The fundaments of liberal democracy include both freedom of speech and the protection of minorities. Although these principles are often interrelated, they can collide when politicians make controversial public statements about minorities (Bleich Reference Bleich2011; Brems Reference Brems2002). Such statements may fall under the rubric of hate speech, which is legally prohibited in most established democracies. The prosecution of politicians for hate speech has become a widespread phenomenon in recent decades (Fennema Reference Fennema, Koopmans and Statham2000; Jacobs and Van Spanje Reference Jacobs and Van Spanje2018).

Although such legal action is intended to protect democratic values, it seems conceivable that this is not how everyone perceives it. Some may instead view hate speech trials as politically motivated assaults on democratic rights to free speech and representation. Such discontented citizens may for example include those who support the prosecuted politician or sympathize with his or her statements. Consequently, hate speech prosecution might alienate part of the population from liberal democracy in general and the legal system in particular. This study examined this possibility by looking at the case of Geert Wilders. As the leader of the Dutch anti-immigration party ‘PVV’, Wilders has been prosecuted for statements about Islam and Moroccans since 2009 and was convicted in 2016.

This study specifically examined political support, which refers to citizens' evaluations of their political system and its institutions (Easton Reference Easton1975). A low level of political support is believed to be problematic for democracy because it reduces democratic participation. For example, people who negatively evaluate political institutions are less likely to vote or engage in other participatory activities (Aberbach and Walker Reference Aberbach, Walker and Crecine1970; Hooghe and Marien Reference Hooghe and Marien2013). Instead, those who feel themselves excluded politically are more likely to engage in noninstitutional politics, violent protest, or even attacks (Hooghe and Marien Reference Hooghe and Marien2013; Katsanidoua and Eder Reference Katsanidou and Eder2018; Muller, Jukam and Seligson Reference Muller, Jukam and Seligson1982). A lack of political support consequently has the potential to undermine the legitimacy and stability of democratic governance (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1978). If hate speech prosecution indeed diminishes citizens' political support, it could therefore damage the democratic system, even though one of the purposes of hate speech prosecution is precisely to defend liberal democratic values. In this regard, hate speech prosecution is often viewed in the context of ‘militant democracy’, which is the idea that liberal democracies need (legal) instruments to defend themselves against anti-liberal and anti-democratic threats (Capoccia Reference Capoccia2005; Capoccia Reference Capoccia2013; Loewenstein Reference Loewenstein1937). Moreover, the prosecution of hate speech against ethnic minorities may invoke discontent particularly among those who oppose the multicultural society, which is a group that is already characterized by an alarmingly low level of political support. Indeed, negative attitudes about multiculturalism are arguably the strongest correlate of political discontent in many Western democracies (for example, Citrin, Levy and Wright Reference Citrin, Levy and Wright2014; Elchardus and Smits Reference Elchardus and Smits2002).

Despite this potential importance, the extensive literature on hate speech (for example, Brown Reference Brown2015; Waldron Reference Waldron2012) and legal prosecution against politicians and parties (for example, Askola Reference Askola2015; Capoccia Reference Capoccia2005; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2006) has never rigorously assessed how it may affect political support. Vice versa, research on the impact of court decisions on political support (for example, in the case of the US Supreme Court; Grosskopf and Mondak Reference Grosskopf and Mondak1998; Kritzer Reference Kritzer2001) has never examined the prosecution of politicians for hate speech. The only exception is a study by Van Spanje and De Vreese (Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2014), which revealed that opponents of the multicultural society indeed lowered their satisfaction with democracy after a Dutch court decided to prosecute Wilders in 2009. In the absence of an experimental design, it however remains uncertain if this decline was indeed caused by Wilders' prosecution. Furthermore, this study was limited to satisfaction with democracy as outcome variable.

The present study therefore aimed to confirm this earlier finding and expand upon it by examining evaluations of both the legal system and democracy using three different research designs. First, a survey experiment randomly exposed participants to news about an upcoming conviction of Wilders and then compared their evaluations of the legal system and democracy to a control condition. Secondly, a quasi-experiment compared respondents who completed a survey immediately after Wilders' conviction with others who participated just before this event, taking scores on a pre-test into account. Thirdly, a nine-year panel study examined if the events in Wilders' prosecution coincided with shifts in political support during the entire period in which these events took place. This combination of methods allowed us to simultaneously unravel the causal mechanisms under controlled circumstances (that is, internal validity), while also verifying how these mechanisms translate to a real-world context and time span (that is, external validity). This study furthermore examined if hate speech prosecution erodes political support only among the accused's electorate (that is, Wilders' voters), or more broadly among everyone who supports the idea behind his or her statements (that is, opponents of the multicultural society). Finally, this study investigated if citizens who reject the accused's statements (that is, proponents of the multicultural society) reversely raise their political support in response to the legal action. This resulted in a comprehensive analysis of the effects of legal prosecution of a politician on support for the legal system and democracy.

Theory and hypotheses

Could Hate Speech Prosecution Undermine Political Support?

The European Court of Human Rights (2017) defines hate speech as ‘all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify hatred based on intolerance and indignity of all human beings.’ An impulse to the prosecution of hate speech was given in 1965, when the United Nations adopted the ‘International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination’ (ICERD). In August 2020, this convention had been ratified by 182 countries (UN OLA 2020). As mandated by this convention, most European democracies have implemented legislation that prohibits hate speech (cf. Fennema Reference Fennema, Koopmans and Statham2000). A considerable number of politicians has since been prosecuted based on these laws, including Jesper Langballe in Denmark, Flavio Tosi in Italy, and Jussi Halla-aho in Finland (for example, Askola Reference Askola2015). In the Netherlands and Belgium alone, more than 50 politicians have been prosecuted in recent decades (Van Donselaar Reference Van Donselaar1995; Vrielink Reference Vrielink2010). Specifically, the ICERD was ratified by the Netherlands in 1971. Wilders was prosecuted based on legislation that dates back to 1934 and that was adjusted following that ratification (Snijders and Shoemaker Wood Reference Snijders, Shoemaker Wood and Gitlin2018).

The concept of political support refers to citizens' evaluations of their political system and its institutions (Easton Reference Easton1975). David Easton (Reference Easton1965) distinguished three objects of support: the community, the regime, and the authorities. Easton (Reference Easton1975) furthermore conceptualized that support can range from specific (that is, support for an institution) to diffuse (that is, attachment to the system). Pippa Norris (Reference Norris1999, Norris Reference Norris2011) further specified this framework by proposing five dimensions of political support that range from diffuse to specific: (1) belonging to the nation-state, (2) agreement with core principles and normative values upon which the regime is based, (3) evaluations of the regime's overall performance, (4) confidence in regime institutions and (5) approval of incumbent office holders. Norris (Reference Norris2006, 6) furthermore proposed that measures of citizens' satisfaction can be used as indicators of ‘public evaluations of how well autocratic or democratic governments work in practice’. The current study therefore examined evaluations of the legal system and democracy as indicated by citizens' confidence and satisfaction. Evaluations of democracy fall under Norris' third dimension (that is, evaluations of the overall performance of the regime), whereas evaluations of the legal system are part of the fourth dimension (that is, confidence in regime institutions).

