This is what the title of a law dissertation written at a German university looked like in 1602:

Tres decades controversarum iuris quaestionum ex materia de servitutibus tam urbanorum quam rusticorum praediorum selectarum Footnote 1

(Thirty controversial law questions selected from the matter of servitudes, both in urban and rural estates)

And here is a dissertation title from less than one century later, in 1687:

De iure circa somnum & somnia, Von Recht Des Schlaffs und der Träume Footnote 2

(Of the law concerning sleep and dreams, Of the law of sleep and dreams)

The difference could hardly be more pronounced, both thematically and methodologically. In the course of the seventeenth century, German jurists increasingly set aside established subjects like servitudes, a classic institution of civil law, and engaged with themes that were more thematically focused, diverse, and sometimes highly imaginative, ranging from the law of calculation errorsFootnote 3 to the law of shadows.Footnote 4 Increasingly abandoning the scholastic question–answer format and sometimes even embracing the German vernacular in their titles, jurists created a collection of single-voiced, monographic dissertations that is so diverse, wide-ranging, and frequently original that it should command the attention of historians of all stripes. This article adopts a distant reading approach to retrace long-term methodological and thematic shifts and continuities in over twenty thousand dissertations written at German universities in the seventeenth century. Methodologically, it highlights the interest of argument-driven digital history and aims to encourage scholars to engage with a type of data that is available in many other contexts. Providing a pathway into a forbidding archive, this study highlights the vast diversity of insights – into the history of jurisprudence and its receptiveness to social change, academic education and publishing, baroque rhetoric, and the broader cultural, political, and economic history of the German lands – that can be gleaned from one of the richest and most neglected sources in European legal history.

The first section discusses the dissertation as a genre, its ambivalent historiography, and the method and data underpinning this article. Similar to literary scholars who embraced computational text mining under the banner of ‘distant reading’, historians could benefit from integrating more digital evidence of this kind in their work. Following a concise spatial and temporal outline of the dissertations and their unequal distribution among universities and professors, the third section retraces one of the most striking thematic shifts in this archive: a drastic decline in civil law dissertations. While the waning interest in fields from property to inheritance law raises important questions, topics like marriage and debt eluded this pattern. Just like recurrent spikes in dissertations on imperial politics or inflation and monetary debasement, they underline the academic jurists’ responsiveness to social, political, and economic change. The third section of the article discusses how a growing share of the dissertations lost the dialogic attributes characteristic of the oral disputation and took on a monologic and monographic form. The decline of dialogic and antagonistic forms of reasoning – encapsulated in the scholastic quaestio and controversia – reflected broader changes in seventeenth-century academic culture, but they also transformed the dissertations as a genre. The fading of dialogue and controversy went hand in hand with a preference for more sharply delineated, diverse, and often original subjects that are the theme of the last part of the article. The way in which late seventeenth-century jurists expanded the scope of their writing reflects broader conjunctures of baroque curiosity and polymathy, but it also illustrates the juridification of public affairs in the Holy Roman Empire and the heightened stature of an epistemic community that felt increasingly entitled to interpret all spheres of life through its own categories.

I

Disputations were one of the most common teaching formats in European universities from the high middle ages to the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 5 Students and teachers regularly held disputations to practise defending arguments, to prove their mastery of a subject, or to obtain academic degrees. The makeup of these exercises varied, but they usually involved a respondent (respondens or defendens) who, under the direction of a professor or lecturer (praeses), had to defend publicly a number of theses against objections brought forward by an opponent. All participants were bound by strict rules of argumentation and behaviour. Disputations were popular among jurists, also because they were thought to prepare students for the forensic practice.Footnote 6 Disputations had traditionally been held orally. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century high schools and universities, the spoken word was the ‘key principle of instruction’,Footnote 7 to the point that even written texts needed to be performable orally.Footnote 8 However, from the end of the sixteenth century, disputations were increasingly accompanied by printed Latin texts.Footnote 9 Initially, these printed dissertations were summaries of the key theses that were sometimes sent out as invitations. In the course of the seventeenth century, the printed dissertations grew longer.

The tens of thousands of dissertations written at German universities have long had a difficult standing among historians. As early as the eighteenth century, a collector complained that scholars used the dissertations ‘to light tobacco’Footnote 10 or as ‘baking parchment’. The older historiography is full of scathing judgements, perhaps best encapsulated in Ewald Horn's conclusion that the dissertations are ‘as worthless today as in the past’.Footnote 11 In German libraries, the masses of dissertations have long counted among the most poorly catalogued and ‘often positively disdained’Footnote 12 holdings.Footnote 13 Scholars frequently dismissed the dissertations as ‘worthless’.Footnote 14 Historians of science long had little use for what seemed like a ‘medieval relic’.Footnote 15 Among philologists, the texts had a problematic standing, as well: because disputations fall in the grey zone between logic and rhetoric, they were neglected by scholars of both.Footnote 16 The variety of dissertation formats, purposes, and subjects further complicates the work with these sources and may well put ‘any comprehensive and all-embracing understanding of them beyond our reach’.Footnote 17 In addition, the texts make for anything but light reading: written, as they are, in awkward Latin, requiring a high degree of subject expertise, cluttered with abbreviations, full of imprecise quotes, and set in varying font types and sizes.Footnote 18

Nevertheless, in recent decades, several scholars have rediscovered these abundant yet elusive sources. Dissertations are seen as much more representative of the average educated person than canonical texts. The subject choices reflect questions ‘that contemporaries perceived as important’.Footnote 19 Indeed, dissertations were the key medium through which seventeenth-century jurists communicated their scholarship before that function was taken over by journals and periodic literature in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 20 Dissertations allowed jurists to engage with new subjects and test arguments.Footnote 21 They laid out controversies in clear terms and offer a scholarly ‘mood barometer’.Footnote 22 Historians like Hanspeter Marti count dissertations among ‘the most important sources about early modern universities’,Footnote 23 with immeasurable value for conceptual history, the history of mentalities, the history of individual disciplines, and a wide variety of social and cultural historical questions.Footnote 24 The dissertations also offer a means of engaging with the intellectual history of smaller regions that lacked eminent scholarly figures.Footnote 25

The default way of engaging with these sources had long been to select individual works of authors deemed important or influential.Footnote 26 Historians aimed to assess the ‘quality’ of individual texts and their authors. This focus on individual works has led scholars to perceive the question of authorship as particularly important.Footnote 27 The problem proved to be productive, if rarely easy to solve. Determining whether a dissertation was authored by the praeses or the respondens can be a complicated and sometimes unsolvable puzzle.Footnote 28 The title page and other paratexts can give important clues, but it is not always possible to ascribe authorship to either the praeses or the respondens. In some cases, the author was a third person.Footnote 29 In the case of seventeenth-century legal dissertations, it is fair to assume that the praeses had at least a strong influence on the content of most dissertations.Footnote 30 Indeed, for many praesides, disputations offered a cheap way to publish their work if they could find a respondent willing to pay the printing costs.Footnote 31

In recent decades, historians have increasingly called for broader studies of the dissertations as a whole.Footnote 32 The main obstacle to engaging with the entire corpus has always been the dissertations’ sheer number: the Max Planck Institute for Legal History alone, which acquired the largest collection, catalogued more than 73,000 legal dissertations.Footnote 33 To date, the most extensive thematic study conducted with this data is Karl Härter's long-term analysis of public law dissertations between 1560 and 1803.Footnote 34 A number of monographs, catalogues, and shorter contributions focused on smaller thematic subsets, particular universities, or the holdings of individual libraries.Footnote 35 Other scholars have recognized the potential to reconstruct ‘how new ideas emerged [and how they] were discussed and established themselves as dominant’,Footnote 36 including ‘new scholarly paradigms’,Footnote 37 but never ventured systematically to retrace the shifting trends in the dissertations. Leading scholars thus still lament the lack of a broad spatial and temporal ‘birds-eye view’Footnote 38 of this archive.

