If the publication of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990) marks a key and hugely influential moment in the analysis of internal, queer spaces and forms of literary closeting, then the past decade has seen a significant growth in interdisciplinary, scholarly work focusing on closets/closeting located in earlier historical contexts (before 1880 moving backwards into the eighteenth century).1 This chapter engages with this work, whilst also proposing new ways of reading and analysing Anne Lister’s life writing and negotiation of identity. It introduces the concept of the self-conscious closet and the protective diary code-cover, and their links to Lister’s paradoxical aesthetics. Lister’s code-cover operates as a multifunctional device, serving as a comfort blanket, an exclusionary barrier and an indicator of status and learning. This chapter also reflects on Romantic and classical intertextuality in the journals and asks how this intertextuality contributes to tropes of binary space, as well as foregrounding concerns with thresholds. Finally, it analyses the importance of the recent archival discovery of Ann Walker’s diary (1834–5) and how this sheds new light on Lister’s diary writing, offering new opportunities for a comparative analysis of identity and its refusal.

Spatial Tropes

Lister’s diaries have often been labelled colloquially as the ‘Rosetta Stone’ of lesbian or queer women’s writing and a treasure trove for scholars working on writing, gender and sexuality in the early nineteenth century. From the start of the diaries, Lister is keen to display her erudition as a classical scholar and reader. The first clear reference to classical texts appears in Lister’s loose diary notes of 1808: ‘Wednesday March 2nd Begun Xenophon’s Memorabilum and left off Horace for a while. Monday 7th Begun Tacitus Life of Agricola.’2 However, I want to propose a different classical source for my initial analysis. The most obvious reference to charged interior spaces in classical mythology is contained in the tale of Pandora’s box. In the myth, Pandora is described as the first human woman and instructed not to open the box that she receives as a wedding gift. Pandora disobeys, and by opening the box she unleashes the evils of the world, but leaves hope left inside. Classical scholars are still debating whether the survival of hope is a trope of human resilience, or a reminder to maintain faith in even the darkest times. As Todd Worner notes: ‘Too often the myth’s focus is on the evil that is let loose, and not the hope that remains. But what an omission! The endurance of hope embodies just what we have left when all else has gone wrong. And it is simply brilliant.’3

Pandora was still a source of cultural fascination in later nineteenth-century painting and sculpture; the best-known images are provided by the Pre-Raphaelites, as in John William Waterhouse’s Pandora (1896). It is likely that Lister would have been familiar with early nineteenth-century versions of this classical tale and the link to Hesiod’s Works and Days. Pandora is enticed by an ornate and elaborate box (originally a jar) which flamboyantly draws attention to its complex construction and use of ancient shorthand and symbols. Lister is also seduced by classical knowledge and linguistic ornamentation. The diary’s cipher key pulls both the writer/s/’ and readers’ focus in opposite directions, asking to be acknowledged but also obscured in a kind of ambivalent dance. Lister may possibly have developed her code with help from her boarding-school first love, Eliza Raine, given that their early letters are partly encoded, or more likely (given Lister’s interest in classical languages and algebra) she invented it on her own and then passed on the key to Raine.4 In any case, Lister later shared the code with a small number of other confidants.

With its showy outer casing and complex interiority, the structural elements of Pandora’s box work as a particularly appropriate analogy for Lister’s diary writing. While Lister’s diary can contain transgressive material within a safe, private space, as with Pandora’s box it is also potentially at risk of discovery and of being ‘revealed’. Furthermore, Pandora’s box forms an uncanny parallel with Lister’s code in the residual hope it offers. The word ‘hope’ famously provided the key to the cipher for John Lister and Arthur Burrell’s code breaking:

And telling Mr Lister that I was certain of 2 letters, h and e; and I asked him if there was any likelihood that a further clue could be found. We then examined one of the boxes behind the panels and half way down the collection of deeds we found on a scrap of paper these words: ‘In God is my … . ’. We at once saw that the word must be ‘hope’ and the h and e corresponded with my guess. The word ‘hope’ was in cipher. With these four letters almost certain we began very late at night to find the remaining clues.5

