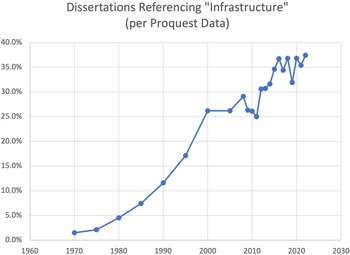

“Infrastructure” has shifted from being technocratic jargon to becoming a promising new framework for historians to understand and analyze change over time. Usage of the term has skyrocketed in the last five decades. In 1970, the word “infrastructure” appeared in 1.5 percent of history dissertations. By 2021, that number had increased to nearly 40 percent (Figure 1).Footnote 1 It is not hard to see the word's appeal. “Infrastructure” sounds rigorous, architectural, and important. For a discipline such as history, which often delves into the details of forgotten eras, infrastructure's crisp and tactile connotations can provide a gratifying contrast amid a sea of academic jargon.

Figure 1. History dissertations referencing “Infrastructure,” from ProQuest, 1970–2021.

This essay argues that the increasing use of “infrastructure” reflects more than just historians’ embrace of trendy new vocabulary; instead, infrastructure provides a powerful conceptual framework for understanding historical change and analyzing interconnections. Before making the case that the discipline of history is experiencing an “infrastructural turn,” it is worth tracking the term's growing prominence. “Infrastructure” now appears prominently in conference announcements, workshops, and symposia. H-Announce features more than 150 recent infrastructure-related events, from a symposium on educational history to a call for papers about sustainability.Footnote 2 The October 2023 issue of the journal Radical History Review will address the “Political Lives of Infrastructure.”Footnote 3 References to the term “infrastructure” in the broader historical literature have increased from less than 1 percent of articles in 1970 to more than 10 percent in 2021, as captured by the digital library JSTOR's history-related journals.Footnote 4 By contrast, terms like “government” and “diplomatic” have seen relatively little change in historians’ usage.Footnote 5

This article argues that the term's popularity reflects a shift in what historians analyze and how we conduct that analysis. An infrastructure-oriented approach allows historians to study traditional power structures like the state and the economy in ways that prioritize technology, interconnections across geographies and scales, and the materiality of the phenomena under study. As such, it provides a timely and important way to understand long-term connections, hidden power dynamics, and the durability of systems. The article proceeds first by considering the definition of infrastructure. Second, it outlines the basic components of an infrastructural analysis. Third, it considers the reasons for scholars’ recent embrace of the concept. And finally, it asks: what are the blind spots of an infrastructural approach?

Meanings: Narrow v. Expansive Infrastructure

What is infrastructure? This question has drawn attention from both scholars and policy makers in recent years. A clear sign that we should be cautious about definitions comes from the widespread appeal of the term. Who does not like infrastructure? It was the theme for a recent special issue of the left-leaning journal Jacobin and a recurring promise in Donald Trump's presidential campaign.Footnote 6 Leaders ranging from Vladimir Putin to Bernie Sanders have championed its importance.Footnote 7 Any word that can accommodate such diverse political agendas seems primed for skeptical inquiry.

When narrowly framed, infrastructure focuses on physical and technological constructions, such as roads, bridges, and communications networks. Historians have long examined infrastructure in this context, as Alfred Chandler's 1977 study of railroads and Thomas Hughes's 1983 analysis of electrification reveal.Footnote 8 These seminal works were followed by a flurry of scholarship in the 1980s and 1990s that examined large technological and built-environment projects. Monographs analyzed telecommunications systems, news networks, and air-traffic control, among other large-scale systems.Footnote 9 In these works, infrastructure described the object of study—the proper noun or phenomenon under investigation.Footnote 10 Studies of infrastructure-as-object continue to be a rich vein of historical inquiry, ranging from recent studies of the Pan-American Highway to the imperial dynamics of U.S. mining.Footnote 11

In recent years, a wide range of historians have embraced of “infrastructure,” less to describe large-scale construction projects and more to explain interconnections among phenomena. Invocations of “infrastructure” have ranged from an analysis of twentieth-century tourism networks to a study of the “ecclesiastical infrastructure” of the Habsburg Empire in the late sixteenth century.Footnote 12 Such usages show scholars' broadening of infrastructure's application beyond a single phenomenon or construction to consider the material interconnections and frameworks of cultural, political, and economic power that shaped the object of study.Footnote 13

