Political institutions significantly affect culture, with effects that can even outlast the duration of those institutions (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln Reference Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln2007; Bazzi, Fiszbein, and Gebresilasse Reference Bazzi, Fiszbein and Gebresilasse2020; Becker et al. Reference Becker2016; Tabellini Reference Tabellini2008). Democratic regimes, for example, tend to promote a specific democratic and civic culture (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019).

One component of this democratic culture is the norm that discourages ideologies, policies, and behaviours deemed at odds with democracy. Examples include norms against support for radical-right parties (Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Reference Harteveld and Ivarsflaten2018) and their policies (Bolin, Dahlberg, and Blombäck Reference Bolin, Dahlberg and Blombäck2022; Bursztyn, Egorov, and Fiorin Reference Bursztyn, Egorov and Fiorin2020), authoritarian successor parties (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2002; Valentim Reference Valentim2022), intolerance and racism (Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2018; Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2020), or the display of symbols with authoritarian connotations (Dinas, Martínez, and Valentim Reference Dinas, Martínez and Valentim2022; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2012).

These political norms – which we define as social norms that prescribe what political behaviours are deemed acceptable in a given social group in a given period – play an important role in promoting the quality of democracy. When they weaken, individuals and elites can feel more comfortable acting on racist (Alvarez-Benjumea Reference Alvarez-Benjumea2023; Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2020) or anti-democratic views (Dinas, Martínez, and Valentim Reference Dinas, Martínez and Valentim2022).

Building on work on norms in the fields of social psychology, sociology, and behavioural economics, we expect that political norms are enforced by observers who deem counternormative behaviour inappropriate. Because it is regarded as inappropriate, passers-by are more likely to engage in the social sanctioning of that behaviour than they are of behaviour that does follow political norms. Social punishment may come in the form of direct sanctions, such as physical and verbal confrontation, or indirect sanctions, such as gossip or avoidance of interaction. Both types significantly increase the costs of engaging in behaviour at odds with political norms vis-à-vis behaviour that aligns with them. These increased costs, in turn, incentivize society members to follow norms, making norm abidance rational and effectively keeping the norm in place.

We test this theoretical expectation empirically with a survey in Spain. Our survey asked respondents a number of questions about an individual who holds a given political preference, as portrayed by the political t-shirt they are wearing in the image we show respondents. We focus on support for radical-right parties, a political preference that a large number of studies have shown to be counternormative (Bursztyn, Egorov, and Fiorin Reference Bursztyn, Egorov and Fiorin2020; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Reference Harteveld and Ivarsflaten2018; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld2019; Valentim Reference Valentim2021). We thus turn our attention to respondents' views of the public display of support for the radical-right party, Vox. To provide a baseline, we also asked how they viewed the public expression of support for two other parties: a radical-left party (Podemos) and a mainstream party, the Spanish Socialist Worker's Party (PSOE).Footnote 1 The comparison with a radical party at the other end of the ideological spectrum (Podemos) should be particularly informative. It allows us to check whether there is a general norm against radical views or whether there is something specific to the radical right.

Our empirical analysis proceeds in five steps. First, we look into a necessary condition for our theoretical expectation: that individuals find the counternormative behaviour inappropriate. We show that respondents deem supporting the radical right as less socially appropriate, less morally appropriate, and more harmful than supporting the other parties. They also correctly perceive how others deem the display of such preferences – even if they slightly overestimate how inappropriate and harmful others deem expressions of support for the radical right.

Given that this precondition seems to be empirically supported, we move to the second step in our empirical analyses, where we assess whether individuals find it appropriate to sanction radical-right views. To that end, we compare how appropriate individuals deem sanctioning radical-right views to how appropriate they deem sanctioning other political views. We find that the more inappropriate individuals deem the display of radical-right views, the more appropriate they find sanctioning those views.

Afterwards, we assess what sanctions individuals view as more acceptable. These are indirect sanctions (that do not force interaction with the norm-breaching subject), such as gossiping and avoiding interaction. Again, individuals have correct expectations regarding which sanctions others deem most acceptable.

As a fourth step, we look into the self-reported willingness to engage in different sanctions. Individuals report that they would most likely engage in the types of sanctions they deem most appropriate: gossip and avoidance of interaction.

Finally, we look into the correlates of willingness to sanction. We find that age reduces willingness to apply sanctions, and that female and more educated respondents are less likely to engage in direct sanctions (but not indirect ones). Conversely, respondents living in areas with more Vox support are less likely to engage in indirect sanctions, but we find no significant correlation with direct ones. Emotional reactions (especially anger and disgust) also increase the likelihood of sanctioning. By contrast, we find no correlation between left-right ideology or political interest and willingness to engage in any type of sanction. All in all, our findings lend clear empirical support to our theoretical expectations.

Our paper speaks to three main strands of literature in political science and social sciences. First, our results speak to a growing literature on how democracies develop social norms against political behaviours that are regarded as undesirable (Ammassari Reference Ammassari2022; Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld2019; Valentim Reference Valentim2022). Despite its important insights, this literature had not yet theorized or empirically tested how those norms are enforced. In filling that gap, our paper paves the way for a better understanding of what maintains political norms in place, how they can erode, and their similarities to non-political norms.

Our results also speak to a literature that has come to highlight the socially constructed nature of political attitudes and behaviour (Bursztyn, Egorov, and Fiorin Reference Bursztyn, Egorov and Fiorin2020; Dinas, Martínez, and Valentim Reference Dinas, Martínez and Valentim2022; Funk Reference Funk2016; Valentim Reference Valentim2021). We highlight social sanctions as one likely mechanism by which individuals learn which preferences are acceptable or unacceptable. If individuals perceive that a given preference is sanctionable, they become less likely to act on it – at least when others are around (Kuran Reference Kuran1995).

Finally, our results speak to a literature on how the daily encounters one experiences can shape political attitudes and behaviour. This literature has shown that the attitudes of individuals can be affected by exposure to cues that they receive in their daily lives, such as signs of inequality (Sands Reference Sands2017; Sands and de Kadt Reference Sands and de Kadt2019) or individuals who are members of outgroups (Enos Reference Enos2014). We add to this literature by highlighting social sanctioning as one mechanism through which such encounters affect how individuals learn which preferences are and are not acceptable, likely conditioning their willingness to subsequently act on them.

Social Sanctions as a Mechanism of Enforcing Democratic Norms

Our goal is to build and test expectations as to the mechanism of enforcement of political norms. In the social science literature, norms are often regarded as unwritten rules of behaviour that govern one's behaviour based on expectations of what others do (empirical expectations) and what they deem acceptable (normative expectations) (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2017; Cialdini Reference Cialdini2003; Elster Reference Elster1989).

Following this literature, we define political norms as social norms that prescribe which political behaviours are deemed acceptable in a given social group in a given period. Our focus is on political norms that regulate behaviour in democratic settings, where one's political views are not usually subject to legal sanctions. This is an important scope condition of our argument. In non-democratic settings, the possibility of legal sanctions may outweigh social sanctions in predicting behaviour.