It may seem that the word itself is a pure coincidence, in that it could have been any word discovered by Burrell and Lister, yet there are a number of diary entries that reinforce the value Lister placed on stoicism, faith and progress. For example, on 8 September 1835, she notes: ‘Would that we could look on the past with satisfaction, on the present with complacency, and to the future with hope.’6

Lister’s use of the term ‘crypt’ rather than ‘cryptic’ in describing her code and coded writing also opens up some intriguing linguistic possibilities. The Oxford English Dictionary lists crypt as ‘[a]n underground room or vault beneath a church, used as a chapel or burial place’, whereas the Cambridge Online Dictionary offers the following definition: ‘A room under the floor of a church where bodies are buried.’7 Ironically, Lister’s ‘bodies’ are also buried under the crypt space, although Lister imagines their resurrection through the language of anxiety, as in the following entry from 1819:

Isabel much to my annoyance, mentioned my keeping a journal, & setting down everyone’s conversation in my peculiar handwriting (what I call crypt hand). I mentioned the almost impossibility of its being deciphered & the facility with which I wrote and not at all sharing my vexation at Isabella’s folly at naming the thing. Never say before her what she may not tell for, as to what she ought to keep or what she ought not to publish, she has the worst judgement in the world.8

Isabella’s declaration creates danger and threat precisely because it fails to recognise both the crypt and cryptic elements of Lister’s diary writing. It also confronts the edge of Lister’s social closet and tries to wrest control away from the closet’s owner, potentially outing her in the process. This interaction highlights the precarity of Lister’s social closeting, in that someone in her inner circle can fail to acknowledge the need for discretion.

Self-Conscious and Unconscious Closets

I argue that Lister’s diary cipher acts as a cover and protection from unwanted attention in the same vein as a physically locked journal. Despite the huge volume of research on the history of diaries, there is a surprising gap or silence regarding diary locks and their use in life writing. The diary’s internal space acts as a room of requirement, or a specially reserved space akin to architectural and domestic closets used by the aristocratic classes in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Dominic Janes’s and Danielle Bobker’s recent publications on links between queer sexuality, intimacy and architectural closets in the eighteenth century have provided a very welcome addition to research on spatial and psychological closets, although their primary focus is on male writers and historical figures.9

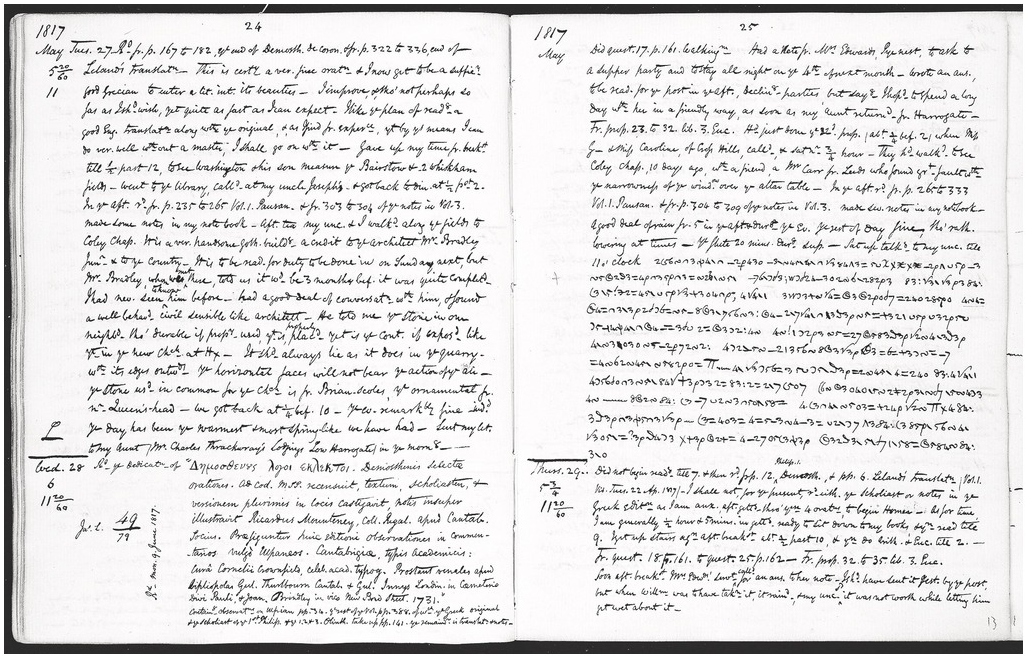

Figure 4 Anne Lister diary entry (28 May 1817). West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale, sh:7/ml/e/1/0014.

