Alice: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

The Cheshire Cat: “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”

Alice: “I don't much care where.”

The Cheshire Cat: “Then it doesn't matter which way you go.”

—Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in WonderlandThis conversation between Alice and the Cheshire Cat can easily be a mirror of archaeological heritage management in many corners of the world. It is not that we do not know where to go, but we have not invested a lot of thought into creating a creative and holistic practice that is in line with modern needs and ethics. More often, we apply a patch to problems while continuing to rely on old management models. Building on the preliminary results of the #pubarchMED project, this article presents the variety of management models that exist across the Mediterranean and reflects on how countries approach preventive and rescue archaeology as well as the relationship between archaeology and society—all in the context of creative mitigation strategies and the way current practices relate to the concept in very different ways.

PRELIMINARY NOTES ON PUBLIC AND PREVENTIVE ARCHAEOLOGY, AND SOME STANDARDS OF PRACTICE

Writing from the east side of the Atlantic Ocean for American audiences can lead to different approaches to similar topics and differences in the definition of commonly used concepts. As such, I feel it essential to start with some clarifications in the terminology and a broad overview of other practical matters.

• Public Archaeology: The European definition (Ascherson Reference Ascherson2000; Schadla-Hall Reference Schadla-Hall1999) goes a step beyond the common use in the United States, studying the broad relations between archaeology and contemporary society (politics, economy, cultural impact, etc.) in all its forms (Almansa-Sánchez Reference Almansa-Sánchez2018). It includes both main approaches in America (commercial practice and outreach) but tries to understand the underlying circumstances that brought us there.

• Preventive Archaeology: This refers to practices of preventing archaeological resources from being affected by development projects. Introduced as common practice on paper in France (Schlanger Reference Schlanger and Silberman2012), it is still based on basic standard mitigation practices in those countries that try to apply it (Bozóky-Ernyey Reference Bozóky-Ernyey2007). The main difference over most models lies in the full intervention during the planning process. It is supposed to be the first mitigation solution during Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) in Europe. The reality is that, in most cases, the process goes straight to rescue archaeology.

• Rescue Archaeology: This is an intervention on an archaeological site at risk of being destroyed by any factor, human or natural (Rahtz Reference Rahtz1974). It was supposed to be used only as last resort in Europe, but it is still a challenge for North Africa. The persistent need for rescue archaeology also shows the wide variety of realities we still face, even within the European Union (Aitchison et al. Reference Aitchison, Alphas, Ameels, Bentz, Borş, Cella, Cleary, Costa, Damian, Diniz, Duarte, Frolík, Grilo, Kangert, Karl, Andersen, Kobrusepp, Kompare, Krekovič, da Silva, Lawler, Lazar, Liibert, Lima, MacGregor, McCullagh, Mácalová, Mäesalu, Malińska, Marciniak, Mintaurs, Möller, Odgaard, Parga-Dans, Pavlov, Kocuvan, Rocks-Macqueen, Rostock, Tereso, Pintucci, Prokopiou, Raposo, Scharringhausen, Schenck, Schlaman, Skaarup, Šnē, Staššíková-Štukovská, Ulst, van den Dries, van Londen, Varela-Pousa, Viegas, Vijups, Vossen, Wachter and Wachowicz2014), and it can be compared to salvage archaeology in the United States.

• Archaeological Heritage Management (AHM): Far from the connotations of cultural resource management (CRM) and other concepts used mainly in North America, AHM refers to the set of practices in place for dealing with the archaeological process, from planning to presentation (Martínez and Querol Reference Martínez and Querol1996). These practices are conducted by many different actors at many different stages, and mitigation is a significant part of the process.

• Public Domain: Probably the easiest of the five concepts to understand, public domain is essential to understanding archaeology in the Mediterranean. It stands on the principle that any known (and in many cases, unknown) archaeological remains belong to the public, usually translated as “the State,” but also understood as “the People,” giving the State a role as guarantor of its protection (Matsuda Reference Matsuda2004). In some cases, it focuses only on artifacts (movable) as a result of the extensive looting and the illicit trade of antiquities in the region (Rodríguez Temiño Reference Rodríguez Temiño2015). Public domain is the foundation for one of the major procedures that allows the control of archaeological activities: permissions granted by the administration for most types of intervention.

Although these concepts are backed by extensive literature, their use can be misleading when we change language or continent (we have over 15 languages in the region, with many dialects, and even the word “heritage” changes meaning among them). Many practitioners follow different definitions, and even policy makers may use these or other terms with a different sense. Even as steps toward standardization at every stage of the archaeological process are becoming more and more crucial, we are far from finding a common ground. We are talking not only about the possibility of sharing and comparing results among the different actors that intervene in the process but also about basic terminology and the concepts these words represent.

#PUBARCHMED AND PROFESSIONAL PERCEPTIONS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE MANAGEMENT

As I begin this discussion of professional perceptions, I present the early stages of an ongoing project. Consequently, most of the data gathered have not been fully processed, and the following sections rely on a preliminary analysis of the interviews, visits, and current literature. At this stage, the protocol does not allow direct reference to the interviews because it could pose a risk to the anonymity of the informants.

Public Archaeology in the Mediterranean Context (#pubarchMED) is the name of a project that explores the variety of models and solutions implemented in the Mediterranean for the management of archaeological heritage. It aims to define a set of tools that can help improve the outcomes of our work after a critical analysis of current practices from the perspective of public archaeology.