In democratic settings, we expect that political norms are enforced by observers who witness the norm-breaching behaviour and disapprove of it. Because they disapprove of it, they are more willing to impose social sanctions on someone expressing a counternormative political preference than on someone expressing a different one. By social sanctions, we refer to the costs imposed on individuals whose behaviour breaches established norms. That passers-by are more likely to impose sanctions on counternormative political preferences than on other political preferences makes the counternormative behaviour more costly than behaviour which follows the norm. This increased cost, in turn, makes norm abidance rational (Kuran Reference Kuran1995).Footnote 2

Three notes are warranted with regard to these theoretical expectations. First, sanctioning as a norm enforcement mechanism is compatible with only a low proportion of individuals willing to engage in sanctioning. Indeed, research on non-political norms found that only a minority of individuals are willing to sanction (Balafoutas and Nikiforakis Reference Balafoutas and Nikiforakis2012; Przepiorka and Diekmann Reference Przepiorka and Diekmann2013). The important point is that the number of those who do is significantly larger than those who would impose a sanction on behaviour that does not breach norms. What matters is the comparison of sanctioning across different types of behaviour (behaviour that does and does not breach established norms), not the comparison of the share of passers-by who are willing to sanction compared to the share of those that are not. So long as sanctions to counternormative behaviour are more likely than sanctions to other behaviours, counternormative behaviour will still be more costly, giving individuals an incentive to follow established norms. This holds true even if individuals self-select into social settings where they know others are less likely to sanction their political views. Sanctions will likely occur if they still need to interact with individuals outside those circles. It should be noted that the images we use in our survey depict precisely one such situation, where someone sees a stranger in a town square wearing a party t-shirt.

Second, it is more socially costly to express a counternormative preference irrespective of who does the sanctioning. For our expectations to hold, all that matters is that the expected social cost of expressing a counternormative preference is higher than the expected cost of expressing any other preference. We assume that the more individuals in a group are willing to sanction a given political preference on aggregate, the more socially costly it is to express that political preference. This expectation is in line with previous work on social sanctions to non-political norms (Balafoutas and Nikiforakis Reference Balafoutas and Nikiforakis2012; Balafoutas, Nikiforakis, and Rockenbach Reference Balafoutas, Nikiforakis and Rockenbach2014; Molho et al. Reference Molho2020). This research also looked into the overall amount of sanctioning behaviour as a measure of norm enforcement, treating observers who engage in the sanctioning as a monolithic group. As noted below, we ran analyses that check who was more likely to sanction radical-right preferences. We believe these analyses provide important insights into the norm enforcement mechanisms. However, our theoretical expectations are agnostic as to the nature of the observers who engage in sanctioning behaviour.

Finally, it should be noted that it is hard to separate the perceived appropriateness of holding a preference for a given party from the perceived appropriateness of publicly showing support. However, such a distinction is not crucial for the purposes of our paper. Individuals can hold preferences disapproved of by others, but the ability to sanction such preferences depends on their visibility. Individuals do not necessarily disapprove of privately supporting a party any less; however, with a lack of knowledge about these private preferences, they will be unable to impose a sanction. This variation in the likelihood of sanctions across private and public settings can give rise to a phenomenon known as preference falsification (Kuran Reference Kuran1987; Kuran Reference Kuran1995; Valentim Reference Valentim2022), where individuals conceal their sincere preferences to avoid social costs. However, our primary focus in this study is on demonstrating that the preference is generally deemed unacceptable – which means that, when publicly shown, it is potentially subject to sanctions.

We expect third parties to be willing to sanction deviations from political norms because, as a wealth of interdisciplinary research has shown, that is the case when it comes to non-political norms. Evidence for third-party sanctioning has been found in the lab (Fehr and Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter2000; Rabellino et al. Reference Rabellino2016) and in the field (Balafoutas and Nikiforakis Reference Balafoutas and Nikiforakis2012; Balafoutas, Nikiforakis, and Rockenbach Reference Balafoutas, Nikiforakis and Rockenbach2014), even if punishment comes at the cost of the individual's own payoff (Fehr and Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter2000; Henrich et al. Reference Henrich2006).Footnote 3

We argue that the same should happen with political norms, because a growing body of literature has shown that dynamics related to other political and non-political norms are similar. First, just as with non-political norms, the perception that there is a norm against or for a given political preference can affect individuals' willingness to engage in the associated political behaviour – such as support for the radical right (Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Reference Harteveld and Ivarsflaten2018; Valentim Reference Valentim2021), authoritarian successor parties (Valentim Reference Valentim2022), xenophobic behaviour (Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2020), and discourse (Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2018), or views on abortion (Jung and Tavits Reference Jung and Tavits2021).

Second, political norms are also similar to other norms when it comes to the mechanisms by which they change. Norm change mechanisms include the perception that a critical number of others share the counternormative preference (Andreoni, Nikiforakis, and Siegenthaler Reference Andreoni, Nikiforakis and Siegenthaler2021) or institutional cues signaling that the preference is more widely accepted than previously thought (Tankard and Paluck Reference Tankard and Paluck2016). Both mechanisms of norm change have also been shown to operate regarding political norms (Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2018; Bursztyn, Egorov, and Fiorin Reference Bursztyn, Egorov and Fiorin2020; Chauchard Reference Chauchard2014; Valentim Reference Valentim2021).

Following interdisciplinary work on social norms, we expect social sanctions on deviations from political norms to be of two types. Direct sanctions refer to overt punishment of norm deviations in the form of physical or verbal confrontation with the individual responsible for that deviation. Indirect sanctions refer to punishment that can be imposed in the absence of the offender. Examples include gossip or refusal to help the norm-breaching individual in future interactions (Molho et al. Reference Molho2020, 2).

Regardless of their type, third-party sanctioning is crucial to sustaining cooperation in societies (Fehr and Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter2002). Both increase the expected costs of engaging in counternormative behaviour – even if the specific medium imposed by that cost is slightly different. In direct sanctions, individuals pay a cost from the confrontation with the individual doing the sanctioning. In indirect sanctions, the cost can come in the form of losing opportunities for cooperation. This can happen immediately, when the individual doing the sanctioning refrains from helping the norm violator, or later on, in the form of a reputational cost from gossiping (Eriksson et al. Reference Eriksson2021; Schlaepfer Reference Schlaepfer2018).

While we expect third parties to be willing to engage in direct and indirect sanctions, we expect a greater willingness to engage in the latter than in the former. This is because they are less likely to elicit retaliation, and indirect sanctions are less risky for the third party imposing them (Casari and Guala Reference Casari and Guala2012; Molho et al. Reference Molho2020).

After discussing theoretical expectations about third-party sanctioning as a norm enforcement mechanism, we empirically assess whether observers are willing to impose sanctions on individuals who breach political norms. Our main objective is to test (1) whether third parties are willing to engage in sanctioning and (2) what types of sanctions they view as more appropriate.

As a secondary objective, we are also interested in exploring the individual-level correlates of willingness to sanction. As mentioned above, this objective does not directly relate to our core expectations, which are agnostic as to the nature of the observers willing to engage in sanctioning behaviour. That said, providing information on this issue deepens our understanding of the micro-level mechanisms of political norm enforcement.

We focus on a number of correlates that, based on previous literature, we might expect to predict willingness to sanction. Previous work in the social sciences has shown that when it comes to non-political norms, sanctioning behaviour depends on the third party's gender (Balafoutas and Nikiforakis Reference Balafoutas and Nikiforakis2012), ingroup status (Bernhard, Fischbacher, and Fehr Reference Bernhard, Fischbacher and Fehr2006; Goette, Huffman, and Meier Reference Goette, Huffman and Meier2006), education (Hoff, Kshetramade, and Fehr Reference Hoff, Kshetramade and Fehr2009), age (Winter and Zhang Reference Winter and Zhang2018, 2,724), and the emotions they experience upon witnessing the norm-breaching behaviour (Molho et al. Reference Molho2020). We thus look into whether these variables also predict the enforcement of political norms. To these variables, we add the strength of support for the radical right in the region. If that support is weaker, individuals are likely to perceive the norm as being stronger, which might make them more willing to sanction.

