In early modern France, before the ascent of banks, the volume of mortgage debt was equal to 10 per cent of GDP in 1807, a percentage highlighting the vitality of early financial markets (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2012). This figure, however, is only the tip of the iceberg, mostly because the calculation is based solely on transactions extracted from notarial records. In early modern France, as well as in Spain or Italy, the notary registered and archived several types of loan agreement, such as obligations and annuities. These records have helped historians to draw a sophisticated picture of early financial French markets, assuming that people lent and borrowed money primarily via these notarial intermediaries. Lately, however, this picture has been nuanced (Ogilvie et al. Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012). While notarial obligations and annuities played a critical role in the allocation of credit, in the circulation of capital and the backing of investment, non-notarised – and often undocumented – transactions have also come to be seen as significant. These private agreements, often between private individuals, were contracted outside the notary's scope. So far, however, these non-notarised credit networks and markets have been unduly neglected.

The aim of this article is twofold. First, it explores the world of non-notarised financial transactions and networks, highlighting their characteristics and mechanisms. Often considered merely as simple daily transactions made to palliate a lack of cash in circulation and smooth consumption, the examination of these transactions reveals not only that they served various purposes, including productive investments, but also proved to be dynamic. Secondly, this article proposes to compare non-notarised transactions with notarised ones through the study of probate inventories and notarial records respectively. It is possible, thus, to compare these two credit circuits, their similarities and different characteristics and their various networks features. I am especially interested in how the non-notarised credit market compared to the notarial one in terms of volume, actors, purposes and networks. This article argues that non-notarised credit transactions surpassed notarised loans in number and volume. The size of the capital market in pre-industrial France was certainly larger than historians have estimated thus far.

In order to explore these questions, I have selected the probate inventories and notarial records of a rural area in southern Alsace, between 1770 and 1790.Footnote 1 The notarial records are continuous throughout the period studied. As often with probate inventories, it is challenging to estimate their representativeness. Some villages are missing from the sample, for example, and not all decedents had their estates evaluated. But the number of probates in the sample is sufficient nonetheless to offer a compelling picture of the rural credit market in the area studied. The first step (Section i) is to present the socio-economic characteristics of the selected area, the seigneurie of Florimont, with special reference to wealth and available credit resources. A second step (Section ii) is to study the various characteristics of the non-notarised credit market revealed by the analysis of the probate inventories. Section iii provides a comparison between the non-notarised credit market and the formal notarial credit market. Section iv concludes.

I

The seigneurie of Florimont was located in the extreme south of Alsace where agriculture and livestock farming constituted the main activity and the main source of revenue for its dwellers. Approximately 90 per cent of the inhabitants carried out some kind of agricultural activity. A small textile industry developed throughout the early modern period, but the revenues it generated – if any at all – remained marginal. Several peasants did combine diverse activities, supplementing their income from different crafts. Seigniorial agents, members of the clergy and the nobility represented only a handful of households. It is worth noting too that the noble family owning the seigneurie was a modest one. The seigneurie counted a dozen villages for a total of roughly 1,500 inhabitants in the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Location of the seigneurie of Florimont

Before we turn to the examination of the credit markets, it is important to underline a few features concerning the wealth of the seigneurie's inhabitants, since wealth often correlates with both the dwellers’ need to borrow and/or their capacity to extend loans. Unfortunately, we lack accurate data on this. In the absence of proper tax registers for this area, probate inventories provide a good indication and allow for the reconstruction of households’ wealth. Our dataset contains 116 probate inventories for the period 1770–90. Rural inventories like those of Florimont did not always mention the value of items and properties listed. The total wealth can be calculated for only 34 households (median: 4,186.5 livres tournois, mean: 5,758.1 livres tournois). This can be explained by the fact that seignorial officers drafting the probate inventory performed an assessment of the estate's value only when it was necessary to divide the estate between the legal heirs. For many households this division occurred through informal negotiations between the heirs; they often chose not to pay an extra fee for the estimate. It was also the case that the assessment was performed at a later stage in a separate document, often not archived with the corresponding probate inventory. Therefore, the worth of assets and items was included only sporadically. As stated above, I was able to find this extra documentation regarding the estate's division when it accompanied the probate inventory for only 34 cases.

This bias, however, can be circumvented. In early modern Europe, and in France in particular, land was considered as the most valuable asset for rural dwellers. In the seigneurie of Florimont, peasants cultivated arable land and grew cereals such as rye, barley and to a lesser extent wheat. The area of plots was usually recorded in the probates, although we must consider that the officer's estimate was approximate (Colney Reference Colney1989, p. 306; Varry Reference Varry1994).Footnote 3 Land, therefore, can be used as a proxy for wealth.Footnote 4 For those dying in old age, the land variable could potentially be skewed, since they might have opted to pass on their assets early to their heirs. Yet correlation between age and quantity of arable land is not significant; age at death, therefore, did not have consequences for the amount of land owned.

The wealthiest household owned approximately 100 journeaux of arable land, while the mean was 14.53 journeaux. Most households did not own more than 20 journeaux of land, roughly the equivalent of 6 hectares. Several households owned no land at all. As these households also owned few movables and livestock, it is plausible to confirm their status as landless and consider them as poor households.

Figure 2. Distribution of land per household expressed in journeaux (probates dataset)

Compared to the village of Schillersdorf in northern Alsace, the peasants of Florimont owned significantly more land. But Jean Michel Boehler suggests that a return of 7 to 8 per cent on arable land was common, as opposed as 15 to 20 per cent for vines, such as in the village of Schillersdorf, which can explain the difference (Boehler Reference Boehler1995, pp. 901–15).

It is also important to specify that the seigneurie practised partible inheritance. Regardless of sex, legitimate heirs were entitled to an equal share of their parents’ estate. Research has shown that both men and women were either endowed or inherited the same quantity of land (Dermineur Reference Dermineur, Daybell and Norrhem2016). Women could own capital in the form of land and by extension have access to the credit market.

In early modern rural France in general, and in the seigneurie of Florimont in particular, several channels of credit coexisted: on the one hand the institutionalised credit market embodied by the notary, and on the other hand the non-institutionalised channel.

Institutionalised credit transactions took place mostly through the notary, a seigneurial or royal officer in early modern France. The notary was bound to apply laws and rules enacted by the central authority. Through the early modern period, the French crown had granted greater prerogative powers to notaries.Footnote 5 From 1666 owards, with the reform of justice, loans of more than 100 livres had to be registered before the notary against a fee or had to be written down between private parties (Isambert Reference Isambert1829, p. 137). This legal disposition underlines the effort of the state to rule out verbal agreements and control the flux of exchanges. But it does not seem that peasants took up the habit of registering their loans with the notary on a regular basis before the beginning of the eighteenth century (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2018a).

Non-institutionalised credit markets, on the other hand, were those that developed outside the scope of the authorities, and were not subsidised, regulated or supervised in any way (Lindgren Reference Lindgren2002, p. 813). Intermediaries could take part in the negotiations, but these brokers were not representatives of the state or of the local authorities. However, it is important to note that these private agreements could be enforced by the judicial authorities provided they followed the rules applying to financial transactions. Private written agreements constituted strong evidence before the judge. Verbal agreements could also be enforced through the justice system, but parties had to bring witnesses to defend the legitimacy of their claim. The reform of justice in 1666 made it difficult to present witnesses in cases of debt disputes. Agents began to privilege written agreements in the late seventeenth century. Many small credit transactions between individuals still elude us because they were not archived (Pfister Reference Pfister1994, p. 1342). Creditor and borrower often knew each other and were bound either by family ties or by geographical proximity; they often exempted themselves thus from the burden of registering their transaction. We can track part of these transactions with the help of the probate inventories, via either promissory notes called ‘contrat sous seing privé' or references to account books. The amounts exchanged were also often small and did not necessarily require the official and charged seal of the notary for the promise to be respected. These exchanges probably involved more flexibility in terms of negotiations regarding the terms of the contract, especially when it came to interest rates outside any official regulations.Footnote 6 Besides these non-notarised loans, which included the transfer of cash from the lender to the borrower, one can find other types of transactions. Deferred payments, for example, were also a form of loan. Craig Muldrew (Reference Muldrew1998) argues that these were not subject to any interest rate in early modern England. Recently, James Shaw (Reference Shaw2018) has demonstrated that interest rates were often hidden in any sort of transaction. It seems reasonable to assume that an immobilisation of capital requires a form of compensation, valued either in the form of an interest rate or as a future exchange of services.

Religious institutions, such as hospitals, religious orders and parish vestries, constituted another institutionalised channel of credit (Craddock Reference Craddock1991). Locally, parish vestries in each village allocated resources and extended money. Very few studies have examined their transactions, largely because they are outshone by the richness of notary records but also because many parish vestry records have been destroyed and/or lost. Yet the parish vestry credit activities are extremely interesting, as we shall see.

Other channels of credit, such as pawnbroking, gravitated towards the margins of the institutionalised credit market. For rural communities, we lack documentation on this as many of these transactions were in fact oral or agreed privately. When the 60-year-old bachelor Joseph Berlincourt died in March 1780, his inventory contained several pieces of women's jewellery and gold objects. These were deposited by Samuel Levy and his wife, a couple of Jewish livestock farmers living in a nearby village, as securities for a loan.Footnote 7 Without the inventory, we would not have had evidence of such a system. Out of the 116 probated estates, only one indicates a form of pawnbroking exchange.

With different options to hand, why did people privilege one channel over another? Why did they choose to secure a loan through the notary or privately? In order to answer these questions, we need to focus on the non-notarised credit market.

II

Probate inventories constitute one of the best sources with which to examine non-notarised credit markets and networks. Upon the death of an individual, a probate inventory was written to assess the extent and worth of the decedent's estate. Besides the real estate, various types of land, livestock and movables, we might also find a list of liabilities and claims. This list usually contained the names of lenders and borrowers, their place of residency and the sum owed. In seventeenth-century England, Peter Spufford estimates that 81 per cent of the decedents left debts to their heirs at their deaths (Spufford Reference Spufford and Taffin1994, p. 1361). In eighteenth-century Cape Colony, more than 65 per cent of inventories showed evidence of household involvement in the credit market, with more than 40 per cent being both lenders and borrowers (Fourie Reference Fourie and Swanepoel2018, p. 15). For the period 1770–90, I have found 116 probate inventories for the villages of the seigneurie of Florimont. These probates feature 1,070 transactions worth a total of 107,207.64 livres tournois, approximately 9 debts per inventoried person. Of the 116 probated estates, only 33 left a positive balance (28 per cent, assets minus liabilities), the mean per probated estate equalled -276 livres tournois. Jean Claude Dadey and his wife Marie Jeanne Jeantine are the most indebted of all decedents in the dataset. They present a negative balance of -5,428.45 livres tournois. However, the couple left an estate worth 26,902 livres tournois to their heirs, including a couple of houses ‘covered with tiles’, 34 journeaux de champs and two ponds full of carp. One of the wealthiest couples of the community could also be the most indebted. But their example remained unusual. The dominant pattern was rather that the wealthiest landowners were usually the ones with the biggest asset portfolio (correlation is positive for land ownership and amount in claims, R = 0.464).

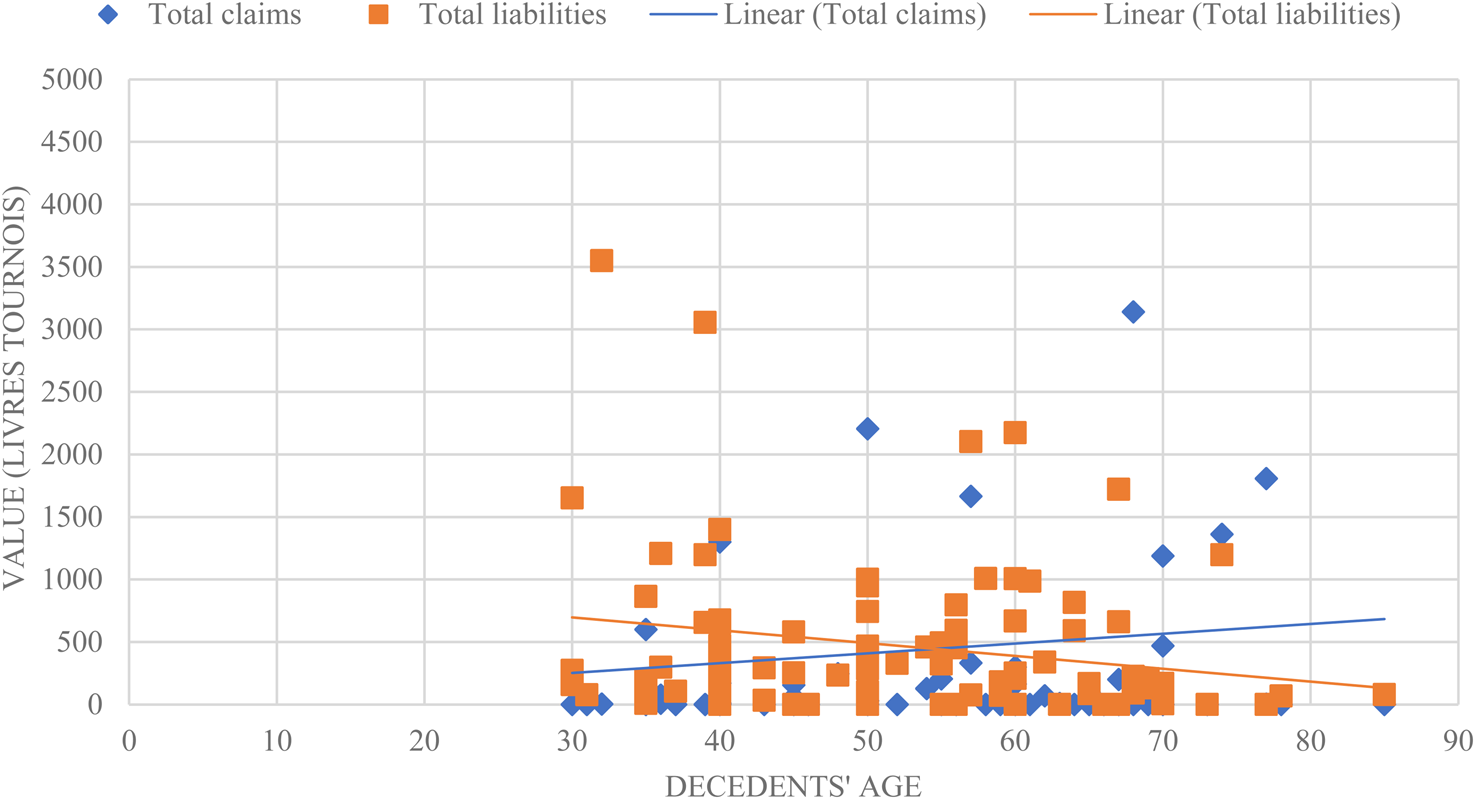

In eighteenth-century Florimont, probate inventories were not individualised. They usually assessed the worth of a household's estate, merging the wife's and husband's assets into one after the death of the last surviving spouse. Only 5.17 per cent of the decedents in the dataset were reported never to have married. Most probate inventories in fact concerned married households with legitimate heirs. In the dataset, the decedents were between the youngest at 31 years old and the oldest at 85, with a mean equalling 52.9 for the 93 I was able to track in the parish registers to determine their age. For these individuals, logically, their households tended to have slightly fewer debts and more outstanding claims than younger households (Figure 3). In particular, widows often extended money in order to secure a retirement income after the death of their husbands (Dermineur Reference Dermineur, Daybell and Norrhem2016).

Figure 3. Age of the decedents and debts in the informal credit market in Florimont, 1770–90 (probates dataset)

Evidently, probate inventories present several challenges as source material (Kuuse Reference Kuuse1974; Lindgren Reference Lindgren2002). Probate inventories give only a partial and residual picture of the credit market. Out of the 116 probated estates in the dataset, only 10 did not appear to have left any debt (8.6 per cent).Footnote 8 Decedents tended to be older than the rest of the living population, which in turn could skew their indebtedness level and their saving capacity. Probate inventories also undermined the role and activities of women in financial transactions. It seems that the officers preferred to list the names of the household's head rather than the individual at the origin of the transactions. Therefore, the women listed in the probates as lenders or borrowers tend to be widows or unmarried woman rather than married women (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2018b).

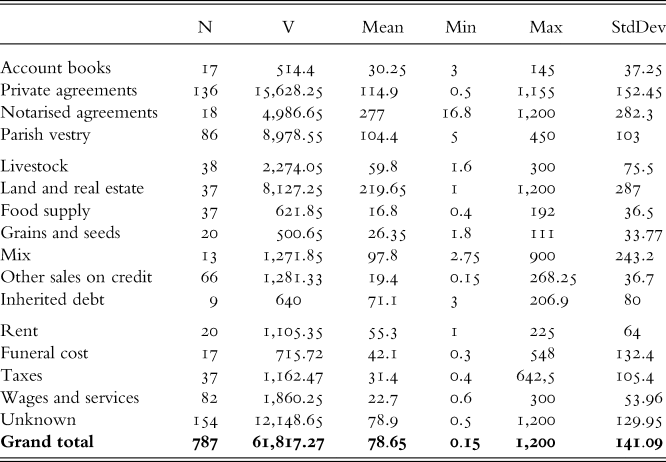

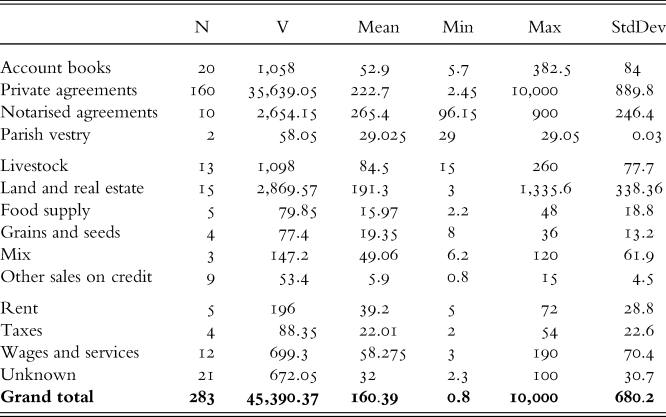

The 116 probate inventories in the dataset reveal a high level of indebtedness per household. The number of liabilities was higher than the number of claims by almost three times (see Table 1). The average liability debt was 78.6 livres tournois or the equivalent of 323 grams of silver.Footnote 9 A journeyman builder could earn 5.5 grams of silver a day in Strasbourg and a building labourer could earn the equivalent of 3.7 grams of silver a day; the average debt in Florimont thus ranged between approximately 58 and 87 working days (Allen Reference Allen2001, p. 416). The average claim was 160 livres tournois, the equivalent of 664 grams of silver, between 120 and 179 working days. Other studies estimate that the annual revenue of a small-scale farming household equalled 250 livres tournois, while day labourers and rural servant households could earn about 160 livres tournois a year (Morisson and Snyder Reference Morrisson and Snyder2000, p. 66). While the general level of debt was high, one can hardly refer to it as over-indebtedness. This result corroborates the data for the rural German town of Wildberg (Ogilvie et al. Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012). In eighteenth-century Champagne, the average household debt equalled 182 livres (Brennan Reference Brennan2011, pp 181). Elsewhere in Alsace, indebtedness reached even higher spikes. In the sector of Brumath, north of Strasbourg, indebtedness represented between 38 and 75 per cent of the households’ wealth, depending on the villages. In the Sundgau, closer to Florimont, farmers’ indebtedness equalled more than 65 per cent of their estimated total wealth (Boehler Reference Boehler1995, p. 213). Comparisons are difficult to establish; the credit market of each community was profoundly dependent on its own specific local economic features, type of agriculture and local trade, etc.

Table 1. Overview of claims and liabilities in the seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90 (based on the probates dataset)

Incidentally, it is worth mentioning that only 22 households declared cash (mean = 14.4). The low level of cash readily available could partially explain the high levels of credit. However, one cannot exclude the possibility that the surviving spouse simply ‘omitted’ to declare the coins left by the decedent.

It is a common assumption that probate inventories listed only small debts, mainly consumption related. Ogilvie et al. (Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012) have shown that borrowing in seventeenth-century Wildberg made it possible not only to smooth consumption but also to finance investments. Why did the people in Florimont borrow money? Was it to smooth consumption? One would assume that would perhaps be the case, since notaries were traditionally the main channel to secure investment transactions (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2001).

The Florimont manor's probate inventories often briefly mentioned the reason for debts but without giving details on the terms of the agreement. There is almost no information available on the length, the conditions of repayment or the interest rates in most instances. Debt transactions had a purpose recorded in 84.12 per cent of the cases. Only 15.8 per cent of the debt did not mention the nature of the debt, an unusually low proportion. In Wildberg, only 46.5 per cent of inventoried debts by value recorded a clear, specific purpose (Ogilvie Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012 et al., p. 143). In Cape Colony, only a third had a specific purpose recorded (Fourie Reference Fourie and Swanepoel2018, p. 17). While the nature of the debt can be identified, the cash loan destination often remained a mystery.

Liabilities and claims are presented together in Table 2. In Tables 3 and 4, they are presented separately. In this particular network, one observes very few reciprocal debts (16 in total between 8 individuals, 1.5 per cent of all the exchange), which allows us to use the terminology ‘debt’ or ‘financial transaction’ to refer to the claims and liabilities without distinction. The transactions are divided according to their nature and purpose. This method is not fully satisfactory as it leaves room for ambiguity. It does, however, pinpoint some important features regarding credit and debt in rural Florimont.

