‘Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine on a grand scale.’ (Rudolph Virchov, 1848, quoted in Reference Link and PhelanLink & Phelan, 1996)

Discrimination and prejudice against people with mental illnesses is ubiquitous, pernicious and wrong. The overwhelming case against such stigma has been recognised by initiatives from the UK government, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the US Surgeon General, the World Psychiatric Association and many other organisations.

Such top-down initiatives are also reflected in the concern of practising psychiatrists. To most of us, the growing body of research on the stigma of mental illness only confirms what we already know from clinical practice and personal experience.

For example, prejudice against those with mental illness increases social isolation and is a source of harassment and discrimination in employment, housing and insurance (Reference ByrneByrne, 1999; Reference Corrigan, River and LundinCorrigan et al, 1999). Having a mental illness adversely affects situations as diverse as prisoners being granted parole (Reference Miller and MetznerMiller & Metzner, 1994) and patients being offered suitable organs for transplant (Reference Corley, Westerberg and ElswickCorley et al, 1998).

Stigma means that people are reluctant to present with psychiatric problems to primary care and often default from specialist services (Reference VanVan, 1996; Reference WhiteWhite, 1998). This might partly be a response to negative attitudes expressed by general practitioners (Reference Lawrie, Parsons and PatrickLawrie et al, 1996, Reference Lawrie, Martin and McNeill1998) and hospital medical and nursing staff (Reference Fleming and SzmuklerFleming & Szmukler, 1992). Not surprisingly, this discrimination adversely affects social behaviour and damages self-confidence (Reference Gilbert and CrispGilbert, 2000). Such findings prompt two obvious questions: is it possible to act against stigma? And if so, what is the best way to go about it?

This paper outlines some of the themes that emerge from stigma research, describes how such themes can inform practical anti-stigma interventions and lists some impediments to anti-stigma work.

The origins of stigma

There is no generally accepted ‘unitary theory’ of stigma. This is perhaps not surprising, since stigma represents a complex interaction between social science, politics, history, psychology, medicine and anthropology. None the less, there are some clear indicators of the social origins of stigmatisation and the factors that perpetuate it.

The key step in the generation of stigma is the perception of difference. A predisposition to notice difference is probably innate in all human (and many animal) groups, since they depend on the predictable behaviour of their members for their functioning and safety.

We should perhaps not be surprised, therefore, when groups notice those who are different or respond vigorously to what is perceived as a threat. Most differences between people are ignored as irrelevant. Yet some characteristics – most typically age, gender and skin colour – are taken to represent ‘natural’, or objective, categories of difference.

For stigmatisation to occur, such differences must be linked to undesirable traits. For example, part of the stigma of mental illness lies in the association of illness with stereotypes of potential violence, communication problems and unpredictability. These individuals are characterised as a ‘them’, quite different from ‘us’. Such stigmatised out-groups typically lack power, and their social status decreases owing to a combination of overt and less obvious mechanisms.