Apart from these predictors of enforcement of non-political norms, we add some political variables that might also help explain the enforcement of political norms specifically: political interest and ideology. Political interest has been shown to predict a wide range of political behaviours (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Van Deth Reference Van Deth, Jennings, Van Deth, Barnes, Fuchs, Heunks, Inglehart, Kaase, Klingemann and Thomassen1990). Examples include turnout, protest participation, and engagement in political discussions. For these reasons, we might expect interest to also correlate with willingness to sanction deviations from political norms – which is, ultimately, a political behaviour. Ideology has been shown to significantly affect how individuals interact with one another in daily life, including their dating decisions (Easton and Holbein Reference Easton and Holbein2021), the social networks they self-select into social networks of likeminded others (Brown and Enos Reference Brown and Enos2021; Kaplan, Spenkuch, and Sullivan Reference Kaplan, Spenkuch and Sullivan2022; Walker Reference Walker2013), and where they choose to live (Brown and Enos Reference Brown and Enos2021).

Case Study: Norms Against Radical-Right Behavior in Spain

The specific counternormative preference that we focus on is support for radical-right parties. This is one of the most widely studied political norms. Previous research has widely regarded such support as behaviour that breaches social norms and is significantly affected by their strength (Bursztyn, Egorov, and Fiorin Reference Bursztyn, Egorov and Fiorin2020; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Reference Harteveld and Ivarsflaten2018; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld2019; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Valentim Reference Valentim2021). Focusing on one of the most established political norms in previous literature is a good way to begin an inquiry into norm enforcement mechanisms.

Our focus is on Spain and the radical-right party in that country, Vox. This party is one of the latest examples of successful radical-right parties in Europe (Mendes and Dennison Reference Mendes and Dennison2021; Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama, and Santana Reference Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama and Santana2020). It was created in 2013 as a split from the centre-right Popular Party (PP). Vox's rhetoric is clearly norm-breaching. The party is strongly opposed to migration and often breaches norms against xenophobia and racism (Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter Reference Alvarez-Benjumea and Winter2018). It also mobilizes against the feminist tide in Spain after 2017 (Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2022) and opposes gender-egalitarian norms. Finally, the party has a positive view of the authoritarian past in Spain, another strong political norm in the country (Dinas, Martínez, and Valentim Reference Dinas, Martínez and Valentim2022).

In considering Vox as a stigmatized political party, we follow previous literature that has shown that this party family is counternormative in most Western contexts (Bursztyn, Egorov, and Fiorin Reference Bursztyn, Egorov and Fiorin2020; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten Reference Harteveld and Ivarsflaten2018; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld2019; Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Valentim Reference Valentim2021). For historical reasons, the party family is often associated with fascism and racism (Rydgren Reference Rydgren2005) in a way that the radical left, for example, is not. For this reason, previous research has often found that norm dynamics that apply to the radical right do not apply to the radical left (Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Valentim Reference Valentim2021).

At the same time, it should be noted that this stigma does not primarily stem from weak support for the party. This is what differentiates stigmatization from other dynamics that may affect small or marginal parties. We follow Valentim's definition of a stigmatized political platform as one against which there are established social norms (Valentim Reference Valentim2022). These social norms include a descriptive element (perceptions of what others do) as well as a normative element (perceptions of what others think should be done) (Bicchieri Reference Bicchieri2017). Other small party platforms may also be affected by the former, but it is unlikely they will be affected by the latter unless their rhetoric is norm-breaching per se. As such, they cannot be said to be stigmatized.

We chose Spain because it is a setting where the radical right has only recently become successful. Vox made its parliamentary debut in April 2019. In that election, it received 10.26 per cent of the vote, which increased to 15.08 per cent in the subsequent election in November 2019. As such, a case study of Spain provides a good balance between, on the one hand, a well-known radical right party and, on the other hand, a reasonably new party. While the stigma against radical-right parties does not stem mainly from their lack of electoral success, increased success can lead to the erosion of those norms (Valentim Reference Valentim2021). Running our study in a context where such a party is still relatively new means that these norms will likely not be completely eroded. Still, to the extent that the party is already in parliament, our results should be read as a lower band of willingness to sanction where the radical right is less electorally successful.

Survey Design

We surveyed the Spanish population to empirically test whether individuals are willing to sanction those who breach political norms. Our survey showed respondents a picture of an individual wearing a radical-right t-shirt. The picture depicts the individual in a public place (a square), sitting on a bench, and looking at their phone. It is a standard situation in which one might find many individuals as one goes about their daily life. Respondents were not told who the person wearing the t-shirt was or why he was there.Footnote 4 To ensure that individuals could identify the t-shirt the person was wearing, all respondents also saw a second image showing the t-shirt alone. The individual in the picture was a thirty-year-old male. We chose a male person to make the picture more realistic. As previous research has shown, supporters of Vox are overwhelmingly men (Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama, and Santana Reference Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama and Santana2020). Figures A1 through A3 in the Online Appendix show the images that were shown to respondents.Footnote 5

It should be noted that our design keeps constant a number of variables that previous research has shown to affect sanctioning behaviour, but which are not of interest for the purposes of our paper. We focus on third parties and their willingness to sanction their correlates. As such, we try to keep constant characteristics of the individual breaching the norm that can affect sanctioning, such as their gender (Balafoutas, Nikiforakis, and Rockenbach Reference Balafoutas, Nikiforakis and Rockenbach2014) or ethnicity (Winter and Zhang Reference Winter and Zhang2018). We also hold constant variables relating to the norm-breaching behaviour that might affect willingness to sanction, such as physical proximity to the individual breaching the norm (Di Stefano, King, and Verona Reference Di Stefano, King and Verona2015). While some of these variables may be hard to measure and control in a field experiment setting, our survey allows us to keep them constant.

Our analyses draw upon five sets of items included in the survey. Our main goal is to assess how the respondents rate the appropriateness of the display of radical-right preferences, how they emotionally respond to the picture, and how they perceive a number of sanctioning behaviours. In choosing which behaviours to focus on, we relied on previous research on social sanctioning. To be exhaustive and include all potential reactions of interest, we included types of sanctions used in different studies. First, we looked at four behaviours that are often coded in studies of social sanctioning outside the lab: physical and verbal confrontation, gossip, and social avoidance (Eriksson et al. Reference Eriksson2021; Molho et al. Reference Molho2020). To these, we add another common behaviour regarded as a form of direct punishment in previous work: insult (Brauer and Chekroun Reference Brauer and Chekroun2005; Rost, Stahel, and Frey Reference Rost, Stahel and Frey2016). Finally, we also add denial of help to the subject, a common type of indirect sanction in formal models and laboratory experiments (Nowak and Sigmund Reference Nowak and Sigmund2005; Ohtsuki and Iwasa Reference Ohtsuki and Iwasa2006). The specific sets of items we measure are:

• First-order norm perceptions: In the social norms literature, first-order expectations refer to an individual's own perceptions of the norm. To tap such perceptions, we asked the respondents how much they thought the public display of the radical-right t-shirt was socially appropriate, morally appropriate, or harmful. The first two items were asked on a 1–6 scale, while the third was asked on a 1–4 scale.

• Second-order perceptions: Second-order expectations refer to an individual's perceptions of others' perceptions of the norm. To measure them, we told respondents that we had asked the first-order questions to a sample of 1,000 respondents, and ask them to guess the modal response to each item in that group. Following common procedures in the norms’ literature, the questions were incentivized. Respondents were given an additional 35 points if they got the number right. These points could later be exchanged for money in the survey platform – similar to what happens in platforms like MTurk.

• Perceived appropriateness of sanctions: To understand which reactions to the norm-breaching behaviour were deemed most appropriate, we asked respondents how appropriate they thought it would be to react to the individual in the picture by engaging in direct sanctions (physical confrontation with the individual, verbal confrontation with them, and insulting them) and indirect sanctions (avoiding interaction with the individual, denying them help, gossiping about them), or by doing nothing. All these items were measured using a 6-point scale, ranging from completely inappropriate (1) to completely appropriate (6).Footnote 6

• Personal reactions: To tap respondents' own willingness to sanction the display of different political preferences, we asked them how they would react to the person in the picture. The types of reactions were the same as in the previous question. All questions were asked on a 0–10 scale where 0 meant ‘certainly yes’ and 10 meant ‘certainly no’. We subsequently inverted the scale, so that higher values mean more willingness to sanction.