The project approaches AHM from the personal perception of professionals in each country, who come from different backgrounds, hold different positions, and are in different stages of their careers. There are limitations to this approach that range from the misrepresentation of certain countries or actors to the record of overly official or unfairly critical discourses. The selection of the sample has been biased first by me, through the contacts I already had in each country; then by language, given that there are not always options to have the desired fluidity of communication with the interlocutor; but mostly, by time constraints and the difficulty of contacting people in certain positions, especially in administration. Despite this, the sample gathers colleagues from every country, representing every actor in the picture, from universities and research centers to museums, administrations, private companies, and nonprofit organizations. Overall, each interviewee complements the broader picture, offering personal insights on their experience. Ultimately, the sample will collect the views of over 200 people, whose opinions will be complemented by personal observation and the analysis of the existing literature.

One of the reasons to choose this approach is the fact that AHM is not an exact science, and legal documents are interpreted in different ways every day, depending on the situation. This creates an environment of arbitrariness that results in multiple professional conflicts, as well as an unclear impact on the protection of archaeological heritage and society more widely. Similarly, the opinions of different professionals on certain AHM topics can be conflicting because they are rooted in the specific interests of each collective within the archaeological sector. Only a better understanding of the whole picture can provide an idea of the complicated dynamics that operate in daily practice.

Face-to-face oral interviews were chosen as the preferred method, with a total of 15 semi-structured questions that had been tested to gain confidence and elicit honest answers. However, the difficulty of traveling to certain countries or completing some of the interviews in the given time led to a portion of the interviews being conducted by e-mail (in writing and via audio recording). As the COVID-19 crisis has developed and made travel impossible for many weeks, the use of online interviews has increased substantially.

Mitigation is one of the core topics addressed during the interviews, and it is crucial for AHM. During the last decades, the impact of development in the Mediterranean has been a major issue for management. The expansion of the European Union, whose funding for developing infrastructures and strict legal framework for EIA has been crucial for developing current archaeology in the region, affects more than just member countries. Adjacent regions are either in negotiations to join, or they are interest areas for commerce, and they receive significant amounts of money to improve infrastructure and develop industry. Therefore, the construction sector keeps growing (UNEP/MAP 2016) and affecting archaeological heritage across the Mediterranean.

The emergence of public archaeology in the early years of the twenty-first century have created new potential for the implementation of new practices in the archaeological process, but the situation is far from perfect. On the one hand, there is a poor implementation in academic practice and teaching. On the other hand, preventive and rescue interventions are still mostly conducted on a conservative basis. There is still a lot of work to do in this sense.