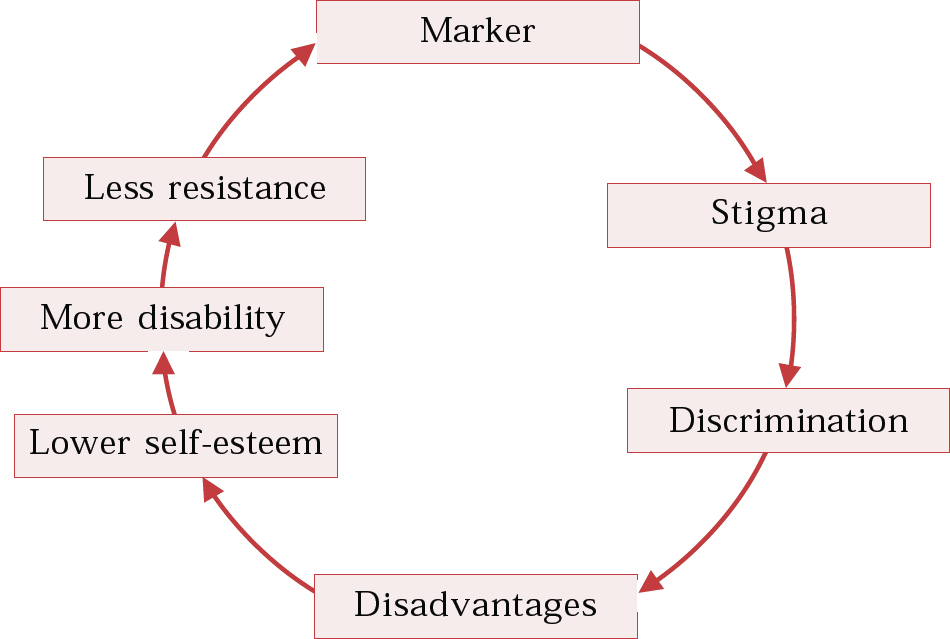

Sartorius terms these the ‘vicious cycles’ of stigma (further details available from the author upon request) and argues that they not only operate through individuals and their families, but also contaminate mental health services and psychiatric research. Sartorius describes, for example, how individuals are ‘marked’ with a stigmatising trait. They are then discriminated against and disadvantaged. The resultant reduction in self-esteem increases disability because they have less access to social and financial resources. As the cycle continues, the individual has diminished reserves to resist stigmatisation, and so the cycle repeats, intensifying and entrenching stigma as it does so (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Cycles of stigma (after Sartorius, 2001)

Although stigma is discussed here as a single concept, there may in fact be a range of diverse ‘stigmas’. It is likely, for example, that the sources and dynamic involved in the stigmatisation of alcoholism are very different from those that relate to postnatal disorders. It is worth remembering that some stigmatisation, such as that against criminal activity, serves useful social functions.

Similarly, the origins of stigma in different cultures will differ. There is some evidence that a shift in stigma attitudes is already taking place in the West. For example, disorders such as depression are significantly less stigmatising now than they were 10 or 20 years ago. Books about depression have become commonplace – Listening to Prozac (Reference KramerKramer, 1994), Prozac Nation (Reference WurtzelWurtzel, 1995), Darkness Visible (Reference StyronStyron, 1990) and Malignant Sadness (Reference WolpertWolpert, 1999) all became best-sellers. This positive change is reflected in popular magazines (Reference Wahl and KayeWahl & Kaye, 1992), although there are also concerns that illnesses like depression have become trivialised (Reference JamesJames, 1998).

Three themes in stigma intervention

Rights-based protest: tackling discrimination

People stigmatised because of mental illness are a group who are wrongfully shamed, humiliated and marginalised. It is recognised that this kind of stigma is applied to other ‘minorities’: people discriminated against because of gender, race, sexual orientation or disability. The College makes an explicit connection with ‘rights issues’ faced by such groups: ‘We aim for the same success as that achieved against discrimination based on race, gender and sexuality’ (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1998).

A rights-based approach would seek to counter discrimination by monitoring and enforcing equal access to health care, housing, employment and justice. Achieving equality of this kind might then be expected to achieve practical improvements not only in daily life, but also in self-confidence and social inclusion.

This kind of intervention has a number of benefits. Most important, it is underpinned by moral authority and so does not depend on familiarity, understanding or affection towards the stigmatised group. Second, it does not depend on persuasion or concealment but can insist on the enforcement of rights. (This is the reason why discourse on rights is replete with military metaphors such as ‘campaigns’, ‘battles’ and ‘fights’.) Third, it is a practical course of action, with measurable outcomes.

For example, it has been argued that British mental health legislation ‘discriminates against patients with a mental disorder, supporting prejudicial stereotypes of difference, incompetence and dangerousness’ (Reference Szmukler and HollowaySzmukler & Holloway, 1999). A rights-based approach would target such alleged discrimination. Legislators are amenable to persuasion: ‘non-discrimination’ is one of the principles underpinning the Scottish Mental Health Act currently going through the Scottish Parliament and there has been a call to introduce anti-stigma campaigns to support it.

