Media summary: Archaeolinguistics supports the ancestor of the Korean language reaching the Korean peninsula in association with millet farming in the Neolithic. A population decrease on the Korean peninsula after around 3000 BC appears to be part of a broader Late Neolithic decline recognized in many areas of Eurasia. Plague (Yersinia pestis) may have been one cause of this decline in Korea and Japan.

Introduction

The farming/language dispersal hypothesis proposes that demographic growth amongst early farmers led to population expansions from homeland regions. Linguistic change occurred not only through the geographical expansion of the languages of farmers but also by hunter–gatherer language shift (Bellwood & Renfrew, Reference Bellwood and Renfrew2002; Diamond & Bellwood, Reference Diamond and Bellwood2003). Based originally on analyses of Austronesian and Indo-European (Renfrew, Reference Renfrew1987; Bellwood, Reference Bellwood1991), evidence supporting farming/language dispersals has long been discussed for many other regions (e.g. Phillipson, Reference Phillipson1997; Diakonoff, Reference Diakonoff1998; Glover & Higham, Reference Glover, Higham and Harris1996; Bellwood & Renfrew, Reference Bellwood and Renfrew2002). Although Japonic has also been linked with a farming dispersal (Hudson, Reference Hudson1994, Reference Hudson1999; Lee & Hasegawa, Reference Lee and Hasegawa2011; Whitman, Reference Whitman2011), some scholars have noted that pastoralism and processes of elite dominance make the farming/language dispersal hypothesis difficult to apply to the north Eurasian languages classified as Altaic or – sensu Johanson and Robbeets (Reference Johanson, Robbeets, Johanson and Robbeets2010) – as Transeurasian (e.g. Renfrew, Reference Renfrew, Hall and Jarvie1992, pp. 30–32; Heggarty & Beresford-Jones, Reference Heggarty, Beresford-Jones and Smith2014).

Recently, however, archaeobotanical research identifying northeast China as a centre of millet domestication has enabled linguists to propose the West Liao basin as the Neolithic homeland of a Transeurasian language family (Robbeets, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2017a, Reference Robbeetsb, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2020). As part of this new work, the farming/language dispersal hypothesis has been systematically applied to the Korean peninsula for the first time through the suggestion that Proto-Macro-Koreanic arrived with millet cultivation around 3500 BC (Robbeets, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2017a, Reference Robbeetsb, Robbeets et al., Reference Robbeets, Janhunen, Savelyev, Korovina, Robbeets and Savelyev2020). Here, we provide a new analysis of the archaeological evidence used to associate millet farming dispersals with Proto-Macro-Koreanic before discussing linguistic data which support an early arrival of Proto-Macro-Koreanic on the peninsula.

Korean archaeology and ethno-linguistic origins: background

The farming/language dispersal hypothesis in Korea needs to be first placed in the context of broader discourse over the evolution of human society on the peninsula. Owing largely to the legacy of Japanese colonialism, migration and ethnicity have been controversial topics in Korean history and archaeology (Pai, Reference Pai1994, Reference Pai1999, Reference Pai2000; Nanta, Reference Nanta, Tschudin and Hamon2007; Kim, Reference Kim, Habu, Fawcett and Matsunaga2008; Park & Wee, Reference Park and Wee2016). During Japan's colonial rule (1910–1945), the ‘backwardness’ of Korean civilization was emphasized, as was the insistence that historical change had derived from outside influence. Colonial interpretations stressed the racial and cultural ‘inferiority’ of the Korean people and their dependence on outside stimuli (Kim, Reference Kim, Habu, Fawcett and Matsunaga2008, p. 124). At the same time, using linguistic as well as archaeological evidence, colonial scholars expounded the theory that the Korean and Japanese peoples shared a common ancestor in prehistory – the so-called Nissen dōsoron (Oguma, Reference Oguma2002, pp. 64–92). Research on Korean origins following independence has to be understood as a critique of this colonial discourse.

In the 1960s, archaeologist Jŏng-hak Kim made the influential argument that the Korean people were formed in the Bronze Age through the replacement of a Neolithic ‘Palaeo-Siberian’ (or ‘Palaeo-Asiatic’) population by an Altaic Tungusic-speaking tribe known as the Yemaek. This thesis became widely adopted in Korean archaeology (Park & Wee, Reference Park and Wee2016, p. 313; Pai, Reference Pai2000, pp. 79–80) and, in fact, in Korean society as a whole (Hong, Reference Hong2006, p. 23). As a result, it has been assumed that while the introduction of rice cultivation in the Bronze Age marked a major transition, the earlier cultivation of millets had resulted from small-scale cultural diffusion from northeast China (Kim, Reference Kim1986). The Neolithic was to be understood as the time of ‘indigenous Korean hunter–fisher–gatherers’ (Shin et al., 2013, p. 69). As an extension of this perspective, research on the adoption of farming has often emphasized regional and chronological variation across the peninsula (Kwak & Marwick Reference Kwak and Marwick2015; Bale, Reference Bale2017; Kwak, Reference Kwak2017; Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Kim and Lee2017; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Oh, Bang, Rha and Jeong2018).

The periodization and chronology used in the present paper are shown in Table 1. The term ‘Chulmun’ (also romanized as Jeulmun) is sometimes applied to the Neolithic as a whole but more properly refers to the Middle and Late phases. Chulmun or ‘comb-pattern’ was coined in 1930 by Japanese colonial archaeologist Ryōsaku Fujita on the basis of what he saw as similarities between Korean pottery and the Kammkeramik of northern Eurasia (Kim, Reference Kim and Pearson1978, p. 10). More recently, other styles of Neolithic pottery have also been identified. Currently, the earliest Korean ceramics are from Cheju island with reported dates as early as 9920 BC, although this pottery tradition is said to have flourished especially after 7600 BC (G.K. Lee et al., Reference Lee, Jang, Ko and Bang2019; Shoda et al., Reference Shoda, Lucquin, Ahn, Hwang and Craig2017). Appliqué yunggimun pottery, which may have been influenced by the Amur region, appears on the east coast of the peninsula in the sixth millennium BC (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012). Chulmun pottery associated with sedentary villages appears around 4000 BC or slightly earlier (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012). There is still no consensus on the origins of the Chulmun ceramic tradition, although links with Liaodong have been suggested (Xu, Reference Xu and Nelson1995).

Table 1. Korean archaeological chronology for the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Based on Bausch (Reference Bausch and Hodos2016) with modifications.