While the inspiration for early large-scale projects came from French literary sociology, in recent decades computational text mining has been invigorated under the banner of ‘distant reading’.Footnote 39 In its early days, this kind of work has often been framed as ‘a struggle that pits critical tradition against a new technological initiative called “digital humanities”’.Footnote 40 Franco Moretti proposed distant reading as a way of exploring the ‘slaughterhouse of literature’ neglected by close reading. In more recent years, the field has matured. Leading scholars now reject the antagonistic frames of reference cherished by its pioneers. Ted Underwood questions the simplistic narratives that reduce distant reading to ‘conflict between machines and culture.’Footnote 41 Advances in the field ‘have less to do with computers than with new ideas about modelling and interpretation’,Footnote 42 such as a broader shift from a culture of statistic data modelling to algorithmic modelling. Perhaps most importantly, close and distant reading are not understood as mutually exclusive anymore: under new labels like ‘scalar reading’,Footnote 43 scholars mine individual texts or use evidence from distant reading to focus on minute details.Footnote 44

One reason for the slow uptake of distant reading among historians could be that many in the current generation of historians – trained under the auspices of cultural and micro-history – tend to distrust aggregate data and any method that mediates direct interaction with the sources. We are used to framing quantitative and qualitative methods as mutually exclusive, and, perhaps even more nefariously, in terms of subjectivity and (supposed) objectivity. This has much to do with the problematic heritage of quantitative history and ‘cliometrics’. With its often positivistic and scientistic approach to the past, cliometrics is often seen as a cautionary tale for ‘argumentative overreach based on numerical evidence’.Footnote 45 Literary historians have found more productive ways of integrating digital evidence into their work and reject the notion that quantitative methods are more objective: ‘numbers have no special power to settle questions: assumptions and inferences still have to be hammered out through a familiar process of debate’.Footnote 46

The data at the basis of the article comprises all 20,549 entries tagged as legal dissertations in VD17, a bibliography of prints from German-speaking Europe in the seventeenth century.Footnote 47 VD17 offers one of the most extensive bibliographies of early modern legal dissertations.Footnote 48 However, it is far from complete, as many dissertations remain uncatalogued.Footnote 49 Moreover, dissertations on natural law and the law of nations were often defended in faculties of philosophy and have thus not been classed as legal dissertations.Footnote 50 A key difficulty in working with this data is the high number of duplicates (3,716) and reprints (653) that had to be marked and filtered, partly automatically but also laboriously by hand. Where not marked otherwise, duplicates and reprints have been excluded from the charts that follow, leaving 16,180 singular dissertations. The temporal focus is on the seventeenth century because this period saw the creation of new universities across the Holy Roman Empire, an increasing interest in legal studies, especially at Protestant universities, and – as discussed below – major thematic and methodological shifts.

The focus of this article is on relative word frequencies, a more straightforward approach than word embeddings or topic models – language modelling approaches that allow scholars to retrace recurrent word patterns and semantic change – but one better suited to make sense of the dissertations’ short titles. Instead of assigning each dissertation a category, word stems were identified in the unstructured title texts. The fact that especially earlier dissertations could be situated in several legal domains at once makes it difficult to sort the texts into distinct categories.Footnote 51 The most valuable dimension of this data are the dissertation titles. Titles do not just indicate the subject of a dissertation: they also show how those subjects were framed, how they were approached methodologically, what language was deemed suitable to describe them, and how the printed dissertation had come into being. While this makes titles and metadata one of ‘the lowest hanging fruit of literary history’,Footnote 52 the relationship between a dissertation's subject and its title is anything but straightforward. Titles could be highly generic, narrower than the actual subject matter, or otherwise misleading. Titles are always ‘half sign, half ad’Footnote 53 and this is also true for the title pages of early modern dissertations, which were sometimes used as literal placards to publicize a disputation among the members of a university.Footnote 54

Moreover, like many pre-modern titles, the titles at the centre of this study are artificial in the sense that they have been somewhat ‘arbitrarily separated out from the graphic and possibly iconographic mass of a “title page”’.Footnote 55 As one can see in Figure 1, the title pages of early modern dissertations included extensive references to the participants of a disputation, to the university where it was held, and to the powers that be, including the divine. In the dataset obtained from VD17, this dissertation on the law of wounds is just listed as Disputatio iuridica inauguralis, de vulneribus. At the same time, in a situation where only a part of the dissertations has been digitized, and where they are not generally available in machine-readable format, the titles are our best window into this daunting archive.

Figure 1. Dissertation title pages included extensive ancillary references. Source: Heinrich Rudolph Redecker and Lorenz Arnold Meinhardt, Disputatio iuridica inauguralis, de vulneribus (Rostock, 1667).

Approaching early modern dissertations through distant reading makes sense because they are so numerous that they exceed any individual's capacity for close reading and synthesis. While this makes it possible to reveal arcs of change that remain hidden from us by their sheer scale, the information gleaned from charts and numbers needs to be read against individual dissertations and contextualized within broader scholarship on seventeenth-century jurisprudence, baroque rhetoric, and the history of the early modern university. Thus, the aim of this article is twofold: outlining a long-term ‘conjunctural history’Footnote 56 of the law dissertation and using it to understand and contextualize the idiosyncrasies that make these sources so extraordinary. With few exceptions, most of the shifts described cannot be attributed to individuals but are gradual developments that unfolded over decades or centuries.Footnote 57 Yet, these large-scale transformations offer a framework for understanding the emergence of new kinds of dissertations whose interest we can only appreciate in close reading. An in-depth exploration of these individual texts would go beyond the scope of a journal article, but readers may find new avenues for future studies, both in close and distant reading.Footnote 58