A BROAD PICTURE OF THE MEDITERRANEAN CONTEXT

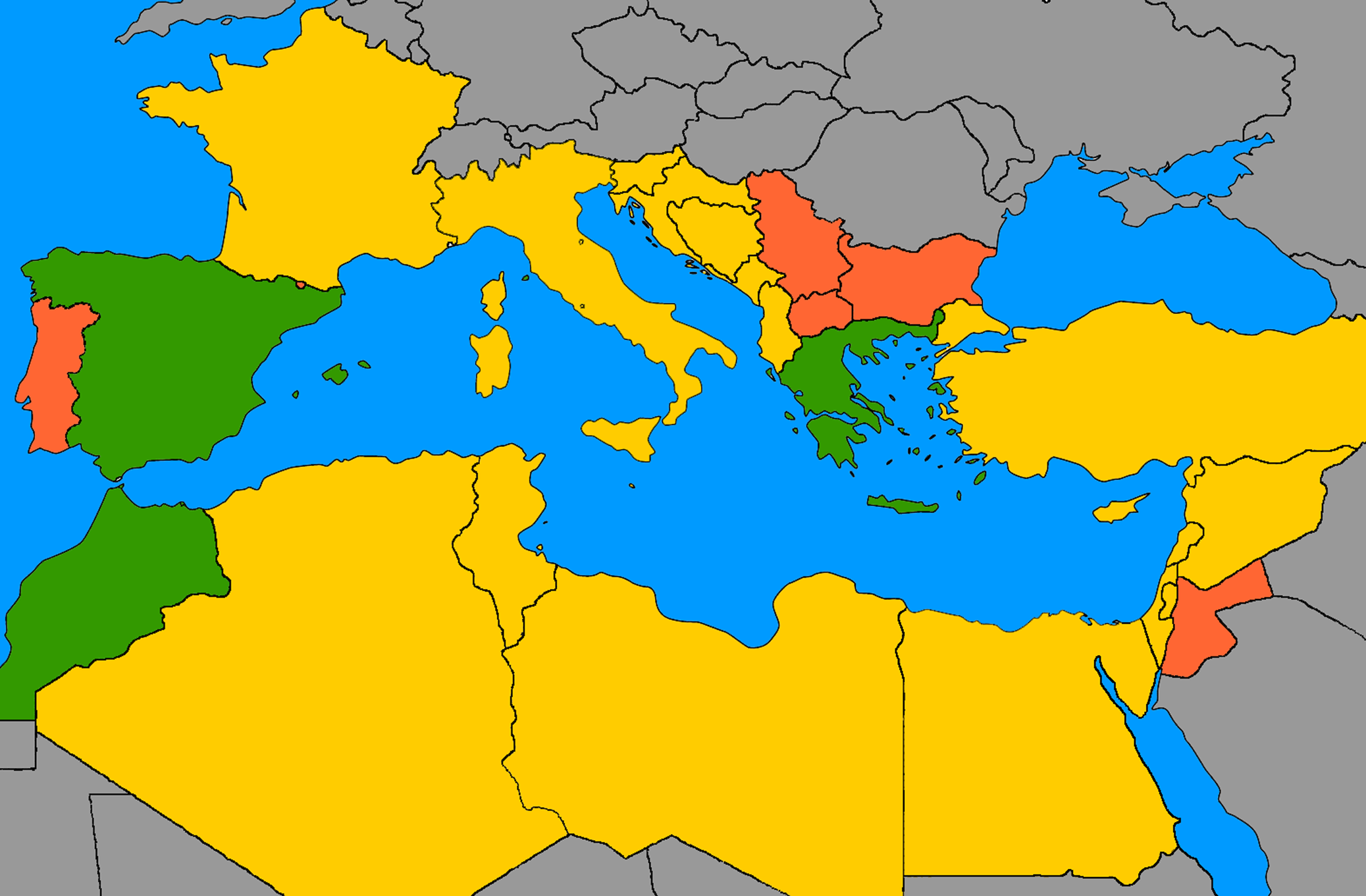

Writing about the Mediterranean is a difficult task. #pubarchMED selected 32 countries to circumscribe a region whose limits can be difficult to define (Figure 1). Furthermore, the differences among them are obvious and sometimes large, including in the management of archaeological heritage. For example, San Marino is smaller than the municipalities of some neighboring cities in Italy. Cyprus, in the European Union, is a partitioned country: a portion of the southern part of the island is occupied by British military bases, and the north was proclaimed independent after the Turkish occupation in 1974, but it not recognized by the international community. Kosovo and Montenegro are among the youngest states in the region, and they experience ongoing conflicts. Syria and Libya, devastated by civil war and foreign intervention in recent years, have weak institutions and a massive problem with looting. Spain is divided into 17 mostly autonomous regions; although they share some basis for AHM, they still lack any standardization. Israel has an effective AHM model, affected by an open conflict with the Palestinian territories and the permanent disputes over land and history. France is a country that many practitioners look to as a model of best practice, but it still raised concerns during the interviews. Despite all these differences, the countries are similar in facing the challenge of managing a massive amount of archaeological heritage that is continually threatened by development. They share common problems and have different solutions. Have they been creative?

FIGURE 1. Map of the Mediterranean Basin with the countries selected for the project. The focus countries are in green; those with no direct face with the Mediterranean Sea are in red; the others that are part of the study are in yellow.

Understanding the Background of the Mediterranean Basin in a Few Words

To understand many of the current dynamics, we would need to revisit the distant past. Instead, I offer a basic summary of the different areas as I personally understand them and explain how that affects their approach to the management of archaeological heritage. The countries are heterogenous entities with rich political backgrounds that make practice different in each one.

• The European Union: The northwestern part of the basin is part of the European Union. Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Cyprus form a far-from-homogeneous group that has had to adapt to major European legislation, but they do it in different ways.

• The Balkans: After the fall of Yugoslavia at the end of the 1990s, several new nations had to develop their own institutions in a post-conflict world. Serbia retained the former institutions. Bosnia and Herzegovina is in a complicated state because archaeology was not part of the peace agreement. Meanwhile, ethnic conflict remains in the background while new states such as Montenegro start to build their institutions. Slovenia and Croatia rapidly joined the EU.

• Small countries: Gibraltar, Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vaticano are independent or semi-independent entities within, or next to, bigger countries, and they are remnants of past politics. It might seem that archaeological heritage is not an issue in these places, but as situations arise, these entities have different ways of dealing with them depending on which “big brother” they mimic.

• The Middle East: After the end of the colonial powers and the establishment of the state of Israel, the region had to deal with very weak stability and an overwhelming presence of foreign missions. Inheriting the practice of their former colonial metropolis, they practice some surprisingly advanced approaches. Even so, conflict remains in the background, which adds continual risks to the safeguarding of archaeological heritage.

• North Africa: This is probably the area in which AHM is the least developed, although it has recently started facing the threats that development poses for archaeological heritage. Much of the region is under authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes, even after the Arab Spring. AHM is still underdeveloped even in traditionally active countries such as Tunisia or Egypt, which have a rich history in the management of archaeological heritage.

• Turkey: After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the newly formed state focused on its own territory but still affected surrounding areas. Currently facing political challenges, its response to AHM and an active foreign policy—including direct interventions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Cyprus, or Lebanon—deserves a special mention.

Even as geopolitical differences provide some baseline differences across the region, a wide range of other issues shapes the practice of AHM in each area.

• Legal traditions: Most of the legal developments in the Mediterranean Basin came from the legal traditions of each country. Although Mediterranean Europe developed its own legal traditions from Roman law, there are remnants of British law in places such as Gibraltar, Malta, and Jordan. This impacts basic issues such as land ownership and use, although contemporary trends have helped to shape policy in a deeper way. For example, the Franceschini Commission in Italy (Commissione Franceschini 1967) defined the basis for a new management of cultural heritage in Italy and was widely followed by other surrounding countries when they faced their new legislations. At the same time, the UNESCO Conventions and other European regulations affected policy deeply (Almansa-Sánchez Reference Almansa-Sánchez2017).

• The conflicts: Syria and Libya are the most recent open armed conflicts in the region. Other territories, however, are still overcoming recent conflicts that clearly affect the management of archaeological heritage. North Cyprus is only recognized by Turkey, making occupation forces in the territory necessary. Kosovo is in open social and political conflict with Serbia, and it also needs the presence of peacekeepers. Bosnia and Herzegovina is still managed under the peace agreements with two clearly defined entities that draw the frontline of the war as the border. Israel and Palestine, as well as other actors in the region, have not ceased hostilities, even in regard to archaeology.

• Other conflicts: Many other conflicts are still present in the region, with the rise of nationalism. For example, Spain and Catalonia have been in open political and civil conflict for several years now. The recent Prespa Agreement (2018) has not ended a long-lasting conflict between Greece and what is now North Macedonia. Archaeology has played an essential role in the construction of historical identities, including in the rise of far right and other extremist movements across the region.

• Illicit trade and looting: Although there is a constant fight against looting and the illicit trade of antiquities (see Mackenzie et al. Reference Mackenzie, Brodie, Yates and Tsirogiannis2019), the recent conflicts in the Middle East have fostered a new peak (Hardy Reference Hardy2011–2019). Looting has never ceased to be a problem, and it continues to be crucial to the shaping of many policies.

With all these considerations in mind, the panorama becomes both complex and exciting. Although it is extremely difficult to identify commonalities beyond both the general will to protect archaeological heritage and limited resources (while the data to back up this claim are still being analyzed, this is one of the few issues that comes up in almost every interview), the variety of models and solutions applied will be an important focus during the next stages of the project. After all, one of the common challenges we share is the large amount of archaeological heritage—in many cases, monumental—that needs to be managed while trying to find the balance between conservation and development. This is the main space for creative mitigation. It is large, full of difficulties, and open to many critics, but surprisingly rich.

Exploring the Range of Models in Practice within the Mediterranean Basin

No two countries practice AHM in the same way. Furthermore, there are even differences in the details of management within regional entities in each country. The legal framework does not set clear or specific heritage policies in most countries. Although the procedures and bureaucracy asking for permits or intervention in the planning process might be clear in most places, the actors taking part in the process or the final decisions over the sites that require intervention are mixed.

I have defined a gradient of models depending on the outsourcing of the management of archaeological heritage—from countries where the state, through public administration, is in charge of the whole process to others where private initiative has taken control of most of the tasks. To make it simple, I defined three basic models: the Public Model, the Mixed Model, and the Private Model (Almansa-Sánchez Reference Almansa-Sánchez2020):

(1) The Public Model is one in which the competent administration (either by itself or through different departments or agencies) is in full control of the whole archaeological process, with no intervention of third-party actors beyond academia.

(2) The Private Model is one in which the competencies of the administration have been diminished to a minimum, with private initiative taking the lead in the process (no need of permits for excavation, private museums and semi-opened trade, private management of sites, etc.).

(3) The Mixed Model falls between the two extremes, which are rarely found. Normally, the competent administration keeps some of the main roles, and private actors are allowed to intervene to an extent, either to reduce the scheduled time for rescue archaeology or to manage certain aspects of a project. The basic public or private model defines the overall shape of these processes.

The influence of private intervention in the Mediterranean Basin is unequal among the different countries, but it is limited by the concept of public domain. Recognizing this, the state is forced to be an active part of the management process, either by granting permits for excavations (such as Portugal and Spain) or the use of archaeological sites, or by being the primary manager of the process, including preventive and rescue excavations. Some countries have created a department within the administration to manage archaeological work (for example, Lebanon, Cyprus, Egypt, and Serbia). Meanwhile, others have public bodies that work independently (as in France and Morocco), even as companies (such as the Israel Antiquities Authority, where approximately 80% of its budget comes from contract work). Most countries, however, are open to outsourcing the undertaking of excavations in moments of need (such as Greece), or when forced by competency regulations (again, Israel), as well as the direct management of specific sites (such as Spain and Italy). Even the direction of the interventions is controversial in a context of contract with countries such as Spain granting nominal permits to professionals in the private sector who take full charge and responsibility, and others such as Italy keeping archaeologists in the Soprintendenza (the department in charge within the Ministry of Culture) in charge of direction while interventions are conducted by a third party—normally a company or cooperative.

Policies such as the “polluter pays principle” (which can be tracked to the nineteenth century [Fressoz Reference Fressoz2013]) are commonly used in most countries, mandating a source of funding for the work. This model, however, which has become common practice across the world, raises other issues. One of the main complaints is the inability to conduct research beyond basic documentation with the funds allocated in this process. Laurent Olivier (Reference Olivier and Resco2016) provides one of the best examples with an engaging story—apparently real—about the counsel of an African warlord for the negotiations to make construction companies pay for excavations in areas of risk during the shaping of the French model. What was seen as a victory, at the time, became the “lost battle” in France, allowing any intervention with little space for mitigation beyond preventive work. Lebanon and Israel have an apparently well-settled infrastructure, but archaeology in Portugal, Spain, and Italy—where research is secondary and the labor market weak—has become another bureaucratic step for developers (for Spain, Díaz del Río Reference Díaz del Río and López2000; Parga-Dans et al. Reference Parga-Dans, Barreiro and Varela-Poussa2016). North Africa still has a long way to go because it is able to protect only previously known sites, and it has a research-focused agenda in place that offers little space for prevention outside urban areas. That is also the case of Turkey. With an increasingly nationalized model, preventive and rescue archaeology are mainly practiced with limitations in the vicinity of major cities and some of the big development projects. The situation in the Balkans is even more complicated. A view on Albania can be found in this issue (Bejko Reference Bejko2020), but the difficulties of working in postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina include an open administrative conflict in which the National Museum itself is still in legal limbo after not being mentioned in the peace agreement. Montenegro is in the process of approving the basic legislative documents for the management of archaeological heritage while trying to simultaneously enact that management. Greece struggles to intervene in all the situations needed. Archaeologists from the Ministry of Culture are overwhelmed with bureaucracy, and although they can apply for two months off every year for research, they can hardly meet daily schedules and are forced to start outsourcing some interventions. And in Cyprus, the whole process of AHM, including museums, lies in the hands of a couple dozen overworked professionals in a diminished Department of Antiquities. That it is housed in the Ministry of Transport, Communications, and Works is also a rare and notable characteristic. Whereas most countries have a Ministry of Culture—or similar—hosting the equivalent to a Department of Antiquities, Cyprus represents a unique reality in the Mediterranean. Even though this might seem to ease the planning process and mitigation, it diminishes the strength of the Department of Antiquities and sometimes biases planning decisions in favor of the developers. This calls into question not the independence but primarily the power of the Department of Antiquities within the scheme.

