Introduction

Space is too important to be left to the geographers. The spatial dimensions of transborder migration, regional (dis)integration, the shift towards a multipolar world, capital mobility, pathogenic networks of contagion, or the US ‘pivot to Asia’, to name but a few examples, are too important to be ignored. Space is more than just the location of politics and such ‘container’ notions of space, still all too prevalent in many writings, prevent us from grasping its dynamic nature. This article does not argue, as recent popular titles assert, that we are ‘prisoners of geography’,Footnote 1 but as Barney Warf and Santa Arias succinctly put it, ‘(g)eography matters, not for the simplistic and overly used reason that everything happens in space, but because where things happen is critical to knowing how and why they happen’.Footnote 2

The inability of International Relations (IR) to grapple with geographical concepts is a recurring critique of the discipline.Footnote 3 Certainly, mainstream IR theory has focused too much on territory at the expense of other sociospatial ontologies. Mobilities and flows are hard to reconcile even with dynamic understandings of territory, networks follow an entirely different logic, and a territorial perspective that privileges the state as the centrepiece around which other levels of analysis are constructed overlooks or sidelines other forms of scalarity. This critique has been most forcefully articulated by John Agnew, who in 1994 accused IR of being caught in a ‘territorial trap’ wherein it reifies the sovereign territorial container as the natural unit of politics, thereby dehistoricising processes of state formation and obscuring interactions across scales.Footnote 4 This critique has been revisited and echoed over the years, most recently by Orit Gazit who asked ‘why IR theory has historically tended to take the sociospatial dimension of world politics for granted’.Footnote 5

Hence, the challenge for IR is to move towards a critical conceptualisation of space that looks beyond territory. Agnew's critique clearly still has merit. For example, it is hard to find a substantive discussion of space in introductory IR textbooks beyond bland references to globalisation.Footnote 6 Influential stocktaking exercises like the European Journal of International Relations’ Special Issue on the ‘End of IR Theory’ barely mention spatial aspects, except in purely metaphorical terms.Footnote 7 For instance, Patrick T. Jackson and Dan H. Nexon omit any reference to space, place, or scale in their ‘catalog – or map [!] – of the basic substances and processes that constitute world politics’.Footnote 8

However, this should not lead us to underestimate the breadth of work in IR that explores other forms of political spatiality, such as places, scales, bodies, networks, etc. Since the 1990s, in particular, many communities have developed research programmes in these directions, from the geopolitics of security studies (both classical and critical) via core-periphery models and feminist writings to explorations of ‘the global’ in International Political Sociology and ‘the local’ in peace research. In short: There is a lot of work within IR that theorises space. Most recently, Beth A. Simmons and Hein E. Goemans have proposed a research agenda on political space within the liberal international order.Footnote 9 But what has been lacking is a conceptual framework that allows for different ways of theorising space and power. To enable conversations across fields and disciplinary boundaries, this article proposes such a framework centred around the concept of space as a way of relating different spatialities to each other.Footnote 10 There is also a nascent theoretical conversation emerging within IR on ways of conceptualising space that this article wishes to move forward.Footnote 11 To this end, I draw on discussions from Political Geography to develop a conceptual framework that treats space not as a static container but as the momentary outcome of processes of social construction. In contrast to many previous treatments, the framework approaches the construction of space not just through discourses and symbols but also includes material factors since spatial constructions are never independent from physical geography, technology, and non-human agents.Footnote 12 Bringing these elements together, this article proposes a heuristic of ‘spatial practices’ that detail how spaces are enacted.

This spatial approach offers several benefits for IR research. For one, it allows us to relate existing works from different research fields to each other, for example, whether the spatial contagion of civil wars changes understandings of ‘region-ness’ and dynamics of regional integration.Footnote 13 For another, it becomes possible to relate objects, processes, and actors across scales and problematise the construction of scales themselves, making it possible to connect the micro-level to larger social figurations, seeing the local in the global and the global in the local.Footnote 14 Finally, a spatial perspective makes us attentive to the two-way relationship between space and governance. On the one hand, every act of governance has a spatial claim embedded in it, thereby (re)creating those spaces.Footnote 15 On the other hand, spatial arrangements shape forms of governance, with the division of the world into territorial states being the most glaring example.Footnote 16

This article begins with a critical review of the disparate approaches to space that can be broadly situated within and around IR. It then lays out four crucial aspects of a spatial approach to global politics: a spatial ontology, the constructedness of space, a scalar perspective, and how to bring together materiality and ideas in the construction of space. After that, the article elaborates a framework of spatial practices that can be specified to fit different sociospatial ontologies. These discussions are then illustrated with a brief review of Arctic Security Research as an exemplary research field that has developed around a spatial approach.