• Emotional reactions: Finally, we asked the respondents to self-report whether they felt a number of emotions upon seeing the person in the picture. These questions were asked on a 5-point scale where 1 meant that the respondent completely disagreed that they felt that emotion, and 5 meant that they completely agreed that they felt that emotion upon seeing the person in the picture. We focus on a set of four negative emotions: anger, disgust, fear, and sadness.

Apart from these questions, we asked the respondents questions that tap into some covariates of interest: gender, year of birth, region of residence, education, political interest, left-right self-placement, and nationality.

As discussed above, our main focus is on the Spanish radical-right party, Vox. It should be noted that the party is legal, as is wearing t-shirts with its logo. If the party were illegal, the image would compound social and legal norms, and it would be hard to disentangle which of the two was driving the results. That Vox is legal ensures that any sanctioning behaviour will be driven purely by the perception that supporting it breaches social norms.

To provide a baseline comparison, we also asked respondents about their views on sanctioning the preferences for other political parties. First, we asked them the same set of questions after seeing the picture of the same individual wearing a t-shirt with the logo of a mainstream party: the PSOE. The PSOE is a centre-left party currently in government and has been in power most often during Spain's democratic period. We chose this party instead of the main right-wing party, PP, because the latter is an authoritarian successor party. This means that support for it breaches social norms against behaviour associated with authoritarianism (Valentim Reference Valentim2022). As such, if we were to add this party, that would not provide a baseline of willingness to sanction non-stigamtized parties.Footnote 7

One potential concern is that our results might be driven not by radical-right preferences being counternormative, but simply by the preference being more radical and less widely held. We add a second baseline comparison to address these concerns: the radical-left party, Podemos. Adding this additional party allows us to compare our results to how individuals react to a party that is also radical but whose views are not counter-normative, since radical-left parties breach social norms less (Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019).

Despite their opposite position in the left-right continuum, Podemos and Vox share a number of characteristics. First, they garnered similar vote shares in the latest election before our fieldwork (November 2019). Indeed, Podemos was the party with the closest vote share to Vox. Vox had 15.1 per cent of the vote, while Podemos had 12.9 per cent. This is an important point. It suggests that including Podemos in the survey allowed us to do away with the concern that the results may be driven by Vox being a smaller party than PSOE (our other point of comparison). If anything, the fact that Podemos had a weaker vote share will downward bias our estimates, by reducing the difference between the willingness to report sanctions to Podemos (less popular) and Vox (more popular). Second, both are relatively new parties. Vox was created in 2013, while Podemos emerged in 2014. Both parties gained popularity during a period when the long-standing bipartisanship that characterized Spanish politics came to an end. They positioned themselves as alternatives to the traditional political establishment and tapped into public dissatisfaction with mainstream parties. Third, as a consequence of this positioning, both Podemos and Vox have heavily criticized mainstream parties, which they accuse of corruption, elitism, and alleged neglect of the concerns of ordinary citizens. Finally, expert classifications have also indicated a number of similarities between them. For example, the PopuList project (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn2023) codes the two as populist and Eurosceptic parties. The project also codes both Podemos and Vox as parties at the end of the ideological continuum – the former at the far left, the latter at the far right.

To ensure that the survey was not too long, and to reduce the chances of demand effects, we showed each respondent only two of the three possible pictures (t-shirts with logos of the radical-right party Vox, the mainstream party PSOE, and the radical-left party Podemos). Since our main focus was on VOX, we oversampled the number of respondents who saw the individual with the t-shirt of that party. All respondents saw the picture of the individual wearing the VOX t-shirt and one of the two others. We randomly picked whether the additional picture each respondent saw displayed the individual wearing a Podemos or PSOE t-shirt. To do away with concerns about order effects, we randomized which picture the respondents saw first (Vox or a randomly picked party among the other two).

The survey was run online by the survey company Bilendi. Fieldwork took place between 13 June and 20 June 2022. The sample includes 1,182 individuals, with quotas for gender and age groups. Table A1 in the Online Appendix compares it to the sample in the 9th wave of the European Social Survey (ESS). Overall, our sample is similar to that of the ESS. However, the individuals in our sample were slightly more interested in politics, more likely to be from Madrid, and less likely to be from Castilla La Mancha.

Findings

How Appropriate is it to Show Radical-Right Preferences?

Before we focus on sanctions per se, we assess whether individuals deem expressions of some political preferences as more acceptable than others. Following our theoretical discussion, we expect that political norms are enforced by third parties who deem counternormative behaviour inappropriate and are willing to impose social sanctions on the individual engaging in that behaviour. Deeming the counternormative preference as inappropriate is a necessary condition for norm enforcement. With that in mind, our goal in this section is to check (1) whether individuals perceive that the expression of radical-right preferences is deemed undesirable and (2) whether they perceive that others around them also perceive it to be unacceptable.

To do so, we look into our survey items asking for the respondents' perceptions of how socially appropriate, morally appropriate, and harmful it is to display a given political preference (first-order expectations) and their perception of whether others deem the display of such preference as socially and morally appropriate and harmful (second-order expectations). The variables tapping harmfulness were inverted: higher values that displayed a given political preference were deemed less harmful. In all variables, lower values represent a stronger perception of a norm against a given preference.

The results are shown in Fig. 1. Each column represents one outcome. The first row represents first-order expectations; the second row represents second-order expectations. In each facet, we show the mean value for the radical-right party Vox and the remaining two parties.

Figure 1. First and second-order expectations of the appropriateness and harmfulness of showing radical-right preferences (VOX) and other political preferences.

Notes: Each dot represents a respondent. Vertical lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. Perceptions of harmfulness are measured on a 1–4 scale; perceptions of moral and social appropriateness are measured on a 1–6 scale.

The Figure shows that individuals deem the display of radical-right preferences as less socially appropriate, less morally appropriate, and more harmful than a preference for a party that is not radical right. When it comes to social appropriateness, expressing a preference for Vox is deemed 0.45 points less appropriate than for PSOE (p < 0.01) and 0.66 less than for Podemos (p < 0.01). When it comes to moral appropriateness, expressing a preference for Vox is deemed 0.55 points less appropriate than for PSOE (p < 0.01) and 0.68 less than for Podemos (p < 0.01). Finally, when it comes to harmfulness, expressing a preference for Vox is deemed 0.50 points more harmful than PSOE (p < 0.01) and 0.53 more harmful than Podemos (p < 0.01).

The Figure also shows that individuals have correct perceptions as to the views of others. The first and second-order plots look strikingly similar – especially when it comes to the difference between Vox and the remaining parties. It should be noted, however, that individuals seem to slightly underestimate how much others deem it appropriate to display all political preferences – not just the radical right ones. This could, however, be an artefact of the incentivization procedure. Since we provided incentives to find the modal answer, this may lead to an underestimation of the average.

We find similar values for the two non-radical right parties (PSOE and Podemos). This suggests that views of appropriateness regarding the radical right are driven by a specific anti-radical right norm, not by a norm against radical views in general. If that were the case, we would find the same results for the radical-left party, Podemos. The fact that we do not is in line with previous literature, which found that elements of norms against radical-right views do not replicate on the radical left (Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Valentim Reference Valentim2021).

In the Online Appendix, we provide some additional analyses. We start by replicating the comparisons shown in Fig. 1 as a within-subject regression. Because each respondent answered questions about two different parties, we can check whether these results hold when we add individual-level fixed effects. As shown in Table B1, the results support the same interpretation. Individuals perceive it to be more harmful and less socially and morally acceptable to show a preference for the radical-right party Vox than for any of the remaining parties.

We also provide a different comparison of perceptions of appropriateness and harmfulness. In Figures B2 through B4, we split the scales of the items analysed in Fig. 1 into agreement (bottom half of the response scale) and disagreement (upper half of the response scale).Footnote 8 We then compared the share of respondents who believed it was appropriate or harmful to display each preference to their expectations of others' views. The results again highlight that individuals tend to overestimate the share of others who deem the public display of all political preferences unacceptable. When it comes to PSOE and Podemos, more individuals think it is socially and morally appropriate to display that preference in public, but they believed that most others would deem it inappropriate. However, this pattern is not found when we look into perceptions of harmfulness. The respondents overwhelmingly find it not harmful to display these preferences in public, and their second-order expectations are accurate. Again, the results for these two parties are strikingly similar. As with Fig. 1, the situation changes when we look into the radical-right party, Vox. While the respondents still overestimated the proportion of others who deemed it morally and socially inappropriate to display this preference in public, most deemed it inappropriate, unlike what happened with the other two parties. The same is true of how harmful it is to display this preference in public. Unlike PSOE and Podemos, most respondents deem public expression of support for Vox as harmful.

Finally, Table B5 checks whether perceptions of acceptability depend on which image the respondents see first. We find no evidence in support of this hypothesis.

Is Sanctioning Radical-Right Views Deemed Appropriate?

Having established that individuals perceive the display of radical-right preferences as inappropriate, we move to the topic of sanctions per se. We start with testing whether, as we expect, individuals deem sanctioning radical-right behaviour as being appropriate. Based on research on non-political norms, we argue that what matters is not the sheer proportion of individuals who deem sanctions appropriate and willing to engage in them. What matters is that this share is higher than for behaviour that does not breach political norms.

We check for this expectation by comparing how appropriate respondents regard sanctioning radical-right preferences (a counternormative political preference) with how appropriate they regard sanctioning a preference for the other parties included in our survey (a political preference not counternormative). Our analyses leverage the fact that, in our survey, respondents were each asked a question about the two parties. As discussed above, all respondents answered the battery of questions for Vox and for one of the two other parties, randomly picked. This means that half of our sample answered the same questions for Vox and PSOE, while the other half answered the same questions for Vox and Podemos. This means we can estimate the difference in how appropriate the respondents deem sanctioning each political preference, adding individual fixed effects. This allows us to make within-individual comparisons, effectively controlling for all individual-level characteristics – both observable and unobservable.

To check whether respondents deem sanctioning radical-right views as more appropriate than sanctioning other political views, we reshaped the dataset to a long format, so that each row in our dataset depicts each respondent's perception of the appropriateness of each sanction, per party preference of the individual pictured in the survey. We then regressed the perceived appropriateness of each type of sanction on the party preference shown by the individual in the picture, adding individual fixed effects. We did this by adding to the model a dummy variable coded 1 if the individual in the picture was wearing a Vox t-shirt and 0 if he was wearing a t-shirt of a different party. If, as we expect, sanctioning the display of a preference for Vox is deemed more appropriate, we should find that the coefficient for this dummy is positive, suggesting that each sanction type is deemed more appropriate when imposed on an individual with a Vox t-shirt than on an individual with a t-shirt of a different party.

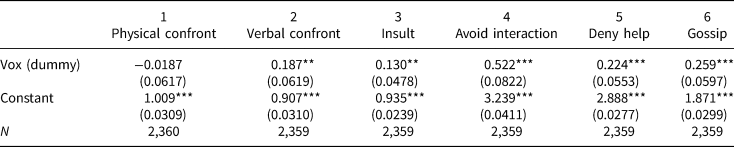

The results of this exercise are shown in Table 1. The columns in that table replicate the analyses using the perceived appropriateness of each of the sanctions our survey as the dependent variable. All variables were measured on a 1–6 scale.

Table 1. The respondents deem sanctioning radical-right preferences as more appropriate than sanctioning other political preferences

Standard errors in parentheses.

Notes: All models include individual fixed effects. All outcomes are measured on a 1–6 scale. Standard errors are clustered by respondent.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The table supports our expectations. For most sanctions, the dummy for Vox has a positive coefficient. This suggests that respondents perceive that punishing radical-right views is more appropriate than punishing other political preferences. The only exception is physical sanctions. There are three possible explanations for the lack of a difference in this outcome. First, respondents may deem physical confrontation inappropriate regardless of the party preference in the survey picture. Indeed, the mean appropriateness for this variable is quite low, at 1.78 on a 1–6 scale. That being said, it should be noted that other sanction variables have lower means – insult and denial of help, with means of 1.51 and 1.66, respectively – and we still find a difference in the models drawing upon them. Another possibility is that individuals do not see physical sanctions as appropriate because of concerns for their own safety. If this were the case, one should find that those respondents who feel fearful when seeing the person with a far-right t-shirt find physical sanctions less appropriate. This effect should be even stronger for respondents who belong to vulnerable groups, such as women, older respondents, and members of national minorities. We test for these hypotheses in Table B2 in the Online Appendix. We find no evidence that safety concerns drive the pattern. Fear does not predict the perceived appropriateness of physical sanctions, and there is no significant interaction between feeling fear and belonging to a vulnerable group. Finally, it may be that individuals deem physical sanctions counterproductive. Previous research found that claims involving violence were often regarded as inappropriate and generated backlash (Simpson, Willer, and Feinberg Reference Simpson, Willer and Feinberg2018; Wasow Reference Wasow2020). As such, respondents may feel that engaging in physical confrontation is likely to increase support for the radical right and their causes. Unfortunately, we have no way of empirically testing this interpretation. However, given that we find no empirical support for the alternative interpretations, we lean toward this one. Future research could provide more direct empirical evidence of this point, with studies specifically designed to test this hypothesis.

As an additional step, we check whether respondents who deem a radical-right preference least appropriate are also those who deem sanctioning as most appropriate. To that end, we regress the former variable on the latter. We control for several sociodemographic characteristics of respondents: their age, a dummy for respondents who attended college, a dummy for respondents who identify as female, a dummy for Spanish nationals, and fixed effects for each region of residence. As independent variable, we focus on the perceptions of social appropriateness of displaying a radical right preference. The Online Appendix replicates the same analyses using moral appropriateness and harmfulness measures. As shown in Tables B3 and B4, the results are similar.

The results are shown in Table 2. Each column shows the correlation between perceptions of social appropriateness of showing radical right preferences and the perceived appropriateness of each type of sanction.

Table 2. The more socially inappropriate the respondents think it is to show radical-right preferences, the more appropriate they think it is to sanction those preferences

Standard errors in parentheses.

Notes: All models include the following set of controls: age, a dummy for those respondents who attended college, a dummy for those respondents who identified as female, a dummy for Spanish nationals, and fixed effects for each region of residence. All outcomes are measured on a 1–6 scale. Standard errors are robust.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The results support our expectations. In all models, the coefficient for perceptions of social appropriateness is negative. This suggests that the more individuals deem it inappropriate to display a radical right preference, the more they deem sanctions appropriate. As with the previous analyses, the only coefficient that fails to reach statistical significance is the one for physical confrontation. As discussed above, this may be due to respondents feeling that physical confrontations may backlash.

Which Sanctions are Deemed Most Appropriate?

Thus far, we have shown that individuals deem the display of radical-right preferences as less appropriate than other political preferences. They deem sanctioning those preferences more appropriate, and the more they deem the display of those preferences inappropriate, the more they deem sanctioning them as appropriate.