One critical aspect of rights-based campaigns is that they do not require a change in attitudes. Writing about the institutional racism permeating London's Metropolitan Police force, Ignatieff makes a relevant point:

‘Borrowing from Isiah Berlin, let us distinguish between positive and negative tolerance. Negative tolerance is the minimum we require in a liberal society … but we do not need to love each other, reach out to each other, or even particularly value our different cultures. A minority will practice such positive tolerance, and, as time passes, that minority will become a majority’ (Reference IgnatieffIgnatieff, 1999).

In the context of psychiatric stigma, such social and political equality would be predicated on a shared understanding of ‘the right to be different’. The limits of such difference, which might include changes in appearance or behaviour, or changes in ability at work, or risk to self or others, would need to be determined by society over time.

Normalisation

A recurrent strand in anti-stigma work is the premise that people with mental illness are ‘just like us’. For example, the College's anti-stigma campaign ‘Changing Minds: Every Family in the Land’ (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/campaigns/cminds/index.htm) emphasises the high prevalence of mental disorder. Mental illness, says the campaign's slogan, affects ‘one in four’ of us, effectively ‘every family in the land’. This approach differs from the rights-based campaign in that it targets acceptance, rather than equality. There are two potential problems with this strategy.

First, it risks confusing ‘frequency’ (many disorders are common) with ‘fairness’ (all people deserve equal treatment). Rare disorders are, of course, just as deserving of acceptance as common ones.

A second problem is that even people who are not ‘just like us’, such as those who have cognitive impairment as a result of schizophrenia or people who have not fully recovered from illness and require help in everyday living, still have rights and still deserve our respect. Although it may not be possible for societies to ignore differences between people, they should be able to accept them.

One aspect of this normalising approach is the medicalisation of mental illness. We have long known that disease has always had the potential to arouse ‘thoroughly old-fashioned kinds of dread’, even among relatives and friends of those affected (Reference SontagSontag, 1991). None the less, illnesses like tuberculosis and cancer became less stigmatised as scientific knowledge and medical treatments improved.

More than 250 years ago, the physician George Cheyne hoped that the ‘English malady’ (of ‘nervous disease’) might one day be medicalised, so that it was considered ‘as much a bodily distemper… as is the smallpox or a fever’ (Reference Cheyne and PorterCheyne & Porter, 1990). More recently, Kendell argued that:

‘Not only is the distinction between mental and physical illness ill-founded and incompatible with contemporary understanding of disease, it is also damaging to the long-term interests of patients themselves. It invites both them and their doctors to ignore what may be important causal factors and potentially effective therapies; and by implying that illnesses so described are fundamentally different from all other types of ill-health, it helps to perpetuate the stigma associated with “mental” illness’ (Reference KendellKendell, 2001).

Although we might hope that mental illness may one day be considered to be ‘no worse a label than heart disease, diabetes or multiple sclerosis’ (Reference PorterPorter, 1998), this argument has so far failed to convince the general public (Anonymous, 2001).

Although there is evidence that the public are more willing and able now to recognise conditions such as schizophrenia or depression as mental illness than they were in the 1950s, a strong stereotype of dangerousness and a desire for social distance persist (Reference Link, Phelan and BresnahanLink et al, 1999). This may be because mental illness is commonly perceived as being a ‘trait’ (an enduring characteristic of the individual) rather than merely a ‘state’ (of temporary change induced by illness). Unlike most physical illnesses, mental disorder is commonly perceived to be the result of weakness or failure.

There are also important qualitative differences between physical symptoms such as dyspnoea and mental ones such as disinhibition. The symptoms of acute mental illness, which might include adverse changes in personality, behaviour, judgement and speech, are inherently more stigmatising than those of physical illness.

This is not to argue that normalisation and medicalisation are counterproductive strategies, since better treatments and improved outcomes would be a powerful destigmatising influence (and may already have had an effect in Western societies). However, we should encourage a holistic approach to our understanding of mental illness that extends beyond biomedical models.

