1. INTRODUCTION

Comprehensive approaches are needed to safeguard life on earth. A system-wide reorganization of economic, social, political, and technological factors is needed if we are to meet our goals for the sustainable use of nature.Footnote 1 Fostering transformative change, from current trends of biodiversity loss towards more sustainable and equitable pathways, requires cooperation between countries and across sectors.Footnote 2 There is an emerging literature which examines the potential (and limitations) of human rights law in this system-wide reorganization.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, further research is needed to understand the cross-fertilization between human rights law and specific multilateral environmental agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).Footnote 4

The CBD, which entered into force in 1993, has three main objectives: (i) the conservation of biodiversity; (ii) sustainable use of its components; and (iii) the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources.Footnote 5 The CBD has near-universal membership with 196 parties. As a framework convention, the CBD builds upon existing environmental agreements such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar).Footnote 6 While these multilateral environmental agreements specifically protect certain species or habitats, the CBD adopts a broad ecosystem approach to biodiversity conservation and sustainable use,Footnote 7 which makes the CBD one of the most far-reaching legal approaches to biodiversity. A wide range of guidelines have been developed to facilitate implementation of the CBD.Footnote 8 These guidelines target different focus areas while aiming to safeguard biodiversity and social-ecological issues in decision-making processes.

The CBD is a multilateral agreement which adopts decisions with commitments via the consensus of the parties; thus, the parties themselves negotiate and set commitments under the CBD. One example is the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, which contains the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets.Footnote 9 Parties agreed to implement this overarching international framework through national laws and policies. The existing monitoring mechanism for this is the submission to the CBD Secretariat of each country's National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plan (NBSAP).Footnote 10 Each country is obliged to conduct national planning to map its biodiversity targets to the Aichi Targets and report their progress to the CBD governing body: the Conference of the Parties (COP). As the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 ends, a new set of targets will be negotiated at the 15th meeting of the COP (CBD COP-15) under the post-2020 global biodiversity framework.Footnote 11

However, several assessments of the Aichi Targets show that parties have yet to comply fully with their self-determined commitments. In 2018, the CBD COP-14 acknowledged that very few parties had established targets in their NBSAPs with a level of ambition and scope commensurable with the Aichi Targets;Footnote 12 none of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets will be met fully.Footnote 13 Weak compliance with international environmental agreements has been identified as a global trend.Footnote 14 Unsurprisingly, the issue of compliance is a recurring topic in CBD COP discussions.Footnote 15

Concerns about the failure to comply with commitments to safeguard ecosystems have been raised not only at biodiversity fora, but also within the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council. The failure to protect biodiversity also has implications for human rights, as full enjoyment of human rights depends on a healthy and sustainable environment.Footnote 16 Healthy biodiversity and ecosystems represent core substantive elements of the human right to a healthy environment.Footnote 17 Compared with other areas of international law, the legal and policy landscape of human rights has evolved further as it has its own mechanisms for action, such as review mechanisms at international (see Table 3) and regional levels.Footnote 18 There is therefore good reason to examine human rights law mechanisms to understand how compliance within the CBD can be improved.

Moreover, ‘mainstreaming biodiversity’ – that is, integrating biodiversity issues into all policy sectors and cross-sectorally – is crucial for implementing the Convention. Several CBD articles refer to mainstreaming issues,Footnote 19 as well as adopted CBD COP decisions which specifically mainstream biodiversity in sectors spanning agriculture, forestry, tourism, and more.Footnote 20 The importance of mainstreaming was also highlighted by the former UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, who reported:

States are not meeting the standards they themselves have set for the protection of biodiversity …. Unless States effectively address the drivers of biodiversity loss, including by mainstreaming obligations of conservation and sustainable use into broader development policies and measures, the continuing degradation of biodiversity will undermine the enjoyment … of human rights.Footnote 21

Mainstreaming is often related to the wider ‘green economy’ concept, which emerged over recent decades to recognize the role of biodiversity and ecosystem services in economic activities.Footnote 22 An underlying assumption of the green economy is that economic growth is desirable for all countries and is possible to achieve within environmental limits. Although the green economy has helped in engaging the private sector to account for its dependence and impact on biodiversity,Footnote 23 the emphasis of the concept on the economic benefits of biodiversity has raised significant concerns.Footnote 24

In this article we address the following questions.Footnote 25 Firstly, what review mechanisms for fostering compliance are used in international human rights law and biodiversity agreements? Secondly, why have the Aichi Biodiversity Targets not been fulfilled, despite the fact that states set targets for themselves and several guidelines exist for their implementation? Thirdly, what insights can be gained from international human rights law to foster implementation and enforcement of the CBD? To improve implementation of the CBD in the forthcoming post-2020 global biodiversity framework, we need to understand why the Aichi Targets lack compliance pull. As the human rights regime has significant experience in promoting compliance,Footnote 26 analyzing the compliance strategies used within human rights law could help to address challenges faced by the CBD.

This article unfolds as follows. In Section 2 we outline key concepts often used in international environmental and human rights law: procedural and substantive obligations, implementation, compliance, and enforcement. We present, in Section 3, the methodology and methods used. Section 4 examines the compliance mechanisms used in human rights law and biodiversity agreements and the implementation of the CBD. In Section 5 we discuss the main challenges in implementing, complying with, and enforcing the CBD. We also discuss the extent to which the review mechanisms of international human rights law, with their various strategies for eliciting compliance, can help to improve CBD mechanisms. The concluding section argues for addressing the CBD compliance gap by prioritizing an enhanced review mechanism in the post-2020 global biodiversity framework, with insights from human rights law.

2. INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS LAW

2.1. Substantive and Procedural Obligations

As a clear link has been identified between environmental harm and human rights violations, states have obligations under human rights law to protect against such harm.Footnote 27 To understand the human rights obligations that apply in the biodiversity context, it is useful to explore the distinction between substantive and procedural obligationsFootnote 28 in international law. This conceptual distinction clarifies the types of commitment that states have set for themselves.

Substantive obligations define rights and duties, while procedural obligations entail processes for enforcing those rights and duties.Footnote 29 Substantive obligations enshrined in international law and national constitutions seek to sustain the environmental qualities conducive for a life in dignity, referring directly to the conditions for a healthy planet.Footnote 30 These obligations can help to address environmental concerns that affect human livelihoods, such as the rights to life, property, and health.Footnote 31

Procedural obligations sustain a society's ability to engage in public dialogueFootnote 32 and enable the effective governance of social-ecological systems. They refer to opportunities and abilities to exercise environment-related rights, and include duties to provide information, meaningful public participation in decision making, as well as access to justice and remedies.Footnote 33 The Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment, developed by a former UN Special Rapporteur, include both substantive obligations (such as Principle 11 on environmental standards) and procedural obligations (such as Principle 10 on access to effective remedies).Footnote 34

At least 155 UN member states have recognized the right to a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment through their national laws or their recognition of international agreements.Footnote 35 Linking social and ecological safeguards to existing human rights obligations provides an institutionalized pathway for claimants to seek enforcement of their rights.Footnote 36 The former Special Rapporteur on human rights and environment has recommended that the UN formally recognize the right to a healthy environment to help in addressing the gap between its legal recognition in national constitutions and effective implementation measures on the ground.Footnote 37

There has been an ongoing cross-fertilization of ideas between human rights and biodiversity domains.Footnote 38 In the biodiversity domain the CBD voluntary guidelines on safeguards call explicitly for considering international human rights treaties when designing biodiversity financing mechanisms.Footnote 39 In the human rights domain several international processes, such as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the UN Development Group, and the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, have emphasized the role of the CBD Akwé: Kon Guidelines.Footnote 40

Hence, there are good reasons to draw on human rights law when examining implementation of the CBD. Learning from existing human rights obligations and mechanisms can be used to assist parties in improving their compliance with CBD obligations. In particular, this article aims to examine the ways in which the CBD's own emerging peer-review mechanism can be developed on the basis of practices and lessons learnt from international human rights monitoring and review mechanisms.

2.2. Implementation, Compliance, and Enforcement

The CBD is an international treaty and its 196 parties all have expressed consent to be bound by this treaty.Footnote 41 Yet, the formal consent procedures of international treaties are not the only factor in achieving the CBD objectives. An interactional account of international law is relevant here in that it helps to understand the CBD in practice and contributes to building the foundations for legitimate international biodiversity governance.Footnote 42 This includes not just examining the CBD text, but also the principles and guidelines negotiated by CBD parties that are then adopted at CBD COPs. This interactional approach assumes a degree of flexibility for states to work out complex problems,Footnote 43 which is appropriate for environmental issues as the choice of biodiversity governance instruments should be tailored to the different economic and political contexts of states.Footnote 44 The global structure of the CBD promotes international cooperation, while emphasizing national implementation within state jurisdictions via a framework of general obligations for parties.Footnote 45

The terms ‘implementation’, ‘compliance’, and ‘enforcement’ are often used interchangeably in discourse, but these terms incorporate different concepts in agreements. Implementation of international agreements refers to the extent to which parties have translated agreed provisions into their legal and political systems.Footnote 46

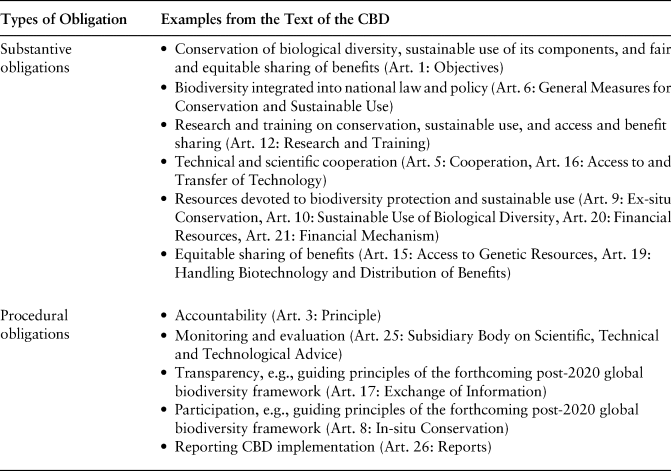

Compliance occurs when the ‘legal requirements of international agreements are met by the state parties to them’.Footnote 47 Various levels of compliance can exist with the same set of regulations;Footnote 48 it is therefore useful to distinguish between complying with procedural and substantive obligations when evaluating compliance,Footnote 49 as seen in the CBD context in Table 1. The Aichi Targets include mainly substantive obligations with which the parties should comply, although procedural dimensions are needed to operationalize such obligations. The main procedural obligations of parties are to create a NBSAP and to submit a national report every five years.Footnote 50 These two obligations are interconnected. The NBSAP reflects the sequence of steps that the CBD party intends to take to fulfil the objectives of the CBD and comply with its respective obligations. In their national reports parties describe the measures taken to implement their NBSAPs and progress towards the Aichi Targets.Footnote 51

Table 1 Distinction between Substantive and Procedural Obligations within the CBD

Source Adapted and modified from LePrestre (2002), n. 14 above.

To encourage compliance within international agreements, three main strategies are used: (i) positive incentives through administrative, financial, and technical assistance; (ii) sunshine methods, such as monitoring, transparency, and the participation of non-state actors; and (iii) negative incentives via sanctions and penalties.Footnote 52 Enforcement is part of the compliance process, referring to ‘coercive measures to induce compliance with obligations’.Footnote 53 While coercive measures are commonly associated with negative incentives, international environmental agreements usually rely on sunshine methods, including publishing information about infringements, in order to trigger social pressure from non-state actors.Footnote 54

The scholarly debate on what promotes compliance with international regulatory agreements has often been framed by two perspectives: enforcement and management.Footnote 55 Enforcement theorists stress a coercive strategy of monitoring and the threat of sanctions, whereas management theorists advocate a problem-solving approach of capacity building, rule interpretation, and transparency.Footnote 56 As monitoring can take many formsFootnote 57 it is used in both enforcement and management approaches, albeit with slightly different aims: to expose possible infringements within the former, and to increase transparency by facilitating coordination on treaty norms within the latter.Footnote 58

Although these two strategies tend to be portrayed as distinct alternatives, in practice they are complementary and mutually reinforcing.Footnote 59 Both strategies may also be more effective when combined.Footnote 60 One prominent example of complementarity is compliance building in the ozone regime, where both formal and informal bodies collaborated over problem solving through various managerial efforts of economic capacity building, technological assessment, and implementation review.Footnote 61 When faced with persistent failures to comply with regulatory commitments, institutions resorted to enforcement measures and threatened penalties. On a similar note, the decision to protect one-third of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia started as a collaborative learning process with fishers, which increased legitimacy for the ultimate coercive measures.Footnote 62

The distinction between procedural and substantive obligations helps to clarify the types of commitment that states have set for themselves under the CBD. Substantive obligations lay the groundwork for a country's intent to comply with biodiversity conservation, sustainable use, and benefit sharing, while procedural obligations help with building the capacity to comply. Specifically, this distinction contributes to frame the analysis of levels of compliance across CBD procedural and substantive obligations, as well as the reasons why the Aichi Biodiversity Targets have not been met in full. Conversely, distinguishing between implementation, compliance and enforcement enables us to determine where action can be taken to improve overall effectiveness in implementing CBD commitments in an integrated manner. Improvements within implementation alone will not be effective without both strong compliance and proper enforcement, and vice versa. Thus, using these concepts together provides an integrated approach to assess challenges faced by the CBD in implementing the Aichi Targets and identify insights from human rights law to support achievement of the CBD objectives.

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to improve compliance with the substantive and procedural obligations of the CBD, we need, firstly, to identify the challenges faced in implementing the CBD and determine the enforcement measures utilized. We used methods consisting of a content analysis of policy documents, multi-stakeholder interviews, and participant observation at CBD COP-14.

Addressing the first research question, we carried out a content analysis of review mechanisms from human rights law and biodiversity agreements. Secondary data sources were used, including CBD and UN documentation, scientific articles, and policy reports. While there have been advances in review mechanisms for upholding human rights law at the regional level,Footnote 63 our focus is the international level given that the CBD is a global treaty. At the international level the Human Rights Council is the intergovernmental body responsible for the protection of human rights. We examined the review mechanisms of international human rights law and identified two mechanisms as highly relevant to the CBD based on their similarities in terms of the focus on dialogue and procedural obligations: these mechanisms are (i) the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), and (ii) Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council. We contrasted these human rights mechanisms with an emerging review mechanism from the CBD, the Voluntary Peer Review (VPR).

The second research question with regard to compliance is more complex, and various qualitative methods were used to address this. Firstly, we analyzed CBD documentation and the fifth (or most recent) national reports of 21 countries in order to determine obstacles encountered in implementing the Aichi Targets.Footnote 64 The selection of national reports was based on criteria which included: (i) representation from the five CBD regional groups; (ii) countries visited by the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment; and (iii) participation in the CBD VPR. These criteria reflect the explorative nature of this research process.

We then interviewed biodiversity experts and conducted participant observation at CBD COP-14 in Sharm El-Sheikh (Egypt) in November 2018. The purpose was to gather information on the challenges in implementing CBD guidelines and principles. The CBD voluntary guidelines on safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanismsFootnote 65 served as an entry point to discuss more broadly how global biodiversity guidelines were interpreted at (sub)national scales to foster compliance. The interviews were semi-structuredFootnote 66 and based on an interview guide consisting of three general themes: (i) an example of a safeguard being implemented; (ii) the challenges faced in implementation; and (iii) how this process could be improved (for the interview questions see Supplementary Material, Box S1, available online only).

Snowball sampling was used to identify interviewees, beginning with previous participants of multi-actor dialogues on biodiversity and human rights, and safeguards in biodiversity financing mechanisms.Footnote 67 The respondents selected were experts in biodiversity and human rights issues spanning country delegates, international organizations, civil society organizations (CSOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), independent consultants, youth representatives, and Indigenous groups. Care was taken to ensure representation from the five CBD regional groups so that the respondents’ cumulative experiences would reflect geographical diversity. Eighteen people were interviewed in total, with each interview lasting between 20 and 40 minutes. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded thematically,Footnote 68 using qualitative data analysis software (Atlas.ti).

Certain limitations are associated with this methodology, such as the potential for bias from snowball sampling and the number of national reports examined. Nevertheless, the various qualitative methods used enabled an exploratory approach and triangulation of results, which is especially important in human rights research with empirical work.Footnote 69

4. THE INTERSECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND BIODIVERSITY LAW

4.1. Compliance Mechanisms in Human Rights Law and in Biodiversity Agreements

The analysis covers three review mechanisms in human rights law and biodiversity agreements: (i) the UPR and (ii) Special Procedures, both conducted by the Human Rights Council, and (iii) the CBD VPR (see Table 2 below).

Table 2 Review Mechanisms of the Human Rights Council and the CBD, with their Contributions to and Limitations in Supporting Compliance

Human Rights Council: UPR

Established in 2006, the UPR aims to ‘undertake a universal periodic review … of the fulfilment by each State of its human rights obligations and commitments’.Footnote 70 During each four-and-a-half-year review cycle, all UN member states have their human rights records reviewed. The reviews are conducted by the UPR working group, which consists of members of the Human Rights Council. Council members are elected by the UN General Assembly through a secret ballot. Membership is based on an equitable geographical distribution (African states hold 13 seats, Eastern European states hold 6 seats, and so on).

Each state review is conducted by three states drawn from other members of the Human Rights Council. Reviews are based on a national report of the human rights record provided by the state, a compilation of UN documentation from independent experts, and a stakeholder report from NGOs (the so-called ‘shadow report’). This collaboration has led to governments recognizing the role of CSOs in providing input to the human rights agenda.Footnote 71 Based on these three documents, the Council members engage in an interactive dialogue and assessment of the country under review to provide recommendations for improvement.

The UPR process emphasizes bilateral, state-to-state relations.Footnote 72 The state under review decides which recommendations to accept or reject, and is obliged to take action. In the subsequent review states report back on their progress (or lack thereof). If necessary, the Council will address cases where states do not respond to the recommendations. States’ human rights records are reviewed by other states rather than independent human rights experts.Footnote 73 This peer review process highlights the political nature of the UPR, which mixes both enforcement and managerial approaches to human rights implementation.Footnote 74

However, one challenge of the UPR is the significant time constraint in reviewing states during the Working Group reviews.Footnote 75 Each state review is around two to three minutes, which may turn what should be ‘a dynamic space for peer-to-peer debate and exchange into a stale forum of rushed and often unconnected monologues’.Footnote 76

While there is scope for improvement, the UPR provides an innovative space for countries to criticize each other's human rights record constructively and share lessons learnt. It also appears to have a positive impact on human rights at the country level.Footnote 77 The self-assessment requires governments to coordinate their ministries to write the national reports, which makes civil servants more aware of domestic human rights issues and increases their sense of ownership of the process.Footnote 78 Furthermore, the dialogue among states has a media presence and is streamed online, which increases transparency and puts public pressure on governments.

Human Rights Council: Special Procedures

The Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council are conducted by independent experts with mandates to report and advise on human rights from a thematic or country-specific perspective. They can be either individuals (namely, the Special Rapporteur) or a working group of five members, one from each UN regional grouping. There are currently 44 thematic and 12 country mandates.Footnote 79

Special Procedures act on alleged violations by sending communications to states, undertaking fact-finding missions to a country, elaborating on human rights norms, and raising public awareness. During country visits Special Procedure representatives assess the human rights situation and meet with government institutions, CSOs, victims, and other stakeholders. After the mission they report their findings to the Human Rights Council and UN General Assembly. In these sessions the visited country may respond while other countries and CSOs may comment.

The flexible nature of mandates has allowed Special Rapporteurs to respond to changing needs in specific problem areas.Footnote 80 One outcome from a Special Rapporteur communication involves the case of the Sengwer people in Kenya, who faced forced evictions in the wake of a conservation project funded by the European Union (EU). This case was elevated internationally as the Special Rapporteur appealed to the Kenyan authorities and other involved international organizations to halt the evictions, which led to the EU suspending the project funding.Footnote 81 Moreover, freedom of movement during country visits enables Special Rapporteurs to draw attention to specific violations, such as in Madagascar where conflict occurred arising from a mining permit being issued without consulting local communities.Footnote 82

Conversely, flexible mandates make it difficult to assess the impact of Special Procedures. Some impacts are visible and short-term, such as an appeal to a state to release environmental defenders being held on unfounded criminal charges.Footnote 83 Longer-term impacts may not be easily visible, such as recommendations to enhance judicial independence.Footnote 84 Additionally, mechanisms to track how states have responded to recommendations are yet to be institutionalized; Special Procedures have limited resources to engage in repeated visits or communications.Footnote 85

Nevertheless, Special Procedures have been described by a former UN Secretary-General as the ‘crown jewel’ of the human rights system.Footnote 86 They play a unique role as an entry point for the public into the larger UN human rights system spanning treaty bodies, political resolutions, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).Footnote 87 Special Procedures also shape international soft law norms by elaborating on a legal framework for human rights. For example, a former Special Rapporteur established the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, which several states then integrated into national legislation.Footnote 88

CBD: VPR

While certain agreements under the CBD – such as the Cartagena ProtocolFootnote 89 and the Nagoya ProtocolFootnote 90 – have their own compliance committees, there is no overarching compliance mechanism to monitor state-level implementation of the Convention.Footnote 91 The CBD COP does not review individual national reports, but rather draws conclusions based on the CBD Secretariat's synthesis of these reports.Footnote 92 Current evaluations focus on report submission and quantitative analysis of overall developments rather than conducting a qualitative analysis of the contents of the report.Footnote 93 This highlights a significant limitation of current CBD reporting processes: there is no established mechanism yet for evaluating each state's self-assessment.

One emerging review mechanism in the CBD context is the VPR of NBSAPs, which is currently in its pilot phase. In 2014 the Executive Secretary proposed a peer review process, drawing from existing international review processes including the Human Rights Council UPR, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's Environmental Performance Reviews, and the UN Climate Change national reviews.Footnote 94

The VPR is the only established mechanism under the CBD in which a party's implementation is reviewed, with the objective of helping to improve the individual and collective capacities of parties. A peer review team of biodiversity experts conducts a desk study of the national reports and the NBSAP, as well as a country visit to interview government institutions and local stakeholders. Civil society engagement is limited to a consultation during the country visits, and the list of local stakeholders is agreed beforehand between a national coordinator and the CBD Secretariat.Footnote 95 The review team then produces a report with recommendations, which is sent to the reviewed party for response.Footnote 96

Parties are invited to volunteer for review. Ethiopia, India, Montenegro, Sri Lanka, and Uganda have participated thus far.Footnote 97 Although the VPR is dependent on willingness to participate, information disclosed throughout the process enables a sharing of experiences with all CBD parties. The VPR does not have an avenue for the behaviour of an individual state to be discussed openly by other states, which may reduce barriers to participation.Footnote 98

The strengths and limitations of each review mechanism are summarized in Table 2.

From an overview of the mechanisms, it is apparent that a mix of strategies is used to support compliance. Compliance strategies emphasize cooperation rather than confrontation, focusing on repair and results rather than coercion.Footnote 99 We analyzed each review mechanism to identify compliance strategies and compare them in Table 3.

Table 3 Comparison of Compliance Strategies Used in Human Rights Council and CBD Review Mechanisms

All three review mechanisms enable the universal involvement of members and offer opportunities for peer learning. We found that the UPR has the most comprehensive approach, with formal cycles to facilitate follow-up on recommendations, and civil society able to engage critically and independently through shadow reports. However, the peer review is not conducted by thematic experts and the process may be subject to international diplomacy. Special Procedures benefit from a flexible mandate, with independent experts able to respond to changing needs in specific problem areas and to engage independently with civil society. Certain elements of human rights review mechanisms were emulated in the VPR, such as self-assessment and peer review performed by thematic experts. As the VPR is still at the pilot stage, its current distance from diplomatic exchanges and controlled civil society engagement may be strategic moves to encourage state participation.

4.2. Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity

CBD documentation and national reports

Almost all of the parties to the CBD (97%) are in compliance with their procedural obligation of developing a NBSAP and submitting national reports.Footnote 100 Implementing substantive obligations, however, is more difficult. The CBD COP-14 Secretariat assessments reported that a limited number of parties have fully implemented their NBSAPs into cross-sectoral policies. The results of the fifth national reports assessments indicated some progress, although at an insufficient rate: more than half of the parties are not on track to comply with any given Aichi Target.Footnote 101 Many national reports contain no information to assess progress on several targets. For instance, Target 10 on minimizing anthropogenic pressures on ecosystems vulnerable to climate change had the least amount of information: approximately 32% of national reports had no information.Footnote 102

Our analysis of 21 national reports identified the following main obstacles faced in implementing the Aichi Targets (for detailed excerpts see Supplementary Material, Table S1, available online only):

• Poor ecological monitoring with insufficient biodiversity data

Half of the national reports (11) – including those of Egypt, Mongolia, and the Seychelles – noted the poor documentation status on existing quality of habitats or species.Footnote 103 This is a major deficit because countries are not able to improve the conservation status or evaluate policy outcomes without a prior assessment of the situation.Footnote 104 Certain NBSAPs (for example, those of Brazil and Sri Lanka) have no defined biodiversity indicators for measuring progress.Footnote 105

• Lack of institutional capacity

More than half of the national reports assessed (14) – including those of Ethiopia, Fiji, Lao People's Democratic Republic (PDR), and Montenegro – cited a lack of institutional capacity to implement environmental policies.Footnote 106 Limited human resources and financial support were identified as obstacles by countries across all income groups. Some key difficulties were coordination among government agencies and the distribution of responsibilities between national and subnational levels. In Malaysia, for example, implementation duties were not delegated to relevant agencies and had no timeline, resulting in a lack of accountability.Footnote 107 In South Sudan, biodiversity management (forest governance and land ownership) is a shared responsibility between national and state governments, which led to a lack of ownership.Footnote 108

• Difficulty in integrating biodiversity policies into sectors

Integrating environmental and biodiversity issues into sectoral policies is a challenge listed in several national reports (5). Both Sri Lanka and Norway reported that biodiversity concerns are not adequately integrated into priority areas of development sectors such as mining, housing, and infrastructure.Footnote 109 In Sweden, targeting environmental performance in agricultural and forestry sectors has been a struggle, requiring consistent analyses, as a result of a government imperative of maintaining flexibility to develop individual solutions without raising administrative burdens.Footnote 110 In South Africa, the institutional changes needed to effectively mainstream biodiversity into sectors have been estimated to take at least 7 to 10 years, which requires long-term vision and commitment beyond the average lifetime of projects.Footnote 111

Multi-stakeholder interviews at CBD COP-14 and opportunities to learn from review mechanisms

The guidelines and principles developed under the CBD aim to influence the conduct of its parties and non-state actors. On the basis of the multi-stakeholder interviews at CBD COP-14, we identified four main compliance challenges. We then suggested how existing biodiversity and human rights review mechanisms could be developed in response to each challenge, as follows.

• Difficulties in establishing biodiversity metrics for monitoring and review

Several respondents (6) highlighted that the lack of consensus on universal metrics for biodiversity complicates the quantification of outcomes. The breadth, depth, and locational elements of biodiversity make it challenging to establish metrics that can be consistently quantified across scales. As described by respondents:

There are no easy, clear metrics for companies to determine their impact on biodiversity. Even within the conservation community, we don't have a consensus yet on how to quantify impacts.Footnote 112

Enhancing environmental mainstreaming has positive outcomes but it is difficult to assess if you haven't established indicators and a sound baseline in the first place.Footnote 113

Thus, biodiversity baselines are important for adequate outcome evaluation. Monitoring ecological outcomes is a common difficulty in conservation initiatives; goals are often vaguely formulated without quantitative targets or an allocated time frame.Footnote 114 Without clearly defined indicators in the policy design, further challenges will arise at the monitoring and compliance stages. One respondent stated: ‘With biodiversity, there is a big risk that the baseline is not clear. We have already degraded situations being taken as the baseline, which should instead be a natural ecosystem’.Footnote 115

All CBD parties face the same challenge of specifying indicators for measuring progress towards the Aichi Targets. The knowledge exchange facilitated through the VPR can help to address this. The VPR assesses whether the party's NBSAP has national targets, indicators, associated baseline data, and if national targets are mapped onto global biodiversity targets.Footnote 116

To help to address the insufficient monitoring of outcomes, civil society could be engaged in collecting ecological data. The UPR supports civil society involvement by inviting written submissions from the public based on general guidelines.Footnote 117 Similar initiatives, such as citizen science, have also encouraged public participation in ecological monitoring, where data can be collected from local to global scales.Footnote 118

• Slow uptake of CBD guidelines in national legislation and policies

Despite the substantive obligations imposed on parties to protect biodiversity, there has been a slow uptake in incorporating CBD guidelines and biodiversity targets into national policies. Few parties have used their NBSAPs to integrate biodiversity into broader policies and planning processes.Footnote 119 Many respondents (8) expressed a need to clarify the guidelines, such as the CBD voluntary guidelines on safeguards, for a more consistent application:

It's important to see how CBD provisions are translated into national legislative and regulatory frameworks. There tend to be gaps between the CBD, the national legal framework, and what is legitimate for local communities whom are often not reflected in the law.Footnote 120

Safeguards are weakened by the fact that loan conditions are often temporal, so when that ends there are few ways to drive compliance. That's where the CBD can play an important role, assuming that governments take those recommendations and integrate them into their own policies.Footnote 121

We need to clarify what safeguards mean and have a more universal standard. It's about the guidance and how that is interpreted.Footnote 122

Several respondents (7) also indicated a lack of appropriate negative incentives within the CBD. Although flexible approaches allow for innovation, some respondents were in favour of stricter consequences. One respondent stated: ‘There is very little information being shared on how safeguards have been implemented or whether it [the CBD COP decision] is effective. There are limited consequences for not complying with CBD decisions’.Footnote 123

To address these shortcomings and encourage state accountability, compliance strategies similar to those featuring in human rights review mechanisms could be incorporated in the CBD. For example, one key feature of peer review systems is mutual learning. The UPR enables states to review each other's records and engage in a collective dialogue. This is bound to generate learning relevant within their own national context as parties may face similar challenges. Moreover, Special Procedures conduct thematic studies to evaluate the implementation of domestic laws and international standards. They can deliver comments to states on the adequacy of national legislation and policy development relating to human rights standards.Footnote 124 In addition, review mechanisms that engage civil society can help to advance national implementation as CSOs can provide specific, timely, and solution-oriented input to governments.Footnote 125

• Inconsistent biodiversity policy integration

Social and environmental safeguards are commonly associated with infrastructure development projects that either require environmental impact assessments or are funded by international organizations.Footnote 126 Some respondents (5) remarked on the inconsistent application of biodiversity policies across sectors and called for a wider application of safeguards:

We need a massive expansion of existing safeguards into any business transaction and across many sectors. Any company listed on the stock exchange should have safeguards in place and disclose their biodiversity impact.Footnote 127

Safeguards need to be embedded within the project design for all sectors: agricultural, road and infrastructure, housing, even tourism. Instead of one set of safeguards that cuts across industries, we need tailored social and environmental safeguards for each and every sector.Footnote 128

I'm not sure how much of what comes out of the CBD is actually then integrated into regulatory policies. It's fine that you have environment ministries coming here [CBD-COP14], but they aren't the ones that have real effective control over the major projects like mining, oil and gas, and infrastructure. Are the agreements made in the CBD being transferred over into relevant regulatory policies and sectors?Footnote 129

Integrating biodiversity policies across sectors, or mainstreaming, is a specific issue targeted by the CBD VPR. The desk study examined environmental policy integration, where the review team identified policies that integrate biodiversity into sectoral plans and suggested possible synergies with other conventions.Footnote 130 From the pilot VPRs, parties were provided with recommendations to improve mainstreaming efforts, such as synchronizing Ethiopia's NBSAP with the country's new national development strategy.Footnote 131 In India, the VPR team recognized the country's decentralized governance system and recommended that each state should develop its own State Biodiversity Plan from the NBSAP.

Furthermore, the thematic studies produced by Special Procedures enable specific knowledge generation. A former UN Special Rapporteur on the right to development held regional multi-stakeholder consultations to identify good practices. One outcome from these consultations was the need for environmental and human rights impact assessments to be conducted in transboundary development projects. The Special Rapporteur has since called for states to set safeguards that hold financial institutions accountable to international legal standards.Footnote 132

• Questionable opportunities for effective and meaningful public participation

The challenge of ensuring effective and meaningful public participation, particularly with Indigenous and local communities, was highlighted by two-thirds of respondents (12). Several respondents (6) described a lack of consideration for power asymmetries underlying the participation process, which influences the ability of actors to express their views freely:

We should involve Indigenous and local communities early in the process so they can discuss if the proposed policy would benefit them or whether other types of engagements would be preferred.Footnote 133

It's not only about appointing one person from a community or NGO in the consultation process. It's about making sure that they actually represent the stakeholders.Footnote 134

Many communities have never had to deal with this [development project] before. There's no funding source to help them pay for technical and legal expertise to guide them, to know what to ask for during the resettlement process.Footnote 135

There is often a lack of attention for power imbalances, local communities are being invited to participate in a situation where they do not totally feel comfortable to respond. There is little analysis about incentives built into consultation processes that can create a big disincentive for people to freely express their views. Power, disincentives, and financial dependencies are often overlooked.Footnote 136

Some respondents (3) also stressed the importance of integrating gender perspectives. One respondent described:

We conducted a financial inclusion programme to improve the livelihoods of a community that was living within a protected area and dependent on tourism as their main source of income. We began by communicating with the community, by having meetings with women and tribe leaders. Based on the needs of the community, we decided to focus the intervention on women, to help them lend money to each other to start businesses. The aim is to create a sustainable source of income generation and build social capital.Footnote 137

Issues such as the timing of engaging stakeholders, access to information, and gender considerations can affect the quality of public participation. Local people and communities often do not have the technical or legal expertise to navigate the decision-making process, especially when resettlement issues are involved.Footnote 138 States have the procedural obligation to facilitate effective and meaningful participation in environmental decision making, as well as to provide access to remedies for harm.Footnote 139

Connecting the domains of human rights and biodiversity creates additional tools to implement and enforce the CBD. One respondent described how their organization challenged a development project with serious environmental and social impacts by using human rights and biodiversity mechanisms to build a legal case, specifically, by leveraging the UPR:

There was a destructive dam being built in [Country X] financed by [Government Y] that would imply the extinction of an endemic bird species. To stop the project, we turned to the human rights argument. There are Indigenous peoples in the area, and their rights of free, prior, and informed consent were not respected, so we took it to the Human Rights Commission, since the UN was evaluating Y's human rights record that year in the Universal Periodic Review. We took that opportunity to express our concerns of not complying with the rights of Indigenous peoples there.Footnote 140

These combined efforts from the respondent's organization helped to raise international attention; the country's judiciary ordered a public hearing on the environmental impact assessment.Footnote 141 The project has since been delayed, pending the judicial process. By utilizing international legal instruments from both domains, a stronger argument was built to highlight the negative impacts of the project on people and biodiversity.

Hence, facilitating the active participation of CSOs, Indigenous peoples, and local communities is a strategy for enhancing compliance. It is in the stakeholder's self-interest to safeguard social, and sometimes ecological, outcomes. This participation can be improved by including some of the following procedures. In the VPR under the CBD the peer review team assesses public participation and stakeholder engagement in the NBSAP and its implementation.Footnote 142 On this basis, Montenegro's VPR recommended improving public awareness by targeting youth engagement through the Global Youth Biodiversity Network.Footnote 143

Both the UPR and Special Procedures aim to address power asymmetries by actively facilitating civil society participation and involving participants on their own terms. The UPR affords space for dissenting views through the shadow reports, which was also highlighted in our interviews.Footnote 144 In Special Procedures, rapporteurs have freedom of movement to meet directly with civil society and pursue specific cases. Their physical presence provides victims with an enhanced opportunity for advocacy, as they obtain international attention and a direct contact with a bureaucratic UN system.Footnote 145

5. SUPPORTING COMPLIANCE WITH THE CBD

The section above analyzes the review mechanisms used in human rights and biodiversity domains, as well as the challenges reflected in both the CBD parties’ national reports and multi-stakeholder interviews. This section discusses: (i) the compliance strategies of review mechanisms; (ii) shared themes in national reports and interviews; and (iii) the insufficient mainstreaming of biodiversity.

5.1. Compliance Strategies of Review Mechanisms

Peer review processes involve a third-party evaluating implementation, which complements the states’ procedural obligations of national reporting. The UPR, Special Procedures, and VPR illustrate that review mechanisms for international law utilize various strategies for compliance, as identified in Table 3 above.