The space(s) of IR

Territory

There is a popular critique that the IR mainstream, inasmuch such a thing can be said to exist, has focused on territoriality, ‘associated it entirely with states … and completely missed the other ways in which world politics has been organized geographically’.Footnote 17 However, the focus on territory as the singular spatial frame through which to view global politics did not translate into sustained engagement with the concept itself, leading John G. Ruggie to exclaim: ‘It is truly astonishing that the concept of territoriality has been so little studied by students of international politics; its neglect is akin to never looking at the ground that one is walking on.’Footnote 18 This has been changing slowly – as Boaz Atzili and Burak Kadercan assert, ‘(t)erritory is back with a vengeance.’Footnote 19

Recent works by Kadercan and Jordan Branch have moved the theoretical conversation on territory in IR forward.Footnote 20 Kadercan distinguishes three dimensions of territory: space (environmental and material features), demarcation (boundaries), and constitution (ideas, power relations). This is a useful framework that brings together material conditions, ideational factors, and social action. But Branch correctly points out that Kadercan misses an opportunity by conceptualising demarcation as a process, not as a practice that would highlight how territory is continually reproduced after the official act of demarcation is finished.Footnote 21 Branch's definition of territory rests on three dimensions: ideas that identify territory as a jurisdictional space of the state; bordering practices that allocate, delimit, and demarcate space; and technologies that map and visualise territories. Beyond the focus on practices, the inclusion of bordering technologies is helpful.Footnote 22 But while Branch adds a useful aspect to the discussion about territory, he leaves out another, equally important one that Kadercan highlighted, namely the environmental and material features of territory. But the fundamental limitation of both Kadercan's and Branch's work and most other IR approaches is that territory is only one lens through which we can theorise sociospatial relations, which is why we need a theory of space more generally.

The territorial focus of IR is a result of its intellectual history. R. B. J. Walker has discussed at length how the ‘division of labour between political theory and theories of international relations’ led to an understanding of the state that is both spatially reductionist and historically static.Footnote 23 This view of state as the limit and the arbiter between inside and outside implied a ‘container’ view of the state and limited our understanding of scalarity to the Waltzian ‘levels of analysis’.Footnote 24 The duality of ‘the national’ and ‘the international’ is the cornerstone of the territorial trapFootnote 25 – a trap that IR theory and its ‘frozen geography’Footnote 26 still has to escape. But sovereignty and territory need not be intrinsically linked. One way is to conceptually ‘unbundle’ sovereignty by separating political authority from exclusive territoriality and instead explore the complexity of spatial arrangements of power. An example of this is Yale H. Ferguson and Richard Mansbach's ‘polities’ model of global politics, which insists that it is not just states who exercise power over space and that such fields of power may not be exclusive.Footnote 27 Another, more radical approach problematises the assumption that sovereignty and territoriality were ever married as closely as it generally claimed. Agnew, in particular, has argued that the territorial expression of sovereignty is historically contingent and geographically uneven, with multiple ‘sovereignty regimes’ operating in different contexts.Footnote 28 These works offer ways to strip ‘territory’ from some of the connotations and assumptions it has accreted over a long time and enable us to take a fresh view at such a staid concept.

However, in this article I argue that while a more thorough analysis of territory would be worthwhile,Footnote 29 IR has even more to gain by expanding its spatial vocabulary and including other forms of space into our theorising. This move allows us to denaturalise the state while also moving beyond it by broadening our array of actors and spatialities and their relation to power and authority. It also helps us revise our understanding of how large-scale social and economic change affects politics by shifting our attention to other scales.Footnote 30

The spatialities of IR

Many research communities in and around IR have begun to use a variety of spatial concepts. Following pioneering but isolated worksFootnote 31 and early poststructuralist explorations,Footnote 32 the influential and widely cited interventions by Ruggie and Agnew about territory kicked off a wave of scholarly interest in the spatial dimensions of globalisation and state reconfiguration.Footnote 33 Landmark volumesFootnote 34 evinced a ‘rapidly multiplying list of rediscovered geographies’.Footnote 35 These conceptual and theoretical engagements then fed into more detailed, issue-oriented work in different thematic fields, although this has not added up to a coherent research programme thus far.Footnote 36

Strategic Studies and other strands of ‘traditional’ international security studies have included spatial concepts from classical geopolitics like the Eurasian ‘Heartland’ and ‘Rimland’, or notions of ‘shatterbelts’ and ‘spheres of influence’ into their theorising.Footnote 37 Critical security studies, taking a cue from critical geopolitics, have analysed the development of geopolitical thought, such as the resurgence of interest in European geopolitics as a crisis of foreign policy identities following the end of the Cold War, or the spatial constructions of political identities through the prism of (in)security.Footnote 38

Core-periphery models are centred around spatial structures. They have been used for analysing power politics, North-South relations, and European Union politics, among other things.Footnote 39 International Political Economy (IPE), where such accounts first arose, also exhibits other notable spatial concepts such as ‘regulatory spaces’, supply chains, ‘geoeconomics’, or Bob Jessop's neo-Marxist ‘spatio-temporal fix’.Footnote 40

Other works emphasise the constructed nature of space. Among the central concerns of International Political Sociology has been to problematise the constitution of ‘the international’ and ‘the global’.Footnote 41 Many works on regions and regional integration also show an awareness of the constructed nature of their object.Footnote 42 Finally, there is a large and growing scholarship highlighting the constructed nature of borders and changing bordering practices in a time of globalisation and increased human mobility.Footnote 43