Information, media and social attitudes

The media have a powerful influence on attitudes towards mental illness and it is therefore not surprising that they should feature so prominently in anti-stigma programmes. Although the intense media interest in psychiatric topics offers a tantalising opportunity to convey an ‘anti-stigma’ message, the outcomes of media intervention are often disappointing.

While short-term interventions using films and literature may change self-reported attitudes, the evidence for longer-term behavioural change is very weak. This may be because adverse stories are the result not simply of media sensationalism, but of a more subtle collaboration between the assumptions of both journalist and reader (Reference Allen and NairnAllen & Nairn, 1997).

Journalism depends on narrative and this often involves selection of facts, interpretation and exaggeration. The media, of course, has an instinctive bias towards reporting the strident or the extreme. While marked bias may lead to distortion, most journalism is not dishonest or manipulative per se. Reporting a story in a way that failed to start from, or work with, existing attitudes is likely to be perceived as propaganda. It would be naïve to expect the media to act as ‘educators’, unless this represented a story in itself.

This is not to excuse stigmatising material in the media, but rather to seek to understand how it comes to be published. These adverse stories, and there are plenty of examples, involve stereotypes and misunderstandings that closely reflect the ignorance and prejudices of the audience. Journalists and broadcasters are generally not cynical propagandists and modifying adverse media stories will depend ultimately on influencing broader population attitudes and beliefs about mental illness.

Why should popular attitudes about mental illness be so stigmatising? Several models have been proposed that seek to understand the negative perceptions of mental illness. For example, a psychodynamic stance argues that we project ‘feelings we find unattractive or shameful to the disadvantaged, including the mentally ill … [we] feel sorry for them or even contemptuous, and thereby distance ourselves from them’. Such projected characteristics are likely to include ‘a sense of incompetence or failure, irresponsibility, irrational and aggressive behaviours, feelings of despair, and perhaps dependency, and a need for care’ (Reference Hughes and CrispHughes, 2000).

Gilbert (2000) describes an evolutionary perspective, in which Darwinian selection pressure would mitigate against mating with both ‘genetic poor bets’ (risk of damaged offspring or kin) and ‘co-operative poor bets’ (whose lack of altruism might be deleterious to the group).

The social and group context of interaction with people who have mental illnesses is also important. Crucially, people are more likely to describe positive attitudes when giving their own opinions than when expressing those of the group (Reference Angermeyer and MatschingerAngermeyer & Matschinger, 1992), even when this contradicts their personal experience (Reference PhiloPhilo, 1996). Eminson (2000) points out that ‘our responses to the mentally ill may be tempered by contextualisation, by a lack of a sense of threat and by confidence in how to respond to the person whose perceptions we cannot share’.

The language used both in the media and in everyday speech is relevant, particularly in informing us about the attitudes and beliefs of the stigmatiser. While it would be a mistake to try to impose an Orwellian ‘Newspeak’, cleansed of potentially offensive words, it is important to try to ensure that certain words retain their uncontaminated meaning. My personal preference would be to distinguish between clinical terms such as ‘schizophrenia’ and ‘psychosis’ and vernacular descriptors such as ‘loonies’, ‘nutters’ and ‘madness’. Clinical words need to retain their specific meaning if we are to communicate effectively about diseases. For example, we should actively seek to prevent schizophrenia (or its derivative ‘schizo’) being used to mean ‘split personality’ or psychosis/psycho to mean ‘violent’. By contrast, almost all of us, professionals, carers and service users alike, use phrases like ‘that's crazy’, or ‘she's losing the plot’ in everyday speech. Attempting to modify this kind of talk is unlikely to succeed and is probably counterproductive.

How to do it

Stigma is a complex phenomenon that is modified by the culture and contexts in which it occurs. Changing beliefs and behaviours has always been difficult and cannot be done quickly. For these reasons, generalising the results of anti-stigma research and generating meaningful outcome measures from short interventions is problematic. This should not prevent us from acting: as outlined above, the moral and political imperative to act against stigma persists, even if a comprehensive evidence base is still being established. Some principles are outlined in Box 1 and some of the difficulties of change in Box 2.

