Over the last decades, there has been a dramatic shift in the dietary patterns in children and adolescents globally toward the consumption of discretionary foods (i.e., energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods rich in added sugars, added salt, saturated fat and alcohol), while a low intake of nutrient-dense foods, particularly whole grains, fruits and vegetables(Reference Beal, Morris and Tumilowicz1–Reference Voráčová, Sigmund and Sigmundová4). This is particularly important since the statistics indicate that unhealthy dietary patterns are responsible for over 11 million deaths globally. Nearly half of the deaths are attributed to the three dietary factors, including high Na intake and low intake of whole grains and fruits(Reference Collaborators5). Notably, dietary patterns established in childhood could persist during the later ages and even influence the risk of diet-related diseases in adulthood, particularly CVD(Reference Kaikkonen, Mikkilä and Raitakari6–Reference Ziesmann, Kiflen and Rubeis8). In addition, the nutritional programming theory indicates that the intake of specific nutrients in certain quantities during the first years of life may have a long-term influence on health mainly through epigenetic mechanisms(Reference Agostoni, Baselli and Mazzoni9). Therefore, identifying the factors that affect food preferences, particularly at an early age, is a key step in promoting healthy dietary patterns as a global public health priority.

Recently, there has been a growing interest in the contribution of early-life exposures, particularly breast-feeding, in determining long-term food preferences. Exclusive breast-feeding is the preferred method of infant feeding from birth up to 6 months, accompanied by solid foods until 2 years of age. Such a feeding pattern has been shown to provide optimal growth and reduce the risk of infections in the first years of life(10). Besides, accumulating evidence from epidemiological studies has shown that breast-feeding is associated with a higher intake of nutrient-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables while a lower intake of discretionary foods during childhood(Reference Barends, Weenen and Warren11–Reference Ventura13).

It is hypothesised that breast-feeding may influence the acceptability of certain foods mainly by introducing various flavours to infants(Reference Spahn, Callahan and Spill14). The repeated exposure to these flavours, which are transferred through the maternal diet, could modify the infant’s innate inclination to sweet and savoury tastes, while a disinclination to sour and bitter tastes at birth(Reference Ventura13,Reference Cooke and Fildes15) . Interestingly, these flavours have been shown to share some similarities in terms of molecular structure and sensory properties with flavours found in fruits and vegetables(Reference Ventura13). Hence, continued breast-feeding might familiarise infants with the flavours of healthy foods with less palatable tastes and facilitate their acceptance during the weaning period. In addition to the flavour experiences, another possible mechanism of breast-feeding in modifying food preferences might be attributed to the hormones in breast milk, particularly leptin. Leptin, an anorexigenic hormone, can pass from breast milk and be uptaken by the infant’s circulatory system(Reference Savino, Liguori and Fissore16). Evidence from animal models has demonstrated that administration of leptin orally in breast-fed infants was accompanied by lower energy intake as well as a reduced preference for high-fat foods compared with the control during the weaning period(Reference Palou and Picó17,Reference Sánchez, Priego and Palou18) . Thus, it raises the hypothesis that exposure to breast milk may lead to the low consumption of high-fat, energy-dense foods at later ages.

To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of comprehensive review regarding the relationship between breast-feeding with dietary patterns during early childhood and later ages. With this regard, the present study aimed to systematically review the association between exposure to breast-feeding as well as its duration with data-driven and hypothesis-driven (diet quality scores) dietary patterns in individuals aged 1-year-old and older.

Materials and methods

The present systematic review was performed in accordance with the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement(Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff19). The protocol of this report was registered at PROSPERO (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021265491). The study selection, data extraction and quality assessment were conducted by both authors, and any disagreement was settled by consensus.

Search strategy

The databases of PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science were searched for the English language documents published from January 2010 until July 2021 using the following keywords: (‘Breast Feeding’ OR ‘breastfed’) AND (‘diet*’ AND ‘pattern*’) OR (‘diet* AND quality’) OR (‘diet*’ AND ‘index*’) OR (‘diet*’ AND ‘indices’) OR (‘diet*’ AND ‘score*’) OR (‘eating’ AND ‘pattern*’) OR (‘food’ AND ‘pattern*’). In addition, the bibliographies of the relevant articles were hand-searched to ensure all eligible studies have been included.

Study selection

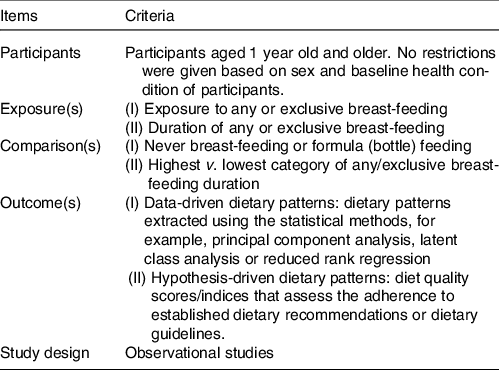

Following the removal of the duplicates, the title and abstract of the reaming records were screened to withdraw those with irrelevant topics, conference/meeting abstracts and narrative reviews. Thereafter, the full text of the remaining articles underwent a rigorous evaluation to select those that had met the Participants, Exposure, Comparison, Outcomes and Study design (PECOS) criteria for inclusion in the review (Table 1). Studies with the following outcomes were outside the scope of this review and thus were excluded: nutrient intakes; food items/groups; eating habits, for example, breakfast consumption and meal skipping, etc.; feeding difficulties such as food neophobia and picky/fussy eating; eating disorders and combination of diet quality with non-dietary components such as physical activity.

Table 1. PECOS criteria for identification of eligible articles

Data extraction

Following data were extracted from the eligible studies: First author’s surname, publication year, study location (country), population’s age and sex, sample size, study design, type of exposure, the method of dietary data collection, the identified dietary patterns or the diet scores used, covariates and study outcomes. For all studies, we extracted the estimates in the fully adjusted model for confounding factors.

Quality assessment

We have adapted the criteria introduced by the Joanna Briggs Institute for qualitative assessment of bias in the methodology of included studies(20). For the purpose of this review, we assessed the following four domains: (1) definition of inclusion criteria in the study sample; (2) validity and reliability of exposure assessment; (3) validity and reliability of outcome measurement and (4) identification of confounding factors. We did not apply scoring criteria for quality assessment since it might not accurately reflect the overall study quality. Instead, we presented a qualitative evaluation of each domain in line with the Joanna Briggs Institute recommendations.