Issues of scale and trans-scalar interaction have also been prominently addressed by some IR writings, from the emergence of global spatialities and multilevel governance systems to feminist writings about the body and the household as sites of the political.Footnote 44 Other works have traced how local spaces are integrated into global and transnational networks of trade and governance.Footnote 45 Peace research has been concerned with regional patterns of conflict diffusion and contagion.Footnote 46 Works on peacebuilding highlight the importance of ‘the local’ and discuss the intermingling of local, national, and global politics in postconflict spaces.Footnote 47 Séverine Autessere, in her ethnography of ‘peaceland’, portrays peacebuilding spaces as separate worlds with their own social, political, and economic logics.Footnote 48

These works and others have been very helpful for our understanding of space in international relations. However, their main impetus is not to theorise space per se but to use space as a theoretical instrument to move forward debates about some other concept (such as security, global governance, or inequality). Furthermore, each approach on its own only incorporates limited aspects of spatiality. As a result, the discussions surveyed above have so far failed to coalesce into a wider conversation about space as an analytical approach in IR.

Towards a spatial approach

A fully formed spatial approach to international relations needs to fulfil four central criteria. First and foremost, it needs an ontology of space, that is, space is treated as an object that cannot be reduced to being merely an epiphenomenon of ontologically prior forces and that has a meaningful effect on other objects. Second, a spatial approach treats space as socially constructed. Notions of ‘the national homeland’, ‘sacred sites’, and ‘globalisation’ are examples how spaces are imbued with specific meanings.Footnote 49 Third, a spatial approach must speak to scales and how they relate to each other. A scalar analysis looks at spatial relations at different levels and how they are connected and entangled. Fourth, building on Edward Soja's insight that ‘social space’ is distinct from, but enmeshed in ‘both the material space of physical nature and the ideational space of human nature’, a spatial approach needs to make clear how space affects, and is affected by materiality and ideas.Footnote 50 The works surveyed above do have clear spatial ontologies but many are unclear on the social construction of spaces or the scalar embeddedness of their object of study. Few clearly relate space to material and ideational factors, with most taking an either-or approach.

Recently, Orit Gazit has proposed a sophisticated and consistent way of conceptualising social space based on the relational sociology of Georg Simmel, focusing on five qualities of space: exclusivity, divisibility, containment, positioning, and mobility.Footnote 51 Simmel's approach offers a way of understanding the mutual implication of physical and social space. Social interaction first emerges out of relative positioning in physical space (that is, geometric proximity), ‘yet once social interaction has taken place, physical space also remains as a representation of it: a symbol embodying the social encounter, encapsulating the entangled power asymmetries that stand at its basis and gaining a life in its own right’.Footnote 52 This conceptualises the physical environment both as an enabler of social contact and thereby the production of social space, and as the outcome of these social processes at the same time. However, Gazit does not extend this argument to the natural environment, focusing only on the built environment.Footnote 53 In total, although she frames her theory as a contribution to relational IR approaches, Gazit's approach is the most thorough treatment of space from an IR perspective.Footnote 54

A spatial approach to global politics

The works surveyed in the previous section do not offer a wholly compelling conceptualisation of space but make useful contributions towards this goal. Building on these debates, this section lays out a framework that conceptualises space from an IR perspective based on the four criteria presented above and lays out a practice-oriented approach to space to show how this framework can be put to use.

Spatial ontology

First, a spatial approach ascribes an ontological status to space, implying that space is no mere by-product of other social processes but that it independently exerts causal force or produces effects. It does not imply an essentialist view of space, as something that is just there, but demands that we treat space as something that has independent effects. For instance, neo-Marxist geography views spatial configurations as the product of capitalist dynamics, but it accepts that these spatial configurations affect, for example, the movement of capital and relations of production.Footnote 55

A spatial approach can employ different concepts to analyse sociospatial relations: territory, scale, place, network, body, landscape, and more. Each offers a different way of theorising space and Political Geography provides a wealth of literature detailing these concepts and their use. But relating these spatial ontologies to each other is not a trivial problem. For this, the Territory, Place, Scale, Network (TPSN) framework represents a helpful heuristic, which views territory, place, scale, and network as distinct ontologies for the analysis of sociospatial relations.Footnote 56 Advocates of a particular approach, Bob Jessop, Neil Brenner, and Martin Jones argue, tend to overly privilege it in their social ontology, thereby disregarding the utility of alternative approaches.Footnote 57 This ontological reductionism overlooks ‘the mutually constitutive relations among those categories and their respective empirical objects’.Footnote 58 Instead, Jessop, Brenner, and Jones argue for a form of sociospatial inquiry that is attentive to the interconnectedness among dimensions of spatiality. In practical terms this means that researchers should ask for each dimension how it affects or constitutes the others, and how it is in turn affected or constituted by them. Jessop, Brenner, and Jones argue that the tensions emerging between these ontologies should be seen as productive and that researchers should refrain from ‘any premature harmonization of contradictions and conflicts through the postulation of a well-ordered, eternally reproducible configuration of sociospatial relations’.Footnote 59

However, territory, place, scale, and network are not the only possible ontologies – these were just the major ‘spatial turns’ identified by Jessop, Brenner, and Jones. Other options abound. For example, feminist geographers have placed the body at the centre of inquiry, relating it to concepts like scale, territory, and place.Footnote 60 Elsewhere, Alison Mountz has argued for using islands and archipelagos as lenses through which political geography can be understood.Footnote 61 The mobilities and flows paradigm directs our attention to movement and mobile populations.Footnote 62 Finally, ecological perspectives build theories around ontologies of nature and landscape.Footnote 63

The constructedness of space

There are different ways of conceptualising ‘space’. The first is to view it in a Cartesian sense, that is, a geometric container that other things exist or happen in. Cartesianism is the foundation of geo-determinism, which is encapsulated in the old aphorism that ‘geography is destiny’. Geo-determinism was characteristic of classical geopolitics but was falling out of favour in Political Geography as early as the 1940s.Footnote 64 It was replaced by a possibilist understanding of geography, wherein geography is constant but its social impact is mediated by politics, technology, and other factors.Footnote 65 Both determinist and possibilist approaches are based on a fixed understanding of space, thereby making geography little more than a ‘territorial stage’ upon which states interact.Footnote 66

In Geography and Sociology, space is today viewed in relational and social constructivist terms, as the result of interactions among phenomena, objects, and people. Doreen Massey argues that ‘identities/entities, the relations “between” them, and the spatiality which is part of them, are all co-constitutive’.Footnote 67 Martina Löw speaks of space as ‘a relational arrangement of bodies that are incessantly in motion’.Footnote 68 Löw's use of ‘arrangement’ implies order, in spite of space's inherent dynamism. Therefore, spaces are reflective of other sociopolitical structures and why ‘social and political practices are co-implicated in different spatial manifestations’.Footnote 69 In short, spaces are constructed. While earlier scholarship in Human Geography aimed to identify spaces, its current approach is to understand the social process by which spaces come to exist.Footnote 70 This constructivist approach focuses on the process of space making and is particularly associated with scholarship in critical geopolitics, border studies, and feminist geography.Footnote 71

Spaces are not independent of physical environments, as the discussion of Simmel's relational sociology highlights. Gazit speaks of space – the ‘dynamic webs of socio-cultural and symbolic relations’ – evolving within, around, and in relation to ‘brute topographical physical settings’.Footnote 72 Stuart Elden refers to these settings as ‘terrain’, which consists of geophysical landscapes, a built environment, and their respective material and physical properties.Footnote 73 Terrain exists as part of, and in relation to human societies and is therefore malleable, constantly shaping and being shaped by social action.

In line with much geographic writing, I approach space as an abstract and general construct and other geographical concepts as more specific kinds of space. For instance, ‘places’ are spaces that have social purposes and meanings. Places are created through shared memories and are enmeshed in wider social relations; in the words of Setha Low, places are the ‘spatial location of subjectivities, intersubjectivities and identities’.Footnote 74 As other spaces, places are productive and play their part in the constitution of gender and other social identities.Footnote 75 To give another example, territory is politically controlled and bounded space. Territories have three characteristics: The first is a ‘classification by area’.Footnote 76 Second, territorial claims have to be communicated, for example by reification of a space and the symbolic marking of borders in space and on maps.Footnote 77 Third, territoriality always implies an attempt at enforcing claims of control. In sum, territoriality should be understood as ‘the attempt by an individual or group to affect, influence, or control people, phenomena, and relationships, by delimiting and asserting control over a geographic area’.Footnote 78 ‘Territory’ should not be restricted to terrestrial spaces but also look to those spaces – oceanic, atmospheric, outer space, cyberspace – beyond the familiar environment of terra.Footnote 79

Scalar perspectives

Spaces can be situated at different scales. In contrast to IR's traditional ‘levels of analysis’, geographic scales are seen as connecting and interacting rather than as separating and distinguishing.Footnote 80 Like other sociospatial ontologies, scales are products of social construction, as Sally A. Marston points out.Footnote 81 The ‘scalar turn’ in Geography directs our attention to how ‘inherited global, national, regional, and local relations were being recalibrated through capitalist restructuring and state retrenchment’.Footnote 82 Works in this tradition problematise how scales are constituted, how issues and actors move between scales and how these processes interact with other sociospatial divisions.Footnote 83 Scalar perspectives are based on vertical differentiation and look at nested hierarchies among nodes such as the division of labour along a production chain. An IR example of cross-scalar linkage is Or Rosenboim's intellectual history of the territorial nation-state, which she sees as being shaped by a ‘close interplay of the national and global political spaces in international thought in the first century of IR’.Footnote 84 Similarly, International Political Sociology views ‘the national’ and ‘the international’ as mutually implicated without collapsing everything into a singular global whole.Footnote 85

A scalar perspective is necessary to understand how spaces are rearranged. Some contributions argue that the scalarity of spaces is driven by the exigencies of capitalism, from the imperialisms of the past to today's ‘rescaling’ of formerly state-centred economies at global and local levels.Footnote 86 Michael Keating describes the shifting regional politics within the EU in the same terms, where authority moves between nation-states, substate regions, and the supranational level.Footnote 87 In more general terms: old spatial configurations never simply disappear but are replaced by new ones. The same logic applies to other sociospatial forms: Networks are frequently reconfigured to accommodate internal and external changes; places change their shape and meaning.