Box 1 Some principles

The goal is acceptance of difference, not normalisation or denial of difference.

We should seek to enable people to believe their own experience, rather than rely on stereotypes portrayed in the media and elsewhere.

Risks should be acknowledged, but put in context. There is a small but significant risk of increase in violence in schizophrenia, and it is not believable to ignore this, nor reassuring to hear these concerns dismissed. ‘Medicalising’ the stigma of mental illness is a useful, but limited, strategy: we need to encourage an understanding of mental illness that extends beyond disease models.

The media follow public opinion, rather than leading it. Complaining about the language and attitudes expressed by the media usually means describing the language and attitudes of the public.

The stigma against psychiatry and psychiatrists echoes most of the factors relating to stigma against those with mental illness: we should not be afraid to defend our profession.

Box 2 Some difficulties in change

Apathy

Doctors are used to effecting medical change in individuals, not influencing cultural change in populations. The very scale of the task is daunting, and expecting rapid and profound changes is unrealistic and probably counterproductive (Reference Stuart and Arboleda-FlorezStuart & Arboleda-Florez, 2001). Change, when it happens, will be slow.

Antipathy

Stigma is not always easy to identify, especially when it is ‘close to home’. Although we may feel that we are personally accessible and accepting, the experience of many patients is less positive.

Autonomy

If people with mental illnesses should not be marginalised in society, they certainly should not be alienated in the consultation or in planning services. Yet organisations are poorly equipped to consult with their users.

Anti-psychiatry

This movement reflects a more sceptical public view of medical authority, a change that doctors often find uncomfortable (Reference KendellKendell, 2000). To some extent, psychiatry's problems are compounded by past mistakes. Changing this will require active outreach and engagement.

Although research into the effectiveness of anti-stigma measures continues, there is a broad consensus that the following factors are both relevant and effective. These points should therefore underpin any anti-stigma strategy.

Start from what people know, not from what you want them to think

Simply imparting accurate information is not likely to be successful unless people's own beliefs, understanding and concerns are taken into account (Reference SeckerSecker, 1999). The lay understanding of health can often diverge significantly from what professionals think that people know.

For example, a study of Scottish schoolchildren's perceptions of mental health (Reference Armstrong, Hill and SeckerArmstrong et al, 2000) showed that, while most children could define either ‘mentally’ or ‘healthy’, the phrase ‘mentally healthy’ just was not understood. In other studies, general education about schizophrenia was much less useful than targeting information about dangerousness (Reference Penn, Guynan and DailyPenn et al, 1994).

Target the audience

Young people are a particularly important group, not only because their opinions and knowledge will determine future attitudes, but also because of the high prevalence of mental health problems in childhood and adolescence. Not only are children and young people interested in this area, but they also need accurate information. Local needs should direct anti-stigma initiatives: for example, in some areas, this might mean improving liaison with the local accident and emergency department; in others it might involve improving training for staff at the benefits agency.

Plan, and act, for the long term

Many interventions have shown marked short-term improvement in reported attitudes, but maintaining this effect is a major challenge. Significant changes in behaviour and systems take place so slowly that they are difficult to measure, but this should not deter anti-stigma programmes from planning for the long term.

Multi-agency working

User, carer and voluntary sector involvement is crucial. ‘A quality service would … treat patients and service users with dignity, creating the right environments for them to recover from illness and being guided by their views on how services should develop’ (Reference ApplebyAppleby, 2000). Initiatives from the ground up should be encouraged, particularly where these coordinate with ‘top-down’ projects, such as advertising or educational campaigns.

Act simultaneously across several domains

Anti-stigma initiatives in public education, media, legislation and academic research tend to support and cross-fertilise each other. Promoting better mental health in advertisements, for example, will be perceived as propaganda unless there are services ready to back up the message with action.