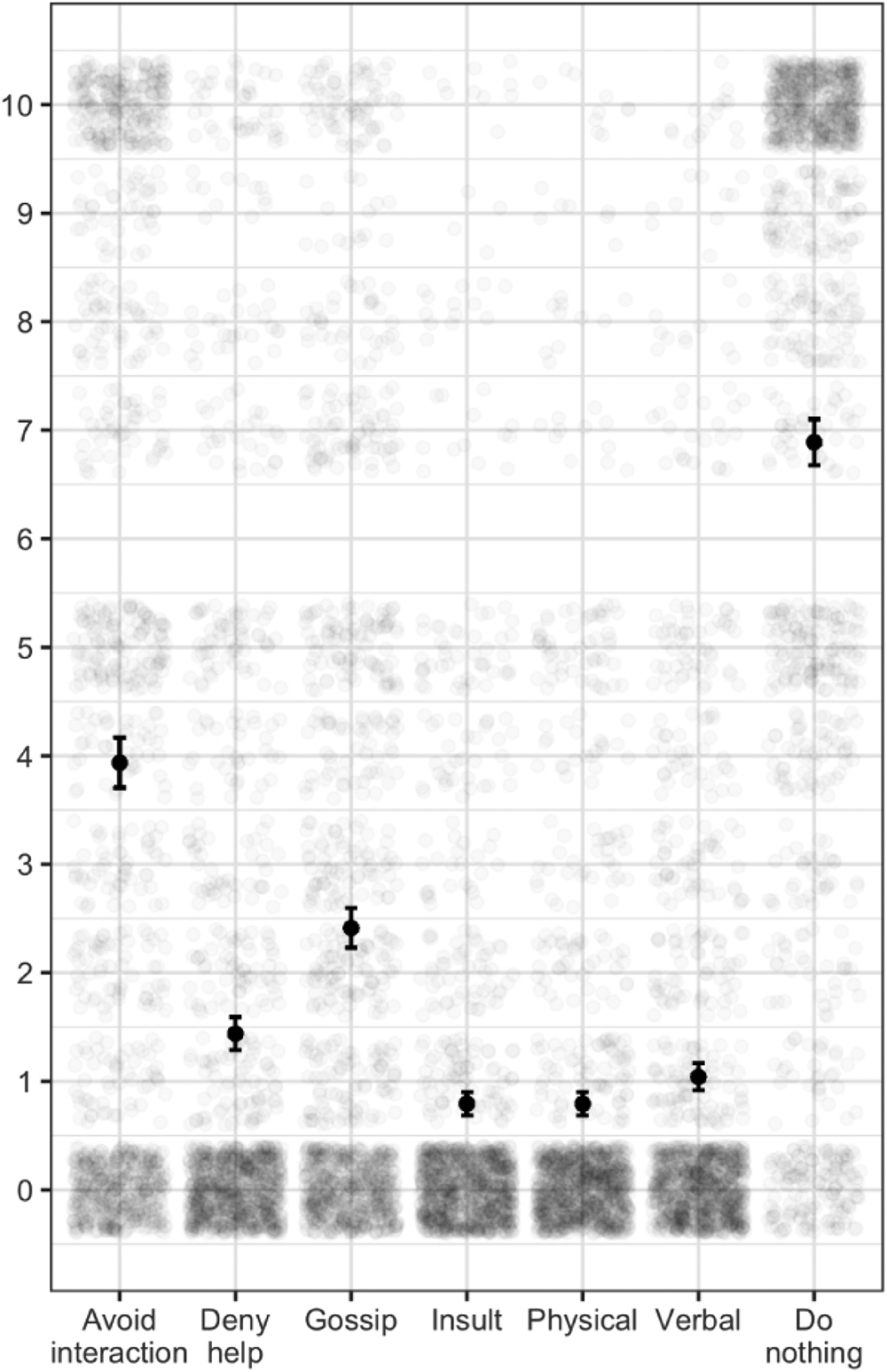

We now turn to the question of the specific types of sanctions perceived as most appropriate to punish the display of radical-right preferences. To answer this question, Fig. 2 looks into the perceived acceptability of different types of social sanctions. The first facet shows the distribution and the mean response to how appropriate the respondents perceive a given sanction to be. The second facet shows individuals' perceptions of how acceptable others would deem each type of sanction. We focus only on sanctions to radical-right preferences since that is the main interest of our paper. We replicate the analyses for the remaining two parties in the Online Appendix.

Figure 2. Perception of acceptability of different types of sanctions on individuals displaying radical-right preferences.

Notes: Each dot represents a respondent. All variables are measured on a 1–6 scale. Vertical lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The Figure shows significant heterogeneity in the perceived acceptability of sanctions to radical-right preferences. Two reactions are perceived as most appropriate: avoidance of interaction and gossip. Interestingly, both are indirect sanctions that involve no interaction with the subject. It should be noted, however, that the reaction perceived as most appropriate is not to react. This is in line with previous research, which has shown that not reacting is often perceived as the most appropriate reaction to a norm violation (Eriksson et al. Reference Eriksson2021), particularly in a situation where the punisher is a stranger (Eriksson, Andersson, and Strimling Reference Eriksson, Andersson and Strimling2017).

Comparing personal views to the perceptions of others also highlights interesting patterns. First, individuals accurately predict others' opinions with regards to the most appropriate sanctions. At the same time, it is interesting that individuals slightly overstate how appropriate others deem each type of sanction. This is in line with the findings shown in Fig. 1, which shows that individuals perceive that others will deem the display of radical right views as slightly less appropriate than they do. Given this slight mismatch in expectations, it makes sense that respondents also overestimate others' perceptions of the appropriateness of each sanction type.

The Online Appendix provides some additional analyses. First, Table B6 replicates the analyses shown in Fig. 2 in the form of a regression with respondent-level fixed effects. As noted above, this ensures that all individual-level variables (observable or unobservable) are kept constant. The results are similar to those shown in Fig. 2. Second, Figs B5 and B6 replicate Fig. 2 for PSOE (centre left) and Podemos (radical left), respectively, and Fig. B7 does so for all three parties together. We find that the patterns in which sanctions are deemed relatively more acceptable are similar to the ones for Vox. However, all sanctions are deemed less acceptable to individuals of these parties. This is in line with Fig. 1, which shows that support for Vox is deemed significantly less acceptable than support for the two remaining parties.

Which Sanctions Would Individuals Engage in?

We now turn to the items that tap into what individuals report they, themselves, would do. The results are shown in Fig. 3. As with Fig. 2, we report the distribution and mean response to how appropriate the respondents perceive a given sanction to be.

Figure 3. Self-reported reaction to the individual wearing the radical-right t-shirt.

Notes: Each dot represents a respondent. Vertical lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The Figure is strikingly similar to Fig. 2. Individuals report being more likely to engage in the same sanctions that they deem more appropriate – most notably, indirect sanctions such as avoidance of interaction and gossip. The fact that individuals prefer to engage in indirect sanctions aligns with previous work on non-political norms, which found the same pattern (Molho et al. Reference Molho2020). This pattern may be explained by fear of repercussions. Individuals may fear counter-sanctions if they directly sanction those with far-right views, which may explain why they prefer a type of sanction that can be done without the need for actual interaction.

In line with Fig. 3, the reaction that respondents report as most likely is not to engage in any sanctions. This is in line with the previous findings and research, which shows that, while individuals punish normative deviations, the proportion of those who sanction represents a minority. This is the case even for well-established social norms – such as queuing or littering (for example, Balafoutas and Nikiforakis Reference Balafoutas and Nikiforakis2012). However, even if only a small share of individuals are willing to impose social sanctions, this can still keep political norms in place by increasing the expected costs of behaviour at odds with those norms.

The Online Appendix reports some additional analyses to complement the findings of Fig. 3. First, Table B7 replicates these analyses in the form of a regression with individual fixed effects – where the results remain similar. This suggests that the differences in willingness to engage in each type of sanction found in Fig. 3 can be found even within respondents. Figures B8 and B9 replicate this in Fig. 3 for the two other parties included in our survey (PSOE and Podemos); Figure B10 does so for the three parties together. Again, we find that the relative propensity to engage in each type of sanction is similar to that in Fig. 3, but individuals report that they would be much less likely to sanction someone for showing a preference for PSOE or Podemos than Vox. This is an important point. Even if, as discussed above, individuals see non-reaction as the most appropriate and likely reaction to the expression of radical-right views, the willingness to sanction those views is much higher than that of sanctioning other political views. This means that expressing a radical-right view is significantly more costly than expressing a different political view, highlighting the role of third-party sanctioning as a mechanism of political norm enforcement. Finally, the types of sanctions that individuals are most willing to impose on radical-right views are those where the gap between willingness to sanction radical-right views and other political views is higher.