This is most strongly elaborated in the twin concepts of deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation. Adapting Deleuze and Guattari's original formulation of these terms, Political Geography and IR understand deterritorialisation and reterritorialisation as signifying shifts in spatial relations, especially in the post-Cold War era.Footnote 88 The geographic debate focused mainly on challenging the sociological and economic globalisation literature and its narrative of globalisation as a great deterritorialising force, which geographers felt was ‘missing the point’.Footnote 89 Instead, globalisation is thought of as a continuous and dialectic process that ‘consists of processes of deterritorialisation on the one hand and processes of reterritorialisation on the other’.Footnote 90 These processes are inseparable from each other and occur simultaneously: ‘social relations acquire other territorial configurations and boundaries even as they lose the previous ones. This means that the new territoriality of social relations, while being qualitatively different, will include vestiges of the old one’.Footnote 91

Materiality and ideas

The previous three points have established that space is constructed, but not how it is constructed. In very broad terms, there are idealist and materialist answers to that question. The anthropologist Setha Low distinguishes social construction, that is, ‘the role played by social interaction, symbols and language in giving form and meaning to physical space’, from social production, meaning ‘the history and political economy of the built environment and landscape’.Footnote 92 In Geography, the first aspect is emphasised by critical geopolitics, which focuses on the process how space is discursively constructed and examines the assumptions about space and territory that underpin the international system of states and make geopolitics possible.Footnote 93 The second aspect is most closely identified with Radical Geography and its historical materialist account of space.Footnote 94

But we should not overstate the differences between idealist and materialist approaches, especially since there are lines of compromise between the two. Soja drew on both postmodernism and Marxism to identify socially produced space as the link between physical, materially constrained space, and mental imaginations of space: ‘(B)oth the material space of physical nature and the ideational space of human nature have to be seen as socially produced and reproduced. … Conversely, [social] spatiality cannot be completely separated from physical and psychological spaces.’Footnote 95 Gearóid Ó Tuathail combines critical geopolitics’ focus on discourse with political and economic structures, describing geopolitics as being constituted through ‘geopolitical fields’ (that is, structures), ‘geopolitical cultures’ (that is, spatial imaginations) and the ‘geopolitical condition’ (that is, technologies and their impact on society).Footnote 96 In the spirit of these arguments, a spatial approach to international relations should mediate between materialist and idealist accounts, acknowledging that both forces shape global politics without trying to resolve all tensions between them, a point that is shared by writers from different theoretical traditions.Footnote 97

Idealist approaches have been instrumental in deconstructing geopolitical imaginaries and drawing out the spatial assumptions that underpin supposedly objective geographical realities.Footnote 98 Such imaginaries are transmitted through elite discourses and strategic cultures, but also through popular culture.Footnote 99 The purpose of such representations is to reify spaces by giving them a name, a shape and meaning. Visual depictions in maps or in artwork and other symbols of spatiality reinforce these constructions.

Materialist approaches refer to socioeconomic structures (for example, Marxism), to ‘material capabilities’ as power resources (for example, Neo-Realism) or the role of objects in politics (for example, Actor-Network theory), and the respective importance of these objects for politics and the construction of space is well established. But materiality has additional meanings that also must be considered here. In a crude physical sense, the environmental properties of a space matter for politics – the governance of space works differently on land, on the high seas and in outer space. Capabilities for power projection, communication, and surveillance differ dramatically between physical spaces, social spaces, and virtual spaces. As the extensive literatures on, for example, political ecology, social constructions of nature and social-ecological systems attest, the natural environment and the spatial conduct of politics affect each other.Footnote 100 This does not mean slipping back into geo-determinism or geo-possibilism but neither should we act as if the material properties of space do not matter.Footnote 101

The advancing Anthropocene will only increase the importance of environmental materiality. Climate change has different effects in different places situated in multiscalar systems and subject to global-local forms of governance. For instance, the awareness of global environmental problems like biodiversity loss, pollution, ozone layer depletion, and global warming has been instrumental in constituting a global space of risks and common concern as the debate about ‘planetary boundaries’ indicates. This shows how politics, discourse, and materiality are entangled. First, as Simon Dalby notes, humanity is not the passive victim of climate change but its driver: ‘The key point now is not what climate change will do for geopolitics, but what geopolitics does to climate change.’Footnote 102 Hence, geography and the environment are not static but things that change in relation to human agents and systems. Second, spatial constructions make reference to the environment while the environment places limitations on which social constructions are tenable, although multiple interpretations are still possible.Footnote 103

Technology is sometimes lumped into materialist categories but arguably represents a separate kind of factor.Footnote 104 Technologies can serve a variety of purposes in the construction of space. For one, technologies change our relation to space in terms of transport and communication speeds.Footnote 105 For another, technologies also allow for the control over space, with surveillance technologies producing images (for example, satellite imagery, remote sensing) and abstractions (for example, statistics, maps, cadastral systems). Technology can even be the infrastructure upon which spaces are constructed, such as pipeline networks or cyberspace.Footnote 106 Human interactions with extreme environments like the deep sea or outer space need to be mediated by technology.