Bobker’s linking of eighteenth-century closets with twentieth- and twenty-first-century coming-out stories is a timely intervention for those who are working on links between literary structures, psychological processing and queer spaces. The closet as the space of identity construction is moving backwards in recent scholarship away from Michel Foucault’s late nineteenth-century designation of this phenomenon.10 Here, I need to clarify the difference between an externally imposed closet and a self-conscious closet, the self-conscious closet being the less dangerous or harmful of the two. In an ideal world, no one should ever need a closet. The paradox is that if you know you are in a closet and you acknowledge your othered identity, then your closet is never fully sealed or closed. However, historically individuals with self-conscious closets remain subject to threats from external readings and judgements, hence the need for protective, linguistic armour.

Furthermore, Lister’s peculiar handwriting still represents a challenge for those looking at the diaries and the wider Lister/Shibden Hall archives. Researchers have recently discovered a diary entry previously thought to be part of Lister’s diaries that has now been re-attributed to Ann Walker and included within her year-long diary as part of a project to collate and transcribe Walker’s writing.11 The related Twitter account and website now provide researchers with a chance to compare diary entries written by Lister and Walker during 1834 and 1835. The fact that Walker did not use code suggests that she did not invest in a self-conscious textual closet in the same way as Lister. This is extremely valuable information for scholars looking at self-identity and self-processing in Lister‘s diaries. This dual archive now offers a way to map differences in perception and disclosure in both women’s work. Comparing the two would suggest that no explicit sexual content equals no explicit code.

For example, comparing Walker’s and Lister’s entries for Sunday, 24 August 1834, there is a clear difference in their content. Lister’s entry contains a brief coded section describing their intimacy: ‘she with me in my bed half hour this morning but quite quitely [quietly]’, whereas Walker’s entry begins with a reference to breakfast: ‘Up at 8.20. breakfast, and gaitner came with gaiters, had them to alter.’12 Walker’s and Lister’s entries from the day before (Saturday, 23 August 1834) follow the same pattern. Walker writes: ‘Up at 10 to 6 – wrote letter to my aunt Monsieur Perrelet brought watches,’ whereas Lister’s entry is as follows: ‘[up at] 8 ¾ [to bed] at 12 ¼ good kiss last night – up at 6 ½ a.m. with regular bowel complaint – Perrelet a little before 9’.13 It is interesting to note that Lister does not code the reference to her bowels after her coded ‘kiss’. The omission of sexual details from Walker’s diary entries provides an intriguing contrast to Lister’s focus on sexual satisfaction and a poignant commentary on the differences between the two women’s approaches to recording their activities and their sense of identity. In Walker’s diary, the notion of platonic, romantic friendship is inscribed by the omission of any sexual reference, while Lister’s diary persona of the same period seems increasingly frustrated.14

Domestic and Physical Closets

A direct search of the word ‘closet’ within the complete diary archives produces seven results: five direct and two indirect. The references are contained in diary entries written between Thursday, 9 April 1818 and Sunday, 15 October 1820. At first glance, these entries seem unremarkable; however, on closer inspection they exhibit an intriguing link between physical and textual closets, offering rare examples of explicit, non-coded content near or within physical closets, such as china, bedroom and water closets.15

The following example links Lister’s studies to her bedroom closet: ‘(Could not however, manage to get the right answer to example 4, page 123.) then moved all my things out of my room (the blue room) closet and dawdled away all the morning.’16 In this entry, the connection between ‘the blue room’ and the closet is not clear, or even whether they are the same thing. The bracketing of the blue room is also odd and reads as though Lister is providing clarification for those unfamiliar with the layout of Shibden Hall. The next relevant entry is dated Saturday, 18 July 1818, and follows a similar pattern, as Lister summarises her reading progress and notetaking: ‘Read from page 403–420 volume 3 Les Leçons de l’Histoire, in the china closet, finding this place not quite suit me, went into the red room, read section 28 librum 1… overcome with the heat slept near an hour.’17 Once again, we note the strange use of a china closet space and the lack of any accompanying qualification or explanation. The same entry contains a reference to a third type of closet, namely a water closet: ‘Just before dressing (Mariana) proposed our going down to the water closet where all over in five minutes she gave me a very good kiss.’18 This entry creates an explicit link between the physical space of the closet and the recording of sex between women. The final closet entry from 15 October 1820 also includes a mention of potential sexual activity in the water closet:

Directly on our return from church saw Miss Vallance in the passage took her near the downstairs water closet jammed her against the door and excited both our feelings very came upstairs and leaned on the bed she soon came in and saw the state I was in was bad enough herself and at last promised not to refuse me tonight.19

As water closets adjoining bedrooms were being developed as early as the seventeenth century, there is a longstanding link between closets and sanitation: ‘In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries small rooms or closets were introduced that adjoined bedrooms. These areas were outfitted with a comfortable commode, under which a pan would be placed.’20 In Lister’s entry above, the water closet as a sanitary space and as a space for illicit sex between women blurs the boundaries between the proper and the improper, and the clean and the unclean.

Working out what a closet is or is not in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century is still a challenging proposition for historians and literary critics. According to Bobker, ‘Closet was the generic term for any lockable room in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British architecture. As private wealth grew, closets of all kinds were increasingly available across the social spectrum.’21 A further search of references to ‘water closet’ on the WYAS catalogue produces two entries including the ones mentioned above and the following note dated 19 February 1820: ‘Mr D. [Duffin] and I walked with Mrs A. [Anne Norcliffe] and Miss G. [Gage] – kiss in the water closet.’22 Both entries include coded references to orgasms (kisses) occurring in a space that can only be entered by invitation. The qualification of the term ‘closet’ with ‘water’ is helpful in negotiating the lexical ambiguity of the term, marking it as a room rather than a piece of furniture; the water closet as a lavatory or commode room rather than a pot or toilet. Historically, the water closet has moved from a space of shared, aristocratic intimacy in the enfilade to a space usually associated with individual and private use in middle-class homes.

Thresholds and Risk-Taking

The foregrounding of paradoxical space continues throughout the diaries, with their emphasis on layered discourses, liminal spaces and movements across thresholds, as well as the negotiation of binaries more traditionally associated with diary writing: public/private, inside/outside and so on. In addition, Lister created symbols of protection and invitation in her domestic space by the placing of unusual female carved figures on the main staircase of Shibden Hall. The staircase figures mark the edge of public space, providing not only a form of protective guardianship, but also a possible queer invitation, in a vein similar to Christabel’s chamber in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem of the same name (1816):

The time-span of Lister’s life and diary writing overlaps with the evolution of the dark Romantic era of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Anira Rowanchild and Alison Oram have explored connections between the gothic and Lister’s textual and social aesthetics in their work.24 Rowanchild’s analysis of gothic connections also provides a succinct summary of competing antinomies in Lister’s world, by arguing that ‘[Lister’s] interest in the picturesque and Gothic was stimulated by their ability to combine display with concealment.’25

I want to suggest a further correspondence between vampiric tropes in Romantic literature and ideas of risk-taking and control in the crossing of Lister’s closeted and uncloseted thresholds. The first notebook of Lister’s diary (not in loose-leaf form) is dated from August to November 1816, the same year as Coleridge’s ‘Christabel’, although the volumes which constitute this unfinished poem were composed at an earlier date. While not directly mentioned by Lister, this text provides an intriguing contemporary example of problematic, vampiric thresholds:

The topos of invitation runs through vampiric literature throughout the nineteenth century, as in, for example, Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla (1872), in which Carmilla is invited into Laura’s home after a carriage accident. In the same way, Lister issues invitations to her private spaces – both linguistic and physical – to select members of her inner circle but keeps unwanted guests in her wider social circle at bay by using the cipher as a gate. This is not to suggest a literal correspondence between Lister and the vampiric, but rather that her diary writing shares certain characteristics with gothic literature, including a focus on inclusion and exclusion, entry, permission and consent, all of which designate sites of anxiety and erotic charge in early nineteenth-century texts.

While Lister’s code-cover system of crypt hand, secure containment and limited circulation of diary writing is undoubtedly robust and comforting, there are occasions in the diary when she appears confused in her understanding of public/private boundaries and the differences between protected and non-protected spaces. There is one notable instance where Lister’s desire to make a romantic and Romantic gesture undermines the stability of her social and textual closet. In the famous ‘Blackstone Edge’ or ‘three steps’ entry of 19 August 1823, there is an odd inconsistency in the use of the code cipher, with content that would seem to be ripe for coding remaining uncoded. This, in turn, mirrors the emotional and psychological trauma being experienced in the moment and in later references to the incident. In this episode, Lister walks briskly across open countryside beyond the boundaries of the Shibden estate, with the goal of surprising her lover, Mariana Lawton, who is traveling by coach from York towards Halifax. Upon reaching the coach, Lister describes ‘in too hastily taking each step of the carriage & stretching over the pile of dressing-boxes etc., that should have stopped such eager ingress, I unluckily seemed to M – to have taken 3 steps at once’.27 Mariana, in turn, is ‘horror struck’ at Lister’s sudden appearance, which signals a complete lack of proper decorum.

Although Lister thinks she is safe in wanting to surprise her lover, on reflection she records in her diary having breached a prohibited boundary, both physically and symbolically. This entry contains a rare instance of shame being internalised or breaking through Lister’s protective mechanisms and provoking a split subjectivity: ‘I scarce knew what my feelings were. They were in tumult. “Shame, shame,” said I to myself, “to be so overcome.”’28 This long entry moves between coded and uncoded sections, although the same emotional tone is maintained throughout. While the following line is coded, ‘I felt more easily under my own control,’ the entry then slips into plain hand: ‘Alas I had not forgotten. The heart has a memory of its own, but I had ceased to appear to remember save in occasional joking allusions to “the three steps”.’29 The odd humour relating to ‘the three steps’ suggests Lister’s need to deflect her extreme discomfort while remaining haunted by the incident. The three steps not only designate a reference to the coach, but also serve as an indicator of Lister having overstepped the mark. The tension between risk and control is outlined here, as is the difference between Lister’s reading of her wider social context and Mariana’s understanding of acceptable levels of intimacy and their public display. While the following coded entry of 20 August 1823 begins with Lister recording the resumption of sexual activity with her lover at Shibden Hall, the residual trauma is still in evidence. Mariana’s fear of potential exposure requires firm assurances from Lister, as she seeks to regain control of their narrative:

The fear of discovery is strong. It rather increases, I think, but her conscience seems seared as long as concealment is secure … Told her she need not fear my conduct letting out our secret. I could deceive anyone. Then told her how completely I had deceived Miss Pickford & that the success of such deceit almost smote me.30

Lister’s reference to deception here is clearly not self-deception, as she displays an acute understanding of her need for self-determination and control, and for the ways in which she is being forced back into a closet imposed by Mariana’s refusal of her oddity. As Lister poignantly and intriguingly reflects in long hand: ‘It was a coward love that dared not brave the storm &, in desperate despair, my proud, indignant spirit watched it sculk [sic] away.’31 While Mariana is happy to have sex with Anne, she feels no need to label herself as other or distinctive in the way that Lister does: Mariana is attached to behaviour rather than to identity; in other words she is closeted but not in the same strategic, self-conscious way that Lister is. The exchange between the two lovers foreshadows the difference between behaviour and identity fifty years before this paradigm shift that Foucault records as happening in the 1870s.32 Lister is both ahead of her time and of her time, dissident but also highly conservative.

In constructing her own crypt (hand), Lister knows where the threats are located and, as mentioned, where the bodies are buried. At the same time, she is aware of her own oddity and repeatedly ‘asserts the naturalness of her position’.33 One of the challenges for scholars working on the Lister diaries is the sheer scale of the entries, which provide an endless supply of variation but also, inevitably, an endless supply of contradictions. For example, the vexation noted above is undercut by instances of Lister’s diary persona brandishing her secret code as a seductive tool, or conversely as a weapon. As Rowanchild suggests, Lister is not above using her code as a means of flirtation when it suits her; on 7 January 1821, Lister writes that she gave a new love interest, Miss Vallance, ‘the crypt hand alphabet’.34 One of the diaries’ central enigmas concerns the choice of topics that Lister chooses to encrypt, which include financial matters, legal discussions, medical concerns, estate management and certain political issues, as well as sex and desire.35 Lister’s choice of coded ‘areas’ offers an apposite and eerie foreshadowing of the connections between sexuality and, increasingly, the pathologising institutional discourses discussed by Foucault in his History of Sexuality.36 Coded diary passages often alternate between descriptions of sexual activity and these broader social concerns. For example, diary transcripts for 1816 include coded mentions of kisses (orgasms) and coded passages discussing business and inheritance issues. On 15 August 1816, Lister writes in code: ‘L had a kiss’, and on 5 November she also records in code:

I advised my uncle to entail Shibden and at his death should my aunt Anne survive let her come into all as it stands for her life I said I wished him to prevent my aunt Lister or my mother having thirds and mentioned my fathers having once said/namely 3, July 1814/he would leave Marian and me joint heirs to which I objected as it might lead to the place being sold.37

There are also numerous mixed diary entries that combine plain hand and crypt hand and others which are coded but do not seem to relate directly to sex or business. For instance, the diary entry for 14 September 1814 mentions a gap in diary writing and the copying of previous notes (the whole entry was originally written in code): ‘Wrote out this part of my journal from notes after my return here from Lawton which accounts for the date of my getting this book, Saturday, the fourteenth of September one thousand eight hundred and sixteen.’38 This fully coded entry reads as an apology for lateness to the diary project itself and as a note on accountability. In this entry, the diary persona appears to role-play or to be rehearsing the role of professional author as a way of establishing a form of regular creative practice. Lister’s diary persona at times displays concerns regarding the temporal disjunction or gap between the original experience and its recording in diary form. New research presented by Jenna Beyer and Dannielle Orr at the recent Anne Lister Research Summit has also focused on issues raised by the diaries’ indexing and ordering.39 Lister’s reticence is understandable given the enduring social judgement levelled at female writers and ideas of ‘creative femininity’ in the early nineteenth century. As Gillian Paku suggests:

Some stigma also adhered to female writers, for whom writing did not fall within the usual sanctioned circle of female accomplishments at the start of the [nineteenth] century and in whose case the public articulation of texts could be portrayed as immodest and improper. Derisory terms such as ‘female quill-driver,’ ‘half man,’ or ‘scribbling Dame,’ persisted well into the nineteenth century.40

This may also partly explain the diaries’ lack of references to female writers, with the exception of Lady Caroline Lamb and her novel Glenarvon, which is discussed by Lister and Mariana.41 Upon its publication in 1816, the same year as Coleridge’s ‘Christabel’, Glenarvon caused a sensation as a transgressive novel, famously offering an early example of a cross-dressing character in a nineteenth-century novel. According to Bill Hughes: ‘Glenarvon was seen by critics as transgressing gender by its clashing of genres … genre and gender become confused like the “doubtful gender” of Lamb herself with her notorious cross-dressing.’42 The diary section pertaining to Glenarvon codes only the novel’s title, although its presence offers a pointed and painful reminder of discussions between Lister and Mariana earlier in the day concerning Lister’s masculine appearance and failure to pass as a feminine woman. As the entry notes, it is an example of a ‘scandalous’ text: ‘Agreed that Lady Caroline Lamb’s novel, Glenarvon, is a very talented but a very dangerous sort of book.’43 Lister’s reference to Glenarvon is both provocative and ironic.

