Introduction

All mental health professionals involved in the treatment of people with serious mental illness (SMI) must consider their capacity to make decisions about their treatment, among other issues. People with SMI, are defined by the National Institute of Mental Health of the United States as ‘a heterogeneous group of persons that suffer from severe psychiatric disorders with mental disturbances of prolonged duration, entailing a variable degree of disability and social dysfunction’ (Parabiaghi, Bonetto, Ruggeri, Lasalvia, & Leese, Reference Parabiaghi, Bonetto, Ruggeri, Lasalvia and Leese2006). Decision-making capacity (DMC) is a core concept underlying SMI and can be difficult to determine, but its importance is clear, especially in legal settings. Some countries regulate capacity at judicial level (e.g. Spain), while others determine this through a clinical team (e.g. England and Wales). In 2007, a review concluded that the majority of psychiatric patients have capacity, that clinical variables have an influence on the capacity for treatment decisions, and that its evaluation can be easily replicated (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007).

Since the work covered by that review, the United Nations established the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006. It proclaimed that the rights and freedoms of persons with disabilities must be respected as those of any other person and their full integration into society must be guaranteed, understanding ‘disabilities’ as ‘the results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’ (United Nations, 2006). This influenced new legislation in many countries, especially in mental health. In England and Wales, the Convention has played a significant role in debates concerning the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (Series, Reference Series2020) with the concept of a functional test of capacity remaining in law (Ruck Keene, Kane, Kim, & Owen, Reference Ruck Keene, Kane, Kim and Owen2023). On the other hand, in Spain, for example, legislation relating to legal capacity was reformed, with important changes such as the annulation of incapacity verdicts in favor of support provision verdicts or incorporating reference persons who would assist the person with SMI in their decisions, but without replacing their will (Barrios Flores, Reference Barrios Flores2020).

Recent studies have analyzed capacity in psychiatric patients, with mixed results. Some found that most patients lack capacity for assessment or treatment decisions (Lepping, Stanly, & Turner, Reference Lepping, Stanly and Turner2015), some found variations between different decisions (Maxmin, Cooper, Potter, & Livingston, Reference Maxmin, Cooper, Potter and Livingston2009) and others that most patients had capacity (Calcedo-Barba et al., Reference Calcedo-Barba, Fructuoso, Martinez-Raga, Paz, Sánchez De Carmona and Vicens2020). There is also no clear consensus regarding patients admitted involuntarily or voluntarily to hospital (Pons et al., Reference Pons, Salvador-Carulla, Calcedo-Barba, Paz, Messer, Pacciardi and Zeller2020), (Curley, Watson, & Kelly, Reference Curley, Watson and Kelly2021; Pons et al., Reference Pons, Salvador-Carulla, Calcedo-Barba, Paz, Messer, Pacciardi and Zeller2020). The different cognitive and clinical variables influencing this construct (Cáceda, Nemeroff, & Harvey, Reference Cáceda, Nemeroff and Harvey2014; Larkin & Hutton, Reference Larkin and Hutton2017), and the diversity of capacity measurement instruments (John, Rowley, & Bartlett, Reference John, Rowley and Bartlett2020), hamper our ability to draw clear conclusions from this work. A recent meta-analysis of four studies (Spencer, Shields, Gergel, Hotopf, & Owen, Reference Spencer, Shields, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2017) focused on patients with schizophrenia, and only reported on the proportions of people with capacity for treatment decisions. More recently, the review by (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Watson and Kelly2021) included psychiatric patients but did not conduct a meta-analysis.

The primary aim of this study was to update (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007) using a rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis. Okai and colleagues did not include a meta-analysis, because the studies were heterogeneous. We will address concerns about heterogeneity by:

(a) conducting a random effects meta-analysis, which incorporates heterogeneity between studies into the model;

(b) updating the review, which increases the sample size, and therefore the ability to explore heterogeneity using sensitivity analysis.

Finally, we will attempt to answer definitively three questions from the previous review:

(1) Is the assessment of capacity for treatment decisions easily replicable?

(2) What is the proportion of psychiatric inpatients considered unable to make treatment decisions?

(3) What are the factors associated with lack of capacity for treatment decisions in psychiatric patients?

Methods

We used the same inclusion criteria as in (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007). We included quantitative studies, in English or Spanish, with an adult psychiatric inpatient sample, and data on the evaluation of capacity for treatment.

We were particularly interested in studies that reported, in detail, data of patients who lack treatment capacity, and the inter-rater reliability of capacity assessments. Studies were excluded if they were: conducted in people under 18 years of age; exclusively about organic psychiatric disorders (dementia or delirium) or intellectual disability; case reports, commentaries or review articles; or reviews of case notes.

The literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. We performed a systematic search using the most relevant online databases: Scopus, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. For our search strategy, we used the keywords ‘mental capacity’ or ‘competence’ or ‘decision-making’ AND ‘severe mental illness’ or ‘psychiatric’ or ‘schizop*’ or ‘bipolar’ or ‘schizoaffective’ or ‘obsessive-compulsive’ AND ‘treatment’. We selected articles from 2006 to May 2022, to capture studies published since (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007).

Before conducting the search, the study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (an international prospective register of systematic reviews [ID CRD42022330074]). The ‘Rayyan’ program, which is a digital platform used to carry out systematic reviews (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016) was initially used by S.M and access was granted to a second reviewer (K.A) to independently review a representative group of articles (19) and to assess the reliability of the study selection procedure. The senior researchers (A.D and G.O) supervised the protocol development and selection process.

We screened every article by their title and abstract, excluding studies that did not meet our inclusion criteria. Following this, we reviewed the full text of each potentially eligible article to decide whether or not to include them (see Fig. 1). Inter-rater reliability was almost perfect (kappa index: 0.94) (McHugh, Reference McHugh2012). There were only two discrepancies, which were resolved by consensus.

Figure 1. A preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram that outlines the study selection process.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out independently by the first reviewer (S.M), using Microsoft Excel. The second reviewer (K.A) independently extracted from 19 studies that were eligible at full text level on a separate Excel sheet, to ensure consistency.

First, we extracted data and categorized it following the three main research questions from the original study. Next, 11 studies which included sufficient data for meta-analysis (six from (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007) and five from our search) were included in the review. Once included, correlations between capacity and clinical or cognitive measures were extracted. Finally, a quality assessment of included papers was conducted following an established checklist (Kmet, Lee, & Cook, Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004). Articles from Okai's review have been also included in the qualitative review and they can be consulted in Supplementary Material.

Quantitative analysis

We explored the effect of psychopathology on binary capacity judgments (either clinical judgments or cut off scores) using random-effects meta-analyses using R Statistics.

For the meta-analysis, we used the restricted maximum likelihood method to calculate effect sizes (Cohen's d), which were weighted by the inverse of the sampling variance: meaning that studies with higher variance contributed less to the composite effect size. We used conventional criteria to interpret these effect sizes (0.2 = small; 0.5 = medium; 0.8 = large) (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Measures with a negative scoring system were transformed, therefore all positive effects indicate a better psychiatric outcome. We then conducted sensitivity analyses for each meta-analysis to assess risk of bias at the study level, including heterogeneity (e.g. I2 statistic), influential cases (e.g. Cook's distance) and publication bias (funnel plots and Egger's test).

We also used strategies to handle missing data. When studies reported a median and interquartile range, we estimated the mean and standard deviation (s.d.) using conventional formulae (Luo, Wan, Liu, & Tong, Reference Luo, Wan, Liu and Tong2018; Wan, Wang, Liu, & Tong, Reference Wan, Wang, Liu and Tong2014). When both of these were absent, we estimated the standard deviation using prognostic imputation (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Liu, Hunter and Zhang2008). This method calculates the average of observed variances in similar studies to estimate the missing s.d. value. Studies that did not report sufficient data to use any of these methods were excluded.

Finally, we calculated confidence intervals and effect sizes (unadjusted unless stated otherwise) in the qualitative analysis section, to support with the interpretation.

Results

A total of 5351 references were initially identified. 3148 duplicates were resolved, leaving 2201 records to screen. 2161 records were excluded after consulting title and abstract, due to background/context wrong population, study design, publication type, outcome, or foreign language. 40 records were assessed for full eligibility and retrieved for closer examination. We excluded 20 and extracted data from the 20 remaining studies (see Fig. 1).

Capacity assessments

From the 20 included studies (see Appendix 1), 11 (54.55%) used the MacCAT-T (MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment) to assess capacity for treatment. This tool consists of four subscales: understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and expressing a choice. Since the MacCAT-T does not have a cut-off score, some studies combined the test with the clinical interview to decide on the patient's capacity (Bilanakis, Vratsista, Kalampokis, Papamichael, & Peritogiannis, Reference Bilanakis, Vratsista, Kalampokis, Papamichael and Peritogiannis2013; Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge, & Kennedy, Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008, Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009; Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011; Skipworth, Dawson, & Ellis, Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013). Other studies used the ability or inability to ‘express a choice’ as a validating criterion to decide who was incapable (Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill, & Kennedy, Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill, & Kennedy, Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008). Only one study specified a cut-off point (Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Tarsitani, Parmigiani, Polselli, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2014), in which patients lacking capacity scored below 50% on two or more of the four subscales.