A practice-oriented approach to space

The discussion above presents ways of fulfilling the four criteria of a spatial approach to IR. This section sketches a way of translating this discussion into a set of spatial practices, which avoids structuralism and determinism by focusing on people and their agency. As Margit Mayer puts it in her commentary on the TPSN framework: ‘it is never the spatial form that acts, but rather social actors who, embedded in particular (multidimensional) spatial forms and making use of particular (multidimensional) spatial forms, act’.Footnote 107 Echoing feminist notions of embodiment and performativity, it is the practical enactment of ‘minute rituals’Footnote 108 that makes spaces coalesce. I use the definition of ‘practice’ by Emmanuel Adler and Vincent Pouliot: ‘practices are socially meaningful patterns of action, which, in being performed more or less competently, simultaneously embody, act out, and possibly reify background knowledge and discourse in and on the material world’.Footnote 109 Adler and Pouliot identify five elements of practice: (1) practices are performative; (2) practices follow regular patterns without determining behaviour; (3) practices are interpreted and understood in terms of social relations; (4) practices depend on background knowledge that gives them a particular purpose; and (5) practices link discourses with the material world because the discourses give meaning to the act.Footnote 110

Practices are performed by agents – a weighty term with multiple layers and interpretations. Human beings are agents but, in some theoretical traditions, non-human objects, and assemblages can also have agency.Footnote 111 Geography has been engaging with ‘more-than-human’ agency, expanding the concept to animals, bacteria, and other forms of life, while Science and Technology Studies deliberate the agency of objects and algorithms.Footnote 112 These approaches have also informed debates in IR on what it means to be an agent.Footnote 113 Of course, agency – in whichever of these interpretations – is also constituted by structures, including spatial structures.Footnote 114 The effect of space is not just to enable or constrain action but also to affect agency itself, that is, shaping who is empowered to act in which ways in a particular setting. For example, the construction of the imperial colony as a political space made it possible, even necessary, for indigenous political agents to identify as anti-colonial activists or resistance fighters. Through their actions, they were able to push for independence and change spatial relations between metropoles and colonies.

Following Andrea M. Brighenti, a practice approach asks how agents constitute spaces through practices and how these spaces impact future practices.Footnote 115 A spatial practice can be understood as any practice whose performance is aimed at deconstructing or enacting and thereby (re)creating spaces. Jeff Malpas argues that ‘extendedness’ – a size and also an openness – is the essential characteristic of space, which also implies boundedness, that is, a difference between inside and outside.Footnote 116 This ties into other discussions through which practices spaces are constituted.Footnote 117 These discussions can be translated into a taxonomy of practices that are jointly necessary to enact a space:

1. Reification: Referring to a space as a distinctive object in discourse, giving it a name and showing it accordingly on maps and in other representations.

2. Inscription of meaning: A space does not just have an extent and a name, agents also imbue it with meaning (for example, a purpose, a history).

3. Communication of boundedness between inside and outside: Agents must be able to distinguish Space A from not-A in their everyday actions.

4. Relation to other spaces: Spaces are not singular but are practiced in relation to other spaces of the same kind (and other kinds). These relations include physical (for example, distance) and social relationships (for example, comparison).

This conceptualisation of the spatial ‘inherently implies the existence in the lived world of a simultaneous multiplicity of spaces: cross-cutting, intersecting, aligning with one another, or existing in relations of paradox and antagonism’.Footnote 118 It also accords agents a substantial role in how these processes play out in concrete instances. However, spatial arrangements arising from these practices are only momentary outcomes of social interaction. They may be the aim of deliberate strategy although, given the complexity of such an endeavour, the outcomes of such moves are uncertain.

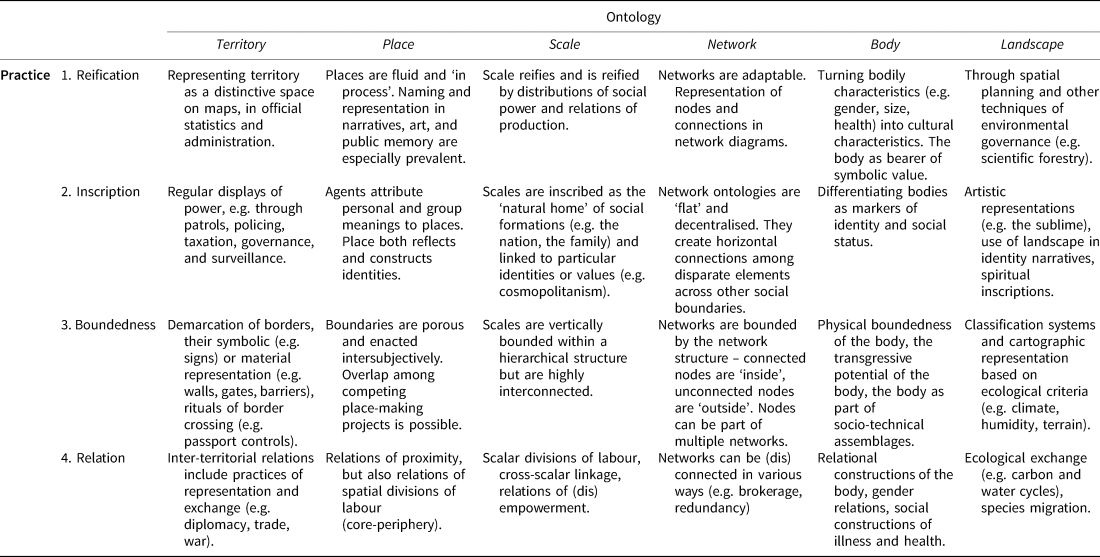

By choosing a specific sociospatial ontology, these practices can be specified further. Drawing on Jessop, Brenner, and Jones and other relevant literature, Table 1 shows sample ways how the taxonomy of practices can be adapted for six different ontologies – territory, place, scale, network, body, and landscape.Footnote 119

Table 1. Spatial practices across different ontologies.

A spatial inquiry can either adopt a single ontology or, following Jessop, Brenner, and Jones, explore their object through the intersection of different ontologies.Footnote 120 Jones and Jessop introduce the notion of ‘(in)compossibility’, that is, the (im)possibility of certain configurations of spatiality within a certain setting.Footnote 121

Arctic Security research

To offer a brief illustration of the above conceptual framework and show how a spatial approach can be useful for IR, this section discusses the evolution of Arctic Security research. I chose Arctic Security research because of its relatively recent inception and fast evolution into a cross-disciplinary enterprise centred on a spatial approach.Footnote 122 Understandings of security inevitably have spatial dimensions, from scalarity (whose security?) to their relational character (from whom must security be protected?), leading to the emergence of what might be called ‘securityscapes’. The Arctic is also interesting in that its sparse population – only four million people permanently live inside the Arctic Circle, that is, north of the 66°33′ line – and the extreme environmental conditions mean that conventional security practices must be adapted. Governance is by necessity more distant and detached, mediated by technologies of surveillance and control.

The spatial approach to the Arctic

The Arctic used to be a region at the margins of global politics, an ‘empty stage’ on the periphery of the Cold War.Footnote 123 But after the end of the Cold War and with the thawing of the polar ice sheet, research on the region has increased significantly. Standard IR accounts analyse the region in terms of the international politics of conflict and cooperation, whether it be from a Realist, an Internationalist, or a Constructivist perspective.Footnote 124 These works have made useful points but they use a state-centric, territorial framework that is inattentive to ‘the diversity of material and political spaces that define the Arctic’ and that exogenises climate change and environmental factors.Footnote 125 Without wanting to argue for some kind of Arctic exceptionalism, the Arctic is an unusual space where the material properties of the environment need to be foregrounded. Hence, a spatial perspective tells the story of the Arctic differently, exploring ‘the continual “spatialisation” of the Arctic, the ongoing making of a region through a diverse set of practices’.Footnote 126

First, ‘the Arctic’ is treated as a spatial ontological concept.Footnote 127 Second, scholars acknowledge the constructedness of the Arctic, both in terms of geographic area and meaning.Footnote 128 Where the Arctic used to be a ‘frozen wasteland over which intercontinental missiles might fly’,Footnote 129 it has now ‘become a showcase of how quickly wholesale discursive constructions of a region can change’.Footnote 130 Third, much of Arctic security research takes a multi-scalar or cross-scalar perspective, which is detailed below. Fourth, several works explicitly discuss how ideas and the materiality of the Arctic jointly influence practices of space making. Corine Wood-Donelly has explored how Arctic states ‘perform’ effective occupation through the visual and symbolic representation of ‘Arctic-ness’, for example on postage stamps.Footnote 131 Other authors discuss how economic and political infrastructure (for example, ports, radio stations), or the lack thereof, shape regional politics.Footnote 132

Spatialities of the Arctic

We can approach the multiple spatialities of the Arctic through the various spatial ontologies discussed in the previous section. This is not merely an analytical move – all of these ontologies inform various actors’ spatial practices. This is very evident for territory that forms the bedrock for most state approaches to the Arctic. A territorial ontology informs the creation of sovereign spaces on land and in coastal waters, maritime spaces like Exclusive Economic Zones and Search and Rescue Zones,Footnote 133 as well as extended continental shelf claims, some of which are strongly contested.Footnote 134 Arctic states, as ‘settler colonies’, can also be conceptualised in terms of (post)colonial relations.Footnote 135 Furthermore, a territorial ontology informs the politics of substate autonomy and self-government for indigenous communities, for whom land also has a cultural importance, thus creating a conceptual overlap with notions of place.Footnote 136 But territorialisation also introduces tensions – for instance, Inuit spatial constructs of Canada and Northern Greenland more closely resemble a network ontology than a territorial one.Footnote 137

Literature on the Arctic as place often foregrounds indigenous communities and their ways of relating to the world. A ‘place’ ontology is typical of much anthropological work in the Arctic that reconstructs how people's sense of place is connected to environmental conditions and mobilities, relating place to landscape ontologies and demonstrating the scalar embeddedness of place. Kirsten Hastrup shows how spatial practices of mobility in Greenland were determined by the precariousness of life in a hostile environment.Footnote 138 Practices of place also affect conceptions of security, which, for Indigenous peoples, relate to environmental protection, cultural preservation, and political autonomy.Footnote 139 Indigenous place making has also been greatly affected by state security interventions such as mapping and territorialisation, settlement programmes, or military base construction.