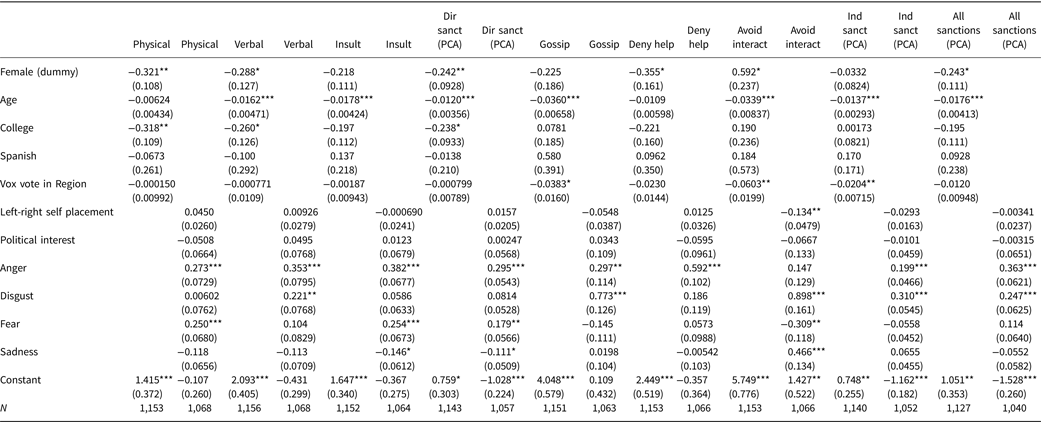

The Correlates of a Willingness to Sanction

A final question concerns the correlates of the self-reported likelihood of engaging in each type of sanction to radical-right preferences. As discussed in the theory section, our theoretical expectations are agnostic as to the nature of observers willing to sanction radical-right preferences. We simply predict that expressing a radical-right preference is more socially costly than a different political preference, regardless of who engages in the sanctioning behaviour. However, looking into who engages in the sanctioning behaviour provides important insights into the micro-level mechanisms by which political norms are enforced.

We look into three sets of potential correlates of sanctioning behaviour. First, we focus on sociodemographic characteristics of the third party: their age, gender, education (as proxied by a dummy for those respondents who attended college), and ingroup status (as proxied by a dummy for those respondents who are Spanish nationals). Along with these variables, we add the vote for Vox in the respondent's region in the previous legislative election. Second, we look into the respondent's emotions upon seeing the image of the individual wearing a radical-right t-shirt: anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and happiness. All these are measured on a 1–5 scale. Finally, we look into political attitudes: political interest (measured on a 1–4 scale) and ideology (measured as the respondent's self-reported left-right placement on a 1–10 scale). As discussed in the theory section, the choice of correlates builds on previous research on non-political norms (sociodemographics, local strength of the norm, and emotions) and predictors of political behaviour (political attitudes). Since attitudes and emotions are post-treatment to sociodemographics, we analyse the two sets of covariates in different models. We also include summary measures of direct, indirect, and all types of sanctions in the models, which we obtain by extracting the first component of a Principal Component Analysis. Doing so gives us an overall measure of willingness to engage in direct, indirect, or all sanctions, thereby reducing measurement error (Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2008).

The results are shown in Table 3. Each column represents a model where each of the outcomes (types of sanctions) are regressed on the two sets of predictors: sociodemographics, or attitudes and emotions. This means that we report two models per outcome. Standard errors (shown in parentheses) are heteroscedasticaly robust.

Table 3. Correlates of willingness to sanction radical-right views

Standard errors in parentheses.

Standard errors are robust.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

There are seven main takeaways from the analyses of the table. First, age is a clear correlate of intent to sanction. Older individuals are less willing to engage in both direct and indirect sanctions – with the only exception of physical sanctions, where we find no evidence of a correlation. The correlation between age and denial of help fails to reach statistical significance at the 95 per cent level but is close to that threshold (p = 0.068).

Second, gender also affects respondent's willingness to sanction, but the effect is more heterogeneous across different sanction types. Identifying as a female reduces, on average, the willingness to engage in all types of sanctions. However, this effect is clearer when it comes to direct rather than indirect sanctions. Identifying as female reduces the likelihood of engaging in all direct sanctions (even if the correlation with insult does not reach statistical significance). When it comes to indirect sanctions, the effect is less consistent. Respondents who self-identify as women are less likely to deny help, but they are more likely to avoid interacting with individuals who display radical-right preferences. Avoidance of interaction is the only sanction positively correlated with identifying as female, but that correlation is statistically significant.Footnote 9

Third, we find a similar pattern when it comes to education, which has the clearest effect in reducing direct sanctions. Individuals with a college degree are less willing to engage in physical and verbal sanctions, as well as in insults (even if the latter does not reach statistical significance). As happens with gender, the pattern is not as consistent when we look at indirect sanctions. When it comes to these sanctions, correlations are sometimes positive, others negative, and none reach statistical significance.

Fourth, we find no evidence that Spanish nationals are more or less likely to sanction radical-right preferences than respondents of other nationalities. No correlation with this variable is statistically significant, and their coefficients fluctuate between negative and positive. We use nationality as a proxy for ingroupism. Another way to measure ingroupism would be to focus on Spanish regions with strong peripheral nationalism, such as Catalonia or the Basque Country. With that in mind, we replicate these analyses in the Online Appendix, including a dummy for each region. As shown in Table B8, however, we find no evidence that individuals in either of these regions are more willing to sanction the display of radical-right preferences.

Fifth, respondents living in areas with more support for Vox are less likely to engage in indirect sanctions. We find a positive and significant correlation between aggregate-level support for Vox and the summary measure for indirect sanctions. All indirect sanctions negatively correlate with vote share for Vox in the respondent's region – although the correlation with denial of help fails to reach statistical significance (p = 0.113). Regarding direct sanctions, all correlations are still negative, but they are much smaller and far from statistically significant.

Sixth, in line with previous literature (Molho et al. Reference Molho2020), we find that individuals’ emotions correlate with their willingness to sanction. Anger is the clearest predictor, correlating positively with all types of sanctions. All these interactions are statistically significant, with the exception of avoidance of interaction. Disgust is also positively correlated with all types of sanctions, but many coefficients are smaller than anger: only those for verbal sanctions, gossip, and avoidance of interaction reach statistical significance. Fear increases the willingness to engage in direct sanctions but has a more ambiguous relation with indirect sanctions. Finally, we find some evidence that sadness reduces the willingness to engage in direct sanctions and increases the willingness to avoid interaction.

Seventh, we find little evidence that the willingness to engage in any sanctions correlated with political interest or left-right ideology. Political interest does not seem to correlate with any of the sanctions we look into. The coefficients are small, not statistically significant, and their direction does not follow any clear pattern.

The same is true of left-right self-placement, except that it negatively correlates with avoiding interaction. More leftist individuals are more likely to report they would avoid interacting with the individual with the Vox t-shirt. This finding should be read in light of the polarized political environment at the time the survey was fielded. Under high polarization, it is perhaps not surprising that ideology correlates with avoidance of interactions.

