Climate change forces us into a thicket of unknowing. It is a crisis not only of not knowing what to do, but more fundamentally of not even knowing how to comprehend the condition itself. It is a crisis, in other words, that calls at once for urgent action and urgent reflection — and both in previously unconsidered ways.

How to do the not-yet-done? How to think the not-yet-thought?

This issue of TDR is the second of a two-part series exploring climate change and performance. The first part, entitled “Peripeteia: Rehearsing Against the End of the World,” focused on the idea of tipping points: of weather, of politics, of aesthetics, of survival. This part we are calling “Performing Against the Catastrophe.” Where the previous issue contemplated the turn, this one contemplates the collapse. Where the previous issue included full-length journal articles, a manifesto, a performance review, and artists’ pages, this issue widens the circle further by asking contributors to share brief, provocative essays in the style of a forum. Contributors include academics, activists, and artists from a wide range of fields, united by a common sense of urgency and passion to understand and transform a runaway process: a process at once global, regional, and intensely personal, and one in which the least responsible often bear the heaviest blows while the worst culprits find new ways to capitalize on the chaos they helped create.

“Peripeteia,” of course, is one of the key terms of Aristotle’s Poetics, and a cornerstone of Western dramaturgy. So too, it might seem, is “catastrophe.” Stemming from the Greek roots kata (down) and strophien (turn), catastrophe has long been understood as peripeteia’s subsequent chapter in the arc of a well-structured tragedy.

The word does not appear, however, in the Poetics. The words in that text often translated as “catastrophe” are actually metabasis (crossing over) and metabole (change). While Aristotle does use the term, briefly, in the physics section of his Problems, it has a meaning there that few would recognize from the later tradition: he uses it to refer to “the return of a string to its axial position” (Eliassen Reference Eliassen, Meiner and Veel2012:38). In short, “catastrophe” seems to have had almost no terminological importance for Aristotle, and relatively little for the Greeks generally. While it occasionally appears in Aeschylus, Sophocles, Thucydides, and Herodotus, its meanings are various and usage is rare.Footnote 1

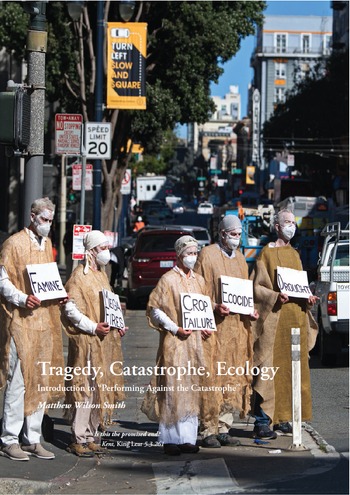

Figure 1. The Extinction Rebellion SF Bay Street Theater Group’s “Lamentors,” 15 October 2021. See “Wake Up; Look Around; Get Involved” by Daniel Larlham. (Photo by Leon Kunstenaar)

It is not until Aelius Donatus, the 4th-century CE Roman rhetorician, that the word gained systematic significance and began to be specifically associated with dramaturgy. In his Ars Grammatica, which exerted significant influence through the 18th century, Donatus divided dramatic structure into four parts: prologue, protasis (the introduction of the story), epitasis (the complication of the story), and catastrophe, which he defined as “the unravelling of the story, through which the outcome is demonstrated” (1974:308). Donatus’s use of the term informed the writings of important Renaissance critics, including the neo-Aristotelian humanist Julius Caesar Scaliger, and, in the 17th century, helped shape the thought of John Dryden and Samuel Johnson. Johnson’s Dictionary defined “catastrophe” as Donatus might, as “The change or revolution, which produces the conclusion or final event of a dramatick piece,” while adding also, as the second definition, the association of the term (not in Donatus) with sad endings: “A final event; a conclusion generally unhappy” ([1755, 1773] 2021).Footnote 2

This emplotment of the tragic structure, with its expectation of catastrophe, has by now become part of the common currency of global culture. So it is natural enough, when confronted by a phenomenon as harrowing as climate change, to employ the term, with its attendant connotations. But this is a vexed inheritance. For the lens of catastrophe brings certain aspects of global warming into clear focus while distorting others.

What it brings into focus is the urgency and horror of the situation. Whether or not some tipping point has been tipped, we are already suffering sudden collapses in the forms of fire, flood, famine, drought, plague, violence, and the mass dislocation of populations. Not to dub these global transformations “catastrophes” might seem to be either callousness or hair-splitting.

But for Donatus, “catastrophe” meant something other than disaster (though it might entail one); it is the concluding part of a larger organic structure in which the skein of the plot unraveled from beginning to end. It is, if not a matter of fate, then at least a matter of dramatic necessity. It is also an event that permits no further act in any significant sense: at most a denouement and epilogue. This sense of finality is critical to tragic emplotment as it is generally received. It is also the pagan foundation upon which the Christian narrative — which insists on adding one further, comic act to the drama — is erected.

But neither classical collapse nor messianic redemption would seem to be helpful narrative structures for today’s unfolding crisis. As a range of scholars, activists, and artists have pointed out, climate change resists representation by traditional narrative structures, or at least ones that have dominated the West. The complex causality and slow violence of global warming frustrates such simple geometries as the arc of tragedy, the circle of restoration, or the upward line of progress.

All of which suggests that we might do well to look at works, including canonical ones, that complicate catastrophe. In King Lear, Donatus’s four-part structure is undermined from the outset and throughout, as the title character begins with a catastrophe from which he never recovers; Lear does not rise and fall so much as collapse, rage, and dissolve.

This displacement of catastrophe from the end to the beginning of the drama extends beyond the character of Lear himself. We find it also, for example, in the character of Edgar, as seen through the eyes of Edmund in act 1. The bastard Edmund views Edgar’s entrance as perfectly timed for the formulation of Edmund’s villainy. “And pat he comes, like the catastrophe of the old comedy. My cue is villainous melancholy,” says Edmund to himself, viewing Edgar in secret (1.2.134–35). While Samuel Johnson used this line as his first example of his primary definition of “catastrophe,” it is actually an odd instance and rife with irony. Here Edmund pokes fun at the awkward devices of hoary dramas, in which the resolution arrives on cue, as persona ex machina. More provocatively still, this first-act entrance of “catastrophe” reinforces the play’s larger movement of catastrophe to the outset of the drama, prefiguring the play’s thoroughgoing atmosphere of collapse.

This pervasive catastrophe takes place in a landscape shaped by natural forces that exert themselves with ferocious power, most obviously in the storm that blows through the heart of the play and prompts and echoes Lear’s outpouring of rage. The critic Simon Estok writes that Nature in Lear

represents an object space that must be controlled; uncontrolled, it is a dangerous space of chaotic nothingness. If Cordelia is associated with Nature in the popular imagination that the play represents (or in Lear’s imagination), it is certainly in this sense. Conceived of with the same ideals about silence as the natural environment (and valued analogously with it), women are for Lear a potently dangerous material, a space of poison and pollution that, like the natural environment, lacks reason, is morally inconsiderable, and must be kept silent. (2011:26–27)

As feminist critics have long argued, the demonization and subjugation of women is frequently bound up with the demonization and subjugation of the natural world, perhaps nowhere more so than in cultures shaped by Abrahamic traditions.

Lear, however, urges us to reconsider such ideologies. It is a catastrophe of control: of wealth, of land, of women. It stages catastrophe not as dénouement but as condition. This catastrophic condition is neither natural nor fated, but results from a series of disastrous choices that the characters make and to which they must respond. Lear’s catastrophe, like ours, is unnecessary and, through the end of the play, unresolved.

In these ways, Lear may serve as a prologue for this issue as a whole. The essays in this issue, too, compel us to consider the place of catastrophe at a moment when our mastery over nature is being exposed as hubristic illusion. They offer not resolution but urgent questioning. They urge us to reimagine theatre’s role, and our own, in the central drama of our times.

The Structure of Our Issue

This issue consists of 20 reflections, from a wide variety of perspectives, on the relationships between performance, catastrophe, and climate change. Though lines of connection crisscross the issue, we have divided it into four parts in order to bring certain concerns to the fore. The sections are: “Names and Forms,” “Artworks and Interventions,” “Systems and Structures,” and “The Question of Mourning.”

