Key statements

What is already known about the topic?

1. Patients emphasize different aspects of dignity in the last phase of life and these differences can be culturally shaped;

2. Palliative care providers generally find it difficult to identify and respond to the needs and wishes of patients from non-western migration backgrounds; and

3. A lack of insight exists in how physicians look at and respond to differences in perspectives on dignity and preserve dignity of patients in a (culturally) diverse population.

What this paper adds?

1. Physicians experience dilemmas in preserving personal dignity of patients from non-western backgrounds, as patients’ wishes can conflict with physicians’ other personal and professional values;

2. The standard response of physicians to make the dilemmas manageable is by ascertaining that the wish voiced is authentic; however, with migrants, this is often hampered by linguistic, cultural, and communication barriers;

3. Physicians have different strategies to find a way out of the dilemmas, some of which still conflict with important values of physicians and patients; and

4. The best but not the easiest way to find a way out of the dilemmas and preserve patient's dignity is to strive toward middle ground perspectives.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

1. Future physicians should be trained in connective strategies and seeking middle grounds to optimally preserve a patient's dignity while being in concordance with their personal and professional values.

2. Further research of the communicative process between physician, patients, and family is needed to understand the interactive nature of dignity-conserving palliative care and the effects of different strategies on preserving dignity.

Introduction

A specific group of patients in palliative care are older migrants. In the Netherlands, they make up 4% of the population aged 65 and over, but this is expected to increase to 18% (Central Bureau for Statistics, 2009). The largest groups are people from a Turkish, Moroccan, or Surinamese background (Central Bureau for Statistics, 2018). These older migrants may have specific needs, and Turkish and Moroccan migrants may follow Islamic principles in the palliative phase, as was shown in a study in the Netherlands (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2010). Many Turkish and Moroccan respondents stressed the importance of maximum, curative care till the end rather than quality of life. In addition, many preferred nondisclosure of information to the patient about their terminal illness to keep hope (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2010). Family members may make decisions for patients rather than patients themselves, partly because many Turkish and Moroccan older migrants do not speak Dutch and family members act as a translator (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2012a), but also because family members are important in care management and decision making (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2012b). Studies also have found that migrant patients in palliative care may refuse morphine and deep sedation because they want to have a clear mind when dying (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2010). Care providers generally find it difficult to identify and respond to the needs of patients from non-western backgrounds in the last phase of life (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Mistiaen and Devillé2012c; Schrank et al., Reference Schrank, Rumpold and Amering2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Jerzmanowska and Green2018).

The concept of “dignity” is helpful here to study the different ways that care providers can identify and respond to these needs of patients. “Dignity” refers both to values to protect the intrinsic worth of a person as well as to values responsive to the uniqueness of the patient that may be influenced by culture and religion (Jacobson, Reference Jacobson2007; Killmister, Reference Killmister2010; Barclay, Reference Barclay2016). Serious illness, related disabilities, and a nearing death threaten dignity in the last phase of life (Albers et al., Reference Albers, Pasman and Rurup2011; Van Gennip et al., Reference Van Gennip, Pasman and Oosterveld-Vlug2013), but care providers and family can strongly influence the patient's dignity (Guo and Jacelon, Reference Guo and Jacelon2014; Choo et al., Reference Choo, Tan-Ho and Dutta2020). However, care providers, patients, and family members emphasize all from their relevant personal or professional viewpoint, similar and also different values or aspects to preserve the patients’ dignity (Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman and Van Gennip2013; Choo et al., Reference Choo, Tan-Ho and Dutta2020). Additionally, migrant patients can emphasize different aspects for dignity than non-migrant patients (De Voogd et al., Reference De Voogd, Oosterveld-Vlug and Torensma2020). How the patients’ dignity can be preserved when confronted with differences between the persons involved, provides insight into strategies to meet wishes and needs of patients with a migration background in practice.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore how Dutch physicians perceive and try to preserve dignity in the last phase of life for patients from a non-western migration background.

Methods

Design

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews, which provided an in-depth exploration of physicians’ perceptions and experiences. We focused on patients with non-western backgrounds because research shows physicians can experience difficulties with providing palliative care to patients with non-western backgrounds (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Mistiaen and Devillé2012c; Schrank et al., Reference Schrank, Rumpold and Amering2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Jerzmanowska and Green2018), and end-of-life care and education being underpinned by principles and values of the mainstream western bioethical discourse (Johnstone and Kanitsaki, Reference Johnstone and Kanitsaki2009).

Participants and recruitment

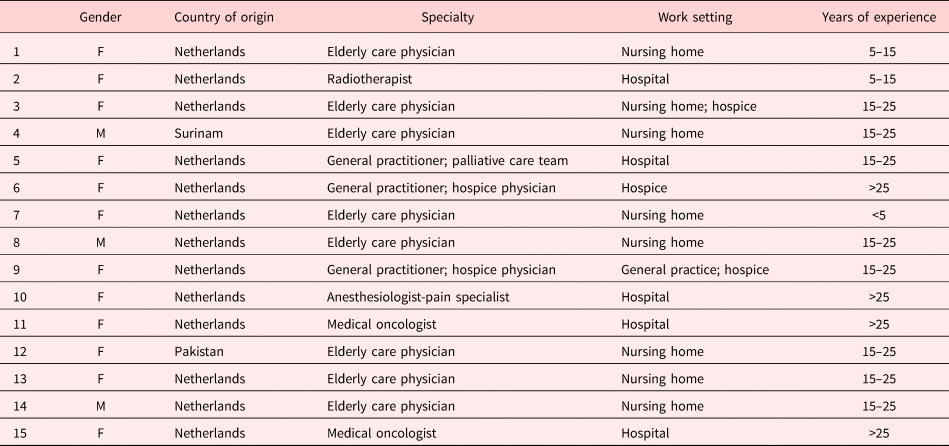

Participants were recruited through purposive and convenience sampling (Pope and Mays, Reference Pope and Mays2006). In total, 24 physicians were approached by email, of whom 15 participated. Participants were recruited through contacting our own network of general practices, nursing homes, hospices, and hospitals. In addition, physicians outside our network were approached because we expected them to be experienced in palliative care for migrants. One reason for nonparticipation was because physicians felt they had too little experience with the target population. For the others, the reason is unknown. We reached physicians with substantial experience in palliative care, including for people with non-western backgrounds, and diversity in years of experience, experience in palliative care, experience with palliative care for patients with non-western backgrounds, medical specialty, and ethnic background (Table 1). Twelve participants were female (80%), two participants had a non-western background themselves (13%), and the average years of experience across all participants was 15–25 years.

Table 1. Characteristics of the respondents

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between February and April 2019, by author AB. Being a medical student, this facilitated open conversation at an equal level. Although this was not known to participants in advance, the interviewer might have taken certain medical situations or arguments as self-evident without questioning them, for example, related to the choice of interventions and medical futility. Interviews lasted 30–60 min, taking place at the physicians’ workplace. A topic list was developed roughly based on the literature (Supplementary Appendix A). Topics included: physicians’ view on dignity, perceived differences in views with their patients from non-western backgrounds, physicians’ response to different views, and perceived role of communication differences.

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. We took a phenomenological approach to capture the physician's experience and perspective (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013). Data analysis was initiated after several interviews following an iterative process, allowing for improvement of the next interviews (Pope and Mays, Reference Pope and Mays2006). Thematic analysis was performed, by a combination of inductive and deductive methods, as the coding partly followed the topic list and literature on palliative care for non-western migrants, and partly open coding was performed (Pope and Mays, Reference Pope and Mays2006). Codes were ascribed to relevant text units and the code list that evolved was discussed and refined by the research group.

Two interviews were coded by author AB and XV independently, and iterative discussion of preliminary findings with all authors contributed to the quality of the analysis. The coding matrix was elaborately discussed among AB, XV, and JS and reviewed by all authors. Subsequently, we searched for patterns in the material, within and between interviews. This led to the identification of dilemmas and strategies, and their relation with communication barriers.

Ethical considerations

The medical ethics committee of Amsterdam UMC declared that this study did not require their approval, according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects, 2020). Every participant gave written informed consent prior to participation. All obtained data were anonymized.

Results

Central to almost all physicians’ view on dignity was that dignity is experienced and defined by the patient involved and is thus personal. Therefore, according to the physicians, preserving dignity in the palliative phase requires caring and decision making according to patients’ wishes. Several physicians mentioned the wishes and contentment of loved ones to be important for dignity in this phase as well. However, these perspectives on dignity conflict with other perspectives that physicians have on dignity, when providing palliative care for non-western migrants. This conflict between perspectives on dignity led to dilemmas, meaning that situations occurred in which different values competed. We will call these “dignity dilemmas”.

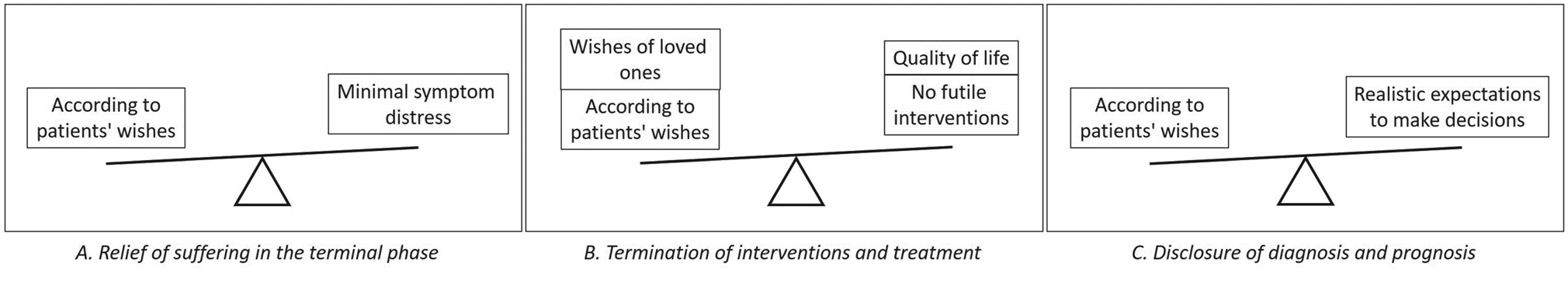

The dignity dilemmas arose when a wish was voiced or a choice was made by a patient or family member that conflicted with other aspects of dignity valued by the physician. These dilemmas were experienced in three situations: (a) relief of suffering in the terminal phase, (b) termination of interventions and treatment, and (c) disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis (Figure 1). These were the most prevalent reported dilemmas, but physicians also reported to not experience them with all patients with non-western backgrounds. Physicians with a non-western background linked the similarity between their view and other physicians’ views to their knowledge of and experience with palliative care. For example, they also felt that patients experiencing suffering incited a preference to not unnecessarily prolong suffering.

Fig. 1. Physicians’ dignity dilemmas.

Physicians related these dilemmas most often to Turkish and Moroccan patients, but some physicians described that similar situations can be encountered with people with other migration backgrounds or an ethnic Dutch background.

Dignity dilemmas

Relief of suffering in the terminal phase

This dignity dilemma was between the view that dignity is personal and the view on dignity that symptoms and suffering in the last phase of life need to be minimized. When it was a physician's recommendation to use opioids or initiate palliative sedation and the patient refused this, this led to a dilemma. The physician wanted suffering to be minimized by treating symptoms optimally:

“That man was very short of breath and if it would have been my father, I would have said please give him morphine, give him something to sleep, that he does no longer have to go through this, this last phase. And the morphine we had given in the end: he eventually wanted that. But well, we still saw suffering, at least in my eyes I saw suffering. I really thought ‘That man, he had to work really hard to die’.” [P01]

However, this conflicted with the physician's view on dignity being personal and the physician's wish for a last phase of life according to patient's wishes:

“we will always try to honour that as much as possible, if that is someone's intrinsic wish, to strive for a natural dying process, so the least interventions possible, we will always try to just meet those wishes.” [P13]

Termination of interventions and treatment

Another dignity dilemma was between physicians’ view that dignity is personal and physicians’ view that treatments that lack quality of life or are medically futile in the last phase of life need to be avoided. When a patient wished for treatments and interventions that, from the physicians’ perspective, were unlikely to bring significant benefits for the patient or that prolonged life and suffering “unnecessarily”, this led to a dilemma. For example, this physician described a situation with recurring hospitalizations, as well as tube feeding (in line with family's request) that was perceived as lacking quality of life:

“He just returned from the hospital and now he is going again, what quality of life does he still have, cannot eat by himself because he has a tube and he is wheelchair-dependent and the communication is difficult… What does he still have?” [P1]

However, this conflicted with the physician's wish to follow the patient's wishes in order to preserve personal dignity.

Disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis

A final dignity dilemma was between physicians’ view that dignity is personal and physicians’ view that patients need to be well-informed, in order to make decisions and shape end-of-life according to their autonomous wishes. When physicians wanted to inform patients about an infaust diagnosis and prognosis and patients did not want to know, or family did not want the patient to know all details, this led to a dilemma:

“I do think the base of our wish that someone is being informed [..], is that one can consider, this is the situation and how do I want us to handle that. [..] For example, if you don't know that you have cancer, are you able to properly decide whether to go on with palliative chemotherapy? And can you weigh the pros and cons, is this worthwhile for me, for I want to stay alive as long as possible, or I can't bear the side effects.” [P05]

Responding to the dilemmas, preserving dignity

Assessing patients’ authentic wish

When confronted with a dilemma, most physicians tried to ascertain that the wish of the patient was authentic and that the patient understood what a choice entailed and deliberately decided. When physicians were able to successfully identify the authentic wish, this did not always solve the dilemmas. However, the dilemma did become clearer, allowing the physicians to weigh the patient's wish, conform their view on dignity, against their other personal and professional values. Through conversation with the patient, the physician gained insight in patients’ personal values, motivations, and expectations, allowing physicians to optimally explore and assess the patient's authentic wish. When patients could not voice wishes themselves — which is common in this phase — these wishes were reconstructed together with family. Since these wishes are seen as central to personal dignity, they are preferably granted.

Physicians described that assessing authentic wishes of patients from non-western backgrounds could be difficult. Firstly, because patients’ wishes were regularly voiced or strongly influenced by different family members, also for patients who would be able to express their needs and wishes in their own language themselves. These differences in family involvement contributed to doubt on whether the family was articulating the patients authentic wish. Secondly, because patients or families regularly did not want to openly discuss end-of-life topics, impeding the discussion of patients’ wishes at an early stage. This would, in some cases, have created more time for, and involvement of the patient in this process, helping the physician in successfully assessing patients’ authentic wishes when this was still possible:

“And then it is really good if together [..] we can look, are we all kind of on the same line, because suppose that there will be a time that such a patient really is not able to tell himself, you can try to keep the patients’ wishes in mind and act accordingly. And then there shouldn't be discrepancies between what relatives think for example and what the professionals think, since that of course is a source of conflict, which is not a good thing in such situations.” [P09]

Additionally, when for whatever reason (e.g., preference for nondisclosure, language barrier, or mentally incompetent) wishes could not be discussed with the patient directly, it was difficult when the family was not inclined to openly discuss either.

Due to these difficulties, the authentic wish regularly remained unclear for physicians and they consequently turned to different strategies to find a way out of the dilemmas: accepting and going along with the wishes, convincing patients of their own view, and by seeking middle grounds.

Accepting and going along with wishes

The first strategy used to handle a dignity dilemma was to accept and go along with the (family's interpretation of) patient's wishes, despite the physician's other view on the situation. For example, in this fragment, the family of a patient in the terminal phase did not want opioids to be given and the physician went along with the wish:

“He was really in a lot of pain so I felt backed against the wall, because I wanted to do something against that pain and I was not allowed [..] Well a fair amount of analgesia can certainly make you drowsy, especially at first, so I explained: ‘well, if we only give a bit then maybe the drowsiness is not as bad’. But no, it was really not allowed. And then you respect that choice.” [P03]

Convincing of view and authoritative approaches

A second strategy that physicians used was to convince the patient or family of their view. This included giving explanations and information that intended to make patient and family understand the decision that needed to be made. Furthermore, physicians used their authority as a physician to influence decision making and used medical and legal arguments. For example, in this fragment, a patient with dementia received tube feeding but took the tube out. The family argued that the patient could not oversee the consequences of refusing tube feeding, whereas the physician felt the signal of the patient should be respected and used medical and legal arguments (referring to the Dutch Bopz-act about compulsion in healthcare):

“That obviously was the point of discussion between this grandson and me, that I thought we had to respect that, even though the patient could not completely oversee it. [..] And at that point I pulled rank here a little as a physician. But also the Bopz-act, I said I cannot force her to undergo this, I'm simply not allowed to.” [P07]

In the end, neither of the first two strategies were fully satisfactory because either values of the patient or of the physician were ignored. Some physicians described an alternative strategy.

Establishing connection and seeking middle grounds

An alternative strategy was to establish a connection and seek middle grounds.

Knowledge and understanding of the patients’ and families’ perspectives was used explicitly in the contact with patients to establish a connection and come to joint solutions. For example, this physician looked for acceptable alternatives with patients that did not want to use opioids for its sedative effects and proposed a middle ground:

“If you clarify that you understand why people are afraid of receiving morphine but you think you can address that by [..] for example giving a low dose.[..]. You can also explain morphine as something that relieves the pain and that pain as well is something that restrains you from appearing before Allah with a clear mind. [..] If you say I understand your fear that if we start morphine you might get drowsy and not appear for Allah adequately, but that pain might cause that as well. Could we address that for example with just a little bit [of morphine]?” [P05]

On the topic of disclosure, physicians described that they chose the right words to be sure that the patient is “sufficiently” aware of diagnosis and prognosis, meeting this aspect of physicians’ view on dignity. For example, a physician asked a patient whether he knew that he was quite ill and if he wished to know more about this, or preferred to not know. By avoiding words such as “cancer” and “dying”, the dignity dilemma was dealt with by seeking middle ground and was acceptable to patient and family. Furthermore, by asking the patient to what extent he wished to be informed, the physician also found middle ground when family preferred nondisclosure toward the patient and decision making as a family.

Additionally, some physicians underlined the process of truth telling, for example, saying the right thing at the right moment, and the experience of dignity, by giving continuous explanations and sketching scenarios, and initially going along with wishes for treatments of patient and family, so patient and family could experience that dignity was safeguarded, and family was reassured that physicians tried everything they could.

Some physicians also described spiritual counselors and religious leaders can establish mutual understanding and act as mediators between physicians and patients/families to come to the “best possible” solution for all, for example, by informing all those involved about the content and interpretation of the Koran.

Discussion

Main findings

Physicians experienced dilemmas in preserving dignity of non-western patients in three situations: (a) relief of suffering in the terminal phase, (b) termination of interventions and treatment, and (c) disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis. Physicians wanted to grant the needs of patients in the last phase of their lives, which was central to physicians’ view on dignity, but dilemmas arose when this conflicted with physicians’ other personal and professional values. To make the dilemmas manageable, physicians assessed whether needs of patients were authentic in an open conversation, but due to linguistic, cultural, and communication barriers, this was difficult with non-western patients. To find a way out of the dilemmas, physicians had three strategies: accept patient's wishes, convince or overrule the patient or family, or to seek middle grounds. Middle ground is created by seeking connection and understanding of the patient's and family's view, by communicating in a way that the patient is aware of his/her situation without complete disclosure and by asking to what extent he/she wants to know more about his/her situation. In this way, the values of the patient, family, as well as the physician are combined into middle ground perspectives for keeping hope, an authentic last phase of life (with or without complete disclosure), and dealing with pain. This strategy could be more valuable to preserve dignity than the separate perspectives of the patient, family, or physician.

What this study adds

Physicians’ central view that dignity is personal is in line with the conceptualization of dignity in the literature (Albers et al., Reference Albers, Pasman and Rurup2011; Leget, Reference Leget2013; Hemati et al., Reference Hemati, Ashouri and Allahbakhshian2016). Physicians intend to provide care in line with patients’ wishes to provide dignity-conserving care (Oosterveld-Vlug et al., Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman and Van Gennip2013; Choo et al., Reference Choo, Tan-Ho and Dutta2020). Our study showed that in practice, this leads to dilemmas when physicians’ other personal or professional views on dignity diverge from those of migrant patients or their family. Giving dignified care therefore appears to be not just about dignity being personal. While the dilemmas may not be exclusive for patients with non-western migrant backgrounds, our findings resonate with earlier studies that also report difficulties with truth telling and a focus on care by family and religious values for dignity in the last phase (De Graaff et al., Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2010, Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2012a, Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2012b, Reference De Graaff, Mistiaen and Devillé2012c; Schrank et al., Reference Schrank, Rumpold and Amering2016; Green et al., Reference Green, Jerzmanowska and Green2018; De Voogd et al., Reference De Voogd, Oosterveld-Vlug and Torensma2020). The main difficulties and, perhaps, differences physicians experience with palliative care for these patients reside in to what extent physicians are able to employ strategies to manage the dilemmas. Our study showed that physicians tried to make dilemmas related to dignity manageable by ascertaining that the wish voiced is authentic, in order to preserve the patient's dignity. This authentic wish was explored by gaining insight in patients’ personal values, motivations, and expectations. An authentic choice ideally encompasses comprehension of what a choice entails and is one that is deliberately made. Rather than openly discussing this authentic wish, physicians may need to explore this differently than they are used to if the patient or family does not want to talk about diagnosis or prognosis and may have to accept that this authentic wish is shaped in concordance with family or by family. De Graaff et al. (Reference De Graaff, Francke and van den Muijsenbergh2012a) also showed the high involvement of Moroccan and Turkish family members in decision making and physicians’ difficulties to deal with this. Our study showed ways in which physicians handle both different views and values to preserve the patient's dignity, as well as different preferences for how to discuss the last phase of life and make shared decisions with the patient and family.

Implications for practice

As physicians’ attitudes and approaches have the potential to influence patients’ perceptions of dignity (Pringle et al., Reference Pringle, Johnston and Buchanan2015), we believe that training of (future) physicians needs to include dignity preserving approaches for non-western migrants. Training can help (future) physicians to reflect on situations in which different perspectives on dignity conflict (Bovero et al., Reference Bovero, Tosi and Botto2019). Training can focus on knowledge about dignity, awareness of the dignity dilemmas, and skills to engage in communication with patients and their families (Bovero et al., Reference Bovero, Tosi and Botto2019). Strengthening physicians in connective strategies and seeking middle ground is of particular importance to optimally preserve the patient's dignity. Employing the other strategies risks losing valuable perspectives on dignity. Dismissing the physician's perspective denies that providing additional information, gaining trust, and addressing family's fears can change perspectives on what dignity entails in practice in an appreciated manner. However, patients and families may still hold additional sets of values and views, such as religious or familial ones (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Chan and Leung2013; Li et al., Reference Li, Richardson and Speck2014; De Voogd et al., Reference De Voogd, Oosterveld-Vlug and Torensma2020) that are important for dignity regardless the physician's view, and dismissing these views will also be harmful. Training can focus on motivational interviewing, eliciting patient and family perspectives as equally relevant perspectives and shared decision making, familiarization with perspectives on dignity and their origin, using interpretation services, and seeking support from religious counselors and cultural mediators. While these training elements are not new, they are rarely being trained in a palliative care context.

Furthermore, we found that physicians’ view on dignity is multi-layered; there is not one crucial element that is important to them. Moreover, their view is constructed in a communicative process between physician, patients, and family. Thus, conceptualizing dignity as patients’ perception on personal dignity vs. physicians’ views on dignity as a more static model (Chochinov et al., Reference Chochinov, Hack and McClement2002; Van Gennip et al., Reference Van Gennip, Pasman and Oosterveld-Vlug2013) does not yet capture the interactive nature of dignity-conserving palliative care.

Limitations

We may have mainly recruited physicians motivated to improve palliative care for migrants and therefore possibly missed other physicians’ dilemmas. Also, the construction “non-western” captures not perfectly physicians’ experiences since they seemed to interpret this as being “culturally or religiously different” from themselves, nor does the construction captures complexities of diverse patient populations. It may be that the dilemmas found were specific for Islamic patients; however, cultural differences between physician and patient also seem to play a role in many other countries (Shabnam et al., Reference Shabnam, Timm and Nielsen2020). Since we only included two physicians with a non-Dutch background, further research could explore how their views on dignity and strategies are formed and related to their own education or personal characteristics. Finally, we only studied physicians’ perceptions on communication, rather than the communication itself. We recommend new studies in which patient–physician–family communication is studied, to gain more insight in the construction of dignity and to provide physicians with more insight into how their communicative strategies may or may not be effective in dealing with the dilemmas and preserving dignity.

Conclusion

This study showed that the view that dignity is personal leads to dilemmas for physicians providing palliative care for people with non-western backgrounds, when their other personal or professional views on dignity diverge from those of migrant patients or their family. Physicians that care for people with non-western backgrounds in the palliative phase need to be trained in recognizing the dilemmas and in supportive strategies to preserve patients’ dignity.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895152100050X.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study and analyzed and interpreted data. AB collected data and drafted the manuscript. XV, AM, and JS contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not- for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was examined by the medical ethics committee of the Amsterdam University Medical Centres, location AMC. The committee declared (reference number W19_109 # 19.142) that this study did not require their formal assessment, according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (CCMO, 2019).

Data sharing

To ensure anonymity of the study participants and their patients, we are not able to share the data with other researchers.