Several other methods of assessing capacity were reported. These included semi-structured interviews with different cut-off points (Di & Cheng, Reference Di and Cheng2013; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Moye et al., Reference Moye, Karel, Edelstein, Hicken, Armesto and Gurrera2007; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Rhee, S, K and R2011), vignettes (Moye et al., Reference Moye, Karel, Edelstein, Hicken, Armesto and Gurrera2007) or clinical interviews conducted by specialized teams (Chiu, Lee, & Lee, Reference Chiu, Lee and Lee2014; Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein, & Ana-maria Losif, Reference Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein and Ana-maria Losif2009). In some cases, the interviews were guided by legal criteria according to the Mental Capacity Act or equivalent of each country (Curley, Murphy, Plunkett, & Kelly, Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019c; Tor, Tan, Martin, & Loo, Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020).

Capacity was assessed as present or absent (capable/incapable) in all but two studies. In one study, the sample was divided between high (patients who scored more than 75% in the subscales and maximum score in express a choice) and low capacity (Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018). The other study (Curley, Murphy, Plunkett, & Kelly Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019b) graded capacity as either total, partial or lacking (no score above one in any area).

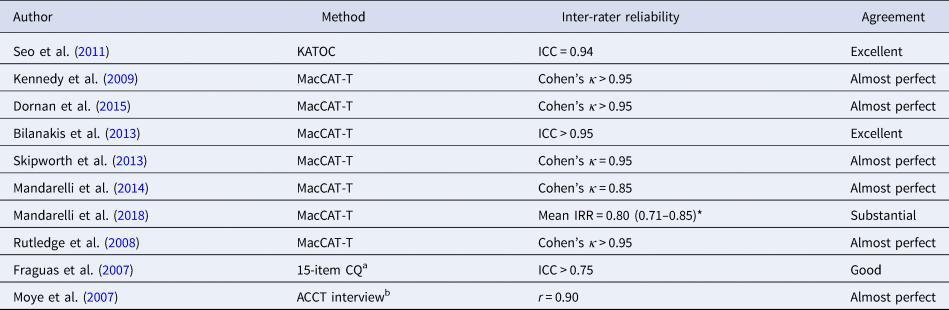

Reliability of the assessment

10 studies reported on the inter-rater reliability of capacity assessments for treatment decisions (see Table 1). These studies assessed reliability using at least one of two methods: by administering a scale which is then verified by an independent expert evaluator(s) (Moye et al., Reference Moye, Karel, Edelstein, Hicken, Armesto and Gurrera2007; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Rhee, S, K and R2011), or by conducting a joint interview using a single method of evaluating the patient (Bilanakis et al., Reference Bilanakis, Vratsista, Kalampokis, Papamichael and Peritogiannis2013; Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein and Ana-maria Losif2009; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Tarsitani, Parmigiani, Polselli, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2014; Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013). The number of evaluators and interviews varied.

Table 1. The inter-rater reliability of capacity assessments in psychiatric inpatients

*95% Confidence interval. The type of inter-rater reliability statistic was not specified.

a Score for the Competency Questionnaire (CQ) was reported to be at least 0.75 but final score not reported.

b Assessment of Capacity to Consent to Treatment (ACCT).

Prevalence of mental capacity in psychiatric inpatients

Deciding hospitalization

Three studies evaluated the capacity of psychiatric patients to decide on hospital admission. In each one they used a different scale, so the results must be interpreted carefully. Tentatively, it could be said that at least 48% of psychiatric patients do have the capacity to decide on hospitalization at the time of admission (Di & Cheng, Reference Di and Cheng2013; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Rhee, S, K and R2011), but this number might reduce between 5% and 27% if decision-making about treatment is part of the same assessment (Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf, & Owen, Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018).

Deciding treatment

11 studies measured the proportion of patients able to decide various treatments. Regarding ECT, the two studies that evaluated this (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lee and Lee2014; Tor et al., Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020) used the clinical criteria of a psychiatrist. They found that more than half of patients lacked capacity (between 51.7% and 75.1%). Both capacitous and incapacitous patients generally improved in their psychiatric symptoms following treatment.

Regarding the ability to decide between two medications or no treatment, around 25% of patients were unable to express a choice (Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008), increasing to 37.5% (95% CI [27–48%]) if more information was given (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009). In one study, the proportion of 160 patients who lacked capacity decreased from 24.3% (95% CI [12–41%]) at admission to just 5.4% (95% CI [0–2%]) at follow up (Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007).

Based on MacCAT scores, around 76% of patients subjected to involuntary hospital admission had low capacity to decide whether to continue receiving their current treatment (Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Tarsitani, Parmigiani, Polselli, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2014, Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018), compared to just 30% of voluntary inpatients (Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Tarsitani, Parmigiani, Polselli, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2014). In another sample, only 1.86% (95% CI [0–5%]) of 215 inpatients were considered to be totally incapable of consenting to treatment (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019b). Nevertheless, the results may also depend on the cut-off criteria of the assessment method, because the latter study applied a more conservative cut-off point with the MacCAT (deeming incapable those whose total score was <2 v. the more used criterion of scoring below 50% in 2 or more subscales or based on clinician rating). On the other hand, when the Irish legal criteria was used for this sample, instead of questionnaires or scales, then this figure increased to 34.9% (95% CI [29–42%]) of inpatients being considered to lack capacity (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019c).

Variations in assessment methods should also be considered. (Moye et al., Reference Moye, Karel, Edelstein, Hicken, Armesto and Gurrera2007) used three hypothetical vignettes to elicit treatment choices for an imaginary medical condition, which varied in length and complexity. Clinicians rated capacity using an interview, based on the MacCAT subscales. They concluded that 80% of psychiatric patients lacked the ability to decide between two hypothetical treatment options. However, the hypothetical treatment options were relatively uncommon for psychiatric inpatients. The article also does not report capacity ratings for the simpler vignettes.

The remaining studies show high heterogeneity in the decision to be evaluated, without specifying the treatment (Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein and Ana-maria Losif2009; Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008, Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011) as well as in the rate of incapacity, which ranges from 10% to 87% in the samples.

Factors related to mental incapacity

Sociodemographic factors

Nine studies focused on the sociodemographic factors associated with incapacity (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lee and Lee2014; Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019b, Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019c; Di & Cheng, Reference Di and Cheng2013; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018). No studies found a robust association between capacity and sex. One study (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019b) found a weak effect of females having better MacCAT scores in a multivariate analysis, but the bivariate analysis was non-significant. Another study found that being female predicted incapacity in a bivariate analysis (OR 0.19, 95% CI [1.07–3.56]), which became non-significant when adjusting for alcohol or substance dependence (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009). Another study found a borderline significant effect in the other direction, with females being more likely to be judged as lacking capacity (OR 1.96, 95% CI [1.07–3.56]) but the effect became non-significant when this was controlled (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009). Only one study found a significant association with older age (Curley, Murphy, Fleming, & Kelly, Reference Curley, Murphy, Fleming and Kelly2019a).

Regarding ethnicity, two studies found that Black ethnicity was associated with poorer capacity, compared to White European ethnicity (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008, Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011). Black patients were significantly less likely to regain capacity for treatment decisions, compared to White patients (OR 0.29, 95% CI [0.11–0.74]). More specifically, Black African (OR 0.14, 95% CI [0.05–0.37]) and Black Caribbean (OR 0.32, 95% CI [0.13–0.78]) patients were significantly less likely to have capacity to make treatment decisions. These effect sizes became non-significant after controlling for differences in substance misuse, self-harm and diagnosis together, suggesting a potential confounding effect.

The patient's level of education was positively associated with capacity in one report (Di & Cheng, Reference Di and Cheng2013). Unemployment was associated with incapacity in three studies (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019c; Di & Cheng, Reference Di and Cheng2013; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013). Finally, patients who had longer hospital admissions were more likely to lack capacity (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lee and Lee2014; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007).

Psychopathological variables

Schizophrenia was the psychiatric diagnosis associated with the highest rate of incapacity in six studies (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019c; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018; Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009, Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011, Tor et al., Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020), followed by bipolar affective disorder (BPAD) of the manic type (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lee and Lee2014; Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018; Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009, Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013; Tor et al., Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020), and depression (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008, Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011, Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009; Tor et al., Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020). In only one paper, there were higher rates of incapacity for manic BPAD patients (97%; 95% CI [86–100%]) compared to schizophrenia (81%; 95% CI [71–89%]) (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008) although this difference was non-significant. Other diagnoses associated with incapacity were personality disorders (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008, Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009), affective disorders (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019c; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein and Ana-maria Losif2009) and substance use disorders (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019b; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein and Ana-maria Losif2009), but to a lesser degree (from 0.9% to 34%) and with a greater likelihood of regaining capacity (Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011).

In general, the included studies suggest that psychiatric symptoms are also associated with incapacity (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011). Positive symptoms were found to be associated with incapacity in eight studies (Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015; Fraguas et al., Reference Fraguas, García-Solano, Chapela, Terán, de la Peña and Calcedo-Barba2007; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018; Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018), especially conceptual disorganization (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013), manic symptoms (Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Tarsitani, Parmigiani, Polselli, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2014, Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018), delusions (Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018) and unusual thought content (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009). Hallucinations were correlated with capacity in non-psychotic disorders (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009), but not in psychotic disorders (Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018). Across inpatients, poor insight was also a consistent and strong predictor of incapacity (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009, Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Rhee, S, K and R2011; Skipworth et al., Reference Skipworth, Dawson and Ellis2013; Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018) although in patients with a diagnosis of depression poor insight was a poor predictor of incapacity (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008) and regaining capacity was less associated with change in insight (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009). Finally, low global functioning predicted incapacity in four studies (Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008; Tor et al., Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020).

Other studies also found that cognitive performance is relevant to capacity, although they used the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Bourgeois, Klein and Ana-maria Losif2009) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Tor et al., Reference Tor, Tan, Martin and Loo2020) as measures, which are both screening tests, so their conclusions must be considered with caution. Impairments in short-term memory were also associated with poorer capacity (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2018). Only one study analyzed psychiatric medication use in relation to incapacity. The authors concluded that patients taking clozapine showed greater improvement in capacity, especially appreciation; that is, they had better ability to decide than those treated with other psychotropics (Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015).