Psychiatrists should be visible

The history of our speciality is not altogether positive. Byrne (2000) has argued in this journal that discredited psychiatric practices (for example treatments for homosexuality, eugenics, insulin coma treatment and frontal lobotomy) have contributed to current misunderstandings about mental illness. Psychiatrists have been criticised for their ‘neglectful and uncaring’ use of major tranquillisers (Reference BrittenBritten, 1998), and a recent document published by the British Medical Association (BMA), and and the Royal Colleges of Psychiatrists and of Physicians of London (Royal College of Psychiatrists et al, 2001) recognised that up to 40% of patients presenting to their general practitioners with mental health problems felt discriminated against. There is an active ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement through much of Europe and North America.

Such criticism needs to be acknowledged and tackled directly. In particular, psychiatrists need to be wary of feeling contaminated by association with adverse aspects of mental illness. For example, where services are poor, we should join with users and carers to try to improve them; where drugs have adverse effects, we should be honest about them, and try to promote patient choice. Unless the profession is able publicly to explain and defend our work and values, we risk being caricatured and stigmatised ourselves.

Conclusions

‘To prevent an effect from occurring at all requires a force equal to the cause of that effect, but to give it a new direction often requires only something very trivial’ (Reference LichtenbergLichtenberg, 2000: p. 136).

Clearly, stigma is important not only to the individual who is stigmatised. It is an integral part of systems, standards, institutions and legislation: it affects us all.

Although the stigma of mental illness may have been present for centuries, it has rarely been the focus of such social, political and academic scrutiny. From being a rather nebulous concept of little everyday interest to clinicians, stigma gradually seems more ‘concrete’, and we are coming to learn more about how to combat it.

Ironically, the increased interest in anti-stigma interventions may have come at a time when stigma itself is decreasing anyway – just as tuberculosis had already started to decline before the introduction of antibiotic therapy. The public have shown that they are prepared to accept differences in gender, sexuality and race. There may a ‘halo effect’ reducing the stigma of mental illness by association with this general increase in social tolerance.

However, we still need to act, rather than just wait. An ill-informed, fearful and intolerant society is unlikely to accept difference and will powerfully stigmatise those with mental health problems. Since this militates against early, effective or acceptable treatment, the stigmatising group will tend to create the kind of mental illness it most fears: untreatable, hidden and unpredictable. In this way, social factors actively modify illness, just as Virchov's quote, with which I began, predicted.

Stigma is not only an important issue in its own right but is also a vehicle through which the profession can improve its relationship with users and carers, improve the quality of mental health services and even enhance the self-esteem of psychiatry itself. There are optimistic signs that such positive changes are already taking place.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Stigma:

-

a is always a bad thing

-

b has never been shown to be changed by campaigns

-

c stereotypes relate most closely to people's own experience

-

d is dependent on humans noticing difference, just as other animal groups do

-

e is related to the general level of tolerance in society.

-

-

2. Being stigmatised means:

-

a often feeling discriminated against by doctors

-

b being more likely to attend psychiatric clinics

-

c feeling low in self-esteem

-

d maintaining better links with families and friends

-

e for prisoners, being more likely to get parole.

-

-

3. Psychiatrists:

-

a have a useful role to play in combating stigma

-

b are sometimes a stigmatised group themselves

-

c could help by improving the quality of services

-

d should always defend shortcomings in psychiatric treatment

-

e should avoid dealing with the media at all costs.

-

-

4. When planning anti-stigma interventions:

-

a ‘normalising’ strategies are inappropriate

-

b the principle of non-discrimination should be part of all mental health legislation

-

c fostering affection for the stigmatised group is often effective

-

d disseminating any information about mental illness is helpful, provided that it is accurate

-

e complaining to the media about adverse stereotypes is a waste of time.

-

-

5. The use of the following words and phrases should be avoided in vernacular situations:

-

a ‘utter madness’

-

b schizophrenic illness

-

c schizo

-

d ‘driving me nuts’

-

e psychosis.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | T | a | T | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | F |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | F | c | T |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | F | d | F |

| e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.