“Names and Forms” wrestles with the question of how our current vocabularies and narrative forms fail to make sense of climate change, and what better forms might look like. Several of our writers agree that traditional dramatic genres are particularly ill-suited for the task. Genevieve Guenther writes that “[t]he formal conventions of both tragedy and comedy elide the ongoing political conflict that is causing global heating, and their aesthetic strategies inspire affects and attitudes that encourage dangerous complacency” (16). In their place, Guenther would have us follow Brecht’s lead in recovering a genre the ancients regarded as antidramatic: epic. Branislav Jakovljević agrees on the importance of moving beyond — indeed radically dismantling — traditional dramatic genres, tragedy above all. Tracing a line from Aristotle through Gustav Freytag (in the 19th century) and Vladimir Mikhailovich Volkenstein (in the 20th), Jakovljević finds this lineage “spoiled beyond repair” (26) but views the epic, too, with wariness.

The challenge of describing what a new dramatic form might look like is taken up variously by Gloria Benedikt, Wendy Arons, Una Chaudhuri, and Zlatko Paković. Noting the dual temptation to create either “tragedies and dystopian fiction” or else “works with happy endings where our problems get solved by a sudden breakthrough of technical solutions,” Benedikt rejects both approaches for one in which artists, scientists, and activists work together to “mend the gap” between science and society (30). Arons pitches her essay against the term “Anthropocene” in particular, which she dismisses in favor of “Capitalocene,” a term with “the potential to dissolve symbolic boundaries between humans and nonhumans with an argument grounded in neo-Marxist economics” (38). In the conclusion of her essay, she offers a list of 16 “Tragedies of the Capitalocene”: tragedies that move decisively past the conventions of classical form. While Arons’s essay helps us trace a new theatrical genre (perhaps the dramatic equivalent of what is becoming known, in literary circles, as cli-fi), Una Chaudhuri gives us a toolbox for current and future theatrical artists. Chaudhuri, working with other members of the group Climate Lens, offers a “playbook” of “strategies for making dis-anthropocentric performance” (42). Together, these strategies help us to think beyond dramatic structures centered on human thought and action, encouraging us instead to explore alien spaces, geographies, causalities, ontologies — vastness, the infinitesimal, the “pleated,” the “glocal” — and to “[f]orge new affective pathways to the nonhuman” (43). A similar desire emerges in Paković’s concluding essay of this section, which enjoins us to create a theatre that properly names the problem. Such a theatre must eschew two things above all: the spectacularization of climate change and the use of the topic of “environmental crisis” as a way of avoiding confrontation with its social and economic causes.

While these formal concerns run throughout the issue, our second section, “Artworks and Interventions,” focuses more sharply on specific artistic performances from a variety of cultures and locations. Chiayi Seetoo directs our attention to works by a number of East Asian artists, most prominently the director and playwright Stan Lei. Lei’s play Ago, which stages a series of natural and human-made disasters and premiered in Shanghai just before the outbreak of Covid-19, draws on the author’s practice of Vajrayana Buddhism to envision a nonanthropocentric and ecocosmopolitan dramaturgy based in interconnected networks of relations. Denise Varney and Lara Stevens are similarly drawn to performances that tease out the complex connections between the local and the global. They pay particular attention to CoalFace, a performance by Australian artists Norie Neumark and Maria Miranda. The work, which was developed out of a month-long residency in Beijing, combined brute material installation (mounds of coal on a gallery floor) with interactive digital devices to represent something almost unrepresentable: the relationship between Australian coal exports and air pollution in China.

The three subsequent essays in this section bring to light a variety of performances that seek to bring the urgency of climate change to the streets. Daniel Larlham gives a firsthand account of the nonviolent direct-action group Extinction Rebellion, with particular attention to the group’s street theatre performances in the San Francisco Bay Area. He notes that Extinction Rebellion’s membership numbers have been adversely affected by Covid — a grim irony given the fact that many of the causes of climate change also increase the risk of such pandemics — and has become “agnostic” about the future of the movement. If nothing else, however, Extinction Rebellion has inspired comparable movements such as the lecture, discussion, and performance series Burning Futures, hosted at the Hebbel am Ufer in Berlin (and, via its “digital stage,” around the world). Maximilian Hass, who cocurates the series with Margarita Tsomou, describes the ways in which it has brought artists, activists, and scholars together in dramatic dialogue and collaborative action. A similarly innovative project, under the title Common Dreams — Flotation School, was inaugurated by the Brussels-based Portuguese artist Maria Lucia Cruz Correia. This durational, collaborative, pedagogical performance project is the subject of our contribution from Christel Stalpaert, who describes how the work seeks to “activat[e] climate change awareness with the participant-spectator in a very embodied and implicated way” (74). Finally, this second section concludes with a new play by a playwright known for her work on art and climate change. Chantal Bilodeau’s Homo Sapiens is a short comedy on a long derangement.

Our third section, entitled “Systems and Structures,” highlights mass performances, large-scale institutions, and networks of everyday life. We begin with an essay by Clara Wilch that introduces infrastructure as a vital if largely hidden performative element in processes of climate change. Drawing on her work in the sub-Arctic city of Iqaluit, Wilch finds that infrastructural extraction and dumping practices create the “ecological relationships and power [that] are negotiated […] at a communal scale, for good and for ill” (89) — and that we overlook these practices at our peril. Our subsequent author, Kathleen M. Millar, certainly does not overlook such practices. Her contribution extends her earlier ethnographic work on the neighborhood of Jardim Gramacho, home to the main garbage dump of Rio de Janeiro, and the catadores who labor there. Millar is particularly interested in the catadores’ often critical, even indignant response to corporate- and state-sponsored environmental projects, projects that too often treat the catadores with paternalistic incomprehension.

Rejection of such condescension also features in our next two essays by Teena Brown Pulu and Richard Pamatatau, and by Janice Ross. With attention to the Pacific Islands and their inhabitants, Pulu and Pamatatau’s essay explicitly rejects the ways in which Pacific Islanders have too often been treated as exemplary of “nonmodern thinking.” Questioning the universal subject implied by the concept of the Anthropocene, Pulu and Pamatatau illustrate the relational entanglements of Pacific Islanders through the social media storying of the Tonga tsunami of 2021 and its aftermath. Ross’s contribution moves us across the globe to Italy, where ecomigrants often find themselves processed through Italian prisons. But in this bleak picture Ross finds rays of light, for some Italian prisons have developed innovative rehabilitation programs that stress “job training in ecominded and climate-conscious cultural industries [that] can be a powerful way for [inmates] to perform labor that resists the same exploitative models of production and consumption that are part of the causal disasters leading to climate migration” (103).

This section of our issue concludes with reflections on the two greatest carbon dioxide producers in the world today: the United States and China. Seeing the replacement of nation-states with international governance as a utopian dream, Kwai-Cheung Lo considers the productive role that rivalry between these two behemoths might play in combating climate change. Only through such interstate competition, he suggests, can such nation-states be compelled to embrace climate-friendly actions. Signs (both positive and negative) of how this climate rivalry might play out are illustrated by Ho Chak Law’s contribution. Law points us toward two recent products of the Chinese culture industry: the Beijing Olympics and the “Green Ecology” folksong. Both mass-cultural products associate “green” values with concepts of national heritage and cultural rejuvenation, offering themselves as forms of environmentalism “with Chinese characteristics.”

We end our issue with “The Question of Mourning,” an ambiguous epilogue in which two authors take up the issue of climate change and grief. In conversation with theorists Lauren Berlant, Una Chaudhuri, and Mel Chen, Sariel Golomb returns us to Freud’s concept of the death drive in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). Freud’s speculative theory, Golomb argues, is well suited to the challenge of representing the epistemic crisis and baffling illegibility of climate change — and may help us discover “a poetics of planetary grieving” (121). Taking up a similar question from a very different angle, Sugata Ray returns us to the original published image of the dodo in Amsterdam in 1600 and the subsequent eulogization of this flightless bird by numerous European writers. As perhaps the first “icon of the Anthropocene Extinction,” the doomed dodo is also a caveat against a “fetishized econostalgia for a primeval precolonial wilderness” (130) and against a certain desire to “come to terms with both the trauma of the global dispersal of Western European modernity and a future in which our own survival is under imminent threat” (131). To mourn or not to mourn? Or perhaps: how best to mourn while also refusing to mourn the catastrophe that is also not the end?

This issue as a whole marks neither an end nor a beginning and strives toward neither comprehensiveness nor totality. Our crisis eludes all such attempts. But we understand this elusiveness as a challenge to make forays of analysis and imagination. Time is not on our side and yesterday’s wisdom won’t do. It is time to begin again, again.

And so our issue begins, like all great dramas, in medias res…