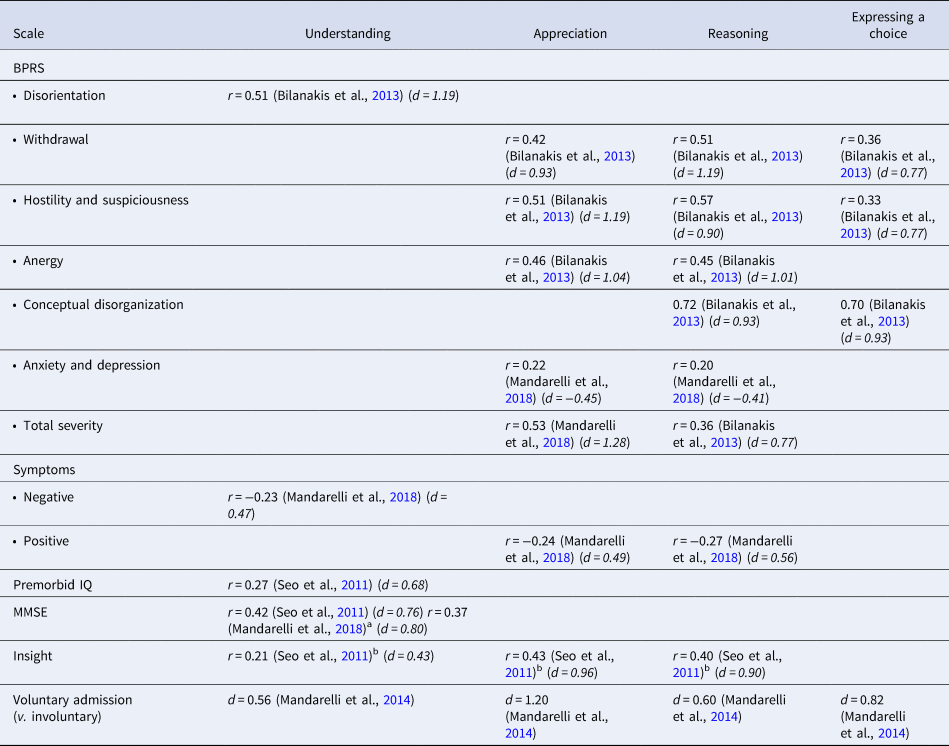

MacCAT

Six studies analyzed the relationship between psychopathological and cognitive variables with the different subscales of the MacCAT (Bilanakis et al., Reference Bilanakis, Vratsista, Kalampokis, Papamichael and Peritogiannis2013; Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Tarsitani, Parmigiani, Polselli, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2014, Reference Mandarelli, Carabellese, Parmigiani, Bernardini, Pauselli, Quartesan and Ferracuti2018; Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Kim, Rhee, S, K and R2011). Four of these studies reported significant associations, which are summarized as effect sizes in Table 2. Through non-parametric analysis, being able to express a choice was also significantly associated with better global functioning (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008), as well as lower positive symptoms and overall psychopathology (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Dornan, Rutledge, O'Neill and Kennedy2009; Rutledge et al., Reference Rutledge, Kennedy, O'Neill and Kennedy2008).

Table 2. A table outlining significant relationships between the MacCAT sub-scales and psychopathological or cognitive variables (higher scores indicate less severe psychopathology or cognitive impairment)

a Association found in Schizophrenia sample but not Bipolar.

b Using the KATOC scale, which is based on the MacCAT.

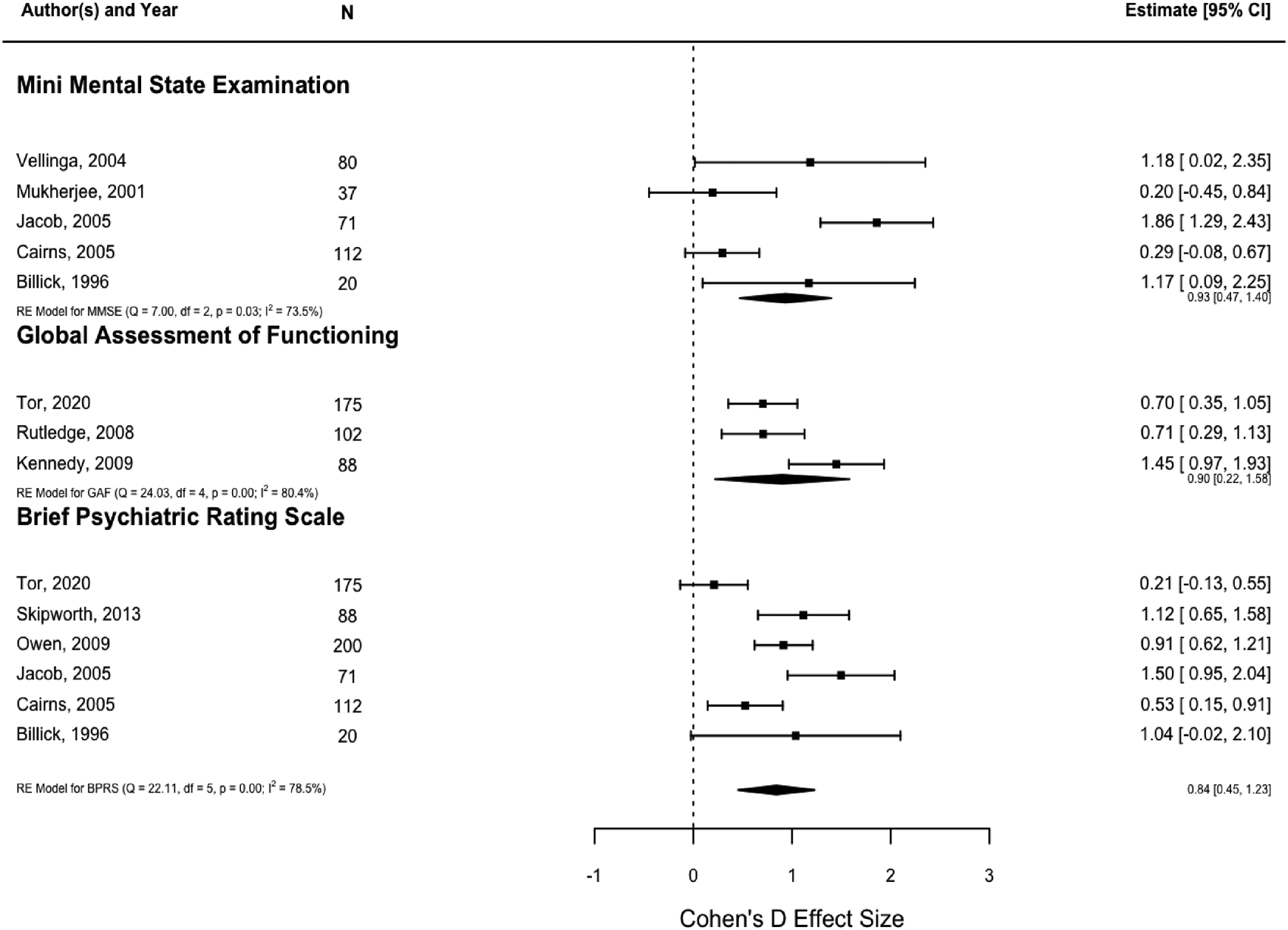

Meta analysis

When combining our sample with studies from (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007), 10 studies reported sufficient data on the association between psychopathological measures and capacity for treatment decisions, for inclusion into the meta-analysis (see Fig. 2). Six studies reported on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), five used the MMSE and three used the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale (see Appendix 2).

Figure 2. A forest plot showing the relationship between capacity for treatment and three psychopathology measures (higher scores indicate less severe psychopathology).

Patients with capacity had significantly higher MMSE scores than patients without capacity, indicating greater cognitive functioning, with a large effect size (d = 0.93, CI [0.47–1.40]). Patients with capacity had significantly higher GAF scores than patients without capacity, indicating greater overall functioning, with a large effect size (d = 0.90, CI [0.22–1.58]). Finally, patients with capacity had significantly lower BPRS scores than patients without capacity, indicating lower total symptomatology, with a large effect size (d = 0.84, CI [0.45–1.23]). Overall, these results suggest that capacity to make a treatment decision is strongly associated with psychiatric morbidity.

Sensitivity tests show that there was moderate-to-large heterogeneity which was significant for all three analyses (I 2 = 73.55–80.40%, p < 0.005). The results above should therefore be interpreted with caution. Based on Cook's distance, there was only one potentially influential case, in the MMSE analysis (Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Clare, Holland, Watson, Maimaris and Dunn2005). This study effect was in the expected direction, but excluding it would have made the pooled effect non-significant. There was no suggestion of publication bias (Egger's test p > 0.05).

Quality study of the articles included

Following our quality assessment (see Supplementary Material), most of the included studies were rated as high or medium quality. The main strengths were the explicit objectives, study design, sample size, and conclusions. The description of the sample was often incomplete (e.g. limited sociodemographic data) and several studies only analyzed the full dataset, rather than patient subgroups. Furthermore, only three studies included blind evaluators.

Discussion

This study provides an updated systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on decision making for treatment in all psychiatric inpatients. The main objective was to update the results of a previous review (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007) focusing on three key questions. Our results also update and provide greater detail to some of the results provided in a more recent meta-analysis (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Shields, Gergel, Hotopf and Owen2017).

Reliability of capacity assessments

The first question was whether capacity assessments for treatment decision-making could be easily replicated. As in (Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007), we found that capacity assessments for treatment decisions have strong inter-rater reliability, either when professionals evaluate this jointly or on separate occasions. As noted by Cairns et al., Reference Cairns, Maddock, Buchanan, David, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2005 and Raymont et al., Reference Raymont, Buchanan, David, Hayward, Wessely and Hotopf2007, the latter also suggests strong test-retest reliability. By replicating this finding, our results suggest that changes in policy and practice over the previous 15 years have not significantly changed the reliability of capacity assessments. We have also found this result across several countries, therefore differences in capacity legislation did not have a noteworthy effect on reliability in our sample. These studies included a semi-structured scale as part of their evaluation, which may have improved reliability compared to standard clinical practice.

Proportion of psychiatric inpatients lacking capacity

The second question is difficult to answer due to the variety of instruments for assessment of capacity and the differences in legal criteria between jurisdictions. Psychiatric inpatients, though distinguishable from general medical inpatients or non-hospital samples, are found in a variety of settings. The MacCAT-T remains the most frequently used psychometric assessment (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Ungvari, Ng, Wu, Wang and Xiang2017), but it lacks an established cut-off point to produce a binary measure of capacity. In our sample, the 18 studies that have used binary measures of capacity showed varying rates of incapacity. Invariably, studies that adopted more conservative cut-off points found higher rates of incapacity. This is consistent with other studies of the effect of arbitrary cut-off points using the MacCAT- CR which assesses capacity to decide upon participation in research (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Palmer, Appelbaum, Saks, Aarons and Jeste2007). So it is ultimately left to researchers to decide on an appropriate cut-off point and this is a potential source of reporting bias (Banner, Reference Banner2012).

Qualitative analysis suggested some explanations for variations in capacity rates. First, using standardized assessment instruments seemed to lead to higher rates of incapacity, compared to clinical judgment. It is true that some professionals consider incapacity to be synonymous with treatment refusal (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lee and Lee2014; Okai et al., Reference Okai, Owen, McGuire, Singh, Churchill and Hotopf2007) or the inability to provide informed consent (Lamont, Stewart, & Chiarella, Reference Lamont, Stewart and Chiarella2016) but it is important to also mention that while informed consent and capacity are related concepts, they are not interchangeable. Capacity is a prerequisite for providing valid informed consent, but having capacity doesn't necessarily mean someone has provided informed consent. Also, a clinical assessment can take into account other cognitive, emotional and phenomenological factors that are not covered by structured tests (Breden & Vollmann, Reference Breden and Vollmann2004), enabling a more comprehensive capacity assessment. Studies which combine structured assessment with clinical judgment are likely to give better overall assessment.

Second, the presentation of the information may have affected capacity rates. For example, when treatment decisions were assessed individually, less than half of the patients lacked capacity (25% to 43%). However, we found a higher incapacity rate when two decisions were considered as part of the same assessment (69%). Reducing the amount of arbitrary information was also found to support decision-making. Both factors could be potentially explained by impairments in executive functioning, such as working memory or attention, that has been widely reported in psychiatric patients (Testa & Pantelis, Reference Testa, Pantelis, Wood, Allen and Pantelis2009; Yaple, Tolomeo, & Yu, Reference Yaple, Tolomeo and Yu2021). The MacCAT subscale of ‘appreciation’ is conceptually and empirically associated with both capacity and executive functioning (Mandarelli et al., Reference Mandarelli, Parmigiani, Tarsitani, Frati, Biondi and Ferracuti2012). This may suggest that executive functioning is a potentially useful target for treatment planning for patients who lack capacity, although some authors have challenged this approach (Ryba & Zapf, Reference Ryba and Zapf2011).

Finally, the assessment of capacity may also vary by the stage and type of the admission. Unsurprisingly, voluntary patients had lower incapacity rates compared to involuntary patients. Other authors (Curley et al., Reference Curley, Murphy, Plunkett and Kelly2019b) concluded that being involuntarily admitted was the strongest predictor of low MacCAT scores, i.e., low capacity. Patients were also more likely to lack capacity in the earlier stages of their admission compared to later, which is likely explained by improvement in their clinical symptoms following care and treatment.

Factors associated with the lack of capacity

This leads to the third question about psychiatric inpatients. Our meta-analysis found that incapacity was associated with worse psychiatric outcomes on all three measures, with large effect sizes. In order of strength, we found that the MMSE, GAF, and BPRS predicted binary clinical judgments of capacity. Given the variation in diagnoses and settings, this result is strong evidence of a link between psychiatric morbidity (including cognitive impairment) and capacity.

Our qualitative analysis provides additional context to these effects. Importantly, several diagnoses showed associations. Although diagnosis alone is therefore an insufficient guide to capacity, psychiatric symptoms have been associated with incapacity (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Ster, David, Szmukler, Hayward, Richardson and Hotopf2011), especially positive symptoms. The only types of psychopathologies that predicted better capacity were depression and anxiety symptoms (see figure 1 of Appendix 2). Although insight into mental illness and capacity to decide treatment are strongly associated, both depression and anxiety are also associated with better insight (Murri et al., Reference Murri, Amore, Calcagno, Respino, Marozzi, Masotti and Maj2016; Stefanopoulou, Lafuente, Saez Fonseca, & Huxley, Reference Stefanopoulou, Lafuente, Saez Fonseca and Huxley2009), which has been referred to as the ‘insight paradox’. In the subgroup of patients with a diagnosis of depression, insight is a poor guide to capacity. This suggests a need for more granular analysis of the relationship between self-awareness and capacity (van der Plas, David, & Fleming, Reference van der Plas, David and Fleming2019). On the other hand, it is important to point out that regular programmed activities and medication in hospital seems to improve patients' ability to make treatment decisions over time (Dornan et al., Reference Dornan, Kennedy, Garland, Rutledge and Kennedy2015), even if the intervention lasts only one month (Owen et al., Reference Owen, David, Richardon, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2009).

Conversely, most of the socio-demographic predictors were either weak or inconclusive. The only factor that was consistently related to incapacity was unemployment, which is perhaps unsurprising given the association with psychopathology. Black ethnicity was also associated with poorer odds of having capacity and regaining capacity in one study each. In one study, the effect became non-significant after controlling for three potential confounding variables, although this could also be explained by a reduction in statistical power (Aberson, Rodriguez, & Siegel, Reference Aberson, Rodriguez and Siegel2022). Further research is warranted to explore whether this ethnicity effect is consistent across samples, to better understand confounding and rater bias.

In light of these findings, we have provided some recommendations to be taken into account when assessing capacity in psychiatric patients:

− A good evaluation should include both quantitative and qualitative methods, considering aspects such as the person's personal values and cognitive factors. We do not recommend structured assessments alone. Interventions aimed at improving cognition, particularly executive function, could lead to improvements in capacity and should be researched.

− Providing briefer and more concise information relevant to the specific treatment may help patients to demonstrate capacity.

− It is possible to reliably evaluate capacity for treatment on admission to a psychiatric facility and to reassess capacity when the patient's symptomatology has stabilized.

Limitations

Heterogeneity is a clear limitation to our analyses. We found variation in the methods used to assess capacity, the type of treatment decision being assessed and the demographic, diagnostic and symptomatological profile of each sample. The latter two were especially problematic for our meta-analysis, because poor reporting of these variables reduced our ability to explain this heterogeneity using post-hoc analysis. These limitations are common in meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies (Ioannidis, Reference Ioannidis2008). Although moderate-to-large heterogeneity increases the likelihood of false negatives, all three analyses remained significant, which suggests a robust relationship between psychiatric morbidity and capacity. We were also unable to find enough comparable data on psychopathology subscales, therefore we only included generic psychopathology measures in our meta-analysis. Future studies could use an individual patient data meta-analysis (Cooper & Patall, Reference Cooper and Patall2009; Riley, Lambert, & Abo-Zaid, Reference Riley, Lambert and Abo-Zaid2010) to explore how these effects vary between subgroups and subscales.

Finally, previous studies have also noted that inter-rater disagreements are more likely when the patient's capacity is fluctuating or borderline (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Palmer, Appelbaum, Saks, Aarons and Jeste2007) and that these cases are among the most challenging to assess (Ariyo, McWilliams, David, & Owen, Reference Ariyo, McWilliams, David and Owen2021). The studies in our sample did not report sources of disagreements, therefore we are unable to determine to what extent fluctuating or borderline capacity had an impact on reliability. We recommend that future studies report more granular data on disagreement cases in order to facilitate more useful professional guidance. Nonetheless, as professionals generally agree on the capacity outcome in the majority of cases, this is unlikely to limit the wider generalizability of our findings, and our results ameliorate concerns that capacity assessment is subjective and unreliable.

Conclusions

We conclude that the assessment of mental capacity can be easily replicated, both through standardized methods and clinical interviews. Among the available samples, more than half of psychiatric inpatients were capable of making decisions regarding their treatment or hospitalization. However, this capability may vary based on the stage of admission, involuntary v. voluntary and the amount of information provided. The severity of psychopathology is strongly correlated with mental capacity but detailed psychopathological data remains limited. Data on sociodemographic associations with capacity are also limited, and potential associations with education and ethnicity warrant further investigation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000242.

Funding statement

This research is funded by the Wellcome Trust Collaborative Award in Humanities & Social Science [203376], made to G.O. as Principal Investigator in the Mental Health and Justice Project, and by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through project PI17/00113 and co-financed by the European Union. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None.