Looking at the Arctic through a scale ontology offers different ways of contextualising Arctic security. One is to situate state-level Arctic politics within global politics more broadly.Footnote 140 For example, Robert W. Murray argues that territorial conflict in the Arctic cannot be disentangled from broader global realignments, and Heather Nicol makes a similar point about the regional economy.Footnote 141 Pauline Pic and Frédéric Lasserre show how discourses of ‘Arctic security’ now envision the Arctic on a more global scale rather than as a self-contained regional system.Footnote 142 This is representative of an emerging discourse about ‘the scalar blending of Arctic and global actors and processes toward what has become known as the “global Arctic”’.Footnote 143 Another way is to focus on micro- and meso-level dynamics, shifting the referent object of security away from the state.Footnote 144 However, Emilie S. Cameron rightly cautions that notions of ‘the local’ are often too readily equated with indigeneity.Footnote 145 Scale can also be approached in dynamic terms. For instance, Rune D. Fitjar shows how changing resource geographies (for example, the discovery of new hydrocarbon resources) cause rescaling through region building.Footnote 146

Scalar perspectives mesh well with network approaches that work across territorial boundaries. Networks of actors like coast guards, indigenous groups and scientists play important roles in Arctic politics.Footnote 147 By expanding its circle of non-Arctic observer nations, the Arctic Council is redefining the Arctic as a ‘supranational political space’, placing it at the centre of a growing network of states that ‘have not traditionally been considered Arctic’ but are ‘very much connected to the Arctic’.Footnote 148 Oran R. Young argues that the Arctic ‘has moved from the periphery to the center with regard to matters of global concern’.Footnote 149 The Arctic is also embedded into global value chains, especially in fisheries and extractive industries. For the latter, oil and gas pipeline networks represent a crucial infrastructure connecting Arctic extraction sites to further economic activity thousands of kilometres away.Footnote 150

In the Arctic, the body is not just important in its social sense but also in its bare physical aspect – its ability to withstand cold and darkness, the bodily risks of icy waters and the psychosomatic effects of isolation and confinement in small habitable spaces. Hence, mid-twentieth century military research programmes on survival and the effects of exposure constructed the body as ‘a vessel through which ideas of Arctic geography could be expressed’.Footnote 151 Feminist contributions highlight the gendered perceptions of bodily security in Arctic, for example, the need for food, shelter, and physical safety.Footnote 152 Bodies are also important as metaphor – in depictions of the Arctic, images of the heroic masculine explorer taming a feminised, ‘pristine’ Arctic wilderness have long featured prominently.Footnote 153

The ‘wilderness’ discourse has been very influential in landscape approaches to the Arctic, from the earliest days of European contact to modern depictions.Footnote 154 Katrín A. Lund, Katla Kjartansdóttir, and Kristín Loftsdóttir present Icelandic tourism as an example how landscapes are mobilised and performed in the production of a country's image and identity, thereby underlining the entanglement of landscape and placemaking.Footnote 155 Landscape ontologies are also very popular in physical geography as well as in political ecology and environmental governance approaches.Footnote 156 Their use for an analysis of the social dimensions of climate change is obvious, especially when viewed in terms of social-ecological interaction.Footnote 157

As this brief review demonstrates, a spatial perspective illuminates Arctic security from different angles. Using different spatial ontologies makes us aware of the linkages and tensions between different spatialities, for example, regarding the impact of state territorial projects on the human security of indigenous populations.Footnote 158 It also makes clear that exclusive territoriality is not the only spatial frame through which the Arctic can be usefully approached.

Conclusion

This article sketches a conceptual framework building on contributions from Political Geography for a more rounded and sophisticated engagement with space in global politics. The points raised in this article would have to be elaborated in more detail to be directly applicable for practical research but the central idea of a dynamic understanding of space should have become clear. As products of social construction, spaces are never fixed but adaptable, even mobile. However, as arrangements of bodies and objects, they are at the same time comparatively stable social facts. Hence, there is more to be learned about the circumstances and causes of spatial stability and change in global politics.

Arctic Security research demonstrates how a spatial approach can be used to analyse politics through different spatial lenses. While Arctic Security research developed around a spatial approach from its inception, a spatial approach can also be used to re-evaluate earlier work and thereby provide a more nuanced picture. In fact, this is standard practice in many fields surveyed in this article. Feminist scholarship, critical security studies, and international political sociology, to use but a few examples, developed new spatialities through the deconstruction of hegemonic understandings of territoriality.Footnote 159 Other fields could draw inspiration from these examples by taking a critical view of their spatial assumptions and foundations.

To be sure, the way of theorising space outlined in this article is not the only possibility. While my approach should be intelligible to scholars from different theoretical paradigms and substantive fields, there are bound to be disagreements. Given the pluralism of contemporary IR, anything else would be a surprise. But my aim is not to provide a master blueprint for all subsequent works but to show how space can be fruitfully theorised in a way that is compatible with broadly constructivist IR ontologies and theories. In sum, this article argues that more research communities within IR should adopt a spatial approach to question their spatial assumptions and to build better theory using more appropriate sociospatial ontologies. It also advocates for theorising ‘space’ from an IR perspective. Even in Geography, the concept of space does not get a lot of attention, so there is scope for an interdisciplinary conversation.Footnote 160

Acknowledgements

Research funding by the German Research Foundation (Grant No. LA 1847/11-1) is gratefully acknowledged. I thank the editors and reviewers for their helpful comments, and Carlo Diehl for editorial assistance.