While the desire to claim Lister as a dissident, queer icon for contemporary LGBTQIA readers and researchers is understandable, failure to acknowledge Lister as a product of her own time is also problematic. As Chris Roulston argues:

[T]here is a risk in seeing Lister as a figure who defied her historical moment rather than being defined by it. With the diaries’ groundbreaking status as a record of early lesbian sexuality, it is important to remember the degree to which Lister continued to reflect and embody the values of her social and economic class, particularly in terms of her unswerving Tory politics.44

Lister’s self-consciousness in the diaries is also double-edged; she displays, on the one hand, self-knowledge and awareness and, on the other, forms of social discomfort and non-belonging. Despite her sense of class superiority in her Halifax social circle, there are entries that express awkwardness and insecurity, as in this entry from 29 April 1832: ‘I felt, myself in reality gauche, and besides in false position. I have difficulty enough in the usage of high society and feeling unknown, but have ten times … I will eventually hide my head somewhere or other … The mortification of feeling my gaucherie is wholesome.’45

Diary Code as Split Paratext?

In Paratexts; Thresholds of Interpretation (1997), Gérard Genette suggests that ‘[m]ore than a boundary or a sealed border, the paratext is rather a threshold.’46 Genette uses the term to recognise framing devices employed by writers and publishers, such as indexes, dates and dedications. I want to argue that Lister’s diary crypt hand works equally as paratext and text. Discussions of paratexts and marginalia are still on the margins of the history of literary scholarship, perhaps in an ironically appropriate way. The critical terrain that exists between literary theory, and textual and autobiographical criticism is underexplored. Discussions of codes in life writing are still seen as niche, specialist or as an offshoot of corpus linguistics.47 There is a need for new conceptual life writing frameworks that would allow us to work with explicitly coded texts, Lister’s diaries being a prime example.

Lister’s code occupies an unusual position by being both inside and outside the text, as both cover and content. With the exception of additional cipher and loose-leaf pages which pre-date the start of the journal notebooks, there are no formal paratexts outside of code use in Lister’s diaries. At this point, it is helpful to consider other diaries that use code. Parts of Samuel Pepys’s diaries, written in the 1660s and first published in 1825, offer a similar use of code to cover explicit sexual content, albeit from a heteronormative perspective. The publication of the first decoded edition of Pepys’s diaries was within Lister’s lifetime. As with Lister’s diaries, Pepys’s diaries were hidden for a period of one hundred and fifty years, with the explicitly coded diary sections only deciphered in 1819.48 Given that, as far as we know, Lister started to develop a form of code from 1808 onwards, it is unlikely that she would have been influenced by knowledge of Pepys’s code use.49 Nor do Lister’s diaries contain any indexed reference to Pepys’s work. There are later examples of coded diaries by queer public figures, such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, but as someone who was highly ambivalent about his sexual identity, Wittgenstein’s use of code more likely designates a form of internalised homophobia.50

While the use of code in diaries produces a binary between the coded and the uncoded, the levels and layers within the written space are more nuanced and non-binary, providing an interlocking structure similar to Eve Sedgwick’s ‘mesh of queer possibilities’:

Queer is a continuing moment, movement, motive – recurrent, eddying, troublant … It is the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent element of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality are not made (or cannot be made to signify monolithically… Queer is relational. It is strange. To think, read, or act queerly is to think across boundaries, beyond what is deemed to be normal, to jump at the possibilities opened up by celebrating marginality, which in itself serves to destabilize the mainstream.51

It is the protection afforded by the code-cover that allows Lister to explore the wider parameters of her gender and sexuality and to reject contemporary socially closeted romantic friendship models. As Leonieke Vermeer argues, ‘[t]he study of disguising strategies in diaries can provide us with information on a subject for which source material is rare: bodily and sexual experiences.’52 Vermeer highlights one of the key contradictions in the work of coded diary writers, including Lister, in that ‘a code draws attention to the secrets it supposedly conceals’.53 In the process of code-covering, Lister tantalises potential readers and highlights taboo elements. While her code is an oxymoronic, obvious disguise, there are also elements within the diaries that offer other kinds of obscure writing or silences: missing dates, blank sections, crammed marginalia and, for the modern reader, illegible handwriting. Lister’s use of crypt hand and code produces a strange anomaly, in which the diary subject speaks both in, and through, the code-cover as a form of ventriloquism. It also gestures towards forms of historical biofiction, which focus on the expression and recovery of posthumous voices.54

Lister’s diary persona and voice are still being recovered through ongoing diary transcriptions. With the development of twenty-first-century computer software, large, historical diaries are now being made available on and in different platforms. These new resources are extremely helpful for researchers, but also have the effect of producing the journal in a multiplicity of sequences, patterns and datings, depending on areas of particular interest. The Lister diaries will continue to evolve through the completion of transcription and sequencing online; these diaries are still in the process of being written and remain unfixed and open to further interpretation.

The link between diary writing and psychological processing is often featured in studies of life writing. The volume of life writing produced by queer writers in the nineteenth century suggests a clear link between the processing of sexuality, gender and other consciously closeted states. Another example is Works and Days by the Michael Fields (Katherine Bradley and Edith Cooper), a diary covering the years 1888–1913, made up of multiple volumes still in the process of being transcribed.55 Works and Days offers another example of a multifunctional text that negotiates professional and personal terrain in relation to queer lives, intimacy and the question of identity.

It is useful here to make a distinction between code-cover and additional or accidental opacity. The relationship between historical diary writing and potential audiences (including chosen audiences and the author-as-audience) continues to provoke debate, as do discussions on diary writing as form/genre within potential life writing canons. Some researchers, such as Rebecca Hogan, argue that diaries are more subversive in their openness, as a ‘plurality of voices and perspectives’, and as ‘a form which preserves “otherness within the text” and within the self’.56 Conversely, many researchers stress that diary writing personas are as performative as fictional characters.

Lister’s diary shows her life writing persona trying on different hats, outfits, languages and alternative signifiers, with voices that refuse to accept easy labelling or classification. We cannot, of course, know the level of censorship that Lister imposed upon herself and her writing, and the extent to which topics and extremities of feeling were omitted or considered to be off-limits. Meta-commentaries on diary writing are unusual before the twentieth century and even rarer for unpublished life writing. Ironically, producers of diary notebooks, for example, Letts the stationer, founded in 1796, were keen to promote the idea of diaries as private or confessional works. In one advertisement, they instructed writers to ‘Use your diary with the utmost familiarity and confidence, conceal nothing from its pages nor suffer any other eye than your own to scan them.’57

Treating Lister as a life writer and placing her writing alongside other substantial diaries published in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries would undoubtedly shed further light on the connections between form and identity, as in, for example, those of John Evelyn (1640–1706, first published in 1818), Samuel Pepys (1660–9, first published in abridged form in 1825), and later nineteenth-century queer life writers such as the Michael Fields.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have shown the ways in which Lister’s diary code supports the negotiation of her self-conscious closet, as both shield and psychological comfort blanket. There are multiple references to comfort in the diaries as well as references to Lister’s robust code-cover, as in, for example: ‘What a comfort my journal is. How I can write in crypt all as it really is … and console myself.’58

I have reflected on existing conceptual frameworks and definitions of the closet derived from contemporary queer theory and proposed new readings based on the differences between self-conscious and unconscious closeted writing. There continue to be difficult questions concerning the links between explicitly coded texts and the closet, for example, when is a closet not a closet? As a diarist, Lister uses her code to combine competing elements of her diary persona into a form of paradoxical writing that both attracts and repels potential readership. The tension between code as cover and code as content would undoubtedly also benefit from readings provided by newer conceptual areas such as surface studies.59 Using the Lister diaries, I propose a case for the reclamation of ‘missing’ closets in queer women’s writing from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and to argue for their inclusion in interdisciplinary studies of psychological, social and physical spaces.