However, it is striking that left-right self-placement does not correlate with a willingness to engage in any other type of social sanction. The absence of a correlation between ideology and willingness to sanction could mask potential non-linearities of interest. In Table B9 of the Online Appendix, we address this possibility by including left-right ideology as a fully factorized variable (that is, by adding dummies for each position along the ideological continuum). The conclusion remains similar: there is little evidence of a relationship between one's ideological self-placement and willingness to sanction – except, perhaps, with the exception of avoidance of interaction. We also replicate these analyses using a dummy for left-wing individuals. As shown in Table B10, we again find little evidence of a correlation. If anything, there is a correlation between being left-wing and a willingness to engage in physical sanctions, but this contrasts with the remaining analyses, where we find no evidence of a correlation with this type of sanction. Finally, we replicate these analyses drawing upon the other two parties (PSOE and Podemos) rather than Vox. The results of these analyses can be found in Tables B11 and B12. We again find that ideology does not correlate with sanctioning behaviour – except for avoidance of interaction in the case of Podemos and denial of help in the case of PSOE.

The absence of clear evidence of a correlation between ideology and sanctioning behaviour suggests that willingness to sanction is not mainly motivated by political disagreement. It is not simply that individuals sanction those with different views from theirs; instead, it seems that there is a more shared understanding of what political views are deemed more and less acceptable, which drives the willingness to sanction.

These findings raise two additional questions. First, the extent to which willingness to sanction may be influenced by concerns for one's safety. Individuals of vulnerable groups, particularly, might be less likely to be sanctioned if they fear repercussions from a radical right individual. This could especially affect their willingness to engage in direct sanctions, which would explain why, in Fig. 3, we find more willingness to engage in indirect sanctions. In Table B13, we look into this possibility by checking whether fear affects the sanctioning behaviour of individuals who belong to a vulnerable group. We find only partial support for this expectation. The interaction coefficient is significant for many outcomes when it comes to members of national minorities, but not for women or older respondents.

Second, the findings raise the question of whether the willingness to sanction depends on the overall ideological outlook of a given society. Norms are influenced by perceptions of what those around oneself do. As such, norms against showing a radical-right preference could be weaker in societies with more right-wing support. They could even flip to make left-wing parties counternormative. Unfortunately, we cannot fully test this hypothesis since we do not have comparative data. That being said, in the Online Appendix, we delve into this question as much as possible with the data at hand. As shown in Tables B14 and B15, there is a somewhat weaker propensity to sanction radical-right preferences in regions where the right has stronger support vis-à-vis the left. This is especially the case for indirect sanctions. These correlations are less clear-cut when it comes to willingness to sanction radical-left preferences. As the right grows, the willingness to engage in direct sanctions on the radical left seems to decrease. We do find, however, some evidence that willingness to engage in indirect sanctions increases. As such, we find partial support for this hypothesis. However, it should be noted that our data makes it hard to draw clear-cut conclusions about this question. Doing so is beyond the scope of this paper and represents an avenue that future research could undertake. Moreover, while we find these marginal differences, it should be borne in mind that, as we show throughout the paper, the average willingness to sanction radical-right views is much stronger than that to sanction other views – including radical-left ones.

In the Online Appendix, we replicate the models using the attitudes and emotions reported in Table 3 after controlling for each respondent's willingness to sanction the other party preference they see in the survey – Podemos or PSOE. These additional analyses can be found in Table B16. We find that these correlate with willingness to sanction, suggesting that some individuals have a stronger intrinsic preference to engage in sanctioning behaviour. However, even after controlling for this variable, emotions predict sanctioning behaviour in ways similar to that shown in Table 3.

Conclusion

In most social settings, humans have expectations about which behaviours and views are or are not acceptable. Politics is no exception. As with other views, political views and behaviours are affected by an individual's perception of what is socially desirable.

We have focused on the micro-level mechanisms that keep these political norms in place. Bringing in insights from social psychology, sociology, and behavioural economics, we have argued that political norms should be enforced by third parties who disapprove of the norm-breaching behaviour and are willing to impose social sanctions on it. We have found support for our theoretical expectations by looking into norms against radical-right preferences – one of the most widely studied political norms – and drawing upon an original survey.

One of the main takeaways from our findings is that many of them align with the literature on micro-level dynamics of norms in other social realms. Examples include the role of emotions in predicting willingness to sanction and the fact that some individuals are willing to sanction, but they are a minority. Also in line with work on non-political norms, individuals prefer to engage in indirect sanctions that do not force an interaction with the individual breaching the norm, and are more likely to sanction in local contexts where the norm is stronger.

That political norms are in many ways similar to non-political norms contrasts with the fact that their enforcement does not correlate with typical predictors of political behaviour, such as ideology or political interest. These norms are inherently political, but there is nothing specifically political in the motivation to sanction deviations from them. While the enforcement of political norms lies at the intersection between the enforcement of social norms in general and political behaviour, our findings suggest that its motivations have more in common with the former than they do with the latter. Individuals perceive these norms and are willing to sanction deviations from them regardless of their political attitudes.

This bears some implications for how we understand previous findings on political norms. Existing research has shown that breaching political norms can lead individuals who agree most strongly with the norm to hold on to it even more deeply (Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Chua et al. Reference Chua2022; Valentim and Widmann Reference Valentim and Widmann2021). Our results suggest that these findings do not apply to sanctioning behaviour specifically, where there seems to be no ideological heterogeneity in willingness to sanction.Footnote 10

That ideology and interest do not correlate with sanctioning intentions also bears implications for our understanding of the scope of these norms. It suggests that political norms may be established at a broader societal level. In other words, it does not seem likely that different ideological pools of voters operate by different social norms – in which case, we would find that sanctioning intentions correlate with ideology. This point is reinforced by the fact that we do not find clear patterns when we look at correlations between one's region of residence and willingness to sanction (as shown in Table B8 in the Online Appendix). This finding is even more striking if we bear in mind that our survey was conducted in Spain at a moment of heightened affective polarization, which should make ideology-based sanctioning more likely.

To what extent are these findings likely to travel to different contexts? We believe that the findings are likely applicable to other advanced industrial democracies. The radical right is a party family with similar characteristics in different countries (Mudde Reference Mudde2007; Norris Reference Norris2005; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2005), as are the policiy positions that make these parties counternormative. Moreover, previous literature has assumed an overall stigma against this party family, regardless of their specific country (Ammassari Reference Ammassari2022; Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld2019). This suggests that enforcement mechanisms of these norms are likely to travel to other advanced industrial democracies.

However, previous research has shown that, in democracies that follow a left-wing authoritarian regime, the left may also suffer from stigma (Dinas and Northmore-Ball Reference Dinas and Northmore-Ball2020; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2002). While, as noted above, the radical right seems to be perceived as counternormative in most Western democracies, other parties may also be viewed as counternormative depending on context (Valentim Reference Valentim2022). We would expect our findings to extend to all such cases, regardless of the specific ideology of the counternormative party in question. That said, only replication can provide authoritative answers to this question.

Finally, another question related to external validity concerns whether individuals are willing to sanction radical-right preferences in the real world. Our survey evidence provides novel insights into who is willing to sanction, allowing us to look into a number of questions that would be challenging in a setting such as a field experiment. However, it also raises the question of whether and how these findings translate into the real world. To do away with this concern, we are currently working on a follow-up, expanding on the findings of this article with a field experiment in the vein of previous literature on social sanctions outside the political realm (Balafoutas and Nikiforakis Reference Balafoutas and Nikiforakis2012; Balafoutas, Nikiforakis, and Rockenbach Reference Balafoutas, Nikiforakis and Rockenbach2014).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000716.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/STXBCC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sofia Ammassari, Catherine Molho, and Eva Vriens for their helpful comments on the initial versions of the manuscript. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2023 Annual Conference on Experimental Sociology. We are also thankful for the participants' comments. We also thank the BJPS reviewers and editors for their helpful and constructive comments, which significantly improved the paper.

Financial support

This work has been supported by the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods in Bonn and by Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standards

IRB approval for this project was obtained from the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods.