Treatment-resistant schizophrenia

Schizophrenia has a lifetime morbid prevalence of 7 per 1000 people.Reference Saha, Chant, Welham and McGrath1 Although antipsychotic medication is the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia, not all patients respond to first-line antipsychotic treatment.Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, De Bartolomeis, Van Beveren and Birnbaum2 These cases of treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) are associated with high levels of functional impairment,Reference Iasevoli, Giordano, Balletta, Latte, Formato and Prinzivalli3 healthcare usage, societal costsReference Kennedy, Altar, Taylor, Degtiar and Hornberger4 and physical health comorbidity.Reference Firth, Siddiqi, Koyanagi, Siskind, Rosenbaum and Galletly5

In response, a consensus definition of TRS has been developed by the Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group. These include the following: (a) current symptoms of at least moderate severity and moderate or worse functional impairment; and (b) prior treatment with at least two different antipsychotics, each for at least 4–6 weeks minimum duration at total daily dose equivalent of at least 600 mg chlorpromazine.Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, De Bartolomeis, Van Beveren and Birnbaum2

Clozapine and treatment-resistant schizophrenia

The most effective medication for TRS is clozapine, with improvement in positive symptoms,Reference Siskind, McCartney, Goldschlager and Kisely6 hospital admissionsReference Land, Siskind, Mcardle, Kisely, Winckel and Hollingworth7 and overall mortality.Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan8 In most jurisdictions, clozapine use in schizophrenia is limited to patients who have had two failed trials of first-line antipsychotics.Reference Bachmann, Aagaard, Bernardo, Brandt, Cartabia and Clavenna9–Reference Lehman, Lieberman, Dixon, McGlashan, Miller and Perkins11 As such, use of clozapine is sometimes regarded as a marker of TRS.

Quantifying treatment-resistant schizophrenia

Despite the increasing attention on providing treatment and psychosocial support for people with TRS,Reference Hasan, Falkai, Wobrock, Lieberman, Glenthoj and Gattaz12 there remains a lack of clarity as to the proportion of people with schizophrenia who are treatment resistant. Given low levels of clozapine prescribing in some jurisdictions,Reference Bachmann, Aagaard, Bernardo, Brandt, Cartabia and Clavenna9 quantifying the rates of patients with TRS could highlight the need to improve access to clozapine,Reference Verdoux, Quiles, Bachmann and Siskind13 and increase opportunities of a clozapine trial for patients with TRS. Cross-sectional studies examining the proportion of patients with TRS may overestimate the true rate because of selection bias.Reference Siskind, Harris, Phillipou, Morgan, Waterreus and Galletly14 By contrast, longitudinal first-episode cohort studies may more accurately quantify the incidence of patients with TRS, and better inform healthcare service resourcing. However, first-episode cohort studies from single sites may not be generalisable, and as such need to be combined with first-episode cohorts from multiple sites.

We therefore systematically reviewed the literature to quantify the proportion of people with TRS given the recent improvements in the clarity of definition. We searched for longitudinal cohort studies of people with first-episode psychosis (FEP), and identified what proportion met criteria for TRS at follow-up. We then undertook a meta-analysis to quantify rates of TRS.

Method

Design

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews (registration number: CRD42019140958). We followed guidelines for the reporting of meta-analyses of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE),Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie15 which comprised background, search strategy, methods, results, discussion and conclusions and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-AnalysesReference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group16 (Supplementary Table 7 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.61).

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from inception to the date of data extraction (13 December 2020), using the following terms: schizophrenia, psychosis, psychotic disorder, refractory, refractoriness, treatment resistant, treatment resistance, clinical remission, symptomatic remission, clinical response, clozapine, first, age at onset. The full PubMed search strategy is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Key researchers were contacted regarding unpublished data-sets.

The studies identified through the electronic search were then reviewed at abstract and title level by two authors (B.B. and O.Y.). These titles were then reviewed at full-text level by two of four authors (S.O., S.S., B.B. and O.Y.). The results of the full-text search were verified by a third member of the research team (D.S.), and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the entire review team. Reference lists were hand-searched to identify any potential additional articles.

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the systematic review and subsequent meta-analyses, studies were required to meet the following criteria: (a) cohort studies of individuals with FEP or first-episode schizophrenia (FES) who were diagnosed according to DSM-IV, DSM-5 or ICD-10 classifications; (b) the presence of a clear definition of treatment resistance consistent with the TRRIP Working Group's standardised definitionReference Howes, McCutcheon, Agid, De Bartolomeis, Van Beveren and Birnbaum2; (c) the presence of longitudinal information on pharmacological interventions; (d) reports on the proportion of the FEP/FES population who were followed up prospectively and went on to develop a treatment-resistant form of the illness and (e) the study had a follow-up period of at least 8 weeks.

Papers were excluded if there was >75% overlap of the included data-sets with another paper. Where multiple papers had >75% overlap of data-sets, the paper that had the TRS definition that was most aligned with the TRRIP guidelines was selected; papers with longer duration of the cohort follow-up and papers using the largest subsample of the cohort were used preferentially.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if the study population had already been exposed to previous antipsychotic treatment before entry into the cohort, and if substance-induced psychosis could not be excluded at time of follow-up. Study designs that did not specifically capture all sequential first-episode patients, such as cross-sectional or randomised controlled trials, were excluded as it could not be ascertained if the criteria for participation in these studies constituted a selection bias.

Data extraction

Two authors (B.B. and O.Y.) independently extracted data, which was validated by another two authors (S.O. and S.S.) from the research team. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of the original cohort with TRS diagnosis at follow-up. If data on multiple TRS definitions were provided within the same study, the data for the TRS definition that was most aligned with the TRRIP guidelines was used. We extracted the following data: total sample size at baseline; total sample size at follow-up; number of individuals with TRS at follow-up; percentage of individuals who dropped out or were lost to duration of follow-up, in months; years in which the majority of the study data was collected (grouped to before/after the year 2000); country in which the study was conducted; alignment of TRS definition with TRRIP guidelines; mean age of the cohort; proportion of men in the cohort; whether the cohort was from an in-patient or community setting; whether data collection was prospective or retrospective and whether there was involuntary mental health treatment during the study.

Study quality

We used a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale to assess the quality of included non-randomised studies (Supplementary Table 4). The scale assesses the quality in several domains, including sample representativeness and size, loss to follow-up and ascertainment of diagnosis of schizophrenia. The quality of descriptive statistics, which included reporting of population demographics (e.g. age and gender) and measures of dispersion (e.g. s.d., s.e. and range), were also assessed. Studies were assessed as low risk of bias and high strength of reporting (three or more points), or high risk of bias and low strength of reporting (fewer than three points).

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the event rate, defined as number of people diagnosed with TRS among all individuals at follow-up. Meta-analyses were conducted with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3.3 for Windows, Biostat Inc, USA, www.meta-analysis.com). Given the observational nature of primary studies and expected high rates of heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used for all the analyses.

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis and meta-regression

Subgroup analyses were undertaken on location of recruitment (community, in-patient or both), definition of TRS, diagnostic criteria (FEP versus FES), study quality, time period of the majority of data collection (dichotomised as before versus after the year 2000, corresponding to the publication of the DSM-IV-TR17) and study design (retrospective versus prospective cohort study). Studies with overlapping data-sets were selectively excluded to assess the effect on overall results. Comparisons of subgroup heterogeneity were undertaken with mixed-effects analysis.Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein18 Sensitivity analysis was undertaken to study the effect of only including studies of higher quality, and conduct a meta-regression of the effect of covariates, including duration of follow-up and percentage drop-out.

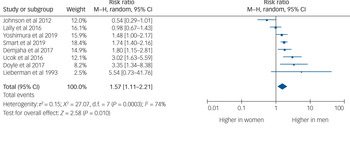

The risk ratio of rates of TRS between men and women was calculated with a random-effects meta-analysis, using RevMan (version 5.3.5 for Mac, The Cochrane Collaboration, UK, www.cochrane.org/).

Publication bias

We explored publication bias by using funnel plot asymmetry testing for statistical significance with both Kendall's τ and Egger's regression (where low P-values suggest publication bias), when meta-analyses included ten or more studies.Reference Barendregt and Doi19

Results

Study selection

We identified 8273 unique articles in the search of databases. We excluded 8061 at title and abstract level. A total of 212 articles were reviewed at full-text level, with 12 studies meeting the criteria for inclusion,Reference Agid, Arenovich, Sajeev, Zipursky, Kapur and Foussias20–Reference Yoshimura, Sakamoto, Sato, Takaki and Yamada31 of which one was an unpublished data-set.Reference Smart, Agbedjro, Consortium, Pardinas, Walters and Stahl28 No additional studies were identified through hand-searching. (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 6)

Study characteristics

The studies were from Canada (n = 2), Denmark (n = 1), England (n = 2), Japan (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), India (n = 1), USA (n = 1) and Ireland (n = 1); two studies had multiple international locations (Table 1).

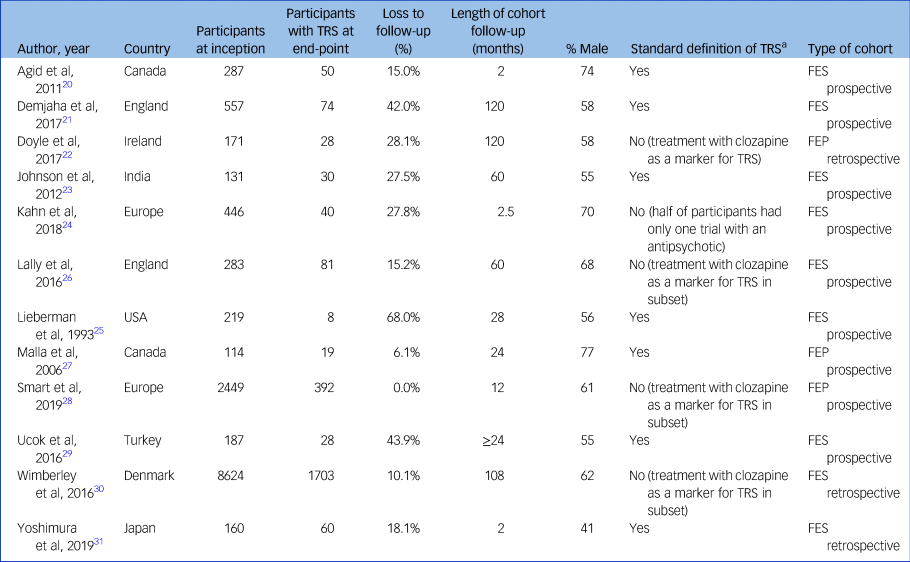

Table 1 Details of included studies

TRS, treatment-resistant schizophrenia; FES, first-episode schizophrenia; FEP, first-episode psychosis.

a. Two trials of antipsychotics at adequate dose and duration, aligned to Treatment Response and Resistance In Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group.

These studies covered a total of 11 958 individuals. Sample size ranged from 70 to 7749 participants. The proportion of male study participants was 61.9% (s.d. 10.4%). Median duration of follow-up was 26 months (range 2–120 months). Two studies recruited from community sites, two from in-patient units and eight from a combination of community and in-patient sites. Nine studies undertook the majority of data collection after the year 2000.

Nine cohorts comprised participants with FES and three cohorts comprised participants with FEP. Definitions of TRS were relatively homogeneous, with nine studies using criteria aligned with the TRRIP guidelines. Nine studies used prospective data collection, with the other three being collected retrospectively. Only two studies provided data on involuntary treatment status,Reference Demjaha, Lappin, Stahl, Patel, MacCabe and Howes21,Reference Yoshimura, Sakamoto, Sato, Takaki and Yamada31 precluding meaningful sensitivity analysis on this variable.

Risk of bias within studies

Six studies were rated as being of high quality (Supplementary Table 5). The main concern regarding study quality was the relatively high drop-out rate (mean 24.2%, s.d. 19.1%).