Hunter–gathering was a major element of the subsistence economy of Neolithic Korea. The practice of some form of Neolithic agriculture had long been raised as a possibility (Nelson, Reference Nelson1993), but new finds are continuing to transform the field (Bale, Reference Bale2001; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cho and Obata2019; Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Obata and Lee2020). Chenopodium sp., soybeans (Glycine max) and adzuki beans (Vigna angularis) may already have been grown by the Early Neolithic (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012, p. 76; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Cho and Obata2019; Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Obata and Lee2020). Broomcorn (Panicum miliaceum) and foxtail (Setaria italica) millets reached Korea by the fourth millennium BC (Lee, Reference Lee, Habu, Lape and Olsen2017a, Reference Lee and Hodosb). Following this, a new agricultural system with millets, rice (Oryza sativa), barley (Hordeum vulgare) and wheat (Triticum aestivum) developed in Korea by 1300 BC (Ahn, Reference Ahn2010; Kwak et al., Reference Kwak, Kim and Lee2017; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Wright, Hwang, Kim and Oh2019; Lee, Reference Lee2011, Reference Lee, Habu, Lape and Olsen2017a, Reference Lee and Hodosb). Although Japanese archaeologists had earlier suggested that rice had been introduced to Korea from Japan, by the 1970s it was accepted that rice had moved to the peninsula from northeast China (Kim, Reference Kim1982) and that Bronze Age agriculture spread from Korea to Japan after 1000 BC (Crawford, Reference Crawford, Habu, Lape and Olsen2018; de Boer et al., Reference de Boer, Yang, Kawagoe and Barnes2020; Li et al., Reference Li, Ning, Zhushchikhovskaya, Hudson and Robbeets2020; Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2014, Reference Miyamoto2016; Leipe et al., Reference Leipe, Long, Wagner, Goslar and Tarasov2020).

Working out a linguistic chronology for the Korean language is more challenging, because the written records for Korean are relatively late and, unlike archaeological evidence, linguistic evidence cannot be excavated from the ground. To explore the history of the language before it has been actually written down, linguists rely upon the comparison of Korean with other languages. In addition to identifying early borrowings, this allows them to infer unattested ancestral states of Korean, referred to as ‘proto-languages’, meaning the common source of all of the languages in a given family.

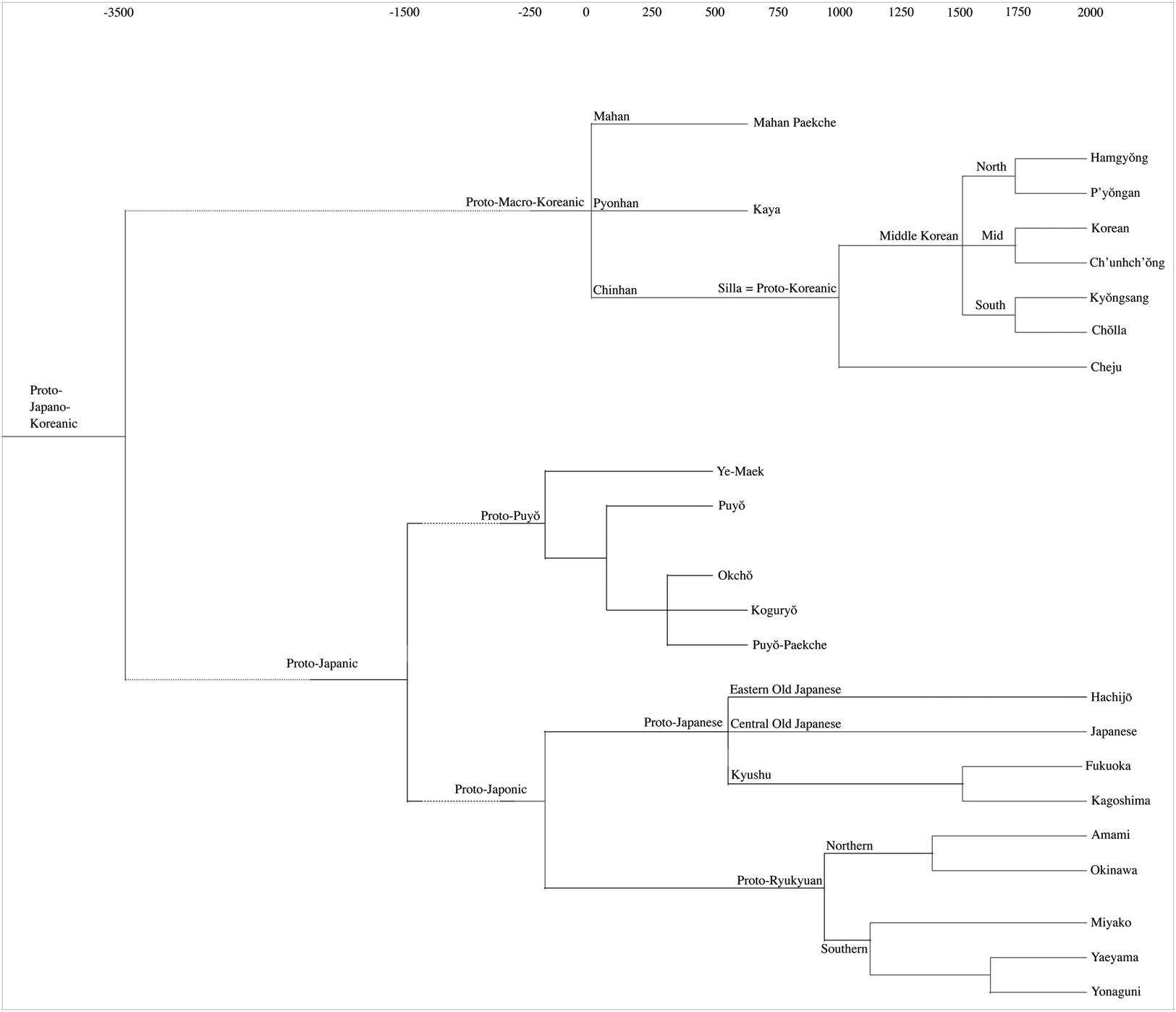

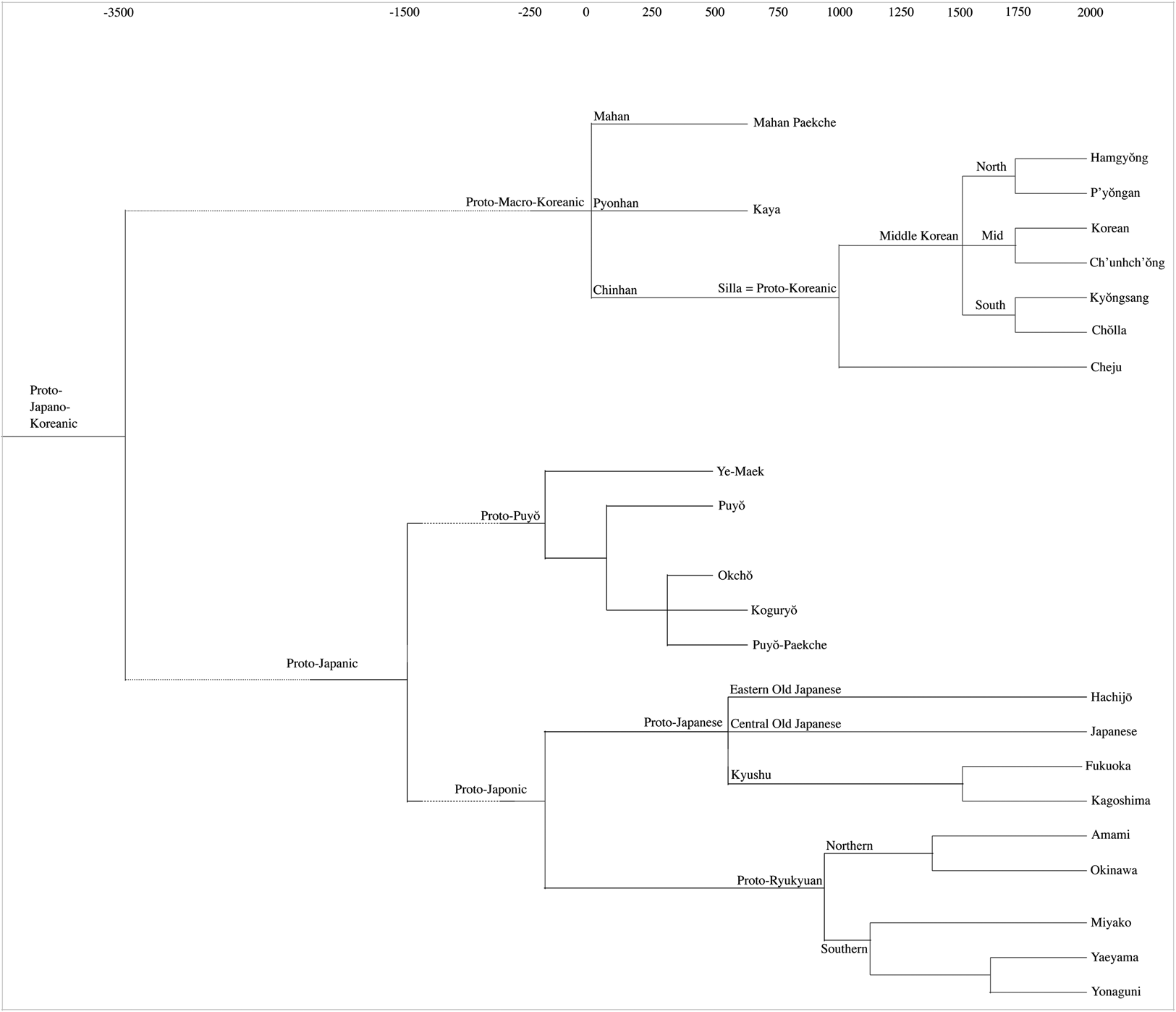

Three genealogical hypotheses about the origins of Korean are taken seriously today: the Transeurasian hypothesis (Ramstedt, Reference Ramstedt1949; Lee, Reference Lee1977; Martin, Reference Martin1996; Miller, Reference Miller1996; Starostin et al., Reference Starostin, Dybo and Mudrak2003; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets2005, Reference Robbeets2015), the hypothesis that only Korean and Japanese are related (Martin, Reference Martin1966, Reference Martin, Lamb and Mitchell1991; Whitman, Reference Whitman1985, Reference Whitman and Tranter2012; Unger, Reference Unger2009; Francis-Ratte, Reference Francis-Ratte2016), and the possibility that Korean is an isolated language like Ainu or Nivkh, without living relatives today (Janhunen, Reference Janhunen and Karttunen2010; Vovin, Reference Vovin2005). Proto-Transeurasian is the name of the ancestral language from which the Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Japanic and Koreanic languages are thought to descend, while Proto-Japano-Koreanic is a daughter of Proto-Transeurasian to which both the Japanic and Koreanic languages can be traced back. Before the separation of the two language families around 3500 BC, Proto-Japano-Koreanic was probably spoken along the Bohai coast and on the Liaodong peninsula (Unger, Reference Unger2014; Francis-Ratte, Reference Francis-Ratte2016; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2020; see Figure 1a). The term ‘Proto-Japanic’ refers to the ancestor of the historical continental varieties of the Japanese language as well as the varieties spoken on the Japanese Islands, while the label ‘Proto-Japonic’ is restricted to the branch of Japanic that is ancestral to Mainland Japanese and the Ryukyuan languages.

Figure 1. The linguistic landscape of the Korean peninsula in time and space. 1a: ca. 3500 BC Proto-Macro-Koreanic separates from Proto-Japanic on the Liaodong peninsula and enters the Korean peninsula; 1b: ca. 1500 BC Proto-Japanic enters the Korean peninsula from the Liaodong and Shandong peninsulas; 1c: ca. 300 AD Japanic Puyŏ languages are spread from the Liaodong peninsula to the Korean peninsula; the Macro-Koreanic Han languages, Paekche, Kaya and Silla are situated in the south of the Korean peninsula; pockets of Japanic languages are scattered among Paekche and Kaya languages.

We do not have any historical information about the languages spoken on the Korean peninsula until the third century AD, when Chinese dynastic chronicles start to leave some vague records of languages spoken at that time and how they related to each other. According to these sources, the local inhabitants were roughly divided into three ethno-linguistic groups: the Sushen, the Puyŏ and the Han. The Sushen people consisted of northern semi-nomadic tribes and are usually associated with the ancestors of the Jurchen, who spoke a Tungusic language (Janhunen, Reference Janhunen1996; Beckwith, Reference Beckwith2004). The Puyŏ were scattered over the Liaodong peninsula and the northern half of the Korean peninsula and included four groups, the Puyŏ proper, Koguryŏ, Okchŏ and Ye. Their language was probably more closely related to Japanese than to Korean (Beckwith, Reference Beckwith2004, Reference Beckwith2005). The Han – who are not to be confused with the Chinese Han – consisted of three related groups of people in the southern part of the Korean peninsula. In the Three Kingdoms period (AD 300–668), the Mahan in the west became Paekche, the Pyŏnhan in the Naktong River valley in the centre became Kaya, and the Chinhan in the east became Silla, each with their individual languages (Figure 1c). The Han languages are usually associated with various Koreanic languages (Lee and Ramsey, Reference Lee and Ramsey2011); their ancestor can be specified as ‘Proto-Macro-Koreanic’, even if many linguists use ‘Proto-Koreanic’ as a general term to refer to the entire period between the separation from Proto-Japanic and the break-up into the predecessors of contemporary varieties.