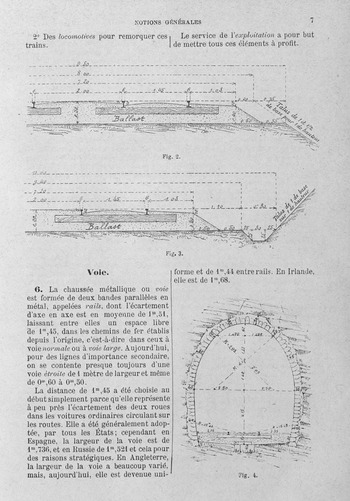

This expansion of infrastructure's usage has historical precedent: the term followed a similar trajectory in its movement from French- to English-language media in the twentieth century. The print life of “infrastructure” dates back to French engineering journals of the nineteenth century, according to historian Peter Shulman.Footnote 14 A French textbook from the late 1890s defined infrastructure as the embankments, tunnels, bridges, and viaducts necessary to establish a suitable foundation for a rail bed (see Figure 2).Footnote 15 To French engineers, the term referred not to the track work, engines, or car equipment, but rather to the supporting entities and objects that enabled a train to move.

Figure 2. “Cuttings and Tunnels,” Traité Des Chemins De Fer (1897–1898), Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The term entered English-language media several decades later, and pioneering news stories that mentioned “infrastructure” tended to comment on the term's wonkiness and foreign-ness.Footnote 16 An India-based British newspaper reported in 1950 that Winston Churchill rejected the term “infrastructure” and its usage by rival politicians: “Knowing well that there was no such word, Mr. Churchill … said he must reserve his comments till he had consulted a dictionary.”Footnote 17 U.S. newspapers adopted the term more broadly in the 1950s amid negotiations about improving NATO's military preparedness to fight communism. U.S. newspapers reported that the “horrible new term”—infrastructure—was originally a French word to describe a range of military installations.Footnote 18 Some writers described “infrastructure” as technocratic jargon designed to distract public attention from focusing on who would eventually pay for extensive defense capabilities, from supply depots to new communications lines.Footnote 19

Even as reporters expressed ambivalence about “infrastructure,” the term caught on in the 1950s and 1960s. Its vagueness likely enhanced politicians’ usage of the word: officials in the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations used “infrastructure” to describe everything from development projects in India to domestic organized crime syndicates.Footnote 20 The term began to replace “civil works” and “public works” to describe first order-phenomena such as dams and sewage systems. It also became popular to denote a broad range of political and social structures—“the things that make structures work,” analogous to the bridges and embankments that undergirded French rail networks.Footnote 21

Its jump to historical scholarship lagged by several decades, but “infrastructure” became increasingly popular among historians in the late 1970s and 1980s. More recently, historians have used the term to characterize relationships among interrelated actors, forces, and institutions.Footnote 22 Its appeal to historians is, in many ways, unsurprising, given the field's longstanding interest in how structure affects history.Footnote 23 But what does “infrastructure” offer that structure did not previously enable? What good is a term that promises to look infra—“below,” or more foundational than structure itself? Thus far, historians have not critically analyzed the term in great depth, but sociologists and urbanists have written extensively about infrastructure as a conceptual framework and form of governance. Drawing on their work can illuminate historians’ usage of the term.

Infrastructure has been a particularly formative concept in economic sociology, where scholars have applied infrastructural approaches to understanding capitalism and the data-oriented, financialized dimensions of modern life.Footnote 24 Economic sociologists have long been interested in understanding economic activities within the context of social and political relations.Footnote 25 Particularly since the 1990s and 2000s, the “social studies of finance” have tended to combine two central threads.Footnote 26 First, the field tends to embed economic forces within social and political constructs—a tradition associated with Karl Polanyi and classical economic sociology. Second, the scholarship emphasizes the materiality of technologies, hardwiring, and physical structures that shape the development of political economy and social relations.Footnote 27 This scholarship has aligned with growing interest in understanding finance, its hardwiring, and its increasingly conspicuous role in modern society.