The lack of human and economic resources in place appears to be the primary problem in the management of archaeological heritage in most of the countries of the Mediterranean Basin. Trying to handle the most urgent daily matters is usually enough to keep everybody busy. In this sense, creative mitigation is a way to make the process easier for all. As we will see below, it is paradoxical that the little space given to creativity by the constraints of a set of management models always in crisis is sometimes the best scenario in which to become creative. If, however, archaeological sites are receiving a great deal of attention generally, public outreach is a different story.

Approaches to Mitigation: The Sites

Almost every country in the Mediterranean Basin has a procedure to intervene in the event of major developments, such as infrastructure projects. The construction of roads, pipelines, or even new fiber optic lines in cities usually requires an archaeological intervention. That is not always the case with small developments such as houses or agricultural interventions, which can happen without the knowledge of the authorities and therefore impact archaeology.

When examining the effectiveness of a management model during the interviews, doubts appear in the majority of the countries, leading sometimes to the identification of real problems in controlling the situation. Illegal building and construction projects, as well as legitimate projects that are not communicated to the relevant authorities, are probably the main reason for archaeological loss in the Mediterranean. If we consider that saving by record usually means the publication of the archaeological work in the technical literature, the situation is even worse. Still, the existence of a procedure to intervene, at least on some occasions, is a silver lining.

To compare it to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act in the United States, the EIA rules set within the European Union include cultural heritage as one of the elements to evaluate within the planning process. A similar approach has been taken by most countries in the region, although the capacity differs in each country. In a standard process, the first step is evaluation of the project and the properties affected, including the completion of surveys where the area is not already documented. In the likely event of finding any remains (the Mediterranean Basin has a very high density of archaeological sites), an initial mitigation process starts. The common or standard solution: modification of the development project or (more likely) excavation. Furthermore, in many countries, there is a monitoring of construction to avoid negative impacts on other unknown sites.

In addition, once excavated, the fate of an archaeological site can be far from ideal, especially when the power of the department in charge of AHM has little influence within the wider government. Every year, many cases of destruction can be followed in the media across the Mediterranean (for recent examples, see Fox Reference Fox2019; Tondo Reference Tondo2019). Some grassroots movements emerge eventually from civic or professional circles in relation to major discoveries, typically in urban contexts (for example, a long history in Cordoba, Spain [Vaquerizo Reference Vaquerizo2018], or the last petition in Thessaloniki, GreeceFootnote 1). One of the limitations of the application of those models with weak implementation of preventive archaeology is the fact that most projects move ahead, and archaeology usually happens in the context of rescue more than avoidance. The official discourse from the competent administrations tries, however, to highlight those small examples where projects were modified or other preventive actions taken, although the majority of the interventions happen with ongoing earthworks and, in many cases, under precarious conditions. We lack statistical data about the final decisions about the sites that have already been subject to intervention, but the options are (1) preservation in situ (open to the public, not covered but closed to public eye, or covered by the final works), (2) relocation (either opening or not opening to the public), or (3) destruction. A qualitative assessment based on the interviews conducted to date in every country is that a site rarely ends up visi(ta)ble, and more often than desired, it is destroyed to continue with the works. Of course, many exceptions apply, and urban contexts are probably the best example.

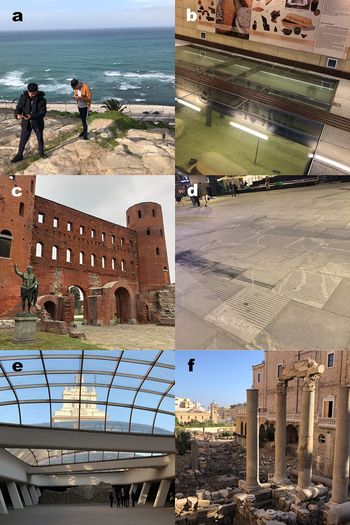

As we can see in Figure 2, there are plenty of examples of visi(ta)ble archaeological remains within many modern cities with long histories. Indeed, it is rare to encounter a city in the Mediterranean Basin with no archaeological remains that are somehow visi(ta)ble. Urban planning has become complicated, and the preservation of most of the sites we encounter every year is therefore very complicated as well. We lack proper open information on interventions in most countries, especially if we want to focus in specific areas such as cities. We can, however, talk openly about hundreds (if not thousands) of archaeological excavations happening every year in the whole region, many of them within urban areas.

FIGURE 2. Six examples of urban integration of archaeological remains: (a) a Phoenician necropolis in Tangiers, Morocco; (b) a Classical cemetery in the Metro of Athens, Greece; (c) a Roman gate in Turin, Italy; (d) an Ottoman gate in Belgrade, Serbia; (e) Roman remains in the center of Sofia, Bulgaria; (f) Roman remains in the center of Beirut, Lebanon. Photographs courtesy of the author.

Administrations have a duty by law to preserve and share what is reflected in the solutions they find to mitigate impact. Here, once again, the response of every country—even every city—varies completely. There are no fixed rules, and arbitrariness is the norm. Indeed, the interviews show complaints about this because the preference for certain types of remains may be due to political or personal issues. Professionalism is still high in the sector, however, and decisions tend to be made more by committees than individuals, at least for the most important matters.

As a result, we can see a wide range of actions taken to mitigate impact, some of which would be considered alternative—or creative—mitigation. Examples include the location of green areas on the site (sometimes referred to in the United States as “preservation in place”), even if it is not going to be open; signs in situ for reburied remains, even if they are as unclear as the one in Belgrade (Figure 2); integration of the remains in the new buildings (a surprisingly common one); avoidance and compensation to the developers (for example, allowing more building height in exchange for a reduction in the building footprint); or even the expropriation or purchase of the land, when there are resources available.

Beirut (see Figure 2) is an impressive example. In the mid-1990s, the whole center was excavated before starting with the post-civil-war reconstruction (Direction Générale des Antiquités 1996). Today, several areas somehow remain open, and they are interpreted with signage. The outcome might not look perfect, but the effort has no precedent, even in major cities such as Istanbul, Athens, and Rome (even compared to Mussolini's opening of the Via dei Fori Imperiali).

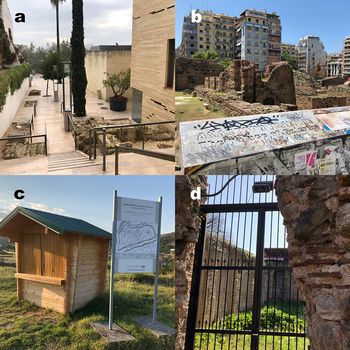

Indeed, walking around many cities where archaeology is very present leads to disappointment when one sees abandoned lots that are full of vegetation or garbage, or sites that are supposedly open to the public but mostly closed, with signs of abandonment (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Four examples of apparent abandonment of enhanced archaeological sites in urban contexts: (a) remains of walls with no interpretation in Cordoba, Spain; (b) graffiti in the Galerius Palace of Thessaloniki, Greece; (c) unguarded Doclea in Podgorica, Montenegro; (d) closed site in Küçükyali, Istanbul, Turkey. Photographs courtesy of the author.

Approaches to Mitigation: The People

Although the interviews aim to address the importance of social engagement, reality reflects a lack of outreach in most countries. The conservation of archaeological heritage is the main priority of the competent administrations, and that comes with a price. Far from supporting the complaints of archaeology as a burden for development (for example, Stamouli Reference Stamouli2018), public comments are negative when management does not consider interested parties and the general public. From delays in permits to the expropriation of private property or restrictions in the use of public spaces, the image of AHM is not always good. Furthermore, the poor conservation of many sites, or the regulation of private property use in historical centers, creates an environment of mistrust and lack of comprehension toward heritage management. Also, tourism has become a problem in many Mediterranean regions, fostering unsustainable development and raising critics of local exclusion due to gentrification. There is a feeling in many Mediterranean countries that archaeological heritage is for tourists, which causes local populations to disengage.

Although consultation with certain direct stakeholders is quite common in the Mediterranean Basin (between different departments and other administrations, with developers or other agencies, etc.), public consultation is often a mere announcement of the works (not the archaeology itself) that is usually made through official channels, with little time to comment. One important difference with respect to North American tradition is that citizens on the east side of the Atlantic Ocean are not that engaged in these processes to begin with. The identification of stakeholders is a weak pillar even on the European side of the Mediterranean, and in many cases, the public is poorly engaged in any procedure. Furthermore, the general fragmentation of the bureaucracy among different departments and administrations, along with the existing gap with society, makes communication and outreach more difficult.

When more inclusive, participative processes—such as the one recently experienced in Madrid for the remodeling of Plaza España—are put in place, the result is not always satisfactory. In this case, not only was it difficult to participate in the consultation but the process did not consider the presumed archaeological impact on an area that was known to be sensitive, which led to problems (Europa Press 2019a, 2019b). The remodeling of Plaza de Oriente in the 1980s, just a few meters away, was already controversial (Almansa-Sánchez and Corpas-Cívicos Reference Almansa-Sánchez, Corpas-Cívicos and Apaydin2020:113) due to important archaeological finds that extended toward Plaza de España. Because this information had not been kept in mind by the city council during the planning process, a rescue intervention by the regional government was needed. We as citizens expect the government to act and protect the greater good, including archaeology. Based on both the literature and the interviews, I do not know of any open archaeological heritage consulting process. Indeed, administrators fear that people might choose against the conservation of a site.

Works will always happen unless there is an important movement against them, which leaves mitigation measures to decision makers. Still, there should be a place for public participation in the process and, at least, proper communication about the actions taken and the sites involved. The reality is, again, not homogeneous and mostly disappointing.

In most countries studied, sharing information about ongoing works is forbidden or runs directly through an information office within the governmental office in charge. Unless the remains excavated are considered to be important, press releases about the works are not published. Visits to or tours of the excavation are not possible. Indeed, information is not even communicated within the work environment. Talks or open days rarely happen, and interpretive panels are usually avoided. Once the excavations have been completed, if the site is covered or destroyed, there is little information about them beyond the technical literature.

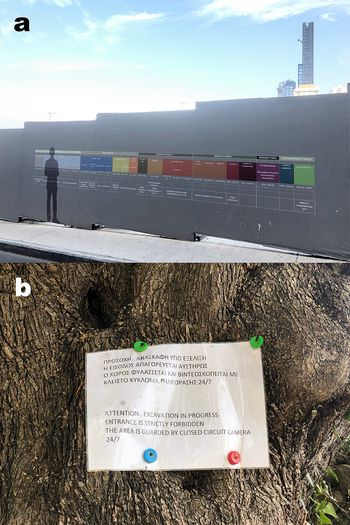

Of course, in such a large and heterogeneous territory, this pessimistic view is not always the norm. Inrap (Institut national de recherches archéologiques preventives [National Institute for Preventive Archaeology Research]), a French institution usually referred to as a good model in Europe, has many examples of engagement during works and initiatives, such as the National Days of Archaeology every summer (Journées nationales de l'archéologie). Israel has recently organized an exhibition in the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem about the works in Tell Beit Shemesh during the construction of the new highway. Madrid also organized an exhibition after—and only after—the works during the construction of the M-30 tunnels a decade ago (Rus and Domínguez Reference Rus and Domínguez2008). Although laudable, these examples are not enough, and even this way, sites fall into oblivion. As an example, informative panels, even if they are just general announcements of the works in the area, should be engaging and not exclusive. As seen in Figure 5, small, simple efforts to communicate can be appealing, whereas in other cases, the message can push people away.

FIGURE 4. The poetry of empty panels. Tombs of the Kings, Paphos, Cyprus. Photograph courtesy of the author.

FIGURE 5. When archaeology happens. Contrast: (a) fence during the works in the new Beirut History Museum, Lebanon; (b) notice before getting closer to the excavations in Nestor Palace, Greece. Photographs courtesy of the author.

New technologies can offer an alternative, making sites accessible that otherwise would be hidden. Their implementation, however, is marginal and usually concentrated in well-known monumental sites that already have a good interpretation. Some administrations have tried to offer good online tools to access archaeological sites (such as ODYSSEUS by the Greek Ministry of Culture and SportsFootnote 2), although the lack of maintenance and the rapid growth of information make it difficult to keep them current and working. To finish this section on a positive note, I would like to highlight an interesting tool provided by the City Council of Barcelona, which makes summaries and general information of all the interventions within the city available.Footnote 3 In a context where most of the information about the archaeological interventions is becoming gray literature in the best of the scenarios, these initiatives offer a good example.

SOME CRITICAL THOUGHTS TO FOSTER DISCUSSION

Lynne Sebastian (Reference Sebastian2020) discusses what “standard” and “creative” mitigation mean. Indeed, although the legal framework is quite different within the Mediterranean Basin, some basic ideas remain the same. First, “standard” often represents the “document and destroy” approach, although most legislation seems to encourage “creative” approaches that can balance the development of the works with the “rescue” of the site. Why did documentation become the basic standard practice in the process? Probably because it offered a cheap and easy solution for developers in a context where competent administrations could hardly take over the increasing number of interventions required. Indeed, those places where the “polluter pays principle” does not apply still struggle to intervene at all. There is a strict legislative framework within the Mediterranean Basin, which is often focused on traditional academic archaeology and the premise that all archaeological heritage (sometimes even the yet unknown) is public domain or a national resource to be safeguarded. In this scenario, basic documenting became a baseline above which other actions happened when possible. However, the opportunities for a creative approach to mitigation were not always in archaeologists’ hands because professionals are dependent on both the goodwill of developers (who normally are reluctant to spend money and time on archaeology, although there are many honorable exceptions) and competent administrations that, on some occasions, do not have the strength or will to take a step forward.

The overwhelming quantity and quality of archaeological heritage in the Mediterranean Basin (tens of thousands of documented archaeological sites, thousands of which are of great monumental and historical value) contrasts with an apparently lower popular interest in “real” archaeology, when compared to the other esoteric or fantastic archaeologies that are common in popular imagination (Holtorf Reference Holtorf2005). If we compare the data of the Hall report (Ramos and Duganne Reference Ramos and Duganne2000) with the last survey—for example, in Spain (MCU 2019)—we can see that in the United States, 37% of the respondents visited an archaeological site, whereas only 21.8% did so in Spain (however, we should compare these numbers carefully, given that there is a gap of almost 20 years and different methodologies). The recent European project NEARCH (http://www.nearch.eu/) offered some interesting data (Kajda et al. Reference Kajda, Marx, Wright, Richards, Marciniak, Rossenbach, Pawleta, van den Dries, Boom, Guermandi, Criado-Boado, Barreiro, Synnestvedt, Kotsakis, Kasvikis, Theodoroudi, Lüth, Issa and Frase2018) that is hopeful in this regard, such as the fact that 77% of French people thought there was not enough information about archaeology, and 62% of Greeks were disappointed with maintenance and promotion efforts.