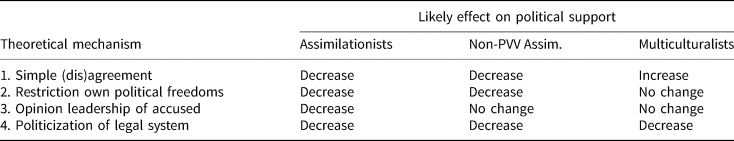

There are at least four reasons to expect that the prosecution of politicians for hate speech could diminish political support. Although it should be emphasized that it was not an aim of this study to determine which of these explanatory mechanisms best explains the impact of hate speech prosecution, we distinguish these four processes to theorize what groups of citizens may be affected. The first mechanism can be derived from the simple idea that citizens evaluate institutions and democracy more favorably when things go their way. Easton (Reference Easton1965) used the term ‘output failure’ to refer to instances in which political support is diminished because authorities are unable or unwilling to meet citizens' demands. Any important decision by a political institution therefore has the potential to strengthen support among those who get what they want and to weaken it among those who disagree with the outcome (Arnesen Reference Arnesen2017; Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013). A similar phenomenon can be observed after elections, when voters of winning parties generally report a greater satisfaction with democracy than supporters of the losers (for example, Dahlberg and Linde Reference Dahlberg and Linde2017). Likewise, American citizens typically lower their evaluations of the US Supreme Court when they disagree with a decision (Grosskopf and Mondak Reference Grosskopf and Mondak1998; Kritzer Reference Kritzer2001). In the case of hate speech prosecution, those who sympathize with the accused's ideas may therefore lower their evaluations of the legal system and democracy simply because they disagree with the undertaking.

Whereas the former reasoning would apply equally to any other controversial decision by an institution, the second reason why hate speech prosecution may undermine political support is both more specific and more fundamental. The decision to prosecute a politician for hate speech is not merely a decision that people can disagree with, but also something that affects the core of their democratic rights. People who agree with the idea behind the accused's statements may regard that they are no longer free to express their views or to elect someone who represents their convictions. Wilders has for example consistently framed his prosecution as a political trial against the democratic rights of his voters (Van Noorloos Reference Van Noorloos2014). Directly after his conviction on 9 December 2016, he released a video in which he put it as follows: ‘I have a message for the judges who convicted me. You have restricted the freedom of speech of millions of Dutch citizens and thereby in fact convicted everyone. Nobody trusts you anymore’ (Video Wilders 2016).

This quote by Wilders also illustrates the third reason why hate speech prosecution could damage political support, namely that politicians provide important cues to their supporters about what political views to adopt (for example, Bakker, Lelkes and Malka Reference Bakker, Lelkes and Malka2019; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001). Most people may not have direct experience with the legal system and hence rely on messages from opinion leaders to determine their trust in the institution (Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992). When the prosecuted politician repeatedly states that the legal system is corrupted, this could therefore persuade many sympathizers to also distrust it. Accordingly, research shows that anti-establishment parties can fuel political distrust (Rooduijn, Van der Brug and De Lange Reference Rooduijn, Van der Brug and De Lange2016; Van der Brug Reference Van der Brug2003). This may apply in particular to citizens who psychologically identify with the accused's party, since the extensive literature on party identification demonstrates that this group is most likely to echo a party's message (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell1960; Carsey and Layman Reference Carsey and Layman2006).

The fourth reason why hate speech prosecution could erode political support is that it may politicize the legal system. Institutions usually enjoy more support when they are seen as independent authorities and less when they are perceived as ‘political’ (for example, Elchardus and Smits Reference Elchardus and Smits2002). It is likely for this reason that the legal system is generally among the most trusted institutions whereas for example political parties are often distrusted (for example, Dekker and Den Ridder Reference Dekker, Den Ridder, Van der Meer, Van der Kolk and Rekker2018). Gibson, Caldeira and Spence (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; Gibson Reference Gibson2007) for example argued that the legitimacy of the US Supreme Court has largely been unaffected by partisan and ideological polarization because citizens distinguish courts from other political institutions due to legitimizing judicial symbols. As Gibson (Reference Gibson2007, 516) put it: ‘The message of these powerful symbols is that courts are different, and owing to these differences, courts are worthy of more respect, deference, and obedience – in short, legitimacy.’ The prosecution of politicians may however detract from the legal system's apolitical reputation by drawing it closer to the political arena in the eyes of the public. In other words, citizens may intuitively approach an institution with a more critical attitude when it is subject to conflict over divisive societal issues.

Only four empirical studies have so far investigated the impact of the prosecution of politicians for hate speech on public opinion and only one of these focused on political support. This three-wave panel study by Van Spanje and De Vreese (Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2014) followed Dutch citizens in the weeks before and after the 2009 court decision to prosecute Wilders for hate speech. It revealed that citizens who reject the multicultural society lowered their evaluation of democracy during this period. This decline was stronger among those who were aware of the court's decision compared to others who were unaware, which tentatively suggests a causal effect of the ruling. In the absence of an experimental design, this causal inference however remains uncertain and this study only examined satisfaction with democracy as outcome variable. Indirectly related to the issue of political support, a second study used a similar design to demonstrate that Wilders' electoral support surged substantially in the polls after the court's decision to prosecute him (Van Spanje and De Vreese Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2015), while a third study examined the explanatory mechanisms of this effect (Jacobs and Van Spanje Reference Jacobs and Van Spanje2019) and a fourth study investigated the role of news media in this electoral impact (Jacobs and Van Spanje Reference Jacobs and Van Spanje2020). Based on our theoretical reasoning and these few earlier findings, we postulated our first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Hate speech prosecution of politicians decreases evaluations of the legal system and democracy among citizens who support the idea behind the accused's statements.

For Whom Would Hate Speech Prosecution Undermine Political Support?

If hate speech prosecution indeed damages political support, this raises the question for whom this is the case. The four aforementioned explanatory mechanisms lead us to different expectations about how many citizens may be affected. Based on the first (simple disagreement) and second reasoning (restriction own political freedoms), we may expect that hate speech prosecution reduces political support among everyone who supports the idea behind the accused's statements. In the case of Wilders, this would imply that political support diminishes among everyone who opposes the multicultural society, whom we refer to as assimilationists. Regardless of whether or not they voted for Wilders, assimilationists may perceive that their freedom of speech is being restricted. Even assimilationists who disapprove of Wilders' choice of words may therefore oppose his prosecution.

Based on the fourth account (politicization of the legal system) the affected group could be even broader. The legal system could lose some of its status as an apolitical authority for every citizen due to the prosecution of a politician, even for those who reject the accused's views and applaud the prosecution. Following the third account (opinion leadership), the affected group could however also be narrower. Only citizens who support the accused's party are likely to take cues from it about what institutions to trust. Those who merely agree with the accused's statements, but vote for a different party, will probably not follow him or her as an opinion leader. Particularly in a multiparty context, the group that actually votes for a party can be considerably smaller than the group that agrees with it on a particular issue. For example, about one-third of Dutch citizens reject immigration (for example, Van der Brug and Van Spanje Reference Van der Brug and Van Spanje2009), but only 10–15 per cent votes for the PVV.

The only earlier study on hate speech prosecution and political support examined attitudes about the multicultural society, but not vote choice, as a moderator (Van Spanje and De Vreese Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2014). Although this study revealed a decline in political support among assimilationists after a court decision to prosecute Wilders, it consequently remains uncertain if this effect could have been driven entirely by PVV voters. The current study aimed to provide clarity on this issue by examining if hate speech prosecution diminishes political support only among the accused's electorate, or more generally among everyone who supports his or her views. Based on this earlier finding, our tentative expectation was that the latter would be most likely. We therefore formulated our second hypothesis as a stricter version of our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Hate speech prosecution of politicians decreases evaluations of the legal system and democracy among citizens who support the idea behind the accused's statements, regardless of whether they voted for his or her party.

Could Hate Speech Prosecution Strengthen Political Support?

Although hate speech prosecution may damage political support for some, it could potentially raise it among others. An obvious candidate to endorse the prosecution is the community that the alleged hate speech was aimed against. In the case of Wilders' second trial, people in the Netherlands of Moroccan descent may for example perceive that the legal system is effectively protecting their rights as an ethnic minority. A much larger group that may applaud the prosecution however consists of everyone who rejects the accused's views. Proponents of multiculturalism, whom we refer to as multiculturalists, will likely welcome Wilders' prosecution as an instrument to defend multicultural values such as tolerance of diversity. As such, their evaluations of the legal system and democracy may be strengthened by the endeavor. Theoretically, this can be viewed as an effect of citizens simply agreeing with the court's decision. Indeed, research on the US Supreme Court reveals that Americans commonly improve their evaluations of this institution when they agree with a decision, even though this favorable response is not as strong as the loss of support among citizens who disagree (Grosskops and Mondak Reference Grosskopf and Mondak1998). Table 1 provides an overview of how different groups of citizens may respond based on each of the four hypothesized mechanisms.