The rise of economic sociology has accompanied a related movement in U.S. and global history to explore the origins and variations of capitalism.Footnote 28 Indeed, some of the most robust uses of infrastructural approaches in historical scholarship have appeared in studies of political economy, finance, and capitalism. Infrastructure provides an intuitive way to emphasize that markets are not timeless, inevitable byproducts of human culture, but are instead conglomerations of material constructions, technologies, laws, labor dynamics, and social relationships.Footnote 29 Recent works in this vein include Destin Jenkins's analysis of how the postwar municipal bond market contributed to racial inequality and urban disparities in San Francisco.Footnote 30 Another infrastructurally minded study examines how New Englanders supported the “plantation infrastructure” of West Indies enslavement in the eighteenth century.Footnote 31 In these works, infrastructures establish the “conditions of possibility” for how people behave and how events transpire within them.Footnote 32 As such, infrastructures exert power: they shape the choices available to participants. Moreover, they do so without overtly exerting pressure or coercion.Footnote 33

A signature feature of infrastructures is their invisibility or hiddenness: infrastructures are often subterranean, obscured, or taken for granted by people who operate within them.Footnote 34 That obscurity makes them a rich subject for inquiry after all, historians have long been interested in revealing underappreciated connections, dynamics, and actors as drivers of change. “Infrastructures remain below the visible surface of transactions, yet produce ‘world-ordering arrangements,’” notes sociologist David Pinzur.Footnote 35 Architecture scholar Keller Easterling calls infrastructure the “hidden substrate”—the space where the rules of everyday life are set.Footnote 36 In a world where the average U.S. adult checks a smartphone 344 times per day, it is little surprise that contemporary historians are primed to appreciate infrastructures of information, technology, and communications as structuring forces of change over time.Footnote 37

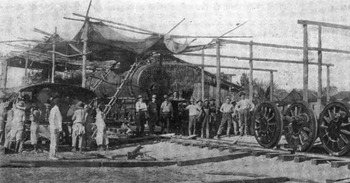

Importantly, infrastructure also raises questions about sovereignty and state power. Traditionally, U.S. historians’ engagement with infrastructure has been clustered around two main time periods: first, the expansion of U.S. empire in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; and second, New Deal–era construction and public works initiatives. In both periods, state power constituted a primary force of historical change. In the context of imperial history, scholars have drawn our attention to the way in which infrastructure building strengthened the state—both in the U.S. West and in overseas imperial expansion.Footnote 38 Infrastructure building offered a means to control populations, such as by organizing foreign workers and foreign landscapes, as well as to partner with private corporations, as in the construction of rail networks in the Philippines, for example (see Figure 3).Footnote 39 Meanwhile, New Deal historians have drawn attention to the role of the state in large-scale changes of land—and its associated legal and labor-related upheavals—from hydropower to road paving initiatives.Footnote 40 The attention to state power is more than just an accidental feature of these historical moments; instead, infrastructure inherently raises questions about large-scale investments, laws, and enforcement systems that shape people's lives—questions central to state sovereignty.Footnote 41

Figure 3. Workers grading land for construction of Philippine railway. From “Philippine Railroad Building with Filipino Builders,” The Railroad Gazette 43, no. 11 (Sept 13 1907): 299, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433057089660.

A recurring debate within the discipline of history involves how historians balance state versus nonstate power: do historians need to widen their frame beyond the nation-state to include diverse nonstate actors, or is it time to “bring the state back in?” One iteration of this debate occurred several decades ago by questioning whether politics should be the top priority of historical analysis.Footnote 42 More recently, scholars of U.S. foreign relations have debated the primacy of state versus nonstate actors, following several historians’ calls to recenter the U.S. state and domestic policy making in analyzing the nation's role in twentieth-century geopolitics.Footnote 43

Infrastructure offers a useful way to bypass the debate about state versus nonstate power because an infrastructural approach allows a scholar to calibrate the importance of each based on the phenomenon under study. Infrastructure studies tend to emphasize financial power dynamics, regulatory authorities, and the central role of government actors, while also loosening the analytical framing to allow for extrastate forces that impact the phenomena at hand.Footnote 44 In this approach, the state remains a central actor; nonetheless, infrastructure studies make space for other actors, institutions, and material forces to play a similarly pivotal role. Indeed, infrastructural approaches provide a way for scholars to adjust their emphasis on state versus nonstate factors, based on the relative importance of each in creating the assemblage under study.

Likewise, infrastructure studies offer a new vantage on another longstanding debate among historians: the question of history-from-below versus histories of elite power. Throughout the twentieth century, various scholars have called for amplifying the voices of disenfranchised groups—voices that are often erased or elided in traditional archives and colonial structures.Footnote 45 More recently, several historians have called for re-energizing “history from below” in a postcolonial, digital era by highlighting the construction of racial difference and inequality.Footnote 46

Infrastructure studies offer an alternative to the binary division between history-from-below versus studies of elite power. An infrastructural approach attunes scholars to the middle layers and substrates wherein technology, material, regulation, and labor interact. Its attention to in-between spaces—history in the middle—can help reveal the large-scale impacts of small, day-to-day processes, such as the accumulation of capital, the building of coalitions, and the diffusion of ideas and technologies. Infrastructures create the space for racial, social, and economic inequalities to grow and become enduring. For example, as Destin Jenkins's work has shown, the borrowing practices for building municipal infrastructure shaped the way in which low-income groups and communities of color were excluded from the benefits of San Francisco's economic growth.Footnote 47 This analysis demonstrates what an infrastructural approach offers that earlier generations of scholarship might have overlooked. While previous scholars have shown patterns of segregation and fracturing in modern cities, Jenkins's usage of infrastructure-as-methodology connects urban splintering to the history of investing practices that enabled certain visions of the city's future to take shape over others.Footnote 48 Infrastructure offers a theoretical framing for understanding how structural inequalities—particularly racial inequality, gender inequities, and economic disparities—have emerged, evolved, and become enduring over time.

Another feature of infrastructure-based approaches is to challenge the chronological organization of traditional histories, which are often defined by elections, wars, and economic crises. Rather than focus on “punctuating events,” infrastructure-oriented studies look beyond “the binaries of wars and the chest-beating Westphalian sovereignty of nations,” according to Easterling.Footnote 49 One potential risk of this reordering is to obscure moments of rupture. As Patrick Joyce advises readers in his infrastructure history of London, “Readers may find a certain lack of ‘conflict’ in the book.”Footnote 50 His study of infrastructure—the “political economy of the sewer and pipe”—is not without resistance, oppression, and change, he notes.Footnote 51 Instead, resistance manifests in unexpected ways, rather than in explicit debates about politics.

Historians’ recent uptake of infrastructural approaches has shed light on the middle layers of social relations and often unseen systems of knowledge and power. Studies have examined bookkeeping systems of Gilded Age commerce, messenger boys’ labor networks, and the transmission of railroad engineering expertise, among other themes.Footnote 52 Such studies focus on actors and operating systems that might escape notice in either top-down or bottom-up approaches. Such history-from-the-middle is less about analyzing specific events and more about revealing the structuring forces that have enabled wars, elections, and other traditional “punctuating” moments. As such, an infrastructural approach can examine elite power and systems, while also considering how those systems interacted with marginalized groups.

Components: Building Blocks of an Infrastructural Approach

Rather than providing a rigid template for infrastructure-as-methodology, this section identifies several core features of infrastructurally oriented scholarship. Its goal is to differentiate an infrastructural approach from other methods, as well as to provide a foundation for improving the approach. First, infrastructure-based analyses tend to foreground materiality, information, and technology within larger systems of power relations.Footnote 53 Historians have long examined material networks, so this interest does not distinguish infrastructural analysis as unique. However, the foregrounding of such considerations raises an open question for the field: is materiality a prerequisite for infrastructural studies? Is it necessary for infrastructurally-minded scholarship to emphasize the tactile dimensions of an operating system? Narrow insistence on materiality—a strict constructionist approach to infrastructure—evokes recent U.S. Congressional debates about federal infrastructure spending. Some politicians supported a narrow interpretation of infrastructure, which confined its definition to public works such as highways and ports and excluded programs like childcare or green energy.Footnote 54 Others advocated a more expansive conceptualization that would allow infrastructure funding to improve family care and electronic vehicles, among other priorities.

More useful than establishing narrow, materialist parameters for infrastructure is to adopt a function-oriented approach. Such an approach encourages scholars to map interconnections across different scales, actors, and media to understand how these pieces function as part of a coherent system. Vanessa Ogle's recent “Global Capitalist Infrastructure and U.S. Power” is a useful example.Footnote 55 The essay describes an overlapping set of treaties, bilateral agreements, regulatory systems, and business practices that governed economic development in the postwar era. Ogle's essay references material objects such as tin and rubber, as well as gold reserves; however, the argument has less to do with the built environment or tactile objects and more to do with an interplay of institutions, laws, and understandings. Ogle's work exemplifies the way in which infrastructural approaches help explain late-twentieth-century capitalism by appreciating its reliance on national laws, business customs, and multinational treaties. In this context, infrastructure represents more of a functional than a material category. Thus, even though infrastructure studies tend to emphasize materiality, focusing on the built environment or physical objects is not a prerequisite for adopting an infrastructural approach.

Second, infrastructural approaches often emphasize the latent potential or disposition of a system, which may or may not have been part of the system's original design. A disposition describes the “character or propensity of an organization that results from all its activity,” notes Easterling.Footnote 56 “A ball at the top of an inclined plane possesses a disposition … even without rolling down the incline, the ball is actively doing something by occupying its position.”Footnote 57 Analyzing the disposition of an infrastructure—and revealing its innate propensities—are among the most important contributions that historians can offer.

An elegant example of how historians can reveal latent dispositions of infrastructure is Stefan Link's recent study of Fordism in a global context. The monograph does not rely on infrastructure as an explicit methodology; nonetheless, Forging Global Fordism uses many of its tools. The book examines the way in which Fordist approaches took hold in the Soviet Union and Germany, as compared to the United States. The countries’ different ideological contexts and political economies enabled manufacturing systems that carried different dispositions in each nation. In its original form, Michigan-based Fordism contained a strong Midwestern populist bent; however, when applied overseas, different elements of Fordism could be modified and recombined to support communism, fascism, or mass consumption.Footnote 58 Link's attention to the different dispositions of Fordism reveals the way in which infrastructures can support different political agendas and enable markedly different outcomes.

Finally, infrastructure studies expose power dynamics that are often hidden from superficial analysis. Infrastructures “act like laws,” notes Paul Edwards. “They create both opportunities and limits; they promote some interests at the expense of others.”Footnote 59 Infrastructures do not need to initiate wars, sign treaties, or move money to do so. Instead, their very existence shapes a landscape of possibility that benefits some and imposes limitations on others. As such, infrastructures exert power by changing “the range of choices open to others, without apparently putting pressure directly on them to take one decision or to make one choice rather than other.”Footnote 60 Craig Robertson's recent history of the filing cabinet exemplifies how infrastructural approaches can reveal power dynamics in unlikely places. His analysis shows that filing cabinets supported a larger “infrastructure of twentieth-century government and capitalism.”Footnote 61 Robertson highlights the gendered and hierarchical dimensions of new office technologies. The work demonstrates that power dynamics lie at the heart of an infrastructural approach, even if those dynamics remained hidden from surface-level analysis.

Racial inequality, gender dynamics, economic imbalance, and national differences are among the power relations that can emerge from an infrastructural approach. Here again, the orientation to power does not distinguish infrastructure-based studies from other scholarly approaches. However, where it prompts historians to find these relationships—in structures and the spaces beneath and between them—and how it encourages scholars to understand causation differentiates the approach from other “turns” in historical scholarship.

Causes: Scholarly Uptake

If infrastructure has been in the U.S. lexicon since the 1950s, why has its popularity spiked among historians in recent decades? What explains its conspicuous presence—and utility—for today's historians? I argue that there are two key drivers for the increase in historians’ embrace of infrastructure: ambivalence about “globalization” and scholars’ growing reliance on internet technologies.

First, an infrastructural approach complicates an understanding of globalization based on “flows.” It does so by offering a systematic way to analyze cross-border, multinational connections while also emphasizing the material challenges and work required to maintain such connections. Its insistence on materiality and structure avoids some of the pitfalls of globalization analyses of the 1990s and 2000s. Scholarship from this era often referred to global “flows” to characterize the movement of people, money, goods, technologies, diseases, and other forces, but the works offered few formal guidelines for understanding the limits of mobility and interconnection. In a 1995 essay, Michael Geyer and Charles Bright issued a call to understand world history in an “age of globality.” Such history needed to recover “the multiplicity of the world's pasts … because, in a global age, the world's pasts are all simultaneously present, colliding, interacting, and intermixing.”Footnote 62 Themes such as migration, diasporas, capital flows, technology transfers, and imperial interconnection became major preoccupations in this generation of globalization 1.0 studies.Footnote 63

“Flows” were a leitmotif of this historical scholarship, even though the literature was more than a simplistic assertion that “the world is flat.” Scholars often noted that “flows” often perpetuated conflict, inequality, and resistance.Footnote 64 Nonetheless, the scholarship tended to emphasize interconnection and contact.Footnote 65 More recently, this framing of globalization-as-flows has encountered pushback. Critics have argued that the approach overlooked the friction of global interconnection, as well as the racism, ecological destruction, and North–South power imbalances that it often perpetuated.Footnote 66 “Infrastructure” provides a second-generation approach for understanding interconnection without overlooking structural inequality, stasis, friction, and unevenness.

Another less-studied driver for the recent uptake of infrastructure is the internet itself—the medium by which historians increasingly conduct research, encounter historical actors, and build communities. We can appreciate how information technology affects our perspectives as historians through an analogy to commodities trading of the late nineteenth century. Sociologist David Pinzur has compared the operation of two U.S. commodities exchanges: the Chicago Board of Trade and the New Orleans Cotton Exchange. Pinzur demonstrates that the Illinois- and Louisiana-based exchanges had different information infrastructures. In Chicago, prices were gathered centrally and distributed widely. The New Orleans exchange, by contrast, distributed prices unreliably and unevenly. These different infrastructures—the protocols and telegraph technologies by which traders received price and crop information—shaped the character, prestige, and functioning of each exchange, as well as the perspectives of traders who operated within each system.Footnote 67 Chicago-based traders tended to denounce claims that their activities were speculative, because they understood the futures market to be tethered to the spot market for real, material goods. Meanwhile, New Orleans traders tended to see the futures market as a risky but necessary counterbalance against the inherent volatility of commodities trading. As Pinzur shows, the different information ecosystems shaped how traders understood their work.

Should not this insight—that information ecosystems shape the views of those operating within them—also apply to us, as historians in the 2020s? Fifty years ago, historians conducted research in a different information infrastructure—one defined by large-scale, physical archives and print sources. Accessing records about the U.S. government, for example, typically has required historians to visit campuses of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), where we use its finding aids and consult NARA staff to locate documents. This reliance on NARA puts historians in direct contact with the institutional power of the U.S. government, in addition to heightening our awareness of its limits. The sprawling building in College Park, Maryland; and the atrium cafeteria showcase its $425 million annual operating budget and the state power required to maintain it.Footnote 68 Likewise, obsolete finding aids, staffing shortages, and limited digitization highlight our awareness of the institution's constraints. In both cases, the institution-ness of NARA shapes historians’ research context.

Today, a growing share of historians’ information infrastructure is digital. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, scholars had embraced online platforms, from HathiTrust to JSTOR, as vital research tools. During pandemic lockdowns, these tools became lifelines for historical research. Recently, academics have engaged in vibrant and important debates about digitization—such as the decline of print sources, new manifestations of inequality, the rise of digital humanities, the existential crises of traditional libraries and archives, and other such issues.Footnote 69 A related, and less explored angle of digitization involves the connection between historians’ information technologies—where and how our research takes place—and the types of questions that we ask.

Accessing documents through HathiTrust, Google, and other major databases immerses historians in a different research ecosystem than that of traditional archival research. Digital research recasts the centrality of brick-and-mortar archives, the visibility of human labor, and the materiality of books as physical objects. Sometimes, online searches yield surprises—small perforations in the digital veil that hides most of the human labor of internet research. A ripped page, the shadow of a paper clip, or perhaps a rogue finger of the person scanning might serve as reminders of traditional archiving practices and brick-and-mortar institutions (see Figure 4).Footnote 70 But for the most part, evidence of the research infrastructure asserts itself in terms of bandwidth, software tools, and wifi signal strength. In this world, the traditional institutions that held archival sources—such as state and municipal governments, presidential archives, and corporations—are less imposing features than the infrastructures that transmit their data and the communications networks that grant us access.

Figure 4. Finger in Google Books scan.

Source: Charles K. Wead, James Bryce, and Milton Updegraff, Simon Newcomb: Memorial Addresses, vol. 25 (Washington, 1910). https://www.google.com/books/edition/Simon_Newcomb/1QtBAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

As I developed this article, subcontractors working for Google Fiber cut trenches in front of my house and throughout my neighborhood. The workers—armed with cement mixers, trenchers, and backhoes—slipped small orange tubes into shallow tracks that had been cut into our street by excavators (see Figure 5). Afterward, more workers came behind with trucks that “blew” fiber through our neighborhood.Footnote 71 As the micro-trenching machines carved the narrow grooves into our street, I immediately wondered whether my research would be faster. Doesn't it follow that, in this digital information environment, we as historians see infrastructure in our firmament? Doesn't it follow that 40 percent of history dissertations would reference infrastructure?

Figure 5. Google Fiber casing, author's image (2022).

Blind Spots: What Is Obscured?

An infrastructure-based approach allows historians to fuse materiality, state power, technology, culture, global interconnection, and information systems—to mention just a few features—into the same conceptual framework. It enables historians to see change from below and above by focusing on what happens in the middle layers. It neither rejects nor reifies the power of the state. In this framing, the “infrastructural turn” sounds like a Goldilocks of historical methodologies. However, what does it obscure? Being thoughtful about embracing the approach requires recognizing its blind spots.

Infrastructure pioneers such as Joyce and Easterling have already identified a potential shortcoming: infrastructure studies tend to subvert traditional chronologies by de-prioritizing war, rupture, natural disasters, and other sudden changes. A “history of things that do not happen” will focus less on a monumental election, for example, than on the informational apparatus, electoral framework, and fundraising networks that enabled the election. Nonetheless, bringing an infrastructural approach to traditional “punctuating events” can still offer new insights on major ruptures and defining events. For example, in terms of analyzing war, Nicholas Lambert's Planning Armageddon helps us re-understand the great-power conflict of World War I through the lens of shipping, commodities trading, and material, financial, and political infrastructures.Footnote 72 Earl Hess's recent Civil War Supply and Strategy re-examines the Civil War through the lens of logistics and supply chain analysis.Footnote 73 In other words, infrastructure studies are not necessarily bad at war and rupture; they just take a different tack on traditional approaches to military conflict and armed resistance.

In fact, there is a long history of resistance movements that have recognized the importance of infrastructure by trying to destroy it. Oil pipelines have been the target of insurgent attacks on multiple continents, from the Palestinian resistance against the British Mandate in the 1930s to Nigerian activists challenging multinational oil corporations in the 2000s.Footnote 74 Even the most timeless of infrastructures—time itself—has been the target of suspected insurgent activity. In 1894, anarchist Martian Bourdin took explosives to Greenwich Park in London. In that park, the gate clock of the Royal Observatory displayed Greenwich Mean Time. Some historians have speculated that Bourdin's target was neither the park nor the observatory, but rather the clock itself, as an effort to reject centralized control over time.Footnote 75 An infrastructural approach to resistance would involve examining both the formation of resistance movements, as well as the material, legal, political, and cultural frameworks that made the infrastructure a worthy target in the first place.

Perhaps the greatest oversight of an infrastructural approach relates to its disinterest in the sensations and lived experiences of the people it affects. An infrastructural approach does not prioritize the texture of exploitation experienced by enslaved African women in the U.S. South in the early nineteenth century. Nor does it capture the ties of loyalty and the nuances in the relationships of a French family across three centuries, as does Emma Rothschild's recent An Infinite History: The Story of a Family in France over Three Centuries.Footnote 76 Nonetheless, infrastructure does not preclude such attention. In fact, the approach might enlighten the lived experiences of categories of workers, buyers, traders, and builders that traditional histories have overlooked. For example, Peter Hudson's 2017 Bankers and Empire considers the financial infrastructure of U.S. imperial power in the Caribbean through the lens of U.S. banking. His attention to middle managers and “rogue bankers” in U.S. branches overseas highlights the biographies of financiers that have gone overlooked in studies of the “great white men” of finance.Footnote 77 Likewise, recent scholarship on mining, engineering, and geology has shed light on the lived experiences of a middle layer of transnational expert-technocrats who previously lurked in scholarly shadows.Footnote 78

An infrastructural approach might not tell us much about memory, taste, or the experience of incarceration, for example, but it can provide new insights about the assemblage of investments, political alliances, and preconditions that shaped those lived experiences. Future generations of historians will undoubtedly have more to offer on infrastructure's blind spots, but in the meantime, the field has much to gain from the insights of infrastructure-oriented analysis.

As infrastructure continues to influence the work of emerging scholars, future studies could push its insights farther by investigating several key themes. One major question for the field is: what happens when infrastructures collide? Thus far, historians’ analyses have tended to focus on individual infrastructures—from commodities exchanges to Habsburg ecclesiastical networks. Analyzing infrastructures in conflict could go a long way toward explaining why some systems prevail over others and what shapes great-power conflicts. Scholarship analyzing the infrastructural encounters between multinational capitalism and Chinese economic development, for example, could help reveal why some infrastructures succeed and others capitulate. Relatedly, why do some infrastructures expand to subsume others? Additional research could clarify how a new system such as Amazon.com not only subverted traditional book publishing but became “critical infrastructure” in computing, national security, and even healthcare.Footnote 79 Studying infrastructural encounters and “imperial” infrastructural rivalry could reveal the relative importance of state power, economic forces, and ideologies—among other factors—in affecting the durability of a system.