Mitigation happens by mandate, not as a choice, and in many cases, it is the personal interest of professionals involved that brings creativity to mitigation. Indeed, the Mediterranean Basin might not be that “standard” after all. Some seemingly interesting solutions, however, can be questioned. For example, there is hidden archaeology integrated in basements across the region, but it cannot be accessed by the general public or even enjoyed by neighbors. In many historical cities throughout the Mediterranean (and beyond), it has been common practice for decades to integrate archaeological remains in the basements of new buildings (public and private). In some cases, they are somehow visible from the street, but in most cases, one needs to get into the building to see them, typically without any interpretation. This creates a problem of accessibility, but it also lacks a real connection with the neighboring communities because the remains of walls retain no meaning.

We lack available statistics, even at local levels, to compare, for example, the numbers of documented and destroyed (or covered and built-on) sites for those integrated in these new buildings or developments, preserved or at least openly revealed. But they represent a minimal percentage when one compares the number of interventions with the visi(ta)ble reality. Would it be possible to change the standards into more creative and meaningful ones? Reality might put us in a pessimistic place, but some examples gathered during the #pubarchMED project bring light, if we learn from each other and apply different policies adapted to our specific realities.

The first suggestion to consider is that we must become archaeologists again. There is a general feeling within preventive and rescue archaeology that we have become a mere bureaucratic step, and in-depth interpretive research is, in many cases, out of the picture. Competent administrations need to support this essential side of our work. That needs to be paid for, and universities either cannot or do not want to take it on. In countries such as Greece, there are policies to help with this, such as a two-month leave for public workers who need to do research. When this leave is taken, however, it is not always related to their daily work, but instead to other research projects in which they are involved. Inrap in France does a good job along these lines and has many resources available. Indeed, many administrations force practitioners to publish their preliminary results in annual volumes. This does not seem enough. Access to gray literature and additional outreach materials as well as actions are essential too. Easy and inexpensive solutions, such as outreach during excavation for construction workers or the nearby public, can be implemented, and the possibilities of new information-sharing technologies are increasing year by year. This might not only increase awareness and affect long-term acceptance of archaeological work—probably improving the current situation of distrust and fear in which many developers live—but it might also ease access for professionals and other interested parties.

A turn to the more preventive side of archaeology is also essential. Many countries are implementing extensive surveys unrelated to development works that help to update their catalogs and maps. Spain may be a good example, with many public programs in most regions for surveys or the support of smaller municipalities in the update of their catalogs (municipalities grant building licenses and represent the first firewall to protect historical and archaeological heritage within their territory).

The most important piece of the puzzle, however, is still related to on-time consultation at early stages of the projects. Although this happens often on the European side of the Mediterranean Basin, North Africa and some countries in the east still lack effective planning tools. Indeed, the outstanding preservation and monumentality of many (mainly Roman) sites in countries such as Turkey or Tunisia can represent a barrier to the implementation of preventive policies according to some interviews. This is because the governments focus on the great sites, forgetting that archaeology goes beyond monumentality. Consequently, they ignore other archaeological sites that are placed on a secondary level. Furthermore, the legacy of colonial archaeology is still present, with a strong influence of foreign missions and their interests, as well as a traditional focus on sites excavated historically by them.

The reappropriation of archaeology in most non-European (and even in some European) countries appears to be one of the underlying issues, and preventive and rescue archaeology are both an essential part of the process, facilitating the emergence of local professionals and stronger institutions for the research and management of archaeological heritage. This needs to be a progressive process with a large local investment and honest cooperation. More radical approaches have been tried, but they can have some backlash. In Turkey, it is becoming difficult to do archaeological research from abroad due to new policies originally intended to empower local archaeology. The goal should be to build a stronger local archaeology that makes foreign missions a small part of the whole (as in Spain, Italy, or Greece) while taking opportunities to benefit from the experience of the foreign missions. Lebanon and Morocco may be good examples of this approach.

To sum up, the traditions and history of Mediterranean archaeology have created an environment where mitigation is unequally present. Although many countries have extensive experience with developing creative standards that still do not seem sufficient, many others are at a very early stage of applying protective measures and standard mitigation during development works, and they have a mostly traditional academic archaeology in place.

In my opinion, there are two main factors that need to be improved in order to practice a better archaeology in which mitigation is not only effective but has a significant and positive impact. The first is the strength and power of the competent administrations. Regardless of whether the AHM model tends to be public or private, current legal frameworks are wet paper if their application is still partial, ambiguous, or arbitrary, with other powers having the final say. The second is the need for a closer relationship with the public. The gap between archaeology and society is still large, affecting all the steps in the management of archaeological heritage. Creative mitigation can help to improve relations between different agents, implement a comprehensive consultation process, and improve the protection of archaeological heritage and its positive impact on communities. Ultimately, taking advantage of the potential of creative mitigation to make archaeology great again can positively affect working conditions, social engagement, knowledge building, and heritage protection. Although many examples throughout the Mediterranean Basin can help us lead the way, they are still partial, unstructured, and mostly dependent on individuals more than institutions. Consequently, our best option to improve the situation is to learn from each other and to lobby hard for what we care about.

Acknowledgments

This project has been possible thanks to the postdoctoral contract offered by the Galician Innovation Agency (GAIN) from Xunta de Galicia. I would like to thank all the informants to date for their availability and honesty.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the research conducted on this project have not yet been fully processed. Therefore, all data are not available yet. In the coming months, raw data as well as reports and field notes will be available at the public repository of CSIC at https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/36691 under the project #pubarchMED.