Nevertheless, as indicated by the green dots in Figure 1c, there must have been pockets of Japanic speech communities among the Koreanic languages. Chinese chronicles, such as the Hou Han Shu (the fifth century AD ‘History of the Later Han’), state that the Pyŏnhan people were close to the Wa, the ethnonym for inhabitants of the Japanese islands. Linguistically, the alleged presence of Japanic languages in Korea is confirmed by the historical Japanic toponyms, documented especially in the Mahan and Pyŏnhan regions (Bentley, Reference Bentley2000) and by a small number of words in the Nihon shoki which might be of Kaya origin (Kōno, Reference Kōno1987). Therefore, it seems likely that there were at least some Japanic languages among the Pyŏnhan and Mahan languages.

However, the Silla kingdom unified the Korean peninsula politically and linguistically in 668, erasing all pre-existing linguistic diversity. Owing to this unification, the contemporary Korean dialects cannot be traced back any deeper in time than the end of the first millennium AD. Thus, the separation of Proto-Koreanic into the predecessors of the contemporary dialects corresponds roughly to the time of the break-up of Silla Old Korean. Thus, similar to the distinction between Latin and Proto-Romance, Silla Old Korean is an – albeit very fragmentary – historically attested language, while Proto-Koreanic is the language reconstructed through the comparison of contemporary and historically well-attested varieties of Korean.

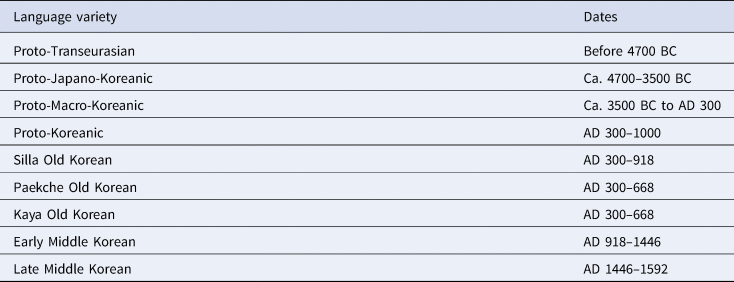

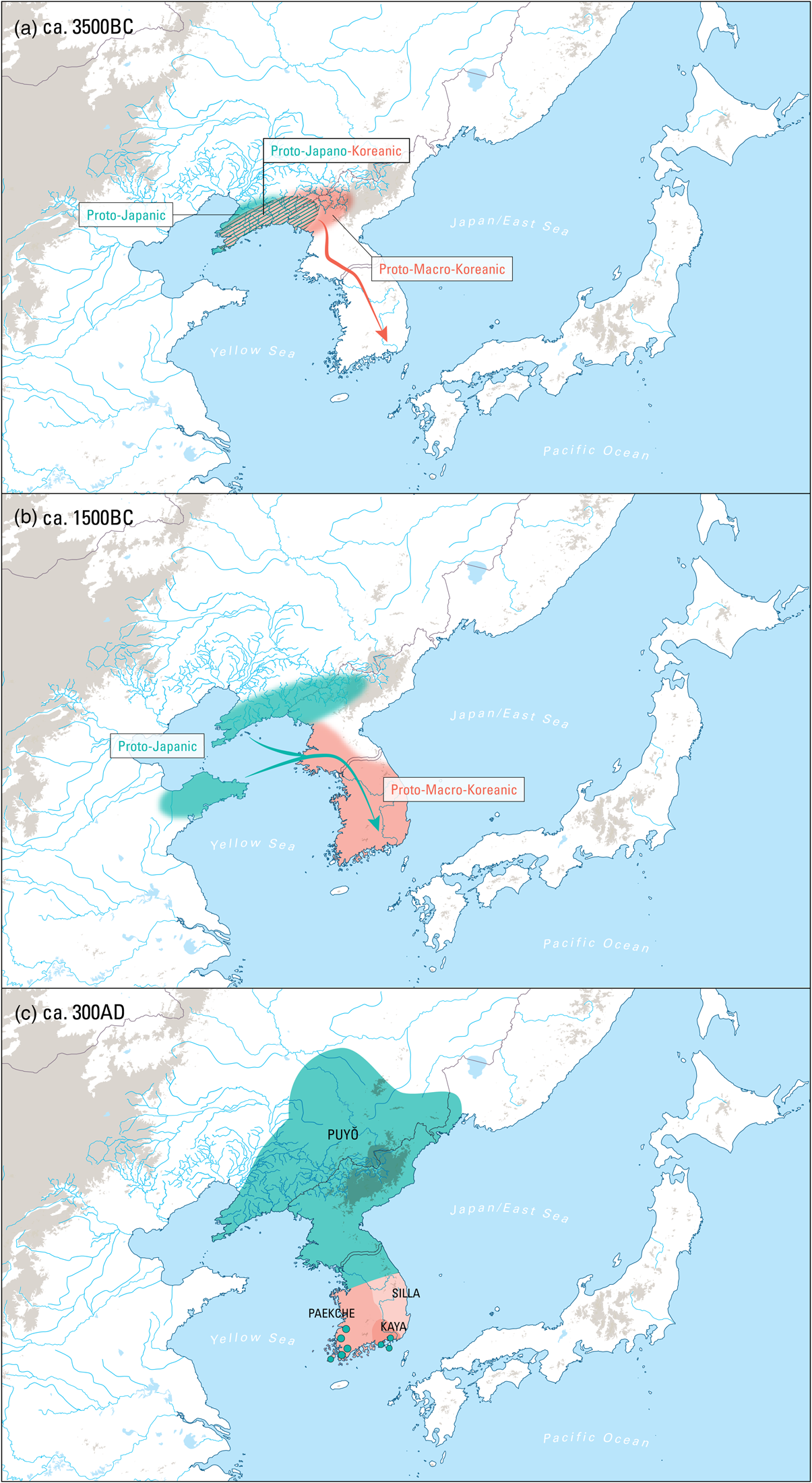

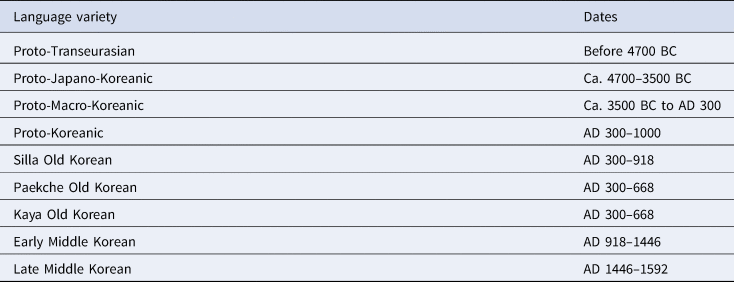

It is believed that the language of Silla was the direct ancestor of Middle and Contemporary Korean. Since the Old Silla and Old Paekche Korean material mainly consists of individual words and a few poems, and since the exact phonological value underlying the Chinese characters of Early Middle Korean records is unclear, it is not until Late Middle Korean, the language written down after the invention of the Korean script in 1446, that we get a thorough linguistic understanding of the Korean language. The linguistic periodization and chronology used in the present paper are shown in Table 2, while a classification of Japano-Koreanic is proposed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Classification of Japano-Koreanic based on classical comparative historical linguistic inferences (adapted from Robbeets, Reference Robbeets2015).

Table 2. Korean linguistic chronology

Koreanic and the farming/language dispersal hypothesis

Three common assumptions regarding the spread of millet farming in Neolithic Korea are relevant to the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. These assumptions are that millet cultivation was (a) not associated with major transformations in material culture or settlement patterns, (b) did not affect the continued primary importance of wild plants and marine resources and (c) did not lead to population increase. These observations are contrasted with the Korean Bronze Age (1300–400 BC), which is widely argued to be characterized by abrupt shifts in material culture, the replacement of hunter–gathering by rice farming, and by clear evidence for demographic growth. In the following, these arguments are discussed in turn.

Did millet farming spread to Korea through migration or diffusion?

Some archaeologists have argued that the archaeological record supports immigration into the Korean peninsula in the Bronze Age but not in association with the introduction of millet farming in the Neolithic (Ahn, Reference Ahn2010; Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2020). In this section we argue that evidence relating to sedentism, pottery, stone tools and weaving technology is, in fact, consistent with population movements into Korea in the fourth millennium BC.

Migrations have always been a controversial problem in archaeology owing to the methodological difficulties of identifying population movements from the archaeological record, as well as theoretical issues over the role of migration and ethnicity in historical change (Bellwood, Reference Bellwood2013; Burmeister, Reference Burmeister, Meller, Daim, Krause and Risch2017). Traditions of historiographic research also influence how scholars are predisposed to view continuity vs. discontinuity in the archaeological record. The relationship between material culture and ethnic and linguistic identity has been seen as a key issue. In archaeology, classical methods, such as those used by Rouse (Reference Rouse1986), attempt to link migrations with more or less sudden changes in archaeological sequences. Where evidence from biological anthropology and linguistics can be combined with archaeology, then a convincing argument can often be made for migration (Hudson, Reference Hudson1999). The difficulty is how to interpret cases without sudden breaks in the archaeological record or without biological evidence.

Ethnographic work by Leach (Reference Leach1954), Barth (Reference Barth1969) and others transformed the way we see ethnicity. No longer a fixed or ‘primordial’ identity, such research demonstrated that ethnicity is often used in a contextual or strategic fashion. Hodder (Reference Hodder1982) began the study of the implications of this understanding for material culture. Against this background, the farming/language dispersal hypothesis marked an important theoretical contribution to the archaeology of population movements in attempting to organize the previously rather undisciplined research on archaeology and language dispersals (Renfrew, Reference Renfrew, Hall and Jarvie1992). New work using ancient DNA has further transformed research, leaving little doubt that population movements did play an important role in Neolithic and later transitions to farming (Haak et al., Reference Haak, Balanovsky, Sanchez, Koshel, Zaporozhchenko and Adler2010; Isern et al., 2017; Gamba et al., Reference Gamba, Fernández, Tirado, Deguilloux, Pemonge, Utrilla, Edo and Arroyo-Pardo2012; Mathieson et al., Reference Mathieson, Lazaridis, Rohland, Mallick, Patterson, Roodenberg and Reich2015; Racimo et al., Reference Racimo, Woodbridge, Fyfe, Sikora, Sjögren, Kristiansen and Vander Linden2019; Shennan, Reference Shennan2018).

In Korea, the Middle Neolithic of the fourth millennium BC saw increasing sedentism, a process which seems to have spread from the central-west to the southern peninsula. Ahn et al. (Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015, p. 113) note that ‘Small-scale millet cultivation introduced from northern China seems to have been adopted by Neolithic hunter–gatherers almost simultaneously’ with this shift to sedentism. From the latter part of the Middle Neolithic, the presence of millet farming villages along rivers in the southern peninsula and on the eastern and southern coasts is noted by Shin et al. (Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012). Although Shin and colleagues see these as small, shifting settlements, Korean archaeologists such as Eun-Sook Song have argued that the expansion of Middle Neolithic culture across the southern part of the peninsula was a farming dispersal (discussed in Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012, p. 83). Millet cultivation and sedentism were associated with Chulmun comb-pattern ceramics, which also spread from the central-west zone across the southern peninsula (Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015; Lee, Reference Lee, Habu, Lape and Olsen2017a). The average size (volume) of pottery increases during this phase, suggesting an important role in the storage of food. Ahn et al. (Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015, p. 114) argue that the Chulmun culture ‘adopted small-scale millet cultivation through interacting with people in the Liaoning area in China’, but population movement is an equally reasonable explanation given that, as discussed below, other aspects of material culture also change at this time.

From west-central Korea, millet farming spread to the southern peninsula, not just with Chulmun pottery but in association with a range of stone tools such as grinding stones, pestles, sickles, waisted hoes, digging sticks and polished stone arrowheads (Choe & Bale, Reference Choe and Bale2002; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012; Miyamoto, Reference Miyamoto2014; Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015). With the exception of stone arrowheads, these are all tools that could reasonably be linked with agriculture, although the processing of nuts is of course another possibility for the grinding stones. As discussed in detail by Nelson et al. (Reference Nelson, Zhushchikhovskaya, Li, Hudson and Robbeets2020), textile technology provides further support for Neolithic farming dispersals in Northeast Asia, including Korea. Textile weaving, often using spindle whorls, became widespread in temperate climatic zones from the early Holocene (Gilligan, Reference Gilligan2019). The oldest spindle whorls in Korea have been reported from a few Early Neolithic sites possibly related to incipient millet cultivation (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Zhushchikhovskaya, Li, Hudson and Robbeets2020, pp. 11, 14). Yet an increase in the number and stylistic similarities of whorl finds from the Middle Neolithic is consistent with the linguistic evidence for a farming/language dispersal of Proto-Macro-Koreanic in the fourth millennium BC (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Zhushchikhovskaya, Li, Hudson and Robbeets2020).

The archaeological evidence summarized above does not constitute undeniable proof that a migration from northeast China into Korea occurred during the fourth millennium BC. The evidence is, however, broadly consistent with such an interpretation and with the expectations of the farming/language dispersal hypothesis.

How important was millet farming in Middle–Late Neolithic subsistence in Korea?

Many archaeologists have argued that Neolithic millet cultivation in Korea was an addition to a hunter–gathering economy but did not mark a major subsistence transformation. While some scholars have advised caution in light of the relative scarcity of archaeobotanical analyses (Crawford & Lee, Reference Crawford and Lee2003), this interpretation of the Neolithic economy is common (Bae et al., Reference Bae, Bae and Kim2013; Kim, Reference Kim2010, Reference Kim2014; Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2020; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012). However, the farming/language dispersal hypothesis does not require that farming form the only component of a subsistence economy. As discussed in the next section, even small-scale cultivation of millet might have been associated with language dispersal and shift, a conclusion which also appears warranted for the Primorye province of the Russian Far East (Li et al., Reference Li, Ning, Zhushchikhovskaya, Hudson and Robbeets2020).

The Korean peninsula packs different landscapes, such as forests, grasslands, mountains and freshwater and maritime environments, into a rather small area, a diversity that probably helped to maintain resilience at times of climate change. The fourth millennium BC has been analysed as a period when a colder and drier climate began around 3500 –3300 BC (Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015). While the exact chronology and impacts of such climate change will no doubt continue to be debated, adding millet agriculture to a variety of other subsistence strategies, including hunting, gathering and fishing, probably helped Chulmun populations expand into different environments and adapt to the changing climate. In Neolithic Northeast Asia, broad-spectrum subsistence was common in regions such as the West Liao basin and the southern Primorye, but this does not contradict the basic tenets of the farming/language dispersal hypothesis (Robbeets, Reference Robbeets2017b; Li et al., Reference Li, Ning, Zhushchikhovskaya, Hudson and Robbeets2020).

Isotope analyses have been used to argue that marine resources and wild plants, not millets, formed the main diet of the Chulmun people (Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2020, p. 8). However, many isotope studies are from coastal shell middens, where human bones are usually better preserved than in inland sites. Other research has identified regional variation in Neolithic isotope values from Korea (Choy et al., Reference Choy, An and Richards2012). Neolithic shell midden sites on the Korean peninsula, especially those from the eastern and southern coasts, demonstrate the importance of marine resources, including the specialized capture of large species such as sea lions, sharks and whales. However, this specialist use of marine resources does not necessarily contradict the importance of millet farming. In Japan, for example, the transition to agriculture in the first millennium BC was marked by the increased importance of specialized fishing, which was perhaps oriented towards trade with farmers (Hudson, Reference Hudson2019a; Takase, Reference Takase2020; cf. Ling et al., Reference Ling, Earle and Kristiansen2018).

Why did population decline in the Late Neolithic?

Recent studies of prehistoric demography on the Korean peninsula have been interpreted as evidence that population did not increase after the introduction of millet farming. The assumption here is that language shift requires a large initial influx of speakers; the possibility that Proto-Macro-Koreanic was introduced by a small number of speakers who later grew in number is not considered. The farming/language dispersal hypothesis proposes that agriculture enables populations to generate and store more food per area of land (Greenhill, Reference Greenhill, Bowern and Evans2015). Even if millet provided a relatively minor contribution to Neolithic diets in Korea, millet cultivation can still be expected to have increased the resilience of Neolithic populations, enabling them to obtain and store more food. Bettinger and Baumhoff (Reference Bettinger and Baumhoff1982) demonstrated that even small technological advantages can impact language shift, a phenomenon which probably also explains the expansion of Pama–Nyungan languages across Australia (Evans & Jones, Reference Evans, Jones, McConvell and Evans1997; Bouckaert et al., Reference Bouckaert, Bowern and Atkinson2018). The advantages accrued from millet cultivation in Neolithic Korea might have been sufficient for the spread of Proto-Macro-Koreanic.

Neolithic millet cultivation in Northeast Asia probably spread through extensive, low-intensity land use (Stevens & Fuller, Reference Stevens and Fuller2017; Qin & Fuller, Reference Qin, Fuller, Wu and Rolett2019), an ecological expectation consistent with archaeological evidence from the Primorye (Li et al., Reference Li, Ning, Zhushchikhovskaya, Hudson and Robbeets2020). Previous research in Korea has noted an ‘explosive’ increase in the number and size of Middle Neolithic settlements (Shin et al., Reference Shin, Rhee and Aikens2012, pp. 85–87). Ahn et al. (Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015, p. 135) write that, ‘After settlements with millet cultivation appeared in the early fourth millennium BC in central-western Korea, the population increased rapidly until c. 3500 cal BC. After that, settlements spread to other areas including the Geum [Kŭm] River valleys and central-east coast.’ Despite this earlier research, Kim and Park (Reference Kim and Park2020) emphasize that a population decline after the introduction of millet is evidence that a large migration into the Korean peninsula did not occur in the fourth millennium BC. However, Kim and Park's figure 1, adapted from Ahn et al. (Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015), places the arrival of millet at 3500 BC; if millet had reached Korea a century or two earlier – a possibility supported by Ahn et al. (Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015) and G.A. Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Cho and Obata2019) – then figure 1 would show a significant initial increase in population with millet farming. Kim and Park's figure 3 is based on an earlier study concluding that the introduction of millet to Korea was not associated with rapid population growth and that population actually declined after 2900 BC (Oh et al., Reference Oh, Conte, Kang, Kim and Hwang2017). While, as noted above, high population levels were not necessarily required for a shift to Proto-Macro-Koreanic, the demographic data summarized by Kim and Park are important to understanding language dispersals in Northeast Asia.

Recently, archaeology has brought the discontinuous nature of crop dispersals in Northeast Asia into sharper focus (Leipe et al., 2019; Stevens & Fuller, Reference Stevens and Fuller2017). Early millet expansions to Korea and the Primorye in the fourth millennium BC were followed by a period of more than 2500 years before farming spread from Korea to Kyushu, a distance of only 200 km. Another hiatus occurred before agriculture then spread to the lower Amur, Hokkaido and the Ryukyus from the late first to early second millennia AD (Crawford & Yoshizaki, Reference Crawford and Yoshizaki1987; Takamiya et al., Reference Takamiya, Hudson, Yonenobu, Kurozumi and Toizumi2015; Hudson, Reference Hudson, Finlayson and Warren2017; Leipe et al., Reference Leipe, Sergusheva, Müller, Spengler, Goslar, Kato and Tarasov2017). Previous research has linked these later dispersals to population movements but has rarely attempted to understand periods of stasis. In Korea, although there seems to have been an increase in population in the fourth millennium BC – presumably linked to the arrival of millet cultivation – after around 3000 BC a population decline seems to be well supported (Ahn et al., Reference Ahn, Kim and Hwang2015; Oh et al., Reference Oh, Conte, Kang, Kim and Hwang2017).

The resilience of early farming systems was often low, leading to ‘boom and bust’ cycles of both agriculture and language dispersal (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Meade, Venditti, Greenhill and Pagel2008; Stevens & Fuller, Reference Stevens and Fuller2012; Shennan et al., Reference Shennan, Downey, Timpson, Edinborough, Colledge, Kerig and Thomas2013; Colledge et al., Reference Colledge, Conolly, Crema and Shennan2019; Hudson, Reference Hudson2019b). A general Late Neolithic decline has been proposed for several regions of Eurasia, including Europe, China and Japan. Climate change, immigration of steppe pastoralists, trade and plague (Yersinia pestis) are possible causes of this decline (Kristiansen, Reference Kristiansen, Fowler, Harding and Hofman2015; Hosner et al., Reference Hosner, Wagner, Tarasov, Chen and Leipe2016; Rascovan et al., Reference Rascovan, Sjögren, Kristiansen, Nielsen, Willerslev, Desnues and Rasmussen2019). This decline was noticed very early in Japan where Koyama (1981) estimated that population levels in the third millennium BC dropped almost 40% across Kyushu, Shikoku and Honshu, and by almost 60% in central Honshu – rates comparable with the effects of the Black Death in Europe. Later research has supported the general trends identified by Koyama using site and pit house numbers as well as radiocarbon dates (Imamura, Reference Imamura1996, pp. 95–96; Hudson, Reference Hudson1999, p. 140; Yano, 2014; Crema et al., Reference Crema, Habu, Kobayashi and Madella2016; Crema & Kobayashi, Reference Crema and Kobayashi2020). The precise chronology is difficult but the most recent study concludes a starting date for the decline in the Kanto and Chubu regions of 4900 cal BP (Crema & Kobayashi, Reference Crema and Kobayashi2020).

Epidemic disease was suggested as a possible cause of the Late Neolithic decline in Japan by Oikawa and Koyama (1981) and Kidder (Reference Kidder1995, Reference Kidder2007). Recent findings of Y. pestis from Neolithic Sweden in an individual dated 5040–4867 BP (Rascovan et al., Reference Rascovan, Sjögren, Kristiansen, Nielsen, Willerslev, Desnues and Rasmussen2019) and in two individuals dated to 4556 and 4430 BP from Lake Baikal (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Spyrou, Karapetian, Shnaider, Radzevičiūte, Nägele and Krause2020) suggest the need to re-consider role of epidemic disease in the Late Neolithic decline in Northeast Asia, a point also made by Hosner et al. (Reference Hosner, Wagner, Tarasov, Chen and Leipe2016). As in Japan, the period from the third millennium BC in Korea is associated with settlement decentralization, broader-spectrum resource use and a move towards greater maritime mobilities. While the role of plague in these changes awaits confirmation from biomolecular analyses, the broader context would seem to be increased Bronze Age connectivities across Eurasia (Hudson et al., in press).

Linguistic evidence for the arrival of Macro-Koreanic: evaluating the hypotheses

Today most linguists (Janhunen, Reference Janhunen and Karttunen2010; Unger, Reference Unger2005; Whitman, Reference Whitman2011; Beckwith, Reference Beckwith2005; Francis-Ratte, Reference Francis-Ratte, Robbeets and Savelyev2017; Robbeets et al., Reference Robbeets, Janhunen, Savelyev, Korovina, Robbeets and Savelyev2020; Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2020) would agree that at least two different language families, Macro-Koreanic and Japanic, coexisted on the Korean peninsula in the first millennia BC and AD. Although these scholars agree to associate the introduction of rice agriculture to the Korean peninsula around 1300 BCE with the dispersal of Proto-Japanic, there is disagreement about the timing and the spread model of Proto-Macro-Koreanic. Figure 3 illustrates the different hypotheses for the arrival of Proto-Macro-Koreanic on the Korean peninsula.

Figure 3. Different hypotheses for the arrival of Proto-Macro-Koreanic on the Korean peninsula. (a) Proto-Macro-Koreanic arrived after Proto-Japanic from Liaodong and the Changbaishan region with the introduction of bronze daggers around 300 BC (Whitman Reference Whitman2011). (b) Proto-Macro-Koreanic arrived simultaneously with Proto-Japanic from the Liaodong and Shandong peninsulas with the introduction of rice agriculture around 1300 BC (Kim & Park, Reference Kim and Park2020). (c) Proto-Macro-Koreanic arrived before Proto-Japanic from the Liaodong peninsula with the introduction of millet agriculture around 3500 BC (Robbeets, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2017a, Reference Robbeetsb).

As shown in Figure 3c, some scholars proposed that Proto-Macro-Koreanic was spoken on the Korean peninsula from at least the second millennium BC, before the Bronze Age expansion to Japan in the Yayoi period (900 BC to AD 250; Janhunen, Reference Janhunen1999, Reference Janhunen2005), or before the advent of Proto-Japanic with Bronze Age Mumun culture (1300–400 BC; Vovin, Reference Vovin2005; Beckwith, Reference Beckwith2004, Reference Beckwith2005; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2017a, Reference Robbeetsb, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2020). Others suggested that it post-dated Proto-Japanic and arrived on the Korean peninsula between the third century BC and the fourth century AD (Unger, Reference Unger2005; Whitman, Reference Whitman2011; see Figure 3a). Among the supporters of an early arrival, Robbeets (Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2017a, Reference Robbeetsb) proposed a concrete spread model, linking it to the adoption of millet agriculture, while among the supporters of a late arrival, Whitman (Reference Whitman2011) associated it with the introduction of bronze daggers around 300 BC and Unger (Reference Unger2005) with the rise of the Silla kingdom in the fourth century AD.

Recently, Kim and Park (Reference Kim and Park2020) have rejected both Robbeets’ and Whitman's dispersal hypotheses for Proto-Macro-Koreanic, proposing two alternative scenarios, namely (a) that Proto-Macro-Koreanic arrived simultaneously with Proto-Japanic at the beginning of the Mumun period around 1300 BC or (b) that Proto-Japano-Koreanic arrived around 1300 BC before it separated into Japanic and Macro-Koreanic branches. The first scenario is illustrated in Figure 3b.

Both of these hypotheses pose serious problems. The first scenario associates the incoming Mumun farmers with two different ethno-linguistic groups of Macro-Koreanic and Japanic speakers. First, as Kim and Park (Reference Kim and Park2020, p. 14) themselves admit, this is difficult to reconcile with the observation that ‘Early Mumun material culture and technology were homogenous throughout the peninsula, making it difficult to distinguish the two groups.’

Second, the observation that the Puyŏ languages, spoken on the Liaodong peninsula and the northern half of the Korean peninsula by the beginning of the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25–220), were more closely related to Japanese than to Korean (Beckwith, Reference Beckwith2004, Reference Beckwith2005; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets and Breuker2007) suggests that the languages spoken in the Liaodong area after the separation of Proto-Japano-Koreanic were descendants of Japanic rather than of Macro-Koreanic. This implies that Japanic speakers remained in the Liaodong area, while Macro-Koreanic speakers moved and left the area after the separation of Proto-Japano-Koreanic in the fourth millennium BC (see Figure 1 and Table 2).

Third, there are a number of linguistic indications that the Macro-Koreanic speakers added rice technology to a pre-existing agricultural package through borrowing from Japanic speakers, who, in turn, borrowed rice terminology from their earlier continental neighbours in the Shandong area, including, among others, speakers of Para-Austronesian languages, i.e. sister languages of proto-Austronesian (Stevens & Fuller, Reference Stevens and Fuller2017; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets2017b). The repurposing of agricultural vocabulary as rice terminology in Korean, for instance, supports the idea that the speakers of Koreanic were already familiar with agriculture before adding rice to their agricultural package. For example, Proto-Koreanic *pap originally meant ‘any boiled cereal’ and Proto-Koreanic *pʌsal ‘hulled (of any grain); hulled corn of grain’, but later these meanings specified into ‘boiled rice’ and ‘hulled rice’, respectively (Francis-Ratte, Reference Francis-Ratte, Robbeets and Savelyev2017; Robbeets et al., Reference Robbeets, Janhunen, Savelyev, Korovina, Robbeets and Savelyev2020). The proposed borrowing of Proto-Koreanic terms such as *pye ‘(unhusked) rice’ and *pʌsal ‘hulled (of any grain); hulled corn of grain; hulled rice’ from Proto-Japanic *ip-i ‘cooked millet, steamed rice’ and *wasa-ra ‘early ripening (of any grain)’ (Vovin, Reference Vovin2016; Robbeets et al., Reference Robbeets, Janhunen, Savelyev, Korovina, Robbeets and Savelyev2020), and of Proto-Japanic terms such as *kəmai ‘dehusked rice’ and *usu ‘(rice and grain) mortar’ from Para-Austronesian *Semay ‘cooked rice’ and *lusuŋ ‘(rice) mortar’ (Sagart, Reference Sagart2011; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets2017b) is indicative of the direction of the diffusion, namely from Para-Austronesian into Japanic in the Shandong-Liaodong interaction sphere and, subsequently, from Japanic into Koreanic on the Korean peninsula.

And finally, there are traces of a pre-Nivkh substratum in Koreanic and of a pre-Ainu substratum in Japonic, but there is no evidence for Nivkh underlying features in Japonic that are unique in the sense that they are not characteristic for Ainu as well. Ainu and Nivkh represent marginal pockets of earlier languages whose lineages became isolated after the large-scale farming/language dispersals of various Transeurasian languages. Geography and linguistic distribution led to the assumption that at least some groups of hunter–gatherers on the Korean peninsula spoke ancestral varieties of Nivkh, while at least some hunter–gatherers on the Japanese islands spoke ancestral varieties of Ainu before the advent of agriculture. If the speakers of Japanic had arrived on the Korean peninsula prior to the speakers of Koreanic, we would expect more substratum interference from Nivkh in Japanic than in Koreanic. In reality, the opposite is true: we find indications of a pre-Nivkh substratum in Koreanic, while there are traces of a pre-Ainu substratum in Japonic, but even if there are proto-typical features that distinguish Nivkh from Ainu underlying in Koreanic, there are none in Japonic. For instance, the development of initial consonant clusters and three laryngeal contrast sets for stops in Koreanic may be due to substratum influence from pre-Nivkh, but these features are absent from Ainu as well as from Japonic. In contrast, features such as the occurrence of prefixing morphology in spite of the verb–final word order and the distinction between intentional and non-intentional action in certain verb affixes in Japonic may be due to substratum influence from pre-Ainu, but these features are absent from Nivkh as well as from Koreanic. These observations suggest that Macro-Koreanic – not Japanic – was the first language adopted by early hunter–gatherers on the Korean peninsula.

Kim and Park's second hypothesis, namely that the ancestral Proto-Japano-Koreanic language arrived with rice agriculture on the Korean peninsula around 1300 BC, is contradicted, first, by the absence of common rice vocabulary in Proto-Japano-Koreanic and second, by the early date proposed for the split between both families.

Although the agricultural vocabulary shared between Japonic and Koreanic is rather extensive with, for instance, a distinction between different terms for ‘field’, such as ‘field for cultivation’, ‘uncultivated field’ and ‘delimited plot for agriculture’, the languages do not have any rice vocabulary in common (Whitman, Reference Whitman2011; Robbeets, Reference Robbeets, Robbeets and Savelyev2020). This observation indicates that the separation between both language families must predate the introduction of rice farming and should thus not be situated on the Korean peninsula, but rather in northeast China. The ancestral speech community must have been located to the north of the cultures on the Yellow River and the Shandong peninsula that were familiar with both millet and rice agriculture from at least the fourth millennium BC onwards.

The early date proposed for the separation between both families corroborates a split pre-dating the introduction of rice agriculture. Contrary to Kim and Park's (Reference Kim and Park2020, p. 6) understanding that ‘While historical linguistics is interested in the timing and routes of language dispersal, it cannot directly address the temporality of these phenomena’, different linguistic dating techniques are used in the scholarly literature. For Proto-Japano-Koreanic, the different approaches converge on dating the break-up well before 1500 BC, to around the third millennium BC. Lexicostatistic dating estimates range from 4300 BC (Blažek & Schwarz, Reference Blažek and Schwarz2014, p. 88) to the fourth millennium BC (Starostin et al., Reference Starostin, Dybo and Mudrak2003, p. 236) to the third millennium BC (Dybo & Korovina, Reference Dybo and Korovina2019) to 2900 BC (Blažek & Schwarz, Reference Blažek and Schwarz2009); Bayesian methods infer a split at 1847 BC (Robbeets & Bouckaert, Reference Robbeets and Bouckaert2018) and cultural reconstruction (Robbeets et al., Reference Robbeets, Janhunen, Savelyev, Korovina, Robbeets and Savelyev2020) at 2600 BC.

Given the above linguistic indications, in our view the most parsimonious hypothesis is that Proto-Macro-Koreanic arrived on the Korean peninsula before Proto-Japanic, it was adopted by local hunter–gatherers speaking a language of Nivkh-like typology, it possessed agricultural vocabulary except for rice-related words, and it adopted rice terminology later in its history from incoming Japanic speakers.

Conclusions

In this paper we re-examined the archaeolinguistic evidence used to associate Neolithic millet farming dispersals with Proto-Macro-Koreanic. Archaeological evidence that millet spread from west-central to southern Korea in association with Chulmun (comb-pattern) pottery, agricultural stone tools and textile technology supports a farming dispersal in the fourth millennium BC. While hunting, gathering and fishing retained an important role in Neolithic subsistence, millet cultivation probably formed the economic advantage which enabled this dispersal. A population increase around the time of the introduction of millet farming has been reported by Korean scholars. A subsequent apparent decrease in population after around 3000 BC is not evidence against a Middle Neolithic arrival of Proto-Macro-Koreanic. Instead, this decrease appears to be part of a broader Late Neolithic decline found in many regions of Eurasia. Plague (Y. pestis) was suggested as one possible cause of this apparently simultaneous population decline in Korea and Japan.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthew Conte for information and advice on Korean archaeology and Ruth Mace and the three anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

Both authors designed the research and wrote the text.

Financial support

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 646612) granted to Martine Robbeets.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Data availability statement

All data used for this article can be found in the cited literature.