Another frontier in infrastructure studies involves surprise, creativity, and innovation. It is easy to overstate the power of an infrastructure to determine outcomes, but what about the converse? Are there ecosystems that are particularly nimble at generating rupture or changing themselves? Are there infrastructures that support people's agency, even when individuals challenge traditional hierarchies? The tension between coercion and liberty has long been a feature of U.S. history.Footnote 80 Future scholarship could explore whether infrastructures inherently exert control, or if infrastructures could enable different forms of liberation.

Infrastructure studies also provide a way to focus scholars’ attention on the environment, landscape, and ecology, not as one-off considerations but as integral features of the phenomenon under study. In an era when climate change has become a daily news item, it is unsurprising that historians’ attention to the environment and to the impacts of large-scale technological assemblages has intensified. Historically, environmental analyses were often siloed within free-standing white papers, news stories, or scholarly studies. Such practices reinforced a common economic practice to understand environmental impacts as “externalities” divorced from the core project itself. Infrastructurally minded history offers a way to fuse considerations about the built environment, ecology, and landscape as enmeshed with the power dynamics and history of a phenomenon under study. This method can help historians who traditionally have not self-identified as environmental scholars imbue their analysis with greater ecological awareness and understandings of sustainability.

Scholars could also go farther to interrogate the politics of visibility in infrastructure. Whether an infrastructure is noticeable often depends on how functional that infrastructure is. For example, societies commonly take for granted infrastructures that operate smoothly, consistently, and discretely, such as sanitation systems or electrical grids in affluent communities. By contrast, these same infrastructures become more obtrusive in developing countries plagued by blackouts and water scarcity. The visibility of infrastructures is related to global income inequalities and has implications for the politics they inspire.Footnote 81 Different conceptualizations of infrastructure could expand how scholars understand their evolution and staying power. How does the hiddenness or visibility of an infrastructure affect building coalitions and mobilizing resistance, for example?

Infrastructure resistance is itself is another topic worthy of greater scholarly exploration. Episodes of infrastructure sabotage have a long and vibrant history, but more nuanced forms of insurgency warrant greater study. After all, infrastructural power does not always lend itself to overt sabotage. Easterling has suggested that today's activists should embrace a more diverse and eclectic portfolio of techniques to challenge modern infrastructures—techniques such as “mimicry, comedy, remote control, meaninglessness, misdirection, distraction, hacking, or entrepreneurialism.”Footnote 82 Likewise, infrastructural analyses of resistance could extend beyond overt moments of standoff and instead consider more nuanced strategies of opposition. Rather than focusing on “weapons of the weak,” infrastructure studies might showcase insurgency in the interstices—or mutiny on the mezzanine.Footnote 83 Historians can shed light on the varieties of resistance by analyzing power relations within infrastructures as well as case studies of such opposition.

In today's world, basic knowledge creation has become an infrastructural undertaking. Researching the human body took shape as the Human Genome Project—a $3 billion initiative that involved twenty universities worldwide and lasted thirteen years.Footnote 84 Understanding the universe has taken shape as the International Space Station, a multidecade initiative that relies on numerous treaties and has launched nine inhabited space stations. Understanding basic matter has manifest as European Council for Nuclear Research (CERN), a particle physics lab that spans national borders and connects more than 12,000 scientists from seventy countries.Footnote 85 These sprawling, resource-intensive projects remind us of the need to reinvent methodologies and rethink traditional models of institutional power.

As we move farther into an infrastructural era of knowledge creation, historians are increasingly using today's analytical tools and questions to understand our shared past. This movement is timely and important. And it has more ground to cover. Embracing an infrastructural approach can help historians stay nimble in analyzing behemoth institutions and forces, from capitalism to the state. It can help us stay grounded, vivid, and tactile in analyzing the role of epistemologies, technology, and environmental change. Future scholars will undoubtedly have more to say on the blind spots of an infrastructural approach. But in the meantime, the field has urgent progress to make. An added benefit is that infrastructure studies emphasize durability and fixity. Given this, an infrastructural approach might finally give historians a break from “turning” and allow us to dig in.