This article examines a pivoting moment of Chinese modern dance history—a four-year US-China dance exchange project known as the Guangdong Modern Dance Experimental Program that occurred as part of China's Reform Era cultural policies. From 1987 to 1991, faculty associates from an intensive summer school in the United States, the American Dance Festival (ADF), at the invitation of a professional dance institution in China, the Guangdong Dance School, taught modern dance techniques and composition in Guangdong and trained the first group of professional modern dancers in China. Most of these dancers continued on and established their country's first modern dance company in 1992, the Guangdong Modern Dance Company. Examining this program as a case study, this research scrutinizes the paradoxical role that American values and ideals have played in China's self-motivated cultural reconstruction as the People's Republic of China tried to rise on the global stage. For twenty years, I have engaged with this issue as a dancer, a field-worker, and a dance scholar. I grew up in China and received extensive professional training in Chinese classical and folk danceFootnote 1 and modern dance from the country's premier dance conservatory. After arriving in the United States, I immersed myself in dancing and choreographing modern dance works and simultaneously graduated with a PhD. Familiar with both American and Chinese dance societies, I have discovered how people from both countries imagine one another and how they do not actually know what the other is thinking about them. Based on my intertwined positions of outside insider and artist-scholar, this article untangles the crossing-over conversations in US-China transnational settings, something that I have experienced in person and discovered, in my research of the Guangdong program, to defy conventional narratives of Chinese modern dance.

Drawing on my own experience as a bicultural dancer, I begin to ask if dancing itself can tell something particular about how to theorize dance and China in the West. My unique identity and position allow me not only to collect primary resources of oral history and archival research from the American and Chinese participants of the Guangdong program, but also, more importantly, to compare these transnational resources and put them into a conversation for the first time. I discover a mutual-misunderstanding-based transnational encounter that problematizes the dominant presumptions about this program as a smooth communication without “bumpy” struggles. Anthropologist Anna Tsing has theorized this equivocal interaction as “‘friction’: the award, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interaction across difference” (Reference Tsing2005, 4) that “refuses the lie that global power operates as a well-oiled machine” (6). Similar to the fact that “[a] wheel turns because of its encounter with the surface of the road; spinning in the air it goes nowhere,” friction grasps the productive moment of misunderstandings and generates co-productive cultures in global encounters (Tsing Reference Tsing2005, 4–5). With similar intention to grasp the productive historical moment when modern dance was (mis)translated from the American teachers’ bodies to the Chinese students’ bodies in the Guangdong program, this article proposes the concept of “mis-step” as an aperture to rethink corporeal encounter and dance circulation in global spaces. Revolutionary nationalism, postcolonialism, liberalism, and other grand perspectives are instrumental, but they often do so at the expense of the dancers’ sensual experiences of their bodies. “Mis-step” represents a “dancing concept” that explores how the unpredictable can lead us detouring to a place unfamiliar and exciting. This theoretical framework “mis-step” differs from the commonly used word “misstep,” which indicates predominantly negative meanings of mistakes and wrong steps. In this article, “mis” indicates contingency beyond expectations; “step” suggests productivity of that contingency. “Mis-step” thus innately highlights the rich potential of indeterminacy and proposes to theorize transnational dance history beyond “right” or “wrong.” Specifically, I conceptualize the Guangdong program as a “duet” that the American and Chinese participants performed together for four years from 1987 to 1991. In this “performance/communication act,” participants from both countries were simultaneously learning the “steps” as they were performing those “steps.” Uncertainties permeated the “dancing” process because the participants made improvised decisions based on one another's previously improvised decisions. Those spontaneous choices filled the dance with alternative steps that generated a new performance different from the original blueprint. Because the process itself demonstrated contingency on many variable factors, there was no “right step” in cross-cultural dance transmission that unfolded automatically. The American and Chinese participants could not really see the trajectory that they co-created until they finished the “duet.” Therefore, their exchange can be more productively seen as mis-steps, or steps that are wrong-as-right or right-as-wrong. This research probes the historical moment when those participants were still dancing their “duet” and did not yet know the result of their collaboration. In those moments of “forming,” mis-step produces a cross-cultural relation in which its incompleteness registers as a way of being complete.

This article follows and builds upon the recent scholarly shift in Chinese studies that criticizes the limits of revolutionary nationalism, postcolonialism, and liberalism in understanding Reform Era China (1978–). A historical condition with significant sociopolitical transitions after the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Reform Era China, or post-Mao China,Footnote 2 switched its modernization focus from the addressing of class conflict to a new set of depoliticized and economy-driven policies as well as a broad cultural opening to the Western world. Arif Dirlik introduces the concept of “postsocialism” to theorize this transition, in which China introduced “capitalist values and practices into the existing socialist structure” and endeavored to avoid both the continuity of revolutionary socialism and a complete assimilation into global capitalism (Reference Dirlik, Dirlik and Meisner1989, 374). Postsocialism refutes a lens of revolutionary nationalism in reading Reform Era China. Homogenizing the PRC's shifting ideological constructions into unified phenomena, revolutionary nationalism glosses over the plurality and ambiguity in China's dynamic changes since the 1980s. By incorporating capitalism into its existing and transforming socialist infrastructure, Reform Era China demonstrates an interesting tension with the West and with capitalism: learning from them while also refusing to turn into them. This struggle of simultaneous acceptance and rejection fosters a self-innovation dilemma that Xiaomei Chen identifies as “Occidentalism”—a discursive act “marked by a particular combination of the Western construction of China with the Chinese construction of the West” (Reference Chen1995, 5). A discourse of both oppression and liberation, Occidentalism troubles reading post-Mao China through postcolonialism, which, Chen argues, generates an either active resistance or passive acceptance binary (1995, 5–9). In this particular era, the Western imports stimulated a much more complex turmoil of becoming and unbecoming in China that far exceeded a framework of liberation and agency. Unfortunately, as Daniel Vukovich argues, it is very difficult to conceptualize post-Mao China in the West “without falling back into familiar histories and conceptual shibboleths about what freedom, individuality, human rights, and so on are” (Vukovich Reference Vukovich2019, 10). The United States and Europe constitute “an international art market eager to consume exoticism and attack the Communist state” (Zhang and Frazier Reference Zhang and Frazier2017, 581). Hentyle Yapp argues for a theoretical hesitance, a pause, from this immediate demand to capture China as fully knowable within a narrative overly determined by liberalism. Instead, he emphasizes an attention to the “minor”—the occluded, the aesthetic, and the affective—to rethink China in theory and to explore new possibilities for theoretical evaluation (Reference Yapp2021, 21).

Bringing such scholarly shift in Chinese studies to intersect with dance studies, the concept of mis-step defies the seemingly self-evident readings of dance and the modern in China. The Guangdong program does not tell a story about revolutionary nationalism in which Chinese artists uttered their own voices by using modern dance to attack communism, nor does it convey a narrative about anti-cultural imperialism in which the local Chinese artists resisted the American artists’ purposeful imposing of American values. Further, this program does not forward a story about freedom in which the American teachers successfully liberated the Chinese people through modern dance. These narratives demonstrate a result-oriented, American-centric inquiry based on how American culture influences other countries. Overemphasizing the impact-response relation polarizes positions of winner and loser, in which the United States is most often the winner. Instead, by looking at the historical moments of “mis-stepping,” I take a dancing–inspired perspective to examine the intersubjectivity in the classroom—the dance studio, a “contact zone” where “peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations” (Pratt Reference Pratt2008, 6). When the American teachers and Chinese students moved together in the studio, divergent understandings of kinesthesia, learning approaches, freedom, and the modern merged and collided. The reconciliation of divergence and incompatibility filled the entire exchange process with recurrent frictions that “made as well as unmade” hegemony (Tsing Reference Tsing2005, 6). In other words, there was no “winner” or “loser” in the dance classroom, only human beings who messed things up because of their unfamiliarity with one another. This article does not argue that profound misunderstandings occurred because of the different national dance cultures in the United States and China. Instead, this article takes different dance genres’ embodied interactions as a point of departure to discuss the productivity of contingency that is seen on the surface as historical “errors.” Mis-steps forward a sensual experience of global encounter that centers on perplexity. This awkward yet meaningful experience constructs a crucial component of globalization reality. To recognize this construction contributes to the ongoing conversations in dance studies about modern dance's global travel and relocation (e.g., Lin Reference Lin2004; Purkayastha Reference Purkayastha2014; Croft Reference Croft2015; Ma Reference Ma2016; Chen Reference Chen, Mezur and Wilcox2020; Schwall Reference Schwall2021).

In what follows, I first present a historical background of the Guangdong program, and then theorize three layers of cross-cultural friction that each fosters a historical mis-step: (1) the teachers’ and students’ differing experiences of kinesthesia based on their prior dance training; (2) their contrasting understandings of learning approaches; and (3) their divergent conceptions of the modern. To unravel the friction, it is vital to study dance in both countries as a complex system that includes training, rehearsal, and performance. English language scholarship has shown extensive literature on these dynamics of modern dance (e.g., Foster Reference Foster1986; Banes Reference Banes1987; Novack Reference Novack1990; Daly Reference Daly2002; DeFrantz Reference DeFrantz2004; Manning Reference Manning2004; Das Reference Das2017; Kowal Reference Kowal2020), but the research on dance in China mainly focuses on concert performance, or, “representative works” (Chang and Frederiksen Reference Chang and Frederiksen2016; Ma, Reference Ma2016; Wilcox Reference Wilcox2018a, Reference Wilcox2018b). To expand scholarly conversations, this article examines education and its connection to rehearsal and concert performance to scrutinize the PRC's dance ecosystem.

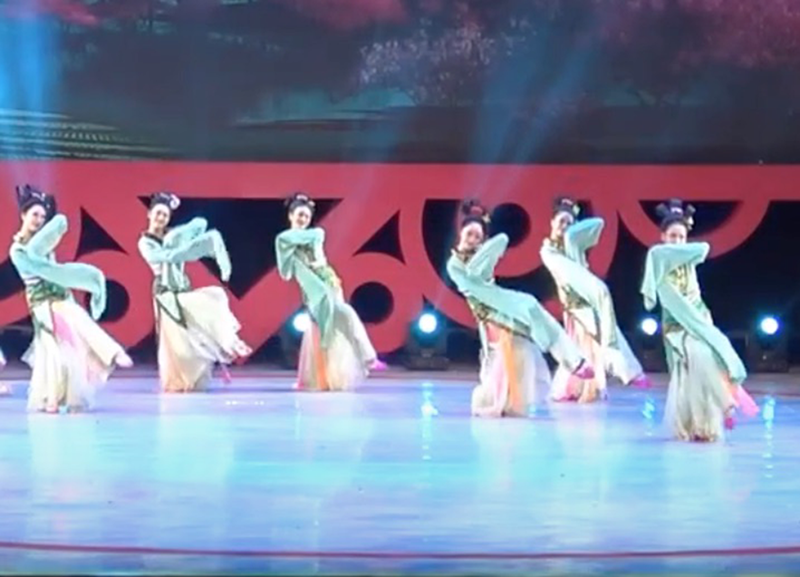

Photo 1. The ADF faculty teaching technique and composition classes in the Guangdong program. In Guangdong Modern Dance Company Fifth Year Anniversary Celebration Booklet, 1997, pp.66. Courtesy Guangdong Modern Dance Company.

The Rebirth of Modern Dance in China's Reform Era

Reform Era China witnessed a rebirth of modern dance through a phenomenon of “modern dance fever,” in which domestic dance artists enthusiastically learned modern dance from abroad and experimented with localizing this foreign dance art. Modern dance concepts first entered China in the early 1900s, when Yu Rongling, daughter of a Chinese ambassador in France, learned modern dance from its pioneer Isadora Duncan and performed in the royal court back in China (Yu Reference Yu1957). In the 1930s and 1940s, Wu Xiaobang, after studying modern dance in Japan from artists who were students of German modern dance master Mary Wigman, created a series of experimental and unconventional dances back in China, known as “New Dance” (Wu Reference Wu1979a, Reference Wu1979b). In the 1950s, Guo Mingda, a student of American modern dance artist Alwin Nikolais, returned to China and endeavored to create a modern dance major in Beijing (Liu Reference Liu2007). However, from the 1950s to the end of the 1970s, in its socialist heyday, China banned modern dance practices because of their “capitalist art” nature (Ou Reference Ou, Solomon and Solomon1995). Following China's “reform and opening up” policy and the establishment of formal diplomatic relations between the United States and the PRC in 1979, American modern dance artists and leading companies started to visit China in the 1980s.Footnote 3 Simultaneously, local Chinese modern dance precursors, such as Wu Xiaobang and Guo Mingda, resumed their careers by offering workshops nationwide. New generation Chinese dance artists, such as Hu Jialu and Hua Chao, immersed themselves in these events and zealously applied what they learned to creating new dances differing from the conventional genres. Contextualized by this vibrant domestic environment that gave rebirth to modern dance in China, Yang Meiqi, the principal of the Guangdong Dance School and a Chinese folk dance teacher, came up with the idea of the Guangdong project in 1986, when she was taking her first modern dance classes at the ADF. Amazed by its diverse styles and inspirational concepts, Yang decided to create a modern dance major in her institution to advance dance education and modernization in China (Yang Reference Yang2016). With support from Charles Reinhart, the director of the ADF, Yang returned to China and successfully persuaded local government officials to authorize the creation of the new major. In September 1987, funded by the Asian Cultural Council, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Chinese government, the Guangdong Dance School and the ADF cofounded the Guangdong program to create China's own modern dance.

The Guangdong program's four-year curriculum lengthened the six-week ADF summer program and retained its core courses of technique, improvisation, and composition. Interestingly, the faculty was composed of six white Americans and three Asian Americans who reflected various modern techniques but primarily centered on Graham and Humphrey-Limon techniques.Footnote 4 Each teacher resided in the program for two to three months and worked four to five hours a day, six days a week. With a translator, the classes usually started with a morning technique class, and then the day continued with improvisation and composition classes. As the student numbers varied around eighteen, I interviewed thirteen of them who stayed through the entire or most of the program. Between eighteen and twenty-three in age at that time, these top-tier Chinese dancers were trained in a vocational secondary school abbreviated as zhongzhuan (中专), an educational system adapted from the Soviet Union in the 1950s for producing professional performers in China.Footnote 5 A curriculum of Chinese classical dance, Chinese folk dance, and martial arts technique cultivated dancers who would then enter the majority of national and local song and dance ensembles—twelve of my thirteen interviewees had experienced this and the other one graduated from a ballet school. The Chinese students auditioned not only because of their interest in modern dance, but also because of the city where the program was located—Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province and China's “window” to the West.

Chinese dance scholars have argued that the Guangdong program's historical significance did not lie in bringing modern dance to a land where it had not existed, but rather in starting a brand-new discipline (Liu Reference Liu2004; Ou Reference Ou2008). The program engendered a self-sufficient system in which training professional dancers and staging modern dance works were all done by Chinese people themselves. Besides constituting the Guangdong Modern Dance Company in 1992, graduates from the program assisted in creating the second modern dance major in China in 1993 at the Beijing Dance Academy (BDA). Graduates from the BDA founded the Beijing Modern Dance Company in 1995, the second modern dance company in China. These two professional companies and the BDA's bachelor's degree program in the 1990s have promoted modern dance's growth across the nation in the twenty-first century.

Constructing Kinesthetic Values

A prominent discovery in my oral history and archival research is the confusing frustration that both American teachers and Chinese students experienced when teaching and learning modern dance techniques. Their interviews and written texts illustrate unsolvable troubles in communicating weight release, a kinesthetic sensation in performing modern dance techniques. Kinesthesia in my argument refers to how one feels physical movements in terms of the sensual experience of space, rhythm, force, and energy. A person's kinesthetic experiences in dancing are not merely spontaneous and random in the moment, but rather, culturally and historically constructed (Foster Reference Foster2011). The focus on kinesthesia allows me to interrogate discourses of the body from both a sensual and a sociohistorical level. As several Chinese students mentioned in my interview,

Stackhouse always told us to feel the space and create connections with the ground. Years later … I think I finally understood that she actually meant to create connections with gravity and release the weight. But when I was a student in the Guangdong program, I really could not understand what she meant by saying that. (Ma Reference Ma2016)

Modern dance is not about learning the shape of the movement, but about weight switching, relaxing the body, and dancing with gravity. But at that time, I could not understand this and I did not accomplish a break-through in my body. (Yan Reference Yan2017)

From the beginning, modern dance technique classes are different in relaxation of the body and a lot of floor work. It asks me to completely drop off what I learned in the past. (Qu Reference Qu2017)

Published interviews of American teachers and their private letters to Reinhart exhibited similar feelings during teaching:

They … [were] not really … able to release because of their classical training. They are so held. (R. Solomon and J. Solomon Reference Solomon, Solomon, Solomon and Solomon1995, 76)

The area that was least developed was weighted sense to give contrast to the lightness in their dancing … but it would take much more time for them to absorb that quality and sense it as a part of their intuitive material. (Stackhouse Reference Stackhouse, Solomon and Solomon1995, 91)

So much potential, and needs a close teacher eye to release. (Davis Reference Davis1990)

What caused the inability of Chinese students to grasp this quality of weight so emphasized by the American teachers? The reason originated from a kinesthesia in American modern dance techniques “untranslatable” to bodies trained in another dance culture—Chinese classical and folk dance. When the American teachers helped the Chinese students to embody new ways of dancing, the first layer of mis-step emerged from the interplay between the contrasting kinesthetic values developed in American and Chinese dance histories.

In the Guangdong program's modern dance technique classes, American teachers introduced a kinesthetic value that centered on the dancer's relation to gravity. Sarah Stackhouse and Lucas Hoving, who taught Humphrey-Limon technique, emphasized a continuous enactment of filling and emptying the body's resistance to the force of gravity (Stackhouse Reference Stackhouse, Solomon and Solomon1995; Hoving 1995). David Hochoy and Stuart Hodes, who taught Graham technique, directed students to experience the internal muscular tension and the accumulative energy volume whose source of power stemmed from the ground (Hochoy Reference Hochoy1991; Hodes Reference Hodes1992). Douglas Nielsen, adapting Cunningham technique and Gaga, designed complex foot work that kept students connected to the floor while experiencing the constant alternation of weight between their feet (Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Solomon and Solomon1995). Although Graham technique and Humphrey-Limon technique suggested different moving philosophies, both shared a kinesthetic value that highlighted the dynamic physical dialogue with gravity, and both spotlighted the process of motion itself rather than the creation of shapes during dancing (Foster Reference Foster2011, 113–114). In the Guangdong program, even though each American teacher presented different styles and movement vocabularies, the relation to gravity prevailed as a central emphasis in their technique classes and cultivated a dancing body whose motion emphasized that relationship.

Based on my ethnographic research, the Chinese students were trained in a different kinesthetic value before joining the Guangdong program, one that I call a “posture-oriented” dancing logic. China's dance cultural convention foregrounds performing postures and embodying temporary frozen moments. I do not mean that Chinese dancers only perform postures in their classical and folk dance. Rather, I mean that the posture-oriented kinesthetic value centralizes posturing as both a method of training and a spectatorship convention, both an approach to cultural preservation and an aesthetic principle to draw upon for cultural innovation. Traditionally titled “enduring” (hao 耗),Footnote 6 holding shapes functions as the core approach to learning embodied knowledge in Chinese performing arts. Students would stay static in one posture for minutes or even hours long to plant key corporeal “genes” into their bodies. By building up solid muscular memories, enduring cultivates the mastery of stylized dancing. Documented in textbooks of Chinese classical and folk dance, the very first learning step is to embody “basic postures” (jibentitai 基本体态)—positions of head, shoulders, arms, torso, hips, knees, and feet, as well as each part's relationship to one another—all of which crystallize the body's unique spatial orientation within a genre (e.g., Beijing wudao xuexiao 1958; Beijing wudao xuexiao gudianwu jiaoyanzu 1960; Li et. al Reference Li, Mancheng 唐满城 and Jiamin 黄嘉敏1992; Jia Reference Jia2004). After enduring in each posture, students mobilize the postures into phrases by learning the transition and sequence actualized as rhythmic pattern, music structure, and archetypal expression. In other words, enduring cultivates a moving physicality that rhythmically passes through picturized moments while showing contrasts of speed and energy.

In dance concerts, the posture-oriented aesthetic produces and reaffirms the theatrical convention distinctive to Chinese audiences and constitutes an inherited tradition that has permeated diverse dance genres throughout history. For example, in the oracle bone script, the earliest known form of Chinese writing dating to the late second millennium BC, the Chinese character for “female” (女) was written in this dominant version (Photo 2):

Photo 2. The Chinese character “female” (女) in the oracle bone script, Xiangxing Dictionary 象形字典 (http://www.vividict.com).

The contour of the character resembles a woman sitting on the ground, leaning her chest slightly forward, crossing her hands in the front, pulling her pelvis back, bending her knees and arching her feet, and, overall, displaying a curvy S line that signifies femininity. This marriage of curvy physical line and womanhood endures in the subsequent dynasties as a penetrating aesthetic of female beauty, manifested in relics and dancing bodies in China, as the following brief selection of historical and more contemporary examples make clear. The Dancing Woman Sculpture, excavated from tombs of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD), depicts a woman's performing body in zigzag lines with a backward-tilted pelvis, a front-leaning chest, and bent elbows (Photo 3). The Yellow Onglaze Dancer Sculpture, from the Tang Dynasty (618–907), captured female dancers in S-shaped postures with side-extended hip, opposite-side-leaning torso, and flying long sleeves (Photo 4). In China's Reform Era, female dancers often embody a similar S shape called “three curves” (sandaowan 三道弯) across different styles of Chinese classical and folk dance concerts. In Stepping and Singing (tage 踏歌), a concert Chinese classical dance in 1997 reconstructed from an extinct ancient folk dance popular from the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) to the Song Dynasty (906–1279), female dancers sway their hips side to side, wrap their arms in opposite directions, and loosen their knees, forming varied three-curve positions that are constantly in transition (Photo 5). In Yimeng Love (yimengqinghuai 沂蒙情怀), a concert Han Chinese folk dance in 1994 based on Jiaozhou Yangge in Shandong province in Mideast China, the female dancer embodies a movement theme of the three-curve configuration that features twisted elbow, neck, and hip (Photo 6). The ubiquity of woman-performed S shape physicality throughout dance history in China evidences a theatrical convention that conveys meanings through postures and their transitions.

Photo 3. Dancing Woman Sculpture. Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD). Sichuan Museum, Sichuan, China.

Photo 4. Yellow Onglaze Dancer Sculpture. Tang Dynasty (618-907). Zhengzhou Daxiang Museum, Henan, China.

Photo 5. A screenshot of “Stepping and Singing” (premiered in 1997), performed in 2018. Video published on YouTube, February 7, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u7H3H8w6O-U&t=107s. Accessed July 21, 2021. Copyright Beijing Dance Academy.

Photo 6. Book cover. Pan Zhitao 潘志涛 ed. 2004. Zhongguo minzu minjianwu jiaoxuefa 中国民族民间舞教学法 [Teaching Methodology of Chinese National Folk Dance]. Shanghai: Shanghai yinyue chubanshe.

As an inherited tradition, this posture-oriented kinesthetic value guided the Chinese students to rationalize why the body moves in certain ways instead of others. As a result, the Guangdong program posed a question about how to learn to effectively transition the entry into dancing from holding bodily parts to articulating flow, from the posture-oriented kinesthesia to the gravity-related kinesthesia. Nonetheless, neither the American teachers nor the Chinese students understood this. It became frustrating for the American teachers because they perceived the students as exhibiting a manufactured moving body, one that lacked liveliness and flow when enacting modern dance movements because of its training in holding shapes. It was frustrating for Chinese students, too. When seeking logics of moving in “posturing,” they felt lost in modern dance's dynamic relationships with the ground that discouraged static moments during dancing.

Dance is not a universal language. The American teachers’ and Chinese students’ dancing bodies spoke different languages of American modern dance and Chinese classical and folk dance. Each dance culture had developed its own way of “speaking” that is often characterized by special kinesthetic values. In the Guangdong program, the interactions of the different kinesthetic values generated contingency that challenged both training systems’ viability that dancers in each country took for granted in producing “proficiency.” The Chinese students subjected themselves to a struggling experience of peeling off all the muscular familiarity with performing Chinese classical and folk dance while growing new “bones and muscles” that could fit into performing American modern dance techniques (Wang Reference Wang2016; Yan Reference Yan2017; Yin Reference Yin2017). This struggle and disorientation conditioned their transition to the new area of expertise and, as a mis-stepped training process, enabled the Chinese students to “fluently speak” the language of modern dance.

Approaching Ways of Learning

Besides training professional Chinese modern dancers, another goal of the Guangdong program was to fundamentally transform dance education in China that Yang believed was “backward” in comparison to the United States: “Our dance education was too backward at that time. … American modern dance can bring more advanced educational concepts to us” (Yang Reference Yang2016).

However, behind Yang's glorification of the Western other and her degradation of the Chinese self were two equally self-contained dance educational systems. The encounter of the American and Chinese systems made misunderstandings of how one learned particularly prominent when the dance studio became the classroom for knowledge transmission. A second layer of the mis-step in the Guangdong program thus originated from the differences in the ways that people approached learning in the United States and China.

The American teachers applied a pedagogical approach that I call “variation teaching,” in which they varied the given materials in each class to introduce the shared, overarching metaprinciples. Nielsen and Stackhouse explained this pedagogy in their published interviews, detailing how they applied it in teaching the Chinese students:

This method of variation is what I mean by “conversational dancing”: perhaps saying the same thing from one day to the next, but not in the identical sequence. As I invent new phrases of movement, each related to the previous one but with its own identity. (Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Solomon and Solomon1995, 70)

In the technique class I wanted to span the range from romantic to abstract non-referential movement. I wanted to avoid a buildup of movement or style habit, and to let students experience many ways of moving. … For example, regarding time changes, we tried slower, faster and contrasting speeds within the phrase; we did the phrase in 2/4, 3/4, 5/8, then with another person, responding to his/her timing. (Stackhouse Reference Stackhouse, Solomon and Solomon1995, 89)

The method of variation trained dancers’ acuity by exposing them to quick changes, in which the accumulation of intuitive reactions over time nurtured sensitivity to space, rhythm, energy, and gravity. In the eyes of the ADF teachers, variation teaching represented a viable pedagogy in dance training. Through this pedagogy, the Chinese students could develop flexibility and adaptability as fast learners and secure success in their future professional careers.

Variation teaching challenged how the Chinese students were previously trained as professional dancers, in which their Chinese teachers adopted a pedagogical approach I call “sample teaching”: students learn certain knowledge through inspecting its most condensed version—a sample—that represents all the necessary principles of the large knowledge area. This approach highlights constant revisits to the same case in order to develop a deeper understanding each time. The teacher repeats and adds on to the prioritized materials in each class and, through sample materials, introduces the key concepts applicable to other similar cases. Chinese teachers select combinations that have become classics, which contain movements, sequences, rhythms, music, and facial expressions that crystallize the core aesthetics of a given genre. Students, through learning and even internalizing the prioritized combinations, acquire mastery and comprehension at significant levels. Sample teaching not only governs knowledge transmission in the field of dance, but also other performing arts in China such as xiqu and martial arts. This commonality verifies how traditional Confucian values are influencing Chinese people's educational experiences in contemporary times. Ancient texts, such as I-Ching and the Analects—a collection of Confucius's (551–479 BC) sayings and ideas—have addressed the significance of sample teaching. I-Ching refers to it as “comprehend by analogy” (chuleipangtong 触类旁通), which means to understand the unknown from the attributes it shares with the known. The Analects documents an anecdote in which Confucius proposed a concept “to draw inferences about other cases from one instance” (juyifansan 举一反三) that students should be able to discover other similar cases from one given example, and if they could not, the teacher should refrain from providing more examples to avoid further confusing the students.

At the heart of sample teaching is wu (悟), a self-learning, deep-thinking capability channeled by imitation and repetition. When learning dance movements, a student's mind unravels the moving logic and aesthetic simultaneously when the body executes the act of copying. Imitation entails individualized learning in which it is assumed that, even though students seem to dance in the same way, their minds analyze the movement diversely according to different people's talents, backgrounds, and potentials. Repetition leads to in-depth understanding because every instance of it provides an opportunity to discover the previously overlooked issues and to deploy different lenses that generate new thoughts. Confucius addressed the significance of repetition in his important theory wenguzhixin (温故知新), which means that one can gain new insights through repetitively visiting the old knowledge. Therefore, when students imitate their teachers and repeat the already-learned material, they simultaneously analyze and decode that material and, based on their capability of wu, generate special inferences. For instance, my imitative and repetitive practice of learning the straight punch in Tai Chi martial arts training illustrates how wu generates a progressive apprehension of holism and qi (intrinsic energy). In the first several classes, I paid the most attention to imitating my teacher in terms of how he coordinated different bodily parts harmoniously. After more than a month of repeating the same movement in each class, I started to feel holism in my body, as all my joints and bodily parts moved with unique angles of rotation and mingled into one entity. After several months of repetition, I sensed qi permeating my body and discovered that punching actually meant the burst of qi instead of the manipulation of muscular force. I applied the insights of holism and qi to other Tai Chi practices, such as kicking, hand pushing, and traditional routines. Briefly, I never mechanically replicated the teacher; instead, I was always thinking when I was moving. I acquired those perceptions through practices by myself rather than reciting dogmas from the teacher.

Sample teaching constructs an evolving tradition by facilitating the cooperation of inheritance and innovation—the two sides of a sword that together boost tradition to thrive in its ever-changing sociohistorical habitation. Undergirding the presumption that no one can create from nothing, the method of imitation and repetition builds the foundation of creativity by fortifying a solid mastery and comprehension of the existing knowledge. At a certain point of extensive practice, the personal understandings that have been accumulated over time grant the attainment of maturity and independence. Students, as the new masters, enter a world of freethinking and creation, in which they reinvent vocabularies, theories, and laws. Xun Kuang (荀況 ca. 310–ca. after 238 BC), a renowned Chinese Confucian philosopher, proposed a similar idea that “green is made out of blue but is more vivid than blue,” (qingchuyulanshengyulan 青出于蓝胜于蓝), which emblematizes that students gain knowledge and experience from the teacher and surpass the teacher with their own accomplishments. Consequently, sample teaching activates a cycle of imitation, repetition, and creation that both maintains and renews tradition throughout history.

