INTRODUCTION

The study of war is now a firmly entrenched aspect of Maya archaeology. Advancements in epigraphic decipherment have worked in conjunction with the analysis of fortifications, war-related iconography, settlement patterning, site destruction episodes, and bioarchaeological evidence to continually refine our understanding of the role war played in past Maya societies (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Brown and Stanton2003; Inomata Reference Inomata2008; Martin Reference Martin2020; O'Mansky and Demarest Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Chacon and Mendoza2007; Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986; Webster Reference Webster2000). While there are volumes on the geopolitical, systemic, evolutionary, and structural consequences of social conflict, less attention has been paid to the particulars of Maya martial practice. As a result, social actors and their embodied experiences have been largely overlooked, leaving issues of agency in Maya warfare underdeveloped. To account for this imbalance, we advocate for redoubled focus upon tactics, strategy, fortifications, materiel, captivity, embodiment, and the myriad other practical elements implicated in the process of making war among Maya peoples. Such an approach serves to address a simple, yet crucial, question: how did Maya peoples practice war?

In this article, we are not trying to create a universally applicable definition of war. In a similar vein, we do not address the related theme of violence, though a discussion of this issue can be found in the article by Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Hernandez, Bracken and Seligson2023) within this Special Section. Defining war and violence is akin to outlining a definition of culture. Our more modest goal is to take widely accepted aspects of war-making and examine them in the Maya cultural context. Accordingly, we seek to examine the phenomenon of armed combat between social groups, and the processes entailed in preparing for and administering the outcomes of a martial engagement or campaign. The articles in this Special Section expand on the above themes by applying comparative, regional, and experiential perspectives.

Military historians specializing in Old World cultures have been more apt to analyze the particulars of war as listed above, while the works that do exist on the details of martial practice in the Americas tend to address the era of European colonization and beyond (e.g., Jones Reference Jones1998; Keener Reference Keener1999; Malone Reference Malone1991; McNab Reference McNab2010; Restall Reference Restall1998; Restall and Asselbergs Reference Restall and Laurence Asselbergs2007). This void in the literature could, in many cases, be attributed to an absence of written records that describe martial practice. However, in every conceivable sense of the word “history,” most of Maya archaeology is historical archaeology. A rich archaeological and iconographic record dating back to the Early Classic can be paired with a deciphered script to provide investigators with the opportunity to propel forward the still-burgeoning field of Maya military history. In working toward this common goal, the authors in this Special Section build on a call to take warfare seriously by thinking about what this unit of analysis means in practice (Inomata Reference Inomata, Scherer and Verano2014; Inomata and Triadan Reference Inomata, Triadan, Nielsen and Walker2009; Nielsen and Walker Reference Nielsen and Walker2009).

Practice is what people, as embodied social beings, do in particular cultural and historical contexts (Barrett Reference Barrett and Hodder2012; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977; de Certeau Reference de Certeau and Rendall1984; Dobres Reference Dobres2000; Dobres and Robb Reference Dobres and Robb2000; Giddens Reference Giddens1984; Ingold and Vergunst Reference Ingold and Vergunst2008; Inomata and Triadan Reference Inomata, Triadan, Nielsen and Walker2009; Joyce Reference Joyce2005; Nielsen and Walker Reference Nielsen and Walker2009; Ortner Reference Ortner1984; Reference Ortner2006; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1981, Reference Sahlins1985). Human activity, which encompasses thought and action, is an emergent process. In other words, the dynamics of practice are contingent upon the unfolding interactions of people with places, things, non-human forms of life, and a host of other contextual factors. Practice furthermore exists in a coconstitutive relationship with culture and any other generative schemes of the human experience. A practice approach requires attending to the particulars of human activity and the context in which they are constituted, bringing into focus what people do. In this Special Section, we examine Maya culture through time by situating martial activity as the starting point of our analysis, illustrating how the process of making war can have widespread ramifications for society.

Cross-cultural research has demonstrated that war impacts and weaves into social life far beyond the time and place of a martial engagement. A fortified settlement, such as many medieval European castles, can host peaceful, quotidian life for generations, channeling daily movement by the populace according to martial considerations that residents may never see in action or be consciously aware of (Johnson Reference Johnson2002). Many social roles can be defined in conjunction with a warrior identity, a position that can range from a full-time specialist to anyone mustered to fight in a time of crisis. Factors such as class, gender, age, ability, sexuality, and kinship can intersect to influence a person's relationship to the process of making war. For example, gender, age, ability, and status have been crucial factors in determining who is a suitable soldier, commander, and legitimate target in nineteenth- and twentieth-century United States wars (Brown Reference Brown2012; Goldstein Reference Goldstein2003; Lynn Reference Lynn2003; Serlin Reference Serlin2003). Individual motives for participation in the martial process, whether for personal gain, belief in a cause, or sheer survival, carry huge implications for the outcomes of war and broader society (Keegan Reference Keegan1976). After all, the accomplishment of broad strategic goals, such as hegemonic control over neighboring polities, is dependent upon the individual motivations and agency of the combatants who will carry out tactical and operational designs. Although often elusive in Maya studies, we hope to open the door for these types of analyses by starting a conversation on the issue of martial practice.

Unpacking the particulars of Maya warfare benefits from a deeper engagement with military history. Scholars in this field of study provide a rich body of concepts, terminology, theory, and a focus on historical specifics that can help guide future research. The eminent scholar of war, John Keegan (Reference Keegan1976), provides an entry point for the study of practice through his focus on the “Face of Battle.” Highlighting how top-down approaches dominated military history, he promoted a new mode of inquiry that emphasized bottom-up and experiential approaches to war. Beyond the level of grand strategy, or the machinations of state actors and generals, what can be learned about the everyday warrior and their experience of war-making? Building on Keegan's approach, many of the authors in this Special Section examine how elites and non-elites would have experienced, participated in, and been impacted by the process of making war. Scholars of military history likewise can benefit from anthropological approaches to practice and culture. As Giddens (Reference Giddens1979, Reference Giddens1985), Ortner (Reference Ortner2006), Sahlins (Reference Sahlins1981, Reference Sahlins1985), and Sewell (Reference Sewell2005) highlight, theories of practice are also conceptualizations of history. By examining, over time, the emergent processes that result from human activity with the world, we are also unpacking the historical process and providing insight into how cultures form, persist, and change.

Despite wide acknowledgement of human agency and experiential approaches as vital aspects of archaeological analysis, in this introductory article we demonstrate how the issue of war tends to remain in a conceptual “black box” (Clarke Reference Clarke2015:58–62; Latour Reference Latour1987; cf. Nielsen and Walker Reference Nielsen and Walker2009). In other words, warfare is treated as an entity of change or crucial variable in the analytical process, but its internal complexities are largely under-examined. Like the computer, war is widely invoked as a mechanism to address complex problems. Investigators rarely peer inside the box, however, to understand the intricacies of how the mechanism actually operates. Instead, the application of the black box is focused on outcomes or what effects it produces for any set of input circumstances (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The black box model. A set of known inputs is mediated via a blackboxed entity, such as a computer. This mediator in turns provides a set of outputs.

In this introductory article we tease apart the analytical category of war by focusing on the specifics of Maya and Mesoamerican martial practice through time. We demonstrate how warfare has been blackboxed, by examining the theme of raiding across several decades of Maya studies. With the issue of blackboxing established, we turn to comparative data on martial practice and social organization. By examining the details of war-making in ancient Macedonia and the Zulu kingdom, our goal is to demonstrate how a focus on the details of practice provide key insights on the process of state formation and disintegration. These examples allow us to address theoretical debates on Mesoamerican states. Last, we provide a brief overview of how the articles of this Special Section chart a course for study into the practice of war among Maya peoples.

THE ELUSIVENESS OF MARTIAL PRACTICE

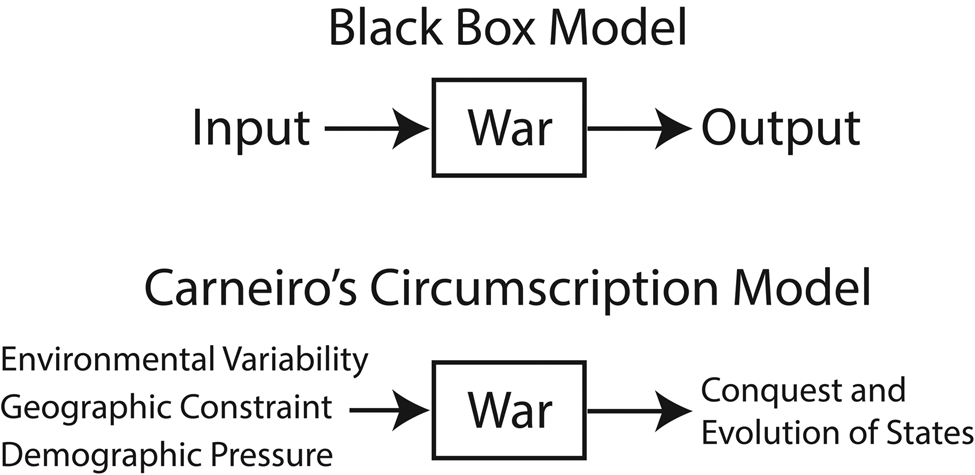

It seems probable that research on Maya warfare will maintain a vigorous pace for years to come, as attested by the wealth of volumes and articles published on the subject just in the last three years (e.g., Alcover Firpi and Golden Reference Alcover Firpi, Golden, Hutson and Ardren2020; Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Stanton and Kathryn Brown2020; Garrison and Houston Reference Garrison and Houston2019; Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019; Helmke Reference Helmke2020; Martin Reference Martin2020; Morton and Peuramaki-Brown Reference Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020; Recinos et al. Reference Recinos, Firpi and Rodas2021; Serafin Reference Serafin, Fagan, Fibiger, Hudson and Trundle2020; Wahl et al. Reference Wahl, Anderson, Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine2019; Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Helmke, Gibbs, Micheletti, Stanchly and Powis2019). In many publications, however war is treated as a free-floating, reified, abstract category devoid of context or human agency (Nielsen and Walker Reference Nielsen and Walker2009). This framing overlooks the messiness of lived experience, such as temporality, contingency, and causal heterogeneity. In this way, war is blackboxed (Figure 2) or becomes a receiver of inputs and producer of outputs whose internal dynamics are largely overlooked and as a result, under-conceptualized (Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel1992:553; Latour Reference Latour1987, Reference Latour1999). This under-conceptualization leads to potentially meaningful social variations being smoothed over to facilitate the production of results (Clarke Reference Clarke2015:58–62). By peering into the black box, we endeavor to pull forth otherwise overlooked factors that impact the martial process. Such factors can include the tactical and societal implications of fortifying landscapes or creating martial imagery.

Figure 2. The black box model (top) and Carneiro's (Reference Carneiro1970) circumscription model (bottom). In Carneiro's circumscription model, inputs, such as farming and geographical circumscription, are claimed to result in warfare that leads to conquest and state formation. War is blackboxed because he does not investigate nor indicate which types of martial practice would have led to the growth of political communities. This results in the intricacies and innerworkings of warfare being obscured in favor of the analysis of causal factors leading to war (inputs) and the effects (outputs) of warfare on state formation.

While the phrase “black box” could conjure an image of Maya martial practice as unknowable and mysterious, perhaps out of reach of comprehension, the opposite is true. We argue that deeper engagement with martial practice, and its significance for society beyond the scope of combat or an engagement, serves to unpack how and not just why particular social processes unfolded (e.g., Pauketat Reference Pauketat2001). In this formulation, peering into the black box means probing the specifics of war-making more closely. For example, in Carneiro's (Reference Carneiro1970) circumscription model, he argues that states grow out of militarily expansive polities. Success in war is therefore a crucial factor (“mechanism”) in the process of state formation. Yet, war itself remains blackboxed because he neither investigates nor indicates which types of martial practice would have led to the growth of political communities. Small-scale skirmishes are lumped together with grand military campaigns, and the potential interrelation of these aspects with other explanatory factors, such as logistics, specialization, and martial culture, remain obscured.

To further illustrate how war has been blackboxed, we build from Helmke (Reference Helmke2020:20) who argues the terms “raid” and “raiding” remain ambiguous in their application by scholars of the Maya. This uncertainty is part of a wider lack of conceptual clarity in the anthropology of war. His claims are sobering because discussions of raiding, more than any other tactic, have been at the core of scholarship on Maya warfare. In support of Helmke's argument, we provide a brief history of research on raiding through works authored primarily by Anglophone scholars.

Raiding in Maya Archaeology

In the early to mid-twentieth century, a group of scholars including Thompson and Sylvanus Morley developed the peaceful, theocratic paradigm for Classic Maya civilization. In so doing, they had to account for the apparent transition to a more warlike society by the time of the Spanish encounter in the 1500s, as well as instances of Classic-period martial imagery such as the Murals of Bonampak. Their general response was that the arrival of Terminal Classic foreigners corrupted the Classic Maya in a process referred to as “Mexicanization.” According to this line of argumentation, potential earlier evidence of war merely represented limited, small-scale raiding for ritual purposes. As Thompson (Reference Thompson1954:52) states,

“I think one can assume fairly constant friction over boundaries sometimes leading to a little fighting, and occasional raids on outlying parts of a neighboring city state to assure a constant supply of sacrificial victims, but I think the evidence is against the assumption of regular warfare on a considerable scale.”

Like conceptions of ritual warfare in other parts of the world (Turney-High Reference Turney-High1949; cf. Arkush and Stanish Reference Arkush and Stanish2005), raiding supposedly had no major impact on Classic Maya society.

As the peaceful Maya paradigm crumbled in the ensuing decades due to mounting evidence to the contrary (Miller Reference Miller1986; Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986; Webster Reference Webster1976), an emphasis on raiding persisted. In some ways, raiding served to account for new evidence while maintaining that Maya martial practice still fell short of large-scale, open battles. One of the major arguments centered on what Webster (Reference Webster, Sabloff and Henderson1993) satirically labeled the “Killer King Complex.” Based primarily on hieroglyphic and iconographic evidence, some scholars argued that Classic Maya warfare was predominantly an elite matter focused on the capture and sacrifice of high-status rivals (Freidel, et al. Reference Freidel, Schele and Parker1993; Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986). This process of war-making legitimized divine rulers by fulfilling their role in maintaining the order of the cosmos.

Freidel (Reference Freidel1986) pursued the elite warfare model by examining the role of raiding in interactions between peer polities or autonomous, geographically close political communities. Building from Webster (Reference Webster1976), he defines raiding as “brief battle aimed at surprise attack and quick defeat rather than at total conquest and subjugation” (Freidel Reference Freidel1986:94). With this definition, Freidel (Reference Freidel1986) argues that during the Classic period a pan-Maya, elite political charter controlled the scope and extent of warfare. Because elite captive sacrifice was central to the legitimacy and reproduction of the polity, the capture of high-status victims was purportedly the primary motivation for war. Confined to raiding for this purpose, war had little to do with non-elites, and the limitations on martial practice created a protracted period of peer-polity interaction. Thus, war-making has structural implications but retains elements of ritual warfare. Freidel's analysis, however, leaves the particulars of raiding generally unattended. How did Maya warriors achieve stealth and speed? Moreover, why would quick, surprise attacks not be useful in achieving conquest? Clausewitz (Reference Clausewitz, Howard and Paret1976 [1832]:115–116, 527) highlights that due to the negative impacts of time on attackers, such as fatigue, loss of supplies, and potential for mishap in the crisis of battle, quick victories are preferable over protracted engagements. Although Freidel's analysis does not explore tactics in depth, in a few years Hassig would provide a more detailed examination of raiding.

Hassig (Reference Hassig1992) examines raids as surprise hit-and-run attacks that are generally limited in scale and impact. Raiding, in his analysis, does not result in conquest or territorial acquisition. Instead, it is a tactic akin to guerilla warfare that relies on speed and stealth. He also argues that wars of conquest take place between conventional forces: large, well-trained masses of warriors who confront similarly organized opponents (Hassig Reference Hassig1992:16, 28, 32, 120, 149). Paralleling the challenges of asymmetrical warfare encountered by the United States military in Iraq and Afghanistan, Hassig argues differences in tactics between conventional forces and raiders led to difficulties for Mesoamerican imperial forces (e.g., Buffaloe Reference Buffaloe2006; Thornton Reference Thornton2007). Conventional forces stand and fight. A lumbering mass of warriors, however, loses many of its advantages against a more flexible force of raiders who refuse to stand in place and avoid showing themselves.

Based on the state-of-art research of his time, Hassig (Reference Hassig1992) relies primarily on artistic representations of Mesoamerican warfare, an approach that he admits provides a skewed view of past societies. As a result, his claims about Classic Maya warfare are like those of Freidel. For Hassig, war was predominantly an elite prerogative, with Maya nobles engaging in raids to strike rival communities, take captives, and attain political legitimacy. Comparable to his assessment of the Early Classic, Hassig (Reference Hassig1992:95) argues that “[w]ith small, primarily elite, armies, raiding remained the dominant mode of warfare in the Late Classic, a situation reflected in Maya artistic representations of named, individual, noble warriors.” He adds that political legitimacy and demonstrations of power via martial force were a means for rulers to secure hinterlands, dependent populations, and economic benefit. The Maya aristocratic form of warfare, however, “discouraged large conventional armies and set-piece battles, fostering instead smaller armies, [and] greater emphasis on mobility” (Hassig Reference Hassig1992:103). The practice of limited warfare included a uniform martial culture that fostered a general stalemate. He further argued that limited logistical capabilities halted Maya imperial expansion, which allowed for effective control of only nearby hinterlands. Thus, a uniform martial culture of limited warfare or elite raiding plus poor logistical abilities were purportedly the reasons Classic Maya peoples formed city-states, and why no single polity was able to build an empire like the Mexica. Altogether, his interpretations of Classic Maya warfare are firmly entrenched in the Killer King Complex.

Hassig's work still provides an example of how detailed investigation of the practicalities and limiting factors associated with different tactics and strategies can lay the groundwork for understanding martial practice. While the nature of his investigation remains relevant, a vast amount of new information has emerged in the past three decades. In addition to the artistic representations mentioned above, the core of his aristocratic model of war depends on little involvement by non-elites, along with a dispersed lowland Maya settlement pattern showing limited evidence of fortifications and mass destruction (Hassig Reference Hassig1992:71, 75–79, 94–98). A few years after the publication of Hassig's book, investigators in the Petexbatun region of Guatemala provided widespread evidence of fortifications and demonstrated that the Terminal Classic collapse in this part of the Maya world was tied to large-scale warfare (Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, O'Mansky, Wolley, Van Tuerenhout, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo1997). Scherer and Golden (Reference Scherer and Golden2009) subsequently documented an extensive network of regional fortifications forming a boundary zone between Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan (see also Golden and Scherer Reference Golden and Scherer2013; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Scherer, Rene Muñoz and Vasquez2008). More recently, light detection and ranging research is substantiating claims that Maya fortifications are more extensive than previously documented (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Estrada-Belli, Garrison, Houston, Acuña, Kováč, Marken, Nondédéo, Auld-Thomas and Castanet2018; Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019). Investigators have also provided compelling evidence for an instance of “total war” aimed at Witzna during the Early Classic (Wahl et al. Reference Wahl, Anderson, Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine2019). Although the question of non-elite participation in war remains open for debate, much of the Killer King Complex is no longer tenable. Maya warfare had ritual elements, and it was deadly serious with potential ramifications for people across the social spectrum (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Hernandez, Bracken and Seligson2023).

With the Killer King Complex dethroned as an overarching explanation, it remains necessary to reconsider the practice of raiding among Maya peoples. In Webster's (Reference Webster2000) most recent overview of Maya warfare, he dedicates more space to raiding than any other tactic. Although highly critical of Killer King models, Webster builds from a series of his publications in the 1970s and 1990s to argue raids played a role in status rivalry between elites. Like Hassig, Webster (Reference Webster, Feinman and Marcus1998, Reference Webster2000) considers raiding as quick, surprise attacks by a comparatively small number of warriors. He also acknowledges this tactic could include “ambushes, feints, false retreats, and other stratagems to confuse and disorganize the enemy” (Webster Reference Webster, Feinman and Marcus1998:324). Yet, it seems that after the works of Hassig (Reference Hassig1992) and Webster (Reference Webster, Sabloff and Henderson1993, Reference Webster, Feinman and Marcus1998, Reference Webster2000), much of the discussion on how the Maya raided has halted.

In more recent works, a focus on the details of Maya martial practice is often replaced with a general notion of tactics or, as Helmke (Reference Helmke2020) argues, with ambiguous terminology (e.g., see Carleton et al. Reference Carleton, Campbell and Collard2017; Garrison et al. Reference Garrison, Houston and Firpi2019; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Serafin, Masson, Lope, Guzmán and Russell2017; Sabloff Reference Sabloff2019). O'Mansky and Demarest (Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Chacon and Mendoza2007) revisit the issue of status rivalry but place significantly less emphasis on tactics. They argue, “knowledge of the specifics of Maya warfare—weapons, tactics, the size of armies, and so on—is largely speculative” (O'Mansky and Demarest Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Chacon and Mendoza2007:20). They do mention raiding, however, as small-scale attacks that could result in the acquisition of captives and enhance prestige. They also contend, “the dispersed settlement pattern of Maya centers would have made surprise raiding extremely difficult” (O'Mansky and Demarest Reference O'Mansky, Demarest, Chacon and Mendoza2007:20). Their claim about martial practice is intriguing and deserves further unpacking. Without surprise, how could Maya peoples engage in raids? Are they implying that raids can be small-scale, perhaps rapid attacks that may or may not involve surprise? If so, dispersed settlement might deter raids when the targets are elites shielded by a wide hinterland of loyal commoners. This buffer zone could have mitigated the element of surprise by allowing for warnings to be raised and reinforcements to be called (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kusimba and Keeley2015; Leblanc Reference LeBlanc, Arkush and Allen2006). If the targets could be any member of the opposing population, however, then the Classic-period pattern of dispersed, low-density settlement (e.g., Smith et al. Reference Smith, Ortman, Lobo, Ebert, Thompson, Prufer, Stuardo and Rosenswig2021) could provide a wealth of opportunities for raiders. These contrasting interpretations highlight the utility of pairing studies of martial practice with settlement patterns to understand past social life.

Alcover Firpi and Golden (Reference Alcover Firpi, Golden, Hutson and Ardren2020) provide a potential avenue for resolving some of the ambiguity associated with settlement patterns by tying together documentary evidence with data on the scale and form of past fortified landscapes. Ethnohistoric data attest to the prevalence of raiding in the Colonial era, suggesting this tactic was also prevalent during the preceding Postclassic period. They also note the prevalence of small, isolated, hilltop Postclassic settlements in the Guatemalan highlands with controlled access and good visibility. Bringing together the fortification and ethnohistoric data, they argue that “dispersed competitors established, or adapted, defensive sites to protect against raids and increase visibility of and control movement across the immediate landscape” (Alcover Firpi and Golden Reference Alcover Firpi, Golden, Hutson and Ardren2020:488). They also argue many small Preclassic fortified settlements “closely resemble Postclassic fortified sites of the Highlands and suggest similar internecine warfare that gave way to the larger scale conflicts mounted by more powerful, centralized states during the Classic period” (Alcover Firpi and Golden Reference Alcover Firpi, Golden, Hutson and Ardren2020:488). Their claims highlight the likely possibility that overall frequencies of raiding fluctuated over time.

Given its limited conceptualization but widespread use in models of Maya social life, raiding has been blackboxed. We agree with Helmke (Reference Helmke2020) that further investigation into the process of raiding is crucial for understanding the impact war had on the lives of Maya peoples. Hassig highlights that success in raiding requires a different skillset from set-piece battles, foregrounding stealth and quickness as opposed to pageantry and the steady advance of massed units. It is also possible the aggressors and targets of raids were comprised of elite and non-elite. After all, the commemoration of elite male warriors on monuments and murals does not preclude women, children, the elderly, slaves, and other groups from having participated and making significant contributions in the martial process (e.g., Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel1992). Digging into the details of practice is a step toward revealing the diversity of actors involved in war-making and allows researchers to build more robust conceptual frameworks for understanding the past.

THE PRACTICE OF WAR AND POLITY EXPANSION IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

To demonstrate how a practice-based approach reformulates the way researchers address questions on warfare, we examine two case studies of polity expansion from the military history of ancient Macedonia and the Zulu kingdom. We subsequently tie the insights from both cases into predatory/warfare models of Mesoamerican state formation. The Macedonian and Zulu case studies provide apt comparative data for our analysis because they are filled with examples of how the particulars of martial practice are tied to and have profoundly shaped polity expansion and social organization (Gilliver Reference Gilliver2002b; Keegan Reference Keegan1993; Knight Reference Knight1995; Lynn Reference Lynn2003; Shaw Reference Shaw1991). Our analysis reveals how a series of relatively quick (i.e., within a generation or two) changes in materiel, tactics, and warrior culture can tie into and even trigger fundamental shifts in broader social organization, which provide key points for discussion of Mesoamerican state formation.

Ancient Macedon

One of the most well-known figures of ancient history is Alexander the Great, who by the age of 32 had conquered the Persian Empire (Figure 3; Fox Reference Fox2004). The success of his army was made possible by the reforms credited to his father, Philip II. Prior to the start of Philip's reign in 359 b.c., the kingdom of Macedon was not a major force in the Greek world (Worthington Reference Worthington2014:4–5). The previous ruler had been killed a year earlier as the result of a disastrous military defeat at the hands of Bardylis, a rival polity, which subsequently occupied the northern part of Macedonia (Anson Reference Anson2013:43–44; Psôma Reference Psôma and Fox2011:124–125). Philip had also spent three years as a hostage in Illyria and Thebes. Within a year of becoming king, Philip defeated the armed forces of Bardylis, and by the end of his reign had subjugated most of the Greek city-states, setting the stage for the empire under his son Alexander. What led to such an abrupt change in the history of Macedon?

Figure 3. Map of Alexander the Great's empire ca. 323 b.c. Modified by Bracken from Wikipedia (2009), used under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Philip is credited with ushering in reforms of Macedonian armament, tactics, and various other factors of warrior culture that played major roles in the expansion of his kingdom (Anglim et al. Reference Anglim, Rice, Jestice, Rusch and Serrati2002; Fox Reference Fox and Fox2011; Worthington Reference Worthington2014). Although the exact timing of the changes in martial practice is under debate, it is clear that the Macedonian forces under Philip achieved a decisive martial edge over rival polities. One of the most crucial changes in the Macedonian arsenal was the implementation of the sarissa, which was a thrusting spear longer than the traditional hoplite spear (Figure 4). The length (~4.5–7.5 meters) of the sarissa meant that two hands were required to wield it effectively, and as a result Macedonian warriors carried a smaller shield than their Greek counterparts (Hammond Reference Hammond1980; Markle Reference Markle1977, Reference Markle1978). When assembled in the phalanx formation (rows of spear-wielding infantry in close order), the extra length of the spear allowed more of the rear lines in the phalanx (up to five) to extend their spear point beyond their own front rank (Markle Reference Markle1977). Thus, opposing shock forces, including rival Greek phalanxes, would confront a mass of Macedonian spearheads before being close enough to inflict deadly blows with their own weapons. Use of the sarissa was part of a wider tactical emphasis on combined forces.

Figure 4. Traditional Greek hoplite (left) versus Macedonian hoplite (right). Image of Traditional Greek hoplite is redrawn from May et al. (Reference May, Stadler, Votaw and Griess1995) and the Macedonian hoplite is redrawn by Hernandez from an illustration by Gregory Proch (Guttman Reference Guttman2013).

The Macedonian army relied on a hammer and anvil technique to achieve victory (Anson Reference Anson2010b). The anvil was composed of infantry and light cavalry with the sarissa-wielding phalanx at the core of the fighting force. As opposing forces crashed into the infantry, the cavalry would form the hammer by attempting to achieve the decisive action in battle through attacks on the sides and exploitation of gaps in the rival formation. Contrary to the classical armies of Sparta and Athens, the Macedonian forces placed greater emphasis on cavalry to achieve victory on the battlefield (e.g., Sekunda Reference Sekunda, Roisman and Worthington2010; Worthington Reference Worthington2014).

The use and effectiveness of the sarissa, hammer and anvil tactic, and related developments by the Macedonians were complemented by the professionalization of the army under Philip (e.g., Müller Reference Müller, Roisman and Worthington2010; Sekunda Reference Sekunda, Roisman and Worthington2010; Worthington Reference Worthington2014). He is credited with instituting year-round drill and regular pay, including land given upon the successful completion of military service. The distribution of land enhanced the loyalty of the army to Philip. As a result of the changes in training and pay, a shift occurred from an army composed primarily of part-time conscript warriors to one of full-time martial specialists who trained year-round. Extensive training had the benefit of fostering unit discipline in the phalanx formation (Carney Reference Carney1996). Moving as a cohesive martial unit, while essentially shoulder-to-shoulder, requires drill, and if opponents could penetrate the wall of spears, the phalanx could be defeated. Thus, professionalization served to improve the strength of the sarissa-wielding phalanx and allowed for the successful implementation of the hammer and anvil tactic by Philip's, and later Alexander's, forces.

The Zulu State

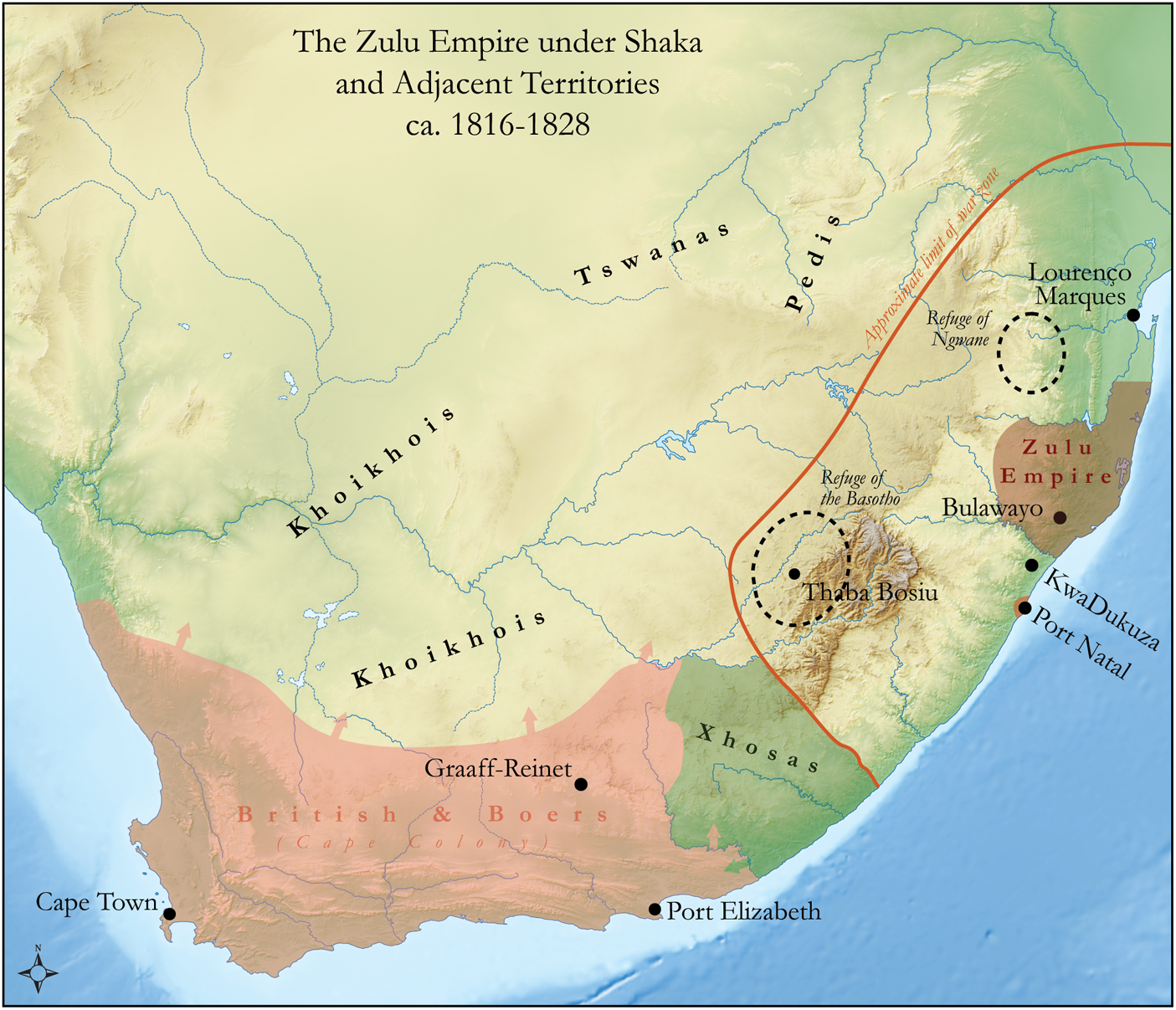

Martial reforms also played a critical role in the formation of the Zulu state under the rule of Shaka in the early 1800s (Chanaiwa Reference Chanaiwa1980; Deflem Reference Deflem1999; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2012; Flannery Reference Flannery1999). In a landscape of competing polities, he was able to lead the Zulu to martial success and exert control over neighboring territories (Figure 5). Like the Macedonians under Philip, the Zulu martial advantage was tied to changes in armament, tactics, and other facets of warrior culture (Knight Reference Knight1995; Morris Reference Morris1965; Sidebottom Reference Sidebottom2004). When Shaka came to power, his forces transitioned to the use of a short, stabbing spear designed for use in hand-to-hand combat. Previously, Zulu battles were often engagements of warriors on opposing sides hurling spears at each other (Knight Reference Knight1995:109). Shaka's forces would close rapidly in tight formation to fight in hand-to-hand combat. Once they were close enough, Zulu warriors would use their shields to hook and shove away their opponent's shields, which exposed their adversaries to spear thrusts. Combined with the shifts in weaponry and techniques in armed combat, Shaka's forces employed “the beast's horns” formation that was like the flanking maneuvers of the Macedonian hammer and anvil (Knight Reference Knight1995:192). The Zulu formation was composed of four major units: the chest, horns (two separate units), and loins. The chest was the unit in charge of directly confronting adversaries. Meanwhile, the horns tried to surround either side of the opposing formation. The loins were kept in reserve to fill any gaps that developed during the attack. The flanking tactic and shifts in armament were accompanied by changes in the mustering of warriors.

Figure 5. Map of Shaka's conquests ca. a.d. 1816–1828. Modified by Bracken from Wikipedia (2020), used under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Broad social changes accompanied the developments in tactics and weaponry, engendering loyalty among the ranks in a similar manner to the land distributions under Philip II. During Shaka's reign the amabuthu (singular ibutho) age-grade system was used to weaken local bonds and foster allegiance to the ruler (Chanaiwa Reference Chanaiwa1980; Deflem Reference Deflem1999; Edgerton Reference Edgerton1988; Knight Reference Knight1995; Morris Reference Morris1965). This system had been employed to create regiments by mustering men of the same age from a particular polity. Shaka implemented the amabuthu among the Zulu to incorporate men of the same age from various parts of his subjugated territories. Each regiment (i.e., ibutho) was distinguishable on the battlefield by its armaments, uniforms, and accoutrements. Members of each ibutho lived together and performed duties for the king, including martial training. Each regiment was funded by the royal treasury, which included the partial redistribution of spoils gained from war (Chanaiwa Reference Chanaiwa1980:15–16). Via the amabuthu system, Shaka was able to create regiments that were loyal to him and weakened the hold of “territorially based kinship relations” (Deflem Reference Deflem1999:376). In other words, Shaka was able to create an overarching polity that dominated many rival forces through martial force or threat thereof and used a modified age-grade system to centralize power by weakening local bonds and making warrior regiments from across his subjugated territories loyal to the king.

The particulars of success in combat and territorial expansion for both Philip II and Shaka, which would have been glossed over in Carneiro's (Reference Carneiro1970) circumscription model, demonstrate how changes in the practice of war could play a crucial role in the process of forming a state. Changes in weaponry, tactics, and professionalization were linked to a process of engendering loyalty to a central authority through the distribution of resources and identity formation. This loyalty also depended on continued martial success. Investigation at this level of detail requires going further than assessing warfare in simple terms of presence or absence, or uncritically overlaying familiar paradigms from the Western military tradition. Prying into the nuance of how martial practice played out at multiple scales down to the level of the individual participant allows for a robust understanding of the interrelationship between warfare and other aspects of social life. We now turn a discussion of war in the origin and disintegration of Mesoamerican states.

MESOAMERICAN STATE FORMATION AND DISINTEGRATION

Warfare as an impetus for the coalescence and dissolution of Mesoamerican societies has gained general acceptance within the scholarly community. The relationship between war and the origins of states in the Maya area remains up for debate, though current work is uncovering increasing evidence of Late Preclassic fortifications and potential evidence of warfare in the Middle Preclassic (Bey and Gallareta Negrón Reference Bey, Negrón, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Bracken Reference Bracken2023; Brown and Garber Reference Brown, Garber, Brown and Stanton2003; Estrada-Belli Reference Estrada-Belli2011; Inomata Reference Inomata, Scherer and Verano2014). Contextualizing these findings requires comparison with insights from Mesoamerica more broadly.

In Formative-period Oaxaca (1800 b.c.–150 a.d.), the presence of fortifications, buffer zones, burning, settlement shifts (i.e., occupying defensible terrain), and martial iconography are used to argue the Zapotec state formed through predatory expansion (Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2012; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2003; Redmond and Spencer Reference Redmond and Spencer2012; Sherman et al. Reference Sherman, Balkansky, Spencer and Nicholls2010; Spencer Reference Spencer2003). Proponents of this model argue that, in a context of competing chiefly polities, a community centered at Monte Alban was able to subjugate rivals and outside territories. The process of administering distant territories had a cascading effect that led to the formation of the Zapotec state. This expansionist model has generated vigorous debate and deeper interrogations of martial practice. To examine warfare in Preclassic Oaxaca, Workinger and Joyce (Reference Workinger, Joyce, Orr and Koontz2009) demonstrate the variability that existed in pre-Columbian martial practice and methods of imperial administration. Mesoamerican peoples could have engaged in raiding, flowery wars, pitched battle, and siege warfare. The outcomes of combat varied from the taking of captives to territorial conquest.

Workinger and Joyce (Reference Workinger, Joyce, Orr and Koontz2009) also raise the crucial issue of logistics (see also Hassig Reference Hassig1992; van Creveld Reference van Creveld1977). If the rulers of Monte Alban were able to conquer other territories, perhaps through numerical superiority (Flannery Reference Flannery1999:17), then how did they supply their warriors across an area that might have ranged up to 20,000 km2 and included campaigns across 160 km of mountainous terrain? We ask, if the rulers of Monte Alban were able to dominate their rivals through coercion and force, then what gave them the martial edge? Flannery (Reference Flannery1999:5) suggests that a switch from raiding to “organized warfare” may account for how one community was able to dominate the Oaxaca Valley and expand into other territories. Yet, he does not examine this assertion of tactics any further. In addition to the institutional shifts occurring at the level of administration and governance, could it be, like the Macedonian and Zulu examples, Zapotec territorial expansion was made possible through shifts in tactics, strategy, armament, logistics, or several of these factors? Both Old World case studies demonstrate how shifting tactics to achieve overwhelming martial success is not a simple process and can lead to fundamental alterations in social organization.

Research from the Puuc region of Mexico begins to paint a richer picture on how the growth of later Maya polities might have been tied to shifts in martial practice. Investigators have long debated whether Uxmal was the seat of a regional capital or under the control of Chichen Itza during the Terminal Classic (e.g., Bey and Gallareta Negrón Reference Bey, Negrón, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Cobos et al. Reference Cobos, de Anda Alanís and Moll2014; Ringle Reference Ringle and Braswell2012). In favor of an affiliated, yet independent status for Uxmal, Bey and Gallareta Negrón (Reference Bey, Negrón, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019) argue the expansion of the polity was propelled by a possible alliance with Chichen Itza and martial reforms. Building on the work by Ringle (Reference Ringle and Braswell2012), they argue for a shift to a “Toltec”-style of military organization at Uxmal during the reign of Lord Chac (Chan Chahk K'aknal Ajaw) that included the implementation of new symbols, ideology, and a council of six war leaders to assist the ruler (Bey and Gallareta Negrón Reference Bey, Negrón, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019:130, 140). The argument for a shift in martial practice is largely based on detailed analysis of iconography from the Nunnery Quadrangle at Uxmal and other sites in the Puuc region. Ringle (Reference Ringle and Braswell2012) also considers his analysis to be speculative in many instances. Nonetheless, the Uxmal case study raises points for debate and future analysis. Does an emphasis on central Mexican iconography, such as the goggle-eyed feather serpent, signal a major shift in Puuc Maya martial practice? Although there is much ethnohistoric evidence for war councils among the Aztec and Maya, did this type of decision-making during the Terminal Classic mark a shift away from the K'uhul Ajaw form of governance and its apparent focus on the individual ruler (e.g., Hassig Reference Hassig1992)? Perhaps the Nunnery Quadrangle at Uxmal, which Ringle (Reference Ringle and Braswell2012) argues is a council house, provides evidence of non-rulers gaining greater control and influence over the conduct of war.

The questions raised by researchers in the Puuc region are significant because shifts in command structure can have a major impact on the battlefield. An illustrative case comes from nineteenth-century Europe. Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of Staff of the Prussian army, argued the armed forces of his time had become too massive and difficult to move as a single body (Hughes Reference Hughes1993). Instead, he championed the deployment of separated armies that would only converge to take part in a battle. The movement of separated armies was facilitated by the use of railroads, but communication was still a problem. Because von Moltke and his contemporaries could not send information to disparate armies in real time, his tactical scheme emphasized some allowance for the decision-making ability of subordinate commanders. Commanders could deviate from the details of Moltke's plans as long as the actions in the theater of war fulfilled the overall intent of the high command. This tactical flexibility was a hallmark of Prusso-German martial practice until 1945 and has influenced contemporary United States warrior culture (Lynn Reference Lynn2003). Returning to Mesoamerica, the armed forces of the Aztec Triple Alliance would move as separate units, which then converged in a place intended for battle (Hassig Reference Hassig1988). Did they, like the nineteenth-century Prussians, employ tactical and decision-making flexibility to establish some of the martial edge needed to subjugate other Mesoamerican polities? This consideration of movement, Oaxacan polity expansion, and command structure at Uxmal opens avenues for examining Classic-period power struggles in the southern Maya lowlands.

What is known about the Classic period, especially the Late Classic, implies political intrigue and machinations that would readily offer storylines for television drama. To enhance their own power, rulers built networks of kin, allies, and subordinates to foment the exchange of goods, people, and ideas. For example, marriage practices played a central role in legitimizing rulers and the established kinship networks may have been used to muster warriors (Josserand Reference Josserand and Ardren2002, Reference Josserand2007; Sabloff Reference Sabloff2018). Via marriage, martial success, and other means, the Kaan or “Snake” dynasty at Calakmul was able to build an extensive network of power over other polities. By pairing epigraphic data with other lines of archaeological evidence it is possible to start outlining some of the broad strategic aims of Maya polities, such as the Late Classic geopolitical machination of the Kaan (“Snake”) and Tikal dynasties (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008).

As in Formative-period Oaxaca, we know warfare was central to the Maya political process. Yet questions remain about tactics, logistics, armament, and motivation. Martin (Reference Martin2020:4) highlights that researchers have a robust understanding of the who, what, where, and when of Classic Maya geopolitics, but lack much of the how and why. In line with our tripartite conceptualization of war-making (i.e., preparation, engagement, and outcomes), he further argues, “[w]e know that warfare was a recurring feature of Classic Maya life, but the lack of detail in the texts makes it hard to appreciate why it was initiated, how it was conducted, or precisely what it sought to achieve” (Martin Reference Martin2020:338). Now it is clear that martial practice among Classic Maya peoples involved captive taking, seasonal considerations, “ritual”/other-than-human elements, and hierarchical relations between political actors (i.e., overlords and secondary elites referred to as sajal). Investigators have even been able to broadly trace the steps in particular campaigns, such as the move of Kaanul (“Snake”) rulers from Dzibanche to Calakmul. Glyphic evidence provides clues for different the types of martial practice, such as “star wars” that were highly consequential versus the more ubiquitous “chop” (i.e., ch'ak) statement (Martin Reference Martin2020; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019). Much of what these terms meant in practice remains elusive, though the “chop” statement does in one case refer to the beheading of a Copan ruler, as described below. With increasingly detailed information on landscape and causeways, it may be possible to pair glyphic data with estimations of warrior footspeed (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Ruiz1998; Hassig Reference Hassig1992) to better understand tactics, logistics, unit size, and perhaps one day even find a battlefield. In addition to prompting deeper examination of processes of polity expansion and state formation, can a study of martial practice, as Bey and Gallareta Negrón (Reference Bey, Negrón, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019) suggest, help investigators better understand processes of political and demographic disintegration?

Scholars agree that social conflict played a crucial role in the Terminal Classic collapse, though not all regions show signs of depopulation or entanglement in war. The strongest data for war leading to collapse has been uncovered in the Petexbatun region of Guatemala. Researchers in the region have demonstrated that the massive depopulation and cessation of monumental construction at several sites directly resulted from an attack (Demarest Reference Demarest2006; Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, O'Mansky, Wolley, Van Tuerenhout, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo1997; Inomata Reference Inomata2008). Building from the Petexbatun research and the extant corpus of Maya writing, Kennett et al. (Reference Kennett, Breitenbach, Aquino, Asmerom, Awe, Baldini, Bartlein, Culleton, Ebert and Jazwa2012) argue that increasing warfare at the end of the Classic period was tied to episodes of drought triggered by climactic shifts. Based on uranium-thorium dating and the measurement of oxygen isotopes (δ18O) in sequences of stalagmite growth, they argue episodes of multidecadal droughts were the impetus for a two-stage collapse. The first episode of multidecadal droughts occurred around a.d. 600, which “triggered the balkanization of polities, increased warfare, and abetted overall sociopolitical destabilization” (Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Breitenbach, Aquino, Asmerom, Awe, Baldini, Bartlein, Culleton, Ebert and Jazwa2012:791). These events would set the stage for the widespread abandonment of sites in the Petexbatun by the middle of the eighth century.

If the above collapse scenario is correct, then how did the process of balkanization occur? Perhaps the creation of a politically fragmented landscape was driven by a martial stalemate. The Killer King Complex no longer holds up to scrutiny, but could cultural norms of war still have contributed to the process of sociopolitical deadlock? Addressing this issue would require a deeper examination of Classic-period tactics. Like the pre-Philip Macedonians or pre-Shaka Zulu, Late Classic Maya peoples might have been fighting with matched strategies, tactics, armaments, and logistical capabilities that did not allow any one group to effectively overpower opponents and create an overarching polity. Recent insights into total war at Late Classic Witzna, however, reveal that Maya warriors could occasionally achieve overwhelming martial success (Wahl et al. Reference Wahl, Anderson, Estrada-Belli and Tokovinine2019). Given the many questions we have raised, we now turn to discussing how the articles in this Special Section contribute toward a deeper understanding of Maya martial practice.

EXAMINING THE PRACTICE OF MAYA WARFARE

An emphasis on the concrete and practical side of war is necessary to understand how conflict relates to the human experience. As numerous case studies from across the globe highlight, human activity in the process of making war can have profound impacts on political economy, landscape, and culture (Brady Reference Brady2012; Bricker Reference Bricker1981; Chanaiwa Reference Chanaiwa1980; Deflem Reference Deflem1999; Flannery Reference Flannery1999; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2012; Lynn Reference Lynn2003). If the Macedonian army had not been reorganized during Philip's reign, would Greek culture still have the foundational influence on Western societies seen today? Gilliver (Reference Gilliver and Gilliver2002a:1) argues “[t]he political map of much of modern Europe can be traced back to Julius Caesar's nine years of campaigning [in Gaul].” Without Roman discipline and infantry tactics to expand their empire, would Western Europe exist as a political and cultural entity (e.g., Anglim et al. Reference Anglim, Rice, Jestice, Rusch and Serrati2002; Goldsworthy Reference Goldsworthy2005)? The effects of war-making extend far beyond an episode of combat, implicating as well martial preparations such as fortification construction, warrior training, procuring weapons, securing loyalties, building morale, formulating strategy, and determining tactics. The effects of war are also felt in the aftermath of hostilities, which can lay the groundwork for new cycles of conflict (e.g., Keeley Reference Keeley1996; Kim and Kissel Reference Kim and Kissel2018). For example, the Treaty of Versailles set the conditions for the end of World War I but through its harsh penalties on Germany also provided some of the basis for the Second World War (Taylor Reference Taylor1996). War is not a variable that can be simply added and stirred into a model or conceptual framework. It must be unpacked, understood conceptually, and examined down to the level of practice in particular cultural and historical contexts. To address this issue, we turn to potential avenues of future research and introduce some of the major contributions of the authors in this Special Section.

Colonial-period accounts provide evidence of numerous engagements between armed groups of Maya warriors and Spanish-led forces (Asselbergs Reference Asselbergs2004; Bassie-Sweet et al. Reference Bassie-Sweet, Laughlin, Hopkins and Casimir2015; De Vos Reference De Vos1980; Díaz del Castillo Reference Díaz del Castillo2008; Feldman Reference Feldman2000; Jones Reference Jones1998; Pagden Reference Pagden1986; Restall Reference Restall, Scherer and Verano2014; Restall and Asselbergs Reference Restall and Laurence Asselbergs2007; Simpson Reference Simpson1964). In this Special Section, Hernandez (Reference Hernandez2023) employs ethnohistoric documents to examine how the Maya built and used fortifications. His analysis focuses on the use of lacustrine environments with rugged terrain to create layers of fortification revealing how the design of a martial landscape ties into the institutionalization of inequality. In a similar vein, Miller (Reference Miller2023) analyzes Spanish records to understand the tactics employed by the Maya in battle, including how they organized units and dressed for war. She applies these Colonial-period insights to interrogate Classic-period martial practices depicted in the Murals of Bonampak. Thus, she bridges data sources to unpack martial practice in both periods.

In addition to fighting the Spanish, Maya peoples also told of armed conflicts and campaigns among one another, such as the martial engagements between rival factions at Mayapan and K'iche’ migration history recorded in the Popol Vuh (Christenson Reference Christenson2007; Edmonson Reference Edmonson1982; Roys Reference Roys1933). The Classic-period hieroglyphic and pictorial record provides ample evidence of how armaments figured into elite Maya conceptualizations of war at the time (Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Brown and Stanton2003; Stone and Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011; Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019). One of the most common war references is the axe glyph or ch'ak, which means “to chop.” The “chop” war statement is typically used in reference to places but was also used to denote the literal chopping of a Copan ruler and the defeat of his polity at the hands of Quirigua. Another reference to war is “to knock down a spear and shield” (jubuuy u took’, u pakal), which signifies the defeat of an entity or a general cessation of hostilities (Martin Reference Martin2020:211). Given the Colonial-, Postclassic-, and Classic-period associations of armaments with war statements, future researchers should consider how the materiality of war shaped Maya subjectivities. Assessing conflict from an embodied perspective provides a fruitful avenue of inquiry in this direction and further means to continue unpacking martial practice.

A consideration of embodiment and the role of captives in this Special Section moves the discussion of war out of the realm of abstraction by highlighting the tangible realities of Maya war-making. Studies of embodiment reveal how engagement with the tangible, physical world creates meaning, shapes culture, and perpetuates inequality. Accordingly, Earley (Reference Earley2023) demonstrates how the captive body played a central role in Classic-period social life. Beyond the narrative of captive as sacrificial victim, she argues that corporeal interaction with war-related monuments, primarily through viewing them, served to enculturate people into a particular type of warriorhood. Sculptures formed the literal embodiment of captives and communicated the central role of elite bodies in the maintenance of the status quo. Extending the concept of embodiment, Bracken (Reference Bracken2023) and Hernandez (Reference Hernandez2023) individually examine how interactions with landscape shaped social life via the task of preparing for war. Bracken pairs geospatial analysis to understand how martial architecture is shaped by martial concerns and how these constructions in turn shape how people move within a community. Expanding on this line of reasoning, Kim and colleagues (Reference Kim, Hernandez, Bracken and Seligson2023) emphasize a regional approach to the study of war during the Classic period. In their formulation, fortifications and landscape provide a means to contextualize various lines of evidence for understanding, at multiple scales, the impacts of war-making. Overall, people work with landscapes to create fortifications and martial imagery, and once in place those constructions actively shape the human experience by, for example, their sheer physicality and constraint on movement, maintenance requirements, or meaning. Through the process of active co-constitution people and landscapes embody one another (Ingold Reference Ingold1993).

CONCLUSION

Our hope is the articles in this Special Section ignite a broader discussion on martial practice. Beyond broad categories and definitions, how did Maya peoples make war? What is entailed in various tactical categories, such as raiding or battle? How did these forms of combat change over time and did their implementation vary across communities or regions? How did the process of making war figure into political and economic goals? Investigation of these matters shifts the analysis of war away from an overbroad, reified abstraction to a situationally specific process that drives social relations and myriad aspects of the human experience. In so doing, we seek to provide productive new directions that orient future investigation by foregrounding practice, or what embodied social beings do, in particular cultural and historical contexts. Through a holistic assessment of weaponry, tactics, settlement patterning, fortification, political structures, and a host of other factors, we can unravel a military history of the Maya that complements studies of Old World cultures.

RESUMEN

Los artículos en esta Sección Especial investigan las dinámicas concretas y la experiencia vivida en la guerra en el contexto cultural de los mayas. El objetivo es dejar de tratar la guerra como una categoría abstracta y, en cambio, considerar el conflicto social al nivel de la práctica. Entendemos práctica como lo que hacen los seres sociales encarnados dentro de un particular contexto histórico y cultural. Este marco conceptual nos lleva a preguntar ¿cómo se prepararon y participaron los pueblos mayas en el combate, y cómo administraron los resultados de la guerra? ¿Qué se puede decir sobre estrategia, operaciones y tácticas en el pasado? ¿Cómo usaron armas, armaduras y fortificaciones los mayas? Considerando estas preguntas, discutimos cuestiones de la identificación e interpretación de la guerra precolombina. Demostramos cómo la guerra, el asalto en particular, ha sido puesta en una caja negra en los estudios mayas anglófonos. En otras palabras, esta forma de conflicto social se invoca a menudo en modelos de la vida social pasada, pero sus complejidades internas se subestiman en gran medida. Luego, en una perspectivo transcultural, analizamos el desarrollo y la desintegración de los estados, incluyendo el área Maya y valle de Oaxaca. Terminamos nuestra introducción proporcionando una descripción general de las contribuciones individuales en esta Sección Especial y su relevancia más amplia para los debates en los estudios mayistas y mesoamericanos.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, we must thank Nancy Gonlin for her encouragement and assistance in the creation of this Special Section. A casual remark during an SAA meeting turned into a wonderfully massive project. We would also like to extend deep gratitude to the individual authors in this Special Section for agreeing to join us in this foray into Maya martial practice and the reviewers for their helpful comments. A special thanks goes out to Andrew Scherer, Charles Golden, Stephen Houston, Mallory Matsumoto, Alejandra Roche Recinos, Omar Alcover, Whittaker Schroder, Mónica Urquizú, and Socorro Jiménez who could not join this Special Section but contributed to this endeavor nonetheless. Hernandez would like to give many thanks to Kristin Landau, little Leo, and Luna for their support in the development of this manuscript. Bracken wishes to thank his wife Cailin, Milo and Aurelia, the babies, his parents, Doug and Nina, and Jeremy, the dog, for their support throughout, as well as his coauthor Chris for seeing this project through as we both became fathers and weathered a pandemic. This research was supported by a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (SPRF# 1715009) awarded to Hernandez and National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant (BCS# 1836317) awarded to Bracken.