Table 1. Overview of explanatory mechanisms and their possible implications for political support

The only previous study on this topic (Van Spanje and De Vreese Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2014) failed to provide a conclusive answer to the question of whether those who oppose the accused's views increase their political support in response to hate speech prosecution. It showed that multiculturalists' satisfaction with democracy decreased, rather than increased, in the weeks after the court's decision to prosecute Wilders. This decline was however weaker among multiculturalists who were aware of the court's decision compared to multiculturalists who were unaware, which suggests that the court's decision may nonetheless have had a positive impact among this group. The current study therefore aimed to provide a clearer picture of multiculturalists' response to hate speech prosecution by examining the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Hate speech prosecution of politicians increases evaluations of the legal system and democracy among citizens who oppose the idea behind the accused's statements.

Finally, some citizens may reject or endorse hate speech prosecution based on universal principles. For example, some multiculturalists may nonetheless reject Wilders' prosecution out of a fundamental belief that free speech should never be restricted. Conversely, some assimilationists may support his prosecution because they believe minorities ought to be protected. Because such universal principles can work in both directions, they are not a reason to expect a structural increase or decrease in support for a particular group of citizens.

The Case Under Investigation

The present study examined the case of Geert Wilders (see, for example, Van Noorloos Reference Van Noorloos2014), who is the founder of the anti-immigration Freedom Party (PVV). The PVV was the first Dutch anti-immigration party to enjoy durable electoral success with 5.9 per cent of the votes in 2006, 15.5 per cent in 2010, 10.1 per cent in 2012, and 13.1 per cent in 2017. Alongside his more general critique of multiculturalism and European integration, Wilders is best known for his rejection of Islam. In 2007, he referred to Islam as ‘a fascist ideology’ and proposed to ban the Quran. Several people pressed charges and, although the public prosecutor initially decided not to instigate legal proceedings, an Amsterdam court ordered in 2009 that Wilders was to be prosecuted for these statements. The proceedings commenced in 2010 and resulted in a full acquittal in 2011. A second prosecution started after a political rally for the 2014 municipal elections, where Wilders asked his supporters if they wanted ‘more or fewer Moroccans’. The mob answered by chanting ‘fewer’, after which Wilders responded, ‘We will arrange it.’ The public prosecutor decided to prosecute Wilders for these statements in December of 2014 and the proceedings started in March of 2016. On 9 December 2016, the court ruled that Wilders was guilty of hate speech. A sentence was however not imposed.

Although this examination was a case study of one politician, the same mechanisms and effects may characterize other prosecutions for hate speech. The extent to which our findings generalize to other cases depends on the relevant characteristics of both the Dutch context and the specific case of Wilders. With regard to context, the immigration debate in the Netherlands is very typical of the divide over this issue that exists throughout Western Europe. For example, the Netherlands is about average compared to other West European countries in terms of the size of its immigrant population (Eurostat, 2019), the vote share of anti-immigration parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2013), and public support for multiculturalism (Bohman and Hjerm Reference Bohman and Hjerm2016). Moreover, the number of previous hate speech prosecutions in the Netherlands is not exceptionally small or large compared to other countries (Fennema Reference Fennema, Koopmans and Statham2000; Jacobs and Van Spanje Reference Jacobs and Van Spanje2018). Consequently, we see no obvious reasons why the prosecution of politicians for hate speech would have a different impact on political support in the Netherlands than in most other West European countries.

With regard to the specific case, three core characteristics may delimit generalizability. First, Wilders was prosecuted for statements that related to immigration and the multicultural society. The reasoning and analyses in this study therefore focussed specifically on citizens' attitudes about multiculturalism. Other attitudes may matter when politicians are prosecuted for other hate speech. For example, attitudes towards homosexuality may have played a similar role regarding the trial of Dutch MP Leen van Dijke for defamation of homosexuals in 1998–1999. A second core characteristic of the Wilders case is that he was the leader of a major political party. As a result, his prosecution was covered extensively by Dutch media and Wilders may have had a substantial ability to influence public opinion. The dynamics might have been very different for a leader of a minor party, such as Hans Janmaat in the Netherlands, Udo Voigt in Germany and Daniel Féret in Belgium. A third relevant characteristic of the Wilders case is that his statements seem sufficiently ambiguous to allow for different interpretations. The incident in which Wilders asked his supporters if they wanted ‘more or fewer Moroccans’ may have been perceived as extremely offensive and dangerous by his opponents, whereas Wilders' supporters may have viewed it as ‘simply a question’ about immigration policy. Combined with the fact that public opinion is highly divided on the underlying immigration issue, this ambiguity of Wilders' statements may therefore have contributed to a more polarized public opinion about his prosecution and a stronger potential to damage political support. Some caution is therefore warranted in generalizing our findings to cases in which the prosecuted statements were more universally rejected. An example is the prosecution of Jean-Marie Le Pen, whose antisemitic references to the Holocaust were widely condemned across the French political spectrum, as indicated by Le Pen's suspension from his own party. Other examples include the cases of Nick Griffin in Britain and Günter Deckert in Germany, who were also prosecuted for Holocaust revisionism.

In sum, we see little reason why hate speech prosecution would affect political support differently in most other West European countries or in other cases that resemble the Wilders case on relevant characteristics. Our findings may generalize in particular to other cases in which the accused's statements relate to immigration, the defendant is the leader of a major political party, and the prosecuted statements are ambiguous enough to divide public opinion on their acceptability. An example that resembles the Wilders case on all three characteristics is the prosecution of Marine Le Pen. As the leader of Front National, Le Pen was prosecuted in 2015 for a comparison that she made in 2010 between Muslim prayer and Nazi occupation. Indeed, the Wilders case seems to be indicative of a growing phenomenon that the leaders of anti-immigration parties explore the boundaries of what is legally permissible by making ambiguous statements about immigrants that their sympathizers would generally still find acceptable.

Study 1: survey experiment

Method

Sample

The first of our three studies was a survey experiment integrated into an online questionnaire. The 1,070 participants were drawn from an existing panel of Dutch citizens aged 18 and over. This panel achieved national representativeness by combining random selection (48 per cent of respondents) with more targeted methods (for example, snowball sampling) to recruit sufficient respondents from demographic groups with lower response rates. The experiment was conducted in the two weeks leading up to the court verdict on 9 December 2016.

Procedure

As part of the online survey, participants first answered questions about all moderating variables including their vote choice and attitudes about the multicultural society. They were then asked to read two news articles. The first article, about a discovery in a museum, was the same for all participants. The second article was about the upcoming verdict in Wilders' trial. If and how this article was presented was manipulated across eight experimental conditions to which respondents were randomly assigned.

The first was a not guilty condition (N = 140), in which respondents read that a verdict in Wilders' hate speech trial was upcoming and that he was to be acquitted according to both legal experts and sources close to the court. A guilty condition (N = 683) was contrarily confronted with a message that Wilders was about to be convicted for hate speech according to these same sources. The sentence that Wilders would receive was randomly manipulated across respondents in this condition: conviction without a sentence, a fine, community service, a suspended prison sentence or a combination of the former. Our design furthermore included a control condition (N = 247) in which respondents were not presented with any predictions about Wilders' verdict. Half of these respondents read a story that the outcome of Wilders' upcoming trial was still completely unsure, while the other half was not presented any news about the prosecution at all.

After this experimental manipulation, respondents continued the survey with questions about a number of variables, including evaluations of the legal system and democracy. This part of the survey also included a manipulation check in which respondents were asked how likely it was that Wilders was to be acquitted on a scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely). The not guilty condition scored an average of 4.8 on this scale, while this was 4.3 for the control condition and 3.8 for the guilty condition. This significant difference (F(2, 1,067) = 25.77, p < 0.001) indicates that the manipulation was successful. At the end of the survey, all respondents were debriefed with the message that the predictions about Wilders' trial were completely fictional. Prior ethical clearance had been obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences of the University of Amsterdam.

Measures

To measure support for the legal system, our study included two different evaluations of this institution. The first asked respondents to indicate their confidence in the legal system on a 7-point scale, while the second asked respondents to rate their satisfaction on a similar scale. Confidence and satisfaction are theoretically viewed as highly related, but nonetheless distinct, aspects of political support (Norris Reference Norris1999). Our respondents however did not appear to make this distinction, since the correlation between confidence and satisfaction was 0.71 in this experiment and even higher in the quasi-experiment and panel study discussed below. We therefore combined both aspects of support into a single scale with a highly satisfactory Cronbach's alpha of 0.83. Support for democracy was measured using a single item that asked respondents to rate their satisfaction on a 7-point scale, since no measure on confidence in democracy was available to us.

Attitudes about the multicultural society were measured using four items on a 7-point scale. An example of an item is ‘Foreigners and ethnic minorities should completely adjust to Dutch culture.’ The items were averaged into a scale that had an acceptable Cronbach's alpha of 0.72. Based on respondents' z-scores on this scale, we divided them into three equally large attitude groups: multiculturalists (z-score below −0.43), moderates (z-score between −0.43 and 0.43) and assimilationists (z-score above 0.43). This approach allowed us to ensure that the sample size and statistical power were comparable and sufficient in all three groups. Furthermore, placing the cutoff for the assimilationist group at the 33rd percentile corresponds to the observation that roughly one-third of citizens clearly opposes immigration and multiculturalism in typical survey items (for example, Van der Brug and Van Spanje Reference Van der Brug and Van Spanje2009). An overview of all survey items and descriptive statistics is displayed in Appendix 1.

Strategy of analysis

Due to our experiment's between-subjects design, with only a post-test of the dependent variables, the analyses consisted of a comparison between the guilty condition and the control condition. The not guilty condition was not used to test our hypotheses, because the theory did not provide us with clear expectations about how respondents in this condition would react to the stimulus. Instead, this condition was included as an exploratory reference with a smaller number of respondents. The aforementioned random variations in Wilders' sentence in the guilty condition were also excluded since the present study has no research questions on the differential impact of various sentences. Likewise, we made no distinction between the two random variations within the control condition (that is, no prediction about the verdict or no news about the trial). All analyses were conducted using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with heteroscedasticity robust standard errors.

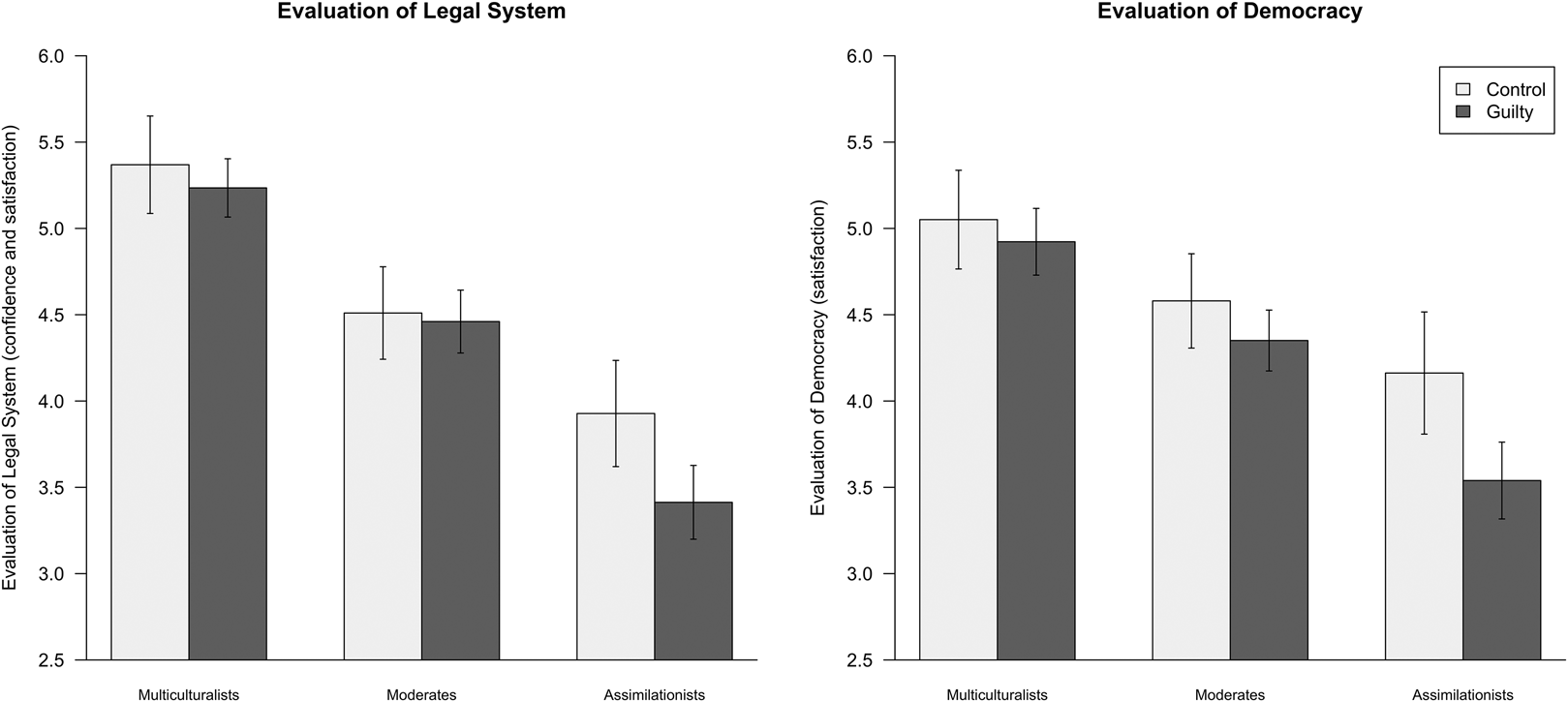

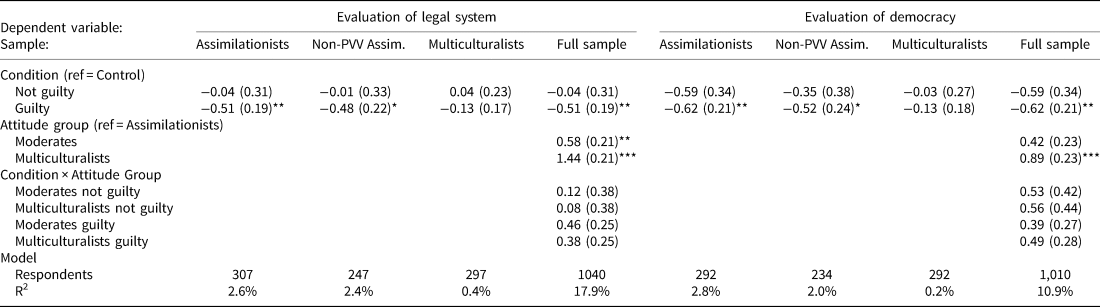

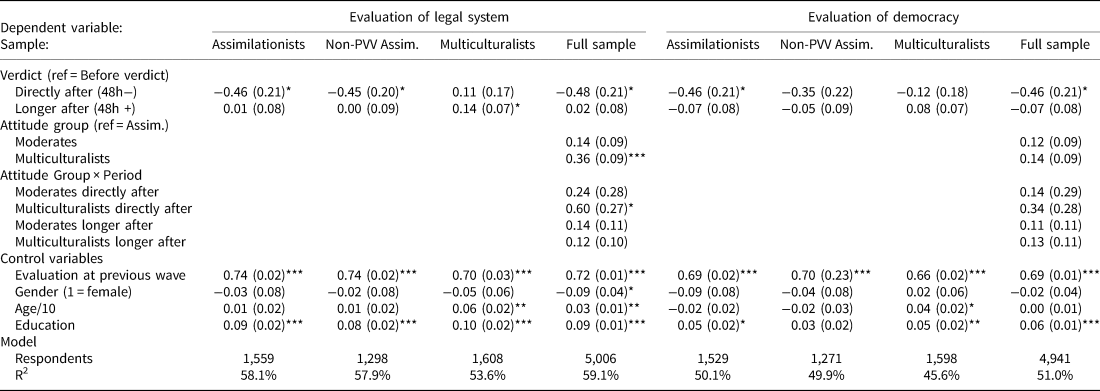

Results

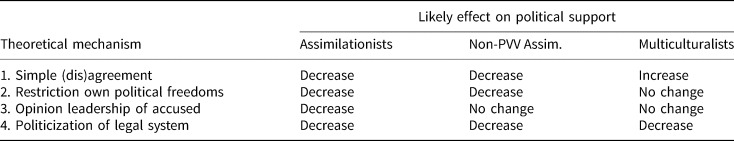

We analyzed our data in four subsequent regression models, as reported in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 1. A first model compared evaluations of the legal system and democracy between the conditions for assimilationists only. As hypothesized (Hypothesis 1), assimilationists who read a message about Wilders' upcoming conviction (that is, the guilty condition) were significantly more negative about both the legal system and democracy compared to assimilationists in the control condition. The effect sizes on a 7-point scale were considerable: 0.51 for the legal system (0.33 times the standard deviation) and 0.62 points for democracy (0.40 times the standard deviation). Our second model repeated this analysis with the exclusion of respondents who had voted for the PVV in 2012. The results were highly similar to those of the first model, which confirmed our hypothesis (Hypothesis 2) that a conviction of Wilders would have an adverse effect not only among his electorate, but among everyone who agrees with his statements. A third model repeated the analysis for multiculturalists, which revealed no significant differences between the conditions. This rejected our hypothesis (Hypothesis 3) that multiculturalists would raise their evaluations of the legal system and democracy in response to a guilty verdict. An analysis of the entire sample finally revealed that the expected interaction between condition and attitude group was not significant. This is likely due to the fact that multiculturalists did not show the hypothesized positive response.

Figure 1. Survey experiment: evaluations of the legal system and democracy by experimental condition and attitude group

Table 2. Results of the survey experiment

Note: unstandardized parameters with standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

Discussion

This survey experiment clearly demonstrated that the prospect of a guilty verdict for Wilders decreased evaluations of the legal system and democracy among assimilationists, regardless of whether they had voted for him. At the same time, we found no indication of a favorable response to the verdict among multiculturalists. These findings clearly demonstrate that prosecuting hate speech can have a causal impact on evaluations of the legal system and democracy. However, survey experiments are inevitably conducted in a rather artificial context, and their findings do not always translate to real-world events (Barabas and Jerit Reference Barabas and Jerit2010). Our quasi-experiment therefore examined whether these findings could also be observed in a real-world situation when Wilders was actually convicted a few days later.

Study 2: quasi-experiment

Method

Sample

For our quasi-experiment, we used data from the LISS panel (Langlopende Internet Studies voor de Sociale Wetenschappen), a nationally representative survey of about 15,000 respondents who regularly participate in online surveys on a variety of issues, including an annual wave on political issues. Respondents were recruited as a probability sample of Dutch citizens aged 16 and over. Panel attrition was handled by selectively recruiting new participants who resemble the respondents who dropped out on key variables. The ninth annual wave on politics was released on 5 December 2016, which was coincidentally only four days before Wilders was found guilty of hate speech by a Dutch court on 9 December 2016 at 11:25 a.m. Of the 5,537 respondents in this wave, 1,671 (30.2 per cent) completed the survey in the four days leading up to the court verdict, 223 (4.0 per cent) participated on either 9 December after the verdict or on 10 December, while the remaining 3,643 (65.8 per cent) responded between 11 December 2016 and 31 January 2017.

Measures

Just as in the randomized experiment, evaluations of the legal system and democracy were measured with two survey questions. The first asked respondents to rate their ‘confidence’ in a variety of institutions on an 11-point scale, and the second did the same for their ‘satisfaction’. The unidimensionality of these items was again demonstrated, this time by a correlation of 0.87 between confidence and satisfaction for evaluations of the legal system and an association of 0.86 between both evaluations of democracy. The scales revealed a highly satisfactory Cronbach's alpha of 0.93 for the legal system and 0.92 for democracy. To avoid endogeneity within the quasi-experimental design, attitudes about the multicultural society were used from the eighth wave of the LISS panel, which was administered a year earlier. The scale consisted of eight items on a 5-point scale. An example of an item is: ‘There are too many people of foreign origin or descent in the Netherlands.’ The scale had an adequate Cronbach's alpha of 0.75. As in the randomized experiment, three equally large attitude groups (assimilationists, moderates and multiculturalists) were constructed based on respondents' z-scores.

Strategy of analysis

A quasi-experiment is commonly defined as a research design that resembles a true experiment in all characteristics except complete randomization. Its core features typically include (1) a quasi-random source of variation, (2) a comparison group and (3) a pre- and post-test (Bernard Reference Bernard2012). For the quasi-random variation, this study used an interrupted time-series design that examines sudden discontinuities in time trends. Specifically, we determined if Wilders’ conviction of hate speech coincided with a sudden decline in evaluations of the legal system and democracy among assimilationists at precisely 11:25 a.m. on 9 December 2016. This study compared respondents who completed the survey before the verdict (5 December until 9 December before 11:25) with those who participated within 48 hours after the verdict (9 December after 11:25 a.m. or 10 December) or more than 48 hours after the conviction (11 December 2016 until 31 January 2017). In this design, exposure to Wilders' conviction introduces a quasi-random source of variation because substantial systematic differences are unlikely between respondents who completed the survey shortly before the event and those who did so directly thereafter. This strategy, which is known as the unexpected event during surveys design, has been used in a large and increasing number of quasi-experiments in recent decades (see Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2019 for an overview).

As a second feature of the quasi-experimental design, we created a comparison group by contrasting over-time discontinuities between assimilationists, moderates and multiculturalists. If adverse effects of Wilders' conviction are strongest for assimilationists, this provides further evidence that an over-time discontinuity surrounding his conviction may be viewed as a causal effect. Finally, our quasi-experiment could feature a pre- and post-test by using the eighth wave of the LISS panel, which was administered a year earlier. Alongside general control variables (that is, age, gender and educational level), effects were therefore controlled for respondents' evaluations of the legal system and democracy at an earlier time point. This allowed us to examine if respondents lost support after Wilders' conviction compared to their own evaluations a year earlier. Data were analyzed using regression analysis with (OLS) estimation and heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors.

Results

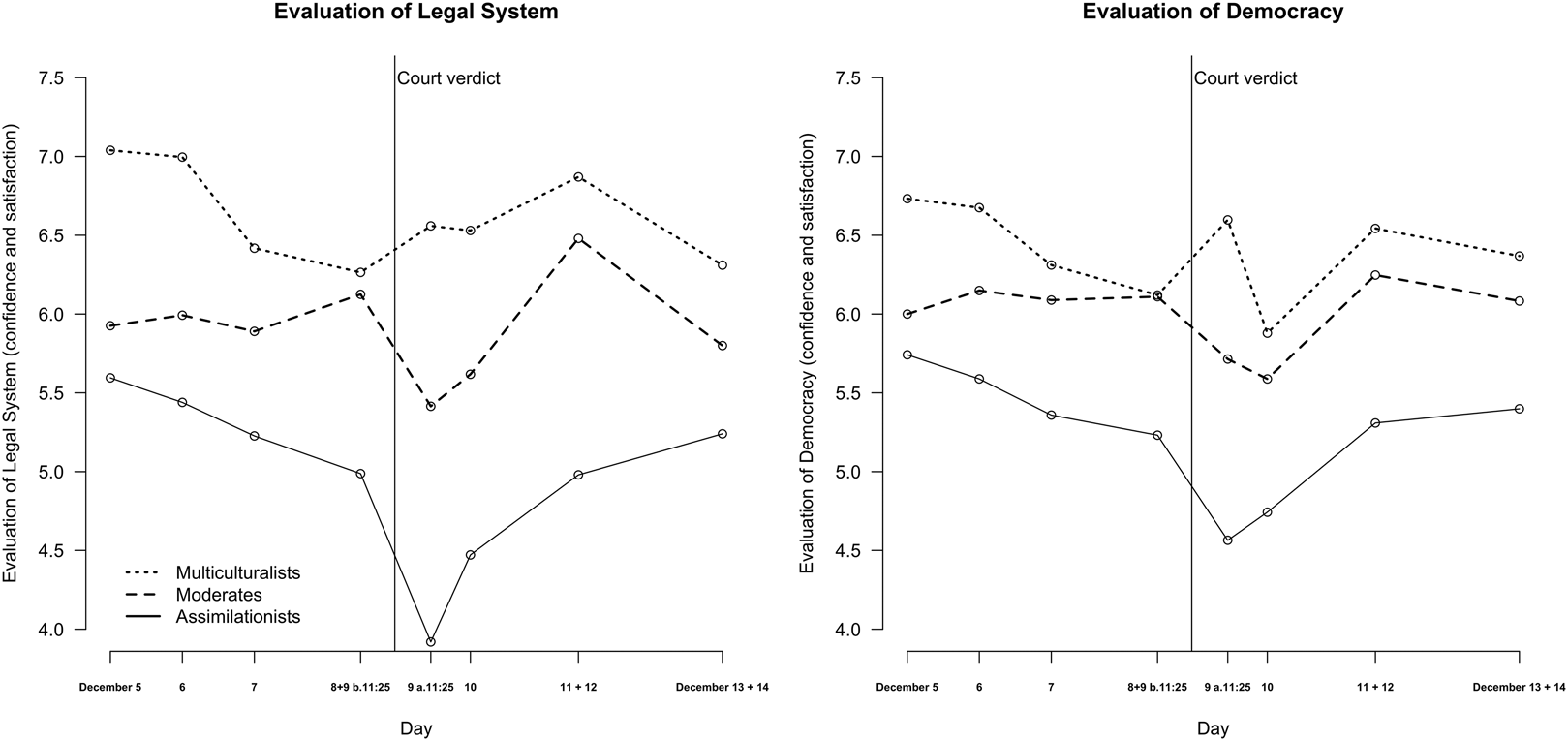

Before conducting our formal analyses, we explored the over-time development of the dependent variables in the days before and after the verdict as depicted in Figure 2. This graph shows a clear decrease in support among assimilationists after the conviction and a slight uptick among multiculturalists. To examine if these patterns were significant, we specified four regression models as displayed in Table 3. A first model compared the evaluations of assimilationists before and after the verdict. Compared to assimilationists who completed the survey before Wilders' conviction, assimilationists who participated in the 48 hours after the verdict were significantly more negative about both the legal system and democracy. This confirmed our hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) that Wilders' conviction would have an adverse effect on assimilationists' political support. The effect sizes on an 11-point scale were meaningful: 0.46 for both the legal system (0.22 times the standard deviation) and democracy (0.24 times the standard deviation). However, assimilationists who participated more than 48 hours after the conviction did not differ significantly from those who did so before the event.

Figure 2. Quasi-experiment: evaluations of the legal system and democracy before and after the verdict

Table 3. Results of the quasi-experiment

Note: unstandardized parameters with standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

A second model repeated this analysis, but with the exclusion of respondents who had voted for Wilders' PVV in the previous parliamentary elections. This exclusion did not substantially alter the effect of Wilders' conviction on either of the two dependent variables (that is, there was no statistically significant change in effect size), although the effect on evaluations of democracy was no longer significant in this model. As such, our hypothesis (Hypothesis 2) that adverse effects of Wilders' conviction would not be limited to his electorate was confirmed. A third model repeated the same analysis for the multiculturalists in the sample. Multiculturalists who participated in the first 48 hours after the verdict did not give significantly higher or lower evaluations of the legal system or democracy compared to those who participated before the verdict. As such, our hypothesis (Hypothesis 3) that multiculturalists would improve their evaluations of the legal system and democracy after Wilders' conviction was rejected. Multiculturalists who participated more than 48 hours after the conviction contrarily revealed increased support for the legal system. The delay however suggests that this increase was due to other factors, because it is unlikely that it would take citizens 48 hours to change their views in response to Wilders' conviction.

We finally conducted an analysis on the entire sample to examine interaction effects between attitude group and the moment of completing the survey. Results revealed that assimilationists and multiculturalists indeed revealed a differential shift in their evaluations of the legal system after the conviction. By viewing multiculturalists as a comparison group, this finding supports the interpretation that the decrease in evaluations among assimilationists indeed constitutes a causal effect of Wilders' conviction. However, a similar interaction was non-significant for evaluations of democracy.

Discussion

The findings of this quasi-experiment were highly similar to those of our survey experiment. Assimilationists lowered their evaluations of the legal system and democracy after Wilders was found guilty of hate speech (Hypothesis 1). However, this study also revealed that this decline may have been short-lived, as assimilationists' evaluations returned to their original levels after about 48 hours. Just as the survey experiment, this study also demonstrated that the loss of support among assimilationists was not limited to Wilders' voters (Hypothesis 2). Our third hypothesis was again rejected, since multiculturalists did not report a strengthened support (directly) after the conviction. This study therefore demonstrated that the causal effects identified in our survey experiment indeed generalize to a real-world context. Because the timeframe of this quasi-experiment was however limited to only a few weeks, our panel study examined to what extent these effects have persisted and accumulated over a more extended period.

Study 3: Panel Study

Method

Sample

Whereas our quasi-experiment used only a single wave from the aforementioned LISS panel, our panel study used all nine available waves. The first wave was administered between December 2007 and January 2008, while the last took place between December 2016 and January 2017. A wave from early 2015 could not be used because it did not include measures of political support. A total of 15,067 respondents participated in at least one wave and in 3.6 waves on average. The LISS panel provided us with a representative sample of Dutch citizens who were interviewed during the entire period of the first hate speech trial against Wilders and the second trial until his conviction in 2016.

Measures

Evaluations of the legal system and democracy, as well as attitudes about the multicultural society, were measured with the same items that were used in the quasi-experiment. As a control variable, support for the government and parliament were measured with the same ratings of confidence and satisfaction that were used for the legal system and democracy.

Strategy of analysis

The main purpose of our panel analysis was to determine if the history of Wilders' prosecution co-occurred with changes in support for the legal system and democracy. The main independent variable was therefore a construct that reflects how many events had passed in Wilders' prosecution at each point in time. In 2008 and 2009, this variable had a value of 0 because no hate speech prosecution against Wilders had yet occurred. Because the first trial against Wilders was initiated in 2009, this variable took a value of 1 from 2010 until 2014. Because a second trial against Wilders' commenced in 2014, the value of the independent variable was raised to 2 for 2016 and 2017. This variable therefore allowed us to roughly determine if changes in political support co-occurred with the events surrounding the hate speech prosecution of Wilders.

Because over-time changes in support may occur for many other reasons than hate speech prosecution, all models controlled for a linear time trend and for respondents' support for the government and parliament in every year. Evaluations of different institutions are typically strongly interrelated (Dalton Reference Dalton2004), but legal prosecution may affect evaluations of the legal system and democracy more than support for other institutions. Including support for the government and parliament in the model therefore allowed us to control to a certain extent for other events that may have affected political support more generally. All data were analyzed using fixed-effects longitudinal regression analysis with OLS estimation and heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors. In this context, a fixed-effects model (for example, Allison Reference Allison2009) examines what predicts over-time variation in political support within individuals, by estimating an individual intercept for each respondent to control for all between-individual variation.

Results

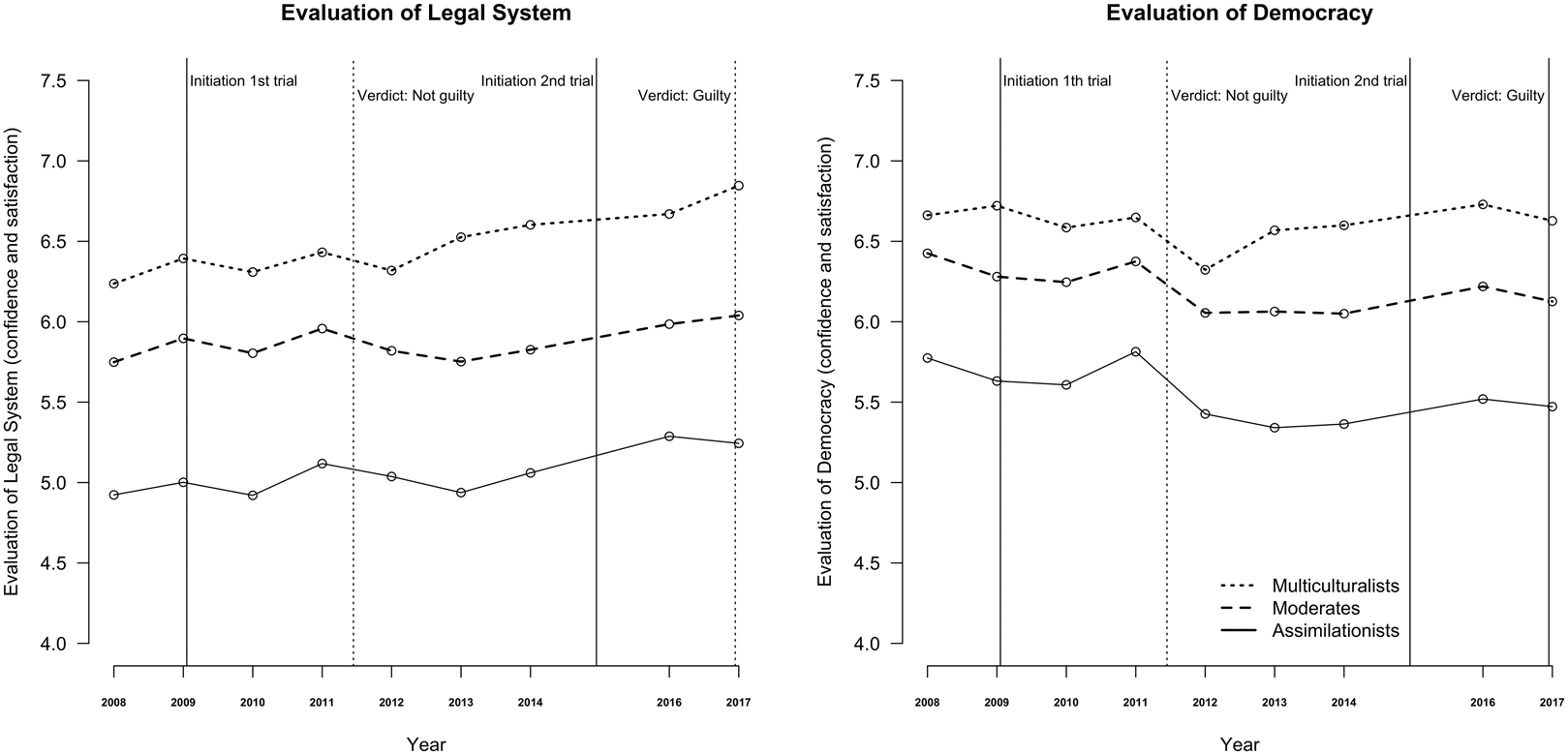

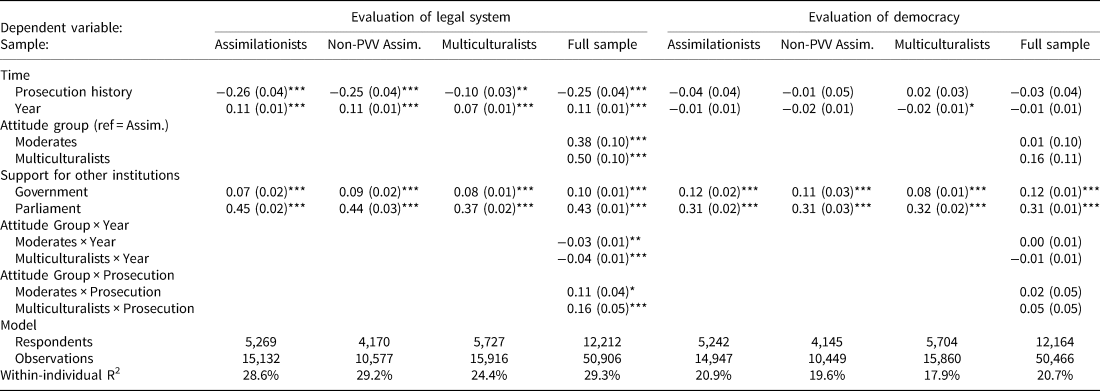

To facilitate the interpretation of our main analyses, we first explored the over-time development of support for the legal system and democracy among assimilationists, moderates and multiculturalists. Figure 3 demonstrates that no clear changes in support co-occurred with the main events in Wilders' prosecution. The only visible shifts in support seem to have occurred during his cooperation with the government coalition between 2010 and 2012.

Figure 3. Panel study: over-time development of evaluations of the legal system and democracy.

For our main analyses, we conducted four regression models as reported in Table 4. The first model analyzed assimilationists to examine our hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) that legal action against Wilders undermined their political support between 2008 and 2017. As expected, the prosecution history had a negative effect on evaluations of the legal system. However, no such effect was found for evaluations of democracy. The second model obtained the same results after excluding PVV voters from the analyses, which confirmed our hypothesis (Hypothesis 2) that the adverse effects of legal action were not limited to Wilders' electorate. This model excluded all respondents who had voted for the PVV in any of the three general elections in which it had contested (2006, 2010, or 2012). The third model surprisingly showed that multiculturalists also lowered their evaluations of the legal system, but not democracy, as Wilders’ prosecution progressed. This finding directly contradicts our hypothesis (Hypothesis 3) that Wilders' prosecution would have strengthened support among multiculturalists. Finally, a model on the entire sample revealed the expected interaction between attitude group and prosecution history for evaluations of the legal system. Although the prosecution revealed a negative effect on support for both assimilationists and multiculturalists, this effect was substantially stronger among assimilationists.

Table 4. Results of the panel study

Note: unstandardized parameters with standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

Discussion

Following our survey experiment and quasi-experiment, this panel study again yielded support for our hypotheses that Wilders' prosecution has negatively affected political support among Dutch assimilationists (Hypothesis 1), regardless of whether they voted for the PVV (Hypothesis 2). Our main analyses revealed that his prosecution had a negative effect on evaluations of the legal system among assimilationists, even though this pattern was not visible at a descriptive level. This means that assimilationists' support for the legal system was lower after the prosecution than was to be expected based on a general time trend and based on concurrent support for other institutions (even though assimilationists did not lower their support in absolute terms). These effects were furthermore limited to evaluations of the legal system, since no similar patterns were found for evaluations of democracy. Despite these mixed findings, the results of this panel study are compatible with the idea that assimilationists' evaluations of the legal system were negatively affected by Wilders' prosecution. While our experiment and quasi-experiment demonstrated a causal effect of hate speech prosecution, this panel study provided some indication that such effects may translate into a long-term erosion of support.

General Discussion

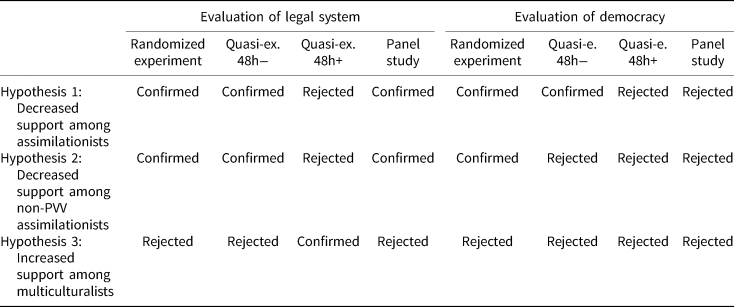

This study combined three research designs to examine whether the prosecution of politicians for hate speech undermines citizens' support for the legal system and democracy. The results of each study are summarized in Table 5. First and foremost, all three studies revealed that the prosecution of Wilders indeed damaged political support among Dutch assimilationists. Our survey experiment provided clear evidence for a causal link between hate speech prosecution and political support among this group. Such fully controlled experiments are inevitably conducted in rather artificial conditions, but our quasi-experiment revealed that these findings translate to the real-world context of a conviction. In addition, our nine-year panel study revealed the same link between hate speech prosecution and evaluations of the legal system over a much longer time span. By combining internal and external validity, these three studies together provided firm evidence for the conclusion that hate speech prosecution of a politician can damage political support among those who support the idea behind his or her statements.

Table 5. Overview of results

This study furthermore revealed that this adverse impact is not limited to the electorate of the prosecuted politician. Even after excluding Wilders' voters from the analyses, the effects among assimilationists never changed meaningfully and they remained significant in all but one instance. This suggests that hate speech prosecution can diminish political support among a very substantial number of citizens. Whereas only a limited number of people may vote for the prosecuted politician (for example, the 13 per cent that voted for Wilders in 2017), the affected group may consist of many more citizens (for example, the one third that rejects immigration; Van der Brug and Van Spanje Reference Van der Brug and Van Spanje2009). This study moreover revealed downward trends in political support among respondents with a moderate stance on multiculturalism. Although these trends never reached statistical significance, this hints that the group that lowered its support in response to Wilders' prosecution may have been even larger, rather than smaller, than the 33.3 per cent of the Dutch electorate that we classified as assimilationists.

The results however refuted our hypothesis that hate speech prosecution would enhance political support among those who oppose the idea behind the accused's statements. In all but one instance, multiculturalists' evaluations of the legal system and democracy remained highly constant after Wilders' prosecution. We see two possible explanations for this stability. A first explanation is that the legal action against Wilders may not have been important enough for multiculturalists to alter their evaluations of key institutions, even if they agreed with the endeavor. This may be related to the phenomenon known as negativity bias that citizens' attitudes are often less responsive to positive information than to negative information (Pratto and John Reference Pratto and John1991). Consistently, research on the US Supreme Court reveals that increases in support for this institution among citizens who agree with a decision are typically weaker than the loss of support among those who disagree (Grosskopf and Mondak Reference Grosskopf and Mondak1998). As a second explanation, multiculturalists' high base levels of political support may have caused a ceiling effect so that there was little opportunity for scores to increase further. Put differently, multiculturalists may have already evaluated the legal system and democracy so favorably that they had little reason or opportunity to increase their support even further when Wilders was prosecuted.

This study departed from four theoretical mechanisms that may link hate speech prosecution to political support: (1) simple (dis)agreement, (2) restriction of own political freedoms, (3) opinion leadership of the accused politician, and (4) politicization of the legal system. We used these four accounts to derive and test predictions for different groups of citizens as summarized in Table 1. Although it was not an aim of this study to test which specific mechanism links legal action to political support, we may get some indication by comparing the predictions for each group in Table 1 to the results in Table 5. This comparison clearly reveals that the second mechanism best predicted our results, which hints that Dutch assimilationists may have lowered their political support due to a perceived restriction of their democratic rights to free speech and representation. This interpretation would explain why assimilationists who did not vote for the PVV lowered their support about as much as Wilders' electorate. Moreover, this account would explain why multiculturalists did not alter their support in response to the prosecution as their political rights were neither restricted nor enhanced. It however remains an important task for future research to take a more in-depth look at this explanatory mechanism.

Although this study clearly revealed that hate speech prosecution can diminish political support, an important question remains how long this decline lasts. This study shed some light on this matter by combining designs with different time spans, but it did not provide a definitive answer. The survey experiment revealed a decreased political support immediately after exposure to news about hate speech prosecution and the quasi-experiment indicated that this drop persists for at least 48 hours after a conviction. What happens after this period is less clear. On the one hand, the quasi-experiment revealed that political support returned to its initial level after about 48 hours. On the other hand, the panel study revealed that the accumulated events of Wilders' prosecution were associated with lower levels of support for the legal system among assimilationists across the nine survey years. This hints that several years of repeated exposure to news about Wilders' prosecution may have accumulated into long-term discontent among Dutch assimilationists. However, this interpretation remains somewhat speculative as a panel study allows for many alternative causal explanations. It therefore remains a crucial challenge for future research to determine for how long legal action can alter political support. Without a doubt, this matter will be crucial to understanding the potential risks of hate speech prosecution.

An obvious limitation of this examination is that it was a case study on the prosecution of just one politician. Future research will have to determine if the same patterns occurred during other instances in which politicians were prosecuted for hate speech. However, we see little reason why citizens would react very differently in other instances that resemble the case of Wilders on relevant characteristics. Such characteristics may include for example that the accused's statements relate to immigration, that these statements are acceptable to a large number of citizens, and that the defendant is the leader of a major political party. Future studies could also examine if the same impact on political support that we observed for the prosecution of a politician can also be found in other legal cases with a political dimension (for example, party bans) or for other restrictions on free speech (for example, measures against online hate speech).

Conclusion

The prosecution of politicians for hate speech arises out of a tension between two core principles of liberal democracy: freedom of speech and the protection of minorities. This study examined how such trials affect support for the legal system and democracy. Taken together, the findings paint a grim picture. When an anti-immigration politician is prosecuted for hate speech, the political support of assimilationists may be undermined. This is particularly concerning because this group is already characterized by substantial political discontent. Causing more reason for concern, this impact may not be limited to the electorate of the accused politician, it may not be accompanied by an increased support among multiculturalists, and it may potentially persist over an extended period. Of course, this study alone cannot answer the question if hate speech prosecutions of politicians ought to happen, which depends on a wide variety of normative and empirical considerations. Nonetheless, this study demonstrated that the impact of such prosecutions on political support is one of the concerns that may inform this normative debate. Although several important questions remain to be answered by future research, this study revealed that hate speech prosecution can potentially damage the democratic system it is intended to defend.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342000068X.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tom van der Meer, Rachid Azrout and all participants of two internal seminars at the University of Amsterdam for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Data availability statement

All syntax files and the dataset for replication of the survey experiment are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VZPMC2. The data that was used for the quasi-experiment and the panel study can be obtained from CentERdata: https://www.lissdata.nl.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) with a VIDI grant awarded to Dr Joost van Spanje (Project Number: 452-14-002).

Ethical standards

The randomized experiment was approved by the IRB of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences of the University of Amsterdam.