Synthesis of results

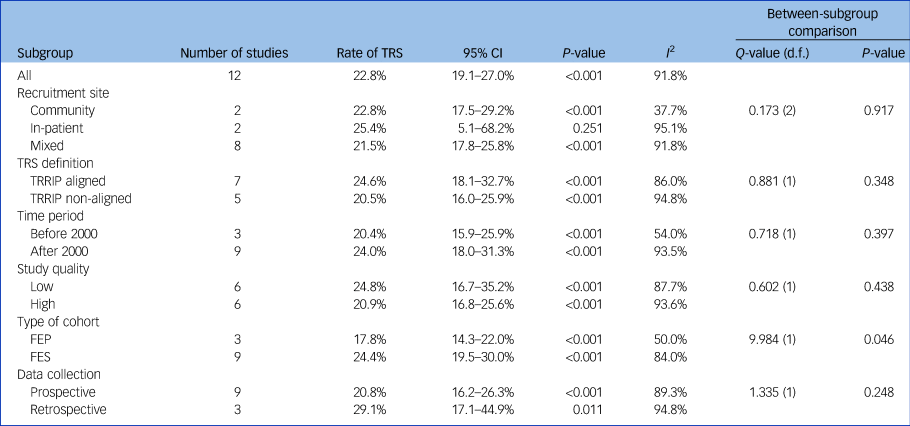

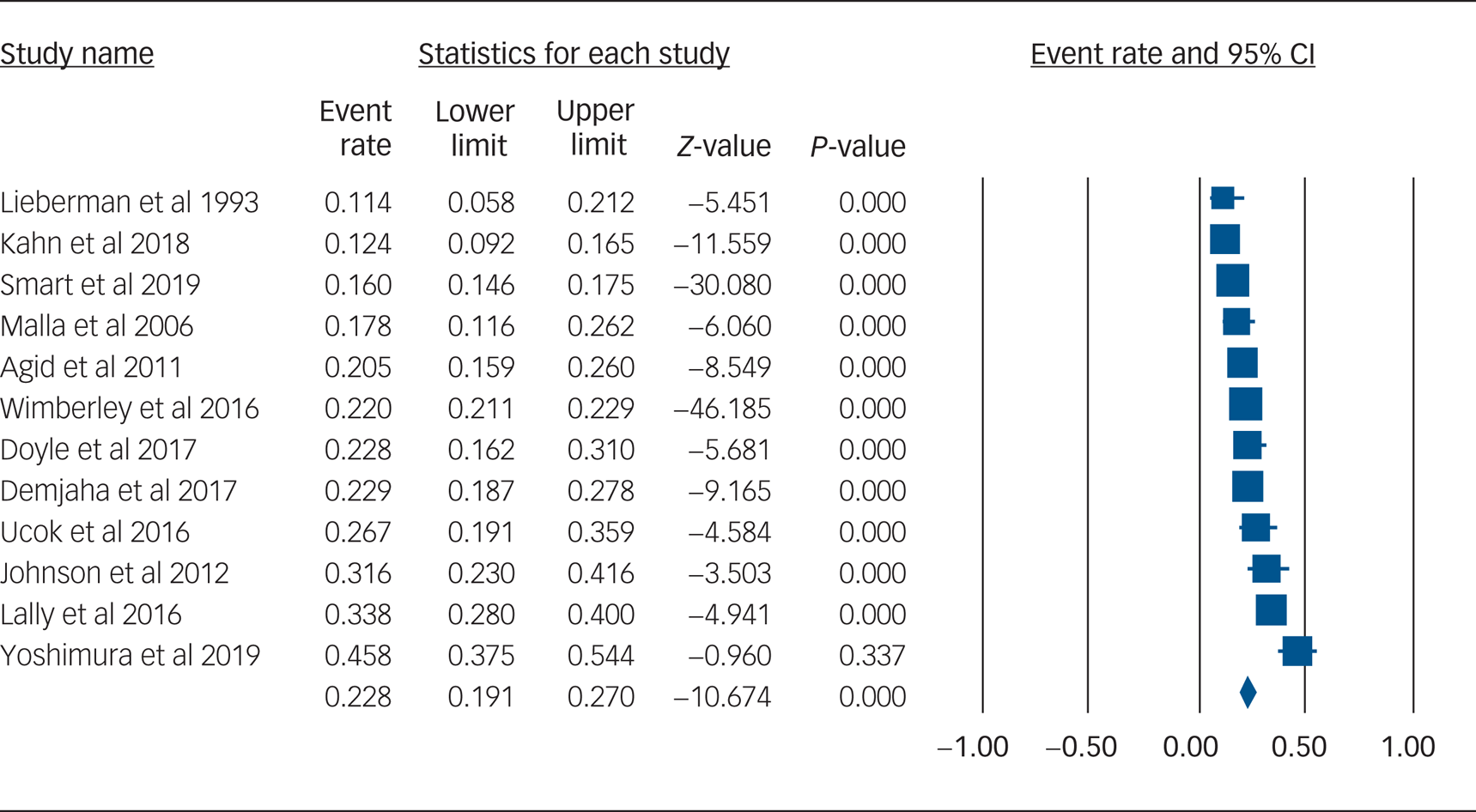

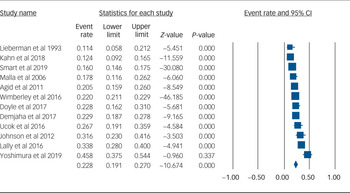

Using data from 12 studies, the overall rate of TRS was 22.8% (95% CI 19.1–27.0%, P < 0.001, I 2 = 91.8%) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The rates of TRS were significantly lower in FEP cohorts compared with FES cohorts (17.8% v. 24.4%, P = 0.046) (Table 2).

Table 2 Rates of treatment-resistant schizophrenia

TRS, treatment-resistant schizophrenia; TRRIP, Treatment Response and Resistance In Psychosis Working Group guidelines; FEP, first-episode psychosis; FES, first-episode schizophrenia.

Fig. 1 Forest plot of treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

There was no statistically significant difference in subgroup heterogeneity for recruitment location, TRS definition, time period of recruitment, study quality or prospective versus retrospective data collection (Table 2).

Meta-regression by duration of follow-up and percentage drop-out did not statistically significantly affect the overall result (Supplementary Table 2).

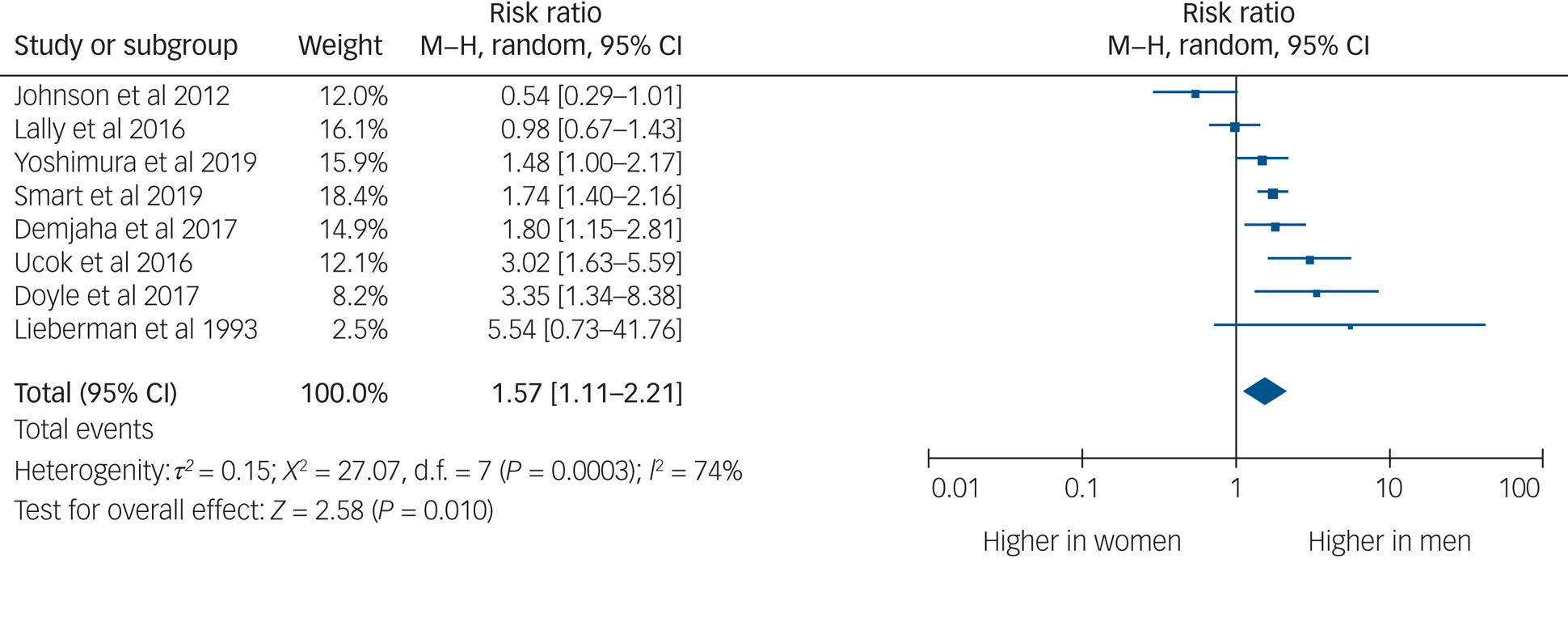

Eight studies provided usable data to compare rates of TRS between men and women. Men were 1.57 times more likely to develop TRS than women (95% CI 1.11–2.21, P = 0.010, I 2 = 74%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Rates of treatment-resistant schizophrenia by gender.

Risk of bias across studies

There was no evidence of significant risk of publication bias with Kendall's τ or Egger's regression (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This study is the first to quantify rates of TRS from first-episode cohorts by using meta-analysis. We found that the rate of TRS was 22.8%, rising to 24.4% when only FES cohorts were included. The higher rate of TRS among FES versus FEP cohorts is not unexpected, as TRS requires a diagnosis of schizophrenia, whereas FEP cohorts included participants with diagnoses other than schizophrenia. Differences in definition of TRS did not affect the overall rate of TRS.

Men were one and a half times as likely as women to develop TRS. This is in keeping with previous findings that men are one and a half times more likely to develop schizophrenia than women.Reference Aleman, Kahn and Selten32 There is a gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia, with men being diagnosed at a younger age.Reference Sommer, Tiihonen, van Mourik, Tanskanen and Taipale33

The findings of this study may underestimate the true level of clinically relevant treatment resistance. Although the majority of those with TRS demonstrate resistance from onset of illness, between 16 and 30% have been shown to develop treatment resistance at a later stage of illness, following an initial period of treatment response.Reference Demjaha, Lappin, Stahl, Patel, MacCabe and Howes21,Reference Lally, Ajnakina, Di Forti, Trotta, Demjaha and Kolliakou26 This has been shown to occur on average 5 years following illness onset,Reference Demjaha, Lappin, Stahl, Patel, MacCabe and Howes21 and thus may have been underreported by the two thirds of studies that had periods of follow-up that were <5 years. Additionally, the TRIPP definition of TRS may not account for those who initially respond to antipsychotic treatment, but go on to develop psychosis relapse despite ongoing maintenance antipsychotic treatment.Reference Rubio and Kane34 Studies have shown that around 20–30% of those prescribed long-acting injectable antipsychotics will develop a later treatment resistance following an initial symptom resolution.Reference Emsley, Asmal, Rubio, Correll and Kane35–Reference Rubio, Taipale, Correll, Tanskanen, Kane and Tiihonen37 There is emerging evidence that patients with breakthrough psychosis symptoms despite antipsychotic maintenance medication share a similar pathology to those with TRS, and clinically will require similar management options such as clozapine consideration.Reference Rubio and Kane34 Given the studies included in this analysis were first-episode cohorts, the true rate of TRS may be as high as one in three in longer-term patients.

These findings highlight the need for ongoing monitoring of psychotic symptoms and psychosocial functioning among people with FEP. Early identification of people with FES who fail to respond to first or second antipsychotic trials can assist in timely provision of evidence-based treatments for TRS such as clozapine.Reference Siskind, McCartney, Goldschlager and Kisely6,Reference Land, Siskind, Mcardle, Kisely, Winckel and Hollingworth7

Although clozapine remains the most effective and efficacious medication for TRS, access to clozapine remains poor, ranging from between a fifth to half.Reference Bachmann, Aagaard, Bernardo, Brandt, Cartabia and Clavenna9 Barriers include a lack of experience among prescribers and the absence of specialised clozapine clinics.Reference Verdoux, Quiles, Bachmann and Siskind13 The high rates of TRS in our study suggest the need to improve access to clozapine in this population.

Pharmacological interventions for TRS form only one part of the treatment strategy. Multidisciplinary interventions such as cognitive–behavioural therapy,Reference Todorovic, Lal, Dark, De Monte, Kisely and Siskind38 and psychosocial interventions such as personalised support delivered by support workers,Reference Siskind, Harris, Pirkis and Whiteford39 and supported accommodationReference Siskind, Harris, Pirkis and Whiteford40 are also needed. People with TRS have an increased risk of physical health comorbidity, which should be addressed through lifestyle interventions, including diet, exercise and improved access to primary and tertiary healthcare services.Reference Firth, Siddiqi, Koyanagi, Siskind, Rosenbaum and Galletly5

Our study had several limitations. There were high rates of drop-out in the cohort studies included in our meta-analysis, and it is unclear whether those who dropped out of the included cohorts were more or less likely to develop TRS. This may mean that we may have over- or underestimated the true rate of TRS. Reassuringly, when we undertook meta-regression by percentage drop-out in the included studies, there was no statistically significant difference in the overall rate of TRS. Similarly, meta-regression by duration of follow-up did not significantly alter the rate of TRS. Definitions of TRS varied between studies, but when we undertook sensitivity analysis by definition of TRS, the overall rate remained stable. Although many studies provided information on dose and duration of medication trials, there was a lack of data on other factors, which may influence treatment response, including medication trial adherence and comorbid substance misuse. Insufficient data was available to undertake a subanalysis of specific antipsychotics used, nor on route of administration. There was limited data on provision of psychosocial interventions. Only two studies commented on whether patients were voluntary or involuntary, making subanalysis by voluntary status impractical. Our analysis had a high level of heterogeneity, and as such should be treated with caution. Exploration by subgroup was unable to identify key factors driving heterogeneity.

In conclusion, a substantial proportion of people with schizophrenia have treatment-resistant illness, with almost a quarter of participants experiencing FES also having TRS. The true rate of TRS may be as high as a third if people who develop breakthrough psychotic symptoms following initial response are considered. As with schizophrenia more generally, men are more likely to develop TRS. Given the low rates of clozapine use among people with TRS, there needs to be an increased effort to improve access to clozapine and psychosocial supports among patients with TRS.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2021.61.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, D.S., upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

D.S. collaboratively conceived of the study with S.O. and S.S., with input from all authors. D.S., S.O., S.S., O.Y., B.B. and S.K. developed the search terms. S.O., S.S., O.Y. and B.B. conducted the searches and data extraction, with support from D.S. and S.K. S.E.S. and J.H.M. provided unpublished data. D.S. undertook the data analysis collaboratively with S.O. and S.S., with support from O.Y., B.B. and S.K. D.S., S.O., S.S. and N.W. collaboratively wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Funding

D.S. is supported in part by a National Health and Medical Research Council Emerging Leadership Fellowship (number GNT1194635). O.Y. was supported by a University of Queensland Summer Scholar Fellowship. S.E.S. was supported by Medical Research Council grant MR/L011794/1. J.H.M. is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. All other authors have no funding to declare. None of the funding sources had any role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Declaration of interest

N.W. has received speaker's honoraria from Otsuka and Lundbeck. S.K. has a received speaker's honorarium from Janssen, and an advisor's honorarium from Lundbeck. S.K. is a member of the British Journal of Psychiatry International Editorial Board. He did not take part in the journal review or decision-making process regarding this submission. J.H.M. has received research funding from Lundbeck. All other authors have no interests to declare.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.