The CBD utilizes a management approach to compliance by emphasizing dialogue, capacity building, rule interpretation, and transparency. Although the CBD VPR marks progress by evaluating a country's performance with its substantive obligations, there is still room for improvement. The VPR neither has a formal follow-up mechanism for recommendations offered by the review team, nor enables independent civil society engagement.

The UPR demonstrates that states are willing to engage with cooperative approaches to compliance through state-to-state diplomatic relations. Fostering direct interaction between states enables democratic states to act independently from their regional counterparts.Footnote 146 The UPR establishes the norm of member states constructively critiquing each other's performance without provoking claims of disloyalty, which fosters a shift towards global collaborative governance.Footnote 147 Peer review mechanisms strike a balance between universalism and cultural relativism; national sovereignty is addressed with each member state deciding the national means to meet universal human rights standards, while facilitating diplomatic exchange on its substantive obligations.Footnote 148 These review mechanisms provide a forum to address a wide range of human rights, including gender issues.Footnote 149

Introducing independent evaluators with flexible mandates, as occurs in the Special Procedures, enables a shaping of legal norms. This suggests an interactional approach to lawmaking on issues that were left under-determined in the treaty negotiation process.Footnote 150 Review processes help with accountability as the roles and duties of actors are defined in the evaluation of the content of each national report.

Moreover, the zero draft text of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework specifically noted the need for developing an effective monitoring and review process.Footnote 151 The existing interest in an enhanced review mechanism creates an opportunity for strengthening implementation through peer learning.Footnote 152 Although some CBD parties may have been cautious in cross-referencing human rights instruments,Footnote 153 our findings on the compliance strategies used in international review mechanisms can offer learning for the CBD as its VPR process continues to develop.

5.2. Shared Themes in National Reports and Interviews

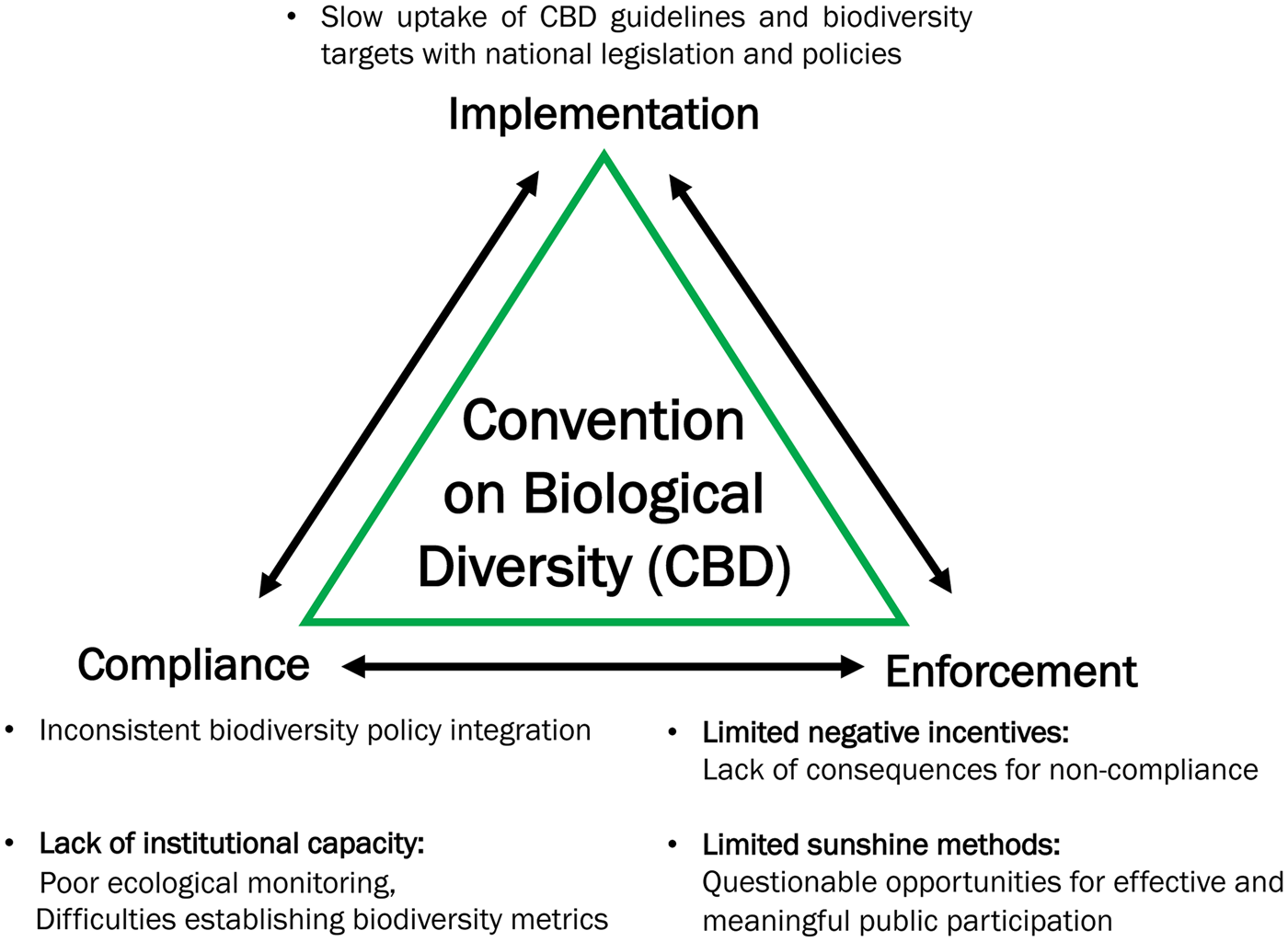

The national reports represent a country's self-assessment of their progress towards the Aichi Targets, while the interviews with a multi-stakeholder group provide a broader perspective of the challenges faced. As presented in Figure 1, these findings enable insights into the challenges of implementing, complying with, and enforcing the CBD.

Figure 1 Challenges Faced in Implementing, Complying with, and Enforcing the CBD

With regard to implementation, respondents highlighted a slow uptake of CBD guidelines and biodiversity targets into national legal and political systems. This may be exacerbated by a lack of institutional capacity, as indicated in the national reports. Meeting international environmental commitments requires significant state capacity, with various forms of incapacity existing in both the global north and south.Footnote 154

In terms of compliance, inconsistent biodiversity policy integration was noted in both the national reports and interviews. Biodiversity policies have yet to be integrated into sectors with a significant environmental impact. The national reports cited procedural reasons for this, including inadequate coordination among government agencies. For instance, the Ministry of Environment is often tasked with coordinating biodiversity policy integration across sectors, which competes with the sectoral ‘silos’ of other ministries such as the Ministry of Agriculture or Fisheries. Poor interagency coordination is compounded by an underlying business-as-usual approach to economic growth, as biodiversity conservation is often regarded as conflicting with other sector goals.Footnote 155 Responsibility for mainstreaming biodiversity does not diffuse sufficiently from the environmental administration to other policy sectors,Footnote 156 which was also alluded to in our interviews.Footnote 157

A lack of institutional capacity was also observed at national levels with poor ecological monitoring and difficulties in establishing biodiversity metrics that capture ecosystem complexity. The lack of capacity could partly be alleviated through positive incentives from the CBD, such as technical assistance. Although the CBD Secretariat coordinates a variety of training and capacity-building activities, strengthening institutional capacity requires ongoing effort over the long term. The VPR is one such example of capacity building, as its expert team provides recommendations to the state under review. As to the desirable but difficult challenge of determining universal biodiversity metrics, this is a recurring theme in the scientific literature.Footnote 158 A similar challenge was recognized by the Global Environment Facility, which in response recommended complementary qualitative and quantitative assessments.Footnote 159

Concerning enforcement, our findings confirm that various types of coercive measure are used in enforcing the CBD commitments. Firstly, there is a general lack of consequences for non-compliance and, hence, limited negative incentives. Although some respondents advocated stricter consequences of non-compliance,Footnote 160 this may be difficult to enforce in a forum such as the CBD, which has consensus-based decision making.Footnote 161 Even in treaties where sanctions are an option, this option is rarely activated as sanctions can be a blunt instrument.Footnote 162 Some respondents also noted the lack of negative incentives provided by governments to various sectors at the national level.Footnote 163

Secondly, few sunshine methods were found as respondents indicated that opportunities for public participation are limited. Sunshine methods allow flexibility and are more subtle than negative incentives in encouraging compliance. The benefits of the VPR and other peer review mechanisms are apparent here, as these mechanisms enable actors to exert public pressure on non-compliant actors. Interestingly, the lack of sunshine methods was not widely discussed in the national reports. One possible reason is that self-reporting processes may be prone to amplifying successes and minimizing shortcomings.Footnote 164 The multi-stakeholder interviews at CBD COP-14 also included CSOs and conservation groups, where each stakeholder has its own different set of priorities, which may contrast to those of national governments. A multi-stakeholder perspective therefore provides a more comprehensive picture of the challenges faced.

On a similar note, gender issues were stressed more often by the respondents than in the national reports, despite COP decisions on mainstreaming gender considerations.Footnote 165 Gender equality is a vital dimension in connecting human rights and biodiversity, and requires further research.Footnote 166 Although an overwhelming majority of CBD parties have already made commitments to gender equality under international law,Footnote 167 mainstreaming gender does not have the requisite emphasis in countries’ NBSAPs.Footnote 168 These findings shed light on how substantive obligations concerning gender equality need to be coupled with procedural mechanisms, such as an enabling environment for women and girls to participate in biodiversity governance.

5.3. Addressing Insufficient Mainstreaming of Biodiversity

Mainstreaming biodiversity was identified as a key implementation challenge from both the national reports and interviews. This issue is related to worldviews and value systems that favour economic growth over sustainable development.Footnote 169 Ultimately, an underlying tension exists between the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity with a long-term perspective and the use of natural resources for economic benefits in the short term. Sustainable use is hard to achieve. NBSAPs often do not specify concrete policy and legal measures needed for achieving mainstreaming goals and targets.Footnote 170 Policy inconsistencies tend to occur in national policies, such as a clash between nature conservation, healthy ecosystems, and mineral extraction.Footnote 171

To strengthen the role of the CBD in supporting a good quality of life, lessons can be derived from human rights mechanisms. In particular, the CBD can gain insight on how review mechanisms clarify obligations and support the implementation of substantive human rights obligations, such as the right to life, the right to health, and rights to clean water and sanitation. For instance, a report by the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and environment clarified substantive obligations and provided recommendations on mainstreaming biodiversity in various policy areas, informed by interpretations of state obligations under human rights law and Articles 5–14 CBD.Footnote 172 These obligations are indivisible from procedural obligations, such as delivering an inclusive, equitable, and gender-based approach to public participation in the process of mainstreaming biodiversity.Footnote 173 Implementing procedural obligations in mainstreaming biodiversity is needed in specific sectors, such as mining, as well as cross-sectorally, such as in national development plans.Footnote 174

6. CONCLUSION

Humanity is at a crossroads in addressing biodiversity loss and the degradation of ecosystems, which is affecting people and nature in unprecedented ways. While several assessments have reported on the CBD parties’ weak compliance with the Aichi Targets, our findings reveal significant differences in terms of the levels of compliance across CBD procedural and substantive obligations. There is a higher level of compliance with procedural obligations compared with substantive obligations. Through analyzing national reports and multi-stakeholder interviews, we identified key challenges in implementing the CBD. Challenges include the lack of institutional capacity; slow uptake of CBD guidelines into national policies; difficulties in ecological monitoring and establishing universal biodiversity metrics; inconsistent biodiversity policy integration; and questionable opportunities for effective and meaningful public participation. These challenges hamper state compliance with CBD obligations.

Understanding the reasons behind the CBD compliance gap is important for then identifying ways in which CBD mechanisms can be improved. Lessons learnt from human rights review mechanisms are used in this article to uncover means to better implement and enforce the CBD commitments. Human rights review mechanisms use both monitoring compliance with international obligations and a problem-solving approach to capacity building and transparency. We find that framing the managerial and enforcement compliance approaches as complementary, rather than mutually exclusive, helps to strengthen the CBD VPR and envisions innovative ways to foster compliance and accountability. Insights from human rights review mechanisms can strengthen the CBD's procedural means for implementing its substantive objectives.

The post-2020 global biodiversity framework provides a window of opportunity to prioritize an enhanced review mechanism to strengthen the implementation of CBD obligations. There is an urgent need to take the compliance gap seriously and initiate the transformative changes required to achieve the 2050 CBD vision of living in harmony with nature.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102521000169