II

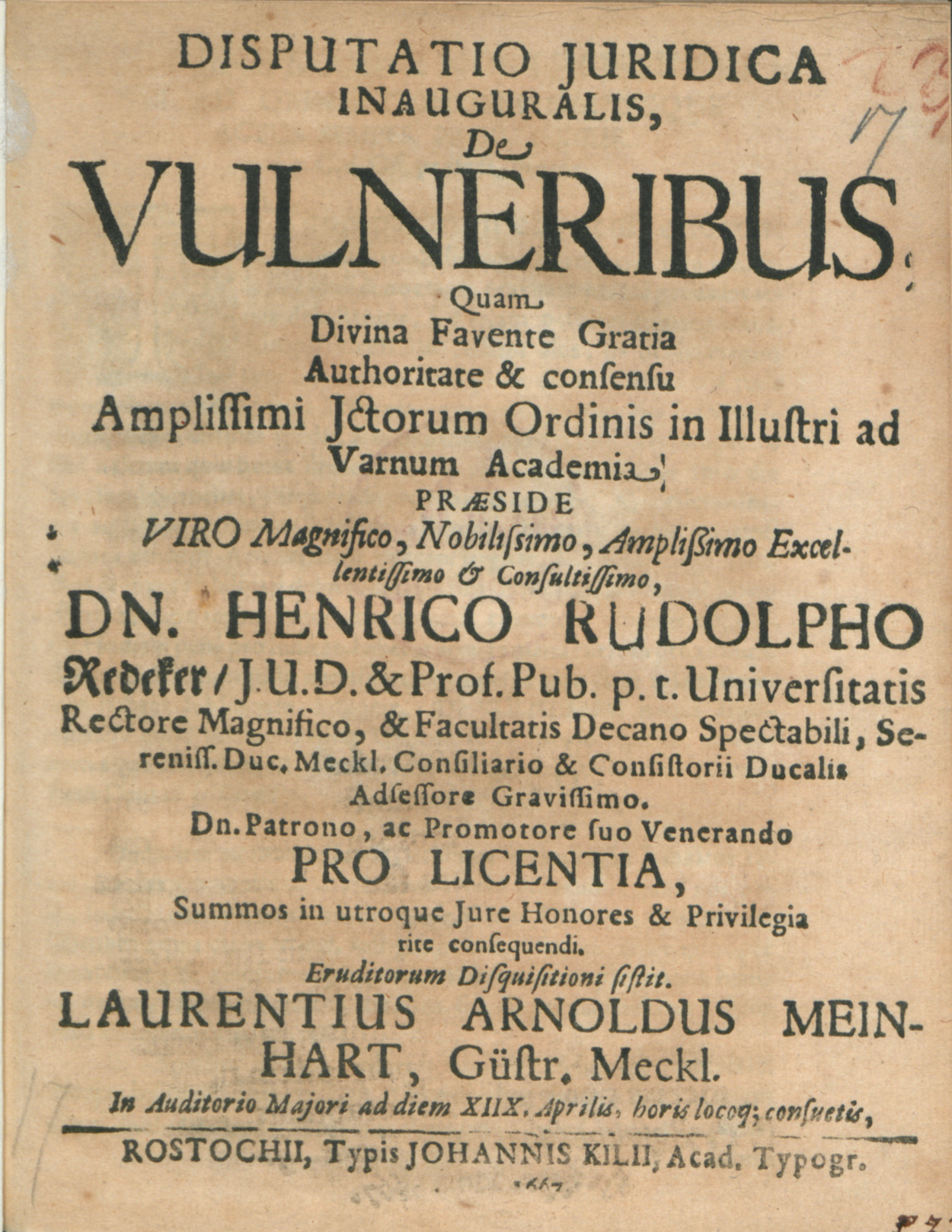

The subjects treated in legal dissertations were remarkably diverse; their geography was not. More than half of the legal dissertations of the seventeenth century were written at just a handful of Protestant universities: Jena, Wittenberg, Strasbourg, Altdorf, Leipzig, and Frankfurt on Oder (Figure 2). The large burst of dissertations in the 1660s was largely fuelled by Frankfurt/Oder and Jena, where scholars like Samuel Stryk and Ernst Friedrich Schröter attracted large numbers of students. Overall, however, the dissertations were distributed more equally in the second half of the century. German universities saw a longer trend of decentralization between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when many Imperial Estates founded their own universities (Landesuniversitäten), many of which placed particular emphasis on jurisprudence.Footnote 59 Particularly striking is the case of Halle, a key centre of German Pietism and Enlightenment thought, which jumped to prominence almost immediately after its founding. While Catholic universities had higher numbers of baccalaureate and doctoral graduates than the Protestant universities, they account for far fewer legal dissertations than the Protestant universities.Footnote 60 The reasons for this disparity are multiple and not always clear.Footnote 61 In contrast to their Protestant counterparts, Catholic dissertations often focused on elemental questions of Roman and feudal law that made them less attractive to booksellers, libraries, and collectors. However, one should not take the lack of dissertations as an indictment of the quality of Catholic legal scholarship.Footnote 62 The dataset also contains a small set of disputations held at academic high schools (akademische Gymnasien) that did not have the right to confer academic degrees.Footnote 63 Clearly visible is the impact of the Thirty Years’ War that led to a decline and sometimes even closure of universities, with overall enrolment going back by up to 50 per cent of pre-war levels.Footnote 64

Figure 2. More than half of the catalogued dissertations were published at only a handful of Protestant universities. Dissertations by university location (four-year moving average, excluding reprints, duplicates, unaffiliated dissertations, and universities with less than 100 dissertations). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

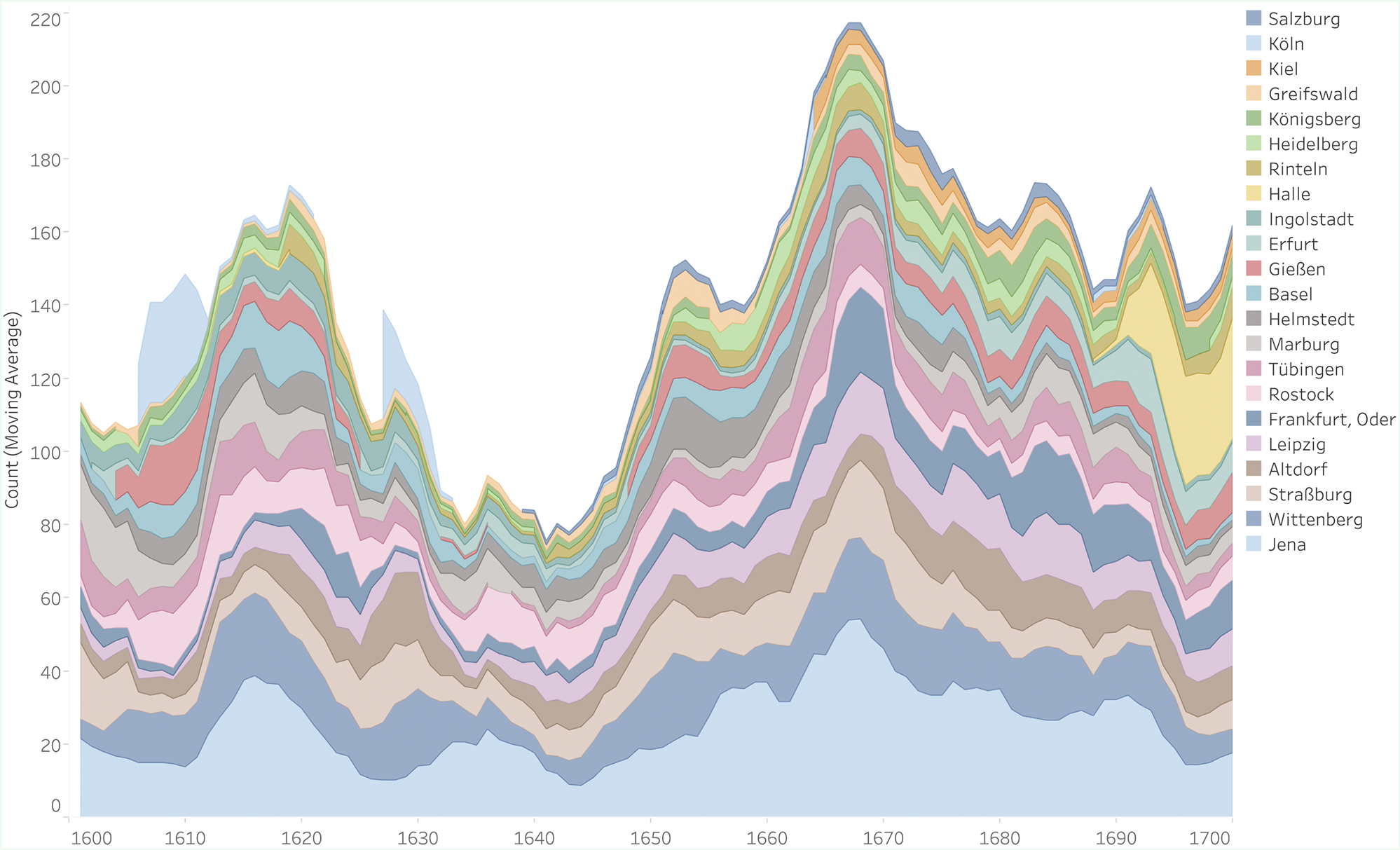

If not all universities contributed equally to the dissertations catalogued today, that burden was not distributed equally among faculty either (Figure 3). At Frankfurt/Oder, for example, five scholars alone were responsible for more than half of the dissertations written in the entire century. At Basel, in contrast, the dissertations were distributed much more equally.

Figure 3. The number of dissertations individual scholars supervised varied substantially. Dissertations by praeses at Frankfurt/Oder (left) and Basel (right) (excluding reprints and duplicates). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

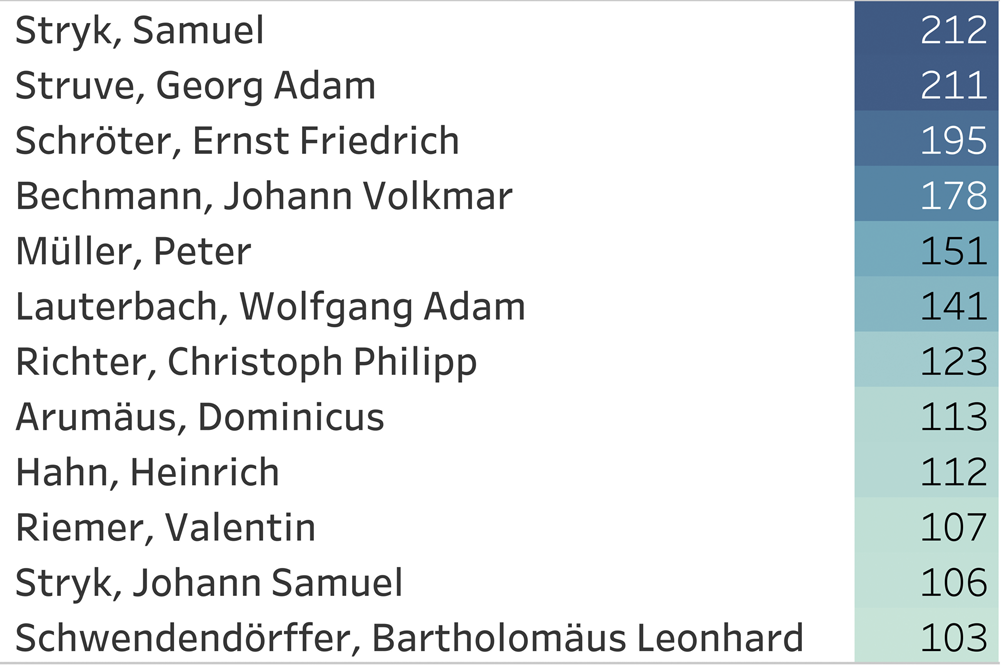

Indeed, it was not uncommon that a few professors (praesides) dominated the production of dissertations in certain fields or universities.Footnote 65 The names of the most prolific praesides of the century (Figure 4) include several of the most eminent jurists of their time, many of whom had excellent reputations as teachers.Footnote 66 Georg Adam Struve at Jena, for example, was known for speaking freely rather than reading out his lectures.Footnote 67 Samuel Stryk also had a reputation as a dedicated and pragmatic teacher. Others are less well known, such as Heinrich Hahn, who taught the Pandects and Institutes at Helmstedt and oversaw at least 140 dissertations, or his student Peter Müller, who taught at Jena.Footnote 68 This is a good example of how distant reading approaches can help us identify formerly eminent scholars who are not widely known today.Footnote 69

Figure 4. Several of the most prolific scholars of the century are not widely known today. Praesides with 100 or more dissertations (excluding reprints and duplicates). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

Figure 5. The work of a small number of scholars was reprinted disproportionately; a strong indication of scholarly prestige. Praesides by number of reprinted or re-edited dissertations (excluding duplicates and praesides with less than five reprints). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

When a dissertation was deemed particularly original or interesting, it could be re-edited or reprinted.Footnote 70 New and revised editions of dissertations show that there was a market for these texts, ‘independent of occasion or location’.Footnote 71 A new edition was an excellent ‘test for demand’Footnote 72 and could help establish schools of thought and further individual careers. Some dissertations were still deemed useful and reprinted decades or centuries after their first publication.Footnote 73 The practice of reprinting and re-editing dissertations became particularly common in the last third of the century. Among the most frequently reprinted dissertations, a considerable number are concerned with unusual and suggestive topics ranging from slaps in the face,Footnote 74 to love letters,Footnote 75 or the dunking of witches.Footnote 76 Dissertations on women, sexuality, or Jews were also popular. At the same time, one also finds less evocative dissertations on civil, public, and procedural law, which were likely reprinted because of their enduring academic and practical value. Most praesides never had a dissertation reprinted at all, but the work of a small number of scholars was reprinted disproportionately (Figure 5). If the number of re-edited and reprinted dissertations indicates scholarly prestige among contemporaries, the stature of Samuel Stryk can hardly be underestimated. Stryk, who taught at Frankfurt/Oder and Wittenberg, was the key figure of usus modernus pandectarum, the tradition of Roman Law reception that came to define German legal scholarship in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 77 The unparalleled number of reprinted dissertations also had to do with Stryk's reputation for treating ‘rare and uncommon matters’.Footnote 78 However, Stryk's ability to attract swaths of students stands in contrast to his colleagues in his primary field of expertise, civil law, for which the dissertations indicate a remarkable decline over the course of the century.

III

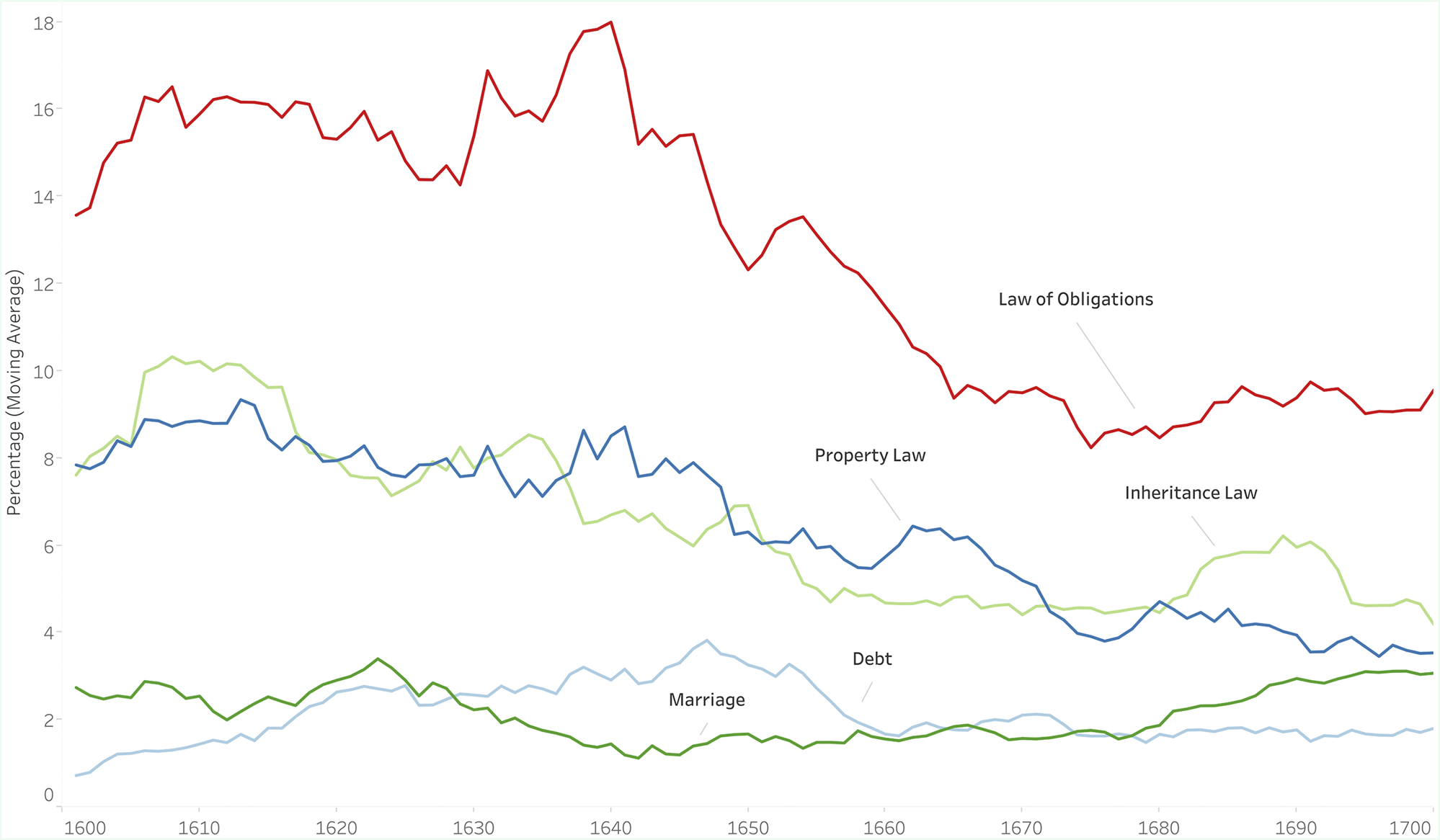

Civil law subjects formed the largest cluster of dissertations (around 35 per cent), including fields like the law of obligations, family law, property law, and inheritance law. However, the proportion of civil law dissertations fell by almost half in the course of the century. This decline can be observed across all principal domains of civil law, with a few notable exceptions (Figure 6).