Table 2. Purpose and value of debts (claims and liabilities), seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90 (probates dataset)

Table 3. Purpose and value of claims, seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90 (probates dataset)

Table 4. Purpose and value of liabilities, seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90 (probates dataset)

The category ‘private agreements’ is the most numerous (27.6 per cent) and voluminous (47.8 per cent) with 51,267.3 livres tournois in total (see Tables 2, 3 and 4). Under private agreements one finds all sorts of written contracts such as billets, cédules, promesses, etc. Only a handful of verbal agreements have been recorded. Interestingly, the clerk listed these transactions in probates, trusting the good faith of the claimant. What was the nature of these private agreements? It is challenging for the historian to understand precisely whether these were loans in cash or simply sales on credit sealed by written evidence. According to the evidence at hand, one can hypothesise that these transactions were in fact mostly loans in cash and mainly consumption related, to make ends meet and pay various types of obligations (interest rates, rents and taxes), or to make small investments (small livestock for instance). Many of them mentioned an interest rate, and/or bear terms that clearly indicated a loan in cash. Pierre Bettevy lent money to his neighbour for him ‘to repay Monsieur Tissot’, the priest of the community.Footnote 10 Henri Tisserand lent 3 livres to his sister to pay her taxes.Footnote 11 Joseph Berlincourt lent Pierre Jolié some cash ‘to repay a Jew from Durmenach’.Footnote 12 Overall, most of these private transactions were small and under 50 livres tournois (42.9 per cent); and 22 per cent were between 50 and 100 livres tournois. Presumably, because these transactions were small, the parties did not find it necessary to add extra notarial fees. These transactions usually bore interest even if their amounts were small, although we cannot totally exclude the possibility of another form of compensation for the delay in repayment, whether in kind or in the form of services. The mean age of these still unrepaid private agreements is 7.9 years, a rather long time to wait to be repaid without compensation. The mean age for these debts also indicates that small loans were not necessarily short-terms ones.

Account books also featured small debts. In towns and cities, artisans, retailers and better-off households often had an account book to help them keep track of their affairs (Smail Reference Smail2016, p. 93). Often, the two accounts columns were not filled in properly. In fact, these books featured erratic and cryptic entries (Hardwick Reference Hardwick2011, pp. 90–1). In traditional communities, where the literacy rate was supposedly low, people carefully archived their transactions in bundles in wooden boxes. In the eighteenth century, however, not only did better-off peasants have an account book, but increasingly others did too. And in the late eighteenth century, most households kept track of their expenses, financial assets and income in writing, either in account books or in the form of bundled papers. Jean Baptiste Bichet, the innkeeper of Puis, kept a ‘livre journal’ to keep track of his clients running tabs. When he died, several individuals were listed as his debtors for a lump sum of 136 livres tournois.Footnote 13 Most of the debt reported in account books was small (mean = 42.5). We can hypothesise that these debts were mostly consumption related for small items or products exchanged.

Interestingly, notarised agreements represent only 7 per cent of the total volume (2.6 per cent in terms of number). None of these contracts match the dataset of notarial obligations for the same period. This can be explained by the fact that some loans were made before 1770. But it could also be the case that peasants labelled ‘obligations’ what appear to be annuity contracts. In 1785, Anne Marie Berberat died. The ‘fabrique’ – or parish vestry – of her village recalled three obligations she had signed respectively in 1740, 1775 and 1781 worth a total of 379 livres tournois and 6 deniers, with the interest of the last three years amounting to 56 livres tournois and 18 deniers.Footnote 14 Parish vestries extended capital only through an annuity contract backed up by a specific piece of land. But the scribe, like most people in the seigneurie, called these contracts ‘obligations’.

Parish vestry contracts accounted for 8.2 per cent of the debt in terms of number and 8.4 per cent in terms of volume. In early modern France, each parish had a parish vestry. This organisation, run by lay people, managed the assets of the church locally. Note that it differed from its English counterpart in terms of organisation and scope. In France, a parish vestry's main purpose was to deal with the maintenance of the building and cemetery. The budget was based on two types of revenue: first, the revenue from collections during services, funerals, bench rental, sale of fruits or grass from the cemetery, for instance; second, the vestry also collected revenue by renting land bequeathed by the faithful and from the annual payment of annuity contracts extended to hundreds of individuals in the community. Part of this money went towards the repair and maintenance of the parish church; it was also used for the purchase of candles, religious ornaments, payment of the priest for the service of the mass, and payment to the administrators of the parish vestries. As the revenue could exceed expenses, the administrators were able to lend cash to individuals. In order to respect the church rule on usury, only annuity contracts were accepted. Peasants pledged a piece of land to the fabrique in exchange for capital received; every year they paid the parish vestry a rente. This explains the low mean for these debts in our sample (mean = 102.7), compared to notarised contracts and private agreements. In some probates, only the interest was due while in others, the fabrique asked for the repayment of the capital. This can be explained by tricky inheritance situations where the land pledged had to be divided or sold. These loans were usually long-term agreements, spread over several generations.

Borrowing to invest in land or real estate represented an important sector of debt, with a mean of 202 livres tournois per debt (10.25 per cent of the total volume). The loan was either a deferred payment to the decedent himself for the pieces of land sold, or a debt owed by the decedent, and rarely to pay a third-party seller. Traditional historiography has often assumed that peasants borrowed funds to invest in land through long-term credit instruments, often notarised and secured as annuities.

Livestock farming was a popular activity in the area. Pigs, cows and horses were traded and exchanged either privately or at local fairs. Before dying in 1772, Elisabeth Moitrissier bought a cow from her neighbour Nicolas Jeantine for 60 livres tournois. She could not pay the entire amount outright; the payment was simply deferred.Footnote 15 Like most people, she would pay for the cow in several unprompted instalments. Her probate inventory does not specify an interest rate, but previous research has shown that it was often either paid on the side or included in the price (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2018a; Shaw Reference Shaw2018). In this case, as for most of the cases in the dataset, it is impossible for us to know the terms of agreement between the two parties.

Wages and services represented 2.4 per cent of the debts by value but 8.8 per cent of the number. In 1784, Nicolas Cordonnier came forward after Jean Jacques Meyet had died and recalled that he had helped the decedent to plough some of his land, a service Cordonnier estimated being worth 8 livres tournois.Footnote 16 Domestics also recalled their dues, often after their master had died. In the eighteenth century, service-oriented labour developed. An increasing number of young unmarried men and women joined neighbouring farms to work for a few years before marriage. The capital accumulated often served to optimise their chances on the marriage market and start a household on their own. As proto-industry developed, some of these young people found employment in neighbouring towns as textile workers (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2014).

The distinction between consumption-related debts and others appears useful. The proportion of deferred sales (livestock, land, food supply, grains and other sales on credit) represents 24.3 per cent of all the debts in terms of number and 17.1 per cent in terms of volume. If we subtract deferred payments for livestock and land, as these debts were not exactly consumption related but more oriented towards production, then the proportion is even lower. Jean Jacques Chellet had run up a bill when he bought oil and tobacco for 1 livre tournois and 16 deniers from a merchant in a neighbouring village.Footnote 17 Catherine Dadey had bought ‘deux livres de laine’ or wool for 16 deniers from her neighbour.Footnote 18 Generally, these purchases on tab were of little value as the means for food supply, grains and other sales on credit remained below 25 livres tournois. It is difficult to make valid comparisons as historians have not used the same method to categorise debts. Fourie found 20 per cent of debt had been incurred for consumption purposes in the Cape Colony in the eighteenth century (Fourie Reference Fourie and Swanepoel2018, p. 17). In seventeenth-century Wildberg, Ogilvie et al. found figures similar to those in Florimont.

It seems that the inhabitants of the seigneurie of Florimont borrowed via non-notarised circuits to ease the lack of cash in circulation and to make investments primarily in land and livestock. These results are in line with what Fourie has found for Cape Colony and what Ogilvie et al. have found for Wildberg.

One needs to remain cautious with these data. Some debts were directly related to the decedent's illness and his upcoming death. Funeral costs and medical expenses were clearly debts contracted for these reasons. I have left those credit relations in the dataset for two reasons. First, nearly all decedents had funeral costs reported in their inventories in the dedicated column as a lump sum of money. Secondly, as some funeral costs were listed as liabilities, they represented de facto a relationship between two individuals. Additionally, some liabilities contained in the category wages and services could also be related to the person's illness or incapacity before his death. Credit relations of this type occurred evidently only because of death.

Finally, the probate inventories of Florimont mentioned a few inherited debts. It is a very low figure and it is unlikely that such inherited debts were not more numerous, especially considering the high level of indebtedness of most households. It could be the case that these debts were not registered as such in the probate inventories. I have found evidence that inherited obligations were renewed at the notary. For unregistered debts, such as private transactions and oral agreements, either they were tacitly renewed without documentation or they appeared listed as informal loans.

Private loans in cash contracted outside the notary's authority were thus important and perhaps underlined the defiance of the rural population towards the notarial institution. More importantly, for each registered obligation or other financial instrument, the notary applied a fee that evidently could discourage peasants from using his services, especially if the amount of money exchanged was low. But this explanation is not entirely satisfactory. George Charpiat borrowed 24 livres from Marie Catherine Chevey. We do not know the purpose of this loan, but the two parties preferred to seal their deal privately without going to the notary. In this case, a fee to seal trust seemed to be overrated. In another case, Jean Pierre Grimont and his wife Agathe extended a loan of 600 livres tournois, a much larger amount, to their neighbour Nicolas Frelin and requested the payment of interest. Their ‘promesse sous seing privé’ was not recorded at the notary either, despite the large amount of money.Footnote 19

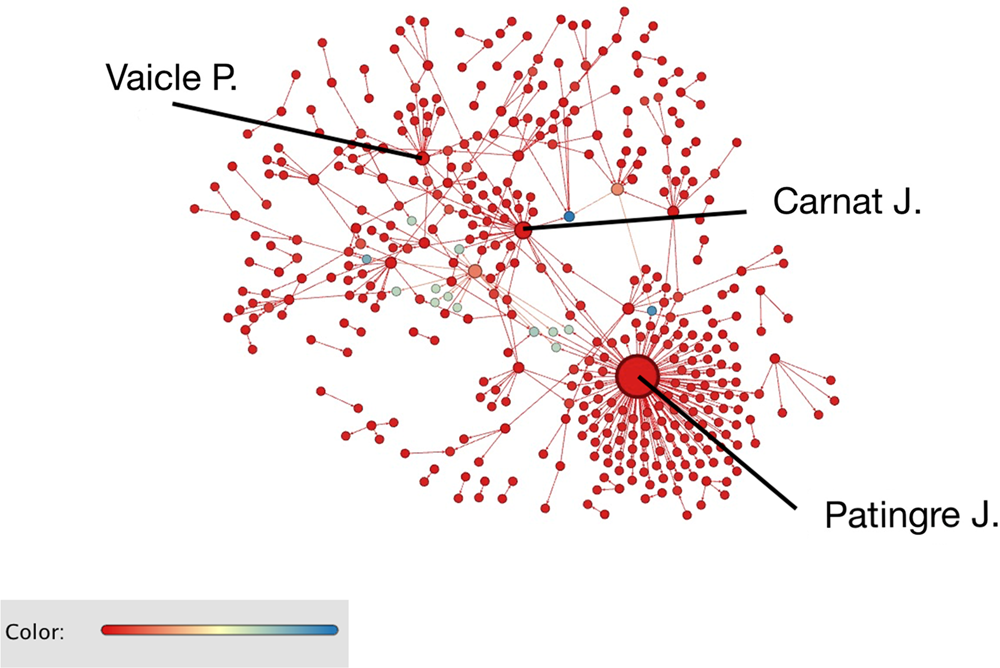

The non-notarised credit market in the seigneurie of Florimont presents the characteristics of a hermetic market where capital and trust circulated almost exclusively within the boundaries of the seigneurie and even within the same village and within the same socio-professional group. Out of the 1,070 transactions recorded, 62.7 per cent took place between inhabitants of the same village. However, only 11.3 per cent of the transactions were between members of the same family. Andreas Maisch found similar figures in eighteenth-century Württemberg: between 13 and 16 per cent of inventoried borrowing took place among kin. Wildberg in the second half of the seventeenth century featured a similar proportion (Ogilvie Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012 et al., p. 149). As a result, a strong centre–periphery is clear. Figure 4 shows clearly the geographical pattern of this market.

Figure 4. Informal credit market by nodes' place of residency, seigneurie de Florimont, 1770–90

The reconstruction of the non-notarised credit market reveals a dense network where people exchanged not only with one another but were also connected to several individuals at a time. Such a network shape made information readily available to a great number of people within the community, increasing the circulation of information and facilitating the matching process. There are only a few small communities (total number of communities equals 18 in the graph), meaning that most of the exchange took place in a hermetic sphere where agents most likely knew each other and had a sound knowledge of the other party. It is important to underline that most nodes in the network are connected to only one other node (69.18 per cent). This means that the level of reciprocity remained quite low. In fact, only 16 transactions out of 1,070 (1.5 per cent) were reciprocal. This can be explained by the type of sources used here. Probate inventories constitute only a mere snapshot of credit transactions at time t.

In terms of socio-professional categories, the probate inventories sporadically mention the occupation of lenders and borrowers. When the scribe did not record a specific occupation, however, I assume the person concerned was a farmer. Among the decedents, 86.5 per cent were peasants. They extended credit and borrowed mostly from their farmer neighbours. Rural artisans and innkeepers appear in the dataset recalling their dues, mostly purchases made on tab. When the innkeeper of Puis died in 1773, his probate inventories contained 38 claims for a total of 1,665.5 livres, with a mean of 43.8 livres tournois. Half of these were under only 20 livres tournois and have been found in his account book. The innkeeper also lent cash to his clients through several obligations and private notes, in a redistributive fashion. It is worth noting that he also incurred debt for a total of 2,103.45 livres (mean: 67.8 livres tournois). Logically, his influence in the network was very high (eigenvector centrality = 0.66).

Unsurprisingly, most exchanges (60.66 per cent by volume) featured peasant-to-peasant exchange, highlighting a strong pattern of homophily. Evidently, the category ‘peasant’ is far from being uniform. Several better-off peasants tended to appear recurrently in the transactions although they did not completely dominate the network. They were the biggest landowners and some of the wealthiest in the community. One of them was Jacques Patingre from Puis. He appears as a lender to 24 borrowers for a grand total of 2,952 livres and 8 deniers (median = 87.9). His claims are varied and represent well the activities of a better-off peasant. Some of his claims were simply deferred payments for supplies he had sold but some others were actual loans (see Table 5). He seems to have agreed on both non-notarised and notarial loans.

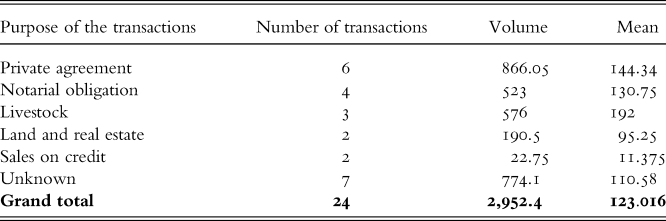

Table 5. Activities of Jacques Patingre recorded in the probate inventories, 1770–90 (probates dataset)

Interestingly, seigneurial agents and administrators (clerks, notaries, judges, etc.), appear in the dataset. They usually had a larger saving capacity than the rest of the rural population but preferred to lend money through the institutionalised channel of the notary. They did not play an important role in the seigneurie of Florimont.

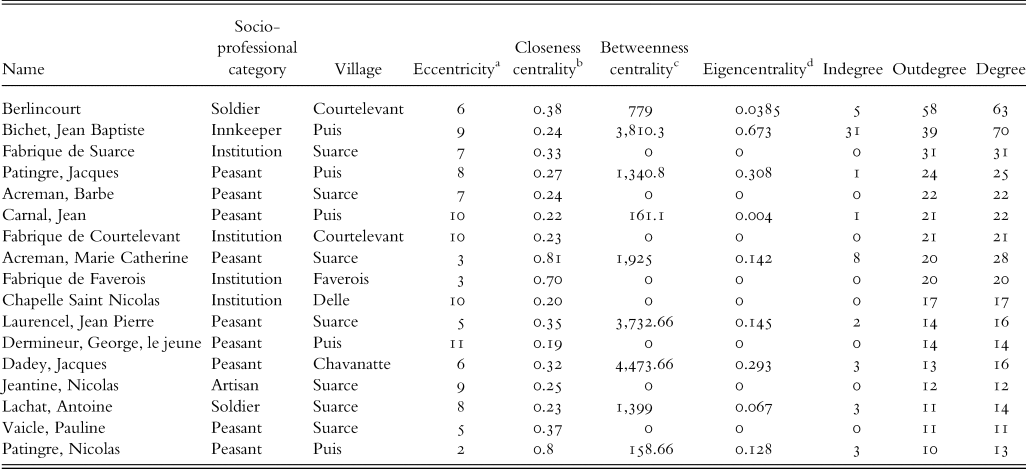

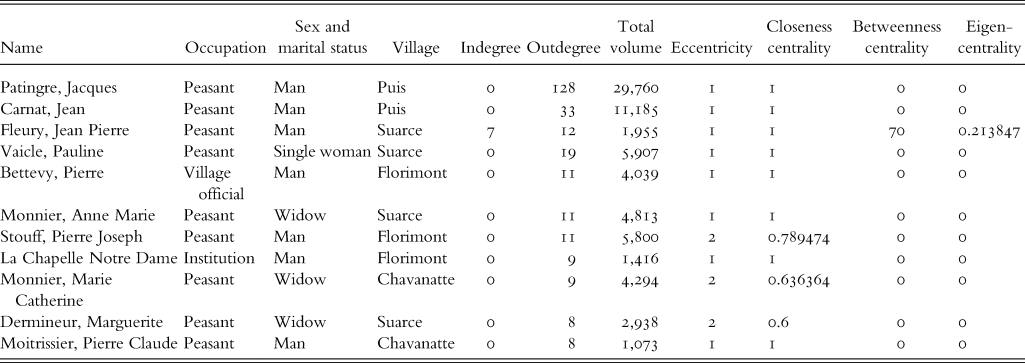

Non-personalised lenders (institutions), such as parish vestries, did play an important role in the allocation of credit (around 8.4 per cent of the total volume, 19 per cent in Wildberg and about 23 per cent in Reutlingen (Ogilvie et al. Reference Ogilvie, Küpker and Maegraith2012, p. 147; Stark Reference Stark, Gestrich and Stark2015, p. 105)). We know very little regarding the financial activities of these organisations, especially the parish vestries (Tabbagh Reference Tabbagh1991, p. 126). More importantly perhaps, out of 116 decedents, 57 were indebted to a parish vestry. These institutions extended loans in the form of annuity contracts and rarely registered the deeds at the notary.Footnote 20 The role of parish vestries could be compared to that of early banks, assuming a redistributive role of capital within the community. But their capital allocation remained deeply unfair and unequal, as preferences in terms of attribution and interest rates appeared nepotic. Their closeness centrality score indicates that they were at the core of the exchanges in this market (see Table 6).Footnote 21

Table 6. Positions in the informal credit network of the most prominent lenders according to social network analysis measures, 1770–90 (probates dataset)

a Eccentricity: the distance from a given starting node to the farthest node from it in the network (expressed in the number of nodes).

b Closeness centrality: the average distance from a given starting node to all other nodes in the network. Thus the more central a node is, the closer it is to all other nodes.

c Betweenness centrality: measures how often a node appears on shortest paths between nodes in the network.

d Eigenvector centrality (also called eigencentrality) measures the influence of a node in a network (up to 1). It assigns relative scores to all nodes in the network based on the concept that connections to high-scoring nodes contribute more to the score of the node in question than equal connections to low-scoring nodes.

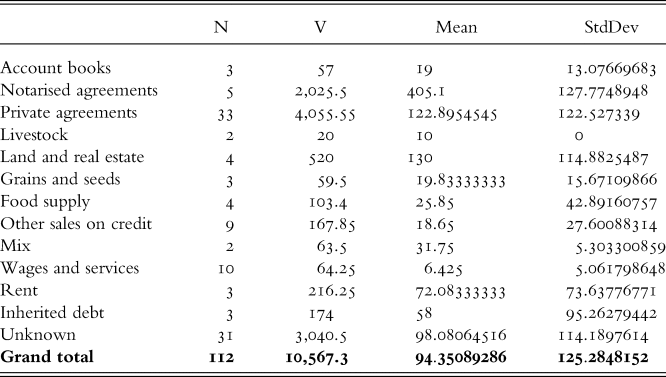

Women, that is unmarried women and widows, allocated a total of 10,567.3 livres tournois or 9.85 per cent of the total exchanged (see Table 7). Women represented 10.46 per cent of the lenders in the non-notarised credit market. This proportion is lower than what has been observed in the notarial credit market, as we shall see in the final section (Dermineur Reference Dermineur2014, Reference Dermineur2018b). Several widows and unmarried women were active lenders although they were not the biggest lenders in the network. The low number of female lenders can be explained by the fact that probate inventories often stated the name of the household's head as lender or borrower. De facto, this excluded married women. But scholars have long shown the importance of women in small daily transactions related to consumption and survival strategies.

Table 7. Widows and unmarried female creditors and credit allocation in the informal credit market, Florimont 1770–90 (probates dataset)

Most of these female creditors lent money through non-notarised loans (29.4 per cent by number, 38.4 per cent by volume for female credit transactions). Barbe Acreman, a widow living in the village of Suarce, died in 1775. Her portfolio counted 22 debtors for an amount of 3,320 livres tournois.Footnote 22 She owned a few pieces of arable land. But it seems that most of her revenue came from her investment in the form of private loans contracted at various points in time. The oldest agreement was dated 1756 and a few were dated a few months before her death. Her debtors came from her own village but also from several other villages of the seigneurie and two villages outside the seigneurie. Out of the 22 loans she made, only one is labelled as a notarial obligation; the rest are non-notarised agreements. It seems she had extended loans together with her husband and then on her own after his death.

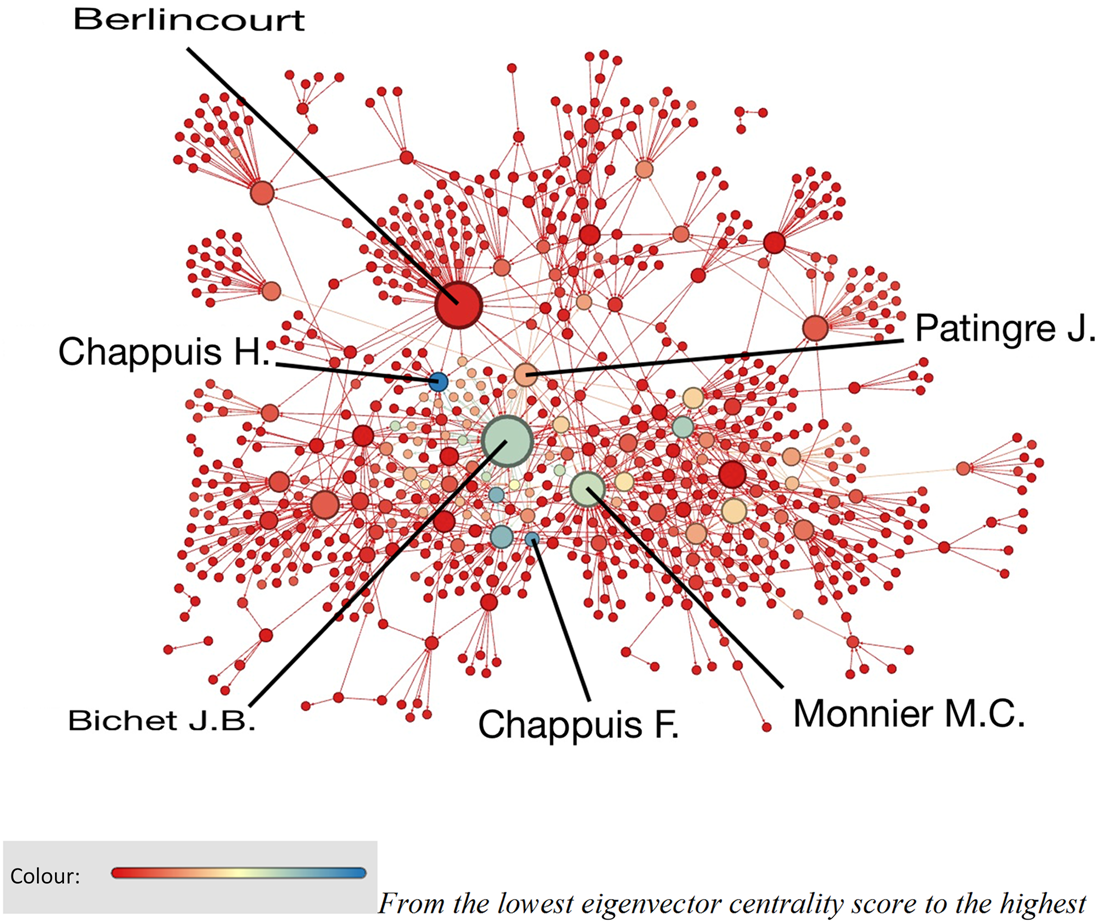

The biggest lenders in the non-notarised network were not necessarily the most influential or the best-connected actors (see Table 6 and Figure 5). Social network analysis measures provide an interesting perspective on these aspects. Figure 5 highlights the eigenvector centrality of several lenders. Jacques Patingre, in an earlier example, was connected to several important nodes, which in turn had influence in the network, making him both informed and influential as well. Eigenvector centrality tells only one part of the story and works well only when all the agents are from the same seigneurie. The retired officer Berlincourt was by far the biggest creditor but was not influential in the network in terms of eigenvector centrality, mostly because his debtors lived outside the seigneurie limits and were not connected to other nodes in the network. This does not mean he was not influential at all within his community, but he does not seem to have extended many loans to his fellow villagers. We ignore why his portfolio featured only external debtors. Jean Baptiste Bichet, the innkeeper, on the other hand, dealt mostly with inhabitants of his village and his seigneurie. As a result, and because of his redistributive socio-professional occupation, he is the one who scored the highest in terms of influence.

Figure 5. Informal transactions in the seigneurie of Florimont

Social network analysis reveals that the non-notarised transactions network was a dense one with a few big lenders who were not necessarily the most influential in the network. In such a network with high homophily, one can hypothesise that social norms were to be enforced and sanctions could even be coordinated between agents (preventing further transactions for instance). Such a dense network could help enforce prescribed behaviour. It is what Coleman labels as ‘closure’ (Coleman Reference Coleman1988, pp. 105–7). More work on this topic using social network analysis should highlight interesting new features regarding early financial networks.

This section leaves us with important questions to answer. First, one needs to clarify the strategies and choice of actors in the credit markets. Why did the actors choose one circuit of exchange over another? Why did they decide to seal their deal privately rather than to go to the notary? What do the choices of lenders and borrowers reveal about the mechanisms of credit? Was it a matter of trust between the parties to exonerate themselves from the notary's seal? Was it because their agreements could include other terms, such as a hidden, higher interest rate? We will come back to these important questions in the next section.

III

In early modern France, the notary was an official authorised to perform certain legal formalities, in particular concerning wills, donations, marriage contracts, sales and various other contracts regulating and managing property and estates. Drawing up loan contracts constituted only a part of his activity. There was only one notary for the seigneurie of Florimont. Therefore, our dataset of notarial loan contracts is fairly comprehensive. The notary followed a set of legal rules enacted by the authorities. Interest rates, guarantees and the format of contracts were standardised to fit these regulations. Hoffman and his co-authors have shown that Parisian notaries often acted as brokers to match potential borrowers and lenders together (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2001, Reference Hoffman, Postel-Vinay and Rosenthal2019). In rural communities where endogamy, homophily and social proximity were high, this role as broker appeared less significant.

Historians have also used notarial registers to present a picture of the notarial market as the main capital market, neglecting the use of other private transactions. How does this formal credit market compare with the non-notarised credit market? What were the major differences between these two circuits?

For the period 1770–90, the notary of Florimont witnessed 436 ‘obligation’ contracts worth a total of 236,629 livres tournois. There were only a handful of annuities signed for the period. But one needs to remain careful with the terminology employed by the inhabitants of Florimont. They tended to label all sorts of credit transactions as ‘obligations’. Most of these loans specified a 5 per cent interest and securities to back the transactions.Footnote 23 They all had a time limit, usually a few years, most often between one and three. Some of them were to be repaid ‘on request’. The median per obligation contract amounted to 246 livres tournois, eight times the median transactions in the non-notarised credit market (see Table 8).

Table 8. Comparison between the notarial credit market and the informal credit market (probates and notarial dataset)

The total volume of exchange in the notarial credit market is twice the volume of non-notarised transactions. But we need to remain cautious with these figures. The probate inventories contained in the non-notarised market dataset are not comprehensive. Indeed, as stated earlier, the dataset comprises only 7 villages out of 12; probates are therefore missing from the archives for five villages. We cannot hypothesise too much, but if we project the missing probate data, we could reach a similar volume for the non-notarised market and the notarial market. It is worth noting that 41 individuals appear in both datasets (notarial and non-notarised), but there was no match to be found between the two datasets. In other words, no agreement appears in both the notarial market and the non-notarised market. Even the obligations found in probates do not match with the notarial records. It is probably because the obligations featured in probates were issued before 1770.

The notarial credit market contained more substantial loans than the non-notarised market. However, the purpose of the loan is unknown in 45 per cent of the cases (see Table 9). Most borrowers reported an investment in land and real estate (13.53 per cent of the total volume), and in livestock (10.2 per cent of the total volume), a productive investment similar to what is found in the non-notarised market. The repayment of a debt (inherited or overdue), a category absent in the non-notarised market, accounted here for 20.8 per cent of the total value. One can assume that in a case of inherited debt, lenders were willing to secure the loyalty of the debtor's heirs through an official contract. Unlike in the non-notarised market, consumption-related debt remained marginal in the notarial credit market.

Table 9. Purpose of loans in the notarial credit market in the seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90 (probates and notarial dataset)

Only a handful of lenders appear with high volumes of loans. As with the non-notarised credit market, no lender really occupied an overly dominant position in the notarial market. In other words, there was no village lender king.

Regarding the socio-professional categories represented in the notarial credit market, results show a pattern similar to that of the non-notarised market. Most of the creditors and debtors were peasants (82.6 and 73.6 per cent respectively). Artisans accounted for 5 per cent and the nobility for 4.6 per cent of the debtors. Interestingly, the proportion of institutions as lenders remained low (3.9 per cent). Parish vestries drafted their own annuity contract without the intercession of the notary.

In terms of geographical location, 153 out of 436 transactions took place between people living in the same village (35 per cent). This proportion is almost half that of the non-notarised market. One can add that only 20 out of 436 were loans between members of the same family (4.5 per cent). Therefore, lenders and borrowers had a greater incentive to register their loans as trust between the parties could be missing.

The non-notarised credit network appeared to be more connected with less isolated communities than the notarial network was (see Tables 10 and 11). Isolated peer-to-peer transactions were more numerous in the notarial credit networks (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Notarial credit network in the seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90

Table 10. Non-notarised network and notarial network measures (probates and notarial dataset)

Table 11. Comparative data between the notarial credit market and the informal credit market (probates and notarial dataset)

It is interesting to note that women were more inclined to lend money through the official channel, perhaps to secure their assets more effectively (see Dermineur Reference Dermineur2018b). Widows and unmarried women were also more numerous as debtors. Here, sex could have been a variable for trust allocation.

Except for one large creditor, the notarial credit network did not feature dominant big players. The average number of loans extended per individual lender was smaller than in the non-notarised network. The notarial network had many more single communities (50 versus 18 for the non-notarised network), i.e. one-to-one exchange (see Table 10).

Among the top creditors in the non-notarised market, several were also the most important lenders in the formal market (see Table 12 and Figure 7). Let's consider the examples of Jacques Patingre, Jean Carnat and Pauline Vaicle, who were dynamic lenders in both markets. It is difficult to interpret their individual strategies without a degree of hypothesising. In the case of Pauline Vaicle, she inherited from her father, a wealthy farmer, before she reached the age of 25. She seems to have been his sole heir. Through her guardian first and then on her own, she invested her capital through financial transactions. She agreed to lend 320 livres to her neighbour Jean Pierre Jobin in 1756 via a notarial loan, with the mediation of her guardian. Exactly 20 years later, she lent 200 livres with 10 livres of interest to the same borrower, again through a ‘contrat sous seing privé’.Footnote 24 We can hypothesise that her guardian fructified her assets through a secure channel, perhaps with the enlightened guidance of the notary. After she came of age at 25, she may have managed some of her assets on her own and decided to extend money through private agreements for some loans, without the intercession of the notary. But her name appeared in the notary's records until she married in 1783. Some of her assets may have remained tied to her guardian's network and/or were in the notary's hands to generate a profit.

Figure 7. Eigenvector centrality in the notarial credit market, 1770–90

Table 12. Creditors in the notarial credit market in the seigneurie of Florimont, 1770–90 (based on the notarial dataset)

In the case of Jacques Patingre (128 loans, amounting to 29,760 livres), most of his notarial loans seem to have been made at the same time, perhaps in an effort to regularise his private portfolio into a more secure one. He seems to have done so a few years before his death, perhaps to regularise verbal debts and the least secure of his debts. Most of his debtors were from another neighbouring village. In fact, most of his loans were deferred payments for the sale of livestock (see also Table 4).

Finally, Jean Carnat (or Carnal), extended 33 loans in the notarial credit market amounting to 11,855 livres tournois (median: 300). All except one of his notarial loans (96 livres) were higher than 100 livres. His activities in the non-notarised market amounted to 4,417.4 livres tournois for 22 transactions (median: 96). Thirteen transactions were under 100 livres. He seems to have preferred resorting to the notary in the case of large transactions and reserved private agreements for smaller transactions. One would expect all creditors to follow his rational strategy in order to secure investments. But he seems to have been the only one to behave in this way. This can perhaps be explained by the fact that he was an outsider in the community. Upon his death, the priest wrote in the parish register that he had spent many years abroad, first as a servant and then agent of the Duke of Courland, son of the king of Poland, Charles III.Footnote 25 The fact that he considered himself an outsider in want of relevant information could have been an incentive to register the highest loans at the notary in an effort to secure them.

Indeed, Joseph Berlincourt, who was a retired military officer, only extended money through the non-notarised channel (58 transactions). He too may have been lacking information since it is likely that he had been away for a while. But Berlincourt might have considered that his status gave him enough authority to disregard official channels. His status might have been sufficient to sustain trust and enforce repayment. His lending capacity seems to have been high, which in turn made him a critical actor in the credit market. If a debtor defaulted on him, he might have denied further loans in the future.

Most non-notarised agreements tended to be smaller (not necessarily shorter) than notarial ones. This can explain the preference for private over notarised agreements, as the latter were sealed against a fee. For non-notarised loans of over 100 livres tournois, one can assume that trust was strong enough and information readily available to spare the parties any additional cost. As Figure 4 shows, most of the non-notarised transactions took place between dwellers of the same village. Many authors have highlighted that a society which shared norms created expectations of trustworthiness, and therefore reduced the transaction cost related to an infringement of norms (Coleman Reference Coleman1988; Yamagishi Reference Yamagishi2011).

Notarial contracts, on the other hand, seemed to palliate a deficit of trust. Most of the contracts stipulated a pledge and/or a guarantor. I assume that most of the agents had information available about each other as sociability and homogamy increased social proximity. The notary, therefore, did not act as a broker between strangers in Florimont. His function, rather, was to cement trust between the parties. Pledging a piece of land could reassure the creditor, especially because the land mortgaged could also be used to pay interest in kind. Increasingly, obligation contracts secured the transaction with a guarantor as well. In case of default, the creditor would be able to turn to this guarantor to enforce repayment.

IV

Peer-to-peer lending in pre-industrial France was not limited to solely notarial credit circuits. Traditional historiography has emphasised the critical role of notaries in credit intermediation as facilitators and brokers. While their role was incontestably important, it has certainly been overrated. Alongside the notarial credit channel, one finds a dynamic, personal and informal credit market.

This non-notarised credit market functioned in a hermetic circle where inhabitants of the same village, belonging to the same professional category, exchanged both money in cash and goods in the form of deferred payments. The debts they incurred helped to smooth consumption and palliate the lack of cash within the community, but they also helped to make investments. Some lenders were more prominent than others, although no one really dominated the non-notarised market. In comparison, the debts incurred in the notarial credit market were more substantial but did not serve a different purpose. Here too, the biggest lenders did not monopolise the extension of capital. Individuals and households chose either the notarial lending circuit or the non-notarised one for a wide range of reasons. Scholars have stressed the role of notaries in alleviating asymmetric information in early financial markets. For them, notaries created trust. But in small rural communities with strong bonds, individuals could easily overcome this asymmetry of information, which in turn explains the vitality of the non-notarised lending channel.

Perhaps the most striking finding of this study lies in the fact that the total volume of exchange between the non-notarised credit market and the notarial credit market (after projection) tended to be similar. We lack data on the non-notarised credit market, but if the results from the seigneurie of Florimont can be reproduced elsewhere, we may have to reconsider the size of capital markets in early modern France.