The two distinctive ways of learning in American and Chinese pedagogical cultures converged in the Guangdong program, and the interaction between them engendered questionable adjustments in both directions. American teachers, unsatisfied with the students’ responsiveness in class, only observed the superficial physical practice while overlooking how students’ minds underwent processes of digestion. They oversimplified Chinese dance education and reduced it to mere imitation and repetition. As Hoving and Nielsen argued,

Asian students … learn by imitation, by repetition. It is hard to get at their individuality. (Hoving 1995, 63)

The Chinese love to imitate; they have a super respect for the “master teacher,” and typically learn through apprenticeship. (Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Solomon and Solomon1995, 69)

These quotes demonstrate a tendency to misread the copying procedure in sample teaching as its core pursuit. More importantly, the words hint at the broader American mission to impart creativity to the Chinese students who were seen as communists and hence as socially conforming more than individually distinctive. In order to “rescue” these students, American teachers might have switched class materials more often than they usually did. However, this adjustment confused the students, who then held on to their previous “mechanic” learning approach more instead of embracing the new approach. Variation teaching, seemingly the valid method, brought more frustration than accomplishments to the American teachers because of their misunderstandings of not only dance education but also social politics in China. I will elaborate on this point in the next section.

In the eyes of the Chinese students, however, variation teaching became an obstacle that hindered them from fully grasping class materials. As Zhang Li said, “The American teachers proceeded too quickly in every class and always changed movement phrases. This is very challenging” (Zhang Reference Zhang2017). Not knowing that the given materials shared certain principles, the Chinese students misunderstood each variation as a disconnected, singular sample that represented unrelated knowledge. Thus, American teachers’ technique classes seemed to introduce excessive amounts of new knowledge that required the Chinese students to do additional practices after class:

[The Chinese students] spent many afternoons videotaping phrases we did in class; thinking they were documenting a precise sequence of steps. I found out toward the end of my residency that the dancers had committed most of my classroom choreography to memory. (Nielsen, Reference Nielsenn.d.)

To videotape, to repeat, and even to recite almost every combination was the learning approach that the Chinese student chose—they endeavored to grasp all the key materials through diligence. The students adjusted to the foreign teachers’ pedagogical approach through a not-so-matching way of learning, but they trusted its effectiveness in honing their dancing skills. Instead of directly resisting their American teachers, these students made self-aware adjustments by framing the foreign ways of learning with their familiar ways of learning in order to gain the knowledge that they wanted. Based on unfamiliarity with each other's culture, the reciprocal-adjusting strategies from American teachers and Chinese students exacerbated the chaotic conversation in the dance classroom instead of calming it.

Neither the American teachers nor the Chinese students recognized the drastic difference in how one learned in each other's dance culture. There existed profound cultural history in that difference, and it required sufficient knowledge to understand it. With or without the American teachers’ help, Chinese dance education has always been transforming in its own way. That transformation focuses on changing curriculum and revising teaching materials, and less on altering how students approach those materials— sample teaching. Unaware of this local situation, the American teachers contributed by forcing an American way of learning— variation teaching— to replace sample teaching that they believed disastrous in cultivating independent individuals. This endeavor of replacement generated contingency on how the foreign concepts would operate within China's dance educational system. Interestingly, under the influence of the Guangdong program, leading dance institutions in China started to add modern dance into the curriculum in the subsequent decades; whereas Chinese students in these institutions still approach the modern dance combinations through their native sample teaching—a “mis-stepped” transformation.

Imparting Conceptions of the Modern

Although a central goal of the Guangdong program was to establish China's modern dance through collaborations between American teachers and Chinese students, behind this goal was the ADF's much more complicated political intention. To highlight the agenda of “helping” instead of cultural imperialism, the ADF emphasized its coming to China as a response to China's call. Reinhart repeated in his interviews that Yang started the whole idea, and the ADF aimed at supporting her (Reinhart Reference Reinhart1987; American Dance Festival 2013). Stackhouse mentioned similar ideas in her interview: “Would I be involved in ‘cultural imperialism’? Probably not, as the invitation actually originated with Yang [Meiqi], director of the Guangdong Dance Academy” (Reference Stackhouse, Solomon and Solomon1995, 85). In addition, the ADF endeavored to justify its benevolent purpose by making adjustments in teaching. Reinhart required that all the ADF faculty should focus on teaching composition classes to offer “tools” instead of using the Chinese students as dancers to choreograph the American teachers’ works; he banned showing films or videos to the Chinese students to refrain from pre-imposing images of American modern dance (Reinhart Reference Reinhart1987; Stackhouse Reference Stackhouse1988; Ma Reference Ma2016). However, accepting the invitation from Yang and creating rules in teaching could not guarantee the ADF's “colonizer-free” position. Behind the scenes, the ADF was building a much larger worldwide empire of modern dance in the 1980s under the direction of Reinhart. The four long-term international programs launched in the 1980s—International Choreographers Workshop (1984–), Mini-ADF (1984–), Institutional Linkage Program (1987–), and International Choreographer Commission Workshop (1987–)—increased the ADF's foreign participants from eight countries in 1982 to forty-two countries in 1992, from 5 percent of total dancer number in 1982 to 33 percent in 1992, and facilitated the ADF to develop international linkage from no country in 1982 to twenty-four countries in 1994 (Townes Reference Townes1995, 3). With financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation and the United States Information Agency (USIA), these international programs disseminated American values and ideals abroad by regulating the transmission of modern dance. The Institutional Linkage Program first started in 1987 through the Guangdong program and later included France, Argentina, South Africa, Russia, and so forth (Townes Reference Townes1995, 19–29). In other words, China constituted one spot in the ADF's world map of its modern dance empire.

Following Reinhart's initiative, the ADF teachers introduced two main methods to stimulate creating Chinese modern dance from within: “self-expression” and “alienating cultural symbols.” I identify self-expression taught in the Guangdong program as making dances by referencing and exposing the inner self—one's feelings, thoughts, and experiences. I refer to alienating cultural symbols as a process of fragmentizing Chinese traditional culture with American modern dance compositional approaches. Both methods seemed convincingly effective in their capability to create Chinese modern dance from within: self-expression could generate authentic modern dance faithfully about the Chinese people themselves; alienating cultural symbols could promise the emergence of Chinese modern dance from “updating” China's own cultural traditions. However, these methods carried US-specific conceptions of the modern that were rooted in individualism, Orientalism, and exoticism. Their implementations in the Guangdong program demonstrated the American teachers’ stereotypical understandings about China's intolerance of individual expression and Chinese dance tradition's incapability of self-renewal. In other words, the Guangdong program introduced a version of the modern based on what the Americans believed China needed. Mutual misunderstandings in the studio promoted the domination of an American outsider's perspective over the Chinese people's self-definition. The third layer of mis-step thus emerged from the divergence between the modern that the American teachers believed they should bring to China, and the domestic definition and experience of the modern at that historical moment.

The American teachers tried to encourage freedom of expression to liberate the Chinese students from the assumed dual constraint of traditional education and governmental control with the tool of self-expression, particularly evident in the composition classes. With the belief that Chinese dance education left little room to develop critical thinking capabilities, they argued that in “the [Chinese] teaching…individuality and creativity are not considered nor are detail and subtlety” (Stackhouse Reference Stackhouse1988), and “the concept of free thinking or individual creativity is not the ‘trained’ way they [Chinese dancers] operate” (Nielsen, Reference Nielsenn.d.).

In addition, Lynda Davis and Claudia Gitelman discovered that performances in China must pass censorship before opening to the public (Davis Reference Davis1990; Gitelman Reference Gitelman, Solomon and Solomon1995). Nielsen recalled that his open class was rescheduled to fit the minister of propaganda's changing schedule (unpublished interview). These experiences confirmed their assumption that “the people in China aren't free” (Nielsen, Reference Nielsenn.d.). Consequently, the goal of liberation prompted American teachers to purposefully design exercises and studies that they thought would cultivate Chinese students’ self-expressive skills. Stackhouse encouraged students to find their own answers in making a dance instead of answering their questions right away (Reference Stackhouse, Solomon and Solomon1995, 89). Stuart Hodes highlighted spontaneous decisions by inviting everyone to improvise a danced self-introduction (Reference Hodes1992, 22). Other teachers instructed students to investigate life as the base for creating dances in assignments such as “depict your wildest dream in a dance” (Yan Reference Yan2017), “anger study” (Hochoy Reference Hochoy1991), and a “dance of the daily routine” (Hodes Reference Hodes1992, 19). Nielsen invented identity-inquiring exercises by asking his students to write a childhood memory and to speak it while dancing their solos:

When they showed me their dances I was disappointed—they all looked too mechanical. … I asked them to go home that night and write down a short memory from their childhood. … Well, Charles, the next day I asked them to tell their stories out loud as they danced their in-place solo, and it was remarkable how their movements looked. (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1988)

As the American teachers planted the seed of self-expression, it grew divergently in each individual, because students developed different ideas of freedom in practicing those exercises and studies. For some Chinese students, the concept of self-expression made them feel lost because of their failure in immediately discovering “who I am”: “The teachers asked us to discover my individuality. What was my individuality? What was special about me? I didn't know at that time” (Ma Reference Ma2017). Other students, however, had more complex responses to the question of “freedom.” Some found freedom in the dancer-choreographer role integration: “At that very young age, to dance my own choreography is already a freedom. … I had not choreographed before” (Yan Reference Yan2017). A few other students discovered “being free” when dancing as who they were: “I gain freedom when I speak from my own deep heart, to fully express my own ideas” (Zhang Reference Zhang2017).

The Chinese students made a genuine but unequal comparison between their previous dancing and performing experience and their dancing and composing experience in the Guangdong program, which may mislead a reader to believe that American modern dance intuitively liberated these students. However, I submit that different dance cultures develop different practices and conceptions of “being free.” The young Chinese students, who were at their early career stage when joining the Guangdong program, only experienced a part of China's overall dance system and used this partial experience as representative of China's whole dance system to make misleading comparisons. Their extensive dancing background and lack of compositional training before aroused a feeling of freedom in the agency to make and execute decisions as they engaged with compositional exercises in the Guangdong program. Gaining this agency through modern dance instead of Chinese classical and folk dance falsely verified dance in China as insufficiently liberating and modern dance as “being very free.” In addition, realism, the mainstream artistic ideology in China that focused on portraying archetypes, shaped the Chinese students’ performing experience before the Guangdong program. Since the 1950s, the PRC had been applying Friedrich Engels's definition of realism from Russian Marxism to regulate all fields of art: “Realism means to truthfully represent an archetypical character in a representative circumstance” (Lv and Yi Reference Lv and Yi1992, 105). This ideology was perpetuated in the Reform Era and impacted people's dancing and viewing experience in which the archetypes packaged the “self” and dissolved it during a performance. Consequently, prior to the Guangdong program, the Chinese students expressed their own emotions through the lens of certain characters and conveyed their understandings of life in stories of others. They refrained from projecting themselves directly to the audiences, but rather, they used a character that both the performer and the audience resonated with as a medium to facilitate communication. In contrast, the Guangdong program's composition classes provided a scenario in which the Chinese students were themselves when performing their dances. The students presented their physical responses to an open-ended question, visualized through the body their wildest dreams, and moved with speeches about their childhood memory. This frank exhibition of the “self” peeled off layers of character, story, and concepts of realism, and illuminated the meaning of freedom.

As Joshua Chambers-Letson said, “Freedom is a problem. Freedom has been colonized, absorbed, stolen, and made a utility by and for white liberal political reason” (Reference Chambers-Leston2018, 6). The Chinese students did experience a sense of freedom, but this freedom differed from the freedom that the American teachers tried to impart. The American teachers hoped to impart a freedom as artists’ social responsibility, or, as Chambers-Letson calls it, “a possession or right” (2018, 6). In this view, self-expression bore the potential to challenge the dominant communist ideologies and the educational dogmas in China that the American teachers believed repressed the spirit of humanity. In contrast, the Chinese students gained a sense of freedom as a break from the familiar. Chambers-Letson describes this kind of freedom as an in-the-present experience generated by corporeal performance, an ephemeral “instantiation of something better than this” (Reference Chambers-Leston2018, 8). Therefore, the Chinese students discovered freedom in trying things that they never did in the past—a mis-step from what their American teachers had expected.

Besides self-expression, the American teachers introduced alienating cultural symbols to facilitate creating Chinese modern dance from within. However, how they instructed the Chinese students in the dance studio demonstrated unintentional exoticization of Chinese culture. Although each teacher applied different pedagogies and examples, they shared a common strategy of referencing Chinese cultural tradition in composition classes and rehearsals in order to avoid importing American symbolic imagery. Unfortunately, the American teachers’ unfamiliarity with Chinese culture resulted in their choosing only identifiable materialized symbols to represent Chinese tradition. To be clear, this article does not criticize the endeavor to create Chinese modern dance based on China's cultural tradition. Rather, I question the Orientalist approach that reduced Chinese tradition into the all-too-familiar tangible objects and the “easy” experimentation that projected the objectified Chinese tradition directly under the culturally specific American modern dance compositional methods. Nielsen chose dudou, a traditional woman's undershirt, as the costume for the group dance that he choreographed for Chinese students (Zhang Reference Zhang2017). Lynda Davis selected a porcelain vase and ancient Chinese characters as the score for her composition exercise (Jiang Reference Jiang2017). To illustrate how to work with these cultural symbols, American teachers adopted a method common in composition classes in the United States—a scientific study through the lenses of space, time, texture, and shape—to analyze the physical properties of a given item, such as a roll of toilet paper. Then, they replaced the items usually used in the US classrooms with Chinese cultural symbols in the Guangdong program. In her composition class, Davis analyzed the features of a porcelain vase—the blue color, the curvy lines of the flowers, and the hard texture of its surface—and then adopted the same dancing approach that she would do with a roll of toilet paper to improvise with the geometrical features of the porcelain vase (Lu et. al Reference Lu, Yun 海云 and Dong 江东1990). However, a porcelain vase is not toilet paper, and they contain different cultural histories. A roll of toilet paper, in general, represents a problematic “universal” and “modern” product, whereas a porcelain vase signifies something more culturally specific and traditional. A porcelain vase was originally an ornament in the palace or traditional Chinese house to signify the owner's elite social status. Davis imbued it with a new meaning of abstract shape and color in a performance setting that had nothing to do with power and prosperity signified in the vase's original cultural context. This replacement proposed a problem that a choreographic approach common and effective in the United States could not ensure the same in China.

Instead of evaluating their American teachers’ examples as appropriate or questionable, the Chinese students misread those examples as something to respect because they participated in those creation procedures in the same way as they learned Chinese classical and folk dance. The American teachers hoped that their examples functioned as inspirations, instead of clear answers. Unfortunately, unaware of this hope, the Chinese students “inherited” the Orientalist method and created works filled with cultural symbols such as chopsticks, fans, and water sleeves. The uncritical adoption reduced profound Chinese culture into superficially easy-to-read symbols that not only lost its signified in a traditional setting, but also failed to make sense with a new Orientalist signified in a contemporary setting. The Chinese students completely alienated themselves from their own culture. As Wang Mei later recalled: “At that time, later I realized that it was wrong to always continue with what the Americans did. … We needed to have something our own” (Wang Reference Wang2016).

The Guangdong program mis-stepped into a paradox: it created China's own modern dance while simultaneously constructing Americanized Chinese modern dance. The ADF-Guangdong exchange interrupted China's domestic vibrant dance modernization and geared that step toward a new direction suggested by the Americans. Before the Guangdong program, local dance artists—such as Hu Jialu and Hua Chao, the forerunners of Chinese modern dance in the early and mid-1980s—purposefully repelled objectified cultural tropes in their experimental works. They framed western modern dance vocabularies with the domestic aesthetic of realism so that their version of “the modern” refuted formal and textual similarity with “the traditional.” In contrast, the Guangdong program introduced an Orientalist version of Chinese modern dance, in which the American teachers embraced the objectified traditional cultural symbols that local Chinese dance artists shunned on purpose. This difference of choreographic interest shifted the local audiences’ attitudes toward a high tolerance of the American input while degrading the local modernist pursuits. After the Guangdong program's end-of-first-year debut in 1988, Chinese critics started to criticize Hu's and Hua's works as not “modern” enough and at best “tentative Chinese modern dance” (Hu Reference Hu1989). Soon, Hu left China for the United States in 1989 and later became a mainstream gala producer after returning to China in 1993; Hua left for Hong Kong in 1992 and never returned to mainland China (Tsao Reference Tsao2015). Both artists permanently disappeared from mainland China's modern dance scene. The Guangdong program made a complete detour around the realism-based local modern dance—not a happy ending for everyone.

On the flip side of this cultural damage, a new history started. The Orientalist version of Chinese modern dance introduced a new perception that “the modern” could re-territorialize tradition, instead of always repelling tradition. Self-expression and alienating cultural symbols cultivated a Chinese character of the modern based on an American standard. Interestingly, this exoticized version received applause from Chinese dance critics in 1988 and then criticism two years later in 1990, which coincided with the country's drastic ideological shifts before and after the Tiananmen Square protest in 1989, from adoring Western wisdom to resisting its impact on China. The criticism from Chinese critics stimulated Chinese dance artists’ localization of the Orientalist approach in the 1990s and the twenty-first century. For instance, Qing Liming and Qiao Yang, who stayed to establish the Guangdong Modern Dance Company, sought a more conceptual, instead of materialized, theme of yin-yang balance in their award-winning duet Tai Chi Impression (1991). Wang Mei, who served as a member of the faculty of modern dance at the BDA after graduating from the Guangdong program, took a different experimental approach in her widely influential piece Red Fan (1994), in which she explored the unconventional physical conversation between the body and the prop while maintaining the fan in a performance setting as it had been used traditionally. These endeavors designated Chinese choreographers’ self-aware impetus in unfolding tradition that departed from repeating what their American teachers had problematically done. The cross-cultural encounter in the Guangdong program did generate new versions of Chinese modern dance, but unsolvable miscommunications and irreparable cultural damage paved the way for these achievements.

Conclusion: Imaging China

A core goal of this article is to rethink the role of China in dance studies. By proposing the concept of mis-step, I imagine a possible escape from the self-repetitive narratives about dance and the modern in China, most often only meaningful to people living in the West. China should not serve as another previously overlooked “area studies” to be included in dance studies and to fit into the already established Euro-American-centric worldview, within which dance in China is fully knowable through the lenses of revolutionary nationalism, imperialism, liberalism, and other grand perspectives. Mis-step introduces a new lens to examine China, its dance, and its relationship with the West, and aspires to converse with research of other cross-cultural corporeal encounters in global spaces. By celebrating the unknowable, mis-step rewrites transnational dance history and leads to somewhere slippery and potentially exciting.