Figure 6. With few notable exceptions, the number of civil law dissertations experienced a drastic decline in the course of the century. Annual percentage of dissertations mentioning keywords in the law of obligations (commodat*, compensat*, concurs*, condict*, conducti*, conductor*, contract*, credit*, debit*, donatio*, empt*, fideiuss*, hypoth*, interesse, locati*, mora* (excluding moral*), mutuu*, obligat*, pact*, transact*, vendit*), property law (antichres*, domini* (excluding dominic*), emphyt*, fruct*, pign*, possess*, reru*, servitu*, usucap*), inheritance law (collat* + bon*, haered*, hered*, intesta*, inventar*, querel*, success*, testamen*), marriage (communio + bon*, divort*, dot*, matrimo*, morganat*, nupt*, sponsa*), and debt (credit*, debit*, interesse, mora* (excluding moral*), usur* (excluding usurp*) (ten-year moving average, duplicates and reprints excluded). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

Take inheritance law. In old-regime societies, inheritance law played a key role for holding together family estates, especially among the nobility.Footnote 79 While Roman inheritance law had been widely received in the German lands, common law elements remained widespread, such as limitations to freedom of testation in the form of succession contracts (pactum successorium). In the first quarter of the century, up to 10 per cent of all dissertations discussed matters of inheritance law, but that proportion dropped by half by the end of the century. The law of obligations experienced a similarly drastic decline. From hypotheca, an institution that had been successful in the German lands also because it tied in well with other forms of non-possessory pledge, to the sales contract emptio venditio, the proportion of dissertations concerned with the law obligations fell drastically in the course of the century.Footnote 80 The same trend is observable in property law. In the second half of the century, the proportion of dissertations that discussed key concepts of property law, from servitudes to possession, fell by more than half. It is no secret that property law was not the most dynamic domain of seventeenth-century jurisprudence, but the loss of interest is remarkable.Footnote 81

A declining interest in civil law has already been observed in smaller sets of evidence, but the data under consideration here suggests a decline of printed civil law scholarship that was much more comprehensive and starker than previously observed.Footnote 82 This was certainly connected to the emergence of public law and the attraction of employment opportunities in the growing princely administrations, it could even point to a problem of scholarly ‘saturation’,Footnote 83 but a shift of this magnitude is a remarkable development. The number of civil law dissertations declined not just in relation to other fields, such as public law, but also in absolute terms. The total number of dissertations increased significantly in the second half of the century, but the absolute number of civil law dissertations fell: dissertations on the law of obligations, for example, averaged at around twenty-eight per year in the 1610s, but fell to an average of sixteen per year in the 1690s. Many of the civil law institutions charted above played a crucial role in early modern economic life and the history of capitalism. They were the key frameworks for negotiating the ownership of the means of production, for organizing the decentralized production and distribution of goods, for mediating inter-generational wealth distribution, or for investing capital.Footnote 84 The dissertations suggest that large numbers of German learned elites lost interest in the laws that regulated these fundamental mechanisms of economic life, an observation that deserves more scrutiny. While the dissertation titles cannot explain this shift, they raise questions that would deserve further study.

Two civil law subjects eluded this pattern. One is dissertations mentioning creditores, debitores, usury, interest, and debt default (mora), which peaked during the Thirty Years’ War and its aftermath. This could be connected to the debt crisis faced by the lower nobility and many Free and Imperial Cities in the aftermath of the war, attracting legal interest even when jurists lost interest in all other forms of obligation. The other is marriage, which saw a rising interest in the last third of the century, probably an early sign of the Enlightenment discussions around the reordering of familial relations that foreshadowed later reforms.Footnote 85

Similarly, strong connections with broader social trends and current events can be observed in other domains. In public law, where dissertations on current political problems could form part of a student's ‘application portfolio’, Karl Härter described their subject choices as a ‘seismograph’ of imperial politics.Footnote 86 Legal interest in money and questions related to mint peaked visibly during the financial crises (Kipper und Wipper) of the 1620s and the 1670s and 1680s (Figure 7). Many of the dissertations published in those years devote particular attention to the Imperial Estate's minting rights and the debasement of coinage.Footnote 87 These examples show that the dissertations can reveal ‘structural connections between legal reflection and social change’Footnote 88 and that academic jurisprudence was highly receptive to new economic, social, and political developments. If we want to understand better this increasing receptiveness to broader societal issues, we need to take a closer look at the evolution of baroque rhetoric and the gradual shift from dialogic to monologic forms of reasoning.

Figure 7. Legal interest in money peaked during the financial crises of the 1620s and the 1670s and 1680s. Annual percentage of dissertations mentioning pecuni*, monet*, and numm* (ten-year moving average, duplicates excluded). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

IV

In the first half of the seventeenth century, the language of the dissertation titles – a genre closely connected to the oral disputation – increasingly lost its dialogic attributes. This is particularly visible in the decline of the quaestio. Quaestiones were ‘one of the most frequent literary forms in medieval universities’Footnote 89 and the ‘guiding literary genre of scholasticism’.Footnote 90 In rhetoric, the quaestio played a key role for determining the subject of a speech in dialogic form.Footnote 91 A key characteristic of the quaestio was to frame statements as true or false, requiring a reasoned decision for one of two sides. In the seventeenth century, the use of questions in disputations became contentious, as many tended to regard the strict question-and-answer format as antiquated.Footnote 92 Justus Henning Böhmer recognized the virtues of the ‘dialogic method’, but considered it difficult and unsuitable for all but the most gifted writers.Footnote 93 Other eighteenth-century critics of the genre expressed mixed opinions about dialogic disputations and the question-and-answer model but still recognized its advantages over syllogistic reasoning.Footnote 94

Another emblematic indicator for the dissertations’ polyphony was controversia with its adjectival variations. In the rhetorical tradition, controversia was a matter of dispute or a legal case that played an important didactic role.Footnote 95 It designates a discursive model with neatly drawn battle lines between attack and defence, as in case law. The subjects of controversiae were commonly formulated as questions. In contrast to syllogistic reasoning, controversiae based arguments on probability. This made it a particularly attractive format for discussing questions where proof was a matter of probability rather than absolute validity. In German legal dissertations, controversiae were often collections of dichotomous questions that a student was to decide by using various legal sources and scholarship.Footnote 96

Figure 8. In the first third of the century, many dissertations were written in dialogic form, but these were increasingly supplanted by more single-voiced and monographic texts. Annual percentage of dissertations mentioning the keywords quaest* and controvers* (ten-year moving average, duplicates and reprints excluded). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

Quaestiones and controversiae were very common in dissertation titles during the first third of the century, but jurists used these words much less frequently from the 1640s onwards (Figure 8). The sustained decline of quaestio and controversia in the course of the century underscores a development that other scholars have ‘conjectured’Footnote 97 with ‘much caution’ but struggled to substantiate: the turn from a ‘polyphonic disputation’ to a ‘respondent's monologue’. This declining stature of dialogue and controversy reflected broader changes in German academic culture towards the end of the seventeenth century. Oral disputations lost their adversarial character and became a ‘gallant act of conversation’.Footnote 98 Disputants used a conciliatory and understated tone rather than demonstrating intransigence.Footnote 99 Imitating courtly conventions, scholars apologized for disagreeing with their opponents, avoided altercations and direct negation (such as nego hoc, absurdum est), embellished their speech with compliments, and generally tried to appear sympathetic and meek.Footnote 100 The waning marks of dialogic antagonism and controversy in the printed dissertation titles could be a further symptom of this development.Footnote 101 The fact that the attributes of the oral, adversarial disputation dissipated gradually, over the course of the entire century rather than just in the space of a few years, indicates that this was a long-term, structural evolution rather than a short-lived phenomenon. Hanspeter Marti, who knows this corpus like no other, has remained wary of the idea that dissertations (legal and other) saw a ‘linear process of literalization’.Footnote 102 It is true that the marks of orality never disappeared entirely from the printed dissertations. However, the data under consideration here do suggest a gradual, linear process in which a growing number of seventeenth-century law dissertations took on more single-voiced and monographic forms that gradually replaced the short collections of quaestiones and controversiae that characterized the oral disputation.

While it is tempting to think of the quaestio as an intellectually constraining format, it had been fundamental to freeing scholastic thinking from textual authorities and allowing for a more independent treatment of scholarly problems.Footnote 103 Disputing was not about indiscriminately rejecting opposing arguments, but about differentiating problems and narrowing them down.Footnote 104 A plurality of opinions was fundamental to a mode of reasoning that required attentive references to every proposition made by the other party. This was also recognized by later collectors who appreciated how disputations confronted the reader with multiple opinions, stimulating them intellectually.Footnote 105 Eminent eighteenth-century scholars like Christian Thomasius saw the dialogic question–answer disputations as a tried and true method of pursuing knowledge, used it to experiment with new forms and content, and actively tried to reinforce it vis-à-vis other media of scholarly communication.Footnote 106 Indeed, the decline of quaestio and controversia experienced a slight reversal in the last decade of the seventeenth century. This late renaissance of quaestio and controversia happened at the University of Halle, where Christian Thomasius and Johann Samuel Stryk published two long series of dissertations on the public law of the Holy Roman Empire (Thomasius) and on the Pandects (Stryk) framed as quaestiones and controversiae. Christian Thomasius valued the disputation's dialogic question–answer format and its public character to the point that he was dubbed ‘the German Socrates’.Footnote 107 The resurgence of the dialogic model in Halle at the end of the century is also a good example of how a comprehensive view of the dissertations can offer a powerful corrective to ‘one-dimensional modernization theories’Footnote 108 and teleological master narratives.

The overall declining appeal of dialogue and controversy had effects on the way jurists defined the subjects of their dissertations. The dialogic dissertations mostly focused on questions that were established enough to spark controversy. Approaching a subject through quaestiones and controversiae made sense where there was scholarly disagreement that could be articulated in arguments and counterarguments. While single-voiced dissertations also weighed conflicting points of view, in this model, controversy was an option rather than the defining framework. As many dissertations lost their antagonistic layout, their authors became keener on exploring subjects that were original rather than controversial. This simultaneously broadened and sharpened thematic scope is the subject of the following section.

V

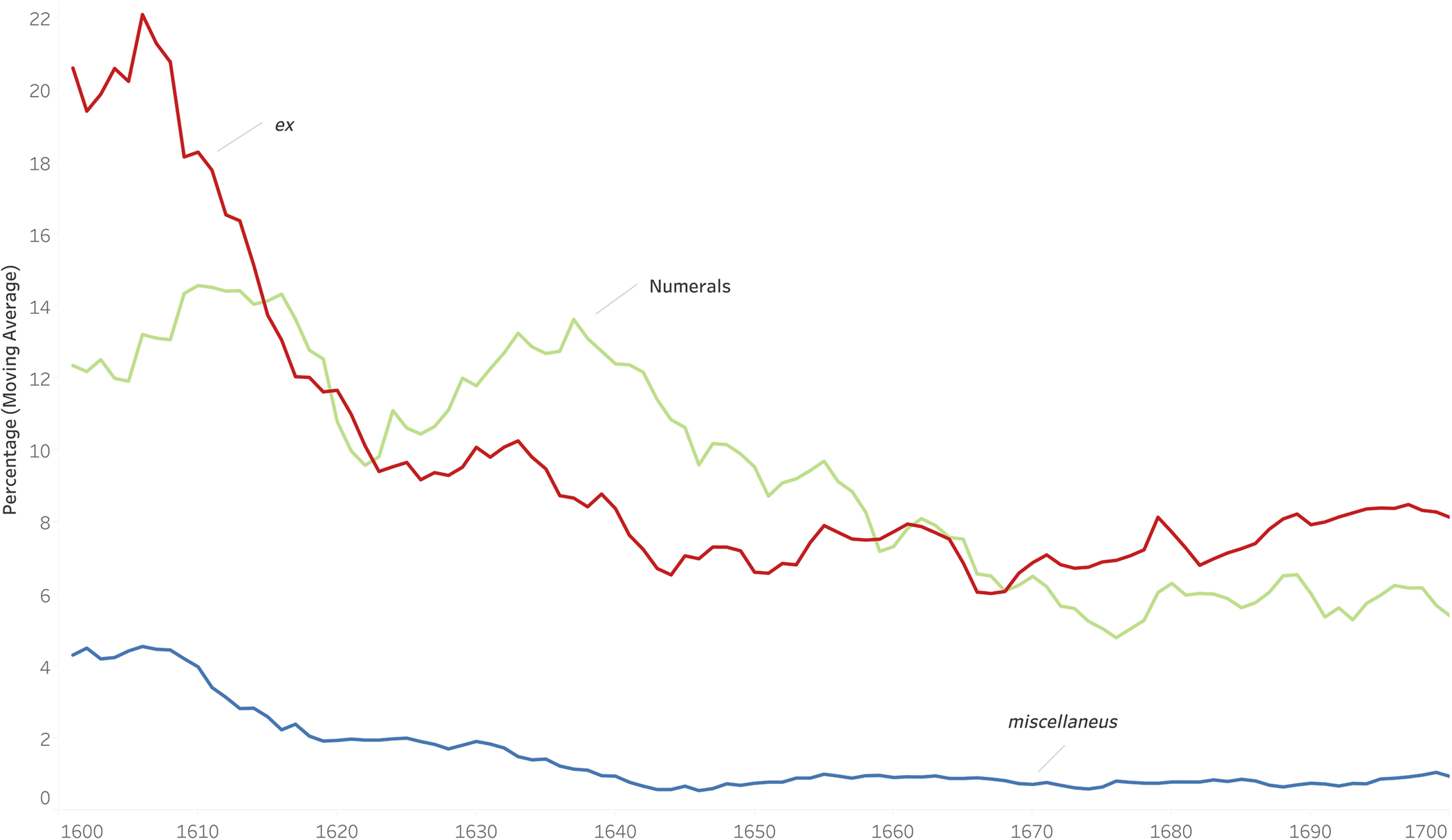

Dissertations compiled of quaestiones, controversiae, positiones, theses, themata etc. often drew their subject from different fields, subjects, and law sources. The titles did not hide the texts’ assorted nature. Numerals specified the number of theses, positions, questions, and controversies addressed – the more the better.Footnote 109 Dissertations contained decades duae controversiarum, politicarum propositionum decas una, or decas quaestionum iuridicarum. The plurality of questions covered in a dissertation was also expressed with the attribute miscellaneus. Such assorted theses allowed disputants to prove their mastery of various fields and were therefore a preferred format for graduating students in some universities.Footnote 110

The most telling indicator is perhaps the little adverb ex, which connected the assemblage of theses to broader subject matters (Decuria controversarum quaestionum ex ususfructus materia decerptarum), to the classic texts of Roman Law (Disputatio XXX. ex lib. XLIII. pandect. desupmta), and to different fields of jurisprudence (Quaestionum controversarum ex iure civili, canonico, et feudali depromptarum). Framing a study as part of an established theme, source, or field of the law, ex indicates a key pattern of thought in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century dissertations: legal scholarship was about revealing the truth contained in established texts rather than opening new fields of empirical enquiry. It is a good example of why it can be interesting to ‘take those units of language that are so frequent that we hardly notice them and show how powerfully they contribute to the construction of meaning’.Footnote 111

All these features declined substantially in the course of the century (Figure 9), as large shares of the dissertations developed from motley assemblages into thematically focused and monographic treatises.Footnote 112 Their authors did not feel the need to highlight the variety of questions or to situate the titles within broader fields of knowledge. A Disputatio inauguralis de ignorantia did not need to justify its interest with references to Justinian, the Pandects, or established taxonomies of knowledge. Introduced with a simple ablative and the monosyllabic de, the subject stood for itself.Footnote 113

Figure 9. While earlier dissertations often drew their subject matter from different fields and sources, jurists increasingly preferred more sharply delineated, diverse, and sometimes original subjects. Annual percentage of dissertations mentioning numerals (duae (excluding viduae), tres (excluding illustres), quatuor*, quart* (excluding einquart*), quinqu* (excluding quinquen*), quint*, sex* (excluding sexu), sept*, octav*, nona, deca*, decim*, dodec*, vigint*, trigint*, quadrag*, centum), miscellan*, and ex (ten-year moving average, duplicates and reprints excluded). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