Results

Study selection

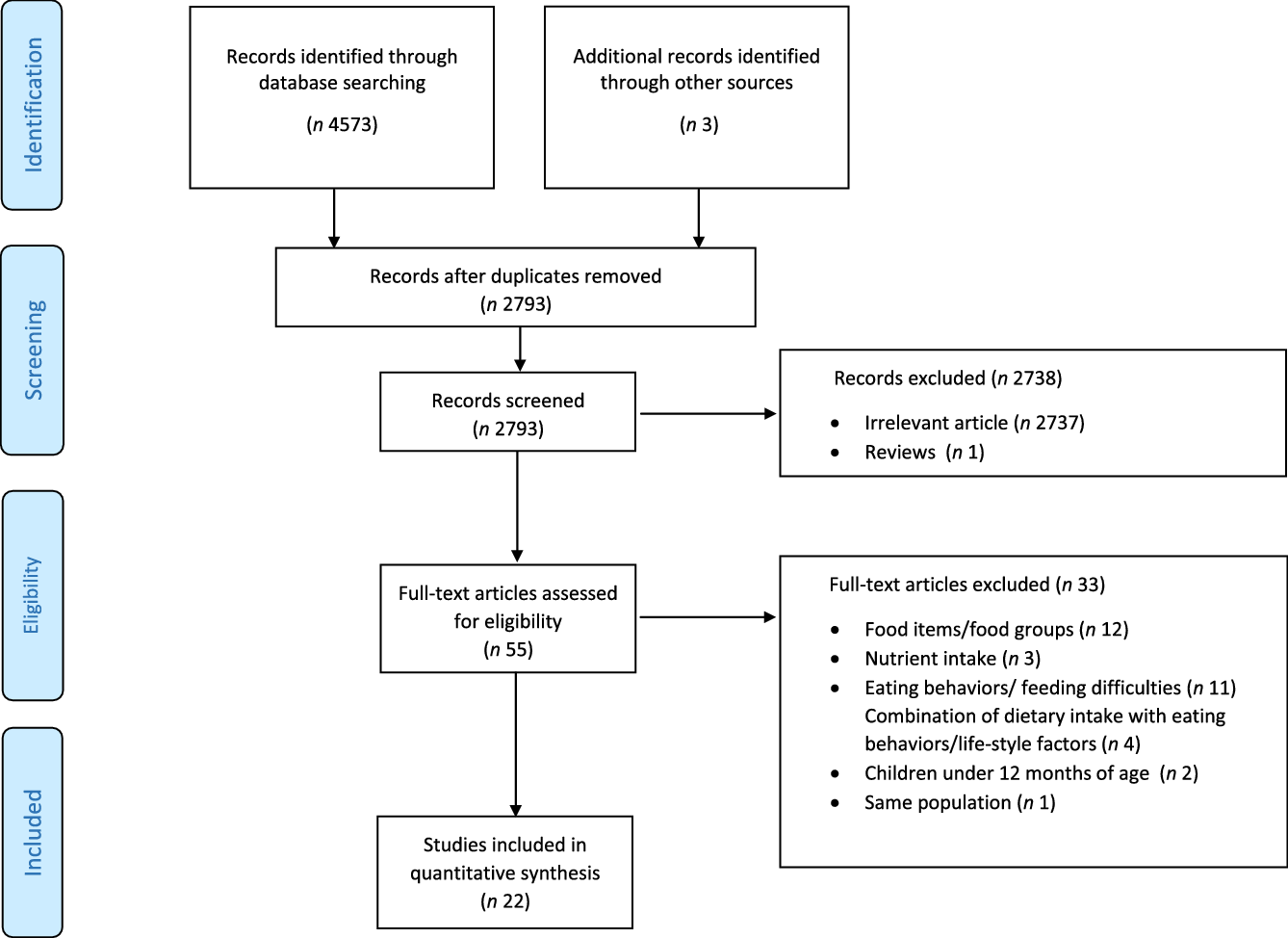

Figure 1 provides details on literature search and study selection according to the PRISMA guideline. The search strategy yielded the extraction of 4573 records. After removing the duplicates (n 1783), screening the title and abstract of the retrieved records (n 2790) excluded 2737 not-relevant documents and one narrative review article. In addition, three articles were added through hand searching of the literature. Then, the full texts of the fifty-five remaining articles were meticulously reviewed, which led to the exclusion of further thirty-three articles due to the following reasons: (1) the outcome was the intake of food items or food groups (n 12); (2) the outcome was feeding difficulties or eating behaviours (n 11); (3) the outcome was nutrient intake (n 3); (3) diet quality index was a combination of dietary intakes and eating behaviours or lifestyle-related practices (n 4); (4) the study sample’s age was under 12 months old (n 2) and (6) the study was conducted in the same population (n 1). Finally, twenty-two eligible articles were included in the review.

Fig. 1. The PRISMA flow diagram for literature search and selection.

Study characteristics

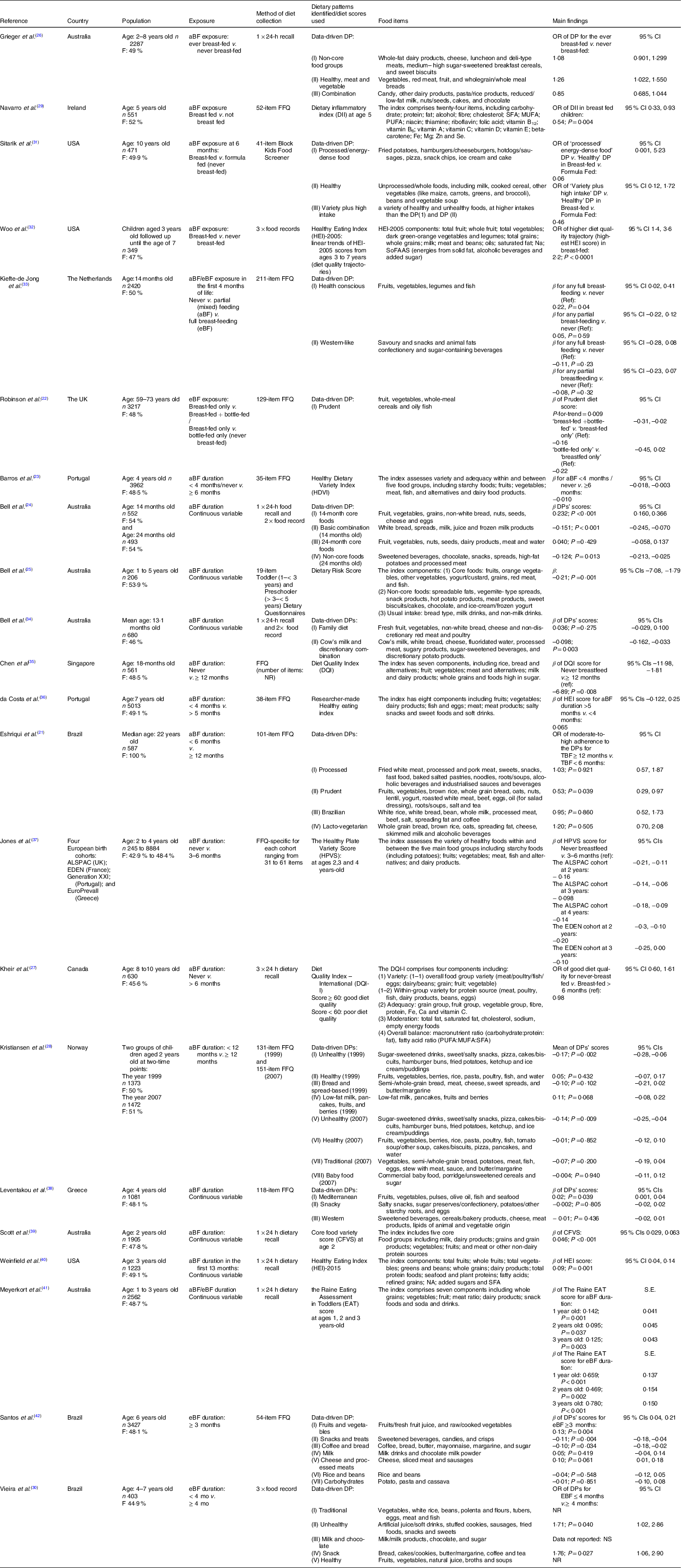

Table 2 summarises the characteristics and main outcomes of the eligible studies. The majority of studies were conducted in European countries (n 8), and the rest in Australia (n 6), USA (n 3), Brazil (n 3), Canada (n 1) and Singapore (n 1). Two(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22) out of twenty-two studies were conducted in adults (i.e., age ≥ 18 years old), while others were conducted in children at ages ranging from 12 months up to 10 years old. Except for the study by Eshriqui et al. (Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21), which was comprised of only women, the rest included both sexes, with females comprising 42·9 % to 54 % of the participants across the studies. The sample size ranged between 206 and 8884. Nine studies had a cross-sectional design(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Barros, Lopes and Oliveira23–Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30) . While one study was a historical cohort(Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22), and the rest had a longitudinal design.

Table 2. Summary of characteristics and main findings of studies investigating the association between breast-feeding exposure and duration with offspring’s dietary patterns over 1 year of age

F, female; aBF, any breast-feeding; DP, Dietary pattern; eBF, exclusive breast-feeding; NR, not reported; NS, not significant.

In terms of the exposure of interest, exposure to any breast-feeding was assessed in five studies(Reference Grieger, Scott and Cobiac26,Reference Navarro, Shivappa and Hébert29,Reference Sitarik, Kerver and Havstad31–Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33) . While two studies collected the data on exposure to exclusive breast-feeding(Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22,Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33) . Similarly, fourteen studies had assessed the duration of any breast-feeding in months(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Barros, Lopes and Oliveira23–Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan25,Reference Kheir, Feeley and Maximova27,Reference Kristiansen, Lande and Sexton28,Reference Bell, Schammer and Devenish34–Reference Meyerkort, Oddy and O’Sullivan41) . While the duration of exclusive breast-feeding (in months) was assessed in only three studies(Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30,Reference Meyerkort, Oddy and O’Sullivan41,Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42) . With regard to the method of dietary data collection, about half of the studies had used a FFQ that was validated in their target population. The outcome of interest was diet quality scores in eleven studies(Reference Barros, Lopes and Oliveira23,Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan25,Reference Kheir, Feeley and Maximova27,Reference Navarro, Shivappa and Hébert29,Reference Woo, Reynolds and Summer32,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok35–Reference Jones, Moschonis and Oliveira37,Reference Scott, Chih and Oddy39–Reference Meyerkort, Oddy and O’Sullivan41) , although the rest had assessed data-driven dietary patterns. The diet quality indices varied in terms of their food components and scoring criteria. In all diet quality indices used, a higher score indicated a better diet quality, except for the Dietary Risk Score(Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan25) and Dietary Inflammatory Index(Reference Navarro, Shivappa and Hébert29), in which a higher score reflected a poorer diet quality. Regarding the data-driven dietary patterns, a total of forty-two dietary patterns were identified in the included studies. All studies had extracted dietary patterns using principal component analysis, except for the study by Sitarik et al. (Reference Sitarik, Kerver and Havstad31), which used the latent class analysis.

The quality assessment of included studies revealed that only seven out of twenty-two studies had clarified the inclusion criteria in their study sample(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Barros, Lopes and Oliveira23,Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan25,Reference Kheir, Feeley and Maximova27,Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30,Reference Woo, Reynolds and Summer32,Reference da Costa, Durão and Lopes36) . In addition, the exposure (i.e., breast-feeding) was assessed in all studies self-reported through interviews, questionnaires, and medical records, and none had provided details on the validity and reliability of their collection method. Moreover, nine studies(Reference Bell, Golley and Daniels24,Reference Grieger, Scott and Cobiac26,Reference Kheir, Feeley and Maximova27,Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30,Reference Woo, Reynolds and Summer32,Reference Bell, Schammer and Devenish34,Reference Scott, Chih and Oddy39–Reference Meyerkort, Oddy and O’Sullivan41) did not clarify whether the outcome assessment was validated in their study population. In terms of the confounding factors, all studies had adjusted the association for a variety of maternal and child characteristics (online Supplementary Materials: Table S1). However, only seven studies(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Sitarik, Kerver and Havstad31,Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33,Reference Chen, Fung and Fok35,Reference Jones, Moschonis and Oliveira37–Reference Scott, Chih and Oddy39) had clearly indicated the rationale for the selection of potential confounders in their study sample.

Main findings

The considerable heterogeneity across the studies in terms of the population’s characteristics, assessment of exposure and outcome and the statistical methods used did not allow us to perform a meta-analysis. Therefore, we relied on the qualitative data synthesis stratified by the type of exposure (i.e., breast-feeding exposure/duration) and outcome (data-driven dietary patterns and diet quality scores).

Exposure to any/exclusive breast-feeding and data-driven dietary patterns

Two studies(Reference Grieger, Scott and Cobiac26,Reference Sitarik, Kerver and Havstad31) assessed the relationship between exposure to any breast-feeding with a total of five dietary patterns. Of the identified dietary patterns, two were loaded with healthy foods labelled as ‘Healthy, meat and vegetable’ and ’Healthy’, while one labelled as ’Processed/energy-dense food’ comprising discretionary foods. The three remaining dietary patterns included healthy and unhealthy foods, labelled as ’Non-core food groups’, ‘Combination’ and ’Variety plus high intake’. The qualitative analysis demonstrated that compared with never breast-feeding (or formula/bottle feeding), exposure to any breast-feeding was positively associated with ’Healthy, meat and vegetable’ pattern score at ages 2–8 years old(Reference Grieger, Scott and Cobiac26). However, the association with other identified dietary patterns did not reach a statistically significant level.

Regarding the exposure to exclusive breast-feeding, two studies(Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22,Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33) with three major dietary patterns, two loaded with healthy foods (’Health conscious’ and ’Prudent’ patterns) and the latter comprised of discretionary foods (’Western-like’) were included. The findings showed a positive association between exposure to exclusive breast-feeding with ‘Health conscious’ pattern score at 14 months old(Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33) and ‘Prudent’ pattern score at ages 59–73 years old(Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22). In contrast, no significant association was found for ‘Western-like’ pattern(Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33).

Exposure to any/exclusive breast-feeding and diet quality scores

Two studies(Reference Navarro, Shivappa and Hébert29,Reference Woo, Reynolds and Summer32) evaluated the association between exposure to any breast-feeding with two different diet quality scores, namely Dietary Inflammatory Index and Healthy Eating Index-2005. However, no study was found for exclusive breast-feeding exposure. The results indicated that exposure to any breast-feeding was significantly associated with a lower Dietary Inflammatory Index (i.e., a more anti-inflammatory diet) at age 5(Reference Navarro, Shivappa and Hébert29) and a higher Healthy Eating Index-2005 score between 3 and 7 years of age(Reference Woo, Reynolds and Summer32).

Duration of any/exclusive breast-feeding and data-driven dietary patterns

Five studies assessed the association of the duration of any breast-feeding with twenty-one extracted dietary patterns(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Bell, Golley and Daniels24,Reference Kristiansen, Lande and Sexton28,Reference Bell, Schammer and Devenish34,Reference Leventakou, Sarri and Georgiou38) . Of the twenty-one dietary patterns, six were loaded with healthy foods labelled as ‘14-month core foods’, ‘24-month core foods’, ‘Family diet’, ‘Prudent’, ‘Healthy, 1999’ and ‘Mediterranean’. While six other dietary patterns were comprised of only discretionary foods labeled as ‘Non-core foods’, ‘Cow’s milk and discretionary combination’, ‘Processed’, ‘Unhealthy, 1999’, ‘Unhealthy, 2007’ and ‘Western’. The nine remaining dietary patterns were loaded with a mixture of both healthy and unhealthy foods and labeled as ‘Basic combination’, ‘Brazilian’, ‘Lacto-vegetarian’, ‘Bread and spread-based,1999’, ‘Low-fat milk, pancakes, fruits, and berries’, ‘Traditional,2007’, ‘Healthy, 2007’, ‘Baby food’ and ‘Snacky’. The findings indicated that a longer duration of any breast-feeding was significantly associated with higher scores on ‘14-month core foods’(Reference Bell, Golley and Daniels24), ‘Prudent’(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21) and ‘Mediterranean’(Reference Leventakou, Sarri and Georgiou38) patterns. While it was inversely related to ‘Non-core foods’(Reference Bell, Golley and Daniels24), ‘Cow’s milk and discretionary combination’(Reference Bell, Schammer and Devenish34), ‘Unhealthy (1999 & 2007)’(Reference Kristiansen, Lande and Sexton28) and ‘Basic combination’(Reference Bell, Golley and Daniels24) patterns.

The association between exclusive breast-feeding duration with dietary patterns was evaluated in two studies(Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30,Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42) , with eleven identified dietary patterns combined. Of these, six were comprised of healthy foods (‘Fruits and vegetables’, ‘Milk’, ‘Rice and beans’, ‘Carbohydrates’, ‘Traditional’ and ‘Healthy’), while two were loaded with discretionary foods, namely ‘Snacks and treats’ and ‘Unhealthy’ patterns. The three remaining dietary patterns labelled as ‘Coffee and bread’, ‘Cheese and processed meats’, ‘Milk and chocolate’ and ‘Snack’ were a combination of both healthy and discretionary foods. The qualitative analysis demonstrated that a longer duration of exclusive breast-feeding was significantly associated with higher scores on ‘Fruits and vegetables’ pattern(Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42). In comparison, it was negatively associated with ‘Snacks and treats’ (Reference Kristiansen, Lande and Sexton28), ‘Unhealthy’ (Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42), ‘Coffee and bread’ (Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42) and ‘Snack’ (Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30) patterns scores.

Duration of any/exclusive breast-feeding and diet quality scores

Nine studies investigated the association between the duration of any breast-feeding and diet quality scores. Of these, three studies reported that the duration of any breast-feeding was positively associated with diet variety between the ages 2–4 years old, as shown by higher scores on ‘Healthy Dietary Variety Index’ (Reference Barros, Lopes and Oliveira23) , ‘The Healthy Plate Variety Score’ (Reference Jones, Moschonis and Oliveira37) and ‘Core food variety score’ (Reference Scott, Chih and Oddy39). Similarly, the results of four studies in children aged 1–5 years old indicated that a longer duration of any breast-feeding was significantly associated with higher scores on ‘Diet Quality Index’(Reference Chen, Fung and Fok35), ‘the Raine Eating Assessment in Toddlers’(Reference Meyerkort, Oddy and O’Sullivan41) and ‘HEI–2015’(Reference Weinfield, Borger and Gola40), while it was inversely associated with the ‘Dietary Risk Score’(Reference Bell, Jansen and Mallan25). However, two studies that used the ‘Diet Quality Index – International’ and a researcher-made ‘Healthy Eating Index’ among children at ages 7–10 years old did not report such a significant association(Reference Kheir, Feeley and Maximova27,Reference da Costa, Durão and Lopes36) . Unlike any breast-feeding, none of the included studies had investigated the association between the duration of exclusive breast-feeding and diet quality scores.

Discussion

The present study summarised the results of observational studies investigating the association between exposure to breast milk and its duration with dietary patterns over 1 year of age. We observed a remarkable heterogeneity across studies in terms of exposure and outcome reporting. Of the twenty-two eligible studies, nineteen reported a significant association between breast-feeding exposure and duration with at least one dietary pattern or diet quality score. Overall, being exposed to breast milk as well as a longer duration of any/exclusive breast-feeding were associated with healthy dietary patterns and better diet quality in both children and adults.

The relationship between breast-feeding and diet has already been investigated at the level of food items and food groups. Some studies reported that a longer duration of any or exclusive breast-feeding was associated with a higher intake of fruits(Reference Beckerman, Slade and Ventura43–Reference Perrine, Galuska and Thompson46) and vegetables(Reference Beckerman, Slade and Ventura43–Reference Soldateli, Vigo and Giugliani51) in children, while a lower consumption of processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages(Reference Fonseca, Ribeiro and Andreoli45,Reference Perrine, Galuska and Thompson46,Reference Bielemann, Santos and Costa52,Reference Jackson and Johnson53) . However, in nutritional epidemiology, the reductionist approach, which only considers a particular food or food group, might not provide a comprehensive picture of dietary intake since people do not consume foods in isolation. In contrast, data-driven and hypothesis-driven dietary patterns assess food items in combination and capture a snapshot of the whole diet more accurately(Reference Cespedes and Hu54,Reference Tapsell and Neale55) . The hypothesis-driven dietary patterns are based on the existing knowledge of healthy diets, and they measure the degree of adherence to the recommended healthy diets and dietary guidelines. Although in data-driven dietary patterns, statistical techniques are employed to extract dietary patterns, and contrary to the diet quality scores, they might not completely comply with the dietary recommendations since they depend on the study’s population(Reference Jacques and Tucker56). Moreover, the diet quality scores used across studies varied considerably in terms of their scoring components as they were based on the dietary intake of only nutrients (e.g., Dietary Inflammatory Index), nutrient plus foods/food groups (e.g., Healthy Eating Index and Diet Quality Index-I) or only foods/food groups. Taken together, the aforementioned factors should be taken into account when interpreting the relationship between breast-feeding and data-driven dietary patterns and diet quality scores.

Formula feeding, another early feeding practice, is also suggested that could affect food acceptance through flavour experiences(Reference Haller, Rummel and Henneberg57–Reference Mennella and Beauchamp59); for example, a survey among 133 adults who were breast-fed or bottle-fed with vanilla-flavoured formula showed that a majority of formula-fed subjects had a preference to the vanilla-flavoured ketchup, while the breast-fed ones showed a greater tendency to the plain ketchup(Reference Haller, Rummel and Henneberg57). Moreover, the taste preferences and food choices are varied based on the type of formula consumed since it is demonstrated that children who had received a protein hydrolysate formula showed a higher tendency to the sour-flavoured juices as well as a higher preference to broccoli compared with those who were fed milk-based formulas(Reference Mennella and Beauchamp59). Thus, in addition to breast-feeding, formula feeding might also contribute to the taste experiences and subsequently eating patterns in the later ages. However, in this review, except for four studies(Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22,Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30,Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33,Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42) that had just evaluated exclusive breast-feeding, the rest have focused on any breast-feeding, which might include both breast-feeding and formula-feeding. Hence, the hypothesis that whether formula feeding has provided a synergistic effect, in conjunction with breast-feeding, toward healthy food choices could not be ruled out. However, they did not consider the duration of formula feeding in the study sample, which made it difficult to elucidate concrete evidence on this topic.

Besides the feeding practices in the first years of life, maternal influences might also determine the dietary patterns at later ages. Accumulating evidence from experimental studies indicates that maternal intake of foods rich in fat, sugar and Na during pregnancy and lactation is accompanied by a higher preference for these foods in their offspring(Reference Bayol, Farrington and Stickland60,Reference Santos, Cordeiro and Perez61) . Similarly, several observational studies have shown a positive association between maternal and child dietary intakes and diet quality(Reference Bjerregaard, Halldorsson and Tetens62–Reference Wang, Beydoun and Li64). Furthermore, mothers might affect their child’s food preferences mainly by controlling the portion sizes and the amount of foods that their child consumes, pressure or encouragement to eat, and indirectly, by providing (purchasing) only healthy foods at home and eliminating them the takeaway and junk foods. Even it is shown that parents who are worried about the risk of becoming obese in children, those parents who are overweight/obese, or those with overeating, might influence their children’s dietary patterns by taking several restrictive measures(Reference Savage, Fisher and Birch65,Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino66) . In our review, only two out of twenty-two studies assessed the maternal diet during pregnancy at the level of macronutrients (i.e., dietary carbohydrate, fibre and fat intake) and diet quality (i.e., diet variety score) in the study sample(Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33,Reference Jones, Moschonis and Oliveira37) . However, the remaining studies did not consider the potential contribution of maternal dietary intakes during pregnancy/lactation as well as parental modelling when interpreting the relationship between breast-feeding and dietary patterns. Therefore, further studies are warranted to explore the mediating role of parents’ lifestyle components on the association between feeding experiences in the first year of life and later dietary patterns.

The studies included in this review had some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, both exposure and outcome were collected using the self-reporting method. Furthermore, except for two studies(Reference Eshriqui, Folchetti and Valente21,Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22) that were conducted in adults, the rest were comprised of children within the age range of 1–10 years old, and their dietary intakes were collected through interviews with their parents/caregivers. Thus, the possibility of recall and reporting biases could not be ruled out. Second, 40% of studies had a cross-sectional design, which cannot determine the causality of the relationship. Third, most studies did not provide a clear definition of inclusion criteria of the study sample, for example, whether their sample had followed any special diets such as gluten-free diets and low-energy diets, which might affect the study outcome. Fourth, most studies had not clarified whether they had considered under/over-reporting the total energy intake that could potentially affect the accuracy of reported dietary intakes(Reference Livingstone and Black67). Fifth, the majority of studies did not clarify how they identified potential confounding factors in their study population, which raised the possibility that the results might be affected by over- or under-adjustment.

Besides, several limitations of the present review should be acknowledged. Most of the evidence on breast-feeding and later dietary patterns were related to any breast-feeding, while only four studies(Reference Robinson, Ntani and Simmonds22,Reference Vieira, de Almeida Fonseca and Andreoli30,Reference Kiefte-de Jong, de Vries and Bleeker33,Reference Santos, Assunção and Matijasevich42) had evaluated exclusive breast-feeding. In addition, the evidence came from the population living in developed or high-income countries. Whether the findings of this review are also generalisable to the population from developing or low-income countries remains to be answered. Furthermore, due to the methodological variations, the present report relied on the qualitative synthesis of outcomes instead of a quantitative synthesis (i.e., meta-analysis).

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that exposure to breast milk and a longer duration of breast-feeding is associated with greater adherence to the healthy dietary patterns characterised mainly by high consumption of nutrient-dense foods, particularly fruits, vegetables and whole grains. While they are inversely associated with unhealthy dietary patterns loaded with discretionary foods. Nevertheless, in light of the above-mentioned limitations, further research is warranted to elucidate more rigorous evidence on this topic.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

O. E: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing - original draft; F. S.: Conceptualisation, methodology, writing - review and editing, supervision.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114522002057