Schizophrenia is a devastating neuropsychiatric illness and a complex disease, and both genetic components and environmental factors play a role in its development. Reference van Os and Kapur1–Reference Leucht, Burkard, Henderson, Maj and Sartorius3 In general, around 1% of the total population is affected by schizophrenia. Reference Jones, Mowry, Pender and Greer4 However, despite a considerable number of studies, the aetiology of schizophrenia remains unclear. In addition, people with schizophrenia often develop somatic symptoms, particularly autoimmune disorders. Reference Jones, Mowry, Pender and Greer4 Previous studies have reported that, compared with the general population, individuals with schizophrenia have a different prevalence of some autoimmune diseases and experience different immunological responses, Reference Jones, Mowry, Pender and Greer4,Reference Strous and Shoenfeld5 which suggests that aberrant autoimmune responses may play a role in the aetiology of schizophrenia. Autoimmune involvement may account for the high rate of perinatal obstetric complications observed in people with schizophrenia and may have potential influence on central nervous system infection, which generates antibodies against the brain tissue in those with schizophrenia. Reference Kirch6,Reference Chengappa, Nimgaonkar, Bachert, Yang, Rabin and Ganguli7 In addition, a number of genetic studies have found that human leukocyte antigens were associated with schizophrenia; however, the results were inconsistent across different studies. Reference Li, Underhill, Liu, Sham, Donaldson and Murray8–Reference Palmer, Hsieh, Reed, Lonnqvist, Peltonen and Woodward10 Therefore, investigating the association between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia is particularly important to facilitate a dissection of the aetiology of schizophrenia.

To our knowledge, to date only Eaton et al has simultaneously examined a number of autoimmune diseases in relation to schizophrenia in a Danish population. Reference Eaton, Byrne, Ewald, Mors, Chen and Agerbo11 They used data from the Danish national registries from 1981 to 1988 to evaluate the association between schizophrenia and 29 autoimmune diseases. They found that a positive association existed between schizophrenia and a variety of autoimmune diseases, Reference Eaton, Byrne, Ewald, Mors, Chen and Agerbo11 and concluded that schizophrenia was associated with a larger variety of autoimmune diseases than was expected. Since then, no study has applied a similar approach to examine the association between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia, mainly due to the limited sample size in a single study. Few efforts have been directed to study this connection in Asian populations; only Chang et al has reported a connection between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia. Reference Chang, Chiang, Chiu, Tsai, Tsai and Huang12 In particular, they measured the messenger ribonucleic acid expression levels of a number of cytokines in the monocytes of people with schizophrenia. Although their findings demonstrated a suggestive increased autoimmunological response in participants with schizophrenia, the association between schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases has not yet been systematically investigated. To address this issue, we turned to the 2005 National Health Insurance data in Taiwan. First, we compared the prevalence of 34 autoimmune diseases in in-patients with schizophrenia with that of a control group of individuals without schizophrenia from the general population. Next, we examined the association between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia, and further explored possible gender variation in such connections.

Method

Study population

The data used in this study were obtained from Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) for 2005. The NHIRD is derived from the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP), which was launched in 1995. In detail, the NHIP provides mandatory comprehensive medical care services to residents of Taiwan. Since 1995, the NHIRD has collected the data of all ambulatory care and in-patient claims from NHIP enrolees, which represent over 98% of the total population in Taiwan. Reference Chen, Liu, Su, Huang and Lin13 Therefore, the NHIRD provides a valuable data source and a unique opportunity to undertake the objectives addressed in this study.

In-patients with schizophrenia were identified from the Psychiatric Inpatient Medical Claim Dataset (PIMCD) of the NHIRD from 2005. Specifically, participants with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 14 code: 295) Reference Chien, Hsu, Lin, Bih, Chou and Chou15 and having at least one claim for using the in-patient service for schizophrenia treatment in 2005 were included in the study. A total of 10 811 in-patients with schizophrenia (schizophrenia group) were identified in this data-set.

The comparison participants (control group) were identified from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID2005) of the NHIRD; they had no reports of any diagnosis of schizophrenia in 2005. In detail, the LHID2005 contains all the registration and claim data for 1 000 000 individuals, which were collected by the NHIP and randomly sampled from the 2005 Registry for Beneficiaries of the NHIRD. Detailed information on the sampling method representative of the LHID2005 is provided at: http://w3.nhri.org.tw/nhird/date_cohort.htm#1. In addition, participants in the control group were matched with participants in the schizophrenia group by age group (by 10-year interval) with a ratio of 1:10 and were randomly drawn from the LIHD2005. A total of 108 110 age-matched comparison participants were identified in this data-set.

Definition of autoimmune diseases

We determined the autoimmune diseases to be included in our analysis on the basis of ‘the list of catastrophic illnesses of rheumatology’ and those with autoimmune properties provided by the NHIP. Of note, this list represents the most serious auto-immune diseases with a heavy economic burden in Taiwan. As a result, a total of 34 autoimmune diseases were considered and identified based on their ICD-9-CM codes (see Appendix). For both the schizophrenia and control groups, medical records for any of the 34 autoimmune diseases were retrieved from the in-patient and ambulatory services in the NHIRD in 2005.

Statistical analyses

We first computed and compared the distribution of demographic characteristics between the schizophrenia group and the control group using the χ2 test, including age (<29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59 and 60 years); gender; region (northern, central, southern and eastern); urbanicity (urban, suburban and rural); enrolee category (a proxy measure of socioeconomic status); and information regarding health system utilisation such as number of hospital admissions in 2005 and length of hospital stay in 2005. Detailed information regarding enrolee category has been provided elsewhere. Reference Chen, Liu, Su, Huang and Lin16 Briefly, the insurance fee was determined based on enrolees’ wages as indicated in the NHIP. Participants were put into four enrolee categories, with wages of those in the first group (I) higher than those in subsequent categories (II–IV).

Next, we computed the prevalence rates for all examined autoimmune diseases among both the schizophrenia and control groups. Univariate and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed, separately, to evaluate the association between selected autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia. The covariates adjusted in the multiple conditional logistic regression models were gender, enrolee category and region. In addition, to examine the gender effect between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia, gender-stratified analysis was carried out, which included the covariates enrolee category and region. All of the analyses were performed using SAS version 8.2 for Windows. Furthermore, to control for potential false positive results due to multiple testing, we applied the false discovery rate (FDR) to correct for multiple testing. Reference Benjamini, Drai, Elmer, Kafkafi and Golani17 The FDR procedure was performed using statistical packages R 2.10.0 (www.r-project.org/) and Bioconductor 2.7 (www.bioconductor.org/), both run on Windows.

Results

Study sample characteristics

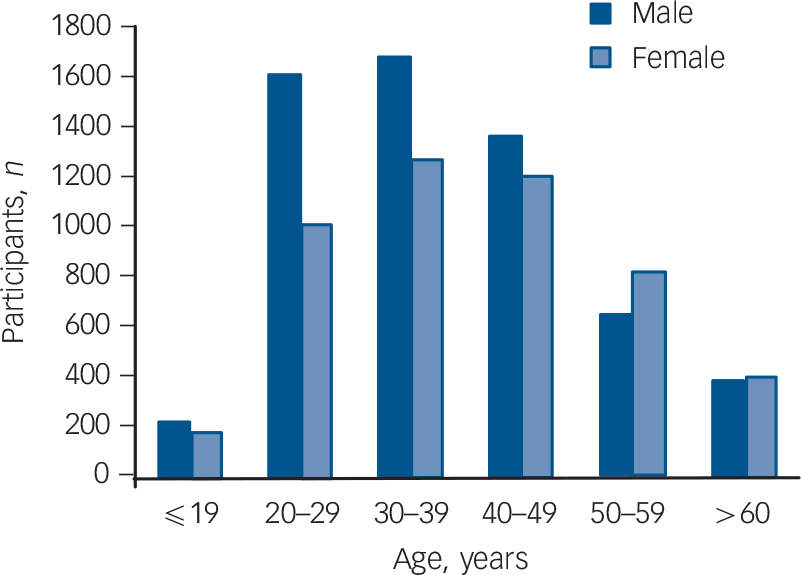

A total of 118 921 participants (10 811 in the schizophrenia group and 108 110 in the control group) were included in this study. Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic characteristics in both groups. In general, the distribution of gender, enrolee categories (a proxy measure of socioeconomic status), region, urbanicity, average number of hospital admissions in 2005 and length of hospital stay in 2005 are significantly different between the schizophrenia group and the control group. Compared with the control group there were a higher percentage of males among the schizophrenia group (54.9% v. 49.5%), a higher number of hospital admissions in 2005 (1.15 v. 0.10 times) and a longer hospital stay in 2005 (28.38 v. 0.44 days). The percentage of those in enrolee category IV was greater in the schizophrenia group than that in the control group (57.2% v. 15.4%). In other words, those in the schizophrenia group tended to have a lower socioeconomic status than those in the control group. Additionally, when we grouped the study sample by age, we found that the highest number of participants in the schizophrenia group were aged 30–39 years for both males and females (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1 Demographic characteristics of schizophrenia and control groups

| Variable | Schizophrenia group (n = 10 811) |

Control group (n = 108 110) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: % | 1.00 | ||

| <29 | 28.0 | 27.9 | |

| 30–39 | 27.3 | 27.3 | |

| 40–49 | 23.8 | 23.8 | |

| 50–59 | 13.7 | 13.7 | |

| >60 | 7.3 | 7.3 | |

| Gender, % | <0.0001 | ||

| Male | 54.9 | 49.5 | |

| Female | 45.1 | 50.5 | |

| Unknown | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Enrolee category, % | <0.0001 | ||

| I | 3.2 | 8.5 | |

| II | 14.0 | 43.5 | |

| III | 24.4 | 32.6 | |

| IV | 57.2 | 15.4 | |

| Unknown | 1.2 | 0.1 | |

| Region, % | <0.0001 | ||

| Northern | 44.6 | 51.3 | |

| Central | 19.1 | 18.0 | |

| Southern | 30.5 | 28.5 | |

| Eastern | 4.6 | 2.2 | |

| Unknown | 1.2 | 0.1 | |

| Urbanicity, % | <0.0001 | ||

| Urban | 23.1 | 31.9 | |

| Suburban | 61.4 | 57.9 | |

| Rural | 12.2 | 7.8 | |

| Unknown | 3.2 | 2.4 | |

| Health system utilisation, mean (s.d.) |

|||

| Hospital admissions in 2005, n | 1.15 (1.24) | 0.10 (0.48) | <0.0001 |

| Hospital stay in 2005, days | 28.38 (39.12) | 0.44 (3.03) | <0.0001 |

FIG. 1 Number of in-patients with schizophrenia across different age groups, stratified by gender.

Prevalence of autoimmune diseases

Next, we calculated and compared the annual prevalence of 34 autoimmune diseases among both groups in 2005 (Table 2 and online Table DS1). In the schizophrenia group, 14 out of 34 autoimmune diseases had a higher prevalence than that found in the control group (Table 2 and online Table DS1). When stratifying by gender, in the schizophrenia group the prevalence of 16 autoimmune diseases was higher in females than in males. Conversely, among the control group the prevalence of 21 autoimmune diseases was higher in females than in males (Table 2 and online Table DS1).

TABLE 2 Prevalence (per 1000) of autoimmune diseases (where total n ⩾ 5 in the schizophrenia group) among schizophrenia and control groups (stratified by gender)

| Schizophrenia group | Control group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune diseaseFootnote a |

Total (n = 10 811) |

Males (n = 5936) |

Females (n = 4875) |

Total (n = 108 110) |

Males (n = 52 513) |

Females (n = 55 597) |

||||||

| n | Prevalence | n | Prevalence | n | Prevalence | n | Prevalence | n | Prevalence | n | Prevalence | |

| Graves’ disease | 92 | 8.510 | 31 | 5.222 | 61 | 12.513 | 787 | 7.280 | 174 | 3.313 | 613 | 11.026 |

| Psoriasis | 56 | 5.180 | 37 | 6.233 | 19 | 3.897 | 311 | 2.877 | 184 | 3.504 | 127 | 2.284 |

| Type 1 diabetes | 31 | 2.867 | 12 | 2.022 | 19 | 3.897 | 175 | 1.619 | 92 | 1.752 | 83 | 1.493 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 30 | 2.775 | 12 | 2.022 | 18 | 3.692 | 507 | 4.690 | 164 | 3.123 | 343 | 6.169 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 29 | 2.682 | 17 | 2.864 | 12 | 2.462 | 400 | 3.700 | 219 | 4.170 | 181 | 3.256 |

| Sjögren syndrome | 24 | 2.220 | 11 | 1.853 | 13 | 2.667 | 312 | 2.886 | 81 | 1.542 | 231 | 4.155 |

| Pernicious anaemia | 22 | 2.035 | 9 | 1.516 | 13 | 2.667 | 107 | 0.990 | 26 | 0.495 | 81 | 1.457 |

| Hereditary haemolytic anaemia | 17 | 1.572 | 6 | 1.011 | 11 | 2.256 | 119 | 1.101 | 52 | 0.990 | 67 | 1.205 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 16 | 1.480 | 11 | 1.853 | 5 | 1.026 | 116 | 1.073 | 53 | 1.009 | 63 | 1.133 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 12 | 1.110 | 3 | 0.505 | 9 | 1.846 | 128 | 1.184 | 16 | 0.305 | 112 | 2.014 |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 10 | 0.925 | 4 | 0.674 | 6 | 1.231 | 48 | 0.444 | 17 | 0.324 | 31 | 0.558 |

| Celiac disease | 9 | 0.832 | 4 | 0.674 | 5 | 1.026 | 41 | 0.379 | 23 | 0.438 | 18 | 0.324 |

| Hypersensitivity vasculitis | 8 | 0.740 | 2 | 0.337 | 6 | 1.231 | 15 | 0.139 | 3 | 0.057 | 12 | 0.216 |

| Alopecia areata | 5 | 0.462 | 2 | 0.337 | 3 | 0.615 | 93 | 0.860 | 37 | 0.705 | 56 | 1.007 |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 5 | 0.462 | 1 | 0.168 | 4 | 0.821 | 70 | 0.647 | 23 | 0.438 | 47 | 0.845 |

| Dermatomyositis | 5 | 0.462 | 4 | 0.674 | 1 | 0.205 | 21 | 0.194 | 7 | 0.133 | 14 | 0.252 |

a. See Appendix for ICD-9-CM codes.

Association of autoimmune diseases with schizophrenia

For the 16 autoimmune diseases where the number of individuals with these conditions was ⩾5 in the schizophrenia group, we further examined the association between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia. In particular, when compared with the comparison group, participants in the schizophrenia group had a significantly higher risk of Graves’ disease (odds ratio (OR) = 1.32, 95% CI 1.04–1.67), psoriasis (OR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.07–2.04), pernicious anaemia (OR = 1.71, 95% CI 1.04–2.80), celiac disease (OR = 2.43, 95% CI 1.12–5.27) and hypersensitivity vasculitis (OR = 5.00, 95% CI 1.64–15.26); whereas a reverse association with rheumatoid arthritis (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.35–0.76) was observed (Table 3). Of note, the positive association between hypersensitivity vasculitis and schizophrenia remained significant after correcting for multiple testing. Likewise, the reverse association of rheumatoid arthritis with schizophrenia also remained significant after accounting for multiple corrections.

Gender effect of autoimmune diseases on schizophrenia

In addition, we performed a gender-stratified analysis to examine the gender effect (Table 3). We observed a gender-specific effect for Sjögren syndrome, hereditary haemolytic anaemia, myasthenia gravis, polymyalgia rheumatica and dermatomyositis, although none of these observed associations were statistically significant (Table 3).

Furthermore, Graves’ disease, psoriasis and dermatomyositis were significantly associated only with males in the schizophrenia group. Whereas, type 1 diabetes, hereditary haemolytic anaemia, celiac disease and hypersensitivity vasculitis were significantly associated only with females in the schizophrenia group, and in addition there was a significant inverse association of rheumatoid arthritis with females in this group. Among those autoimmune diseases found to be significantly associated with the schizophrenia group, only Graves’ disease in males and rheumatoid arthritis in females remained statistically significant after correction for multiple testing (Table 3).

TABLE 3 Association between autoimmune diseases (where total n ⩾5 in the schizophrenia group) and schizophrenia among the schizophrenia and control groups (stratified by gender)

| Total | Males | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune diseasesFootnote a | Adjusted ORFootnote b (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORFootnote c (95% CI) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORFootnote c (95% CI) |

| Graves’ disease | 1.32 Footnote d (1.04–1.67) | 1.59 Footnote d (1.08–2.34) | 1.86 Footnote e (1.22–2.84) | 1.12 (0.86–1.47) | 1.16 (0.87–1.54) |

| Psoriasis | 1.48 Footnote d (1.07–2.04) | 1.81 Footnote e (1.26–2.59) | 1.60 Footnote d (1.08–2.36) | 1.15 (0.86–2.44) | 1.26 (0.70–2.26) |

| Type 1 diabetes | 1.54 (0.99–2.37) | 1.46 (0.80–2.70) | 1.18 (0.62–2.25) | 2.39 Footnote e (1.39–4.11) | 1.98 Footnote d (1.11–3.54) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.52 Footnote e (0.35–0.76) | 0.66 (0.37–1.19) | 0.59 (0.32–1.08) | 0.59 Footnote d (0.36–0.94) | 0.48 Footnote e (0.30–0.79) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 0.71 (0.47–1.06) | 0.70 (0.43–1.15) | 0.71 (0.42–1.21) | 0.74 (0.41–1.33) | 0.71 (0.38–1.34) |

| Sjögren syndrome | 0.92 (0.59–1.41) | 1.23 (0.65–2.30) | 1.30 (0.82–3.14) | 0.63 (0.36–1.10) | 0.68 (0.38–1.20) |

| Pernicious anaemia | 1.71 Footnote d (1.04–2.80) | 3.13 Footnote e (1.46–6.67) | 1.91 (0.84–4.35) | 1.80 Footnote d (1.00–3.23) | 1.57 (0.84–2.93) |

| Hereditary haemolytic anaemia | 1.45 (0.84–2.50) | 1.04 (0.45–2.43) | 0.95 (0.39–2.35) | 1.84 (0.97–3.48) | 1.99 Footnote d (1.00–3.93) |

| Myasthenia gravis | 1.18 (0.67–2.09) | 1.87 (0.98–3.59) | 1.42 (0.69–2.92) | 0.89 (0.36–2.21) | 0.86 (0.34–2.23) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1.22 (0.66–2.27) | 1.69 (0.49–5.81) | 2.78 (0.76–10.12) | 0.90 (0.46–1.78) | 1.02 (0.50–2.07) |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 2.04 (0.95–4.39) | 2.12 (0.72–6.31) | 1.91 (0.50–7.22) | 2.17 (0.90–5.20) | 2.19 (0.86–5.58) |

| Celiac disease | 2.43 Footnote d (1.12–5.27) | 1.57 (0.54–4.54) | 1.51 (0.49–4.66) | 3.12 Footnote d (1.16–8.39) | 4.10 Footnote d (1.42–11.78) |

| Hypersensitivity vasculitis | 5.00 Footnote e (1.64–15.26) | 4.51 (0.41–49.75) | 5.65 (0.51–62.41) | 4.48 Footnote d (1.41–14.29) | 4.69 Footnote d (1.34–16.45) |

| Alopecia areata | 0.72 (0.29–1.83) | 0.49 (0.12–2.02) | 0.65 (0.15–2.82) | 0.60 (0.19–1.92) | 0.78 (0.24–2.57) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 0.77 (0.30–1.98) | 0.39 (0.05–2.90) | 0.39 (0.05–3.03) | 0.95 (0.34–2.65) | 1.02 (0.35–2.95) |

| Dermatomyositis | 2.55 (0.88–7.39) | 5.16 Footnote d (1.51–17.62) | 5.11 Footnote d (1.25–20.93) | 0.80 (0.11–6.08) | 0.93 (0.11–7.62) |

a. See Appendix for ICD-9-CM codes.

b. Adjusted for gender, enrolee category and region.

c. Adjusted for enrolee category and region.

d. Significant results. P: 0.007<P raw<0.05.

e. P: significant after false discovery rate (FDR) correction (P raw = 0.007 is equal to P FDR = 0.05 in this study).

Discussion

In general, schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases share many common clinical features. First, the diagnostic procedures are largely dependent on clinical criteria such as lacking a specific aetiological diagnosis. Second, the treatments are usually palliative, not curative. Third, schizophrenia and most autoimmune diseases have unequal distributions of incidence for age, gender, cultures and across different ethnic groups. Reference Messias, Chen and Eaton18,Reference Youinou, Pers, Gershwin and Shoenfeld19 However, schizophrenia is more prevalent among males, whereas most of the autoimmune diseases disproportionally affect females. Finally, both are complex disorders; that is, disorders that are caused by multiple genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors and the interaction between these factors, and they do not follow a clear Mendelian pattern of inheritance. Furthermore, due to limited knowledge of pathophysiology, individuals with schizophrenia and/or certain autoimmune diseases might be similar in clinical presentation, but their underlying aetiologies are very heterogeneous. Therefore, using large medical databases to identify whether certain autoimmune diseases co-occur with schizophrenia more or less commonly than expected by chance should provide an insight into the possible shared genetic, immunological and environmental mechanisms of both disorders. To our knowledge, this is the first study using a national database to address the association between schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases in an Asian population. More importantly, our data indicated that a certain number of auto-immune diseases were significantly associated (either positively or negatively) with in-patients with schizophrenia.

Significant association between autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia

Overall, a significant increased risk for Graves’ disease, psoriasis, pernicious anaemia, celiac disease and hypersensitivity vasculitis were found in the schizophrenia group, whereas a significant reverse association was observed between rheumatoid arthritis and this group. Several studies have reported the association of Graves’ disease and rheumatoid arthritis with schizophrenia, respectively, which we discuss below.

Graves’ disease, also known as thyrotoxicosis, is an auto-immune disease that affects up to 2% of the female population, and has a female-to-male incidence ratio ranging from 5:1 to 10:1. Reference Manji, Carr-Smith, Boelaert, Allahabadia, Armitage and Chatterjee20,Reference Weetman21 In agreement with previous studies, Reference Eaton, Byrne, Ewald, Mors, Chen and Agerbo11,Reference Othman, Abdul Kadir, Hassan, Hong, Singh and Raman22,Reference Wright, Sham, Gilvarry, Jones, Cannon and Sharma23 our present study revealed that participants with schizophrenia had a higher prevalence of Graves’ disease than did those in the comparison group. In addition, thyroid hormone dysfunction per se can result in cognitive function impairment, and emotional and behavioural disturbance. Therefore, further investigation of the autoimmune process of Graves’ disease in individuals with schizophrenia is warranted.

The inverse relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and schizophrenia observed in our study is generally consistent with previous findings in the area of autoimmune diseases. Reference Leucht, Burkard, Henderson, Maj and Sartorius3,Reference Eaton, Hayward and Ram24–Reference Oken and Schulzer26 It has been proposed that this relationship may be attributed to the interplay of genetic influence (hitch-hiking of major histocompatibility complex genes), environmental factors (institutionalisation and sedentary lifestyle due to negative symptoms), immunological aspects (common infectious aetiology and immunity) and pharmacological effects (anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of antipsychotics). Reference Torrey and Yolken27 Specifically, rheumatoid arthritis is a progressive, systemic inflammatory disorder that may affect many tissues and organs, but mainly attacks synovial joints. The peak onset of rheumatoid arthritis occurs between the fourth to sixth decade of life, and women are two to five times more likely than men to develop this disease. Reference Scott, Wolfe and Huizinga28 Of interest, as shown in Table 3, we observed a significant inverse association of rheumatoid arthritis with females in the schizophrenia group. It will be of importance in future studies to dissect the relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and schizophrenia to gain a better understanding of the interplay of the four components listed above.

TABLE 4 Comparison of the prevalence (per 1000) of autoimmune diseases in the general population in Taiwan and that in Asian populations

| Autoimmune disease | Country of

study population |

Prevalence in

general population in our study |

Prevalence in

the compared study |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graves’ disease | China | 7.3 | 12 | Shapira et al Reference Shapira, Agmon-Levin and Shoenfeld 29 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | China | 4.7 | 2–9.3 | Zeng et al Reference Zeng, Chen, Darmawan, Xiao, Chen and Wigley 30 |

| Psoriasis | Japan | 2.9 | 2.4–11.8 | Raychaudhuri et al Reference Raychaudhuri and Farber 31 |

| Pernicious anaemia | China | 1.0 | 1.3 | Chan et al Reference Chan, Liu, Kho, Lau, Li and Chan 32 |

| Celiac disease | India | 0.4 | 0.2–2 | Cummins & Roberts-ThomsonReference Cummins and Roberts-Thomson 33 |

| Hypersensitivity vasculitis | India | 0.1 | 0.03–0.1 | WattsReference Watts 34 |

Comparison of autoimmune disease prevalence found in the present study and Asian populations

We compared the prevalence of the 34 autoimmune diseases we had investigated in the general population in Taiwan to that reported in Asian populations. The data in Table 4 show the comparisons between the prevalence of the six significant auto-immune diseases observed in Table 3 and the prevalence of these reported in Asian populations. We found that the prevalence of these six conditions was comparable with that reported by other groups (Table 4).

Genetic influences on schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases

Recent genome-wide association studies have identified a growing number of disease-associated loci and provided enormous insight into the aetiology of complex genetic disorders, including schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases. For example, using molecular pathway-based analysis, genome-wide association studies of schizophrenia revealed a number of genes involved in neuronal cell adhesion, membrane scaffolding, apoptosis, glutamate metabolism or synaptogenesis. Reference Jia, Wang, Meltzer and Zhao35,Reference O'Dushlaine, Kenny, Heron, Donohoe, Gill and Morris36 Meanwhile, genome-wide association studies of autoimmune diseases have highlighted immune-associated genes involved in lymphocyte activation (receptor signalling and co-stimulation pathways), microbial recognition and cytokines or cytokine receptors. Reference Gregersen and Olsson37 Strikingly, consistent with the results from previous linkage and case–control association studies, genome-wide association study results confirmed a shared genetic association in the major histocompatibility complex (also known as human leukocyte antigen) region between schizophrenia and most autoimmune diseases. Reference Shi, Levinson, Duan, Sanders, Zheng and Pe'er38,Reference Zenewicz, Abraham, Flavell and Cho39 The unique coding and non-coding genetic variation of human leukocyte antigen alleles are involved in shaping the nature of antigen responses to self- or non-self-antigens. Moreover, extensive allelic variation and linkage disequilibrium (non-random or correlated association of alleles due to physical closeness) have been observed throughout the major histocompatibility complex region. Reference Trowsdale40 Therefore, this shared gene region of association may influence direct involvement of certain human leukocyte antigens, or it may be through linkage disequilibrium between the loci related to schizophrenia and those related to autoimmune diseases in human leukocyte antigen regions. Genotyping more dense single-nucleotide polymorphisms or deep sequencing human leukocyte antigen regions may shed more light on the nature of the common shared genetic components of schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, the NHIP in Taiwan is a single-payer compulsory social insurance plan that centralises the disbursement of healthcare funds. The system promises equal access to healthcare for all citizens, and it covers nearly all clinical activities in Taiwan. More importantly, as mentioned earlier, the NHIP covers over 98% of the total population in Taiwan. Second, unlike several national registry databases that exist in European countries such as Iceland, Finland and Denmark, NHIRD in Taiwan is the only national database that exists among Asian countries. Third, the sample size in this study is sufficient since it is based on the NHIRD data (i.e. on national data). Since autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia are both considered rare diseases, a large sample size makes it feasible to investigate the relationship between them.

However, some limitations should also be considered. First, the NHIRD did not collect laboratory data to validate the physician diagnosis or the severity of autoimmune diseases. However, most autoimmune diseases examined in this study were selected based on the list of catastrophic illness of rheumatology provided by the NHIP. Based on standard clinical guidance for the list of catastrophic illnesses in the NHIP, it requires three board-certified rheumatologists to independently diagnose individuals with the explicit ICD-9-CM code for the autoimmune diseases on the list of catastrophic illnesses. As such, the diagnosis of autoimmune diseases was relatively reliable. Second, due to the nature of the cross-sectional design, this study cannot investigate temporal/causal relationships between autoimmune disorders and schizophrenia, but can only document the prevalence and association between schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases. Indeed, the observed excess in autoimmune diseases associated with schizophrenia may be partly explained by non-aetiological causational mechanisms. For example, because of the long course of treatment, people with schizophrenia were more likely to be treated as compared with individuals in the community without schizophrenia. It will be of importance to further investigate the causal relationship between schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases using a prospective cohort. Finally, this is the first study of its kind to be conducted in an Asian population. Therefore, the results observed in this study may or may not be generalised to other ethnic groups, and caution is needed when interpreting the results of this study.

Further research

In the present study, we documented that in an Asian population schizophrenia was associated with a wider variety of autoimmune diseases than was expected. The findings of comorbidity suggest that shared genetic components and shared aetiological pathways may occur in autoimmune diseases and schizophrenia. Further investigation of the interplay between genetic, immune and pathological mechanisms will provide a better understanding of the underlying aetiology of both schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases.

Appendix

Autoimmune disease included in analysis with ICD-9-CM codes

Graves’ disease (242, 242.01), Crohn's disease (555.0, 555.1, 555.2, 555.9), psoriasis (696, 696.1, 696.8), systemic lupus erythematosus (710.0), rheumatoid arthritis (714), ankylosing spondylitis (720), Guillain–Barré syndrome (357.0), type 1 diabetes (250.01, 250.03, 250.11, 250.13, 250.21, 250.23, 250.31, 250.33, 250.41, 250.43, 250.51, 250.53, 250.61, 250.63, 250.71, 250.73, 250.81, 250.83, 250.91, 250.93), Sjögren syndrome (710.2), myasthenia gravis (358), pernicious anaemia (281), hereditary haemolytic anaemia (282), polyarteritis nodosa (446), celiac disease (579), uveitis (364.00, 364.01), polymyalgia rheumatica (725), dermatomyositis (710.3), Hashimoto's thyroiditis (245.2), hypersensitivity vasculitis (446.2, 446.29), Behcet's disease (136.1), polymyositis (710.4), alopecia areata (704.01), Wegener's granulomatosis (446.4), ulcerative colitis (556.0, 556.6, 556.8, 556.9), autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (283), pemphigus (694.4), multiple sclerosis (340), systemic sclerosis (710.1), juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (714.30, 714.33), Goodpasture syndrome (446.21), giant cell arteritis (446.5), thromboangitis obliterans (443.1), arteritis obliterans (446.7) and Kawasaki disease (446.1).

Funding

This study was supported in part by grants from the National Health Research Institutes (, ).

Acknowledgements

Our thank to Drs Kuan-Yi Wu and Hsin-Yi Liang for their comments on the manuscript, Lan-Chao Wang for his assistance with data management and Tami R. Bartell for English editing. This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health and managed by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.