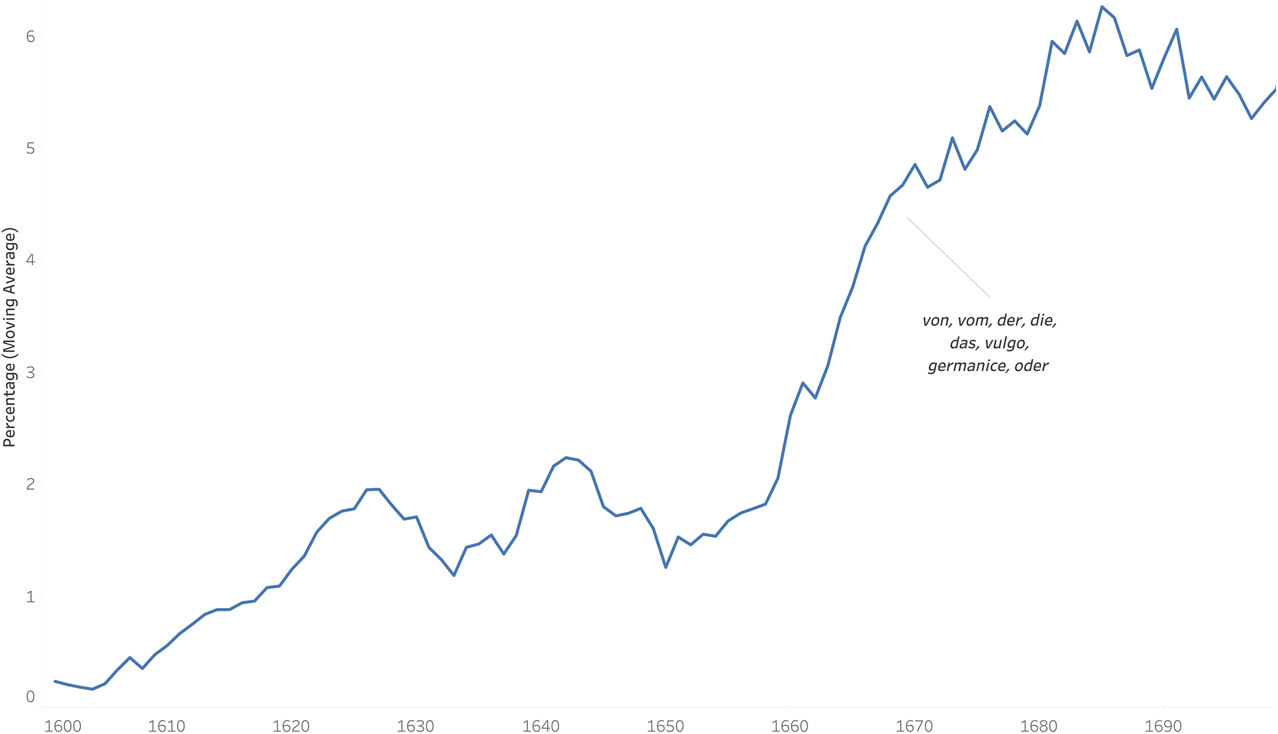

The dissertations’ heightened thematic focus also facilitated the use of the German language in the titles. To be clear, Latin remained the dominant academic language in German universities well into the nineteenth century: of the hundreds of thousands of early modern dissertations, less than fifty were written in German.Footnote 114 While the ‘overwhelming hegemony’Footnote 115 of the Latin language came under increasing pressure only in the second half of the eighteenth century, the dissertation titles show that the acceptance of German in academic jurisprudence increased visibly in the last third of the seventeenth century (Figure 10).Footnote 116 Monographic dissertations that treated clearly circumscribed subjects, many of them connected to the authors’ lifeworld and customary law, made it plausible to use double titles (Discursus iuridicus de clamore violentiae, vulgo Zetter-Geschrey) where the subject of the dissertation – in this case: loud scolding – was given both in Latin and in German, often specified by words like vulgo or germanice. In the dissertations themselves, German was often used in dedications and quotes.

Figure 10. Latin remained the dominant academic language well into the nineteenth century, but in the last third of the seventeenth century, the German vernacular began to appear more frequently in dissertation titles. Annual percentage of dissertations mentioning the words der, die, das, germanice, oder, von, vom, vulg* (ten-year moving average, excluding duplicates and reprints). Data source: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachraum erschienenen Drucke des 17. Jahrhunderts (2020).

One could assume that German terms were added to titles in cases where a concise Latin terminology was lacking.Footnote 117 While this was indeed sometimes the case – a good example is a dissertation on blood money (Disputatio iuridica de werigeldo sive Wehrgeldt) – most of the vernacular vocabulary in the dissertation titles was well established and comprehensible in Latin, as a 1682 dissertation on poisoning entitled Disputatio iuridica de venenis et veneficiis vulgo von Gifft und Vergifftunge. That titles were given in German when there was an established Latin vocabulary sparked controversy in an academic community that jealously guarded its linguistic walls.Footnote 118 Critics feared that the use of the German language would lead jurists to neglect succinct definitions, subtle conceptual distinctions, and secular traditions of scholarship.Footnote 119 Sigmund Jakob Apin complained that some authors only used German and other ‘fashionable titles’ to please their publishers.Footnote 120 However, in the long view, what to Apin looked like a short-lived fashion ‘worth laughing at’ was really a widespread, gradual, and sustained trend indicating that the acceptance of the German vernacular in academic jurisprudence has its roots well before the late eighteenth century.

The decline of quaestio and controversia and the increasing thematic compactness went hand in hand with a gradual easing of the logical and rhetorical constraints placed on dissertations. Arguments from authority and strict schemes like the genera causarum lost in importance and scholars were encouraged to think more independently and write more freely.Footnote 121 At the turn of the century, jurists encouraged novelty (‘reheating the same cabbage is tedious’Footnote 122) and subjects ‘with utility in practice’Footnote 123 rather than ‘naked theory’.Footnote 124 Disputations on arguments that were ‘too paltry and of no use, or clearly very difficult to solve’Footnote 125 fell into disrepute. Scholars made fun of the far-fetched questions asked in older scholastic disputations (‘Is the number of stars even or odd?’Footnote 126). Whereas sixteenth-century scholars tended to favour knowledge distinguished by age and tradition, their successors developed ‘a more vital curiosity for the unknown’.Footnote 127 The lawyers’ penchant for novelty reflects a broader revaluation of curiosity in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 128 The breadth of the lawyers’ interests was shared by polymaths in neighbouring disciplines whose aspirations could be ‘so sweeping as to boggle the modern mind’.Footnote 129 The search for novelty was further reinforced by university regulations that required disputations to treat new and original subjects.Footnote 130 Justus Henning Boehmer reminded his readers that ‘there are thousands left over that have [only] been treated lightly by others so far and are, as it were, unuttered by another mouth’.Footnote 131 The novelty of a dissertation was also an important criterion for collectors, who valued subjects that were ‘rare and [had] never been examined before’.Footnote 132

A key characteristic of this development was that jurists attempted to systematize a wide range of norms and observations around a single theme or question. This could be a fairly straightforward exercise – think of dissertations on fields like neighbourly relationsFootnote 133 – but it required more creativity and imagination in other cases, as in dissertations on anger,Footnote 134 on curiosity,Footnote 135 or on people who meddle in others’ affairs.Footnote 136 Thematic differentiation could be driven by practical concerns, as in the case of peasant law (Bauernrecht), a diverse subject matter that was increasingly detached from Roman civil law and recast in the perspective of particular and natural law.Footnote 137 To be clear: the majority of dissertations continued to treat conventional subjects, but the number of novel dissertation subjects increased markedly in the latter part of the seventeenth century, offering new and unique perspectives on how learned contemporaries understood the world they inhabited. In their search for novelty, their authors frequently turned to seemingly mundane, peculiar, and variegated elements of everyday life. Some jurists evinced a set of interests that two centuries later were taken up by cultural and social anthropologists. In these cases, the dissertation became an original and innovative genre in which lawyers could survey a wide array of questions and systematize apparently unconnected phenomena under one heading. Thus, a dissertation on the law of nudity offered a framework for linking discussions around bathhouses, sexuality, witchcraft, torture, headscarves, royal crowns, rape investigations, abortion, bare feet, and the problem of baldness.Footnote 138 Overall, historians who are interested in the idiosyncrasies of this archive may find the monographic, more thematically varied, focused, and frequently original dissertations of the later decades of the seventeenth century of greater interest than the more conventional, rigid, and collated disputations of earlier decades.

These associations add to the historiographical value of the dissertations of the late seventeenth century. The early modern lawyers’ efforts at highlighting common threads between seemingly disparate objects, discourses, and practices remind one of their historians who also rearrange their evidence to create new narratives and highlight new relations. The legal dissertations of the late seventeenth century offer an almost inexhaustible source of associative licence from the past that few historians would dare to afford on their own. In my recent study on the history of borders and freedom of movement in the Holy Roman Empire, for example, it was striking to observe how questions related to freedom of movement and its restriction were treated extensively in texts around the legal nature of roads and rivers, but not in the (otherwise abundant) legal dissertations on boundaries.Footnote 139 This indicated that for early modern jurists, borders and boundaries were not yet a shorthand for state interferences with human mobility, as they would be in later centuries. The fact ties in with the broader observation that boundaries played a subordinate role in the channelling of human mobility up until the mid-eighteenth century. Both intellectually and practically, most forms of mobility were regulated along corridors and thoroughfares, not boundaries. In this case, the dissertations’ silence was as instructive as their verbosity.

In the history of political ideas, the Old Reich has often been regarded as a harbour of a ‘conservative, if not authoritarian, conception of the state and society’.Footnote 140 The dissertations qualify such views. Although disputations often followed strict conventions, the written dissertations made it possible to circumvent censorship and express controversial ideas on sensitive issues, such as atheism.Footnote 141 At Halle, for example, disputations by ordinary professors were exempt from censorship, encouraging them to pursue unconventional ideas.Footnote 142 In seventeenth-century dissertations on roads and rivers, transit rights, and safe-conduct, scholars formulated bold and unconventional theories on the relationship between human mobility and political authority. A dissertation On the right of passing through territories published at Strasbourg in 1672, for example, formulated one of the boldest apologies of freedom of transit presented in the German lands during the seventeenth century.Footnote 143

Another recipe for originality was to embrace metaphor. Metaphorical connections could let a dissertation's subject explode, as in the case of a 1681 dissertation on shadows.Footnote 144 The range of issues covered by the authors include the physics of light, building law, the representation of shade in the pictorial arts, ghosts, curtains, people's fear of the dark, and the placement of gibbets on territorial borders (so that the shadow does not fall on neighbouring land). The shadow as a metaphor, however, allowed the authors even to include subjects like slander (‘throwing shade’) or how to deal with unwanted visitors who tend to follow invited guests, like a shadow.

Because the jurists’ writings were closely connected to the immediate practical concerns of their authorities and of the communities they lived in, they also reference a wealth of local and regional customs and traditions. A dissertation from 1683, for example, was entirely dedicated to discussing the legal implications and customs of New Year's Day.Footnote 145 The dissertations heavily quote municipal, territorial, and imperial ordinances and can be used as repertories of regulations around various subjects. Questions of bodily practices come up in many dissertations, like a 1667 study on shaving, and should be of particular interest to cultural historians.Footnote 146 A 1688 dissertation on The law of jest offered an extensive discussion of different types of jokes, the kinds of people one could make fun of (one's equals) and those with whom jokes were better avoided (one's enemies, old and sick people), as well as subjects that were inappropriate (such as sacred things or marriage), as well as positive laws and punishment for inappropriate humour.Footnote 147

Other dissertations were concerned with specific economic sectors such as the cultivation and trade in flowers or the tobacco trade.Footnote 148 Indeed, some dissertations provide extensive treatment of forms of production and consumption for which sources do not abound otherwise. A good example is a 1700 dissertation on the law of pearls of over 100 pages, which was significantly longer than the average dissertation.Footnote 149 The text discusses the formation, origins, and cultivation of pearls as well as their uses in different walks of life, offering a rich source for cultural and economic history. The business of gravedigging was discussed extensively in a dissertation from Frankfurt/Oder, offering insights into the regulation of this profession and funerary practices in early modern German lands, and going as far as discussing necrophilia.Footnote 150 A 1665 dissertation on taste offers insights not only into the trade of wine and oil, but also into early modern notions of hygiene and pollution.Footnote 151 The boundaries and protection of different professions was extensively discussed in a dissertation on charlatans.Footnote 152 Dissertations that were concerned with the effects of natural disasters – from locusts to storms – will be of interest to environmental historians.Footnote 153

The originality of many dissertations written in the latter part of the seventeenth century has often been overlooked by non-specialists and regularly met with scepticism by those who were more familiar with the corpus. Ewald Horn, the inauspicious early doyen of this historiography, found subject matters like the ones described above ‘most abstruse’.Footnote 154 Leaving aside the question of whether historians are even equipped to distinguish ‘satirical’ from ‘serious’ dissertation subjects, it would certainly be ill-considered to class all unusual subjects as ‘jest dissertations’. The label is probably appropriate for dissertations with fictitious names and dates created for the express purpose of entertainment, but those are few and far between.Footnote 155 In practice, even contemporaries who were critical of the genre recognized the value of satirical disputations to treat sensitive subjects.Footnote 156 Moreover, facetious and serious elements could be intertwined.Footnote 157 That idiosyncratic subjects raised sustained interest among contemporaries is also suggested by the fact that they were frequently reprinted.Footnote 158 In his 1703 disputation guide, Justus Henning Böhmer published a long list of disputation subjects that he considered worth disputing. The list, intended as inspiration for prospective disputants, mixed relatively conventional themes with subjects such as the law concerning immoderate drinking, ink, or tearing one's hair out (Von Haar-rauffen).Footnote 159 The facility with which the older literature dismissed these subjects as jokes says more about nineteenth-century historiography than it tells us about seventeenth-century jurisprudence.

VI

This article has highlighted some of the shifting interests and methods of the anonymous mass of jurists that populated universities, courts, chanceries, and offices across the Holy Roman Empire. The dissertations offered a medium to debate current issues, such as inflation and the debasement of coinage, but the jurists’ changing preferences also raise new questions. The dramatically declining interest in civil law subjects, both in relative and absolute terms, shows how large numbers of the learned elites lost interest in discussing fundamental institutions of economic life, from the sales contract to the testament. The adoption of more single-voiced and monographic forms and the gradual easing of formal constraints went hand-in-hand with a preference for new, original, and clearly delineated subjects. While the way in which seventeenth-century jurists expanded the scope of their discipline reflects broader revaluations of scholarly curiosity and baroque polyhistorism, it also bears witness to an epistemic community that felt increasingly entitled to interpret the world through its own categories. The way in which law professors and their students widened the scope of phenomena studied under the label of jurisprudence can be seen as a further indication of the juridification of public life in the seventeenth-century Holy Roman Empire. In the German lands, law became an increasingly important vector for regulating public issues and societal tensions.Footnote 160 Reflections on matters of public concern were increasingly placed in the hands of jurists, a loyal and economically dependent ‘secular priesthood’Footnote 161 that spoke its own arcane language and held important positions in the princely courts and administrations. The universities offered the stunted bourgeoisie an entry into academic professions and generated a strikingly rich and diverse intellectual production. In the Old Reich, legal process became a ‘substitute for politics’.Footnote 162 This increased stature justified the confidence with which jurists like Justus Henning Böhmer argued that any problem that could be studied under the notion of ‘just and unjust’Footnote 163 fell into the remit of jurisprudence. ‘A jurist can claim all things and matters for himself’Footnote 164 wrote Böhmer. The dissertations show how seventeenth-century lawyers enacted this ambition. Their titles tell a history of entitlement.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Sarah Ludin and Gerardo Serra for providing invaluable comments on early drafts of this article, as well as the two anonymous readers for their generous and productive reviews. I also thank Zephyr Frank and Mark Algee-Hewitt for our conversations in the early stages of this project. For access to the data, I thank Andrea Diedrich (Gemeinsamer Bibliotheksverbund) and Michaela Scheibe (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin).