they did this:

‘If they're not in that sort of Court environment, if they're in, like, a DPP [Director of Public Prosecutions] or a public office, I'll say “if there's any, anything interfering with your evidence, can you let me know that straight away?” you know, in case people walk in on their room by mistake or something like that.’Footnote 43

6.2 Directing or collaborating?

The task of monitoring of witnesses as they give their testimony also becomes more collaborative in video-linked encounters. A judge may need to intervene to disallow improper, bullying or harassing questions (see e.g. No. 42 of 2008, s. 41) or when a witness becomes too distressed to continue giving evidence. Making such an assessment can require the exercise of a fine judgment, for example, as to whether a witness appears distressed, is genuinely distressed or whether that distress is the result of having their credibility successfully challenged. It appears from our data that the limitations of communication over a video link can make it harder for the judge to perceive some aspects of the witness's body language that may inform those judgments. For example, a court clerk recalled:

‘I do recall one matter quite a few years ago that there was a child, she was giving evidence and she was being asked some questions that she got a bit fired up over …. And … the Magistrate had asked me to go into the remote [room]. She had somebody with her. But she looked – like to the Court – she looked … angry about it, but you went in there … she was just shaking.’Footnote 44

Another remote court officer felt they would often pick up distress signals from a remote witness earlier than a judge would.Footnote 45

Some remote court officers who sat with vulnerable child witnesses felt that the judiciary had now come to rely on them for monitoring the witness. As they expressed it:

‘I think when we started we were seen as possibly, you know, doing all sorts of evil things … influencing the court process, you know – in terms of coaching witnesses or, you know, interfering in proceedings and I think that [it has] come to be [seen] that we don't coach children and we don't interfere with the proceedings, that there's a level of comfort of it being out of court … there's a level of comfort that we're looking after the needs [of witnesses] and that they don't have to worry about that in their job.’Footnote 46

The judge, then, may rely on the remote court officer to gauge the emotional state of the witness and advise when the witness needs a break. In this way, the judge is sharing the task of monitoring the witness with the remote court officer – something that would not be necessary if the witness were giving evidence in the physical courtroom where the judge could observe their demeanour more clearly. The level of direct engagement between the witness and the judge is also diminished, as the encounter becomes more akin to a screen performance (by other parties) rather than a face-to-face encounter.

6.3 A shared enterprise?

Remote court officers are not the only participants who share responsibility for courtroom management with the judge in the video-linked courtroom. In interacting with remote participants over video links, the judge is dependent on the effective management of the video-link connection itself: the way links are established and configured and their technical quality monitored. This task is often carried out by the court clerk or bench clerk, adding an additional cognitive load to that person's task (Rowden et al., Reference Rowden, Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty2010, p. 375). Some judges evidenced an awareness of the need to maintain oversight of the process. One commented, when speaking of the way that video links should be set up and operated: ‘But you need your court officer to be at the gear stick, and you need your judicial officer to be saying “this is how I want it done”.’Footnote 47

In this way, both the judge and the court officer are sharing the responsibility for the configuration and operation of the video link, with the judge taking on something of a new role, akin to that of the ‘director’ of the video link.

6.4 Judge as independent, but dependent on others?

The data described above demonstrate several ways in which many aspects of the judge's role as the key manager of courtroom proceedings are impacted by the use of video links. Important functions that need to be carried out have become dependent on the operation and configuration of the technology or reliant on the judgment of others, so that responsibility is shared. These factors in some way blur and confront the cultural image of the independent judge wielding absolute control over their courtroom, although, in fact, it is possibly only drawing attention to the fact that controlling the courtroom, in many ways, has always been a collaborative effort. However, the exercise of judicial control in the distributed court environment is dependent on a greater range of factors, including the technology, the affordances of the courtroom, as well of those of the remote environments, and the talents and energy of the court personnel stationed in either place.

Our data also revealed that the way in which the image of the judge is portrayed to other court participants in the video-linked encounter can be at odds with the cultural image of the judge to the extent that it influences the capacity, or perceived capacity, of the judge to imbue the authority of the court. This is often made evident through the behaviour of other court participants. It is to these examples that we now turn.

7 The judge: imbuing authority

Managing court proceedings to ensure they are conducted fairly is one important way that judges promote community acceptance of the court as a legitimate source of authority. But it is not the only way in which authority is generated. As Dovey asserts, ‘authority becomes stabilized and legitimated through spatial rituals and the architectural framing of them’ (Reference Dovey2010, p. 125). The space of the trial has long been used to create an authorised space for law and the raised judicial dais has remained an important long-standing symbol within that tradition (Graham, Reference Graham2003). From early makeshift furnishings in the fifteenth-century courtroom to modernist and post-modern courthouse schemes that tend towards flattening the courtroom interior, the raised dais has prevailed (Mulcahy, Reference Mulcahy2011). Other architectural cues such as the judicial canopy, or the coat of arms, frame the judge in a regal majesty and hearken back to justice dispensed by the monarch under a tree, lending legitimacy and authority (Jacob, Reference Jacob1995).Footnote 48 If architecture sets the scene, court rituals punctuate the message and reinforce the point. The well-worn characterisation of the court as a theatre (Ball, Reference Ball1975–76), evidenced by the retention of arcane costume, use of heightened language and long-standing court rituals, such as standing when the judge enters, and bowing to the court on departure all contribute to the generation and maintenance of the court's authority. They also combine to cue particular expected civic modes of address as well as respectful and polite behaviour by courtroom participants. The fact that so many of the rituals and so many of the longest-standing spatial features of the court centre on the judge emphasises the central symbolic function of the judicial role as embodying the independent authority of the court.

Challenges to the authority of the court can take a variety of forms and be overt or subtle. Court participants might choose to ignore rules and protocols, and behave disruptively or impolitely towards authority figures such as the judge, court orderlies or other court staff. The judicial power to punish behaviour that transgresses these rules as contempt of court is one measure for maintaining and restoring authority. However, the power of the cultural image of the judge is evidenced by the fact that judicial presence alone may also serve to deter such challenges.

7.1 An alternative view

It appears from our data that the use of video links can make it more difficult for the judge to both embody and maintain the authority of the court. This arises, in part, from the impact of the video link on the image of the judge and also on the rituals that serve to reinforce that authority. We argue that the introduction of television screens in the courtroom and the way in which the video links alter the image of the judge challenge the judge's performance of authority in subtle but complex ways.

The work of Clover (Reference Clover1998) and Moran (Reference Moran2016) reminds us that framing and camera angles have important implications for how the camera presents the judge, as well as how it positions the viewer in relation to the judge. We found that the way that the framing and angles are used in court video links often creates views of courtroom participants, including the judge, that are different to those available in the courtroom. In many set-ups we visited, this results in a somewhat imperfect view of the judge for the remote participant that impacts adversely on the judge's ability to establish their authority, both literally and figuratively. For example, it was common for the camera that takes the judge's image to the remote room to be located above one of the monitors in the courtroom, often the monitor above the witness stand, thus positioning the camera above the eye line of the judge (see Figures 5 and 6). As a result, the image of the judge provided to the remote participant completely inverses a well-established spatial cue of many courtroom designs. Rather than the judge occupying the highest position in the room, the eyes of the remote participant effectively look down on the judge. In another example, one technology officer explained that, in that jurisdiction, when a judge is being linked to a regional court to preside, the judge generally appears as a small ‘picture-in-picture’ on the larger screen available in the courtroom.Footnote 49

Figure 5 Image of the judge produced by a camera sitting slightly above the judge.

Figure 6 Sketch of cameras in the courtroom picking up the image of the judge at the bench. If the courtroom has multiple screens, the judge needs to be aware of which screen to look at, otherwise the witness would see a side view of their face.

Interviewees felt that it was important that the image of the court and the judge that was shown to the remote participant on video link was as realistic as possible, to ensure an understanding by the remote participant of the seriousness of the matter. One judge commented:

‘obviously the more a video link can have the effect of a witness seeing that there is a Court in operation – a presiding Judge or Magistrate and barristers over at the bar table – I think it gives a much better feel for a Court … I think they're acquainted more with the seriousness of the evidence that they're giving … I think it's important to impress on the person the solemnity of the occasion and the importance of their evidence.’Footnote 50

Another judge was of the view that, in the absence of the environment of the courtroom, there was an onus on the judge to look for other means to reinforce their authority:

‘[W]e do run these on-site hearings, or we take some evidence on site … you may be on site but you still have to run it as a court hearing …. You should be able to be authoritative in that situation by your presence and your words regardless of … the court trappings … that situation is no different to when you've got the witness on the videoconference. You take control of it and say “this is what's going to happen” … we've just never had any issue with that. People are very obedient once you actually do that, show that you're in control.’Footnote 51

When the usual ‘court trappings’ are in short supply, something else needs to be invoked to ensure judicial authority, to signify judicial ‘presence’ and to ensure that the fact that the court is in session is clearly recognisable by those in attendance. This interviewee is suggesting that this can be achieved by an appropriate use of language and demeanour on the part of the judge and an attempt to actively take control in the new environment.

7.2 Conveying authority

In the absence of additional measures, the image of the judge and the courtroom on the video link alone may not always adequately convey the authority of the court and this can affect proceedings. As the authors have noted elsewhere, there was frequent mention in interviews of a tendency by some remote participants to exhibit less inhibited behaviour when participating in court proceedings via video link (Rowden et al., Reference Rowden, Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty2010). Possibly this is due to the relative informality of proceedings at the remote end of the video link that may diminish the availability of the behavioural cues of the courtroom (Rowden et al., Reference Rowden, Wallace and Goodman-Delahunty2010; Rowden, Reference Rowden2011). The impact of this disparity, however, seemed to differ for each kind of participant.

Overall, stakeholders did not feel that children and other vulnerable witnesses giving evidence by video link lacked an appreciation of the seriousness of the matter and the authority of the court. Interviewees reported that remote vulnerable and child witnesses were well aware of the fact that they were attending court via video link. As one remote court officer described, the formality of the proceedings, the language and the ritual of the judicial robes were all important in informing that understanding:

‘The whole – the question and answer routine is very formal. The Judges are wearing gowns and even if there are people in relatively ordinary clothes, the way they present, the language that they use is so alien to these kids in the first place that, they are immediately – it's like, you know, suddenly being in front of the principal at school … as they go into that [remote] room they will be serious.’Footnote 52

Another remote court officer reported: ‘all witnesses are very aware of what's going on. Most of them are frightened to death. And many of them are shaking … I think they all take it very seriously …. Even the children.’Footnote 53

Court support officers who sat with these participants argued overwhelmingly that, despite sitting in a non-descript room, away from the imposing architecture of the courthouse and the physical presence of the judge, children and vulnerable adults giving evidence remotely understood that they were attending a courtroom and that the matter was serious. However, those commenting on the behaviour of some defendants appearing via video link did not report the same opinions.

In sentencing a defendant, and in some cases denying their liberty, a judge acts on behalf of the state and the community in whose name they uphold certain values and shared beliefs about what is acceptable behaviour. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that, in the one act in which the judge brings to bear on an individual the full authority of the court and the full force of the state, the challenges that video link poses for the judge are at their most acute. As one judge described:

‘[A]lmost every time I've done – that is, it seems that the person, if they're on the other end of a video screen, are more likely to ark up and swear, shout, complain about how they're being dealt with … whereas they tend not to do that if they're in court and you've got them face to face. So it seems they feel like there is a greater liberty to go ballistic on the other end of a video camera than if they're in court.’Footnote 54

This judge also noted that, in such instances, the technology could be used to silence those participants who are perceived to be ‘misbehaving’ by switching off the microphone. Others confirmed that this was a common response by judges when faced with a fractious defendant appearing by video link.Footnote 55

However, the same judge noted that such an overt use of the technology in this way was not ideal in terms of ‘a process of justice’.Footnote 56 The discomfort they expressed about, in effect, silencing the defendant through the mute button has resonance with the example of the Bobby Seale trial in the US in the 1960s where the defendant was gagged and bound in the courtroom (Cover, Reference Cover1986, p. 1607, n. 17). Such a response of the courts to a violent outburst by a disgruntled remote defendant receiving a sentencing verdict may impact upon perceptions of due process and therefore has implications for the legitimacy and authority of the court.

It is important to note that not all judges interviewed reported experiencing difficulties maintaining the authority of the court when sentencing via video link. One reported that:

‘I think maybe because they see you, and they see you robed, and they see you're in an obvious courtroom setting … they tend to behave as if they were present in the courtroom. And I've never had any difficulty in dealing with people. I suppose if there was going to be a person who was going to be fractious, or you had any sort of advance warning, you might be careful. But no, generally speaking, no. No problem whatsoever.’Footnote 57

Unlike the judge quoted earlier, this judge is from a higher court and would have appeared robed from a more elaborately furnished courtroom. The former, a magistrate, would appear unrobed from a more prosaic courtroom location. This suggests that the ability for the encounter to provide behavioural cues from the way that the judge is framed, in terms of dress and background, may be an important factor in conveying and maintaining judicial authority when sentencing proceedings are conducted by video link. A sentencing judge who is framed as sitting in a more neutral space, on their own, is perhaps more likely to be perceived by the remote defendant as an individual rather than as an authority figure whose role is to deliver that verdict as the designated representative of the community.

7.3 Engaging the community

Several interviewees spoke of the symbolic importance of the court in expressing community-held values – values that were somehow expressed and locatable by the presence of the courtroom and courthouse and the performance of the judge. Other judges spoke of how the very presence of the courts affirmed the presence of a community, of a society, by reflecting its values back to itself.Footnote 58 The invocation of these values seemed most acute at the point of judgment, although there were some perceived differences in the relative importance of this between criminal and most civil cases.

Judges seemed to have fewer issues using video link to deliver judgments in civil cases, most likely because these cases are often simply resolving a dispute between two private parties. While one interviewee expressed the view that it was an odd feeling for a judgment to be delivered by video link, essentially to an empty courtroom,Footnote 59 interviewees were less concerned about the possible diminution of the authority of the court when a decision in a civil case was delivered by video link. As one interviewee expressed, it is the decision itself, rather than the image of the person delivering it, that is more important:

‘I don't have any great difficulty with all that [delivering a judgment via video link], it's really not so much important as to what I look like or the view that people have of me, it's really the words coming through so I don't think it's as quite as important.’Footnote 60

However, it may be different in particularly fraught civil cases that affect a group of the public, such as the findings of coronial inquiries involving mass disasters or in class actions. One judge emphasised the importance of providing an opportunity for an affected community to come together to experience the emotions connected with the delivery of a judgment in such circumstances:

‘they are really hugely charged environments … but people can cope and … I think it is valuable also to a large degree for them to experience the suffering and anguish together … to understand that it's not a mechanical process, it's not some arbitrary cold-blooded process.’

The use of the terms ‘arbitrary’ and ‘cold-blooded’ suggest that, for this stakeholder, removing the participant from the communal space of the courtroom speaks not only to feelings of disconnection, but also to damaging perceptions of legitimacy.

However, a sentencing decision is delivered not only to the defendant, but also to the community that the judge serves. Those proceedings are traditionally conducted in public and may include the victim, or victims, and family and supporters of both the victim and the defendant, as well as representatives of the media. Reservations about sentencing hearings being conducted by video link were not confined to concerns about the impact on the defendant, but also, as one interviewee described, ‘about the symbolism of sentencing and what it meant for the community’.Footnote 61

As noted above, while we observed considerable variation between courts in the way the video links were set up and operated, generally speaking, it appears that the image of a judge delivering a sentence on video link is conveyed to the remote end as a head-and-shoulders shot seated behind the judicial dais, in a full-screen view.Footnote 62 While some Australian courts do film footage of the judge delivering significant sentencing decisions for dissemination on the court's website, this appears to be done outside of the court video-conferencing system and, in most cases, the media are only provided with a transcript or audio file of the sentencing remarks.Footnote 63

That the image of the judge as someone engaged with the community should speak to their set of values was seen as important for the legitimacy of the sentencing process. One judge commented that they would directly involve community members during sentencing, particularly when sentencing children:

‘I don't use the video link … where I want [not just] the child, the family but the community to all have an impression [of] the law, I go there …. The video link facilities don't really cater for … that sense of community. Whereas if you're there and you're in the courtroom, the courtroom can be packed with community. So where I think there's a case that goes to the child, to the family, to the community, [and] you're wanting to make a point, a very serious point, I don't use video links. I go there so you can basically interact with as many people in the community as possible all at the one time, which is not possible on the video link.’Footnote 64

Similarly, another interviewee referred to the difference between setting limits through sentencing in the context of a community of people gathered in one location vs. the attempt to set those limits when the transgressing person is isolated:

‘it's … about saying to people there are limits, there are community limits there are things that – there are bounds beyond which you really should not go. And you can say that to a person in a small room who's looking into a video screen and have potentially some impact I suppose. But if you've got somebody sitting in the Court surrounded by other people where you're saying that, then it does appear to be more of a reflection of what people in a community think about something.’Footnote 65

To ensure transparency and accountability, open public hearings are necessary for proper engagement between judges and the communities that they serve. The law needs to be able to be located not just by the figure and presence of the judge appearing on screen, but also by the ability to locate the place to see justice being dispensed. Unsurprisingly, then, the prospect of several parties appearing remotely at once caused concerns for some interviewees, as one queried:

‘so, you know, it's not just audio visual links with witnesses and defendants but potentially counsel and judges … especially there you ask – where's the court? You need to, sort of, in a sense, define where the court is or at least actually have a system that identifies where people can go to see if proceedings are public.’Footnote 66

For this interviewee, this place needed to be in a defined location so that a community could know where to go in order to view proceedings – a feature deemed critical to the principle of ‘open justice’. The image of the judge is an important part of those proceedings and should, therefore, be visible, legible and accessible. However, our findings suggest that increasing use of video-conferencing technologies requires more overt attention to the ways in which the image of the judge is crafted.

This new advertence to the ways in which the judge's image is being constructed through camera and screen requires the attention more commonly associated with film production (Mulcahy, Reference Mulcahy2008). Courts should pay attention, as film directors do, to the background to the subject, the costume of the subject, the presence or absence of symbolic markers of justice (such as the coat of arms), as well as the impact of camera angles, close-ups or long-shots, views from above, below or from the side (Moran, Reference Moran2016; Clover, Reference Clover1998). Courts could develop more sophisticated protocols, as they have done in the UK in regard to filming judgment summaries (Moran, Reference Moran2016), that set minimum standards for a video-linked image of a judge.Footnote 67

8 Judge as collaborator

In the studies referred to earlier, technology is presented as a new insertion into an assemblage of parts – a network of human and non-human elements (Latour, Reference Latour2005) of ‘social, material, linguistic and non-linguistic agencies’ (Licoppe and Dumoulin, Reference Licoppe and Dumoulin2010, p. 229) that shape both activities and meaning-making. These studies also point to the ways in which the construction of justice, authority and legitimacy in the courtroom is not fixed, but contingent, performative and in the making (Rowden, Reference Rowden2011). Our study lends further weight to their findings and demonstrates how cultural ideations of the judge and how they perform their role are being challenged in the new ‘networked’ paradigm of the distributed courtroom. Lanzara and Patriotta (Reference Lanzara and Patriotta2001) found that judges needed to actively engage with designing new practices to adjust to the changes brought by the introduction of a new technology into their workplace. Similarly, the examples we cite from our study highlight the additional workload that successful video links entail for judges, which may require them to give more conscious attention to particular tasks.

These examples from our data are also often noteworthy for the degree of anxiety expressed by judges and others over a perceived loss of judicial control of the entire courtroom environment and the effect of video links on the capacity of the judge to embody and project the authority of the court. The latter reflects a particular level of concern as to how the authority of the court can be impressed upon a remote participant appearing via video link. Of course, the ability to control proceedings and the capacity to project authority are somewhat interrelated.

In the physical courtroom, the environment provides behavioural cues through spatial syntax and symbolic imagery that help to impress upon all courtroom participants the serious nature of the matter, their tasks and their importance for the proceeding. What appears from our data is that, in its absence, this task then needs to be reassigned to other parts of the heterogeneous network (Latour, Reference Latour2005) of materials, rituals and personnel involved in a court proceeding (Rowden, Reference Rowden2011; Reference Rowden, Simon, Temple and Tobe2013). Our data demonstrate that, in many instances, this is already occurring, such as in the case of the personal administration of the oath by the judge themselves or by the person who is present with the witness in the remote space, as well as incorporation of virtual orientations to the courtroom conducted over the video link. It is evident that judges are often not aware of the ways in which they are adapting their performance to the new medium. However, there were several instances revealed in our study that suggest judges could make more explicit efforts to compensate for the absence of the usual affordances and cues provided by the physical courtroom in order to assist the remote participant to effectively ‘enter’ and remain in the court space. Our findings also suggest that the construction and maintenance of the cultural image of the judge – as the embodiment of authority – require careful calibration in concert with the efforts of court staff and lawyers in the video-linked court environment.

In terms of courtroom management, the judge's access to the remote space is dependent on the court staff who initiate and configure the video link. Some judges appear to be reassured in their control of the remote space by utilising the shot of the overview camera, where available, to get a better picture of the extent of the room and any potential influences it could contain. Some are forced instead to rely on the help of others in the remote space to verify that the testimony is not being tampered with or affected or, in their absence, to engage directly with the witness about that issue and rely upon their honesty. Similarly, where vulnerable witnesses give evidence remotely, judges appear, to some extent, to be ‘outsourcing’ to the remote court support officer the responsibility for monitoring the witness's performance and emotional state.

In many ways, these acts of knowledge-sharing and reliance become open acknowledgements of the networked nature of ‘judicial control’ being performed in courts, whether video-linked or not. Here again, our findings conform to Licoppe and Dumoulin, as they explain that the judge in their study was more reliant on the strategic work of others in the courtroom to reinterpret events and restore judicial authority in the event of a failed judicial speech act (summoning a witness and nobody arriving) during a video-linked encounter (Reference Licoppe and Dumoulin2010, pp. 185–186). Furthermore, a more overt acknowledgement of the way courtroom management is networked in the distributed court challenges our cultural conception of the judge as being the one person solely in charge of the courtroom. In the distributed court, control is more obviously exercised through others who variously manage and configure the technology, verify the oath and support and monitor the witness.

Similarly, the projection of judicial authority becomes a collaborative construction, dependent on the technology and tasks that are shared with others. Our findings suggest that, in the video-linked courtroom, the framing of the judge, the choice of camera shot and the way that the judge is presented assume considerable importance in reinforcing judicial authority. Witnesses and defendants may be most likely to perceive and respect that authority when the image they receive places the judge in a context that is formal and authoritative and provides appropriate cues, such as by way of language, dress and backdrop, to prompt them to respond appropriately.

9 Conclusions

Our findings suggest that achieving distributed court encounters that deliver an image of the judge that is congruent with the judicial role in the adversarial court system may require a refinement in design, where greater attention is paid to the configuration of the technology and the overall spatial design. It may also require increased attention to the skills of those managing the technology, who are, in a sense, directing the production of on-screen judicial images. They also suggest the need for the judge to take more active steps to exert control and authority in a video-linked court proceeding and to pay closer attention to elements of their performance and how it may impact upon perceptions of their authority and their role. It is also clear that judges need to call upon others, in both the courtroom and the remote space, who have the skills and the capacity to support them in crafting that image. Other factors that may be important to consider will include the degree of familiarity that various court participants may have of video-mediated communication and the court process generally. For example, a novice participant may require a greater degree of orientation and support than a ‘repeat player’.

It has been observed elsewhere that it is somewhat paradoxical that the increased use of video links, associated as they are with more distant or impersonal communication, has occurred at time when there has also been a strong move towards more engaged styles of judging (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Roach and Mack2017). The trend towards therapeutic styles of judging has also resulted in a change in the nature of judicial work, to the extent that judges working in problem-solving courts typically view themselves as working as part of a team, which draws on the skills of other professionals, each managing the specific aspects of an individual's programme (King et al., Reference King2014). This suggests that the image of the judge may be one that is continuing to evolve and the challenge for courts in the future will be to ensure that, in whatever form it is conveyed, the image is congruent with the nature of the role and its responsibilities. In its most positive light, the use of video links might prompt new discussions about what the image of the judge should be.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the reviewers who provided very helpful feedback on this paper. It reports on data collected for the Gateways to Justice Project funded by the Australian Research Council Linkage Grant (Project number: LP0776248) and led by Professor David Tait (Western Sydney University). All images © Emma Rowden. Participants in all photographs within this article are members of the research team.